Abstract

Background

Though the incidence of new Trypanosoma cruzi infections has decreased significantly in endemic regions in the Americas, medical professionals continue to encounter a high burden of resulting Chagas disease among infected adults. The current prevalence of Chagas heart disease in a community setting is not known; nor is it known how recent insecticide vector control measures may have impacted the progression of cardiac disease in an infected population.

Objectives and Methods

Nested within a community serosurvey in rural and periurban communities in central Bolivia, we performed a cross-sectional cardiac substudy to evaluate adults for historical, clinical, and electrocardiographic evidence of cardiac disease. All adults between the ages of 20 and 60 years old with T. cruzi infection and those with a clinical history, physical exam, or ECG consistent with cardiac abnormalities were also scheduled for echocardiography.

Results and conclusions

Of the 604 cardiac substudy participants with definitive serology results, 183 were seropositive for infection with T. cruzi (30.3%). Participants who were seropositive for T. cruzi infection were more likely to have conduction system defects (1.6% versus 0 for complete right bundle branch block and 10.4% versus 1.9% for any bundle branch block; p=0.008 and p<0.001, respectively). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of bradycardia among seropositive versus seronegative participants. Echocardiogram findings were not consistent with a high burden of Chagas cardiomyopathy: valvulopathies were the most common abnormality, and few participants were found to have low ejection fraction or left ventricular dilatation. No participants had significant heart failure. Though almost one third of adults in the community were seropositive for T. cruzi infection, few had evidence of Chagas heart disease.

Keywords: Chagas disease, Chagas heart disease, Trypanasoma cruzi, Community prevalence, Bolivia

Introduction

Chagas disease, caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in Central and South America [1-3]. Vector-borne transmission occurs when the feces from the infected triatomine insect is inoculated through the bite wound or intact mucosa of the mammalian host. Since 1991, affected countries in the Southern Cone have implemented insecticide campaigns with the goal of reducing the vector burden and interrupting transmission [4]. Nevertheless, an estimated 8-10 million people are currently living with Chagas disease [2, 5, 6].

Infection with T. cruzi often goes undetected. The acute phase lasts four to eight weeks and generally results in only non-specific signs and symptoms. Infection persists in the absence of effective treatment, and untreated patients enter the chronic phase of infection. Approximately 20-30% of those infected subsequently develop cardiac or, less commonly, digestive disease years or decades after infection. Common manifestations of Chagas cardiomyopathy include atrioventricular and bundle branch blocks, arrhythmias, and dilated cardiomyopathy eventually leading to congestive heart failure [1, 7, 8].

In central Bolivia, an area that remains endemic for T. cruzi, the primary livelihood is subsistence farming. Most farmers continue to live in adobe houses with mud floors, structures that easily accommodate triatomine bugs. In 2003, the Bolivian national control program instituted large-scale insecticide campaigns to reduce triatomine infestation. We conducted a serosurvey of all community residents older than two years to determine the community-wide prevalence of T. cruzi infection, and a nested study of cardiac disease in adults 20-60 years old.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of CEADES, Asociación Benéficia PRISMA, and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. All adult participants provided written informed consent, with separate forms for the serosurvey and the cardiac substudy. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian on behalf of children <18 years old, and children aged 7 to 17 years provided written assent.

Study setting and serosurvey participants

The study was conducted in Punata, a province of Cochabamba Department with a population of 47,735 inhabitants at the time of the 2001 census. Participants were recruited between January 2009 and May 2010. Communities were selected to include rural and peri-urban populations living in the catchment area of Punata Hospital, located in the central city (also called Punata). Field workers invited all residents 2 years or older to participate. All participating individuals provided a blood sample for serologic testing. Testing was also offered for children younger than 2 years whose mothers were found to have T. cruzi infection, based on the risk of congenital transmission.

Adult cardiac substudy

All permanent community residents in the age range 20-60 years who participated in the serosurvey were asked to participate in the nested cardiac substudy. Adults older than 60 were excluded based on prior evidence that rates of Chagas heart disease peaked in adults ages 30 to 50 years old [9-12]. They were also excluded to reduce the number of age-related non-specific cardiac findings on electrocardiogram and echocardiogram.

Laboratory Methods

Serum samples were evaluated for antibodies to T. cruzi using at least two of three commercially available assays: a rapid immunochromatographic (IC) screening test based on recombinant T. cruzi antigens (STAT-PAK, Chembio Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Medford, New York), an epimastigote lysate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Chagatek, bioMérieux, Buenos Aires, Argentina), and an indirect hemoagglutination assay (HAI) (IHA - Chagatest, Wiener Laboratorios, Rosario, Argentina). All tests were performed and interpreted following the manufacturers guidelines. Individuals were considered to have T. cruzi infection if they had two positive serologic tests. Twelve individuals participating in the nested cardiac substudy had inconclusive serologic results based on conflicting or indeterminate assay results; these individuals were excluded from analysis.

Cardiac study procedures

All substudy participants underwent a focused history and physical exam and an electrocardiogram (ECG), and gave one blood sample. All individuals who were positive for infection with T. cruzi and all those with any evidence of cardiac abnormalities by history, physical exam, or ECG (including bradycardia with a heart rate less than 60 beats per minute) were scheduled to undergo echocardiogram. Echocardiograms were performed using a portable Esaote Caris machine. A cardiologist read all electrocardiograms and performed and interpreted all echocardiograms. Electrocardiograms were coded and interpreted according to established criteria [13]. The cardiologist was blinded for all ECG interpretation; study participants occasionally revealed their T. cruzi infection status to the cardiologist during their echocardiogram rendering echocardiogram blinding incomplete.

Statistical Analysis

We evaluated associations between infection with T. cruzi and cardiac lesions using odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and two-tailed Fisher’s exact test with an alpha of 0.05, as well as multivariate logistic regression models. Logistic regression models included age and serostatus as predictor covariates. Because incomplete right bundle branch block has been shown to be a highly non-specific finding and can be a normal variant in healthy adults [14], all analyses evaluating combined conduction system defects excluded incomplete right bundle branch blocks. Data were collected and managed using Microsoft Access; statistical analysis was performed using Stata 11.0.

Results

Study Population

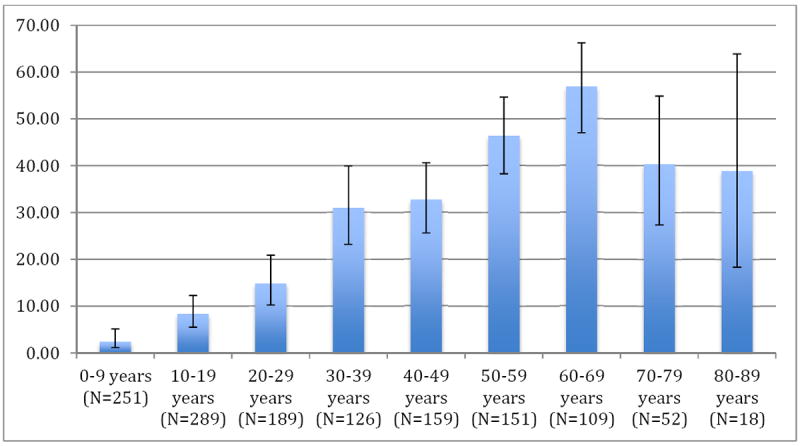

A total of 1,380 individuals participated in the T. cruzi serosurvey; 36 (2.6%) individuals were excluded due to inconclusive serology results, yielding a survey population of 1344 (Table 1). The mean age of all participants in the community serosurvey was 31.29 years (standard deviation 21.83). The mean age of the participants in the cardiac substudy was 39.19 years (standard deviation 12.16), and among those who received an echocardiogram was 39.89 years (standard deviation 12.26). Seroprevalence increased with increasing age in all decades until the seventh decade, with a maximum seroprevalence of 56.88% among study participants between the ages of 60 and 69 years. Rates were lower among study participants in their 70s and 80s but with confidence intervals that overlapped with those in younger age groups. Twenty-one of 52 participants between the ages of 70 and 79 years were positive for T. cruzi infection, yielding a seroprevalence of 40.38% (95% confidence interval 27.31-54.87). Of those participants between the ages of 80 and 89 years, seven of 18 were positive for T. cruzi infection, yielding a seroprevalence of 38.89% (95% confidence interval 18.26-63.86) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in community serosurvey with conclusive serologic data

| Characteristics | Community (N=1344)a | Cardiology substudy (N=604) | Completed Echocardiogram (N= 200) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Seropositive n (%) | N | Seropositive n (%) | N | Seropositive n (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <20 | 540 | 30 (5.6) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 20-29 | 189 | 28 (14.8) | 179 | 26 (14.5) | 53 | 10 (18.9) |

| 30-39 | 126 | 39 (31.0) | 118 | 39 (33.1) | 43 | 15 (34.9) |

| 40-49 | 159 | 52 (32.7) | 152 | 47 (30.9) | 47 | 22 (46.8) |

| 50-60 | 158 | 73 (46.2) | 155 | 71 (45.8) | 57 | 31 (54.4) |

| >60 | 172 | 87 (50.6) | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female | 818 | 187 (22.9) | 387 | 107 (27.6) | 112 | 46 (41.1) |

| Male | 526 | 122 (23.2) | 217 | 76 (35) | 88 | 32 (36.4) |

| Rural | 966 | 251 (25.1) | 456 | 146 (32.0) | 137 | 58 (42.3) |

| Periurban | 378 | 58 (15.3) | 148 | 37 (25.0) | 63 | 20 (31.8) |

Thirty-six individuals were excluded due to inconclusive serology results.

Figure 1. Prevalence of T. cruzi infection in Punata, Bolivia community serosurvey, by age.

N represents total number of individuals in each age group.

Cardiac Disease According to T. cruzi Infection

Of 632 eligible adults, 604 (95.6%) participated in the cardiac substudy; 183 (30.3%) had confirmed T. cruzi infection. Three (1.6%) seropositive participants had complete right bundle branch block (RBBB) on ECG (1.6%) compared to none of the seronegative participants (p=0.008) (Table 2). Nineteen T. cruzi-infected participants had any conduction system defect, compared with eight seronegative participants (10.4% vs. 1.9%, p<0.001). The percentages with bradycardia were similar among those with and without T. cruzi infection (3.8 versus 4.7% respectively for heart rate less than 50 beats per minute).

Table 2.

Electrocardiography findings in individuals with and without T. cruzi infection

| ECG Findingsa | Seropositive (N=183) | Seronegative (N=421) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate and rhythm | |||||

| Heart Rate <60 | 63 (34.4) | 128 (30.4) | 1.202 | 0.815-1.764 | 0.329 |

| Heart Rate <50 | 7 (3.8) | 20 (4.8) | 0.797 | 0.280-2.009 | 0.613 |

| Mean Heart Rate (SD) | 62.65 (9.4) | 62.66 (10.6) | |||

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0.0 | 1.000b | |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia (PVC) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0.0 | 0.303b | |

| Bundle branch blocks (BBB) | |||||

| RBBB (complete) | 3 (1.6) | 0 | 0.0 | 0.027b | |

| LAFB | 7 (3.8) | 5 (1.2) | 3.309 | 0.888-13.378 | 0.052b |

| LPFB | 3 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | 7.000 | 0.556-368.280 | 0.085b |

| Bifasicular block | 6 (3.3) | 2 (0.5) | 7.102 | 1.250-72.337 | 0.006 |

| Any BBBc | 19 (10.4) | 8 (1.9) | 5.981 | 2.432-16.061 | <0.001 |

| Incomplete RBBB | 13 (7.1) | 29 (6.9) | 1.034 | 0.481-2.112 | 0.924 |

| Other abnormalities | |||||

| 1° AV block | 4 (2.2) | 4 (1.0) | 2.330 | 0.428-12.633 | 0.253b |

| ST-T changes | 13 (7.1) | 13 (3.09) | 2.400 | 1.001-5.739 | 0.025 |

| Low Voltage QRS | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0.0 | 1.000b | |

| Normal ECG | 88 (48.1) | 228 (54.2) | 0.171 | ||

Values are n (%). AV: atrioventricular; BBB: bundle branch block; LAFB: left anterior fasicular block; LPHB: left posterior hemiblock; PVC: premature ventricular contraction; RBBB: right bundle branch block.

No participant was found to have LVH or an abnormal initial portion of their QRS complex on ECG.

By 2-tailed Fisher exact test

Any complete bundle branch block (RBBB, LAFB, LPFB, bifascicular block)

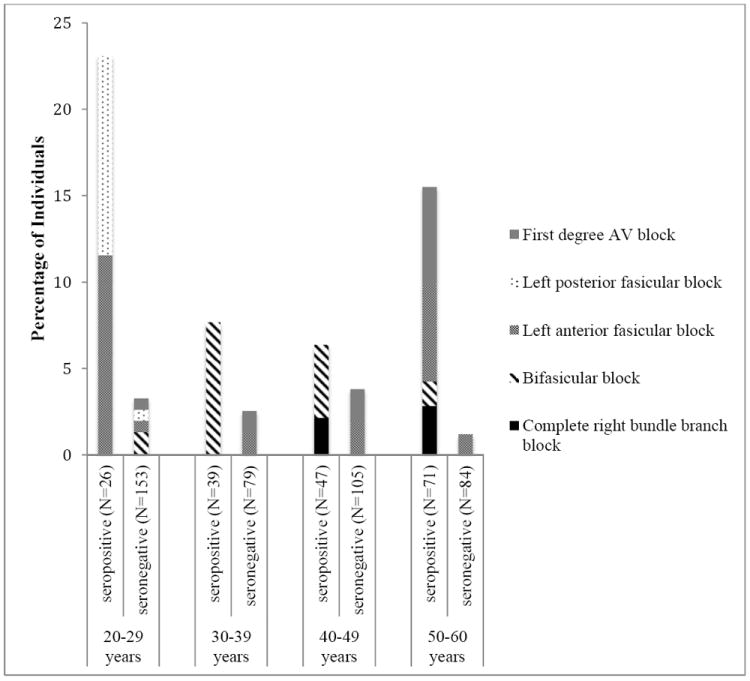

The prevalence of right bundle branch block was highest in seropositive individuals older than 40 years, whereas bifasicular blocks were read more commonly in younger seropositive participants (Figure 2). The prevalence of any conduction system defect among both seropositive and seronegative individuals was highest among those between the ages of 20 and 29 years: 23.1% and 2.6% among seropositive and seronegative individuals, respectively. In multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sex and age (by decade), bifasicular block and any conduction system defect were significantly associated with T. cruzi infection (odds ratio for bifasicular block 8.19 (95% CI 1.55-43.17), p=0.02; any conduction system defect 7.36 (2.97-18.6), p<0.001).

Figure 2. ECG Findings by Age and T. cruzi serostatus.

Per study protocol, 434 participants were scheduled for echocardiograms, but only 201 (46%) participants (78 seropositive, 123 seronegative) underwent the examination (Table 4). Participants who missed an echocardiogram were contacted by the study team by phone or by home visit to reschedule the appointment. Those who missed repeat appointments often cited the need to work and the lack of any symptomatic illness as the reasons for skipping the echocardiogram. One seronegative participant had an uninterpretable study due to body habitus; the echocardiogram was excluded from analysis. There was no sex difference between seropositive participants who did and did not present for echocardiogram; seronegative women were more likely to miss their appointment than seronegative men. Left ventricular dilatation (defined as LV end diastolic diameter > 57mm) was found in four seropositive and three seronegative participants (Table 3). Seven seropositive participants had left atrial dilatation (defined as LA >40mm) compared with only two uninfected participants (9.0% vs. 1.6%, p=0.014). One seronegative participant had an ejection fraction of 42%; two seropositive and two seronegative participants had slightly depressed ejection fractions between 51 and 54%. There was no difference in the distribution of ejection fractions by infection status (mean 68% [standard deviation 0.16] for seropositives vs 68% [0.16] for seronegatives; p=0.959 by t-test). Sixteen participants had valvulopathies not related to Chagas disease: 12 aortic sclerosis, two mitral prolapse, one mitral stenosis, and one mitral insufficiency. There was no significant difference in rates of valvular disease among participants with and without T. cruzi infection. None of the participants had an apical aneurysm or an intracavitary thrombus.

Table 4.

Comparing those who did and did not complete echocardiograms, by serostatus, in those who were scheduled for study per protocol

| Chagas seropositive | Chagas seronegative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received echo (N=78) | No echo (N=105) | Received echo (N=123) | No echo (N=128) | |

| Mean age, years | 44.0 ± 11.2 | 43.4 ± 11.6 | 37.3 ± 12.2 | 36.6 ± 11.9 |

| Female | 46 (59.0) | 61 (58.1) | 67 (54.5) | 85 (66.4) |

| Heart rate <60 | 28 (35.9) | 35 (33.3) | 67 (54.5) | 60 (46.9) |

| Heart rate <50 | 4 (5.1) | 3 (2.9) | 7 (5.7) | 13 (10.2) |

| Bifasicular block | 3 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | -- |

| Any conduction system defect | 6 (7.7) | 13 (12.4) | 6 (4.9) | 2 (1.6) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Table 3.

Echocardiography findings in individuals with and without T. cruzi infection

| Echo Findingsa | Seropositive N=78 | Seronegative N=122 | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| LV End Diastolic Diameter | 4.58 (0.94) | 4.42 (0.79) | 0.207 | ||

| LV Ejection Fraction | 0.68 (0.16) | 0.68 (0.12) | 0.959 | ||

| LA diameter | 3.00 (0.84) | 2.84 (0.68) | 0.149 | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| LV dilatation | 4 (5.1) | 3 (2.4) | 2.144 | 0.351-14.989 | 0.435b |

| LAD | 7 (9.0) | 2 (1.6) | 5.915 | 1.077-59.355 | 0.030b |

| EF<55% | 2 (2.6) | 3 (2.5) | 1.044 | 0.853-9.329 | 1.000b |

| Any Valvulopathy | 8 (10.3) | 8 (6.5) | 1.629 | 0.506-5.215 | |

| Early systolic dysfunction | 2 (2.6) | 1 (0.8) | 3.184 | 0.162-189.36 | 0.562b |

| LVH | 62 (79.5) | 96 (78.7) | 1.049 | 0.495-2.274 | 0.892 |

Values are n (%). EF: ejection fraction; LA: left atrium; LAD: left atrial dilatation; LV: left ventricle; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy.

No participant was found to have an apical aneurysm, an intracavitary thrombus, or diffuse wall motion abnormalities on echocardiogram.

By 2-tailed Fisher exact test

Discussion

Our study was one of the first in decades to evaluate the community burden of T. cruzi infection and Chagas heart disease in the inter-Andean valleys of Bolivia. Housing improvement programs began in Cochabamba in the 1990s and household insecticide application was instituted on a large scale by the Bolivian National Chagas Disease Control Program between 2000 and 2004 [15; personal communication, F. Torrico, 2009]. Our data support the success of these efforts. We found a much lower prevalence of T. cruzi infection than a study conducted in Cochabamba Department in 1988 (74% in 1988 vs 23% in our data) and a strikingly lower prevalence in children (38% in 1988 vs 5.6% in our data) [12].

Although our age range and case definitions varied from those used in the 1988 study, it is interesting to note that we also found a lower rate of bundle branch blocks among infected participants than in the 1988 study (20% in 1988 vs 10.4% in our data), and found no participants with clinically evident congestive heart failure (compared to 9% in the 1988 data) [12]. A similar study restricted to Bolivian women of childbearing age in the 1980s also showed higher rates of conduction system abnormalities than we found [11]. Nevertheless, T. cruzi infection is still a significant risk factor for conduction system defects in our data. These findings provide an optimistic picture for the future, since bundle branch blocks [10], decreased ejection fraction [16, 17], left and right ventricular dysfunction [18, 19], and abnormal diastolic function [20, 21] have all been associated with increased mortality in individuals with Chagas disease. Evidence from mouse models [22, 23] and communities [24] suggest that continued vector-borne exposure to T. cruzi may increase the risk of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Failure to down-regulate the anti-T. cruzi inflammatory immune response is widely accepted as an important driver of Chagas cardiomyopathy development and progression [25, 26]. Vector-borne parasite exposure is hypothesized to maintain sustained antigen exposure and consequent higher chronic inflammatory immune responses, contributing to Chagas cardiomyopathy. The lower rate of clinical disease in our study may reflect the better vector control over the previous decades and decreased exposure to the parasite. However, further data are needed to better understand this possible association.

Our observation of an association between T. cruzi infection and left atrial dilatation is intriguing but its clinical significance is unclear. Previous studies have found left atrial dilatation associated with right bundle branch block in infected individuals, perhaps indicating early manifestations of cardiac involvement [27-29]. Furthermore, left atrial dilatation has been linked to increased risk of sudden cardiac death in those with known Chagas cardiomyopathy [20, 21]. The most common abnormalities found on echocardiogram were valvulopathies, most commonly isolated aortic sclerosis in participants between 50 and 60 years old. This finding was consistent with prior studies, and most consistent with age-related changes [30]. We anticipated seeing a greater burden of valvular disease associated with known or suspected rheumatic heart disease, which most commonly causes mitral stenosis; it is not common to have aortic disease resulting from rheumatic heart disease without concomitant mitral involvement [31, 32]. We found no association between valvulopathies and T. cruzi infection.

Our study had several limitations. First, it is possible that those individuals who were in poor health did not present to our mobile clinic to participate in the study and we therefore underestimated the cardiac disease burden. Second, we excluded adults over age 60 to minimize non-specific cardiac disease such as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. While the work of Lima-Costa and colleagues indicates that Chagas may be a greater problem in elderly patients than was previously recognized [33, 34], prior studies have found the majority of cardiac disease developing in adults between 30 and 50 years old [9-12]. It is possible, however, that our exclusion of adults over age 60 reduced the amount of Chagas heart disease detected. Finally, our echocardiogram findings may have been affected by the low rates of echocardiogram completion. However, consensus among Chagas experts indicates that the rate of clinically-significant Chagas heart disease is rare in the absence of ECG abnormalities [35].

Conclusion

Our study found low rates of Chagas cardiomyopathy in a community endemic for T. cruzi, possibly related to the effects of widespread vector control efforts over the previous 20 years. More research is needed to better understand who, among those infected with T. cruzi, is at increased risk of progression to associated disease.

Highlights.

We conducted a community survey of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in central Bolivia.

We evaluated adults aged 20-60 years old for evidence of Chagas heart disease.

30.3% of adults were seropositive for T. cruzi infection.

Bundle branch blocks were more common among participants with T. cruzi infection.

Overall rates of Chagas cardiomyopathy were lower than in prior community studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. René Ugarte, Marco Solano Mercado, and Gimena Rojas Delgadillo for their assistance in the laboratory and in the field. We would additionally like to thank all the members of the field team who collected data and specimens for the community study, and the members of CEADES Salud y Medio Ambiente who assisted with data collection and management. In addition, the authors would like to thank the Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellows Program for funding support for Drs. Yager and Lozano Beltran.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hidron AI, Gilman RH, Justiniano J, et al. Chagas cardiomyopathy in the context of the chronic disease transition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(5):e688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rassi A, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010 Apr 17;375(9723):1388–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dias JCP, Silveira AC, Schofield CJ. The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002 Jul;97(5):603–12. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias JCP. Southern Cone Initiative for the elimination of domestic populations of Triatoma infestans and the interruption of transfusional Chagas disease. Historical aspects, present situation, and perspectives. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007 Oct 30;102(Suppl 1):11–8. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowman NM, Kawai V, Levy MZ, et al. Chagas Disease Transmission in Periurban Communities of Arequipa, Peru. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008 Jun;46(12):1822–8. doi: 10.1086/588299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. Switzerland: 2002. Report No.: 0512-3054. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teixeira ARL, Nascimento RJ, Sturm NR. Evolution and pathology in chagas disease--a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006 Aug;101(5):463–91. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coura JR. Chagas disease: what is known and what is needed--a background article. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007 Oct 30;102(Suppl 1):113–22. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maguire JH, Mott KE, Lehman JS, et al. Relationship of electrocardiographic abnormalities and seropositivity to Trypanosoma cruzi within a rural community in northeast Brazil. Am Heart J. 1983 Feb;105(2):287–94. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90529-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maguire JH, Hoff R, Sherlock I, et al. Cardiac morbidity and mortality due to Chagas’ disease: prospective electrocardiographic study of a Brazilian community. Circulation. 1987 Jun;75(6):1140–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.6.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinke T, Ueberreiter K, Alexander M. Cardiac morbidity due to Chagas’ disease in a rural community in Bolivia. Epidemiol Infect. 1988 Dec;101(3):655–60. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pless M, Juranek D, Kozarsky P, Steurer F, Tapia G, Bermudez H. The epidemiology of Chagas’ disease in a hyperendemic area of Cochabamba, Bolivia: a clinical study including electrocardiography, seroreactivity to Trypanosoma cruzi, xenodiagnosis, and domiciliary triatomine distribution. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992 Nov;47(5):539–46. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lázzari JO, Pereira M, Antunes CM, et al. Diagnostic electrocardiography in epidemiological studies of Chagas’ disease: multicenter evaluation of a standardized method. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1988 Nov;4(5):317–330. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49891998001100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le V-V, Wheeler MT, Mandic S, et al. Addition of the electrocardiogram to the preparticipation examination of college athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2010 Mar;20(2):98–105. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181d44705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Analisis De La Situacion de Salud Cochabamba 2005/2006. Ministerio de Salud y Deportes del Departamento de Cochabamba; Cochabamba, Bolivia, 2007: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viotti RJ, Vigliano C, Laucella S, et al. Value of echocardiography for diagnosis and prognosis of chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy without heart failure. Heart. 2004 Jun;90(6):655–60. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.018960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riberio ALP, Cavalvanti PS, Lombardi F, Nunes MDCP, Barros MVL, Rocha MODC. Prognostic Value of Signal-Averaged Electrocardiogram in Chagas Disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology. 2008 Jul 8;19(5):502–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rassi A, Little WC, Xavier SS, et al. Development and Validation of a Risk Score for Predicting Death in Chagas’ Heart Disease. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 24;355(8):799–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunes MdCP, de Barbosa MM, Brum VAA, Rocha MOdC. Morphofunctional characteristics of the right ventricle in Chagas’ dilated cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2003.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bestetti RB, Dalbo CM, Arruda CA, Correia Filho D, Freitas OC. Predictors of sudden cardiac death for patients with Chagas’ disease: a hospital-derived cohort study. Cardiology. 1996;87(6):481–7. doi: 10.1159/000177142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunes MCP, Barbosa MM, Ribeiro ALP, Colosimo EA, Rocha MOC. Left Atrial Volume Provides Independent Prognostic Value in Patients With Chagas Cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2009;22(1):82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bustamante JM, Rivarola HW, Fernández AR, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi reinfections in mice determine the severity of cardiac damage. Int J Parasitol. 2002 Jun 15;32(7):889–96. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrade SG, Campos RF, Sobral KSC, Magalhães JB, Guedes RSP, Guerreiro ML. Reinfections with strains of Trypanosoma cruzi, of different biodemes as a factor of aggravation of myocarditis and myositis in mice. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39(1):1–8. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822006000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acquatella H, Catalioti F, Gomez-Mancebo JR, Davalos V, Villalobos L. Long-term control of Chagas disease in Venezuela: effects on serologic findings, electrocardiographic abnormalities, and clinical outcome. Circulation. 1987 Sep;76(3):556–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutra WO, Gollob KJ. Current concepts in immunoregulation and pathology of human Chagas disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun;21(3):287–92. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f88b80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marin-Neto JA, Cunha-Neto E, Maciel BC, Simoes MV. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation. 2007 Mar 6;115(9):1109–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parada H, Carrasco H, Guerrero L, Molina C, Checos R, Martinez O. Clinical and paraclinical differences between chronic Chagas’ cardiomyopathy and primary dilated cardiomyopathies. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1989 Aug;53(2):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi MA. Microvascular changes as a cause of chronic cardiomyopathy in Chagas’ disease. Am Heart J. 1990 Jul;120(1):233–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(90)90191-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mengel JO, Rossi MA. Chronic chagasic myocarditis pathogenesis: dependence on autoimmune and microvascular factors. Am Heart J. 1992 Oct;124(4):1052–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coffey S, Cox B, Williams MJA. The Prevalence, Incidence, Progression, and Risks of Aortic Valve Sclerosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jul;63(25):2852–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravisha MS, Tullu MS, Kamat JR. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: clinical profile of 550 cases in India. Archives of Medical Research. 2003;34(5):382–7. doi: 10.1016/S0188-4409(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarny MJ, Resar JR. Diagnosis and management of valvular aortic stenosis. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2014;8(Suppl 1):15–24. doi: 10.4137/CMC.S15716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lima-Costa MFF, Barreto SM, Guerra HL. Int J Epidemiol. Chagas’ disease among older adults: branches or mainstream of the present burden of Trypanosoma cruzi infection? 2002;31:688–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.688. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lima-Costa MF, Peixoto SV, Ribeiro ALP. Chagas disease and mortality in old age as an emerging issue: 10 year follow-up of the Bambuí population-based cohort study (Brazil) International Journal of Cardiology. 2010;145(2):362–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, et al. Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2007 Nov;298(18):2171–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]