Abstract

Head and neck cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide. It is often amenable to curative intent therapy when localized to the head and neck region, but it carries a poor prognosis when it is recurrent or metastatic. Therefore, initial treatment decisions are critical to improve patient survival. However, multimodality therapy used with curative intent is toxic. The balance between offering intensive versus tolerable and function-preserving therapy has been thrown into sharp relief with the recently described epidemic of human papillomavirus–associated head and neck squamous cell carcinomas characterized by improved clinical outcomes compared with smoking-associated head and neck tumors. Model systems and clinical trials have been slow to address the clinical questions that face the field to date. With this as a background, a host of translational studies have recently reported the somatic alterations in head and neck cancer and have highlighted the distinct genetic and biologic differences between viral and tobacco-associated tumors. This review seeks to summarize the main findings of studies, including The Cancer Genome Atlas, for the clinician scientist, with a goal of leveraging this new knowledge toward the betterment of patients with head and neck cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the fifth most common nonskin cancer worldwide; the annual incidence is 600,000 cases, and 50,000 cases are diagnosed annually in the United States.1,2 Although HNSCC historically was viewed as a tobacco- and alcohol-related cancer, infection with high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs) during the past decade has emerged as a risk factor for a substantial fraction of HNSCCs.3 The so-called HPV epidemic is most prominent in patients of Northern European and North American origin, whereas other areas of the world still see few HPV-associated tumors.4–6 In studies that include an assessment of HPV status, a shift in the traditional risk factors is nearly universally noted: viral-associated tumors are seen in younger populations that have lymph node–positive oropharyngeal carcinomas and lower rates of smoking.7 Having said this, most patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal carcinoma are still men in their 50s who have a smoking history, and true nonsmokers constitute only a minority.1,3,8–10 Unfortunately, a precise characterization of patients with HNSCC by HPV status is challenging. First, because HPV is not yet part of the staging system in HNSCC, tumor registries, such as the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, do not routinely record it. Adding to the knowledge gap is a lack of consensus of diagnostic reagents to detect HPV. Variability in the assays used across studies limits generalizability and comparability of results.11,12

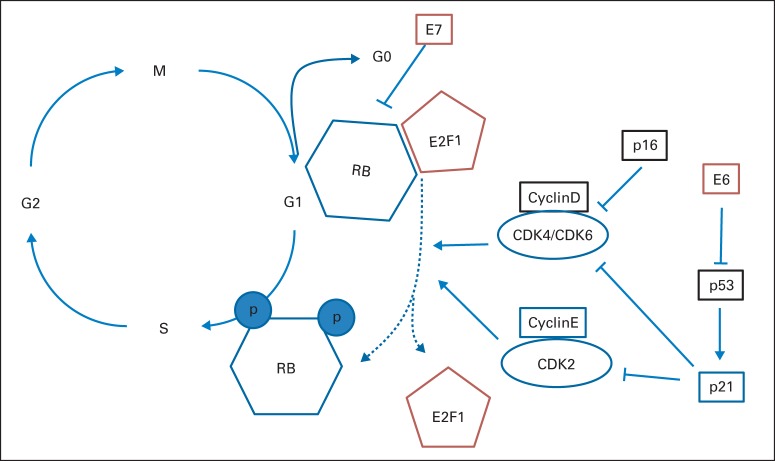

Although morphologic characteristics, such as basal squamous histology, poor differentiation, and absent keratin formation, are associated with HPV infection, the diagnosis of HPV is made through molecular testing. A mystery of the disease is that no precursor lesion on which to screen patients during the long latency has been reported, despite the assumption that viral exposure occurs via sexual contact in young adulthood. Screening HPV molecular assays, including polymerase chain reaction–based techniques, risk false-positive detection of endemic viral infections not associated with cancer, whereas specific in situ hybridization (ISH) assays often have lower sensitivity.13 A useful proxy for HPV infection in tumors is by immunohistochemistry (IHC) assessment of p16, the protein product of the gene CDKN2A.14 As shown in Figure 1, p16 is a repressor of the D cyclins that, in turn, partially phosphorylate the retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor protein (RB1). In the setting of viral infection, expression of the E7 viral oncoprotein mediates degradation of RB1, and pathway feedback results in overexpression of the cell senescence pathways, including p16.15 The detection of p16 is a proxy for RB1 loss through any mechanism, including mutations of RB1 that are not mediated by E7 or HPV. Therefore, p16 detection can result in the false assumption that E7 is expressed and, by extension, that the tumor is HPV positive.16 For instances of high pretest probability for HPV, such as in squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx, the true-positive rate for p16 as an indication of HPV is high.14 When the pretest probability is lower, such as in the oral cavity, the true-positive rate decreases to 10%-41%, which renders p16 IHC an ineffective diagnostic tool. If it is assumed that 5% of nonoropharynx tumors are HPV positive, as many as 1,500 cases per year outside the oropharynx may be difficult to assess with p16. Ultimately, direct tests of E6 and E7 may prove superior, but these are not yet routine.17

Fig 1.

Role of E6 and E7 in the cell cycle pathways and gene alterations as a function of human papillomavirius (HPV) tumor status. Genes altered in HPV-positive or viral oncogenes (red) or in HPV-negative tumors (black). RB, retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor protein.

Although the demographic shifts may be modest between patients who are HPV positive and HPV negative, clinical outcomes are dramatically different. Although patients with HPV commonly present with advanced nodal disease and clinical stage, prognosis is favorable compared with patients without HPV.3 Improved outcomes are seen across treatment modalities, including chemotherapy, radiation, chemoradiotherapy, and potentially also surgery, which have led to proposals to incorporate HPV status in staging.9 Although outcomes are better, the implications for selection of patient therapy by HPV status are not yet clear, because few existing clinical trials assessed HPV status.18–20 Controversies are most pronounced in molecularly targeted therapy, for which little conclusive published data exist, although retrospective studies have been presented in scientific meetings. Two randomized, phase III studies that used anti–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy either combined with chemotherapy or as a single agent versus methotrexate suggest less activity of EGFR agents in p16-positive tumors.21,22 An additional phase II study indicated a 0% response rate for single-agent anti-EGFR therapy in HPV-associated HNSCC according to highly accurate E6/E7 RNA-based HPV testing.23 Conversely, in the EXTREME (Erbitux in First-Line Treatment of Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer) study, a nonsignificant trend toward benefit in patients who were positive by p16 and/or ISH was seen, although analysis was limited because of small numbers and the use of p16 IHC for nonoropharynx tumors.24 The phase III trial of cetuximab in combination with radiation favored outcomes in patients with oropharynx tumors in the cetuximab treatment arm.18 In a retrospective subset analysis, patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharynx tumors benefited from cetuximab.25 However, analysis that used HPV nucleic acid testing by ISH did not show a clear benefit, which suggests that p16 expression, rather than HPV status, may be important. In short, controversy remains as to whether the combination of cetuximab with radiation seems to benefit patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. By contrast, the data are stronger that patients who are p16 positive for HPV may benefit, although such patients include some HPV-negative, yet p16-positive, tumors. At a molecular level, published studies suggest an anticorrelation between staining for the EGFR receptor and benefit of cetuximab.20 HPV-positive tumors have generally shown low or absent levels of EGFR protein expression or EGFR gene amplification.1,10 Unfortunately, preclinical models fail to clarify the picture, because HPV-positive cell lines of HNSCC remain in early development. Ongoing trials, such as Radiation Therapy Oncology Group study RTOG 1016 (NCT01302834), may clarify some controversies about cetuximab. Other studies leverage the dramatically improved outcomes for patients with HPV-positive tumors by de-escalating therapy and potentially decreasing toxicity.26

In parallel with lessons learned by clinical trials, rapidly emerging advances in tumor characterization, including DNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, miRNA characterization, epigenetic characterization, and proteomics, are in sight and have been widely reviewed elsewhere.1,27–34 Data from large cooperative endeavors, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and individual efforts, such as the Chicago HNC Genomics cohorts, have illuminated the genome of HNSCC in a manner that reveals the most commonly altered genes and coordinated patterns of genome alteration, which could be leveraged to accelerate our understanding of the disease, improve personalization of existing therapies to increase effectiveness, and propose accelerated strategies for novel therapeutics.1,10

STRUCTURAL ALTERATIONS

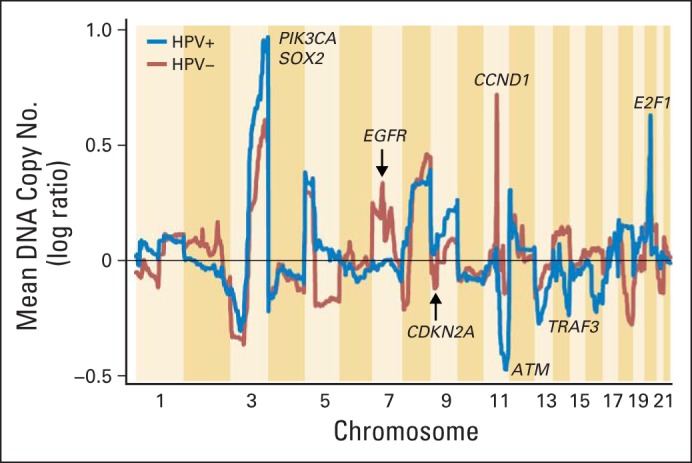

Several publications have reported the copy number landscape of HPV-positive versus HPV-negative HNSCC (Fig 2).1,27–35 Across much of the genome, the copy number alterations from HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors are highly concordant, and shared amplifications are 1q, 3q, 5p, 8q, and others. Common deletions include 3p, 5q, 11q, and others. In some instances, comparison of altered regions across studies is challenging because of the small number of patients who are HPV positive. Although many regions are clearly shared, others are strikingly divergent. Recently, a region on chromosome 14q32 was reported showing deep deletions in HPV-positive tumors and few, if any, deletions in HPV-negative tumors.1 Focal deletions, which include homozygous deletions, are relatively rare in a cancer genome and, when recurrent, are often suggestive of key novel tumor-suppressor genes. In combination with sequencing data, homozygous deletions noted in the TCGA study identified that the tumor-suppressor gene TRAF3 was inactivated in approximately 20% of HPV-positive tumors; this inactivation had been previously unrecognized in HNSCC, although TRAF3 loss had been seen in nasopharyngeal carcinoma.1,36 TRAF3 is implicated in innate interferon and acquired antiviral responses, including in Epstein-Barr virus, HPV, and HIV.37–40 TRAF3 also serves as a ubiquitin ligase and negative regulator for nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) –inducing kinase, a critical signal component in activation of transcription factors, which are implicated in cell survival and other features of the malignant phenotype.38

Fig 2.

Copy number alterations by chromosome position in human papillomavirus (HPV) –positive and HPV-negative tumors.

A second deletion that presents more prominently in patients with HPV-positive tumors occurs in chromosome 11q. Although the deletion occurs in a broad region, which makes a single gene target difficult to identify, several prominent tumor-suppressor genes are suggested, including ATM1. In terms of broad and focal amplification, perhaps the most prominent difference occurs on chromosome 7, where HPV-positive tumors exhibit no evidence of amplification. The prominent focal amplification seen at the locus of EGFR is likewise absent in HPV-positive tumors.1 The importance of this distinction for anti-EGFR therapy remains obscure, but the lack of genomic targeting for amplification is evidence that HPV-positive tumors do not select for this gene at the clonal level. By contrast, HPV-positive more so than HPV-negative tumors display a clear prominence of amplification of 3q at the locus for the squamous lineage transcription factors SOX2, TP63, and the oncogene PIK3CA. PIK3CA activation promotes activation of cell cycle, metabolism, and transcription factors that regulate diverse genes that promote the malignant phenotype.1,2,41

When cell cycle signaling is considered (Fig 1), statistically significant copy number changes in at least three genes is remarkable. As expected, chromosome 9p, the locus for the gene CDKN2A which produces the protein product p16, is frequently lost in HPV-negative versus HPV-positive tumors. Similarly, HPV-negative tumors demonstrate prominent amplifications of CCND1 (cyclin D), whereas HPV-positive tumors contain a striking focal amplification at 20q11, the location of E2F1. The E2F1 gene, which encodes a key transcription factor that promotes genes that mediate cell cycle initiation from G0 to G1 and cell proliferation, is amplified in approximately 20% of HPV-positive HNSCCs but in only 2% of HPV-negative HNSCCs.1 E2F1 together with tumor-suppressor proteins TP53 and RB1, which are inactivated by the HPV E6 and E7 oncoproteins, critically deregulate cell cycle control and genomic stability in HPV-positive HNSCC. A fourth gene in the cell cycle pathway, RB1, although only rarely inactivated, is more often lost in HPV-positive tumors.

At this time, studies have detected only rare instances of activated fusion oncogenes based on analysis of DNA structural rearrangements. Most prominently, in a minority of HPV-positive samples, several authors have reported FGFR3-TACC3 fusions that seem promising as a therapeutic target.42–44 In addition, there was evidence in single samples for structural alterations associated with MET activation. Finally, the most well-described alternative transcript of EGFR, the so-called vIII mutant, was only rarely observed, at a rate of less than 1%.1

MUTATION SIGNATURE

It is perhaps somewhat surprising that tumors that presumably have disparate molecular origins as HPV-positive virally associated tumors and HPV-negative tobacco-associated tumors share as much homology in their genome landscape as the copy number data demonstrate. Other similarities between these subtypes include the generally similar mutation rate and number of copy number changes in each group. Other aspects of their molecular signature are, however, distinctly different.

As expected, the transversions associated with smoking in many tumors (ie, mutations that change a purine nucleotide to another purine (A↔G) or a pyrimidine nucleotide to another pyrimidine (C↔T) at CpG sites were more frequent in HPV-negative tumors.1 By contrast, a more unique signature has recently been reported in HPV-positive tumors and in some other tumors in which a predominance of TpC mutations is noted. These cytosine-to-thymidine C>T mutations have recently been shown most prominently in virally transformed cancers, in which there is increased cytosine deaminase mutagenesis that is characteristic of the apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic (APOBEC) family of enzymes.45 APOBEC cytosine deaminase activity is induced and has emerged as a potential mutagenic factor in virally induced human cancers. Indeed, sequence data from HPV-positive HNSCCs and other human tumors reveal genome-wide cytosine mutations consistent with APOBEC deamination and edits to the cellular DNA.46,47 The importance of this particular mutation signature is that it may explain, in part, a striking pattern seen in the distribution of mutations of one of the key oncogenes of HNSCC, PIK3CA, between HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors. Although PIK3CA is altered in tumors without regard to viral association, two specific C>T mutations in viral-associated tumors occur predominantly in two hotspots within the helical domain. These result in E542K and E545K amino acid substitutions that are implicated in PIK3CA kinase and oncogene activation.1,27,45 The specificity of PIK3CA targeting emphasizes even more strongly the importance of the 3q locus described in HPV-positive tumors described in the Structural Alterations section. In smoking-related tumors, PIK3CA mutations, including variants of unknown significance on signaling, are seen throughout the gene and are seen much less commonly in the hot spots. The signature APOBEC mutation of PIK3CA in HPV-positive HNSCC evokes the well-known transversion mutation of KRAS (G12C and G12V) in smoking-related lung adenocarcinoma.48 Strikingly, although squamous cell carcinoma of any site rarely demonstrates KRAS mutations, they are reported in HPV-positive HNSCC.27 Although the data are sparse, the interaction between smoking and KRAS mutation suggests a mechanism through which tobacco might augment risk in HPV-positive HNSCC.

HPV VIRAL INTEGRATION

In addition to the distinct mutational signature (APOBEC v smoking pattern), HPV-positive tumors are characterized by a second distinct structural alteration compared with HPV-negative tumors: the integration of viral DNA. Although the true rate of HPV integration into the human genome is unknown, existing data suggest that at least two thirds of patients with high expression of E6 and E7 by RNA quantification have detectable integration sites in the genome.49 The exact nature of the integration is the subject of ongoing investigation. Most tumors seem to have a single primary integration site, although the integration event itself may be complex at sites of gene amplification.50 Less common are tumors with multiple insertion sites on different chromosomes. Most viral integrations occur in or near genes, although the data do not yet support a recurrent site of integration to identify selective pressure on a specific location in the genome. As with most structural rearrangements in cancer, the predicted impact of integration is generally to silence the gene.1 Several tumor-suppressor genes have documented viral integration sites, such as RAD51 and ETS2. Whether the integration event resulted in tumor initiation or progression has not been definitively shown versus the alternative possibility that the gene disruption may be a passenger event. In the case of a passenger event, the targeting of a gene may be nonspecific and may result from a stochastic event that occurred at any open chromatin location. The lack of recurrent events gives more weight to the lower relevance of the integration site to tumor initiation and progression.

MUTATIONS AND PATHWAYS

Among the most anticipated results from recent tumor-profiling projects was the accounting of driver gene somatic mutations. A driver gene is defined as a gene that, when mutated, is responsible for either initiation or progression of a cancer. In the context of cancer sequencing projects in which mutations cannot be individually tested for their biologic function, driver mutation status is defined as a mutation that occurs more often than expected by chance. Many other incidental mutations, called passenger mutations, occur in the tumor, but these are attributed to the inherent instability of the cancer genome. Because the methods to rigorously define driver mutations continue to evolve, additional factors beyond statistical significance are considered when the most likely candidates for driver gene status are selected; factors include whether the gene is mutated at a specific functional position, the gene has been reported in other cancers, and mutations occur in conjunction with copy number or other structural alterations. Several reports with significant numbers of patients sequenced suggest that most common driver mutations from the overall population of HNSCC (mutations with a frequency > 5% to 10%) have been detected (Table 1).1,27–31 Data remain limited in subpopulations, including in HPV-positive tumors, for which the cohorts remain relatively underpowered for the most rigorous statistical approaches.

Table 1.

Genes Commonly Mutated in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

| Tumor Group | Mutated Genes |

|

|---|---|---|

| Gene Symbol | Mutation Rate (%)* | |

| All tumors | CDKN2A | 15-22 |

| FAT1 | 5-23 | |

| TP53 | 41-72 | |

| CASP8 | 5-9 | |

| AJUBA | ||

| PIK3CA | 8-21 | |

| NOTCH1 | 10-21 | |

| KMT2D (ie, MLL2) | 5-18 | |

| NSD1 | 4-10 | |

| HLA-A | ||

| TGFBR2 | ||

| HRAS | ||

| TPRX1 | ||

| FLG | ||

| DDX3X | ||

| RPIK4 | ||

| CUL3 | ||

| PTEN | ||

| SYNE1 | ||

| MED1 | ||

| FGFR3† | ||

| NFE2L2† | ||

| PIK3R1† | ||

| RB1† | ||

| FBXW7† | ||

| SCN9A† | ||

| CHEK2† | ||

| PTCH1† | ||

| KRAS† | ||

| MLL3† | ||

| FGFR2† | ||

| ZNF217† | ||

| RIMS2† | ||

| EGFR† | ||

| NOTCH2† | ||

| NOTCH3† | ||

| HPV-positive subgroup | TRAF3† | |

| PIK3CA | 22-56 | |

| B2M† | ||

| ZNF750† | ||

| IFNGR1† | ||

| MLL3† | ||

| DDX3X† | ||

| FGFR2/3† | 11-14 | |

| NOTCH1† | ||

| NF1† | ||

| KRAS† | ||

| FBXW7† | ||

Data are presented for selected genes with mutation rates > 10% in at least one series.

Indicates that the gene did not meet strict statistical criteria for significance of q score < 0.1 in at least one study. The gene is reported because the sum of evidence supports its status as a driver.

Many mutations, along with previously described regions of copy number and structural alteration, fall into a few cancer pathways. Most notably, almost every tumor had at least one mutation in the cell cycle and survival pathway; mutations included CDKN2A (p16) mutations, deletions, and hypermethylation; RB1 mutations and deletions; E2F1 amplification; CCND1 amplification; MYC amplification; and TP53. The gene CCND1 bears special mention, because it is among the most frequently altered oncogenes in HNSCC, although this occurs almost entirely in HPV-negative tumors. By the canonical pathway representation (Fig 1), it is immediately upstream of CDK4/CDK6, which is a target of palbociclib, an inhibitor that was recently approved in breast cancer.51 Trials in HNSCC are ongoing. Interestingly, nearly every HPV-negative tumor has inactivation of CDKN2A, and most have inactivation of TP53. One notable exception was a subset of oral cavity cancers that had p16 loss but wild-type TP53. Tumors in these patients have a strikingly high rate of CASP8 inactivation and concurrent HRAS activating mutations, which suggests a distinct clinical entity that, in at least one data set, was also associated with favorable clinical outcomes.1 Other investigators have reported similar favorable outcomes associated with wild-type TP53 in combination with other genomic alterations.52 The weight of the evidence, including the low rate of TP53 in patients with HPV-positive tumors who also benefit from favorable outcomes, suggests that wild-type TP53 status might serve as a universal marker of favorable outcome without regard to HPV status.

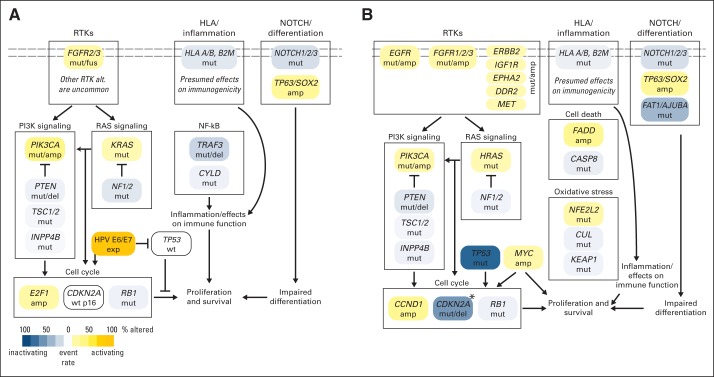

A second pathway clearly targeted by multiple driver mutations is the receptor tyrosine kinase pathway, which includes the RAS, PIK3CA, and PTEN branches. Numerous targets are altered, including activating mutations of PIK3CA, HRAS, FGFR3, KRAS, FGFR2, EGFR, and KRAS (Fig 3). The EGFR mutations are worthy of special note, because these are generally not the canonical activating mutations seen in lung cancer in the kinase domain of the gene. Mutations are more often in the juxtamembrane region of the gene and include a number that have been documented to be functional in other cancer types, including glioblastoma. Additional kinase pathway mutations include loss of function from repressor elements in the pathway; examples include PTEN, PIK3R1, and NF1.

Fig 3.

Frequent genetic aberrations in selected pathways altered in HPV-positive (A) and HPV-negative (B) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Overview of key genetic aberrations for HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck cancers. Shades of gold indicate frequency of activating changes in presumed oncogenes, and shades of blue indicate frequency of inactivating changes in presumed tumor suppressor genes. amp, amplification; del, deletion; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; mut, mutation; fus, fusion/translocation; wt, wild type.

Relevant to the recent enthusiasm in immune-based therapy in solid tumors, which includes the recent approval of nivolumab in squamous lung cancer, several known or suspected driver mutations in the immune and cell death pathways are demonstrated in HNSCC.53 Amplifications of FADD and BIRC2, along with loss-of-function mutations and deletions of CASP8 and TRAF3, highlight a dependence on the NF-κB pathway. Mutations in HLA-A/HLA-B and B2M are also seen in squamous lung cancer and, although these have not clearly been functionally validated, represent important candidate driver mutations. The immune system remains an important area of investigation through integrated data analysis as well. Investigators with TCGA demonstrated dramatic differences in immune signatures across the molecular subtypes of HNSCC identified by gene expression patterns, most notably with a complete absence of immune infiltration in the classic subtype and an activated T-cell signature in the mesenchymal subtype.1,54,55

Perhaps more difficult to target with current therapeutics, but nonetheless frequently altered, are three additional pathways: squamous differentiation, oxidative stress, and WNT signaling. Many tumors demonstrated loss-of-function mutations in NOTCH genes, almost always with amplifications of chromosome 3q, where the well-known squamous transcription factor TP63 is located. Perhaps less well appreciated is the increasingly recognized interaction between this differentiation pathway and two frequently lost genes of the WNT pathway, FAT1 and AJUBA.56,57 Several direct interactors with TP63 and NOTCH seem affected by loss of function, including ZNF75058 and, most important as the master regulator of oxidative stress, NFE2L2.59 It may be fair to say, if early reports are validated, that the NFE2L2 axis, with its repressors KEAP1 and CUL3, may represent one of the early potential therapeutic biomarkers for clinical use. Alterations of oxidative stress are seen across the spectrum of smoking-related cancers and are tightly associated with the classic gene expression subtype, as has been validated in numerous studies.1,60 Early translational data and preclinical models suggest that activation of this pathway may be associated with resistance to radiation, which is a cornerstone of therapy in HNSCC.61,62

Although there are many other mutations, one in particular bears special attention: the gene for nuclear receptor binding SET domain protein 1 (NSD1), which is altered in approximately 10% of tumors. The NSD1 gene is a histone 3 Lys 36 (H3K36) methyltransferase, similar to SETD2, a gene most associated with alterations in the clear cell subtype of renal cell carcinoma. Just as with SETD2 in clear cell carcinoma, mutations of NSD1 were associated with a dramatic, genome-wide hypomethylation phenotype in HNSCC.1,63 Interestingly, NSD1 seems relevant in relation to head and neck development in nonmalignant disease, as do germline inactivating mutations, which are associated with craniofacial abnormalities (Sotos syndrome).

INTEGRATED ANALYSIS

In addition to gene sequencing and copy number studies, there are mounting data from additional genomics platforms relevant to the understanding of HNSCC. The most mature of these data are gene expression studies that include microarrays and RNA sequencing from TCGA. It is now clear that reproducible subtypes of HNSCC can be defined by expression data, including the classic subtype associated with activated oxidative stress, the atypical subtype associated with lack of chromosome 7 amplification (including most HPV-positive cases), the mesenchymal subtype characterized by an activated T-cell signature, and the basal subtype associated with wild-type TP53. Molecular subtypes are an attractive way to classify tumors in some instances for the purposes of consideration of model systems and potentially of therapeutic groups, although the clinical utility of this remains unproved.1 Others have reported predictive gene expression signatures associated with prognosis, response to therapy, and HPV status; other phenotypes have been reported but have not generally been validated in clinical trials. The Chicago HNC Genomics cohort has recently reported a striking finding within HPV-positive HNSCC of two subgroups defined as prominent inflamed (inflamed mesenchymal HPV-positive subtype) or noninflamed (classic HPV-positive subtype) with potential implications for immunotherapy.1,10 Similar work has been reported with other biomolecule platforms that target epigenetics, miRNA, and proteomics.

OUTLOOK AND FUTURE CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

As a first step, accurate HPV diagnostics are needed beyond the interim proxy biomarker of p16. With confidence in the diagnosis of virally associated tumors will come a definitive answer about the effectiveness of cetuximab as a function of HPV status and confidence in making HPV-related treatment decisions in the future (eg, de-escalation). Furthermore, the increased breadth of genomic data on EGFR and related pathway alterations invites a re-evaluation of predictive biomarkers of EGFR-directed therapies. Extension of the molecular profiling beyond HPV status to target the most common molecular alterations for both therapeutic and prognostic indications will become possible if profiling is done routinely (eg, associated with clinical studies). Two immediately obvious candidates include the PIK3CA and CDK4/CDK6 pathways because of the high prevalence of PIK3CA mutations and CCND1 amplifications and the availability of existing therapeutics. Beyond targeted therapies, preclinical data already suggest that adherent signaling in the NFE2L2 pathway may predict differential phenotypes with respect to standard chemotherapy and radiation in ways that have clinical relevance, such as the selection of primary treatment modality. Other broad signatures, such as molecular subtypes predicted by expression profiling, might similarly influence the selection of therapies, such as immune-based treatment, and new technologies will allow reliable and reproducible determination of expression signatures as part of clinical trials. The discovery of molecular signatures and shared mutations across tumor types, such as squamous lung cancer and esophageal cancer, offers the potential to unify treatment paradigms across cancers that have historically been isolated by anatomic boundaries. Among the barriers that face clinicians and researchers in achievement of the promise of molecular characterization of HNSCC is uncertainty in the regulatory and reimbursement environment for molecular diagnostics. The pace of progress may be determined, in large part, by the ability of researchers and clinicians to order (and justify to payers or trial sponsors) the relevant clinical grade diagnostic tests to fuel molecularly targeted clinical trials and population studies.

In conclusion, head and neck cancer is a common and often fatal cancer that is typically treated with curative intent at the time of diagnosis. Many therapeutic questions, including the choice of optimal treatment modality and intensity and implications of HPV status on therapy, remain. By using the data provided by the first wave of comprehensive genome characterization, studies should focus and accelerate progress in this disease by highlighting the frequent gene alterations in the disease. Researchers will be able to leverage this knowledge in the design of clinical trials, the development of model systems, and the assessment of patient outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Katie Hoadley, Vonn Walter, Ashley Salazar, and Michele Hayward for assistance in figure and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grants No. U24 CA143848, U24 CA143848-02S1, and U10 CA181009-01, and by the Bobby F. Garrett Fund for Head and Neck Cancer Research (to D.N.H.). C.V.W. is supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Intramural Projects No. ZIA-DC-000016, ZIA-DC-000073, and ZIA-DC-000074.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: D. Neil Hayes, Tanguy Y. Seiwert

Data analysis and interpretation: D. Neil Hayes, Tanguy Y. Seiwert

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Genetic Landscape of Human Papillomavirus–Associated Head and Neck Cancer and Comparison to Tobacco-Related Tumors

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

D. Neil Hayes

Leadership: GeneCentric

Stock or Other Ownership: GeneCentric

Consulting or Advisory Role: GeneCentric

Research Funding: GeneCentric

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: GeneCentric

Carter Van Waes

No relationship to disclose

Tanguy Y. Seiwert

Honoraria: Novartis, Bayer AG, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Amgen

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst), Boehringer Ingelheim (Inst)

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gymnopoulos M, Elsliger MA, Vogt PK. Rare cancer-specific mutations in PIK3CA show gain of function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5569–5574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701005104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abogunrin S, Di Tanna GL, Keeping S, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers in European populations: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:968. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiron J, Sethi S, Ali-Fehmi R, et al. Racial disparities in human papillomavirus (HPV) associated head and neck cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López RV, Levi JE, Eluf-Neto J, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 and the prognosis of head and neck cancer in a geographical region with a low prevalence of HPV infection. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:461–471. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deschler DG, Richmon JD, Khariwala SS, et al. The “new” head and neck cancer patient-young, nonsmoker, nondrinker, and HPV positive: Evaluation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:375–380. doi: 10.1177/0194599814538605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–2111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang SH, Xu W, Waldron J, et al. Refining American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control TNM stage and prognostic groups for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:836–845. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keck MK, Zuo Z, Khattri A, et al. Integrative analysis of head and neck cancer identifies two biologically distinct HPV and three non-HPV subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:870–881. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan RC, Lingen MW, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Validation of methods for oropharyngeal cancer HPV status determination in US cooperative group trials. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:945–954. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318253a2d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiwert T. Accurate HPV testing: A requirement for precision medicine for head and neck cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2711–2713. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyer JH, Hauck F, Oliveira-Silva M, et al. Detection of HPV infection in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A practical proposal. Virchows Archiv. 2013;462:381–389. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlecht NF, Brandwein-Gensler M, Nuovo GJ, et al. A comparison of clinically utilized human papillomavirus detection methods in head and neck cancer. Modern Pathol. 2011;24:1295–1305. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4620–4624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang C, Marsit CJ, McClean MD, et al. Biomarkers of HPV in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5004–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chai RC, Lambie D, Verma M, et al. Current trends in the etiology and diagnosis of HPV-related head and neck cancers. Cancer Med. 2015;4:596–607. doi: 10.1002/cam4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran D, Giralt J, Harari PM, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients after treatment with high-dose radiotherapy alone or in combination with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2191–2197. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machiels J, Licitra LF, Haddad RI, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate (MTX) as second-line treatment for patients with recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) who progressed after platinum-based therapy: Primary efficacy results of LUX-Head & Neck. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermorken JB, Stöhlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I, et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): An open- label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:697–710. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fayette J, Wirth LJ, Oprean C, et al. Randomized phase II study of MEHD7945A (MEHD) vs cetuximab (Cet) in ≥ 2nd-line recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head & neck. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:iv340–iv356. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Association of human papillomavirus (HPV) and p16 status with efficacy and safety data in the phase III radiotherapy (RT)/cetuximab (cet) registration trial for locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (LASCCHN) Ann Oncol. 2014;25:iv340–iv356. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cmelak A. Reduced-dose IMRT in human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated resectable oropharyngeal squamous carcinomas (OPSCC) after clinical complete response (cCR) to induction chemotherapy (IC) J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:385s. (abstr LBA6006) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seiwert TY, Zuo Z, Keck MK, et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analysis of HPV-positive and HPV- negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clinical Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:632–641. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, et al. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung CH, Guthrie VB, Masica DL, et al. Genetic alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma determined by cancer gene-targeted sequencing. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1216–1223. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickering CR, Zhang J, Yoo SY, et al. Integrative genomic characterization of oral squamous cell carcinoma identifies frequent somatic drivers. Cancer Disc. 2013;3:770–781. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes DN, Kim WY. The next steps in next-gen sequencing of cancer genomes investigation. Clin Invest. 2015;125:462–468. doi: 10.1172/JCI68339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamlertthon W, Hayward MC, Hayes DN. Emerging technologies for improved stratification of cancer patients: A review of opportunities, challenges, and tools. Cancer J. 2011;17:451–464. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31823bd1f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyerson M, Gabriel S, Getz G. Advances in understanding cancer genomes through second-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:685–696. doi: 10.1038/nrg2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smeets SJ, Braakhuis BJ, Abbas S, et al. Genome-wide DNA copy number alterations in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas with or without oncogene-expressing human papillomavirus. Oncogene. 2006;25:2558–2564. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung GT, Lou WP, Chow C, et al. Constitutive activation of distinct NF-kappaB signals in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2013;231:311–322. doi: 10.1002/path.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eliopoulos AG, Dawson CW, Mosialos G, et al. CD40-induced growth inhibition in epithelial cells is mimicked by Epstein-Barr Virus–encoded LMP1: iInvolvement of TRAF3 as a common mediator. Oncogene. 1996;13:2243–2254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hacker H, Tseng PH, Karin M. Expanding TRAF function: TRAF3 as a tri-faced immune regulator. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:457–468. doi: 10.1038/nri2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karim R, Tummers B, Meyers C, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) upregulates the cellular deubiquitinase UCHL1 to suppress the keratinocyte's innate immune response. PLoS Path. 2013;9:e1003384. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oganesyan G, Saha SK, Guo B, et al. Critical role of TRAF3 in the Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent antiviral response. Nature. 2006;439:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature04374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capelletti M, Dodge ME, Ercan D, et al. Identification of recurrent FGFR3-TACC3 fusion oncogenes from lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6551–6558. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan L, Liu ZH, Lin ZR, et al. Recurrent FGFR3-TACC3 fusion gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1613–1621. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.961874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Stefano AL, Fucci A, Frattini V, et al. Detection, characterization and inhibition of FGFR-TACC fusions in IDH wild type glioma. Clin Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2199. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2199 [epub ahead of print on January 21, 2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson S, Chakravarthy A, Su X, et al. APOBEC-mediated cytosine deamination links PIK3CA helical domain mutations to human papillomavirus-driven tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1833–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burns MB, Temiz NA, Harris RS. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts SA, Lawrence MS, Klimczak LJ, et al. An APOBEC cytidine deaminase mutagenesis pattern is widespread in human cancers. Nat Genet. 2013;45:970–976. doi: 10.1038/ng.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dogan S, Shen R, Ang DC, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: Higher susceptibility of women to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6169–6177. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parfenov M, Pedamallu CS, Gehlenborg N, et al. Characterization of HPV and host genome interactions in primary head and neck cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15544–15549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akagi K, Li J, Broutian TR, et al. Genome-wide analysis of HPV integration in human cancers reveals recurrent, focal genomic instability. Genome Res. 2014;24:185–199. doi: 10.1101/gr.164806.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2- negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): A randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:25–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gross AM, Orosco RK, Shen JP, et al. Multi-tiered genomic analysis of head and neck cancer ties TP53 mutation to 3p loss. Nat Genet. 2014;46:939–943. doi: 10.1038/ng.3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rizvi NA, Mazières J, Planchard D, et al. Activity and safety of nivolumab, an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, for patients with advanced, refractory squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 063): A phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walter V, Yin X, Wilkerson MD, et al. Molecular subtypes in head and neck cancer exhibit distinct patterns of chromosomal gain and loss of canonical cancer genes. PloS One. 2013;8:e56823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chung CH, Parker JS, Karaca G, et al. Molecular classification of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas using patterns of gene expression. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:489–500. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris LG, Kaufman AM, Gong Y, et al. Recurrent somatic mutation of FAT1 in multiple human cancers leads to aberrant Wnt activation. Nat Genet. 2013;45:253–261. doi: 10.1038/ng.2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nola S, Daigaku R, Smolarczyk K, et al. Ajuba is required for Rac activation and maintenance of E-cadherin adhesion. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:855–871. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201107162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sen GL, Boxer LD, Webster DE, et al. ZNF750 is a p63 target gene that induces KLF4 to drive terminal epidermal differentiation. Dev cell. 2012;22:669–677. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wakabayashi N, Shin S, Slocum SL, et al. Regulation of notch1 signaling by nrf2: Implications for tissue regeneration. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra52. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kawasaki Y, Okumura H, Uchikado Y, et al. Nrf2 is useful for predicting the effect of chemoradiation therapy on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Annals Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2347–2352. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3600-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shibata T, Kokubu A, Gotoh M, et al. Genetic alteration of Keap1 confers constitutive Nrf2 activation and resistance to chemotherapy in gallbladder cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1358–1368. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature. 2013;499:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature12222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]