Abstract

Objective

To determine population-based estimates of medical costs attributable to venous thromboembolism (VTE) among patients currently or recently hospitalized for acute medical illness.

Study Design

Population-based cohort study conducted in Olmsted County, Minn.

Methods

Using Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) resources, we identified all Olmsted County, MN residents with objectively-diagnosed incident VTE within 92 days of hospitalization for acute medical illness over the 18-year period, 1988–2005 (n=286). One Olmsted County resident hospitalized for medical illness without VTE was matched to each case on event date (± 1 year), duration of prior medical history and active cancer status. Subjects were followed forward in REP provider-linked billing data for standardized, inflation-adjusted direct medical costs (excluding outpatient pharmaceutical costs) from 1 year before their respective event or index date to the earliest of death, emigration from Olmsted County, or 12/31/2011 (study end date). We censored follow-up such that each case and match control had similar periods of observation. We also controlled for length of follow-up from index to up to 5-years post-index. We used generalized linear modeling (controlling for age, sex, pre-existing conditions and costs 1 year before index) to predict costs for cases and controls.

Results

Adjusted mean predicted costs were 2.5-fold higher for cases ($62,838) than for controls ($24,464) (P=<0.001) from index to up to 5-years post-index. Cost differences between cases and controls were greatest within the first 3 months after the event date (mean difference=$16,897) but costs remained significantly higher for cases compared to controls for up to 3 years.

Conclusions

VTE during or after recent hospitalization for medical illness contributes a substantial economic burden.

Keywords: Costs, Cost analysis, Medical Care Utilization, Deep vein thrombosis, Pulmonary embolism, Venous thromboembolism, Cost of Illness

INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), consisting of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and it’s complication, pulmonary embolism (PE), causes substantial morbidity, disability, and mortality.1 Complete and valid estimates of VTE-associated medical care utilization and costs are essential for informing allocation of scarce resources, targeting efforts toward prevention, identifying best practices, addressing future care needs, and implementing cost-effective treatments.2 However, existing estimates of VTE-associated costs2–5 are problematic. Previous studies typically failed to control for age, sex, comorbid conditions and other events that place patients at risk for VTE, particularly hospitalization for major surgery or acute medical illness, trauma or major fracture, and cancer.1 Together, these latter risk exposures account for over 75% of all incident VTE in the population.6 Although VTE is increasingly diagnosed and managed solely in office-based settings,7 the majority of population-based cost estimates were limited to patients admitted to emergency department (ED) and/or hospital; patients diagnosed and managed solely within office-based or chronic care (e.g., nursing home) settings were excluded. Moreover, case ascertainment almost always relied on discharge diagnosis codes obtained from billing data or death certificates.4,5 The limitations of discharge diagnosis codes for identifying incident VTE are well recognized.8–11

In those very few cost studies which validated VTE using medical record review, cost estimates were often obtained using self-reported utilization and applying national average estimates of hospital costs per day, ignoring differences in daily costs between persons with and without VTE. Many estimates of VTE-associated medical costs are also limited to costs accrued during the initial encounter.12,13 To address these limitations, we performed a population-based matched-cohort study to estimate excess medical costs attributable to VTE that occurred during or recently after hospitalization for acute medical illness, independent of potential confounding due to VTE risk factors. We took advantage of Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) resources, including a previously identified population-based inception cohort consisting of all Olmsted County, MN residents with objectively diagnosed incident VTE as well as previously identified matched non-VTE controls drawn from the same population.14 REP resources also afforded provider-linked objective medical cost estimates based on line item detail for every service and procedure over extended periods of time.15 Combining objectively-diagnosed VTE cases and controls with objective cost data for each individual afforded the opportunity to estimate medical care costs attributable to VTE, 1) across the full spectrum from symptomatic through fatal events, 2) from before the event until death or emigration from the area, 3) adjusting for age, sex and calendar year, and 4) adjusting for prevalent co-morbid conditions. Thus, we were able to estimate the excess cost of medical care that is attributable to VTE independent of potential confounding due to VTE risk factors.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

Olmsted County, MN (2010 census population=144,248), provides a unique opportunity for investigating the natural history of VTE.6,16,17 Rochester, the county seat, is approximately 80 miles from the nearest major metropolitan area. Mayo Clinic, together with Olmsted Medical Center (OMC), a second group practice and their affiliated hospitals, provide over 95% of all medical care delivered to local residents.18 Since 1907, every Mayo patient has been assigned a unique identifier; all information from every provider contact is contained within a unit record for each patient. Diagnoses assigned at each visit are coded and entered into continuously updated files. Under auspices of the REP, the unique identifiers, diagnostic index, and medical records linkage were expanded to include the few other providers of medical care to local residents, including OMC and the few private practitioners in the area, thereby linking the medical records for community residents at the individual level.14,19 Using REP resources, we performed a cohort study. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and OMC Institutional Review Boards.

Study Population

All Olmsted County, MN residents with incident DVT or PE over the 40-year period, 1966–2005, were identified as previously described.6 REP records of individuals who refused authorization for use of medical records in reseach were excluded from review.18,20 The medical records for remaining individuals were reviewed from date first seen until date last seen at any REP provider to identify, confirm, and characterize each VTE event. Incident events were limited to persons residing in Olmsted County for whom this was a first life-time symptomatic VTE. Record review was performed by trained, experienced nurse abstractors. The review included all outpatient general history notes, ED notes and hospitalization records, nursing notes, radiological, ultrasound and nuclear medicine imaging reports, surgical records, vascular laboratory reports, echocardiography reports, autopsy reports and death certificates.

Study nurses recorded method of VTE diagnosis, VTE event type (DVT, PE, or both; chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), date of VTE (i.e., “index date” for cases), location at onset of VTE symptoms and/or signs (hospital, nursing home, community), sex; age and active cancer and cancer type as of index date. The present study was limited to “objectively-diagnosed” events, as previously described,1,6,9,17 and included all incident VTE cases with recent hospitalization for medical illness (i.e., within 92 days [365 days / 4 or ~3 months] before index); residents admitted to hospital solely for VTE treatment were not included. The hospitalization closest to but before VTE or the hospitalization during which VTE occurred was selected as the “index hospitalization”. Cases with a surgical hospitalization within 92 days before index were excluded.

REP also provides enumeration of the entire Olmsted County population from which potential controls can be sampled.14 Using this system, we identified all Olmsted County residents with hospitalization for acute medical illness within ±1 year of each case’s VTE date, similar length of medical record and no prior VTE.16 For patients with multiple hospitalizations per year, one hospitalization was randomly chosen to comprise the sampling frame. From this, a random sample of potential controls was identified, of which two were matched on case VTE event year and active cancer status. One control was randomly chosen for the current study. The hospitalization identified in the sampling frame was selected as the control’s “index hospitalization”. Assignment of control’s index date depended on whether the matched case’s VTE event occurred during or after the case’s index hospitalization (Figure 1). For cases whose VTE occurred during the index hospitalization, the control’s index date was randomly assigned to be a day within the control’s index hospitalization admission and discharge dates. For cases whose VTE occurred within 92 days after discharge from the index hospitalization, the control’s index date was randomly assigned to be a day within 92 days after the control’s index hospitalization discharge date. Medical records of potential controls were reviewed to confirm Olmsted County residency as of index, absence of surgical hospitalizations within 92 days before index, and that they matched the case with respect to active cancer as of index.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram on the identification and selection of a matched non-VTE control for each VTE case.

Collection of Medical Costs

Through an electronic data-sharing agreement between Mayo Clinic and OMC, patient-level administrative data on healthcare utilization and associated billed charges incurred at these institutions are shared and archived within the Olmsted County Healthcare Expenditure and Utilization Database (OCHEUD) for use in approved research studies. Data are electronically linked, affording complete information on all hospital and ambulatory care delivered by these providers to area residents from 1/1/1987 through 12/31/2011. OCHEUD includes information on all Olmsted County residents (i.e., both sexes, all ages, and all payer types, including the uninsured) and contains line-item detail on date, type, frequency, and billed charge for every good or service provided. Recognizing discrepancies between billed charges and true resource use, OCHEUD employs widely accepted valuation techniques to generate a standardized inflation-adjusted estimate of the costs of each service or procedure in constant dollars. Cost estimates in this study were adjusted to 2011 dollars.21 Because cost data are only available electronically since 1987 and we wished to obtain costs in the year before index, the present study was limited to all Olmsted County residents with a first lifetime objectively-diagnosed DVT or PE, 1988–2005.1,6 Each case and control was followed forward in time for costs from 1 year before their respective index date to earliest of death, emigration from Olmsted County, or 12/31/2011 (study end date). We ensured similar periods of observation for each case and matched control by censoring both members of each pair as of the shortest length of follow-up for either member.

Pre-index Comorbid Conditions

To compare baseline characteristics and comorbidities between cases and controls, we obtained all International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses codes assigned to each individual in OCHEUD 1 year before index and categorized every diagnosis code assigned each individual into the 17 ICD-9-CM chapters and 114 subchapters. A summary measure of medical conditions in the year before index was obtained using Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) System® software.22 ACG software categorizes individual’s diagnosis codes into groupings based on persistence, severity, and etiology of the condition, as well as diagnostic certainty, and need for specialty care.22 ACG software was also used to assign a Resource Utilization Band (RUB) value to each individual. RUB categories are aggregations of ACGs that have similar expected resource use, with values ranging from 0 (no relevant diagnosis codes) to 5 (diagnosis codes associated with very high use).23

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.02 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical testing used the two-tailed alpha level of 0.05. The principal outcome was direct medical costs attributable to VTE. As done previously for several medical conditions,13,15,21,24 we analyzed costs from 1 year before index to index (providing an internal control) to a maximum of 5 years post index. Post-index analyses were also subdivided into: index-3 months, 3–6 months, 6-months-1 year, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, 3–4 years, and 4–5 years. In initial analyses, the unadjusted costs for each control were subtracted from costs for his/her case in each time period; statistical significance was assessed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test to account for the highly skewed nature of cost data and paired observations.15,21,24–26 For purposes of illustration we observed this difference for time periods of interest. We then used general linear multivariate modelling to examine the extent to which age, sex, RUB measure of pre-index comorbidity, and pre-index costs accounted for post-index cost differences between cases and controls. This adjusted approach employed two-part models to account for zero costs27,28 when appropriate, and incorporated a generalized linear model with family distribution based on the modified Park test recommended by Manning and Mullahy.29 This analytic approach accounts for the skewed cost distribution while enabling coefficients to be directly back transformed into the original dollar scale.30,31 We analyzed differences in costs between cases and controls using the method of recycled predictions, setting all individuals as cases with VTE or as controls without VTE, while all other individual characteristics remain as observed.32,33 Mean values and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of the mean difference were calculated.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

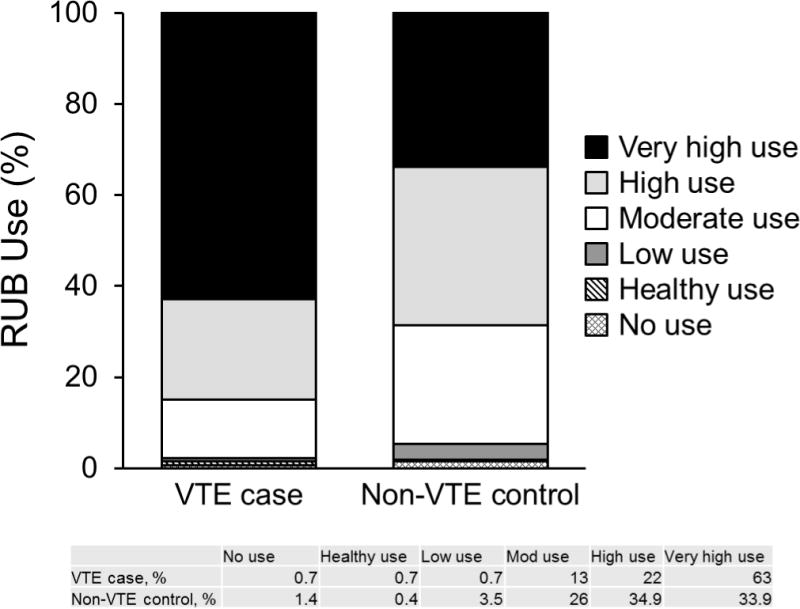

We identified 286 VTE cases and matched controls who were hospitalized for medical illness within 92 days before index [percent male=45% for cases and 41% for controls (p=0.27); mean age (±SD)=65.0±18.9 years for cases and 58.7±21.4 years for controls (p<0.001), with 104 VTE cases (36%) and 80 controls (28%) age >75 years. The length of follow-up post-index ranged from 1 day to 15 years. Of all VTE events, 130 (45%) occurred during index hospitalization and 156 (55%) occurred within 92 days after discharge. VTE event type distribution was DVT alone (n=182; 64%), PE alone (n=69; 24%), PE with DVT (n=33; 12%) and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (n=2; 0.7%). In the year before index, differences between cases and controls were observed in 13 of 17 ICD-9-CM chapters (Supplementary Table). Within the 13 chapters, there were several significant differences at the subchapter level. Figure 2 provides the RUB summary measure of comorbidity for cases and controls. Two-thirds (n=181; 63%) of cases had a RUB value indicative of very high use compared to one-third (n=98; 34%) of controls. On the opposite side of the spectrum, no use, healthy use, and low use was 0.7%, 0.7%, 0.7% and 1.4%, 0.4%, 3.5% for VTE cases and non-VTE controls, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of RUB values in the 1-year before index for VTE cases and non-VTE control.

Observed cost comparisons

Table 1 provides unadjusted direct mean, median (interquartile range [IQR]), minimum and maximum medical costs for case/control pairs and mean cost differences between case/control pairs 1 year before index, all 5 years post-index, and selected periods within the 5-years post-index. In the year before index, both mean and median costs for cases were nearly two-fold higher compared to controls, in part reflecting the broad costs range for cases compared to that for controls. The unadjusted mean difference in pre-index annual costs between cases and controls was $17,026 (95% CI: $11,942–$22,335). Overall 5-years post-index and within each post-index period, mean unadjusted cost differerences were significantly higher for cases in each post-index period.

TABLE 1.

Unadjusted Direct Medical Costs for Venous Thromboembolism Case/Control Pairs by Time Period

| Time Period | Case/Control Pairs (n) |

Case ($) |

Control ($) |

Mean Difference ($) |

Wilcoxon Signed Rank P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year before Index | 286 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 35,039 (39,725) | 18,013 (21,798) | 17,026 (43,286) | <0.001 | |

| median | 20,487 | 10,495 | 9,080 | ||

| P25a | 11,386 | 4,861 | −1,951 | ||

| P75a | 43,866 | 21,728 | 33,162 | ||

| Index to 5 years | 286 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 66,250 (97,067) | 19,693 (40,311) | 46,556 (104,269) | <0.001 | |

| median | 33,993 | 7,270 | 21,553 | ||

| P25 | 16,112 | 2,121 | 5,424 | ||

| P75 | 70,564 | 22,520 | 55,894 | ||

| Index to 3 months | 286 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 23,831 (27,131) | 4,731 (9,209) | 19,100 (27,339) | <0.001 | |

| median | 14,040 | 1,835 | 11,371 | ||

| P25 | 7,074 | 158 | 4,635 | ||

| P75 | 30,340 | 5,335 | 25,968 | ||

| 3 to 6 months | 207 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 5,704 (10,422) | 1,961 (6,984) | 3,743 (12.626) | <0.001 | |

| median | 1,126 | 157 | 624 | ||

| P25 | 324 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P75 | 5,433 | 828 | 4,972 | ||

| 6 months to 1 year | 188 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 11,601 (20,552) | 3,524 (8,856) | 8,077 (22,044) | <0.001 | |

| median | 2,546 | 599 | 1,395 | ||

| P25 | 584 | 116 | −188 | ||

| P75 | 14,849 | 2,698 | 13,033 | ||

| 1 year to 2 years | 167 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 17,110 (41,271) | 6,997 (27,876) | 10,113 (51,070) | <0.001 | |

| median | 3,725 | 1,351 | 1,824 | ||

| P25 | 1,141 | 349 | −1,007 | ||

| P75 | 14,158 | 5,008 | 10,521 | ||

| 2 years to 3 years | 147 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 15,023 (33,341) | 4,945 (10,147) | 10,078 (35,363) | <0.001 | |

| median | 3,442 | 1,142 | 1,312 | ||

| P25 | 1,010 | 302 | -817 | ||

| P75 | 9,716 | 4,440 | 7,212 | ||

| 3 years to 4 years | 130 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 13,900 (32,258) | 5,865 (13,688) | 8,035 (35,773) | P=0.001 | |

| median | 2,556 | 1,072 | 662 | ||

| P25 | 909 | 219 | −1,237 | ||

| P75 | 12,288 | 4,816 | 10,793 | ||

| 4 years to 5 years | 113 | ||||

| mean (SD) | 16,790 (43,250) | 4,892 (10,139) | 11,898 (45,144) | P=0.001 | |

| median | 2,665 | 1,067 | 570 | ||

| P25 | 545 | 232 | −1,123 | ||

| P75 | 13,015 | 3,876 | 9,327 |

25th and 75th interquartile range (IQR)

Adjusted cost comparisons

Table 2 provides adjusted mean predicted direct medical costs and mean predicted cost differences for cases and controls for the overall time period from 1988–2005 (index-5-years). After adjusting for group differences in age at index, sex, costs incurred 1 year prior to index and RUB values, the mean predicted costs for cases ($62,838) were significantly higher than those for controls ($24,464), with a mean predicted difference of $38,374 (Bootstrapped 95% CI: $26,975–49,435). The adjusted predicted mean difference in costs were significantly higher for VTE cases than controls for time periods index-3 months, 3–6 months, 6 months-1 year, and 2–3 years post index. Adjusted predicted costs were higher for cases but not significantly different from controls for periods 1–2, 3–4 and 4–5-years post-index, possibly due to the high estimated variability in predicted costs.

TABLE 2.

Adjusteda Mean Direct Medical Costs for Venous Thromboembolism Case/Control Pairs by Time Period

| Time Period | Cases ($) | Controls ($) | Mean Difference (Bootstrapped 95% CI; $) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index to 5 years | 62,838 | 24,464 | 38,374 (26,975; 49,435) |

| Index to 3 months | 22,646 | 5,749 | 16,897 (13,761; 19,973) |

| 3 to 6 months | 4,626 | 2,610 | 2,016 (210; 3,597) |

| 6 months to 1 year | 10,125 | 5,058 | 5,068 (1,717; 8,167) |

| 1 to 2 years | 13,804 | 9,761 | 4,043 (−7,210; 12,686) |

| 2 to 3 years | 13,211 | 6,921 | 6,290 (1,373; 11,797) |

| 3 to 4 years | 11,273 | 9,661 | 1,611 (−5,510; 7,290) |

| 4 to 5 years | 20,617 | 12,674 | 7,943 −5,373; 21,806) |

Predicted cost adjusted for age, sex, costs in the year prior to index and Resource Utilization Band.

DISCUSSION

There is a shortage of reliable data regarding the extent to which hospital-associated VTE contributes to excess medical costs and for how long any excess costs occur. The present population-based study followed individuals who were hospitalized for acute medical illness to compare total direct medical costs between patients who did and did not experience an objectively-confirmed VTE during or 92 days after hospitalization, the time period of highest VTE risk. The adjusted predicted mean direct medical costs were significantly higher for cases than for controls from index to 5-years post-index. The adjusted predicted mean cost for VTE cases was $62,838 versus $24,464 for non-VTE controls (mean difference=$38,374). Although comparisons of across-study findings should be interpreted with caution, the VTE-attributable costs appear to exceed medical care costs attributable to osteoporotic hip fracture34, Parkinson’s Disease24, complications of percutaneous coronary intervention35 and traumatic brain injury.21

VTE-attributable costs were highest within 3-months following VTE; the adjusted predicted mean difference in direct medical costs between persons who did and did not experience VTE was $16,897. This is possibly related to early costs for VTE diagnosis and acute management. Importantly, however, costs remained about two-fold higher for VTE cases compared to controls from 3-months to 3-years after index. This difference reached significance for all periods up to 3-years except for 1–2-years post-index. During the 1–2 year period, 1 control and 2 cases incurred total costs >$200,000, substantally more than any other case or control during that period. The control was hospitalized for 3 months with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilatory support in intensive care. One case underwent 24 surgeries (most orthopedic) in that period; the other case underwent heart transplantation. If these outliers are excluded, the adjusted predicted mean difference in direct medical costs ($3,215) was still higher in cases compared to controls, but the difference was not significant (95% CI: -$890; $8,545). Nevertheless, we suspect that costs are significantly higher for cases than controls for at least 3 (and possibly 5) years after index. This prolonged cost difference could reflect incremental costs for management of VTE complications (i.e., post thrombotic syndrome, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension) and VTE recurrence. Over the 5-year post-index time period, 51 (18%) VTE cases had recurrent VTE with a median time to recurrence of 180 days (IQR: 2 days-5 years). From index to 5 years post-index, the adjusted predicted mean cost for the 51 VTE cases with recurrent VTE cases was $106,005 versus $21,950 for non-VTE controls (mean difference=$84,055; 95% CI: $55,993; $127,457). The adjusted predicted mean cost of the 235 VTE cases without recurrent VTE was $54,426 compared to $24,653 for the control (mean difference=$29,773; 95% CI: $18,705; $42,827).

Two previous studies reported mean ± SD (median) costs of $8,331 ± $18,667 ($4,003) for persons with a VTE36 and average hospital costs of $8,794 associated with treating PE, respectively.4 However, these studies did not include a control group such that costs attributable to VTE could not be estimated. In the only previous study that included a control group, reimbursed hospitalization costs were $10,804 and $16,644 for primary diagnoses of DVT and PE2, respectively, estimates that are comparable to our index-3 months ($16,897) costs. However, all previous studies likely underestimated the direct medical cost attributable to VTE by over 50% due to failure to identify long-term costs of VTE.

Our study has a number of limitations. The estimates are for a single geographic population which in 2010 was 90% white. The age- sex- and racial-distribution of Olmsted County is similar to that for Minnesota, the upper mid-west, and the U.S. white population; however, residents of Olmsted County exhibit higher median income and education level compared to these geographic regions.14,18 While no single geographic area is representative of all others, the under-representation of minorities may compromise the generalizability of our findings to different racial and ethnic groups. Costs associated with pharmacologic treatments were not included in this analysis due to lack of electronically available data on outpatient pharmacological costs throughout the total time period. However, the incremental costs of VTE pharmacologic treatment likely would increase the cost difference between cases and controls. Certain sequelae of VTE, such as pulmonary hypertension and post-phlebitic syndrome, were not identified following incident VTE during most of this time period so costs specific to these conditions could not be collected. Finally, cost estimates were limited to direct medical care costs and did not include indirect or nursing home costs.

In conclusion, VTE associated with a recent hospitalization for medical illness contributes a substantial economic burden to society across all hospital and ambulatory care delivered. This finding will help to inform models that assess the cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions to reduce VTE occurrence and guide reimbursement policy.

Supplementary Material

Take-away points.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) during or shortly after hospitalization for acute medical illness contributes a substantial economic burden; VTE-attributable costs are highest in the initial 3 months but persist even 3 years beyond the VTE event date. This finding will help to inform models that assess the cost-effectiveness of alternative interventions to reduce VTE occurrence and guide reimbursement policy.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Catherine L. Brandel, R.N., Diadra H. Else, R.N., Jane A. Emerson, R.N., and Cynthia L. Nosek, R.N. for excellent data collection and Cynthia E. Regnier, R.N., as research project manager.

Funding Sources: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute under Award Numbers R01HL66216 and K12HL83141 (a training grant in Vascular Medicine [KPC]) to JAH, and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Award Number R01AG034676 of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health). Research support also was provided by Mayo Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Kevin P. Cohoon, D.O., M.Sc. declares no conflict of interest.

Cynthia L. Leibson, Ph.D. declares no conflict of interest.

Jeanine E. Ransom, B.A. declares no conflict of interest.

Aneel A. Ashrani, M.D., M.S. declares no conflict of interest.

Tanya M. Petterson, M.S. declares no conflict of interest.

Kirsten Hall Long, Ph.D. declares no conflict of interest.

Kent R. Bailey, Ph.D. declares no conflict of interest.

John A. Heit, M.D. has served on Advisory Boards for Daiichi Sankyo and Janssen Pharmaceuticals for which he received honoraria.

References

- 1.Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:370–372. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spyropoulos AC, Lin J. Direct medical costs of venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospital readmission rates: an administrative claims analysis from 30 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13:475–486. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2007.13.6.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avorn J, Winkelmayer WC. Comparing the costs, risks, and benefits of competing strategies for the primary prevention of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2004;110:IV25–32. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000150642.10916.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fanikos J, Rao A, Seger AC, Carter D, Piazza G, Goldhaber SZ. Hospital costs of acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2013;126:127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White RH, Garcia M, Sadeghi B, et al. Evaluation of the predictive value of ICD-9-CM coded administrative data for venous thromboembolism in the United States. Thromb Res. 2010;126:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heit JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, et al. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1245–1248. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aujesky D, Roy PM, Verschuren F, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: an international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60824-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennessy DA, Quan H, Faris PD, Beck CA. Do coder characteristics influence validity of ICD-10 hospital discharge data? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leibson CL, Needleman J, Buerhaus P, et al. Identifying in-hospital venous thromboembolism (VTE): a comparison of claims-based approaches with the Rochester Epidemiology Project VTE cohort. Med Care. 2008;46:127–132. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181589b92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White RH, Brickner LA, Scannell KA. ICD-9-CM codes poorly indentified venous thromboembolism during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:985–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan C, Battles J, Chiang YP, Hunt D. The validity of ICD-9-CM codes in identifying postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33:326–331. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ollendorf DA, Vera-Llonch M, Oster G. Cost of venous thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery in hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59:1750–1754. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/59.18.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oster G, Ollendorf DA, Vera-Llonch M, Hagiwara M, Berger A, Edelsberg J. Economic consequences of venous thromboembolism following major orthopedic surgery. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:377–382. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O’Brien PC. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA. 2001;285:60–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585–593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melton LJ., 3rd The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leibson CL, Brown AW, Hall Long K, et al. Medical care costs associated with traumatic brain injury over the full spectrum of disease: a controlled population-based study. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2038–2049. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) Systems Software. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) Systems Software. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leibson CL, Long KH, Maraganore DM, et al. Direct medical costs associated with Parkinson’s disease: a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1864–1871. doi: 10.1002/mds.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibson CL, Hu T, Brown RD, Hass SL, O’Fallon WM, Whisnant JP. Utilization of acute care services in the year before and after first stroke: A population-based study. Neurology. 1996;46:861–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long KH, Rubio-Tapia A, Wagie AE, et al. The economics of coeliac disease: a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23:525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newhouse JP, Manning WG, Morris CN, et al. Some interim results from a controlled trial of cost sharing in health insurance. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1501–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112173052504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–494. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Birnbaum HG, Ben-Hamadi R, Greenberg PE, Hsieh M, Tang J, Reygrobellet C. Determinants of direct cost differences among US employees with major depressive disorders using antidepressants. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27:507–517. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullahy J. Much ado about two: reconsidering retransformation and the two-part model in health econometrics. J Health Econ. 1998;17:247–281. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu A, Arondekar BV, Rathouz PJ. Scale of interest versus scale of estimation: comparing alternative estimators for the incremental costs of a comorbidity. Health Econ. 2006;15:1091–1107. doi: 10.1002/hec.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esposito D, Bagchi AD, Verdier JM, Bencio DS, Kim MS. Medicaid beneficiaries with congestive heart failure: association of medication adherence with healthcare use and costs. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:437–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabriel SE, Tosteson AN, Leibson CL, et al. Direct medical costs attributable to osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:323–330. doi: 10.1007/s001980200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacobson KM, Hall Long K, McMurtry EK, Naessens JM, Rihal CS. The economic burden of complications during percutaneous coronary intervention. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:154–159. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bullano MF, Willey V, Hauch O, Wygant G, Spyropoulos AC, Hoffman L. Longitudinal evaluation of health plan cost per venous thromboembolism or bleed event in patients with a prior venous thromboembolism event during hospitalization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11:663–673. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.8.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.