Abstract

Abstract: Background

Diabetes self-management is complex and demanding, and isolation and burnout are common experiences. The Internet provides opportunities for people with diabetes to connect with one another to address these challenges. The aims of this paper are to introduce readers to the platforms on which Diabetes Online Community (DOC) participants interact, to discuss reasons for and risks associated with diabetes-related online activity, and to review research related to the potential impact of DOC participation on diabetes outcomes.

Methods

Research and online content related to diabetes online activity is reviewed, and DOC writing excerpts are used to illustrate key themes. Guidelines for meaningful participation in DOC activities for people with diabetes, families, health care providers, and industry are provided.

Results

Common themes around DOC participation include peer support, advocacy, self-expression, seeking and sharing diabetes information, improving approaches to diabetes data management, and humor. Potential risks include access to misinformation and threats to individuals’ privacy, though there are limited data on negative outcomes resulting from such activities. Likewise, few data are available regarding the impact of DOC involvement on glycemic outcomes, but initial research suggests a positive impact on emotional experiences, attitudes toward diabetes, and engagement in diabetes management behaviors.

Conclusion

The range of DOC participants, activities, and platforms is growing rapidly. The Internet provides opportunities to strengthen communication and support among individuals with diabetes, their families, health care providers, the health care industry, policy makers, and the general public. Research is needed to investigate the impact of DOC participation on self-management, quality of life, and glycemic control, and to design and evaluate strategies to maximize its positive impact.

Keywords: Advocacy, online communication, patient communication, social support, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes

1. Introduction

People with diabetes and their caregivers often describe feeling isolated in their experience of having and managing the complex, unrelenting demands of diabetes [1]. Stigma is common, and people with all types of diabetes experience substantial feelings of guilt, shame, and failure, specifically related to using insulin and conducting diabetes management tasks in public [2,3]. “Diabetes Online Community” (DOC) is a widely used term that encompasses all of the people who engage in various online activities related to living with diabetes across a collection of web-based platforms including community forums, blogs, video/podcasts, and social media websites/applications (e.g., Facebook, Twitter). Participants typically self-identify as part of the DOC and frequently include the hashtag “#doc” in their writing to note their affiliation with this virtual community.

The goals of this paper are to introduce readers to the range of online activities and outlets that comprise the DOC and to discuss the potential to impact the lives and health outcomes of people living with diabetes and their caregivers and families. Given the rapid growth of people with diabetes using the Internet in relation to their diabetes, this article aims to increase clinicians’ and researchers’ awareness of the diversity of sites people may be visiting and reasons for doing so. This article provides a brief history of diabetes-related activities across different Internet platforms and describes the various venues and modalities in which DOC activities take place. The potential benefits and risks of DOC participation are discussed. Research evidence related to outcomes of health-related online activity is reviewed, and recommendations for future research and effective engagement in the DOC are made. Several examples of DOC venues and writing excerpts are provided to illustrate key concepts, though such a limited set of examples cannot fully represent the experiences of all people who use online resources in relation to living with diabetes.

2. A Brief History of Diabetes Online

Over the past three decades, online activity focused on diabetes has grown at an extremely rapid pace. As early as the 1980s, discussions about diabetes began to take place online via proprietary dial-up services; the largest diabetes-related group communicated on misc.health.diabetes [4]. As the HTTP protocol associated with the World Wide Web became ubiquitous, much of the discussion moved to web-based discussion forums and newer social media platforms. The terms “diabetes online community” and its acronym “DOC” were first used to refer to the various online forums and content for people with diabetes and their families in 2005 on the blog Six Until Me (written by author KS, adult diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in childhood) [5]. An early DOC participant, Scott Johnson, adult diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in childhood and author of the blog Scott’s Diabetes, describes how he has seen the community grow: “There were four to five others who also started blogging [in the early 2000s] about their lives with diabetes. The [DOC] took off, and hasn’t slowed down since. A handful of us have turned into thousands of us” [6].

There is no formal tracking system for activities that occur under the large umbrella of the DOC, making exact rates of growth unavailable. However, the community’s scope and reach can be estimated through web analytic tracking tools, and examples of usage rates from selected online forums, blogs, and social media sites are indicative of the community’s size and activity. For example, in September 2014, a search of Facebook groups including the phrase “diabetes” resulted in more than 1,000 groups. Between October 2013 and September 2014, 522,000 unique users accessed the online forum ChildrenWithDiabetes.com (led by author JH, parent of an adult with type 1 diabetes diagnosed in childhood) and generated 841,000 posts on 75,000 discussion threads. As of September 2014, TuDiabetes.org, an online community for people living with all types of diabetes, had over 35,000 registered members (50% with type 1 diabetes, 20% with type 2 diabetes, 30% described as other), and EsTuDiabetes.org, its Spanish language counterpart, had over 29,000 registered members (20% with type 1 diabetes, 50% with type 2 diabetes, 30% described as other) from across the globe [7]. Popular diabetes-related blogs receive thousands of unique visits per month. The Diabetes Community Advocacy Foundation hosts a weekly one-hour live forum on Twitter using the hashtag #dsma (an acronym for Diabetes Social Media Advocacy), where people living with diabetes interact in real time: in 2010 there were an average of 40-50 participants per week, and current rates average 60-100 participants posting 700-1,000 comments per week, depending on the topic and time of year [8]. The wide reach and scope of the DOC suggest that online activities are an increasingly accessible and important component of everyday diabetes care for many people and families living with diabetes [9].

3. Who and What Comprise the DOC

3.1. DOC Participants

The DOC encompasses anyone engaged in online activity related to living with diabetes. It is not a specific website or organization and does not require any membership or official affiliation to participate. The DOC is largely comprised of individuals with type 1 diabetes (primarily adults) and the immediate family members of children with type 1 diabetes (primarily parents) [10]. There is a growing presence of individuals with type 2 diabetes and latent auto-immune diabetes of adulthood (LADA). Health care providers are becoming active in the DOC, although their involvement remains infrequent [10-12]. Industry representatives also participate in the DOC, with websites sponsored by various pharmaceutical and diabetes device companies that commission blogs and create feature content about life with diabetes.

Participation in the DOC can include a range of activities, such as creating and contributing original content, collating and reposting others’ content, commenting on or responding to others’ content, and/or observing and consuming others’ content. People who choose not to post content or comment on others’ postings may still benefit by observing or being consumers of DOC activities [13]. This may be helpful as individuals become familiar with the DOC and what they need from it.

3.2. Group Differences in DOC Access and Activity

Currently, DOC participants are primarily adults with type 1 diabetes and parents of children with type 1 diabetes, though discussions also address issues related to type 2 diabetes, LADA, gestational diabetes, and others. Adolescents and young adults are heavy Internet users [14] and many may wish to access health resources online [15], yet many DOC conversations emphasize parenting and older adult issues related to diabetes, which may limit adolescents’ interest or participation. There is also more limited DOC involvement among people with type 2 diabetes, although there are websites with broader focus and audiences that may meet many of the needs of this group. Given the proportionally larger prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes, more content targeted to the unique experiences of people living with type 2 diabetes might be needed. Alternatively, this may suggest greater unmet support needs among people with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers as compared to type 2 diabetes, perhaps related to greater intensity of self-management needs in type 1 diabetes.

The Pew Research Center recently published findings that over 90% of individuals in the United States go online daily and over 90% have a cell phone. Nearly 60% have smartphones [16]. Additionally, health-related social networking is growing: approximately one-quarter of Internet users access information about others’ experiences with health issues online and 16% of Internet users seek others with similar health concerns [17]. There is a gap in engaging in health-related activities online between those with and without chronic conditions: people with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, are less likely to be connected to the Internet (72%) than people without chronic conditions (89%) [18]. This may in part reflect that some people with chronic conditions have physical limitations that serve as barriers to using these devices, or may reflect low awareness of what disease-specific resources are available online. Additionally, although Internet access is reported to be approximately equivalent for people from different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds [19], the DOC (much like online communities for other health conditions [20,21]), may not be perceived as accessible or welcoming to people of different backgrounds. These group differences in access may perpetuate disparities in utilization and potential benefit.

3.3. DOC Venues

3.3.1. Community Forums

Community forums are websites that provide access to informational content and connections to other people living with diabetes. These forums are typically hosted by non-profit organizations that serve or advocate for people with diabetes or their families. Examples include ChildrenWithDiabetes.com, TuDiabetes.org and its Spanish-language partner site EsTuDiabetes.org, and MyGlu.com. Common features include discussion threads, chat boards, links to recent research, advocacy opportunities, surveys and polls, calendars of online and in-person events, and photo albums documenting diabetes-related activities and community events.

3.3.2. Blogs, Videos, and Podcasts

Individuals and groups often create content related to personal aspects of living with diabetes. Such content may be prose, video, or audio, and is posted on blogs, video hosting sites, or podcasts, respectively. The tone is usually subjective and anecdotal. The content varies widely and often centers around personal perspectives on living with diabetes or reflections on recent experiences with diabetes diagnosis, symptoms, treatments, and technologies.

3.3.3. Social Media Platforms

Social media platforms include websites and mobile applications, such as Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook. DOC participants use these to communicate, share content, and receive updates from others. Often referred to as “microblogging,” social media platforms typically feature photographs and written content (usually briefer than blog content), but cover much of the same material: personal reflections on diabetes-related issues, news updates including new research, or other links that may be of interest to followers. Individuals or organizations may use these platforms to direct readers to their own webpages or blogs, which often feature longer or more detailed content. These platforms also afford participants the ability to share as they have time or see fit without needing to create an ongoing narrative like a blog.

A unique feature of social media platforms compared to blogs or other resources is that the platforms can be used for real-time conversations. For example, the Diabetes Community Advocacy Foundation hosts weekly live chats on Twitter (known as “tweet-chats”) in which conversation prompts are broadcast publicly and participants respond and have real-time conversations about their personal, anecdotal experiences with diabetes. By using a shared hashtag (#dsma in this example), participants can follow the conversational thread.

3.3.4. Offline Contact with Online Community Members

There is ample evidence of the benefits of peer to peer support [22, 23], though this evidence is mostly based on direct in-person interactions rather than online support, which has less evidence supporting it to date [24]. Many DOC participants have connected in-person at live events, including both scientific and lay conferences, noting that often these contacts were initiated online through DOC activities. Examples include JDRF (formerly Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation) symposia, Children With Diabetes Friends For Life® annual conference, Diabetes UnConference, Taking Control Of Your Diabetes national conference, and DiabetesMine Innovation Summit.

4. Potential Benefits of the DOC

Reasons for participating in the DOC are numerous and individual. Research indicates that the most consistent reasons that people engage with the DOC include to seek emotional support and social connection, to share personal experiences, to learn and share medical information, and to become involved in advocacy efforts [25-34]. Various reasons for DOC participation and potential benefits of involvement are reviewed in the following paragraphs, with example quotes and excerpts as illustration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Quotes from diabetes online community (DOC) participants illustrating the main reasons for DOC involvement.

| DOC Purpose | Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Support and Connection | • “The encouragement and validation that I receive from a community that can say, ‘me too’ is as important to my health as the insulin that I take… Finding a community of people who get it, who have the same literal highs and lows that I do, has helped me and thousands of others who live with diabetes and feel scared and isolated feel empowered and connected…. Peer-to-peer support fosters resilience and confidence. It turns our shared vulnerability into empowerment, and we can gain strength from the places we normally feel weak.” [89] • “Hearing [about living with diabetes] from a veteran patient is different from hearing it from anyone else… Someone who knows the shoes you have been asked to walk in is a source of credibility beyond any other… Peers can best provide desperately needed emotional support… Who better to say, ‘you will be OK’?” [90] • “The DOC has really been the only way I could find my way out of that morass of self-doubt, insecurity, and negative thinking. Honestly, without them, I might not be here today …” [91] |

| Advocacy | • “It's through education, acceptance, and collaboration we can start to get rid of the stigmas from within. Then, and only then, can we get work on ridding ourselves of the diabetes stigma in the public eye.” [92] • “I didn’t get into #DOC to advocate or “make a diff.” I found peeps & decided I had stuff to share” [93]. In response: “@MHoskins2179 Interesting point. That was my motivation, too, but have learned how to advocate and make a diff from the #doc” [94] |

| Self-Expression | • “It’s liberating- putting your experiences out there. And more often than not, you’d hear from others who shared them, good and bad” [95] • “I share my story online because I have no other outlet for it and can find others who relate.” [96] • “Once I started sharing my diabetes life, I found I had a lot to say. I started to meet other diabetes bloggers in person, and I started to build some very important friendships.” [97] |

| Information & Education | • “Before finding the DOC I was basically living status quo – and frankly didn’t know nearly what I should’ve known after all those years… I’ve been armed with so much information [since finding the DOC] and am in such better control. And it helps having a fully loaded support group just a click away.” [98] • “[Once I found the DOC,] I was empowered to take control of my diabetes… My A1C dropped … because the number of times I tested my blood sugar per day rose from less than once to more than six. I started on a continuous glucose monitor. I tweaked my basal rates. I learned to combo bolus the hell out of pizza. I learned a whole new language with which to bring my diabetes up with my friends and coworkers and boyfriend. I learned that I had a future. The DOC taught me these strategies and more for seamlessly incorporating diabetes in with the rest of my life and the impact was huge.” [98] |

| Open-Source | • “We feel a lot more comfortable with her going to playdates and parties on her own because we can watch. I don't have to sit in the room during dance or cheer practice. She is able to have a lot more freedom… We just feel... safer. More in control. Two things that are priceless when dealing with type 1 diabetes” [99] • At this stage [CGM in the Cloud] is purely experimental and totally “at your own risk”. There isn’t a user manual and a dedicated tech support line to call. There is a lot of knowledgeable parents and people with diabetes who have worked to develop this technology, as well as a growing community of users who are supportive and innovative in their own right and willing to share their experiences to help others.” [100] |

| Humor | • “My 14 year old son had just been diagnosed with [type 1 diabetes] in the spring and we were on our first beach vacation with diabetes. He wanted to walk on the boardwalk with his older brother but did not want to carry any supplies. As I was pleading with him, my voice got louder and louder until I was shouting, “Take the needles! Take the needles!” My husband was coming from around the corner and said that it sounded like some kind of drug deal!” [61] • You know you’re a parent of a child with diabetes when… “you’re the only mother at playgroup chasing around your 3 year-old yelling, ‘If you don’t come eat these jellybeans right know, I’ll put you in time out!’” [61] |

4.1. Supplement to Medical Care

People with diabetes are recommended to check in with their diabetes care team quarterly for lab work and physical examinations [35], resulting in only a few hours of face-to-face contact with medical professionals for diabetes each year. Even with many health care providers increasing their accessibility between visits, people with diabetes still spend over 8,000 hours per year self-managing their diabetes outside of the medical setting. Interacting with other people living with diabetes has the potential to supplement medical care between visits [36-37]. A substantial number of people with diabetes wish to find diabetes communities for support [25]. DOC resources may fulfill this need for many while also serving as resources to which clinicians may refer their patients.

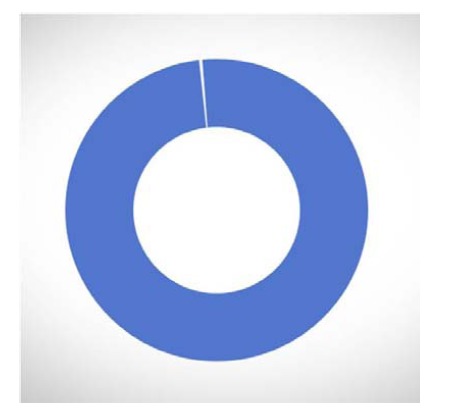

One image that some DOC participants have used to represent this concept is a blue circle with a small sliver removed (Fig. 1), an adaptation of the blue circle symbol of the International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) [38]. In the adapted image, the white sliver represents the proportion of time per year spent with a medical professional, and the blue represents the remainder of time in which individuals are expected to self-manage diabetes and in which additional support may be helpful [39].

Fig. (1).

Symbol representing peer support offered by the DOC (courtesy of the Diabetes Hands Foundation). This image is an adaptation of the blue circle symbol of the International Diabetes Foundation (IDF): the white sliver represents the proportion of time per year spent with a medical professional, and the blue represents the proportion of time in self-management, peer support may be helpful.

4.2. Support and Connection

People with chronic health conditions often endorse feeling more comfortable sharing their experiences and struggles with others who can relate based on their own, related experiences [40, 41]. It should not be surprising, then, that peer-to-peer support is one of the primary reasons for participation cited by DOC participants. Many have written that sharing their struggles and celebrating their successes, large or small, helps them more effectively accomplish the daily tasks of diabetes self-management. The support people find on the DOC can be both emotional and practical, and people describe how their experiences on the DOC can impact their emotional well-being, health behaviors, and diabetes outcomes (Table 1).

The literature supports these users’ anecdotal endorsements. A 2011 study of health bloggers across a number of chronic conditions demonstrated that people who more frequently blogged about health issues perceived more social support, particularly when they received at least one comment on their posts. Moreover, bloggers’ perceptions of support from their readers were linked with feeling more confident in their ability to manage their health condition [42]. A Dutch survey of participants in online support groups for people with breast cancer, arthritis, and fibromyalgia reported similar findings: regardless of posting frequency, participants reported increases in confidence and self-esteem, but those who contributed more frequently experienced greater social benefits of participation [13].

4.3. Local and Global Advocacy

Diabetes related stigma contributes to frequent and significant negative experiences [2, 3]. Much activity of the DOC is focused on advocacy initiatives for diabetes-related issues and policy. Opportunities for advocacy are frequently facilitated and promoted through diabetes blogs and other DOC forums (Table 1). A wide range of advocacy activities occur within the DOC, including diabetes education, offering support, organizing community events, and serving as “consumer watchdogs” for diabetes-related products [43].

Much of the advocacy that happens in the DOC is personal in nature: DOC participants sharing their stories, experiences, art, and photos on social media increases the public’s exposure to and awareness of diabetes. For example, Sierra Sandison brought type 1 diabetes to the forefront of the national media when she wore her insulin pump visibly during the swimsuit portion of the Miss Idaho 2014 pageant. She coined the hashtag #showmeyourpump and encouraged others to join her by using that hashtag and by posting pictures of themselves proudly donning their own insulin pumps (and other diabetes management devices) [44].

Advocacy organizations have websites dedicated to diabetes, one of the most prominent and active of which is Diabetes Advocates, organized by the Diabetes Hands Foundation (DHF). Diabetes Advocates organizes advocacy skills workshops and publicizes concrete actions that individuals can take to lobby for changes in local and national policies that affect people with diabetes [45]. DHF also sponsors the Big Blue Test, an annual social media event designed to promote diabetes self-care, educate, and reduce stigma about diabetes and its management: DOC participants post their blood glucose values before and after physical activity on social media with the hashtag #bigbluetest, and DHF donates to nonprofit diabetes organizations for each #bigbluetest entry logged [46].

National and international organizations such as the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and JDRF also host websites and sponsor social media campaigns to engage people in diabetes advocacy activities. In 2014, the Federal Drug Administration received over 500 comments on an open docket about regulation of medical device data systems, largely attributed to publicity on the DOC [47, 48]. In 2013, the Partnering for Diabetes Change Coalition created the “Spare a Rose, Save a Child” campaign to benefit the International Diabetes Federation’s Life for a Child Programme, which provides an opportunity for people to make small donations that fund insulin and diabetes management supplies for people with diabetes in developing countries [49]. The DOC actively promotes the campaign through blogs and social media, and the successful growth of its activities (with an 8-fold increase in contributions to over $28,000 in 2014: enough to provide insulin to about 450 children with type 1 diabetes for one year) drew specific mention from the Life for a Child Programme’s general manager [50].

4.4. Self-expression

Personal story-telling is common in the DOC (Table 1). During a September 2014 tweet-chat discussing DOC participants’ reasons for sharing their diabetes stories online, many discussed the benefits of self-expression: “It helps me to put my feelings into a tangible form and I hope that it helps someone else who comes across it” [51]; “Mostly for myself-way to think through things. Also didn’t find many voices of T1 parents with T1 kids & wanted to speak to that” [52]; and “I write about my diabetes in order to cope; I share what I write in the hope that it inspires others to help themselves” [53]. The literature supports what DOC participants have discovered: writing about stressful experiences, particularly in relation to one’s health or caring for a child with a health condition, has been linked with improved psychosocial well-being and some health outcomes [54, 55]. Similar findings in a qualitative study of people with cancer further illustrate the immense perceived impact of blogging and reading others’ health-related writing online [56].

4.5. Information and Education

Many people go online to learn about diabetes and diabetes management, and specifically information on treatment options and devices. Personal experiences tend to be shared frequently and DOC participants often use the hashtag “#YourDiabetesMayVary” to acknowledge that diabetes care is personalized, that information posted online is not intended as medical advice, and to stress the need for people with diabetes to discuss with their medical team any information found online.

Among those DOC participants seeking information, the experiences of other people living with diabetes are often seen as trusted resources (Table 1). DOC participants often review new diabetes-related products (e.g., new technology/device, piece of clothing to conceal/hold devices, new glucose tab formulation). In addition, the DOC can guide people with diabetes to resources available through moderated community forums such as ChildrenWithDiabetes.com, or to reputable websites such as the JDRF or the ADA, to assist with management in a school or camp setting, information about diet or exercise, and a variety of other topics. Though often addressed by the health care team, current practice environments may not allow as much detail as people with diabetes may want during office visits.

4.6. Data Management

Current diabetes management technologies such as glucose meters, insulin pumps, and continuous glucose monitors (CGM) capture a great deal of data, which can be used to inform diabetes care decisions such as insulin adjustments and to result in better glycemic control [57]. However, much of the data is housed in device-specific software programs and cannot be easily shared between devices. This forces people with diabetes and their providers to rely on device companies’ software programs, limits accessibility to data and leaves much data unused, and makes it difficult to identify important patterns and trends in blood glucose and insulin usage. There is a growing movement to develop programs that can access data across multiple devices from multiple device manufacturers, free from the proprietary systems that limit such integration.

Largely comprised of individuals directly affected by type 1 diabetes, one example is Tidepool, a non-profit organization that is developing secure, HIPAA-compliant, cloud-based platforms and apps to integrate data from multiple diabetes management devices [58, 59]. Another example is “Nightscout” (also known by the name of its Facebook group, “CGM in the Cloud”), formed online by a group of fathers of children with type 1 diabetes to develop tools to access their children’s real-time interstitial glucose values beyond the limits of the CGM systems’ transmitter-receiver pair. With the collaborative input of other interested parents and experts in the DOC, they developed and made public a how-to guide to transmit data from a Dexcom G4 CGM system and view it remotely, well before Dexcom’s Share system was available. Nightscout, which has over 10,000 members in its Facebook group, later worked with the FDA to argue for wider availability of data produced by CGMs and other devices. They were successful, and the FDA significantly changed their rules such that software displaying medical device data does not require marketing approval, but must simply be registered with the FDA. In fact, this has already led to much faster than expected availability of Dexcom’s own software solutions to this issue, and is expected to affect medical device data beyond diabetes [60].

Interactions among DOC participants surrounding these data management movements tend to focus on either sharing information and helping one another explore and set up the technologies, or describing how individuals or families use these technologies to monitor their own or their child’s current glucose values in ways they could not easily do otherwise (e.g., while traveling, at school, playing sports) (Table 1). As with any technological advance, there are concerns about risks, such as privacy and accuracy. Finding a balance between the amount of data, access to that information, security, and permissions among family members about viewing the data will be critical to the success of these types of movements and systems.

4.7. Humor

For people living with chronic health conditions, humor and levity are commonly used coping strategies [31], and DOC participants frequently share amusing experiences about living with diabetes (Table 1). Numerous websites have areas specifically devoted to humor, such one page inviting people to complete the sentence “You know you’re a parent of a child with diabetes when…” with amusing anecdotes; an online “dictionary” of diabetes puns; and web-spaces devoted to diabetes-related cartoons [61, 62].

5. Potential Risks of DOC Involvement

5.1. Privacy and Security

Despite the numerous potential benefits of the DOC, there are potential risks as well, and health care providers and people with diabetes should be aware of them. Many of these risks are common to any online activity, not unique to participation in the online diabetes-related activities. They can be minimized through safe Internet practices that are recommended for any site or forum. Examples include issues related to privacy and security. Such risks come with users’ disclosure of more information than is needed or perhaps even advisable in any online activity, such as names, children’s ages or photos, and contact information. This could potentially lead to opportunities for online bullying, harassment, sexual predation, financial exploitation, and other possibilities that may exist with any such online activity. However, sharing diabetes information and stories online does not require full disclosure. Anonymity is generally accepted across diabetes related online resources, and participants have varying levels of comfort with disclosing health information online. Many participants opt to use their full names and real photos in blogs and other online activities, while many others do not. Social media sites and discussion forums typically allow users to create anonymous profiles without personally identifiable markers. Many DOC participants create anonymous online nicknames using clever diabetes-related wordplay (e.g., @badpancreas, @ninjabetic, @humnpincushion).

5.2. Bad Behavior

Negative messages and unpleasant interactions may occur in any community, and public forums like the Internet are no exception. While most people behave politely online, a small number do not, and there is sometimes discussion on message boards or in blogs about what various participants think is “right” or “wrong” (e.g., whether to check blood glucoses at night, the advantages/disadvantages of particular diets or devices, the ideal target glucose ranges). These behaviors represent what Suler and colleagues call “the online disinhibition effect,” in which people behave in ways online that they would likely not behave in person [63]. To prevent this, websites with terms of service prohibit cruelty, foul language, marketing products, and requesting donations, and moderated websites systematically remove posts that do not adhere to the terms of use.

With the perceived anonymity of an online persona, negative communications pose a threat to any online community. Online forum managers can block the accounts and remove the messages of identified users who intentionally seek to cause problems, often by posting inflammatory messages and provoking arguments [64]. There are also advanced technologies to help protect against computers compromised by viruses or malware, and against other online threats [65, 66].

5.3. Misinformation

One potential barrier to comfort with seeking information online about diabetes is caution among people with diabetes and their health care providers and caregivers regarding the accuracy and quality of information available online [67]. These worries are not unfounded: Scullard and colleagues found that accurate information about a variety of conditions and health concerns was only provided about 40% of the time and that most of the time, no information (or answer to a specific question) was given [68]. Many sites, blogs, and social media accounts are not moderated, and it would be impossible for trained medical or mental health professionals to keep up with the constantly growing online content, making it difficult to know whether information provided online is trustworthy.

Health care providers may choose to vet online content before recommending it to their patients and families. There are some strategies to authenticate the source of information and assess whether it reflects personal opinions or professional advice. For example, websites of professional diabetes organizations such as the ADA or academic institutions can generally be trusted to include accurate health information and links to reviewed websites. In addition, most websites and blogs typically contain disclosures, disclaimers, or terms of use that include two key points: 1) content is not intended to be medical advice, and 2) content represents the personal views of the person writing the information. This is the case for both professional websites providing information about health and for personal blogs. Diabetes care providers should consider incorporating questions about information their patients are learning online during their clinic visits. It may help to take the approach of reviewing information they have found online and distinguishing between valid, reliable content and unreliable or potentially harmful content [67].

As with other health conditions, people with diabetes must evaluate the legitimacy of medical information they receive online. For example, based on direct observations of women searching the Internet for information about menopause and hormone replacement therapy, researchers in England described a three-stage process: (1) scanning online content to sift out untrustworthy sites, (2) careful review of remaining sites for relatability and integrity, and (3) integrating online information with advice from family, friends, and medical professionals [69]. Consistent with these findings, a recent Pew survey reported that people with chronic medical conditions were more likely to discuss health information found online with a healthcare provider, compared to internet users without chronic conditions [18]. It is likely that similar processes take place for people with diabetes, with online resources representing one of several sources of diabetes-related information, including healthcare professionals.

5.4. Influence From Industry

Numerous studies demonstrate the potential influence industry has on physician prescribing behaviors [70, 71]. With industry presence online, it is possible that DOC participants will also be persuaded to request certain products from their healthcare providers, based on information they find online. For instance, many blog owners may have relationships with industry, and even if sponsorships are disclosed on the blog, it is possible that readers may still be influenced.

6. Guidelines for Personal and Professional Participation in the DOC

One goal of this paper is for diabetes care providers to become more familiar with the DOC and encourage their patients to connect online with other people living with diabetes. Diabetes care providers may also wish to become involved in the DOC themselves, to learn more about the experiences of people living with diabetes and to contribute to the conversations online. People with diabetes often want their providers to refer them to others with diabetes [72], making provider awareness of the DOC part of a patient-centered approach to care. In addition, health care providers have limited resources to provide one-on-one interventions and support to people with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, and referral to online support and networks has the potential to be an important supplement to professional health care services.

Health care provider involvement in the DOC has the potential to improve clinical care in many ways, yet limited data exist to inform how health care professionals can appropriately do so. The American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards issued a joint position paper that offers advice for online professionalism for physicians [73], the focus of which was primarily how physicians and the profession could protect themselves from unethical involvement in online communities. A 2012 study found that 92% of state medical boards had received reports of online violations from medical professionals [74], underscoring the importance of such a position statement. However, lack of other research may leave many health care providers unsure how to interact with or counsel their patients regarding online diabetes resources.

It is possible that simply reading blogs and comments could offer diabetes care providers valuable insight about their patients’ experiences, and a deeper understanding of various barriers to care. Author KS blogged about a common sentiment among DOC participants, “I’d like to see more medical professionals listening and becoming more involved in the community online… having a sense of the ‘whole person’ behind a disease goes a very long way in caring for someone’s health” [75]. Another DOC participant and certified diabetes educator (CDE) tweeted about why she values the DOC as a provider, “I look to the #DOC for firsthand perspectives of #PWD [people with diabetes]. Makes me a better person/CDE” [76]. Given the potential benefits, we have developed initial guidelines to help healthcare providers both guide their patients toward the DOC and to participate themselves (Tables 2 and 3), not only for support and information but also for possible therapeutic benefit. In Table 4 we present similar guidelines for industry.

Table 2.

Guidelines for patients and families new to the diabetes online community (DOC).

| Topic | Tips |

|---|---|

| Privacy protection | 1. Try to separate diabetes versus non-diabetes social media participation. Consider using an email address dedicated to DOC activity. 2. You may want to protect your child’s identity, especially in relation to their diagnosis. Consider referring to your children with a nickname rather than real name. |

| Medical advice | 3. Discuss any ideas about changes to the diabetes care plan that you see on the DOC with your health care provider. 4. There are many ways to approach diabetes care. What works for one person/family may or may not work for you. Try not to take differences of opinion or approach personally. |

| Tips from other DOC participants | 5. “Be real. Share personal experiences. Listen to others without judging” [101] 6. “Empathy should come first. We’re all in this together and all at different stages. Be patient” [102] 7. “Don’t be afraid to tell your story. Someone is out there who needs to hear it” [103] 8. “Give of yourself & you will receive. Ask for help & someday you will give help” [104] 9. “Keep your eyes, ears, and mind open to others. And also keep your fingers on the keyboard and add to the conversation” [105] 10. For information and guidance on getting involved in weekly tweet-chats, see http://diabetessocmed.com/about/ and http://bleedingfinger.com/how-to-get-involved-with-the-doc-twitter-style-a-da-initiative/ |

Table 3.

Guidelines for health care professional (HCP) participation in the diabetes online community (DOC).

| Topic | Tips |

|---|---|

| Personal vs. professional roles |

1. HCPs should keep personal (i.e., social networking with family or friends, content unrelated to healthcare provision) and professional (i.e., online activity related to healthcare provision) participation in social media separate. 2. Create accounts with different email addresses. Consider using an anonymous handle for personal account. 3. Be cautious about including patients and their family members in personal social media activities (e.g., decline friend requests to personal account from patients). |

| General vs. specific advice | 4. Sharing general best practices or providing information about established, evidence-based guidelines can be very helpful. 5. Try to refrain from offering medical opinions on other DOC participants’ personal choices unless there is evidence of clear danger. 6. Because the DOC is largely for support, try to refrain from giving prescriptive advice in response to others’ postings unless requested to do so. |

| Watch and learn | 7. HCPs can learn a great deal about living with diabetes by getting involved in the DOC, either by participating or by lurking. Read websites to determine those that you are comfortable referring your patients to read. 8. Approaching the DOC with a nonjudgmental, open-minded attitude is encouraged! |

| Encourage your patients | 9. Let your patients know that there is much to learn from others living with diabetes and that you are eager to hear about new ideas and suggestions. This helps patients to see their HCP as a partner in their exploration of diabetes social media. 10. Direct your patients to websites that you have reviewed and that you trust, and encourage them to explore other websites but to be cautious and discuss with you any diabetes-related health advice found online [67]. |

Table 4.

Guidelines for industry representatives on the diabetes online community (DOC).

| Topic | Tips |

|---|---|

| Transparency | 1. Be honest about your role as a member of industry in your DOC activities. 2. Use your real name (first name is sufficient) and identify the company you represent. 3. DOC participants who receive sponsorship from industry should disclose that clearly on relevant DOC postings. |

| Information vs. Sales | 4. Answer factual questions about your company’s product(s). That can include directing people to your corporate website. 5. Do not use the DOC to sell or market your company’s product. 6. Do not badmouth competitors’ products. |

7. Research and Outcomes of DOC involvement

Just as health care professionals’ involvement in the DOC is not yet widespread, research on this topic is also quite limited and focuses most on patterns of engagement and preferences of DOC participants. Rigorous research evaluating the outcomes of DOC involvement is just beginning to emerge. A major limitation of research in this area, for the DOC and other health communities, is that online programs that are evaluated are typically included as part of larger multicomponent interventions, making it impossible to evaluate the direct impact of online support or activity [36, 77, 78]. Moreover, the online portions of those studies are often moderated chat sessions led by a trained health professional [79, 80], which are different than unmoderated blogs or interactions more commonly found online. Research on health-related online activities outside of these research-based intervention studies is further limited by imperfect and imprecise research methods [81]. This is likely to change, however, as new methods are being developed to quantify and analyze online activity and materials [81-83].

Though limited literature exists, this section reviews available research on the emotional, social, behavioral, and clinical outcomes of online activities related to diabetes specifically, and to other chronic health conditions where diabetes-specific information is not available.

7.1. Impact on Emotional and Social Well-being

A few studies have evaluated emotional outcomes of people involved with particular online resources for people with diabetes. In one of the first studies on this topic, researchers developed an Internet resource for individuals with diabetes around the world, which included educational content and discussion boards. Over two-thirds of participants reported improvements in feeling hopeful about their diabetes and in how they cope with diabetes management after using the online resource [84]. Balkhi and colleagues reported results of a survey of parents of children with type 1 diabetes who used various diabetes-focused online forums. Over 90% reported benefits in increased social support and/or diabetes knowledge, and 84% reported making changes in how they managed their child’s diabetes based on experiences in the forum [30]. Though subject to potential selection bias, the findings overwhelmingly demonstrate that many people perceive benefits of accessing information and social support online. Finally, a review of strategies to use peer support to impact diabetes outcomes concluded that online social support may be a promising approach especially for people who are isolated geographically [85].

Data from other online health communities are consistent with these findings. For example, a systematic review of studies of online cancer support concluded that despite small sample sizes and few randomized controlled trials, the trend toward improved psychological and social outcomes was promising [86]. Similarly, quantitative and qualitative data from participants in a variety of online health support groups note perceptions of benefits, including having learned helpful health information online, increased confidence in patient-provider interactions, and increased optimism and control in relation to disease [13, 87].

7.2. Impact on Self-Management Behaviors and Clinical Outcomes

There are less data available on associations between DOC participation and behavioral and clinical outcomes such as diabetes self-management behaviors and glycemic control. A recent meta-analysis reported trends toward positive impact of health behavior change interventions that included social networking, although it was difficult to isolate the effects of the online activity from other components of the intervention [77]. Across a variety of chronic medical conditions, Bartlett and colleagues reported on the impact of participation in various online support groups: over 80% of participants incorporated information gained in the groups into their communication with health care providers, and more than half described positive impact on the patient-provider relationship [88]. Although not specific to diabetes, these findings have implications for DOC participants’ ability to strengthen health behaviors and to share knowledge and encourage one another to advocate for themselves with their health care providers.

7.3. Future DOC Research Directions

As the DOC continues to expand, there will be more opportunities to investigate the degree to which different types of DOC involvement impact emotional well-being, diabetes management behaviors, and health outcomes. An important first step will be to conduct descriptive research to characterize subgroups of people living with diabetes and their caregivers who do or do not participate in the DOC, and to understand the reasons for or barriers to participation. Among DOC participants, research evaluating the content and user characteristics of different DOC outlets may help people with diabetes and their families and providers decide which areas of the DOC best suit individual needs. Likewise, additional research could help explain the disproportionately greater online activity and availability of DOC resources for type 1 diabetes than for type 2 diabetes. Given the limitations of trials involving online health activities, future research on the outcomes of DOC involvement may instead use naturalistic observation studies to track the psychosocial, self-management, and clinical factors of individuals with little or no prior DOC involvement over time, including an assessment of the frequency and type of their diabetes online activities.

8. Closing comment

There is a great deal of potential for the DOC to be used as a tool to strengthen patient-provider relationships and ultimately health care delivery and outcomes: the DOC can help people with diabetes become informed and empowered, and can also give healthcare providers insight into the many hours people spend self-managing diabetes outside of their direct medical oversight.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. Hilliard and Dr. Oser's work on this paper was supported by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Hilliard: 1K12 DK097696, PI: B. Anderson; Oser: 1DP3 DK104054, PI: S. Oser).

We appreciate the generosity of the DOC participants for eloquently sharing their experiences and words. We also appreciate the constructive feedback of Sean Oser, MD and the editorial assistance of Courtney Titus in preparing this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tierney S., Deaton C., Webb K., et al. Isolation, motivation and balance: Living with type 1 or cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. J. Nurs. Healthc. Chronic Illn. 2008;17:235–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folias A., Brown A.S., Carvalho J., Wu V., Close K.L., Wood R. Investigation of the presence and impact on patients of diabetes social stigma in the USA. Diabetes. 2014;15(Suppl. 1):59. [-LB.]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf A., Liu N. The numbers of shame and blame: How stigma affects patients and diabetes management. 7 August 2014: Available from: http://diatribe.org/issues/67/learning-curve. on 13 November . 2014.

- 4. No author. Diabetes Index. 27 March 2014: Available from:http://www.faqs.org/faqs/diabetes/ on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 5.Sparling K. Rage bolus, anyone? 4 October 2005: Available fromhttp://sixuntilme.blogspot.com/2005/10/rage-bolus-anyone.html. on 13 November . 2014.

- 6.Johnson S.K. Thinking about starting a diabetes blog? No date: Available from: http://www.t1everydaymagic.com/thinking-aboutstarting- a-diabetes-blog/ on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 7.Hernandez M. Personal communication with Jeff Hitchcock, 9 October . 2014.

- 8.Shockley C. Personal communication with Kerri Sparling, 9 October . 2014.

- 9.Makaya T. Social media and smart technology in diabetes: One small step … one giant leap. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2014;10:283. doi: 10.2174/1573399810666141010114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert K., Dodson S., Gill M., McKenzie R. Online communities are valued by people with type 1 diabetes for peer support: How well do health professionals understand this? Diabetes Spectr. 2012;25:180–191. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMahon K.L. Power and pitfalls of social media in diabetes care. Diabetes Spectr. 2013;26:232–235. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grajales F.J., Sheps S., Ho K., Novak-Lauscher K., Eysenbach G. Social media: A review and tutorial of applications and medicine in health care. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014;16:e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Uden-Kraan C.F., Drossaert C.H., Taal E., Seydel E.R., van de Laar M.A. Self-reported differences in empowerment between lurkers and posters in online patient support groups. J. Med. Internet Res. 2008;10:e18. doi: 10.2196/jmir.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duggan M., Smith A. Social media update 2013. 30 December 2013. Available from:http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/12/30/social-media-update-2013/ on 21 November 2014. 2013.

- 15.Fergie G., Hunt K., Hilton S. What young people want from health-related online resources: A focus group study. J. Youth Stud. 2013;16:579–596. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2012.744811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith A. Smartphone ownership 2013. 5 June 2013. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/06/05/smartphoneownership- 2013/ on 21 November 2014. 2013.

- 17.Fox S., Duggan M. Health online 2013. 15 January 2013. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/ on 21 November 2014. 2013.

- 18.Fox S., Duggan M. The Diagnosis Difference. 26 November 2013. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/11/26/thediagnosis- difference/ on 24 February 2015. 2015.

- 19.Zickhur K. Who’s not online and why. 25 September 2013. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/25/whos-notonline- and-why/ on 21 November 2014. 2013.

- 20.Viswanath K, McCloud R, Minksy S, et al. Internet use, browsing, and the urban poor: Implications for cancer control. J Nat Cancer Inst Monogr . 2013;2013:199–205. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eddens K.S., Kreuter M.W., Morgan J.C., et al. Disparities by race and ethnicity in cancer survivor stories available on the web. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009;11:e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dam H.A., van der Horst F.G., Knoops L., Ryckman R.M., Crebolder H.F., van den Borne B.H. Social support in diabetes: A systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005;59:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale J.R., Williams S.M., Bowyer V. What is the effect of peer support on diabetes outcomes in adults? A systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2012;29:1361–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eysenbach G., Powell J., Englesakis M., Rizo C., Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: Systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004;328:1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene J.A., Coudhry N.K., Kilabuk E., Shrank W.H. Online social networking by patients with diabetes: A qualitative evaluation of communication with Facebook. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;26:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1526-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris M.A., Hood K.K., Mulvaney S.A. Pumpers, skypers, surfers and texters: Technology to improve the management of diabetes in teenagers. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2012;14:967–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arduser L. Warp and weft: Weaving the discussion threads of an online community. J. Tech. Writ. Commun. 2011;41:5–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norfeldt S., Bertero C. Young patients’ views on the Open Web 2.0 childhood diabetes patient portal: A qualitative study. Future Internet. 2012;4:514–527. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho Y., O’Connor B.H., Mulvaney S.A. Features of online health communities for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014;36:1183–1198. doi: 10.1177/0193945913520414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balkhi A.M., Reid A.M., McNamara J.P., Geffken G.R. The diabetes online community: The importance of forum use in parents of children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2013;15:408–415. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niela-Vilen H., Axelin A., Salantera S., Melender H. Internet-based peer support for parents: A systematic integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014;51:1524–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zriebec J.F., Jacobson A.M. What attracts patients with diabetes to an internet support group? A 21-month longitudinal website study. Diabet. Med. 2001;18:154–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen A.T. Exploring online support spaces: Using cluster analysis to examine breast cancer, diabetes and fibromyalgia support groups. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012;87:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravert R.D., Hancock M.D., Ingersoll G.M. Online forum messages posted by adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:827–834. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American Diabetes Association. 2014.

- 36.Van Dam H.A., van der Horst F.G., Knoops L., Ryckman R.M., Crebolder H.F., van den Borne B.H. Social support in diabetes: A systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005;59:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dale J.R., Williams S.M., Bowyer V. What is the effect of peer support on diabetes outcomes in adults? A systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2012;29:1361–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.International Diabetes Foundation Blue circle. No date: Available from: http://www.idf.org/bluecircle. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 39.Hernandez M. Art and Science of Applying Behavioral Medicine Principles to the Diabetes Online Community (DOC).; Proceedings of the 74th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association; June 2014; San Francisco, CA, USA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan-Bolyai S., Lee M.M. Parent mentor perspectives on providing social support to empower parents. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37:35–43. doi: 10.1177/0145721710392248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenhalgh T., Collard A., Begum N. Sharing stories: Complex intervention for diabetes education in minority ethnic groups who do not speak English. BMJ. 2005;330:628–632. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rains S.A., Keating D.M. The social dimension of blogging about health: Health blogging, social support, and well-being. Commun. Monogr. 2011;78:511–534. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tenderich A. Advocacy, DSMA-style. 28 February 2014: Available from: http://www.diabetesmine.com/2014/02/advocacyjournalism- diabetesmine-style.html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 44.Benner S. Interview: Miss Idaho Sierra Sandison #ShowMeYour- Pump. 25 July 2014: Available from:http://www.ardensday.com/blog/2014/7/25/interview-miss-idahosierra- sandison-showmeyourpump. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 45.Diabetes Hands Foundation Diabetes action hub. 2 July 2014: Available from: http://diabetesadvocates.org/masterlab/ on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 46.Diabetes Hands Foundation What is big blue test? No date: Available from: http://bigbluetest.org/what-is-big-blue-test/ on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 47.Dunlap B. Unexpected ways the DOC improves diabetes. 28 August 2014: Available fromhttp://www.ydmv.net/2014/08/unexpected-ways-doc-improvesdiabetes. html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 48.Tenderich A. On regulation and cyber-security of our diabetes devices. 29 July 2014: Available from:http://www.diabetesmine.com/2014/07/regulation-andcybersecurity- of-our-diabetes-devices.html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 49.Partnering for Diabetes Change Partnering for Diabetes Change. Welcome. No date. Available from: http://www.p4dc.com/welcome/ on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 50.Ogle G. Save a child thank you update. 24 February 2014: Available from: http://www.p4dc.com/wpcontent/ uploads/2014/02/LFAC-save-a-child-thank-you-update.pdf. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 51.Name No. No Name (@humnpincushion). “It helps me to put my feelings into a tangible form and I hope that it helps someone else who comes across it.” 24 September 2014, 6:33 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 52.Kimball Lesley. (@poeticlibrarian). “Mostly for myself-way to think through things. Also didn’t find many voices of T1 parents with T1 kids & wanted to speak to that.” 24 September 2014, 6:34 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 53.Grinnell James. (@t1dme). “I write about my diabetes in order to cope; I share what I write in the hope that it inspires others to help themselves.” 24 September 2014, 6:36 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 54.Mugerwa S., Holden J.D. Writing therapy: A new tool for general practice? Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012;62:661–663. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X659457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pennebaker J.W., Chung C.K. Expressive writing: Connections to physical and mental health. In: Friedman H.S., editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health kilPsychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiu Y.C., Hsieh Y.L. Communication online with fellow cancer patients: Writing to be remembered, gain strength, and find survivors. J. Health Psychol. 2013;18:1572–1581. doi: 10.1177/1359105312465915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mauras N., Fox L., Englert K., Beck R.W. Continuous glucose monitoring in type 1 diabetes. Endocrine. 2013;43:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tidepool. Giving data a home and you the keys. No date: Available from: http://tidepool.org/about. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 59.Thrower D. The data is yours. 27 January 2014: Available from:http://www.snappump.com/node/307. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 60.Linebaugh K. Smartwatch app helps track glucose. 8 February 2015: Available from: http://www.wsj.com/articles/smartwatchapp- helps-track-glucose-1423443067. on 8 February 2015. 2015.

- 61.Children With Diabetes Humorous tidbits. No date: Available from: http://www.childrenwithdiabetes.com/people/tidbits.htm. on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 62.Sparling K. Diabetes terms of endearment eBook. 29 September 2011: Available from:http://sixuntilme.com/2011/09/diabetes_terms_of_endearment_e.html. on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 63.Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 2004;7(3):321–326. doi: 10.1089/1094931041291295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhuo J. Where anonymity breeds contempt. 29 November 2010: Available from:http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/30/opinion/30zhuo.html. on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 65.Stop Forum Spam FAQ. No Date: Available from:http://www.stopforumspam.com/faq. on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 66.BotScout About. No Date: Available from:http://www.botscout.com/about.htm. on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 67.Hernandez M. Diabetes and social media: A prescription for patient engagement. Diabetes Manage. 2013;3:203–205. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scullard P., Peacock C., Davies P. Googling children’s health: Reliability of medical advice on the internet. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010;95:580–582. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.168856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sillence E., Briggs P., Harris P.R., Fishwick L. How do patients evaluate and make use of online health information? Soc. Sci. Med. 2007;64:1853–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: Is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sah S., Fugh-Berman A. Physicians under the influence: Social psychology and industry marketing strategies. J. Law Med. Ethics. 2013;41:665–672. doi: 10.1111/jlme.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greene A. What healthcare professionals can do: A view from young people with diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes. 2009;10(Suppl. 13):50–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farnan H.M., Sulmasy L.S., Worster B.K., Chaudhry H.J., Rhyne J.A., Arora V.M., American College of Physician Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee, the American College of Physicians Council of Associates, and the Federation of State Medical Boards Special Committee on Ethics and Professionalism Online medical professionalism: Patient and public relationships: Policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158:620–627. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greysen R.S., Chretien K.C., Kind T., Young A., Gross C.P. Physician violations of online professionalism and disciplinary actions: A national survey of state medical boards. JAMA. 2012;307:1141–1142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sparling K. Windows to the world. 14 November 2012: Available from:http://www.animas.com/node/299?monyr=11&year=2012&pnum= 1 on 14 November 2014. 2014.

- 76.Head Rachel. (@rachelheadcde). “I look to the #DOC for firsthand perspectives of #PWD [people with diabetes]. Makes me a better person/CDE” 24 September 2014, 6:26 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 77.Laranjo L., Arguel A., Neves A.L., et al. The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015;22:243–256. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chang T., Chopra V., Zhang C., Woolford S.J. The role of social media in online weight management: A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15:e262. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salzer M.S., Palmer S.C., Kaplan K., et al. A randomized, controlled study of internet peer-to-peer interactions among women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:441–446. doi: 10.1002/pon.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Letorneau N., Stewart M., Masuda J.R., et al. Impact of online support for youth with asthma and allergies: Pilot study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012;27:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ruth D., Pfeffer J. Social media for large studies of behavior. Science. 2014;346:1063–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.346.6213.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu Y., Zhang P., Liu J., Li J., Deng S. Health-related hot topic detection in online communities using text clustering. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams SA, Terras M, Warwick C. How Twitter is studied in the medical professions: A classification of Twitter papers indexed in PubMed. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Zrebiec J.F. Internet communities: Do they improve coping with diabetes? Diabetes Educ. 2005;31:825–836. doi: 10.1177/0145721705282162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Heisler M. Overview of peer support models to improve diabetes self-management and clinical outcomes. Diabetes Spectr. 2007;20:214–221. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hong Y., Pena-Purcell N.C., Ory M.G. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012;86:288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Van Uden-Kraan C.F., Drossaer C.H., Taal E., Shaw B.R., Seydel E.R., van de Laar M.A. Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia. Qual. Health Res. 2008;18:405–417. doi: 10.1177/1049732307313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bartlett Y.K., Coulson N.S. An investigation into the empowerment effects of using online support groups and how this affects health professional/patient communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011;83:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vlasnik K. A minute. 6 October 2014: Available from: http://www.textingmypancreas.com/2014/10/a-minute.html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 90.Dunlap B. Who best to say, “You will be ok.” 15 February 2012: Available from: http://www.ydmv.net/2012/02/who-best-to-sayyou- will-be-okay.html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 91.Strange S. I saw children. 14 July 2011. Available from: http://strangelydiabetic.com/2011/07/14/i-saw-children/ on 21 November 2014. 2014.

- 92.Rechira S. July DSMA blog carnival – diabetes stigma. 20 July 2014. Available from:http://www.diabetesramblings.com/2014/07/july-dsma-blogcarnival- diabetes-stigma.html. on 21 November 2014. 2014.

- 93.Hoskins M. (@mhoskins2179). “I didn’t get into #DOC to advocate or “make a diff.” I found peeps & decided I had stuff to share”. 24 Septmeber 2014, 6:54 p.m. Tweet. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rawlings Kelly. (@kellyrawlings) “@MHoskins2179 Interesting point. That was my motivation, too, but have learned how to advocate and make a diff from the #doc” 24 September 2014, 6:56 p.m.Tweet. 2014.

- 95.Name No. (@type1type). “It’s liberating- putting your experiences out there. And more often than not, you’d hear from others who shared them, good and bad” 24 September 2014, 6:38 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 96.DePope (@leighanndepope). “I share my story online because I have no other outlet for it and can find others who relate.” 24 September 2014, 6:35 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 97.Graffeo K. Why write about diabetes? 4 April 2012. Available from: http://www.bittersweetdiabetes.com/2012/04/why-writeabout- diabetes.html. on 21 November 2014. 2014.

- 98.Sparling K. Power of patient communities. 16 December 2013. Available from: http://sixuntilme.com/wp/2013/12/16/powerpatient- communities/ on 21 November 2014. 2013.

- 99.Addington H. Addington H. Our CGM in the cloud experience: #wearenotwaiting. 14 August 2014: Availabile from:http://www.theprincessandthepump.com/2014/08/our-cgm-incloud- experience.html. on 13 November 2014. 2014.

- 100.No author name. First day of sixth grade #wearnotwaiting. 20 August 2014. Available from http://chasinglows.org/2014/08/20/first-day-of-the-sixth-gradewearenotwaiting/ on 21 November 2014. 2014.

- 101.No name. (@inspiredbyisa). “Be real. Share personal experiences. Listen to others without judging” 24 September 2014, 6:53 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 102.No name (@chasinglows). “Empathy should come first. We’re all in this together and all at different stages. Be patient” 24 September 2014, 6:53 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 103.No name. (@StephenSType1) “Don’t be afraid to tell your story. Someone is out there who needs to hear it” 24 September 2014, 6:50 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 104.No name. (@MNAZLaddie). “Give of yourself & you will receive. Ask for help & someday you will give help” 24 September 2014, 6:48 p.m. Tweet. 2014.

- 105. No name. (@diabetesheroes) “Keep your eyes, ears, and mind open to others. And also keep your fingers on the keyboard and add to the conversation” 24 September 2014, 6:48 p.m. Tweet.