Abstract

Biomass has delicate hierarchical structures, which inspired us to develop a cost-effective route to prepare electrode materials with rational nanostructures for use in high-performance storage devices. Here, we demonstrate a novel top-down approach for fabricating bio-carbon materials with stable structures and excellent diffusion pathways; this approach is based on carbonization with controlled chemical activation. The developed free-standing bio-carbon electrode exhibits a high specific capacitance of 204 F g−1 at 1 A g−1; good rate capability, as indicated by the residual initial capacitance of 85.5% at 10 A g−1; and a long cycle life. These performance characteristics are attributed to the outstanding hierarchical structures of the electrode material. Appropriate carbonization conditions enable the bio-carbon materials to inherit the inherent hierarchical texture of the original biomass, thereby facilitating effective channels for fast ion transfer. The macropores and mesopores that result from chemical activation significantly increase the specific surface area and also play the role of temporary ion-buffering reservoirs, further shortening the ionic diffusion distance.

Supercapacitors are a promising alternative energy technology; they can provide higher power densities, faster charge/discharge rates and longer lifespans because their energy storage mechanism involves reversible adsorption of electrolyte ions onto activated materials for electrostatic charge storage1. Charge separation occurs because of polarization at the electrode–electrolyte interface, producing what Helmholtz described in 1853 as the double-layer capacitance C: C =ε rε0A/d, where εr is the electrolyte dielectric constant, ε0 is the dielectric constant of vacuum, d is the effective thickness of the double layer (i.e., the charge separation distance) and A is the electrode surface area2,3. A high specific surface area (SSA) facilitates high capacitance, which has spurred the development of nanoscale electrode materials4,5,6,7,8. However, the experimentally measured capacitance of nanoscale carbon electrodes has been far below its theoretical value because the accessible SSA is substantially smaller than the SSA of the pristine electrode material9,10. The insufficiently open porous structures influence the diffusion pathways of ions in the matrix, and the poor wettability adversely affects the adsorption of ions onto the surface of the electrodes, thereby limiting the utilizable SSA11,12. Li et al.13 fabricated graphene films using a bio-inspired self-stacked approach and demonstrated that a solvated graphene film exhibited the highest capacitance and rate capability among the investigated graphene films. The solvation process used water molecules as an effective "spacer" to prevent the restacking of graphene nanosheets to retain the high accessible SSA and effective ion diffusion. Later work further confirmed that graphene films employ a nonvolatile liquid electrolyte as a "spacer" to improve the accessible SSA, leading to a significantly enhanced volumetric energy and power capability14. Furthermore, on the basis of the mechanism of electrostatic charge storage, double-layer supercapacitors should exhibit a high power density. In practice, however, many electrodes exhibit relatively low rate capabilities15. For example, a modified graphene film electrode was observed to retain half of the capacitance of the pristine electrode material when the current density was increased from 1 to 8 A g−1 16. This behaviour arises from the limitation of charge transport in the electrode or of ionic transport in the electrolyte17. The complex diffusion pathways exacerbate the limitation of ion transport at a high scan rates, delaying the formation of double-layer capacitance18,19,20,21,22. Therefore, obtaining a good diffusion pathway is the critical issue that must be solved to enable the fabrication of supercapacitors with excellent electrochemical performance.

Unfortunately, the synthesis of functional nanostructures often involves expensive starting materials and elaborate processing, both of which present a challenge for successful implementation in low-cost applications. By contrast, biomass has the delicate hierarchical structures necessary for the diffusion of electrolytes in living organisms, inspiring researchers to develop cost-effective routes for using biomass to prepare nanostructured electrode materials. For instance, ordered channel arrays of hollow carbon nanofibres originating from crab shells were used to encapsulate silicon to form anodes for Li-ion batteries. This composite electrode exhibits high energy and power densities and good cycling stability because of the short diffusion pathway of ions and stable skeleton structures23. Chitin, chitosan, glucosamine, polysaccharide and protein from biomass have naturally porous structures that can be carbonized to obtain activated carbon with unique porous structures24,25,26,27,28,29. Electrodes fabricated using these bio-carbon materials exhibit good rate capability and stable cycleability30,31. However, high-temperature carbonization leads to a reduction in the biomass and the partial destruction of pristine microstructure, decreasing the specific capacitance28. Chemical activation is a typical method for modifying carbon materials to improve their porosity17. For instance, activating agents such as NaOH, KOH and Na2CO3 have been used to etch carbon materials, resulting in the fabrication of a series of micropores, mesopores and macropores that optimize the structure and improve its application performance32,33.

In this work, we chose sisal leaves as a precursor to bio-carbon because of their strong mechanical properties, which facilitate the preparation of free-standing carbon monoliths. The resultant bio-carbon materials with a hierarchical texture inherited from sisal leaves were prepared under various carbonization conditions, which structures afford effective diffusion pathways for ions. Meanwhile, controlled chemical activation was used to manipulate the macropores and mesopores on the skeletons of the bio-carbon. Macroporous and mesoporous cores can be used as ion-buffering reservoirs to significantly improve the SSA and further shorten the diffusion distances to the interior surfaces. The free-standing electrode exhibited a high specific capacitance of 204.1 F g−1 at 1 A g−1; a good rate capability, including a residual initial capacitance of 85.5% at 10 A g−1; and a long cycle life. These results were likely due to the larger accessible SSA and the shorter diffusion pathways that promote both the adsorption of a greater number of ions onto the electrode/electrolyte interface and faster ionic transport.

Results and Discussion

Morphology and structure

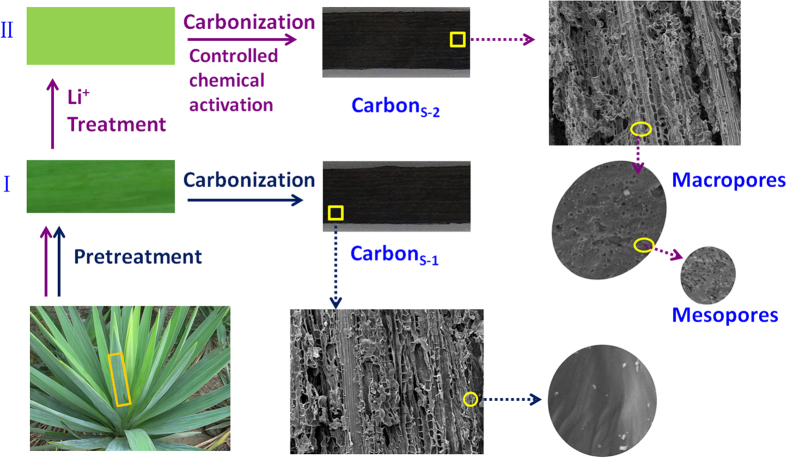

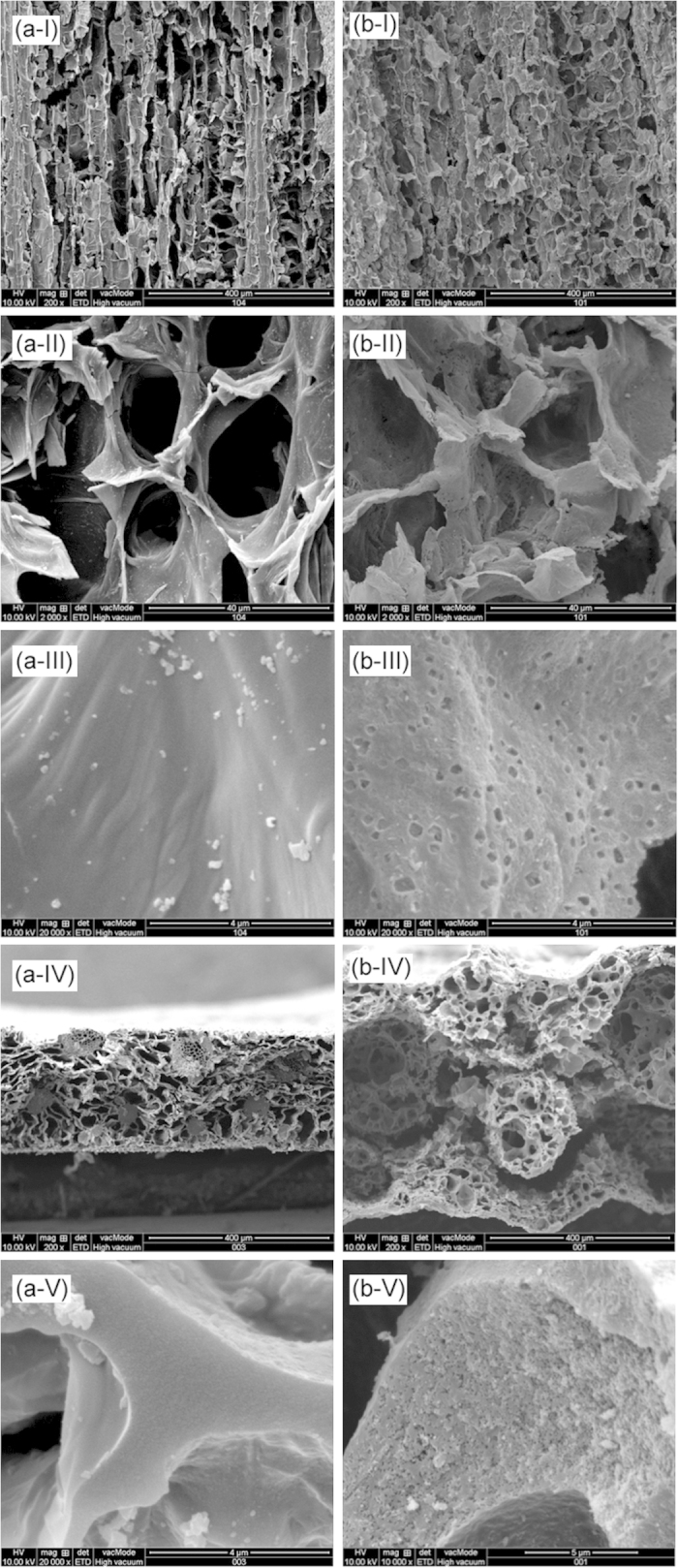

Sisal hemp is a species of plant of the tropics and subtropics and consists of a rosette of sword-shaped leaves. Each sisal leaf contains an average of approximately 1000 fibres, which account for only approximately 4% of the plant by weight but help the leaves maintain their strong texture34. Because of its good mechanical properties and porous structure, sisal leaf is a promising candidate for the fabrication of free-standing carbon monoliths. Figure 1 displays a schematic of the processes for preparing bio-carbon from sisal leaves. One method is to directly prepare the bio-carbon material (CarbonS-1) by carbonization at high temperatures. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of CarbonS-1 show connected porous frameworks with various pore sizes (Fig. 2a(I,II,III)) implying that CarbonS-1 inherited the pristine hierarchical structure of sisal leaves. SSA measurements confirmed that the CarbonS-1 BET surface area was as high as 171 m2 g−1 (Fig. 3a). Compared to the low BET values of the reported bio-carbons obtained without chemical activation28,35, our CarbonS-1 exhibits a relatively high surface area. This result is attributed to the novel freeze-dry pretreatment, which perfectly retains the organization of the sisal leaves’ structure after the removal of water from the biological body. To further improve the SSA and porosity, we used controlled chemical activation to fabricate microstructures on the bio-carbon. As shown in Fig. 1(II), the pretreated sisal leaf adsorbed ions from the solution containing lithium ions to serve as a precursor for use with activating agents. The pre-prepared sisal leaves were carbonized at high temperature to obtain the free-standing bio-carbon with a porous substructure (CarbonS-2). The types of activating agents and the activating agent/precursor ratio are known to be important factors for the manipulation of the porous structure during the chemical activation process36. Here, an optimized mixing solution of lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate was used as an activating agent (see Supporting Information Figure S1 for the detailed procedure). The freeze-dried sisal leaves were immersed into the mixing solution to absorb the Li+, OH− and CO32− ions. During the high-temperature treatment process, LiOH and Li2CO3 reacted with carbon to produce Li2O, H2O, CO, CO2, and organic molecules, and the framework of bio-carbon was etched to produce the rich porous microstructures.

Figure 1. Schematic of the CarbonS fabrication.

Method (I) is direct carbonization to obtain the bio-carbon material monolith (CarbonS-1) that inherits the natural hierarchical texture of sisal leaves. Method (II) is to manipulate the free-standing bio-carbon with a rich porous substructure by carbonization via controlled chemical activation (CarbonS-2).

Figure 2. SEM images of the longitudinal surface (I, II, III) and the cross-section (IV, V) of CarbonS-1 (a-) and CarbonS-2 (b-).

CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 inherited the pristine hierarchical porous frameworks of sisal leaves. CarbonS-2 was etched by controlled chemical activation to manipulate the macro/mesoporous substructures.

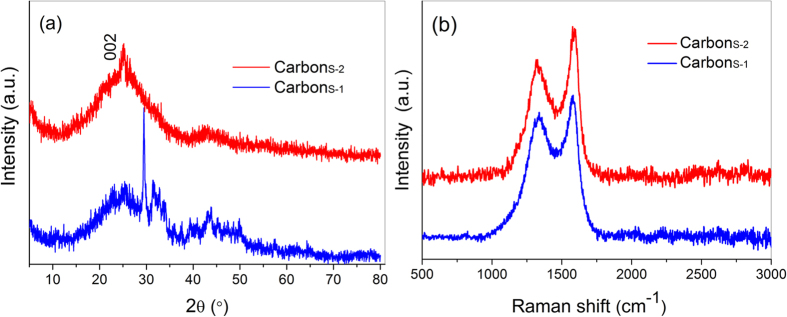

Figure 3. XRD patterns (a) and Raman spectra (b) of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2, which exhibit partial graphitic structures after carbonization.

The SEM images of CarbonS-2 presented in Fig. 2b(I,II,III) show that the connected porous frameworks with various pore sizes are similar to the morphology of CarbonS-1, demonstrating that CarbonS-2 also inherited the hierarchical structure of sisal leaves. Specifically, the introduction of moderate activating agents did not destroy the pristine skeleton of sisal leaves during the carbonization because of the controllable etching of the mixed activating agent of LiOH and Li2CO3. The surfaces of the CarbonS-2 pore walls differ from those of CarbonS-1, exhibiting a rich porous structure (Fig. 2b(III,V)). The thickness of CarbonS-2 was approximately 600 μm (Fig. 2b(IV)), which is considerably larger than the 150 μm thickness of CarbonS-1. Higher-magnification SEM cross-section images show the pore walls densely interspersed with pores at the meso/microscale (Fig. 2b(III,IV)). These macro/mesopores dramatically improve the SSA and also act as ion-buffering reservoirs that shorten the diffusion distance of ions during charge/discharge processes and promote a high rate capability. Although chemical activation significantly changes the morphology of bio-carbons, elemental analysis demonstrated that the CarbonS-2 components were similar to the CarbonS-1 components: the carbon content of CarbonS-2 (C: 77.8 wt%) was slightly lower than that of CarbonS-1 (C: 80.1 wt%, Table S1).

The XRD patterns in Fig. 3(a) show a pronounced broad (002) peak at 2θ = 25.4°, indicating that CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 both possess good graphitic structure even after chemical activation37. The interlayer spacing, d002, was calculated to be 0.350 nm using the Bragg equation; this interlayer spacing is slightly greater than that of natural graphite (0.335 nm) because of heteroatom doping in the graphite sheet38. The sharp diffraction peak at 2θ = 29.7° in the XRD pattern of CarbonS-1 is attributed to the salt derived from biological electrolytes in sisal leaves. This phenomenon is consistent with the higher-magnification SEM images (Fig. 2a(III,IV)), which display some salt particles. By contrast, no sharp peaks appear in the XRD pattern of CarbonS-2, implying that the residual lithium compounds originating from activating agents during carbonization were completely removed in the water-washing process.

Raman spectroscopy is a very versatile tool for characterizing carbon materials. It is sensitive to key materials properties such as doping and defect density. As shown in Fig. 3(b), two typical peaks were observed in the Raman spectra at approximately 1338 and 1589 cm−1; these peaks are attributed to the well-defined D-band and G-band, respectively39. The D-band arises from the doubly resonant disorder, and its intensity is strongly associated with the degree of disorder in the graphitic plane40. For the bio-carbons derived from sisal leaves, oxygen-rich groups in the biomass give rise to defects and the other phenomena such as nitrogen doping during carbonization, giving rise the disordered configurations. The G-band is related to the in-plane vibration of sp2 carbon atoms, which is a doubly degenerate (TO and LO) phonon mode (E2g symmetry) at the Brillouin zone centre41. The sharp G-bands lead to an intensity ratio between the G-band and D-band (IG/ID) of 1.17 and 1.30 for CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2, respectively, demonstrating the relatively high graphitization of these materials. Therefore, the moderate chemical activation did not destroy the graphitic structure of CarbonS-2.

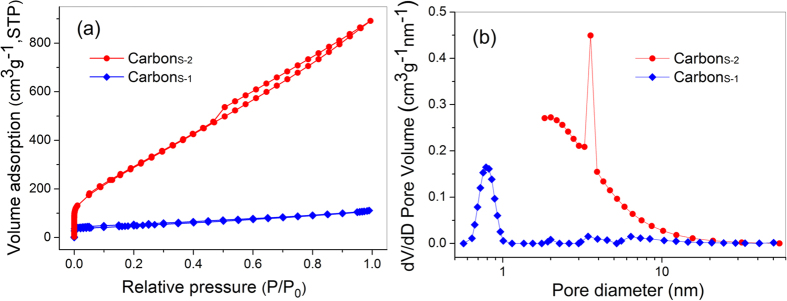

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms reveal differences in the pore structures and SSAs of the two samples (Fig. 4). CarbonS-1 exhibits a type-I isotherm with a H4 hysteresis loop, indicating a microporous structure42. On the basis of the Brunauer−Emmett−Teller (BET) equation, its SSA was estimated to be 171 m2 g−1, which is much higher than the SSA of some carbon materials not subjected to hydrothermal or chemical activated process35,43. The pore size calculated from adsorption data using the nonlocal density functional theory (DFT) method revealed that the CarbonPH-1 pore size distribution was centred at 0.8 nm, with a range of approximately 0.5–2.0 nm and a pore volume of 0.155 cm3 g−1. These results confirm the aforementioned SEM analysis results that indicated smooth pore walls because the pore size distribution closed the micropores that were not observed at current magnifications. After controlled chemical activation, the CarbonS-2 isotherm exhibited type-IV characteristics with a H3 hysteresis loop, which is associated with the occurrence of capillary condensation (Fig. 4a), indicating the presence of mesopores42,44. The BET surface area and the Langmuir surface area for CarbonS-2 were 1173 and 1985 m2 g−1, respectively. The total pore volume was 1.37 cm3 g−1. Moreover, the pore size distribution was narrow (Fig. 4b), with the predominant and average pore sizes calculated from the adsorption branch being ∼4.0 and ∼3.8 nm, respectively. The mesopore structure closing the micropores results in both shorter diffusion pathways of ion transport and an excellent BET surface area, improving the accessible SSA33,45,46. The higher accessible SSA and shorter diffusion pathways contribute to the high specific capacitance and high rate capability of the electrodes in supercapacitors.

Figure 4. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm (a) and pore-size distribution (b) of CarbonS.

The BET surface areas of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 are 171 and 1173 m2 g−1, respectively. The total pore volume and predominant pore size of CarbonS-2 are 1.37 cm3 g−1 and 4 nm, respectively.

Electrochemical performance

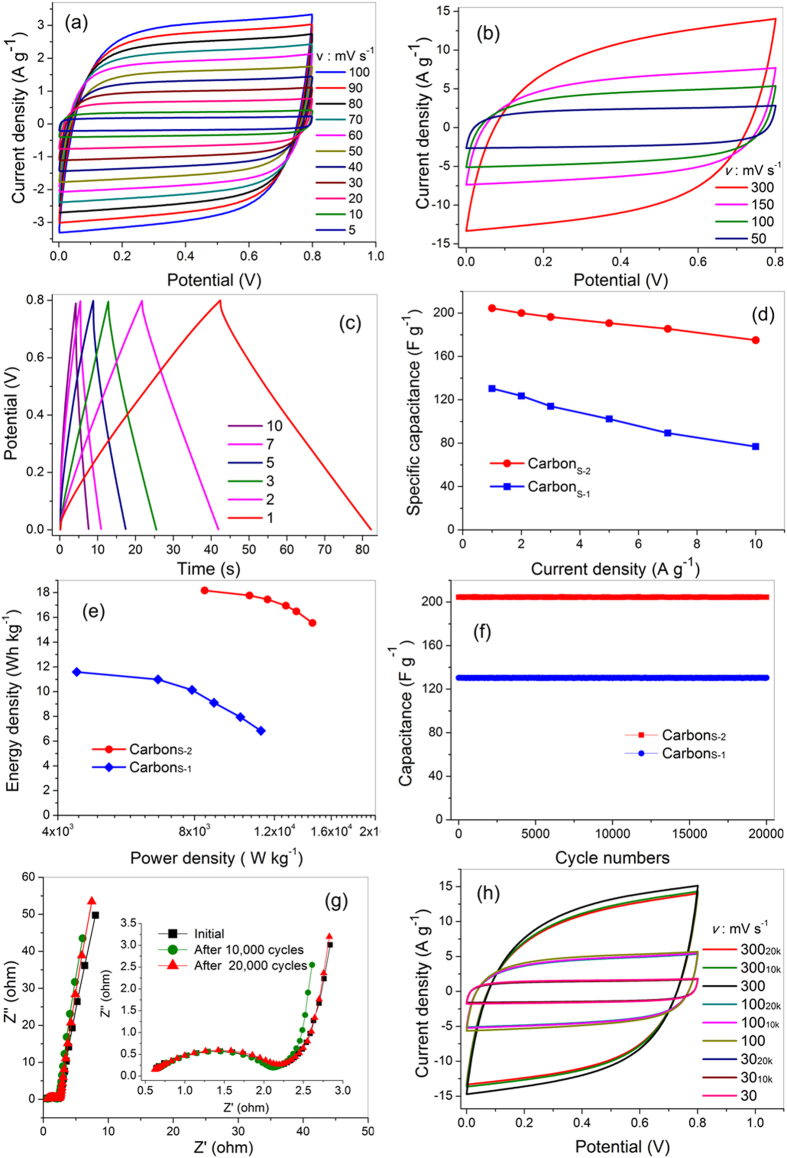

The electrochemical performances of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 were analysed in a symmetric two-electrode configuration. The cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the two samples exhibited perfect rectangle-like shapes, indicating a capacitive response derived from the EDL capacitance (Fig. 5a,b). The specific capacitance derived from the CV curves of CarbonS-1 slowly decreased with increasing scan rate (Figure S2b), demonstrating that its rate capability could be reasonably attributed to the facilitation of ionic diffusion by the hierarchical structures. Furthermore, CarbonS-1 exhibits stable capacitance characteristics. The capacitance and impedance are almost unchanged even for a three-fold increase in mass (Figure S2 c, d), making CarbonS-1 suitable for the fabrication of large-sized electrodes. Compared with the areas under the curves in the cyclic voltammogram of CarbonS-1, those in the cyclic voltammogram of CarbonSH-2 are clearly larger because of the improvement of the SSA by chemical activation and the resultant enhancement of the capacitance. Moreover, even at a fast scan rate of 300 mV s−1, the CV curve retained its rectangular shape, indicating the good power capability of CarbonS-2.

Figure 5. Electrochemical performance of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2: Cyclic voltammograms (a,b) of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2; galvanostatic charge/discharge curves (c) of CarbonS-2; rate capability (d), Ragone plots (e) and cycle life (d) of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2; Nyquist plots (g) and cyclic voltammograms (h) of CarbonS-2 at the first, 10,000th and 20,000th cycles.

The galvanostatic charge/discharge curves exhibited a symmetrical triangular shape with a small IR drop (Fig. 5c), confirming the EDL capacitance. The IR drop was very small and did not obviously change with increasing scan rates, indicating the relatively low internal resistance and high Coulomb efficiency of the supercapacitor. These phenomena are closely related to the electrical conductivity of the electrode47. The conductivity of CarbonS-2, as determined using the four-point probe method, was 10 S cm−1, thereby verifying the good conductivity of this material. The galvanostatic charge/discharge curves also demonstrated the enhanced power capability of CarbonS-2. The capacitance slowly decreased from 204.1 to 175.0 F g−1 as the rate was increased from 1 to 10 A g−1. Thus, the retention ratio was 85%, and the residual capacitance of CarbonS-1 was 58 wt% (Fig. 5d). These results are attributed to the inherent hierarchical texture of bio-carbon inherited from sisal leaves and to the microstructures that originated from chemical activation. The hierarchal texture provides effective channels for fast ion transfer, facilitating the good rate capability. The chemical manipulation enabled modification of the multiscale pores, leading to a larger accessible SSA and to shorter diffusion pathways; these effects promote the adsorption of additional ions at the electrode–electrolyte interface and faster mass transport. The Ragone plots in Fig. 5e show that the modified hierarchical structure of CarbonS-2 gives rise to the higher specific energy density and power density observed experimentally. At 10 A g−1, the energy density of CarbonS-2 was more than two times that of CarbonS-1 and was accompanied by a greater power capability.

The CarbonS electrodes exhibited outstanding cycling stability as double-layer capacitors (Fig. 5f), similar to the performance of other reported carbon materials48,49. The bio-carbons investigated in this work generally contain some hetero atoms such as nitrogen and oxygen (Table S1), promoting their wettability. However, on the basis of the aforementioned CV and galvanostatic charge/discharge curves, the nitrogen or oxygen functional groups attached on the bio-carbons appeared to barely affect the Faradic reactions during the charge/discharge processes. Thus, their pseudocapacitance can be ignored. Because the EDL storage mechanism does not involve the ions’ insertion/deinsertion, the devices theoretically have lifetimes that exceed one million cycles. However, the physicochemical properties and intrinsic structure of the electrode materials profoundly affect their cycling stability. Fortunately, the developed bio-carbons exhibit a stable intrinsic texture and physicochemical properties. After 20,000 cycles, the capacitances of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 decreased on slightly. The SEM images collected after 10,000 and 20,000 cycles revealed that the original hierarchical structure (Figure S3) of the CarbonS-2 electrode was completely preserved. High-magnification SEM images revealed the presence of a homogeneous distribution of electrolyte salt particles on the CarbonS-2 surface. These phenomena demonstrate that the electrolyte can effectively diffuse onto the pore walls during the charge/discharge processes.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to investigate the change in resistance during the different galvanostatic charge/discharge cycling procedures. The equivalent series resistances (RS) and the charge transfer resistances (RCT) values of CarbonS-2 determined from the EIS measurements were smaller than those of CarbonS-1 (Fig. 5g, S2d), demonstrating that the chemical activation further improved the wettability to reduce the contact resistance and added mesoporous features to optimize the ionic diffusion pathways. Electrode materials with small RS and RCT values tend to enhance the power density of devices; thus, CarbonS-2 exhibited greater power capability than CarbonS-1 (Fig. 5e).

The 45° sloped portion of the Nyquist plots, referred to as the Warburg resistance, is a result of the frequency dependence of ion transport in the electrolyte50,51. The inherited hierarchical structure of the bio-carbons offers effective ion diffusion pathways; thus, the bio-carbons exhibited small Warburg resistances. In the low-frequency region, the Nyquist plots of CarbonS show nearly vertical lines, indicating a pure capacitive behaviour52. The magnitude and slope of the impedance are associated with ionic diffusion in porous electrodes19. CarbonS-2, with its rich mesoporous structure, exhibited a smaller magnitude of impedance and more ideal capacitor behaviour. Moreover, the RS and RCT of CarbonS-2 barely changed with increasing number of charge/discharge cycles, confirming that the substructure and physicochemical properties were stable and did not deteriorate during the charge/discharge processes. The CV curves at 30, 100 and 300 mV s−1 after various numbers of cycles exhibit almost the same shapes and areas, further confirming the high stability of the electrochemical performance of CarbonS-2.

Conclusions

We introduced the top-down approach for the fabrication of free-standing bio-carbon derived from sisal leaves by carbonization with controlled chemical activation. The bio-carbon inherited the pristine hierarchical texture of the sisal leaves and exhibited a rich porous substructure; the bio-carbon therefore exhibited a high SSA and a narrow pore size distribution. Because of its relatively high graphitization, this bio-carbon material also exhibited a high conductivity. As electrodes for supercapacitors, the free-standing bio-carbon exhibited a high specific capacitance of 204.1 F g−1 at 1 A g−1; good rate capability, as indicated by a residual initial capacitance of 85.5% at 10 A g−1; and a long cycle life. These results are attributed to the larger accessible SSA and to the effective diffusion pathways derived from the biomass, which promote greater ionic adsorption at the electrode–electrolyte interface and faster ionic transport, respectively. Therefore, our top-down approach using freeze-drying pre-preparation and controlled chemical activation offers an innovative method for the fabrication of bio-carbons that can be used as high-performance electrodes for supercapacitors.

Experimental

Synthesis of CarbonS

The cuticular wax of sisal leaves was removed and subsequently freeze-dried to preserve its pristine structure. The leaves were fixed by carbon fibre onto a plate of aluminium oxide and carbonized at 1000 °C in a tube furnace at a heating rate of 3 °C/min under a high-purity argon atmosphere. The precursors were annealed for 30 min at 1000 °C under the same atmosphere to obtain the bio-carbon materials (denoted CarbonS-1).

After the cuticular wax was removed and the sisal leaves were freeze-dried, the pretreated sisal leaves adsorbed ions from a mixed saturated solution of lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate and were dried again. The pre-prepared leaves were carbonized under the aforementioned carbonization conditions to obtain the modified bio-carbon materials containing lithium compounds. For complete removal of residual lithium compounds, the sample was immersed in deionized water at 90 °C under high pressure for 24 h and was then washed until the wash solution was neutral (denoted as CarbonS-2).

Materials characterization and electrochemical measurements

The morphology and structure of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Hitachi S-4800 and Quanta-250). The crystalline structure of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 was characterized by X-Ray diffraction (XRD) measurements on a Rigaku D-max-2500 diffractometer using nickel-filtered Cu-Kα radiation with λ = 1.5406 Å. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet 8700 FTIR spectrometer. The spectra in the 4000–400 cm−1 range were collected by averaging of 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm−1. Raman spectra were recorded using a LabRam-1B Raman spectroscope with He−Ne laser excitation at 632.8 nm; the scan time was 50 s. The BET surface area, pore volume and pore width of the bio-carbons were characterized by nitrogen adsorption using a surface area and porosity analyser (Quantachrome Autosorb-iQ). The specific surface area (SSA) was analysed using the BET method in the P/P0 range from 0.03 to 0.3; the pore volume was determined from the adsorption amount at P/P0 = 6.3 × 10−7 − 9.5 × 10−1, and the mesoporous volume and the mesoporous radius were obtained by the Barrett−Joyner−Halenda (BJH) method. The conductivities of CarbonS-1 and CarbonS-2 at room temperature were measured using a typical four-probe method (LORESTA-EP MCP-T360).

Three-electrode and two-electrode cell configurations were employed to measure the electrochemical performance. CarbonS were first punched into wafer electrodes. Two nearly identical (by weight and size) electrodes were then assembled in a test cell. Electrochemical evaluations were performed on an auto-lab electrochemical workstation. The cyclic voltammograms and galvanostatic charge/discharge curves were collected from 0 to 0.8 V using 1 M LiOH as the electrolyte. EIS was performed for frequencies ranging between 100 kHz and 10 mHz using a perturbation amplitude of 5 mV versus the open-circuit potential. The electrochemical cycling tests of the products were performed using a LAND testing system; the electrodes were cycled more than 20,000 times.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, Y. et al. A top-down approach for fabricating free-standing bio-carbon supercapacitor electrodes with a hierarchical structure. Sci. Rep. 5, 14155; doi: 10.1038/srep14155 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support of this work is provided by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (13B10624), NSFC (51233001, 51173024), SRFDP (20110075110009), 111 Project (111-2-04).

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.Z.L. and Q.H.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. J.X.Z. and J.L., prepared the bio-carbons and the free-standing electrodes for supercapacitors, and conducted the electrochemical measurements. T.X. carried out the SEM measurement. Y.Z.L., Q.H.Z. and X.Z. wrote the manuscript. Competing financial interests: the authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Simon P. & Gogotsi Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 7, 845–54 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard A. J., Faulkner L. R., Swain E. & Robey C. Fundamentals and applications. Harris, D.: New Yorke, USA, (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Kotz R. & Carlen M. Principles and applications of electrochemical capacitors. Electrochim. Acta 45, 2483–2498 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Ma J. & Li C. Hierarchical porous NiCo2O4 nanowires for high-rate supercapacitors. Chem. Commun. 48, 4465–4467 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma R. et al. Large-scale fabrication of hierarchical α-Fe2O3 assemblies as high performance anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. CrystEngComm 14, 7882–7887 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Mai L. Q. et al. Hierarchical MnMoO4/CoMoO4 heterostructured nanowires with enhanced supercapacitor performance. Nat. Commun. 2, 381–285 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y. et al. Synergy of W18O49 and polyaniline for smart supercapacitor electrode integrated with energy level indicating functionality. Nano Lett. 14, 2150–2156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. L. et al. An ultrafast nickel-iron battery from strongly coupled inorganic nanoparticle/nanocarbon hybrid materials. Nat. Commun. 3, 917–924 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. et al. Carbon-based supercapacitors produced by activation of graphene. Science 332, 1537–41 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Lee P. S. & Li C. 3D carbon based nanostructures for advanced supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 41–53 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Futaba D. N. et al. Shape-engineerable and highly densely packed single-walled carbon nanotubes and their application as super-capacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 5, 987–94 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Hayner C. M., Kung M. C. & Kung H. H. Flexible holey graphene paper electrodes with enhanced rate capability for energy storage applications. ACS nano 5, 8739–49 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Zhu J., Qiu L. & Li D. Bioinspired effective prevention of restacking in multilayered graphene films: towards the next generation of high-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 23, 2833–8 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Cheng C., Wang Y., Qiu L. & Li D. Liquid-mediated dense integration of graphene materials for compact capacitive energy storage. Science 341, 534–7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaempgen M., Chan C. K., Ma J., Cui Y. & Gruner G. Printable thin film supercapacitors using single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 9, 1872–6 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y. J. et al. All-solid-state flexible supercapacitors fabricated with bacterial nanocellulose papers, carbon nanotubes, and triblock-copolymer ion gels. ACS nano 6, 6400–6406 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. L. et al. Highly conductive and porous activated reduced graphene oxide films for high-power supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 12, 1806–12 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. Y. et al. High-Performance Supercapacitors Based. ACS nano 5, 436–442 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia B. Materials Synthesis and Characterization for Micro-supercapacitor Applications. Ph.D Thesis, University of California, Berkeley (2013).

- Aricò A. S., Bruce P., Scrosati B., Tarascon J. M. & van Schalkwijk W. Nanostructured materials for advanced energy conversion and storage devices. Nat. Mater. 4, 366–77 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. W. et al. High-power lithium batteries from functionalized carbon-nanotube electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 531–7 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Smart, Stretchable Supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 26, 4444–4449 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H. et al. Crab shells as sustainable templates from nature for nanostructured battery electrodes. Nano Lett. 13, 3385–90 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W. et al. Pyrolysis of cellulose under ammonia leads to nitrogen-doped nanoporous carbon generated through methane formation. Nano Lett. 14, 2225–9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White R. J., Antonietti M. & Titirici M. M. Naturally inspired nitrogen doped porous carbon. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 8645–8650 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q. et al. High-performance all-carbon yarn micro-supercapacitor for an integrated energy system. Adv. Mater. 26, 4100–6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J. et al. DNA hydrogel-based supercapacitors operating in physiological fluids. Sci. Rep. 3, 1282 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A. et al. Activated carbons derived from coconut shells as high energy density cathode material for Li-ion capacitors. Sci. Rep. 3, 3002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Wu D. & Fu R. Carbon microfibers with hierarchical porous structure from electrospun fiber-like natural biopolymer. Sci. Rep. 3, 1119–1123 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki M., Konno H. & Tanaike O. Carbon materials for electrochemical capacitors. J. Power Sources 195, 7880–7903 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y. et al. Carbon materials for chemical capacitive energy storage. Adv. Mater. 23, 4828–50 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillo-Rodenas M. A., Cazorla-Amoros D. & Linares-Solano A. L. Understanding chemical reactions between carbons and NaOH and KOH: An insight into the chemical activation mechanism. Carbon 41, 267–275 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. W., Li F., Liu M., Lu G. Q. & Cheng H. M. 3D aperiodic hierarchical porous graphitic carbon material for high-rate electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. 120, 379–382 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwaikambo L. Y. & Ansell M. P. The effect of chemical treatment on the properties of hemp, sisal, jute and kapok fibres for composite reinforcement. Die Angew. Makromol. Chemie. 272, 108–116 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L. et al. Sustainable nitrogen-doped carbonaceous materials from biomass derivatives. Carbon 48, 3778–3787 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. Nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanosheets as low-cost, high-performance anode material for sodium-ion batteries. ChemSusChem 6, 56–60 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Yan L. & Bangal P. R. Preparation of graphene by the rapid and mild thermal reduction of graphene oxide induced by microwaves. Carbon 48, 1146–1152 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhao X., Yu P. & Zhang Q. Oriented arrays of polyaniline nanorods grown on graphite nanosheets for an electrochemical supercapacitor. Langmuir 29, 493–500 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene D. et al. Doped graphene sheets as anode materials with superhigh rate and large capacity for lithium ion batteries. ACS nano 5, 5463–71 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berciaud S., Ryu S., Brus L. E. & Heinz T. F. Probing the intrinsic properties of exfoliated graphene: raman spectroscopy of free-standing monolayers. Nano Lett. 9, 346–52 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. et al. One-pot synthesis of fluorescent carbon graphene by the exfoliation of graphite in ionic liquids. ACS nano 3, 2367–2375 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M. & Jaroniec M. Gas adsorption characterization of ordered organic-inorganic nanocomposite materials. Chem. Mater. 13, 3169–3183 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Titirici M.-M. & Antonietti M. Chemistry and materials options of sustainable carbon materials made by hydrothermal carbonization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 103–116 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Shi J., Wang L. & Yan D. Preparation and characterization of ZnO clusters inside mesoporous silica. Chem. Mater. 12, 1408–1413 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Shang M. et al. 3D Bi2WO6/TiO2 Hierarchical heterostructure: controllable synthesis and enhanced visible photocatalytic degradation performances. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 14727–14731 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q. et al. A honeycomb-like porous carbon derived from pomelo peel for use in high-performance supercapacitors. Nanoscale 6, 13831–13837 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y. et al. All-graphene core-sheath microfibers for all-solid-state, stretchable fibriform supercapacitors and wearable electronic textiles. Adv. Mater. 25, 2326–31 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin W. H., Jeong H. M., Kim B. G., Kang J. K. & Choi J. W. Nitrogen-doped multiwall carbon nanotubes for lithium storage with extremely high capacity. Nano Lett. 12, 2283–8 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kady M. F. & Kaner R. B. Scalable fabrication of high-power graphene micro-supercapacitors for flexible and on-chip energy storage. Nat. Commun. 4, 1475–1483 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. et al. A high performance O2 selective membrane based on CAU-1-NH2 @polydopamine and the PMMA polymer for Li–air batteries. Chem. Commun. 51, 4364–4367 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z. Y., Lu A. H., Xu Y. Y., Zhang J. T. & Li W. C. Ionic liquid-assisted synthesis of microporous carbon nanosheets for use in high rate and long cycle life supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 26, 3700–5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Yu Z., Neff D., Zhamu A. & Jang B. Z. Graphene-based supercapacitor with an ultrahigh energy density. Nano Lett. 10, 4863–4868 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.