Abstract

The study investigates the associations of work-family conflict and other work and family conditions with objectively-measured outcomes cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration in a study of employees in nursing homes. Multilevel analyses are used to assess cross-sectional associations between employee and job characteristics and health in analyses of 1,524 employees in 30 extended care facilities in a single company. We examine work and family conditions in relation to two major study health outcomes: 1) a validated, Framingham cardiometabolic risk score based on measured blood pressure, cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and self-reported tobacco consumption, and 2) wrist actigraphy-based measures of sleep duration. In fully-adjusted multi-level models, Work-To-Family conflict, but not Family-to-Work conflict was positively associated with cardiometabolic risk. Having a lower-level occupation (nursing assistants vs. nurses) was also associated with increased cardiometabolic risk, while being married and having younger children at home was protective. A significant age by Work-To-Family conflict interaction revealed that higher Work-To-Family conflict was more strongly associated with increased cardiometabolic risk in younger employees. With regard to sleep duration, high Family-To-Work Conflict was significantly associated with shorter sleep duration. In addition, working long hours and having younger children at home were both independently associated with shorter sleep duration. High Work-To-Family Conflict was associated with longer sleep duration. These results indicate that different dimensions of work-family conflict (i.e., Work-To-Family Conflict and Family-To-Work Conflict) may both pose threats to cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration for employees. This study contributes to the research on work- family conflict suggesting that Work-To-Family and Family-To-Work conflict are associated with specific outcomes. Translating theory and our findings to preventive interventions entails recognition of the dimensionality of work and family dynamics and the need to target specific work and family conditions.

Keywords: work-family conflict, Work-To-Family Conflict, Family-To-Work Conflict, supervisor support, long work hours, cardiometabolic risk, sleep duration

INTRODUCTION

Over the last several decades, as women have increasingly joined the full-time labor force in most industrialized countries, it has become clear that combining the responsibilities of caring for families while also maintaining full-time employment may often be challenging (King et al., 2013). This challenge may be greater for women in lower- and middle-wage jobs where benefits are fewer and economic resources flowing to families are constrained (Damaske, 2011; Montez, Hummer, Hayward, Woo, & Rogers, 2011; Montez & Zajacova, 2013b). Men may also increasingly experience these challenges as dual-earner families and single parenthood become more common for both women and men. These challenges are further enhanced in the United States by the absence of many public social protections that enable working men and women to reduce conflicts between work and family responsibilities (Gornick & Meyers, 2003; Gornick, Meyers, & Ross, 1997; Heymann, 2000; Kelly, 2003; Kelly & Moen, 2007; King, et al., 2013). Evidence from Scandanavia suggests that extensive social policies supporting working parents have benefits for both parents and children (Burstrom et al., 2010; Fritzell et al., 2012; Whitehead, Burstrom, & Diderichsen, 2000) but may not reduce sickness absence or burnout, especially for women. Rates of sickness absence remain high in Sweden and women dominate among the long-term sick listed (Johansson, 2002; Vingard et al., 2005). This suggests that social policies related to family leave may not be sufficient to improve well-being. The division of household responsibilities and less formal workplace practices, norms and values may play additional critical roles (Bratberg, S., & E., 2002; Lidwall, Marklund, & Voss, 2010). Women still bear the majority of home responsibilities though changes have occurred over the last years. Strained financial situations, low occupational grade, demanding jobs and single motherhood may lead to particular vulnerabilities and strains leading to sickness absence (Casini, Godin, Clays, & Kittel, 2013; Josephson, Heijbel, Voss, Alfredsson, & Vingard, 2008; Vingard, et al., 2005; Voss et al., 2008). Thus, norms and values related to home responsibilities and informal practices and strains at work create risks as well as opportunities, especially for women. This multitude of polices, practices and norms may well lead to patterns of strain, increases in work-family conflict and resultant health and sickness absence risks.

Over the last 30-40 years, women’s adult life expectancy in the United States has virtually stagnated while life expectancy in almost all other industrialized nations has improved, as a recent National Academy of Science Panel has shown (National Research Council (US) Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries, 2011). The US now ranks at the bottom of OECD countries in life expectancy for women whereas 40 years ago, the United States life expectancy for women ranked in the middle of industrialized OECD nations. Furthermore, less educated women have actually experienced absolute increases in mortality rates over this period (Montez & Zajacova, 2013b; Olshansky et al., 2012) with these striking losses apparent in a number of states and counties across the US (Kindig & Cheng, 2013). We theorize that these poor international rankings and absolute decreases in life expectancy in less educated and socioeconomically disadvantaged women are in part due to the labor participation of women who also have responsibility for caregiving of young (and old) family members in the absence of many formal or informal work/family practices or policies. Employers have become increasingly concerned with this work/family challenge, especially those companies with female-dominated labor forces. In fact, many corporations have developed work/life policies in the absence of public sector programs (Gornick & Meyers, 2003; Gornick, et al., 1997; Kelly, 2003, 2006; E.E. Kossek, 2005; E.E. Kossek, Barber, & Winters, 1999; E.E. Kossek & Hammer, 2008).

The health care sector is a rapidly growing major industry experiencing many of the challenges associated with work/family issues. Although nursing and related occupations have become somewhat more gender integrated, the majority of those working in extended care jobs are women, many of whom are in the age range when family formation is common (Artazcoz, Borrell, & Benach, 2001; Avendano, Glymour, Banks, & Mackenbach, 2009; Cherlin, 2010). The challenge to health care organizations is to maintain a workforce capable of delivering high quality care to patients while at the same time remaining economically viable in a competitive market constrained by regulations and cost reimbursement policies. Health care industries are also challenged by the need to maintain adequate work forces 24/7 with complex organizational requirements leading to multiple shifts and long work hours. Almost all health care jobs require face time; little of the work can be done at home or off site. Many of these working conditions, including long work hours and variable shift schedules, are known to be related to work-family conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985) and have health risks for employees (Floderus, Hagman, Aronsson, Marklund, & Wikman, 2009; Joyce, Pabayo, Critchley, & Bambra, 2010; Karlsson, Knutsson, Lindahl, & Alfredsson, 2003). Work patterns that give the worker more choice or control are likely to have positive effects on work-family conflict (Hammer, Allen, & Grigsby, 1997) and health and wellbeing (Moen, Kelly, & Lam, 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, & Huang, 2011).

The aim of this paper is to describe associations between work-family conflict and worker health in nursing home employees. We are particularly interested in two dimensions of work-family conflict: that is, Work-To-Family Conflict and Family-To-Work Conflict (i.e., the degree to which work interferes with family and the degree to which family interferes with work). Additional conditions of interest include work and family factors such as long work hours and children in the household, schedule control, and supervisor support that may also contribute to work-family effects on health. This study falls into a larger class of studies that have, for the past three to four decades, examined the role of workplace conditions and the work/life interface among men and women in relation to biological indicators of physiologic stress responses, cardiometablolic function, injuries and mental health. Much of this foundational work was conducted in Scandinavia. In the 1970’s Frankenhaeuser (Frankenhaeuser, 1989; Frankenhaeuser & Gardell, 1976; Frankenhaeuser & Johansson, 1986; Frankenhaeuser et al., 1989), Lundberg (Lundberg, Mardberg, & Frankenhaeuser, 1994), Gardell (Gardell, 1982), Johansson (Johansson, 1989) and others building on stress theories developed by Cannon (Cannon, 1932) decades earlier, developed a biopsychosocial approach to work-life issues (Frankenhaeuser, 1989). During virtually the same time, Karesek (Karasek, 1979; Karasek, Baker, Marxer, Ahlbom, & Theorell, 1981), Theorell (Karasek & Theorell, 1990) and others developed a model of the ways in which job strain might impact the health of workers.

The primary aim of the biopsychosocial approach to working life was “to provide a broad scientific base for redesigning jobs and modifying work organization in harmony with human needs, abilities and constraints”(Frankenhaeuser, 1989). This work led to the Swedish Work Environment Act effective since 1977 related to adapting working conditions and job redesign. The Work, Family and Health Network study rests on this body of work recognizing that job redesign and how work is organized is central to the health and well-being of workers. The United States lags far behind many European countries in both labor policies, practices and, in fact, in epidemiologic research in this area. Furthermore, other epidemiologists and behavioral and social scientists prominently Orth-Gomer (Orth-Gomer, 2007) Lundberg (Berntsson, Lundberg, & Krantz, 2006; Lundberg, et al., 1994), Karasek and Theorell (Karasek & Theorell, 1990) developed studies in which they investigated the role of job strain or work, family or marital stress in physiologic responses ranging from HPA axis responses, perceptions of symptoms to acceleration of coronary disease progression. Orth-Gomer and colleagues in particular, have made notable advances to the understanding of cardiovascular risks in women (Orth-Gomer, 2012; Orth-Gomer et al., 2009; Orth-Gomer et al., 2000). Her work indicates that women may have different psychosocial risks than men. Specifically, marital stress may be more central to cardiovascular disease for women than job strain (Orth-Gomer, et al., 2000).

The Work, Family and Health Network Study of nursing home employees adds to the rich history in this area by incorporating biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration in this study of US nursing home employees, most of whom are low and middle-wage working women. These analyses link work and family exposures to directly measured cardiometabolic and sleep risks from the occupational sample of nursing home employees in the Work, Family and Health Study (Bray et al., 2013; King, et al., 2013). Our aim is to link work-family conflict to major health outcomes of the study and to provide baseline descriptions of the sample. Earlier findings from a smaller pilot of other nursing homes from different companies(n=4 sites) (Berkman, Buxton, Ertel, & Okechukwu, 2010) informed many of the approaches and measures. Here we extend our analyses to a wide range of work-family conditions and related job characteristics in this larger, more comprehensive study of direct care workers in nursing homes.

Specifically, we conduct multilevel regression analysis of the associations between work-family conflict and health. We do this in a multilevel context at the level of the individual employee and at the worksite (nursing home) level and using two major health outcomes of the WFH study. Measured cardiometabolic risk is based on a modified Framingham risk factor score (Marino et al., 2014) including blood pressure, cholesterol, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and tobacco consumption. Objectively-measured sleep duration is assessed from wrist actigraphy monitoring and recently validated (Marino et al., 2013), and is related to workplace conditions in extended care workers (Berkman, et al., 2010). Sleep has been related to wellness outcomes in multiple workplace studies in direct care workers (Buxton et al., 2012; Sorensen et al., 2011), the personal safety of medical interns and their patients (Barger et al., 2005; Landrigan, Lockley, & Czeisler, 2005; Landrigan et al., 2010; Landrigan et al., 2004), and has been termed a ‘health imperative’ (Luyster, Strollo, Zee, & Walsh, 2012).

We focus attention on the associations between these two outcomes and work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict, but also include a range of other work-family conditions that may be related to health as well, specifically long work hours, schedule control, Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB), and having young children living at home. We include demographic, socioeconomic and job strain (job demands and decision authority) characteristics in our analyses to be sure there is not confounding by these factors associated with our two health outcomes.

This work builds on a number of related theories proposing that psychosocial strains, in this case primarily related to the work/family interface, influence health. The specific theories related to work-family conflict fall in a class of larger frameworks related to biopsychosocial and ecosocial frameworks developed by Frankenhaeuser (Frankenhaeuser, 1989; Frankenhaeuser & Johansson, 1986) and Krieger (Krieger, 2011) respectively. These frameworks outline models in which social and economic conditions may induce stressful person-environment interactions and cause such strains to become biologically embedded through stressful physiologic responses or risk related behaviors. Ecosocial theory shares a great deal with biopsychosocial frameworks (Krieger, 2011) in which social strains produce physical stress that then influences markers of disease processes commonly related to cardiovascualar and metabolic disorders. Here we integrate these theories as others have done (King, et al., 2013) to help us frame an understanding of why work-family conflicts, in both directions, have important consequences for the health and wellbeing of employees, especially those with fewer social or economic resources.

Specific theories of work-family conflict extend and specify further the above macro theories. Theories developed by Bianchi and Moen (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010; Moen, 2003; Moen, Kelly, & Hill, 2011) suggest that work-family conflict also builds on role theories in which conflicting demands shape strains. At the interface between job and family, both jobs and families can have variable demands, resources and sources of control to moderate those demands. In a measure of work-family conflict developed by Netemeyer (Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996), conflict can occur from work to family, or family to work. For women, especially, who even today fulfill the largest obligations with regard to unpaid home care, added roles in the labor force may lead to exhaustion and illness (Arber, Gilbert, & Dale, 1985). Both work and family roles represent core components of adult identity for many men and women and thus strains in fulfilling one of these roles influenced by commitments to the other role are hypothesized to cause a host of stress-related outcomes and are in part mediated by risk related health behaviors (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1997; Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Hammer & Sauter, 2013). In direct contrast to these theories in which multiple roles produce strains are theories of role enhancement. Such theories posit that multiple roles are fulfiling and may be health promoting for a number of reasons. Martikainen (1995) and Barnett have proposed ways in which multiple work and family roles may enhance well being (Barnett & Baruch, 1985). We will return to this these opposing theories in the discussion as we evaluate our findings in light of our primary hypotheses which rest on the models in which work family conflict will lead to poor health outcomes.

A related theory of job strain developed by Karasek, Theorell and others (Karasek & Theorell, 1990; Karasek, 1979; Siegrist, 1996) suggest that job strain influences health through a number of mechanisms from increasing physiological stress responses to influencing risky behaviors. Further additions to the model suggest that low supervisor and/or coworker support is a third dimension of job strain influencing health and well-being. Job strain theories indicate that such workplace exposures may directly alter cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, (Choi, Schnall, Ko, Dobson, & Baker, 2013; Kivimaki et al., 2012; Landsbergis & Schnall, 2013) as well as influencing behaviors such as tobacco consumption, diet, and physical activity, which in turn affect CVD risk. As such, they are relevant to work and family conflict. We include demand and decision authority in our analyses to make sure we are not conflating work-family strain with straightforward job strain. Furthermore, we have developed a work-family job strain model in which social support may reduce cardiometabolic and other health risks (Berkman & O’Donnell, 2013). Supervisor support related to work–family issues [i.e., FSSB] adds a new dimension to general measures of supervisor support (Frye & Breaugh, 2004; Hammer, Kossek, Bodner, & Crain, 2013; Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Building on these theories and frameworks, we hypothesize that

Employee reports of work-family conflict including both Work-To-Family Conflict as well as Family-To-Work Conflict will be positively associated with cardiometabolic risk and negatively associated with actigraphically measured sleep duration. We hypothesize that these associations will be independent of a wide range of other sociodemographic and work-related conditions.

Based on our earlier findings, supervisor behaviors, in this study measured by Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB) will be associated with our two outcomes: cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration. Higher levels of FSSB will be associated with lower cardiometabolic risk and longer sleep duration.

Working conditions that strain home life – including long work hours, low schedule control, high job demands and low decision authority – will influence employee health. Furthermore, working parents with children at home will exhibit increased cardiometabolic risk and shorter sleep duration.

METHODS

Study Design

This study is part of a large research network effort to understand the ways in which modification of workplace practices and policies improves the health of employees, their families, and the industries in which they work (Bray, et al., 2013; King, et al., 2013). In this paper we report baseline results from employees in an extended care (nursing home) industry. (Hammer, Kossek, Anger, Bodner, & Zimmerman, 2011; Kelly & Moen, 2007; Kelly, Moen, Oakes, & Fan, Accepted; E. E. Kossek, Hammer, Kelly, & Moen, 2014). Our primary goal here is to present the work and family conditions in relation to two primary outcomes, cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration in a sample of employees in one firm.

Research Site

Our corporate partner, a company we refer to by the alias “Leef”, was identified after sending letters to several potential companies with appropriate characteristics including a large number of facilities with geographic proximity, and stability and willingness to participate and to donate work time for respondents’ participation. After several meetings with the regional CEO, heads of units related to human resources and clinical care, and regional directors, Leef leadership confirmed its interest to participate.

Of the 56 facilities at Leef at study launch, 30 were selected from the New England region of Leef. Facilities were excluded if they were in a very isolated setting, if there were fewer than 30 direct patient-care employees, or if facilities were recently acquired. One facility was excluded due to ongoing participation in another study. None of the 30 facilities declined.

Study Participants

All employees who were direct care workers with at least 22 hours work /week and not exclusively night-workers were invited to participate (Bray, et al., 2013). Excluded from our study were employees in custodial, kitchen and food preparation, clerical and other employees who had no direct patient care duties with residents. We selected direct care workers for participation in this study because they had a common set of policies, regulations and work activities, and share many working conditions with other health care sectors. Furthermore, they constitute a low and middle-wage work force often neglected in work-family studies. Employees who worked only night shifts were excluded from this study; however, employees who worked some day and night shifts were included.

Measures

Trained field interviewers administered survey instruments and health assessments as described elsewhere (Bray, et al., 2013). Computer-assisted personal interviews spanned demographics, socioeconomic status, family demographics, respondent’s work environment, physical health, mental health, and family relationships and took about 50 minutes to administer and health assessments an additional 20 minutes. All participants provided informed written consent. Employees received up to $60 for completing all components. Physical health outcomes were measured, including primary biomarker outcomes of cardiometabolic disease risk and sleep. Sleep duration is based on wrist actigraphy. Cardiovascular/metabolic risks included blood pressure, HbA1c, cholesterol (Total and HDL), BMI, smoking status (see Bray et al 2013 for full description). We describe variables from three domains: 1. sociodemographic conditions, 2. work-family conflict and other work conditions and 3. health.

Sociodemographic conditions of employees

Employee age was analyzed in one-year intervals and gender was coded as male or female. Employees were asked two separate questions about their race and ethnicity. These responses were used to construct a race/ethnicity variable: Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Latino and other. Additionally, employees indicated whether they were born in the United States for foreign-born status (yes/no). Marital/partner status was categorized as currently married or living with a partner (yes/no).

Occupation was assessed by asking official job titles, and coded as registered nurse or licensed practical nurse (RN/LPN), certified nurse assistant (CNA) and other. Household income (annual) was assessed in $5,000 increments up to $60K. The number of people in household was measured by report of household census. These responses were categorized in relation to U.S. Poverty Thresholds for 2011 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). For these analyses, we use a dichotomized version, greater than 300% of poverty threshold or less.

The number of children less than or equal to 18 in household was assessed through a household census and dichotomized (none, one or more).

Measures of work-family conflict and other work and family conditions

Work/family conflict is a form of inter-role conflict in which role pressures from work and family domains are not compatible (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). This construct is bidirectional in nature (family-to-work and work-to-family) and was operationalized here using Netemeyer’s validated Work-Family Conflict, or WTFC (Netemeyer, et al., 1996). Employees were asked five questions regarding conflict in each direction. Responses were coded 1-5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and averaged to create a continuous measure in which higher scores reflect greater conflict (alpha for WTFC=0.9 and alpha for FTWC =0.8).

Family-supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) assessed employee appraisals of supervisor’s behavior related to integrating work and family (Hammer, et al., 2011; Hammer, Kossek, Yrgaui, Bodner, & Hanson, 2009). Employees were asked about family-related supervisory support in four domains: emotional support, instrumental support, role modeling and creative management. We used a short form of FSSB derived from four items (Hammer, et al., 2013), categorized 1-5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree) and averaged to generate an overall score, with higher scores reflecting greater FSSB (alpha=0.9).

Schedule control was used to measure employees’ control over the hours that they work. We utilized a shortened, 8-item version of Thomas and Gansters’ scale (Thomas & Ganster, 1995). Items included how much choice employees have over: when they take vacation or days off, when they take off a few hours, when they begin and end work days, total number of hours worked/week. Responses were coded 1-5 (very little to very much) and averaged with higher scores reflecting greater schedule control (alpha=0.7).

Long work hours were assessed from an item saying “About how many hours do you work in a typical week in this job?” and “On average, how many hours per week do you work at this other job(s)?” and summed if the respondent indicated he/she has an additional job to obtain total hours worked/week across all jobs.

Psychological Job Demands and Decision Authority were based on the work of Karasek and colleagues (Karasek & Theorell, 1990; Theorell et al., 1998). Employees were asked about having enough time to get work done and working very fast and hard (psychological job demands) as well as freedom to decide how to do work and having a say about what happens on the job (decision authority). Response categories were strongly disagreed, disagreed, neither, agreed or strongly agreed (1-5, respectively). These ordinal responses were averaged separately and analyzed continuously (alpha=0.6 and alpha=0.6 for psychological job demands and decision authority respectively).

Site-level measures of work place organization, work-to-family conflict, FSSB and other measures were created by aggregating individual-level responses, centered at the mean and entered as continuous variables.

Health measures of employees

A cardiometabolic risk score (CRS) was created based on modifiable risk factors in the widely-used Framingham risk score (e.g., age- and sex-specific strata use different score calculations). The score has been independently validated using the Framingham (offspring) data to predict subsequent cardiovascular event risk (Marino et al., 2014). Biomarkers measured as previously described (Bray, et al., 2013) included height and weight to calculate body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, and HbA1c. Seated blood pressure readings were collected three times at least 5 minutes apart during the interview, and before blood sampling, using wrist blood pressure monitors (HEM-637, Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL). Body mass index (height/weight2) was calculated based on height (Seca213/214 stadiometers, Seca North America, Hanover, MD) and weight (Health-O-Meter 800KL, Jarden Corporation, Rye, NY) assessment. Up to five blood spots were collected on bar-coded filter paper (903 Protein Saver Paper, GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) as previously described (Ostler, Porter, & Buxton, 2014), air-dried, and sealed in a plastic bag for room-temperature shipment with desiccant for storage at −86°C until assay for cholesterol as specifically validated for this study from serum to DBS equivalents (Samuelsson et al., Under Review). Interviewers also collected a 1 microliter blood droplet for immediate measurement of HbA1c levels (DCA Vantage Analyzer, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Frimley, Camberley, UK). Tobacco consumption was self-reported. In the cardiometabolic risk score employees are categorized as smokers or non-smokers.

Sleep was assessed by one week of wrist actigraphy (Spectrum, Philips/Respironics, Murrysville, PA) that captures single-axis wrist movements and light levels in 30-sec epochs, and, via induction, an “on-wrist” indicator of compliance. Measures of sleep quantity were scored using a standard algorithm recently validated (Marino et al., 2013) and included average daily (24-hr) sleep duration (in hours).

Data from each subjects’ sleep watch was analyzed using manufacturers software (Actiware v 5.61, Philips/Respironics) by at least two members of the scoring team as previously described (Olson et al., 2013) using the manufacturer’s ‘medium density algorithm as recently validated against polysomnography (Marino et al., 2013). A recording was deemed invalid if there is constant false activity (a device malfunction), or for irretrievable data. Reasons for invalid days within a recording include watch error, such as false activity, and subject non-compliance. Diaries were not used due to subject burden, recall bias, and low response rates in previous studies, e.g., (Lauderdale et al., 2006). Concordance was assured between at least two scorers for whether the recording is valid or not, number of valid days, and all scorers have used the same cut time to define 24-hr days. Sleep periods differing by 15 minutes in length, Total Sleep Time (TST) or Wake After Sleep Onset (WASO) were rescored with all final adjudications by a coauthor.

Analyses

Gender-stratified, unadjusted means are described initially. We then used multilevel models to examine factors influencing cardiometabolic risk score (CRS) and sleep. The multilevel models account for the hierarchical structure of the data with level 1 units (i.e., employees) nested within level 2 units (i.e. nursing homes), and included a site specific intercept allowing random variation due to unobserved, or unmeasured site-level characteristics.

RESULTS

Results are presented in three major areas: 1) the characteristics of the sample, 2) multilevel analyses related to cardiometabolic risk and 3) multilevel analyses related to sleep duration.

Sample characteristics and distribution of work related conditions

Overall, of 1,783 total eligible employees, we enrolled 1,524 employees [1,406 women, 118 men, a response rate of 85% (Bray, et al., 2013)]. These employees were classified as direct care workers, including such occupations as nurses, certified nursing assistants, and a small number of administrators.

Demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The vast majority of men and women in our sample are CNA’s. Both genders report a high level of job demands (mean=3.7 for men vs. 3.8 for women on a scale of 1-5) and family supportive supervisory behavior (mean=3.8 for men vs. 3.7 for women on a scale of 1-5).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and health characteristics by gender, Leef baseline cohort of extended care workers.a

| Males (n=118) |

Females (n=1406) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age (mean, standard deviation) | 36.4 | (9.5) | 38.7 | (12.7) |

| Married/ Partnered (%) | 53 | 64 | ||

| Caregiver (%) | 26 | 30 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 44 | 67 | ||

| Black | 32 | 12 | ||

| Hispanic | 12 | 14 | ||

| Other | 12 | 8 | ||

| Foreign-born (%) | 43 | 25 | ||

| Occupation - RN/LPN (%) | 24 | 28 | ||

| Post-secondary education (%) | 73 | 61 | ||

| Poverty level: < 300% of 2011 poverty threshold (%) | 55 | 62 | ||

| Kids <=18 in HH (%) | 31 | 48 | ||

| Total hrs work / wk (all jobs up to two jobs ) | 43.6 | (11.7) | 39.6 | (10.5) |

| Work characteristics (mean, standard deviation) | ||||

| Decision authority | 3.5 | (0.7) | 3.4 | (0.8) |

| FSSB | 3.8 | (0.8) | 3.7 | (0.9) |

| Job demands | 3.7 | (0.8) | 3.8 | (0.7) |

| Schedule control | 2.7 | (0.8) | 2.6 | (0.7) |

| Work-to-family-conflict | 2.6 | (0.9) | 2.8 | (0.9) |

| Health conditions (mean, standard deviation) | ||||

| Sleep duration (hrs/day) | 7.0 | (1.0) | 7.6 | (1.0) |

| Cardiometabolic score (% 10-yr risk) | 13.0 | (11.1) | 7.3 | (7.7) |

| Blood pressure (mmHg): Systolic | 122.6 | (11.7) | 114.1 | (13.0) |

| Blood pressure (mmHg): Diastolic | 79.3 | (9.6) | 71.8 | (9.1) |

| BMI | 28.8 | (5.8) | 29.5 | (7.1) |

| HbA1c | 5.5 | (0.7) | 5.5 | (0.6) |

| Smoker (%) | 25 | 31 | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 161.2 | (26.0) | 150.6 | (25.8) |

Age:N=1404 for females; Race: N=1405 for females; Occupation: 1404 for females; Education: 1405 for females; Poverty: N=115 for males and 1367 for females; Total hours worked: N=117 for males and 1403 for females; Job demands: N=118 for males and 1405 for females; Decision authority: N=118 for males and 1393 for females; WTFC: 118 for males and 1402 for females; FSSB: 118 for males and 1392 for females; Smoking: N=118 for males and 1404 for females; Blood pressure: N=117 for males and 1394 for females: BMI: N=115 for males and 1386 for females; Total cholesterol: N=111 for males and 1353 for females; HgA1C: N=110 for males and 1343 for females: Cardiometabolic score: N=106 for males and 1306 for females; Sleep: N=85 for males and 1134 for females

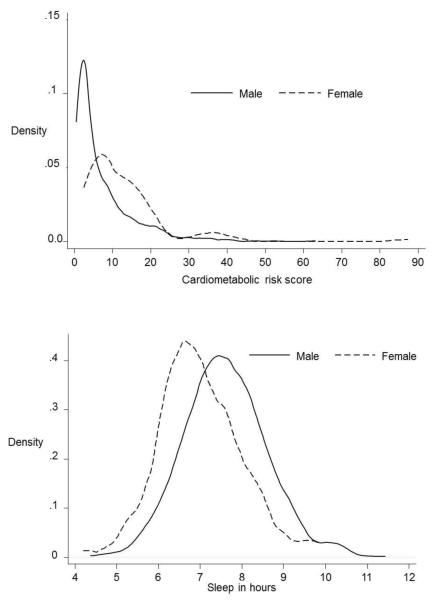

We identified two primary health outcomes of our study: cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration. The distributions of cardiovascular risk and sleep duration for men and women are depicted in Figure 1. Men and women averaged 7.0 and 7.6 hours of sleep per night, respectively.

Figure 1. Distributions of outcomes (cardiometabolic risk, left; actigraphically-measured sleep duration, right) by gender in the Leef cohort of extended care healthworkers.

Solid lines: males, dashed lines, females.

Multi-level analyses of work-family conflict and work-family factors on cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration

We use multilevel models at the individual and facility level to assess the potential health risks associated with work-family conflict (both directions), family composition and specific job characteristics of schedule and job control, supervisor support and long work hours. Our aim here is to assess both compositional and contextual factors that are associated, in the cross-section, with cardiometabolic risk and actigraphically-assessed sleep duration.

Cardiometabolic risk

Table 2 shows the estimates along with significance levels for cardiometabolic risk in a model including both individual- and site-level characteristics in a multilevel regression model.

Table 2.

Associations between individual and site-level characteristics with mean cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration, Leef Baseline Cohort of extended care workers.

| Predicted 10-yr Cardiometabolic risk score (%) |

Confidence Interval |

Sleep in minutes |

Confidence Interval |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (centered at mean) | 0.52 | (0.50, 0.54) | − 0.32 | (−0.62, −0.03) |

| Female vs. Male | − 6.97 | (-7.97, −5.97) | 30.52 | (17.293, 43.743) |

| Married vs Unmarried | − 0.77 | (-1.33, −0.20) | 1.24 | (−6.03, 8.52) |

| Race/ethnicity, Black vs White | −0.09 | (−1.14, 0.95) | − 20.15 | (−34.39, −5.91) |

| Race/ethnicity, Hispanic vs White | −0.06 | (−1.02, 0.91) | −12.32 | (−24.84, 0.20) |

| Race/ethnicity, other vs White | −0.12 | (−1.11, 0.87) | − 17.31 | (−30.11, −4.51) |

| Foreign-born vs US-born | − 1.75 | (−2.55, −0.95) | −9.16 | (−19.69, 1.38) |

| Occupation, RN vs CNA/Other | − 0.99 | (−1.64, −0.33) | −7.06 | (−15.57, 1.45) |

| Poverty, ≥ 300% vs <300% / missing | 0.38 | (−0.26, 1.02) | 0.38 | (−7.95, 8.72) |

| Children, ≤ 18 y vs > 18 y | − 1.31 | (−1.88, −0.73) | − 10.08 | (−17.44, −2.71) |

| Total hours employment (all jobs) | − 0.03 | (−0.05, 0.00) | − 0.48 | (−0.81, −0.15) |

| Job psychological demands | − 0.41 | (−0.79, −0.03) | −2.52 | (−7.35, 2.31) |

| Decision authority | −0.09 | (−0.48, 0.31) | 2.52 | (−2.63, 7.67) |

| Work to Family Conflict | 0.39 | (0.04, 0.74) | 5.67 | (1.07, 10.27) |

| Family to Work Conflict | −0.06 | (−0.58, 0.45) | − 8.06 | (−14.83, −1.29) |

| Schedule control | 0.00 | (−0.40, 0.39) | 0.6 | (−4.49, 5.68) |

| Family Supportive Supervisory Behavior | 0.04 | (−0.29, 0.36) | −1.1 | (−5.23, 3.03) |

| Constant | 15.89 | (14.71, 17.02) | 439.35 | (423.92, 454.78) |

| Observations | 1,338 | 1,154 | ||

| Number of groups | 30 | 29 | ||

| df | 23 | 23 | ||

| Log likelihood | −3988 | −6241 | ||

| Variance component btw nursing homes | 0.38 | (SE= 0.27) | 83.76 | (SE= 51.51) |

| Variance component btw individuals | 22.61 | (SE= 0.89) | 3219.12 | (SE= 136.73) |

| VPC a | 0.02 | 0.03 |

VPC= (level-2 variance/ (level-1 variance + level-2 variance)) = proportion of variance in outcome attributed to differences between sites. All models also adjusted for work-site level psychological job demands, decision authority, work-to-family conflict, family-to-work conflict, schedule control and family supervisory behavior.

Bold values = p<0.0

There is a significant positive association between work-to-family conflict (WTFC) and cardiometabolic risk; a one-unit increase in self-reported WTFC score was associated with an increase of half a percentage point of CRS risk. These analyses reveal no significant association between family-to-work conflict and cardiometabolic risk score; nor does the FSSB predict the cardiometabolic risk score. In these analyses, women, married employees, and foreign-born employees have reduced risks. We also see that occupational status is negatively associated with risk, in that nurses have lower risks than certified nursing assistants who are more disadvantaged.

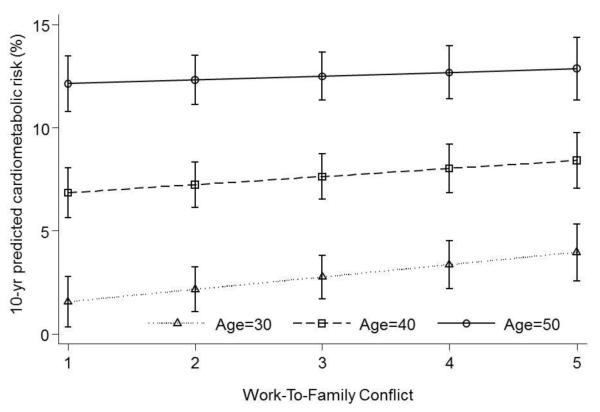

Because age is strongly associated with cardiometabolic risk (Marino et al., 2014), we tested for interactions of age with work-family conflict. We found a statistically significant interaction between age and WTFC (coefficient for interaction term is −0.03, 95% CI=-0.05, −0.01) where increasing WTFC was associated with increasing CRS score among younger aged employees (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adjusted, predicted 10-yr cardiometabolic risk score (±95% CI) interacts with respondent age and presence of children ≤ 18 years in household.

cAge interaction with presence of children figure shows the predictions for US-born, low-income Black females who are CNAs/Other with individual and site-level psychological outcomes centered at zero.

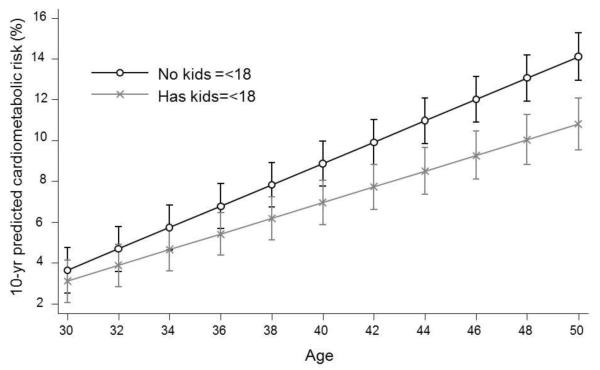

We also found a statistically significant interaction between employee age and having children ≤18 years in the household on cardiometabolic risk (coefficient for interaction term is −0.16, 95% CI=−0.21, −0.10); having no children ≤18 years in the household exacerbated the cardiometabolic risk score associated with age (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Adjusted, predicted 10-yr cardiometabolic risk (±95% CI) showing interaction between individual-level work-to-family conflict and age.

dAge interaction with work-to-family conflict figure shows the predictions for US-born, low-income Black females with kids less than 18 who are CNAs/Other with individual and site-level psychological outcomes centered at zero.

After adjusting for individual and worksite-level characteristics, 2% of the total variance in cardiometabolic risk found in this sample was attributable to the nursing home.

Multi-level analysis of work-family conflict and work-family factors and Sleep duration

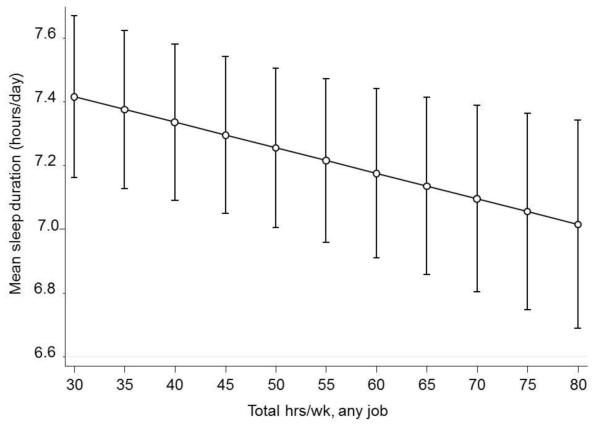

Table 2 shows the results of a multilevel analysis of the same work-family conditions with sleep duration. Our findings indicate Family-To-Work Conflict is associated with shorter sleep duration. For every one unit difference in Family-To-Work Conflict score, employees have about 8 (95% CI: −14.8, −1.3) minutes less of sleep. Work-to-family conflict is actually associated with increased sleep duration, on the order of 5 minutes. In addition, long work hours and having a child under 18 living at home are both strongly associated with shorter sleep durations. In full models controlling for all covariates, employees with children under 18 in the household had an average of almost 11 minutes per night shorter duration of sleep. In fully adjusted models, for every 10 hours of work per week (across all jobs), employees slept almost 5 minutes/night less. Figure 4 shows the relationship between sleep duration and working hours for an average participant in the study.

Figure 4. Total work hours per week across all jobs, and adjusted, actigraphically-measured mean sleep duration.

eSleep figure shows the predictions for US-born, low-income Black females with kids<=18 years old who are CNAs/Other who are mean centered for all individual-level and worksite-level psychological characteristics.

As expected, age and gender were associated with sleep duration. Sleep duration is longer for women than men, and, as age increases, sleep duration decreases. Employees who were white had significantly longer sleep durations than all other race/ethnic groups. As shown in table 2, about 3% of the variation in sleep for these employees is attributable to the worksite.

DISCUSSION

Findings from the Work, Family and Health Network Study in nursing homes illustrate the ways in which work-family conflict is associated with some of the most important health risks to which workers are exposed. This work shows that occupational conditions related to the social environment may take a toll on health, as posited generally by the biopsychosocial and ecosocial frameworks developed by Frankenhaeuser and Krieger (Krieger, 2011). Evidence from our nursing home employees partially supports specific Work- Family conflict theories but also suggests that the current theories do not fully explain the dimensionality with regard to type of work/family interaction per se nor the specificity of the outcomes that we observe. A simple integrating theory that consistently predicts a set of outcomes does not capture the richness and complexity of our findings. Should they be replicated in future studies, they indicate that more theoretical refinement is needed. For instance, as noted by Barnett (1996) and Grzywacz and Marks (2000), most integrating theories of work family interface have focused on conflict. Our findings suggest risks associated with conflict, but we also observe associations with some positive outcomes. For example, sleep duration is positively associated with work-to-family conflict. This may indicate that work roles, even as they have negative spillover to family life, may nonetheless confer advantages related to role accumulation (Martikainen, 1995). Findings in this cross-sectional study of an occupational sample of direct care workers in nursing homes suggest that cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration are both associated with work-family conflict. Confirming theories related to role conflict, cardiometabolic risk is associated with high work-to-family conflict and shorter sleep duration is associated with high levels of family-to-work conflict. Incorporating a full understanding of the multidimensionality of the construct of work-family conflict and the specificity of associations with outcomes flows from the evidence from this current study.

Our second hypothesis related to the positive impact of social support from supervisors was not supported in our study; family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) was associated with neither cardiometabolic risk nor sleep duration. Our third set of hypotheses was partially supported. Long work hours and having young children at home while maintaining full-time paid work were directly related to shorter actigraphically assessed sleep. This cluster of family conditions related to having young children at home and high levels of family conflict spilling over to work may create an environment in which sleep is more precarious. In addition, other work conditions, notably working long hours, socioeconomic disadvantage, lower occupational status and family conditions including being single and having young children at home, are associated with at least one of these cardiometabolic risk or sleep outcomes. These findings suggest that more general theories about stress drawing on biopsychosocial frameworks are central to understanding health in vulnerable populations. Sociodemographic characteristics are associated with cardiovascular risk and sleep duration. Age and gender impact both outcomes. Employees who are foreign-born have lower cardiometabolic risk. These findings are consistent with reports that first generation immigrants from a number of sending countries to the U.S. have lower rates of tobacco and alcohol consumption (Blue & Fenelon, 2011; Lopez-Gonzalez, Aravena, & Hummer, 2005). Participants who identified as black or “other race” race had shorter sleep duration. These findings suggest that the socioeconomic profiles for health vary by outcome, and that health risks faced by such disadvantaged populations are not completely contained in the work measures we included here. Lower occupational status has been shown in women to be associated with increased cardiovascular risk independent of decision authority or demand-control (Wamala, Mittleman, Horsten, Schenck-Gustafsson, & Orth-Gomer, 2000), and, in the same study, work stress was unrelated to cardiovascular disease (Orth-Gomer, et al., 2000), as we observed. Since we have a predominantly female workforce in our study, our findings support the earlier work by Orth-Gomer (Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Cacioppo, & Malarkey, 1998; Orth-Gomer, et al., 2000) and others on the importance of marriage for women. Recent systematic reviews suggest that work stress-related cardiovascular risk is more consistently observed in male samples than in women (Backe, Seidler, Latza, Rossnagel, & Schumann, 2012) whereas marital stress is more important for women (Orth-Gomer, et al., 2000). For sleep, socioeconomic conditions related to neighborhood and other family factors as well as overall job insecurity could well shape patterns of risk of short sleep duration for many people in lower socioeconomic positions (Bartley, 2005; Bartley & Ferrie, 2001; Beatty et al., 2011; Ertel, Berkman, & Buxton, 2011; Hurtado, Sabbath, Ertel, Buxton, & Berkman, 2012; Okechukwu, El Ayadi, Tamers, Sabbath, & Berkman, 2012).

Comparison to other Work, Family Network findings: integrating similar and divergent findings

Our findings are consistent with many of the findings of work-family conflict related to other health outcomes in earlier studies (King, et al., 2013) and make an important contribution by adding directly assessed biomarkers of cardiometabolic risk and sleep duration. Earlier findings from other industries in our network suggest that flexible schedules and interventions aimed at improving employee control over work family issues and schedule control have positive impacts on self-reported health outcomes. (King, et al., 2013; Moen, Kelly, Tranby, et al., 2011) Some of our associations however are different from those using objectively-measured outcomes that we reported in an earlier study of nursing home employees (Berkman, et al., 2010). We discuss these differences in some detail since there are important reasons why we might observe these differences. First, the 30 nursing homes in this study are affiliated with one company with shared common practices while the first study identified a number of nursing homes with distinctly different corporate characteristics (private and for profit, religiously affiliated and non-religiously affiliated). Perhaps most important from our perspective is that supervisory support in this study was a measure based on employee reports of supervisor support (FSSB). In contrast, the earlier study based manager support scores on in-depth qualitative information provided by managers themselves and then linked with employee health outcomes. We suspect that such manager interviews may more accurately reflect actually implementation of family friendly work practices. Second, in our earlier work (Berkman, et al., 2010), we studied a variety of work groups within each nursing home and including night workers, not just those in direct patient care and excluding night workers.

Why might different work family risks be related to specific outcomes in our study?

We suspect that cardiometabolic risk develops over a longer period of time than do patterns of work-related sleep disruption. Therefore, associations between many components of cardiometabolic risk and work-to-family conflict may reflect longer term exposures. Sleep duration however is quite susceptible to short term and acute experiences. Therefore long work hours and having young children at home and family-to-work conflict may well influence sleep duration acutely. Earlier reports in occupational cohorts have also reported that when family demands, measured by the number of dependents, and job strain are coupled together, they are strongly associated with longitudinal increases in sickness absence related to both physical and psychiatric causes (Melchior, Berkman, Niedhammer, Zins, & Goldberg, 2007; Sabbath, Melchior, Goldberg, Zins, & Berkman, 2012).

Limitations and strengths

Our study has both limitation and strengths based on our study design, sample selection and measures. Because our study is cross sectional, we do not have the ability to interpret directionality or causation and it may be that cardiometabolic risks also shape work experiences and patterns of psychological functioning.

Both health-related outcomes were assessed from biological markers of the outcome: actigraphy monitors to assess sleep duration and blood samples, well-calibrated measures of blood pressure, HbA1c, cholesterol and measured BMI contribute to cardiometabolic scores. Thus, while our study is cross-sectional, our two indicators of health outcomes were not influenced by reporting bias. Therefore, it is less likely that psychosocial measures or other common sources of reporting biases confound the associations between these risk factors and indicators of family and work strain. Response rates were high in this study but it is conceivable that those with the highest degree of work-to-family conflict may not have agreed to or been able to participate. We also note that, surprisingly, the measure of sleep duration in this mostly female working population was much higher (7.6 hrs/night, on average) than might be expected from previous studies, or national norms that place adult sleep near 7.0 hrs/night (Hale, 2005; National Sleep Foundation, 2005). This may be in part due to the exclusion of night workers who have been shown to have shorter sleep duration in nursing home samples (Ertel, et al., 2011).

Another limitation of our study is its basis in a single company albeit with numerous facilities in that employees may share more characteristics than is usual in a cross section of total nursing homes in the region. This is also strength of the study, however, in that it provides a common set of policies and practices, thereby limiting exogenous forces that may affect outcomes. We also excluded employees who exclusively work night shifts. But many of our participants worked split shifts, with some of them including evening shifts. We suspect this limitation in enrollment has a conservative bias (if any) on the associations we report since we have limited the experiences and variation in responses to employees and nursing home facilities who all work under more similar conditions to each other than would be if we had enrolled employees in a number of companies or who worked only night shifts. These and other longitudinal studies (e.g., (Jacobsen, Reme, Sembajwe, Hopcia, Stiles, et al., 2014; Jacobsen, Reme, Sembajwe, Hopcia, Stoddard, et al., 2014)) demonstrate a longitudinal association between sleep deficiencies and increased cardiometabolic risk in the long-term, and highlight areas for future research, and workplace interventions.

Our study has many strengths in both design and measurement. This is one of the first studies incorporating examination-based biomarkers of cardiovascular, metabolic risks and sleep duration in a study of work-family conflict in health care workers in the United States, though there is a long research tradition in Scandinavia and much of Europe in this area. By drawing on biomarkers as well as nursing facility level characteristics, we can shed light on work and family dynamics that influence early cardiometabolic risk by setting trajectories of predisease pathways in this primarily female and low and middle-wage workforce.

Conclusion

American women lag in life expectancy behind women in virtually all other industrialized countries (Meara, Richards, & Cutler, 2008; Montez, et al., 2011; Montez & Zajacova, 2013a, 2013b; National Research Council (US) Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries, 2011). The vast majority of these women are in the work force and many are raising children at the same time they are taking care of elders (Neal & Hammer, 2007). This pattern of working while raising a family has increased over time along with the increase in reports of work-family conflict (Kelly, 2003). Furthermore, the increasing number of single parents may make this population even more vulnerable to strains at work. The US lacks coherent work-family policies and practices that may protect these women, and men in similar positions. The division of household labor is also unequal leading to the “second shift” phenomena for women. Informal practices, norms and values which do not lead to balance between work and family may further exacerbate stresses. We may be observing the consequences of these demanding situations, especially for those in low and middle wage jobs who have little flexibility. Our findings inform current work family theories and challenge us to integrate the specificity and dimensionality of work and family dynamics into an expansion of the theoretical frameworks. A fuller incorporation of ecosocial frameworks as expressed by Krieger and ecological theory in relation to the work family nexus as articulated by Grzywacz and Marks are logical launching points. Our next steps are to assess whether The Work, Family and Health Network worksite intervention designed to improve working conditions in these domains will improve health and well-being for these hardworking employees and their families.

Acknowledgments

Support: This research was conducted as part of the Work, Family, and Health Network (www.WorkFamilyHealthNetwork.org), which is funded by a cooperative agreement through the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276), National Institute on Aging (U01AG027669), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL107240), and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (U01OH008788, U01HD059773). Grants from the William T. Grant Foundation, Alfred P Sloan Foundation, and the Administration for Children and Families have provided additional funding. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of these institutes and offices.

Contributor Information

Lisa F. Berkman, lberkman@hsph.harvard.edu Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge. MA Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Sze Yan Liu, szeliu@hsph.harvard.edu Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA..

Leslie Hammer, hammer@pdx.org Department of Psychology, Portland State University, Portland, OR..

Phyllis Moen, phylmoen@umn.edu Department of Sociology and Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN..

Laura Cousino Klein, lcklein@psu.edu Department of Biobehavioral Health and Penn State Institute of the Neurosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA..

Erin Kelly, Kelly101@umn.edu Department of Sociology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN..

Martha Fay, mfay@hsph.harvard.edu Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Kelly Davis, kdavis@psu.edu Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA..

Mary Durham, Mary.durham@kpchr.org The Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente, Portland, OR.

Georgia Karuntzos, gtk@rti.org Behavioral Health and Criminal Justice Research Division, RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC..

Orfeu M. Buxton, Orfeu_buxton@hms.harvard.edu Department of Biobehavioral Health and Penn State Institute of the Neurosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA; Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, Harvard University, Cambridge. MA; Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Division of Sleep Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

References

- Arber S, Gilbert GN, Dale A. Paid employment and women’s health: A benefit or a source of role strain? Sociology of Health & Illness. 1985;7(3):375–400. [Google Scholar]

- Artazcoz L, Borrell C, Benach J. Gender inequalities in health among workers: the relation with family demands. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2001;55(9):639–647. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.9.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano M, Glymour MM, Banks J, Mackenbach JP. Health disadvantage in US adults aged 50 to 74 years: a comparison of the health of rich and poor Americans with that of Europeans. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(3):540–548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139469. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backe EM, Seidler A, Latza U, Rossnagel K, Schumann B. The role of psychosocial stress at work for the development of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85(1):67–79. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0643-6. doi: 10.1007/s00420-011-0643-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, Cronin JW, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Czeisler CA. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Baruch GK. Women’s involvement in multiple roles and psychological distress. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1985;49(1):135–145. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M. Job insecurity and its effect on health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(9):718–719. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.032235. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.032235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley M, Ferrie J. Glossary: unemployment, job insecurity, and health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2001;55(11):776–781. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.11.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty DL, Hall MH, Kamarck TA, Buysse DJ, Owens JF, Reis SE, Matthews KA. Unfair treatment is associated with poor sleep in African American and Caucasian adults: Pittsburgh SleepSCORE project. Health Psychology. 2011;30(3):351–359. doi: 10.1037/a0022976. doi: 10.1037/a0022976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Buxton OM, Ertel K, Okechukwu C. Manager’s practices related to work-family balance predict employee cardiovascular risk and sleep duration in extended care settings. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2010;115(3):316–329. doi: 10.1037/a0019721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, O’Donnell EM. The pro-family workplace: Social and economic policies and practices and their impacts on child and family health. In: Landale NS, McHale SM, Booth A, editors. Families and Child Health. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Berntsson L, Lundberg U, Krantz G. Gender differences in work-home interplay and symptom perception among Swedish white-collar employees. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(12):1070–1076. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042192. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S, Milkie MA. Work and Family Research in the First Decade of the 21st Century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):705–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bratberg E, S D, E. RA. The double burden: Do combinations of career and family obligations increase sickness absence among women? Eur Sociological Rev. 2002;18:233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JW, Kelly E, Hammer LB, Almeida DM, Dearing JW, Berkowitz King R, Buxton OM. An integrative, multilevel, and transdisciplinary research approach to challenges of work, family, and health. RTI Press; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstrom B, Whitehead M, Clayton S, Fritzell S, Vannoni F, Costa G. Health inequalities between lone and couple mothers and policy under different welfare regimes - the example of Italy, Sweden and Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(6):912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.014. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton OM, Hopcia K, Sembajwe G, Porter JH, Dennerlein JT, Kenwood C, Sorensen G. Relationship of sleep deficiency to perceived pain and functional limitations in hospital patient care workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(7):851–858. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824e6913. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31824e6913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon WB. The Wisdom of the Body. Norton; New York: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Casini A, Godin I, Clays E, Kittel F. Gender difference in sickness absence from work: a multiple mediation analysis of psychosocial factors. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(4):635–642. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks183. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. Demographic Trends in the United States: A Review of Research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B, Schnall P, Ko S, Dobson M, Baker D. Job strain and coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2013;381(9865):448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60242-1. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60243-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaske S. For the family? How class and gender shape women’s work. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ertel KA, Berkman LF, Buxton OM. Socioeconomic status, occupational characteristics, and sleep duration in African/Caribbean immigrants and US white health care workers. Sleep. 2011;34(4):509–518. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, Marklund S, Wikman A. Work status, work hours and health in women with and without children. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;66(10):704–710. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044883. doi: 10.1136/oem.2008.044883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser M. A biopsychosocial approach to work life issues. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(4):747–758. doi: 10.2190/01DY-UD40-10M3-CKY4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser M, Gardell B. Underload and overload in working life: outline of a multidisciplinary approach. J Human Stress. 1976;2(3):35–46. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1976.9936068. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1976.9936068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser M, Johansson G. Stress at work: Psychobiological and spychosocial aspects. Int. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 1986;35:287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser M, Lundberg U, Fredrikson M, Melin B, Tuomisto M, Myrsten AL, Wallin L. Stress on and off the job as related to sex and occupational status in white - collar workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1989;10(4):321–346. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzell S, Vannoni F, Whitehead M, Burstrom B, Costa G, Clayton S, Fritzell J. Does non-employment contribute to the health disadvantage among lone mothers in Britain, Italy and Sweden? Synergy effects and the meaning of family policy. Health Place. 2012;18(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.007. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone M, Russell M, Cooper M. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: a four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1997;70(325):336. [Google Scholar]

- Frye NK, Breaugh JA. Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, workfamily conflict, family-work conflict, and satisfaction: a test of a conceptual model. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2004;19(2):197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gardell B. Scandinavian research on stress in working life. Int J Health Serv. 1982;12(1):31–41. doi: 10.2190/K3DH-0AXW-7DCP-GPFM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gornick J, Meyers MK. Families that Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. Russell Sage Foundation Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick J, Meyers MK, Ross KE. Supporting the employment of mothers: policy variation across fourteen welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy. 1997;7:45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10(1):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Marks NF. Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: an ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5(1):111–126. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L. Who has time to sleep? J Public.Health (Oxf.) 2005;27(2):205–211. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Allen E, Grigsby T. Work-family conflict in dual-earner couples: Within-individual and crossover effects of work and family. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1997;50:185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Anger WK, Bodner T, Zimmerman K. Clarifying work-family intervention process: the roles of work-family conflict and family supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;96(1):134–150. doi: 10.1037/a0020927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Bodner T, Crain T. Measurement development and validation of the family supportive supervision behavior short-form (FSSB-SF) Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032612. doi: doi: 10.1037/a0032612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Yrgaui NL, Bodner TE, Hanson GC. Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB) Journal of Management. 2009;35(4):837–856. doi: 10.1177/0149206308328510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer LB, Sauter S. Total worker health and work-life stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2013;55(12 Suppl):S25–29. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000043. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann SJ. The widening gap: Why America’s working families are in jeopardy and what can be done about it. Basic Books; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado DA, Sabbath EL, Ertel KA, Buxton OM, Berkman LF. Racial disparities in job strain among American and immigrant long-term care workers. International Nursing Review. 2012;59(2):237–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00948.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen HB, Reme SE, Sembajwe G, Hopcia K, Stiles TC, Sorensen GP, J.H., Buxton OM. Work stress, sleep deficiency and predicted 10-year cardiometabolic risk in a female patient care worker population. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ajim.22340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen HB, Reme SE, Sembajwe G, Hopcia K, Stoddard AM, Kenwood C, Buxton OM. Work-family conflict, psychological distress, and sleep deficiency among patient care workers. Workplace health & safety. 2014;62(7):282–291. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20140617-04. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20140617-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson G. Job demands and stress reactions in repetitive and uneventful monotony at work. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(2):365–377. doi: 10.2190/XYP9-VK4Y-9H80-VV3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson G. Work-Life Balance: the Case of Sweden in the 1990s. Social Science Information. 2002;41:303. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson M, Heijbel B, Voss M, Alfredsson L, Vingard E. Influence of self-reported work conditions and health on full, partial and no return to work after long-term sickness absence. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health. 2008;34(6):430–437. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce K, Pabayo R, Critchley JA, Bambra C. Flexible working conditions and their effects on employee health and wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(2):Cd008009. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008009.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adminstr. Sci. Q. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(7):694–705. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy Work, Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Basic Books; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: inplications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson BH, Knutsson AK, Lindahl BO, Alfredsson LS. Metabolic disturbances in male workers with rotating three-shift work. Results of the WOLF study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2003;76(6):424–430. doi: 10.1007/s00420-003-0440-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL. The strange history of employer-sponsored child care: interested actors, uncertainty, and the transformation of law in organization fields. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;109(3):606–649. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL. Work-Family Policies: The United States in International Perspective. In: Pitt-Catsouphes M, Kossek EE, Sweet S, editors. The Work and Family Handbook: Multidisciplinary Perspectives and Approaches. Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P. Rethinking the clockwork of work: why schedule control may pay off at work and at home. Advances in Developing Human Resources. 2007;9(4):487–506. doi: 10.1177/1523422307305489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EL, Moen P, Oakes M, Fan W. Changing work and work-family conflict in an information technology workplace: evidence from a group-randomized trial. American Sociological Review. (Accepted) [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Cacioppo JT, Malarkey WB. Marital stress: immunologic, neuroendocrine, and autonomic correlates. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:656–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig DA, Cheng ER. Even as mortality fell in most US counties, female mortality nonetheless rose in 42.8 percent of counties from 1992 to 2006. Health affairs. 2013;32(3):451–458. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0892. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RB, Karuntzos GT, Casper LM, Moen P, Davis KD, Berkman L, Kossek EE. Work-family Balance Issues and Work-Leave Policies. In: Gatchel RJ, Schultz IZ, editors. Handbook of Occpational Health and Wellness. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 323–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kivimaki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, Fransson EI, Heikkila K, Alfredsson L, Theorell T. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet. 2012;380(9852):1491–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60994-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE. Workplace policies and practices to support work and families. In: Bianchi SM, King BR, editors. Work, Family, Health, and Well-being. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Barber AE, Winters D. Using Flexible Schedules in the Managerial World: The Power of Peers. Human Resource Management. 1999;38(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Hammer LB. Supervisor work/life training gets results. Harvard Business Review. 2008 Nov; 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossek EE, Hammer LB, Kelly E, Moen P. Designing work, family & health organizational change initiatives. Organizational Dynamics. 2014;43:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Epidemiology and People’s Health: Theory and Context. Oxford University Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan CP, Lockley SW, Czeisler CA. Interns’ Work Hours. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(7):726–728. [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N.Engl.J Med. 2010;363(22):2124–2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan CP, Rothschild JM, Cronin JW, Kaushal R, Burdick E, Katz JT, Czeisler CA. Effect of reducing interns’ work hours on serious medical errors in intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1838–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsbergis P, Schnall P. Job strain and coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2013;381(9865):448. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60243-3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Rathouz PJ, Hulley SB, Sidney S, Liu K. Objectively measured sleep characteristics among early-middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;164(1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidwall U, Marklund S, Voss M. Work-family interference and long-term sickness absence: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(6):676–681. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp201. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U, Mardberg B, Frankenhaeuser M. The total workload of male and female white collar workers as related to age, occupational level, and number of children. Scand J Psychol. 1994;35(4):315–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.1994.tb00956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luyster FS, Strollo PJ, Jr., Zee PC, Walsh JK. Sleep: a health imperative. Sleep. 2012;35(6):727–734. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1846. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M, Li Y, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Berkman LF, Buxton OM. Quantifying cardiometabolic risk using modifiable non-self-reported risk factors. American journal of preventive medicine. 2014;47(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.006. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino M, Li Y, Rueschman MN, Winkelman J, Ellenbogen J, Solet JM, Buxton OM. Measuring sleep: Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of wrist actigraphy compared to polysomnography. Sleep. 2013;36(11):1747–1755. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3142. doi: doi: 10.5665/sleep.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P. Women’s employment, marriage, motherhood and mortality: a test of the multiple role and role accumulation hypotheses. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(2):199–212. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981-2000. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):350–360. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, Zins M, Goldberg M. The mental health effects of multiple work and family demands: A prospective study of psychiatric sickness absence in the French GAZEL study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:573–582. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0203-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. It’s About Time: Couples and Careers. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Kelly EL, Hill R. Does Enhancing Work-Time Control and Flexibility Reduce Turnover? A Naturally Occurring Experiment. Social Problems. 2011;58(1):69–98. doi: 10.1525/sp.2011.58.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Kelly EL, Lam J. Healthy work revisited: Do changes in time strain predict well-being? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2013;18(2):157–172. doi: 10.1037/a0031804. doi: 10.1037/a0031804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Kelly EL, Tranby E, Huang Q. Changing work, changing health: can real work-time flexibility promote health behaviors and well-being? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(4):404–429. doi: 10.1177/0022146511418979. doi: 10.1177/0022146511418979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]