Abstract

Objective

To examine real-world treatment patterns of lipid-lowering treatment and their possible associated intolerance and/or ineffectiveness among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating statins and/or ezetimibe.

Research design and methods

Adult (aged ≥18 years) patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes who initiated statins and/or ezetimibe from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2011 were retrospectively identified from the IMS LifeLink Pharmetrics Plus commercial claims database. Patients were further classified into 3 high-risk cohorts: (1) history of cardiovascular event (CVE); (2) two risk factors (age and hypertension); (3) aged ≥40 years. Patients had continuous health plan enrolment ≥1 year preindex and postindex date (statin and/or ezetimibe initiation date). Primary outcomes were index statin intensity, treatment modification(s), possible associated statin/non-statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues (based on treatment modification type), and time-to-treatment modification(s). Analyses for each cohort were stratified by age groups (<65 and ≥65 years).

Results

A total of 9823 (history of CVE), 62 049 (2 risk factors), and 128 691 (aged ≥40 years) patients were included. Among patients aged <65 years, 81.4% and 51.8% of those with history of CVE, 75.6% and 44.4% of those with 2 risk factors, and 77.9% and 47.1% of those aged ≥40 years had ≥1 and 2 treatment modification(s), respectively. Among all patients, 23.2–28.4% had possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues after accounting for second treatment modification (if any).

Conclusions

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with high cardiovascular disease risk, index statin treatment modifications that potentially imply possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness were frequent.

Keywords: Lipid-Lowering Drugs/Medication, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Cardiovascular Outcomes

Key messages.

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with high cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, index statin treatment modifications that potentially imply possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness were frequent.

Low use of high-intensity statin found in this study also indicates gaps in the management of hyperlipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes and possible remaining unaccounted lipid residual risk.

Better management of these patients with diabetes is warranted to reduce their CVD risk.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a primary cause of mortality and morbidity among patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 Patients with type 2 diabetes have a twofold to fourfold higher risk of cardiovascular events (CVEs) than patients without diabetes.2 In addition, type 2 diabetes patients with a history of CVD have an increased risk of recurrent events. Hence, high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes should be treated effectively to better manage cardiovascular risks.

Several studies have shown that lipid-lowering treatments (LLTs) such as statins are effective in reducing the risk of CVEs and total mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes.3–6 In a recent meta-analysis conducted by de Vries et al,2 patients with diabetes with CVD experienced reductions in relative risk with standard-dose and intensive-dose statins by an estimated 15% and 24%, respectively, for major CVEs or cerebrovascular events. According to the 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines, patients with type 2 diabetes are one of four statin benefit groups.7 Along with lifestyle recommendations, the 2015 American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of Care position statement for CVD and risk management recommended different statin intensity treatment for patients of different age groups and CVD risk factors.8

Despite the efficacy of statins reported in many studies, not all patients, based on their risk, can adequately control their low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) with the starting statin dose; therefore, treatment regimens may be modified. These modifications may include dose escalation, switches to different LLT agents, or augmentation with other LLTs.9 Some treatment modifications may potentially be indicative of statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness. There are no standardized definition or Food and Drug Administration (FDA) diagnostic criteria for statin intolerance.10 Typically, it is defined as the inability to use statins because of significant symptoms (muscle myalgia and gastrointestinal side effects) or elevated creatine kinase levels.10 Several national and international professional medical societies recommend rechallenge of statin treatments and/or switching to other LLT as possible management options for statin-associated muscle symptoms.11–15 The AHA/ACC 2013 guidelines indicate that therapy ineffectiveness is a less-than-anticipated therapeutic response to statin therapy in which upward titration of statin dose or combination therapy is considered.11 Statin treatment intolerance and/or ineffectiveness in the type 2 diabetes population could potentially result in residual elevated risk for costly CVEs. This study examined LLT modifications among high CVD risk patients with type 2 diabetes initiating statins and/or ezetimibe. This study also investigated how such modifications may be associated with possible treatment intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues.

Research design and methods

This was a retrospective cohort analysis using the IMS LifeLink PharMetrics Plus commercial claims from January 1, 2006 to June 30, 2012. This nationally representative, longitudinal database is comprised of managed care health plan information throughout the USA, with adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims of >150 million enrollees since 2006.16

Study population

Eligible patients were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes are provided in online supplementary appendix A) aged ≥18 years with >1 outpatient pharmacy claims for statins and/or ezetimibe from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2011 from the IMS LifeLink PharMetrics Plus data set. The initiation date of the first statin and/or ezetimibe was designated as the index date. The first statin associated with the index date was designated as the index statin. The second outpatient pharmacy claim for statins and/or ezetimibe had to be ≤6 months apart. All patients were required to have continuous health plan enrolment for ≥12 months preindex date (baseline period) and 12 months postindex date. The follow-up period for treatment patterns varied in length, from (and including) the index date to the end of continuous health plan eligibility or to the end of the study period (June 30, 2012), whichever occurred first.

Patients with ≥1 outpatient pharmacy claim for statin and/or ezetimibe in the 12 months prior to the first index statin and/or ezetimibe claim, and patients with medical claims indicating pregnancy or delivery (ICD-9 CM codes are provided in online supplementary appendix A) at any time during the baseline or follow-up period were excluded from the study. Also, patients with >2 different index statins on the index date were excluded. Patients with type 2 diabetes were stratified into the following three high CVD risk cohorts:

History of CVE: Patients with a history of CVEs, defined as ≥1 non-diagnostic medical claim (inpatient or outpatient) with a diagnosis or procedure code for myocardial infarction, unstable angina, ischemic stroke, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, or transient ischemic attack (ICD-9-CM codes are provided in online supplementary appendix A) during the baseline period;

Two risk factors: Patients with the following two risk factors: older age (men aged ≥45 years, women aged ≥55 years) and hypertension (diagnosis or antihypertensive medication)) but no history of CVE or other cardiovascular risk equivalent (CVRE) conditions other than type 2 diabetes during the baseline period. Excluded patients with other CVREs were defined as ≥1 non-diagnostic medical claim (inpatient or outpatient) with a diagnosis or procedure code for peripheral artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, ischemic heart disease, or stable angina (ICD-9 CM codes are provided in online supplementary appendix A). Owing to data limitation, other risk factors (eg, smoking status, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, etc) could not be accounted for in the study; and

Aged ≥40 years: Patients aged ≥40 years on the index date. This cohort includes a broader group of patients with type 2 diabetes but also encompasses patients in the two risk factors cohort.

These three cohorts were selected since these patient groups have been identified by several US national guidelines as high-risk populations for CV outcomes.8 12 17 18

Study outcomes

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in each cohort were examined. Initial statin intensity (low, moderate, high) was also recorded and stratified by index year for each cohort. Using average daily dose, definitions of different statin intensities were adapted from the 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines (see online supplementary appendix B). The average daily dose was defined as the strength of the statin multiplied by the dose quantity and divided by the total days of supply.

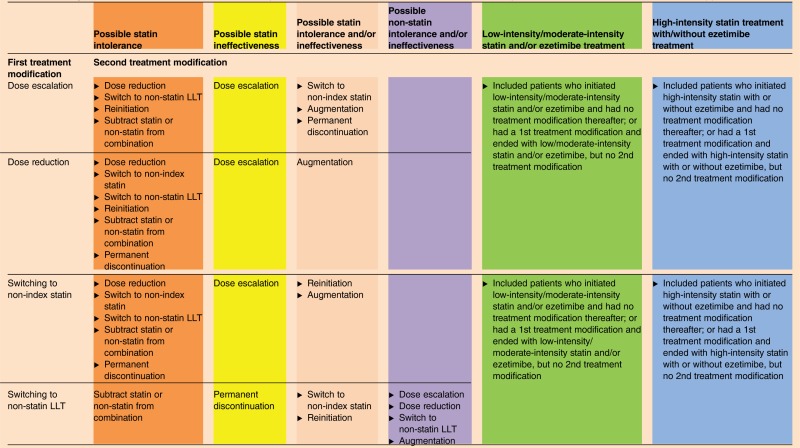

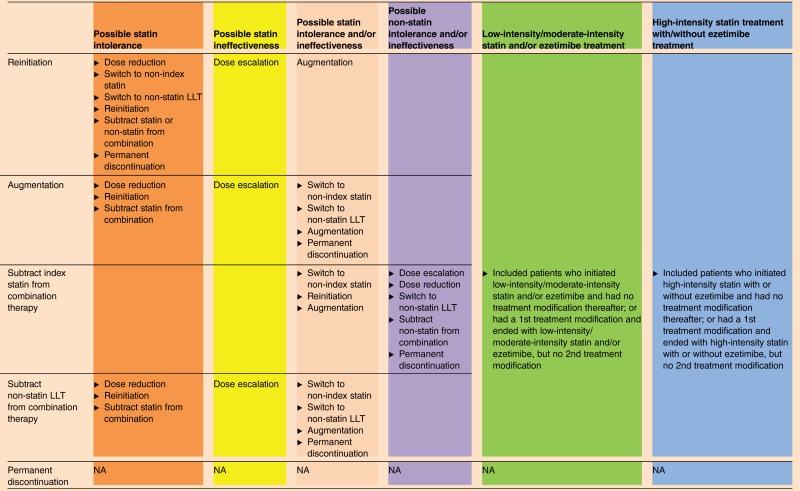

Treatment modification (none, first, and second) and time-to-treatment modification (days) during the follow-up period were captured. Treatment modifications are defined in table 1. Treatment modifications included dose escalation, dose reduction, augmentation, subtraction for patients receiving combination therapy, reinitiation of index therapy, switching, and permanent LLT discontinuation. Utilizing treatment modifications observed in claims data, patients with a first and/or second treatment modification were classified as possible statin intolerance, LLT intolerance, and statin/LLT intolerance and/or ineffectiveness (table 2). For example, statin dose reduction and temporary discontinuation followed by reinitiation of the same statin were considered as a signal for possible LLT intolerance.7 19 LLT ineffectiveness, as used in the present study, was defined in a similar way as the AHA/ACC 2013 guidelines (ie, a less-than-anticipated therapeutic response), and treatment modifications like dose escalation and augmentation with a non-statin LLT were considered as possible signals for LLT ineffectiveness. To increase the likelihood that the treatment modification(s) are associated with treatment intolerance and/or ineffectiveness, we categorized and accounted for both the observed first and second treatment modification(s) (if any), into possible LLT intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues, as defined in table 2. Patients with no treatment modification or those who had a first treatment modification but no second treatment modification were classified into low-intensity/moderate-intensity statin and/or ezetimibe or high-intensity statin treatment with/without ezetimibe treatment depending on their statin intensity and/or ezetimibe treatment.

Table 1.

Definitions of treatment modifications

| Treatment modification | Definition |

|---|---|

| Dose escalation | Continuation of index treatment with dose escalation of ≥25% between consecutive claims of statin |

| Dose reduction | Continuation of index treatment with dose reduction of ≥25% between consecutive claims of statin |

| Augmentation | Continuation of index treatment with addition of a new non-statin medication (or addition of a statin medication for those with ezetimibe as index treatment) |

| Subtraction | Moved from combination treatment to a subset of combination treatment/monotherapy within end of days’ supply plus 60-day grace period |

| Switch to non-index statin | Initiation of non-index statin postindex treatment date (termination of index statin treatment was assumed if days supply overlapped) |

| Switch to non-statin | Initiation of non-statin postindex treatment date |

| Reinitiation | Discontinuation of all components of index treatment and reinitiate index treatment after end of days supply plus 60-day grace period |

| Permanent discontinuation | Discontinuation of all components of index treatment through end of follow-up period |

Table 2.

Intensity of statin treatment and criteria used to define possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues for patients with and without treatment modification(s)

|

|

Colors denoting different categories correspond to the different colors used in figure 2.

LLT, lipid-lowering treatment; NA, not available.

Statistical analysis

All measures, including patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, LLT treatment modification patterns and possible associated intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues among the three cohorts were reported. Analyses for each cohort were stratified by age groups (<65 and ≥65 years) to investigate the impact (if any) of Medicare eligibility; since patients aged ≥65 years are primarily insured under Medicare Advantage. In addition, the Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index score was calculated for each patient; this widely published comorbidity index uses ICD-9-CM codes in claims databases to measure the severity of patients’ comorbidities.20 Means and SDs were reported for continuous variables. Relative frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical data. All analyses were performed with SAS, V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

A total of 6 063 446 patients had >1 pharmacy claim for statins and/or ezetimibe from January 1, 2007 to June 30, 2011 (see online supplementary appendix C). After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 136 854 patients were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during the baseline period. These patients were further categorized into history of CVE cohort (n=9823), two risk factors cohort (n=62 049), and aged ≥40 years cohort (n=128 691; see online supplementary appendix C).

Patient characteristics

The average patient age of the history of CVE and two risk factors cohorts was 59 years, whereas the aged ≥40 years cohort's average patient age was 57 years (table 3). Most patients in all three cohorts were men (history of CVE: 65.7%, two risk factors: 61.8%, aged ≥40 years: 55.4%). The majority of patients resided in the West or Northeast US regions and received coverage under preferred provider organization health plans. The mean (±SD) Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index score for patients in the history of CVE cohort was 3.2 (±1.9), two risk factors cohort was 1.6 (±1.2), and aged ≥40 years cohort was 1.8 (±1.4). Hypertension was the most common baseline comorbidity among patients in all three cohorts (table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with type 2 diabetes

| History of CVE |

Two risk factors |

Aged ≥40 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=9823 |

N=62 049 |

N=128 691 |

||||

| N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| Age (mean and SD) | 58.6 | 10.0 | 59.4 | 8.0 | 57.0 | 9.3 |

| Age by category | ||||||

| <65 | 7886 | 80.3 | 50 446 | 81.3 | 108 169 | 84.1 |

| ≥65 | 1937 | 19.7 | 11 603 | 18.7 | 20 522 | 15.9 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 6453 | 65.7 | 38 364 | 61.8 | 71 234 | 55.4 |

| US geographic distribution | ||||||

| Northeast | 3169 | 32.3 | 19 269 | 31.1 | 40 279 | 31.3 |

| North Central | 1876 | 19.1 | 16 332 | 26.3 | 32 970 | 25.6 |

| West | 4070 | 41.4 | 18 083 | 29.1 | 39 981 | 31.1 |

| South | 708 | 7.2 | 8365 | 13.5 | 15 461 | 12.0 |

| Payer type | ||||||

| Health maintenance organization | 1375 | 14.0 | 10 999 | 17.7 | 22 581 | 17.5 |

| Indemnity | 636 | 6.5 | 4055 | 6.5 | 7747 | 6.0 |

| Preferred provider organization | 6900 | 70.2 | 38 849 | 62.6 | 81 703 | 63.5 |

| Point of service | 898 | 9.1 | 7842 | 12.6 | 16 027 | 12.5 |

| Consumer-directed healthcare | 4 | 0.0 | 210 | 0.3 | 437 | 0.3 |

| Unknown/missing | 10 | 0.1 | 94 | 0.2 | 196 | 0.2 |

| Baseline Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index score categories20 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.4 |

| 0 | 6 | 0.1 | 225 | 0.4 | 469 | 0.4 |

| 1 | 1319 | 13.4 | 42 458 | 68.4 | 80 474 | 62.5 |

| 2 | 3367 | 34.3 | 6852 | 11.0 | 18 246 | 14.2 |

| ≥3 | 5131 | 52.2 | 12 514 | 20.2 | 29 502 | 22.9 |

| Baseline comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 8499 | 86.5 | 54 964 | 88.6 | 92 748 | 72.1 |

| Arrhythmias | 2786 | 28.4 | 3187 | 5.1 | 9846 | 7.7 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 2088 | 21.3 | 6203 | 10.0 | 15 269 | 11.9 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1837 | 18.7 | 1152 | 1.9 | 5052 | 3.9 |

| Carotid artery disease | 1535 | 15.6 | 718 | 1.2 | 3550 | 2.8 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1523 | 15.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 6428 | 5.0 |

| Cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) | 683 | 7.0 | 3708 | 6.0 | 7286 | 5.7 |

| End-stage renal disease | 231 | 2.4 | 352 | 0.6 | 1063 | 0.8 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 196 | 2.0 | 62 | 0.1 | 325 | 0.3 |

| Baseline concomitant medications | ||||||

| Antihypertensive medications | 6666 | 67.9 | 48 493 | 78.2 | 80 649 | 62.7 |

| Oral antidiabetic medications | 4581 | 46.6 | 36 235 | 58.4 | 71 040 | 55.2 |

| Insulin | 1613 | 16.4 | 7085 | 11.4 | 15 883 | 12.3 |

CVE, cardiovascular event.

More than 80% of patients in all three cohorts were aged <65 years (history of CVE: n=7886 (80.3%); two risk factors: n=50 446 (81.3%); aged ≥40 years: n=108 169 (84.1%)). Study results for those aged <65 years are reported below; similar patterns were also observed for patients aged ≥65 years.

Statin intensity from 2007 to 2011

Among patients aged <65 years in all three cohorts, 65.6–77.6% of patients initiated on a moderate-intensity statin and 7.7–25.2% initiated on a high-intensity statin; a similar trend was observed each year from 2007 to 2011.

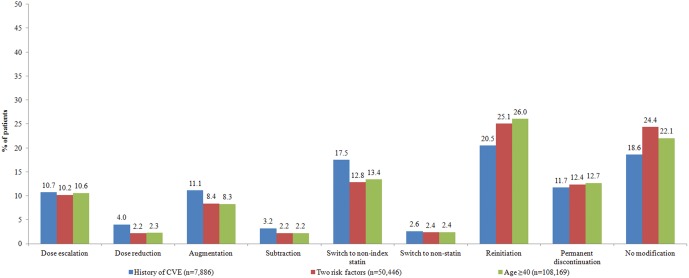

First treatment modifications

Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients with an initial treatment modification or no modification for all three cohorts, among patients aged <65 years. Of those, 81.4%, 75.6%, and 77.9% in the history of CVE, two risk factors, and aged ≥40 years cohorts, respectively, had at least one treatment modification. Reinitiation was the most frequent first treatment modification among patients in all three cohorts (history of CVE: 20.5%, two risk factors: 25.1%, aged ≥40 years: 26.0%) followed by switches to a non-index statin (history of CVE: 17.5%, two risk factors: 12.8%, aged ≥40 years: 13.4%). Similar treatment trends among patients aged ≥65 years are available in online supplementary appendix D.

Figure 1.

First treatment modification among patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events (CVEs; aged <65 years).

The average number of days to the first treatment modification among patients in all three cohorts ranged from 131 to 394 days. Among all cohorts, the average time-to-reinitiation was the longest (>1 year) whereas time-to-augmentation (<5 months) was the shortest.

Second treatment modification

In the history of CVE, two risk factors and aged ≥40 years cohorts, 51.8%, 44.4%, and 47.1% of patients aged <65 years, had at least a second treatment modification, respectively. Among those, reinitiation was the most common second treatment modification (history of CVE: 12.9%, two risk factors: 13.8%, aged ≥40 years: 14.8%). The average number of days from the index date to the second treatment modification across all three cohorts ranged from 379 to 607 days.

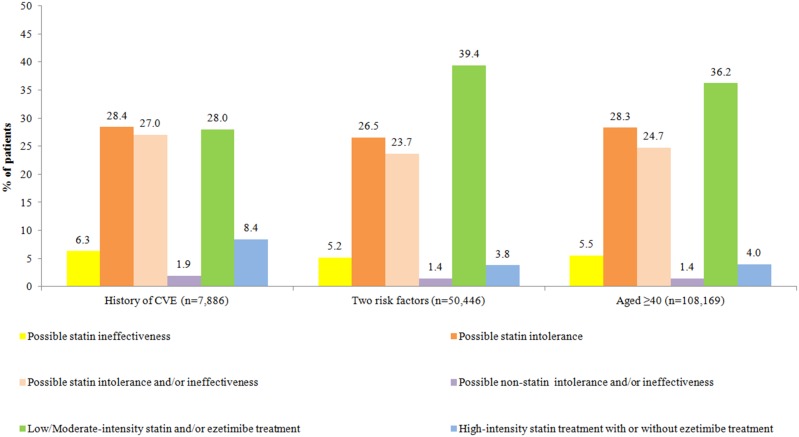

Statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues after accounting for second treatment modification (if any)

Based on the first and second treatment modification(s) (if any), possible LLT intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues, as defined in table 2, were characterized. In the history of CVE, two risk factors, and aged ≥40 years cohorts, 28.4%, 26.5%, and 28.3% were classified as having possible statin intolerance, respectively (figure 2). Possible statin ineffectiveness was observed among 5.2–6.3% of patients in all three cohorts. Also, possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues were associated with 23.7–27.0% among patients in all three cohorts. Possible non-statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues were observed among 1.4–1.9% of patients in all three cohorts. Similar treatment trends among patients aged ≥65 years are available in online supplementary appendix E.

Figure 2.

Intensity of statin treatment and possible lipid lowering treatment intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues among patients with type 2 diabetes (aged <65 years) at high risk for cardiovascular events (CVEs) with or without treatment modification(s). Note: Colors denoting different categories in table 2 correspond to the different colors used in this figure.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to utilize a real-world retrospective claims-based analysis to associate observed LLT modification(s) (if any) with possible treatment intolerance and/or ineffectiveness among patients with type 2 diabetes with high CVD risk. Our study showed that more than 70% of patients initiating statin and/or ezetimibe treatment had at least one treatment modification and more than 35% had at least two treatment modifications, implying that many patients initiating statin and/or ezetimibe experienced issues with their index and first treatment modification during the study period. As defined and categorized in our study, these treatment modification(s) are associated with >23% of patients having possible statin intolerance and possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues after accounting for the second treatment modification (if any).

ADA 2015 Standards of Care position statement recommended the need for high-intensity statin treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes with history of overt CVD.8 Although patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes represent a high-risk group (including all 3 cohorts in the present study), <26% across all three study cohorts were prescribed high-intensity index statins from 2007 to 2011. The low initiation rate of high-intensity statin among high CVD risk patients with type 2 diabetes suggests the need for better LLT management within this patient population. Additional research should utilize contemporary data to further understand the effects of the introduction of current guidelines.

Our study showed that 21–25% of patients with type 2 diabetes permanently discontinued all LLTs during the follow-up period. In a retrospective study conducted by Caspard et al,21 26% of patients discontinued treatment during the first year, and the probability of resuming statin treatment was 51% within 2 years after the last prescription fill. Simpson et al22 reported 46.9% of the patients in their study discontinued LLT 3 months after drug initiation during the 12 months follow-up period. Although the discontinuation rates vary among these studies, primarily due to the varying definitions of discontinuation and follow-up periods, these studies corroborate with other published studies that discontinuation was common among statin users.23–25 For some patients, adverse events associated with statin use (eg, musculoskeletal issues, peripheral neuropathy, insomnia, creatine kinase, and liver function test elevation) influence therapy decisions, thereby increasing the likelihood of statin therapy discontinuation.11 26–28 In a recent survey of self-reported former and current statin users, nearly two-thirds of patients (62%) discontinued statin use primarily because of side effects, most commonly muscle-related.29 Also, among current statin users who switched treatment, 28% said they switched due to the side effects, and 22% switched due to the lack of efficacy. These results suggest that treatment modifications may be associated with possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness. Patient registries along with observational studies showed a 7–29% prevalence of statin intolerance.22 24 28–31 After accounting for the second treatment modification (if any), our study showed that 23–28% of patients were identified with possible statin intolerance. The differences between previous studies and our study may be attributed to a number of factors, including statin intensity prescribed (high intensity vs any intensity),28 differences in patient selection (general population vs hyperlipidemic patients)31 and differences in possible statin intolerance identification (patient reported vs observed treatment modification).29

Previous studies of statin treatment patterns have focused on monotherapy, adherence or post-therapeutic substitution.32–34 Simpson et al22 concluded that high CVD risk patients were usually initiated on moderate-intensity statin which was similar to our findings, but, unlike our study which included combination treatment, Simpson's study was based on initiation of statin monotherapy. Harley et al34 followed patients after they were switched from simvastatin to other statins or combination of simvastatin and ezetimibe and found that most patients switching from higher doses of simvastatin switched to fixed-dose combination of simvastatin plus ezetimibe. However, none of these studies have put treatment modifications into perspective by critically analyzing and providing detailed classification of treatment modification and possible associated statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues.

To our knowledge, there is currently no existing validated claims-based algorithm to identify statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness issues among patients. Nevertheless, statin intolerance management, based on LLT modifications, have been mentioned in national and international guidelines.11–14 The National Lipid Association defines statin intolerance as a clinical syndrome characterized by the inability of a patient to tolerate statin therapy with statin challenge of ≥2 different statins.35 As part of the 2015 comprehensive diabetes management algorithm, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology recommends ‘try(ing) alternate statins, lowering statin dose or frequency, or adding non-statin LDL-C lowering therapies’ for statin intolerant patients.15 For patients showing symptoms of statin intolerance, the ACC/AHA,12 European Atherosclerosis Society,11 and Canadian Working Group Consensus14 also recommended similar LLT modification (eg, rechallenge, dose reduction, switch to other LLT). Based on these guideline definitions/recommendations, the present study utilized treatment modifications (eg, dose reduction, reinitiation) to connote possible statin intolerance and ineffectiveness. While adapting the mentioned statin intolerance treatment management recommendations, our claims-based analyses precluded us from providing definite reasons regarding treatment modifications. However, while accounting for up to two treatment modifications, our study results are indicative of possible associated statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness among patients included in study. We acknowledge that treatment modifications (or the lack of modification) may also be due to unobserved factors (eg, health system changes, modification in health plan formulary coverage, physician/clinical inertia). Further research (eg, the clinical chart review) is warranted to confirm our findings and explore causal links between statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness with specific LLT modifications to provide more definite conclusions.

Additional study limitations are due to the use of claims data, subject to potential coding, billing, and recording errors. The dispensed LLT prescription claims do not guarantee that patients actually took their medications as prescribed. The requirement for commercially insured patients with continuous medical and pharmacy coverage for 12 months before and after index date may have resulted in selection bias by eliminating patients who had <24 months of data. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other patient populations. Specific LDL-C levels data were not available in the data set to assess their impact on treatment modifications. Some treatment modifications may be indicative of patients achieving LDL-C targets, but this may represent a small proportion of patients36 since the study focused on patients with type 2 diabetes at high CVD risk. Nonetheless, previous studies that utilized specific LDL levels are limited in size or generalizability.7 21

Conclusions

Among patients with type 2 diabetes with high CVD risk, index statin treatment modifications that potentially imply possible statin intolerance and/or ineffectiveness were frequent. Low use of high-intensity statin found in this study also indicates gaps in the management of hyperlipidemia among patients with type 2 diabetes and possible remaining unaccounted lipid residual risk. Better management of these patients with diabetes is warranted to reduce their CVD risk.

Footnotes

Contributors: SRG and RGWQ participated in the design of the study, and provided data interpretation and critical review of the study results and manuscript. LW and LL participated in the design of the study, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and performed the statistical analysis. KMF and NDW participated in the study design, data interpretation, and critical review of the study results and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Amgen Inc.

Competing interests: SRG and RGWQ are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc. LW and LL are employees of STATinMED Research, which is a paid consultant to Amgen Inc. KMF is an employee of Strategic Healthcare Solutions, LLC, and is a paid consultant to Amgen Inc. NDW is a professor at the University of California, Irvine, and is a paid Amgen Inc consultant and advisory board participant.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Patient data were obtained from IMS LifeLink Pharmetrics Plus commercial claims database containing de-identified patient-level information.

References

- 1.Toth PP, Zarotsky V, Sullivan JM et al. Dyslipidemia treatment of patients with diabetes mellitus in a US managed care plan: a retrospective database analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2009;8:26 10.1186/1475-2840-8-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Vries FM, Kolthof J, Postma MJ et al. Efficacy of standard and intensive statin treatment for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in diabetes patients: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e111247 10.1371/journal.pone.0111247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376:1670–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandle M, Davidson MB, Schriger DL et al. Cost effectiveness of statin therapy for the primary prevention of major coronary events in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1796–801. 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012;380:581–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62027-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R et al. , Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008;371:117–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60761-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen V, deGoma EM, Hossain E et al. Updated cholesterol guidelines and intensity of statin therapy. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:357–9. 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association. Cardiovascular disease and risk management. Sec. 8. In standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38(Suppl 1):S49–57. 10.2337/dc15-S011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catapano AL. Perspectives on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal achievement. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:431–47. 10.1185/03007990802631438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad Z. Statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1765–71. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stroes ES, Thompson PD, Corsini A et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1012–22. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S1–45. 10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyton JR, Bays HE, Grundy SM et al. An assessment by the Statin Intolerance Panel: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol 2014; 8(3 Suppl):S72–81. 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancini GB, Baker S, Bergeron J et al. Diagnosis, prevention and management of statin adverse effects and intolerance: proceedings of a Canadian Working Group Consensus Conference. Can J Cardiol 2011;27:635–62. 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garver AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI et al. AACE/ACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015. Endocr Pract 2015;21:438–47. 10.4158/EP15693.CS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IMS Health. http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Home%20Page%20Content/Real-World%20insights/IMS_Lifelink_pharmetrics_Plus.pdf (accessed 2 Mar 2015).

- 17.Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology—Clinical Practice Guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015. Endocr Pract 2015;(Suppl 1);21:1–87. 10.4158/EP15672.GLSUPPL [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson TA, Ito MK, Maki KC et al. National lipid association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 1-full report. J Clin Lipidol 2015;9:129–69. 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escobar C, Echarri R, Barrios V. Relative safety profiles of high dose statin regimens. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2008;4:525–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–19. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caspard H, Chan AK, Walker AM. Compliance with a statin treatment in a usual-care setting: retrospective database analysis over 3 years after treatment initiation in health maintenance organization enrollees with dyslipidemia. Clin Ther 2005;27:1639–46. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson RJ Jr, Tunceli K, Ramey DR et al. Treatment pattern changes in high-risk patients newly initiated on statin monotherapy in a managed care setting. J Clin Lipidol 2013;7:399–407. 10.1016/j.jacl.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care setting. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:526–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chodick G, Shalev V, Gerber Y et al. Long-term persistence with statin treatment in a not-for-profit health maintenance organization: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Israel. Clin Ther 2008;30:2167–79. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degli Esposti L, Saragoni S, Batacchi P et al. Adherence to statin treatment and health outcomes in an Italian cohort of newly treated patients: results from an administrative database analysis. Clin Ther 2012;34:190–9. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G et al. , European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–818. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva MA, Swanson AC, Gandhi PJ et al. Statin-related adverse events: a meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2006;28:26–35. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S et al. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients—the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2005;19:403–14. 10.1007/s10557-005-5686-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK et al. Understanding statin use in America and gaps in patient education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol 2012;6:208–15. 10.1016/j.jacl.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker BA, Capizzi JA, Grimaldi AS et al. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle function. Circulation 2013;127:96–103. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.136101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buettner C, Rippberger MJ, Smith JK et al. Statin use and musculoskeletal pain among adults with and without arthritis. Am J Med 2012;125:176–82. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kern DM, Balu S, Tuncelli O et al. Statin treatment patterns and clinical profile of patients with risk factors for coronary heart disease defined by National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman RH, Benner JS, Girase P et al. Generic and therapeutic statin switches and disruptions in therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1247–60. 10.1185/03007990902876271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harley CR, Gandhi SK, Anoka N et al. Understanding practice patterns and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment implications of switching patients from simvastatin in a health plan setting. Am J Manag Care 2007;13(Suppl 10):S276–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bays HE, Jones PH, Brown WV et al. National Lipid Association annual summary of clinical lipidology 2015. J Clin Lipidol 2014;8:S1–36. 10.1016/j.jacl.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Health Report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 2014;63:3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]