Abstract

Intrinsically disordered proteins participate in many important cellular regulatory processes. The absence of a well-defined structure in the free state of a disordered domain, and even on occasion when it is bound to physiological partners, is fundamental to its function. Disordered domains are frequently the location of multiple sites for post-translational modification, the key element of metabolic control in the cell. When a disordered domain folds upon binding to a partner, the resulting complex buries a far greater surface area than in an interaction of comparably-sized folded proteins, thus maximizing specificity at modest protein size. Disorder also maintains accessibility of sites for post-translational modification. Because of their inherent plasticity, disordered domains frequently adopt entirely different structures when bound to different partners, increasing the repertoire of available interactions without the necessity for expression of many different proteins. This feature also adds to the faithfulness of cellular regulation, as the availability of a given disordered domain depends on competition between various partners relevant to different cellular processes.

Keywords: Coupled folding and binding, post-translational modification, transcriptional activation

Introduction

It has been two decades since the first descriptions [1, 2] of the functional importance of protein disorder [3–5], and in that time a vast new research area has developed to elucidate the complex mechanisms by which the enigmatic disordered proteins perform their cellular roles. Early work in the field coincided with significant advances in bioinformatics and genome sequencing, revealing the prevalence of disorder in the eukaryotic proteome. Notably, nearly half of the eukaryotic proteome was found to contain regions of 40 or more amino acid residues predicted to be disordered under physiological conditions [3], and a substantial proportion of these proteins containing disordered regions are involved in cellular regulation and signaling processes [6].

Disordered sequences are generally characterized by low sequence complexity and biased amino acid composition. Bulky hydrophobic amino acids are typically present in low abundance, while charged and hydrophilic amino acids are often overrepresented in disordered segments [7]. Intrinsically disordered protein (IDPs) can be entirely disordered polypeptides, or they can contain a combination of disordered regions (IDRs) and structured domains [8], with the latter being a common characteristic of eukaryotic proteins.

The physical features of IDPs make them well suited for regulatory and signaling processes [9, 10]. In isolation, IDPs do not adopt well-formed, stable globular structures and instead dynamically sample a range of conformational states. These states can vary from fully extended polypeptide chains to collapsed globules. In their unbound states, IDPs are highly flexible, allowing for extensive conformational sampling. The inherent flexibility of IDPs allows for a degree of promiscuity in interactions with cellular partners—when an IDP is in its free state, it is available for interaction with a wide array of macromolecular targets [10]. The dynamic nature of most IDPs, which sample extended as well as more compact states, allows for increased availability of binding sites as well as unrestricted access to sites of post-translational modification [11].

Indeed, many IDPs have been identified as ‘molecular hubs’ inside the cell, consistent with their numerous roles in cellular processes, and much of our knowledge about IDPs comes from studies of their interactions with other proteins or nucleic acids [7, 10, 12]. Upon binding to cellular targets, many IDPs undergo a disorder-to-order transition to form well-defined structures while in complex with their targets. IDPs can bind to their molecular targets in many ways. Some IDPs bind to their targets in partially extended structures, burying large surface areas to counteract the entropic cost of the disorder-to-order transition, while others bind through localized motifs, with relatively small binding interfaces. Many IDPs contain multiple interaction motifs, and can bind to multiple cellular partners to form higher order macromolecular assemblies.

It is important to note that complexes involving IDPs are often highly dynamic and short lived, a result of the flexibility encoded by the IDP sequence itself. IDPs often participate in interactions with high specificity but low affinity (~ μM range), facilitating rapid exchange of binding sites between multiple interacting partners. Recognition of binding partners often occurs through short, linear sequence motifs [13–15], with regions of the IDP outside these motifs remaining largely disordered, leading to the formation of so-called ’fuzzy complexes’ [16, 17]. The conformational equilibria present in even the bound states of IDPs allows IDPs to be pleiotropic binding partners in the cell [18] and underlies their critical roles in regulatory processes.

In this review, we will highlight a few of the properties that make IDPs extremely well suited to their roles in cellular regulation and signaling. Specifically, we will focus on how IDPs use short, conserved sequence motifs to recognize their binding partners and facilitate binding interactions; how the dynamic properties of IDPs in both their free states and in complex enable a single IDP to interact with numerous cellular partners; and how post-translational modifications can dramatically alter the conformational ensembles and cellular behavior of IDPs. Through this lens, we will examine how IDPs use their dynamic properties to their advantage to carry out their numerous functions in the cell.

IDPs contain multiple interaction sites

Given the well-established biological significance of IDPs, it is important to obtain a better understanding of the detailed mechanisms by which IDPs recognize and bind their targets. IDPs often utilize short peptide motifs to interact with their cellular targets. These motifs can be of many forms, but the peptide motifs most commonly utilized by IDPs fall into two groups: short, linear sequence motifs, and amphipathic, disordered sequences that adopt structure upon binding [13]. Peptide motifs are also common sites for post-translational modifications, the importance of which will be discussed later in this review.

An IDP may rely on one peptide motif for binding, or it may utilize several motifs in tandem to form a stable, high affinity complex with one or more interacting partners. Bioinformatics approaches as well as mutational studies have identified a number of peptide motifs that play important roles in driving interactions between IDPs and their targets [13]. Specific recognition sequences within IDPs are often conserved between organisms and play a major role in determining the functional binding partners of an IDP.

Linear motifs

IDPs often utilize short linear sequence motifs (commonly referred to as SLiMs; also called eukaryotic linear motifs, ELMs) to form localized interactions with their molecular partners [13, 15, 19, 20]. Identification of linear motifs by bioinformatic approaches is technically difficult and much of the information about these short peptide motifs, as well as validation of their biological functions, has been obtained experimentally [20]. Nonetheless, comparisons of motifs from the literature and the online ELM database [21] reveal some interesting features that shed light on the binding mechanisms of IDPs. Most linear motifs are shorter than 10 amino acids in length, monopartite, and participate in transient interactions with low micromolar affinities [12, 15]. Multiple linear motifs can function synergistically to increase the binding affinity of an IDP and its target protein [15]. The functional importance of these linear motifs can be readily linked to their evolutionary characteristics, as many linear motifs have been identified through comparison of sequences that encode proteins with functional similarities. Due to the short length of these motifs, a single point mutation could be sufficient to disrupt molecular recognition. Thus, evolutionary conservation of short sequence motifs frequently implies functional importance [19].

An excellent example of a conserved linear motif playing an important functional role in biology can be found in the viral genome. The oncoprotein E7 from the human papilloma virus (HPV) interacts with both the TAZ2 domain of the transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 and the pocket domain of the retinoblastoma protein pRb to deregulate the cell cycle of the host organism and enable cellular transformation [22]. E7 interacts with its cellular partners via its intrinsically disordered N-terminus, which contains two conserved regions, CR1 and CR2 [23]. The CR2 region contains a conserved LxCxE motif that is shared amongst several viral oncoproteins, including the T antigen of SV40 and the adenoviral protein E1A [24]. Mutation or deletion of the LxCxE motif abolishes binding to pRb, confirming that the LxCxE motif plays a critical role in determining the oncogenic potential of these viruses [22]. In the case of E7, the LxCxE motif also participates in interactions with the TAZ2 domain of the general transcriptional coactivator CBP and its paralog p300 [23]. For cellular transformation by high risk strains of HPV, E7 must utilize the LxCxE motif to interact with both TAZ2 and pRb. To accomplish this, E7 dimerizes through a third conserved region at its C-terminus to enable simultaneous binding to TAZ2 and pRb through the LxCxE motif [23]. Dimerization of E7 allows tandem interactions with CBP/p300 and pRb, promoting acetylation of pRb by the HAT domain of CBP/p300 and disruption of cell cycle control [23].

Molecular recognition features

In addition to linear motifs, IDPs frequently feature sequences that play important roles in molecular recognition but also undergo disorder-to-order transitions upon complex formation. These elements, often called molecular recognition features (MoRFs), are prevalent in IDPs and have been shown to mediate interactions between ordered and disordered proteins involved in cellular signaling and regulation [25, 26]. Recognition elements have been identified to include all of the secondary structural elements, though recognition elements that form helices upon binding are by far the most widely described in the literature [10, 15, 25].

Like linear motifs, molecular recognition elements typically participate in moderate affinity but high specificity interactions with their molecular targets. Upon recognizing their targets, many IDPs undergo coupled folding and binding processes to adopt stable structures in complex [12]. Often, a single molecular recognition element is capable of interacting with multiple targets, and stable secondary structure is not fully formed until recognition is complete. IDPs use this conformational plasticity to their advantage, forming relatively short-lived complexes in response to various cellular stimuli.

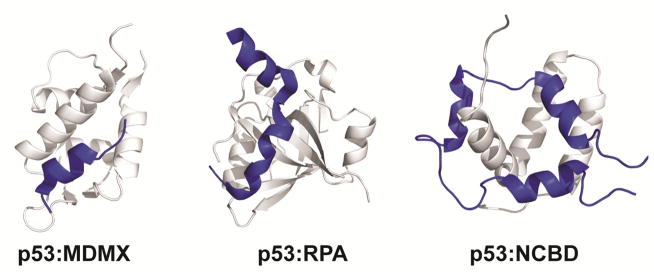

The ubiquitous tumor suppressor protein p53 utilizes two molecular recognition elements in its intrinsically disordered N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) to interact with a variety of cellular targets in response to DNA damage and cellular stress [27, 28]. Structural data exists for many complexes involving the p53 TAD, including complexes with multiple domains of the transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 [29–32], MDM2 [33] and MDMX [34], replication protein A [35], HMGB1 [36], and TFIIH [37]. The structures reveal that the p53 TAD interacts with its many targets in different conformations while utilizing similar networks of contacts involving two distinct molecular recognition elements, the amphipathic AD1 and AD2 helices (Figure 1). The AD1 helix mediates the interactions with MDM2 and MDMX [33, 34], whereas interactions via the AD2 helix are critical for binding to replication protein A, TFIIH, and HMGB1 [35–37]. The p53 TAD relies on contributions from both the AD1 and AD2 helices for interactions with the TAZ2 and NCBD domains of CBP/p300 [29, 31, 32]. The AD1 and AD2 motifs function synergistically to bind the CBP/p300 domains with high affinity [27]. The isolated AD1 and AD2 motifs differ in the strength of their interactions, with AD2 binding about 100-fold more tightly to the TAZ1 and TAZ2 domains. As a consequence, the full-length p53 TAD can act as a bridge between MDM2 and CBP/p300 to form a ternary complex in which AD1 is bound to MDM2 while AD2 interacts with the TAZ1, TAZ2, KIX, or NCBD domains of CBP/p300 [27]. This ternary complex plays an important role in regulating the stability of p53 and in mediating the response to cellular stress.

Figure 1.

Motifs play a critical role in molecular recognition by p53. Structures of the p53 transactivation domain (blue) in complex with MDMX (left), replication protein A (middle), the NCBD domain of CBP (right) are shown to illustrate how p53 uses its different interaction motifs to bind to multiple proteins.

Crosstalk between peptide motifs

While early studies on the interactions between IDPs and their globular targets generally focused on short peptides due to technical limitations [7], advances in molecular biology and biophysics have allowed investigations of interactions involving larger IDP systems containing multiple interaction sites [10]. These studies reveal that multiple recognition elements within IDPs do not function independently, despite their disordered nature. Synergistic coupling between independent binding sites is a common feature of IDPs. While individual recognition elements typically interact with low affinity, multiple tandem interaction sites often contribute to formation of high affinity complexes. For instance, the intrinsically disordered eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) binding protein 4E-BP2 binds to eIF4E to regulate cap-dependent translation initiation. Full-length constructs of 4E-BP2 bind to eIF4E via a bipartite interface to form a complex with low nanomolar affinity [38]. However, alteration of either of the two binding motifs by site-directed mutagenesis or truncation results in enhanced dynamics at the binding sites and decreased affinity, indicating that interplay between the binding sites is critical for formation of a stable complex between eIF4E and 4E-BP2 [38, 39].

Additionally, recognition elements that are spatially separated within the same polypeptide chain have been found to act by both positively and negatively cooperative mechanisms, suggesting that IDPs are capable of regulating cellular responses through allosteric modulation [40]. Theoretical descriptions of allostery suggest that disorder might even be advantageous for allosteric coupling [41] and recent examples in the literature support the roles of IDPs in modulating allostery [27, 40–46]. The adenoviral oncoprotein E1A utilizes two conserved binding motifs in its disordered N-terminus to interact with numerous cellular targets to hijack the cell cycle of the host organism and activate transcription of the viral genome [47]. E1A functions as a molecular hub and interacts with various protein partners depending on the availability of its binding sites. E1A interacts with both the TAZ2 domain of CBP/p300 and the pocket domain of the retinoblastoma protein pRb at spatially separated, non-overlapping binding sites to epigenetically reprogram the host cell [48, 49]. E1A is capable of forming binary complexes with either TAZ2 or pRb or a ternary complex with both TAZ2 and pRb, with each complex mediating a different cellular outcome [42]. Intriguingly, the order of binding events and occupancy of individual binding sites can either enhance or repress further interactions through both positive and negative cooperativity. Through this mechanism E1A is able to efficiently disrupt normal cellular regulation of the host cell and reprogram the cellular machinery for replication of the viral genome [42].

Relationship between disorder and availability of binding sites

Recent experimental and theoretical descriptions of association processes involving IDPs illustrate the extreme complexity of these processes (reviewed in [10, 50–52]). A growing body of data shows that unbound IDPs in the cell do not adopt stable structures; instead, they are best characterized as ensembles of dynamic structures that interconvert freely [53–56]. Our knowledge of the exact nature of the ‘conformational ensembles’ of IDPs and the direct correlations between conformational ensembles and biological function remains limited [54, 57, 58]. Nevertheless, the dynamic populations of IDPs within the cell are of clear importance to biological function and will undoubtedly be the focus of numerous multidisciplinary studies in the future.

The relationship between conformational ensembles of IDPs and the binding process is also of great interest from both mechanistic and functional standpoints. A better understanding of how the conformational ensemble of a free IDP affects its interactions with molecular targets will greatly enhance our understanding of how IDPs carry out their biological functions. The inherent flexibility of disordered regions helps keep binding motifs accessible until the correct target has been located. These properties give rise to complex binding mechanisms that are critical to cellular function.

Coupled folding and binding

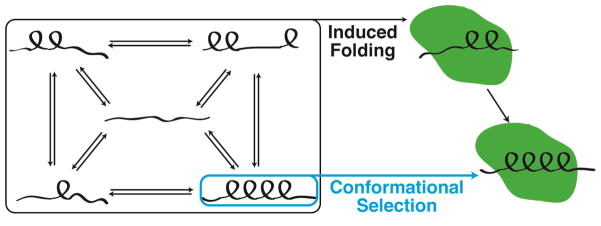

The transition from a disordered state in solution to a more ordered state upon target binding is a common feature in IDP function [5]. While a consensus mechanism for coupled folding and binding processes has yet to be established, two extreme mechanisms have been proposed and evidence has been obtained in support of each (Figure 2) [7]. At one extreme is the induced folding mechanism, which assumes that folding occurs after association of the IDP with its target. At the other extreme is the conformational selection mechanism, in which the bound conformation is populated in the conformational ensemble of the unbound IDP and is selected from the ensemble for binding to the target protein. However, the more likely scenario is that most IDPs will associate with their targets by a combination of these extreme mechanisms [59, 60].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of proposed mechanisms for coupled folding and binding processes of IDPs. The induced folding mechanism suggests that initial binding events trigger the IDP to adopt its folded conformation in complex with its target, whereas the conformational selection mechanism requires some population of the free IDP to adopt its structured conformation in the unbound state. Examples from the literature support both of the proposed mechanisms.

Role of pre-formed structure

Characterization of the conformational ensembles of IDPs reveals that free IDPs adopt varying populations of pre-formed secondary structural elements. It has been proposed that pre-formed structural elements are advantageous for target recognition, but the correlation between the populations of structural elements in the conformational ensemble of free IDPs and the behavior of IDPs in their bound states remains elusive [61, 62]. Several recent examples from the literature suggest that the population of pre-formed secondary structural elements in the conformational ensemble of free IDPs does not influence association kinetics or binding mechanism [63–67]. In each of these cases, folding of the IDP does not depend on the presence of pre-formed structure in the conformational ensemble but is instead initiated by early binding events. However, other studies clearly indicate that the population of pre-formed structural elements in the conformational ensemble directly influences binding [68–71], suggesting that the exact mechanism of coupled folding and binding differs for different IDPs.

NMR relaxation dispersion studies of coupled folding and binding processes have been particularly useful for describing the conformational transitions that occur during molecular recognition by IDPs [67, 71, 72]. A recent study on binding of the intrinsically disordered C-terminus of the Sendai virus nucleoprotein (NT) to its partially folded phosphoprotein (PX) partner demonstrates the value of the atomic level resolution provided by NMR spectroscopy when investigating complex coupled folding and binding processes. Measurements of relaxation data for multiple nuclei (15N, 1HN, and 13CO) in the disordered nucleoprotein in complex with varying sub-stoichiometric amounts of PX allowed for detailed insights into the folding process and the conformational ensemble formed early in the binding process [71]. In the case of the NT:PX interaction, partially helical conformations are present in the conformational ensemble of unbound NT, and initial interactions between these partially helical NT substates and PX directly influence formation of stable complexes [71]. Binding occurs in a two-step process by way of a disordered intermediate, which rearranges slowly to form the final folded complex [71, 73]. Interestingly, the slow step on the binding and folding pathway is associated with motions of the PX target to allow optimal docking of the NT helix [71]. It is to be hoped that relaxation dispersion studies will be performed on a wide range of IDP systems to expand our knowledge of the factors that determine the mechanism of molecular recognition.

Despite the role of pre-formed structural elements in enhancing binding or accelerating some coupled folding and binding processes [68–71], increasing the population of partially structured states in the unbound IDP does not necessarily enhance biological function. The disordered N-terminal transactivation domain of p53 relies on an amphipathic helical motif, the AD1 motif described above, to interact with the E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2. In isolation, the AD1 motif, which is flanked by conserved proline residues at both ends, has only a weak propensity to form helix. Mutation of a proline residue C-terminal to the MDM2-binding motif substantially increases both the residual helicity and the binding affinity for MDM2. However, the increased affinity of the mutant p53 has a drastic effect on transcription of target genes and on the lifetime of p53 in the cell, indicating that the intrinsic helicity of the transactivation domain of p53 is finely tuned for proper cellular function [68].

Disorder enhances the accessibility of binding sites

Another benefit of disorder is that an IDP can utilize its flexibility to adopt different conformations in complex with different cellular partners. An individual IDP can participate in early, non-specific molecular recognition events without a significant energetic penalty, thus keeping its binding motifs accessible to respond to various cellular stimuli.

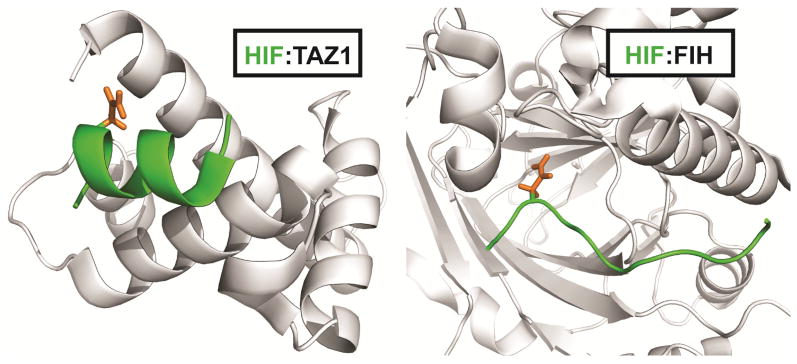

By remaining disordered in the unbound state, IDPs are able to select their targets based on environmental cues. The intrinsically disordered C-terminal transactivation domain (CTAD) of the hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) plays an important role in activating transcription of genes that are critical for cell survival under low cellular oxygen concentrations through interactions with the TAZ1 domain of the transcriptional coactivators CBP/p300 [74]. Under normoxic conditions, a single asparagine residue (Asn803) in the HIF-1α CTAD is hydroxylated by the asparagine hydroxylase FIH to impair binding to the TAZ1 domain of CBP/p300 [75, 76]. However, under hypoxic conditions, Asn803 is not hydroxylated and the HIF-1α CTAD is capable of interacting with TAZ1 with low nanomolar affinity. The HIF-1α CTAD is disordered in solution but forms three helices upon TAZ1 binding, with Asn803 located within one of these helical regions (Figure 3a) [77, 78]. Interestingly, the same region of HIF-1α adopts a markedly different conformation in complex with FIH, with the region flanking Asn803 binding to FIH in an extended structure in order to place the asparagine side chain into the FIH active site [75] (Figure 3b). In this case, HIF-1α utilizes conformational plasticity to function as a molecular switch in response to changes in oxygen levels in the cellular milieu.

Figure 3.

The HIF-1α transactivation domain can adopt multiple structures. HIF-1α binds to the TAZ1 domain of CBP in a helical conformation (left; for clarity, only one of the three helices formed in HIF-1α is shown). The same region of HIF-1α binds to FIH in an extended conformation (right). Residues 795–805 of the HIF-1α C-terminal transactivation domain are shown in green. The sidechain of asparagine 803 is highlighted in orange.

Post-translational modifications provide an exquisite level of control

A critical property of IDPs that relates to their central role in cellular signaling is their propensity for post-translational modification. There are over 300 known types of post-translational modifications (PTMs) in the eukaryotic genome [79], and studies of both IDPs and globular proteins suggest that these modifications are highly abundant, with densities potentially as high as one PTM for every 10 residues [13]. Post-translational modification sites are abundant in IDPs, and the observation that the majority of known phosphorylation sites are found in intrinsically disordered regions of eukaryotic proteins [3, 80] is not entirely surprising, as flexibility of IDPs in both their free and bound states increases their accessibility not only for molecular recognition but also to modifying enzymes.

Post-translational modification of IDPs can play a major role in modulating their cellular functions. PTMs within binding motifs can function as on/off switches for a specific molecular interaction [14]. Accumulation of multiple PTMs can dramatically alter the electrostatics of an IDP to either weaken or strengthen interactions with its cellular partners. PTMs are also capable of modulating the conformational ensembles of IDPs, both free in solution and in complex with their binding partners [10]. It is clear that post-translational modification of IDPs enables strategic, tunable, and reversible regulation of their function in the cell.

Disorder facilitates access to modifying enzymes

For a protein to be post-translationally modified, its PTM sites must be fully accessible to modifying enzymes. Potential modification sites that are obscured by structural elements are usually inaccessible to modifying enzymes and thus post-translational modifications are frequently found in disordered regions, either in the unbound IDP or in regions that remain disordered in the IDP complexes [54]. This is certainly the case for the disordered transactivation domain of HIF-1α, which necessarily adopts a relatively extended structure when bound to FIH for hydroxylation [75].

Post-translational modifications can play important roles in controlling the affinity and the order of binding events. For example, the affinity of the kinase inducible domain (KID) of the cyclic-AMP responsive transcription factor CREB for the KIX domain of CBP/p300 is enhanced 100-fold by phosphorylation at a single serine residue by protein kinase A [81, 82]. In the amino-terminal disordered transactivation domain of p53, phosphorylation of a single threonine residue (Thr18) as part of a signaling cascade impairs binding to the E3 ubiquitin ligase HDM2 [83, 84]. In both of these cases, a single phosphorylation event is sufficient for regulation of important cellular processes, highlighting the exquisite sensitivity and responsiveness of IDPs to post-translational modifications.

Accumulation of post-translational modifications can enhance cellular responses

While a single post-translational modification can be a sufficient signal in regulatory processes, PTM sites are often located in clusters within IDPs [85]. Multiple PTMs in a disordered region can act synergistically to ensure signaling fidelity in crowded cellular environments. Accumulation of PTMs in an IDP could significantly alter the charge distribution within an IDP and hence its conformational ensemble [86]. Additionally, multiple PTMs in a given region could change the electrostatic properties of the IDP to directly influence its association with cellular targets.

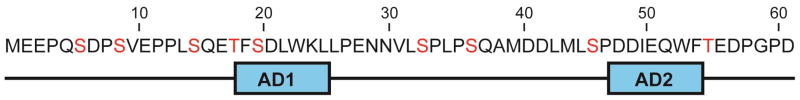

The disordered N-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) of p53 contains nine known phosphorylation sites (Figure 4). While the exact timing of phosphorylation events initiated by cellular stress is not yet known, simultaneous phosphorylation of two to four sites within the p53 TAD has been detected in cell extracts [87]. In unstressed cells, p53 forms a ternary complex with CBP/p300 and HDM2. Phosphorylation of p53 occurs in response to DNA damage, and phosphorylation of specific sites within the p53 TAD incrementally modifies the ability of p53 to interact with its cellular partners [27]. Interestingly, increasing the number of phosphorylation events on the p53 NTAD directly increases the affinity of the p53 TAD for the TAZ1, TAZ2, and KIX domains of CBP/p300, with each successive phosphorylation having an additive effect on the measured binding affinity [83]. In the case of p53, post-translational modifications play an important role in fine-tuning the binding affinity for its various cellular partners.

Figure 4.

Sequence of the amino-terminal transactivation domain of p53. Known phosphorylation sites are mapped onto the primary sequence of human p53 in red lettering. The locations of the amphipathic AD1 and AD2 binding motifs are shown below the sequence.

Modifications can induce structural changes

In addition to their ability to enhance or disrupt interactions with other proteins, post-translational modifications can also change the conformations of IDPs themselves to either favor or disfavor molecular recognition processes. Incorporation of PTMs into free IDPs can alter the distribution of states within the conformational ensemble, in effect modulating the functional capabilities of the protein.

Recent studies have demonstrated that post-translational modifications affect the conformational and structural properties of IDPs in isolation and in molecular complexes. PTMs are capable of disrupting molecular interactions and inducing distinct conformational changes [88, 89], stabilizing secondary structural elements in the conformational ensemble [90], or even inducing disorder-to-order transitions to produce partially folded conformations of IDPs in solution [91]. In its unphosphorylated state the disordered protein 4E-BP2 undergoes a disorder-to-order transition upon binding eIF4E for regulation of cap-dependent translation initiation [38, 92, 93]. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP2 at multiple sites weakens its affinity for eIF4E. The loss of affinity of the phosphorylated form of 4E-BP2 can be attributed to its structural properties in solution. Free 4E-BP2 adopts a stable, partially folded structure upon phosphorylation, effectively blocking access to one of its canonical binding motifs and thus reducing its ability to interact with eIF4E [91]. In this system, successful molecular recognition requires a sufficient amount of disorder. Stabilization of the partially folded conformation of 4E-BP2 through phosphorylation is a robust mechanism for regulating the function of 4E-BP2 in the cell.

Future Perspectives

The importance of intrinsically disordered proteins in biology and medicine cannot be understated and rapidly expanding investigations of IDPs both in vitro and in vivo continue to enhance our understanding of the important roles of IDPs in cellular regulation and signaling. It is clear that IDPs utilize a wide range of strategies to accomplish their biological tasks, with their disordered nature providing unparalleled complexity but also multiple opportunities and mechanisms for dynamic regulation of the cell, many of which have been outlined in this review.

Recent technical advances have led to new advances in understanding the diverse mechanisms of IDPs. Due to technical limitations, early studies of IDPs were often limited to experiments involving short peptides to mimic the disordered regions of larger, multi-domain proteins. Full-length eukaryotic proteins containing disordered and structured domains are often quite unstable and can be difficult to purify, even from eukaryotic systems, due to their aggregation propensities and sensitivity to proteolytic degradation. Improvements in eukaryotic expression systems [94] and screening technologies to enable rapid determination of soluble protein constructs [95] have led to significant advances in expression and purification of multi-domain disordered proteins. Cell-free expression methods also have the potential to improve the yield of intact, multi-domain proteins from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems [96, 97]. In the case of NMR spectroscopy, which requires isotopic labeling, selective labeling techniques have greatly improved our ability to characterize molecular interactions in larger systems where the combination of structured and disordered domains can be challenging. Chemical strategies for selective incorporation of NMR active isotopes at specific sites in the polypeptide allow for enhanced sensitivity and reduced spectral overlap in larger systems [98, 99]. Intein-based ligation methods promise to be extremely useful by allowing isotopic labeling of specific segments of larger polypeptides [100]. The ability to characterize the role of intrinsically disordered regions within the context of the full-length proteins will provide new insights into the relationship between local, intramolecular interactions within the conformational ensembles and the biological functions of IDPs.

Studies of IDPs in the crowded cellular environment will also be highly important. While once a source of controversy, it is now widely accepted that IDPs can exist in disordered states in the cellular context [56]. Nevertheless, many more studies and new technologies are needed to advance our understanding of how IDPs carry out their biological functions in vivo. Fluorescence-based methods have shown great promise in this regard, with single-molecule techniques providing exquisite sensitivity for detecting transient interactions and rapid signaling processes within the cell [101–103]. NMR studies of proteins in whole cells and cell extracts are in their early stages but initial proof-of-principle studies [104] suggest that these methods could be extremely useful for quantification and characterization of IDP conformational ensembles, elucidation of coupled folding and binding processes, and analysis of responses of IDPs to post-translational modifications at atomic level detail.

Due to their involvement in key signaling pathways and their frequent association with disease [6] IDPs are also becoming the focus of drug development efforts. Most of the available pharmaceuticals have been designed to target specific classes of proteins with well-defined three-dimensional structures [105, 106]. This approach to drug design is often limited by the properties of the target molecules themselves. Typically, small molecule inhibitors are designed to disrupt protein-protein interactions by binding in small, hydrophobic pockets. However, the binding interfaces that the inhibitors are intended to target often represent only a very small region within a much larger binding surface and thus are likely to be occluded by the defined structural elements of the target macromolecules, reducing the efficacy of the drug. In contrast, IDPs bind to globular proteins via discrete structural motifs linked by disordered regions. The intrinsic flexibility and specificity of the interaction between an IDP and its target proteins provides a novel approach for therapeutic design. Small molecules, as well as stapled peptides that are designed to mimic the bound conformations of IDPs have been shown to effectively target the interactions between IDPs and globular targets [107–111]. Additionally, the IDPs themselves could potentially be targeted to block specific interactions [112, 113]. Our expanding knowledge of the properties of IDPs and the mechanisms by which they function in the cell will greatly inform future drug discovery efforts.

In summary, intrinsically disordered proteins play numerous, essential roles in cellular processes. Further studies to improve our understanding of how IDPs function in the cellular context will be of extreme importance for advancing our understanding of cellular signaling and regulation. Great advances have already been made but exciting new areas of research involving IDPs are expanding our views of the structure-function paradigm and revealing that significant levels of disorder are advantageous and even required for numerous aspects of cellular function.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from grants CA096865 (P.E.W.) and GM71862 (H.J.D.) from the National Institutes of Health and from the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology (P.E.W.). R.B.B. is an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellow.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Daughdrill GW, Chadsey MS, Karlinsey JE, Hughes KT, Dahlquist FW. The C-terminal half of the anti-sigma factor, FlgM, becomes structured when bound to its target, sigma 28. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:285–91. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kriwacki RW, Hengst L, Tennant L, Reed SI, Wright PE. Structural studies of p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 in the free and Cdk2-bound state: conformational disorder mediates binding diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11504–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunker AK, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Iakoucheva LM, Obradovic Z. Intrinsic disorder and protein function. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6573–82. doi: 10.1021/bi012159+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uversky VN. Natively unfolded proteins: a point where biology waits for physics. Protein Sci. 2002;11:739–56. doi: 10.1110/ps.4210102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically unstructured proteins: re-assessing the protein structure-function paradigm. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:321–31. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:573–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Intrinsically unstructured proteins and their functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Lee R, Buljan M, Lang B, Weatheritt RJ, Daughdrill GW, Dunker AK, Fuxreiter M, Gough J, Gsponer J, Jones DT, Kim PM, Kriwacki RW, Oldfield CJ, Pappu RV, Tompa P, Uversky VN, Wright PE, Babu MM. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chemical reviews. 2014;114:6589–631. doi: 10.1021/cr400525m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gsponer J, Babu MM. The rules of disorder or why disorder rules. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology. 2009;99:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright PE, Dyson HJ. Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson TJ. Cell regulation: determined to signal discrete cooperation. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2009;34:471–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Current opinion in structural biology. 2002;12:54–60. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tompa P, Davey NE, Gibson TJ, Babu MM. A million peptide motifs for the molecular biologist. Molecular cell. 2014;55:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Roey K, Gibson TJ, Davey NE. Motif switches: decision-making in cell regulation. Current opinion in structural biology. 2012;22:378–85. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Roey K, Uyar B, Weatheritt RJ, Dinkel H, Seiler M, Budd A, Gibson TJ, Davey NE. Short linear motifs: ubiquitous and functionally diverse protein interaction modules directing cell regulation. Chemical reviews. 2014;114:6733–78. doi: 10.1021/cr400585q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mittag T, Marsh J, Grishaev A, Orlicky S, Lin H, Sicheri F, Tyers M, Forman-Kay JD. Structure/function implications in a dynamic complex of the intrinsically disordered Sic1 with the Cdc4 subunit of an SCF ubiquitin ligase. Structure. 2010;18:494–506. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tompa P, Fuxreiter M. Fuzzy complexes: polymorphism and structural disorder in protein-protein interactions. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2008;33:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tompa P, Szasz C, Buday L. Structural disorder throws new light on moonlighting. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2005;30:484–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davey NE, Van Roey K, Weatheritt RJ, Toedt G, Uyar B, Altenberg B, Budd A, Diella F, Dinkel H, Gibson TJ. Attributes of short linear motifs. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8:268–81. doi: 10.1039/c1mb05231d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neduva V, Russell RB. Linear motifs: evolutionary interaction switches. FEBS letters. 2005;579:3342–5. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould CM, Diella F, Via A, Puntervoll P, Gemund C, Chabanis-Davidson S, Michael S, Sayadi A, Bryne JC, Chica C, Seiler M, Davey NE, Haslam N, Weatheritt RJ, Budd A, Hughes T, Pas J, Rychlewski L, Trave G, Aasland R, Helmer-Citterich M, Linding R, Gibson TJ. ELM: the status of the 2010 eukaryotic linear motif resource. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:D167–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology. 2009;384:335–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansma AL, Martinez-Yamout MA, Liao R, Sun P, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. The high-risk HPV16 E7 oncoprotein mediates interaction between the transcriptional coactivator CBP and the retinoblastoma protein pRb. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:4030–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chellappan S, Kraus VB, Kroger B, Munger K, Howley PM, Phelps WC, Nevins JR. Adenovirus E1A, simian virus 40 tumor antigen, and human papillomavirus E7 protein share the capacity to disrupt the interaction between transcription factor E2F and the retinoblastoma gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:4549–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldfield CJ, Cheng Y, Cortese MS, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Coupled folding and binding with alpha-helix-forming molecular recognition elements. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12454–70. doi: 10.1021/bi050736e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohan A, Oldfield CJ, Radivojac P, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs) J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreon JC, Lee CW, Arai M, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Cooperative regulation of p53 by modulation of ternary complex formation with CBP/p300 and HDM2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6591–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811023106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teufel DP, Freund SM, Bycroft M, Fersht AR. Four domains of p300 each bind tightly to a sequence spanning both transactivation subdomains of p53. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702010104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng H, Jenkins LM, Durell SR, Hayashi R, Mazur SJ, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Miller M, Wlodawer A, Appella E, Bai Y. Structural basis for p300 Taz2-p53 TAD1 binding and modulation by phosphorylation. Structure. 2009;17:202–10. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CW, Arai M, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mapping the interactions of the p53 transactivation domain with the KIX domain of CBP. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2115–24. doi: 10.1021/bi802055v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee CW, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structure of the p53 transactivation domain in complex with the nuclear receptor coactivator binding domain of CREB binding protein. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9964–71. doi: 10.1021/bi1012996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller Jenkins LM, Feng H, Durell SR, Tagad HD, Mazur SJ, Tropea JE, Bai Y, Appella E. Characterization of the p300 Taz2-p53 TAD2 Complex and Comparison with the p300 Taz2-p53 TAD1 Complex. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2001–10. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Moreau J, Levine AJ, Pavletich NP. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science. 1996;274:948–53. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popowicz GM, Czarna A, Holak TA. Structure of the human Mdmx protein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Cell cycle. 2008;7:2441–3. doi: 10.4161/cc.6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bochkareva E, Kaustov L, Ayed A, Yi GS, Lu Y, Pineda-Lucena A, Liao JC, Okorokov AL, Milner J, Arrowsmith CH, Bochkarev A. Single-stranded DNA mimicry in the p53 transactivation domain interaction with replication protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15412–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504614102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowell JP, Simpson KL, Stott K, Watson M, Thomas JO. HMGB1-facilitated p53 DNA binding occurs via HMG-Box/p53 transactivation domain interaction, regulated by the acidic tail. Structure. 2012;20:2014–24. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Lello P, Jenkins LM, Jones TN, Nguyen BD, Hara T, Yamaguchi H, Dikeakos JD, Appella E, Legault P, Omichinski JG. Structure of the Tfb1/p53 complex: Insights into the interaction between the p62/Tfb1 subunit of TFIIH and the activation domain of p53. Molecular cell. 2006;22:731–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lukhele S, Bah A, Lin H, Sonenberg N, Forman-Kay JD. Interaction of the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E with 4E-BP2 at a dynamic bipartite interface. Structure. 2013;21:2186–96. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paku KS, Umenaga Y, Usui T, Fukuyo A, Mizuno A, In Y, Ishida T, Tomoo K. A conserved motif within the flexible C-terminus of the translational regulator 4E-BP is required for tight binding to the mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E. The Biochemical journal. 2012;441:237–45. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motlagh HN, Wrabl JO, Li J, Hilser VJ. The ensemble nature of allostery. Nature. 2014;508:331–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilser VJ, Thompson EB. Intrinsic disorder as a mechanism to optimize allosteric coupling in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8311–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700329104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferreon AC, Ferreon JC, Wright PE, Deniz AA. Modulation of allostery by protein intrinsic disorder. Nature. 2013;498:390–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia-Pino A, Balasubramanian S, Wyns L, Gazit E, De Greve H, Magnuson RD, Charlier D, van Nuland NA, Loris R. Allostery and intrinsic disorder mediate transcription regulation by conditional cooperativity. Cell. 2010;142:101–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilser VJ, Thompson EB. Structural dynamics, intrinsic disorder, and allostery in nuclear receptors as transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:39675–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.278929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Motlagh HN, Li J, Thompson EB, Hilser VJ. Interplay between allostery and intrinsic disorder in an ensemble. Biochemical Society transactions. 2012;40:975–80. doi: 10.1042/BST20120163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wrabl JO, Gu J, Liu T, Schrank TP, Whitten ST, Hilser VJ. The role of protein conformational fluctuations in allostery, function, and evolution. Biophysical chemistry. 2011;159:129–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White E. Regulation of the cell cycle and apoptosis by the oncogenes of adenovirus. Oncogene. 2001;20:7836–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferreon JC, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structural basis for subversion of cellular control mechanisms by the adenoviral E1A oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13260–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906770106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrari R, Pellegrini M, Horwitz GA, Xie W, Berk AJ, Kurdistani SK. Epigenetic reprogramming by adenovirus e1a. Science. 2008;321:1086–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1155546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dogan J, Gianni S, Jemth P. The binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP. 2014;16:6323–31. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54226b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou HX. Intrinsic disorder: signaling via highly specific but short-lived association. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2012;37:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou HX, Pang X, Lu C. Rate constants and mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins binding to structured targets. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP. 2012;14:10466–76. doi: 10.1039/c2cp41196b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Binolfi A, Theillet FX, Selenko P. Bacterial in-cell NMR of human alpha-synuclein: a disordered monomer by nature? Biochemical Society transactions. 2012;40:950–4. doi: 10.1042/BST20120096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forman-Kay JD, Mittag T. From sequence and forces to structure, function, and evolution of intrinsically disordered proteins. Structure. 2013;21:1492–9. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith AE, Zhou LZ, Pielak GJ. Hydrogen exchange of disordered proteins in Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2015;24:706–713. doi: 10.1002/pro.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Theillet FX, Binolfi A, Frembgen-Kesner T, Hingorani K, Sarkar M, Kyne C, Li C, Crowley PB, Gierasch L, Pielak GJ, Elcock AH, Gershenson A, Selenko P. Physicochemical properties of cells and their effects on intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) Chemical reviews. 2014;114:6661–714. doi: 10.1021/cr400695p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daughdrill GW, Hanely LJ, Dahlquist FW. The C-terminal half of the anti-sigma factor FlgM contains a dynamic equilibrium solution structure favoring helical conformations. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1076–82. doi: 10.1021/bi971952t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fisher CK, Stultz CM. Constructing ensembles for intrinsically disordered proteins. Current opinion in structural biology. 2011;21:426–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Espinoza-Fonseca LM. Reconciling binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;382:479–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hammes GG, Chang YC, Oas TG. Conformational selection or induced fit: a flux description of reaction mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13737–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907195106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fuxreiter M, Simon I, Friedrich P, Tompa P. Preformed structural elements feature in partner recognition by intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1015–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Yang JY, Yang MQ, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Flexible nets: disorder and induced fit in the associations of p53 and 14-3-3 with their partners. BMC genomics. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gianni S, Morrone A, Giri R, Brunori M. A folding-after-binding mechanism describes the recognition between the transactivation domain of c-Myb and the KIX domain of the CREB-binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;428:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rogers JM, Wong CT, Clarke J. Coupled folding and binding of the disordered protein PUMA does not require particular residual structure. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5197–200. doi: 10.1021/ja4125065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shammas SL, Travis AJ, Clarke J. Remarkably fast coupled folding and binding of the intrinsically disordered transactivation domain of cMyb to CBP KIX. The journal of physical chemistry B. 2013;117:13346–56. doi: 10.1021/jp404267e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shammas SL, Travis AJ, Clarke J. Allostery within a transcription coactivator is predominantly mediated through dissociation rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12055–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405815111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:1021–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borcherds W, Theillet FX, Katzer A, Finzel A, Mishall KM, Powell AT, Wu H, Manieri W, Dieterich C, Selenko P, Loewer A, Daughdrill GW. Disorder and residual helicity alter p53-Mdm2 binding affinity and signaling in cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:1000–2. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Iesmantavicius V, Dogan J, Jemth P, Teilum K, Kjaergaard M. Helical propensity in an intrinsically disordered protein accelerates ligand binding. Angewandte Chemie. 2014;53:1548–51. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Otieno S, Kriwacki R. Probing the role of nascent helicity in p27 function as a cell cycle regulator. PloS one. 2012;7:e47177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneider R, Maurin D, Communie G, Kragelj J, Hansen DF, Ruigrok RW, Jensen MR, Blackledge M. Visualizing the molecular recognition trajectory of an intrinsically disordered protein using multinuclear relaxation dispersion NMR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:1220–9. doi: 10.1021/ja511066q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sugase K, Lansing JC, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Tailoring relaxation dispersion experiments for fast-associating protein complexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13406–7. doi: 10.1021/ja0762238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dosnon M, Bonetti D, Morrone A, Erales J, di Silvio E, Longhi S, Gianni S. Demonstration of a Folding after Binding Mechanism in the Recognition between the Measles Virus NTAIL and X Domains. ACS chemical biology. 2015;10:795–802. doi: 10.1021/cb5008579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: oxygen homeostasis and disease pathophysiology. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:345–50. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Elkins JM, Hewitson KS, McNeill LA, Seibel JF, Schlemminger I, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Schofield CJ. Structure of factor-inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) reveals mechanism of oxidative modification of HIF-1 alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1802–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lando D, Peet DJ, Whelan DA, Gorman JJ, Whitelaw ML. Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science. 2002;295:858–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1068592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dames SA, Martinez-Yamout M, De Guzman RN, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Structural basis for Hif-1 alpha/CBP recognition in the cellular hypoxic response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5271–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082121399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Freedman SJ, Sun ZY, Poy F, Kung AL, Livingston DM, Wagner G, Eck MJ. Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082117899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jensen ON. Modification-specific proteomics: characterization of post-translational modifications by mass spectrometry. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O’Connor TR, Sikes JG, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic acids research. 2004;32:1037–49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature. 1993;365:855–9. doi: 10.1038/365855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Radhakrishnan I, Perez-Alvarado GC, Parker D, Dyson HJ, Montminy MR, Wright PE. Solution structure of the KIX domain of CBP bound to the transactivation domain of CREB: a model for activator:coactivator interactions. Cell. 1997;91:741–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee CW, Ferreon JC, Ferreon AC, Arai M, Wright PE. Graded enhancement of p53 binding to CREB-binding protein (CBP) by multisite phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19290–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013078107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schon O, Friedler A, Bycroft M, Freund SM, Fersht AR. Molecular mechanism of the interaction between MDM2 and p53. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:491–501. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00852-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pejaver V, Hsu WL, Xin F, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Radivojac P. The structural and functional signatures of proteins that undergo multiple events of post-translational modification. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1077–93. doi: 10.1002/pro.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Das RK, Pappu RV. Conformations of intrinsically disordered proteins are influenced by linear sequence distributions of oppositely charged residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13392–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304749110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Meek DW, Milne DM. Analysis of multisite phosphorylation of the p53 tumor-suppressor protein by tryptic phosphopeptide mapping. Methods in molecular biology. 2000;99:447–63. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-054-3:447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mitrea DM, Grace CR, Buljan M, Yun MK, Pytel NJ, Satumba J, Nourse A, Park CG, Madan Babu M, White SW, Kriwacki RW. Structural polymorphism in the N-terminal oligomerization domain of NPM1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:4466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321007111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mitrea DM, Kriwacki RW. Cryptic disorder: an order-disorder transformation regulates the function of nucleophosmin. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 2012:152–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Espinoza-Fonseca LM, Kast D, Thomas DD. Thermodynamic and structural basis of phosphorylation-induced disorder-to-order transition in the regulatory light chain of smooth muscle myosin. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12208–9. doi: 10.1021/ja803143g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bah A, Vernon RM, Siddiqui Z, Krzeminski M, Muhandiram R, Zhao C, Sonenberg N, Kay LE, Forman-Kay JD. Folding of an intrinsically disordered protein by phosphorylation as a regulatory switch. Nature. 2015;519:106–9. doi: 10.1038/nature13999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fletcher CM, McGuire AM, Gingras AC, Li H, Matsuo H, Sonenberg N, Wagner G. 4E binding proteins inhibit the translation factor eIF4E without folded structure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9–15. doi: 10.1021/bi972494r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bieniossek C, Imasaki T, Takagi Y, Berger I. MultiBac: expanding the research toolbox for multiprotein complexes. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2012;37:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yumerefendi H, Tarendeau F, Mas PJ, Hart DJ. ESPRIT: an automated, library-based method for mapping and soluble expression of protein domains from challenging targets. Journal of structural biology. 2010;172:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Katzen F, Chang G, Kudlicki W. The past, present and future of cell-free protein synthesis. Trends in biotechnology. 2005;23:150–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kurotani A, Takagi T, Toyama M, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S, Fukami Y, Tokmakov AA. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of cell-free protein synthesis: identification of multiple protein properties that correlate with successful expression. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24:1095–104. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-139527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lundstrom P, Vallurupalli P, Hansen DF, Kay LE. Isotope labeling methods for studies of excited protein states by relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. Nature protocols. 2009;4:1641–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tugarinov V, Kanelis V, Kay LE. Isotope labeling strategies for the study of high-molecular-weight proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nature protocols. 2006;1:749–54. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shah NH, Muir TW. Inteins: Nature’s Gift to Protein Chemists. Chemical science. 2014;5:446–461. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52951G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ferreon AC, Moran CR, Gambin Y, Deniz AA. Single-molecule fluorescence studies of intrinsically disordered proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2010;472:179–204. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)72010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gebhardt JC, Suter DM, Roy R, Zhao ZW, Chapman AR, Basu S, Maniatis T, Xie XS. Single-molecule imaging of transcription factor binding to DNA in live mammalian cells. Nature methods. 2013;10:421–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sakon JJ, Weninger KR. Detecting the conformation of individual proteins in live cells. Nature methods. 2010;7:203–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Selenko P, Frueh DP, Elsaesser SJ, Haas W, Gygi SP, Wagner G. In situ observation of protein phosphorylation by high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:321–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hopkins AL, Groom CR. The druggable genome. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:727–30. doi: 10.1038/nrd892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zinzalla G, Thurston DE. Targeting protein-protein interactions for therapeutic intervention: a challenge for the future. Future Med Chem. 2009;1:65–93. doi: 10.4155/fmc.09.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen L, Borcherds W, Wu S, Becker A, Schonbrunn E, Daughdrill GW, Chen J. Autoinhibition of MDMX by intramolecular p53 mimicry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420833112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lao BB, Drew K, Guarracino DA, Brewer TF, Heindel DW, Bonneau R, Arora PS. Rational design of topographical helix mimics as potent inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:7877–88. doi: 10.1021/ja502310r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lao BB, Grishagin I, Mesallati H, Brewer TF, Olenyuk BZ, Arora PS. In vivo modulation of hypoxia-inducible signaling by topographical helix mimetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:7531–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402393111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shangary S, Wang S. Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction to reactivate p53 function: a novel approach for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:223–41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yu S, Qin D, Shangary S, Chen J, Wang G, Ding K, McEachern D, Qiu S, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, Miller R, Kang S, Yang D, Wang S. Potent and orally active small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 interaction. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7970–3. doi: 10.1021/jm901400z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hammoudeh DI, Follis AV, Prochownik EV, Metallo SJ. Multiple independent binding sites for small-molecule inhibitors on the oncoprotein c-Myc. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7390–401. doi: 10.1021/ja900616b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Krishnan N, Koveal D, Miller DH, Xue B, Akshinthala SD, Kragelj J, Jensen MR, Gauss CM, Page R, Blackledge M, Muthuswamy SK, Peti W, Tonks NK. Targeting the disordered C terminus of PTP1B with an allosteric inhibitor. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:558–66. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]