Abstract

Combining different classes of antihypertensives is more effective for reducing blood pressure (BP) than increasing the dose of monotherapies. The aims of this phase I study were to investigate pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions between nebivolol, a vasodilatory β1-selective blocker, and valsartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker, and to assess safety and tolerability of the combination. This was a single-center, randomized, open-label, multiple-dose, 3-way crossover trial in 30 healthy adults aged 18–45 years. Participants were randomized into 1 of 6 treatment sequences (1:1:1:1:1:1) consisting of three 7-day treatment periods followed by a 7-day washout. Once-daily oral treatments comprised nebivolol (20 mg), valsartan (320 mg), and nebivolol–valsartan combination (20/320 mg). Outcomes included AUC0-τ,ss, Cmax,ss, Tmax,ss, changes in BP, pulse rate, plasma angiotensin II, plasma renin activity, 24-hour urinary aldosterone, and adverse events. Steady-state pharmacokinetic interactions were observed but deemed not clinically significant. Systolic and diastolic BP reduction was significantly greater with nebivolol–valsartan combination than with either monotherapy. The mean pulse rate associated with nebivolol and nebivolol–valsartan treatments was consistently lower than that associated with valsartan monotherapy. A sharp increase in mean day 7 plasma renin activity and plasma angiotensin II that occurred in valsartan-treated participants was significantly attenuated with concomitant nebivolol administration. Mean 24-hour urine aldosterone at day 7 was substantially decreased after combined treatment, as compared with either monotherapy. All treatments were safe and well tolerated. In conclusion, nebivolol and valsartan coadministration led to greater reductions in BP compared with either monotherapy; nebivolol and valsartan lower BP through complementary mechanisms.

Keywords: nebivolol, valsartan, combination, pharmacokinetics, hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension occurs in one-third of adults in the United States, 77% of whom are treated with antihypertensive medications1,2; however, 40% of patients receiving pharmacologic therapy are unable to attain blood pressure (BP) control [systolic blood pressure (SBP)/diastolic blood pressure (DBP) <140/90 mm Hg].1,3 Over a 10-year period, there was a significant increase in the use of multiple antihypertensive agents to help achieve BP control, with 48% of patients currently treated with 2 or more drugs.1 Combining 2 antihypertensive drugs is associated with better efficacy1,4 and tolerability4,5 than doubling the dose of a monotherapy. Additionally, patients taking a single-pill combination show better BP control rates versus those on free-pill equivalents or monotherapies.6,7 Although combinations consisting of a β-blocker and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) have been deemed not very effective,8 a recently completed randomized, controlled, phase III trial demonstrated that a fixed-dose combination of the β-blocker nebivolol and the ARB valsartan was more efficacious in reducing BP than either drug alone and was well tolerated.9

Nebivolol is a third-generation vasodilatory β-blocker with a high β1 adrenoreceptor selectivity,10,11 and these properties may explain its better tolerability compared with other β-blockers.10,12,13 In addition to its BP reducing efficacy, nebivolol also produces a negative chronotropic effect and nitric oxide–dependent vasodilation.10 Single-dose pharmacokinetic (PK) studies have shown that the mean maximum plasma drug concentration (Cmax) of nebivolol is achieved within 2–4 hours with an absolute bioavailability of 12%–96% and a mean half-life of 17–50 hours, depending on CYP2D6 polymorphism.14,15 Despite the longer half-life and systemic exposure of nebivolol in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers, no dose adjustment is needed as the clinical effect and safety profile were similar to those in extensive metabolizers;15 it is postulated that this outcome may be explained by the presence of several active metabolites. Valsartan, a selective antagonist of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor, has a good safety and tolerability profile,16,17 but, like other ARBs, it has been shown to increase levels of angiotensin II, plasma renin activity (PRA), and aldosterone. Unlike nebivolol, it has no measurable effect on heart rate.18 Studies have shown that the Cmax of a single dose of valsartan is reached in 2–4 hours with a mean half-life of 6 hours and a mean absolute bioavailability of 25%.18

Combining drugs with differing mechanisms of action, such as a β-blocker and an ARB, may allow for greater BP reductions while attenuating negative effects such as increased angiotensin II and PRA induced by ARB treatment. In a previous study, atenolol, another β1-selective blocker, mitigated valsartan-induced increases in angiotensin II and PRA.19 The primary aim of this study was to examine the PK and pharmacodynamic (PD) interactions of short-term, concomitant, multiple-dose treatment of nebivolol and valsartan at steady state in healthy adults, with the additional aim of assessing the safety and tolerability of the combined treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample size

This was a pilot study and as such the chosen sample size of 30 adults was not based on statistical calculation but on typical sample sizes used in drug interaction studies.

Study population

Participants were required to be healthy men or women, aged 18–45 years, nonsmoker for at least 2 years, with a body mass index of 18–30 kg/m2, and a resting pulse rate (PR) of 50–100 beats per minute (bpm). Men and women of childbearing age were asked to use an effective method of contraception for the duration of the study.

Key exclusion criteria included a contraindication to β-blockers or ARBs, a resting SBP of ≤90 or ≥140 mm Hg or DBP of <50 or ≥90 mm Hg, abnormal electrocardiogram results or QT interval prolongation (QTcF ≥430 ms for men or ≥450 ms for women), consumption of grapefruit or caffeine-containing products within 48 hours or alcohol within 72 hours before study drug administration, conditions that could affect the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of nebivolol or valsartan, concomitant medication use within 14 days or hormonal medications within 30 days before study drug administration, previous use of nebivolol or valsartan, identification as poor metabolizer (by means of CYP2D6 genotyping), serum sodium levels of <135–145 mEq/L, serum potassium levels of ≥5.3 mEq/L, or current pregnancy or breastfeeding.

This study complied with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidance on General Considerations for Clinical Trials (ICH-E8; 62 FR 66113, December 17, 1997), Nonclinical Safety Studies for the Conduct of Human Clinical Trials for Pharmaceuticals (62 FR 62922, November 25, 1997), and Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance (ICH-E6; 62 FR 25692, May 9, 1997). Study protocols and informed consent forms were approved by the independent institutional review board. All participants provided written informed consent before study screening.

Study design and treatments

This study was designed as a single-center, randomized, open-label, multiple-dose, 3-way crossover trial in healthy adults. Potential participants were screened within 21 days before study entry, and eligible individuals were randomized into 1 of 6 drug treatment sequences (1:1:1:1:1:1). Each sequence consisted of three 7-day drug treatment periods followed by a 7-day washout period, for a total of 36 days not including the screening visit. Once-daily treatments consisted of nebivolol 20 mg tablets (treatment A), valsartan 320 mg tablets (treatment B), or nebivolol 20 mg tablets plus valsartan 320 mg tablets (treatment C). All treatments were given orally, with 240 mL of water, under fasted conditions (no food before 10 hours of dose and after 4 hours of dose). For each period, participants reported to the clinical site at least 1 day before the first day of the period (days 1, 14, and 27) and remained in-house for the duration of that period.

PK/PD sampling and analytical methods

Blood samples were collected on days 1, 14, and 27 (0 hours before dose) and on days 7, 20, and 33 (0 hours before dose and at 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, 24, 36, and 48 hours after dose) in tubes containing K2EDTA and centrifuged at ≥2500g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The plasma was then transferred into polypropylene tubes and frozen at −70°C until assayed. Concentrations of d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol (nonconjugated, d- and l-nebivolol), total nebivolol glucuronides (nonconjugated nebivolol and conjugated nebivolol glucuronides measured after enzymatic hydrolysis), and valsartan were determined by means of independent, sensitive, validated methods of high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) using internal standards labeled with stable isotopes. After off-line automated plasma sample cleanup through mixed cation exchange on the Quadra Liquid Handler (Tomtec, Hamden, CT), nonconjugated d-nebivolol and l-nebivolol were quantified with an enantiospecific assay on a Chiralpak IA column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5-μm particle size; Chiral Technologies Inc, West Chester, PA). Detection of the analytes was performed by means of electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in the positive mode on an API 4000 (AB Sciex, Framingham, MA) with a detection range of 0.05–20.0 ng/mL. Total plasma nebivolol was quantified using a separate method after the addition of β-glucuronidase in a 200 mM ammonium acetate solution and incubation for 1 hour at 37°C. Samples were enzymatically hydrolyzed, treated with ammonium hydroxide, and cleaned up by a Quadra Liquid Handler using liquid–liquid extraction with methyl-tert-butyl ether. Detection of total nebivolol (detection range 0.5 to 200 ng/mL) was carried out using ESI-MS in the positive mode on an API 4000. The quantification of d-nebivolol and l-nebivolol and total nebivolol was carried out at Forest Research Institute (Farmingdale, NY). The quantification of valsartan was carried out at Tandem Labs (Salt Lake City, UT) using protein precipitation and detection with ESI-MS in the positive ion mode. For each participant, concentration of d,l-nebivolol was calculated by adding the concentrations of both nonconjugated enantiomers; levels of nebivolol glucuronides were determined by subtracting the corresponding concentrations of nonconjugated d-nebivolol and l-nebivolol from the total nebivolol concentration (combined concentrations of conjugated and nonconjugated molecules).

Blood samples for determining the PRA and the concentration of angiotensin II were collected on days 1, 14, and 27 (0 hours before dose) and on days 7, 20, and 33 (0 hours before dose and at 2, 4, 12, and 24 hours after dose) and processed as explained above. PRA analysis was carried out at Quest Diagnostics using a validated HPLC-MS/MS assay. Plasma samples were incubated with a generation solution containing aminoethyl benzenesulfonyl fluoride, a protease inhibitor that blocks the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. This solution also contained a double-isotope labeled angiotensin I degradation standard to correct for the degradation by other proteases. Once angiotensin I was generated, the samples were quenched and subjected to solid-phase extraction, and isolation and detection were performed with ESI-MS in the positive ion mode. The detection range of the PRA assay was 0.127–129.651 ng·mL−1. Plasma angiotensin II levels were determined using a commercially available enzyme immunoassay that was validated at Keystone Bioanalytical, Inc. This entailed partial purification of angiotensin II using phenyl solid-phase extraction columns and quantification through solid-phase immobilized epitope immunoassay. Optical density was read at 414 nm and the detection range was 1.955–62.5 pg/mL. Aldosterone levels were determined from urine samples collected during 24-hour periods, beginning at 8:00 am (before dose) on days 1, 7, 13, 20, and 26 and were measured using validated HPLC-MS/MS at Keystone Bioanalytical. The assay entailed liquid–liquid extraction for sample cleanup and detection with ESI-MS in the negative ion mode with a detection range of 0.1–50.0 ng/mL.

Safety and tolerability assessments

Safety and tolerability were assessed using descriptive statistics based on the Safety population. Mean changes from baseline were examined for each safety measure except adverse events (AEs) using the last assessment taken before the first drug dose in that period as baseline.

PK/PD parameters and statistical analysis

Outcome measures included the PK and PD parameters and the safety and tolerability of the 3 treatments. The PK assessments in plasma at steady state comprised determination of the area under the curve (AUC) from time 0 to the dosing interval τ; (AUC0-τ,ss), maximum drug concentration (Cmax,ss), minimum drug concentration (Cmin,ss), average drug concentrations (Cav,ss), time of maximum drug concentration after dose (Tmax,ss), drug half-life (T1/2), and fluctuation for the following analytes: d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol, d,l-nebivolol [racemic mixture of 2 enantiomers: d-nebivolol (SR3-nebivolol) and l-nebivolol (RS3-nebivolol)20], nebivolol glucuronides, and valsartan. Additionally, apparent total clearance post-dose (CL/F) and apparent volume of distribution post-dose (Vz/F) were determined for d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol, d,l-nebivolol, and valsartan.

All PK analyses were based on the PK population, defined as all participants who completed the study. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed, and natural-logarithm-transformed Cmax,ss and AUC0-τ,ss values were analyzed using analysis of variance (MIXED procedure), with treatment sequence, treatment, treatment period, and participant included in the model. The effect of treatment sequence was tested using participants nested within treatment sequence as the error term (α = 0.05, 2-sided). In addition, a 2-sided 90% confidence interval (CI) for the ratio of the geometric means of Cmax,ss and AUC0-τ,ss between nebivolol plus valsartan (treatment C) and nebivolol alone (treatment A) was calculated, and Tmax,ss comparisons were performed using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The criterion for no PK interaction effect was met if the 90% CIs around the geometric mean ratios for the Cmax,ss and AUC0-τ, were within the range of 80%–125%. Finally, the attainment of steady state was determined through visual inspection of the PK concentration profiles. Any plasma concentrations falling below the lower limit of quantification method were entered as zero.

The PD assessments comprised measurements of plasma concentration of angiotensin II, PRA, 24-hour urinary concentrations of aldosterone, and resting PR and BP. PD analyses were based on the Safety population, defined as all randomized participants who received at least 1 dose of study drug. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed for all PD parameters. All measures except for 24-hour urinary aldosterone levels were analyzed using a general longitudinal linear model with time (as a class variable with unstructured variance–covariance matrix), treatment sequence, drug treatment, treatment period, and participant within treatment sequence as factors and baseline value as a covariate. A general linear model that included the same factors mentioned above, with the exception of baseline as a covariate, was used to analyze the 24-hour urinary aldosterone data. For angiotensin II and PRA, a paired t test was applied to compare the sum of the baseline-corrected AUCs after the single drug treatments with the AUCs after concomitant treatment. The values for angiotensin II and PRA were log transformed for both analyses. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1.3.

The outcome measures of drug safety and tolerability comprised vital signs, clinical laboratory parameters, and electrocardiograms (screening, days 14 and 27 before dose, and study completion). In addition, AEs were monitored throughout the study, with those occurring during treatment periods for the first time or with an increased severity being considered treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs).

RESULTS

Study flow and baseline characteristics

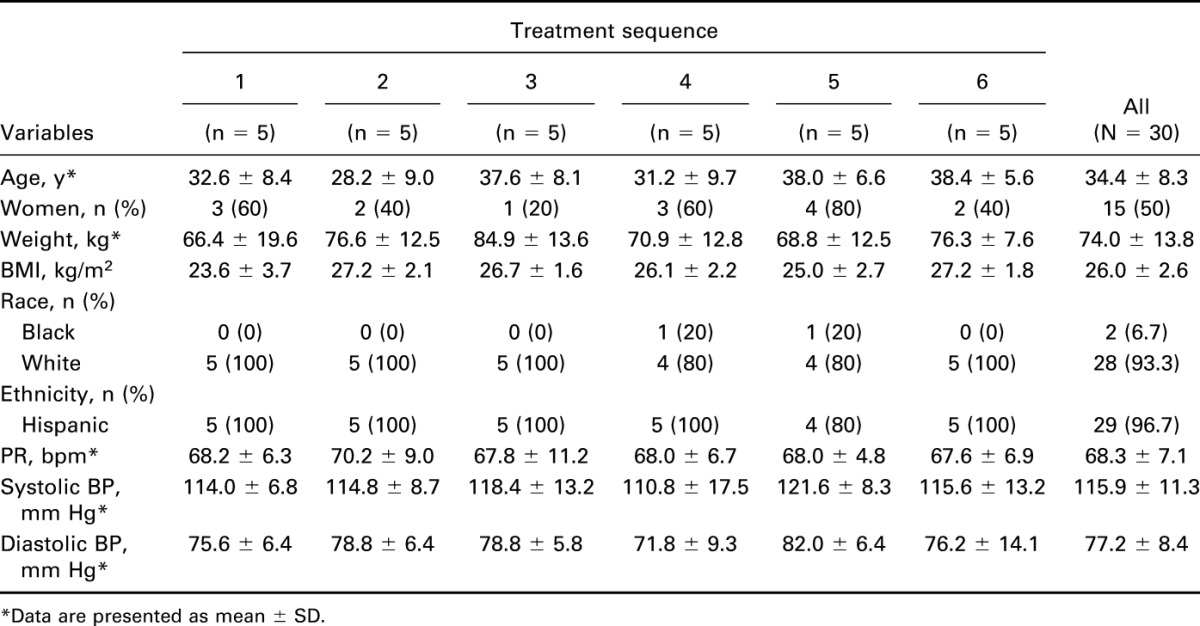

Of 30 healthy participants (15 men and 15 women) randomly assigned to 1 of the 6 treatment sequences, 4 (13.3%) discontinued the study because of the following reasons: AE (n = 1, treatment sequence 4), protocol violation (n = 1, sequence 5), consent withdrawal (n = 1, sequence 1), or loss to follow-up (n = 1, sequence 2). Baseline characteristics and vital signs of the Safety population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and vital signs of the safety population.

PK parameters

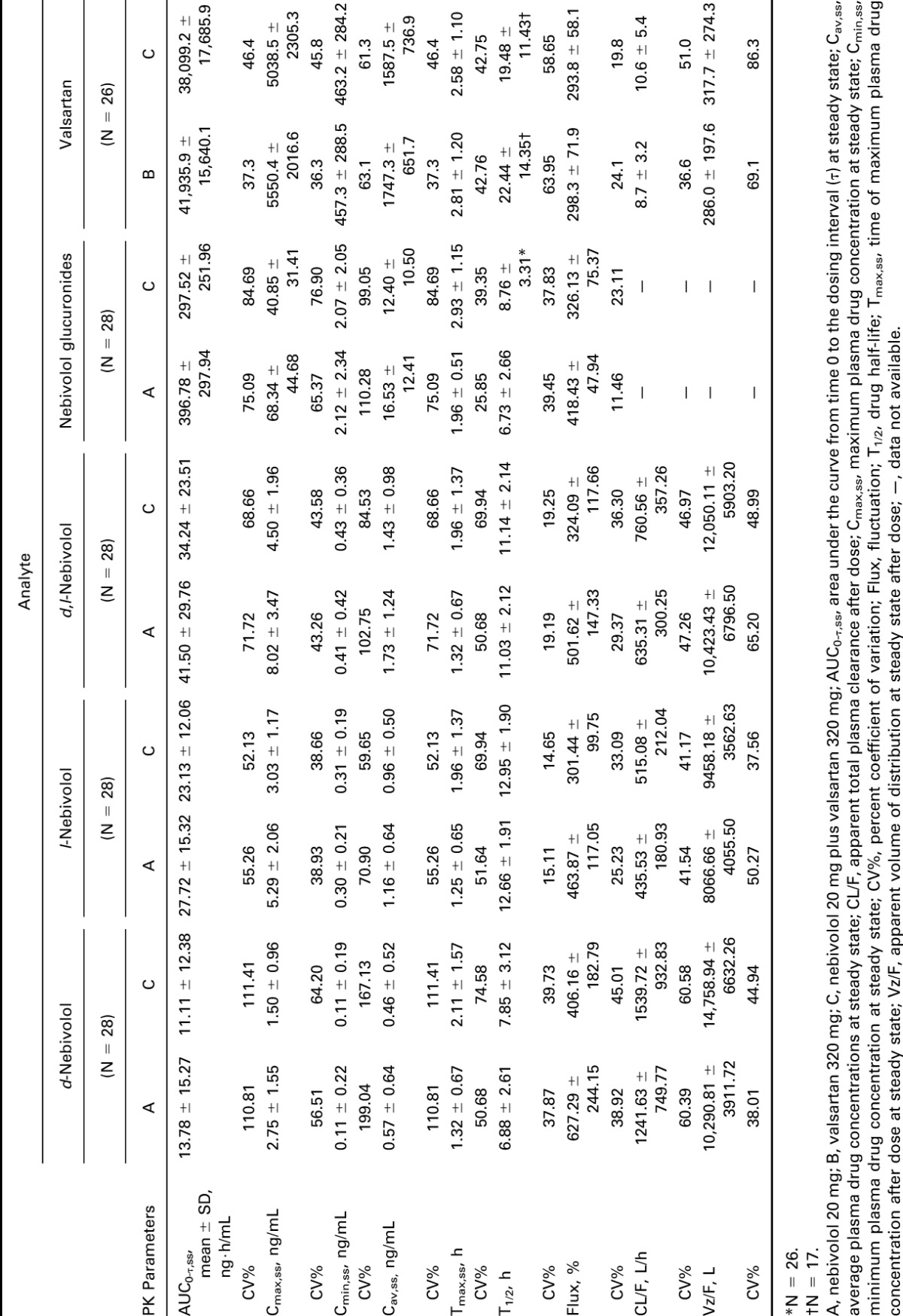

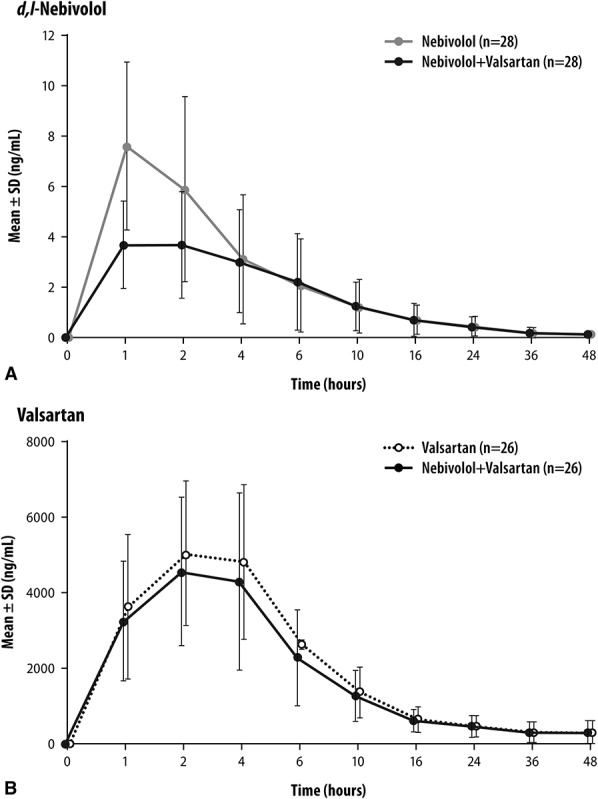

Mean values and CV% for PK parameters for each analyte by treatment are presented in Table 2. Plasma concentrations over time for d,l-nebivolol and valsartan are shown in Figures 1A, B. The AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss (geometric means) of d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol, d,l-nebivolol, and nebivolol glucuronides were all significantly lower after coadministration of nebivolol and valsartan (16%–27% and 43%–45%, respectively), compared with administration of nebivolol alone. In addition, the mean Tmax,ss of all 4 analytes was 49%–60% longer after nebivolol–valsartan coadministration, compared with nebivolol-only treatment. An approximately 13% lower geometric mean AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss of valsartan was observed with nebivolol–valsartan than with valsartan alone mean Tmax,ss values were similar between the 2 treatments (Table 3).

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for each analyte by treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Plasma concentration–time profiles of d,l-nebivolol (A) and valsartan (B) by treatment. Data are represented on a linear scale.

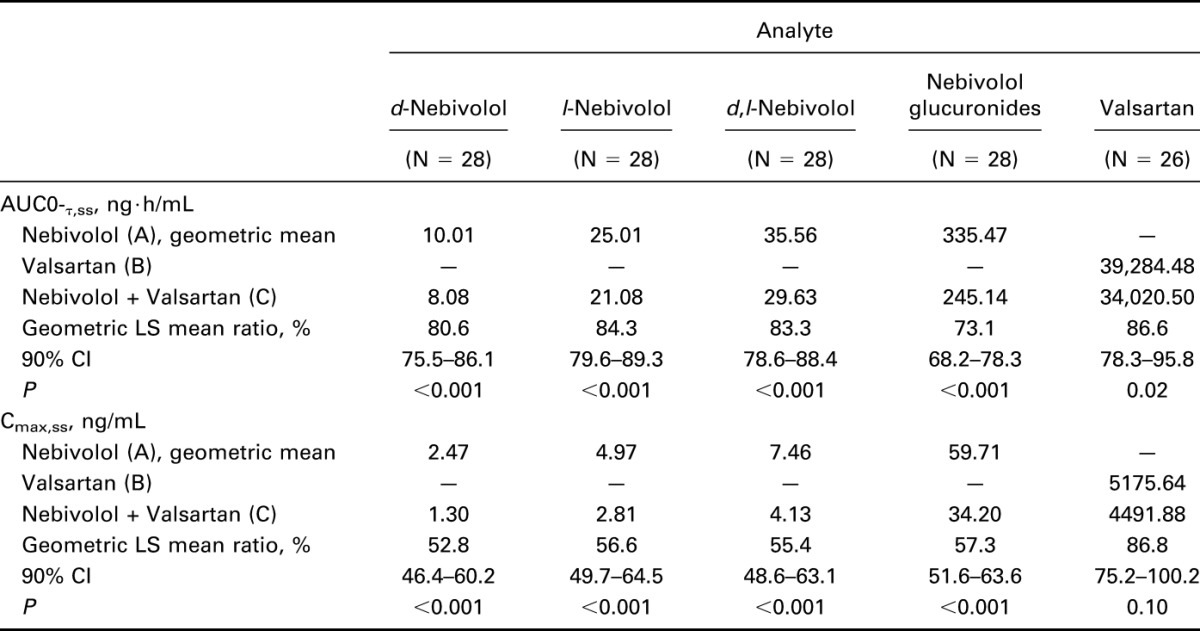

Table 3.

AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss by treatment for each analyte.

Interaction effects were observed at steady state between nebivolol and valsartan for d-nebivolol, l-nebivolol, d,l-nebivolol, nebivolol glucuronides, and valsartan with 1 or more of the 90% CIs for AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss falling outside the 80%–125% range (Table 3).

PD parameters

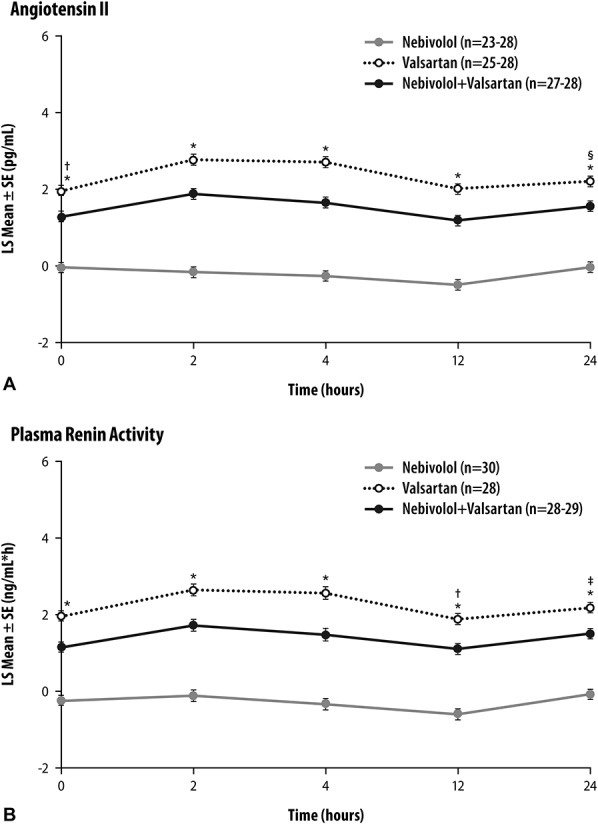

Plasma concentration of angiotensin II did not change with nebivolol administration, but its increase after nebivolol–valsartan treatment was smaller compared with the one observed after the administration of valsartan alone (Figure 2A). At each time point, differences in angiotensin II concentration between treatments were statistically significant (P ≤ 0.004). The PRA data showed a similar pattern (Figure 2B), with between-group differences at each time point also being statistically significant (P ≤ 0.003).

FIGURE 2.

Plasma angiotensin II concentration (A) and plasma renin activity (B) at the end of treatment periods (days 7, 20, and 33). *P < 0.0001, nebivolol versus combination and valsartan versus combination; †P = 0.0002, ‡P = 0.0003, §P = 0.0004, valsartan versus combination. SE, standard error of the mean.

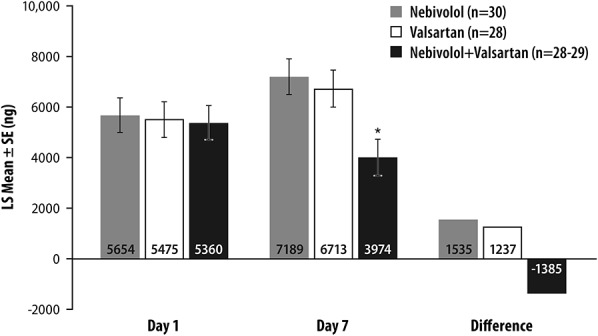

On day 7 of treatment, urine aldosterone levels in individuals receiving nebivolol or valsartan alone increased over baseline by 27% or 23%, respectively, whereas in those receiving nebivolol–valsartan combination, levels decreased by 23% (Figure 3). On the last day of each treatment period (days 8, 21, and 34), differences in aldosterone levels between concomitant nebivolol–valsartan treatment and treatment with each drug alone were both statistically significant (nebivolol–valsartan vs. nebivolol, P = 0.003; nebivolol–valsartan vs. valsartan, P = 0.002).

FIGURE 3.

Twenty-four-hour urinary aldosterone excreted unchanged at the end of treatment periods (days 7/8, 20/21, and 33/34). *P = 0.0019, valsartan versus combination and P = 0.0003, nebivolol versus combination. SE, standard error of the mean.

Mean SBP decreased after each treatment, reaching lowest values 6 hours after dose on day 1. For all treatments, SBP and DBP fell below baseline values for up to 7 days. The nebivolol–valsartan combination was associated with lower least square (LS) mean values of SBP (days 7, 20, and 33; range: −18.7 to −23.6 mm Hg) and DBP (−13.7 to −17.8 mm Hg) compared with nebivolol (SBP: −13.7 to −18.4 mm Hg; DBP: −9.9 to −13.9 mm Hg) or valsartan treatment alone (SBP: −12.3 to −17.3 mm Hg; DBP: −8.7 to −11.7 mm Hg), with between-treatment differences reaching statistical significance at various time points throughout the study between concomitant and nebivolol or valsartan only treatments (both SBP and DBP, P ≤ 0.05; data not shown).

Valsartan was associated with a transient PR increase after 6 hours of dose (LS means range: 2.7–4.6 bpm); with nebivolol or nebivolol–valsartan, the greatest decreases were observed within 4 hours after dose (LS means range, nebivolol: −13.5 to −19.0 bpm; nebivolol–valsartan: −14.7 to −19.3 bpm), and PR generally remained below baseline for the rest of the study. At all time points, there were differences between valsartan and nebivolol–valsartan treatment and between valsartan and nebivolol alone (P ≤ 0.001; data not shown).

Safety and tolerability

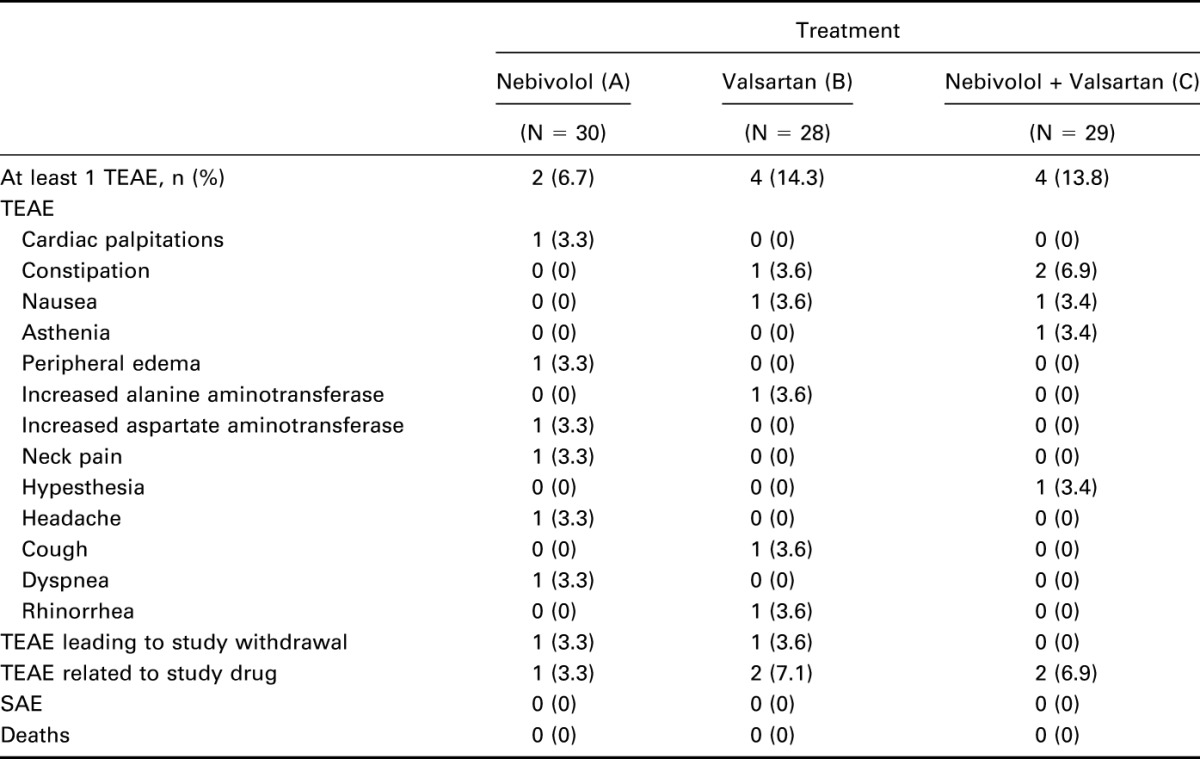

Ten participants reported TEAEs during the study: 2 (6.7%) while receiving nebivolol, 4 (14.3%) on valsartan, and 4 (13.8%) on nebivolol plus valsartan. All 18 reported TEAEs were of mild or moderate severity. One participant was withdrawn by study investigators at the end of period II because of potentially clinically significant laboratory findings. No severe AEs or deaths occurred during the study (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse events.

DISCUSSION

Results show a steady-state PK interaction between nebivolol and valsartan in healthy adults. Concomitant treatment with nebivolol and valsartan was associated with a 13% decrease in the AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss of plasma valsartan levels, and with 16%–27% and 43%–47% reductions in the AUC0-τ,ss and Cmax,ss respectively, of nebivolol and nebivolol glucuronides, compared with single drug treatments. Because of the shallow dose–response relationships of both drugs, supported by further population PD analysis conducted21,22; these PK interactions were deemed not clinically significant.

PD effects of nebivolol or valsartan alone on plasma angiotensin II, PRA, urinary aldosterone, BP, and PR were expected and are similar to those observed in previous studies.23–27 However, concomitant nebivolol–valsartan administration attenuated increases in PRA and angiotensin II levels associated with valsartan monotherapy (a known effect of ARB treatment28–30), and it reversed elevated aldosterone levels observed with both monotherapies. “Aldosterone escape” (or “aldosterone breakthrough”) is a well-known phenomenon that affects a subset of ARB or ACEI-treated patients.31 The effects of β-blockers on aldosterone levels are less well understood, but a 1992 study conducted in China showed a decrease in plasma aldosterone levels (as opposed to urinary aldosterone in our study) after 4 weeks of nebivolol treatment.32

The BP effect of coadministered nebivolol–valsartan exceeded the effects of each drug alone, which is consistent with the results of a large 8-week randomized trial (N = 4161) that compared the efficacy of nebivolol–valsartan single-pill combination with those of monotherapies.9 Our safety and tolerability data are also consistent with previous studies on nebivolol or valsartan alone12,13,17,22,33 or in combination,9 demonstrating a generally mild side effect profile without serious treatment-related AEs.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this study on the combination treatment of nebivolol and valsartan show clinically nonmeaningful PK effects, partially additive PD effects, and good tolerability and safety in healthy volunteers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Editorial support (data checking, development of figures and tables, incorporation of authors' comments, wording suggestions) was provided by Lynn M. Anderson, Mark Blade, Vojislav Pejović, and Leah Richmond of Prescott Medical Communications Group, Chicago, IL, a contractor of the study sponsor. The authors would like to acknowledge the bioanalytical scientists at Forest Research Institute (Farmingdale, NY), Keystone Bioanalytical Inc., and Tandem Labs for their support on the bioanalysis of the study samples.

Footnotes

The study was supported by the Forest Research Institute.

All authors were employees of the study sponsor at the time the study was conducted. Actavis is the US marketer of nebivolol.

The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, et al. Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among united states adults with hypertension: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2001 to 2010. Circulation. 2012;126:2105–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, et al. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards TR, Tobe SW. Combining other antihypertensive drugs with beta-blockers in hypertension: a focus on safety and tolerability. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:s42–s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan BM, Bandyopadhyay D, Shaftman SR, et al. Initial monotherapy and combination therapy and hypertension control the first year. Hypertension. 2012;59:1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, Valuck R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antihypertensive therapeutic classes and treatment strategies in the initiation of therapy in primary care patients: a distributed ambulatory research in therapeutics network (dartnet) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gradman AH, Basile JN, Carter BL, et al. Combination therapy in hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2011;13:146–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles TD, Weber MA, Basile J, et al. Efficacy and safety of nebivolol and valsartan as fixed-dose combination in hypertension: a randomised, multicentre study. Lancet. 2014;383:1889–1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munzel T, Gori T. Nebivolol: the somewhat-different beta-adrenergic receptor blocker. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1491–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao Y, Vanhoutte PM. Nebivolol: an endothelium-friendly selective beta1-adrenoceptor blocker. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011;59:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Bortel LM, Fici F, Mascagni F. Efficacy and tolerability of nebivolol compared with other antihypertensive drugs: a meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2008;8:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howlett JG. Nebivolol: vasodilator properties and evidence for relevance in treatment of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:s29–s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Peer A, Snoeck E, Woestenborghs R, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of nebivolol. Drug Invest. 1991;3:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nebivolol Hydrochloride: Investigator's Brochure. Jersey City, NJ: Forest Research Institute, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Sagara Y, et al. Effects of valsartan or amlodipine on endothelial function and oxidative stress after one year-follow-up in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30:267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogari R, Zoppi A. A drug safety evaluation of valsartan. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diovan [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czendlik CH, Sioufi A, Preiswerk G, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interaction of single doses of valsartan and atenolol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;526:451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssens WJ, Xhonneux R, Janssen PAJ. Animal pharmacology of nebivolol. Drug Invest. 1991;3:13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makani H, Bangalore S, Supariwala A, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy of angiotensin receptor blockers as monotherapy as evaluated by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1732–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss RJ, Saunders E, Greathouse M. Efficacy and tolerability of nebivolol in stage I-II hypertension: a pooled analysis of data from three randomized, placebo-controlled monotherapy trials. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1150–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Himmelmann A, Hedner T, Snoek E, et al. Haemodynamic effects and pharmacokinetics of oral d- and l- nebivolol in hypertensive patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;51:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS. Clinical experience with angiotensin receptor blockers with particular reference to valsartan. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2004;6:445–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Champlain J, Karas M, Assouline L, et al. Effects of valsartan or amlodipine alone or in combination on plasma catecholamine levels at rest and during standing in hypertensive patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright JT, Jr, Bakris GL, Bell DS, et al. Lowering blood pressure with beta-blockers in combination with other renin-angiotensin system blockers in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes: results from the gemini trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:842–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Z, Lin S, Shi H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of telmisartan versus valsartan in the management of essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:414–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ke YS, Tao YY, Yang H, et al. Effects of valsartan with or without benazepril on blood pressure, angiotensin ii, and endoxin in patients with essential hypertension. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Struck J, Muck P, Trubger D, et al. Effects of selective angiotensin II receptor blockade on sympathetic nerve activity in primary hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1143–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams B, Baschiera F, Lacy PS, et al. Blood pressure and plasma renin activity responses to different strategies to inhibit the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system during exercise. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2013;14:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bomback AS, Klemmer PJ. The incidence and implications of aldosterone breakthrough. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:486–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan TY, Woo KS, Nicholls MG. The application of nebivolol in essential hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Cardiol. 1992;35:387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biswas PN, Wilton LV, Shakir SW. The safety of valsartan: results of a postmarketing surveillance study on 12881 patients in England. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16:795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]