Abstract

MicroRNAs are a class of small non-coding RNAs that have been implicated in regulation of a broad range of cellular and physiologic processes, including apoptosis. The objective of this study is to elucidate the roles of miR-125b in modulating ethanol-induced apoptosis in neural crest cells (NCCs) and mouse embryos. We found that treatment with ethanol resulted in a significant decrease in miR-125b expression in NCCs and in mouse embryos. We also validated that Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1 (Bak1) and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) are the direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs. In addition, over-expression of miR-125b significantly reduced ethanol-induced increase in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression, caspase-3 activation and apoptosis in NCCs, indicating that miR-125b can modulate ethanol-induced apoptosis by the regulation of Bcl-2 and p53 pathways. Furthermore, microinjection of miR-125b mimic resulted in a significant increase in miR-125b expression and a decrease in the protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA in ethanol-exposed mouse embryos. Up-regulation of miR-125b also significantly reduced ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation and diminished ethanol-induced growth retardation in mouse embryos. This is the first demonstration that miR-125b can prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis and that microinjection of miRNA mimic can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Bak1, Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, MiR-125b, Neural crest cells, P53

Introduction

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is one of the most common permanent birth defects, caused by maternal consumption of alcohol during pregnancy. Prenatal alcohol exposure results in physical, behavioral, and cognitive defects and it is considered to be the leading cause of mental retardation (Burd, 2004). While the pathogenesis of FASD is a complex, multifactorial process, apoptosis is considered to be one of the major mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of FASD (Dunty et al., 2001; Ikonomidou et al., 2000; Kotch and Sulik, 1992). Among the vulnerable cell populations are neural crest cells (NCCs), a multipotent progenitor cell population that can give rise to a diversity of neural and non-neural cell types (Hall, 2008). Studies have shown that ethanol can diminish NCCs by inducing apoptosis and that apoptosis in NCCs contributes heavily to ethanol-induced abnormalities (Cartwright and Smith, 1995; Chen and Sulik, 1996; Kotch and Sulik, 1992).

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are small noncoding regulatory RNA molecules that modulate gene expression by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of mRNA, promoting RNA degradation and inhibiting mRNA translation (Flynt and Lai, 2008). miRNAs are expressed in a wide variety of tissues and alterations in the abundance of these specific miRNAs can modulate certain miRNA-mediated transcriptional networks (Swarbrick et al., 2010), resulting in a profound impact on a wide array of biological processes, including apoptosis (Baek et al., 2008; Bartel, 2009). Studies have demonstrated that changes in miRNA expression are associated with ethanol-induced gut leakiness, tolerance, as well as neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation (Pietrzykowski et al., 2008; Sathyan et al., 2007; Tsang and Kwok, 2008). miRNAs are also involved in cell death induced by ethanol (Qi et al., 2014; Sathyan et al., 2007; Yadav et al., 2011).

miR-125b is a highly conserved miRNA that is expressed in many types of tissues, with the highest expression in the brain (Bak et al., 2008; Lagos-Quintana et al., 2002). It has been proposed that miR-125b regulates both apoptosis and proliferation (Le et al., 2011). Increase in the expression of miR-125b was observed in oligodendroglial tumors (Nelson et al., 2006). The down-regulation of miR-125b has been reported to suppress the proliferation of differentiated human neuroblastoma cells in vitro (Lee et al., 2005). Interestingly, decrease in miR-125b expression was associated with excessive apoptosis in rat embryos exposed to retinoic acid (Zhao et al., 2008). Down-regulation of miR-125b and an increased apoptosis were also observed in zebrafish embryos treated with gamma-irradiation or camptothecin (Le et al., 2009). However, the roles of miR-125b in ethanol-induced apoptosis and teratogenesis have never been investigated.

In the present study, we test the hypothesis that miR-125b modulates ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs and mouse embryos by the regulation of p53 and Bcl-2 signaling pathways and that over-expression of miR-125b can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity. For the first time, our study demonstrates that miR-125b can modulate ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs by targeting its direct targets, Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1 (Bak1) and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA). Furthermore, we demonstrate that microinjection of miRNA mimic into cultured mouse embryos can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and ethanol treatment

NCCs (JoMa1.3 cells) were cultured as previously described (Chen et al., 2013). Briefly, cells were grown on cell culture dishes coated with fibronectin and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM): Ham’s F12 (1:1) at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air. For ethanol exposure, NCCs were cultured in medium containing 50 or 100 mM ethanol for 24 hours. Stable ethanol levels were maintained by placing the cell culture plates in a plastic desiccator containing corresponding ethanol concentration in distilled water as described previously (Chen et al., 2013).

Animal care and dosing

C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were mated for two hours in the morning. The time of plug detection was considered 0 days, 0 hour of gestation (GD 0:0). Pregnant mice were given two intraperitoneal (i.p.) dose of ethanol, with 4 hours apart, in lactated Ringer’s solution at a dosage of 1.9 g/kg or 2.9 g/kg maternal body weight (BW). The first injection was administered on GD 8:0. Control mice were administered lactated Ringer’s solution alone. For miRNA analysis, pregnant mice were killed on GD 8: 6, GD 8:9 or GD 8:12 (6, 9 or 12 hours after the first ethanol treatment). Embryos were dissected free of their deciduas in lactated Ringer’s solution and then staged by counting the number of somite pairs. Embryos with comparable developmental stage were pooled for mRNA preparation. All protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell transfection

For transient transfection, miR-125b mimic, miRNA inhibitor, control mimic or control inhibitor at a final concentration of 50 nM was transfected into NCCs according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX). The cells were harvested 48 hours after transfection for additional treatments and analysis. The effects of miR-125b mimic or miR-125b inhibitor on the expression of miR-125b were verified using TaqMan® real-time PCR (Ambion, Austin, TX), as described in the next section.

Analysis of miRNA expression

To detect miRNA-125b expression, total RNA was isolated using the mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a stem-loop primer for reverse transcription followed by a sequence specific real-time Taqman® probe. Briefly, total RNA (10 ng) was reversed transcribed with 100 mM dNTPs, 50 U of reverse transcriptase, 0.4 U of RNase inhibitor, and a specific stem-loop primer at a condition of 16°C at 30 min, 42°C for 30 min, and 85°C for 5 min. qRT-PCR reactions were performed using a standard protocol on a Rotor-Gene 6000 Real-Time PCR system (Corbett Life Science, Sydney, Australia). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 min and 60 °C for 1 min. All TaqMan microRNA assays were performed in triplicate. Data were normalized with snoRNA202 as endogenous controls. Relative expression was calculated with the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method.

Construction of luciferase reporter plasmids and reporter assays

miR-125b target sites in the 3′-UTR regions of mRNAs were predicted by using the following online databases: Target Scan (http://www.targetscan.org/), microRNA (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home/do) and PicTar (http://pictar.mde-berlin.de/). The 3′-UTR of Bak1 and PUMA containing putative miR-125b binding sites were amplified from mouse genomic and cloned into the pMIR-REPORT™ (Ambion, Austin, TX). Primers used to clone the DNA fragments containing the Bak1 3′-UTR and PUMA 3′-UTR were: 5′-actagtcgtggtacacagattcttcagatc-3′ and 5′-aagcttggagagcctgatggatgtgttcag-3′; 5′-actagttccgccttctgacaccctggcca-3′ and 5′-aagcttatctacagcagtgcatgtacagt-3′, respectively. The constructs (200 ng of plasmid/well of 24-well plates) were co-transfected with 20 ng Renilla luciferase pRL-TK control reporter vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and 50 nmol of miR-125b mimics or mimic control (Ambion, Austin, TX) into NCCs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Luciferase activity was measured 48 hours after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) with a Lumat LB 9507 Ultra Sensitive Tube Luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). The luciferase activity of each sample was normalized to the pRL/TK-driven Renilla luciferase activity.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Dong et al., 2011). Briefly, NCCs were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then lysed in pre-cold RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) with 1 mM fresh-prepared PMSF (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and protease cocktail inhibitors (Roche Applied, Indianapolis, IN). Cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12,000 xg for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants were used for Western blot. The protein concentration in each sample was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Western blots were performed by standard protocols. The levels of Bak1, PUMA, caspase-3 and β-actin were analyzed with the following antibodies, respectively: rabbit polyclonal anti-Bak antibody (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-PUMA antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), rabbit monoclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-β-actin (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA). The membranes were developed on a Kodak X-OMAT 2000A imaging system (Kodak, Rochester, NY) and the intensity of the protein band was analyzed using the Adobe Photoshop CS software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Determination of cell viability and apoptosis

Cell viability was measured using an MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl) -2H-tetrazolium salt) assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Apoptosis was determined by analysis of caspase-3 activation by western blot as described previously (Dong et al., 2008).

Embryo microinjection and whole embryo culture

The delivery of miRNAs into mouse embryos requires the microinjection of miRNA mimic into the amniotic cavity of the early embryos. The microinjection technique is similar to that used for antisense oligodeoxynucleotide microinjection as previous reported by other investigators (Augustine, 1997; Augustine et al., 1993; Hartig and Hunter, 1998). On gestational day 8, C57BL/6J embryos were explanted under a dissecting microscope with removal of the maternal decidua, trophoblast, parietal yolk sac, and Reichert’s membranes, whereas the visceral yolk sac, ectoplacental cone, and amnion remained intact. Those embryos having three to five somite pairs were used for microinjection and subsequent whole embryos culture. Microinjection was performed by using a handheld microinjector made of glass pipettes which are connected by Silastic tubing to a syringe. The needle tip was inserted into the amniotic cavity by traversing the visceral yolk sac and amniotic membrane. 400 nL mixtures containing 600 nM/L miR-125b mimic, control mimic or ddH2O and 40 μg/mL Lipofectamine 2000 were microinjected into each embryo. After microinjection, each embryo was placed into a 30 ml vial for whole embryo culture as described previously (Chen et al., 2001). Embryos were cultured for 15 hours in control medium, followed by culture for an additional 9 hours in medium containing 50 mM ethanol. At the end of culture, extraembryonic membranes were removed and embryos were examined under a dissecting microscope to determine the number of somite pairs. Then the embryos were collected for preparation of miRNA and protein for the evaluation of miR-125 expression and Western blot analysis of Bak1 and PUMA expression as described above. The total protein content of each embryo was determined by using BCA protein assay kit.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). All data are expressed as means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test. Differences between groups were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

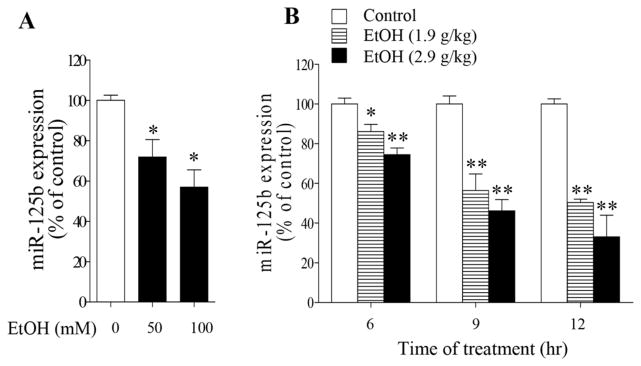

Ethanol exposure significantly decreased the expression of miR-125b in NCCs and in mouse embryos

To determine whether ethanol exposure can alter the expression of miR-125b, miR-125b expression was examined in ethanol-exposed NCCs and in mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vivo. We found that exposure of NCCs to 50 and 100 mM ethanol for 24 hours resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in miR-125b expression (Fig. 1A). Significant decrease in miR-125b expression was also observed in mouse embryos exposed to two doses of ethanol at a dosage of either 1.9 or 2.9 g/kg BW 6, 9 and 12 hours following the first dose of ethanol exposure (Fig. 1B). These results indicated that both in vitro and in vivo ethanol treatment can significantly decrease the miR-125b expression in embryonic cells or tissues.

Fig. 1.

Ethanol exposure decreased miR-125b expression in NCCs and in mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vivo. (A) Decrease in miR-125b in NCCs exposed to 50 or 100 mM ethanol for 24 hours. (B) Down-regulation of miR-125b in mouse embryos treated with ethanol at dose of 1.9 g/kg or 2.9 g/kg BW. miR-125b expression was determined by qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as percentage of control and represent the mean ± SEM of at least three separate experiments. *p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control.

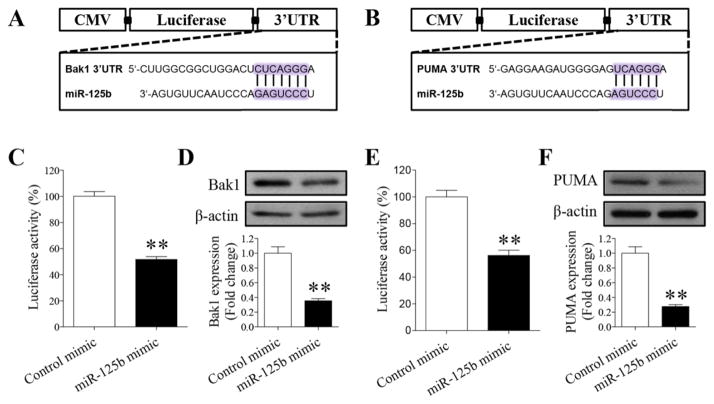

Bak1 and PUMA are direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs

MicroRNAs usually induce gene silencing by binding to target sites found within the 3′-UTR of the targeted mRNA. Using three algorithms for miRNA target prediction, miRbase, TargetScan and Pictar, we found that Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1 (Bak1) and p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) are the direct targets of miR-125b. To validate that Bak1 and PUMA are direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs, we cloned the 3′-UTR segments of Bak1 and PUMA into the 3′-UTR of a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven luciferase reporter (pMIR-report) (Fig. 2A, B). NCCs were co-transfected with vector containing pMIR reporter-luciferase fused with or without the 3′-UTR of Bak1 or PUMA mRNA and miR-125b mimic or miRNA mimic control. As shown in Figures 2C and E, co-transfection of miR-125b mimic and the 3′-UTR of Bak1 mRNA suppressed luciferase activity by 50% in comparison to a miRNA mimic control. Co-transfection of miR-125b mimic and the 3′-UTR of PUMA mRNA also resulted in a significant reduction in luciferase activity. In addition, over-expression of miR-125b in NCCs resulted in a decrease in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression (Fig. 2D, F). Together, these results demonstrated that the pro-apoptotic Bak1 and PUMA are the direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs.

Fig. 2.

Bak1 and PUMA are direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs. (A, B) The predicted binding sites of miR-125b in the 3′-UTR of Bak1 (A) and PUMA (B) mRNA are presented. (C, E) Luciferase reporter assays validated the binding of miR-125b to the 3′-UTR of Bak1 (C) or PUMA (E) in NCCs. (D, F) Western bolt analysis of the protein expression of Bak1 (D) or PUMA (F) in NCCs transfected with miR-125b mimic or control mimic for 48 hours. Data are expressed as percentage of control (C, E) or fold change over control (D, F) and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control.

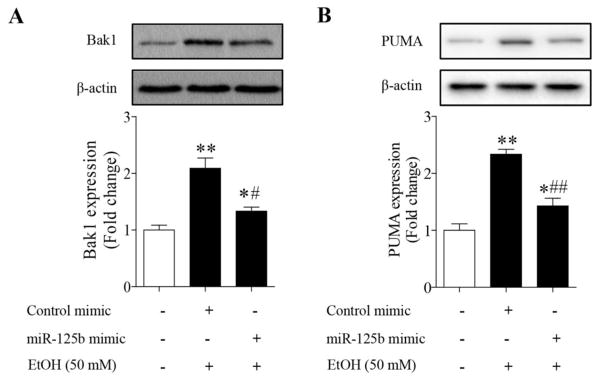

Ethanol exposure resulted in a significant increase in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression

To determine whether ethanol induces apoptosis in NCCs by up-regulation of Bak1 and PUMA through the down-regulation of miR-125b, we first determined whether ethanol exposure increases protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA in NCCs. As shown in Figure 3A, exposure to 50 mM ethanol resulted in a significant increase in Bak1 protein expression. A significant increase in PUMA protein expression was also observed in NCCs exposed to ethanol (Fig. 3B). These results indicated that miR-125b’s direct targets, Bak1 and PUMA, are involved in ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs.

Fig. 3.

Over-expression of miR-125b significantly diminished Bak1 (A) and PUMA (B) protein expression in ethanol-exposed NCCs. NCCs transfected with miR-125b mimic or control mimic were exposed to 50 mM ethanol for 24 hours. Protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA was determined by Western blot. Data are expressed as fold change over control and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control; # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. EtOH.

Overexpression of miR-125b suppressed ethanol-induced increases in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression in NCCs

To determine whether ethanol-induced decreases in miR-125b expression account for the increases in Bak1 and PUMA protein levels in ethanol-exposed NCCs, NCCs transfected with miR-125b mimic were treated with ethanol. We found that overexpression of miR-125b by miR-125b mimic significantly suppressed ethanol-induced increases in Bak1 protein expression (Fig. 3A). Up-regulation of miR-125b also significantly reduced PUMA protein expression in NCCs exposed to ethanol (Fig. 3B). These findings suggest that ethanol-induced decrease in miR-125b expression contribute to ethanol-induced up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic Bak1 and PUMA in NCCs.

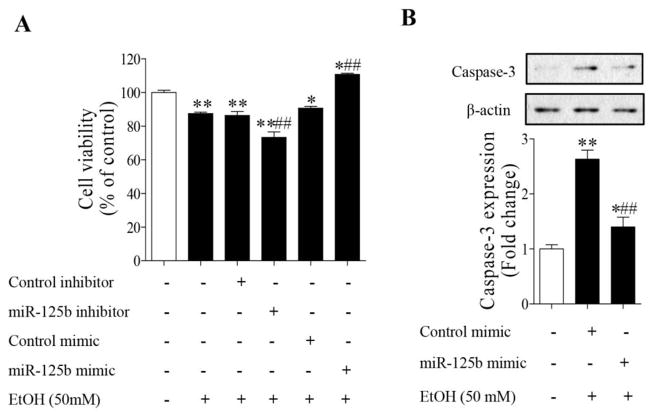

Ectopic expression of miR-125b diminished ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs

To investigate whether down-regulation of miR-125b and subsequent up-regulation of Bak1 and PUMA contribute to the ethanol-induced apoptosis and to determine the potential of miR-125b mimic in preventing ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs, miR-125b mimic or miR-125b inhibitor was transfected into the NCCs. As shown in Figure 4A, exposure of NCCs to 50 mM ethanol for 24 hours resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability. Transfection with miR-125b mimic significantly reduced the ethanol-induced reduction in cell viability. In contrast, treatment with miR-125b inhibitor resulted in a significantly greater reduction in cell viability in ethanol-exposed NCCs. In addition, treatment with miR-125b mimic greatly reduced ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation in NCCs (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that miR-125b is involved in ethanol-induced apoptosis and that overexpression of miR-125b can prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of miR-125b significantly decreased ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs. NCCs transfected with miR-125b mimic or control mimic were exposed to 50 mM ethanol for 24 hours. Cell viability was determined by MTS assay (A). Ethanol-induced apoptosis was determined by analysis of the cleavage of caspase-3 (B). Data are expressed as percentage of control (A) or fold change over control (B) and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control; # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. EtOH.

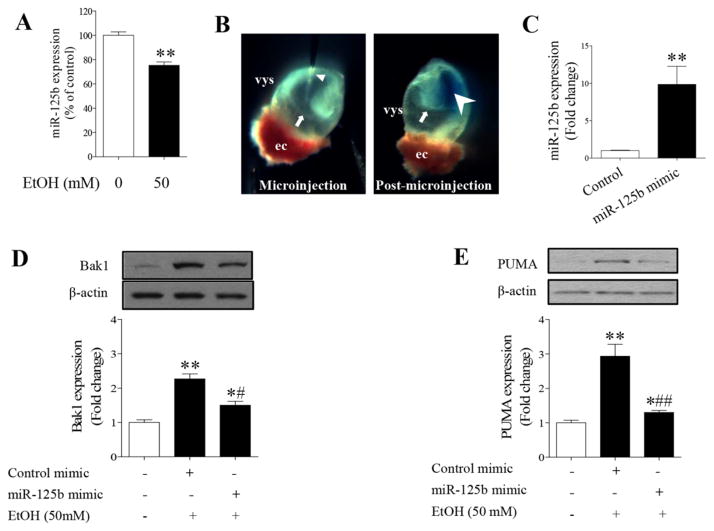

Microinjection of miR-125b mimic into cultured mouse embryos significantly reduced the protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA in ethanol-exposed mouse embryos

Based on the observations described above, we then tested the hypothesis that over-expression of miR-125b in the developing embryos can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity by diminishing the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins, Bak1 and PUMA. For this study, miR-125b mimic was microinjected into cultured mouse embryos by using an integrated technique in which whole embryo culture system was combined with microinjection techniques. This technique has been widely used to deliver viral vectors (Hartig and Hunter, 1998) or antisense oligonucleotides (Bavik et al., 1996) into cultured mouse embryos. As shown in Figure 5A, exposure of cultured mouse embryos to 50 mM ethanol significantly decreased the miR-125b expression, consisting with the results from NCCs and mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vivo. Microinjection of miR-125b mimic into cultured embryos resulted in a significant increase in miR-125b expression, indicating that this technique was able to deliver miRNA mimic into cultured embryos (Fig. 5C). Additionally, ethanol exposure resulted in a significant increase in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression in mouse embryos. Microinjection of miR-125b mimic resulted in a significant reduction in the Bak1 and PUMA protein expression in ethanol-exposed mouse embryos as compared to the group treated with control mimic and ethanol (Fig. 5D, E), confirming that microinjection of miR-125b mimic can reduce Bak1 and PUMA expression in cultured mouse embryos exposed to ethanol.

Fig. 5.

Microinjection of miR-125b mimic into cultured mouse embryos decreased ethanol-induced up-regulation of Bak1 and PUMA. (A) Exposure of cultured mouse embryos to 50 mM ethanol resulted in a significant decrease in miR-125b expression. (B) Light micrograph illustrating the microinjection of miR-125b mimic into the amniotic cavity of a mouse embryo at the 4–6 somite stage. The site of delivery of miR-125b mimic in mouse embryos is visualized by the presence of fast green dye in amniotic cavity (arrow head). Visceral yolk sac (vys); ectoplacental cone (ec); micropipette (triangle); amniotic membrane (arrow). (C) Microinjection of miR-125b mimic significantly increased miR-125b expression in mouse embryos. (D, E) Over-expression of miR125b significantly diminished ethanol-induced up-regulation of Bak1 and PUMA in mouse embryos. Data are expressed as percentage of control (A) or fold change over control (C, D, E) and represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control; # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. EtOH.

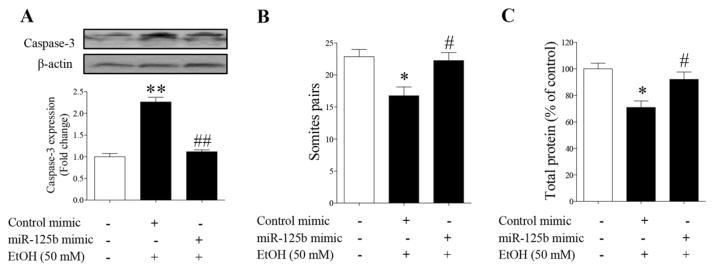

Over-expression of miR-125b significantly reduced ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation and diminished ethanol-induced growth retardation in cultured mouse embryos

To determine whether microinjection of miR-125b mimic can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity, ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation and growth retardation were examined in the cultured mouse embryos microinjected with miR-125b mimic or control mimic. As shown on Figure 6A, exposure of cultured mouse embryos to ethanol for 9 hours resulted in a significant increase in caspase-3 activation, confirming that ethanol can induce apoptosis in cultured early mouse embryos. Microinjection of miR-125b mimic significantly reduced caspase-3 activation in cultured mouse embryos exposed to ethanol. Exposure of cultured mouse embryos to 50 mM ethanol also resulted in markedly delayed in vitro development as compared with control embryos. Ethanol-induced growth retardation, as indicated by reduced somite numbers and total protein levels, was significantly reduced in cultured mouse embryos microinjected with miR-125b mimic (Fig. 6B, C). These data suggest that miR-125b mimic can diminish ethanol-induced apoptosis and reduce embryotoxicity in mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vitro.

Fig. 6.

Over-expression of miR-125b significantly diminished ethanol-induced activation of caspase-3 and embryotoxicity in cultured mouse embryos. (A) Microinjection of miR-125b mimic resulted in a significant decrease in caspase-3 activation in cultured mouse embryos exposed to 50 mM ethanol. (B) Over-expression of miR-125b mimic diminished ethanol-induced delayed in vitro development in cultured embryos as determined by somite counts. (C) Up-regulation of miR-125b reduced ethanol-induced overall growth retardation in cultured mouse embryos as indicated by the changes in the total protein contents of the embryos. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 vs. control; # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 vs. EtOH.

Discussion

MicroRNAs have been demonstrated to be involved in many biological processes, including apoptosis (Baek et al., 2008; Bartel, 2009). In the present study, we found that treatment with ethanol resulted in a significant decrease in miR-125b expression in NCCs. Exposure of mouse embryos to ethanol in vivo also significantly decreased miR-125b expression. We also found that over-expression of miR-125b significantly reduced ethanol-induced increase in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression as well as caspase-3 activation and apoptosis in NCCs. Furthermore, we have shown that microinjection of miR-125b mimic significantly decreased the protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA in ethanol-exposed mouse embryos. In addition, up-regulation of miR-125b significantly reduced ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation and diminished ethanol-induced growth retardation in cultured mouse embryos. This is the first demonstration that miR-125b can prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis and that microinjection of miRNA mimic can prevent ethanol-induced embryotoxicity.

Rapidly accumulating evidence has shown that microRNAs play an important role in modulating apoptosis. For example, miR-24a has recently been reported to affect apoptosis by negatively regulating two well-known pro-apoptotic factors caspase-9 and apaf-1 in developing neural retina (Walker and Harland, 2009). miR-34a (Raver-Shapira et al., 2007) and miR-21 (Chan et al., 2005) have also been identified as positive and negative regulator of apoptosis, respectively. In addition, miR-34a was shown to target SIRT1 (Yamakuchi et al., 2008), an NAD-dependent deacetylase that regulates apoptosis in response to oxidative and genotoxic stress. It has also been shown that blockade of miR-34a decreases apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells (Raver-Shapira et al., 2007) and human colon cancer cells (Yamakuchi et al., 2008). We show here that transfection with miR-125b mimic significantly reduced ethanol-induced apoptosis. In contrast, treatment with miR-125b inhibitor resulted in a significantly greater increase in apoptosis in ethanol-exposed NCCs. These data indicate that miR-125b is involved in ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs.

To determine the possible molecular mechanisms by which miR-125b affects apoptosis in NCCs, we used several bioinformatic tools to identify potential targets of miR-125b. As expected, results have shown that miR-125b has multiple targets, among which are Bak1 and PUMA. We chose to focus on Bak1 and PUMA because they are two key pro-apoptotic genes. When apoptosis is triggered, Bak and Bax undergo conformational changes to form homo-oligomers and mediate cytochrome c release (Wei et al., 2001). PUMA is also found to function as a direct activator of Bax and Bak (Kim et al., 2006; Kuwana et al., 2005). It has also been demonstrated that Bak can mediate ethanol-induced oxidative stress and associated apoptosis in placentas (Gundogan et al., 2010). In consistent with these studies, we have shown that ethanol exposure significantly increased both Bak1 and PUMA expression in NCCs. We found that, using luciferase analysis, co-transfection of miR-125b mimic and the 3′-UTR of Bak1 or PUMA mRNA suppressed luciferase activity. Over-expression of miR-125b in NCCs also resulted in a decrease in Bak1 and PUMA protein expression. These results demonstrate that miR-125b can directly interact with the 3′-UTR of the Bak1 and PUMA genes. The interaction of miR-125b with the 3′-UTR of the Bak1 and PUMA genes leads to a decrease in the protein expression of Bak1 and PUMA. In addition, we found that up-regulation of miR-125b significantly reduced Bak1 and PUMA protein expression and decreased apoptosis in NCCs exposed to ethanol. These findings suggest that ethanol-induced decrease in miR-125b expression contributes to ethanol-induced up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic Bak1 and PUMA in NCCs. miR-125b anti-apoptotic effects are at least partially mediated by targeting Bak1 and PUMA.

Previous studies have demonstrated that NCCs are vulnerable to ethanol-induced apoptosis and that ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs contributes heavily to subsequent abnormalities (Cartwright and Smith, 1995; Chen and Sulik, 1996; Kotch and Sulik, 1992; Sulik et al., 1981). Given that miR-125b is involved in ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs, we predict that up-regulation of miR-125b may prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis and embryotoxicity in mouse embryos. Indeed, studies have shown that miR-125b was dramatically up-regulated in normal developing embryos (Schulman et al., 2005) but impaired in pathological conditions during embryo development (Le et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2008). Notably, it has been reported recently that exposure to retinoic acid resulted in a significant decrease in miR-125b expression (Lin et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2008), and induced a spectrum of abnormalities, including spina bifida (Zhao et al., 2008). To determine the protective effects of miR-125b against ethanol-induced embryotoxicity, we microinjected miR-125b mimic into cultured mouse embryos using a technique that has been widely used to deliver viral vectors (Hartig and Hunter, 1998) or antisense oligonucleotides (Bavik et al., 1996) into cultured mouse embryos. The whole embryo culture (WEC) is considered a well-established in vitro model for identifying and characterizing teratogenic properties of test compounds and is one of the few techniques that have been validated for use in teratogenicity screening of drugs and chemicals (Sadler et al., 1982). This technique has also been widely used for the mechanistic studies of embryo development (Fujinaga et al., 1988). Several sophisticated techniques have been successfully applied to WEC, such as electroporation of nucleic acids (Osumi and Inoue, 2001), and microinjection of antisense oligonucleotides (Augustine, 1997). In addition, WEC has been used to induce region- and tissue-specific silencing of gene expression by topical injection of siRNAs (Calegari et al., 2002). Studies have demonstrated that exposure to ethanol in vivo or in cultured embryos yields comparable results, which include excessive apoptosis and dysmorphology (Chen et al., 2001; Kotch et al., 1995; Kotch and Sulik, 1992). In this study, we have shown that microinjection of miR-125b mimic resulted in a significant reduction in the expression of the two pro-apoptotic proteins Bak1 and PUMA in ethanol-exposed mouse embryos. Up-regulation of miR-125b in cultured mouse embryos also reduced the ethanol-induced caspase-3 activation, indicating that miR-125b over-expression can prevent ethanol-induced apoptosis in mouse embryos. Importantly, this study is the first to show that microinjection of miR-125b can diminish ethanol-induced growth retardation.

In conclusion, this study provides new insights into the role of miR-125b in ethanol-induced apoptosis and embryotoxicity. It shows that miR-125b is deregulated in ethanol-exposed NCCs and mouse embryos, which contributes to ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs and subsequent embryotoxicity by up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins, Bak1 and PUMA. Our results demonstrated for the first time that microinjection of miRNA mimic into mouse embryos potently inhibits ethanol-induced apoptosis and diminishes ethanol-induced embryotoxicity. The identification of miR-125b as an ethanol target in early embryos suggests that miR-125b may represent a novel therapeutic target for the development of approaches to ameliorate or prevent ethanol’s teratogenic effects. These findings provide optimism that the delivery of miR-125b mimic may ameliorate detrimental effects of fetal alcohol exposure. In addition, pharmacologic approaches or nutritional supplementation that can regulate miR-125b expression may also be effective approaches for the amelioration or prevention of FASD. While the safety and benefit of miRNA-based therapeutic strategies to prevent ethanol-induced birth defects are required to be evaluated further, the findings from the present study suggest that anti-apoptotic miR-125b may represent an attractive novel therapeutic target for the intervention and prevention of FASD.

Highlights.

Ethanol exposure decreased miR-125b expression in NCCs and in mouse embryos.

Bak1 and PUMA are the direct targets of miR-125b in NCCs.

Over-expression of miR-125b reduced ethanol-induced increase in Bak1 and PUMA.

Up-regulation of miR-125b diminished ethanol-induced apoptosis in NCCs.

Microinjection of miR-125b mimic attenuated ethanol-induced embryotoxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health grants AA020265, AA021434 (S.-YC), AA020848, and AA022416 (W. F) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and AR063630 (X. W) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Abbreviations

- 3′-UTR

3′-Untranslated region

- Bak1

Bcl-2 antagonist killer 1

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- FASD

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- GD

Gestationday

- MTS

5-[3-(carboxymethoxy)phenyl]-3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium inner salt

- NCCs

Neural crest cells

- PUMA

p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Augustine K. Antisense approaches for investigating mechanisms of abnormal development. Mutat Res. 1997;396:175–193. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine K, Liu ET, Sadler TW. Antisense attenuation of Wnt-1 and Wnt-3a expression in whole embryo culture reveals roles for these genes in craniofacial, spinal cord, and cardiac morphogenesis. Dev Genet. 1993;14:500–520. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020140611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak M, Silahtaroglu A, Moller M, Christensen M, Rath MF, Skryabin B, Tommerup N, Kauppinen S. MicroRNA expression in the adult mouse central nervous system. RNA. 2008;14:432–444. doi: 10.1261/rna.783108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavik C, Ward SJ, Chambon P. Developmental abnormalities in cultured mouse embryos deprived of retinoic by inhibition of yolk-sac retinol binding protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3110–3114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd L. Fetal alcohol syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C-Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2004;127C:1–2. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calegari F, Haubensak W, Yang D, Huttner WB, Buchholz F. Tissue-specific RNA interference in postimplantation mouse embryos with endoribonuclease-prepared short interfering RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14236–14240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192559699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright MM, Smith SM. Increased cell death and reduced neural crest cell numbers in ethanol-exposed embryos: partial basis for the fetal alcohol syndrome phenotype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JA, Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-21 is an antiapoptotic factor in human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6029–6033. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Sulik KK. Free radicals and ethanol-induced cytotoxicity in neural crest cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1071–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Wilkemeyer MF, Sulik KK, Charness ME. Octanol antagonism of ethanol teratogenesis. FASEB J. 2001;15:1649–1651. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0862fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu J, Chen SY. Sulforaphane protects against ethanol-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in neural crest cells by the induction of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:437–448. doi: 10.1111/bph.12133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Sulik KK, Chen SY. Nrf2-mediated transcriptional induction of antioxidant response in mouse embryos exposed to ethanol in vivo: implications for the prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:2023–2033. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Yan D, Chen SY. Stabilization of Nrf2 protein by D3T provides protection against ethanol-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunty WC, Jr, Chen SY, Zucker RM, Dehart DB, Sulik KK. Selective vulnerability of embryonic cell populations to ethanol-induced apoptosis: implications for alcohol-related birth defects and neurodevelopmental disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1523–1535. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynt AS, Lai EC. Biological principles of microRNA-mediated regulation: shared themes amid diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:831–842. doi: 10.1038/nrg2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinaga M, Mazze RI, Baden JM, Fantel AG, Shepard TH. Rat whole embryo culture: an in vitro model for testing nitrous oxide teratogenicity. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:401–404. 0000542-198809000-00019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundogan F, Elwood G, Mark P, Feijoo A, Longato L, Tong M, de la Monte SM. Ethanol-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in rat placenta: relevance to pregnancy loss. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:415–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK. The neural crest and neural crest cells: discovery and significance for theories of embryonic organization. J Biosci. 2008;33:781–793. doi: 10.1007/s12038-008-0098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig PC, Hunter ES., 3rd Gene delivery to the neurulating embryo during culture. Teratology. 1998;58:103–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199809/10)58:3/4<103::AID-TERA6>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, Wozniak DF, Koch C, Genz K, Price MT, Stefovska V, Horster F, Tenkova T, Dikranian K, Olney JW. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science. 2000;287:1056–1060. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5455.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Rafiuddin-Shah M, Tu HC, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1348–1358. doi: 10.1038/ncb1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch LE, Chen SY, Sulik KK. Ethanol-induced teratogenesis: free radical damage as a possible mechanism. Teratology. 1995;52:128–136. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420520304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch LE, Sulik KK. Patterns of ethanol-induced cell death in the developing nervous system of mice; neural fold states through the time of anterior neural tube closure. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1992;10:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(92)90016-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Chipuk JE, Bonzon C, Sullivan BA, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol Cell. 2005;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Shyh-Chang N, Khaw SL, Chin L, Teh C, Tay J, O’Day E, Korzh V, Yang H, Lal A, Lieberman J, Lodish HF, Lim B. Conserved regulation of p53 network dosage by microRNA-125b occurs through evolving miRNA-target gene pairs. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Teh C, Shyh-Chang N, Xie H, Zhou B, Korzh V, Lodish HF, Lim B. MicroRNA-125b is a novel negative regulator of p53. Genes Dev. 2009;23:862–876. doi: 10.1101/gad.1767609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Kim HK, Chung S, Kim KS, Dutta A. Depletion of human micro-RNA miR-125b reveals that it is critical for the proliferation of differentiated cells but not for the down-regulation of putative targets during differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16635–16641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin KY, Zhang XJ, Feng DD, Zhang H, Zeng CW, Han BW, Zhou AD, Qu LH, Xu L, Chen YQ. miR-125b, a target of CDX2, regulates cell differentiation through repression of the core binding factor in hematopoietic malignancies. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38253–38263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, Baldwin DA, Kloosterman WP, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RH, Mourelatos Z. RAKE and LNA-ISH reveal microRNA expression and localization in archival human brain. RNA. 2006;12:187–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.2258506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi N, Inoue T. Gene transfer into cultured mammalian embryos by electroporation. Methods. 2001;24:35–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2459-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzykowski AZ, Friesen RM, Martin GE, Puig SI, Nowak CL, Wynne PM, Siegelmann HT, Treistman SN. Posttranscriptional regulation of BK channel splice variant stability by miR-9 underlies neuroadaptation to alcohol. Neuron. 2008;59:274–287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Zhang M, Li H, Frank JA, Dai L, Liu H, Chen G. MicroRNA-29b regulates ethanol-induced neuronal apoptosis in the developing cerebellum through SP1/RAX/PKR cascade. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:10201–10210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.535195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver-Shapira N, Marciano E, Meiri E, Spector Y, Rosenfeld N, Moskovits N, Bentwich Z, Oren M. Transcriptional activation of miR-34a contributes to p53-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler TW, Horton WE, Warner CW. Whole embryo culture: a screening technique for teratogens? Teratog Carcinog Mutagen. 1982;2:243–253. doi: 10.1002/1520-6866. (1990) 2:3/4<243::AID-TCM1770020306>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyan P, Golden HB, Miranda RC. Competing interactions between micro-RNAs determine neural progenitor survival and proliferation after ethanol exposure: evidence from an ex vivo model of the fetal cerebral cortical neuroepithelium. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8546–8557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1269-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman BR, Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ. Reciprocal expression of lin-41 and the microRNAs let-7 and mir-125 during mouse embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:1046–1054. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulik KK, Johnston MC, Webb MA. Fetal alcohol syndrome: embryogenesis in a mouse model. Science. 1981;214:936–938. doi: 10.1126/science.6795717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarbrick A, Woods SL, Shaw A, Balakrishnan A, Phua Y, Nguyen A, Chanthery Y, Lim L, Ashton LJ, Judson RL, Huskey N, Blelloch R, Haber M, Norris MD, Lengyel P, Hackett CS, Preiss T, Chetcuti A, Sullivan CS, Marcusson EG, Weiss W, L’Etoile N, Goga A. miR-380-5p represses p53 to control cellular survival and is associated with poor outcome in MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Nat Med. 2010;16:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang WP, Kwok TT. Let-7a microRNA suppresses therapeutics-induced cancer cell death by targeting caspase-3. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1215–1222. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JC, Harland RM. microRNA-24a is required to repress apoptosis in the developing neural retina. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1046–1051. doi: 10.1101/gad.1777709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia HF, He TZ, Liu CM, Cui Y, Song PP, Jin XH, Ma X. MiR-125b expression affects the proliferation and apoptosis of human glioma cells by targeting Bmf. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;23:347–358. doi: 10.1159/000218181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S, Pandey A, Shukla A, Talwelkar SS, Kumar A, Pant AB, Parmar D. miR-497 and miR-302b regulate ethanol-induced neuronal cell death through BCL2 protein and cyclin D2. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37347–37357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Lowenstein CJ. miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13421–13426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801613105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JJ, Sun DG, Wang J, Liu SR, Zhang CY, Zhu MX, Ma X. Retinoic acid downregulates microRNAs to induce abnormal development of spinal cord in spina bifida rat model. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]