Abstract

New geochronological and geochemical data on magmatic activity from the India-Asia collision zone enables recognition of a distinct magmatic flare-up event that we ascribe to slab breakoff. This tie-point in the collisional record can be used to back-date to the time of initial impingement of the Indian continent with the Asian margin. Continental arc magmatism in southern Tibet during 80–40 Ma migrated from south to north and then back to south with significant mantle input at 70–43 Ma. A pronounced flare up in magmatic intensity (including ignimbrite and mafic rock) at ca. 52–51 Ma corresponds to a sudden decrease in the India-Asia convergence rate. Geological and geochemical data are consistent with mantle input controlled by slab rollback from ca. 70 Ma and slab breakoff at ca. 53 Ma. We propose that the slowdown of the Indian plate at ca. 51 Ma is largely the consequence of slab breakoff of the subducting Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere, rather than the onset of the India-Asia collision as traditionally interpreted, implying that the initial India-Asia collision commenced earlier, likely at ca. 55 Ma.

Continental collision is a dramatic expression of the dynamic nature of the Earth and has long-term impacts on atmosphere and ocean circulation patterns, and on the development and stability of the continental lithosphere. One of the most prominent collisions today is the ongoing interaction between the Indian and Asian continents. However, the timing of the initial India-Asia collision remains uncertain with suggestions ranging from 70 to 34 Ma1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. This uncertainty reflects in part the differing approaches used to define collision.

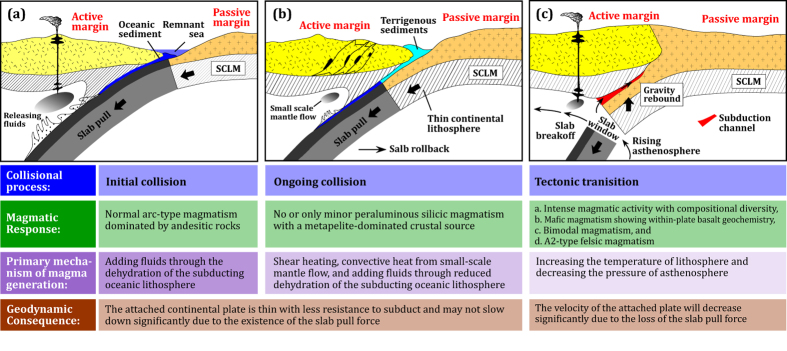

Continental collision is the natural consequence of plate tectonics involving oceans opening and closing and is driven by a variety of forces most notably the descent of oceanic lithosphere at subduction zones (i.e. slab pull)10,11. Such understanding, together with the primary mechanisms of magma generation (i.e., adding fluids, increasing temperature, and decreasing pressure), allows us to place constraints on the relationship between collisional processes and magmatic responses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic sequence of the relationship between collisional processes and magmatic responses in collision zones.

This figure is generated by Di-Cheng Zhu, using Adobe Illustrator CS4 created by the Adobe Illustrator Team under an open license.

(1) Initial collision, takes place at the initial contact of crust between two continents (Fig. 1a). At this stage, oceanic lithosphere continues to subduct and dehydrates (releasing fluids), resulting in the generation of normal continental arc magmatism dominated by andesitic rocks as seen in the Andes. (2) Ongoing collision, involves the thin passive continental lithosphere being dragged by the subducting oceanic lithosphere (slab pull) (Fig. 1b). Minor syn-collisional magmatism during this stage is mostly peraluminous and derived from a metapelite-dominated source within the middle-upper crust due to reduced dehydration of the subducting oceanic lithosphere (releasing fluids), convective heat from small-scale mantle flow12, and shear heating13. (3) Tectonic transition, occurs due to the buoyancy of the lower plate continental lithosphere counteracts the effects of slab-pull of the oceanic lithosphere resulting in their separation (slab breakoff14) (Fig. 1c). After slab breakoff, the collision zone transitions into an intracontinental setting. Slab breakoff will open a slab window and consequently trigger partial melting of differing magma source regions (by increasing the temperature of lithosphere and decreasing the pressure of asthenosphere), producing intense magmatism with compositional diversity (defined here as post-collisional magmatism) (including basaltic magmatism showing within-plate basalt geochemistry, bimodal magmatism, and anorogenic felsic magmatism, etc.)15,16. From initial to ongoing collision, the surface plate may not slow down significantly as the attached continental lithosphere is thin with less resistance to subduct due to the descent of the dense oceanic lithosphere (slab pull), whereas after slab breakoff during the tectonic transition the velocity of the surface plate is expected to decrease significantly due to the loss of the slab pull force that is the main driving force of plate motion10,11.

The evolving magmatic record from ongoing subduction to collision, slab breakoff, and further continental lithospheric interaction provides a framework to evaluate continent-continent collision. This is because slab breakoff will postdate the initial continent-continent collision by several to ten million years, depending on convergence velocity, subducting slab dip8, and shape of the colliding margins. Thus, defining the timing of slab breakoff, which can be identified on the integration of geological, geochemical, geochronological, and geophysical methods15,16,17,18,19,20, provides an important time-stamp on the sequence of collision-related events.

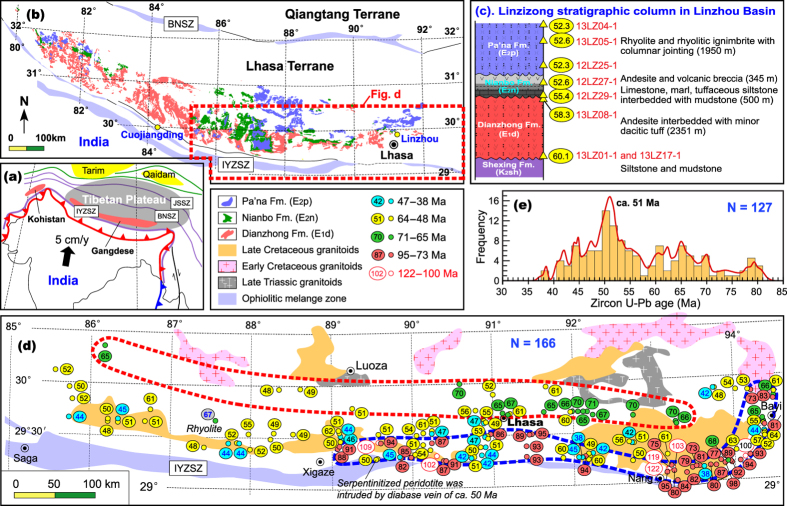

The Gangdese arc in southern Tibet (Fig. 2a), which records the subduction of the Neo-Tethyan oceanic lithosphere and subsequent India-Asia collision21, allows a direct test of our petrological approach to resolving the timing of India-Asia collision. This is because the voluminous Linzizong volcanic rocks (Fig. 2b,c) and coeval intrusive rocks of the Gangdese arc (Fig. 2d) range in age from 70 to 40 Ma22, straddling the interpreted timing of collision1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. We provide the first comprehensive dataset on the age and geochemistry of these rocks enabling us to tightly constrain the progressive history of convergence and collision, including redefining the timing of the latter.

Figure 2. Tectonic framework of the Tibetan Plateau and the Lhasa Terrane.

(a) Showing the Gangdese arc in the context of the Tibetan Plateau. IYZSZ = Indus-Yarlung Zangbo suture zone, BNSZ = Bangong-Nujiang suture zone, JSSZ = Jinsha suture zone. (b) The distribution of the Linzizong volcanic rocks. (c) The stratigraphic column of the Linzizong volcanic rocks in Linzhou Basin4. The filled ovals with numerals are host-rock crystallization ages in Ma using in situ zircon secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) U-Pb dating method (see supplementary Table S1 for sample details). (d) The distribution of intrusive rocks in the Gangdese arc. The filled circles indicate sample locations, numerals within ovals are host-rock crystallization ages in Ma using in situ zircon LA-ICPMS U-Pb dating method (see supplementary Table S2 for sample details). Five groups of zircon ages are recognized on the basis of spatial variation of magmatism and different magmatic origin22. This figure is generated by Di-Cheng Zhu, using Adobe Illustrator CS4 created by the Adobe Illustrator Team under an open license. (e) Histogram of crystallization ages (Ma) of the intrusive rocks (85–94°E) from the Gangdese Batholith. The red line represents frequency curve. Age data used in this histogram are the crystallization ages defined by the youngest group of zircon analyses of each sample. The bin width was set at 1.5 Ma to accommodate average age uncertainties of 1.1 Ma (2σ; Table S3). Only one age datum is selected for each pluton if between-sample age difference is lower than 3 Myrs. If this difference is more than 3 Myrs, this pluton is considered to emplace at different pulses and thus the different emplacement ages are used to construct the histogram.

Spatial, temporal and compositional changes of the Gangdese arc

The Linzizong volcanic rocks (Fig. 2b) extend for more than 1000 km along the southern Lhasa Terrane and are well exposed in Linzhou Basin (Fig. S1). In this basin, the lower unit of the Linzizong volcanic rocks (Dianzhong Formation) is dominated by thick andesitic rocks (Fig. 2c), which unconformably overlie strongly folded Upper Cretaceous siltstone and mudstone (Fig. S1). The middle unit (Nianbo Formation) is characterized by siltstone, marl, and limestone interbedded with andesitic rocks (Fig. 2c). The upper unit (Pa’na Formation) is characterized by the presence of thick rhyolite and rhyolitic ignimbrite (Fig. 2c) with columnar jointing (Fig. S1). We undertook SIMS (secondary ion mass spectrometry) U-Pb zircon dating23 of magmatic rocks from the stratigraphic boundaries of each formation (Fig. S1). Sample details, zircon U-Pb age data, and geochemical data are provided in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplementary material. Our new age data are shown in red ovals with numerals in Fig. 2c and S1 and are summarized in Table 1. The SIMS U-Pb zircon age data of two samples (13LZ01-1 and 13LZ17-1) from the lowermost Dianzhong Formation (60.2 ± 0.6 and 60.2 ± 0.8 Ma, respectively) and of one sample (13LZ08-1) from the uppermost Dianzhong Formation (58.3 ± 1.3 Ma) indicate that the Dianzhong andesitic volcanism was most likely active during 60.2–58.3 Ma. One sample (12LZ29-1) from the lowermost Nianbo Formation (55.4 ± 0.5 Ma) and two samples (12LZ27-1 and 13LZ16-1) from the Upper Nianbo Formation (52.6 ± 0.4 and 52.7 ± 1.9 Ma, respectively) provide age constraint on the Nianbo Formation of 55.4–52.6 Ma. This is very compatible with the age data obtained from two marl samples (13LZ13-1 and 13LZ14-1) from the lower Nianbo Formation (54.4 ± 0.5 and 54.5 ± 0.7 Ma). Three samples from the Lower (12LZ25-1), Middle (13LZ05-1), and Uppermost (13LZ04-1) Pa’na Formation give SIMS U-Pb zircon ages of 52.3 ± 0.5, 52.6 ± 0.4, and 52.3 ± 0.6 Ma, indistinguishable within analytical errors. These data precisely bracket the duration of each formation of the Linzizong volcanic rocks from the Linzhou Basin: 60.2–58.3 Ma for the Dianzhong Formation, 55.4–52.6 Ma for the Nianbo Formation, and 52.6–52.3 Ma for the Pa’na Formation. Thus the duration of magmatic activity is some 8 m.y. defined by SIMS zircon U-Pb dating and differs significantly from previous estimates of up to 25 m.y. based on laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) zircon U-Pb and Ar-Ar dating for the Dianzhong (69–61 Ma), Nianbo (61–54 Ma), and Pa’na (54–44 Ma) formations (see ref. 24 for age summary).

Table 1. Summary of new zircon U-Pb age data reported in this study for the Linzizong volcanic rocks in Linzhou Basin, southern Tibet.

| Formation | Sample | Rock Type | GPS position | Strata position | Datingmethod | Analyses | Age (Ma) | MSWD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pa’na Formation | 13LZ04-1 | Rhyolitic breccia | N30°00.643′, E91°08.810′ | Uppermost Pa’na | SIMS 1280 | 19 | 52.29 ± 0.61 | 2.5 |

| 13LZ05-1a | Rhyolitic ignimbrite | N30°00.137′, E91°08.882′ | Middle Pa’na | SIMS 1280 | 16 | 52.58 ± 0.40 | 1.3 | |

| 13LZ06-1 | Rhyolite | N29°59.964′, E91°08.700′ | Middle Pa’na | LA-ICPMS | 16 | 50.5 ± 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| 12LZ23-1 | Rhyolitic ignimbrite | N29°59.622′, E91°08.415′ | Middle Pa’na | LA-ICPMS | 16 | 49.7 ± 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| 12LZ25-1 | Rhyolite | N29°59.313′, E91°08.474′ | Lower Pa’na | SIMS 1280 | 13 | 52.27 ± 0.45 | 0.8 | |

| Nianbo Formation | 13LZ16-1 | Andesite | N29°59.078′, E91°11.209′ | Upper Nianbo | SIMS 1280 | 4 | 52.7 ± 1.9 | 2.0 |

| 12LZ27-1 | Rhyolitic tuff | N29°58.557′, E91°08.736′ | Upper Nianbo | SIMS 1280 | 15 | 52.64 ± 0.42 | 0.5 | |

| 13LZ13-1 | Marl | N29°58.812′, E91°11.159′ | Lower Nianbo | SIMS 1280 | 14 | 54.35 ± 0.47 | 1.1 | |

| 13LZ14-1 | Marl | N29°58.815′, E91°11.158′ | Lower Nianbo | SIMS 1280 | 10 | 54.45 ± 0.68 | 1.3 | |

| 12LZ29-1 | Rhyolite | N29°58.231′, E91°08.955′ | Lowermost Nianbo | SIMS 1280 | 14 | 55.37 ± 0.45 | 0.4 | |

| Dianzhong Formation | 13LZ08-1 | Andesite | N29°58.708′, E91°11.195′ | Uppermost Dianzhong | SIMS 1280 | 2 | 58.3 ± 1.3 | 0.01 |

| 12LZ06-1 | Dacite | N29°57.273′, E91°12.107′ | Lower Dianzhong | LA-ICPMS | 17 | 58.5 ± 0.5 | 0.4 | |

| 13LZ17-1b | Volcanic breccia | N29°57.292′, E91°13.048′ | Lowermost Dianzhong | SIMS 1280 | 13 | 60.23 ± 0.78 | 1.8 | |

| 13LZ01-1c | Andesite | N29°57.117′, E91°11.855′ | Lowermost Dianzhong | SIMS 1280 | 21 | 60.22 ± 0.61 | 2.0 |

aRhyolitic ignimbrite with well-developed columnar jointing.

bca. 50 cm above the angular unconformity between the Dianzhong and Shexing formations located ca. 78 m east of sample SH530022 that was dated by LA ICP-MS method at 68.7 ± 2.4 Ma (MSWD = 3.6)25.

cca. 20 cm above the angular unconformity between the Dianzhong and Shexing formations.

The Gangdese Batholith extends over 1500 km along the southern Lhasa Terrane (Fig. 2a). It is composed mainly of diorite and granodiorite, together with abundant mafic enclaves and dykes (Fig. S1). To obtain a comprehensive dataset with adequate spatial coverage, we collected a total of 127 samples with LA-ICPMS U-Pb zircon age data and 213 samples with whole-rock geochemical data on the 80–40 Ma intrusive rocks extending from longitude E85° to E95° along the strike of the batholith (Fig. 2d). Sample details, zircon U-Pb age data, and SiO2 contents are provided in Tables S3 and S4 in the supplementary material. These age data reveal that the >72 Ma magmatism was confined to a narrow belt in the south (blue dashed line, Fig. 2d), shifting northward at 71–65 Ma (red dashed line), then south at 64–48 Ma, which spread over a relatively broader area than the earlier activity, and is finally (47–38 Ma) largely restricted to its southern edge. These age data define a pulse of magmatic flare-up event at ca. 51 Ma along the entire length of the arc (Fig. 2e).

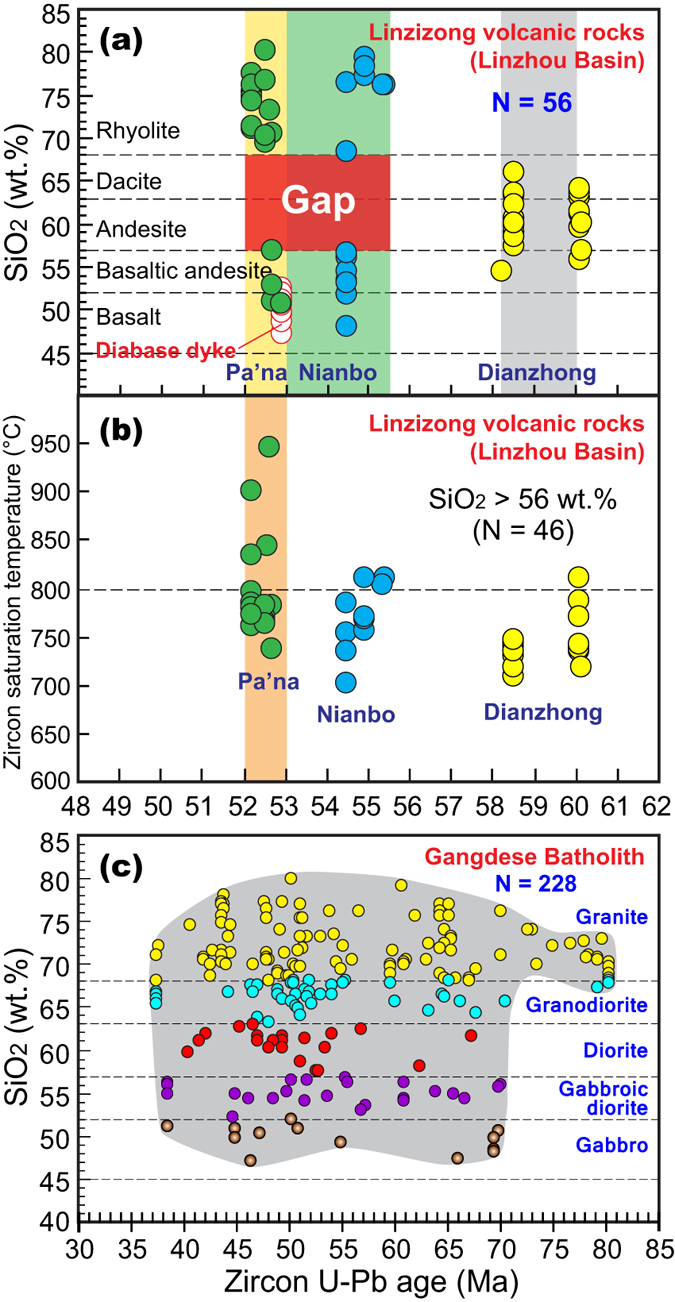

Changes in the chemical composition of the Linzizong volcanic rocks available from the Linzhou Basin and the Gangdese Batholith with time are illustrated by SiO2 variation and zircon saturation temperature26 against age (Fig. 3). Figure 3a shows that an andesite-dacite association in the Dianzhong Formation was followed by bimodal volcanic suites in both the Nianbo and Pa’na formations. Figure 3b reveals an increase in zircon saturation temperature at ca. 52 Ma documented by the rhyolitic rocks in the Pa’na Formation. Figure 3c illustrates felsic-dominated magmatism in the Gangdese Batholith during 80–73 Ma, followed by significant mafic magmatic activity at 70–43 Ma. It is important to note that bimodal magmatism coeval with or slightly younger than the Nianbo and Pa’na bimodal volcanism is most likely developed within the Gangdese Batholith as indicated by the presence of ca. 52–47 Ma gabbroic dykes that intruded into the coeval granitoid (Fig. S1g). The absence of compositional gap in the whole Gangdese Batholith (Fig. 3c) is probably the consequences of magma mixing between felsic and basaltic melts27 as indicated by the well-developed coeval mafic enclaves (Figs S1h, S1i, and S1j).

Figure 3. Changes in magmatic compositions with time in the Gangdese arc.

(a,b) Plots of SiO2 content versus age (Ma) and of zircon saturation temperature (°C) versus age (Ma) for the Linzizong volcanic rocks (see supplementary Table S4 for geochemical data). Zircon saturation temperatures were calculated from whole-rock compositions with SiO2 >56 wt.% following the method of Watson and Harrison (1983)26. (c) Plot of SiO2 content versus age (Ma) for the Gangdese Batholith (E85°–E95°) (see Table S5 for geochemical data). Note that this plot did not show a clear increase of mafic magmatism at ca. 51 Ma as indicated by the presence of well-developed mafic enclaves and dykes (Fig. S1); this inconsistency reflects sampling bias with mafic material underrepresented.

Discussion

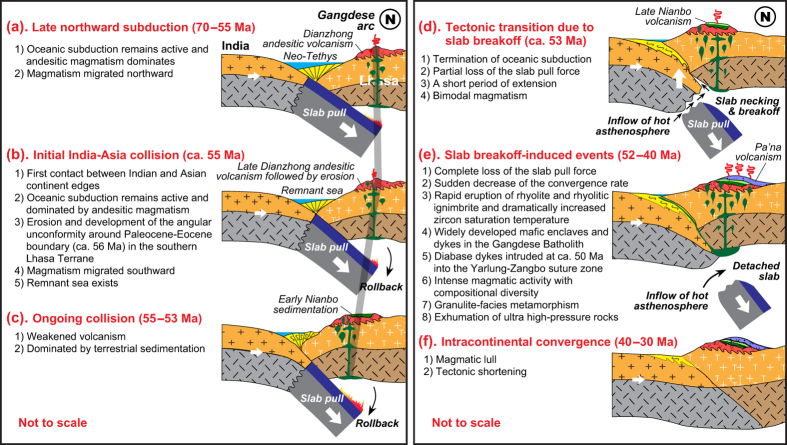

Temporal trends for enhanced mafic magmatism and increased zircon saturation temperature within the Linzizong volcanic rocks and Gangdese Batholith indicate an increased mantle heat input. It is emphasized that increased mantle input and coeval magmatic flare-up are difficult to attribute to a large scale change in the stress state of the lithosphere. This is because such change is a shallow response to deep mantle dynamics and is not an effective mechanism that will produce extensive magmatic activity. One possible explanation for higher mantle heat input at 70–43 Ma was the removal of the Asian lithosphere following tectonic shortening between 90 and 69 Ma28. However, to account for the southward migration of the magmatism from 72–65 Ma to 64–48 Ma (Fig. 2d), and significantly increased zircon saturation temperature at ca. 52 Ma and peak activity at ca. 51 Ma (Fig. 2e), we argue for slab steepening (Fig. 4a,b) and rollback (Fig. 4c) followed by slab breakoff (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4. Schematic illustrations showing the India-Asia collisional processes and resultant tectonomagmatic activity over the past 70–40 m.y. (not to scale).

This figure is generated by Di-Cheng Zhu, using Adobe Illustrator CS4 created by the Adobe Illustrator Team under an open license.

We infer that the breakoff of the Neo-Tethyan lithosphere occurred slightly earlier (e.g., ca. 53 Ma; Fig. 4d) than the rapid eruption of ca. 2 km thick rhyolite and rhyolitic ignimbrite (52.5–52.3 Ma) (Fig. 2c) documented by the Linzizong volcanic rocks (Pa’na Formation) and the magmatic flare-up event of ca. 51 Ma shown by the age relationships within the Gangdese Batholith (Fig. 2e). This inference is consistent with numerical modeling that indicates a short duration of slab breakoff (<2 Ma29) followed by intense magmatism as a result of the enhanced heat input from rising asthenosphere30. Other robust lines of evidence supporting our model of slab breakoff by this time include: (1) the occurrence of abundant 52–47 Ma mafic enclaves and dykes (Fig. S1) that suggest significantly increased contributions from the mantle; (2) the presence of ca. 52.5 Ma bimodal volcanic rocks (Fig. 3a) that points to partial melting of enriched metasomatic layers within lithospheric mantle and to crustal melting caused by thermotectonic effects as a result of slab breakoff15; (3) high Zr/Y ratios (3.7–6.8) of the basaltic lavas and dykes (ca. 52.9 Ma) in the Linzizong volcanic rocks (Table S2) that suggest input of subslab asthenospheric mantle16; and (4) dramatically increased zircon saturation temperature at ca. 52.5 Ma recovered by the rhyolitic rocks of the Pa’na Formation (Fig. 3b) that indicates the anomalously high heat input from the mantle.

The development of magmatic activity at 51–43 Ma in the Gangdese arc (Fig. 3b), as well as ca. 50 Ma diabase dykes that intrude serpentinitized peridotite within the Yarlung-Zangbo suture zone (Fig. 2d), is most likely the consequences of partial melting of differing magma source regions through increasing temperature of lithosphere and decreasing pressure of asthenosphere after slab breakoff. This interpretation is consistent with numerical modeling which indicates that hot asthenosphere continues to ascend and generates melt for several million years after slab breakoff (Fig. 4e)30. The shift in the whole-rock Nd and zircon Hf isotopic compositions towards negative values at ca. 50 Ma6,31,32 most likely reflects a profound change of the source regions associated with the involvement of slab edge materials of the Indian continent that had already been subducted to depths19,32 (Fig. 4e), rather than indicative of the initial India-Asia collision6.

The timing of rapid eruption of thick rhyolitic ignimbrite (ca. 52.5 Ma) in the Linzizong volcanic rocks and intense magmatism (ca. 51 Ma) in the Gangdese Batholith matches the sudden drop of the convergence rate of the Indian plate at ca. 51 Ma33,34,35. This synchronicity of events suggests that the slowdown of the Indian plate is largely the consequence of slab breakoff (Fig. 4e). This is because slab breakoff will result in the loss of the slab pull force14,29, which exerts a dominant influence on the velocity of the surface plate and cause a drastic change in plate motion10,11,36,37. Subsequent intracontinental convergence (Fig. 4f) of the Indian continental lithosphere beneath the Asian lithosphere after slab breakoff is likely driven by the subduction of dense Indian continental lithosphere38 and slab-pull of oceanic lithosphere on the Indo-Australian plate along the Indonesian segment of the plate margin39. Traditionally, the slow-down of the Indian plate at ca. 51 Ma is attributed to the increased resistance to subduction interpreted as a result of the initial India-Asia collision33,34. However, we consider this interpretation questionable because (1) under such a collisional regime, no appropriate mechanisms (see Fig. 1b) are available for producing extensive magmatism in southern Tibet as presented in this study (Fig. 2c and S1) and (2) the surface motion of the plate is closely related to or substantially driven by mantle dynamics (i.e., slab pull10,11,36,37) and thus if such a driving force disappears, significant slow down would occur.

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss in detail the problems of each interpreted age (70–34 Ma) proposed for the initiation of the India-Asia collision (see ref. 9, for review). We emphasize that any estimates on the collisional timing must effectively explain all the first-order observations of the spatial, temporal (Fig. 2d), and compositional changes (Fig. 3) of magmatic activities summarized in this study. In particular, we must explain the specific geodynamical processes responsible for the southward migration of magmatism from 72–65 Ma to 64–48 Ma followed by the generation of dramatically enhanced magmatism precisely constrained at ca. 52 Ma in the Gangdese arc, including volumetrically significant ignimbrite in the Linzizong volcanic rocks (Fig. 2c) and widely developed mafic enclaves and dykes (Fig. S1) in the Gangdese Batholith. Such enhanced magmatism requires anomalously high-temperature material and heat supply from the mantle, which are unlikely to be explained by later slab breakoff (at ca. 50–40 Ma40, 45 Ma18, 48–44 Ma41, and 50 Ma42,43) that would predate intense magmatism29,30, or by ca. 50 Ma India-Asia or Tethyan Himalaya-Asia collision44 that would result in a compression regime without intense magmatism (Fig. 1b).

Eclogite-facies peak metamorphism in the western Himalaya was recently refined at ca. 47–43 Ma and consequently an age of ca. 51–47 Ma was proposed for the initial India-Asia collision8. However, this collision age is likely an underestimate because the exhumed ultrahigh-pressure rocks may not represent the materials from the leading edge of subducted Indian continental margin.

Slab breakoff is likely inevitable in all collision zones involving a passive continental margin14. It follows that subducted continental crust has reached its maximum depth when slab breakoff occurs. This means that slab breakoff provides a maximal age for continental collision. In the case of the India-Asia collision, if Neo-Tethyan slab breaks off at ca. 53 Ma, the initial India-Asia collision should commence at ca. 55 Ma. This is because the progressively enlarged subducting slab dip revealed by the southward migration of magmatism from 72–65 Ma to 64–48 Ma (Fig. 2d) and high India-Asia convergence velocity35 point to a time lag of ca. 1–2 Ma (Table S6) between initial collision and slab breakoff.

This timing of the initial India-Asia collision (ca. 55 Ma) obtained from our petrological approach is in good agreement with recent estimates on collision ages from the cessation of Xigaze forearc sedimentation (ca. 58–54 Ma45), the dramatic change of sedimentary environment and the development of an unconformity in the Xigaze forearc basin (>56 Ma46), the onset of India-Asia terrestrial faunal exchange (ca. 54 Ma47), the reappraisal of existing paleomagnetic data (52.4 ± 4.5 Ma9), and the new paleomagnetic data (ca. 54.3 Ma48). This collision may account for the angular unconformity between the Dianzhong and Nianbo formations in Linzhou Basin (Fig. 2c) and coeval unconformity found in the Xigaze forearc basin46 due to the locking of the subduction zone on arrival of the Indian continent at the trench12. Therefore, it seems most probable that (1) the Dianzhong andesitic volcanism was generated during the transition from late subduction to initial collision (Fig. 4a,b), (2) the lower Nianbo terrestrial sedimentation represents the ongoing India-Asia collision prior to slab breakoff with a short duration from initial to ongoing collision due to the high India-Asia convergence velocity35, and (3) the late Nianbo and Pa’na bimodal volcanic rocks (Fig. 3a) are linked to mantle decompression melting and crustal anatexis due to the ascent of hot asthenosphere through slab window after slab breakoff30 (Fig. 4d,e). Nevertheless, we note that the exact timing of initial impingement of the Indian margin with the subduction zone will depend on the degree of distention of the Asian margin and may vary along the strike of the convergence zone due to irregularities in shape of the margin.

Our work shows that the petrological approach that we employ here can effectively distinguish processes at varying stages of continental collision. This approach may be applied to other continent-continent collision zones also involving a passive continental margin on the down-going plate, such as the Arabia-Eurasia collision zone — where the preserved magmatic record straddles the proposed Arabia-Eurasia collision age49,50.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhu, D.-C. et al. Magmatic record of India-Asia collision. Sci. Rep. 5, 14289; doi: 10.1038/srep14289 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially co-supported by Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB03010301) and other Chinese funding agencies (Project 973: 2011CB403102 and 2015CB452604; NSFC projects: 41225006, 41273044, and 41472061). We thank Xiu-Mian Hu for discussions and comments on the early version of the manuscript. We also thank Xian-Hua Li and Qiu-Li Li, and Zhao-Chu Hu for helping with the SIMS and LA-ICPMS U-Pb zircon dating analyses, respectively.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions D.C.Z., Q.W. and Z.D.Z. were involved in designing the study, collecting and analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. S.L.C., P.A.C., Y.L.N., S.A.L., F.Y.W. and X.X.M. contributed to discussions, interpretation of results, and manuscript writing and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

12/18/2015

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

References

- Yin A. & Harrison T. M. Geologic evolution of the Himalayan Tibetan Orogen. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 28, 211–280 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Aitchison J. C., Ali J. R. & Davis A. M. When and where did India and Asia collide? J. Geophys. Res. 112, B05423 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Garzanti E., Baud A. & Mascle G. Sedimentary record of the northward flight of India and its collision with Eurasia (Ladakh Himalaya, India). Geodinamica Acta 1, 297–312 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Mo X. X. et al. Mantle contributions to crustal thickening in south Tibet in response to the India–Asia collision. Lithos 96, 225–242 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Najman Y. et al. Timing of India-Asia collision: Geological, biostratigraphic, and palaeomagnetic constraints. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B12416, doi: 10.1029/2010JB007673 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bouilhol P., Jagoutz O., Hanchar J. M. & Dudas F. O. Dating the India–Eurasia collision through arc magmatic records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 366, 163–175 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- DeCelles P. G., Kapp P., Gehrels G. E. & Ding L. Paleocene-Eocene foreland basin evolution in the Himalaya of southern Tibet and Nepal: Implications for the age of initial India-Asia collision. Tectonics 33, doi: 10.1002/2014TC003522 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson D. G. et al. Petrochronology of Himalayan ultrahigh-pressure eclogite. Geology 41, 835–838 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lippert P. C., van Hinsbergen D. J. J. & Dupont-Nivet G. Early Cretaceous to present latitude of the central proto-Tibetan Plateau: A paleomagnetic synthesis with implications for Cenozoic tectonics, paleogeography, and climate of Asia. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 507, 1–21 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth D. & Uyeda S. On the relative importance of the driving forces of plate motions. Geophys. J. Int. 43, 163–200 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- Conrad C. P. & Lithgow-Bertelloni C. How mantle slabs drive plate tectonics. Science 298, 207–209 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magni V. et al. Numerical models of slab migration in continental collision zones. Solid Earth 3, 293–306 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Harris N. B. W., Pearce J. A. & Tindle A. G. Geochemical characteristics of collision-zone magmatism. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Pub. 19, 67–81 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. H. & von Blanckenburg F. Slab breakoff: A model of lithosphere detachment and its test in the magmatism and deformation of collisional orogens. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 129, 85–102 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- von Blanckenburg F. & Davies J. H. Slab breakoff: A model for syncollisional magmatism and tectonics in the Alps. Tectonics 14, 120–131 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari L. Slab detachment control on mafic volcanic pulse and mantle heterogeneity in central Mexico. Geology 32, 77–80 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- van der Voo R., Spakman W. & Bijwaard H. Tethyan subducted slabs under India. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 171, 7–20 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Kohn M. & Parkinson C. D. Petrologic case for Eocene slab breakoff during the Indo-Asian collision. Geology 30, 591–594 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Leech M. L., Singh S., Jain A. K., Klemperer S. L. & Manichavasgam R. M. The onset of India-Asia continental collision: Early, steep subduction required by the timing of UHP metamorphism in the western Himalaya. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 234, 83–97 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Lei J. S. & Zhao D. P. Teleseismic evidence for a break-off subducting slab under Eastern Turkey. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 14–28 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. L. et al. Tibetan tectonic evolution inferred from spatial and temporal variations in post-collisional magmatism. Earth-Sci. Rev. 68, 173–196 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D. C. et al. The origin and pre-Cenozoic evolution of the Tibetan Plateau. Gondwana Res. 23, 1429–1454 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li X. H. et al. Precise determination of Phanerozoic zircon Pb/Pb age by multicollector SIMS without external standardization. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, Q04010, doi: 10.1029/2009GC002400 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. T. et al. Inclination shallowing in Eocene Linzizong sedimentary rocks from Southern Tibet: correction, possible causes and implications for reconstructing the India–Asia collision. Geophys. J. Int. 194, 1390–1411 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- He S. D. et al. Cretaceous–Tertiary geology of the Gangdese Arc in the Linzhou area, southern Tibet. Tectonophysics 433, 15–37 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Watson E. B. & Harrison T. M. Zircon saturation revisited: temperature and composition effects in a variety of crustal magma types. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 64, 295–304 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Mo X. X. et al. Timing of magma mixing in the Gangdise magmatic belt during the India-Asia collision: Zircon SHRIMP U-Pb dating. Acta Geologica Sinica 79, 66–76 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Kapp P. et al. The Gangdese retroarc thrust belt revealed. GSA Today 17, 4–9 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Duretz T., Schmalholz S. M. & Gerya T. V. Dynamics of slab detachment. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13, Q03020 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- van de Zedde D. M. A. & Wortel M. J. R. Shallow slab detachment as a transient source of heat at midlithospheric depth. Tectonics 20, 868–882 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Ji W. Q., Wu F. Y., Chung S. L., Li J. X. & Liu C. Z. Zircon U-Pb chronology and Hf isotopic constraints on the petrogenesis of Gangdese batholiths, southern Tibet. Chem. Geol. 262, 229–245 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Chu M. F. et al. India’s hidden inputs to Tibetan orogeny revealed by Hf isotopes of Transhimalayan zircons and host rocks. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 479–486 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Patriat P. & Achache J. Indian-Eurasia collision chronology has implications for crustal shortening and driving mechanism of plates. Nature 311, 615–621 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Besse J. et al. Palaeomagnetic estimates of crustal shortening in the Himalayan thrust and Zangbo suture. Nature 311, 621–626 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- van Hinsbergen D. J. J., Steinberger B., Doubrovine P. & Gassmöller R. Acceleration-deceleration cycles of India-Asia convergence: Roles of mantle plumes and continental collision. J. Geophys. Res. 116, B06101 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y. L., O’Hara M. J., Pearce J. A. Initiation of subduction zones as a consequence of lateral compositional buoyancy contrast within the lithosphere: a petrologic perspective. J. Petrology 44, 851–866 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Austermann J. et al. Quantifying the forces needed for the rapid change of Pacific plate motion at 6 Ma. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 289–297 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Capitanio F. A., Morra G., Goes S., Weinberg R. F., Moresi L. India-Asia convergence driven by the subduction of the Greater Indian continent. Nature Geosci. 3, 136–139 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Li C., van der Hilst R. D., Meltzer A. S. & Engdahl E. R. Subduction of the Indian lithosphere beneath the Tibetan Plateau and Burma. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 274, 157–168 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. H. & von Blanckenburg F. Thermal controls on slab breakoff and the rise of high-pressure rocks during continental collisions. in When continents collide: Geodynamics and geochemistry of ultrahigh-pressure rocks. (eds Hacker B. R. & Liou J. G.) Ch. 4, 97–115 (The Netherlands, 1998).

- Negredo A. M., Replumaz A., Villaseñor A. & Guillot S. Modeling the evolution of continental subduction processes in the Pamir-Hindu Kush region. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 259, 212–225 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y., Chung S. L., Lo C. H., Ji J., Lee T. Y., Qian Q. & Zhang Q. Eocene Neotethyan slab breakoff in southern Tibet inferred from the Linzizong volcanic record. Tectonophysics 477, 20–35 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. Y. et al. Geochemical and Sr-Nd isotopic constraints on the genesis of the Cenozoic Linzizong volcanic successions, southern Tibet. J. Asian Earth Sci. 53, 96–114 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- van Hinsbergen D. J. J. et al. Greater India Basin hypothesis and a two-stage Cenozoic collision between India and Asia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7659–7664 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme D. A., Carrapa B. & Kapp P. Sedimentology, provenance and geochronology of the Upper Cretaceous-Lower Eocene western Xigaze forearc, southern Tibet. Basin Res. 10.1111/bre.12080 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. M. et al. New insights into the timing of the India–Asia collision from the Paleogene Quxia and Jialazi formations of the Xigaze forearc basin, South Tibet. Gondwana Res. 10.1016/j.gr.2015.02.007 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clementz M. S. et al. Early Eocene warming events and the timing of terrestrial faunal exchange between India and Asia. Geology 39, 15–18 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. M. et al. Paleomagnetism and U-Pb zircon geochronology of Lower Cretaceous lava flows from the western Lhasa terrane: New constraints on the India-Asia collision process and intracontinental deformation within Asia. J. of Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth. doi: 10.1002/2014JB011362 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Keskin M. Magma generation by slab steepening and breakoff beneath a subduction-accretion complex: An alternative model for collision-related volcanism in Eastern Anatolia, Turkey. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 7–10 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H. Y. et al. Zircon U-Pb age constraints from Iran on the magmatic evolution related to Neotethyan subduction and Zagros orogeny. Lithos 162–163, 70–87 (2013). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.