Abstract

Objective

Little research has been done on alcohol use and dependence among rural residents in China, a sub-population that might be under increased stress due to the rapid modernization and urbanization processes. We aimed to assess rural residents’ levels of stress, negative emotions, resilience, alcohol use/dependence and the complex relationships among them.

Methods

Survey data from a large random sample (n = 1145, mean age = 35.9, SD = 7.7, 50.7% male) of rural residents in Wuhan, China were collected using Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview.

Results

The sample had high prevalence of frequently perceived stress (47%) and high prevalence of ever (54.4%), past 30-day (40.4%), and binge drinking (13.8%). Approximately 11% met the criterion for intermediate to severe alcohol dependence. Mediation analysis indicated that the association between perceived stress (predictor) and alcohol dependence (outcome) was fully mediated by anxiety (indirect effect = .203, p < .01) and depression (indict effect =.158, p < .05); moderation analysis indicated that association between stress and two negative emotions (mediators) was significantly modified by resilience (moderator); an integrative moderated mediation analysis indicated that the indirect effect from stress to alcohol dependence through negative emotions was also moderated by resilience.

Conclusions

Negative emotions play a key role in bridging stress and alcohol dependence, while resilience significantly buffers the impact of stress on depression, reducing the risk of alcohol dependence. Resilience training may be an effective component for alcohol intervention in rural China.

Keywords: alcohol dependence, resilience, negative emotions, mediated moderation, rural China

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Alcohol Use as a Growing Concern in Rural China

Alcohol use has increased dramatically in China since the 1980s, along with the country’s rapid economic growth (Li et al., 2015). Unlike in many developed countries where alcohol consumption showed a declining trend, China’s per capita alcohol use increased from 2.5L in 1978 to 6.7L in 2010 (Jiang et al., 2015). The consumption level equals 15.1L for those who actually drink, placing China the third on the alcohol consumption list in the world (after Tajikistan and Russia; WHO, 2014). High-risk drinking (e.g., binge drinking, heavy drinking) and alcohol use disorders (e.g., abuse and dependence) have reached epidemic proportions in China (Tang et al., 2013). Recent data indicate that rural residents in China are disproportionately represented in these problems. For example, one survey with a large sample (n=512,891, 56% rural residents) across various parts of China indicated that much higher prevalence of heavy drinking among rural Chinese than urban Chinese (46% vs. 29% for male, 31.1% vs. 21% for female) and rural residents consumed significantly larger amount of alcohol (333g vs. 238g per week for male, 150g vs. 68g for female; Millwood et al., 2013). In addition, rural residents, particularly males are twice as likely as to develop alcohol abuse and dependence disorders compared to their urban counterparts (Guo et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2009a).

1.2 Stress and Alcohol Use in Rural China: a Missing Link

Rural Chinese residents, totally 900 million, are an extremely understudied and underserved population with regard to alcohol use and prevention (Yang et al., 2009). Prior research has been focused on the levels of prevalence and pattern of alcohol use with some coverage of demographic correlates among rural Chinese (Baker et al., 2012; Hof et al., 2011; Millwood et al., 2013); few of them have investigated psychosocial determinants and potential mechanisms. Psychosocial stress has long been recognized as an important predictor for alcohol use and dependence (Adams et al., 2015). Rural Chinese are now facing a high and growing level of stress because of low income, little access to social welfare, and healthcare, and separation from key family members who have migrated to urban areas to work and earn money (Lu et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2009). So far, little empirical research has been done to examine the underlying mechanism of how stress is related to alcohol use in the rural Chinese population.

1.3 Stress, Negative Emotions, and Alcohol Dependence: a Mediation Pathway

Alcohol use is often considered as a maladaptive coping strategy for stress (Noori et al., 2014), and one potential factor bridging these two could be negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and depression). A mediation mechanism was proposed and tested with longitudinal data from a community sample in the United States showing that depression fully mediates the link between stress and later alcohol use (Barbosa-Leiker, 2014). Previous research has documented high levels of stress and high prevalence of mental health issues such as depression among rural Chinese (Lu et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). However, no study ever tested this mediation model to understand alcohol use among rural Chinese.

1.4 Potential Role of Resilience in Moderating the Association between Stress and Negative Emotion

Resilience, as the ability to adapt to stressful circumstances, has received much attention as a buffering mechanism for substance use and mental wellbeing (Prince-Embury and Saklofske, 2014). Previous studies have indicated a significant and negative association between resilience and alcohol use (Hof et al., 2011); but no reported study has examined whether and how resilience is related to alcohol use among rural Chinese residents. In theory, rural Chinese residents with higher levels of resilience may be able to better deal with a variety of stressful events than others, because research findings indicate a significant role of resilience in buffering the impact of daily stress (Bitsika et al., 2013), stressful life events (Peng et al., 2012), trauma (Roy et al., 2011), maltreatments (Goldstein et al., 2013), and violent events (Nrugham et al., 2010). Since resilience has been linked to reduced risk of alcohol use, it implies a moderated mediation mechanism in which resilience buffers the linkage between stress and negative emotions which mediate the association between stress and alcohol use and dependence. So far no reported study has tested this integrative moderated mediation hypothesis.

To bridge these knowledge gaps, we investigated the levels of stress, negative emotions, resilience, and alcohol use/dependence in a random sample of rural residents in China, and tested whether: (1) negative emotions mediate the link between stress and alcohol dependence; (2) resilience moderates the link between stress and negative emotions; (3) resilience serves as a buffering mechanism in the “stress-negative emotions-alcohol use” mediation pathway.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Participants and procedure

Participants included adult rural residents enrolled in the Migrant Health and Behavior Study, a study of rural-to-urban migrants, rural residents, and urban residents in Wuhan, China. The rural residents were randomly sampled with a novel GIS/GPS-assisted method from a belt region (width = 25 kilometers) surrounding the city (inner radius = 45km, outer radius = 70 km). These band strata were further divided into mutually exclusive geounits with the size 1km by 1km. A total of 40 geounits with 30 participants per geounit were sampled to obtain adequate sample size. Data were collected during 2011–2013. The Migrant Health and Behavior Questionnaire (MHBQ) (Chen et al., 2009a) was administered with Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI). Detailed sampling and survey method have been described elsewhere (Chen et al., 2015b). Among the 1,290 rural residents who completed the survey, 145 were excluded because they indicated in the end of the survey that their answers were “not reliable at all” or “mostly not reliable”, yielding a final sample of 1,145 for the analysis. A comparison between the 145 excluded participants and the remaining sample indicates no significant difference in demographic variables except a lower education level for those who indicated their answers as unreliable.

The survey protocol and the survey questionnaire were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Wuhan Center for Disease Prevention and Control and the Human Investigation Committee at Wayne State University; the use of the data was approved by IRB at the University of Florida.

2.2 Variables and Measurement

2.2.1 Alcohol use and dependence

Ever drinking was assessed by the question “Have you ever used any alcoholic beverage? (Yes/No)” For those who reported ever alcohol use, they were asked to also report: 1) age of initiation, assessed by the question “Please recall the first time you drank alcohol. How old were you at the time? (in years)”; 2) days used alcohol in the past month, assessed by the question “Please recall in the past month, on how many days did you use alcohol? (0–30 days)”; 3) number of drinks on a typical day, assessed by the question “On the days you drink in the past 30 days, on the average, how many drinks do you usually have on a day? (one drink equals one cup of liquor, two cups of wine, one can of beer)”; 4) days intoxicated in the past month, assessed by the question “On how many days in the past month were you drunk? (0–30 days)”; 5) binge drinking, assessed by the question “Please recall in the past month, on how many days did you engaged in binge drinking (binge drinking defined as consuming 5 or more drinks on the same occasion) (0–30days)”; 6) drinking related problems, assessed by the question “Please recall in the past year, did you experience any of the following as a result of drinking alcohol? a) got into quarrel with others, b) delayed work, c) failed a job, d) accidents, e) sickness”, and participants were asked to check all the problems that they experienced.

Alcohol dependence was measured using the 9-item Chinese version of Alcohol Dependence Scale (Chen et al., 2005), which is a short version of the original 25-item ADS (Skinner and Horn, 1984) validated in Chinese population. The Cronbach’s alpha was .81. Total scores were calculated such that larger scores indicating higher levels of alcohol dependence.

2.2.2 Stress

Global stress was the predictor variable. This variable was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983). This scale uses 10 items to measure the extent to which the participants felt situations in their daily life as stressful, unpredictable, and uncontrollable during the past month. An example item is: “In the past 30 days including today, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?” The scale was rated on a standard 5-point Likert rating scale from 1 (never) and 5 (always) and Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was .91 in current study. Mean scores were computed for analysis such that higher scores indicating higher levels of stress.

2.2.3 Negative emotions

Two negative emotions, anxiety and depression, were used as mediators. They were assessed with the Anxiety (6 items, α=.86) and the Depression subscales (5 items, α=.85) from the widely used Brief Symptoms Inventory (Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983). The standard five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) was used to assess individual negative emotions experienced in the past week (past seven days including today). Mean scores were computed for analysis such that higher scores indicate stronger negative emotions.

2.2.4 Resilience

Resilience was used as the moderator and it was measured using the Essential Resilience Scale (ERS; Chen et al., 2015a). This 15-item instrument was pilot-tested and validated in a diverse adult sample, including rural Chinese residents. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with a list of 15 items, on a five-point Likert scale varying from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A typical statement is: “I consider myself an emotionally ‘strong’ person”. The Cronbach’s alpha was .90. Mean scores were computed for analysis such that larger scores indicate higher levels of resilience.

2.2.5 Demographic variables

Age (in years), gender (male/female), ethnicity (Han/ minority ethnicity), marital status (married/ not married), education (elementary school or less, middle school, high school or more), engagement in farming (yes/no), annual income ($), and family size (number of persons: 1–2, 3, 4 or more) were included. These variables were used to describe the sample and some of them were used as covariates in the main analysis.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Two mediation models, one for anxiety and another for depression were used to test whether the two emotion measures mediated the association between stress and alcohol dependence. The mediation analysis was conducted following Baron and Kenny’s approach (Baron and Kenny, 1986). The significance of estimated indirect effects were assessed using the bootstrapping method (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). We used the predictor variable that measured stress in past month and the two mediator variables that measured the negative emotions in the past week to minimize potential reverse impact of negative emotions on stress.

Likewise, two moderation effect models, one for anxiety and another for depression were used to test the moderation effect of resilience on the link between stress and negative emotions. The interaction effect was probed using tools developed by Preacher and colleagues (Preacher et al., 2006). Third, based on the results from mediation and moderation analysis, two moderated mediation models were constructed to test the role of resilience in moderating the mediation effect of two negative emotions in the link between stress and alcohol dependence, following the approach by Preachers and colleagues (Preacher et al., 2007).

Both the mediation and moderated mediation analyses were conducted with the software SPSS version 22.0 (IMB Corp., 2013). The macro INDIRECT (Preacher and Hayes, 2008) was used for the mediation analysis and the macro MODMED (Preacher et al., 2007) was used for the moderated mediation analysis. The Johnson-Neyman technique was used to test the significance of the mediation effect. In all statistical analyses, type I error was set at p < .05 level (two-sided). Modeling analysis by gender was not pursued because of a lack of statistical power due to the low prevalence of females who had a non-zero score on alcohol dependence (11%). Instead, gender was included together with age and education as covariates in all main analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Sample Characteristics and Drinking Behaviors

Results in Table 1 indicate that among the 1145 participants, 50.7% were male, with a mean age of 35.9 (SD=7.7), 99.6% Han, 89.5% married, 71.5% with middle school or more education, and a mean family annual income between $1626 and $3250. Table 2 presents the drinking behavior patterns. 54.4% of the sample reported having used alcoholic beverage in their ever. Among these individuals, the mean age of their first drink was 19, and the average amount of drinks they had on a typical day were 115 ml alcoholic beverage. Overall, 20% of the participants were frequent drinkers (days used alcohol ≥ 10) (Weitzman et al., 2003) and 4% were frequently intoxicated (days intoxicated ≥ 3) (Kjaerulff et al., 2014). Moreover, 14% reported at least one binge drinking episode in the past month and 30% reported at least one drinking related problem such as got into quarrel with others in the past year.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample, by Gender

| Male (n=580) n (%) |

Female (n=565) n (%) |

Total (N=1145) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.1 (7.9) | 35.8 (7.5) | 35.9 (7.7) |

| 18–30 | 150 (25.9) | 147 (26.0) | 297 (25.9) |

| 31–40 | 202 (34.8) | 214 (37.9) | 416 (36.3) |

| 41–45 | 228 (39.3) | 204 (36.1) | 432 (37.7) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Han ethnicity | 579 (99.8) | 561 (99.3) | 1140 (99.6) |

| Minority ethnicity | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 488 (84.1) | 537 (95.0) | 1025 (89.5) |

| Not married | 92 (15.9) | 28 (5.0) | 120 (10.5) |

| Education | |||

| Elementary school | 91 (15.7) | 235 (41.6) | 326 (28.5) |

| Middle school | 349 (60.2) | 273 (48.3) | 622 (54.3) |

| High school or higher | 140 (24.1) | 57 (10.1) | 197 (17.2) |

| Engagement in farming | |||

| Yes | 260 (44.8) | 263 (46.5) | 523 (45.7) |

| No | 320 (55.2) | 302 (53.5) | 622 (54.3) |

| Annual income | |||

| ≤$1625 | 150 (25.9) | 172 (30.4) | 322 (28.1) |

| $1626-$3250 | 176 (30.3) | 180 (31.9) | 356 (31.1) |

| $3251-$6500 | 181 (31.2) | 171 (30.3) | 352 (30.7) |

| >$6500 | 73 (12.6) | 42 (7.4) | 115 (10.0) |

| Family size | |||

| 1 to 2 persons | 13 (2.2) | 7 (1.2) | 62 (11.0) |

| 3 persons | 132 (22.8) | 138 (24.4) | 318 (56.2) |

| 4 or more persons | 435 (75.0) | 420 (74.4) | 186 (32.9) |

Table 2.

Patterns of Alcohol Consumption, by Gender

| Male (n = 580) n(%) |

Female (n = 565) n(%) |

Total (N = 1145) n(%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever drinking | |||

| Yes | 465 (80.2) | 158 (28.0) | 623 (54.4) |

| Age of first drink | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17.9 (5.1) | 22.3 (8.2) | 19.0 (6.3) |

| Days used alcohol in the past month | |||

| None | 191 (32.9) | 491 (86.9) | 682 (59.6) |

| 1–10 days | 175 (30.2) | 62 (11.0) | 237 (20.7) |

| ≥ 10 days | 214 (36.9) | 12 (2.1) | 226 (19.7) |

| Number of drinks on a typical day | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.51 (3.95) | 1.26 (1.30) | 2.31 (3.69) |

| Days intoxicated in past month | |||

| None | 484 (83.5) | 550 (97.3) | 1034 (90.3) |

| 1–2 days | 53 (9.1) | 9 (1.6) | 62 (5.4) |

| ≥ 3 days | 43 (7.4) | 6 (1.1) | 49 (4.3) |

| Binge drinking in past month | |||

| Yes | 143 (25.7) | 15 (2.7) | 158 (13.8) |

| Drinking related problem last year | |||

| Yes | 277 (48.8) | 69 (12.2) | 346 (30.2) |

| Alcohol dependence score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.86 (2.61) | 2.58 (1.79) | 3.67 (2.54) |

Note. Age of first drink, number of drinks on a typical day, and alcohol dependence score were computed only using data from those who reported ever drinking. Number of drinks on a typical day is measured using “liang” as the unit size for alcoholic beverage (1 liang = 50ml).

3.2 Correlational Analysis

Results from bivariate correlational analysis indicate that perceived stress was positively associated with both anxiety (r = .59, p < .001) and depression (r = .56, p < .001); while the two negative emotions were positively associated with alcohol dependence (r = .08, p < .01 for anxiety; r = .09, p < .01 for depression). In addition, resilience was negatively associated with anxiety (r = −.10, p < .001) and depression (r = −.12, p < .001). Age, gender, and education level were also correlated with certain variables (Table 3). No significant differences in stress and the outcomes variables were found between farmers and non-farmers or by family sizes. These results support further test of mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation models, while controlling for age, gender, and education.

Table 3.

Key Variables and Pearson Correlation Coefficients, N = 1145

| Variables | Mean(SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Stress | 2.50 (0.64) | - | ||||||

| 2 Anxiety | 1.92 (0.64) | .59*** | - | |||||

| 3 Depression | 1.97 (0.72) | .56*** | .78** | - | ||||

| 4 Resilience | 3.44 (0.65) | −.03 | −.10*** | −.12*** | - | |||

| 5 Alcohol dependence score | 0.62 (2.79) | .06 | .08** | .09** | −.08** | - | ||

| 6 Age | 35.95 (7.71) | −.05 | −.01 | −.03 | .19*** | .06 | - | |

| 7 Gender | - | −.07* | −.08** | −.02 | −.02 | .44*** | .02 | - |

| 8 Education | 1.90 (0.71) | .02 | .02 | .04 | −.09** | .19*** | −.24*** | .30*** |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

For gender: 0 = female, 1 = male.

3.3 Mediation Analysis

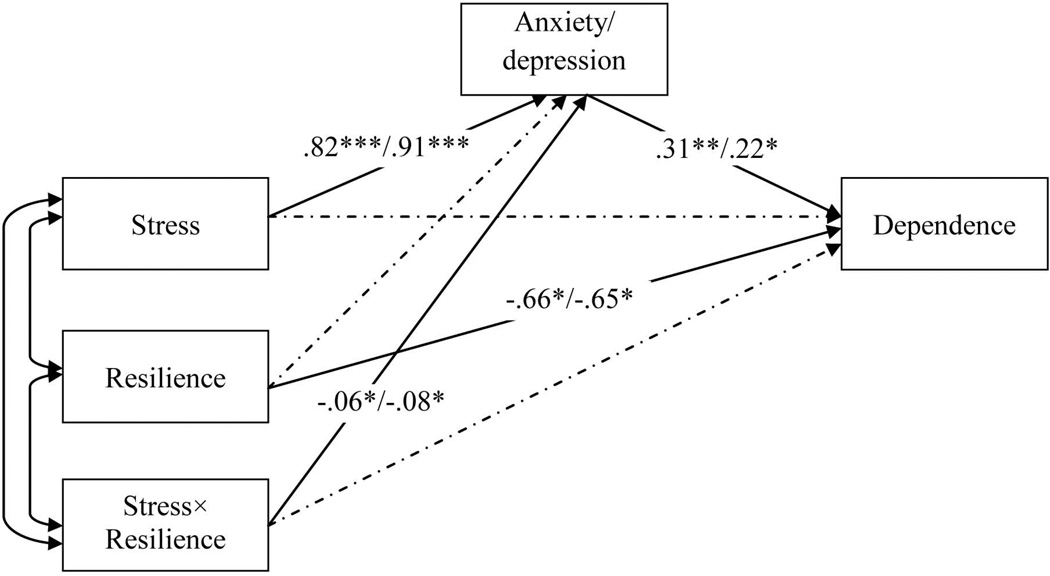

Results presented in Figure 1 indicate significant indirect effects of anxiety and depression in mediating the association between perceived stress and alcohol dependence (effect = .203 for anxiety, p < .01; and .158 for depression, p < .05). The direct effect of stress on alcohol dependence was not significant after the mediation (c’ = .13, p = ns for anxiety; and c’ = .17, p = ns for depression), indicating a full mediation of the negative emotions.

Figure 1.

Negative emotions mediate the relationship between stress and alcohol dependence

Note. Solid lines represent statistically significant paths. Dotted lines represent nonsignificant paths. Indirect effects were .203 (95% CI [.057, .357]) and .158 (95% CI [.032, .269]) for anxiety and depression respectively. Path coefficients to the left of the “/” were for analysis using anxiety as mediator. Path coefficients to the right of the “/” were for analysis using depression as mediator. Age, gender, and education were entered as covariates in all analyses. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

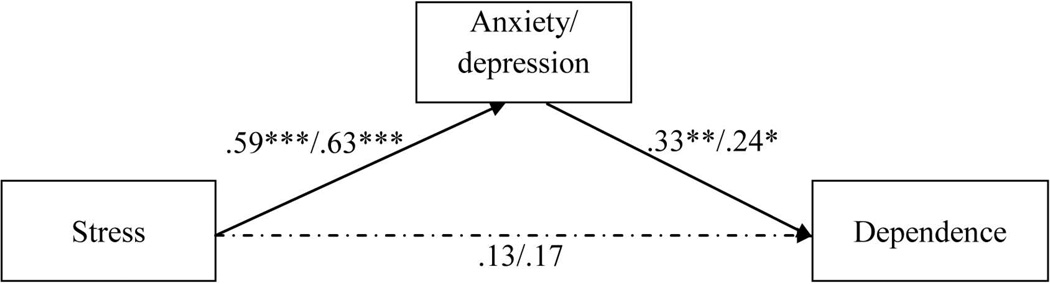

3.4 Moderation Analysis

Results from the moderation analysis using least ordinary squares regression indicate a significant interaction between stress and resilience in predicting negative emotions (beta = −.065, p < .05 for anxiety; and beta = −.079, p < .05 for depression). To further examine the changes of relationship between stress and negative emotions with the increase of resilience levels, simple slopes were calculated using the “pick-a-point” approach (Preacher et al., 2006). Sample mean, two standard deviations below and above mean were chosen to represent “moderate”, “low”, and “high” levels of resilience, respectively. Results indicate that as resilience levels increased, the effect of stress on negative emotions decreased: for anxiety, the simple slopes were .68, .60, and .52 (p’s <.001) at low, moderate, and high levels of resilience; for depression, the simple slopes were .73, .63, and .53 (p’s <.001) at low, moderate, and high levels of resilience. Figure 2 illustrates the different slopes associated with different resilience levels.

Figure 2.

Resilience moderates the effect of stress on anxiety and depression.

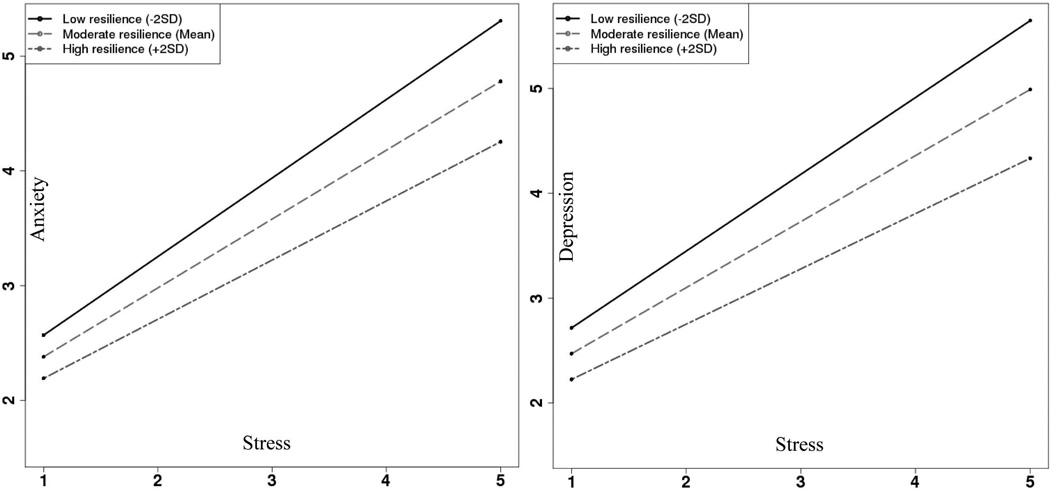

3.5 Moderated Mediation Analysis

Figure 3 presents the results of the moderated mediation analysis where resilience was introduced as the moderator between stress and negative emotions. The figure shows that in addition to the significant mediational pathways from stress to alcohol dependence through anxiety and depression, the interaction term (stress×resilience) was also significant, which means resilience significantly moderated the association between stress and the two negative emotions. Moreover, because the mediation effect of anxiety/depression is the product of the path coefficient from stress to anxiety/depression (often referred to as path “a”) and the path coefficient from anxiety/depression to alcohol dependence (often referred to as path “b”), the mediation effect (a×b) was also moderated by resilience. The Johnson-Neyman test indicates that the indirect effects of stress on alcohol dependence through the two negative emotions were significant across the levels of resilience but decreased with the increase of resilience scores.

Figure 3.

Moderated mediation model of alcohol dependence

Note. Solid lines represent statistically significant paths. Dotted lines represent nonsignificant paths. Path coefficients were labeled for statistically significant paths only. Path coefficients to the left of the “/” were for analysis using anxiety as mediator. Path coefficients to the right of the “/” were for analysis using depression as mediator. Age, gender, and education were entered as covariates in all analyses. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

4. DISCUSSION

Despite the large population size and high prevalence of alcohol use problems, rural residents in China remain an extremely understudied population (Yang et al., 2009). As an effort to disentangle the complex relationship of how various risk and protective factors interactively influence alcohol use among rural Chinese residents, we tested a moderated mediation model on whether resilience buffers the impact of stress on negative emotions and in turn reduces alcohol dependence. Our data were collected from a large sample of rural residents in China with an advanced multi-stage random sampling strategy and the use of Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI). All the measures used in this study were validated in Chinese populations and had satisfactory reliability. The advanced moderated mediation analysis approach (Preacher et al., 2007) was used to test the hypotheses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on the underlying mechanisms of alcohol dependence among rural Chinese residents.

4.1 Stress and Alcohol Use in Rural China

Results of our study indicate that stress is prevalent among rural residents in China1, with 47% of the participants reported perceiving stress frequently (more than several times in the past month). This number is in line with a previous study, which also found high prevalence of severe stress (45%) among rural Chinese males (Yang et al., 2009). Alcohol dependence2 was also highly prevalent (10.7%) in current sample. This number is higher than previously reported by other studies. For example, one study reported 4.7–8.7% of alcohol dependence (based on DSM-IV criteria) among a large sample of rural Chinese males (n = 9866; Zhou et al., 2009b). The discrepancy could be attributed to the regional differences in alcohol use that’s been widely acknowledged (Millwood et al., 2013). It should also be noted that the prevalence rates may differ based on ADS in comparison to DSM-IV.

4.2 Negative Emotions as the Underlying Mechanism for the Stress-Alcohol Link

Despite the coexistence of high stress and alcohol dependence, our results indicate no direct link between these two variables. Two negative emotions including anxiety and depression fully mediated the relationship between stress and alcohol dependence. This finding is in line with a recent longitudinal study (Barbosa-Leiker, 2014), which found that psychological stress predicts depression, which in turn predicts later alcohol use. Theoretically, this finding may be explained by the desregulation of brain’s stress system and establishment of an allostatic state with drug use as the reward function (Koob and Kreek, 2007; Koob, 2008; Kreek and Koob, 1998). Alcohol dependence, therefore, can be understood as a compulsive disorder which is characterized by preceding stress, anxiety and depression, and the consequent relief from such emotional problems by repetitive use of alcohol (Koob and Kreek, 2007).

This mediation mechanism helps explain the frequently observed co-morbidity of anxiety, depression and alcohol use (Baker et al., 2012; Hussong et al., 2011). This finding also adds empirical support for the incorporation of psychological and behavioral components addressing stress and/or negative emotions in alcohol intervention programs (Baker et al., 2012). However, despite the prevalence of psychological interventions in substance use intervention programs, the effectiveness of most commonly used psychological treatments to alleviate negative emotions (e.g., antidepressant counseling or medication) or reduce stress (e.g., stress management) are proved to be only small to moderate (Baker et al., 2012). Therefore, the mediation mechanism by itself provides limited information for advancing alcohol interventions.

4.3 Resilience Training as a Potential Intervention Component

One unique contribution of the current study is identifying the moderator that can help break the mediation pathway from stress to alcohol use, which suggests a new way to intervene and reduce alcohol dependence—resilience training. Resilience as the ability to adapt to stressful circumstances (Prince-Embury and Saklofske, 2014) has been extensively researched as a way to understand and prevent the development of psychopathology including anxiety and depression (Masten, 2011). Previous resilience research indicates that not all children grown up in adversity develop psychopathology (Masten, 2011); similarly, not all adults facing stress develop mental health problems (Cleverley and Kidd, 2010; Geschwind et al., 2010). Stress in life is inevitable, but how “resilient” each individual is holds the key to explain the individual differences in psychological and behavioral outcomes under stress (Prince-Embury and Saklofske, 2014). Three components of resilience are considered essential: anticipation, flexibility, and bounce-back (Chen et al., 2015a). Highly resilient individuals (1) can anticipate adverse or stressful events before they occurs and be well prepared to deal with them; (2) are more flexible and have the ability to buffer the impact of adverse or stressful events without significant maladjustment; and (3) can recover (bounce-back) quickly and adequately from the adverse or stressful impact (Chen et al., 2015a).

One promising feature of resilience is that it can be improved by active learning and purposeful training (Sood et al., 2011). Resilience enhancement programs are available for health promotion (Prince-Embury and Saklofske, 2014; Sood et al., 2011), but few have been used for alcohol intervention purposes. Our findings provide empirical evidence supporting the potentials to adapt existing resilience training programs or devise new programs for alcohol intervention purposes. Currently, there is a lack of evidence-based alcohol intervention programs in China (Guo and Huang, 2015). The significant barriers not only include the dearth of empirical data supporting the development of such intervention programs, but also the low availability of rural residents’ access to public healthcare resources (Chen et al., 2009b; Wu et al., 2008). The findings of current study bridges the data gap and suggest the potential success of resilience training as a cost-effective intervention for alcohol use and dependence in rural China.

4.4 Limitations

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. First, the data is cross-sectional and thus could not rule out the reverse causality that alcohol dependence may cause more anxiety and depression. However, the mediation relation from stress to negative emotions and then alcohol dependence was based on extensive literature including developmental theory (Hussong et al., 2011) and longitudinal data support (Barbosa-Leiker, 2014). Therefore, despite the cross-sectional nature of the data, the moderated mediation relationship discovered in this study is highly reliable. Nevertheless, future longitudinal research is suggested to further validate the findings. Second, this study only sampled rural adults from one city (Wuhan) in China, and thus has limited generalizability. For example, the specific eating habits of rural residents in Wuhan may have some influence on their drinking behaviors. Future research is needed to test whether the same mechanism applies to other populations including residents from other places in China and across the globe. Third, this study used self-report data obtained from ACASI, which may be subjected to self-report bias (e.g., underreporting due to social desirability). However, literature suggests that self-report data are usually reliable and valid for drug use studies (Del Boca and Darkes, 2003), and ACASIs often obtain more accurate reports than other methods especially for sensitive questions such as drug use and sexual behaviors (Morrison-Beedy et al., 2006). Fourth, this study only included personal level factors whereas more social level predictors may also influence alcohol use and dependence. Future studies would benefit from considering the sociocultural factors such as cultural norms regarding alcohol use in predicting alcohol use among Chinese populations. Also, in this study we elected to use the previously validated brief Chinese version of ADS as an effort to minimize cultural equivalence issue in the measurement (Prince, 2008). However, this scale is less widely used compared to ICD-10 or DSM-IV, which increases the difficulty to compare our prevalence rates to other large-scale studies. Lastly, this study only obtained participants’ subjective report of their resilience level, which may be subjected to self-report bias. Future study may be benefited from using experimental design to test participants’ ability to adapt to real stressful circumstances for a more objective evaluation of resilience.

4.5 Conclusions

Despite the limitations, this study represents an important step toward a better understanding of the psychosocial mechanism underlying the increased alcohol use among rural Chinese residents. Findings of our study provide information not only on the etiology of how stress leads to alcohol dependence, but also the protective mechanism of how resilience can buffer the impact of stress on negative emotions and in turn reduce alcohol use. Considering the high levels of stress and alcohol use and limited healthcare resources in rural China, our findings suggest the potential success of resilience training as a more feasible and effective alcohol intervention strategy.

Highlights.

We focus on an understudied population with increased alcohol use problems.

Stress, negative emotions, resilience, and alcohol dependence were examined.

Negative emotions fully mediate the link between stress and alcohol dependence.

Resilience buffers the impact of stress on negative emotions then alcohol use.

Resilience training may be an effective alcohol intervention method.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to those who participated in data collection and data processing.

Role of Funding Source

This study was supported through a research grant from the National Institutes of Health (Award #: R01 MH086322).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Because we used a random sample of generally healthy adults, the average score of the stress level of this sample was similar to that reported by previous research using large-scale random sample in China (t = 11.4, df = 1148, p = ns, based on mean, SD, and sample size extracted from the published paper) (Yang, T., Huang, H., 2003. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 24, 760–764.)

Based on the criteria provided by the original ADS (Skinner, H.A., Horn, J.L., 1984. Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS): User’s Guide. Addiction Research Foundation, Toronto, Canada.), a proportionately weighted cut-off point (total score ≥ 5) based on the ranges of possible scores was calculated to indicate alcohol dependence for the brief 9-item Chinese version of ADS we used for this study.

It should be noted that although some correlations were statistically significant, their effect sizes were relatively small.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared.

Contributors

Yan Wang: conceived the paper idea, analyzed the data, and lead the writing of the paper Xinguang Chen: contributed to the paper idea, led the data collection, and revised the paper

REFERENCES

- Adams CE, Cano MA, Heppner WL, Stewart DW, Correa-Fernandez V, Vidrine JI, Li YS, Cinciripini PM, Ahluwalia JS, Wetter DW. Testing a moderated mediation model of mindfulness, psychosocial stress, and alcohol use among African American smokers. Mindfulness. 2015;6:315–325. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AL, Thornton LK, Hiles S, Hides L, Lubman DI. Psychological interventions for alcohol misuse among people with co-occurring depression or anxiety disorders: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;139:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Leiker C. Depression as a mediator in the longitudinal relationship between psychological stress and alcohol use. J. Subst. Use. 2014;19:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological-research - conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsika V, Sharpley CF, Bell R. The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2013;25:533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Gong J, Fang X, Li X. Personal Social Capital Scale: an instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Educ. Res. 2009a;24:306–317. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Tang X, Li X, Stanton B, Li W. Use of the Alcohol Dependence Scale among drinkers from a survey sample in China. Alcohol Res. 2005;10:237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wang Y, Yan Y. Development of the Essential Resilience Scale (ERS): definition, concept mapping, and psychometric assessment (under review) 2015a [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yu B, Zhou D, Zhou W, Gong J, Li S, Stanton B. Men who have sex with men among rural-to-urban migrants and non-migrant rural and urban residents in China: a GIS/GPS-assisted random sample survey (under review) 2015b doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XG, Stanton B, Li XM, Fang XY, Lin DH, Xiong Q. A comparison of health-risk behaviors of rural migrants with rural residents and urban residents in China. Am. J. Health Behav. 2009b;33:15–25. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleverley K, Kidd SA. Resilience and suicidality among homeless youth. J. Adolesc. 2010;34:1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;2(98 Suppl.):1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory - an introductory report. Psychol. Med. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geschwind N, Peeters F, Jacobs N, Delespaul P, Derom C, Thiery E, van Os J, Wichers M. Meeting risk with resilience: high daily life reward experience preserves mental health. Acta Psychiat. Scand. 2010;122:129–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Faulkner B, Wekerle C. The relationship among internal resilience, smoking, alcohol use, and depression symptoms in emerging adults transitioning out of child welfare. Child Abuse Neglect. 2013;37:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W-J, Xu X-F, Lee S. More alcohol dependence than abuse in rural China. Addiction. 2009;104:2118–2119. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Huang Y-g. The development of alcohol policy in contemporary China. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof DD, Johnson N, Dinsmore JA. The relationship between college students’ resilience level and type of alcohol use. Tarptautinis psichologijos žurnalas: Biopsichosocialinis požiūris. 2011:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Jones DJ, Stein GL, Baucom DH, Boeding S. An internalizing pathway to alcohol use and disorder. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011;25:390–404. doi: 10.1037/a0024519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Room R, Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China: action needed. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e190–e191. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff TM, Rivera F, Jimenez-Iglesias A, Moreno C. perceived quality of social relations and frequent drunkenness: a cross-sectional study of Spanish adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:466–471. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1149–1159. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. A role for brain stress systems in addiction. Neuron. 2008;59:11–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Koob GF. Drug dependence: stress and dysregulation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:23–47. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Babor TF, Zeigler D, Xuan ZM, Morisky D, Hovell MF, Nelson TF, Shen WX, Li B. Health promotion interventions and policies addressing excessive alcohol use: a systematic review of national and global evidence as a guide to health-care reform in China. Addiction. 2015;110:68–78. doi: 10.1111/add.12784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Hu PF, Treiman DJ. Migration and depressive symptoms in migrant-sending areas: findings from the survey of internal migration and health in China. Int. J. Public Health. 2012;57:691–698. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Xiang YT, Cai ZJ, Li SR, Xiang YQ, Guo HL, Hou YZ, Li ZB, Li ZJ, Tao YF, Dang WM, Wu XM, Deng J, Wang CY, Lai KY, Ungvari GS. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of major depressive episode in rural and urban areas of Beijing, China. J. Affect. Disord. 2009;115:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Dev. Psychopathol. 2011;23:493–506. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millwood IY, Li LM, Smith M, Guo Y, Yang L, Bian Z, Lewington S, Whitlock G, Sherliker P, Collins R, Chen JS, Peto R, Wang HM, Xu JJ, He J, Yu M, Liu HL, Chen ZM, Collaborati CKB. Alcohol consumption in 0.5 million people from 10 diverse regions of China: prevalence, patterns and socio-demographic and health-related correlates. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:816–827. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noori HR, Helinski S, Spanagel R. Cluster and meta-analyses on factors influencing stress-induced alcohol drinking and relapse in rodents. Addict. Biol. 2014;19:225–232. doi: 10.1111/adb.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nrugham L, Holen A, Sund AM. Associations between attempted suicide, violent life events, depressive symptoms, and resilience in adolescents and young adults. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010;198:131–136. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Zhang JJ, Li M, Li PP, Zhang Y, Zuo X, Miao Y, Xu Y. Negative life events and mental health of Chinese medical students: the effect of resilience, personality and social support. Psychiatr. Res. 2012;196:138–141. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav. Res. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince-Embury S, Saklofske DH, editors. Resilience Interventions For Youth In Diverse Populations. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. Measurement validity in cross-cultural comparative research. Epidemiol. Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17:211–220. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Carli V, Sarchiapone M. Resilience mitigates the suicide risk associated with childhood trauma. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;133:591–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS): User’s Guide. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sood A, Prasad K, Schroeder D, Varkey P. Stress management and resilience training among department of medicine faculty: a pilot randomized clinical trial. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2011;26:856–861. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1640-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YL, Xiang XJ, Wang XY, Cubells JF, Babor TF, Hao W. Alcohol and alcohol-related harm in China: policy changes needed. B World Health Organ. 2013;91:270–276. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.107318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman ER, Folkman A, Folkman MPHKL, Wechsler H. The relationship of alcohol outlet density to heavy and frequent drinking and drinking-related problems among college students at eight universities. Health Place. 2003;9:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(02)00014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/. accessed on April 23 2015>. [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Mao ZF, Rockett IRH, Yue Y. Socioeconomic status and alcohol use among urban and rural residents in China. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43:952–966. doi: 10.1080/10826080701204961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Huang H. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2003;24:760–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Rockett IRH, Yang X, Xu X. Patterns and correlates of stress among rural Chinese males: a four-region study. Public Health. 2009;123:694–698. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Conner KR, Phillips MR, Caine ED, Xiao S, Zhang R, Gong Y. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse and dependence in rural chinese men. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009a;33:1770–1776. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Phillips MR, Conner KR. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse and dependence in rural Chinese men. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009b;33:65a–65a. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]