Abstract

Objective

While representing only 25% of the sexually active population, 50% of all new STI infections occur among young people, mostly due to inconsistent condom use. Critically, the majority of adolescent sexual activity takes place in the context of romantic relationships, thus it is important to understand how relationship factors may influence decision-making about the use, or not, of protection.

Method

We utilized a mixed method approach to investigate the extent to which relationship length, degree of trust or love in the relationship, and frequency of intercourse influence both perceptions of the probability of condom use and self-reported condom use in the context of relationships among a diverse sample of high risk adolescents (ages 12–19).

Results

Participants were least likely to use condoms if they were in relationships with high trust/love and high frequency of intercourse. Importantly, sexual experience status was a strong moderator of primary effects.

Conclusion

The perspective of motivated cognition provides a useful theoretical framework to better understand adolescent decision-making about condom use, particularly for sexually experienced youth.

Keywords: HIV/STIs, condoms, adolescents, sexual behavior, romantic relationship

INTRODUCTION

Romantic relationships are an important and normative component of adolescence necessary for the natural transition to healthy, adult, long-term relationships e.g., 1. From this perspective, consensual adolescent sexuality and sexual debut are not viewed as inherent health risks, but rather typical aspects of normative development2. This perspective is particularly relevant as the average time between puberty and marriage lengthens3.

At the same time, sexual behavior still requires protective measures to prevent the occurrence of unintended, serious health consequences, including unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)4. In terms of public health relevance, 40% of young people under the age of 25 currently engage in unprotected sexual intercourse. As a result, despite comprising only 25% of the sexually active population, 50% of all new STI infections occur in this age group4.

Although adolescents’ knowledge regarding HIV/STI transmission and prevention is generally quite good5, there is a poorly-understood disconnect between this knowledge and youths’ decision-making. Knowledge about sexual risk does not, in fact, translate to protected health behavior including condom use6. Further, evaluation of traditional psychosocial constructs including attitudes, intentions, norms, and self-efficacy about condom use show promise7, but do not fully account for this behavioral gap5.

Notably, relationship factors consistently emerge in qualitative work concerning health behavior in high-risk youth. Youth decision-making about condom use appears to be intricately tied to interpersonal emotional issues within romantic and sexual relationships, rather than via more global cognitive models of risk8. Thus, relationship factors are likely to play a large role in adolescent condom use9. However, relationship factors have been under-evaluated in this age group. In one of the few studies with adolescents, Walter and colleagues found that while cognition predicted intention, relationship characteristics were stronger predictors of actual condom use behavior10. Moreover, studies with adults show the devastating consequences of the misperception that condom use in relationships reflects a lack of trust11.

In particular, predominantly assessed via survey methodology, across adolescent and adult studies, three relationship factors have been widely implicated in condom use in relationship contexts12–16: (1) length of the relationship inversely associated with the frequency of condom use, (2) frequency of intercourse, with more frequent sex correlating with less condom use, and (3) level of “trust” or “love” in the relationship, which is less well-understood, but may reflect the representation that youth in long-term monogamous relationships should not “need” condoms because of trust. Equally possible, youth may believe that condom interferes with intimacy, including true “love”, where should be no physical or emotional barriers. The result is that youth may fear introducing condom use, particularly in an established relationship in which they have not been used before, because they may potentially suggest a lack of trust and commitment, and/or evidence that the partner was unfaithful17.

However, we could find no published quantitative or qualitative studies regarding how relationship length, intercourse frequency, or level of trust or love influenced adolescent decision-making in the context of condom use. Further, relationship factors are not widely incorporated within traditional sexual risk reduction programming for adolescents. Yet, if relationship factors are an important part of the social construction of adolescent sexuality, then it would be highly beneficial to develop interventions that seek to change them. On the other hand, these perceptions may develop as a response to other, less-well studied relationship factors, such as sexual experience. Compellingly, we could also find no published literature regarding whether or how sexual experience status may moderate potential associations between adolescent relationship factors and condom use.

Additionally, at this time, the published literature examining relationship influences on adolescent condom use has generally sampled sexually active youth or collapsed analyses across level of sexual experience. The result is a substantive omission regarding differentiation between sexually experienced and non-experienced participants, which is critical in light of recent recommendations to administer interventions prior to the initiation of sexual activity to achieve maximal effectiveness18.

Thus, our approach directly responds to and addresses a current gap in the literature, by using two-study (Study 1a and Study 1b) approach that facilitates a mixed-method examination of whether perceptual biases and heuristics are instantiated prior to sexual initiation or are shaped by sexual activity. More specifically, this approach facilitates a direct quantitative evaluation of empirical factors, as well as the use of vignette methodology to evaluate youths’ responses to hypothetical relationship situations. This innovative approach allows us to access and evaluate youths’ responses to relationship scenarios without relying on youth to be sexually active. This enables a finer-grained exploration of the impact of relationship factors on planned condom use more effectively, particularly in youth who have not yet initiated sexual activity. Thus, we hypothesized that sexually experienced youth would be more likely than non-experienced youth to perceive pragmatic constraints (e.g., high frequency of intercourse) and relationship factors (e.g., length of relationship, trust and love) as obstacles to condom use.

Empirical and qualitative reports of relationship-based decision-making about condom use suggest that relationship factors may vary for adolescent girls versus boys16, 19. A secondary goal of this project was thus to investigate the potential moderating effect of gender on the influence of relationship characteristics on condom use. In line with this work, we hypothesized that relationship factors (e.g., length of relationship, trust and love) might have a greater influence on the perception of condom use and actual use of condoms among girls, as compared with boys.

METHODS

STUDY 1A

Participants

Five hundred and six students (60% female) were drawn from a larger sample of 1,920 inner city high school students5. Eligibility criteria included in this component, youth had to report: a) currently being in a relationship and b) having sexual intercourse with that partner. The mean age for this subsample was 15.8 (range 12 to 19 years); 47% were African American, 29% were Hispanic, 2% were Caucasian, <1% Asian American, 2% were Native American, and 19% “mixed” or “other”. In terms of sexual orientation, 96.23% of the male sample reported only wanting to have sex with women, 2.64% reported only wanting to have sex with men, and 1.13% reported wanting to have sex with either women or men. For the girls in this sample, 97.48% reported only wanting to have sex with men, 1.12% reported only wanting to have sex with women, and 1.40% reported wanting to have sex with either women or men. Of these sexually active participants, 19% reported using condoms consistently (i.e., 100% of the time in their lifetime). This sample also reported a high percentage of prior pregnancies (being or getting pregnant; 20% of females; 15% of males).

Procedure

Youth in this study were part of a large-scale, multi-year HIV prevention project5. Passive consent was obtained by mailing a description of the study to the students’ parent or guardian of record. Parents/guardians were instructed to contact the school or the research team if they did not want their child to participate (<1%). Students completed the study in their homeroom class. Students who did not wish to participate (<5%) were given alternate tasks or allowed to work on homework. All procedures were approved by the participating Institutional Review Board and relevant school district officials. Each analysis was based on participants with complete data for the relevant items.

Measures

Condom use in relationships

Participants were asked if they were currently in a relationship, and how long they had been in this relationship. They were asked if they had had intercourse with this partner, and whether they had used condoms at the beginning of the relationship. They were also asked how frequently they currently used condoms with their partner on a 1–5 scale ranging from 1= “never” to 5= “every time we have sex”. Participants were queried regarding how frequently they had intercourse with their partner on a 1–5 scale ranging from 1= “once a month” to 5= “almost every day”. Finally, to assess “love” and “trust”, participants reported how much trust existed in their relationship (1–4 scale from 1= “no trust at all” to 4= “a lot of trust”) and whether they were “in love” (yes/no) with their partner.

STUDY 1A RESULTS

Duration of relationship

Of the 506 youth, 464 (92%) reported their current relationship length, with a median of 8 months (M = 11 months, range < 1 to 48 months). All 506 youth rated the trust in their relationship as quite high (M = 3.61 on a 4-point scale), reflecting a potential ceiling effect with 63% indicating “a lot of trust” and 29% “some trust.”) Most (64%) of the 489 participants reported being “in love” with their partner.

Frequency of intercourse and condom use

Of the 506 participants, 82% reported initially using condoms with their partner, which decreased to a 53% rate of consistent condom use currently. In terms of intercourse frequency (n = 475), 30% reported having sex “once a month”; 26% “once a week”; 28% “2–3 times a week”; 7% “4–5 times a week”; and 9% “almost every day”.

Correlates of condom use in relationship

Table 1 includes correlations for all variables of interest. Condom use was inversely related to intercourse frequency, relationship length and love. No relation emerged between trust and condom use, or between love and intercourse frequency. We found significant gender differences, whereby adolescent girls reported significantly longer relationship length, a higher likelihood of being “in love” with partners, and less condom use.

TABLE 1.

Correlations among relationship variables among adolescents in sexual relationships with complete data for all variables (n=432)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (1=male, 0=female) | -- | |||||

| 2. Frequency of intercourse (1=once a month to 5=almost every day) | .02 | -- | ||||

| 3. Level of trust (1=none at all to 4=a lot) | −.02 | −.02 | -- | |||

| 4. Length of relationship (in months) | −.15** | .04 | .11* | -- | ||

| 5. In love with partner (1=yes, 0=no) | −.18*** | .09 | .24*** | .30*** | -- | |

| 6. Condom use with partner (1=never to 5=every time we have sex) | .12* | −.32*** | −.03 | −.12* | −.17** | -- |

| Mean | .34 | 2.39 | 3.61 | 11.51 | .80 | 3.82 |

| Standard Deviation | .48 | 1.21 | .66 | 9.95 | .40 | 1.52 |

We then regressed current condom use on relationship length, intercourse frequency, trust, love, and gender. Both intercourse frequency (B = −.31, p < .001) and love (B = −.10, p < .05) were significantly negatively related to condom use. More frequent intercourse and a higher likelihood of being in love were inversely associated with condom use frequency. Compellingly, gender significantly predicted condom use over and above relationship factors (B = .10, p < .05). Boys reported condom use more frequently than girls. This model accounted for 14% of the variance in condom use (a moderate effect size)20.

Next, we explored moderating effects of gender by computing interaction terms for each of the four relationship factors (relationship length, intercourse frequency, trust, love) within four separate models, each time including only the newly computed interaction terms, to avoid multicollinearity among the interaction terms. Because of the use of multiple tests and the exploratory nature of these analyses, we used a Bonferroni correction for alpha, setting familywise error at .05 (p-value <.01). Only the gender X intercourse frequency interaction was significant (B = .12, R2Δ = .02, p = .01), suggesting that the relation between intercourse frequency and frequency of condom use is much stronger for girls (B = −.48, p < .001), versus boys (B = −.15, p = .15).

STUDY 1B

As suggested by Wulfert and Biglan21, we wanted to evaluate the relative strength of relationship factors in youths’ decision-making about condom use. But given the inherent collinearity between relationship factors, a stronger approach to assessing their relative strength is to randomly assign levels of each factor and assess their effects. Because this is obviously not possible in the context of actual adolescent relationships, we utilized hypothetical vignettes22, 23 within Study 2 to evaluate the strength of: (a) duration of the relationship (two weeks versus four months), (b) level of trust in the relationship (high trust versus low trust), (c) intercourse frequency (often versus not very often), and (d) sexual experience. As opposed to existing relationships in which sex is occurring, the use of hypothetical vignettes allowed us to examine the effects of sexual experience on these judgments. Participants read scenarios depicting an adolescent couple who has the opportunity to have sex, and then estimate the likelihood of their condom use.

Participants

The full sample of 1,920 participants from Fisher et al 5 participated in Study 2, including the 506 participants of Study 1. Slightly over half of the 1,920 participants (55%) were female, and the mean age was 15.6 (range 12 to 19 years). This was an ethnically diverse, relatively sexually active sample with high rates of risky sexual behavior (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographics of full high school sample (n=1,920)

| Variable | High School Students |

|---|---|

| Age | 15.6 (1.04) |

| Gender | |

| % Male | 45% |

| % Female | 55% |

| Race | |

| %Hispanic | 31% |

| %African American | 44% |

| %Caucasian | 4% |

| %Asian American | 2% |

| %Native American | 1% |

| %Mixed/Other | 18% |

| % Sexually active | 53% |

| Age at first intercourse | 13.6 (1.55) |

| % Consistent condom use | 20% |

| % Experienced pregnancy | |

| Male | 8% |

| Female | 18% |

Design

We designed the description of intercourse frequency (often or not very often), trust (high or low), and length of the relationship (two weeks or four months) in a 2×2×2 between subjects factorial design. Participant gender served as an additional between-subjects variable. To explore the differences in sexual experience, we conducted analyses separately for sexually experienced (n = 1026) versus non-experienced youth (n = 894).

The core scenario depicted a young couple with the opportunity to have intercourse (Figure 1); combinations of each independent variable produced 8 distinct scenarios. Each participant read this scenario and estimated the probability that the couple used a condom if they had sex (from 1= “no chance they will use a condom” to 5= “they will definitely use a condom”).1 We present conventional significance tests plus an effect size for each effect (Cohen’s f) 20.

Figure 1.

Study vignette

Full factorial ANOVAs (frequency X trust X length X gender) were carried out separately for 3 strata of youth: (1) n = 1,026 students who had ever had sexual intercourse (sexually-experienced youth); (2) n = 506 students from Study 1a who reported currently being in a sexually active relationship (current relationship youth); (3) n = 894 youth who had not yet initiated intercourse (sexually-inexperienced youth).

(1) Sexually experienced youth

In the full ANOVA, gender did not interact with any of the other variables; thus, we simplified the model, retaining gender as a covariate and excluding interaction terms involving gender.

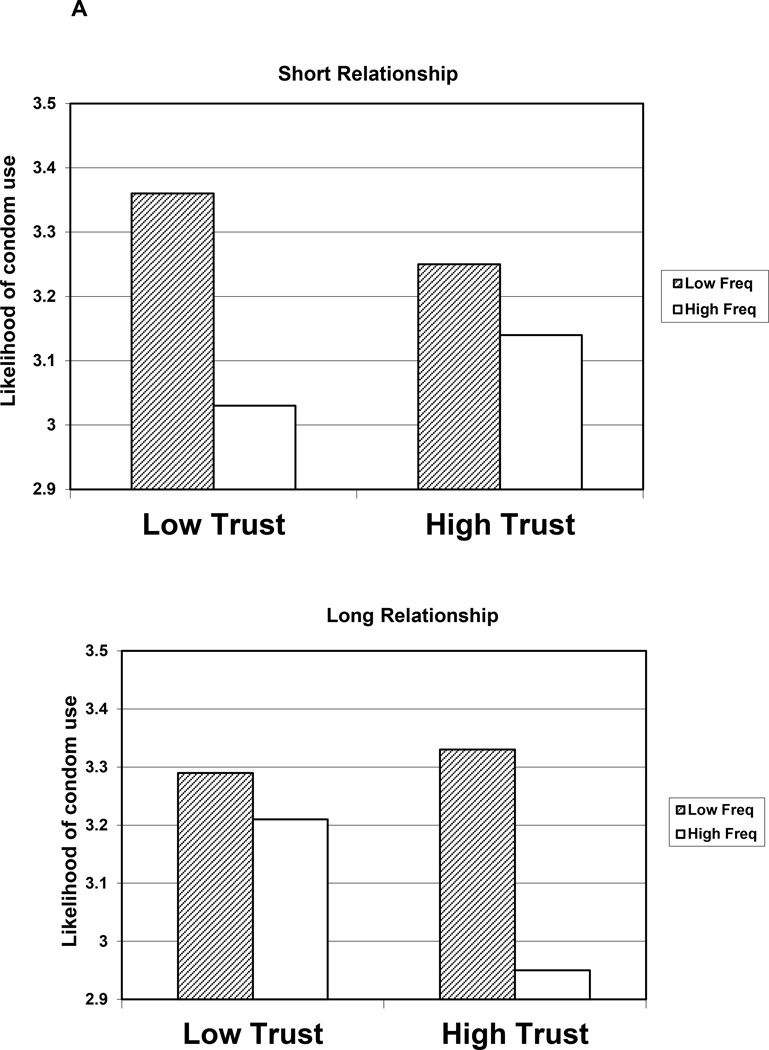

When asked about likelihood of condom use, we observed a significant three-way interaction between trust, relationship length, and intercourse frequency, F (1,992) = 5.12, p < .05, f=.07 (Figure 2a), wherein youth reported that condom use was most likely in new relationships, with low trust and low intercourse frequency. Conversely, they estimated that condom use was least likely in long-duration relationships with high trust and high intercourse frequency. The largest single effect was the main effect of intercourse frequency. Regardless of trust or relationship length, condom use was more likely when intercourse frequency was low, F (1,992) = 15.22, p < .001, f=.13. There were no main effects for trust (F (1,992) = .85, p =.36, f=.03), relationship length (F (1,992) = .01, p =.93, f=.00), or gender, F (1,992) = .81, p =.37, f=.03.

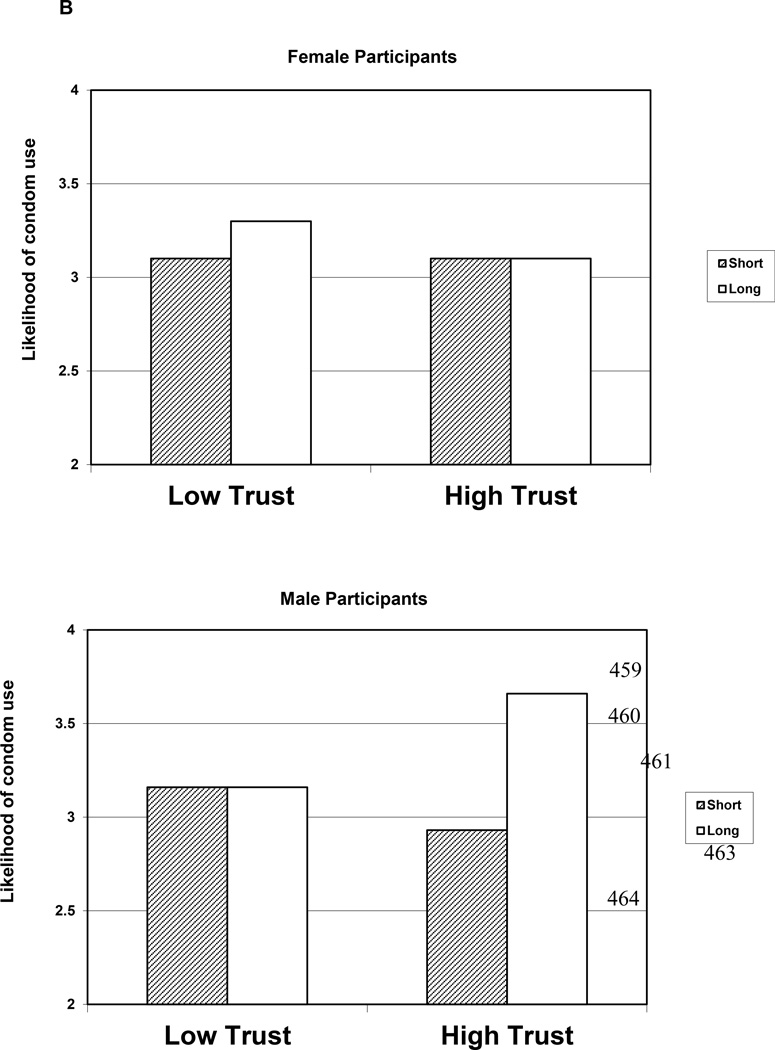

Figure 2.

A. For sexually active adolescents, the three-way interaction of the effects of trust, relationship length, and intercourse frequency on judgments on projected condom use for hypothetical couple.

B. For non-experienced adolescents, the main effect of relationship length.

(2) Current Relationship Youth

As currently being in a romantic and sexually-active relationship might influence perceptions, we repeated the analyses with adolescents from Study 1a who were in a current relationship. Among this subsample, there was a main effect for intercourse frequency, F (1,399) = 3.84, p <.05, f=.11. Youth estimated that condom use was more likely for infrequent intercourse. Notably, within this subset of youth, there was also a main effect for trust, F (1,399) = 3.05, p <.05, f=.10. Youth estimated that condom use was more likely in contexts with low relationship trust. These main effects were moderated by a three-way interaction of gender X intercourse frequency X relationship length that approached significance, F (1,399) = 3.71, p =.054, f=.10, reflecting gender differences in perceptions of condom use (females = more likely; males = less likely) in new relationships with infrequent sex.

(3) Sexually inexperienced youth

We found a main effect for relationship length, F (1, 860) = 11.92, p < .001, f=.12, whereby sexually inexperienced youth judged that condom use was more likely in longer-duration relationships. We found that this association was moderated by gender, F (1, 860) = 3.94, p < .05, f=.07. In other words, sexually inexperienced boys believed that condom use was more likely in longer relationships. Even further, we found evidence for a three-way interaction of trust, length, and gender, illustrated in Figure 2b, F (1, 860) = 11.92, p < .001, f=.12. In sum, sexually inexperienced boys believed that condom use was most likely in high trust, longer-duration relationships. Adolescent girls, on the other hand, believed condom use to be most likely in low trust, longer-duration relationships. Finally, in contrast to the other two samples, there was no main effect for intercourse frequency within this group.

DISCUSSION

At this time, there are two notable gaps in the adolescent HIV risk reduction literature. To begin, there are few published studies evaluating relationship factors within models of adolescent decision-making about condom use. Further, few research teams have employed vignette methodology to explore youths’ responses to hypothetical relationship situations. This approach circumvents the need to rely on youths’ actual relationship experience, in order to evaluate the perspectives of both sexually-naïve, as well sexually experienced, adolescents. We therefore employed a two-study (Study 1a and Study 1b) mixed-method design to evaluate whether perceptual biases and heuristics may be instantiated prior to sexual initiation or shaped by sexual activity. We found that among sexually active adolescents, more frequent intercourse, higher ratings of being “in love” with a partner, and longer relationship duration were strongly associated with less condom use. Further, when asked about their perceptions of their potential to use condoms in hypothetical relationships, intercourse frequency emerged as the strongest predictor of potential condom use, with lower condom use particularly in long relationships of high trust and high intercourse frequency. This was true for all groups except sexually inexperienced youth. For sexually inexperienced youth, we observed significant gender differences, wherein sexually-inexperienced boys believed that condom use was most likely in high trust, longer duration relationships, whereas sexually-inexperienced girls anticipated greater condom use in low-trust, longer-duration relationships.

Perceptions of condom use probability within the vignettes were strongly influenced by whether or not youth were sexually experienced. Sexually experienced adolescents focused largely on the pragmatic aspect of intercourse, inferring that couples with frequent intercourse were less likely to use a condom. Moreover, condom use was judged least likely to occur in relationships of long duration and high trust. Sexually inexperienced youth, and in particular male sexually-inexperienced adolescents, anticipated the opposite association observed in the sexually active group, wherein condom use was expected to be highest in relationships of longer duration and high trust. The absence of a main effect for intercourse frequency on this subsample’s condom use estimates is not surprising, given that sexual intercourse is often veiled in myth and secrecy for many adolescents24. The result is that sexually inexperienced youth may be missing critical information about the nature of sexual activity and relationships. In line with prior work in this field25, we suggest that this finding signals the need for tailored theorizing and intervention content for adolescents who have, versus who have not, had sex5. Related, a critical piece in this equation is how to convey information about sexual risk to sexually inexperienced youth before they have sex18. Based on the data we observed here, we suggest that prevention interventions may require different format than for sexually-experienced youth who may already have gained at least preliminary practice communicating about condom use26.

Gender emerged as a significant moderator within many of our analyses. To that end, sexually active adolescents currently in relationships judged that condom use would be highest in brief, low frequency intercourse relationships, which may represent “casual sex”, “hook-ups”, or “booty-calls”27. Adolescent females who were currently in relationships also reported a stronger effect of intercourse frequency on their own condom use as compared with adolescent males. Following other work in this area28, we believe that this may reflect the inherent challenges and control issues that emerge in the dyadic nature of the practical negotiating of another person’s condom use versus one’s own, which typifies female versus male condom use. Arguably, this may also represent adolescent females’ transition to other forms of protection, particularly in higher intimacy relationships29.

In general, these findings highlight both pragmatic and emotional concerns in adolescent relationship-based condom use. For adolescents who have intercourse frequently, it may be more difficult to consistently have condoms on hand when needed, and to always be sure to stop to use one. As observed by our findings here, this problem may be magnified by social constructions that associate condom use with infidelity, promiscuity, and a lack of trust or love in a relationship17. As young people begin to love and trust their partners, they may transition to a belief that condom use is unnecessary and further, may be a barrier to the emotional and physical connection they desire12. Given that these early adolescent romantic relationships may represent a “training ground” of sorts for learning how to be a romantic partner, and that adolescent relationships tend to be of relatively short duration, it is would not be surprising for these young people to be particularly attuned to and wary of potential threats to their developing relationships.

Our data point to important crucial formative factors including frequency of intercourse and learning to love and trust a partner. While these developments may help youth form and maintain successful romantic relationships, they may also play a direct role in the abandonment of condom use. Condom use is an interpersonal behavior that is laden with social constructions and consequences7, particularly in the context of adolescent romantic relationships. Thus, research on adolescent condom use that focuses exclusively on individual motivations, while certainly an important piece of the puzzle, may not produce a complete picture of the determinants of the behavior, especially for female youth30. Rather, adolescence is a critical period where it may be particularly important and timely to disabuse teens of potential misconceptions about how condom use may negatively impact their fledgling relationships.

Despite the strengths of this study, including the large sample size, the mixed methods design, and the examination by gender, findings should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. The self-report and cross-sectional nature of the data and the lack of partner verification in the couples’ data represent the primary weaknesses; in other words, we cannot draw any causal conclusions regarding relationship/condom use data from Study 1a. However, these data also point to directions for future work. In other words, educational campaigns have been very successful at associating condoms with disease prevention, but still require finer-grained approaches to determine how best to tailor information to this age group, by sexual-experience, and by gender31. Further, we did not query the age of adolescents’ sexual partners in this study; however, gaining a finer-grained understanding of the nature of adolescent relationships, particularly among adolescent females with older male partners, and adolescent males with younger female partners, will provide critical windows into more effective ways to help youth navigate relationship factors in disparate-age sexual relationships. In addition, traditional campaigns have only been so effective in disseminating these critical information to youth; one avenue that may hold promise for sharing these messages by target community is electronic or social media venues32 whereby it may be possible to shape the social construction of condom use to be framed more positively. Consequently, it may be important to address condom use in these contexts, including “serious” relationships, and those that vary across degree of love and trust. As romantic relationships are highly important to adolescents, this may prove an important way to help youth weigh maintaining stable romantic relationships with issues of health protection.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no competing financial or other conflicts of interest relating to the data included in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sarah Feldstein Ewing, 1 University of New Mexico, MSC09 5030, Department of Psychiatry, Albuquerque, NM 87131, UNITED STATES, 5052725197, mobile: 5052725197, FAX: 5059252301, swfeld@unm.edu.

Angela D Bryan, University of Colorado at Boulder.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grover RL, Nangle DW. Introduction to the special section on adolescent romantic competence: Development and adjustment implications. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:485–490. doi: 10.1080/15374410701649342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolman DL, McClelland SI. Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:242–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finer LB, Philbin JM. Trends in ages at key reproductive transitions in the United States, 1951–2010. Women's Health Issues. 2014;24:e271–e279. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Prevention CfDCa. 2013. Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepitits, STDs, and TB: Hispanic/Latinos. (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychology. 2002;21:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollack LM, Boyer CB, Weinstein ND. Perceived risk for sexually transmitted infections aligns with sexual risk behavior with the exception of condom nonuse: data from a nonclinical sample of sexually active young adult women. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40:388–394. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318283d2e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montanaro E, Bryan AD. Comparing theory-based condom interventions: Health belief model vs. theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology. 2014;33:1251–1260. doi: 10.1037/a0033969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldstein Ewing SW, Ryman SR, Gillman A, Weiland BJ, Thayer RE, Bryan AD. Developmental cognitive neuroscience of adolescent sexual risk and alcohol use. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1155-2. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wildsmith E, Manlove J, Steward-Streng N. Relationship Characteristics and Contraceptive Use Among Dating and Cohabiting Young Adult Couples. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015 doi: 10.1363/47e2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter HJ, Vaughan RD, Ragin DF, Cohall AT, Kasen S. Prevalence and correlates of AIDS-related behavioral intentions among urban minority high school students. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6:339–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misovich SJ, Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: Evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Review of General Psychology. 1997;1:72–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Aguiar A, Camargo BV. Romantic relationships, adolescence and HIV: Love as an element of vulnerability. Paideia. 2014;24:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hock-Long L, Henry-Moss D, Carter M, et al. Condom use with serious and casual heterosexual partners: Findings from a community venue-based survey of young adults. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:900–913. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broaddus MR, Schmiege SJ, Bryan AD. An expanded model of the temporal stability of condom use intentions: Gender-specific predictors among high-risk adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;42:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9266-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glor JE, Severy LJ. Frequency of intercourse and contraceptive choice. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1990;22:231–237. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000018563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tucker JS, Ober A, Ryan G, Golinelli D, Ewing BA, Wenzel SL. To use or not to use: A stage-based approach to understanding condom use among homeless youth. AIDS Care. 2014;26:567–573. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.841834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callahan TJ, Montanaro E, Magnan RE, Bryan AD. Project MARS: Design of a Multi-Behavior Intervention Trial for Justice-Involved Youth. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3:122–130. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Workowski KA, Berman S Prevention CfDCa. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep 2010. 2010;59:1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray CC, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Kraft JM, et al. In their own words: Romantic relationships and the sexual health of young African American women. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:33–42. doi: 10.1177/00333549131282S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wulfert E, Biglan A. A contextual approach to research on AIDS prevention. The Behavior Analyst. 1994;17:353–363. doi: 10.1007/BF03392681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marhefka SL, Valentin CR, Pinto RM, Demetriou N, Wiznia A, Mellins CA. "I feel like I'm carrying a weapon" Information and motivations related to sexual risk among girls with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1321–1328. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.532536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson HW, Donenberg G. Quality of parent communication about sex and its relationship to risky sexual behavior among youth in psychiatric care: a pilot study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:387–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon S. Teenage sex is a health hazard. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 1985;1:283–291. doi: 10.1515/IJAMH.1985.1.3-4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forehand R, Armistead L, Long N, et al. Efficacy of a parent-based sexual-risk prevention program for African American preadolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Widman L, Noar SM, Choukas-Bradley S, Francis DB. Adolescent sexual health communication and condom use: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology. 2014;33:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/hea0000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milhausen RR, McKay A, Graham CA, Crosby RA, Yarber WL, Sanders SA. Prevalence and predictors of condom use in a national sample of Canadian university students. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2013;22:142–151. [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, et al. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manlove J, Welti K, Wildsmith E, Barry M. Relationship types and contraceptive use within young adult dating relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46:41–50. doi: 10.1363/46e0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Young females' sexual self-efficacy: Associations with personal autonomy and the couple relationship. Sex Health. 2013;10:204–210. doi: 10.1071/SH12139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broaddus MR, Morris H, Bryan AD. 'It's Not What You Said, It's How You Said It': Perceptions of condom proposers by gender and strategy. Sex Roles. 2010;62:603–614. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9728-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lightfoot M. HIV prevention for adolescents: Where do we go from here? American Psychologist. 2012;67:661–671. doi: 10.1037/a0029831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]