Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the leading causes of death in children worldwide. Emerging evidence suggests that alterations in mitochondrial function are critical components of secondary injury cascade initiated by TBI that propogates neurodegeneration and limits neuroregeneration. Unfortunately, there is very little known about the cerebral mitochondrial bioenergetic response from the immature brain triggered by traumatic biomechanical forces. Therefore, the objective of this study was to perform a detailed evaluation of mitochondrial bioenergetics using high-resolution respirometry in a high-fidelity large animal model of focal controlled cortical impact injury (CCI) 24 h post-injury. This novel approach is directed at analyzing dysfunction in electron transport, ADP phosphorylation and leak respiration to provide insight into potential mechanisms and possible interventions for mitochondrial dysfunction in the immature brain in focal TBI by delineating targets within the electron transport system (ETS). Development and application of these methodologies have several advantages, and adds to the interpretation of previously reported techniques, by having the added benefit that any toxins or neurometabolites present in the ex-vivo samples are not removed during the mitochondrial is olation process, and simulates the in situ tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle by maximizing key substrates for convergent flow of electrons through both complexes I and II. To investigate alterations in mitochondrial function after CCI, ipsilateral tissue near the focal impact site and tissue from the corresponding contralateral side were examined. Respiration per mg of tissue was also related to citrate synthase activity (CS) and calculated flux control ratios (FCR), as an attempt to control for variability in mitochondrial content. Our biochemical analysis of complex interdependent pathways of electron flow through the electron transport system, by most measures, reveals a bilateral decrease in complex I-driven respiration and an increase in complex II-driven respiration 24 h after focal TBI. These alterations in convergent electron flow though both complex I and II-driven respiration resulted in significantly lower maximal coupled and uncoupled respiration in the ipsilateral tissue compared to the contralateral side, for all measures. Surprisingly, increases in complex II and complex IV activities were most pronounced in the contralateral side of the brain from the focal injury, and where oxidative phosphorylation was increased significantly compared to sham values. We conclude that 24 h after focal TBI in the immature brain, there are significant alterations in cerebral mitochondrial bioenergetics, with pronounced increases in complex II and complex IV respiration in the contralateral hemisphere. These alterations in mitochondrial bioenergetics present multiple targets for therapeutic intervention to limit secondary brain injury and support recovery.

Keywords: Pediatric traumatic brain injury, Mitochondria, Axonal injury, Bioenergetics, Contusion, Swine

1. Introduction

Estimates predict that traumatic brain injury (TBI) will become the third leading cause of death and disability in the world by 2020 (Gean and Fischbein, 2010). In the United States the Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates nearly 500,000 emergency department visits annually for TBI in children aged 0–14 years (Faul et al., 2010). In addition, children under the age of four have the highest rate of TBI-related emergency department visits, with over 1200 per 100,000 children (Langlois et al., 2005). These staggering numbers contribute to a child-hood mortality rate of approximately 33 per 100,000 children in the United States, making TBI a leading cause of death in children (Coronado et al., 2011).

TBI is a heterogeneous insult to the brain induced by traumatic biomechanical forces. TBI precipitates a complex, secondary pathophysiological process which can result in a cascade of deleterious side effects often far from the site of the initial injury, and which places tissue that survives the initial insult at risk for functional failure, neurodegeneration, apoptosis, and death (Hattori et al., 2003; Marcoux et al., 2008b; Ragan et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2010). A growing body of literature suggests that a main component of this secondary injury cascade is altered mitochondrial bioenergetics and cerebral metabolic crisis (Gilmer et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2006). Mitochondria play a pivotal role in cerebral metabolism and regulation of oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and apoptosis (Balan et al., 2013; Gilmer et al., 2009; Lifshitz et al., 2003; Robertson, 2004). Cerebral metabolic crisis displays regional heterogeneity, varies temporally post-injury and with gradation of injury severity, and is often sustained for a prolonged period of time (Lifshitz et al., 2003; Marcoux et al., 2008b; Ragan et al., 2013; Robertson et al., 2006, 2009; Saito et al., 2005). Unfortunately, despite evidence that such processes may vary significantly with maturation, response to cerebral metabolic and mitochondrial alterations following TBI in the immature brain is not well defined (Kilbaugh et al., 2011). Adult TBI data is difficult to extrapolate to pediatric models because critical mitochondrial characteristics are very different between young and adult animals. Differences include the number and density of complexes of the electron transfer chain, antioxidant enzyme activity and content, and lipid content (Bates et al., 1994; Del Maestro and McDonald, 1987). The immature brain’s response to each type of TBI appears to change rapidly during development from infancy through adolescence (Armstead and Kurth, 1994; Duhaime et al., 2000b; Durham and Duhaime, 2007; Raghupathi and Margulies, 2002). These unique features of the developing brain make it imperative to understand the mechanisms associated with bioenergetic failure and cell death cascades following TBI in the immature brain in order to develop age-specific and injury-specific mitochondrial-directed neuroprotective and neuro-resuscitative approaches.

Previously we reported differences in the regional mitochondrial responses in infant rodent focal injury (Kilbaugh et al., 2011). Here we investigate the regional mitochondrial functional responses of a porcine model of focal cortical impact TBI in toddler-aged animals. We determined mitochondrial bioenergetics in tissue from peri-contusional and contralateral region to focal injury, by performing in-depth assessments of respiratory capacity of electron transport system (ETS) complexes utilizing high-resolution respirometry (HRR) in ex-vivo tissue homogenates obtained 24 h post-injury to analyze and pursue mechanistic insight of the bioenergetic response to TBI.

2. Materials and methods

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania. Female, 4-week-old piglets (8–10 kg), which have comparable neurodevelopment to a human toddler, were used for the study (Armstead, 2005; Duhaime, 2006). Females were chosen to limit heterogeneity between genders based on prior work (Missios et al., 2009). Sixteen piglets were designated into a injury cohort and corresponding sham group: controlled cortical impact (CCI) at the rostal gyrus (n = 10 injured-CCI, n = 6 naïve shams-CCI). Injured animals were sacrificed 24 h after CCI.

2.1. Animal preparation

Piglets were premedicated with an intramuscular injection of ketamine (20 mg/kg) and xylazine (2 mg/kg) followed by 4% inhaled isoflurane in 1.0 fraction of inspired oxygen via snout mask, until abolishment of response to a reflexive pinch stimulus. Endotracheal intubation was followed by a decrease in fraction of inspired oxygen to 0.21 and maintenance of anesthesia with 1% inhaled isoflurane. Buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg) was delivered intramuscularly for analgesia prior to injury. Using a heating pad, core body temperature was keptconstant between 36 and 38 °C and monitored via a rectal probe. Non-invasive blood pressure, oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate, and end-tidal CO2 were continuously monitored throughout the experiment (VetCap model 2050081; SDI, Waukesha, WI). If necessary, mechanical ventilation was utilized to maintain normoxia and normocarbia before injury, otherwise piglets maintained spontaneous ventilation.

2.2. Controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury

While maintained on isoflurane, the vertex of the head was clipped and prepped with chlorhexidine solution. After infiltration of a local anesthetic (1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1/100,000), the right coronal suture was exposed, and a craniectomy performed over the rostral gyrus allowing a 1 cm margin around the indenter tip of the cortical impact device described previously (Duhaime et al., 2000a). The exposed dura was opened in a stellate fashion to reveal the cortical surface, and the device was stabilized against the skull with screws. The spring-loaded tip rapidly (4 ms) indented 0.63 cm of the cortical rostral gyrus (Duhaime et al., 2000a). The device was removed, the dura re-approximated, and the surgical flap sutured closed. After emergence from isoflurane, piglets were extubated when they met the following criteria: return of pinch reflex, spontaneously breathing and able to maintain oxygenation and ventilation, normotensive, and stable heart and respiratory rate. Following extubation, animals displayed initial depressed activity and gait instability, but apnea and hypotension were never observed after CCI. Animals were recovered and returned to the animal housing facility when they met the following criteria: vocalization without squealing, able to ambulate, devoid of aggression or avoidance behavior, absence of piloerection, and proper feeding and drinking behaviors. Animals were more hypoactive and spent more time recumbent than non-injured littermates following injury, but were able to drink and eat unassisted. These injuries are best described as mild-to-moderate in severity, based on parallels with human clinical severity classifications (Adelson et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2012).

2.3. Sample acquisition for mitochondrial assessments

At 24 h post-TBI, animals were re-anesthetized with 1% isoflurane. A bilateral craniectomy was performed to expose the brain, tissue was rapidly extracted from two locations of interest from the injury cohort and shams while simultaneously receiving a pentobarbital overdose. Locations of interest, included: a 2 cm2 region of cortex of visibly viable tissue was resected immediately adjacent to the rostral edge of the contusion, along with a mirrored corresponding 2 cm2 region from the contralateral hemisphere. Tissue was removed within seconds, and placed in ice-cold isolation buffer (320 mM sucrose, 10 mM Trizma base, and 2 mM EGTA), where the blood and blood vessels, as well as, any adherent necrotic tissue from the contused area were dissected and disposed. In addition, subcortical white matter was removed from the cortex. Following dissection tissue was placed on drying paper to absorb excess buffer and weighed. Tissue was then gently homogenized on ice in MiR05 (110 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, 3.0 mM MgCl2, 60 mM K-lactobionate, 10 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM taurine, 20 mM HEPES and 1.0 g/l fatty acid-free BSA) using a 5 ml Potter–Elvehjem teflon-glass homogenizer to a concentration of 1 mg wet weight tissue/10 μl MiR05 buffer.

2.4. Mitochondrial high-resolution respirometry (HRR)

A final concentration of tissue homogenate with MiR05 analyzed was 1 mg/ml at a constant 37 °C, and the rate of oxygen consumption was measured utilizing a high-resolution oxygraph and expressed in pmols / [s * mg of tissue homogenate], (OROBOROS, Oxygraph-2 k and DatLab software all from OROBOROS Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). All experiments were performed between 75 and 220 μM of oxygen, and re-oxygenation was performed routinely prior to addition of the complex IV electron donor described below. The oxygraph was calibrated daily, and oxygen concentration was automatically calculated from barometric pressure and MiR05 oxygen solubility factor set at 0.92 relative to pure water.

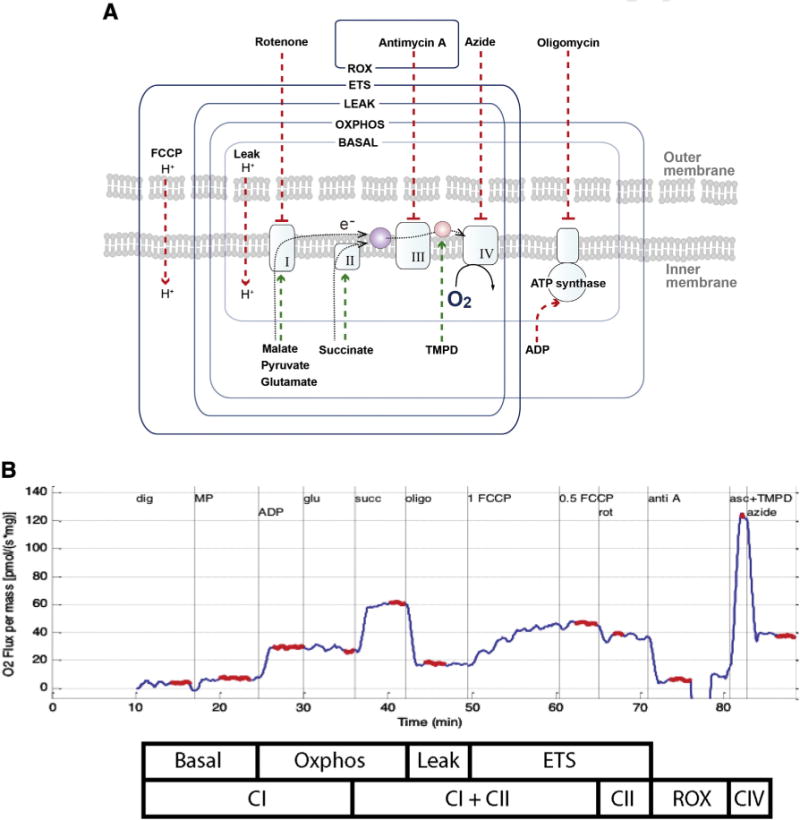

A substrate, uncoupler, inhibitor titration (SUIT) protocol previously used for rodent brain tissue (Karlsson et al., 2013) was further developed and optimized in preliminary studies in porcine brain tissue. Sequential additions were used to acquire a detailed representation of mitochondrial respiration (Figs. 1a and b). Respiratory capacities with electron flow through both complex I (CI) and complex II (CII) were evaluated separately as well as the convergent electron input through the Q-junction (CI + II) using succinate and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH)-linked substrates (Gnaiger, 2009). Plasma membranes were permeabilized with the detergent digitonin to allow non-membrane permeable substrates and ADP access to the subpopulations of mitochondria trapped within synaptosomes. Furthermore, in order to achieve similar results in brain tissue homogenates and isolated brain mitochondria, with a combination of both sub-populations, Pecinova and colleagues demonstrated that digitonin is necessary in brain homogenate preparations (Pecinova et al., 2011; Sims and Blass, 1986). Without the addition of digitonin oxidative phosphorylation capacity would likely be greatly underestimated. Thus, in preliminary experiments a careful digitonin dose titration was completed, in the presence of exogenously administered cytochrome c, which did not induce any significant effect on respiration with the digitonin dose used in the present study, indicating intact integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane (data not shown). Routine mitochondrial respiration was established by the concomitant addition of malate (5 mM) and pyruvate (5 mM), followed by ADP (1 mM) and glutamate (5 mM), to measure the oxidative phosphorylation capacity of complex I (OXPHOSCI), driven by the NADH-related substrates. Sequential addi tions followed. Succinate (10 mM) was added to stimulate maximal phosphorylating respiration capacity via convergent input through complexes I and II (OXPHOSCI + CII). Oligomycin, an inhibitor of ATP-synthase, induced mitochondrial respiration independent of ATP production across the inner mitochondrial membrane, commonly referred to as LEAK respiration (LEAKCI + CII) or State 40. Maximal convergent non-phosphorylating respiration of the electron transport system (ETSCI + CII) was evaluated by titrating the protonophore, carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) until no further increase in respiration was detected. Rotenone inhibited complex I-driven respiration and revealed complex II-driven respiration, the ETS capacity through complex II alone (ETSCII). The complex III inhibitor antimycin-A (1 μg/ml) was added to measure the residual oxygen consumption (ROX) that is independent of the ETS. Therefore, residual value measured with antimycin-A was subtracted from each of the measured respiratory states to report ETS function devoid of ROX. Antimycin-A was chosen to measure ROX, so that in this sequential protocol, complex IV activity could also be measured at the end of the protocol. Finally, complex IV activity was determined by the addition of ascorbate (ASC, 0.8 mM) and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD, 0.5 mM), an electron donor to complex IV. Due to the high level of auto-oxidation of TMPD, the complex IV-inhibitor sodium azide (10 mM) was added and the remaining chemical background was subtracted from the ascorbate/TMPD-induced oxygen consumption to assess complex IV activity. Integrated ETS analysis with internal normalization was generated using flux control ratios (FCR) calculated by dividing each respiratory state by the maximal, uncoupled mitochondrial respiration (ETSCI + CII).

Fig. 1.

Graphical representation of the substrate, uncoupler, inhibitor titration (SUIT) protocol used to study the integrated function of individual components of the electron transport system (ETS). Induced respiratory states and respiratory complexes activated are outlined by boxes: ROX, residual oxygen consumption due to non-mitochondrial respiration induced by the inhibition of the complex III by antimycin A; ETS (ETSCI + CII), respiration that is uncoupled capacity from ATP synthase induced by the optimum titration of the protonophore FCCP; LEAK (LEAKCI + CII), State 4o, is the resting non-phosphorylating electron transfer across the mitochondrial inner membrane due to uncoupling of ATP synthase by Olgiomycin; OXPHOS (OXPHOSCI + CII) coupled capacity of oxidative phosphorylation measure convergent respiration of both complex I (Malate, Pyruvate, Glutamate) and II (Succinate) substrates. The SUIT protocol employed in these experiments also utilized the complex I inhibitor, Rotenone, to measure individual complex II-driven respiration (ETSCII) separately from complex I. In addition, TMPD/ascorbate and azide were administered to measure complex IV respiration.

2.5. Citrate synthase activity

Upon completion of the HRR measurements, chamber contents were frozen for subsequent citrate synthase (CS) activity quantification. CS (μmol/mL/min) was used as a marker of brain metabolism secondary to its location within the mitochondrial matrix and importance as the first step of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). In addition, CS is used by some investigators, as a surrogate measure of mitochondrial content per mg of tissue (Bowling et al., 1993; Larsen et al., 2012). Later, samples were thawed, and a commercially available kit (Citrate Synthase Assay Kit, CS0720, Sigma) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to determine the CS activity.

2.6. Data analysis

The oxygen flux traces were analyzed with a customized Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA) program designed to extract the oxygen flux plateau at each phase of the SUIT protocol (Fig. 1b), with the exception of TMPD/ASC, when the peak oxygen flux was extracted. “Side” for focal CCI was defined as ipsilateral and contralateral to the site of injury. Statistical evaluation was performed using JMP Pro (SAS Institute Inc., version 10.0, Cary, NC, USA). We compared tissue mitochondrial respiration between injured and sham subjects with an unpaired, non-parametric Wilcoxon ranked sum test with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. A paired Wilcoxon ranked sum test was used to compare sides within sham and injury groups. Differences were considered significant where p < 0.05. All results are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. Results

3.1. Controlled cortical impact injury (CCI)

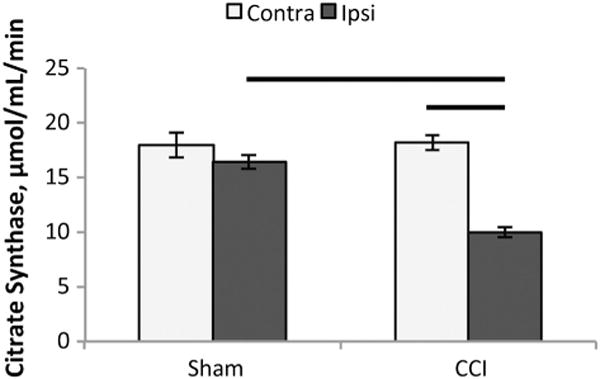

We measured CS activity per mg of tissue and found no differences between sides of the brain in the sham animals (Fig. 2). Following focal CCI injury, the ipsilateral peri-contusional side exhibited a significant reduction in CS activity, nearly 50%, compared to both ipsilateral CS activity in sham animals and contralateral tissue in injured animals.

Fig. 2.

Citrate synthase activity. Citrate synthase (CS) activity per mg of tissue 24 h after controlled cortical impact (CCI). There were no differences between sides of the brain in the sham animals, (p = 0.99). Following focal CCI injury, there was a nearly 50% reduction in CS activity in the ipsilateral peri-contusional side (9.9 ± 0.7 μmol/mL/min), compared to both the ipsilateral CS activity in sham animals, 18.2 ± 0.8 μmol/mL/min, (p < 0.001) and contralateral tissue in injured animals, 16.4 ± 0.6 μmol/mL/min, (p < 0.01). All values are mean ± SEM. Contra: contralateral side of brain, Ipsi: ipsilateral side of brain.

HRR was performed on ex-vivo tissue homogenates (pmols O2 / s * mg of tissue homogenate) in sham CCI animals to determine cerebral mitochondrial respiration. Analysis revealed no statistical difference in respiration between sides in sham animals for all measures of mitochondrial respiration (OXPHOSCI, ETSCII, OXPHOSCI + CII, ETSCI + CII, LEAKCI + CII, and complex IV) (Table 1). The overall direction of the response of individual respiratory states following CCI, reported as, per mg of tissue, FCR, and CS are depicted in Table 2.

Table 1.

Respiration of brain tissue homogenates from sham and focal controlled cortical impact TBI.

Mitochondrial respiration of brain tissue homogenates from the ipsilateral (Ipsi) and contralateral (Contra) side in two cohorts: sham and 24 h post-controlled cortical impact injury (CCI). Respiration is expressed per mg of tissue (pmols O2 / s * mg). Presented as mean ± SEM; for definitions of respiratory states and substrates utilized, please see Fig. 1.

| Respiratory parameters | Per mg of tissue (pmols O2 / s * mg)

|

Per CS activity (pmols O2 / s * mg * CS)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 6)

|

CCI (n = 10)

|

Sham (n = 6)

|

CCI (n = 10)

|

|||||

| Ipsi | Contra | Ipsi | Contra | Ipsi | Contra | Ipsi | Contra | |

| OXPHOSCI | 30.2 ± 1.8 | 28.8 ± 2.8 | 13.3 ± 1.8* | 20.6 ± 1.8*,# | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| ETSCII | 18.6 ± 0.7 | 18.3 ± 1.4 | 17.8 ± 2.1 | 36.8 ± 3.5*,# | 1.0 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.2* | 2.2 ± 0.2* |

| OXPHOSCI + CII | 47.9 ± 2.7 | 46.3 ± 3.7 | 31.6 ± 3.9* | 69.8 ± 5.7*,# | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3*,# |

| ETSCI + CII | 31.2 ± 1.5 | 30.6 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 2.9* | 49.5 ± 3.9*,# | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.3*,# |

| Complex IV | 52.9 ± 4.3 | 59.2 ± 3.9 | 51.1 ± 4.5 | 95.4 ± 9.3*,# | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.1* | 5.8 ± 0.7* |

| LEAKCI + CII | 12.4 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 0.8 | 7.1 ± 0.6* | 13.8 ± 0.9# | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.73 ± 0.02 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.84 ± 0.05*,# |

p < 0.05 significant difference from corresponding sham side.

p < 0.05 significant difference from paired injured side.

Table 2.

Summary of electron transport system response to injury.

Summary of significant electron transport system (ETS) respiratory response to CCI per mg of tissue, FCR, and normalized CS compared to corresponding sham and injured sides of brain. Irrespective of normalization methods there are patterns of mitochondrial ETS response to injury. Ipsi = ipsilateral; Contra = contralateral CCI: controlled cortical impact.

| CCI Ipsi vs. Sham Ipsi | CCI Contra vs. Sham Contra | CCI Ipsi vs. CCI Contra | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OXPHOSCI | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| FCR | ↓ | ↓ | ←→ | |

| CS | ←→ | ←→ | ←→ | |

| ETSCII | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ←→ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| FCR | ↑ | ↑ | ←→ | |

| CS | ↑ | ↑ | ←→ | |

| OXPHOSCI + CII | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| FCR | ↓ | ←→ | ↓ | |

| CS | ←→ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| ETSCI + CII | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| FCR | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| CS | ←→ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| Complex IV | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ←→ | ↑ | ↓ | |

| FCR | ←→ | ←→ | ←→ | |

| CS | ↑ | ↑ | ←→ | |

| LEAKCI + CII | ||||

| Per mg tissue | ←→ | ←→ | ↓ | |

| FCR | ↓ | ↓ | ←→ | |

| CS | ←→ | ↑ | ↓ |

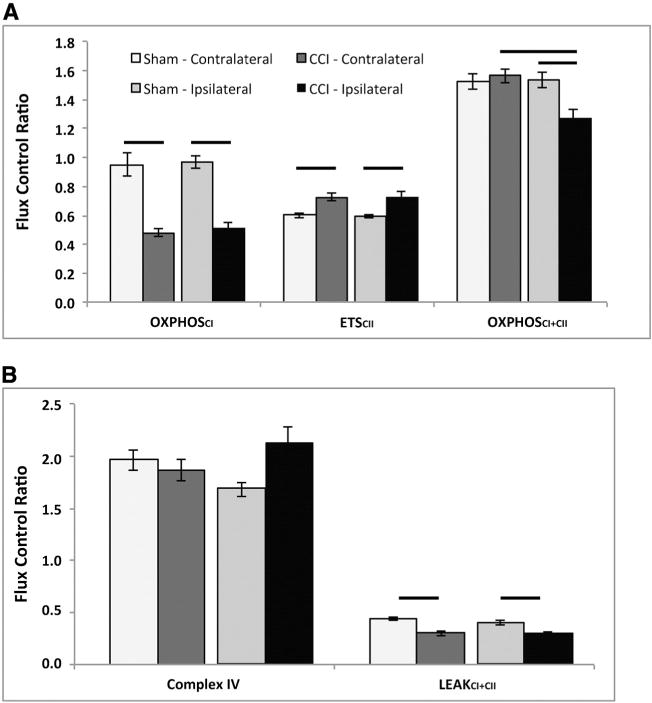

After CCI, complex I-driven respiration (OXPHOSCI) was significantly decreased bilaterally per mg of tissue when compared to corresponding shams (Table 1). These reductions for OXPHOSCI remained significant when compared to maximal ETS capacity: FCR (Fig. 3A). When compared to CS (pmols O2 / s * mg * CS), there was still a statistical trend for a decrease in OXPHOSCI respiration in ipsilateral tissue (p < 0.09); however, when compared to sham the contralateral side following CCI displayed no difference (p = 0.55) (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Mitochondrial flux control ratios from CCI injured and shams normalized by electron transport system (ETS) capacity (ETSCI + CII) measured 24 h post TBI. Sham contralateral (Contra) and ipsilateral (Ipsi) sides were not significantly different for any measure. A) Controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury resulted in a significant decrease in the contribution of complex I respiration (OXHPHOSCI) to maximal electron transport (ETSCI + CII), in injured tissue bilaterally, compared to corresponding sham regions. Complex II-driven respiration (ETSCII) was significantly increased in injured tissue bilaterally, compared to corresponding sham regions. Maximal coupled, phosphorylating respiration (OXPHOSCI + CII), stimulated by both complex I and complex II substrates, was significantly decreased post-CCI in the injured ipsilateral tissue compared to injured contralateral tissue and compared to ipsilateral sham. B) There was no significant alteration in CIV driven respiration post-CCI compared to corresponding sham in either side. State 4o (LEAKCI + CII) was significantly reduced in the ipsilateral and contralateral brain post-CCI compared to corresponding sham. Presented as mean ± SEM. For definitions of respiratory states and substrates utilized please see Fig. 1. Bars, p < 0.05. CCI: controlled cortical impact.

In contrast to complex I-driven respiration, complex II-driven respiration (ETSCII) per mg of tissue in the ipsilateral side was maintained at sham levels 24 h post-CCI, while the contralateral brain post-CCI was significantly increased compared to sham (p < 0.02) and the ipsilateral brain after injury (p < 0.03) (Table 1). ETSCII FCR was significantly increased in both sides of the injured brain compared to corresponding shams (Fig. 3A). This bilateral increase in ETSCII respiration remained significant when respiration was normalized to CS (Table 1).

Maximal coupled, phosphorylating respiration (OXPHOSCI + CII) per mg of tissue, was significantly decreased (p < 0.01) on the ipsilateral side after injury compared to sham (p < 0.04) and the contralateral injured brain (p < 0.02) (Table 1). However, in the contralateral brain following injury, OXPHOSCI + CII per mg of tissue was significantly increased compared to sham (p < 0.01). Similar to respiration per mg of tissue, OXPHOSCI + CII FCR remained significantly decreased in the ipsilateral brain after injury compared to sham and the contralateral injured brain (Fig. 3A). OXPHOSCI + CII normalized to CS on the contralateral side post-CCI was significantly increased compared to sham animals (p < 0.03) and the ipsilateral brain post-CCI (p < 0.05), similar to respiration reported per mg of tissue (Table 1).

Maximal uncoupled, non-phosphorylating respiration (ETSCI + CII), initiated by the protonophore FCCP following ATP synthase inhibition with oligomycin, also decreased on the ipsilateral side after CCI, and increased on the contralateral side compared to sham animals when reported per mg of tissue; as well as, when reported per CS (Table 1).

When complex IV respiration (isolated respiration of complex IV stimulated by the addition of the artificial electron donor TMPD) was analyzed per mg of tissue, the contralateral brain was altered; increased compared to both sham (p < 0.01) and the ipsilateral injured brain (p < 0.01), whereas the ipsilateral was not changed compared to sham (Table 1). Complex IV FCR was not altered post-CCI (Fig. 3B). Complex IV respiration normalized to CS was significantly increased bilaterally after CCI compared to sham (Table 1).

LEAK (LEAKCI + CII), or State 4o respiration, per mg of tissue was significantly decreased in the ipsilateral brain compared to sham and the contralateral injured brain (Table 1). Similarly, LEAKCI + CII FCR displayed a significant decrease in the ipsilateral brain compared to corresponding sham (Fig. 3B). LEAKCI + CII per mg of tissue in the contralateral brain post-CCI was significantly decreased compared to sham. When normalizing LEAKCI + CII to CS, only the contralateral brain post-CCI was altered; increasing compared to sham (p < 0.05) and the injured ipsilateral side (p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Respiratory ratios for evaluating phosphorylation coupling efficiency and the relative contributions of CI and CII to maximal respiration were calculated for sham and CCI animals (Table 3). Post-CCI contralateral OXPHOSCI + CII/LEAK respiration was significantly increased (p < 0.03) compared to sham animals and the ipsilateral brain post-CCI (p < 0.05) (Table 3). On the ipsilateral side of the brain there was no statistical change in OXPHOSCI + CII/LEAK after CCI compared to shams. The complex I contribution to convergent respiration of complexes I and II within the ETS post-CCI (ETSCI/ETSCI + CII) decreased bilaterally after CCI compared to sham (contralateral; p < 0.02 and ipsilateral; p < 0.004), with a corresponding increase in the complex II (ETSCII/ETSCI + CII) contribution, consistent with greater reliance on complex II after CCI in both ipsilateral and contralateral regions post-CCI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respiratory ratios of brain tissue homogenates from sham and focal controlled cortical impact TBI.

| Respiratory ratios | Sham (n = 6)

|

CCI (n = 10)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipsi | Contra | Ipsi | Contra | |

| OXPHOSCI + CII/LEAK | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.3*,# |

| ETSCI/ETSCI + CII | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.03* | 0.27 ± 0.02* |

| ETSCII/ETSCI + CII | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.03* | 0.73 ± 0.03* |

| ETSCII/ETSCI | 1.49 ± 0.09 | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 4.04 ± 1.0* | 2.94 ± 0.25* |

Respiration ratios were calculated. ETSCI was calculated by subtracting ETSCII from ETSCI + CII. Presented as mean ± SEM; for definitions of respiratory states and substrates utilized please see Fig. 1. Ipsi = Ipsilateral; Contra = Contralateral CCI: controlled cortical impact.

p < 0.05 significant different from corresponding sham side.

p < 0.05 significant different from paired injured side.

4. Discussion

4.1. High-resolution respirometry

Here we report the development and application of methodologies that may have several advantages over previously reported techniques to investigate mitochondrial function in the immature brain following injury (Kilbaugh et al., 2011). In this research, we used a more sensitive oxygraph, measuring pmol (10−12) changes in oxygen (Oxygraph-2 k, OROBOROS, Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria), which enabled analysis of more subtle changes in mitochondrial function. In addition, we utilized whole tissue homogenates for analysis of mitochondrial bioenergetics instead of using differential centrifugation to isolate mitochondrial populations. This technique adds to the analysis of isolated mitochondria by improving ex-vivo mitochondrial health, since isolation techniques may remove greater than 60% of the total mitochondrial population compared to brain tissue homogenates, and may disrupt mitochondrial structure and function to a greater extent than permeabilization/homogenization of whole tissue (Pecinova et al., 2011; Picard et al., 2011a,b). Whole tissue homogenates also carry the added benefit that any toxins or neurometabolites present in the ex-vivo samples are not removed during the mitochondrial isolation process. Beyond the use of a more sensitive instrument and tissue homogenates, our analysis extends conventional bioenergetic protocols that utilize only complex I NADH linked substrates (pyruvate + malate + glutamate) with the addition of the complex II substrate, succinate (pyruvate + malate + glutamate + succinate). This addition maximizes oxidative phosphorylation capacity (ATP production) by simulating the in situ tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and maximizing key substrates for convergent flow of electrons through complexes I and II (Gnaiger, 2009; Karlsson et al., 2013). This novel approach is directed at analyzing dysfunction in electron transport, ADP phosphorylation and leak respiration across the inner membrane (State 4O) to provide insight into potential mechanisms and possible interventions for mitochondrial dysfunction in the immature brain in focal TBI by delineating targets within the ETS. In order to reach subpopulations of mitochondria within the synaptosome, we utilized digitonin after in our experimental protocol only after careful dose–response titration studies, but we acknowledge that it may have effect overall respiration rates (Brown et al., 2004). Currently, to our knowledge, there is limited research on biomarkers of mitochondrial content (CS activity, cardiolipin content, mitochondrial DNA content, complexes I–IV protein, and complexes I–IV) that validates these surrogates against morphologic measures following acute brain injury, such as transmission electron microscopy (Chepelev et al., 2009; Larsen et al., 2012). In order to differentiate if changes in absolute rates of respiration per amount of tissue were due to changes in global mitochondrial content and function or specific to each respiratory state, we used two strategies to normalize the values. First, we used the common approach of measuring CS activity as a mitochondrial marker of content. However, the enzyme itself may be altered following injury devoid of any alteration in mitochondrial content (Chepelev et al., 2009). In addition, flux control ratios were assessed as an internal normalization of the respiratory states to the maximal uncoupler-induced rate of respiration within the ETS, a method that may be independent of tissue heterogeneity (Aidt et al., 2013). All of these methods have strengths and weaknesses, thus we decided to present data for each respiratory state in response to injury multiple ways: tissue mass, FCR, CS activity, as well as ratios for evaluating coupling of respiration to ATP production and the relative contribution of complex I- and II-driven respiration to maximal flux. This approach revealed distinct patterns of mitochondrial respiration 24 h after TBI in the immature brain. Because response to injury severity and time course likely varies between injury, we focused our study on regional variations in response to 24 h after TBI. Future studies are planned to identify the role of injury type, injury severity, and the post-TBI time course on regional tissue responses.

Our biochemical analysis of complex interdependent pathways of electron flow through the ETS, by most measures, reveals a bilateral decrease in complex I-driven respiration and an increase in complex II-driven respiration 24 h after focal TBI. Despite significant increase in complex II activity in the ipsilateral brain following injury, convergent complex I- and complex II-driven respiration is limited in its ability to maintain or stimulate oxidative phosphorylation compared to baseline sham mitochondrial respiration. However, surprisingly, the contralateral brain primarily relying on increases in complex II activity is able to maintain maximal oxidative phosphorylation, and for most measures, is able to increase respiration at 24 h after a focal injury. These alterations present multiple targets for therapeutic intervention to limit secondary brain injury, which we present below.

Complex I-driven respiratory dysfunction is a persistent characteristic of early mitochondrial dysfunction within 6–8 h following traumatic and ischemic injury in the brain, and even in other organ systems such as the heart (Almeida et al., 1995; Gilmer et al., 2009; Kunz et al., 2000; Lemieux et al., 2011; Niatsetskaya et al., 2012; Robertson, 2004; Singh et al., 2006; Suchadolskiene et al., 2014). Previous studies in focal TBI, in both mature and immature rodents, have shown a recovery of complex I-driven respiration to sham levels by 24 h post-CCI in the ipsilateral brain, an observation that differs from those in our study (Kilbaugh et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2006). Interestingly, Pandya and colleagues, in mature rodents showed that complex I respiration was significantly decreased at both 24 and 48 h; however, this study unlike the previously mentioned, sampled the core/penumbra while the other studies sampled the whole ipsilateral cortex (Pandya et al., 2009). These differences may be predicated by a species-related difference or to techniques of analyzing mitochondrial function, due to the fact that all previous studies utilized isolated mitochondrial preparations that select for relatively uninjured mitochondria based on density. Investigating an extended time course in tissue homogenates post-CCI, a recent study measured mitochondrial respiration at two time points and showed a reduction in complex-I driven cortical respiration at 7 days, with a recovery to sham levels at 17 days (Watson et al., 2013). Interpreting these studies and our data, creates an important time course, and we speculate that complex I-driven respiration is rapidly impaired within hours in the ipsilateral brain following CCI, and may remain significantly depressed for a minimum of 7 days. We speculate that the duration of reduction in complex I respiration and timing of recovery to maintain bioenergetic output is likely critical for neuronal survival, recovery and regeneration. In fact, chronic alterations in complex I function, loss of mitochondrial bioenergetic function, and production of ROS have been implicated in exacerbating chronic inflammation and cellular destruction in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (Navarro and Boveris, 2009; Walker and Tesco, 2013). However, the inhibition of complex I-driven respiration may be a theoretical, compensatory advantage by limiting ROS generation and improving Ca2+ buffering capacity by inhibiting the reversal of electron transport flow from complex II to complex I, a major source of ROS generation from the ETS, a combined process that may be an important protective process to limit secondary pathologic cascades (Loor et al., 2011; Niatsetskaya et al., 2012). Further research is needed to determine whether attenuation or supplementation of complex I as a potential therapeutic target in TBI.

Contrasting complex I-driven respiration at 24 h, ours is the first study to show an increase in complex II-driven respiration in the immature brain following TBI at any time point. In fact, our study shows that by 24 h post-CCI, complex II-driven respiration is at least maintained, if not significantly increased in peri-contusional tissue; and, interestingly is also stimulated by focal injury in regions remote from the impact in the contralateral brain. The consequence of convergent respiration, the convergence of non-linear electron flow from both complexes I and complex II to the Q-junction, and dependence on complex II respiration post-TBI is further supported by the overall decrease in ETSCI/ETSCI + CII in both sides of the injured brain and an overall increase in ETSCII/ETSCI + CII compared to sham. Therefore, we speculate that complex II-driven respiration may be a compensatory response to maintain an increased bioenergetic output in the face of increased demand and depressed complex I respiration following CCI, at least at 24 h post-TBI. Further support for compensatory mechanisms is the increased complex IV activity. Our study suggests similar findings to a published report in neonatal mice where global cerebral complex II FAD-linked respiration takes priority over complex I NAD-linked respiration following hypoxic ischemia (Niatsetskaya et al., 2012). In contrast, other published data available suggests that complex II-driven respiration is significantly reduced in mature brain following CCI within hours of the injury and persists up to 17 days; however, in these studies alterations in the ipsilateral brain were reported as a percent of contralateral mitochondrial respiration using the contralater al side from an injured animal as an internal control (Gilmer et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2013).; which, as our data suggest, may not be a surrogate for sham respiration due to the significant increase in complex II-driven respiration in the injured contralateral side. We speculate that the differing response is due to the developmental age of the animals studied; however, it is difficult to draw final conclusions without similar control groups. Future studies will be critical to understand an age specific time course of mitochondrial alterations following CCI, and whether supplementation of complex II-driven respiration offers a ther apeutic advantage in pediatric traumatic brain injury.

As discussed, although contralateral mitochondrial respiration in the injured brain may not be comparable to shams, it may still be important to compare contralateral and ipsilateral mitochondrial bioenergetics following injury. Our results of global changes in bioenergetic function occurring in the contralateral hemisphere following focal injury in a large animal model correlates with rodent data depicting global alterations in oxidative metabolism (Scafidi et al., 2009) and neuropathology (Hall et al., 2008), as well as human imaging data utilizing positron emission tomography (Vespa et al., 2005). Compensatory increases in contralateral mitochondrial respiration post-CCI may represent an increase in mitochondrial respiration stimulated after injury that may be necessary to limit secondary cascades of TBI in face of increased metabolic demand (Marcoux et al., 2008a; Robertson et al., 2006; Wright et al., 2013). Therefore, there remains a significant difference between the contralateral and ipsilateral sides of the injured brain for maximal coupled and uncoupled oxidative phosphorylation by all measures; as well as, a significant evolving lesion volume beyond 24 h (evaluated with neuropathology and significant behavioral changes in our model; data not shown); and other limited studies in rodents (Vespa et al., 2005; Watson et al., 2013). Future research should focus on identifying and targeting mitochondrial bioenergetic demands that improve outcomes and are correlated to invasive neuromonitoring, neuroimaging, and neurobehavioral outcomes (Kilbaugh et al., 2011; Scafidi et al., 2010; Vespa et al., 2005; Watson et al., 2013). This is a critical step for the screening and development of mitochondrial-targeted therapies and the development of pre-clinical trials.

LEAK respiration, State 4o, 24 h post-CCI of the ipsilateral side displays no difference or is significantly decreased for all measures (per mg of tissue, FCR, and CS) compared to shams and the contralateral side post-CCI. Once again this differs from reported results in mature rodent models of CCI, which displayed a significant increase in State 40 respiration at 24 h in isolated mitochondria from ipsilateral tissue compared to shams (Singh et al., 2006). This increase in State 40 respiration seen at 24 h by Singh and colleagues in mature rodents is the primary determinant of a decreased respiratory control ratio (RCR: State 3/State 40; an indicator of overall phosphorylation coupling efficiency), a result we do not find in the immature brain following CCI, where RCRs are similar to sham RCRs at 24 h. The increase in LEAK, State 4o, in the contralateral brain post-CCI combined with an increase in OXPHOSCI + CII compared to sham likely represents an increase in coupled convergent respiration. However, a limitation to comparing our studies with conventional “Chance and Williams” State 3 and 4 respiration using only CI substrates, is that our study measures convergent input from complex I and complex II substrates which produces a higher proton motive force. The leak respiration (State 4o) under these circumstances may differ. This could certainly affect the RCR negatively and should be taken into account when making strict comparisons between techniques. Furthermore, FCCP titration before the addition of oligomycin (OXHPOS state) would likely result in higher maximal respiration but it would also prevent the possibility of measuring LEAK respiration in the same protocol. The findings demonstrate that ATP-synthase/complex V activity is not rate limiting in immature swine brain homogenate because the FCCP-induced respiration was not higher than OXPHOS. The relative difference between the treatment groups should however not be influenced since the protocol was identical. In addition, with these pilot studies in large animals it is possible that techniques for harvesting and measuring respiration will improve over time, as will coupled respiration, and we will certainly report this in the future.

Finally, the profound reduction of citrate synthase activity within the ipsilateral tissue post-CCI, by nearly 50%, is a critical finding since CS is generally assumed to be the rate-limiting enzyme of the TCA cycle and possibly a biomarker of mitochondrial content. We speculate that decreased CS activity in the ipsilateral tissue may be associated with significant oxidative injury in the at risk peri-contusional tissue following focal impact, reflecting oxidative inactivation of CS, and/or a loss of mitochondrial content (Chepelev et al., 2009). If CS is associated with mitochondrial content, this is a staggering loss of functional mitochondria following CCI in the ipsilateral tissue. We speculate that macroautophagy or, more specifically, mitophagy may play a role in the loss of mitochondrial content seen at 24 h post-CCI, given the paucity of evidence of necrosis and cellular loss at this time point on neuropathology in this peri-contusional region (Duhaime et al., 2003; Grate et al., 2003; Weeks et al., 2014). Our findings at 24 h post-CCI are consistent with findings in cortical tissue homogenates harvested from the peri-contusional regions in adult rodents depicting significantly decreased CS activity at 7 days post-TBI. Thus, by combining our results with those previously published, we begin to delineate a time course of rapid oxidative injury and/or decreased mitochondrial content, with a rapid loss within 24 h and persisting for at least 7 days. Therefore, we propose that interventions should be instituted early to limit the reduction of CS in tissue with potential viability and increased bioenergetic demand (Watson et al., 2013).

5. Conclusion

We have evaluated the mitochondrial bioenergetic response to TBI in a unique large animal translational platform of focal impact injury and conclude that there are significant alterations in mitochondrial respiration in the immature brain 24 h after TBI that vary by location from focal injury. Alterations in complex I- and complex II-driven respiration following injury identify opportunities for therapeutic interventions in the immature brain to limit secondary injury and support post-traumatic bioenergetic demand by substrate-directed resuscitation. Finally, this translational model expands our knowledge of evolving mitochondrial techniques as well as the bioenergetic response to a spectrum of TBI pathology in the immature brain; importantly, these techniques and findings will continue to inform advanced pre-clinical trials in pediatric TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Albana Shahini and Saori Morota for their invaluable technical support. The Oroboros Oxygraph used in the study was a loan from NeuroVive Pharmaceutical AB, Lund Sweden. Studies were supported by the NIH UO1 NS069545, Endowed Chair of Critical Care Medicine at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and Stephenson Fund Department of Bioengineering the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Funding information: NIH/NINDS grants: R01NS039679 and U01NS069545.

Authors disclosure statement

Eskil Elmer and Magnus J. Hansson own shares in and have received salary support from NeuroVive Pharmaceutical AB, a public company active in the field of mitochondrial medicine. Michael Karlsson has received salary support from NeuroVive Pharmaceutical AB.

Contributor Information

Michael Karlsson, Email: michael.karlsson@med.lu.se.

Melissa Byro, Email: melissa.byro@gmail.com.

Ashley Bebee, Email: ashley.n.durban@gmail.com.

Jill Ralston, Email: ralstonjm@gmail.com.

Sarah Sullivan, Email: sarahsul@seas.upenn.edu.

Ann-Christine Duhaime, Email: aduhaime@partners.org.

Magnus J. Hansson, Email: magnus.hansson@med.lu.se.

Eskil Elmer, Email: eskil.elmer@med.lu.se.

Susan S. Margulies, Email: margulie@seas.upenn.edu.

References

- Adelson PD, Pineda J, Bell MJ, Abend NS, Berger RP, Giza CC, Hotz G, Wainwright MS, Pediatric TBID, Clinical AssessmentWorking G Common data elements for pediatric traumatic brain injury: recommendations from the working group on demographics and clinical assessment. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:639–653. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidt FH, Nielsen SM, Kanters J, Pesta D, Nielsen TT, Norremolle A, Hasholt L, Christiansen M, Hagen CM. Dysfunctional mitochondrial respiration in the striatum of the Huntington’s disease transgenic R6/2 mouse model. PLoS Curr. 2013;5 doi: 10.1371/currents.hd.d8917b4862929772c5a2f2a34ef1c201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A, Brooks KJ, Sammut I, Keelan J, Davey GP, Clark JB, Bates TE. Postnatal development of the complexes of the electron transport chain in synaptic mitochondria from rat brain. Dev Neurosci. 1995;17:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000111289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead WM. Age and cerebral circulation. Pathophysiology. 2005;12:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead W, Kurth C. Different cerebral hemodynamic responses following fluid percussion brain injury in the newborn and juvenile pig. J Neurotrauma. 1994;11:487–497. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan IS, Saladino AJ, Aarabi B, Castellani RJ, Wade C, Stein DM, Eisenberg HM, Chen HH, Fiskum G. Cellular alterations in human traumatic brain injury: changes in mitochondrial morphology reflect regional levels of injury severity. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:367–381. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates TE, Almeida A, Heales SJ, Clark JB. Postnatal development of the complexes of the electron transport chain in isolated rat brain mitochondria. Dev Neurosci. 1994;16:321–327. doi: 10.1159/000112126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling AC, Mutisya EM, Walker LC, Price DL, Cork LC, Beal MF. Age-dependent impairment of mitochondrial function in primate brain. J Neurochem. 1993;60:1964–1967. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Sullivan PG, Dorenbos KA, Modafferi EA, Geddes JW, Steward O. Nitrogen disruption of synaptoneurosomes: an alternative method to isolate brain mitochondria. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepelev NL, Bennitz JD, Wright JS, Smith JC, Willmore WG. Oxidative modification of citrate synthase by peroxyl radicals and protection with novel antiox idants. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2009;24:1319–1331. doi: 10.3109/14756360902852586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronado VG, Xu L, Basavaraju SV, McGuire LC, Wald MM, Faul MD, Guzman BR, Hemphill JD, Centers for Disease, C., Prevention Surveillance for traumatic brain injury-related deaths—United States, 1997–2007. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Maestro R, McDonald W. Distribution of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase and catalase in developing rat brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 1987;41:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(87)90051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC. Large animal models of traumatic injury to the immature brain. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:380–387. doi: 10.1159/000094164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC, Margulies SS, Durham SR, O’Rourke MM, Golden JA, Marwaha S, Raghupathi R. Maturation-dependent response of the piglet brain to scaled cortical impact. J Neurosurg. 2000a;93:455–462. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC, Margulies SS, Durham SR, O’Rourke MM, Golden JA, Marwaha S, Raghupathi R. Maturation-dependent response of the piglet brain to scaled cortical impact. J Neurosurg. 2000b;93:455–462. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.3.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC, Hunter JV, Grate LL, Kim A, Golden J, Demidenko E, Harris C. Magnetic resonance imaging studies of age-dependent responses to scaled focal brain injury in the piglet. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:542–548. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham SR, Duhaime AC. Maturation-dependent response of the immature brain to experimental subdural hematoma. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:5–14. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States: Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations and Deaths 2002–2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; Atlanta (GA): 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gean AD, Fischbein NJ. Head trauma. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2010;20:527–556. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer LK, Roberts KN, Joy K, Sullivan PG, Scheff SW. Early mitochondrial dysfunction after cortical contusion injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1271–1280. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnaiger E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1837–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grate LL, Golden JA, Hoopes PJ, Hunter JV, Duhaime AC. Traumatic brain injury in piglets of different ages: techniques for lesion analysis using histology and magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;123:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00361-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ED, Bryant YD, Cho W, Sullivan PG. Evolution of post-traumatic neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in mice and rats as assessed by the de Olmos silver and fluorojade staining methods. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:235–247. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori N, Huang SC, Wu HM, Yeh E, Glenn TC, Vespa PM, McArthur D, Phelps ME, Hovda DA, Bergsneider M. Correlation of regional metabolic rates of glucose with glasgow coma scale after traumatic brain injury. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1709–1716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M, Hempel C, Sjovall F, Hansson MJ, Kurtzhals JA, Elmer E. Brain mitochondrial function in a murine model of cerebral malaria and the therapeutic effects of rhEPO. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:151–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbaugh TJ, Bhandare S, Lorom DH, Saraswati M, Robertson CL, Margulies SS. Cyclosporin A preserves mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in the immature rat and piglet. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28:763–774. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz WS, Kudin AP, Vielhaber S, Blumcke I, Zuschratter W, Schramm J, Beck H, Elger CE. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in the epileptic focus of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:766–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Thomas KE. The incidence of traumatic brain injury among children in the United States: differences by race. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:229–238. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen S, Nielsen J, Hansen CN, Nielsen LB, Wibrand F, Stride N, Schroder HD, Boushel R, Helge JW, Dela F, Hey-Mogensen M. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. J Physiol. 2012;590:3349–3360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.230185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux H, Semsroth S, Antretter H, Hofer D, Gnaiger E. Mitochondrial respiratory control and early defects of oxidative phosphorylation in the failing human heart. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1729–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz J, Friberg H, Neumar RW, Raghupathi R, Welsh FA, Janmey P, Saatman KE, Wieloch T, Grady MS, McIntosh TK. Structural and functional damage sustained by mitochondria after traumatic brain injury in the rat: evidence for differentially sensitive populations in the cortex and hippocampus. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:219–231. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000040581.43808.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loor G, Kondapalli J, Iwase H, Chandel NS, Waypa GB, Guzy RD, Vanden Hoek TL, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial oxidant stress triggers cell death in simulated ischemia–reperfusion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, McArthur DA, Miller C, Glenn TC, Villablanca P, Martin NA, Hovda DA, Alger JR, Vespa PM. Persistent metabolic crisis as measured by elevated cerebral microdialysis lactate–pyruvate ratio predicts chronic frontal lobe brain atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008a;36:2871–2877. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a4a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcoux J, McArthur DA, Miller C, Glenn TC, Villablanca P, Martin NA, Hovda DA, Alger JR, Vespa PM. Persistent metabolic crisis as measured by elevated cerebral microdialysis lactate–pyruvate ratio predicts chronic frontal lobe brain atrophy after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2008b;36:2871–2877. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318186a4a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AC, Odenkirchen J, Duhaime AC, Hicks R. Common data elements for research on traumatic brain injury: pediatric considerations. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:634–638. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missios S, Harris BT, Dodge CP, Simoni MK, Costine BA, Lee YL, Quebada PB, Hillier SC, Adams LB, Duhaime AC. Scaled cortical impact in immature swine: effect of age and gender on lesion volume. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1943–1951. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A, Boveris A. Brain mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Parkinson’s disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2009;41:517–521. doi: 10.1007/s10863-009-9250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niatsetskaya ZV, Sosunov SA, Matsiukevich D, Utkina-Sosunova IV, Ratner VI, Starkov AA, Ten VS. The oxygen free radicals originating from mitochondrial complex I contribute to oxidative brain injury following hypoxia–ischemia in neona tal mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3235–3244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6303-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya JD, Pauly JR, Sullivan PG. The optimal dosage and window of opportunity to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis following traumatic brain injury using the uncoupler FCCP. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecinova A, Drahota Z, Nuskova H, Pecina P, Houstek J. Evaluation of basic mitochondrial functions using rat tissue homogenates. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, Taivassalo T, Gouspillou G, Hepple RT. Mitochondria: isolation, structure and function. J Physiol. 2011a;589:4413–4421. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard M, Taivassalo T, Ritchie D, Wright KJ, Thomas MM, Romestaing C, Hepple RT. Mitochondrial structure and function are disrupted by standard isolation methods. PLoS One. 2011b;6:e18317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragan DK, McKinstry R, Benzinger T, Leonard JR, Pineda JA. Alterations in cerebral oxygen metabolism after traumatic brain injury in children. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:48–52. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi R, Margulies SS. Traumatic axonal injury after closed head injury in the neonatal pig. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:843–853. doi: 10.1089/08977150260190438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CL. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to cell death following traumatic brain injury in adult and immature animals. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:363–368. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041769.06954.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CL, Soane L, Siegel ZT, Fiskum G. The potential role of mitochondria in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:432–446. doi: 10.1159/000094169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CL, Scafidi S, McKenna MC, Fiskum G. Mitochondrial mechanisms of cell death and neuroprotection in pediatric ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:371–380. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Maier CM, Narasimhan P, Nishi T, Song YS, Yu F, Liu J, Lee YS, Nito C, Kamada H, Dodd RL, Hsieh LB, Hassid B, Kim EE, Gonzalez M, Chan PH. Oxidative stress and neuronal death/survival signaling in cerebral ischemia. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:105–116. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi S, O’Brien J, Hopkins I, Robertson C, Fiskum G, McKenna M. Delayed cerebral oxidative glucose metabolism after traumatic brain injury in young rats. J Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl. 1):189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi S, Racz J, Hazelton J, McKenna MC, Fiskum G. Neuroprotection by acetyl-L-carnitine after traumatic injury to the immature rat brain. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:480–487. doi: 10.1159/000323178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NR, Blass JP. Expression of classical mitochondrial respiratory responses in homogenates of rat forebrain. J Neurochem. 1986;47:496–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb04529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh IN, Sullivan PG, Deng Y, Mbye LH, Hall ED. Time course of post-traumatic mitochondrial oxidative damage and dysfunction in a mouse model of focal traumatic brain injury: implications for neuroprotective therapy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1407–1418. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchadolskiene O, Pranskunas A, Baliutyte G, Veikutis V, Dambrauskas Z, Vaitkaitis D, Borutaite V. Microcirculatory, mitochondrial, and histological changes following cerebral ischemia in swine. BMC Neurosci. 2014;15:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P, Bergsneider M, Hattori N, Wu HM, Huang SC, Martin NA, Glenn TC, McArthur DL, Hovda DA. Metabolic crisis without brain ischemia is common after traumatic brain injury: a combined microdialysis and positron emission tomography study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25:763–774. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KR, Tesco G. Molecular mechanisms of cognitive dysfunction following traumatic brain injury. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:29. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson WD, Buonora JE, Yarnell AM, Lucky JJ, D’Acchille MI, McMullen DC, Boston AG, Kuczmarski AV, Kean WS, Verma A, Grunberg NE, Cole JT. Impaired cortical mitochondrial function following TBI precedes behavioral changes. Front Neuroenerg. 2013;5:12. doi: 10.3389/fnene.2013.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks D, Sullivan S, Kilbaugh T, Smith C, Margulies SS. Influences of develop mental age on the resolution of diffuse traumatic intracranial hemorrhage and axonal injury. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31:206–214. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MJ, McArthur DL, Alger JR, Van Horn J, Irimia A, Filippou M, Glenn TC, Hovda DA, Vespa P. Early metabolic crisis-related brain atrophy and cognition in traumatic brain injury. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9231-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, McArthur DL, Alger JR, Etchepare M, Hovda DA, Glenn TC, Huang S, Dinov I, Vespa PM. Early nonischemic oxidative metabolic dysfunction leads to chronic brain atrophy in traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:883–894. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]