A glycolate oxidase metabolizes l-lactate to pyruvate in vivo and may ensure the maintenance of low levels of l-lactate after its formation under normoxia.

Abstract

In roots of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), l-lactate is generated by the reduction of pyruvate via l-lactate dehydrogenase, but this enzyme does not efficiently catalyze the reverse reaction. Here, we identify the Arabidopsis glycolate oxidase (GOX) paralogs GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 as putative l-lactate-metabolizing enzymes based on their homology to CYB2, the l-lactate cytochrome c oxidoreductase from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We found that GOX3 uses l-lactate with a similar efficiency to glycolate; in contrast, the photorespiratory isoforms GOX1 and GOX2, which share similar enzymatic properties, use glycolate with much higher efficiencies than l-lactate. The key factor making GOX3 more efficient with l-lactate than GOX1 and GOX2 is a 5- to 10-fold lower Km for the substrate. Consequently, only GOX3 can efficiently metabolize l-lactate at low intracellular concentrations. Isotope tracer experiments as well as substrate toxicity tests using GOX3 loss-of-function and overexpressor plants indicate that l-lactate is metabolized in vivo by GOX3. Moreover, GOX3 rescues the lethal growth phenotype of a yeast strain lacking CYB2, which cannot grow on l-lactate as a sole carbon source. GOX3 is predominantly present in roots and mature to aging leaves but is largely absent from young photosynthetic leaves, indicating that it plays a role predominantly in heterotrophic rather than autotrophic tissues, at least under standard growth conditions. In roots of plants grown under normoxic conditions, loss of function of GOX3 induces metabolic rearrangements that mirror wild-type responses under hypoxia. Thus, we identified GOX3 as the enzyme that metabolizes l-lactate to pyruvate in vivo and hypothesize that it may ensure the sustainment of low levels of l-lactate after its formation under normoxia.

Lactate is a small α-hydroxy acid that exists in two stereoisomeric forms, d- and l-lactate. In eukaryotes, d-lactate is formed in the glyoxalase detoxification pathway that serves to remove the highly reactive and toxic compound methylglyoxal (Kalapos, 1999; Dolferus et al., 2008). This has been shown for plants and yeast as well as mammals (Thornalley, 1990; Engqvist et al., 2009). In contrast, l-lactate is typically generated by the enzymatic reduction of pyruvate. l-Lactate is an important intermediate in the process of wound repair and regeneration and a particularly mobile fuel for aerobic metabolism in mammals (Gladden, 2004). Its production is enhanced in response to low-oxygen conditions in plants (Sweetlove et al., 2000; Mustroph et al., 2014), some yeast species (Guiard, 1985; Alberti et al., 2000; Mowat and Chapman, 2000), and mammals (Everse and Kaplan, 1973; Grad et al., 2005; Holmes and Goldberg, 2009). The interconversion of l-lactate and pyruvate is a redox reaction that involves electron transfer and, therefore, necessitates a redox partner such that when l-lactate is oxidized to pyruvate, the redox partner is reduced. Different types of redox partners have different affinities for the electrons. This, in turn, affects the thermodynamics of the reaction and influences its directionality.

NAD+, the canonical redox partner of lactate, has a relatively low affinity for electrons. When used as a redox partner, as by the enzyme l-lactate:NAD oxidoreductase (EC 1.1.1.27), the reaction occurs largely in the direction of the formation of l-lactate through the reduction of pyruvate (Halprin and Ohkawara, 1966). In contrast, oxygen has very high affinity for electrons. When oxygen is used as a redox partner, as for the enzyme 2-hydroxy-acid oxidase (EC 1.1.3.15), the reaction is overwhelmingly toward the consumption of l-lactate to generate pyruvate. Cytochrome c can also be used as a redox partner for l-lactate-to-pyruvate interconversion, as in the case of l-lactate cytochrome c oxidoreductase (EC 1.1.2.3; Jacq and Lederer, 1974). The affinity of cytochrome c for electrons lies in between the affinity of NAD+ and oxygen (Alberty, 2004).

The directionality of these different redox reactions is used by some organisms to modify their physiological responses to changing conditions. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae uses an NAD+-dependent lactate dehydrogenase (l-LDH; EC 1.1.1.27) to produce l-lactate from pyruvate during microoxic conditions, making use of the reaction equilibrium toward lactate production. When oxygen is no longer limiting, S. cerevisiae can switch to consuming l-lactate using CYB2, a cytochrome c-dependent dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.2.3), in a reaction where the equilibrium is toward pyruvate production (Guiard, 1985). CYB2 is localized in the mitochondrial intermembrane space, and its expression is transcriptionally regulated by the carbon source; it is repressed by Glc and induced by ethanol and l-lactate (Guiard, 1985; Ramil et al., 2000).

Plants experience microoxic conditions (hypoxia) in roots during waterlogging (Bailey-Serres et al., 2012). Plants respond to these conditions by producing ethanol and l-lactate through fermentation. The enzyme responsible for l-lactate production has been identified as l-LDH (Paventi et al., 2007; Dolferus et al., 2008; Passarella et al., 2008). The gene encoding l-LDH in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; LDH1; At4g17260) is necessary for l-lactate production, and the loss-of-function mutant shows reduced root biomass accumulation in hypoxic conditions (Dolferus et al., 2008). The phenotype, however, is fairly mild, as Arabidopsis plants can excrete lactate into the surrounding medium when it begins to accumulate to higher amounts in root tissues (Dolferus et al., 2008). This excretion is facilitated by NODULIN26-LIKE INTRINSIC PROTEIN2;1 (NIP2.1; At2g34390), a lactate transporter that is highly sensitive to anaerobiosis (Choi and Roberts, 2007). In roots of plants subjected to waterlogging, transcript levels of NIP2.1 increase rapidly and intensely during the first 1 h of hypoxia (Choi and Roberts, 2007).

Although being crucial for l-lactate production, Arabidopsis l-LDH does not remove l-lactate from the medium. l-LDH loss-of-function mutants take up and metabolize l-lactate at the same rate as wild-type plants (Dolferus et al., 2008), indicating that another enzyme is involved in l-lactate metabolism in plants. The identity of this enzyme is still unknown. l-Lactate is not only produced in roots under hypoxia. Significant amounts of l-lactate are also present in roots of aerobically grown plants (Dolferus et al., 2008). Similarly, in mammalian tissues, l-lactate is an aerobic metabolite in the presence of an adequate oxygen supply and utilization of Glc or glycogen as a fuel (Gladden, 2004). In plants, aerobic l-lactate production is due to a basal expression level of l-LDH, as demonstrated by northern-blot analysis and GUS reporter lines, and by a basal l-LDH activity (Dolferus et al., 2008), indicating the necessity of the existence of housekeeping mechanisms to sustain l-lactate at low cellular levels in plants growing aerobically.

The gene family of l-2-hydroxy acid oxidases (l-2-HAOX) encodes members that exhibit l-lactate oxidase activity (Esser et al., 2014). Glycolate oxidase (GOX), a crucial enzyme of plant photorespiration, belongs to the l-2-HAOX family. Interestingly, Arabidopsis possesses three GOX paralogs: GOX1 (At3g14420), GOX2 (At3g14415), and GOX3 (At4g18360). In addition to GOX, the Arabidopsis l-2-HAOX family also includes the long-chain hydroxy acid oxidase1 (lHAOX1; At3g14130) and lHAOX2 (At3g14150; Esser et al., 2014).

In this work, we hypothesize that one of the Arabidopsis GOXs may fulfill the physiological role of converting l-lactate back to pyruvate. We test this hypothesis by biochemically characterizing the three Arabidopsis GOXs, GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3. We expressed these enzymes recombinantly in Escherichia coli and determined their substrate specificities, kinetic constants, and cofactor identities. All three enzymes accept both glycolate and l-lactate as substrates and use oxygen as a redox partner. Furthermore, while GOX1 and GOX2 are mostly involved in photorespiration, we make use of loss-of-function mutants, complementation assays, isotope tracer experiments, and metabolite profiling to indicate a role of GOX3 in supporting the metabolism of l-lactate in roots.

RESULTS

Identification of CYB2 Homologs in Arabidopsis

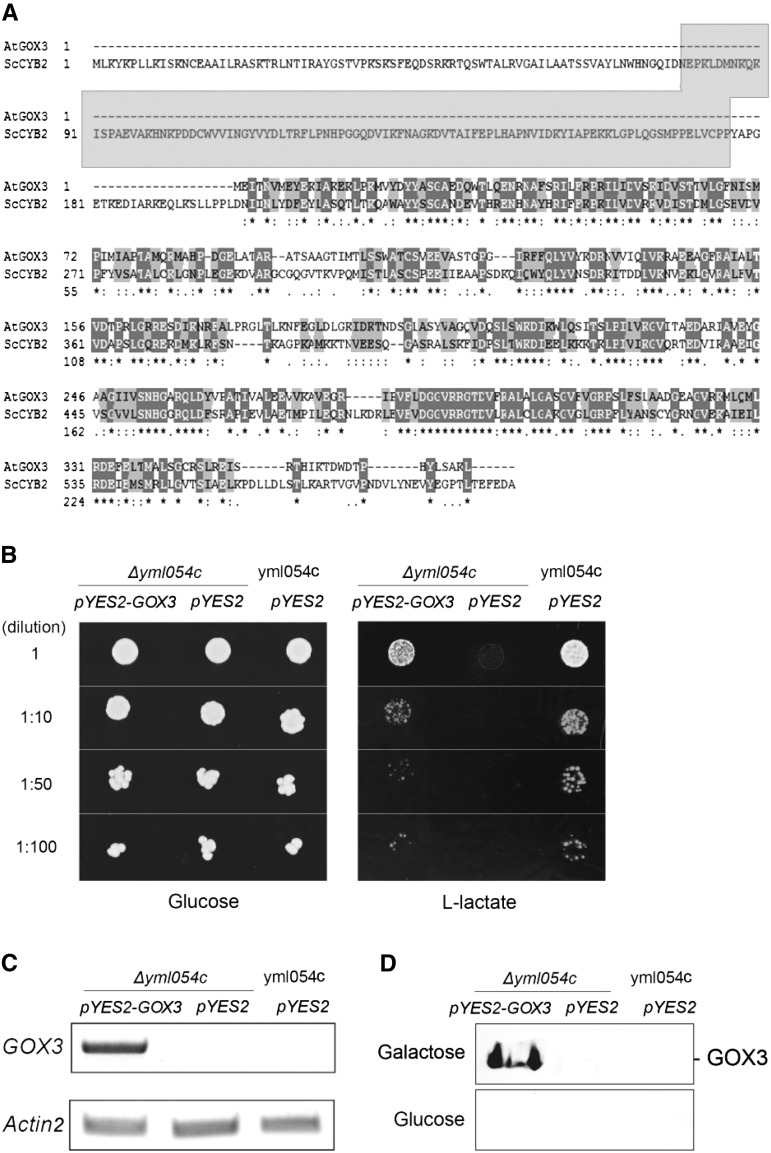

In S. cerevisiae, l-lactate is produced during anoxia, and upon reoxygenation, CYB2 is induced and metabolizes l-lactate to pyruvate. We hypothesized that the l-lactate-consuming enzyme in Arabidopsis may be homologous to CYB2. To investigate whether any CYB2 homologs exist in Arabidopsis, we performed a search using BLAST and employing the CYB2 protein sequence (UniProt no. P00175) as bait. This resulted in five top hits that were all paralogs belonging to the l-2-HAOX family. The hits were GOX1, GOX2, GOX3, lHAOX1, and lHAOX2. These five proteins all showed over 35% identity to the CYB2 catalytic domain (starting at amino acid 203), whereas they completely lacked any homology to the heme-binding domain of CYB2 (Fig. 1A), indicating that these enzymes may use a different electron acceptor than heme. Furthermore, all five l-2-HAOX proteins are predicted to localize to peroxisomes, as they contain a canonical peroxisomal targeting signal (PTS1; Esser et al., 2014). Proteome analyses of peroxisomes have confirmed the peroxisomal localization of GOX1, GOX2, and HAOX1 (Reumann et al., 2007, 2009).

Figure 1.

Functional complementation of yeast deficient in l-lactate CYB2 with GOX3. A, Alignment of S. cerevisiae CYB2 (ScCYB2) with Arabidopsis GOX3 (AtGOX3). The gray area shows the cytochrome c-binding domain of CYB2. B, Yeast growth assay. The following yeast strains were grown to early-log phase, and serial dilutions were spotted on medium containing 2% Glc or l-lactate as the sole carbon source: yml054c, yeast strain with intact CYB2 (wild type); Δyml054c, yeast strain with a loss of function of CYB2. pYES2, Empty vector; pYES2-GOX3, vector used to overexpress GOX3. C, Amplification of GOX3 transcripts using semiquantitative PCR in the different yeast lines. D, In-gel activity assay using l-lactate as the substrate of protein extracts from the different yeast lines grown in 2% Gal or Glc.

GOX1 and GOX2 are predicted to use glycolate as the main substrate (Esser et al., 2014) and support photorespiration, since their genes are highly expressed in photosynthetic tissues (Kamada et al., 2003). lHAOX1 and lHAOX2 are mainly expressed in seeds at different developmental stages (Arabidopsis eFP Browser; http://www.bar.utoronto.ca/). The enzymes possess different specificities for medium- and long-chain hydroxy acids and are likely involved in fatty acid and protein catabolism (Esser et al., 2014). The last paralog, GOX3, has extremely low expression in autotrophic tissues (Kamada et al., 2003), and it is predominantly expressed in roots as well as in senescent leaves (Arabidopsis eFP Browser). The physiological function of this enzyme in heterotrophic organs is not known, but based on its homology to CYB2 and its expression in roots, we considered GOX3 as a candidate enzyme that may predominantly oxidize l-lactate in plants.

Complementation of a Yeast Strain Deficient in l-Lactate Cytochrome c Reductase by GOX3 Expression

To test whether GOX3 has the catalytic activity to convert l-lactate to pyruvate in vivo, we performed a complementation assay. An S. cerevisiae loss-of-function mutant of CYB2 (Δyml054c-pYES2) is indistinguishable from the wild type (yml054c-pYES2) on Glc medium but cannot grow on l-lactate as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1B). To test if GOX3 can complement the mutant phenotype, GOX3 was overexpressed in Δyml054c (Δyml054c-pYES2-GOX3). A semiquantitative PCR analysis confirmed the presence of GOX3 transcripts in the complemented Δyml054c strain, while GOX3 transcripts were not amplified in Δyml054c and yml054c transformed with the empty vector (Fig. 1C). Using a native PAGE assay, only the complemented yeast stain, Δyml054c-pYES2-GOX3, showed the presence of a protein that used l-lactate as a substrate (Fig. 1D). A drop test of all lines confirmed that GOX3 can complement the Δyml054c growth phenotype on l-lactate as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1B), showing that GOX3 can indeed metabolize l-lactate to pyruvate in vivo.

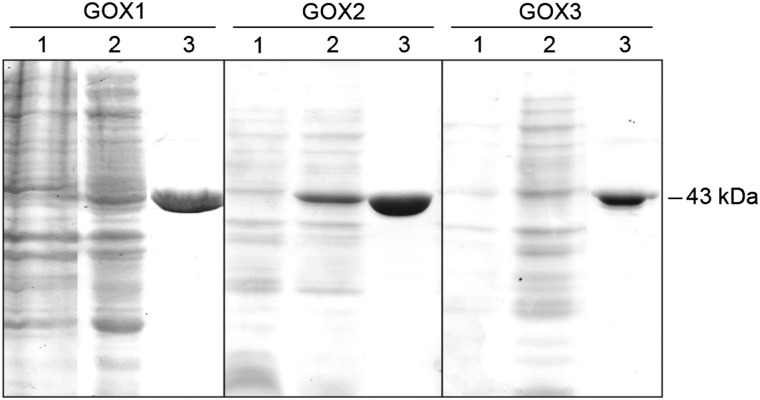

Biochemical Characterization of Recombinant GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3

Photorespiratory GOXs act as oxidases producing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in vivo (Tolbert, 1997; Fahnenstich et al., 2008; Sewelam et al., 2014). To analyze the biochemical properties of the Arabidopsis GOX paralogs, the GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 proteins were heterologously expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity (Fig. 2). The isolated recombinant proteins have molecular masses of approximately 43 kD (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-PAGE gels of different fractions during the isolation of recombinant Arabidopsis GOX1 to GOX3. Lane 1, 20 µg of E. coli crude protein extract before the induction of expression; lane 2, 20 µg of E. coli crude extract expressing GOX1 to GOX3 after isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction; lane 3, 3 µg of purified recombinant GOX1 to GOX3 protein.

All three purified enzymes had a faint yellow color, indicating the presence of a prosthetic group. For analysis of the prosthetic groups of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3, they were released from the recombinant proteins by boiling the purified enzymes and subsequently separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). The calculated RF values were similar to FMN but neither to FAD nor riboflavin, clearly indicating that all three GOX isoforms use FMN as a prosthetic group (Table I). The oxidation of glycolate to glyoxylate requires a redox partner as an electron acceptor. In order to biochemically characterize GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3, we first tested the enzymatic activity on glycolate with a number of different possible electron acceptors. None of the enzymes was capable of reducing the electron acceptors cytochrome c, NAD+, or NADP+. By contrast, when measuring the activity with molecular oxygen or the artificial electron acceptor 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCIP) as electron acceptor, high activities could be determined with all three isozymes (Supplemental Table S1). GOX1 showed the highest activity using DCIP as electron acceptor and displayed 74% activity using oxygen. Conversely, GOX2 showed the highest activity using oxygen as electron acceptor and displayed 75% of its maximal activity with DCIP. GOX3 had similar activities using either oxygen (100%) or DCIP (99%). These results suggest that all three GOX isozymes can act as oxidases and dehydrogenases, using synthetic electron acceptors, in vitro. The fact that GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 did not display activity with natural electron acceptors such as cytochrome c, NAD+, or NADP+ suggests that they do not act as dehydrogenases in vivo.

Table I. Characterization of the prosthetic group of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3.

The prosthetic groups of the enzymes were released by boiling and spotted together with FMN, FAD, and riboflavin onto a cellulose 300 TLC plate. The TLCs were run in the dark with the solvent mixtures 5% Na2HPO4 in aqueous solution (A) and 1-butanol:acetic acid:water (4:1:5; B). The sample positions were detected under UV light.

Thus, our data strongly support the universally accepted function of the photorespiratory isozymes as oxidases, reducing oxygen and producing H2O2, which is further dismutated in the peroxisomes by catalase (Foyer et al., 2009). We next determined the kinetic constants of one selected photorespiratory GOX, GOX1, and also of GOX3 for oxygen. The kinetic constants for oxygen were determined for three different l-glycolate concentrations (5, 7.5, and 10 mm) and two different enzyme amounts (1 and 5 mg) using a Clarke-type oxygen electrode. A sigmoidal kinetic was observed for both GOX1 and GOX3. The S0.5 value for oxygen, which represents the molecular oxygen concentration at which one-half of the enzyme is saturated when the reaction follows a sigmoidal kinetic, was approximately 190 and 200 µm for GOX1 and GOX3, respectively (Table II). Both GOX1 and GOX3 had a Hill coefficient greater than 1, indicating a positive cooperativity for the binding of oxygen. Moreover, the respective catalytic rates of GOX1 and GOX3 were of the same order or magnitude (Table II).

Table II. Substrate specificities of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3.

Enzyme activities were determined using heterologously expressed and purified enzymes and standard assay conditions using a range of substrates at a concentration of 5 mm (glycolate to l-lactate and leucic acid to isoleucic acid) and 0.5 mm (2-hydroxyhexanoic acid to 2-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid, all dissolved in ethanol), and product accumulation using phenylhydrazine (oxygen as electron acceptor) was monitored photometrically. Shown are mean values of the activities relative to the best substrate of at least two independent experiments. —, No activity was detected.

| Sample | Relative Oxidase Activity |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| GOX1 | GOX2 | GOX3 | |

| % | |||

| Glycolate | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| l-Lactate | 45 | 48 | 76 |

| 2-Hydroxyhexanoic acid | 0.2 | — | 9.4 |

| 2-Hydroxyoctanoic acid | 2.4 | — | 14.3 |

| 2-Hydroxydodecanoic acid | 1.8 | — | 8.8 |

| 2-Hydroxyhexadecanoic acid | — | — | 0.4 |

| Leucic acid | 1 | — | 6.1 |

| Valic acid | — | — | 0.1 |

| Isoleucic acid | 0.1 | — | — |

The optimum pH values for GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 were next determined using glycolate as substrate. Both oxidase and dehydrogenase activities were measured using either molecular oxygen or DCIP as electron acceptor. Irrespective of the electron acceptor type, all isoforms displayed bell-shaped pH-dependent activity curves with a pH optimum of 7.5 (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Substrate Screening Confirms l-Lactate and Glycolate as GOX3 Substrates in Vitro

We next determined the substrate spectrum of GOX3, as well as its close homologs GOX1 and GOX2, using a panel of 2-hydroxy acids. All three isozymes have narrow substrate specificities (Table III). They displayed highest activities using glycolate as substrate (100%), followed by l-lactate. The relative activities with l-lactate were 46%, 48%, and 76% in the case of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3, respectively. These results indicate that GOX3 can use l-lactate more effectively than the photorespiratory isozymes. Additionally, all isoforms could utilize other long- and medium-chain 2-hydroxy acids, although with much lower activities (Table III). None of the isozymes was able to use d-lactate as substrate or catalyze the reverse reaction using glyoxylate with either NADH or NADPH.

Table III. Kinetic constants of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3.

Kinetic constants were determined using the standard reaction mix either of the oxidase assay or the dehydrogenase assay, varying the substrate concentration from 0 to 37.9 mm; 1 to 5 µg of purified enzyme was used. Kinetic data were determined using the nonlinear regression fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation f(x) = ax/b + x (Sigma Plot software). Shown are mean values ± se of three independent experiments.

| Sample | Km | kcat | kcat/Km |

|---|---|---|---|

| µm | min−1 | min−1 mm−1 | |

| GOX1 | |||

| Glycolate | 278 ± 13 | 254 ± 2 | 911 |

| l-Lactate | 2,753 ± 165 | 114 ± 2 | 41 |

| GOX2 | |||

| Glycolate | 327 ± 21 | 224 ± 4 | 744 |

| l-Lactate | 4,905 ± 241 | 116 ± 2 | 24 |

| GOX3 | |||

| Glycolate | 144 ± 10 | 104 ± 1 | 725 |

| l-Lactate | 420 ± 4 | 80 ± 2 | 190 |

Determination of Kinetic Constants

A kinetic characterization of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 was performed using their preferred substrates. All GOX isozymes showed similar high catalytic efficiencies (turnover number [kcat]/Km) for the oxidation of glycolate (Table IV). Differences in the kinetic properties of the GOX isozymes were found when l-lactate was used as substrate. GOX1 and GOX2 have very low catalytic efficiencies using l-lactate as oxidase (22- and 31-fold lower catalytic efficiencies than with glycolate, respectively), which result from low affinities toward l-lactate (Table IV). When using l-lactate as substrate, GOX3 showed a catalytic efficiency in the same range as with glycolate (only 3.8-fold lower catalytic efficiencies than with glycolate; Table IV). This higher catalytic efficiency of GOX3 toward l-lactate results from a much higher affinity toward l-lactate in comparison with GOX1 and GOX2 (Table IV). These results show that GOX3 is able to use l-lactate with a similar efficiency as it uses glycolate, in contrast to the photorespiratory isoforms GOX1 and GOX2, which use glycolate with much higher efficiencies.

Table IV. Kinetic constants of GOX1 and GOX3 for molecular oxygen.

Kinetic constants were determined using the standard reaction mix for measurements using the oxygen electrode, varying the substrate concentration from 5 to 10 mm and monitoring the decreasing oxygen concentration; 4 to 10 µg of purified enzyme was used. S0.5 and Vmax values were determined using the nonlinear regression fit to the sigmoidal Hill equation f(x) = axb/cb + xb (Sigma Plot software). Shown are mean values ± se of three independent experiments.

| Sample | S0.5 | kcat | kcat/Km | Hill Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| µm | min−1 | min−1 mm−1 | ||

| GOX1 | ||||

| Glycolate | 187 ± 18 | 831 ± 67 | 4,446 | 1.72 ± 0.08 |

| GOX3 | ||||

| Glycolate | 202 ± 14 | 538 ± 35 | 2,656 | 1.94 ± 0.07 |

| l-Lactate | 153 ± 6 | 851 ± 29 | 5,554 | 1.93 ± 0.06 |

The kinetic parameters determined indicate both glycolate and l-lactate as putative substrates of GOX3 in vivo. To evaluate if the use of l-lactate as substrate influences the preference for an electron acceptor, the kinetic constants of GOX3 for molecular oxygen were also determined using l-lactate. As shown in Table II, the affinity of GOX3 for oxygen is the same using both l-lactate and glycolate as substrates. Again, the Hill coefficient was greater than 1, indicating a positive cooperativity toward molecular oxygen. These results indicate that, as in the case of the photorespiratory counterparts, GOX3 acts on glycolate and l-lactate as an oxidase in vivo.

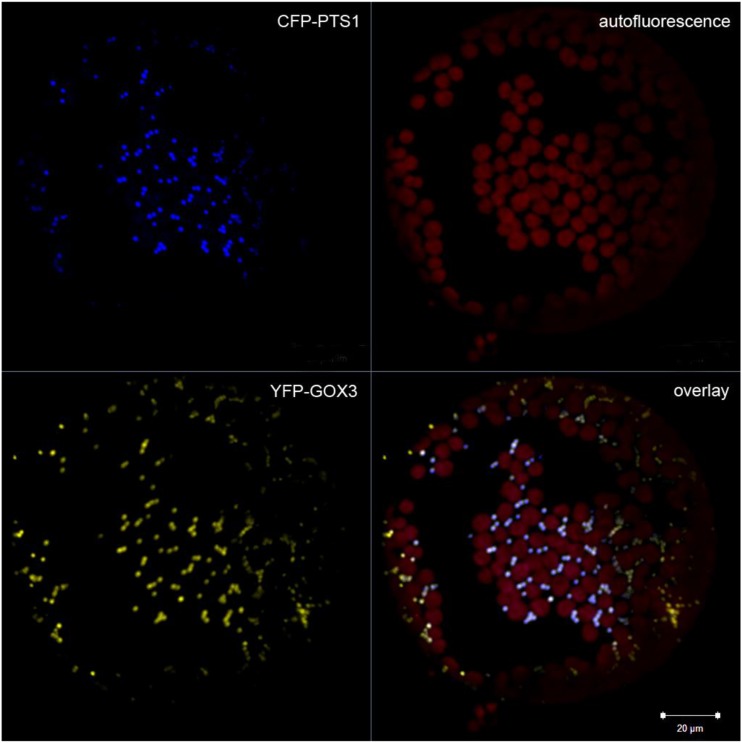

Subcellular Localization of GOX3

During photorespiration, the oxidation of glycolate by GOX1 and GOX2 produces H2O2 in peroxisomes, which is further dismutated to water and oxygen by catalase (Foyer et al., 2009). GOX3, like GOX1 and GOX2, is also predicted to localize to peroxisomes (Esser et al., 2014). To experimentally verify this prediction, the full coding sequence of GOX3 was fused in frame to an N-terminal yellow fluorescent protein (YFP). This construct was coexpressed with a cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fusion of PTS1, known to mediate localization to peroxisomes (Linka et al., 2008), in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Microscopic analysis of protoplasts generated from transformed N. benthamiana leaves showed CFP fluorescence of the peroxisomal control with the typical punctate pattern for peroxisomes (Fig. 3). The same pattern was observed for YFP-GOX3, and the overlay showed that both patterns of fluorescence merged, confirming the peroxisomal localization of GOX3 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Microscopic analysis of the subcellular localization of GOX3. YFP-GOX3 was expressed together with CFP-PTS1 in N. benthamiana leaves. Protoplasts were prepared, and their microscopic examination showed that fluorescence related to CFP-PTS1 was localized to dotted organelles. This pattern was identical to that of YFP-GOX3, with predominant merged dots in the overlay image. Bar = 20 µm.

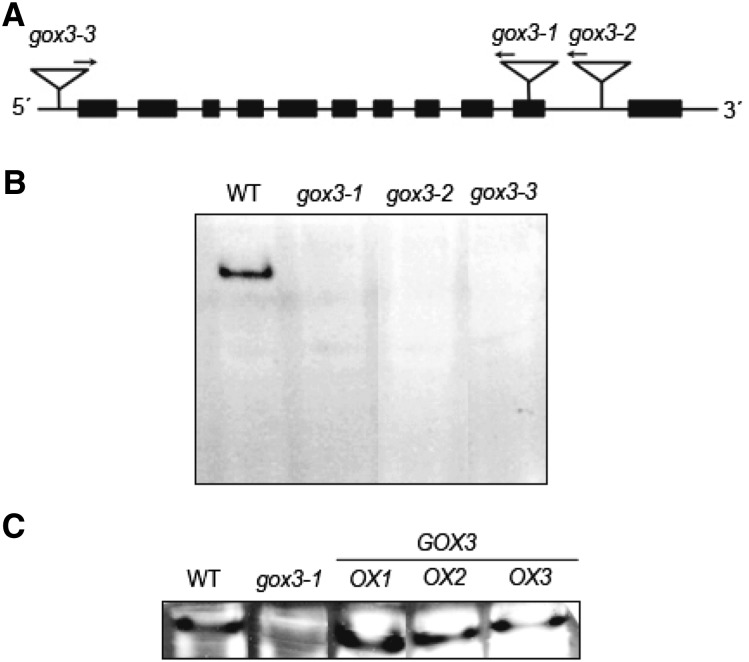

Isolation of Loss-of-Function and Overexpression Lines of GOX3

We have now established the substrate spectrum, electron acceptor, and subcellular localization of GOX3. To investigate the physiological function of GOX3 in planta, we isolated three independent homozygous transfer DNA (T-DNA) insertion lines for GOX3, gox3-1 (GK_523D09), gox3-2 (SALK_020909), and gox3-3 (SAIL_1156_F03), with insertions in exon 10, intron 10, and the 5′ untranslated region, respectively (Fig. 4A). All lines were confirmed as knockout mutants, since no transcript could be detected in either case (data not shown) and the lack of GOX3 enzymatic activity was confirmed in all mutant lines by an in-gel activity assay using protein extracts from root cultures (Fig. 4B); while the wild type showed a clear band with activity corresponding to GOX3 activity, this band could not be detected in extracts of the mutant lines. The absence of the GOX3 protein was additionally confirmed in extracts of root cultures and of mature leaves of the GOX3 loss-of-function plants by immunoblot analysis using specific antibodies (Fig. 5A).

Figure 4.

Analysis of Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion mutants in GOX3. A, Schematic representation of At4g18360 encoding GOX3. Exons are shown as blocks and introns as lines, and the sites of the T-DNA insertions in gox3-1 (GK_523D09), gox3-2 (SALK_020909), and gox3-3 (SAIL_1156_F03) are indicated. The arrows indicate the T-DNA left border. B, In-gel oxidase activity assay using l-lactate as substrate and root extracts of the wild type (WT) and the different gox3 loss-of-function mutants grown for 4 weeks in liquid medium. The same amount of total protein was loaded in each lane. C, In-gel oxidase activity assay using l-lactate as substrate and root extracts of the wild type, gox3-1, and the different GOX3-overexpressing lines grown for 4 weeks in liquid medium. The same amount of total protein was loaded in each lane.

Figure 5.

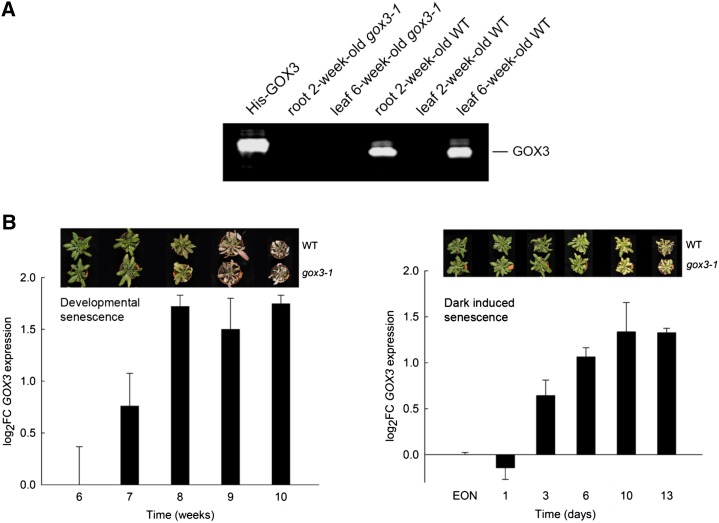

GOX3 in different organs and developmental stages of Arabidopsis. A, Immunodetection of GOX3 in root and leaf of different developmental stages of Arabidopsis wild-type plants (WT) using specific antibodies. The first lane shows the isolated recombinant protein GOX3 with the His tag (His-GOX3) as a positive control. The second and third lanes show a root extract and a leaf extract of a 6-week-old gox3-1 loss-of-function mutant as negative controls. The same amount of protein extract was loaded in each lane. B, Relative GOX3 transcript abundance in wild-type whole rosette leaves upon developmental senescence (left) and dark-induced senescence (right). Transcripts were monitored over the time course indicated in three independent growth experiments and normalized to the start point of the onset of natural senescence at 6 weeks. Data are means ± se. The courses of developmental and dark-induced senescence in the wild type and gox3-1 are shown in the insets.

We then generated independent homozygous lines overexpressing the full-length GOX3 open reading frame from the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter, to ensure a high expression level of GOX3, in the Arabidopsis Columbia-0 (Col-0) wild-type background (lines GOX3-OX1 and GOX3-OX2 were selected for further work). Moreover, we generated independent homozygous GOX3-overexpressing lines by expressing the full-length GOX3 open reading frame driven by its own promoter (line GOX3-OX3 was selected for further work). In all selected lines, we confirmed higher GOX3 transcript levels than in the wild type using leaf material of young plants (Supplemental Fig. S2). Protein extracts from root cultures of the overexpressing lines showed GOX3 activity by in-gel activity assay (Fig. 4C). As expected, due to the strength of the different promoters used for expression, higher transcript levels and higher GOX3 activities were obtained in lines GOX3-OX1 and GOX3-OX2 than in line GOX3-OX3.

Neither the GOX3 loss-of-function mutants nor the overexpression lines showed phenotypical differences when compared with the wild type in standard growth conditions in both long- and short-day photoperiods.

The Presence of GOX3 in Different Organs and Developmental Stages of Arabidopsis

To better understand the role of GOX3 in plant metabolism, it is important to know in which tissues and developmental stage it is present. To investigate this, we analyzed the presence of GOX3 protein by immunoblotting with specific antibodies. The specificity of these antibodies was verified using purified recombinant GOX3 as a positive control as well as leaf extracts of GOX3 loss-of-function plants as negative controls. An immunoreactive band of 45 kD was clearly present in the positive control, while it was absent in the negative control (Fig. 5A). Analysis of wild-type plants indicated that GOX3 is present in roots as well as in leaves of mature (6-week-old) plants. We found that GOX3 is absent from leaves of young (2-week-old) plants. These results are in line with previous expression analyses (Kamada et al., 2003; Arabidopsis eFP Browser).

The presence of GOX3 only in mature leaves of wild-type plants was further analyzed by quantitative PCR during the course of developmental and dark-induced senescence using whole wild-type rosettes. In agreement with GOX3 analyses, GOX3 transcripts could not be detected in young rosettes (Fig. 5B; Kamada et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 5B, GOX3 transcript could be detected at week 6, increasing afterward to reach a plateau at week 8. GOX3 transcript also accumulated continuously during dark-induced senescence, reaching a maximum 10 d after transfer to darkness (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, during both types of aging, GOX3 loss-of-function mutants (Fig. 5B) and overexpressor lines (data not shown) did not differ phenotypically from the wild type.

Collectively, these results indicate that GOX3 plays a more prominent role in heterotrophic tissue than in autotrophic tissues.

Isotope Tracer Experiments

In order to augment the data from the experiments described above, we next evaluated the redistribution of heavy isotope, following incubation in 10 mm l-[13C]lactate and [13C]glycolate, in leaves of the loss-of-function mutant gox3-1 (where GOX3 is not transcribed due to the T-DNA insertion; Fig. 4) and of the overexpressor line GOX3-OX1 (where GOX3 is transcribed at a high level; Supplemental Fig. S2). In order to carry out the experiment in the most physiological manner possible, we incubated intact leaves via the transpiration stream of the petiole using previously described approaches (Timm et al., 2008) and then followed the redistribution of label into other metabolic pools via an established gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based protocol (Roessner-Tunali et al., 2004; Heise et al., 2014).

The two lines displayed a difference in the total label redistribution, with the knockout line redistributing 88 nmol g−1 fresh weight 2 h−1 and the overexpressor redistributing 241 nmol g−1 fresh weight 2 h−1 following incubation in l-[13C]lactate (a more than 2.7-fold higher total redistribution). By contrast, following incubation in [13C]glycolate, the knockout line redistributed a total of 103 nmol g−1 fresh weight 2 h−1 and the overexpressor redistributed 154 nmol g−1 fresh weight 2 h−1 (an approximately 1.5-fold higher total redistribution). Thus, these results support the conclusion from the in vitro studies described above that GOX3 uses lactate as the preferred substrate.

Following incubation in either substrate, considerable differences in metabolite pool sizes between the knockout and overexpressing lines could be observed, with 27 of the 38 measured metabolites being differentially abundant following l-[13C]lactate feeding and only 13 being differentially abundant following [13C]glycolate feeding (Table V). Particularly notable are the greater than 5-fold increases in Ala, β-Ala, Arg, Asn, Asp, Gln, malate, and putrescine following incubation in l-lactate. By contrast, following incubation in glycolate, the Pro pool was dramatically increased, followed by Ala, Arg, and Gln, which were more than 3-fold increased. In summary, the l-lactate feeding stimulated more changes in metabolite pools than the glycolate feeding, and additionally, the GOX3-overexpressing plants also displayed changes of greater magnitude when supplied with this substrate (Table V).

Table V. Leaf metabolite profiling of gox3-1 and GOX3-OX1 fed with [13C]l-lactate and [13C]glycolate.

Values are presented as means ± se from four individual samples. GOX3-OX1 values in boldface are significantly different from gox3-1 values, and asterisks indicate significant differences between the two feeding experiments according to a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s test; P < 0.05).

| Metabolite | [13C]l-Lactate |

[13C]Glycolate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gox3-1 | GOX3-OX1 | gox3-1 | GOX3-OX1 | ||||

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | |||||||

| Ala | 197.56 ± 55.52 | 484.37 ± 54.31 | 133.98 ± 5.43 | 325.03 ± 25.40* | |||

| Arg | 150.98 ± 41.24 | 973.13 ± 194.90 | 164.26 ± 47.81 | 584.40 ± 104.12* | |||

| Asn | 9.03 ± 1.73 | 106.96 ± 20.57 | 20.02 ± 3.36 | 66.35 ± 9.48* | |||

| Asp | 20.89 ± 6.30 | 114.99 ± 17.23 | 21.16 ± 3.94 | 51.28 ± 5.84* | |||

| Citrate | 1.99 ± 0.38 | 2.83 ± 0.86 | 1.27 ± 0.46 | 1.57 ± 0.22 | |||

| Dehydroascorbate | 107.09 ± 19.56 | 268.32 ± 58.90 | 87.01 ± 43.27 | 124.47 ± 11.05* | |||

| Erythritol | 0.26 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | |||

| Fru | 67.14 ± 5.51 | 96.28 ± 14.23 | 185.54 ± 65.59 | 145.43 ± 43.05 | |||

| Fumarate | 319.78 ± 46.36 | 689.31 ± 128.78 | 317.89 ± 68.39 | 702.86 ± 233.32 | |||

| GABA | 12.94 ± 2.46 | 21.77 ± 5.07 | 8.48 ± 2.15 | 13.68 ± 3.47 | |||

| Glc | 115.77 ± 16.28 | 280.83 ± 27.89 | 294.58 ± 84.07 | 360.00 ± 81.24 | |||

| Glu | 160.07 ± 13.68 | 617.20 ± 104.64 | 172.41 ± 31.58 | 369.52 ± 71.51* | |||

| Gln | 129.55 ± 19.38 | 821.61 ± 56.47 | 186.16 ± 20.05 | 622.72 ± 49.86* | |||

| Glycerate | 2.78 ± 0.50 | 5.35 ± 1.35 | 4.61 ± 0.66 | 6.12 ± 0.86 | |||

| Gly | 9.16 ± 2.94 | 72.09 ± 18.20 | 17.49 ± 2.34 | 49.09 ± 10.01 | |||

| Glycolate | 3.16 ± 0.97 | 5.71 ± 0.67 | 12.58 ± 1.16 | 12.01 ± 0.41* | |||

| Inositol | 106.13 ± 17.52 | 225.21 ± 22.27 | 101.08 ± 16.34 | 179.22 ± 14.54 | |||

| Ile | 2.47 ± 0.35 | 9.44 ± 1.49 | 3.05 ± 0.19 | 5.65 ± 0.26* | |||

| Lys | 1.93 ± 0.39 | 9.87 ± 1.90 | 1.88 ± 0.15 | 5.74 ± 0.30* | |||

| Malate | 48.08 ± 9.84 | 262.84 ± 48.51 | 55.74 ± 11.81 | 146.27 ± 4.27* | |||

| Maltose | 10.65 ± 3.60 | 24.25 ± 9.81 | 5.91 ± 1.38 | 7.13 ± 1.57* | |||

| Met | 1.08 ± 0.23 | 3.35 ± 0.28 | 0.82 ± 0.18 | 2.98 ± 0.44 | |||

| Phe | 4.23 ± 1.08 | 10.90 ± 1.00 | 5.38 ± 1.54 | 8.98 ± 1.01 | |||

| Pro | 129.51 ± 45.20 | 923.99 ± 109.55 | 55.36 ± 17.83 | 617.31 ± 197.18 | |||

| Putrescine | 4.11 ± 1.13 | 18.24 ± 3.59 | 7.04 ± 1.69 | 11.44 ± 1.10* | |||

| Pyruvate | 2.56 ± 0.85 | 7.94 ± 1.82 | 3.93 ± 1.10 | 4.57 ± 0.40 | |||

| Raffinose | 58.00 ± 20.47 | 76.91 ± 6.17 | 27.12 ± 5.21 | 44.53 ± 12.40 | |||

| Ser | 62.92 ± 18.88 | 212.35 ± 6.28 | 95.66 ± 11.34 | 174.59 ± 14.92 | |||

| Sorbose | 30.84 ± 3.72 | 54.26 ± 8.28 | 92.93 ± 34.16 | 74.67 ± 20.88 | |||

| Spermidine | 5.22 ± 0.77 | 7.26 ± 2.01 | 3.14 ± 0.72 | 6.43 ± 0.34 | |||

| Succinate | 18.63 ± 2.35 | 49.42 ± 8.19 | 11.98 ± 1.79 | 29.29 ± 1.14* | |||

| Suc | 33.01 ± 9.36 | 91.00 ± 14.67 | 27.14 ± 0.52 | 54.15 ± 4.18* | |||

| Threonate | 32.52 ± 5.92 | 94.32 ± 23.95 | 62.08 ± 11.95 | 75.12 ± 13.17 | |||

| Thr | 25.68 ± 7.17 | 96.61 ± 8.92 | 25.28 ± 3.66 | 63.12 ± 4.96* | |||

| Trp | 17.97 ± 2.58 | 36.17 ± 6.97 | 20.03 ± 3.82 | 27.79 ± 4.29 | |||

| Tyr | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 2.02 ± 0.34 | 0.94 ± 0.36 | 1.40 ± 0.24 | |||

| Val | 6.36 ± 1.10 | 22.33 ± 3.45 | 5.78 ± 0.40 | 13.71 ± 2.06* | |||

When only the levels of label redistribution are considered, far fewer differences between the knockout and overexpressing lines following incubation in either substrate were observed; only 15 of the 38 metabolites displayed significant differences in label accumulation following incubation in l-[13C]lactate, while only 11 metabolites showed significant differences in label accumulation following incubation in [13C]glycolate (Table VI). Following l-[13C]lactate feeding, the most prominent changes were the increases, in the GOX3 overexpressor, of Asn, Glu, Gln, inositol, Ile, Lys, malate, maltose, Phe, Pro, raffinose, Suc, threonate, Thr, and Val, which were more than 2-fold as high in the overexpressors than in the knockout line. Following incubation in [13C]glycolate, the accumulation of label in Asp, Lys, malate, Met, Pro, and Thr was more than 2-fold as high in the overexpressors than in the knockout line; however, the label accumulation in glycolate was significantly lower in the overexpressor than in the knockout line.

Table VI. Redistribution of label (total enrichment) following feeding of leaves with [13C]l-lactate and [13C]glycolate in gox3-1 and GOX3-OX1.

Values are presented as means ± se of four individual samples. GOX3-OX1 values in boldface are significantly different from gox3-1 values, and asterisks indicate significant differences between the two feeding experiments according to a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s test; P < 0.05).

| Metabolite | [13C]l-Lactate |

[13C]Glycolate |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gox3-1 | GOX3-OX1 | gox3-1 | GOX3-OX1 | ||||

| nmol g−1 fresh wt | |||||||

| Ala | 40.07 ± 9.31 | 53.89 ± 15.71 | 4.53 ± 0.60* | 6.73 ± 0.56* | |||

| Arg | 1.70 ± 1.31 | 6.03 ± 3.76 | 0.53 ± 0.53 | 6.76 ± 3.80 | |||

| Asn | 0.44 ± 0.04 | 4.36 ± 1.65 | 0.87 ± 0.05 | 2.40 ± 0.27 | |||

| Asp | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | |||

| Citrate | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | |||

| Erythritol | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | |||

| Fru | 0.42 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.14 | 0.94 ± 0.23 | 0.98 ± 0.32 | |||

| Fumarate | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.09 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.13 | |||

| GABA | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.12 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | |||

| Glc | 2.59 ± 0.35 | 6.28 ± 0.56 | 7.29 ± 2.23* | 8.26 ± 1.84 | |||

| Glu | 3.92 ± 0.40 | 8.44 ± 2.58 | 1.23 ± 0.17 | 2.24 ± 0.44* | |||

| Gln | 22.52 ± 2.72 | 61.07 ± 7.13 | 50.85 ± 13.87 | 66.65 ± 14.02 | |||

| Glycerate | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.16* | 0.83 ± 0.07* | |||

| Gly | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.07 | 1.50 ± 0.40* | 1.89 ± 0.27* | |||

| Glycolate | 0.58 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.13 | 10.19 ± 1.06* | 8.09 ± 0.28* | |||

| Inositol | 0.79 ± 0.14 | 2.23 ± 0.24 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 1.65 ± 0.06* | |||

| Ile | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.00* | 0.02 ± 0.00* | |||

| Lys | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.03* | |||

| Malate | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 1.39 ± 0.57 | 0.53 ± 0.15 | 1.12 ± 0.16 | |||

| Maltose | 1.12 ± 0.35 | 2.76 ± 1.03 | 0.78 ± 0.19 | 0.78 ± 0.17* | |||

| Met | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.07 ± 0.02* | |||

| Phe | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.03 | 0.09 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.04* | |||

| Pro | 2.77 ± 0.85 | 18.20 ± 2.43 | 1.30 ± 0.24 | 10.27 ± 3.70* | |||

| Raffinose | 0.42 ± 0.16 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.15 | |||

| Ser | 0.61 ± 0.22 | 0.76 ± 0.19 | 13.56 ± 2.14* | 22.89 ± 3.87* | |||

| Succinate | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.80 ± 0.49 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | |||

| Suc | 1.31 ± 0.30 | 2.89 ± 0.44 | 2.30 ± 0.08 | 4.27 ± 0.30* | |||

| Threonate | 1.75 ± 0.27 | 5.25 ± 1.19 | 3.29 ± 0.64 | 4.31 ± 0.71 | |||

| Thr | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 1.26 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.11* | |||

| Tyr | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |||

| Val | 1.08 ± 0.15 | 3.21 ± 0.47 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 1.57 ± 0.23* | |||

Conditional Phenotype of gox3 Plants and Its Complementation

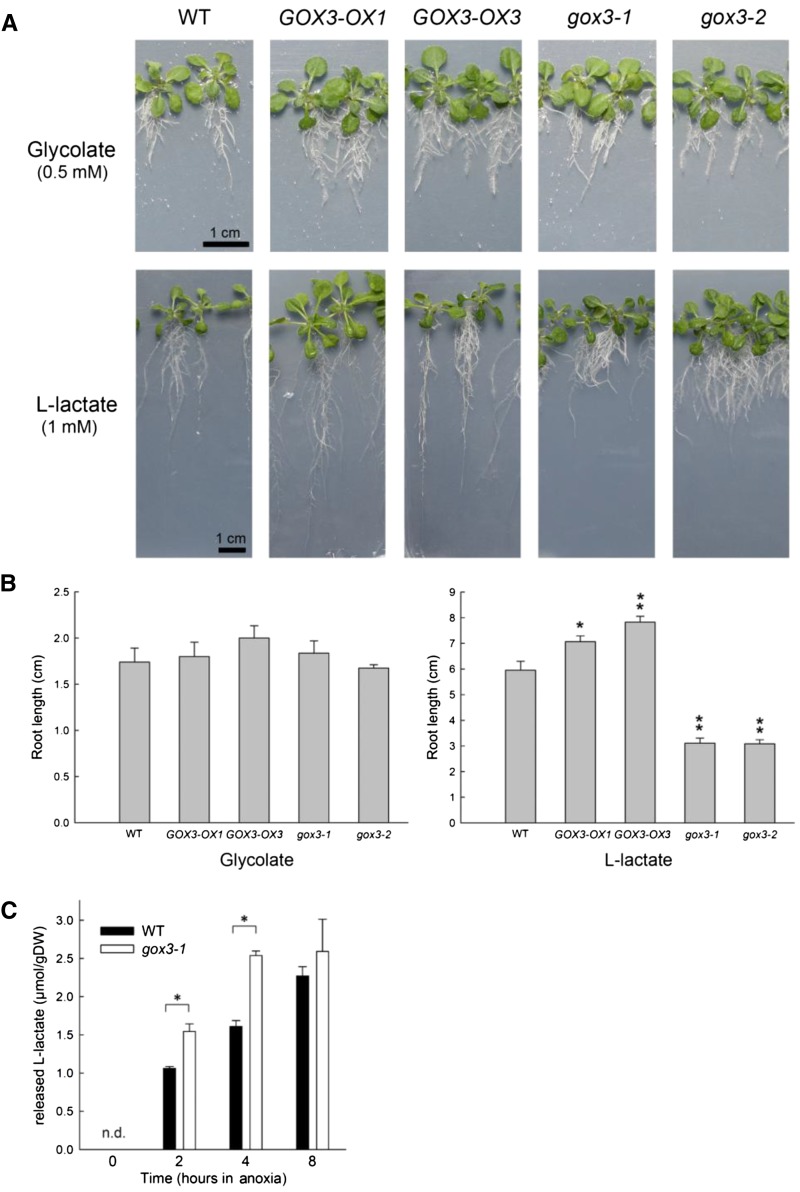

The in vitro activity assays with purified recombinant GOX3 revealed high enzymatic activity with both glycolate and l-lactate (Table III). Furthermore, GOX3 is active in roots (Fig. 4). To further analyze which of these 2-hydroxy acids is the physiological substrate, we chose to perform a substrate-feeding experiment with wild-type plants, GOX3 overexpressor plants, and gox3 knockout plants. The two overexpressing lines, GOX3-OX1 and GOX3-OX3, and the gox3-1 and gox3-2 T-DNA insertion lines were grown together with wild-type plants on sterile medium supplemented with either glycolate or l-lactate. The concentrations of glycolate and l-lactate in the medium were chosen such that root growth in wild-type plants was reduced. These conditions allow increases and decreases in root growth to be visualized. On control plates (no added glycolate or l-lactate; data not shown) and on plates supplemented with glycolate, the root growth rate was the same in all tested genotypes (Fig. 6, A and B). In all cases, root growth on glycolate-supplemented medium was highly reduced compared with the control. In contrast, root growth on medium supplemented with l-lactate was highly impaired solely in the two GOX3 loss-of-function mutants (Fig. 6, A and B). This difference in root growth was consistently seen in a dose-dependent manner over the concentration range of 0.5 to 10 mm l-lactate (data not shown). Furthermore, the GOX3-overexpressing lines had improved root development compared with the wild type on medium supplemented with l-lactate (Fig. 6, A and B). These results are clear evidence that l-lactate is metabolized in vivo by GOX3.

Figure 6.

Substrate toxicity test in Arabidopsis seedlings. A, Representative plantlets of different genotypes grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) plates containing 0.5 mm glycolate or 1 mm l-lactate. Bars = 1 cm. B, Root length of plantlets grown as in A. GOX3-OX1, GOX3 overexpressor with CaMV 35S promoter; GOX3-OX3, GOX3 overexpressor with GOX3 promoter; gox3-1 and gox3-2, loss-of-function mutants of GOX3. The values are means ± se from at least 15 plants per line. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the wild type (WT) according to the two-tailed Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; and **, P < 0.005). C, Absolute amount of l-lactate excreted to the surrounding medium normalized to grams dry weight (DW) over a time course of 8 h after the induction of hypoxia. The values are means ± sd. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences from the wild type according to the two-tailed Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05). n.d., Not detected.

Metabolite Profiles of Roots under Normoxia and Hypoxia

We have demonstrated that GOX3 is present in roots of Arabidopsis and that GOX3 loss-of-function mutants and overexpressor lines show a root conditional phenotype when fed with l-lactate. Isotope tracer experiments indicated that l-lactate is the preferred substrate of GOX3, and the kinetic analysis revealed that this isozyme has a high catalytic efficiency with l-lactate. Moreover, GOX3 could restore the growth on l-lactate of a yeast strain impaired in l-lactate oxidation. All these results prompted us to analyze if GOX3 is involved in l-lactate oxidation in roots. We considered that the analysis of the metabolic status of roots of the Arabidopsis wild type and GOX3 loss-of-function mutants under normoxia and during a time course of a hypoxic treatment would provide clues on the possible involvement of GOX3 in sustaining l-lactate homeostasis in root cells.

Arabidopsis wild-type plants and gox3-1 mutants were grown in a hydroponic system with air bubbling and stirring to ensure oxygenation of the medium, and hypoxia was induced by eliminating air bubbling and stirring. Upon induction of the treatment, the expression of the hypoxia marker genes ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE (ADH) and LDH1 (encoding l-LDH) increased rapidly in roots and remained at high levels during the course of the treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3A). A decrease of expression was observed after reoxygenation of the medium (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Furthermore, we analyzed the expression of NIP2.1 and LDH1 after short-term hypoxia treatment to monitor the onset of hypoxia. The results obtained indicated a strong induction of the expression of both marker genes already at 2 h (Supplemental Fig. S3B). In the case of the wild type, maximal expression levels were observed at 4 h after the induction of hypoxia for NIP2.1 and LDH1 expression. The gox3-1 loss-of-function mutant showed maximal expression levels already at 2 h after the induction of hypoxia. Confirming that this method is able to rapidly induce hypoxia and reoxygenation of the root system, we next analyzed the expression of GOX3 using the same system. In the wild type, hypoxia triggered a transient and low increase in GOX3 expression at the beginning of the treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3C). Expression of GOX3 increased by approximately 3-fold after 8 h of hypoxia and subsequently decreased to normoxia levels. Nevertheless, GOX3 activity showed no differences during the course of the treatment (Supplemental Fig. S3C).

We performed a metabolic profile analysis on root samples taken under normoxia (time 0 = 1 pm; 8 h in light, middle of the day), after 8 h (time 8 = 9 pm; 16 h in light, end of day) and 24 h (time 24 = 1 pm) of hypoxia treatment, and after 8 h of hypoxia followed by 40 h of reoxygenation (1 pm).

Under our experimental approach, lactate levels showed no significant alterations during the course of the hypoxic treatment in the wild type and gox3-1 (Table VII); however, at 8 h of hypoxia, the level was lower in gox3-1 than in the wild type (Table VII).

Table VII. Relative metabolite levels (to the internal standard ribitol) measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry of roots under normoxia and after 8 and 24 h of hypoxia (8 h, −oxygen and 24 h, −oxygen).

Values are presented as means ± se from at least four replicates. Values in boldface indicate significant differences from 0 h for each genotype, and asterisks indicate significant differences from the wild type at the corresponding time point, according to a two-way ANOVA (Tukey’s test; P < 0.05).

| Metabolite | 0 h |

8 h, −Oxygen |

24 h, −Oxygen |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | gox3-1 | Wild Type | gox3-1 | Wild Type | gox3-1 | |

| Sugars | ||||||

| Fru | 87.1 ± 15.5 | 204.7 ± 22.4* | 190.5 ± 27.9 | 227.7 ± 42.8 | 251.2 ± 37.4 | 299.2 ± 72.8 |

| Gluconate | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.2* | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| Glc | 485.2 ± 104.4 | 1120.7 ± 134.0* | 800.0 ± 87.6 | 998.7 ± 203.7 | 890.1 ± 129.0 | 1,280.4 ± 237.3 |

| Maltose | 207.3 ± 41.8 | 303.7 ± 17.9* | 301.2 ± 7.1 | 372.0 ± 26.4 | 396.7 ± 11.6 | 299.5 ± 14.4* |

| Mannitol | 9.6 ± 2.9 | 8.6 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 0.3 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 17.0 ± 3.0 | 12.6 ± 2.0 |

| Man | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 7.6 ± 1.7* | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| Myoinositol | 562.7 ± 85.1 | 827.5 ± 45.8* | 713.4 ± 33.9 | 857.2 ± 69.8 | 966.9 ± 31.3 | 829.2 ± 18.7 |

| Raffinose | 7.2 ± 2.6 | 6.4 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.23 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 8.1 ± 1.8 | 10.7 ± 3.9 |

| Sorbitol | 30.2 ± 5.9 | 45.2 ± 13.3 | 20.9 ± 5.3 | 13.9 ± 1.4 | 64.7 ± 5.9 | 48.2 ± 2.2 |

| Suc | 11,512.1 ± 1,331.3 | 12,855.0 ± 171.2 | 13,864.7 ± 1,221.0 | 15,837.4 ± 901.4 | 16,608.7 ± 1,197.9 | 14,536.9 ± 1,623.8 |

| Xyl | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 11.2 ± 1.5* | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 1.3* | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 11.1 ± 1.1* |

| Amino acids | ||||||

| Ala | 273.8 ± 35.6 | 398.1 ± 9.0* | 545.3 ± 9.6 | 678.0 ± 35.3 | 697.4 ± 21.8 | 797.0 ± 204.3 |

| Asp | 41.4 ± 7.4 | 26.9 ± 2.9 | 46.4 ± 2.73 | 54.0 ± 10.74 | 88.3 ± 9.05 | 57.6 ± 15.8 |

| β-Ala | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3* | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.33 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| GABA | 26.8 ± 7.2 | 65.6 ± 6.1* | 71.9 ± 3.2 | 69.7 ± 7.0 | 62.8 ± 3.8 | 56.2 ± 6.6 |

| Glu | 206.2 ± 49.5 | 114.0 ± 25.3 | 485.3 ± 39.7 | 534.6 ± 117.9 | 573.1 ± 94.9 | 368.0 ± 119.6 |

| Ile | 29.8 ± 4.9 | 32.5 ± 0.7 | 51.5 ± 4.0 | 68.2 ± 4.85* | 40.0 ± 2.6 | 34.3 ± 3.8 |

| Leu | 30.8 ± 4.5 | 31.3 ± 0.7 | 45.8 ± 3.5 | 59.78 ± 5.0* | 29.9 ± 2.5 | 26.9 ± 3.4 |

| Met | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 26.4 ± 2.5 | 20.7 ± 5.0 | 24.5 ± 1.7 | 15.0 ± 6.8 |

| Phe | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 39.9 ± 2.8 | 9.8 ± 2.1* | 12.9 ± 1.9 | 4.2 ± 1.4* |

| Pro | 6.4 ± 1.0 | 8.2 ± 0.5 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.9* | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 8.8 ± 1.9 |

| Shikimate | 46.5 ± 7.8 | 70.8 ± 3.2* | 46.1 ± 1.3 | 51.5 ± 3.7 | 74.7 ± 3.0 | 83.0 ± 8.6 |

| Thr | 94.3 ± 19.1 | 99.1 ± 10.8 | 91.7 ± 2.5 | 130.2 ± 10.8* | 137.4 ± 14.6 | 116.3 ± 11.0 |

| Trp | 38.1 ± 7.3 | 24.1 ± 1.9* | 34.4 ± 2.4 | 15.2 ± 0.7* | 20.5 ± 1.5 | 10.6 ± 0.8* |

| Val | 90.0 ± 14.7 | 103 ± 2.5 | 117.9 ± 6.8 | 159.2 ± 8.4* | 117.8 ± 6.5 | 106.6 ± 8.4 |

| Photorespiration | ||||||

| Glycerate | 8.0 ± 1.0 | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 7.3 ± 0.3 | 8.4 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 11.2 ± 0.7 |

| Gly | 36.3 ± 6.8 | 56.5 ± 5.4* | 72.8 ± 3.0 | 54.2 ± 5.2* | 76.8 ± 11.3 | 66.7 ± 4.1 |

| Glycolate | 220.1 ± 9.9 | 247.7 ± 4.3 | 257.7 ± 18.5 | 240.9 ± 20.5 | 261.6 ± 33.6 | 259.5 ± 26.9 |

| Ser | 74.9 ± 15.6 | 63.7 ± 6.2 | 100.9 ± 3.6 | 135.6 ± 10.8 | 105.2 ± 16.0 | 90.8 ± 19.5 |

| Tricarboxylic acid | ||||||

| (Iso)citrate | 435.7 ± 61.3 | 663.6 ± 25.8* | 495.0 ± 17.2 | 515.7 ± 20.5 | 633.4 ± 14.7 | 660.5 ± 44.97 |

| α-Ketoglutarate | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 7.1 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 7.3 ± 1.9 |

| 2-Hydroxyglutarate | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 6.37 ± 1.1 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 0.1* |

| Fumarate | 21.7 ± 2.5 | 38.6 ± 0.6* | 24.6 ± 0.4 | 26.2 ± 0.9 | 24.5 ± 1.0 | 32.2 ± 2.6* |

| Malate | 259.4 ± 34.1 | 354.7 ± 11.7* | 282.9 ± 5.6 | 364.4 ± 20.8* | 266.0 ± 2.3 | 339.5 ± 37.6* |

| Succinate | 39.0 ± 4.3 | 45.8 ± 1.2 | 53.1 ± 1.4 | 49.2 ± 2.9 | 51.2 ± 3.8 | 49.4 ± 3.4 |

| Others | ||||||

| Glycerol | 281.0 ± 32.2 | 320.3 ± 33.4 | 309.8 ± 10.0 | 331.5 ± 18.1 | 339.6 ± 13.8 | 307.8 ± 15.7 |

| Hydroxy butyrate | 13.16 ± 1.36 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 10.7 ± 3.7 | 13.6 ± 2.6 | 6.3 ± 1.8* |

| Lactate | 917.1 ± 76.1 | 691.0 ± 175.3 | 993.9 ± 171.3 | 610.1 ± 105.8* | 687.8 ± 133.7 | 537.5 ± 111.7 |

| Malate | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.37* | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 0.1* |

| Malonate | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.0 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| Oxalate | 60.68 ± 9.0 | 70.7 ± 5.7 | 82.8 ± 8.7 | 78.0 ± 8.38 | 173.4 ± 16.5 | 145.3 ± 6.3* |

| Quinic acid | 3.98 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.3 |

Sugars and Their Derivatives

In the wild type, the amount of Fru, maltose, and Suc increased during the course of hypoxia (Table VII). The relative levels of all these sugars decreased after reoxygenation (Supplemental Table S2). Other sugars, such as raffinose and Xyl, did not show modification of the relative levels, and Glc showed a clear tendency to increased levels. In gox3-1, the relative amounts of the above-mentioned sugars showed no significant changes during the course of the treatment except for Man, which accumulated at 8 h in hypoxia (Table VII). Under normoxia, the relative levels of Fru, Glc, maltose, and Xyl were significantly enhanced with respect to the wild type (Table VII).

Myoinositol and sorbitol accumulated in the wild type during hypoxia, while in gox3-1, the level of myoinositol in normoxia was similar to those of the wild type under hypoxia and did not change during the treatment (Table VII). Mannitol showed similar patterns in both lines (Table VII). Gluconate showed higher relative levels in gox3-1 than in the wild type under normoxia and the same tendency during hypoxia (Table VII).

Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Intermediates

During the hypoxic treatment in the wild type, the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates citrate and succinate increased, while 2-ketoglutarate, fumarate, and malate levels did not change (Table VII). Interestingly, the amount of 2-hydroxyglutarate, a tricarboxylic acid cycle-related metabolite (Araujo et al., 2010; Engqvist et al., 2011, 2014), increased significantly during hypoxia. In gox3-1, the level of 2-hydroxyglutarate already accumulated at 8 h of hypoxia. Under normoxia, the relative levels of citrate, fumarate, and malate were significantly enhanced in gox3-1 with respect to the wild type (Table VII). Moreover, fumarate significantly accumulated after 24 h of hypoxia and malate already after 8 h of hypoxia in gox3-1 with respect to the wild type (Table VII).

Photorespiration-Related Intermediates

The photorespiration-related intermediates glycerate and Gly accumulated during hypoxia in the wild type, while glycolate and Ser were not modified. In gox3-1, glycerate also accumulated during hypoxia, while Gly and glycolate levels were not modified. While the glycerate and glycolate levels were similar to those in the wild type, the Gly level was higher in the wild type than in gox3-1 at 8 h of hypoxia, and Ser accumulated in gox3-1 at 8 h of hypoxia (Table VII).

Amino Acids

During the hypoxic treatment, different patterns of changes in the relative levels of many amino acids were observed in the wild type. Increments after 8 h of hypoxia were observed in the levels of γ-aminobutyrate (GABA), Ile, Leu, Met, and Phe (Table VII). After 24 h under hypoxia, GABA and Met stayed at the same levels as at 8 h, while Ile, Leu, and Phe levels decreased (Table VII). Increases in the levels of Ala, Asp, Glu, and shikimate (an intermediate of aromatic amino acid biosynthesis) were observed after 24 h of hypoxia (Table VII). The levels of Pro, Trp, and Val did not change during the treatment (Table VII).

In gox3-1 many differences in the accumulation pattern of the amino acids were observed. Under normoxia, Ala, β-Ala, GABA, and shikimate accumulated to higher levels than in the wild type (Table VII). After the induction of hypoxia, the levels of Ala further increased in gox3-1, while those of β-Ala, GABA, and shikimate remained at similar levels as in normoxia (Table VII). During the hypoxic treatment, the aromatic amino acids Phe and Trp showed similar patterns of changes as the wild type, but these were of considerably lower magnitude (Table VII).

Excretion of l-Lactate into the Medium after the Onset of Hypoxia

The metabolite analysis indicated that lactate levels do not significantly change during the hypoxic treatment in both the wild type and gox3-1 loss-of-function plants and that, at 8 h of hypoxia, lactate was even lower in gox3-1 than in the wild type (Table VII). Furthermore, the expression of NIP2.1 increases rapidly upon the induction of hypoxia in the wild type and gox3-1 (Supplemental Fig. S3C). These results suggest that, upon the induction of oxygen deprivation, excess l-lactate is not accumulated intracellularly, but it might be excreted to the medium via NIP2.1. To analyze this hypothesis, we measured the concentration of l-lactate in the culture medium of the wild type and gox3-1 at different time points after 2, 4, and 8 h of oxygen deprivation (Fig. 6C). Already after 2 h of oxygen deprivation, significant amounts of l-lactate were excreted to the surrounding medium in wild-type and gox3-1 loss-of-function plants, confirming an active fermentative metabolism. The measurable l-lactate excretion increased constantly during the time course of hypoxia up to 8 h in both wild-type and mutant plants (Fig. 6C). However, the effect of l-lactate excretion was even more pronounced in gox3-1, which showed much higher lactate secretion than the wild type after 2 and 4 h of oxygen deprivation (Fig. 6C). Higher l-lactate levels measured in the surrounding medium of gox3-1 support the idea of the involvement of GOX3 in controlling l-lactate homeostasis in roots.

DISCUSSION

In roots of Arabidopsis, l-lactate is generated by the reduction of pyruvate via l-LDH at a low constant rate and at higher rates in response to oxygen deficiency (Sweetlove et al., 2000; Mustroph et al., 2014). Here, we endeavored to identify the enzyme that catalyzes the reverse reaction to metabolize l-lactate to pyruvate in Arabidopsis. Our data overwhelmingly indicate that GOX3 catalyzes this reaction in vivo. Intriguingly, the enzyme would not be involved in sustaining a low cellular l-lactate pool size during hypoxia but may instead contribute to sustain low levels of l-lactate after its formation in normal conditions.

GOX3 Restores Growth of the Yeast cyb2 Loss-of-Function Mutant on l-Lactate

As demonstrated previously, an S. cerevisiae strain deficient in CYB2 cannot grow on l-lactate as the sole carbon source (Guiard, 1985). GOX3 was identified as a putative l-lactate-metabolizing enzyme in Arabidopsis based on its homology to CYB2. Our data show that GOX3 can rescue the cyb2 lethal phenotype (Fig. 1B). On l-lactate as the sole carbon source, the complemented yeast strains grow like the wild-type strain, although GOX3 was not localized to the mitochondria but rather in the cytosol. We believe that, in our assay, the pyruvate produced by GOX3 must be transported to the mitochondria for further metabolism. Interestingly, the catalytic domains of GOX3 and CYB2 (Hartl et al., 1987; Ramil et al., 2000) are homologous (40% identity and 57% similarity) and, in accordance with the activity of GOX3 as an oxidase in root peroxisomes (see below), it lacks the cytochrome c-binding domain (Fig. 1A).

GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 Have Similar, Yet Distinct, Catalytic Properties

To clarify the enzymatic differences between GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3, we recombinantly expressed and purified them. All three enzymes bound FMN as a prosthetic group (Table I). This prosthetic group likely serves as an intermediate acceptor of substrate-derived electrons before they are passed on to the electron acceptor. Furthermore, all three enzymes had a broad substrate spectrum, with activity toward a range of l-2-hydroxy acids. The highest activity was seen with small substrates (Table III). All three enzymes had catalytic activity using oxygen as an electron acceptor, generating H2O2 in the process, as well as with the synthetic electron acceptor DCIP (Supplemental Table S1). The kinetics properties of the three enzymes were determined with glycolate and l-lactate (Table IV). These measurements indicated that GOX1 and GOX2 are typical photorespiratory enzymes that show their highest catalytic efficiency with glycolate as substrate and can only use l-lactate with low efficiency. Thus, contrary to the idea that the existence of two photorespiratory GOX proteins in Arabidopsis (GOX1 and GOX2) may represent the existence of isoforms with different catalytic properties, we found that both isoforms share similar enzymatic characteristics. Also, GOX3 had high catalytic efficiencies with glycolate. However, in contrast to GOX1 and GOX2, GOX3 also had high catalytic efficiencies for l-lactate (Table IV). The key factor making GOX3 more efficient with l-lactate than GOX1 and GOX2 is a 5- to 10-fold lower Km for the substrate (Table IV). This difference is key for understanding the physiological roles of the three enzymes (see below). Whereas the Km of GOX3 allows for 10% of maximum activity at l-lactate levels down to 84 µm, the corresponding 10% activity levels for GOX1 and GOX2 are at 550 and 980 µm, respectively. Consequently, of the three enzymes, only GOX3 can efficiently metabolize l-lactate at low intracellular concentrations.

GOX3 Preferentially Metabolizes l-Lactate in Vivo

To test whether GOX3 preferentially metabolizes glycolate or l-lactate in vivo, we performed an isotope tracer experiment in Arabidopsis leaves (Table V) as well as a substrate toxicity test in roots (Fig. 6, A and B). Both these experiments clearly showed that GOX3 preferentially metabolizes l-lactate in vivo. In the isotope-labeling experiment, the GOX3 overexpressor redistributed 2.7-fold more l-lactate-derived label than the GOX3 knockout. In comparison, the overexpressor only redistributed 1.5-fold more glycolate-derived label compared with the knockout. Also, in roots of the wild type, toxic levels of l-lactate can be metabolized whereas glycolate cannot.

GOX3 Is Not Directly Involved in Sustaining l-Lactate Levels during Waterlogging

As demonstrated in our biochemical and in vivo experiments, GOX3 functions as an l-lactate oxidase. GOX3 is expressed in roots, and its expression was never found to be modulated by any kind of hypoxic treatment in any species analyzed (Mustroph et al., 2014). We have confirmed these observations, as GOX3 activity did not change during the course of the hypoxic treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2). Furthermore, the root l-lactate levels in wild-type and gox3-1 plants during normoxia and hypoxia did not change considerably (Table VII). In addition, we experimentally confirmed that l-lactate is excreted to the medium after the onset of oxygen deprivation, and this excretion is higher in gox3-1 than in the wild type (Fig. 6C). This is very strong evidence that GOX3 is not directly involved in sustaining low intracellular l-lactate levels during hypoxia. In line with this, Arabidopsis wild-type, GOX3 loss-of-function, and overexpressor lines presented similar phenotypical characteristics following exposure to waterlogging: growth was quite slow, and the plants showed a premature senescence compared with the controls maintained under a normal watering regime (data not shown). Therefore, GOX3 must fulfill a different physiological role.

Loss of Function of GOX3 Induces Metabolic Rearrangements in Roots That Mirror Wild-Type Responses under Hypoxia

Adjustments of metabolite levels during hypoxia are adaptations to maximize energy production under limited reserves and vary between species and the kind of oxygen deficiency treatment (Mustroph et al., 2010, 2014; Narsai et al., 2011; Shingaki-Wells et al., 2011). We observed large metabolic rearrangements in the roots of Arabidopsis wild-type plants after 8 and 24 h of the hypoxic treatment applied in our work. The most important changes observed were the accumulation of sugars and sugar derivatives such as Fru, Glc, and myoinositol, the amino acids Ala, β-Ala, GABA, Glu, Met, and Phe, and also Gly, 2-hydroxyglutarate, and oxalate.

The above-mentioned sugars and sugar derivatives function as compatible solutes involved in stabilizing subcellular structures under stress conditions. In addition to this, Gly and β-Ala are involved in the synthesis of compatible solutes. As shown for some species, the synthesis of β-Ala betaine does not require oxygen; thus, it is a suitable osmoprotectant under hypoxic stress (Hanson et al., 1991; Rathinasabapathi et al., 2000). These osmolytes may also serve as valuable storage compounds for reducing power, carbon, and/or nitrogen upon relief from the stress imposed by oxygen deficiency (Majumder et al., 2010). Interestingly, under normoxia, roots of gox3-1 accumulate Fru, Glc, myoinositol, and β-Ala to levels similar to those found in the wild type under hypoxia. Moreover, Pro, a prominent compatible solute, shows higher levels in gox3-1 under hypoxia and a clear tendency to higher levels in normoxia than in the wild type.

It is well established that Ala and GABA accumulate in different plant organs as a consequence of oxygen deficiency of different grades imposed by either waterlogging or submergence (Branco-Price et al., 2008; Mustroph et al., 2009, 2010; Narsai et al., 2009, 2011; van Dongen et al., 2009; Rocha et al., 2010a; Nakamura et al., 2012; Barding et al., 2013). In line with these reports, we observed an accumulation of Ala and GABA in roots of wild-type Arabidopsis under long-term hypoxia. In this condition, Ala and GABA may function as carbon and nitrogen stores, which could be transported to shoots for recycling or would be readily interconvertible upon reoxygenation (de Sousa and Sodek, 2003; Mustroph et al., 2014). Indeed, upon reoxygenation, we observed that the relative levels of Ala and GABA returned to normoxia levels (Supplemental Table S2). The metabolism of GABA enables the reuse of the carbon stored in this metabolite by channeling it into the tricarboxylic acid cycle via succinate (the GABA shunt; Bouché and Fromm, 2004; Fait et al., 2008). It has been hypothesized that, under hypoxic conditions, GABA may accumulate as a result of its low catabolism through GABA transaminase and/or the succinic semialdehyde degradation pathways (Mustroph et al., 2014). On the other hand, Ala may be produced through the action of Ala aminotransferase, the expression of which responds to hypoxia (Rocha et al., 2010b). This enzyme converts pyruvate and Glu into Ala and 2-oxoglutarate (Liepman and Olsen, 2003). We found that, in gox3-1 roots, Ala and GABA accumulate under normoxia to levels higher than in the wild type. Especially, the levels of GABA were similar to those of the wild type under hypoxia (Table VII). These high levels of Ala and GABA may thus represent adjustments to maximize the recycling of carbon and/or nitrogen in plants lacking an active GOX3.

d-2-Hydroxyglutarate derives from Lys, especially in conditions of higher protein catabolism, and is oxidized in plant mitochondria to 2-ketoglutarate through d-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (Engqvist et al., 2009, 2011; Araújo et al., 2010; Kuhn et al., 2013). The increased amounts of 2-hydroxyglutarate observed in wild-type and gox3-1 plants under hypoxia suggest an enhanced protein turnover under this condition. Higher amounts of amino acid markers of protein degradation, such as Ile, Leu, Val, and Phe, during the hypoxic treatment support this hypothesis. The increment in Glu levels during hypoxia may be a consequence of the enhanced production and decarboxylation of 2-ketoglutarate. In turn, the high amounts of Glu may explain the high accumulation of GABA during hypoxia.

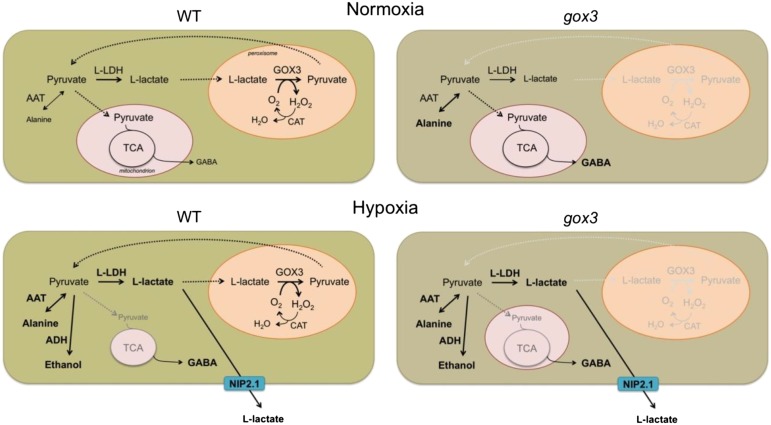

GOX3 May Ensure the Sustainment of Low Levels of l-Lactate after Its Formation in Normoxic Conditions

Taken together, we propose a paradigm in which GOX3 may fulfill a similar function to CYB2 in yeast, the conversion of l-lactate to pyruvate to ensure the sustainment of low levels of l-lactate in roots after its formation in normoxic conditions (Fig. 7). In the absence of GOX3, pyruvate utilization is rerouted to the formation of Ala. This would also explain the lower relative levels of lactate observed in gox3-1 with respect to the wild type in our assay. As there is no other enzymatic activity able to catalyze the oxidation of l-lactate back to pyruvate in plants, it is conceivable that, when a threshold level of l-lactate is exceeded, as occurs under oxygen deprivation, the action of GOX3 is resumed by NIP2.1. Indeed, we show that l-lactate is excreted to the medium after the induction of hypoxia and that the excretion of l-lactate is higher in gox3-1 than in the wild type.

Figure 7.

Model explaining the participation of GOX3 in root l-lactate metabolism. In the absence of GOX3, pyruvate utilization is rerouted to the formation of Ala. This mimics the situation under hypoxia, where GABA also accumulates. CAT, Catalase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; WT, wild type.

No doubt, future experiments will provide additional evidence to elucidate the exact mechanisms underlying the participation of GOX3 in Arabidopsis root physiology and leaf aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of GOX1, GOX2, and GOX3 Complementary DNAs in an Expression Vector

Full-length coding sequences of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) GOX1 and GOX3 were obtained through PCR amplification with Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) using as template RNA extracted from leaves in the case of GOX1 and from roots in the case of GOX3. The oligonucleotide primers used, designed to introduce XhoI sites at both ends of GOX1 and BamHI sites at both ends of GOX3, were as follows: GOX1-F (5′-TACTCGAGATGGAGATCACTAACGTTACCGA-3′) and GOX1-R (5′-ATCTCGAGGCTCAGCCTATAACCTGGCTGAAGGACGT-3), and GOX3-F (5′-GGATCCGATGGAGATAACAAACGTGATGGA-3′) and GOX3-R (5′-GGATCCCTACAGCTTGGCCGAGAGG-3). The amplified products were cloned into pCR-BluntII-TOPO (Invitrogen), and the generated plasmids were sequenced to confirm their correctness. The inserts were cut out using the introduced restriction sites and ligated into the pET16b vector (Novagen) linearized with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting expression vectors, pET-16b-GOX1 and pET-16b-GOX3, were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BLR DE3 pLysS (Novagen). The vector pET-28a-GOX2, kindly provided by Dr. Martin Hagemann (University of Rostock), was used for the heterologous expression of GOX2 in the E. coli strain Rosetta cells (Novagen).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant GOX Proteins

The vectors pET16b-GOX1, pET-28a-GOX2, and pET16b-GOX3 generate fusion proteins with an N-terminal His tag facilitating the purification of the recombinant proteins. The cells transformed with the vectors were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C and agitation at 220 rpm in the presence of 50 µg mL−1 carbenicillin, 50 µg mL−1 chloramphenicol, and, in the case of BLR cells, an additional 5 µg mL−1 tetracycline. These precultures were used to inoculate fresh Luria-Bertani medium in a ratio of 1:50. The cultures were grown at 37°C in an orbital shaker at 220 rpm until the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6. GOX1 expression was induced by the addition of 0.1 mm IPTG, and the culture was transferred to room temperature and grown for 20 h before harvesting. GOX2 and GOX3 expression was induced by the addition of 1 mm IPTG, and the culture were grown at 37°C for 4 h before harvesting. Cells expressing GOX1, GOX2, or GOX3 were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000g for 10 min, resuspended in 35 mL of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8) containing 500 mm NaCl, 2 mg of DNase, 2 mg of RNase, 2 mg of lysozyme, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.5 mg mL−1 phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, sonicated, and centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min at 4°C to remove debris. The supernatant was used for protein purification using immobilized metal ion chromatography on Ni2+-nitriloacetic acid agarose (Qiagen). The column was equilibrated with wash buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 500 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT) containing 40 mm imidazole and washed once with the same buffer and afterward with wash buffer containing 80 and 100 mm imidazole. The protein was eluted using 1 mL of 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 500 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 300 mm imidazole. To remove imidazole, the protein samples were run through a NAP5 column and eluted with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, and 1 mm DTT. The purified enzymes were used immediately for the kinetic measurements.

Enzymatic Activities

All enzyme assays were conducted at 25°C using a Tecan Infinate 200 plate reader (Tecan Deutschland) in combination with the Magellan data analysis software (Tecan Austria). The oxidase activity assays were conducted according to a modified protocol (Feierabend and Beevers, 1972). The standard reaction mixture contained 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm substrate, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.01 mm FMN, 5 mm MgCl2, and 4 mm phenylhydrazine in a final volume of 0.2 mL. As oxidases, the enzymes use molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor. The product of the reaction, the oxoacid of the substrate, reacts with the phenylhydrazine to the phenylhydrazone product, detected at 324 nm. The extinction coefficients are 17 cm−1 mm−1 for the glyoxylate phenylhydrazone and 10.4 cm−1 mm−1 for the pyruvate phenylhydrazone. Activities of the enzymes as dehydrogenases were assayed in a reaction mixture containing 100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm substrate, 0.5 mm EDTA, 0.01 mm FMN, 5 mm MgCl2, 200 µm DCIP, and 3 mm phenazine methosulfate (PMS) in a final volume of 0.2 mL. The activities were measured by following the reduction of DCIP at 600 nm (22 cm−1 mm−1). For each measurement, 1 to 5 μg of purified enzyme was used. A baseline was determined by monitoring for 4 min before the reaction was started by the addition of the substrate.

Electron Acceptor Analysis

The electron acceptors of the enzymes were evaluated using the standard reaction mixes and varying the type of electron acceptor and detection wavelength. The different electron acceptors used were molecular oxygen (detected at 324 nm; extinction coefficient = 17 cm−1 mm−1), 200 µm cytochrome c (detected at 550 nm; extinction coefficient = 18.6 cm−1 mm−1), or 200 µm DCIP used together with 3 mm PMS or 1 mm NAD or NADP (detected at 340 nm; extinction coefficient = 6.22 cm−1 mm−1).

pH Optimum and Substrate Screening

The pH optima of GOX1 to GOX3 acting as oxidases and dehydrogenases were determined by varying the pH of the buffer between 6 and 9.5. Activities were measured spectrophotometrically using the standard reaction mixtures and either 10 mm glycolate or l-lactate as substrate.

The substrate specificities of the enzymes were assayed using standard reaction mixtures at pH 7.5 and either 5 mm of short- and medium-chain 2-hydroxy acids dissolved in water (glycolate, l-lactate, d-lactate, leucic acid, valic acid, or isoleucic acid) or 0.5 mm of other long-chain 2-hydroxy fatty acids (2-hydroxyhexanoic acid, 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid, 2-hydroxydodecanoic acid, or 2-hydroxyhexadecanoic acid) dissolved in ethanol.

Determination of Kinetic Constants

The catalytic constants Km, Vmax, and kcat for the substrates glycolate and l-lactate were determined in the standard reaction mixture at pH 7.5 using molecular oxygen (oxidase reaction) or PMS and DCIP (dehydrogenase reaction) as electron acceptors. The concentration of the substrates was varied from 0 to 37.9 mm, while the concentrations of the other components were kept constant. The kinetic constants were calculated with at least three different enzyme batches, each containing at least triplicate determinations, and fitted to nonlinear regression to the Michaelis-Menten equation f(x) = ax/b + x (Sigma Plot software). One unit of enzyme activity is defined as the amount that oxidizes 1 mol of substrate min−1.

The determination of the catalytic constants Km, Vmax, and kcat for the molecular oxygen of GOX1 and GOX3 was conducted with a Clark electrode in combination with the Logger Pro (measurements) and Logger Lite (evaluation) software (Vernier Software and Technology). The standard reaction mix was pipetted onto the calibrated oxygen electrode without the substrate. Basal oxygen consumption was measured for approximately 2 min, then glycolate or l-lactate was added, and the oxygen consumption was recorded until the slope reached that of the basal oxygen consumption. Measurements were conducted with three substrate concentrations, 5, 7.5, and 10 mm, and using 1 and 5 mg of enzyme. The rates of oxygen consumption and the respective oxygen concentrations were determined every 30 s beginning with the highest rate of oxygen consumption. As the kinetics showed a sigmoidal course, the constant describing the substrate concentration at which half of the enzyme is saturated (S0.5) was determined using the nonlinear regression fit to the sigmoidal Hill equation f(x) = axb/cbxb (Sigma Plot software).

Separation and Analysis of the Prosthetic Group

The characterization of the prosthetic group of GOX1 to GOX3 was performed as described by Engqvist et al. (2009).

Subcellular Localization Studies of GOX3

The above-amplified GOX3 full-length coding sequence was cloned into pENTR4 and subsequently sequenced. This entry vector was used in a Gateway LR recombination reaction with LR clonase (Invitrogen) with the vector pENSGYFP to generate an N-terminal YFP translational fusion (pENSG-YFP-GOX3). This construct and the peroxisomal control CFP-PTS1 (Linka et al., 2008) were transformed into the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains GV3101 pMP90 RK and GV3101 pMP90, respectively, using standard protocols. Transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana was performed by injecting recombinant agrobacteria into the apoplast of whole leaves as described previously (Wydro et al., 2006). Three days after infiltration, protoplasts were prepared following a modified protocol (Yoo et al., 2007). Briefly, 10 leaf discs of 0.75-mm diameter were digested in enzyme solution, and protoplasts were pelleted by gravitation, resuspended, and analyzed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy using an LSM700 microscope in combination with the ZEN software (Zeiss).

PAGE and Protein Determination

Denaturing SDS-PAGE was performed using 12.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels according to Laemmli (1970). Native PAGE was performed employing 8% (w/v) PAGE. Electrophoresis was run at 100 V and 4°C. Proteins were visualized with Coomassie Blue or electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. For western blots, the membrane was incubated either with anti-His antibodies (Qiagen) or GOX3-specific antibodies. Bound antibodies were visualized using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma). Gels were also assayed for activity by incubation in the dark at 30°C with 50 mm K2PO4, pH 8.75, 5 mm substrate, 0.05% (w/v) nitroblue tetrazolium, and 150 μm PMS in a final volume of 5 mL. Protein concentration was determined according to the method of Bradford (1976).

Screening for GOX3 T-DNA Insertion Lines and Genotyping

Seeds of the T-DNA insertion lines GABI_523D09 (gox3-1), SALK_020909 (gox3-2), and SAIL_1156_F03 (gox3-3) were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (http://www.arabidopsis.info/). Plants homozygous for the insertion were isolated and confirmed by two sets of PCRs using genomic DNA as a template. The first PCR was performed using primers GOX3F1 (5′-TGGTGGATAATTGCAGACGA-3′) and GOX3R1 (5′-AACAGGGGAAATGACAAGAGC-3′), GOX3F1 and GOX3R2 (5′-CAGCTTGGCCGAGAGGTA-3′), and GOX3F2 (5′-TCGAGCCAAAGATCATGATTC-3′) and GOX3R3 (5′-AGGCCTAAATCTGTTTCCAGC-3′), which are specific for the wild-type gene in gox3-1, gox3-2, and gox3-3, respectively. The second PCR was carried out with the T-DNA left border primer GABI-LB (5′-ATAATAACGCTGCGGACATCTACATTTT-3′) in combination with GOX3F1, the T-DNA left border primer SALK-LB (5′-GTCCGCAATGTGTTATTAAGTTGTC-3′) in combination with GOX3F1, and the T-DNA left border primer SAIL-LB (5′-TAGCATCTGAATTTCATAACCAATCTCGATACAC-3′) in combination with GOX3R3, in the cases of gox3-1, gox3-2, and gox3-3, respectively. To further determine whether native GOX3 transcript was absent in the insertional mutants, total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of leaves using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco-BRL). RNA was converted into first strand complementary DNA (cDNA) using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCRs were conducted in a final volume of 10 µL using 1 µL of the transcribed product and Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). The primers used were GOX3F and GOX3R. As control, the ACTIN2 gene was amplified by 28 cycles using the following primers: Actin-F (5′-TGCGACAATGGAACTGGAATG-3′) and Actin-R (5′-GGATAGCATGTGGAAGTGCATAC-3′).

Quantitative PCR