Abstract

The microenvironment formed by surface active compounds is being recognized as the active site of lipid oxidation. Trace amounts of water occupy the core of micro micelles and several amphiphilic minor components (e.g., phospholipids, monoacylglycerols, free fatty acids, etc.) act as surfactants and affect lipid oxidation in a complex fashion dependent on the structure and stability of the microemulsions in a continuous lipid phase such as bulk oil. The structures of the triacylglycerols and other lipid-soluble molecules affect their organization and play important roles during the course of the oxidation reactions. Antioxidant head groups, variably located near the water-oil colloidal interfaces, trap and scavenge radicals according to their location and concentration. According to this scenario, antioxidants inhibit lipid oxidation not only by scavenging radicals via hydrogen donation but also by physically stabilizing the micelles at the microenvironments of the reaction sites. There is a cut-off effect (optimum value) governing the inhibitory effects of antioxidants depending inter alias on their hydrophilic/lipophilic balance and their concentrations. These complex effects, previously considered as paradoxes in antioxidants research, are now better explained by the supramolecular chemistry of lipid oxidation and antioxidants, which is discussed in this review.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Amphiphilic compounds, Bulk oils, Critical micelle concentration, Lipid oxidation

Introduction

Unsaturated fatty acids play important roles as food components and nutrients, and contribute to food's stability and sensory properties such as texture and flavor 1–3. Specifically, the highly unsaturated omega-3 fatty acids of fish lipids undergo instantaneous oxidation, which limits their shelf-lives and restricts their applications as health promoting fatty acids in the diet 4–8. Attempts have continuously been made to find ways to protect unsaturated fatty acids from oxidative deterioration but no satisfactory solutions have been found 9.

Lipid oxidation is known to occur in three phases: initiation, propagation, and termination 4,9,10. The theory that was developed in the 1940s 11 about the autocatalysis of lipid oxidation by-produced hydroperoxides (LOOH) is largely acceptable and provides logical description of the chemical reactions involved in the oxidative changes of fatty acids during the propagation and termination periods 6,12–14 as well as the products of oxidation and their significance especially as off-flavor compounds 3,6,15–17. The hydroperoxide theory outlined by Farmer et al. 11 provides a general description of the role of antioxidants in inhibiting lipid oxidation. However, this description is often not precise and sometimes suffers from inconsistencies and paradoxical outcomes when it comes to certain details 1,3,18–20. Knowledge that was accumulated during the last two decades emphasize that lipid oxidation cannot be explained merely by chemical reactions but also by considering molecular positions in space, especially at the interfaces of nanoemulsions. This paper reviews the current knowledge of lipid oxidation with emphasis on the effects of antioxidants and the physical microenvironments on the oxidation of bulk oils. Bulk oils are considered as water-in-oil nanoemulsions rather than pure lipid phases.

Antioxidants and their mechanisms

An antioxidant is defined as “Any substance that, when present at low concentrations compared with those of an oxidizable substrate, delays or prevents the oxidation of that substrate” 21. Two kinds of antioxidants, primary and secondary antioxidants, have been classified based on their mechanisms of action in inhibiting lipid oxidation reaction 6,20,22.

Primary antioxidants (mainly phenolic compounds)

They react with lipid hydroperoxyl radicals producing lipid hydroperoxides and more stable, low energy, antioxidant radicals (Aglyph6) 22,23, which are significantly much less reactive in propagation reactions 19. By acting as hydrogen donors or radicals scavengers, primary antioxidants prolong the IP and delay the propagation period 3,22. Primary antioxidants (e.g., BHA, BHT, TBHQ, tocopherols, and flavonoids) are generally mono- or polyhydroxy phenols with hydrogen-donating substitutions on the ring 6,19,24. It is currently believed that the most important factor governing the antioxidant potency of phenolic compounds relates to their hydrogen donating powers, that is, to the number of O−H groups in ortho and para positions, their bond dissociation enthalphies (BDE), and whether these phenolic hydrogens are hydrogen bonded 4,14,25. Some primary antioxidants, called multiple-function antioxidants, combine more than one of the following antioxidant functionalities; free radical scavenging, oxygen sequestering, metal chelation, and light energy absorption. Examples of these antioxidants include propyl gallate, proanthocyanidins, and ascorbic acid 14.

Secondary antioxidants (or retarders)

These are preventive antioxidants that enhance the inhibitory activity of primary antioxidants. This class of antioxidants includes sequestrants or chelating agents (e.g., phytic acid, EDTA, and citric acid), oxygen scavengers, and reducing agents (e.g., ascorbates), and other factors whose effect is not completely explained (e.g., amino acids and phospholipids) 6,19. The exact mechanism of action of the wide variety of secondary antioxidants have not been properly understood but some of their speculated activities include chelating prooxidants or catalysts, providing hydrogen to primary antioxidants, decomposing LOOH to nonradical species, scavenging ground state and singlet oxygens, and absorbing UV light 22. It has been debated by Brimberg 26,27 that the role of these retarders relies on their effects on micellization but unfortunately this work has not been noticed in time.

Combinations of primary and secondary antioxidants are often found more effective in retarding lipid oxidation than the sum of their single actions 1,3,28. It was shown that the synergism between these two classes of antioxidants effectively increases the length of the IP and reduces reaction rates 13,29. This synergism has been shown, for example, between tocopherols and ascorbic acid and between mixtures of natural tocopherols and citric acid 19. A good method to evaluate the efficiency of inhibitors and retarders, according to which the “antioxidant” efficacy can be measured by considering the length of the IP as well as the rate of oxidation during the IP was presented by Yanishlieva and Marinova [29 and references cited therein]. Three descriptive parameters are considered:

Effectiveness, which is the ability of an antioxidant to inhibit the oxidation chain reaction by donating hydrogens and inactivating RO2• during the IP. Effectiveness is measured by stabilization factor, F = IPinh/IPo, where IPinh is the IP of an inhibited oxidation (with an antioxidant), and IPo is the IP of the uninhibited oxidation (no antioxidant present).

Strength, which is the inverse measure of the participation of an antioxidant in the side reactions that may results in the change of oxidation rate during the IP. The oxidation rate ratio ORR = Winh/Wo, where Winh is the rate of oxidation of an inhibited oxidation (with an antioxidant) and Wo is the rate of oxidation of an uninhibited oxidation (no antioxidant present) is an inverse measure of strength, ORR > 1 indicates that an antioxidant causes a faster oxidation rate than the rate without antioxidant.

Antioxidant activity (A = F/ORR), which indicates the capability of an antioxidant in terminating autoxidation chain and in affecting the rate of oxidation during IP 13,29.

Until recently, most of the explanations given for observed synergistic interactions have been based mainly on unfounded assumptions related to possible chemical interferences of primary and secondary antioxidants. The addition of primary antioxidant and synergists often increase the IP and decrease the rate of oxidation during the IP (Winh), for example, the inhibition of autoxidation of fish oil at 20°C by 1000 ppm ascorbyl palmitate and 5 ppm lecithin 28 (Fig. 1) of fish oil at 20°C with 500 ppm ascorbyl palmitate and 2000 ppm lecithin 30, of soybean oil at 110°C with 4000 ppm α-tocopherol and 15 000 ppm phospholipids 31, and of peanut oil at 110°C with 1000 ppm α-tocopherol and 1500 ppm phospholipids 32. Some indogenous minor components in refined bulk oils, such as phospholipids, can act as synergists to tocopherols and contribute to protecting the oils against oxidation while others, such as monoacylglycerols, may act as prooxidants and decrease the IP and/or increase the rate of oxidation during the IP 8,14,20,33–35. Besides synergism, there are more examples of unexplained phenomena related to reaction rates of inhibited oxidations. One permanent case is the loss of antioxidant efficacy with increased primary antioxidant concentration 4,25, which is well known, for example, α-tocopherol 18. The concept of side reactions was used to account for such paradoxical outcomes of antioxidants such as the loss of efficiency at increased concentrations [9 and references cited therein].

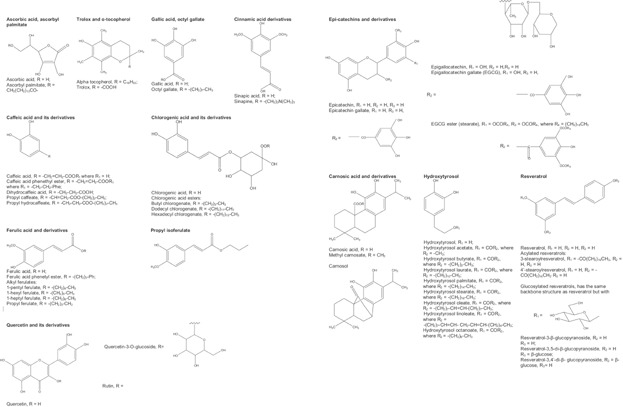

Figure 1.

Structures of antioxidants with different polarity discussed in this paper.

The polar paradox and interfacial phenomena

It is clear from the previous section that the pure chemical model failed to adequately describe the effects of primary and secondary antioxidants on the rates of lipid oxidation reactions and their synergistic interactions. Knowledge has gradually developed to strongly suggest that effects related to molecular orientation and self-assembly of different molecular species are important and can help explain phenomena that are not yet well understood. The historical developments in the understanding of the role of physical location of lipid-soluble components on lipid oxidation are presented in (Table1).

Table 1.

Historical developments in the understanding of the physical effects of components and additives on lipid oxidation in bulk oils

| References | Observations | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Porter 36,37 and Porter et al. 38 | The general rule of the polar paradox was proposed and confirmed stating that polar antioxidants (e.g., propyl gallate, tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), and Trolox C) are more effective in food systems with low surface-to-volume ratio or nonpolar lipids such as bulk vegetable oils while nonpolar antioxidants (e.g., BHA, BHT, and α-tocopherol) work better in foods with high surface-to-volume ratio or polar lipid emulsion such as o/w emulsion | The antioxidant activity is oppositely related to the polarity of antioxidants in relation to food lipids |

| Brimberg 26,27 | Lipid hydroperoxides (LOOH) are surface-active agents that form micelles at above their critical micelle concentration (CMC). O2 is maximumly solubilized in lipids when hydroperoxide CMC is attained | Micelles formed by hydroperoxides are the site of lipid oxidation reaction |

| Frankel et al. 39–41 | The interfacial phenomenon was proposed to explain the polar paradox. Lipophilic antioxidants (e.g., α-tocopherol and ascorbyl palmitate) were more effective in o/w emulsion system than in bulk oil because they had more affinities toward water-oil interface, while the opposite was true for hydrophilic antioxidants (Trolox, ascorbic acid, rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid, and rosemary extract), which were more oriented in air-oil interfaces in bulk oil. Mixtures of α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid were more active in bulk oils than in o/w emulsions | Interfacial phenomenon is related to the kinds of interfaces at which the antioxidants are more oriented, which may explain the polar paradox |

| Koga and Terao 54 | In the aqueous microenvironments in bulk lipids (15:85 by mol/mol mixture of methyl linoleate and methyl laurate), phospholipid aggregates enhanced the accessibility of α-tocopherol to radicals and hence the interruption of chain initiation. The polar OH group of α-tocopherol is located not too deeply in hydrophobic region of phospholipid bilayer membrane but just near by the membrane surface | Interfacial microenvironment is the place where interactions among surfactants, antioxidants, and radicals take place |

| Huang et al. 60 | Linoleic acid competed with Trolox for Tween 20 in the polar region of the micelles and at the o/w interface. Trolox diffused in the water phase and the mixed micelles and thus was a better antioxidant than α-tocopherol that was diffused in the oil phase | Micelle is where the oxidation and interactions of antioxidants and surfactants take place |

| Carlotti et al. 123 | An emulsion was known to contain micellar structure. l-tryptophan was a very effective synergist with α-tocopherol because it was distributed in the micellar core or in the o/w interface | Micelle core and interface have different roles in autoxidation |

| Endo et al. 106,116,118 | A mixture of trieicosapentaenoylglycerol and tripalmitoylglycerol (2:1, mol/mol) was most susceptible to oxidation than other ratios. The triacylglycerol (TAG) structure affected the oxidation rate of unsaturated fatty acids. TAGs with unsaturated fatty acids at sn-2 positions were more stable than those having unsaturated fatty acids at sn-1 and sn-3 positions | Physical structures, such as the position of fatty acids on TAG, have an effect on lipid oxidation |

| Hamilton et al. 28 | Lecithin solubilizes ascorbyl palmitate and enhances its physical interactions with α-tocopherol which form reversed micelles. This versatile network had an ability to interrupt free-radical propagation by inhibiting the participation of ascorbyl radical in promoting LOOH scission | Reversed micelles are formed in w/o emulsions |

| Frankel and Meyer 124 | The effectiveness of antioxidants in a system is influenced by several factors including the partitioning behavior of antioxidants between lipid and aqueous phase, the oxidation conditions, and the physical state of the oxidizable substrate. Surface-active substances influence the interfacial interactions between the system and antioxidant. The oil-water partition coefficients influence the distribution of relatively polar antioxidants in the lipid and aqueous phase of a food emulsion. Trolox, which is very polar, works very well in bulk oil and is more effective in o/w emulsions of linoleic acid compared to those of TAG. Unlike TAG, linoleic acid is more polar and forms micelles in aqueous system. Micelle-forming substrates enhance the activity of hydrophilic and polar antioxidant | O/w partition coefficient can explain the affinity of a compound in lipid and aqueous phase |

| Khan and Shahidi 84 | The synergistic interactions of tocopherols and phospholipids in borage and evening primrose TAG can be explained partly by phosphatidylcholine increasing the accessibility of α-tocopherol in the aqueous microenvironment where the induction of lipid oxidation occurs | Phospholipid synergists support antioxidants by modifying the reaction environment |

| Schwarz et al. 43 | Antioxidants (Trolox, propyl gallate, gallic acid, methyl carnosoate, and carnosic acid) had either moderate or higher activity in bulk oil than in emulsions. The most polar antioxidants (propyl gallate and gallic acid) exhibited either prooxidant or no antioxidant activity in polar medium (i.e., o/w emulsions). Emulsifiers (Cetheareth-15, glyceryl stearate, and polyglyceryl glucose methyl distearate) form lamellar structure in bulk oil causing a higher solubilization of polar antioxidants in nonpolar medium. Antioxidant actions in bulk oil, except gallic acid which was not influenced by polysiloxan polyalcohol polyether copolymer, are enhanced by emulsifiers including α-tocopherol | The activity of antioxidants can be enhanced or reduced by emulsifiers. Mesophase structures depend on molecular structure and critical packing parameter (CPP) of the compound |

| Gupta et al. 87 | Inverse micellar structures (∼60 Å in diameter) were formed by phospholipids in a hexane-oil mixtures containing <0.3% water. The principal domains of the phase behavior include micellar solution, two phase dispersion, and dense micellar solution. A smooth transition to dense micellar phase was observed with increased phospholipids concentration. Dynamic light scattering measurements showed that aggregate sizes were affected by the amount of phospholipids and >1.5% water, below which the available water is very limited to significantly affect core sizes | Reversed micelles are formed in w/o nanoemulsions. The size of aggregates depends on the amount of surfactants and water |

| Kortenska et al. 81 | Polar products of lipid oxidation with oxygen containing groups (e.g., LOOH, fatty alcohols, acids, and water) tend to associate in non-polar media to form complexes and aggregates. Fatty alcohols may play a role as an initiation of formation of these aggregates and hence influence lipid oxidation rate | Polar products of lipid oxidation affect the oxidation rate by modulating the reaction environment |

| Kortenska et al. 68 | Relatively high concentrations of polar compounds (e.g., LOOH, lipid peroxyl radical [LOO•], and BHT) form microaggregate (micelles) in the presence of fatty alcohols. This leads to an increase of the rate of termination and causes a decrease in the efficiency of BHT to protect purified sunflower oil (SFO) as LOOH decompose faster inside the polar interior of the micro aggregate | Fatty alcohols or BHT might act as surfactants and form microaggregates (micelles) in the w/o system |

| Velasco and Dobarganes 12 | Cloudy OO was more oxidatively stable than filtered OO. Suspended and dispersed materials in cloudy olive oil (OO) play a physical stabilization role by acting as antioxidants and/or as a buffer and preventing acidity increases | Polar constituents in oils, for example, unsaponifiable materials, may play a physical role in oil solubilization |

| Brimberg and Kamal-Eldin 125 | LOOH formed during methyl linoleate oxidation are surface-active and can form micelles. When LOOH concentration reaches CMC, lipid oxidation enters the propagation period | CMC of hydroperoxides marks the beginning of propagation period |

| Brimberg and Kamal-Eldin 55 | The amount of oxygen solubilized in lipid is comparative to the number of micelles formed during oxidation. When lipid medium has conjugated double bonds is oxidized, no hydroperoxides are formed but instead cyclic peroxides that are not surface-active and do not form micelles, hence there is no propagation period | Organic peroxides (not hydroperoxides) are not surface active and do not atfect the oxidation rate |

| El-Shattory et al. 69 | Reversed micelles were formed with surfactant aggregates in organic solvents, for example, LOOH, methylglucose dioleate, polyglyceryl-3-oleate, and lecithin | Reversed micelles are formed in organic system in the presence of surfactants |

| Kiokias and Gordon 71 | The activity of norbixin as antioxidant in bulk oil is consistent with the polar paradox. Norbixin is soluble in water as aggregates and is probably oriented at the oil-water interface in the emulsion due to its massive hydrocarbon backbone but it is insoluble in oil | Norbixin is an example to supports the polar paradox |

| Decker et al. 72 | Differences in the effectiveness of the antioxidants in oil systems are mainly due to their physical location in the system, namely the antioxidant paradox. Polar (hydrophilic) antioxidants are more effective in bulk oil because they can accumulate at the air-oil interface or in reversed micelles within the oil, where lipid oxidation occurs. On the other hand, nonpolar (lipophilic) antioxidants are more effective in o/w emulsions because they accumulate in the oil droplets and/or may accumulate at the oil-water interface, where interactions between LOOH at the droplet surface and pro-oxidants (e.g., transition metals) take place | Antioxidant effectiveness depends on how and where they are partitioned in the system. In bulk oil, lipid oxidation occurs at the air-oil interface as well as in the reversed micelle (oil-water) interface |

| Calligaris and Nicoli 126 | Salts with the antichaotropic anionic species were able to form weak bonds may form a “hydrophilic” structure around them and inhibit the solubility of other substances with lower polarities. Thus, these salts may enhance the activity of certain antioxidants | Hydrophobic structure formed by the salts might salt-out amphiphilic molecules and affect lipid oxidation |

| Becker et al. 44 | Antioxidant activity in bulk oil was related to the polarity of the antioxidants, within the order: quercetin >α-tocopherol ≫ astaxanthin = rutin. Rutin was an exception in that it is relatively hydrophilic but had the lowest activity in bulk oil. This indicated that it is not only the polarity that govern the effectiveness of antioxidants. Poor solubility of rutin in bulk oil or degradation of its glycoside at high temperature also influenced its effects | Hydrophilicity (or lipophilicity) do not always correlate with the antioxidant effectiveness in bulk oil |

| Chaiyasit et al. 14 | Edible oils contain polar lipids (e.g., monoacylglycerol (MAG), diacylglycerol (DAG), free fatty acid (FFA), phospholipids, sterols, cholesterols, phenolic compounds, aldehydes, and ketones), which have amphiphilic nature. Components with especially low HLB can self-assemble due to hydrophobic interactions and form association colloids, including lamellar structures and reversed micelles. These surface active molecules partition at the o/w interface and induce the concentration of antioxidants at the surface of colloids, thus increasing interactions between antioxidants and/or prooxidants with metal at the interface or water core | The term association colloids, include geometric forms such as lamellar structures and reversed micelles, which are formed by surfactants was proposed |

| Chaiyasit et al. 33 | Edible oils contain surface-active compounds and water that can form physical structures such as reversed micelles. Both phosphatidylcholine and oleic acid were suggested to be located at the o/w interface by 5-dodecanoylaminofluorescein probe measurement, and phosphatidylcholine was found to increase the accessibility of α-tocopherol to radicals while oleic acid acted as prooxidants | More examples on the effects of surface-active compounds and reversed micelles on lipid oxidation were presented |

| Kasaikina et al. 70 | LOOH do not form classical micelles but form associates (1–500 nm in size) alongside water, surfactants, alcohols, acids, ketones, and other oxidation products. LOOH is amphiphilic and concentrates on the boundary of micelle and water. In a natural olefin (limonene), cationic surfactant promotes oxidation, whereas anionic and nonionic surfactants did not have any influence | Associates rather than micelles were suggested. Charges of surfactants affect the role of the surfactants as antioxidant or prooxidant |

| Koprivnjak et al. 73 | Bipolar molecules such as lecithin form reversed micelle where their polar groups are pointed toward the interior and their nonpolar tails are directed toward the exterior (oil). Lecithin ability to increase oxidative stability was due to its bipolar character and its ability to entrap hydrophilic antioxidants to concentrate on the micellar interface | On the role of phospholipids as stabilizers of reversed micelles |

| Laguerre et al. 17 | Not all nonpolar antioxidants behave as antioxidant in polar medium; the antioxidant capacity of homologous series of chlorogenic acid esters in o/w emulsions increased as the alkyl chain length increased until dodecyl chain. Further chain extension caused a drastic drop of antioxidant capacity (a cut-off effect) | The Polar Paradox is not linear. As the alkyl chain length increase, the hydrophilicity and the antioxidant activity in o/w emulsions increase to a certain extent, but further increase reduces the antioxidant activity (a cut-off effect) |

| Belhaj et al. 103 | The size of nanoemulsions was influenced by the pressure, oil composition, and the surface-active properties of surfactants. Changes of α-tocopherol antioxidative effect in bulk oil was more significant than that in emulsions | The importance of nanoemulsions in lipid oxidation was proposed |

| Bendini et al. 127 | When virgin OO was subjected to temperature close to 0°C, changes in the physical state happened leading to destabilization of the microdroplets of water and the concentration of polar phenolic compounds and finally the lost of antioxidant activity | At lower temperatures (close to 0°C), destabilized microdroplets in bulk oils may accelerate the rate of lipid oxidation |

| Chen et al. 7 | When the phospholipid concentration exceeds their CMC, reversed micelles were formed. Dioleoylphosphatidylcholine and water formed spherical association colloids in SBO, and they were prooxidative because more (small) non-scattering association colloids were formed. 1,2-dibutyryl-sn-glycero-3-phoshocholineformed cylindrical structures and had no impact on oxidation rates | As amount of surfactant increased, CMC was affected and so the formation of reversed micelle. The kinds of physical structures affect oxidation differently. Spherical shapes of association colloids were prooxidants, while cylindrical shapes had no impact on oxidation rates |

| Gramza-Michalowska and Stachowiak 128 | Astaxanthin causes no protection of bulk oils, which indicates that antioxidant activity was correlated with its polarity. Astaxanthin is hydrophobic, it is located in the oil not at the air-oil interface protecting o/w emulsions but not bulk oils and liposome | Lipophilic compounds do not affect the oxidation in bulk oils |

| Kasaikina et al. 86 | Primary amphiphilic products of the oxidation of LOOH and lipids, and cationic surfactants form mixed micelles, which accelerated the decomposition of LOOH and other polar components (e.g., metal-containing compounds, inhibitors etc.) | Mixed micelles with different geometric forms were detected in w/o emulsions that enhance the decomposition of LOOH |

| Medina et al. 104 | The effectiveness of antioxidants relies on its chemical reactivity (as radical scavenger or metal chelator), its interaction with other food components, their concentration and physical location in homogeneous or heterogeneous system. For instance, resveratrol had a low activity in inhibiting lipid autoxidation in w/o emulsions and bulk oil because it has a low incorporation in the droplet interface and its poor solubilty in water, thus probably located far away from the air-oil interface | On the importance of physical effects of antioxidants |

| Chen et al. 7 | Amphiphilic surface active compounds, which exist after oil refining (such as MAG, DAG, phospholipids, sterol, and FFA), interact with water to form association colloids (in the forms of reversed micelles, microemulsions, lamella, and cylindrical aggregates). Increasing water concentration had very little impact on the IP of lipid oxidation (by hexanal) at 55°C. MAG formed ordered lamellar structures in hazelnut oil. Association colloids impact on lipid oxidation depends on the additives ability to form the colloids and how the additives are partitioned in the micelles | Different surfactants form different kinds of mesophase structures that affect lipid oxidation. Water concentration had a limited effect on oxidation at 55°C |

| Chen et al. 20 | Lipid oxidation is not only influenced by the traditional chemical factors, such as lipid compositions, transition metals; but also by the existence of physical structures. Phospholipids formed microstructures known as association colloids within soybean oil (SBO). Reversed micelle of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine shorthened the IP of SBO at 55°C | Physical structures are important affectors of lipid oxidation |

| An et al. 129 | Antioxidative and prooxidative properties are determined by internal factors (i.e., the oxidation substrates, structural organization and the microenvironment for the bioactive compound) and external factors (i.e., heat, pressure, and exposure to light). Hydrophobic alkyl chain increased water insolubility of 7-n-alkoxydaidzeins: daidzein, 7-n-butyloxy-daidzein, 7-n-octyloxy-daidzein, 7-n-dodecyloxy-daidzein, and 7-n-hexadecyloxy-daidzein. Daidzein increased membrane fluidity, but 7-n-butyloxy-daidzein until 7-n-hexadecyloxy-daidzein decreased fluidity. The compounds were suggested to present in the central domain of the liposome bilayer in the order 7-n-dodecyloxy-daidzein > 7-n-octyloxy-daidzein > 7-n-butyloxy-daidzein > 7-n-hexadecyloxy-daidzein > daidzein, leaving 7-n-dodecyloxy-daidzein as the most effective antioxidant, as monitored by fluoresence spectroscopy using a fluorescence probe | Changes in the hydrophilicity of an antioxidant affect its inhibitory activity of lipid oxidation |

| Shahidi and Zhong 53 | In this review, the polar paradox was re-examined. The distribution of polar antioxidants at the oil-air interface was questioned because air is much less polar than oil. Antioxidants action was influenced by various micro- or nanoenvironments (such as lamellar and reversed micelles) which are formed by water, amphiphilic compounds, and oxidation products (e.g., LOOH, aldehydes, and ketones) alter the physical location of antioxidants. The association colloids are the site of lipid oxidation in bulk oil. A cutoff effect was observed, a non-linear phenomenon occurred wherein antioxidant activity increases as the alkyl chain lengthens until a threshold is achieved, then further increased of chain length caused a drastic collapse on activity. Molecular size also influenced antioxidant effectiveness and causing a cutoff effect, antioxidants with bulky structures (e.g., phenolic derivatives with long alkyl chains) have steric hindrance thus lower mobility than those of smaller size, therefore lower diffusibility toward reactive centers | A cut-off effect was found for hydrophilic antioxidant in nonpolar medium |

| Sorensen et al. 61 | W/o emulsion resemble bulk oil, of which water is located in micelles and aqueous phase is surrounded by emulsifier. The efficacy of antioxidants in emulsions of water in omega-3 lipids follow polar paradox hypothesis, but not for the o/w emulsion. In the case of w/o, at pH7, ascorbic acid had negative charges and repulsive forces existed between the interface and ascorbic acid, thus it was located away from the interface. The polar paradox was insufficient to explain antioxidant effects in multiphase systems such as emulsions, as there are interactions between iron, emulsifiers, and antioxidants | W/o emulsions resemble bulk oils in their response to the polarity of compounds |

| Sun et al. 23 | Polar antioxidants with higher affinity were known to concentrate on oil/air or oil/water interface of the reversed micelle. Thus the antioxidant polar paradox does not always prevail, as some research found different results. Thus the influencing factors of antioxidant activity in reversed micelle were not solely based on antioxidant polarity | Polar paradox is affected by other factors contributing to non-linearity in the effect of antioxidants in lipid oxidation |

| Sun-Waterhouse et al. 74 | Caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid are hydrophilic. They tend to partition into the water phase, locate outside of the oil droplets and chelate metal ions which exist in the oils. Both antioxidants stabilized oil against autoxidation but facilitated the hydrolysis of TAG in the oils | Antioxidants may cause other adverse effects, for example, hydrolysis of TAG |

| Chen et al. 34 | Soybean oil is found in seeds inside micro-sized oil bodies, which consist of a central neutral lipid core (94–98% w/w) and is surrounded by phospholipids monolayer (0.5–2% w/w) and a coat of strong amphiphilic oleosin (0.5–3.5% w/w). These soybean oil bodies had a better physicochemical stability than emulsified soybean oil. Heat treatment (up to 55°C) did not affect the LOOH and hexanal content of oil body suspensions (2% wt at pH 3). | Natural organization protects unsaturated fatty acids. Water exists as nano-scale droplets in w/o emulsions |

| Rukmini et al. 130 | W/o microemulsion exist in bulk oil with nano-scale droplets of water inside. Formulation and stabilization of water-in-virgin coconut oil were prepared with food grade nonionic surfactants (Span 80, Span 20, and Tween 20). Cosurfactants may not be suitable for foods because of the toxicity and irritation induced by short- and medium-chain alcohols. Nonionic surfacts permitted stabilization of such w/o emulsion without the use of cosurfactants, but phase separation was observed when the microemulsion was heated at 70°C or higher | Nonionic surfactants offer an alternative solution as it stabilizes w/o emulsions and do not contribute to oxidation |

The initial observations related to the effects of molecular properties other than BDE were presented in the break through papers by late William Porter 36–38. He explained the role of a polar paradox by stating that polar (hydrophilic) antioxidant (e.g., Trolox C, ascorbic acid, propyl gallate, and TBHQ) are more effective in bulk lipids with a low surface/volume ratio whereas nonpolar (lipophilic) antioxidants (e.g., α-tocopherol, ascorbyl palmitate, BHA, and BHT) are more effective in oil-in-water emulsions (o/w) having a high surface/volume ratio. Shortly after, Frankel et al. 39–41 explained the polar paradox by the interfacial phenomena that hydrophilic antioxidants were more oriented at the air-oil interfaces in bulk lipids, while lipophilic antioxidants had more affinities toward water-oil interfaces in o/w. The interfacial phenomenon was first studied in o/w emulsions because of the wide availability of the methods needed to characterize these emulsions 14. Table2 presents results of investigations of the antioxidant potency of pairs of antioxidants shown in Fig. 1 having different polarities and effectiveness in bulk lipids confirming the polar paradox theory (e.g., carnosic acid vs. methyl carnosate 42,43, and quercetin vs. rutin 25,44). Examples for the effects of antioxidant polarity and steric hindrance on their effectiveness in bulk oils include the decrease in radical-scavenging activity by esterification of sinapic acid 45 and caffeic, dihydrocaffeic, and rosmarinic acids 46. Similarly, alkylation of ferulic acid 48 and hydroxytyrosol 51,52, and methylation of carnosic acid 42,43 cause their lipophilicity to increase and their antioxidant effectiveness in bulk oil to decrease. In addition, the presence of a double bond in the acyl substituent reduces the polarity and antioxidant capacity of propyl caffeate compared to hydrocaffeate and of ferulate compared to isoferulate 47. Catechin, with a trans configuration, has a better antioxidant activity than epicatechin, with a cis configuration 50. However, it was shown with epigallocatechin-gallate (EGCG) and its esters and with the glycosylation of quercetin (quercetin-3-O-glucoside and rutin) 25,44,49 that this effect is variable, that is, lipophilic antioxidants are sometimes more active in bulk oils (at lower levels) because the effects of lipid solubility on the antioxidant efficiency are stronger than those caused by the interfacial phenomenon. This suggests that the polar paradox might be applied only when antioxidant is added at high concentrations (above a critical concentration) where the interfacial phenomenon is dominant over solubility effects 53. This controversy is discussed below.

Table 2.

Results on antioxidants potency of pairs of antioxidants of similar structure and different hydrophilicity in bulk oil

| References | Antioxidants | Substrates and conditions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frankel et al. 39 | Ascorbic acid vs. ascorbyl palmitate | Stripped corn oil, added antioxidant (232 and 1161 μM), 60°C | Ascorbic acid was a more potent antioxidant than ascorbyl palmitate based on LOOH and hexanal formation |

| Carelli et al. 131 | SFO; each additive is at 200, 400, 600, and 800 ppm; 30 and 68°C (Oven); and 130°C (Rancimat) | Ascorbic acid was a more effective antioxidant than ascorbyl palmitate, according to Rancimat, and peroxide value (PV) (30°C), para-anisidine value (p-AV), total content, and distribution of polar compounds and residual α-tocopherol | |

| Sorensen et al. 61 | W/o emulsion (98% of 1:1 fish oil:rapeseed oil, stripped), 1% polyglycerol polyricinoleateemulsifier; antioxidants added at 100 mM; 37°C | Ascorbic acid was more effective antioxidant than ascorbyl palmitate on the basis of LOOH and propanal formation. Ascorbyl palmitate exhibited pro-oxidative effects toward the end of storage period | |

| Frankel et al. 39 | Trolox vs. α-tocopherol | Stripped corn oil, antioxidants added at 232 and 1161 μM, 60°C | Trolox was a better antioxidant than α-tocopherol on the basis of LOOH and hexanal formation. At the high concentration, α-tocopherol had a prooxidant effect |

| Schwarz et al. 43 | Stripped corn oil; w/o emulsion; cetheareth-15 and glyceryl stearate, polyglyceryl glucose methyl distearate, polysiloxan polyalcohol polyether copolymer and polyglyceryl-3 oleateas emulsifers each at 20% level; antioxidants added at 100 mM (based on the oil phase), 37 and 60°C | Trolox had higher activity than α-tocopherol based on LOOH and hexanal formation in both bulk oil and w/o emulsion with and without emulsifers. With a few exceptions, α-tocopherol showed better activity for w/o polysiloxan polyalcohol polyether copolymer emulsion based on LOOH and w/o polyglyceryl-3 oleate emulsion based on hexanal formation at 37°C. α-tocopherol showed a prooxidative effect in bulk oil with polyglyceryl-3 oleate at 60°C | |

| Huang et al. 60 | Linoleic acid, methyl linoleate, corn oil TAG, α-tocopherol are at 65 and 130 ppm and Trolox are at 38 and 76 ppm, 37 or 60°C in a shaking water bath | Trolox was a better antioxidant than α-tocopherol, in terms of LOOH and hexanal formation. With a few exceptions, α-tocopherol showed a better activity than Trolox (38 ppm), at 37°C, in bulk methyl linoleate and corn oil TAG based on hexanal formation; and at 60°C in bulk corn oil TAG, Trolox caused a pro-oxidative effect by hexanal results | |

| Chen et al. 20 | Stripped SBO; 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 1,2-dibutyryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine each at 1000 μM; antioxidants at 10 and 100 μM; 55°C | Trolox was a more effective antioxidant than α-tocopherol with and without the addition of phospholipids (except 1,2-dibutyryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine). 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine improved, while 1,2-dibutyryl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine decreased the α-tocopherol and Trolox activity | |

| Thiyam et al. 45 | Sinapic acid and sinapine | Purified rapeseed oil, sinapic acid, and sinapine at 50 and 500 μmol/kg oil, 40°C | Sinapic acid was better in reducing LOOH and propanal compared to its derivatives sinapine |

| Chen and Ho, 132 | Caffeic acid vs. caffeic acid phenethyl ester | Lard and corn oil each at 2 mM, Rancimat (110°C and 20 mL/min) | In lard, caffeic acid had better activity in extending the IP than caffeic acid phenethyl ester did. In corn oil, the activities of both antioxidants were the same |

| Nenadis et al. 46 | Caffeic acid vs. dihydrocaffeic acid | Triolein, each additive is at 10 ppm, 45°C in the dark | Based on the PV, the activity dihydrocaffeic acid was higher than caffeic acid and control. The presence of the conjugated double bond in the side chain of caffeic acid, makes its less polar and also decrease its hydrogen-donating properties, compared to dihydrocaffeic acid |

| Silva et al. 47 | Propyl caffeate and hydrocaffeate | Refined SFO, propyl hydrocaffeate, and propyl caffeate each at 160 and 200 ppm, Rancimat 110°C and 20 L/h | The antioxidant effectiveness of propyl hydrocaffeate was higher than that of propyl caffeate |

| Leonardis et al. 133 | Caffeic acid vs. chlorogenic acid (ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid) | Cod liver oil, antioxidants added at 0.005–0.05% by weight, Rancimat at 80 and 100°C and 20 L/h | Caffeic acid was a better antioxidant compared to chlorogenic acid. The later exhibited weak antioxidative effects |

| Laguerre et al. 134 | Chlorogenic acid and its esters | Stripped corn oil, each additive is at 200 μmol/kg, 55°C in the dark | Hydrophobicity of chlorogenic acid and its butyl, dodecyl, and hexadecyl esters did not correlate well with their antioxidant capacity in bulk oil. With and without dioleoylphosphatidylcholine, conjugated dienes test showed longer IP as the akyl chain increased |

| Chen and Ho 132 | Ferulic acid vs. ferulic acid phenetyl ester | Lard and corn oil, 2 mM, Rancimat (110°C and 20 mL/min) | In lard, ferulic acid and ferulic acid phenetyl ester had the same activity in extending the IP. In corn oil, both compounds had no significant effects in improving the oxidative stability |

| Fang et al. 48 | Ferulic acid vs. alkyl ferulates: 1-pentyl, 1-hexyl, 1-heptyl ferulates | Linolec acid; each additive is at 1.0 × 10−4, 3.0 × 10−4, 1.0 × 10−3, 3.0 × 10−3 molar ratios of the additive to linoleic acid; 37, 50, 65, and 80°C in the dark | Alkyl ferulate (1-pentyl, 1-hexyl and 1-heptyl ferulates) slightly increased the antioxidant activity compared to ferulic acid but their activities were not significantly different |

| Silva et al. 47 | Propyl ferulate and isoferulate | Refined SFO, propyl isoferulate, and propyl ferulate each at 160 and 200 ppm, Rancimat 110 °C and 20 L/h | Propyl isoferulate had a better antioxidant activity than propyl ferulate |

| Huber et al. 49 | Quercetin and quercetin-3-O-glucoside | Fish oil without antioxidant; each additive is at 100, 500, 1000, and 5000 μM; 70°C | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside had a higher antioxidant activity than quercetin at 100 and 500 μM. At 1000 μM, their activities were equal |

| Becker et al. 44 | Quercetin vs. rutin | Purified high-oleic SFO; each additive is at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mmol /kg oil; Rancimat 100°C and 20 L/h | The antioxidant activity of quercetin was higher than rutin |

| Wanasundara and Shahidi 25 | Refined-bleached and deodorized seal blubber oil and menhaden oil, each additive is at 200 ppm, 65°C in Schaal oven | The antioxidant activity of quercetin was higher than rutin in all substrates, as monitored by weight gain, PV, and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) | |

| Huang and Frankel 50 | Catechins | Corn oil TAG, each additive is at 140 μM, 50°C | According to LOOH formation: gallic acid had more antioxidant activity than epicatechin gallate and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) had more antioxidant activity than epigallocatechin |

| Shahidi and Zhong 53 | EGCG and its esters | Stripped corn oil; 1 mL/3 g, Rancimat (100°C and 20 L/h) | At lower concentrations, the antioxidant activity of EGCG was lower than its lipophilic ester derivative (stearate); but the effects were reversed at higher concentrations |

| Huang et al. 42 | Carnosic acid and methyl carnosate | Corn oil TAG, each additive is at 150 and 300 μM, 60°C | The antioxidant activity of methyl carnosate was higher than carnosic acid on basis of LOOH and hexanal formation |

| Schwarz et al. 43 | Tocopherol-stripped corn oil; w/o emulsion; cetheareth-15 and glyceryl stearate, polyglyceryl glucose methyl distearate, polysiloxan polyalcohol polyether copolymer, and polyglyceryl-3 oleate emulsifers each is at 20% level; antioxidants added at 100 mM (based on oil phase), 37 and 60°C | Methyl carnosate had higher antioxidant activity compared to carnosic acid in both bulk oil and w/o emulsions according to LOOH and hexanal formation, which does not agree with the polar paradox | |

| Frankel et al. 40 | Carnosic acid and carnosol | Stripped corn oil, each additive is at 50 ppm, 60°C in a shaker oven | Carnosic acid had a higher antioxidant activitiy than carnosol in bulk oil on the basis of LOOH and hexanal formation |

| Frankel et al. 41 | Corn oil, SBO, peanut oil, and fish oil. Each additive is at 30 and 50 ppm, 60°C | Carnosic acid had a higher antioxidant activitiy than carnosol in bulk corn oil, SBO, peanut oil, and fish oil on the basis of conjugated dienes and hexanal formation | |

| Hopia et al. 59 | Methyl linoleate, linoleic acid, corn oil TAG, additives at 150 and 300 μM, 37 and 60°C | Carnosic acid was a better antioxidant than carnosol in methyl linoleate and corn oil but not in bulk linoleic acid where carnosol had better activity than carnosic acid. The substrate seems to affect the performance of antioxidants | |

| Trujillo et al. 51 | Hydroxytyrosol and its fatty acid esters | Glyceridic matrix, each additive is at 1 and 5 mM, Rancimat 90°C | Hydroxytyrosol had higher antioxidant activity than hydroxytyrosyl acetate, palmitate, oleate, and linoleate |

| Medina et al. 52 | Fish oil, each additive is at 10, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 ppm, 40°C | Hydroxytyrosol had better antioxidant activity than its esters with increasing size of alkyl chain (i.e., hydroxytyrosol acetate, butyrate, octanoate, laurate, and octyl gallate) | |

| Medina et al. 104 | Resveratrol vs. acylated and glucosylated resveratrol | Cod-liver oil, each additive is at 100 ppm, 40°C | Resveratrol fatty acid esters with increasing size of alkyl chain (i.e., 3-stearoylresveratrol, 3-stearoylresveratrol, and 4′-stearoylresveratrol) and glucosylation (i.e., resveratrol-3-β-d-glucopyranoside, resveratrol-3, 5-di-β-d-glucopyranoside, and resveratrol-3,4′-di-β-d-glucopyranoside) had reduced antioxidant effectiveness compared to original phenol |

The role of micelles and association colloids

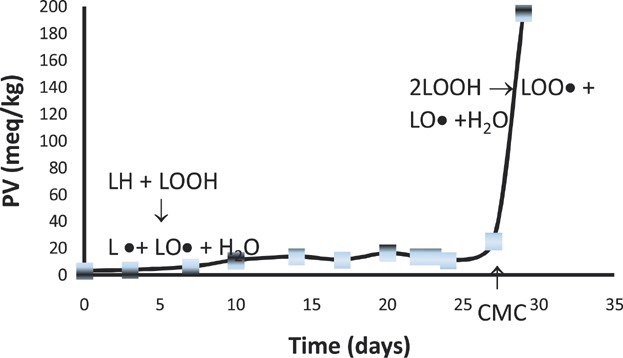

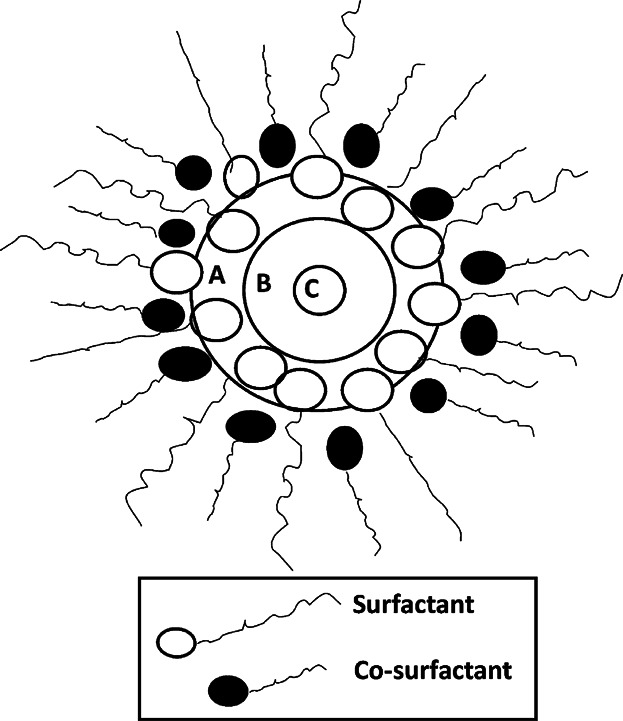

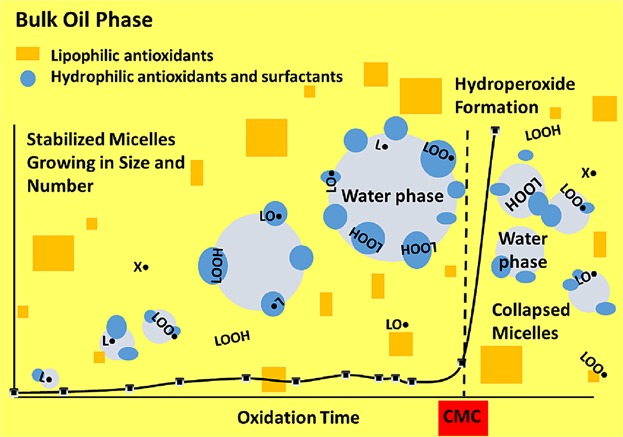

Koga and Terao 54 suggested that phospholipids enhance the antioxidant activity of α-tocopherol in bulk lipids because they aggregate to form microemulsions thus bringing the tocopherol closer to the oxidation site (or increased partition in the water phase of reversed micelles). Accordingly, the phenolic group of α-tocopherol and the polar head of the phospholipids are positioned near the polar region of the reversed micelles where radicals are formed and trapped while the nonpolar acyl chains are located in oil phase. Thus, these authors recognized the lipid oxidation reaction sites as the interfaces formed between traces of water and the continueous lipid phase rather than the air-oil interfaces suggested by Frankel et al. 39–41. It has also already been evident for Ulla Brimberg 26,27 that the transition of lipid oxidation from the initiation to the propagation phase is governed by the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of hydroperoxides and its modification by other amphiphiles acting as antioxidants, prooxidants, or modifiers (synergists or antagonists). Brimberg proposed a set of empirical equations that was also able to successfully describe the oxidation of different oil/additive combinations 26,27. Brimberg and Kamal-Eldin 56 proposed that lipid oxidation in bulk oil starts by pseudo-first order slow build-up of hydroperoxides until these reach their CMC and start aggregation to form reversed micelles. At this point, the reaction rate change to a second order reaction and the oxidation enters the propagation phase (Fig. 2). Accordingly, the main effects of anti- and prooxidants depend on their modulation of the CMC of lipid hydroperoxides.

Figure 2.

Peroxide value (PV) evolution during the autoxidation of flaxseed oil at 40°C. The first period (lag phase or induction period) is dominated by reactions between unsaturated fatty acids (LH) and low concentrations of hydroperoxides (LOOH). This reaction is first order with respect to LH and LOOH but because of the relatively very high concentration of LH and the very low concentration of LOOH, it is often described as zero order. When the concentration of LOOH reaches its critical micelle concentration (CMC), formation of micelles become significant and the reaction enter the bimolecular phase with respect to hydroperoxides. Attainment of CMC marks the end of the induction period (IP).

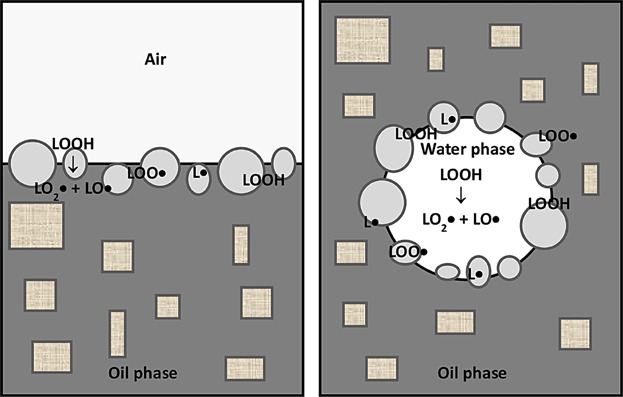

It started to become clear that lipid oxidation is affected by several properties of emulsion droplets and interface properties including droplet size, interfacial area, charge, thickness, and permeability 14,57,160. For example, cationic charge caused transition metals to be excluded from the interface hence lessening oxidation rates in o/w 14. This finding was later verified in bulk oils when the research group of Decker et al. studied these phenomena in depth and reported several supporting findings 14,22,160. The conclusion is that compounds that are surface active change the physical location or the state of other compounds that form reversed micelles in bulk oils such as hydroperoxides and metals 20,33. When water, other polar compounds, and amphiphilic molecules (e.g., lecithin) coexist in oil, association colloids (e.g., reversed micelles) are formed providing a reaction site for oxidation to take place 14,33. Oxygen, the primary catalyst of lipid oxidation, is 3–10 times more soluble in oil than in water and in fact, air (dielectric constant = 1.0) is much nonpolar than oil (dielectric constant = 3.0). Thus hydrophilic antioxidants are more likely to partition at the oil-water interface than at the air-oil interface supporting the assumption that the microemulsions in the oil are the site of oxidation 14,42,53,59–61. These polar antioxidants aggregate to form microemulsions and create a shield to protect micelles 14,62. In the same way, emulsifiers enhance the formation of micelles that entrap amphiphilic antioxidants and bring them to the interphase 63,64. On the other hand, lipophilic antioxidants are less effective in retarding oxidation in bulk lipids because they disperse in the continuous oil phase far away from the catalytic sites of the micelles while they are effective in protecting o/w emulsions because they orient more at the water-oil interface 33,39,61,169.

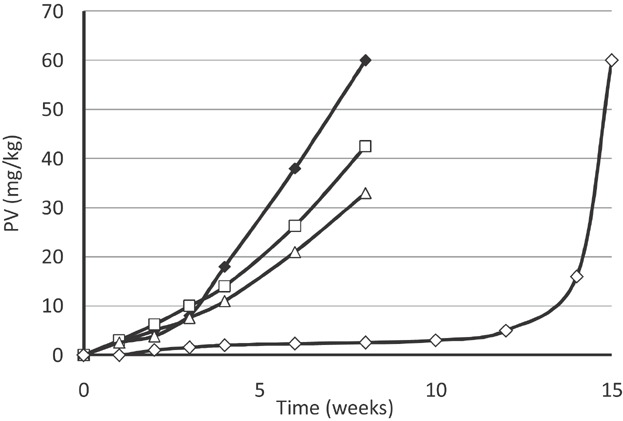

Table3 presents collated results on the effect of different additives on lipid oxidation in bulk oil. The more hydrophilic Trolox was found to be a better antioxidant than α-tocopherol because it concentrates in the water phase of the mixed micelles 7,65. On the other hand, trace metal ions act as prooxidants by migrating to the oil-water interface of the micelles 57,66,67. Similarly, free fatty acids and monoacylglycerols act as prooxidants by a “micellar effect” by concentrating at the oil-water interface and accelerating the decomposition of hydroperoxides 33,39,61,169. On the other hand, phospholipids act as synergists by enabling the antioxidants at the interface 14,33, where the polar heads of the antioxidants are located at the water-oil interface and their hydrogen atoms are donated to the radicals. Thus, the antioxidants and phospholipids (synegist) trap the radicals in a cage (i.e., microenvironment) 54 and prevent their diffusion into the bulk oil; the so called volume cage effect 68. The combination of antioxidants and surfactants can act synergistically or antagonistically depending on their types (Fig. 3) and concentrations 69. The effects of surface-active agents are influenced by their hydrocarbon chain length, hydrophilic lipophilic balance, and concentrations 63,64.

Table 3.

The effects of different types of additives on the stability of bulk lipids

| References | Substrates and oxidation conditions | Additive(s) | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty alcohols | ||||

| Yanishlieva and Kortenska 135 | SFO, OO, lard, tristearin, olive oil methyl esters, 70–135°C | 1-Tetradecanol, 1-hexadecanol, 1-eicosanol (5–80 mmol/kg) | The pro-oxidative effects of fatty alcohols depend on the type, concentration, valency of the alcohols and LOOH, and the degree of unsaturation of the lipid media. The pro-oxidative effect was less in TAG than in fatty acid methyl esters | Fatty alcohols antagonized the antioxidant effect of phenolic inhibitors |

| Kortenska et al. 136 | SFO, methyl ester, 50°C | p-Methoxyphenol (0.1 M), 1-octadecanol (0.1 M), and 1-palmitoylglycerol (0.1 M) | 1-Octadecanol and 1-palmitoylglycerol acted as prooxidant, by decreasing the rate constant of chain termination, in the presence of inhibitor (p-methoxyphenol) | Fatty alcohols inhibited inhibitor by formation of H-bonds and complex formation with the inhibitor. 1-palmitoylglycerol had a stonger effect because of its two hydroxyl groups |

| Yanishlieva and Kortenska 137 | TAG of SFO and TAG of OO, 23 and 110°C | Hydroquinone (1 × 10−4 mol/L), 1-tetradecanol, 1-octadecanol ([0.5−9.0] × 10−2 mol/L) | Fatty alcohols accelerated the oxidation of lipids (in the presence of hydroquinone). Increasing unsaturation of substrate caused a lesser prooxidative effect of the alcohols | Shorter chain alcohols caused stronger complex formation (H-bond) with hydroquinone. However, longer chain alcohols had a higher prooxidative activity in the propagation, branching, and termination reactions |

| Kortenska and Yanishlieva 138 | TAG of SFO, 80°C | Hydroquinone, BHT, α-tocopherol (each at 0.1 mM); 1-tetradecanol, 1-octadecanol (5, 20, 40, and 60 mM) | Fatty alcohols acted as prooxidants. A linear dependence of oxidation of oil was seen, with hydroquinone, in the presence of 1-tetradecanol, α-tocopherol + 1-tetradecanol + 1-octadecanol. No interactions between BHT and 1-octadecanol in inhibiting oxidation | There was no interaction between 1-octadecanol and BHT, because 1-octadecanol participates in the process only by accelerating the decomposition of LOOH |

| Kortenska et al. 68,81 | TAG of SFO, 80°C | 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol (0.1 mM), 1-tetradecanol (40 mM), 1-octadecanol (40 mM), and 1-monopalmitoylglycerol (40 mM) | Fatty alcohols decreased the IP, as measured by LOOH. 1-monopalmitoylglycerol caused a further reduction of IP. BHT + fatty alcohols also exhibited prooxidative effects, with no improvement on the IP | Polar compounds such as fatty alcohols and oxidation products associate in non-polar medium. LOOH decomposed faster inside the polar interior of the micro emulsion. Fatty alcohols alone and combined with BHT were prooxidants |

| Kortenska et al. 68 | SFO and lard, 100°C | α-Tocopherol (1.3 mM), 1-octadecanol (5, 40, and 80 mM) | The higher the 1-octadecanol level, the more the reduction of IP and increase of oxidation rate in both medium. The relative increase of oxidation rate in SFO was more than in lard | Fatty alcohols acted as prooxidant and inhibited α-tocopherol activity |

| Free Fatty Acids (FFA) | ||||

| Miyashita and Takagi 115 | Oleic acid, methyl oleate, linoleic acid, methyl linoleate, linolenic acid, methyl linolenate; 50°C in the dark | No additives | Methyl esters are more stable than their corresponding FFA (longer IP and have lower PV) | FFAs are more susceptible to oxidation than corresponding esterified fatty acids. The catalytic effect of the carboxyl groups of FFA on the formation of free radicals and decomposition of LOOH was thought to be the reason. According to the current theory a bulk of FFAs is different from a bulk of TAGs in the molecular assembly of the substrate itself and of any added additive. FFAs are surface active and contribute to micelle formation when added to TAGs |

| Methyl linoleate and SBO; 50°C in the dark | Stearic acid (0, 0.5, 1, 3, and 5%) | The addition of stearic acid to methyl linoleate or SBO did not affect the IP but increased the oxidation rate during this IP | ||

| Methyl linoleate hydroperoxides; 50°C in the dark | Stearic acid (0, 0.2, 0.5, and 1%) | Hydroperoxides (PV and conjugated diene content), decomposed faster in the presence of stearic acid | ||

| Mistry and Min 139 | SBO, forced air oven 55°C | Stearic, oleic, linoleic, linolenic, or octadecane (0, 0.5, and 1%) | FFA, but not octadecane, showed prooxidant activity in SBO (PV, volatile compounds, and oxygen in the headspace) | |

| Hamam and Shahidi 140 | Doxosahexaenoic acid single cell oil; Schaal oven 60°C | Capric acid (not added but due to acidolysis) | Acidolysis of the single cell oil, with capric acid, decreased the oxidative stability of the oil (Conjugated dienes and TBARS) compared to unmodified doxosahexaenoic acid single cell oil | |

| Frega et al. 141 | Virgin OO; Rancimat 110°C, 20 L/h; OO (cloudy untreated, cloudy paper-filtered, cloudy membrane-filtered, and cloudy bleached with clay); Rancimat 110°C, 20 L/h | Oleic acid or methyl oleate (0–3%) | Methyl oleate but not oleic acid (% acidity) decreased the IP of virgin OO. Oleic acid (% acidity) increased the IP of cloudy untreated oil, did not affect the IP of cloudy paper-filtered oil, and decreased the IP of cloudy membrane-filtered and cloudy bleached oils | The prooxidant effect of FFA is dependent on the matrix. For example, oleic acid had a prooxidant activity in membrane-filtered and bleached OO but not in cloudy oils; and methyl oleate but not oleic acid had a prooxidant effect on virgin OO |

| Chaiyasit et al. 14 | Methyl linolenate in model oil system containing sodium bis(2-ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate, water-hexadecane; ferrous sulfate, 24°C in the dark | Oleic acid (0, 25, 50, and 100 mmol/kg lipid) | Oleic acid reduced the reversed micelle size and accelerated lipid oxidation (LOOH and TBARS) compared to a control and added phosphatidylcholine | The prooxidant effect of FFA seems to be related to their action as surfactants (increasing the number of small micelles) |

| Monoacylglycerols (MAG) and diacylglycerols (DAG) | ||||

| Mistry and Min 142 | Refined, bleached, and deodorized SBO, forced-air oven 55°C | 1-Monolinolein (0.01%) | MAG (1-monolinolein) had prooxidant activity in SBO (PV and volatile compounds) | MAG and DAG showed prooxidant effects in pure (but not unpure TAG) depending on polarity, concentration, and temperature |

| Mistry and Min 143 | SBO, forced-air oven 55°C | Monostearin, monolinolein, distearin, and dilinolein (0, 0.25, and 0.5%) | Monostearin, monolinolein, distearin, and dilinolein acted as prooxidants in SBO (decrease of headspace oxygen) in a concentration-dependant manner | |

| Caponio et al. 144 | Purified SBO, oven 60°C; measured at 4, 6, 9, 14, and 18 days | Unnamed MAG (0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3%) | The effect of MAG in the oxidation of purified SBO is concentration-dependent. At low amount (0.5 and 1%), MAG increased the oxidation rate while at higher concentrations the IP was reduced | |

| Aubourg 65 | Cod liver oil containing citric acid; 15, 30, and 50°C | Unnamed MAG (0.1, 0.5, 2, and 5%) | MAG (2 and 5%) caused an inhibitory effect on the protective effect of citric acid at 50, but not at 15 and 30°C | MAG and DAG enhanced the oxidation of cod liver oil containing citric acid, which functions as a metal chelator. A longer chain length increased the prooxidant effect possibly because of increased surfactant activity |

| Cod liver oil containing citric acid; 50°C | Monolauroyl-glycerol, monomiristoyl-glycerol, monopalmitoyl-glycerol, and monostearoyl-glycerol (3.78 mM) | The prooxidant effect of MAG increased as the chain length of MAG increased | ||

| Cod liver oil containing citric acid; 30 and 50°C | Unnamed diacylglycerols (0.1, 0.5, 2, and 5%) | DAG showed an inhibitory effect on the protective effect of citric acid at 50 but not 30°C. There was no difference in effect between different DAG concentrations | ||

| Wang et al. 145 | Purified and natural corn oil; 28°C | 1-Monolinoleoyl-rac-glycerols (0, 0.1, 0.25, and 0.5%) | MAG decreased the IP for purified but not for unpurified oil | MAG may contribute pro-oxidant effect(s) in the oxidation of bulk oils |

| Natural and randomized corn oil, Oxidative Stability Index (OSI), 28°C | 1-Monolinoleoyl-rac-glycerols and 1,3-dilinoleoyl-rac-glycerol (conc. unknown) | MAG showed a higher prooxidant activity than DAG (reduced OSIIP) | ||

| Natural and randomized corn oil; 28°C | 1,3-Dilinoleoyl-rac-glycerol (5%) | There was an increase in the oxidation rate of purified oil with 5% DAG but the increases were not as great as that of randomized oil | ||

| Phospholipids (PL) | ||||

| King et al. 146 | Salmon oil, Fischer forced-draft oven, 180°C | Phosphatidylcholine (0.01, 0.1, and 1%) | Phosphatidylcholine improved the oxidative stability of the oil in a concentration-dependant manner (as measured by TBARS and polyene index) | The amine group of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine and the reducing sugar of phosphatidylinositol can facilitate hydrogen or electron donation by α-tocopherol at 180°C. Nitrogen-containing phospholipids perform better in improving the oxidative stability of oil than those that do not contain nitrogen |

| Salmon oil, Fischer forced-draft oven, 180°C | Phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, and sphingomyelin (1% each) | Nitrogen-containing phospholipids (i.e., phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylcholine, and sphingomyelin showed higher antioxidant acitivity than phosphatidylglycerol and phosphatidylinositol (yielded the least activity). The slope of oxidation rate showed that sphingomyelin was the most effective and phosphatidylinositol was the least effective | ||

| Methyl linoleate, methyl laureate, 50°C in the dark, continuous shaking at 120 rpm | Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC, 100 nM), dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanol-amine (DPPE, 100 nM), α-tocopherol (10 nM) | Without α-tocopherol, Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine gave a slower oxidation rate than dipalmitoylphosphatidylethanolamine. With α-tocopherol, IP was prolonged and methyl linoleate-OOH accumulated after α-tocopherol was consumed. DPPC and DPPE showed an insignificant effect in oxidation rate, in the presence or absence of α-tocopherol | DPPC and DPPE act synergistically with α-tocopherol, but the effect is insignificant | |

| Koga and Terao 54 | Methyl linoleate; methyl laureate; 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropyl) dihydrochloride (AAPH) (water soluble radical initiator); 2,2′-azobis(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile) (AMVN) (lipid soluble radical initiator), 50°C in the dark, continuous shaking at 120 rpm | Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine, dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine, dicaprylphosphatidylcholine, and dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (each 100 nM), α-tocopherol (10 nM) | With the use of 2,2′-azobis(2-amidinopropyl) dihydrochloride, phospholipids caused a more rapid consumption of α-tocopherol. With 2,2′-azobis(2,4-dimethylvaleronitrile), phospholipids did not affect the consumption of vit E. The IP increased with increasing hydrocarbon chain length of acyl moieties of phospholipids | Phospholipids accelerated the consumption of α-tocopherol when radicals are generated from water-soluble radical generators with a trace of water |

| Khan and Shahidi 84 | Borage oil TAG, dark, in a Schaal oven at 60°C | Phosphatidylcholine (500 ppm), phosphatidylethanolamine (500 ppm), α-tocopherol (500 ppm), δ-tocopherol (500 ppm) | Phosphatidylcholine lengthened the oxidation time more than phosphatidylethanolamine (based on conjugated dienes). Combinations of phosphatidylcholine + α-tocopherol., phosphatidylcholine + δ-tocopherol, phosphatidylethanolamine + α-tocopherol, phosphatidylethanolamine + δ-tocopherol (500 ppm phospholipids and 500 ppm tocopherol) lengthened the oxidation time than individually added phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, α-tocopherol, and δ-tocopherol. Combination of α-tocopherol with each phospholipid was more effective than combination of δ-tocopherol. The most effective combination was that of phosphatidylcholine and α-tocopherol (on basis of TBARS) | Phosphatidylcholine is more effective than phosphatidylethanolamine alone and in combination with α-tocopherol in borage oil TAGs. Phosphatidylethanolamine was more effective than phosphatidylcholine in evening primose TAGs. Phospholipids increase the accessibility of the tocopherols to the aqueous environment (the micellar phase) |

| Evening primrose oil TAG, dark, in a Schaal oven at 60°C | Phosphatidylcholine (500 ppm), phosphatidylethanolamine (500 ppm), α-tocopherol (500 ppm), and δ-tocopherol (500 ppm) | Phosphatidylethanolamine lengthened the oxidation time more than phosphatidylcholine (based on conjugated dienes). Combinations of phosphatidylcholine + α-tocopherol, phosphatidylcholine + δ-tocopherol, phosphatidylethanolamine + α-tocopherol, phosphatidylethanolamine + δ-tocopherol (500 ppm phospholipids and 500 ppm tocopherol) with the combinations with phosphatidylethanolamine being more effective than those with phosphatidylcholine (on basis on TBARS) | ||

| Hidalgo et al. 147 | Refined SBO, heated in the dark under air at 60°C | Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylinositol (each 200 ppm) | Phospholipids lengthened the IP (phosphatidylcholine > phosphatidylethanolamine > phosphatidylinositol) and the protection was better with oxidized phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylinositol (by polymeric pyrroles). Phosphatidylethanolamine showed max. antioxidative activity when the pyrrole content was between 800–1400 nmol of pyrrole/mmol of phosphatidylethanolamine | Phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylinositol improved the oxidative stability of the oil. Lysine activity as antioxidant was improved in combination with phosphatidylethanolamine or phosphatidylcholine (synergism). No synergism was observed for phosphatidylcholine plus phosphatidylethanolamine |

| Refined OO (ROO), Rancimat 110°C | Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysine, and BHT (each added at 4 levels: 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm) | Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysine, and BHT increased oxidative stability of the oil at 200 ppm or more. The IP of oil with 400 phosphatidylethanolamine had similar stability as that of oil with 200–400 ppm BHT | ||

| Phosphatidylethanolamine and/or lysine (combinations at 100/300,200/200, and 300/100 ppm) | Phosphatidylethanolamine and lysine showed a better protection to the oil than when each was added alone. The IP increased in the following sequence 100/300 < 200/200 < 300/100 ppm | |||

| Phosphatidylcholine and/or lysine (combinations at 100/300, 200/200, and 300/100 ppm) | Phosphatidylcholine and lysine showed a better protection to the oil than when each was used alone. The IP increased in the following sequence 200/200 ≤ 300/100 < 100/300 ppm | |||

| Phosphatidylcholine and/or phosphatidylethanolamine (combination at 100/300, 200/200, and 300/100 ppm) | Phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine did not exhibit any synergism | |||

| Koprivnjak et al. 73 | Filtered virgin OO, Rancimat, 120°C | Phospholipids (lecithin) (0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 g/kg) | As the amount of lecithin increased, IP lengthened. The addition of lecithin also increased total tocopherols but decreased the α/γ tocopherol ratio | |

| Lee and Choe 148 | Tocopherol-stripped SFO; Water in oil emulsion consists of methylene chloride, n-butanol, Na2MoO4·2H2O, sodium dodecyl sulfate; rubrene (a singlet oxygen quencher); 25°C for 24 h | Phosphatidylcholine (0, 250, and 1000 ppm) | Phosphatidylcholine extended the IP of the oil. Different phospholipids concentrations have the same effects | |

| Chen et al. 7 | Stripped SBO, 25°C for 24 h | Dioleoylphoshatidylcholine, dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine, (each 0–1270 mmol/kg) | The association colloids formed by dioleoylphoshatidylcholine and water were prooxidative, while those formed by dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine were comparable to control | The structure of association colloids may influence lipid oxidation in bulk oils. Dioleoylphoshatidylcholine and dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine have identical choline groups but different physical structure in oil. SAXS measurement revealed that dioleoylphoshatidylcholine formed spherical structures while dibutyrylphosphatidylcholine formed cylindrical structures |

| Chen et al. 20 | Stripped SBO, 50°C | Dioleoylphoshatidylcholine (1000 μM), α-tocopherol (10 and 100 μM), and Trolox (10 and 100 μM) | Dioleoylphoshatidylcholine formed reversed micelles in oil and shortened the IP. Dioleoylphoshatidylcholine improved the activity of low α-tocopherol or Trolox concentrations (10 μM) but decreased the activity at high concentrations (100 μM) | |

| OH-containing carotenoids | ||||

| Haila et al. 149 | TAG from low-erucic acid rapeseed oil, under dark at 40°C | Lutein (5, 20, 30, and 40 ppm), lycopene (20 ppm), annatto (20, 30, and 60 ppm as bixin), β-carotene (20 ppm), γ-tocopherol (10 and 15 ppm), lutein + γ-tocopherol (20 + 15 ppm, 1:1 in molar ratio), or lutein + γ-tocopherol (20 + 10 ppm, 1.5:1 in molar ratio) | Lutein caused more LOOH. Lutein (20 ppm) + γ-tocopherol (15 ppm) were antioxidants. Lutein was consumed faster and slower (higher retention), without and with γ-tocopherol, respectively. The consumption of γ-tocopherol was not affected by lutein. Total of 30 and 60 ppm bixin (annatto) was significantly reduced LOOH levels | Lutein was prooxidant both in the dark and light. When lutein is combined with tocopherol, they significantly increase oxidative stability. Lycopene and β-carotene were prooxidants |

| Henry et al. 150 | Purified safflower seed oil, OSI, 75°C for 24 h, 85°C for 12 h, 95°C for 5 h | Lycopene (35 μM), lutein (66 μM), 9-cis-β-carotene (54 μM), and all-trans-β-carotene (150 μM) | The orders of the rate of degradation were lycopene >9-cis-β-carotene = all-trans-β-carotene > lutein | Geometric configurations do not effect the decomposition rate, as in 9-cis and all-trans carotene. OSI in hours and lipid oxidation measurements (e.g., PV, TBARS) need to be performed to study the effects of carotenoids on safflower oil oxidation |

| Subagio and Morita 151 | Purified corn-oil TAG, paraffin, 40°C, dark | α-Tocopherol, β-carotene, and lutein (each at 5, 10, and 30 ppm and combination of 30 and 30 ppm) | Lutein increased the amount of LOOH. β-carotene + lutein caused more degradation of β-carotene. Lutein was more unstable than β-carotene in paraffin (medium similar to TAG) | The antioxidative effect of β-carotene was dose-dependent, at higher concentration it became prooxidant. When combined, β-carotene protected lutein, as β-carotene degraded more than lutein in oil. But in paraffin it is the opposite |

| Kiokias and Gordon 71 | Purified OO, oven, 60°C | β-carotene (1 g/L), annatto oil-soluble (bixin; 1 g/L), and annatto water-soluble (norbixin) (1 and 2 g/L), virgin olive oil polar extract (0.2 g/L), α-tocopherol (0.1 mM), γ-tocopherol (0.1 mM), ascorbic acid (0.1 mM), and ascorbyl palmitate (0.1 mM) | Norbixin showed synergisms with ascorbic acid, ascorbyl palmitate, and tocopherols, which were beyond the effect of phenolic antioxidants in oils and emulsions. These effects are better than that of β-carotene or β-carotene and polar extract | The presence of polar carboxylic acid groups in the norbixin molecule may contribute to chelation of metal ions or other polar initiating species, thus retarding autoxidation of oil |

| Becker et al. 44 | Purified SFO; Rancimat (OSI), 100°C, 20 L/h | α-Tocopherol, rutin, astaxanthin, quercetin (each at 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μmol antioxidant/g oil, and their combination of 1.0 + 1.0, 0.5 + 0.5, and 0.25 + 0.25 μmol/g) | The antioxidant ranking in bulk oil: quercetin > α-tocopherol ≫ astaxanthin = rutin | Astaxanthin exerts antioxidant activity in bulk oil |

| Zeb and Murkovic 152 | Refined OO, Rancimat, 110°C, 1–14 h | β-Carotene, E-astaxanthin (300 ± 0.5 ppm) in olive oil | E-astaxanthin protected olive oil from oxidation (reduced epoxides) and inhibited β-carotene degradation | 9-Z-astaxanthin showed a higher antioxidant effects among E and Z-astaxanthin. β-Carotene acted as prooxidant after prolonged heating |

| Amino acids | ||||

| Ahmad et al. 153 | Safflower oil, a mixture of sunflower and cottonseed oil, active oxygen method at 97.8°C | Cysteine, proline, tryptophan, methionine, glutamic acid, lysine, and arginine (each at 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.07, 0.10, 0.40, 0.70, and 1.00%) | Cysteine and glutamic acid were prooxidants in the oil mix, and glutamic acid was prooxidants in the safflower oil. The highest protection activity in the safflower oil was due to methionine, proline, lysine, and cysteine. The highest protection activity in the mix was due to lysine, arginine, glutamic acid, methionine, and hydroxyproline. However the amino acid protection activities were very low, low, or medium | Antioxidative activity of amino acids in such oils was low. It could be that they do not contribute as antioxidant by themselves, but requiring primary antioxidants |

| Alaiz et al. 154 | SBO, air in the dark at 60°C | N-(Carbobenzyloxy)-1(3)-[1′-(formylmethyl)hexyl]-l-histidine dihydrate (compound 1) formed from reaction of histidine and (E)-2-octenal (50, 100, and 200 ppm), Z-histidine (50, 100, and 200 ppm) | The order of stability: Compound 1 > Z-Hitidine > Control. The protection index of compound 1 and Z-histidine increased with concentration | Reactions of products from lipid oxidation (aldehydes) and amino acids exhibited an antioxidant property. The polymerization of these compounds produces melanoidin-like polymers which cause changes in color and fluorescence |

| Carlotti et al. 123 | Linoleic acid in sodium dodecylsuphate micellar solutions (with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and azo-initiator added), pH 5.0 and 7.0, 45 and 56°C | α-Tocopherol (1.0−6.0 × 10−6 M), α-tocopherol: 5.0 × 10−6 M, and ascorbic acid: 0.4−1.0 × 10−4 M, α-tocopherol: 5.0 × 10−6 M, and ascorbic acid: 0.5 × 10−4 M, l-tryptophan (8.5 × 10−5 M − 1.0 × 10−4 M), l-alanine (1.0 − 1.2 × 10−4 M), l-cysteine (8.5 × 10−4 M − 1.0 × 10−4 M), glycine (1.0 − 1.5 × 10−4 M), and gluthathione reduced form (7.5 − 8.5 × 10−5 M) | Glutathione, l-tryptophan, l-alanine, l-cysteine, and glycine prolonged the IP of micellar solution (containing 5.0 × 10−6 M α-tocopherol + 5.0 × 10−6 M vit C) at pH 5.0 and 7.0 (at 45°C). The synergistic action was particularly significant for l-cysteine, l-tryptophan, and Glutathione | Amino acids exhibited antioxidative effects, either added alone or combination with other amino acids or α-tocopherol |

| Hidalgo et al. 155 | Refined OO, Rancimat, 110°C | Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysine, BHT (each 0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm and combination of phospholipids of 100, 200, or 300 ppm with amino acid of 100, 200, or 300 ppm) | Lysine (200 ppm or more) increased IP, which was superior to those of oil with phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and BHT of the same concentration. A total of 300 ppm phosphatidylethanolamine + 100 ppm lysine caused 185% increase of IP compared to control, and when both were used alone. Phosphatidylcholine and lysine increased the IP | Lysine and phosphatidylethanolamine or phosphatidylcholine exhibited synergism. The amino group of lys reacted with oxidized lipids to form hydrophilic pyrroles, which are good for oil (polar paradox) |

| Papadopoulou and Roussis 156 | Corn oil; 50, 120, and 180°C | N-acetyl cysteine and gluthathione (10, 20, and 40 mg/L),butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA; 200 mg/L) | N-acetyl cysteine and gluthathione reduced the formation of conjugated dienes, trienes, and PV at 50, 120, and 180°C. The antioxidative ranking were BHA > N-acetyl cysteine > gluthathione; except that at 180°C, N-acetyl cysteine were more effective than BHA | N-acetyl cysteine and gluthathione are hydrophilic compounds, which have more affinities toward the air-oil interface in bulk oil, thus more effective than lipophilic ones in bulk oil |

| Hidalgo et al. 157 | Stripped virgin OO, β-sitosterols added stripped virgin OO, Rancimat, 90°C, 10 L/h | Phosphatidylethanolamine (0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm), phosphatidylcholine (0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm), lysine (0, 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm), and β-sitosterols (1500 μg) | Phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, lysine, and their combinations cause a significantly higher antioxidative effects in β-sitosterol added virgin OO, compared to virgin OO. The combined phosphatidylethanolamine/phosphatidylcholine gave a shorter IP but phosphatidylethanolamine/lysine and phosphatidylcholine/lysine increased the IP, more than when the components were added alone | Amino groups of lysine react with oxidized lipids to form hydrophilic pyrroles, which may contribute to the stabilization of oil |

| Citric acid and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | ||||

| Hras et al. 158 | Stripped SFO, oven, 60°C | Rosemary extract (0.02%), α-tocopherol(0.01%), ascorbyl palmitate (0.01%), citric acid (0.01%), and their combinations | Citric acid alone reduced peroxide value (PV) and anisidine value (AV), but the activity was lower than the extract and ascorbyl palmitate. The order of antioxidant activity: extract + ascorbyl palmitate > extract + citric acid > extract > extract + AT > control | Citric acid is a chelating agent, by forming bonds between the metal and the carboxyl or hydroxyl groups of the citric acid molecule. Citric acid alone had antioxidant role. The effect was greater when citric acid was combined with extract |

| Jaswir et al. 159 | Fresh, cold-pressed, unrefined, and antioxidant-free flaxseed oil, heated to frying temp. 165 ± 5°C for 3.5 min, then 165°C for 6 min., and allowed to reach 60°C at room T, flushed with N2 gas and kept in a cold room at 4°C until analysis | Oleosin rosemary extract (0, 0.05, and 0.1%), sage extract (0, 0.05, and 0.1%), and citric acid (0, 0.025, and 0.05%) | Antioxidants (extracts and their combinations) significantly reduced PV, p-AV, FFA, color yellow, C18:1, C18:2, and C18:3, reduced some of absorbances at 232 and 268 nm, but increased C16:0 and C18:0 | Antioxidants added to the oil before frying were effectively retarding lipid oxidation and reducing oil hydrolysis during deep frying |

| Wang et al. 145 | Natural and randomized corn oil; OSI, 100°C | Citric acid (100 and 200 ppm) | Randomized corn oil had a much lower OSI than natural corn oil does. Citric acid (200 ppm) partially restored the OSI of randomized oil | Citric acid protective effect is not related to chelation of transition metals |