Abstract

Background and Aims:

Extrahepatic biliary atresia is one of the most challenging conditions in pediatric surgery. The definition of prognostic factors is controversial. Surgical outcomes after bilioenteric drainage procedures are variable. This study attempts to correlate the pre- and post-operative liver histology with clinical factors in order to define early predictors of success.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty consecutive patients, treated by Kasai's portoenterostomy (KP) over a 3 years period were included in this study. Tissue obtained from the porta hepatis was analyzed for duct size using an optical micrometer and was categorized into three types: I-No demonstrable ducts; II - <50 μ; III - >50 μ. Pre- and post-operative liver biopsy was analyzed for architectural changes and fibrosis; hepatic fibrosis was quantified using existing criteria. Pre- and post-operative liver function tests (LFTs) were also done. Surgical outcomes were defined as: (A) Disappearance of jaundice within 3 months; (B) initial disappearance of jaundice with recurrence by 6 months and (C) persistence of jaundice. Duct diameters, fibrosis score, and LFT were correlated with age and clinical outcomes.

Results:

The surgical outcomes were: A-6 patients (30%), B-6 patients (30%), C-8 patients (40%). The duct size at the porta was I-3 patients, II-11 patients, and III-4 patients (tissue was not available in 2 cases). The change in total serum bilirubin (mg%) from pre- to post-operative period was 13.6 ± 3.9 (Group A), 4.6 ± 2.8 (Group B), and 3.4 ± 3.9 (group C) (P < 0.001) and direct and indirect fractions followed a similar trend; the changes in liver enzymes were not significant. The changes in hepatic histopathological changes (ballooning of hepatocytes, giant cells, cholestasis, portal tract infiltration, ductular proliferation, lobular necrosis, and fibrosis) were also not significant but there was a definite trend in the change in fibrosis -1.500 ± 1.643 (Group A), 0.667 ± 2.582 (Group B), and 1.500 ± 1.852 (Group C) - reduction of fibrosis with good results and progression of fibrosis with poor results.

Conclusions:

Following KP, jaundice persisted in 40% patients; it disappeared in 60% patients but reappeared in half of these patients 6 months postoperatively. The duct size at the porta hepatis did not correlate with age or surgical outcome. Serum bilirubin showed the best correlation with surgical outcome. Postoperative changes in hepatic fibrosis seem to have some bearing on surgical outcomes-progressive fibrosis is a poor prognostic factor.

KEY WORDS: Extrahepatic biliary atresia, hepatic fibrosis, Kasai's portoenterostomy, liver biopsy, liver function test

INTRODUCTION

Extrahepatic biliary atresia (EHBA) is a challenge to pediatric surgeons. It results from a destructive sclerosing inflammatory process of the extrahepatic bile ducts and causes complete obstruction to bile flow. Untreated biliary atresia ends in chronic liver disease with obliteration of intrahepatic bile ducts progressing into biliary cirrhosis; there are no survivors by 2 years of age.[1,2] The role of various factors believed to be important for a successful outcome has been debated and these include age at operation, size of bile ductules, degree of liver fibrosis, and the need for external vents or anti-reflux conduits. The intraoperative identification of prognostic factors is limited by a lack of established criteria. In this study, an attempt has been made to correlate the morphological features of liver biopsy specimens and tissue from the porta hepatis taken at the time of Kasai's portoenterostomy procedure (KP) and postoperative liver biopsy specimens of survivors with clinical factors in order to determine the prognostic factors in the first 6 months after surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This prospective study was conducted on 20 patients with EHBA, diagnosed by preoperative ultrasonography, hepatobiliary scintigraphy, and operative cholangiography and treated by KP over a 3 years period in the Department of Pediatric Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi. There were 12 males and 8 females. The age distribution was up to 1 month n = 1, 1-2 months n = 10, 2-3 months n = 8, and >3 months n = 1. All operative procedures were performed by the same senior surgeon (VB). Postoperative cases were divided into three groups according to their clinical outcome at 6 months after surgery based on clinical findings:

Group A (Good): Patients in whom the jaundice cleared by 3 months following KP.

Group B (Fair): Patients in whom jaundice cleared by 3 months following KP but re-appeared before 6 months postoperatively in the absence of cholangitis.

Group C (Poor): Patients who survived the surgery, but in whom the jaundice never cleared.

Wedge biopsy specimen of liver and tissue excised from the porta hepatis during KP, as well as postoperative liver biopsy specimens obtained by Tru-Cut needle were made into 5 μ sections and subjected to histopathological examination. The Tru-Cut needle biopsies were taken at 6 months after KP. All histopathological specimens were reviewed by the same senior pathologist (SDG) who was blinded to the clinical results. The following staining techniques were employed: Hematoxylin and Eosin, Masson's Trichrome, reticulin, and diastase. The stained sections were examined under light microscopy. Diagnostic criteria and a grading system available in the literature were used to evaluate the histological features.[3,4]

The ducts at the porta were classified into three types, according to the diameter of the ducts.[3] An optical micrometer was used to measure the internal diameter of the ducts. The mean of three measurements for each structure was taken. The grading was as follows:

Grade I: No demonstrable ducts

Grade II: Duct size <50 μ

Grade III: Duct size >50 μ

Histopathological examination of the liver biopsy specimens included ballooning of hepatocytes, presence of giant cells, cholestasis (cellular, canalicular, and ductular), cellular infiltration of portal tracts, ductular proliferation, lobular necrosis, and fibrosis. The fibrosis was evaluated in detail and it was scored according to existing criteria[5,6] as follows:

0: No fibrosis

1: Fibrous expansion of some portal areas, with or without short fibrous septa

2: Fibrous expansion of most portal areas, with or without short fibrous septa

3: Fibrous expansion of most portal areas with occasional portal to portal (P-P) bridging

4: Fibrous expansion of most portal areas with marked portal to portal (P-P) bridging as well as portal to central (P-C) bridging

5: Marked bridging (P-P and/or P-C) with occasional nodules (incomplete cirrhosis)

6: Cirrhosis, probable or definite

Preoperative liver function tests (LFTs) for review in this study included serum bilirubin, transaminases (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase,) and alkaline phosphatase. Postoperatively these were repeated 6 months after KP.

The clinical outcomes were correlated with ductular size, hepatic fibrosis, and LFTs. The statistical analysis was done using STATA 9.0 (College Station, Texas, USA) and appropriate tests of significance were used where applicable; a P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Tissue from the porta hepatis was not available in 2 patients. Hence, this was evaluated in 18 patients only. In 3 patients there were no ducts, in 11 patients the ducts were <50 μ (23.6-48.9 μ) and in the remaining 4 patients the ducts were >50 μ (50.0-209.0 μ).

The postoperative clinical outcome was good in 6 patients, fair in 6 patients, and poor in 8 patients.

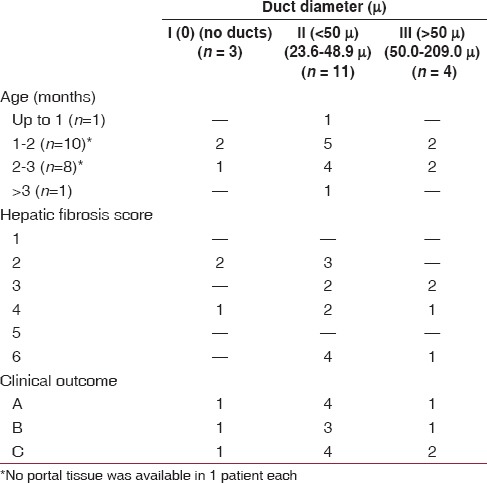

The details of the histopathological examination of the tissue from the porta hepatis in relation to age, hepatic fibrosis score, and clinical outcome are presented in Table 1. The distribution was not statistically significant. However, the majority of patients with ducts were seen in the 1-3 months age groups (13 of 18 patients). The severity of hepatic fibrosis was independent of the duct size at the porta hepatis. The clinical outcome also did not depend on the duct size at the porta hepatis.

Table 1.

Histopathological examination of tissue from the porta hepatis

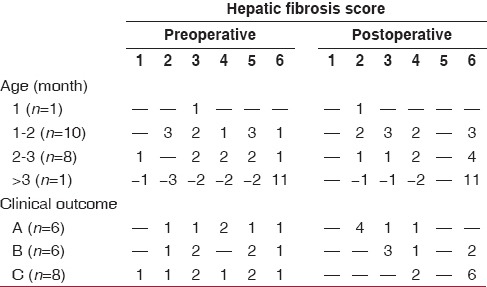

The details of hepatic fibrosis in pre- and post-operative liver biopsies in relation to age and clinical outcome are presented in Table 2. The distribution of patients was not statistically significant. Almost all patients had some degree of fibrosis. Biliary cirrhosis was present in only 3 patients preoperatively, but postoperatively the fibrosis progressed to biliary cirrhosis in 5 other patients. However, a few patients also showed a reduction in the degree of fibrosis. Thus, it is clear that hepatic fibrosis is a dynamic process; in some patients the fibrosis reduced while in others it was progressive. There was no correlation between the clinical outcome and the score of hepatic fibrosis. The existence of fibrosis at the time of KP does not seem to affect the early results of surgery, although there seems to be a trend toward poorer outcomes with higher degrees of fibrosis.

Table 2.

Pre- and post-operative hepatic fibrosis in liver biopsies

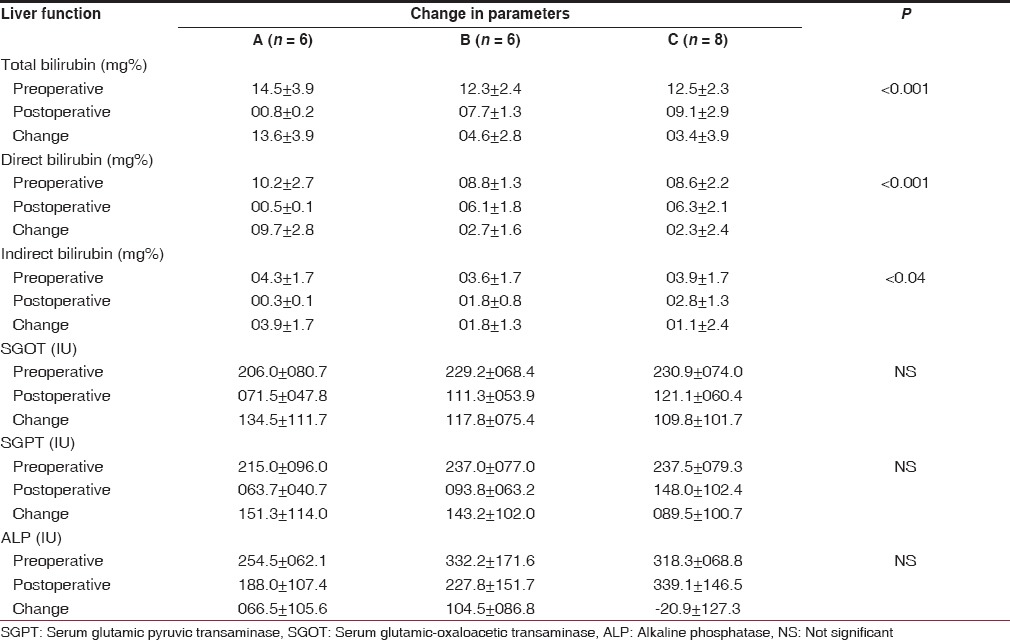

The details of pre- and post-operative LFTs have been presented in Table 3. There was a significant reduction in the postoperative serum bilirubin (total, direct and indirect) as compared to the preoperative levels. The change between pre- and post-operative bilirubin levels when compared among the three outcome groups was also found to be statistically significant. As expected, the decrease was highest in Group A and the least in Group C for total, direct and indirect serum bilirubin (P < 0.001, 0.001 and <0.04 respectively). Thus, the establishment of bilioenteric drainage and its effectiveness determines whether the clinical outcome is good, fair or poor. This pattern was also evident in the changes in the levels of alkaline phosphatase; in Groups A and B the postoperative levels were lower than the preoperative levels but in Group C this pattern was reversed. However, the changes between the three groups did not reach statistical significance. The transaminases also showed a decrease in the postoperative levels, but the differences in the changes between the three groups did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Comparison of liver function between groups A, B, C

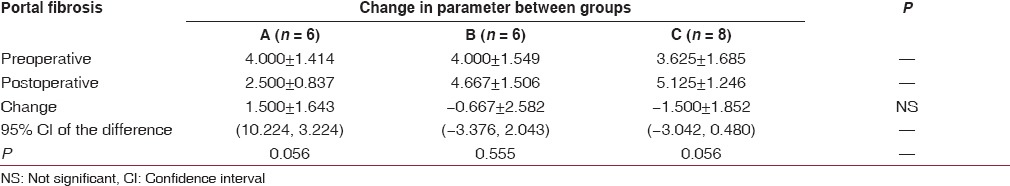

The various histological parameters (ballooning of hepatocytes, presence of giant cells, cholestasis, portal inflammation, ductular proliferation, and lobular necrosis) were compared in the pre- and post-operative biopsies and within the three clinical outcome groups. There was no statistically significant difference and there did not seem to be any pattern in the distribution with regard to ballooning of hepatocytes, presence of giant cells, and lobular necrosis. Increasing cholestasis, portal inflammation, and ductular proliferation seemed to accompany worsening of clinical outcome. However, portal fibrosis was seen to reduce almost significantly in Group A patients postoperatively (P = 0.056), in Group B patients it showed a slight increase and in Group C patients the increase in postoperative fibrosis was almost significant (P = 0.056). However, the change in the severity of fibrosis between the three groups was not statistically significant. Among the various histological parameters studied, the severity of portal fibrosis and its progression seemed to be the only parameter which affected the clinical outcome [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of portal fibrosis score between groups A, B, C

DISCUSSION

The current management of EHBA follows the principle that bile drainage may be established from residual microscopic channels in the tissue at the porta hepatis.[5] Many studies have reported prognostic factors for clinical outcome after hepatic portoenterostomy. Histopathological features of the ductal remnants at the porta hepatis and the liver have been correlated with the clinical outcome of the patients. The presence of microscopically demonstrable ducts in the porta hepatis and the duct size has been reported to be important, but this is not universally accepted.[1,3,6,7] This study explores the possibility of determining early indicators of prognosis in the first 6 months after surgery.

In this study, there was no correlation between duct size and clinical outcome. Some of the patients with bigger ductules had a poor clinical outcome and some patients with no ductules in the porta had a good clinical outcome.

It has been universally believed that duct size is inversely proportional to the age at surgery that is, younger infants have larger ducts.[8,9] However, several studies have disputed this correlation between age and duct size.[3] This study also did not show any correlation between age and duct size. In the group of patients aged 2 months or less, 8 of 10 (80%) patients either showed no ducts or ducts smaller than 50 μ. The number of infants with ducts larger than 50 μ was similar (75%) in the age group more than 2 months. Therefore, age in isolation should not be used as a criterion to determine prognosis.

Parameters of hepatic histopathological features have also been used to determine prognosis. Parenchymal degeneration and giant cell transformation have been reported to be associated with early death.[10] However, in another study no prognostic significance could be attributed to fibrosis, inflammation, and giant cells.[1] In this study, the histopathological parameters studied included ballooning of hepatocytes, presence of giant cells, cholestasis, inflammatory infiltration, lobular necrosis, and portal fibrosis. Except for portal fibrosis none of the other parameters had any significance in determining prognosis in the first 6 months after surgery.

The histopathological findings on postoperative liver biopsy have been reported as an important predictor of long-term prognosis.[11,12,13,14] Reduction of fibrosis has been reported with establishment of good biliary drainage and older infants tend to have greater fibrosis and this in turn leads to poor prognosis. Progression of fibrosis is also a poor prognostic sign. In the present study, it was evident that hepatic fibrosis was a dynamic process and that good clinical outcomes resulted in a reduction of fibrosis and increase in fibrosis accompanied poor clinical outcomes. The severity of hepatic fibrosis in the postoperative period was found to be independent of duct size at the porta.

The reduction in the levels of serum bilirubin is an obvious indicator of clinical outcome as seen in this study. With good clinical outcome, the levels of transaminases and alkaline phosphatase also show a fall which may not be seen with poor outcome.

In 1975, Kasai et al. stated that a successful operative drainage might halt the proliferation of bile ducts and lead to improvement in hepatic architecture. They stressed on the importance of the following prognostic factors:

Age at operation,

Size of bile ductules.

Degree of fibrosis in the liver.[15]

In this study, the age at surgery and duct size do not seem to have any influence on the early outcome of surgery, although changes in hepatic fibrosis during this period does indicate a prognostic significance. A longer study will be required to establish whether the early predictors of good outcomes may have any role in predicting long-term prognosis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chandra RS, Altman RP. Ductal remnants in extrahepatic biliary atresia: A histopathologic study with clinical correlation. J Pediatr. 1978;93:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gautier M, Jehan P, Odièvre M. Histologic study of biliary fibrous remnants in 48 cases of extrahepatic biliary atresia: Correlation with postoperative bile flow restoration. J Pediatr. 1976;89:704–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)80787-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatnagar V, Singh MK, Mitra DK. Bile duct diameter at the porta hepatis and liver biopsies in Indian children with biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int. 1994;9:558–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasai M. Treatment of biliary atresia with special reference to hepatic porto-enterostomy and its modifications. Prog Pediatr Surg. 1974;6:5–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyano T, Suruga K, Tsuchiya H, Suda K. A histopathological study of the remnant of extrahepatic bile duct in so-called uncorrectable biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(77)90291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence D, Howard ER, Tzannatos C, Mowat AP. Hepatic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia.A comparative study of histology and prognosis after surgery. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:460–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.56.6.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai M, Ohi R, Chiba T. Intrahepatic bile ducts in biliary atresia. In: Kasai M, Shiraki K, editors. Cholestasis in Infancy. Baltimore, M.D: University Park Press; 1980. pp. 181–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan CE, Davenport M, Driver M, Howard ER. Does the morphology of the extrahepatic biliary remnants in biliary atresia influence survival?. A review of 205 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1459–64. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vazquez-Estevez J, Stewart B, Shikes RH, Hall RJ, Lilly JR. Biliary atresia: Early determination of prognosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:48–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(89)80300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karrer FM, Lilly JR, Stewart BA, Hall RJ. Biliary atresia registry, 1976 to 1989. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:1076–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90222-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tagge DU, Tagge EP, Drongowski RA, Oldham KT, Coran AG. A long-term experience with biliary atresia. Reassessment of prognostic factors. Ann Surg. 1991;214:590–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199111000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang N, Davenport M, Driver M, Howard ER. Hepatic histology and the development of esophageal varices in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:63–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suruga K, Miyano T, Arai T, Ogawa T, Sasaki K, Deguchi E. A study of patients with long-term bile flow after hepatic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:252–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(85)80115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasai M, Watanabe I, Ohi R. Follow-up studies of long term survivors after hepatic portoenterostomy for “noncorrectible” biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1975;10:173–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(75)90275-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]