Abstract

Excitotoxicity plays a critical role in neurodegenerative disease. Cytosolic calcium overload and mitochondrial dysfunction are among the major mediators of high level glutamate-induced neuron death. Here, we show that the transient opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (tMPT) bridges cytosolic calcium signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction and mediates glutamate-induced neuron death. Incubation of the differentiated motor neuron-like NSC34D cells with glutamate (1 mM) acutely induces cytosolic calcium transient (30% increase). Glutamate also stimulates tMPT opening, as reflected by a 2-fold increase in the frequency of superoxide flash, a bursting superoxide production event in individual mitochondria coupled to tMPT opening. The glutamate-induced tMPT opening is attenuated by suppressing cytosolic calcium influx and abolished by inhibiting mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) with Ru360 (100 µM) or MCU shRNA. Further, increased cytosolic calcium is sufficient to induce tMPT in a mitochondrial calcium dependent manner. Finally, chronic glutamate incubation (24 hr) persistently elevates the probability of tMPT opening, promotes oxidative stress and induces neuron death. Attenuating tMPT activity or inhibiting MCU protects NSC34D cells from glutamate-induced cell death. These results indicate that high level glutamate-induced neuron toxicity is mediated by tMPT, which connects increased cytosolic calcium signal to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Keywords: Glutamate, Excitotoxicity, Mitochondrial calcium uniporter, Transient mitochondrial permeability transition, Superoxide flashes, Neuron death

Introduction

Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous system of vertebrates and critically participates in the normal function of neurons, especially the cognitive functions such as learning and memory (Meldrum, 2000). Excessive glutamate in synapses, however, can induce neuron dysfunction and death, termed excitotoxicity, which contributes to aging-related neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993; Dong et al., 2009; Nunomura et al., 2001). ALS is a fatal motor neuron degenerative disease with complicated etiology that involves genetic and none-genetic factors (Turner et al., 2013). High levels of glutamate were found in the serum and spinal fluid of ALS patients (Al-Chalabi and Leigh, 2000) and a compound that facilitates glutamate uptake from the synapses has been approved by FDA for ALS treatment (Azbill et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2011; Rothstein, 1996). Therefore, it is generally agreed that excessive glutamate contributes to motor neuron death in ALS.

Activation of glutamate receptors increases cytosolic calcium (Ca2+), which may lead to cell dysfunction and neuron death (Choi, 1990; Manev et al., 1989; Murphy and Miller, 1989; Stout et al., 1998). One of the downstream effect of increased cytosolic Ca2+ is mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and accumulation via mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), which has been associated with glutamate-induced neuron death (Duan et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2013). Another mediator of glutamate toxicity is oxidative stress (Simpson et al., 2003). Glutamate may affect intracellular redox balance or promote mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Simpson et al., 2003). It would seem logical that mitochondrial Ca2+ overload damages mitochondrial function leading to decreased respiration, membrane depolarization and ROS production (Adam-Vizi and Starkov, 2010; Mehta et al., 2013). However, mitochondrial Ca2+ is an essential stimulator of respiration, which is the major source of ROS in cells. Thus, a causal link between mitochondrial Ca2+ and oxidative stress is elusive (Adam-Vizi and Starkov, 2010; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010). A recent study showed that mitochondrial Ca2+ may attenuate oxidative stress by reducing mis-folded superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) (Parone et al., 2013). Taken together, the interplay among cytosolic Ca2+, mitochondrial Ca2+ and mitochondrial dysfunction in glutamate-induced neuron toxicity is complicated and not fully understood (Duan et al., 2007).

Mitochondrial Ca2+ plays multiple roles in cell physiology and pathology (Martin, 2012; Nicholls, 2009). Mitochondrial Ca2+ critically regulates energy metabolism by stimulating the activity of TCA cycle enzymes and electron transport chain (ETC) complexes (Griffiths and Rutter, 2009). However, Ca2+ overload is often detrimental and links to mitochondrial dysfunction (Duchen, 2012; Feissner et al., 2009; Vay et al., 2009). An emerging view of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis is that mitochondria undergo transient permeability transition pore (tMPT) openings, which can be triggered by Ca2+ and serves to release excessive Ca2+ from mitochondrial matrix (Elrod and Molkentin, 2013; Ichas et al., 1997; Petronilli et al., 1999). We recently determined a novel role of tMPT, which is to stimulate ETC activity to generate bursting superoxide in individual mitochondria, termed superoxide flashes (Fang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008; Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013). Importantly, these tMPT-induced superoxide flashes are physiological events. However, excessive activation of tMPT may play a role in pathology (Fang et al., 2011; Hou et al., 2013a; Shen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2008). Given the above interplay among mitochondrial Ca2+, tMPT and ROS production (Brookes et al., 2004), we hypothesize that activation of glutamate receptors stimulates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, which triggers tMPT in single mitochondria. Excessive and prolonged activation of tMPT may lead to oxidative stress and neuron death.

To test this hypothesis, we treated NSC34D cells, a motor neuron-like cell line, with a moderate-to-high level of glutamate (1 mM) for up to 48 hr. tMPT activity was monitored by superoxide flash events in individual mitochondria of intact cells. We found that glutamate treatment acutely and persistently increased single mitochondrial tMPT opening probability in a mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent manner. Prolonged activation of the mitochondrial tMPT impaired mitochondrial function, caused oxidative stress and induced neuron death.

Materials and Methods

Neuron culture, differentiation and gene transfer

The motor neuron-like cell line, NSC34 cells, which were the hybrid cell line produced by fusion of neuroblastoma with mouse motoneuron-enriched primary spinal cord cells, were kindly provided by Dr. Neil Cashman (University of British Columbia) and were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and L-glutamine. To differentiate NSC34 to NSC34D, NSC34 cells are grown to 70% confluence, and medium changed to: DMEM (50%) + Ham’s F12 (50%, Gibco), 1% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% modified Eagle’s medium nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen). This medium change has been shown to slow down cell growth and cause considerable number of cells to die 24–48 hr after the medium change (Eggett et al., 2000). The survived cells (NSC34D) showed very long processes (Eggett et al., 2000). These cells can be sub-cultured to ~3 passages. Experiments were carried out on NSC34D cells, which showed long processes, 2 weeks after the differentiation.

Construction of recombinant adenoviral vectors containing mt-cpYFP (Ad-mt-cpYFP) has been described previously (Wang et al., 2008). The mt-cpYFP has been shown to respond to superoxide specifically at 488 nm excitation and ratiometric measurement of bursting superoxide production events, termed superoxide flashes, in intact cells is achieved by dual wavelength excitation (488 and 405 nm) (Wang et al., 2008). Ad-mt-cpYFP was amplified in HEK 293 cells and purified by standard CsCl gradient centrifugation followed by overnight dialysis. The concentration of virus was determined to be at ~1 × 1011 viral particles per ml. Adv-SOD2 virus was a kind gift from Dr. John F. Engelhardt (University of Iowa) (Zwacka et al., 1998a; Zwacka et al., 1998b). All the viruses were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer was done in NSC34D cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. Lentivirus containing 5 different sequences of MCU shRNA or a control scrambled shRNA (SC shRNA) were purchased from Sigma and used at an MOI of 5.

Confocal imaging of single mitochondrial superoxide flashes and whole cell Ca2+

Confocal imaging used a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope equipped with a 40× 1.3NA oil immersion objective and followed a procedure developed previously (Wang et al., 2008). To detect superoxide flashes, cells were incubated in modified KHB solutions containing 138 mM NaCl, 3.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 15 mM Glucose, 20 mM HEPES and 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4 at room temperature and in a custom designed perfusion chamber mounted on confocal microscope stage. Dual excitation images of mt-cpYFP were taken by alternating excitation at 405 and 488 nm and collecting emissions at >505 nm. Time-lapse x, y images were acquired at 1024 resolution (x axis, y axis was adjusted according to the shape of cells, usually between 300–400 pixels, pixel size ~0.1 µm) for 100 frames and at a sampling rate of ~1 s per frame. In a subset of experiments, mitochondrial membrane potential indicator, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM 20 nM, Invitrogen) was loaded into cells and tri-wavelength imaging of mt-cpYFP and TMRM was taken by sequential excitation at 405, 488, and 543 nm, and emissions collected at 505–550, 505–550 and >560 nm, respectively. Digital image processing used IDL software (Research Systems) and customer-devised programs.

To monitor cytosolic Ca2+, we loaded cells with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, fluo-4-AM (Invitrogen, 10 µM) for 30 min followed by 30 min washout. Confocal 2D images were collected by excitation at 488 nm and collecting emissions at >505 nm. The whole cell fluorescence (soma and neurites) were used.

Western blot

To detect gene expression in cultured NSC34 and NSC34D cells, cell were harvested in lysis buffer (Cell Signaling). Protein samples were quantified by BCA assay (Pierce) and equal amount of proteins were loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and probed with antibodies specific for human SOD2 (1:1000, Calbiochem), GluR2 (1:1000, NeuroMab), or actin (1:2000, Sigma). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to IRDye 800 (Rockland) or Alexa Fluor 680 (Invitrogen) and signals were visualized and quantified using Odyssey system (Licor).

Confocal imaging of mitochondrial membrane potential and oxidative stress

Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by JC-1 (5 µM, Invitrogen), a ratiometric dye that facilitates the accurate determination of membrane potential. JC-1 fluorescence was monitored by excitation at 488 nm and emissions collected at 505–545 nm (green) and >560 nm (red). The ratio of red/green fluorescence was used to determine membrane potential, the higher this ratio the more polarized the mitochondrial membrane. To monitor mitochondrial superoxide levels, MitoSOX Red (5 µM, Invitrogen) was loaded into NSC34D cells at 37°C for 10 min followed by washing two times. MitoSOX fluorescence was detected by excitation at 405 and 514 nm, and both emissions collected at >560 nm. To avoid saturation by excessive oxidation, all MitoSOX experiments were completed within 30 min of loading. To determine cellular oxidation, CM-H2DCFDA (10 µM, Invitrogen) was loaded into cells and fluorescence monitored by excitation at 488 nm and emission collected at >505 nm. Image analysis used ImageJ software.

Cell viability assay

Trypan blue exclusion assay was used to test cell viability. Briefly, cells were incubated in trypan blue (0.2–0.4% in PBS) for 2 min at room temperature and then washed twice. Images were taken within 3 to 5 min of trypan blue washout by a light microscope with a 4× lens. At least 5 fields were counted from 1 well. Unstained cells (clear) were counted as viable and cells with blue color were damaged.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. One way ANOVA, and paired or unpaired Student’s T test were used when appropriate to determine statistical significance among groups. A p value of less than 0.05 was deemed significant. Multiple comparisons test were performed, if ANOVA shows p <0.05.

Results

Glutamate induced superoxide flashes in motor neurons

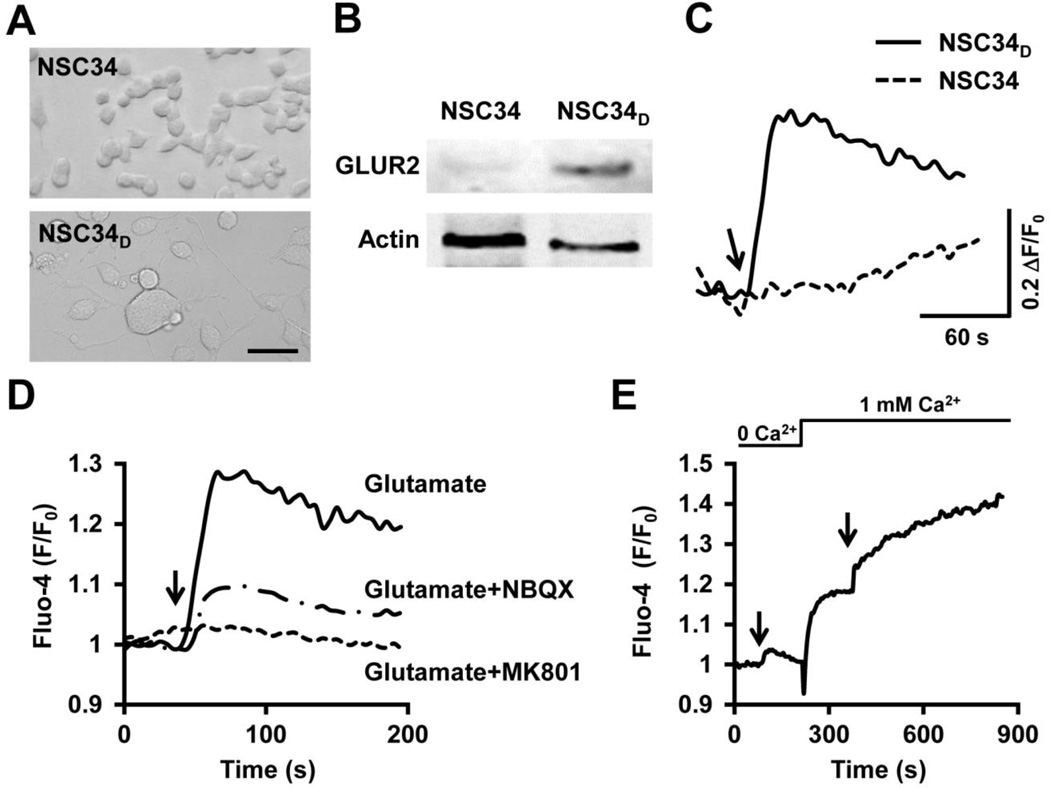

To determine the role of tMPT in glutamate-induced motor neuron death, we used an in vitro model, in which a motor neuron cell line NSC34 was differentiated to NSC34D cells by culturing in low FBS medium for more than 2 weeks (Eggett et al., 2000). NSC34D cells were more mature, exhibited neuron-like morphology with long processes, expressed glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) and NMDA receptors (Eggett et al., 2000), and responded to glutamate (1 mM) stimulation with a significant increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Figs. 1A–C) (Eggett et al., 2000). The glutamate-induced elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ was blocked by pre-incubation of glutamate receptor antagonists (Fig. 1D). Next, this increased cytosolic Ca2+ has two components, Ca2+ release from intracellular storage and Ca2+ influx across cell membrane. The latter is a major component, because removal of extracellular Ca2+ resulted in significantly blunted cytosolic Ca2+ increase (Fig. 1E), while adding back Ca2+ elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Fig. 1E). These results indicate that the NSC34D cells are reliable models to test the glutamate toxicity.

Fig. 1.

Differentiated NSC34D motor neuron cells responded to glutamate. A–C, Differentiation of the motor neuron cell line NSC34 cells to the differentiated NSC34D cells, which exhibited long projections extended from soma (A), expressed glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2, B), and showed elevated cytosolic Ca2+ in response to glutamate (1 mM, arrow) (C). Scale bar in A, 50 µm. D, Glutamate increased cytosolic Ca2+ in NSC34D cells, which was attenuated by pre-incubation (added 30 min before glutamate) of glutamate receptor inhibitors, MK801 (10 µM) or NBQX (1 µM). E, Inhibiting Ca2+ influx by removing extracellular Ca2+ attenuated glutamate-induced cytosolic Ca2+ increase. Arrows indicate the addition of glutamate (1 mM). Images in A and traces in C–E are representative of at least 10 cells/images from 3 independent experiments.

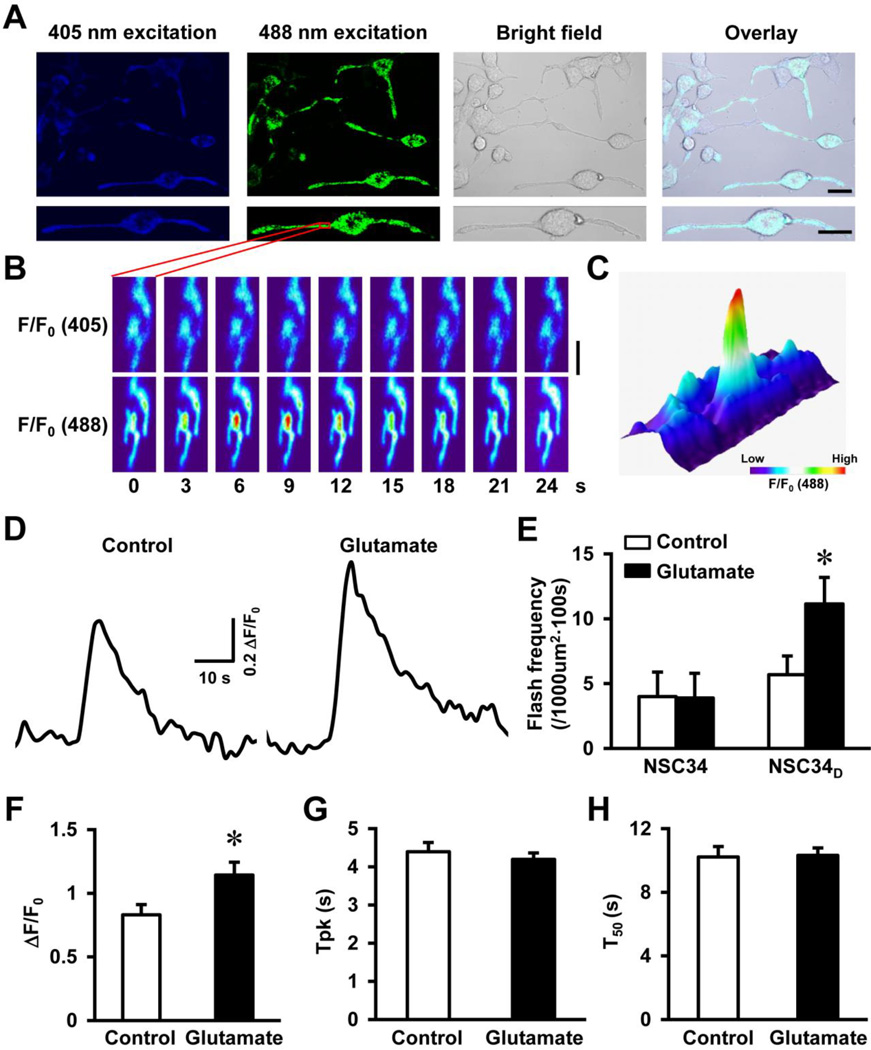

Next, we introduced the superoxide indicator, mt-cpYFP into NSC34D cells (2 weeks after the differentiation) via adenovirus-mediated gene transfer (Wang et al., 2008). Three days after the infection, a clear mitochondrial expression pattern of the indicator was observed in the soma and neurites of 100% of the neurons under confocal microscope (Fig. 2A). In normal cultured NSC34D cells, discrete and transient increases in single mitochondrial mt-cpYFP fluorescence were observed by 488 nm excitation, which corresponded to superoxide flash events (Figs. 2B–C). Importantly, the moderate levels of glutamate (1 mM), which has been shown to induce 20–30% of neuron death (Eggett et al., 2000), acutely and significantly increased the frequency and amplitude of flashes in majority of the NSC34D cells (frequency from 5.7 ± 1.4 to 11.1 ± 2.0 flashes per 1000 µm2 per 100 s and amplitude from 0.8 ± 0.1 to 1.1 ± 0.1, p < 0.05, Figs. 2D–F). In contrast, although undifferentiated NSC34 cells have a basal flash activity similar to that of NSC34D cells, flash frequency in NSC34 cells was not increased upon glutamate treatment (Fig. 2E). The kinetics of flashes was not changed by glutamate treatment (Figs. 2G–H) and was highly comparable to the flashes found in other cell types (Wang et al., 2008; Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013). These results suggest that glutamate specifically stimulates superoxide flashes in differentiated motor neurons.

Fig. 2.

Glutamate stimulated superoxide flash activity in motor neurons. A, Representative confocal images showed NSC34D cells expressing mitochondrial targeted superoxide indicator, mt-cpYFP, in soma and neurites (excitation by 405 and 488 nm laser, Upper panel). The enlarged images showed mitochondrial expression pattern of mt-cpYFP in a neuron (Lower panel). Scale bars = 20 µm. B, Time lapse images of a small area of the neuron highlighted by red box in A at 405 or 488 nm excitation. The pseudo-colors indicate relative fluorescence intensity (F/F0). A single mitochondrial superoxide flash event was detected at 488 nm excitation which peaked at 6–9 s, as shown by the dramatically increased fluorescence. Scale bar = 2 µm. C, 3D surface plot of the area shown in B and at the peak of the single mitochondrial superoxide flash. The same color code applies to both B and C. D, Representative traces of superoxide flashes in NSC34D cells before and after glutamate (1 mM, 10 min) treatment. E, Summarized data showing flash frequency in NSC34 and NSC34D before and after glutamate treatment (1 mM, 10 min). N = 6–8 cells. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. F-H, Flash amplitude (ΔF/F0, F), time to peak (Tpk, G), and time to 50% decay (T50, H) in NSC34D cells before and after glutamate treatment. N = 65–117 flashes from 10 cells in each group. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM.

tMPT underlay superoxide flash in motor neurons

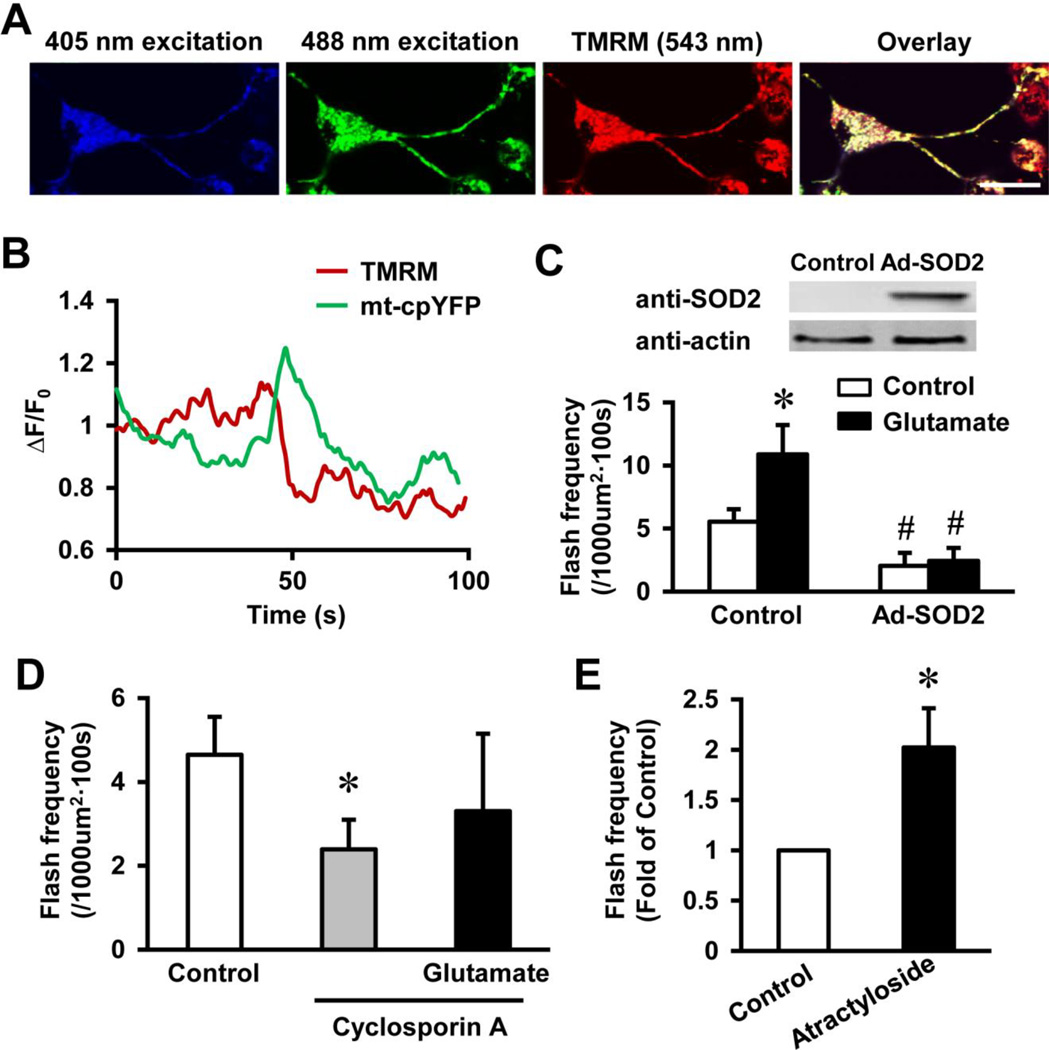

A unique feature always accompanying superoxide flashes is the release of mitochondrial matrix molecules around 1 kd during each flash event (Hou et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2008; Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013), which indicates transient opening of a large and non-specific pore. In cardiac muscles and neurons, this pore is mitochondrial permeability transition pore, since inhibition of this pore attenuated flash events (Hou et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2008). Transient opening of this pore (tMPT) is known to exist and Ca2+ is a known activator of tMPT (Ichas et al., 1997; Petronilli et al., 1999). To confirm whether tMPT underlies glutamate-induced flash activity in the NSC34D motor neurons, we simultaneously monitored single mitochondrial superoxide flashes with membrane potential by TMRM, which co-localized with mt-cpYFP (Fig. 3A). Importantly, each flash under resting condition or after glutamate treatment was coupled with an abrupt loss of membrane potential (Fig. 3B), which is consistent with previous findings and indicates opening of tMPT (Wang et al., 2008). Previously, we have reported variations in the recovery time course of membrane potential after the flash (Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013), similar variations were observed in NSC34D cells at resting condition and after glutamate treatment.

Fig. 3.

Transient openings of permeability transition pore (tMPT) underlay basal and glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity in motor neurons. A, Representative images of a NSC34D cell expressing mt-cpYFP and loaded with mitochondrial membrane potential indicator, TMRM (20 nM). Scale bar = 20 µm. B, Traces showing a superoxide flash accompanied by mitochondrial membrane depolarization after glutamate (1 mM) treatment. C, Adenovirus-mediated human SOD2 expression in NSC34D inhibited basal and glutamate-induced flash activity. N = 6–22 cells. *, p < 0.05 versus Control and #, p < 0.01 versus without Ad-SOD2 by ANOVA and unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. D, tMPT inhibitor, cyclosporin A (1 µM), suppressed basal and glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity. N = 7–14 cells. *, p < 0.05 by ANOVA and unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. E, tMPT activator, atractyloside (10 µM) stimulated flash activity in NSC34D cells. N = 8 cells. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test. Vertical bar is SEM.

Next, we determined whether regulators of tMPT can modulate glutamate-induced flash activity. First, overexpression of SOD2 in NSC34D cells attenuated basal flash activity and totally blocked the glutamate-induced flash activity (flash frequency for Control: 5.5 ± 1.0 and for glutamate: 10.8 ± 2.3 flashes per 1000 µm2 per 100 s, p < 0.05; and flash frequency for Ad-SOD2: 2.0 ± 0.5 and for Ad-SOD2 + glutamate: 2.4 ± 1.0 flashes per 1000 µm2 per 100 s, p < 0.01 versus Control, Fig. 3C), consistent with that ROS triggers the pore opening (Wang et al., 2008). Second, we pre-treated the neurons with a tMPT blocker, cyclosporin A (1 µM), which inhibited the known tMPT component, cyclophilin D. Cyclosporin A not only inhibited basal flash activity but also prevented glutamate-stimulated flash activity in NSC34D cells (flash frequency for Control, cyclosporin A and cyclosporin A + glutamate: 4.6 ± 0.9, 2.4 ± 0.7 and 3.3 ± 1.8 flashes per 1000 µm2 per 100 s, respectively, Fig. 3D). Conversely, a tMPT activator, atractyloside, significantly increased flash activity in NSC34D cells (Fig. 3E). Taken together, these results support that tMPT underlies glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity in motor neurons.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake stimulated tMPT

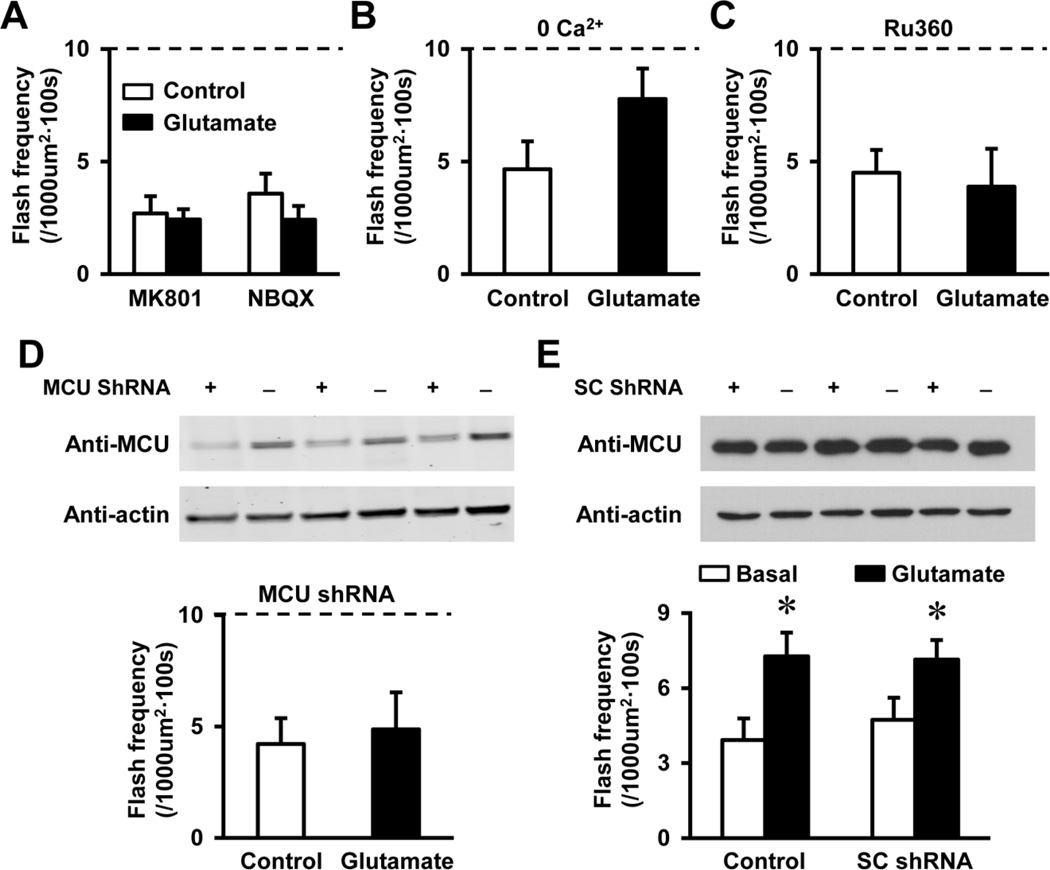

To further elucidate the mechanism of glutamate-induced tMPT activity, we tested whether the increased cytosolic Ca2+ played a role. First, specific antagonists of glutamate receptors, MK801 and NBQX completely blocked glutamate-induced flash activity in NSC34D cells (Fig. 4A), indicating that increased cytosolic Ca2+ was involved. To directly test whether cytosolic Ca2+ is responsible for increased flash activity, we removed extracellular Ca2+, which blocked Ca2+ influx, the major component of glutamate-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transient (Fig. 1E). Indeed, glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity was partially attenuated by removing Ca2+ in the solutions (Fig. 4B), suggesting that glutamate-induced flashes largely depends on Ca2+ influx and partially depends on Ca2+ release from intracellular stores.

Fig. 4.

Glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity required mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake during cytosolic Ca2+ increase. A, Glutamate receptor inhibitors, MK801 (10 µM) and NBQX (1 µM), blocked glutamate (1mM for 10 min)-induced superoxide flash activity. N = 11–12 cells. Vertical bars are SEM. The dashed line indicates the level of glutamate-induced flash frequency (Mean value of the NSC34D + glutamate group in Figure 2E), which also applies for B, C and E. B-C, Glutamate-induced superoxide flash activity was attenuated by removal of extracellular Ca2+ (B), and was abolished by inhibiting mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) by Ru360 (100 µM, C). N = 10–14 cells. Vertical bars are SEM. Note while removing extracellular Ca2+, no Ca2+ chelator was added, and residual Ca2+ may exist in the solution, which could be responsible for the slight but insignificant increase of flash events by glutamate in B. D, Lentivirus-mediated expression of MCU shRNA decreased protein levels of MCU and abolished glutamateinduced flash activity in NSC34D cells. N = 14 cells from 3 independent experiments. Vertical bars are SEM. E, Lentivirus-mediated expression of a control scrambled shRNA sequence (SC shRNA) has no effect on MCU levels, and basal or 1 mM glutamate-induced flash frequency in NSC34D cells. N = 12–16 cells from 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus Basal by unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM.

How increased cytosolic Ca2+ triggers tMPT is further determined. Mitochondria is known to take up Ca2+ in response to increased cytosolic Ca2+ levels in both neurons and other excitable cells (Duchen, 2012). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is mainly through MCU residing on the inner mitochondrial membrane (Baughman et al., 2011; De Stefani et al., 2011). Therefore, we used a specific inhibitor of MCU, Ru360, which totally blocked the effect of glutamate on superoxide flash activity (Fig. 4C), suggesting a causal role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in glutamate-stimulated flashes. Moreover, lentivirus mediated expression of shRNAs targeting MCU effectively abolished glutamate-induced flash activity in NSC34D cells (Fig. 4D), while a control scrambled shRNA sequence (SC shRNA) has no effect on MCU protein levels, basal flash frequency and 1 mM glutamate-induced flash frequency in NSC34D cells (Figs. 4E). These results indicate that increased cytosolic Ca2+ promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via MCU and subsequently triggers tMPT and superoxide flashes.

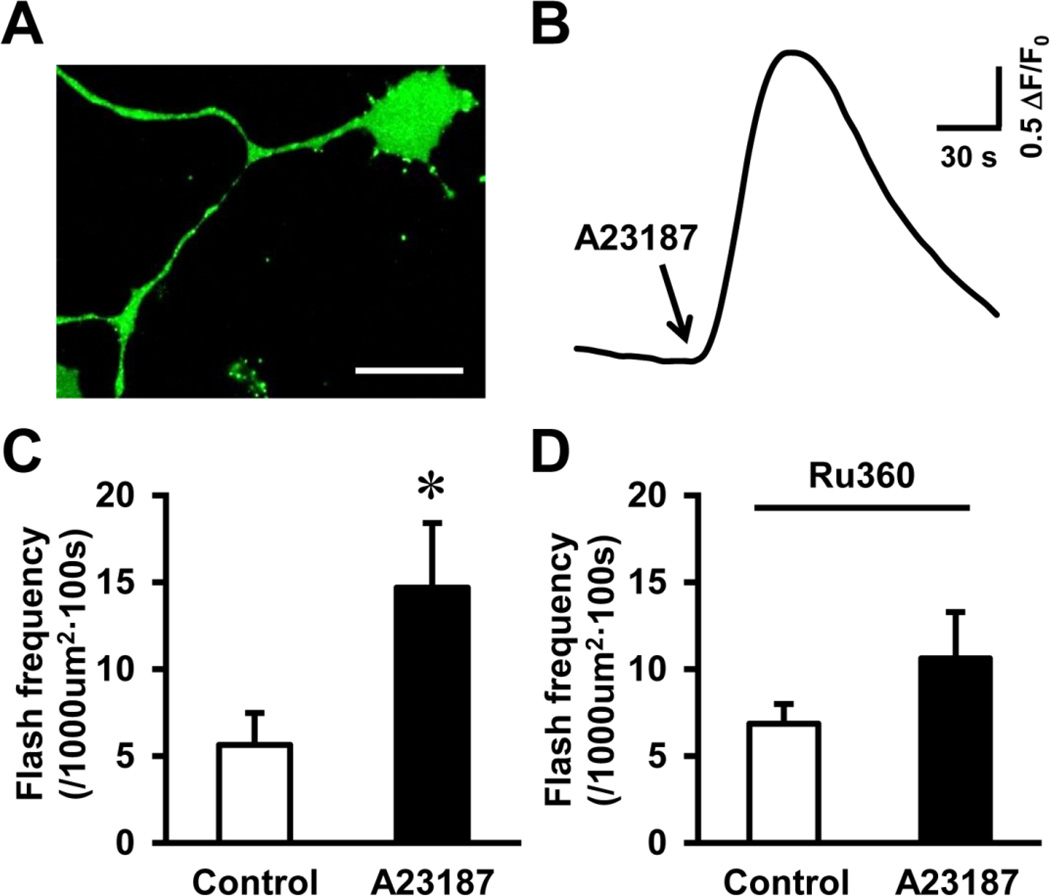

Glutamate-induced toxicity involves multiple signaling pathways beside increased cytosolic Ca2+ (Mehta et al., 2013). To test whether cytosolic Ca2+ played a major role in glutamate-stimulated tMPT, we employed a pharmacological approach to specifically increase cytosolic Ca2+, while bypassing glutamate receptors. A23187 is a Ca2+ ionophore that transports Ca2+ across cell membrane. A23187 acutely induced a dramatic increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels in NSC34D cells (Figs. 5A–B), which was accompanied by significantly increased flash activity (Fig. 5C). Further, blocking mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake by Ru360 attenuated A23187-induced flashes (Fig. 5D). These results suggest that increased cytosolic Ca2+ is sufficient to induce mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and trigger tMPT.

Fig. 5.

Cytosolic Ca2+ leads to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and increased superoxide flashes in motor neurons. A, Representative image showing a NSC34D cell loaded with Ca2+ indicator, Fluo-4, in cytosol (soma and neurites). Scale bar = 50 µm. B, Trace showing Ca2+ ionophore, A23187 (1 µM, 10 min) increased cytosolic Ca2+ in NSC34D cells. C-D, A23187 stimulated superoxide flash activity (C), which was blocked by mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter inhibitor, Ru360 (100 µM, D). N = 8–10 cells. *, p < 0.05 by t test. Vertical bars are SEM.

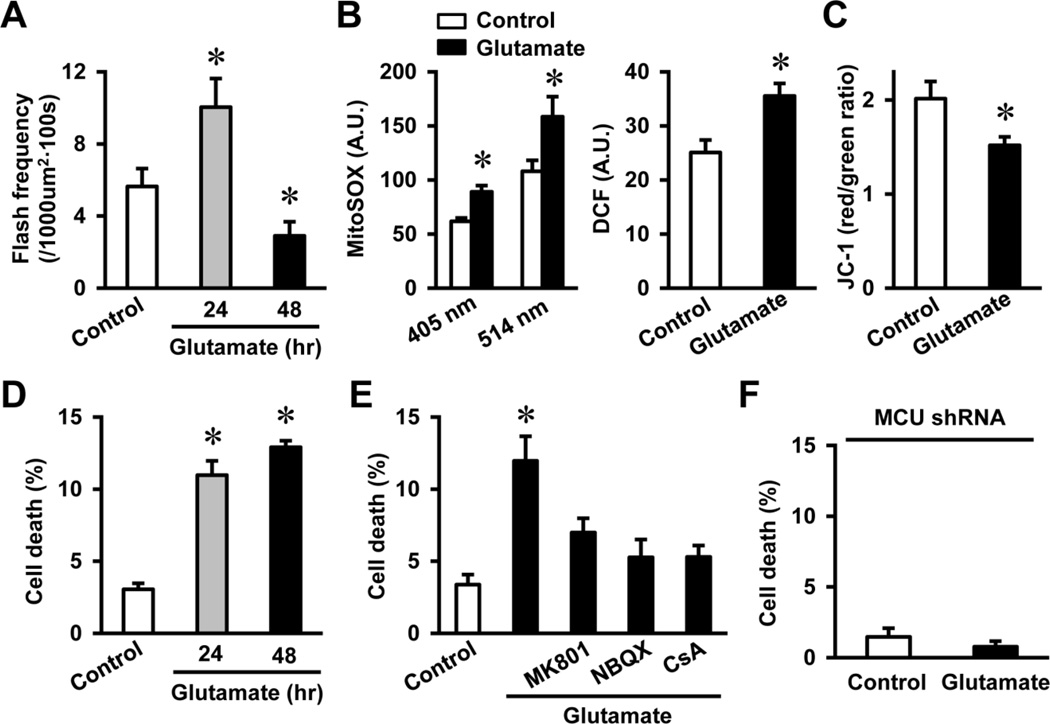

Chronic glutamate treatment caused oxidative mitochondrial dysfunction and neuron death through excessive tMPT

We further asked whether activation of tMPT played a role in glutamate-induced neuron death. As chronic glutamate treatment induces neuron death, we first determined the time dependent effect of glutamate on superoxide flash activity. Superoxide flash frequency remained elevated after 24 hr of glutamate treatment and declined at 48 hr (flash frequency for Control, 24 hr and 48 hr glutamate: 5.6 ± 1.0, 10.0 ± 1.6 and 2.9 ± 0.8 flashes per 1000 µm2 per 100 s, respectively, p < 0.05 versus Control, Fig. 6A). The persistently increased flash activity was accompanied by increased steady state mitochondrial and cytosolic oxidation as measured by MitoSOX and DCF, respectively (Fig. 6B), and a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential after 24 hr of glutamate treatment (Fig. 6C). At the meantime, neuron death was significantly increased after 24 hr of glutamate treatment (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that prolonged or excessive activation of tMPT can lead to oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neuron death during chronic glutamate treatment. To determine the causal role of tMPT in glutamate-induced neuron death, we pre-treated NSC34D cells with blockers of glutamate receptor, tMPT, or MCU before the chronic glutamate treatment. These blockers effectively attenuated glutamate-induced neuron death (Figs. 6E–F), supporting a causal role of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and excessive tMPT in neuron death.

Fig. 6.

Chronic glutamate treatment continuously stimulated superoxide flash activity and induced oxidative mitochondrial dysfunction and neuron death. A, Superoxide flash activity was increased by glutamate (1 mM) treatment for 24 hr and decreased after 48 hr treatment. N = 7–20 cells. *, p < 0.05 by ANOVA and unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. B, Glutamate (1 mM) treatment for 24 hr increased mitochondrial and cytosolic oxidative stress as shown by increased MitoSOX and DCF signals, respectively. N = 24–30 cells. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. C, Mitochondrial membrane depolarization after 24 hr glutamate (1 mM) treatment as shown by decreased JC-1 red/green ratio. N = 39–42 cells. *, p < 0.05 by unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM. D-F, Chronic and high level glutamate treatment (1 mM, 24–48 hr) induced NSC34D cell death (D), which was blocked by glutamate receptor antagonists, tMPT blockade (E) and MCU shRNA (F). N = 13–26 images from 3 independent measurements. Each image contains 50–100 cells. *, p < 0.05 by ANOVA and unpaired t test. Vertical bars are SEM.

It should be noted that superoxide flash frequency was declined to below basal level after 48 hr of glutamate treatment (Fig. 6A). An explanation of this biphasic change would be that the prolonged increase in flash activity for up to 24 hr leads to mitochondrial dysfunction as shown by mitochondrial depolarization and increased oxidative stress. We have shown that superoxide flash requires polarized mitochondrial inner membrane and intact ETC activity. Further, flash is accompanied by a mild alkalinization of the mitochondrial matrix and a decrease in NADH level and depends on intact ETC (Wang et al., 2008; Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013). Therefore, significantly decreased flash activity at 48 hr corroborates the impaired mitochondrial respiratory function.

Discussion

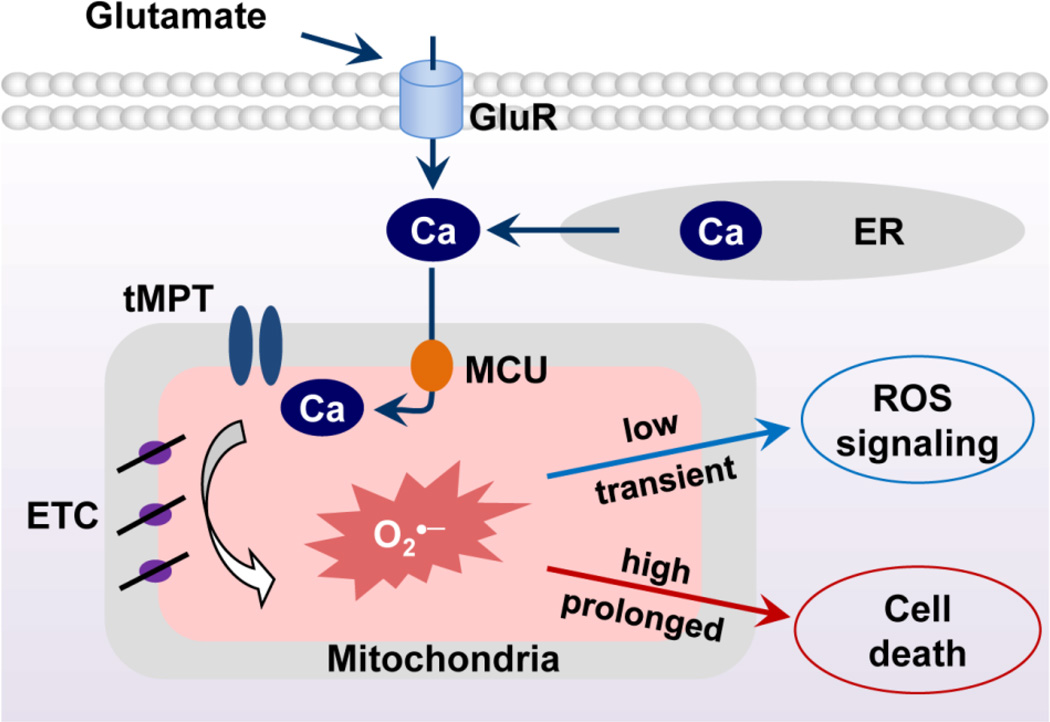

In this study, we developed an approach to monitor single mitochondrial tMPT activity in cultured motor neurons and discovered a novel mechanism mediating glutamate-induced toxicity. The results indicate that glutamate induces cytosolic Ca2+ elevation and promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via MCU. Accumulated mitochondrial Ca2+ triggers tMPT and bursting superoxide production in individual mitochondria. Chronic and high level glutamate treatment causes excessive tMPT and eventually leads to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuron death (Fig. 7). Uncovering tMPT as a new mediator of mitochondrial dysfunction and neuron death may contribute to our understanding of excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative diseases.

Fig. 7.

Schematic model showing the mitochondrial Ca2+-tMPT-superoxide flash pathway that underlies the effects of glutamate in motor neurons. Glutamate elevates cytosolic Ca2+, which promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake to trigger tMPT opening and the bursting superoxide flashes. Under physiological conditions, this pathway is likely transiently activated. Under pathological conditions, chronic or high level of glutamate may significantly activate this pathway and lead to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuron death.

Neuron death is a primary feature of neurodegenerative disease including ALS (Conradi and Ronnevi, 1993). The underlying mechanism of neuron death is complicated and not fully understood. In most neurons, including NSC34 cells, glutamate-induced toxicity can occur via either an excitotoxic mechanism or an oxotoxic mechanism, which involves cysteine uptake and reduced glutathione production. Since the undifferentiated NSC34 cells do not show increased superoxide flashes upon exposure to glutamate, excitotoxicity rather than oxotoxicity may play a critical role in glutamate-induced NSC34D cell dysfunction. The importance of excitotoxicity has been shown by other reports (Plaitakis and Caroscio, 1987; Rothstein et al., 1992; Rothstein et al., 1990). In fact, the effective compounds for ALS, including riluzole (Lacomblez et al., 1996; Meininger et al., 1997) and ceftriaxone (Berry et al., 2013; Rothstein et al., 2005), inhibit glutamate signaling at the agonist and receptor level, respectively. However, these drugs may also block physiological or basal glutamate signaling, which may hamper the normal functioning of neurons. In this regard, results of this study provide a novel mediator, tMPT, in the signaling pathways of glutamate, which is downstream of MCU-mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. The data suggest that preventing excessive tMPT could be a more effective and specific approach for excitotoxicity-related neurodegeneration (Martin, 2010; Parone et al., 2013).

Current wisdom agrees on increased cytosolic Ca2+ as a major downstream event in glutamate-induced toxicity (Eggett et al., 2000; Pivovarova and Andrews, 2010). However, how the glutamate-induced Ca2+ elevation leads to neuron death is elusive (Eggett et al., 2000). Recent studies have indicated that mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake may be involved (Duan et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2013; Stout et al., 1998). Results from this study suggest two key events downstream of glutamate receptor activation, Ca2+ influx and MCU mediated mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. First, Ca2+ influx through cell membrane is largely responsible for elevated cytosolic Ca2+ and superoxide flash activity, which is in line with previous studies showing Ca2+ influx rather than Ca2+ release from intracellular storage underlies glutamate-induced Ca2+ elevation (Duchen, 2012). Second, Ca2+ influx induced by Ca2+ ionophore effectively elevates cytosolic Ca2+, mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and superoxide flash activity. Furthermore, blockade of MCU (Baughman et al., 2011) abolishes glutamate-stimulated tMPT and superoxide flash activity. Collectively, these results further delineate the sequential events downstream of glutamate receptor activation and support that MCU could be a novel target in excitotoxicity (Qiu et al., 2013).

It should be noted that, since the superoxide indicator, cpYFP is also sensitive to pH, concerns have been raised to whether flashes are superoxide or pH in origin (Huang et al., 2011; Muller, 2009; Schwarzlander et al., 2012). In addition, glutamate has been shown to cause intracellular acidification in hippocampal neurons due to mitochondrial calcium uptake and uncouple metabolism (Wang et al., 1994), which may lead to alkalization of the mitochondrial matrix. We have recently shown that, while the majority of cpYFP signal during a flash is superoxide, a mild alkalization and a decline in NADH autofluorescence accompany each superoxide flash event (Wei-LaPierre et al., 2013). This strongly supports that increased electron flow and proton pumping through ETC accompany the flashes. Despite debates over the signals detected during flash, agreement has been reached over the trigger of flash by a sudden increase of the inner membrane permeability that is reflected by loss of membrane potential. In this reports, we further show that mitochondrial Ca2+ is an essential regulator of flash events, consistent with the modulation of tMPT by matrix Ca2+.

Recently, tMPT and superoxide flashes have been shown to participate in neural progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation (Hou et al., 2014; Hou et al., 2013b; Hou et al., 2012). Here, we further show that tMPT, if activated excessively, could be detrimental to the differentiated motor neurons. Since flash activity is increased right after glutamate treatment and up to 24 hr, while oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death are observed at 24 hr, it is likely that increased superoxide flash may contribute to a gradual buildup of oxidative stress, which eventually depolarizes mitochondria and induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death. In addition, flash frequency is diminished at 48 hr after glutamate treatment, suggesting mitochondrial respiration is impaired or the pore is permanently opened at this late stage. Therefore, mitochondrion is not only the receiver and executor but also the target of excessive glutamate-induced toxicity. How and when this dissociation of flash activity and oxidative stress happens and whether a critical checkpoint exists during this transition are interesting questions for future studies.

In conclusion, we discover an intracellular signaling pathway centered on mitochondria that mediates glutamate-induced toxicity in neuron-like cells. Real time monitoring of single mitochondrial tMPT and ROS production events provide a unique approach to investigate the role of mitochondria in live cells. The spatiotemporal regulation of single mitochondrial tMPT events is an initial response of motor neurons to glutamate, which overtime causes oxidative neuron death. Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake via MCU critically regulates tMPT activity. Targeting tMPT and its regulators, such as MCU and tMPT blockers, may effectively ameliorate excitotoxicity.

Research Highlights.

Glutamate elevates cytosolic Ca2+ in NSC34D cells mainly through Ca2+ influx.

Glutamate-induced mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake through MCU.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ triggers transient permeability transition pore (tMPT) opening.

tMPT is coupled to bursting superoxide production in NSC34D cells.

Prolonged activation of tMPT leads to cell death in NSC34D motor neuron-like cells.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant HL114760 (W.W.). We thank Dr. Neil Cashman (University of British Columbia) for kindly providing NSC34 cells. We thank Dr. John F. Engelhardt (University of Iowa) for providing Adv-SOD2 vector.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- Adam-Vizi V, Starkov AA. Calcium and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation: how to read the facts. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(Suppl 2):S413–S426. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN. Recent advances in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:397–405. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200008000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azbill RD, Mu X, Springer JE. Riluzole increases high-affinity glutamate uptake in rat spinal cord synaptosomes. Brain Res. 2000;871:175–180. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, Belcher-Timme CA, Sancak Y, Bao XR, Strittmatter L, Goldberger O, Bogorad RL, Koteliansky V, Mootha VK. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JD, Shefner JM, Conwit R, Schoenfeld D, Keroack M, Felsenstein D, Krivickas L, David WS, Vriesendorp F, Pestronk A, Caress JB, Katz J, Simpson E, Rosenfeld J, Pascuzzi R, Glass J, Rezania K, Rothstein JD, Greenblatt DJ, Cudkowicz ME. Design and initial results of a multi-phase randomized trial of ceftriaxone in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–C833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW. Methods for antagonizing glutamate neurotoxicity. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:105–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradi S, Ronnevi LO. Selective vulnerability of alpha motor neurons in ALS: relation to autoantibodies toward acetylcholinesterase (AChE) in ALS patients. Brain Res Bull. 1993;30:369–371. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90267-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani D, Raffaello A, Teardo E, Szabo I, Rizzuto R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong XX, Wang Y, Qin ZH. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009;30:379–387. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y, Gross RA, Sheu SS. Ca2+-dependent generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species serves as a signal for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 activation during glutamate excitotoxicity. J Physiol. 2007;585:741–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR. Mitochondria, calcium-dependent neuronal death and neurodegenerative disease. Pflugers Arch. 2012;464:111–121. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1112-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggett CJ, Crosier S, Manning P, Cookson MR, Menzies FM, McNeil CJ, Shaw PJ. Development and characterisation of a glutamate-sensitive motor neurone cell line. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1895–1902. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod JW, Molkentin JD. Physiologic functions of cyclophilin D and the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Circ J. 2013;77:1111–1122. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Chen M, Ding Y, Shang W, Xu J, Zhang X, Zhang W, Li K, Xiao Y, Gao F, Shang S, Li JC, Tian XL, Wang SQ, Zhou J, Weisleder N, Ma J, Ouyang K, Chen J, Wang X, Zheng M, Wang W, Cheng H. Imaging superoxide flash and metabolism-coupled mitochondrial permeability transition in living animals. Cell Res. 2011;21:1295–1304. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feissner RF, Skalska J, Gaum WE, Sheu SS. Crosstalk signaling between mitochondrial Ca2+ and ROS. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2009;14:1197–1218. doi: 10.2741/3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths EJ, Rutter GA. Mitochondrial calcium as a key regulator of mitochondrial ATP production in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:1324–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Zhang X, Xu J, Jian C, Huang Z, Ye T, Hu K, Zheng M, Gao F, Wang X, Cheng H. Synergistic triggering of superoxide flashes by mitochondrial Ca2+ uniport and basal reactive oxygen species elevation. J Biol Chem. 2013a;288:4602–4612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.398297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Ghosh P, Wan R, Ouyang X, Cheng H, Mattson MP, Cheng A. Permeability transition pore-mediated mitochondrial superoxide flashes mediate an early inhibitory effect of amyloid beta1–42 on neural progenitor cell proliferation. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:975–989. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Mattson MP, Cheng A. Permeability Transition Pore-Mediated Mitochondrial Superoxide Flashes Regulate Cortical Neural Progenitor Differentiation. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e76721. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Ouyang X, Wan R, Cheng H, Mattson MP, Cheng A. Mitochondrial superoxide production negatively regulates neural progenitor proliferation and cerebral cortical development. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2535–2547. doi: 10.1002/stem.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Zhang W, Fang H, Zheng M, Wang X, Xu J, Cheng H, Gong G, Wang W, Dirksen RT, Sheu SS. Response to "A critical evaluation of cpYFP as a probe for superoxide". Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1937–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichas F, Jouaville LS, Mazat JP. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell. 1997;89:1145–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomblez L, Bensimon G, Leigh PN, Guillet P, Meininger V. Dose-ranging study of riluzole in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Riluzole Study Group II. Lancet. 1996;347:1425–1431. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AY, Mathur R, Mei N, Langhammer CG, Babiarz B, Firestein BL. Neuroprotective drug riluzole amplifies the heat shock factor 1 (HSF1)- and glutamate transporter 1 (GLT1)-dependent cytoprotective mechanisms for neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:2785–2794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.158220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manev H, Favaron M, Guidotti A, Costa E. Delayed increase of Ca2+ influx elicited by glutamate: role in neuronal death. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a molecular target for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:186–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ. Biology of mitochondria in neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2012;107:355–415. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385883-2.00005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta A, Prabhakar M, Kumar P, Deshmukh R, Sharma PL. Excitotoxicity: bridge to various triggers in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;698:6–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger V, Dib M, Aubin F, Jourdain G, Zeisser P. The Riluzole Early Access Programme: descriptive analysis of 844 patients in France. ALS/Riluzole Study Group III. J Neurol. 1997;244(Suppl 2):S22–S25. doi: 10.1007/BF03160577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum BS. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the brain: review of physiology and pathology. J Nutr. 2000;130:1007S–1015S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1007S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller FL. A critical evaluation of cpYFP as a probe for superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:1779–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SN, Miller RJ. Two distinct quisqualate receptors regulate Ca2+ homeostasis in hippocampal neurons in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;35:671–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG. Mitochondrial calcium function and dysfunction in the central nervous system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:1416–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Perry G, Aliev G, Hirai K, Takeda A, Balraj EK, Jones PK, Ghanbari H, Wataya T, Shimohama S, Chiba S, Atwood CS, Petersen RB, Smith MA. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:759–767. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parone PA, Da Cruz S, Han JS, McAlonis-Downes M, Vetto AP, Lee SK, Tseng E, Cleveland DW. Enhancing mitochondrial calcium buffering capacity reduces aggregation of misfolded SOD1 and motor neuron cell death without extending survival in mouse models of inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2013;33:4657–4671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1119-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilli V, Miotto G, Canton M, Brini M, Colonna R, Bernardi P, Di Lisa F. Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys J. 1999;76:725–734. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivovarova NB, Andrews SB. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial function and dysfunction in neurons. FEBS J. 2010;277:3622–3636. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaitakis A, Caroscio JT. Abnormal glutamate metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:575–579. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Tan YW, Hagenston AM, Martel MA, Kneisel N, Skehel PA, Wyllie DJ, Bading H, Hardingham GE. Mitochondrial calcium uniporter Mcu controls excitotoxicity and is transcriptionally repressed by neuroprotective nuclear calcium signals. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2034. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD. Therapeutic horizons for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:679–687. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW. Decreased glutamate transport by the brain and spinal cord in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1464–1468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199205283262204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE, Jin L, Dykes Hoberg M, Vidensky S, Chung DS, Toan SV, Bruijn LI, Su ZZ, Gupta P, Fisher PB. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–77. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Tsai G, Kuncl RW, Clawson L, Cornblath DR, Drachman DB, Pestronk A, Stauch BL, Coyle JT. Abnormal excitatory amino acid metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:18–25. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzlander M, Murphy MP, Duchen MR, Logan DC, Fricker MD, Halestrap AP, Muller FL, Rizzuto R, Dick TP, Meyer AJ, Sweetlove LJ. Mitochondrial 'flashes': a radical concept repHined. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen EZ, Song CQ, Lin Y, Zhang WH, Su PF, Liu WY, Zhang P, Xu J, Lin N, Zhan C, Wang X, Shyr Y, Cheng H, Dong MQ. Mitoflash frequency in early adulthood predicts lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EP, Yen AA, Appel SH. Oxidative Stress: a common denominator in the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:730–736. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout AK, Raphael HM, Kanterewicz BI, Klann E, Reynolds IJ. Glutamate-induced neuron death requires mitochondrial calcium uptake. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:366–373. doi: 10.1038/1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MR, Hardiman O, Benatar M, Brooks BR, Chio A, de Carvalho M, Ince PG, Lin C, Miller RG, Mitsumoto H, Nicholson G, Ravits J, Shaw PJ, Swash M, Talbot K, Traynor BJ, Van den Berg LH, Veldink JH, Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Controversies and priorities in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:310–322. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70036-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vay L, Hernandez-SanMiguel E, Lobaton CD, Moreno A, Montero M, Alvarez J. Mitochondrial free [Ca2+] levels and the permeability transition. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GJ, Randall RD, Thayer SA. Glutamate-induced intracellular acidification of cultured hippocampal neurons demonstrates altered energy metabolism resulting from Ca2+ loads. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2563–2569. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Fang H, Groom L, Cheng A, Zhang W, Liu J, Wang X, Li K, Han P, Zheng M, Yin J, Mattson MP, Kao JP, Lakatta EG, Sheu SS, Ouyang K, Chen J, Dirksen RT, Cheng H. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell. 2008;134:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei-LaPierre L, Gong G, Gerstner BJ, Ducreux S, Yule DI, Pouvreau S, Wang X, Sheu SS, Cheng H, Dirksen RT, Wang W. Respective contribution of mitochondrial superoxide and pH to mitochondria-targeted circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (mt-cpYFP) flash activity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10567–10577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwacka RM, Dudus L, Epperly MW, Greenberger JS, Engelhardt JF. Redox gene therapy protects human IB-3 lung epithelial cells against ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis. Hum Gene Ther. 1998a;9:1381–1386. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.9-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwacka RM, Zhou W, Zhang Y, Darby CJ, Dudus L, Halldorson J, Oberley L, Engelhardt JF, et al. Redox gene therapy for ischemia/reperfusion injury of the liver reduces AP1 and NF-kappaB activation. Nat Med. 1998b;4:698–704. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]