Abstract

The entorhinal cortex and other hippocampal and parahippocampal cortices are interconnected by a small number of GABAergic nonpyramidal neurons in addition to glutamatergic pyramidal cells. Since the cortical and basolateral amygdalar nuclei have cortex-like cell types and have robust projections to the entorhinal cortex, we hypothesized that a small number of amygdalar GABAergic nonpyramidal neurons might participate in amygdalo-entorhinal projections. To test this hypothesis we combined Fluorogold (FG) retrograde tract tracing with immunohistochemistry for the amygdalar nonpyramidal cell markers glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), parvalbumin (PV), somatostatin (SOM), neuropeptide Y (NPY), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and the m2 muscarinic cholinergic receptor (M2R). Injections of FG into the rat entorhinal cortex labeled numerous neurons that were mainly located in the cortical and basolateral nuclei of the amygdala. Although most of these amygdalar FG+ neurons labeled by entorhinal injections were large pyramidal cells, 1–5% were smaller long-range nonpyramidal neurons (LRNP neurons) that expressed SOM, or both SOM and NPY. No amygdalar FG+ neurons in these cases were PV+ or VIP+. Cell counts revealed that LRNP neurons labeled by injections into the entorhinal cortex constituted about 10–20% of the total SOM+ population, and 20–40% of the total NPY population in portions of the lateral amygdalar nucleus that exhibited a high density of FG+ neurons. Sixty-two percent of amygdalar FG+/SOM+ neurons were GAD+, and 51% were M2R+. Since GABAergic projection neurons typically have low perikaryal levels of GABAergic markers, it is actually possible that most or all of the amygdalar LRNP neurons are GABAergic. Like GABAergic LRNP neurons in hippocampal/parahippocampal regions, amygdalar LRNP neurons that project to the entorhinal cortex are most likely involved in synchronizing oscillatory activity between the two regions. These oscillations could entrain synchronous firing of amygdalar and entorhinal pyramidal neurons, thus facilitating functional interactions between them, including synaptic plasticity.

Keywords: retrograde tract tracing, long-range GABAergic neurons, parasubiculum, entorhinal cortex, nonpyramidal neurons, prefrontal cortex

The parahippocampal region, consisting of the entorhinal and perirhinal cortices, is an important part of the medial temporal lobe memory system (Squire and Zola-Morgan, 1991). It relays sensory information from the neocortex to the hippocampus and then transmits hippocampal outputs back to the neocortex for memory storage. The entorhinal cortex, which projects directly to the hippocampus, receives robust inputs from the amygdala that have been shown to be involved in fear conditioning and the facilitation of long-term memory consolidation by emotional arousal (Roeslor et al., 2002; Majak and Pitkanen, 2003; McIntyre et al., 2012). Various aspects of fear learning and memory involve synchronization of theta activity in the basolateral amygdala and dorsal hippocampus (Seidenbacher et al. 2003; Pape et al., 2005; Narayanan et al., 2007a, b). Since the dorsal hippocampus and basolateral amygdala are not directly interconnected, synchronization of theta activity between these structures may involve a relay in the entorhinal cortex (Mizuseki et al., 2009). These coherent oscillations produce recurring time windows that facilitate synaptic interactions, including synaptic plasticity involved in mnemonic function (Paré et al., 2002). In fact, in vivo electrophysiological studies have shown that pyramidal projection neurons and interneurons in the basolateral amygdala fire at opposite phases of entorhinal theta (Paré and Gaudreau, 1996).

Although glutamatergic pyramidal cells are the main cell type involved in the interconnections of the various cortical structures of the medial temporal lobe memory system, recent studies suggest that a small number of GABAergic nonpyramidal neurons participating in these interconnections are critical for synchronizing oscillatory activity in these structures (Jinno et al., 2007; Meltzer et al., 2012; Caputi et al., 2013). In fact, all major portions of the medial temporal lobe memory system are interconnected by various subpopulations of nonpyramidal GABAergic projection neurons (Jinno, 2009; Caputi et al., 2013). The main amygdalar nuclei projecting to the entorhinal cortex and other cortices of the medial temporal lobe memory system are the basolateral and cortical nuclei (the corticobasolateral nuclear complex of the amygdala; CBL) which contain neurons that resemble those of the cerebral cortex (McDonald, 1992a; McDonald, 2003; Sah et al., 2003). The principal neurons in the CBL are pyramidal-like projection neurons that utilize glutamate as an excitatory neurotransmitter, whereas most nonpyramidal neurons in the CBL are interneurons that utilize GABA as an inhibitory neurotransmitter (McDonald, 1982, 1985, 1992a, 1992b, 1996, 2003; Millhouse and deOlmos, 1983; Fuller et al, 1987; Carlson, 1988, McDonald and Augustine, 1993). Like the cortex, the CBL contains at least four distinct subpopulations of GABAergic nonpyramidal neurons that can be distinguished on the basis of their content of calcium-binding proteins and peptides, including: (1) parvalbumin (PV), (2) somatostatin (SOM), (3) vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), and (4) cholecystokinin (CCK) (Kemppainen and Pitkänen, 2000; McDonald and Betette, 2001; McDonald and Mascagni, 2001, 2002, Mascagni and McDonald, 2003; Mascagni et al., 2009). In addition, it has been demonstrated that the expression of neuropeptide (NPY) defines a distinct subpopulation of SOM+ neurons in the CBL (McDonald, 1989; McDonald et al., 1995). A previous study that mainly focused on the interconnections of the parahippocampal region, but also included the lateral amygdalar nucleus in the same horizontal sections, demonstrated that some NPY neurons were involved in the interconnections of these areas, including nonpyramidal NPY+ neurons in the lateral nucleus that had projections to the entorhinal cortex (Kohler et al., 1986). The present study combined Fluorogold retrograde tract tracing with immunohistochemistry for nonpyramidal cell markers to more thoroughly investigate the involvement of nonpyramidal neurons in the projections of the amygdala to the entorhinal region.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Injections and Tissue Preparation

A total of 11 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–350g; Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) received either unilateral (n = 9) or bilateral (n = 2) injections of Fluorogold (FG) into some of the main cortical areas targeted by the basolateral amygdala (Pitkanen et al., 2000). The bilateral injections (all into the entorhinal/subicular region) were made after analysis of rats with unilateral injections of this region revealed that the average number of retrogradely-labeled neurons in the contralateral amygdala was less than 1 per section, consistent with previous anterograde and retrograde tract tracing studies of these projections (Pikkarainen et al., 1999; Majnak and Pitkanen, 2003). All experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee (IACUC) of the University of South Carolina. All experiments were conducted in a manner that minimized suffering and the number of animals used.

Rats were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic head holder (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) equipped with a nosecone to maintain isoflurane inhalation during surgery. Iontophoretic injections of 2% FG (hydroxystilbamidine; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in saline were made into the cortex via glass micropipettes (40 µm inner tip diameter) using a Midgard high voltage current source set at 1.0–2.0 µA (7 s on, 7 s off, for 20–40 min). Stereotaxic coordinates were obtained from an atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 1997). In some cases (e.g., R39; Fig. 1) two injections 0.5 mm apart were made along the same pipette track to produce an oval injection site. In one case (R51, Fig. 1) two injections were made with two different pipettes spaced 0.5 mm apart along the mediolateral axis to produce a large flattened injection site. The cortical areas injected were in the lateral entorhinal cortex and/or adjacent ventral subicular region (8 rats), medial prefrontal cortex (1 rat), lateral prefrontal cortex (1 rat) or insular cortex (1 rat). Micropipettes were left in place for 10 minutes, and then slowly withdrawn with the current reversed to prevent FG from flowing up the pipette track. After a 5 day survival period, 8 rats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (85mg/kg), xylazine (8mg/kg) and acepromazine (4mg/kg) and then perfused intracardially with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) containing 1.0 % sodium nitrite (50 ml), followed by 4.0% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 (1 liter). Three rats with unilateral injections of FG received unilateral injections of colchicine into the lateral cerebral ventricle on the FG-injected side via a microsyringe (100 µg colchicine dissolved in 10µl distilled water) after a 5 day survival period; one day later these rats were perfused as described above. Following perfusion, all brains were removed and postfixed for 3 hours in 4.0% paraformaldehyde. Brains were sectioned on a vibratome at a thickness of 50 µm in the coronal plane and processed for immunohistochemistry in wells of tissue culture plates.

Figure 1.

Drawings showing the locations of the FG injection sites in the brains used for this study. The letters “L” (left) and “R” (right) in two of the brains (R40 and R41) indicate whether the injection site in these two bilaterally-injected rats was on the left or right side. Drawings of brain sections are from the atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997). Abbreviations: AID, dorsal agranular insular cortex; AIP, posterior agranular insular cortex; AIV, ventral agranular insular cortex; DI, dysgranular insular cortex; DLEA, dorsolateral entorhinal area, GI, granular insular cortex; IL, infralimbic cortex; PaS, parasubiculum; PL, prelimbic cortex; S2, secondary somatosensory cortex; VLEA, ventrolateral entorhinal area; VMEA, ventromedial entorhinal area; VS, ventral subiculum. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Immunoperoxidase staining

In all brains a series of sections through the injection site and basolateral amygdala (bregma levels −1.8 to −4.6) at 150–300 µm intervals was incubated in a guinea pig FG antibody (1:4000; donated by Dr. Lothar Jennes, University of Kentucky) overnight at 4° C. These sections were then processed for avidin-biotin peroxidase immunohistochemistry using a guinea pig Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Nickel-enhanced DAB (3, 3'-diaminobenzidine-4HCl, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) was used as a chromogen to generate a black reaction product (Hancock, 1986). All antibodies were diluted in a solution containing 1% normal goat serum, 0.4 % Triton-X 100, and 0.1 M PBS. These sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, dried overnight, counterstained with pyronin Y (a pink Nissl stain), dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA).

FG/SOM/NPY and FG/PV/VIP triple labeling experiments

In the eight non-colchicine-injected rats, two series of sections through the basolateral amygdala at 250 µm intervals were incubated in one of two different primary antibody cocktails overnight at 4° C: (1) an anti-FG/SOM/NPY cocktail, or (2) an anti-FG/PV/VIP cocktail. In some cases with parahippocampal region injections in which the immunoperoxidase preparations revealed little staining at rostral amygdalar levels, only the levels that contained significant retrograde labeling were processed for triple-labeling immunofluorescence. All antibodies were diluted in a solution containing 1% normal goat serum, 0.4 % Triton-X 100, and 0.1 M PBS. The following primary antibodies were used: (1) a guinea pig polyclonal FG antibody (1:2000; donated by Dr. Lothar Jennes, University of Kentucky); (2) a mouse monoclonal SOM antibody (1:4000; donated by Dr. Alison Buchan, University of British Columbia); (3) a rabbit polyclonal NPY antibody (1:3000; Bachem Americas, Torrance, CA); (4) a mouse monoclonal PV antibody (1:5000; SWANT, Marly, Switzerland), and (5) a rabbit polyclonal VIP antibody (1:4000; Immunostar, Hudson, WI). After incubation in the primary antibody cocktails, sections were rinsed in 3 changes of PBS (10 min each), and then incubated in a cocktail of three secondary antibodies for 3 hrs at room temperature (1:400; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR): (1) goat anti-guinea pig AlexaFluor-488; (2) goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor-546; and (3) goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor-633. Sections were then rinsed in 3 changes of PBS (10 min each) and mounted on glass slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories).

FG/SOM/GAD and FG/SOM/M2R triple labeling experiments

In the three colchicine-injected rats, sections through the amygdala at 250 µm intervals were incubated in a primary antibody cocktail consisting of anti-FG/SOM/GAD (glutamic acid decarboxylase) (cases R51 and R54) or anti-FG/SOM/M2R (m2 muscarinic cholinergic receptor) (cases R31, R51, and R54). A previous study demonstrated that M2R is expressed in amygdalar neurons that contain SOM and NPY (McDonald and Mascagni, 2011). Colchicine was used in these experiments because it inhibits axonal transport of GAD and M2R from perikarya due to its disruption of microtubules, thereby increasing perikaryal levels of these substances. Previous studies have shown that perikaryal levels of GABAergic markers in many GABAergic projection neurons are below the level of immunohistochemical detectability (Tóth and Freund, 1992; Tóth et al., 1993). Likewise, previous studies of M2R have shown that colchicine increases perikaryal levels of M2R-ir in M2R+ neurons of the amygdala (McDonald and Mascagni, 2011). To maximize GAD staining, antibodies used in R51 and R54 were diluted in a solution containing 1% normal goat serum in 0.1 M PBS with no Triton-X 100 added (Jinno and Kosaka, 2002). Antibodies used in R31 were diluted in a solution containing 1% normal goat serum, 0.4 % Triton-X 100, and 0.1 M PBS. The following primary antibodies were used in the FG/SOM/GAD experiments: (1) a guinea pig polyclonal FG antibody (1:2000; donated by Dr. Lothar Jennes); (2) a rabbit polyclonal SOM-28 antibody (1:8000; Bachem); and (3) a mouse monoclonal GAD67 antibody (1:600; Millipore, Temecula, CA). The following primary antibodies were used in the FG/SOM/M2R experiments: (1) a guinea pig polyclonal FG antibody (1:2000; donated by Dr. Lothar Jennes); (2) a mouse monoclonal SOM antibody (1:4000; donated by Dr. Alison Buchan); and (3) a rabbit polyclonal M2R antibody (1:600; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). After incubation in the primary antibody cocktails for 2 days (R31) or 8 days (R51 and R54), sections were rinsed in 3 changes of PBS (10 min each), and then incubated in a cocktail of three secondary antibodies for 3 hrs at room temperature (1:400; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR): (1) goat anti-guinea pig AlexaFluor-488; (2) goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor-546; and (3) goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor-633. Sections were then rinsed in 3 changes of PBS (10 min each) and mounted on glass slides using Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Antibody Specificity

The neuronal marker antibodies used in this investigation have been characterized and used extensively in previous studies of the basolateral amygdala and cerebral cortex (McDonald, 1989; McDonald and Mascagni, 2001, 2002, 2007; 2010, 2011; Mascagni and McDonald, 2003; Apergis-Schoute et al., 2007). Each antibody produced the characteristic pattern of labeling for each of the neuronal subpopulations seen in previous studies.

Analysis

Injection sites (processed for immunoperoxidase) were mapped onto template drawings taken from an atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 1997) using a drawing tube attached to an Olympus BX51 microscope under bright-field illumination. The distribution of FG+ neurons in the amygdala in immunoperoxidase/Nissl stained sections was also analyzed under bright-field illumination; in three cases (R13, R38, and R41L) amygdalar FG+ neurons were mapped at three levels spaced 1 mm apart using a drawing tube attached to an Olympus BX51 microscope.

Amygdalar sections processed for immunofluorescence were examined with a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope. Fluorescence of AlexaFluor-488, AlexaFluor-546, and AlexaFluor-633 dyes was analyzed using filter configurations for sequential excitation/imaging via 488 nm, 543 nm, and 633 nm channels. FG+ neurons that also exhibited immunostaining for one or more of the other neurochemicals investigated (SOM, NPY, PV, VIP, GAD, and M2R) were plotted at 0.5 mm intervals through the amygdala onto template drawings taken from an atlas of the rat brain (Paxinos and Watson, 1997). Amygdalar nuclei and most cortical areas were identified using the Paxinos and Watson atlas, with the exception of the lateral entorhinal cortex, which was divided into three main areas according to the description by Krettek and Price (1977): dorsolateral entorhinal area (DLEA), ventrolateral entorhinal area (VLEA), and ventromedial entorhinal area (VMEA). The locations of labeled neurons at each level were determined using anatomical cues, including the staining patterns of the neuronal markers (which differed in the various nuclei of the amygdala) and their relationship to fiber bundles (e.g., the external and intermediate capsules) as in a previous study in our lab (McDonald et al., 2012). Control sections were processed with one of the antibodies omitted from the primary antibody cocktail; in all cases only the labeling with the secondary fluorescent antibodies corresponding to the non-omitted primary antibodies was observed, and only on the appropriate channel. These results indicated that the secondary antibodies were specific for guinea pig, rabbit, or mouse immunoglobulins, and that there was no “crosstalk” between channels (Wouterlood et al., 1998). Digital images were adjusted for brightness and contrast using Photoshop 6.0 software.

Results

FG injections into the parahippocampal region

Pattern of FG retrograde labeling in the amygdala

Eight rats received injections into the parahippocampal region. Since two of these rats had bilateral injections, and there was no significant contralateral projection (see above), there were a total of 10 cases with these injections. Cases with injections that had extensive involvement of the rostral portion of the dorsolateral entorhinal area (DLEA; R13 and R39) had numerous FG+ retrogradely-labeled neurons in most nuclei of the amygdala (Figs. 1–3). However, FG+ neurons were sparse in the the central nucleus, intercalated nuclei (IN), posterodorsal medial nucleus (Mpd), and the rostral pole of the anterior basolateral nucleus (BLa) (Figs. 2B, 3). An injection into the caudal pole of the DLEA (R38; Fig. 1) produced retrograde labeling in many of the same nuclei, but the density of labeled neurons was much less (Fig. 3). An injection that involved the deep layers of DLEA and the underlying ventral subiculum (R39; Fig. 1) produced retrograde labeling that was similar to that seen in R13, but the density of retrograde labeling in the basolateral nuclei was greater.

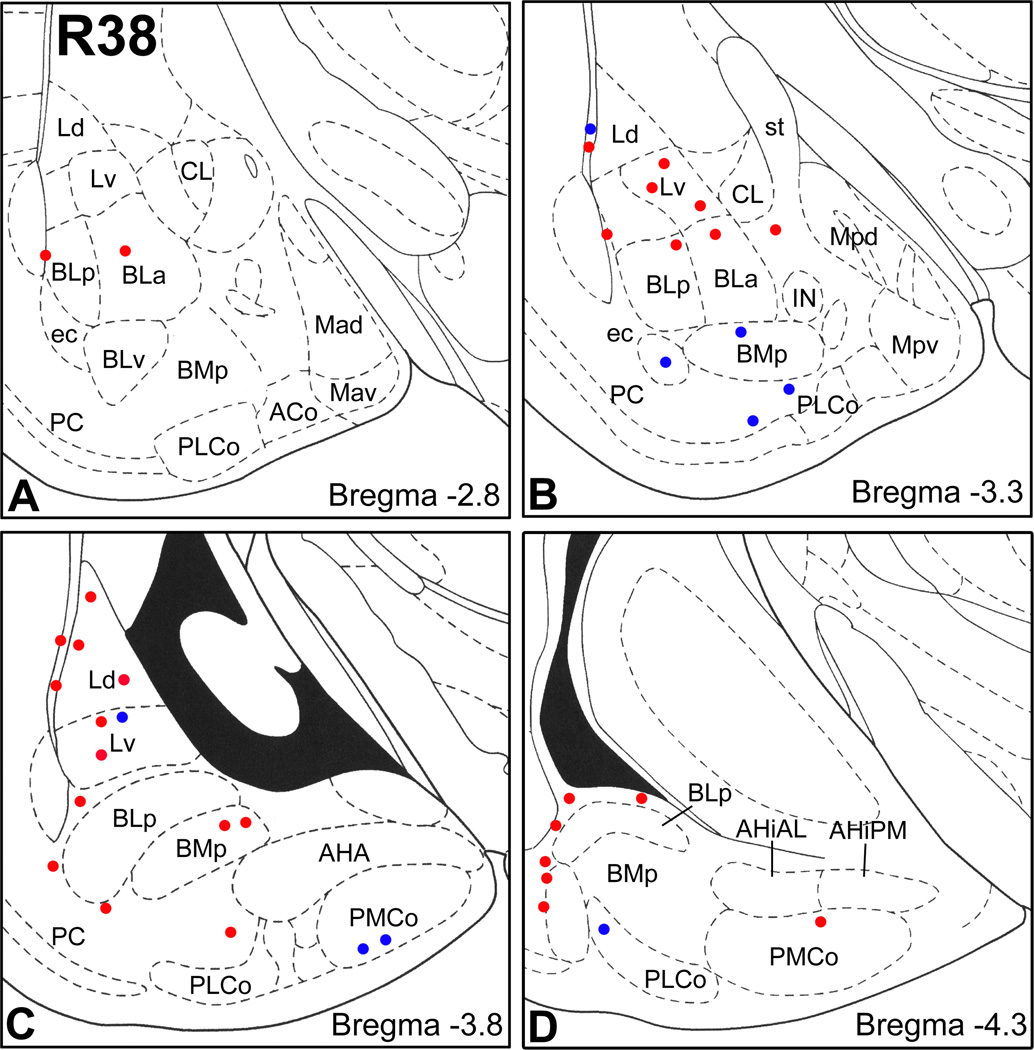

Figure 3.

Plots of FG+ retrogradely-labeled neurons at three rostrocaudal levels (Bregma −1.8, −2.8, and −3.8) in cases R13, R41L and R38. Each dot represents one cell. Sections were stained with a Nissl stain (pyronin Y) to determine nuclear borders. See Fig. 2 for most abbreviations. Additional abreveviations: ACo, anterior cortical nucleus; AHA, amygdalohippocampal area; BAOT, bed nucleus of the accessory olfactory tract; BMa, anterior basomedial nucleus; CLC, lateral capsular subdivision of the central nucleus; CM, medial central nucleus; ec, external capsule; IN, intercalated nucleus; L, lateral nucleus; Mad, anterodorsal medial nucleus; Mav, anteroventral medial nucleus; ot, optic tract; PMCo, posteromedial cortical nucleus; s, commissural portion of the stria terminalis.

Figure 2.

A) Photomicrograph of the FG injection site in case R13 in an immunoperoxidasestained section that was counterstained with pyronin Y. The injection site mainly involved the DLEA. Arrows indicate the pipette track traversing the lateral part of the ventral subiculum (VS). B) Photomicrograph of FG retrogradely-labeled neurons in the amygdala (black) at the bregma −3.1 level in case R13 in an immunoperoxidase-stained section. Abbreviations: BLa, anterior basolateral nucleus; BLp, posterior basolateral nucleus; BLv, ventral basolateral nucleus; BMp, posterior basomedial nucleus; CL, lateral central nucleus; DLEA, dorsolateral entorhinal area; Ld, dorsolateral lateral nucleus; Lv, ventromedial lateral nucleus; Mpd, posterodorsal medial nucleus; Mpv, posteroventral medial nucleus; PC, piriform cortex; PLCo, posterolateral cortical nucleus; VLEA, ventrolateral entorhinal area. Scale bars = 500 µm in A and B.

Cases with injections largely confined to the ventrolateral entorhinal area (VLEA; Fig. 1: R31, R41L, and R51) produced a characteristic pattern of retrograde labeling that was distinct from that seen with DLEA injections. In the rostral amygdala most FG+ neurons were located in the anterior cortical nucleus (ACo), anterior basomedial nucleus, and the adjacent bed nucleus of the accessory olfactory tract (Fig. 3: R41L). In the caudal amygdala there was moderate retrograde labeling in the posterolateral (PLCo) and posteromedial (PMCo) cortical nuclei, and very dense labeling in the ventromedial lateral nucleus (Lv). With injections into the VLEA that had more extensive involvement of its deeper layers (R31 and R51) there was additional retrograde labeling of neurons in the posterior basomedial nucleus. An injection into the ventromedial entorhinal area (VMEA; Fig. 1: R40L) produced virtually no FG+ neurons in the rostral two-thirds of the amygdala, but the pattern of labeling in the caudal one-third of the amygdala was similar to that seen with VLEA injections. An injection confined to the parasubiculum (PaS; Fig.1: R40R) produced almost no FG+ neurons in the rostral half of the amygdala, but in the caudal half of the amygdala there was a moderate density of labeled neurons in the ventromedial lateral nucleus, as well as in the caudal pole of BLa and the caudally-adjacent rostral portion of the posterior basolateral nucleus (BLp) at bregma levels −3.2 to −3.9.

Triple labeling experiments

All cases with injections into the DLEA, VLEA, VMEA, or parasubiculum, exhibited a subpopulation of amygdalar SOM+ neurons that was retrogradely labeled (Figs. 4–8). All were nonpyramidal neurons. Many of the FG+/SOM+ neurons also contained NPY, but only one FG+/NPY+ neuron was observed that did not also express SOM (Fig. 5D). The majority of SOM+ and SOM+/NPY+ neurons in the amygdala were not retrogradely labeled with FG. The FG+/SOM+/NPY− and FG+/SOM+/NPY+ nonpyramidal neurons (i.e., “long-range nonpyramidal” neurons [LRNP neurons]) were mainly interspersed among the far more numerous pyramidal single-labeled FG+ neurons (compare Fig. 3 with Figs. 5–8), but in the brain with the parasubiculum injection (R40R) and in one of the brains with a VLEA injection (R41L) it was not uncommon to observe isolated LRNP neurons that were located away from areas densely populated by FG+ neurons (Fig. 4D). The percentage of FG+/SOM+ neurons in the caudomedial portions of the amygdala (amygdalohippocampal area and adjacent posteromedial cortical nucleus) that also expressed NPY (11.5% [3/26]) was far less than that in the remaining corticobasolateral amygdalar nuclei (basolateral complex and the anterior and posterolateral cortical nuclei) (69.7% [83/119]); Table 1, Figs. 4–8). No PV+ or VIP+ neurons in the amygdala were labeled with FG in any of the brains.

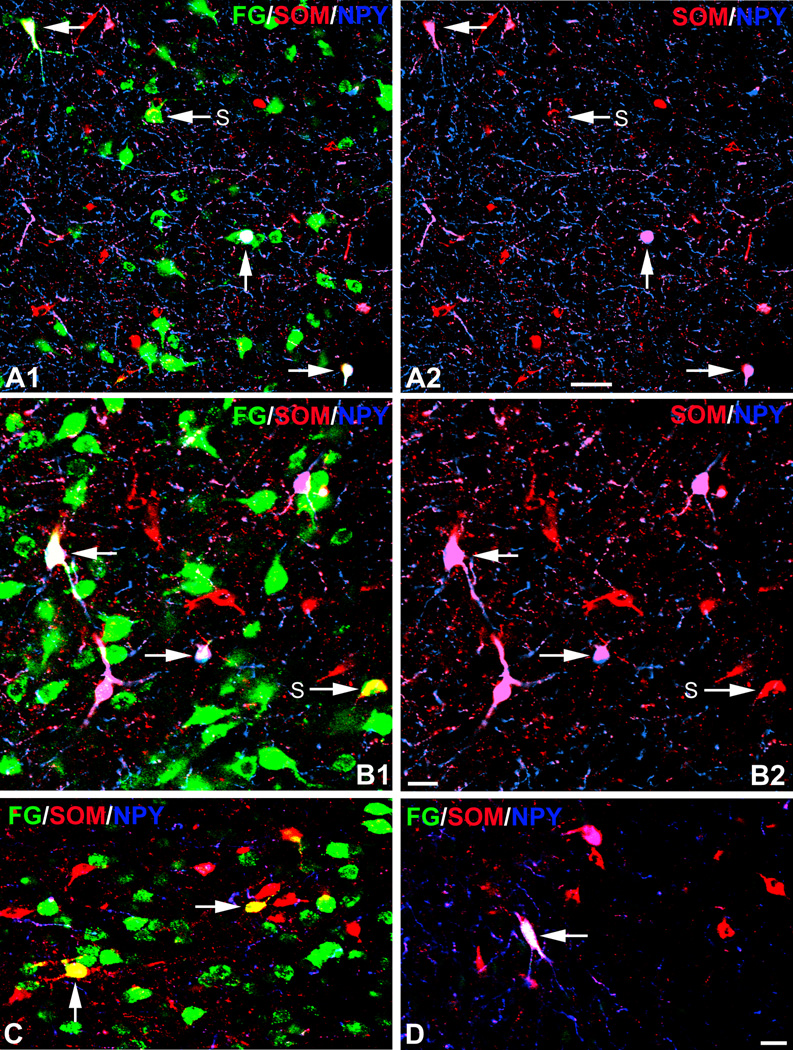

Figure 4.

Photomicrographs of FG/SOM/NPY triple labeling in the amygdala. FG is green, SOM is red, NPY is blue, FG+/SOM+ structures are yellow, FG+/SOM+/NPY+ structures are white, and FG−/SOM+/NPY+ structures in triple-labeled sections are magenta. A1) FG/SOM/NPY triple labeling in the lateral nucleus with a FG injection into the caudal DLEA (case R38). This field contains three FG+/SOM+/NPY+ triple-labeled neurons (unlabeled arrows) and one FG+/SOM+ double-labeled neuron (S). A2) The same field as A1, but with the green channel omitted. Note that the three triple-labeled neurons in A1 (unlabeled arrows) are SOM+/NPY+ (magenta) and constitute a small subpopulation of the SOM+ neurons. B1) FG/SOM/NPY triple labeling in the lateral nucleus with a FG injection into the rostral DLEA (case R13). This field contains two FG+/SOM+/NPY+ triple-labeled neurons (unlabeled arrows) and one FG+/SOM+ double-labeled neuron (S). B2) The same field as B1, but with the green channel omitted. The two triple-labeled neurons in B1 (unlabeled arrows) are SOM+/NPY+ (magenta). C) FG/SOM/NPY triple labeling in the posteromedial cortical nucleus in a case with a FG injection into the VMEA (case R40L). There are two FG+/SOM+ double-labeled neurons (arrows), but no triple-labeled neurons, in this field. D) FG/SOM/NPY triple-labeled neuron (arrow) in the external capsule bordering the posterior basolateral nucleus in a case with a FG injection into the parasubiculum (R40R). Note that this triple-labeled neuron is isolated (i.e., it is not surrounded by other green FG+ retrogradely-labeled neurons). Scale bars = 50 µm in A, 20 µm in B and D (C is the same magnification as D).

Figure 8.

Sections arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (C) depicting the locations of FG+ neurons in the amygdala co-expressing SOM and NPY (red dots) or expressing SOM but not NPY (blue dots) in cases R41R (injection: VLEA), R40L (injection: VMEA) and R40R (injection: parasubiculum). Since peroxidase preparations revealed relatively few FG+ neurons rostral to bregma −3.3 in these cases, sections at these rostral levels were not processed for FG/SOM/NPY immunohistochemistry. Each bregma level shows the locations of neurons plotted from two non-adjacent 50 µm-thick sections at this level; each dot represents one neuron. Templates are modified from the atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Figure 5.

Sections arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (F) depicting the locations of FG+ neurons in the amygdala co-expressing SOM and NPY (red dots), expressing SOM but not NPY (blue dots), or expressing NPY but not SOM (green dot) in case R13 (injection: rostral DLEA). Each bregma level shows the locations of neurons plotted from two non-adjacent 50 µm-thick sections at this level; each dot represents one neuron. Templates are modified from the atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Table 1.

Counts of FG+/SOM+/NPY+ triple-labeled neurons and FG+/SOM+ double-labeled neurons (that did not express NPY) in the caudomedial amygdala (amygdalohippocampal nucleus [AHA] and posteromedial cortical nucleus [PMCo]) versus the remaining corticobasolateral amygdalar region (lateral nucleus, basolateral nucleus, basomedial nucleus, anterior cortical nucleus, posterolateral cortical nucleus, and external capsule adjacent to the amygdala).

| Case | Area Injected |

Sections Analyzed |

AHA/PMCo | Remaining Corticobasolateral Nuclei |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FG/SOM only | FG/SOM/NPY | FG/SOM only | FG/SOM/NPY | |||

| R13 | DLEA | 13 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 27 |

| R38 | DLEA | 8 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 29 |

| R39 | DLEA/VSub | 10 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 9 |

| R40L | VMEA | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| R40R | PaS | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| R41L | VLEA | 9 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| Total | 53 | 23 | 3 | 36 | 83 | |

A rough estimate of the percentage of FG+ neurons that were LRNP neurons was made at selected levels of the amygdala in brains R13, R38, and R41L. In brain R13 there were 461 FG+ neurons at the bregma −2.8 level in the immunoperoxidase-stained section shown in Figure 3. The average number of LRNP neurons at this level was determined by counting the number of these neurons from two immunofluorescence-stained sections at this level and dividing by 2 (Fig. 5C; 15/2 = 7.5). These calculations indicate that approximately 1.6% (7.5/461) of FG+ neurons at this level were LRNP neurons (i.e., either SOM+ or SOM+/NPY+). Similar calculations were performed at the bregma −3.8 level of brains R38 and R41L with similar results (R38: 1.9% [7/376]; R41L: 2.4% [5.5/229]).

In addition, a semi-quantitative analysis of the extent of colocalization of FG, SOM and NPY was performed in the ventromedial subdivision of the lateral nucleus (Lv) in two rats that received FG injections into the DLEA (R13 and R38; Table 2). In each brain cell counts were made from 3 immunofluorescence-stained sections located between bregma levels −3.3 to −3.8. The total number of SOM+ neurons (SOM+/FG+/NPY+ triple-labeled, SOM+/FG+ double-labeled, and SOM+ single-labeled combined) in the Lv was similar in the two brains (R13 = 43; R38 = 48), but R13 had a much greater density of FG+ neurons (Fig. 3). In R13 1.16% (5/429) of FG+ neurons in Lv were LRNP neurons (SOM+/FG+/NPY+ triple-labeled or SOM+/FG+ double-labeled); these neurons constituted 11.4% (5/44) of all SOM+ neurons and 22.2% (4/18) of all NPY+ neurons (Table 2). In R38 5.91% (11/185) of FG+ neurons in Lv were LRNP neurons; these neurons constituted 22.4% (11/49) of all SOM+ neurons and 41.6% (10/24) of all NPY+ neurons (Table 2).

Table 2.

Counts of neurons in the ventromedial subdivision of the lateral amygdalar nucleus exhibiting various combinations of Fluorogold (FG), somatostatin (SOM), and NPY immunoreactivity in cases R13 and R38. In each brain cell counts were made from 3 sections located between bregma levels −3.3 to −3.8.

| Brain | FG only (No SOM or NPY) |

FG/SOM only (No NPY) |

FG/NPY only (No SOM) |

FG/SOM/NPY | SOM only (No FG or NPY) |

NPY only (No FG or SOM) |

SOM/NPY only (No FG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R13 | 424 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 25 | 0 | 14 |

| R38 | 175 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 24 | 0 | 14 |

| Total | 599 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 49 | 0 | 28 |

Three colchicine-injected brains were examined to determine if FG+ neurons or FG+/SOM+ neurons were also immunoreactive for the m2 muscarinic cholinergic receptor (M2R) or GAD. As in the other brains used in this study, most FG+ neurons and FG+/SOM+ neurons in these two brains were located in the basolateral amygdala. In each case cell counts were made in these nuclei in the two brains with the most robust immunoreactivity for the markers investigated. In two brains (R54 and R31) triple-labeled for FG/SOM/M2R, cell counts pooled from both brains revealed that 51.5% (17/33) of amygdalar FG+/SOM+ neurons also expressed M2R (Fig. 9). No FG+/M2R+ neurons were observed that did not also express SOM. In two brains triple-labeled for FG/SOM/GAD (R51 and R54), cell counts pooled from both brains revealed that 62.2% (23/37) of amygdalar FG+/SOM+ neurons also expressed GAD (Fig. 10). In addition, one neuron in the lateral nucleus in brain 54 (Fig. 10B) and three neurons in the lateral nucleus in brain R51 were FG+/GAD+, but SOM-negative. In both the FG/SOM/GAD and FG/SOM/M2R experiments both double-labeled and triple-labeled neurons were interspersed among each other, with no anatomical segregation.

Figure 9.

Photomicrographs showing M2R-ir in a subpopulation of amygdalar SOM+ neurons that are retrogradely labeled by FG in a case with a large injection that involved VLEA, VMEA and the ventral subiculum (R54). A1) FG/SOM/M2R triple labeling in the lateral nucleus (FG is green, SOM is red, M2R is blue). A FG+/SOM+/M2R+ triple-labeled neuron (arrow) is white. A2) The same field as A1 showing only SOM-ir with the red channel. A3) The same field as A1 showing only M2R-ir with the blue channel. B1) FG/SOM/M2R triple labeling in the posteromedial cortical nucleus (FG is green, SOM is red, M2R is blue). A FG+/SOM+/M2R+ triple-labeled neuron (unlabeled arrow) is white. Two M2R-negative FG+/SOM+ neurons (S) are yellow. B2) The same field as B1 showing only SOM-ir with the red channel. B3) The same field as B1 showing only M2R-ir with the blue channel. Scale bar = 20 µm in B (A is at the same magnification).

Figure 10.

Photomicrographs of FG-labeled neurons in the amygdala that are SOM+/GAD+. A1) FG/SOM/GAD triple labeling in case R51 (FG is green, SOM is red, GAD is blue). A FG+/SOM+/GAD+ triple-labeled neuron in the external capsule (arrow) is white. A FG-negative SOM+/GAD+ double-labeled neuron in the adjacent posterior basolateral nucleus is magenta (arrowhead). A2) The same field as A1 showing only SOM-ir with the red channel. A3) The same field as A1 showing only GAD-ir with the blue channel. B1) FG/SOM/GAD triple labeling in case R54 (FG is green, SOM is red, GAD is blue). Two FG+/SOM+/GAD+ triple-labeled neurons in the lateral nucleus (arrows) are white. This field also contains a GAD+ neuron with very low levels of FG (arrowhead). B2) The same field as B1 showing only the SOM-ir with the red channel. B3) The same field as B1 showing only the GAD-ir with the blue channel. Scale bar = 20 µm in A (B is at the same magnification).

FG injections into other cortical regions

A limited number of injections were made into other cortical regions to determine if subpopulations of amygdalar SOM+, NPY+, PV+, or VIP+ neurons had projections to the medial prefrontal, lateral prefrontal, or insular cortices (cases R11, R10, and R22; Fig. 1). Although there was extensive FG retrograde labeling that was mainly confined to the basolateral nuclear complex in all 3 brains, no FG+ neurons expressed SOM, NPY, PV, or VIP in these brains, with the exception of one FG+/SOM+ neuron that was seen along the BLa/BMp border in the brain with the insular injection.

Discussion

Pattern of retrograde labeling in the amygdala

The overall pattern of retrograde labeling seen in the amygdala in the present study was consistent with the findings of previous tract tracing studies of amygdalocortical projections (for a review see Pitkanen, 2000). The novel finding of the present study is that a small number of SOM+ nonpyramidal neurons, located mainly in the basolateral and cortical nuclei of the amygdala, take part in amygdalo-entorhinal and amygdalo-parasubicular projections, but not projections to the prefrontal cortex. Although there have been many studies of amygdaloentorhinal projections in the rat using anterograde tract tracing techniques, to the authors’ knowledge there have been only two previous studies of these projections using retrograde tract tracing techniques (Beckstead, 1978; Majak and Pitkanen, 2003). Beckstead’s study did not focus on amygdalar projections and used a retrograde tract tracing technique that was much less sensitive than the FG technique used in the present investigation. As a result the few amygdalar sections depicted only contained 3–8 retrogradely labeled neurons per section (Beckstead, 1978). However, as in the present study, injections into the lateral entorhinal cortex resulted in retrogradely labeled neurons in both the basolateral and corticomedial nuclei, with the densest labeling in the lateral nucleus. Our findings demonstrate that these amygdalo-entorhinal projections actually involve large numbers of neurons in these nuclei (Fig. 3), and that the great majority of these projection neurons appear to correspond to pyramidal neurons rather than nonpyramidal neurons. Likewise, a study focusing on the lateral nucleus revealed that entorhinal injections of FG retrogradely labeled large numbers of neurons in that nucleus (Majak and Pitkanen, 2003).

In the present investigation the two main entorhinal targets of amygdalar projections were the DLEA and VLEA (which correspond, respectively, to the dorsal intermediate [DIE] and ventral intermediate [VIE] areas of Insausti et al., 1997). The pattern of retrograde labeling in the amygdala produced by injections of FG into each area were distinct. Injections into the DLEA produced retrograde labeling in all amygdalar nuclei with the exception of the central nucleus, intercalated nuclei, posterodorsal medial nucleus, and the rostral pole of the anterior basolateral nucleus. The density of labeled neurons was much greater with injections into the rostral DLEA (R13) compared to the caudal DLEA (R38). In general these findings are consistent with anterograde tract tracing studies in the rat of projections to the DLEA from the basolateral nuclei (Pikkarainen et al., 1999; Petrovich et al., 1996), cortical nuclei (Krettek and Price, 1977; Luskin and Price, 1983; Canteras et al., 1992; Kemppainen et al., 2002), medial nucleus (Canteras et al., 1995), and amygdalohippocampal area (Kemppainen et al., 2002).

In contrast to DLEA injections, injections into the VLEA produced retrograde labeling that was mainly confined to the caudal lateral nucleus, anterior and posterior basomedial nuclei, and the cortical nuclei. These findings are consistent with anterograde tract tracing studies of these nuclei (Krettek and Price, 1977; Luskin and Price, 1983; Canteras et al., 1992; Petrovich et al., 1996; Pikkarainen et al., 1999; Kemppainen et al., 2002). Our finding of labeled neurons in the caudal part of the ventromedial lateral nucleus and adjacent portions of the basolateral nucleus with a parasubicular injection agrees with a study that used anterograde and retrograde tract tracing techniques to study this projection (van Groen and Wyss, 1990).

Long-range nonpyramidal neurons (LRNP neurons) in the corticobasolateral amygdala

Virtually all of the LRNP neurons in the amygdala that had projections to the entorhinal cortex or parasubiculum were seen in the cortical nuclei, basolateral nuclei (consisting of the basolateral, lateral, and basomedial nuclei), and the amygdalohippocampal area. These nuclei, which have been termed the corticobasolateral nuclear complex (CBL) of the amygdala, contain neurons that resemble those of the cerebral cortex (McDonald, 1992a; McDonald, 2003; Sah et al., 2003). Dual-labeling immunohistochemical studies in the basolateral amygdala suggest that the CBL contains at least four distinct subpopulations of GABAergic nonpyramidal neurons that can be distinguished on the basis of their content of calcium-binding proteins and peptides. The three subpopulations investigated in the present study (SOM+, PV+, VIP+) collectively represent the great majority of nonpyramidal neurons in the CBL. The fourth subpopulation, consisting of large CCK+ neurons, only constitutes about 7% of nonpyramidal neurons (Mascagni and McDonald, 2003).

The present study indicates that a small number of the SOM+ and SOM+/NPY+ nonpyramidal neurons in the CBL and adjacent external capsule, but not the PV+ or VIP subpopulations, are LRNP neurons that project to the entorhinal cortex and parasubiculum. These results are consistent with the findings of a previous study which found that a small number of nonpyramidal NPY+ neurons in the lateral nucleus were retrogradely-labeled by injections of Fast Blue into the entorhinal cortex (Köhler et al., 1986). These investigators mainly focused their attention on interconnections of the parahippocampal region in horizontal sections that did not include most portions of the amygdala, and they did not examine amygdalar regions ventral to the lateral nucleus. It is also of interest that a small number of nonpyramidal SOM+ LRNP neurons in the basomedial nucleus were retrogradely labeled by injections of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) into the medial preoptic-hypothalamic region (McDonald, 1987), and a small number of nonpyramidal SOM+ and SOM+/NPY+ LRNP neurons in the basolateral, basomedial, and cortical nuclei were labeled by injections of FG into the basal forebrain (McDonald et al., 2012). Cell counts in the latter study indicated that about 13% of CBL neurons projecting to the basal forebrain were SOM+ LRNP neurons, and these neurons were located mainly in the basomedial nucleus, cortical nuclei, and the external capsule. The present study revealed that only about 1–5% of CBL neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex were SOM+ LRNP neurons, and these neurons were located mainly in the lateral nucleus and the external capsule. Additional counts in the lateral nucleus in the present study indicated that LRNP neurons projecting to the rostromedial part of the DLEA (case R13) constituted 11% of SOM+ neurons and 22% of NPY+ neurons whereas LRNP neurons projecting to the caudal pole of the DLEA (case R38) constituted 22% of SOM+ neurons and 41% of NPY+ neurons. Based on these results, if different subpopulations of LRNP neurons project to distinct portions of the DLEA, than at least 30% of SOM+ neurons and 60% of NPY+ neurons could be LRNP neurons. Since the FG injections in these two DLEA cases taken together involve only a portion of the total extent of the entorhinal cortex, it may be that the majority of both SOM+ and NPY+ neurons in the lateral nucleus are LRNP neurons. Alternatively, if these neurons have axons that branch extensively to innervate widespread regions of the entorhinal cortex, the percentage of SOM+ and NPY+ neurons that are LRNP neurons may be less.

Previous studies have found that about 80% of SOM+ neurons in the lateral nucleus are GABA+, even when colchicine is injected intracerebroventricularly to increase somatic levels of GABA (McDonald and Pearson, 1989; McDonald and Mascagni, 2002). In the present study, which utilized colchicine injections to increase GAD levels, 62% of SOM+ LRNP neurons in the lateral nucleus projecting to the entorhinal cortex were GAD+. Similarly, 53% of SOM+ LRNP neurons in the basomedial nucleus projecting to the basal forebrain were GAD+ (McDonald et al., 2012). Although these results might indicate that there are two distinct subpopulations of amygdalar SOM+ LRNP neurons, other evidence suggests that the GAD-negative LRNP neurons may merely have levels of GAD that are below the threshold of immunohistochemical detection. Thus, although the cell bodies of hippocamposeptal LRNP neurons in the rat were judged to be GABA-negative, it was noticed that they all appeared to exhibit very faint staining in immunoperoxidase preparations (Tóth and Freund, 1992). Subsequent anterograde tract tracing studies revealed that the axon terminals of these hippocamposeptal neurons were indeed GABA-positive (Tóth et al., 1993). These observations are consistent were numerous studies which have shown that GABAergic neurons with distant projections typically have very low levels of GABA/GAD in their somata due to rapid transport of these neurochemicals to the axon terminals (for a discussion of this issue see Tóth and Freund, 1992). It therefore seems likely that the great majority of amygdalar LRNP neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex and basal forebrain may be GABAergic, but that many have very low levels of somatic GAD. Future retrograde tract tracing studies, perhaps using GAD-green fluorescent protein knock-in mice as experimental animals to better visualize all GABAergic neurons (Tamamaki et al., 2003), will be required to resolve this issue.

Half of the SOM+ LRNP neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex in the present study expressed immunoreactivity for the m2 muscarinic cholinergic receptor (M2R). This is not surprising since all SOM+/NPY+ neurons, but not other nonpyramidal neuronal subpopulations, in the basolateral amygdala and external capsule are M2R+ (McDonald and Masacagni, 2011). Although this finding suggests that the activity of SOM+/NPY+ LRNP neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex is modulated by acetylcholine, it is not clear to what extent this modulation is due to release of acetylcholine in the amygdala, affecting the somatodendritic domain of these neurons, and/or is due to release of acetylcholine in the entorhinal cortex and modulating the long-range terminal axons of these neurons. The latter mechanism has been demonstrated for perirhinal cortical LRNP neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex, where there is presynaptic inhibition of GABA release mediated by M2Rs (Apergis-Shoute et al., 2007).

Long-range nonpyramidal neurons in the external capsule

Many of the SOM+ and SOM+/NPY+ LRNP neurons labeled by parahippocampal injections of FG were found in or adjacent to the white matter of the ventral portion of the external capsule that separates the amygdala from the endopiriform nucleus and piriform cortex. These LRNP neurons in the external capsule also project to the basal forebrain (McDonald et al., 2012). Similarly, there is an extensive array of GABAergic LRNP neurons in or adjacent to the white matter of the entire neocortex that project to both neighboring as well as distant areas of the cortex (Tomioka et al., 2005; Tomioka and Rockland, 2007; Clancy et al., 2009). Like the LRNP neurons of the amygdala, virtually all of the neocortical LRNP neurons are SOM+ and also express NPY (Tomioka et al., 2005; Tomioka and Rockland, 2007). Thus, the SOM+ LRNP neurons seen in the region of the ventral portion of the external capsule in the present study appear to be part of this white matter-associated system of neurons, but they also have projections to the parahippocampal region and basal forebrain. In addition to their long-range projections, the LRNP neurons associated with the white matter of the neocortex have reciprocal connections with the area of neocortex that overlies them (Meyer et al., 1991; Shering and Lowenstein, 1994; Clancy et al., 2001). This suggests that the SOM+ LRNP neurons seen in the region of the ventral portion of the external capsule in the present study may also have reciprocal connections with the adjacent piriform cortex or the cortex-like CBL nuclei of the amygdala and/or endopiriform nucleus.

Functional Considerations

All major portions of the medial temporal lobe memory system are interconnected by various populations of GABAergic LRNP neurons, including many that are SOM+ (see Jinno, 2009 for a review). Thus, LRNP neurons have been shown to contribute to the following projections: (1) neocortex to perirhinal cortex (Pinto et al., 2008); (2) perirhinal cortex to entorhinal cortex (Pinto et al., 2008; Apergis-Shoute et al., 2007); (3) entorhinal cortex to hippocampus (Germroth et al., 1989; Melzer et al., 2012), (4) hippocampus to subicular and retrosplenial regions (Jinno et al., 2007; Miyashita and Rockland, 2007); and (5) subicular region to entorhinal cortex (Van Haeften et al., 1997). The finding of the present study that GABAergic LRNP neurons in the basolateral amygdala project to the entorhinal cortex and parasubiculum indicates that this temporal lobe GABAergic “supernetwork” (Buzsaki and Chrobak, 1995) includes the basolateral amygdala. In fact, recent studies in our lab have shown that these connections are reciprocal; injections of FG into the basolateral amygdala label SOM+/GABA+ LRNP neurons in the entorhinal cortex (McDonald and Zaric, 2014). Some SOM+ LRNP neurons in the hippocampus have axons that branch to innervate both the medial septal area of the basal forebrain and the adjacent subiculum (Jinno et al., 2007). Since SOM+ LRNP neurons in the basolateral amygdala and adjacent external capsule are retrogradely-labeled by FG injections into the basal forebrain and entorhinal cortex, it will be of interest to determine if the axons of individual amygdalar LRNP neurons can coordinate activity in these two regions by sending axonal branches to both regions. In addition, it remains to be determined if SOM+ LRNPs participate in amygdalar projections to the ventral subiculum and adjacent CA1 (Pitkanen, 2000).

Only a small number of LRNPs are involved in most of the interconnections of the temporal lobe GABAergic supernetwork. In the present study we found that only 1–5% of basolateral amygdalar projection neurons were LRNP neurons. This percentage is very similar to that exhibited by the perirhinal to entorhinal cortex projection where 3% of perirhinal projection neurons were LRNP neurons (Apergis-Shoute et al., 2007). However, electron microscopic studies found that 12% of the axons involved in the latter projection formed symmetrical synapses typical of inhibitory inputs, which suggests that these perirhinal LRNP neurons have axons that branch extensively (Pinto et al., 2008). It will be of interest to perform similar quantitative ultrastructural analyses of basolateral amygdalar inputs to the rat entorhinal cortex, as well as electrophysiological studies of these projections, to assess their ability to inhibit entorhinal activity. An anterograde tract tracing study in monkey found that only one out of 80 axon terminals in the entorhinal cortex labeled by a PHAL injection into the basolateral amygdala formed a symmetrical (inhibitory) synapse (Pitkanen et al., 2002).

Electrophysiological studies have shown electrical stimulation of the basolateral nuclei produces an initial excitation, followed by a suppression of firing, in the great majority of entorhinal and subicular neurons (Finch et al. 1986; Colino and de Molina, 1986a). Colino and de Molina (1986b) reported that 9% of entorhinal and subicular neurons exhibited an initial inhibition, but suggested that this response could be mediated by an interneuron.

It will also be important to determine the neuronal targets of amygdalar LRNP inputs to the entorhinal cortex. Either pyramidal neurons (Pinto et al., 2008; Jinno et al., 2007) or nonpyramidal neurons (Van Haeften et al., 1997; Melzer et al., 2012) have been identified as targets of LRNP neurons in different hippocampal/parahippocampal circuits. In the basolateral amygdala the local targets of SOM+ neurons are the distal dendrites and spines of pyramidal cells and the dendrites and cell bodies of interneurons (Muller et al., 2007).

Like GABAergic LRNP neurons in hippocampal/parahippocampal regions, the basolateral LRNP neurons that project to the entorhinal cortex are most likely involved in synchronizing oscillatory activity between the two regions (Buzsaki and Chrobak, 1995; Jinno, 2009; Caputi et al., 2013). It is of interest in this regard that the axons of hippocampal GABAergic LRNP neurons have a larger diameter and thicker myelin sheath than pyramidal cell axons, which suggests that these faster inhibitory inputs may reset the excitability and oscillatory phase of their targets just before the slower excitatory pyramidal cell inputs arrive (Jinno et al., 2007). Thus it is possible that basolateral amygdalar GABAergic LRNP neurons projecting to the entorhinal cortex are involved in the synchronization of a variety of oscillations, including delta, theta, gamma, and slow oscillations between the basolateral amygdala and hippocampal/parahippocampal region (Paré and Gaudreau, 1996; Paré et al., 2002; Bauer et al., 2007). These oscillations could entrain synchronous firing of amygdalar and entorhinal pyramidal neurons, thus facilitating functional interactions between them including synaptic plasticity involved in mnemonic function. In fact, various aspects of fear learning involve synchronization of theta activity in the lateral amygdalar nucleus and dorsal hippocampus (Seidenbacher et al. 2003; Pape et al., 2005; Narayanan et al., 2007a, b). Since the dorsal hippocampus and lateral nucleus are not directly interconnected, the synchronization of theta activity between these structures may involve a relay in the entorhinal cortex (Mizuseki et al., 2009). Connections between the basolateral amygdala, hippocampal region, and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are critical for contextual regulation of fear learning and extinction (Orsini et al., 2011). Because coupled theta activity increases in all three regions during fear retrieval (Lesting et al., 2011), it is surprising that no LRNP neurons were observed in the basolateral amygdala with FG injections into the mPFC in the present study. It is possible that synchronization between the basolateral amygdala and mPFC depends on a mechanism that does not involve LRNPs, or depends on a relay in the rhinal cortices. However, to the authors’ knowledge there have been no studies that have investigated whether connections between the mPFC and hippocampal/parahippocampal regions involve GABAergic LRNP neurons.

There is substantial evidence that SOM+ neurons in the basolateral amygdala are involved in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Somatostatin has been shown to have anti-convulsant effects in the amygdala and hippocampus (Mazarati and Telegdy, 1992; Vezzani and Hoyer, 1999), and there is a selective loss of SOM+ neurons in the basolateral amygdala in animal models of TLE (Tuunanen et al., 1997). It has been suggested that the loss of inhibitory inputs to basolateral amygalar pyramidal cell dendrites provided by GABAergic SOM+ interneurons in TLE produces hyperexcitability in local pyramidal cells (Tuunanen et al., 1997; Muller et al., 2007). The results of the present study suggest that the loss of inhibitory inputs to the entorhinal cortex and parasubiculum prvided by amygdalar SOM+ LRNP neurons might alter inter-regional spread of seizure activity.

Figure 6.

Sections arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (F) depicting the locations of FG+ neurons in the amygdala co-expressing SOM and NPY (red dots) or expressing SOM but not NPY (blue dots) in case R39 (injection: DLEA/VSub). Each bregma level shows the locations of neurons plotted from two non-adjacent 50 µm-thick sections at this level with the exception of bregma levels −1.8 and −2.3 where only one section was available for analysis; each dot represents one neuron. Templates are modified from the atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Figure 7.

Sections arranged from rostral (A) to caudal (D) depicting the locations of FG+ neurons in the amygdala co-expressing SOM and NPY (red dots) or expressing SOM but not NPY (blue dots) in case R38 (injection: caudal DLEA). Since peroxidase preparations revealed relatively few FG+ neurons rostral to bregma −2.8 in this case, sections at these rostral levels were not processed for FG/SOM/NPY immunohistochemistry. Each bregma level shows the locations of neurons plotted from two non-adjacent 50 µm-thick sections at this level; each dot represents one neuron. Templates are modified from the atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997).

Highlights.

Most amygdalar neurons labeled by Fluorogold injections into the entorhinal cortex are located in the basolateral amygdala

About 1–5% of these amygdalar projection neurons are nonpyramidal neurons containing somatostatin and/or neuropeptide Y

Slightly more than half of these long-range nonpyramidal neurons (LRNP neurons) express GAD or the m2 muscarinic receptor

No LRNP neurons with entorhinal projections express parvalbumin or vasoactive intestinal peptide

No amygdalar LRNP neurons project to the prefrontal cortex

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the generous donation of the guinea pig FG antibody obtained from Dr. Lothar Jennes (University of Kentucky) and the mouse SOM antibody obtained from Dr. Alison Buchan (University of British Columbia). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-DA027305.

Abbreviations used in the text and figures

- ACo

anterior cortical nucleus

- AHA

amygdalohippocampal area

- AID

dorsal agranular insular cortex

- AIP

posterior agranular insular cortex

- AIV

ventral agranular insular cortex;

- BAOT

bed nucleus of the accessory lateral olfactory tract

- BLa

anterior basolateral nucleus

- BLp

posterior basolateral nucleus

- BLv

ventral basolateral nucleus

- BMa

anterior basomedial nucleus

- BMp

posterior basomedial nucleus

- CBL

corticobasolateral amygdala

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CL

lateral central nucleus

- CLC

lateral capsular central nucleus

- CM

medial central nucleus

- DI

dysgranular insular cortex

- DLEA

dorsolateral entorhinal area

- ec

external capsule

- FG

Fluorogold

- GAD

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- GI

granular insular cortex

- IL

infralimbic cortex

- IN

intercalated nucleus

- L

lateral nucleus

- Ld

dorsolateral lateral nucleus

- Lv

ventromedial lateral nucleus

- LRNP

long-range nonpyramidal

- M2R

m2 muscarinic receptor

- Mad

anterodorsal medial nucleus

- Mav

anteroventral medial nucleus

- Mpd

posterodorsal medial nucleus

- Mpv

posteroventral medial nucleus

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- ot

optic tract

- PaS

parasubiculum

- PC

piriform cortex

- PL

prelimbic cortex

- PLCo

posterolateral cortical nucleus

- PMCo

posteromedial cortical nucleus

- PV

parvalbumin

- s

commissural part of the stria terminalis

- S2

secondary somatosensory cortex

- SOM

somatostatin

- st

stria terminalis

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

- VLEA

ventrolateral entorhinal area

- VMEA

ventromedial entorhinal area

- VSub or VS

ventral subiculum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Apergis-Schoute J, Pinto A, Paré D. Muscarinic control of long-range GABAergic inhibition within the rhinal cortices. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4061–4071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0068-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer EP, Paz R, Paré D. Gamma oscillations coordinate amygdalo-rhinal interactions during learning. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9369–9379. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2153-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RM. Afferent connections of the entorhinal area in the rat as demonstrated by retrograde cell-labeling with horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. 1978;152:249–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Chrobak JJ. Temporal structure in spatially organized neuronal ensembles: a role for interneuronal networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:504–510. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Connections of the posterior nucleus of the amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:143–179. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the medial nucleus of the amygdala: a PHAL study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1995;360:213–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi A, Melzer S, Michael M, Monyer H. The long and short of GABAergic neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsen J, Heimer L. The basolateral amygdaloid complex as a cortical-like structure. Brain Res. 1988;441:377–380. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Silva-Filho M, Friedlander MJ. Structure and projections of white matter neurons in the postnatal rat visual cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2001;434:233–252. doi: 10.1002/cne.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy B, Teague-Ross TJ, Nagarajan R. Cross-species analyses of the cortical GABAergic and subplate neural populations. Front Neuroanat. 2009;3:20. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.020.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Fernández de Molina A. Electrical activity generated in subicular and entorhinal cortices after electrical stimulation of the lateral and basolateral amygdala of the rat. Neuroscience. 1986a;19:573–580. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colino A, Fernández de Molina A. Inhibitory response in entorhinal and subicular cortices after electrical stimulation of the lateral and basolateral amygdala of the rat. Brain Res. 1986b;378:416–419. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch DM, Wong EE, Derian EL, Chen XH, Nowlin-Finch NL, Brothers LA. Neurophysiology of limbic system pathways in the rat: projections from the amygdala to the entorhinal cortex. Brain Res. 1986;370:273–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller TA, Russchen FT, Price JL. Sources of presumptive glutamergic/aspartergic afferents to the rat ventral striatopallidal region. J Comp Neurol. 1987;258:317–338. doi: 10.1002/cne.902580302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germroth P, Schwerdtfeger WK, Buhl EH. GABAergic neurons in the entorhinal cortex project to the hippocampus. Brain Res. 1989;494:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock MB. Two-color immunoperoxidase staining: visualization of anatomic relationships between immunoreactive neural elements. Am J Anat. 1986;175:343–352. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001750216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insausti R, Herrero MT, Witter MP. Entorhinal cortex of the rat: cytoarchitectonic subdivisions and the origin and distribution of cortical efferents. Hippocampus. 1997;7:146–183. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:2<146::AID-HIPO4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno S, Klausberger T, Marton LF, Dalezios Y, Roberts JD, Fuentealba P, Bushong EA, Henze D, Buzsáki G, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity in GABAergic long-range projections from the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8790–8804. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1847-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinno S. Structural organization of long-range GABAergic projection system of the hippocampus. Front Neuroanat. 2009;3:13. doi: 10.3389/neuro.05.013.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen S, Pitkänen A. Distribution of parvalbumin, calretinin, and calbindin-D(28k) immunoreactivity in the rat amygdaloid complex and colocalization with gamma-aminobutyric acid. J Comp Neurol. 2000;426:441–467. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001023)426:3<441::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen S, Jolkkonen E, Pitkänen A. Projections from the posterior cortical nucleus of the amygdala to the hippocampal formation and parahippocampal region in rat. Hippocampus. 2002;12:735–755. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Smialowska M, Eriksson LG, Chanpalay V, Davies S. Origin of the neuropeptide Y innervation of the rat retrohippocampal region. Neurosci Lett. 1986;65:287–292. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krettek JE, Price JL. Projections from the amygdaloid complex and adjacent olfactory structures to the entorhinal cortex and to the subiculum in the rat and cat. J Comp Neurol. 1977;172:723–752. doi: 10.1002/cne.901720409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesting J, Narayanan RT, Kluge C, Sangha S, Seidenbecher T, Pape HC. Patterns of coupled theta activity in amygdala-hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits during fear extinction. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB, Price JL. The topographic organization of associational fibers of the olfactory system in the rat, including centrifugal fibers to the olfactory bulb. J Comp Neurol. 1983;216:264–291. doi: 10.1002/cne.902160305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majak K, Pitkänen A. Activation of the amygdalo-entorhinal pathway in fear-conditioning in rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1652–1659. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascagni F, McDonald AJ. Immunohistochemical characterization of cholecystokinin containing neurons in the rat basolateral amygdala. Brain Res. 2003;976:171–184. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascagni F, Muly EC, Rainnie DG, McDonald AJ. Immunohistochemical characterization of parvalbumin-containing interneurons in the monkey basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1541–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati AM, Telegdy G. Effects of somatostatin and anti-somatostatin serum on picrotoxin-kindled seizures. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:793–797. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90043-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Cytoarchitecture of the central amygdaloid nucleus of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1982;208:401–418. doi: 10.1002/cne.902080409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Morphology of peptide-containing neurons in the rat basolateral amygdaloid nucleus. Brain Res. 1985;338:186–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Somatostatinergic projections from the amygdala to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and medial preoptic-hypothalamic region. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;75:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Coexistence of somatostatin with neuropeptide Y, but not with cholecystokinin or vasoactive intestinal peptide, in neurons of the rat amygdala. Brain Res. 1989;500:37–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Cell types and intrinsic connections of the amygdala. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1992a. pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Projection neurons of the basolateral amygdala: a correlative Golgi and retrograde tract tracing study. Brain Res Bull. 1992b;28:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90177-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Glutamate and aspartate immunoreactive neurons of the rat basolateral amygdala: colocalization of excitatory amino acids and projections to the limbic circuit. J Comp Neurol. 1996;365:367–379. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960212)365:3<367::AID-CNE3>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ. Is there an amygdala and how far does it extend? : An anatomical perspective. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;985:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Pearson JC. Coexistence of GABA and peptide immunoreactivity in non-pyramidal neurons of the basolateral amygdala. Neurosci Lett. 1989;100:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90659-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Augustine JR. Localization of GABA-like immunoreactivity in the monkey amygdala. Neuroscience. 1993;52:281–294. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90156-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Augustine JR. Neuropeptide Y and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in neurons of the monkey amygdala. Neuroscience. 1995;66:959–982. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00629-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Betette RL. Parvalbumin-containing neurons in the rat basolateral amygdala: morphology and co-localization of calbindin-D(28k) Neuroscience. 2001;102:413–425. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Colocalization of calcium-binding proteins and gamma-aminobutyric acid in neurons of the rat basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2001;105:681–693. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Immunohistochemical characterization of somatostatin containing interneurons in the rat basolateral amygdala. Brain Res. 2002;943:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Neuronal localization of 5-HT type 2A receptor immunoreactivity in the rat basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2007;146:306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Neuronal localization of m1 muscarinic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat basolateral amygdala. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;215:37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0272-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F. Neuronal localization of m2 muscarinic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat amygdala. Neuroscience. 2011;196:49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Zaric V. Subpopulations of somatostatin-immunoreactive non-pyramidal neurons in the amygdala and adjacent external capsule project to the basal forebrain: evidence for the existence of GABAergic projection neurons in the cortical nuclei and basolateral nuclear complex. Front Neural Circuits. 2012 Jul 24;6:46. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2012.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald AJ, Zaric V. Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience, 2014; 2014. Long-range GABAergic projection neurons participate in reciprocal interconnections between the rat basolateral amygdala and the parahippocampal region, but not the prefrontal cortex. Program No.754.06, 2014. Online. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CK, McGaugh JL, Williams CL. Interacting brain systems modulate memory consolidation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1750–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer S, Michael M, Caputi A, Eliava M, Fuchs EC, Whittington MA, Monyer H. Long-range-projecting GABAergic neurons modulate inhibition in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Science. 2012;335:1506–1510. doi: 10.1126/science.1217139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer G, Gonzalez-Hernandez T, Galindo-Mireles D, Castañeyra-Perdomo A, Ferres-Torres R. The efferent projections of neurons in the white matter of different cortical areas of the adult rat. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1991;184:99–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01744266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millhouse OE, DeOlmos J. Neuronal configurations in lateral and basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 1983;10:1269–1300. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Rockland KS. GABAergic projections from the hippocampus to the retrosplenial cortex in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1193–1204. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuseki K, Sirota A, Pastalkova E, Buzsáki G. Theta oscillations provide temporal windows for local circuit computation in the entorhinal-hippocampal loop. Neuron. 2009;64:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller JF, Mascagni F, McDonald AJ. Postsynaptic targets of somatostatin-containing interneurons in the rat basolateral amygdala. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007;500:513–529. doi: 10.1002/cne.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan RT, Seidenbecher T, Sangha S, Stork O, Pape HC. Theta resynchronization during reconsolidation of remote contextual fear memory. Neuroreport. 2007a;18:1107–1111. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282004992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan RT, Seidenbecher T, Kluge C, Bergado J, Stork O, Pape HC. Dissociated theta phase synchronization in amygdalo-hippocampal circuits during various stages of fear memory. Eur J Neurosci. 2007b;25:1823–1831. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini CA1, Kim JH, Knapska E, Maren S. Hippocampal and prefrontal projections to the basal amygdala mediate contextual regulation of fear after extinction. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17269–17277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4095-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC, Narayanan RT, Smid J, Stork O, Seidenbecher T. Theta activity in neurons and networks of the amygdala related to long-term fear memory. Hippocampus. 2005;15:874–880. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Gaudreau H. Projection cells and interneurons of the lateral and basolateral amygdala: distinct firing patterns and differential relation to theta and delta rhythms in conscious cats. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3334–3350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03334.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré D, Collins DR, Pelletier JG. Amygdala oscillations and the consolidation of emotional memories. Trends Cogn Sci. 2002;6:306–314. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01924-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovich GD, Risold PY, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the basomedial nucleus of the amygdala: a PHAL study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;374:387–420. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961021)374:3<387::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikkarainen M1, Rönkkö S, Savander V, Insausti R, Pitkänen A. Projections from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala to the hippocampal formation in rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403:229–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A, Sesack SR. Ultrastructural analysis of prefrontal cortical inputs to the rat amygdala: spatial relationships to presumed dopamine axons and D1 and D2 receptors. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:159–175. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A. Connectivity of the rat amygdala. In: Aggleton JP, editor. The Amygdala. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 31–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Kelly JL, Amaral DG. Projections from the lateral, basal, and accessory basal nuclei of the amygdala to the entorhinal cortex in the macaque monkey. Hippocampus. 2002;12:186–205. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesler R1, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL. Basolateral amygdala lesions block the memory-enhancing effect of 8-Br-cAMP infused into the entorhinal cortex of rats after training. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:905–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Faber ES, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher T, Laxmi TR, Stork O, Pape HC. Amygdalar and hippocampal theta rhythm synchronization during fear memory retrieval. Science. 2003;301:846–350. doi: 10.1126/science.1085818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shering AF, Lowenstein PR. Neocortex provides direct synaptic input to interstitial neurons of the intermediate zone of kittens and white matter of cats: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1994;347:433–443. doi: 10.1002/cne.903470309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamamaki N, Yanagawa Y, Tomioka R, Miyazaki J, Obata K, Kaneko T. Green fluorescent protein expression and colocalization with calretinin, parvalbumin, and somatostatin in the GAD67-GFP knock-in mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:60–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka R, Okamoto K, Furuta T, Fujiyama F, Iwasato T, Yanagawa Y, Obata K, Kaneko T, Tamamaki N. Demonstration of long-range GABAergic connections distributed throughout the mouse neocortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka R, Rockland KS. Long-distance corticocortical GABAergic neurons in the adult monkey white and gray matter. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:526–538. doi: 10.1002/cne.21504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth K, Freund TF. Calbindin D28k-containing nonpyramidal cells in the rat hippocampus: their immunoreactivity for GABA and projection to the medial septum. Neuroscience. 1992;49:793–805. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth K, Borhegyi Z, Freund TF. Postsynaptic targets of GABAergic hippocampal neurons in the medial septum-diagonal band of Broca complex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3712–3724. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03712.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuunanen J, Halonen T, Pitkanen A. Decrease in somatostatin-immunoreactive neurons in the rat amygdaloid complex in a kindling model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1997;26:315–327. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)00900-x. 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groen T, Wyss JM. The connections of presubiculum and parasubiculum in the rat. Brain Res. 1990;518:227–243. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90976-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Haeften T, Wouterlood FG, Jorritsma-Byham B, Witter MP. GABAergic presubicular projections to the medial entorhinal cortex of the rat. J Neurosci. 1997;17:862–874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00862.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, Hoyer D. Brain somatostatin: a candidate inhibitory role in seizures and epileptogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3767–3776. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouterlood FG, Van Denderen JC, Blijleven N, Van Minnen J, Hartig W. Two-laser dual-immunofluorescence confocal laser scanning microscopy using Cy2- and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies: unequivocal detection of co-localization of neuronal markers. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 1998;2:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(97)00038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]