Abstract

Purpose

Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages are a prominent and effective means of communicating the risks of smoking; however, there is little research on effective types of message content and socio-demographic effects. This study tested message themes and content of pictorial warnings in Mexico.

Methods

Face-to-face surveys were conducted with 544 adult smokers and 528 youth in Mexico City. Participants were randomized to view 5–7 warnings for two of 15 different health effects. Warnings for each health effect included a text-only warning and pictorial warnings with various themes: “graphic” health effects, “lived experience”, symbolic images, and testimonials.

Results

Pictorial health warnings were rated as more effective than text-only warnings. Pictorial warnings featuring “graphic” depictions of disease were significantly more effective than symbolic images or experiences of human suffering. Adding testimonial information to warnings increased perceived effectiveness. Adults who were female, older, had lower education, and intended to quit smoking rated warnings as more effective, although the magnitude of these differences was modest. Few interactions were observed between socio-demographics and message theme.

Conclusions

Graphic depictions of disease were perceived by youth and adults as the most effective warning theme. Perceptions of warnings were generally similar across socio-demographic groups.

Keywords: Health communication, Tobacco, Smoking, Socioeconomic factors, Product labelling

Introduction

Disparities in health knowledge contribute to tobacco-related inequalities. Lower socioeconomic status (SES) groups tend to have lower health knowledge about the risks of smoking [1]. In addition, health communications and campaigns typically have less reach among lower SES groups; for example, a survey in four Western countries found that low SES respondents were less likely to have noticed anti-smoking messages on television and radio and in newspapers and magazines [2].

Health warnings on tobacco packages are one of the few forms of health communication for tobacco control that are equally likely to reach lower SES groups [2, 3]. Because health warnings are printed directly on product packaging, they have broad reach and achieve high levels of awareness among smokers and non-smokers, irrespective of socio-economic status [3]. Indeed, preliminary evidence suggests that health warnings may be more effective among lower SES groups. A study in the European Union found that younger, less-educated, and “manual worker” respondents were slightly more likely to perceive health warnings as effective [4]. Research with Brazilian smokers also found that the second round of pictorial warnings in Brazil were more effective at communicating risks and promoting thoughts about quitting among smokers with lower educational attainment [5]. These results are consistent with a US study indicating that antismoking campaign ads that were emotionally evocative and included testimonials worked better among smokers from lower than from higher SES groups [6], although other research has found no moderation by SES [7]. Similar to taxes having a greater impact among low-income smokers [8], health warning policies have the potential to offset smoking-related disparities across SES groups [9], although this has yet to be empirically established.

In contrast with the substantial evidence base on the general effectiveness of pictorial health warnings, there is relatively little research on the most effective types of individual image and message theme. To date, countries have adopted different approaches in terms of the design of message content. Pictorial messages range from abstract symbolic images to gruesome depictions of disease, although there seems to be a recent trend towards increasingly graphic images (Fig. 1). For example, Brazil has revised the pictorial warnings on cigarette packs three times since 2002, with more graphic content in each round [10].

Fig. 1.

Examples of pictorial health warnings

Health communication literature contains mixed findings on the impact of fear appeals [11]. Negative emotions, such as fear, have been hypothesized to mediate the effectiveness of health warnings [12, 13] and have been associated with increases in key outcomes such as intentions to quit, thinking about health risks, and cessation behaviour [14–17]. Qualitative research in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand suggests that graphic fear-arousing images are rated by smokers as most effective [18–21], and although only one quantitative study examining message content of health warnings has been published, the results were consistent with the qualitative literature, finding that “gruesome” images were ranked more highly [22]. Use of testimonial or narrative messages that focus on “real” experiences is another approach to eliciting emotional arousal [23]. Although testimonials are increasingly being used in other health domains, their effectiveness has yet to be formally tested in the context of cigarette package health warnings. More generally, the extent to which message content interacts with socioeconomic status is unclear. Therefore, although health warnings have the potential to reduce disparities in tobacco use, there is little evidence to indicate what types of message content will be most effective in doing so.

This study sought to examine the effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on tobacco packages among youth and adults in Mexico. The study assessed the impact of health warning themes—text-only, graphic, testimonial, lived experience, and symbolic—and the extent to which effectiveness depended on socioeconomic status (education), gender, age, and smoking status. Mexico provided an important context for this research. Mexico is the third most populous country in the Americas, and its approximately 10.9 million adult smokers place it among middle-income countries with the greatest number of smokers in the world [24, 25]. Trends in smoking prevalence also suggest that smoking is becoming more concentrated in disadvantaged groups [26].

Materials and methods

Protocol

Data were collected via face-to-face interviews conducted in Mexico City from June to August, 2010. Study sites included two large public parks, a bus terminal, and outside five Walmart stores. Trained interviewers conducted a 20 min survey using computer-assisted personal interviewing. The study was reviewed by and received ethics clearance from the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo. A complete description of the study protocol is available at: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/study/countries/Mexico.

Sample and recruitment

Participants included 544 adult smokers (19 years or older who had smoked at least one cigarette in the last month) and 528 youth (aged 16–18, including both smokers and non-smokers). To minimize self-selection bias, participants were selected by using a standard intercept technique of approaching every nth person (e.g., every third person) encountered and inviting them to participate. Participants received a 50 peso (* $4 USD) phone or gift card in appreciation of their participation.

Health warning ratings

After completing questions on socio-demographics and smoking behaviour, participants viewed a series of health warning images on a computer screen. Participants were randomized to view warnings from two of 15 health effects tested in the study. Each health effect set included 5–7 warnings depicting different themes (see below). Warnings within each set were presented in random order. Participants rated the health warnings while the image appeared on screen (see Measures). Table 2 shows the health warnings tested in the study.

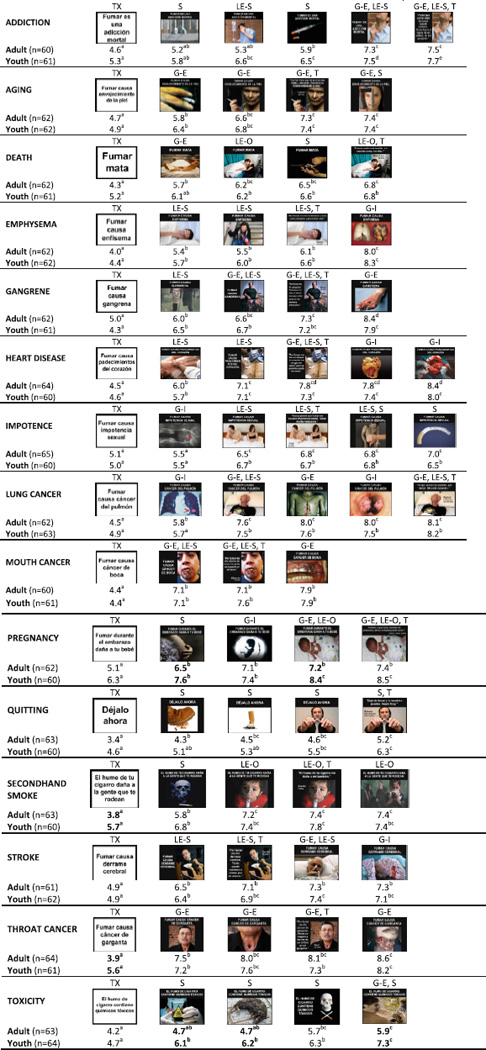

Table 2.

Mean overall effectiveness ratings of health warning labels (1–10 scale)

|

Superscript letters denote significant differences (at p < 0.05) for all pair-wise comparisons within each health effect. Warnings within the same set with the same superscript letter are not significantly different from one another. Bolded scores denote a significant difference (at overall p < 0.05 level) between adults and youth for that particular warning

TX, text; G-I, graphic internal; G-E, graphic external; LE-S, lived experience self; LE-O, lived experience other; T, testimonial; S, symbolic

Health warning theme

Warnings for each health effect included a single text-only warning, and 4–6 pictorial warnings. Images were drawn from actual health warnings implemented in different countries and adapted where necessary. Before the study, the “theme” of each pictorial warning was coded by two independent raters, with disagreements resolved by a third rater. The themes were:

Graphic health effect (vivid depiction of physical effects);

Lived experience (depiction of personal experience, including social and emotional impact, or implications for quality of life);

Symbolic (representation of message using abstract imagery or symbol); and

Testimonial (warnings with a brief narrative describing a personal consequence of smoking, written as a quote from a person in the image, accompanied by their name and age).

For testimonial warnings, the personalizing text was added to the same image used in another “standard” (non-testimonial) warning for the same health effect, to examine the incremental effect of the testimonial information. The testimonial version and its standard partner formed a pair for the purpose of analysis. An additional level of coding specified whether graphic warnings featured internal health effects (inside the body, e.g., heart or lungs) or external health effects (externally visible effect, e.g., foot or mouth). Lived experience images were also coded as either effects on self (depiction of personal experience, or quality of life implications for the smoker) or effects on others (depiction of personal experience or quality of life implications for others (e.g., children, spouse)). The text used in all warnings was the same for each warning within a particular set, with the exception of the testimonials. The coded theme(s) for each warning is indicated in Table 2.

Measures

Socio-demographics and smoking status

Demographic variables included age (continuous), sex, and education level for adults (Low = middle school or less, Moderate = high school or technical/vocational school completed, High = any university). Smoking status was determined on the basis of the item “in the last 30 days, how often did you smoke cigarettes?”, and classified as daily smoker (“every day”), non-daily smoker (“at least once a week” or “at least once in the last month”), or non-smoker (“not at all”; only for youth). Quit intentions among smokers were assessed by asking “Are you planning to quit smoking cigarettes … within the next month, within the next 6 months, sometime in the future, or are you not planning to quit?”, recorded as 0 = “not planning to quit” and 1 = any of the first three options. Among youth non-smokers, susceptibility to smoking was assessed using previously validated measures [27]. Youth were classified as “susceptible” (i.e., lacking a firm commitment not to smoke) if they selected any response other than “definitely not” on all three items asking likelihood of: trying smoking in the future, accepting a cigarette offer from a friend, and smoking a cigarette in the next year.

Health warning ratings

Participants rated each warning on a total of 11 measures using Likert scales from 1 to 10, including potential mediators of health warning impact, such as credibility, personal relevance, and affective responses, as well as four measures of perceived effectiveness: the extent to which each warning would increase concern about health risks, motivate smokers to quit, prevent youth from smoking, and a measure of “overall effectiveness”. Because of the scope of this paper and because the four measures of perceived effectiveness were highly correlated, this paper presents findings on the measure of overall effectiveness: “Overall, on a scale of 1–10, how effective is this health warning?”, where 1 = “not at all” and 10=“extremely”. A full list of the measures, including correlations between items, is available at: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/study/countries/Mexico.

Analysis

All analysis was conducted using SAS v9.2 software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Mean effectiveness ratings were calculated for the 78 individual health warnings tested in the study. Linear mixed effects (LME) models [28] were used to test all pair-wise differences between individual warnings within each of the 15 health effect sets (separately for the adult and youth samples), adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Tukey correction. Differences between the adult and youth mean scores for each individual warning were examined using t tests, adjusting for multiple comparisons using the Benjamin–Hochberg adjustment [29]. LME models were used to examine ratings of effectiveness across the 15 health effects by health warning theme. In this study, individuals rated several warnings and these ratings are correlated within individuals. LME models are well suited to analysis of correlated data [30]. Fixed effects were fit to represent the average effects of covariates on the entire population; random effects were fit to represent how an individual’s response differed from that of the population. All LME models fitted in this paper included random intercepts that describe how the mean response of any given individual differs from that of the overall population mean. Random effects were also fit for the particular “theme” that a given warning represented. These random slopes describe how the effect of that “theme” varies for a given individual compared with that of the overall population. Fixed effects were estimated for sex, age group, smoking status, health effect, and the particular warning of interest.

Five primary models were estimated in which effectiveness ratings served as the outcome. The first model examined text-only versus pictorial warnings, comparing the 15 text-only warnings (one for each health effect) with 49 pictorial warnings featuring the same text. Testimonial warnings were excluded from this analysis given that their text was different, and they displayed the same picture as their “partner” standard warning already included among the 49 warnings. The second model tested the themes of pictorial health warnings: graphic, lived experience, and symbolic, and warnings with both graphic and lived experience content. Text-only and testimonial warnings were excluded from this model, given that text-only warnings had no pictorial content, and the testimonial warnings had unique text. A third LME model examined the graphic content of warnings (coded as internal graphic, external graphic or non-graphic), in order to compare internal and external graphic health effects. A fourth model examined lived experience content (coded as effects on self, effects on others, or non-lived experience), in order to compare effects on self and effects on others. The fifth model examined the impact of testimonials, by comparing the 14 testimonials to the 14 “partner” warnings, excluding all others. All models adjusted for age group (adult vs. youth), sex, and health effect set viewed, and the testimonial analysis also included a fixed effect for whether the standard image was seen first.

The final set of models examined ratings of effectiveness by socio-demographic variables. LME models were conducted separately for adults and youth, because of different demographic questions by age group and the inclusion of non-smokers in the youth sample; the subsample of youth smokers was also analysed separately. Covariates for the adult models included age, sex, education level, smoking frequency (daily/non-daily), and quit intentions (any/none). Covariates for the youth analysis included age, sex, and smoking status (smoker, susceptible non-smoker, non-susceptible non-smoker); the smoker subsample dropped smoking status and also included smoking frequency and quit intentions.

To further examine the possible effects of socio-demographic variables, the five primary models described above were repeated with the overall sample and with each demographic subsample (adults, youth, youth smokers) to test two-way interactions between health warning theme and socio-demographic/smoking status variables; in the demographic subsample analyses, the categories of graphic internal and external were collapsed, as were lived experience effects on self and effects on others.

Results

Sample

The total sample included 544 adult smokers and 528 youth. Demographic and smoking characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and smoking characteristics

| Characteristic | Adults (n=544) % (n) | Youth (n=528) % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 51.7 (281) | 50.0 (264) |

| Female | 48.3 (263) | 50.0 (264) |

| Age (mean) | 29.3 (SD=11.6) | 17.0 (SD=0.9) |

| Education level | ||

| Low (middle school or less) | 13.1 (71) | - |

| Moderate (high school/technical/vocational school) | 46.3 (252) | - |

| High (any university) | 40.5 (220) | - |

| Middle school completed | - | 60.4 (319) |

| Partial high school | - | 7.6 (40) |

| High school or technical school completed | - | 32.0 (169) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Daily smoker | 51.7 (281) | 12.9 (68) |

| Non-daily smoker | 48.3 (263) | 36.0 (190) |

| Non-smoker | 0 | 51.1 (270) |

| Cigarette consumptiona | ||

| Cigarettes per day-daily smokers (mean) | 7.9 (SD=7.0 | 5.6 (SD=3.5) |

| Cigarettes per week-non-daily smokers (mean) | 8.7 (SD=10.3) | 5.5 (SD=5.5) |

| Quit intentionsa | ||

| Within the next month | 13.4 (73) | 13.7 (36) |

| Within the next 6 months | 11.6 (63) | 14.4 (38) |

| Sometime in the future | 29.6 (161) | 37.3 (98) |

| Not planning to quit | 45.4 (247) | 34.6 (91) |

| Smoking susceptibilityb | - | 65.6 (177) |

Among smokers (adult n=544, youth n=258)

Among youth non-smokers (n=270)

Rating individual health warnings

Table 2 shows the 78 individual health warnings tested in the study across the 15 health effects. The mean overall effectiveness ratings for each warning are shown for youth and adults, with significant differences between individual warnings within each health effect set, and between adults and youth for each of the 78 warnings (Table 2). As Table 2 indicates, text-only warnings received the lowest rating in the set for each of the 15 health effects. Adjusting for multiple comparisons, significant differences between adults and youth were observed for 7 of the 78 warnings: in all of these cases, youth rated the warning higher than adults.

Health warning type and theme

LME models examined different warning content and themes across the 15 health effect sets, adjusting for age group, sex, smoking status, and health effect set. As indicated by the statistically significant fixed effect term for pictorial versus text-only warnings (p < 0.001), pictorial warnings were rated, on average, 2.0 out of 10 points more effective than text-only warnings (adjusted means of 6.7 and 4.7, respectively). However, the random effects for pictorial versus text-only were also statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating substantial variation between individuals in this 2.0 difference (e.g., some individuals rated pictorial warnings much higher than text-only whereas others rated them lower). Combining both fixed and random effects indicated that 90.4% of respondents rated the pictorial warnings higher than the text-only warnings.

A separate LME model compared pictorial warning themes. A significant fixed effect of theme on ratings of effectiveness was observed (p < 0.001). On average, graphic warnings were rated as significantly more effective than symbolic warnings (adjusted means 7.1 and 6.2, respectively; p < 0.001) and lived experience warnings (adjusted mean = 6.2; p < 0.001). Warnings with both graphic and lived experience content were not rated significantly higher than warnings with only graphic content. There were no significant differences between warnings depicting lived experience and symbolic warnings. Again, there was substantial variation between individuals in the differences between themes, as evidenced by significant random effects terms.

Separate LME models examined the characteristics of graphic and lived experience warnings. Among graphic warnings, those depicting external health effects (adjusted mean = 7.3) were rated on average as significantly more effective than graphic warnings showing internal health effects (adjusted mean = 6.9; p < 0.001). Random effects were statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating important variation between individuals; overall, 64.1% of respondents rated the external effects higher than internal effects. In a separate model examining lived experience warnings, those depicting effects on others (adjusted mean = 7.5) were rated significantly higher (p < 0.001) than warning depicting effects on self (adjusted mean = 6.6). Random effects were again statistically significant (p < 0.001) and 80.7% of respondents rated the effects on others higher than effects on self.

A final LME model compared the 14 warnings that featured testimonial text with the 14 warnings that included the same image without testimonial text, controlling for the presentation order. On average, testimonial warnings were rated as significantly more effective than the versions with standard text (adjusted means = 7.2 and 6.8 respectively; p < 0.001). Although the random intercepts were statistically significant (p < 0.001), the random effects for testimonial were not, indicating no variation between individuals in the effect of testimonials versus not.

Socio-demographic effects

Differences by age group

Interactions were tested between age group and each of the health warning themes within each of the five models described above. A significant interaction of age group for the text-only versus pictorial analysis was observed (p = 0.04): although ratings for pictorial warnings were similar in both groups, the relative difference between pictorial and text-only warning ratings was smaller among youth (1.9 points) than adults (2.2 points). A significant interaction of age group and theme was also observed (p = 0.004): the relative difference between graphic and symbolic warning ratings was smaller among youth (0.5 points) than adults (1.1 points), although youth and adults rated the graphic labels similarly. In the graphic content analysis, the interaction between age group and graphic internal versus graphic external was not significant.

Socio-demographic differences among adults

A LME model was conducted with the adult sample to examine whether warning effectiveness was associated with age, sex, education level, smoking frequency, and quit intentions, while adjusting for health effect. Females rated warnings higher than males (0.3 point difference; p = 0.02), as did older adults compared with younger participants (0.02 points per year; p < 0.001). Smokers who intended to quit rated the warnings significantly higher than those with no quit intentions (0.6 point difference; p < 0.001). Respondents with lower education levels rated the warnings as more effective: low education respondents rated the warnings significantly higher than those with moderate (0.5 point difference; p = 0.02) or high (1.0 point difference; p < 0.001) education; respondents with moderate education rated the warnings significantly higher than high education respondents (0.4 points, p = 0.007). No differences were observed between daily and non-daily smokers.

Within the adult sample, two-way interactions between socio-demographic factors and message theme were examined for each of the five LME models described in the previous section (e.g., text-only vs. pictorial, message themes, testimonial vs. not, etc.). No significant interactions were found.

Socio-demographic differences among youth

An LME model was conducted with the youth sample to examine whether warning effectiveness was associated with age, sex, and smoking status, while controlling for health effect. Age and sex were not significantly associated with effectiveness ratings among youth. However, a main effect of smoking status was observed (p = 0.03): susceptible non-smokers rated labels 0.5 points higher than non-susceptible non-smokers (p = 0.02), with no differences between ratings of smokers and non-susceptible non-smokers.

When each of the five models described above was conducted with the youth sample to test the interactions between the socio-demographic factors and message theme, there was a significant interaction of smoking status and testimonial theme (p = 0.02): although all three groups (non-susceptible non-smokers, susceptible non-smokers, and smokers) rated testimonial warnings similarly, the relative difference between ratings for testimonial and standard warnings was smaller among susceptible non-smokers because of their higher ratings for the standard warnings.

Additional analyses were conducted among youth smokers to examine whether cigarette consumption and quit intentions were associated with warning effectiveness. No significant effects were observed.

Discussion

The World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) has established international standards for health warnings on cigarette packages [31, 32]. The current study is among the first to systematically test the content of pictorial health warnings, which have been implemented in more than 30 countries. [33] Among Mexican respondents, adults with lower education levels rated the warnings as significantly more effective than respondents with higher levels of education. This is consistent with previous research conducted in high-income countries [2, 3, and 34].

The findings provide additional support for the superiority of pictorial versus text-only warnings. Previous evidence suggests that pictorial warnings are more likely to be noticed, are associated with greater levels of engagement and emotional arousal, and may “wear out” more slowly than text-only warnings [3]. This study also found that individuals with lower socio-economic status (education) were more likely to rate pictorial warnings as effective. This finding is consistent with the general principle that text-only warnings require adequate literacy skills [34, 35]. This is particularly important considering that smokers in most countries report lower levels of education than the general public [36]. In contrast, pictures can be understood by individuals who are illiterate, including young children and those who are literate in a language other than that used for text warnings.

The findings add to the evidence that “graphic” fear-arousing messages are perceived by adults and youth to be the most effective message theme. All SES groups rated “graphic” messages as most effective. Graphic images that depicted “external” effects outside of the body, such as on the face, were rated as most effective. In addition to conveying the physical effects of smoking, graphic external images are particularly unpleasant in terms of their aesthetic quality. Health warnings that highlight negative consequences on physical appearance and negative social consequences may be particularly effective among young people, for whom other aspects of chronic disease may seem more remote.

Symbolic warnings and images depicting the social and emotional impact of warnings (i.e., “lived experience”) were perceived as less effective than graphic images. In addition, warnings integrating “lived experience” content with graphic images were no more effective than graphic messages alone. However, “lived experience” warnings depicting the effects of smoking on “others” were perceived as more effective than warnings depicting effects on oneself. Pictorial health warnings were implemented in Mexico in September 2010, shortly after this study was conducted [33]. It is notable that the predominant theme of the Mexican warnings is the effect of smoking on important others, including children and spouses. Our findings provide preliminary support for the potential impact of this approach, bearing in mind that graphic warnings were rated more effective overall.

Our results are generally consistent with research evaluating anti-tobacco television advertisements. For example, research conducted among youth indicates that television advertisements using “visceral negative” themes and “personal testimonials” had the strongest and most consistent effects on appraisal, recall, and level of engagement [6, 37]. Countries such as Chile have implemented testimonial warnings on cigarette packs and countries such as Canada and the United States are preparing to implement similar warnings. As far as we are aware, a single qualitative study has tested narrative messages with regard to health warnings. This study found that using a personal story was viewed positively, but participants wanted to see a story that focussed more on the negative side-effects of smoking, rather than the positively framed narrative that was presented [38].

Overall, this study suggests that youth and adults, smokers and non-smokers, and adults of varying education levels rate health warnings in a generally consistent manner. Although perceptions of warnings differed significantly among adults according to several characteristics, the magnitude of these differences were modest. In other words, the warnings that did well with one subgroup seemed to do well with other subgroups. This is consistent with research on mass media intervention, which indicates that the characteristics of advertisements are more important in determining effectiveness than demographic factors such as race/ethnicity or age [6, 39].

Limitations

This study did not use probability-based sampling techniques to select a representative sample of adults and youth from Mexico City. However, an intercept technique was used to minimize self-selection bias and succeeded in recruiting a heterogeneous sample. Nevertheless, the study sample cannot be said to be representative of all adult smokers or youth. In addition, the study setting in which participants rated a series of warnings after viewing the warnings for a brief amount of time does not replicate repeated exposure to health warnings in “real life.” Although stimuli in this study were shown to participants on a computer screen, the results found here are generally consistent with another study that used a similar methodology but showed people mock packs with warnings [40]. It should also be noted that measures of perceived effectiveness do not necessarily predict responses to warnings implemented on packages. Similar studies should be conducted amongst populations that have already been exposed to pictorial warnings, so that governments maximize the impact of this educational intervention. However, there is no way to replicate “real world” exposure to health warnings in an experimental study, and this study uses conventional methodology for evaluating media campaign concepts and materials before implementation.

Conclusions

Health warnings have emerged as an important element of tobacco control, particularly in low and middle-income countries, where fewer resources exist to support mass media and education campaigns. Although an increasing number of countries have adopted pictorial warnings on cigarette packages, there is an immediate need for evidence to guide the selection of content and message themes.

There is a general expectation both within the research and regulatory community that pictorial health warnings need to be targeted at sub-populations to be effective. However, this study suggests that the same warnings are effective across a range of socio-demographic groups, and that individuals from lower SES groups report equal if not greater efficacy of health warnings. Warnings featuring graphic depictions of disease were rated by all groups as most effective, and all groups indicated that adding testimonial information to warnings may increase their effectiveness. Overall, our findings emphasise that package-based health warnings can be effective across SES groups and, by virtue of their broad reach, have the potential to reduce tobacco-related inequities.

New pictorial warnings were implemented in Mexico in September 2010, shortly after this study. The new warnings cover 30% of the front and 100% of the back and one side of the pack. Future research should be conducted in Mexico to assess the population-based impact of the newly implemented warnings and the extent to which it may differ across sub-groups and lower socioeconomic status groups.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Co´ dice Comunicacio´ n Dia´logo y Conciencia S·C. and Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica (INSP) for their assistance in conducting this work. We would also like to acknowledge the assistance of Ana Dorantes (field manager for Mexico) and Samantha Daniel. The project described in this paper was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1 P01 CA138-389-01: “Effectiveness of Tobacco Control Policies in High vs. Low Income Countries”). Additional support was provided by the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute Junior Investigator Award.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siahpush M, McNeill A, Hammond D, Fong GT. Socio-economic and country variations in knowledge of health risks of tobacco smoking and toxic constituents of smoke: Results from the 2002 International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl III):iii65–iii70. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callery W, Hammond D, Reid JL, Fong GT, Borland R, Cummings KM. Socioeconomic variation in the reach of various sources of anti-smoking information: Findings from the ITC 4-Country Survey [poster presentation]. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; February 2008; Portland, Oregon. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond D. Health warnings on tobacco packages: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327–337. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Commission. Eurobarometer: survey on tobacco [Analytical report] [Accessed 12 April 2010];2009 Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/Flash/fl_253_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thrasher J, Villalobos V, Skolt A, Fong GT, Perez C, Sebrie´ EM, Boada M, Figueiredo V, Bianco E. Assessing the impact of cigarette package warning labels: a cross-country comparison in Brazil, Uruguay and Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52(Sup 2):S206–S215. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durkin SJ, Biener L, Wakefield M. Effects of different types of antismoking ads on reducing disparities in smoking cessation among socioeconomic subgroups. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2217–2223. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niederdeppe J, Fiore MC, Baker TB, Smith SS. Smoking cessation media campaigns and their effectiveness among socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged populations. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):916–924. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.117499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaloupka FJ, Warner KE. The economics of smoking. In: Cuyler AJ, Newhouse JP, editors. Handbook of health economics. Amsterdam: Elsiever; 2000. pp. 1539–1627. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Link B. Epidemiological sociology and the social shaping of population health. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49:367–384. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Instituto Nacional de Cancer. Brazil: Health warnings on tobacco products. Rio di Janeiro: Ministereo de Saude, Instituto Nacional de Cancer. 2009 Images available at: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/healthwarningimages/country/brazil. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flay BR, Burton D. Effective mass communication strategies for health campaigns. In: Atkin C, Wallack L, editors. Mass communication for public health: complexities and conflicts. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sweet KM, Willis SK, Ashida S, Westman JA. Use of fear appeal techniques in the design of tailored cancer risk communication messages: implications for healthcare providers. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3375–3376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald P, Brown KS, Cameron R. Graphic Canadian warning labels and adverse outcomes: evidence from Canadian smokers. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1442–1445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott & Shanahan Research. Developmental research for new Australian health warnings on tobacco products: stage 1. [Accessed 13 July 2009];Prepared for the population health division department of health and ageing, commonwealth of Australia. 2002 Sep; Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/474DA5DAC70608F2CA2571A1001C7DFE/$File/warnings_stage1.pdf.

- 16.Peters E, Romer D, Slovic P, Hall Jamieson K, Wharfield L, Mertz CK, Carpenter SM. The impact and acceptability of Canadian-style cigarette warning labels among U.S. smokers and nonsmokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(4):473–481. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kees J, Burton S, Andrews JC, Kozup J. Understanding how graphic pictorial warnings work on cigarette packaging. J Publ Pol Market. 2010;29(2):115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Les Etudes de Marche Createc. Final report: qualitative testing of health warning messages. Prepared for Health Canada. 2006 Jun [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decima Research. Testing of health warning messages and health information messages for tobacco products, executive summary. Prepared for Health Canada. 2009 Jun [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott & Shanahan Research. Developmental research for new Australian health warnings on tobacco products: stage 2. [Accessed 13 July 2009];Prepared for the Australian population health division department of health and ageing, commonwealth of Australia. 2003 Aug; Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/474DA5DAC70608F2CA2571A1001C7DFE/$File/warnings_stage2.pdf.

- 21.BRC Marketing & Social Research. Smoking health warnings stage 1: the effectiveness of different (pictorial) health warnings in helping people consider their smoking-related behaviour. Prepared for the New Zealand Ministry of Health. 2004 May [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thrasher JF, Allen B, Anaya-Ocampo R, Reynales LM, Lazcano- Ponce EC, Hernandez-Avila M. Ana´lisis del impacto en fumadores Mexicanos de los avisos gra´ficos en las cajetillas de cigarros [Analysis of the impact of cigarette package warning labels with graphic images among Mexican smokers] Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48:S65–S75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella J. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(3):221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica. Encuesta Mundial de Tabaquismo en Adultos, Mexico 2009 [Global Adult Tobacco Survey, Mexico 2009] Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica & Pan American Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campuzano JC, Hernandez-Avila M, Samet J, Mendez I, Tapia R, Sepulveda J. Comportamiento de los fumadores en Mexico segun las Encuestas Nacionales de Adicciones 1988 a 1998. In: Valde´s-Salgado R, Lazcano-Ponce E, Hernandez-Avila M, editors. Primer informe sobre combate al tabaquismo: Me´xico ante el Convenio Marco para el Control del Tabaco. Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica; 1998. pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. New Jersey: Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2004. Chapter 8: linear mixed effects models; pp. 187–235. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Available at: http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Elaboration of guidelines for implementation of article 11 of the convention. 2008 Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop3/FCTC_COP3_7-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond D. Tobacco labelling resource [website] [Accessed 15 April 2011];2009 Available at: http://www.tobaccolabels.org. [Google Scholar]

- 34.CRE´ ATEC? Market Studies. Effectiveness of health warning messages on cigarette packages in informing less literate smokers, final report. Prepared for Communication Canada. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malouff J, Gabrilowitz D, Schutte N. Readability of health warnings on alcohol and tobacco products. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(3):464. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.464-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reid JL, Hammond D, Driezen P. Socioeconomic status and smoking in Canada, 1999–2006: has there been any progress on disparities in tobacco use? Can J Public Health. 2010;101(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/BF03405567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terry-McElrath Y, Wakefield M, Ruel E, Balch GI, Emery S, Szczypka G, Clegg-Smith K, Flay B. The effect of anti-smoking advertisement executional characteristics on youth comprehension, appraisal, recall, and engagement. J Health Commun. 2005;10(2):127–143. doi: 10.1080/10810730590915100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Western Opinion/NRG Research Group. Illustration based health information messages: concept testing. [Accessed 12 April 2010];Prepared for Health Canada. 2006 Aug; Available at: http://www.tobaccolabels.ca/healt/canada2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Cancer Institute. Tobacco control monograph No. 19. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. Jun, The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. NIH Pub. No. 07-6242. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thrasher JF, Arillo-Santillan E, Villalobos V, Perez-Hernandez R, Hammond D, Carter J, Sebrie E, Sansores R, Regalado-Pineda J. Can cigarette package warning labels address smoking-related health disparities?: field experiments among Mexican smokers to assess the impact of textual content. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9899-8. (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]