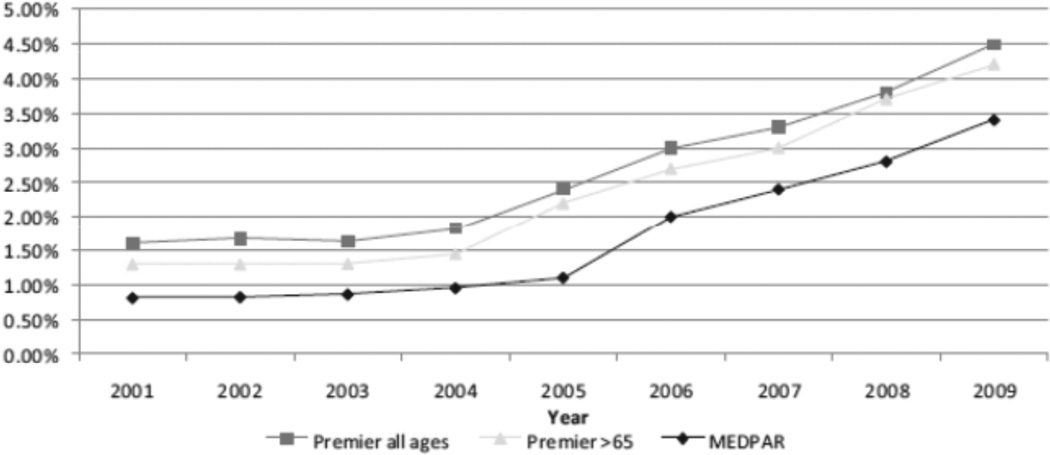

The benefit of intravenous rt-PA for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke is well-established.1, 2 Unfortunately, the rates of rt-PA utilization among U.S. ischemic stroke patients remain quite low. Previously, our group published the rate of rt-PA utilization among ischemic stroke patients within the large Premier database, which is a 15% sampling of U.S. hospitals that cross-references drug utilization with administrative data. The rate of rt-PA use was extremely low and did not increase from 2001 to 2004.3 This was despite rt-PA being approved for use in the U.S. since 1996. More recently, we found that the rates of rt-PA have begun to slowly increase from 1.4% in fiscal year (FY) 2001 to 4.5% in FY 2009 (Figure 1).4 The timing of this increase appeared to coincide with primary stroke center certification by the Joint Commission in the U.S. in 2004, although this is only an association rather than definitive causality. Rates of rt-PA use did not appear to be affected by increased reimbursement given to hospitals for care of rt-PA-treated patients (instituted in 2006), as we had originally hypothesized.

Figure 1.

National estimates of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rtPA) use in the US.

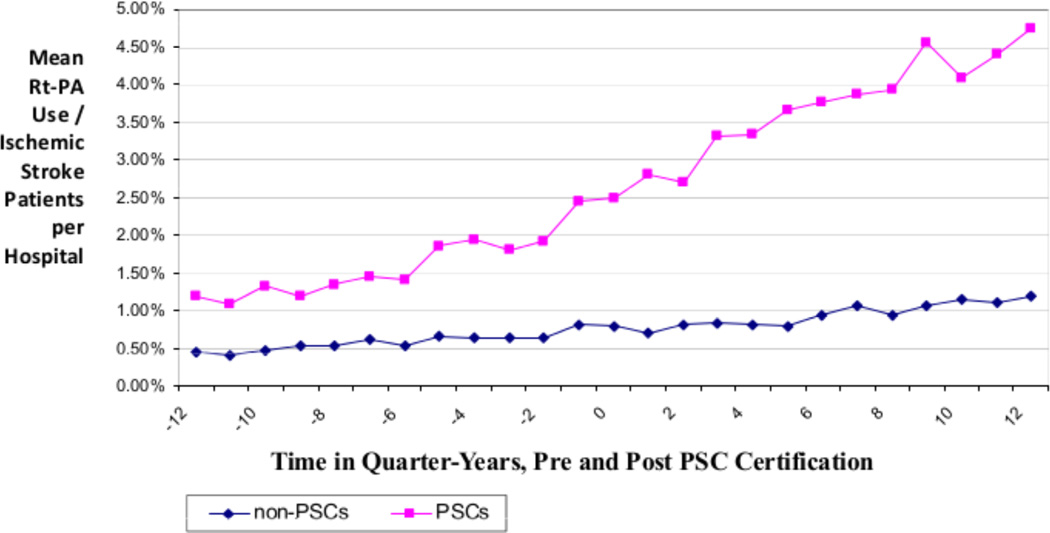

To further explore the impact of hospitals becoming certified as primary stroke centers, we utilized the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) database to evaluate rt-PA rates at the hospital-level. This database includes all fee-for-service hospitals in the U.S., and patients are included if they are Medicare-eligible (>65 years old or permanently disabled). Within this database, hospital characteristics associated with higher rates of rt-PA utilization included larger bed-size, urban location, and Northeast and West geographic location within the U.S. in FY 2009.5 We then compared rt-PA utilization between hospitals that became primary stroke centers during the study period of FY2006–2010 to those hospitals that were not certified. As expected, hospitals that became stroke centers had higher rates of rt-PA treatment than those who did not become certified (5.0% vs 1.4%) in FY 2010. Rates of treatment increased steadily during the three years before and the three years after certification (Figure 2).6

Figure 2.

Rt-PA Utilization Rates by Quarter, Pre- and Post Primary Stroke Center Certification, Compared to Non-Stroke Center Hospitals During the Same Timeframe (Ranging from FY2001–2010)

However, even with these substantial improvements in our systems of care, we are still not treating the vast majority of ischemic stroke patients with rt-PA. This is most certainly related to the eligibility of stroke patients for this acute reperfusion therapy. Within the large, bi-racial population of 1.3 million people in the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky (GCNK) region, only 8% of 2,308 ischemic stroke patients would have been eligible for IV rt-PA in 1994,7 applying AHA acute stroke management guideline criteria. The most common reason for exclusion from rt-PA was related to time from symptom onset to presentation, as only 23% of stroke patients arrived within three hours from symptom onset.8 This finding is very similar to many other large studies, as reviewed by Majersik et al.9 The other most common exclusion was mild symptom severity at presentation. The inclusion/exclusion criteria for rt-PA are currently being reviewed by stroke experts to verify if all are medically necessary and/or which criteria warrant further study. If some of these criteria were not required, it is possible that the percentage of eligible patients, and thereby the number of stroke patients receiving this therapy, would increase. For example, treating patients with mild stroke deficits could potentially at least double the rate of rt-PA use.10 However, further study is needed to determine the benefit of rt-PA within this population.

An exclusion criterion recently reconsidered was the extremely limited time window for giving lytic therapy. In 2008, the ECASS-III study successfully expanded the time window for acute treatment with thrombolytic therapy from 0–3 hours to 0–4.5 hours from symptom onset.2 This prompted the American Heart Association to publish an advisory statement recommending treatment in the expanded time window of 3–4.5 hours, in the setting of ECASS-III eligibility criteria (age <80, no oral anticoagulants regardless of serum coagulation testing, no patients with a history of both diabetes and a prior stroke, and NIHSSS must be < 25).11 This expanded time window within a population, however, leads to the disappointing finding that this expansion adds very few additional eligible stroke patients. In the GCNK population, the combination of the expanded time window for treatment, along with the additional ECASS III exclusion criteria, would have only led to an additional 0.6% more ischemic stroke patients becoming eligible for rt-PA in 2005.12 This is related to the bimodal distribution of times that ischemic stroke patients present to medical attention. Only 9% of all stroke patients arrive in the 3–8 hour time window.8 Stroke patients tend to arrive very early, or quite late. This finding has also been confirmed in other populations.9 Furthermore, the Federal Drug Administration denied approval of the expansion of the time-window for the approved uses of rt-PA, which may further minimize the impact of the expanded time window.

In summary, the rate of rt-PA use in ischemic stroke patients remains low in the U.S. This is most likely related to eligibility for thrombolytic therapy, especially the very short time window in which it can be given. Unfortunately, expanding the time window by a few hours does not appear to dramatically improve this eligibility. Rigorous study of other exclusion criteria are needed, such as mild stroke severity, as expansion of other criteria have the potential to dramatically increase thrombolytic therapy treatment rates and potentially improve long-term disability for stroke patients. At the hospital level, primary stroke center certification appears to have a powerful and sustained association with higher rates of rt-PA use, and further study of the impact of the newly-instituted comprehensive stroke center certification, and advances such as telemedicine, are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Disclosures:

Dawn Kleindorfer, MD: Genentech Speaker’s Bureau, Modest; NIH funded grant, significant.

Opeolu Adeoye, MD: NIH funded grants, significant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dawn Kleindorfer, Email: Dawn.kleindorfer@uc.edu.

Felipe de los Rios La Rosa, Email: delosrfe@ucmail.uc.edu.

Brett Kissela, Email: Brett.kissela@uc.edu.

Jason Mackey, Email: Jmackey3@iuhealth.org.

Opeolu Adeoye, Email: Opeolu.adeoye@uc.edu.

References

- 1.NINDS rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleindorfer DLC, White G, Curtis T, Brass L, Koroshetz W, Broderick JP. National us estimates of rt-pa use: Icd-9 codes substantially underestimate. Stroke. 2008;39:924–928. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adeoye O, Hornung R, Khatri P, Kleindorfer D. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator use for ischemic stroke in the united states: A doubling of treatment rates over the course of 5 years. Stroke. 2011;42:1952–1955. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleindorfer D, Xu Y, Moomaw CJ, Khatri P, Adeoye O, Hornung R. Us geographic distribution of rt-pa utilization by hospital for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:3580–3584. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleindorfer D, Mullen M, Hogan C, Adeoye O, Khatri P, Jauch E. Primary stroke center certification and its impact on thrombolysis use. Stroke abstract. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, Schneider A, Woo D, Khoury J, Miller R, et al. Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke: A population-based study. Stroke. 2004;35:e27–e29. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000109767.11426.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleindorfer DO, Broderick JP, Khoury J, Flaherty ML, Woo D, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, et al. Emergency department arrival times after acute ischemic stroke during the 1990s. Neurocrit Care. 2007;7:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s12028-007-0029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majersik JJ, Smith MA, Zahuranec DB, Sanchez BN, Morgenstern LB. Population-based analysis of the impact of expanding the time window for acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 2007;38:3213–3217. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatri PKJ, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Kissela BM, Woo D, Flaherty ML, et al. T Stroke and Cerebral Circulation, Los Angeles, CA (February 2011). He public health impact of an effective acute treatment for mild ischemic strokes. Stroke abstract. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Zoppo GJ, Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP., Jr Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator: A science advisory from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945–2948. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Los Rios la Rosa F, Khoury J, Kissela BM, Flaherty ML, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, et al. Eligibility for intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator within a population: The effect of the european cooperative acute stroke study (ecass) iii trial. Stroke. 2012;43:1591–1595. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.645986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.