Analysis of the mechanisms, regulation, and consequences of protein SUMOylation in plants and other eukaryotes highlights the conservation and importance of this process across taxa.

Abstract

Posttranslational modification of proteins by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) has received much attention, reflected by a flood of recent studies implicating SUMO in a wide range of cellular and molecular activities, many of which are conserved throughout eukaryotes. Whereas most of these studies were performed in vitro or in single cells, plants provide an excellent system to study the role of SUMO at the developmental level. Consistent with its essential roles during plant development, mutations of the basic SUMOylation machinery in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) cause embryo stage arrest or major developmental defects due to perturbation of the dynamics of target SUMOylation. Efforts to identify SUMO protein targets in Arabidopsis have been modest; however, recent success in identifying thousands of human SUMO targets using unique experimental designs can potentially help identify plant SUMO targets more efficiently. Here, known Arabidopsis SUMO targets are reevaluated, and potential approaches to dissect the roles of SUMO in plant development are discussed.

Protein structure, and hence function, is determined not only by the primary amino acids sequence dictated by its gene sequence, but also by the many modifications they receive co- and posttranslationally. Some of these modifications involve chemical changes of amino acids (such as citrullination, deamidation, and racemization), whereas others involve structural changes in proteins (such as formation of disulfide bridges and the maturation of a precursor protein by proteotytic cleavage). Other modifications involve addition of functional groups, such as in the cases of acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, etc., or even sometimes other peptides. These modifications result in different topologies and activities of mature proteins and hence increase the repertoire of cellular proteins tremendously and provide a vast source of variation beyond that determined at the DNA or RNA levels. Many of these modifications are reversible, and their effects, albeit crucial for normal growth, development, and response to environmental cues, might be subtle, presenting challenges for studies attempting to correlate these modifications with phenotypes. One such posttranslational modification involves the covalent attachment (conjugation) of a family of small proteins to target proteins. Ubiquitin is the founding member of these small protein modifiers; however, a superfamily of more than 12 ubiquitin-like (UBL) proteins have been characterized and shown to regulate various aspects of cellular activity through modulation of protein structure and function (Hochstrasser, 2009; Vierstra, 2012). Although they share only low similarity at the primary amino acid sequence, these protein modifiers share a conserved three-dimensional structure as well as similar overall enzymatic reactions that lead to their conjugation and deconjugation to target proteins (Vierstra, 2012), suggesting that they probably have an ancient and common origin. Consistent with this idea, the bacterial proteins ThiS and MoaD, which act as sulfur donors during the synthesis of Thiamine and Molybdenum cofactor, are structurally related to ubiquitin, and the enzymes required for their activation (ThiF and MoeB, respectively) are related to the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1; Fig. 1; see discussion below; for review, see Hochstrasser, 2009). Recent evidence reveals that a simple, but complete, ubiquitin system is present in three extant archaeal groups and hence proposes a preeukaryotic origin of the UBLs (Grau-Bové et al., 2015). During the evolution of eukaryotes, this system expanded greatly to give rise to all known UBLs and their conjugation and deconjugation enzymes, including those for small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO), and it is believed that all these modifications existed in the last eukaryotic common ancestor (Grau-Bové et al., 2015). The ancient origins of these protein modification systems may explain why many of the cellular processes they regulate are conserved throughout eukaryotes. Attachment of ubiquitin and SUMO, specifically, play crucial roles in eukaryotic growth and development, and these two UBLs are the most important and extensively studied of all small protein modifiers. Interestingly, the evolutionary routes that the UBL system followed, particularly those of ubiquitin and SUMO, seem to have involved different mechanisms during the evolution of plants and other eukaryotes from their common eukaryotic ancestor, pointing to potential differences specific to plants while conserving core molecular and cellular processes regulated by these UBLs (Grau-Bové et al., 2015; N. Elrouby and S.R. Strickler, unpublished data).

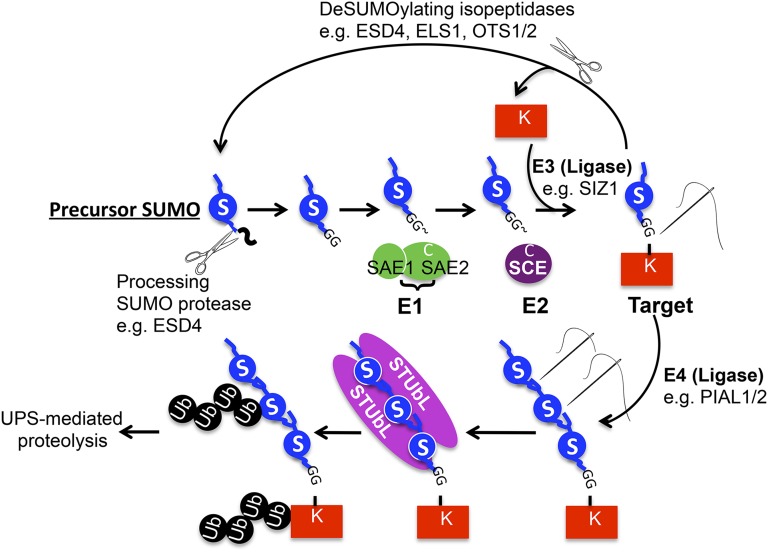

Figure 1. The SUMO conjugation and deconjugation system. SUMO is produced as a precursor protein with a C-terminal extension. SUMO proteases cleave off the C-terminal tail to expose the reactive carboxyl group of the C-terminal Gly. The SAE (or El) with its two subunits (SAE1 and SAE2) forms a thioester bond with this Gly residue to prepare for its transfer to the SCE (or E2). In addition to the thioester bond, the SCE binds SUMO noncovalently as well and eventually transfers SUMO to a target protein, usually with the aid of a third enzyme (E3), the SUMO ligase such as SIZ1. Targets, now covalently modified by SUMO through an isopeptide bond, perform specific functions, which are subsequently terminated by either removing SUMO from the target protein (deconjugation) or by regulated proteolysis. SUMO proteases with isopeptidase activity specifically and precisely hydrolyze the isopeptide bond, releasing free SUMO and target protein. Alternatively, a polySUMO chain forms through the activity of SUMO ligases (E4) such as PIAL1 and PIAL2, and this chain recruits STUbLs, which ubiquitinate both SUMO and the target protein and target them for degradation by the 26S proteasome. All gene models are derived from terminology in Arabidopsis. S, SUMO; Ub, ubiquitin; UPS, ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The enzymatic reactions that lead to the attachment of ubiquitin or SUMO to target proteins are very similar (Fig. 1). SUMO is produced as a precursor protein that contains two (in most SUMO isoforms) Gly residues near its C-terminal end (Novatchkova et al., 2004). A processing SUMO protease cleaves off the C-terminal end of the SUMO precursor to expose the reactive carboxyl group of the second Gly. Through an ATP-dependent pathway that involves three enzymatic activities (E1→E2→E3), the C-terminal end of mature SUMO eventually forms an isopeptide bond with the ε-amino group of a Lys residue in the target protein (Fig. 1; Dohmen, 2004). Target modification leads to a variety of effects (discussed below) that mainly regulate target protein activity, subcellular location, and interaction dynamics. However, unlike modification by ubiquitin (ubiquitination), which mainly leads to target degradation by a specialized multisubunit protease called the 26S proteasome, there is no evidence linking SUMOylation directly to target proteolysis (in some cases, modification of a protein by a polySUMO chain may lead to its ubiquitination, which itself targets the protein for degradation [see below]; Geiss-Friedlander and Melchior, 2007). Because most of our knowledge of the enzymology, structural biology, and functional implications of SUMOylation is derived from work performed in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and mammalian cell lines, this article updates our knowledge of the field in general, with emphasis on relevant data from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) whenever possible and a focus on SUMO protein targets. Plants provide an ideal model system to study the roles of SUMO during development, and hence knowledge gleaned from studies of yeast and human SUMO may provide guidelines that will help advance our understanding of the roles of SUMO in plant development.

THE SUMO CONJUGATION AND DECONJUGATION SYSTEM

Consistent with the expansion of the SUMO system in plants, the Arabidopsis (Columbia-0) genome contains eight genes encoding SUMO and a ninth pseudogene (Novatchkova et al., 2012). SUMO1 and SUMO2 are both highly related and expressed, and their concomitant inactivation (double knockouts) is embryo lethal (Saracco et al., 2007), while overexpression of either gene causes defects in abscisic acid-mediated growth inhibition (Lois et al., 2003). Loss of SUMO3 function suggests that it is not essential, but it causes late flowering, whereas its overexpression causes early flowering and activates plant defense mechanisms (van den Burg et al., 2010). We do not know much about the expression and function of the five remaining SUMO genes. On the other hand, SUMO is encoded by a single gene in yeast (Suppressor of mif two3 [Smt3]), whereas the human genome encodes three conjugatable isoforms (SUMO1–SUMO3) and a fourth isoform (SUMO4) whose ability to attach to target proteins is not clear (Dohmen, 2004).

In Arabidopsis, the SUMO protease EARLY IN SHORT DAY4 (ESD4) was found to both process precursor SUMO and to be the major isopeptidase (Fig. 1; Murtas et al., 2003). Mutations of ESD4 cause pleiotropic effects, with defects in flowering time, root and shoot architecture, leaf size and shape, stature, fertility, and a plethora of physiological defects (Reeves et al., 2002; Villajuana-Bonequi et al., 2014; N. Elrouby, unpublished data). Following maturation of a precursor SUMO molecule, its C-terminal Gly is conjugated to a target protein via an enzymatic cascade. The first enzyme of the conjugation pathway (E1 or SUMO-activating enzyme [SAE]) consists of two subunits (SAE1 and SAE2), the larger of which contains the active Cys that forms a thioester bond with the C-terminal Gly of mature SUMO to activate it (Fig. 1; Castaño-Miquel et al., 2013). SUMO is then transferred onto the Cys residue of the single subunit of the SUMO-conjugating enzyme (E2 or SCE), which also interacts with SUMO and its potential target via noncovalent interactions, allowing the eventual transfer of SUMO to the ε-amino group of a target Lys (Bernier-Villamor et al., 2002). A third enzyme (E3), the SUMO ligase, plays crucial roles in target specificity and interacts with the target, the SUMO E2, and SUMO to facilitate SUMO’s transfer from the E2 to the target (Yunus and Lima, 2009). In Arabidopsis, the SAE and SCE activities are encoded by single genes (SAE1 is represented by two genes, but SAE2 is encoded by only one gene), and null mutations lead to embryonic lethality (Saracco et al., 2007; Castaño-Miquel et al., 2013). On the other hand, several ligases have been identified in Arabidopsis, including the main E3 ligases SAP and MIZ (SIZ1) and METHYLMETHANE SULFONATE SENSITIVITY21 (MMS21)/HIGH PLOIDY2 (HPY2). Like mutants of the SUMO protease ESD4, siz1 mutants are pleiotropic and exhibit similar defects, including early flowering, reduced fertility, shortened stature, and altered physiological responses (Miura et al., 2005, 2009; Catala et al., 2007; Saracco et al., 2007). Mutants of MMS21/HPY2 exhibit a shortened root phenotype due to defects in DNA damage repair of root stem cells (Huang et al., 2009; Ishida et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2013).

SUMOylated proteins are recycled in one of two ways (Fig. 1). SUMO may be deconjugated using a variety of isopeptidases that likely target different SUMOylated proteins and may thus contribute to the specificity of the SUMO system. Many SUMO isopeptidases were informatically identified in Arabidopsis; however, only a few have been studied (Hoen et al., 2006; Novatchkova et al., 2012). These include ESD4 and ESD4-Like SUMO protease (ELS1) as well as OVERLY TOLERANT TO SALT1 (OTS1) and its paralog OTS2. As stated earlier, esd4 mutants exhibit strong pleiotropic phenotypes; however, mutants of its closest relative ELS1 exhibit much milder defects (Hermkes et al., 2011), and those of OTS1 and OTS2 have reduced tolerance to salinity (Conti et al., 2008). Plants seem to have expanded the SUMO protease family to numbers much higher than those present in other eukaryotes. This includes four more uncharacterized Arabidopsis genes and more than 90 others that were amplified as a result of transposon activity (Hoen et al., 2006; Novatchkova et al., 2012). In addition, another class of SUMO proteases that were initially annotated as deubiquitinating enzymes were found to possess SUMO isopeptidase activity only (hence termed deSUMOylating isopeptidases [DeSIs]; Shin et al., 2012). Two DeSI genes were found in mammals, whereas Arabidopsis seems to have eight to nine orthologs (N. Elrouby, unpublished data).

Another route that SUMOylated proteins may take is through regulated proteolysis. Instead of recycling SUMO through deconjugation by SUMO isopeptidases, additional SUMO moieties are added to form a polySUMO chain that acts as a binding domain for a group of ubiquitin E3 ligases called SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs; Uzunova et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2007; Tatham et al., 2008). Two genes, PROTEIN INHIBITOR OF ACTIVATED STAT LIKE1 (PIAL1) and PIAL2, were recently identified in Arabidopsis and found to encode SUMO E4 ligase activities responsible for polySUMO chain formation (Fig. 1; Tomanov et al., 2014). On the other hand, Arabidopsis contains at least six STUbLs, including two that are conserved throughout eukaryotes and are the evolutionary and functional equivalents of the mammalian and yeast STUbLs RING Finger Protein4 (RNF4) and Synthetic lethal gene8 (Slx8; Elrouby et al., 2013; N. Elrouby and S.R. Strickler, unpublished data). Mutations in one of the Arabidopsis STUbLs (AT-STUbL4) delay flowering, probably due to impaired degradation of a floral repressor called Cyclin Dof Factor2 (CDF2), because overexpression of AT-STUbL4 reduces CDF2 abundance and accelerates flowering (Elrouby et al., 2013). STUbLs bind polySUMO chains noncovalently through their multiple SUMO interaction motifs (SIMs), which mediate their dimerization, a feature essential for their activity and the eventual polyubiquitination of both SUMO and its attached targets (Fig. 1; Plechanovová et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2014). These polyubiquitinated proteins are then targeted for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Fig. 1; Uzunova et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2007; Tatham et al., 2008).

TARGET MODIFICATION BY SUMO: IMPLICATIONS AND FUNCTIONS

Interestingly, except for very few proteins, it is believed that only a very small fraction of a cellular protein pool is SUMOylated at any point of time (estimates were given at <1% in yeast, and similar estimates are predicted for other eukaryotes; Johnson, 2004). The remarkable effects of protein SUMOylation on cellular and organismal growth and development are, hence, mind-boggling. It is possible that the low-level SUMOylation primes a different state of modification in response to certain stimuli. For example, starting from this basal SUMOylation state, target SUMOylation may then be enhanced or may spread to other related proteins. Consistent with this, heat stress that induces massive target SUMOylation in both cell culture and whole organisms (including plants) does not necessarily cause de novo SUMOylation but rather changes the SUMOylation levels of proteins already SUMOylated, as has been shown in Arabidopsis (Miller et al., 2013). Similarly, studies in yeast suggest that DNA damage leads to the activation of a repair pathway and induces a SUMOylation wave leading to modification of several proteins involved in this pathway (Psakhye and Jentsch, 2012). Another scenario, which is not necessarily mutually exclusive with that discussed above, is that the need for the SUMOylated form of a protein may be restricted to a very specific time window, in only specific cell types, and/or a specific state of the protein, and hence the level of the SUMOylated protein relative to that of the whole protein pool is often low. Mitotic and repair proteins are good examples where targets are modified only during the mitotic phase of dividing cells or only during DNA repair (Jackson and Durocher, 2013; Pelisch et al., 2014). The reversible nature of protein SUMOylation may contribute to this process. For example, mammalian thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG), which is involved in base mismatch repair, does not require SUMO modification to bind DNA or for its activity to repair the base mismatch; however, SUMO modification of DNA-bound TDG leads to its release from DNA, allowing its recycling to other mismatch sites (Hardeland et al., 2002; Baba et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2005). Once it is released from DNA, it is deSUMOylated by SUMO isopeptidases. Thus, SUMO modifies only one state of TDG (DNA bound), transiently and only when and where base mismatch repair is needed, while most of the protein pool (bound or unbound to DNA) is unmodified. Although this level of detail is not available for the Arabidopsis homolog of TDG (DEMETER), it is similarly modified by SUMO (both covalently and noncovalently), and the mechanism of its regulation by SUMO is likely conserved in plants as well (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Elrouby et al., 2013). In a third scenario, low-level SUMOylation may be required for normal protein homeostasis (proteostasis) in the cell. Proteostasis is a term that describes the collective cellular forces that regulate the biogenesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation of proteins and hence the steady-state levels of cellular proteins. Recent evidence points to a role for SUMO in the activity of proteins, such as the AAA-ATPase Cell division cycle48 (Cdc48, also known as p97) and the nuclear pore complex protein Translocated promoter region (Tpr; Schweizer et al., 2013; Franz et al., 2014). Interaction with SUMO and the recruitment of SUMO proteases and STUbLs have been suggested to contribute to the degradation of proteins at the nuclear pore and during DNA repair (Schweizer et al., 2013; Franz et al., 2014). A role for SUMO in proteostasis was also clearly demonstrated in a recent study suggesting that the promyelocytic leukemia protein nuclear bodies (PML-NBs; there is no evidence for their formation in plants), which are a major SUMO target in mammals and require SUMO modification for their assembly, also possess SUMO E3 activity that SUMOylates misfolded proteins and recruits the mammalian STUbL RNF4 to ubiquitinate and degrade these proteins through the ubiquitin-proteasome system (Guo et al., 2014). Deciphering the enigmatic effects of protein SUMOylation is likely to occupy the scientific community for decades to come, and the low levels of target SUMOylation may pose a challenge toward this goal.

The crucial roles of SUMO during cellular and organismal development are suggested by the phenotypes associated with mutants of the SUMO conjugation and deconjugation cycle in plants and the essential nature of SUMO in yeast and cell cultures. Although little is known about the exact mechanisms with which SUMO regulates these functions, there are several main categories of molecular and cellular processes in which SUMO is heavily implicated. These include its regulation of interaction dynamics and assembly of multiprotein complexes, its role in transcriptional control, and its influence on chromatin activity. There is evidence for roles in RNA biology, abiotic stress (especially in response to heat), biotic stress, and a multitude of other processes; however, other than identification of targets implicated in these processes, we have little mechanistic clues for their regulation by SUMO.

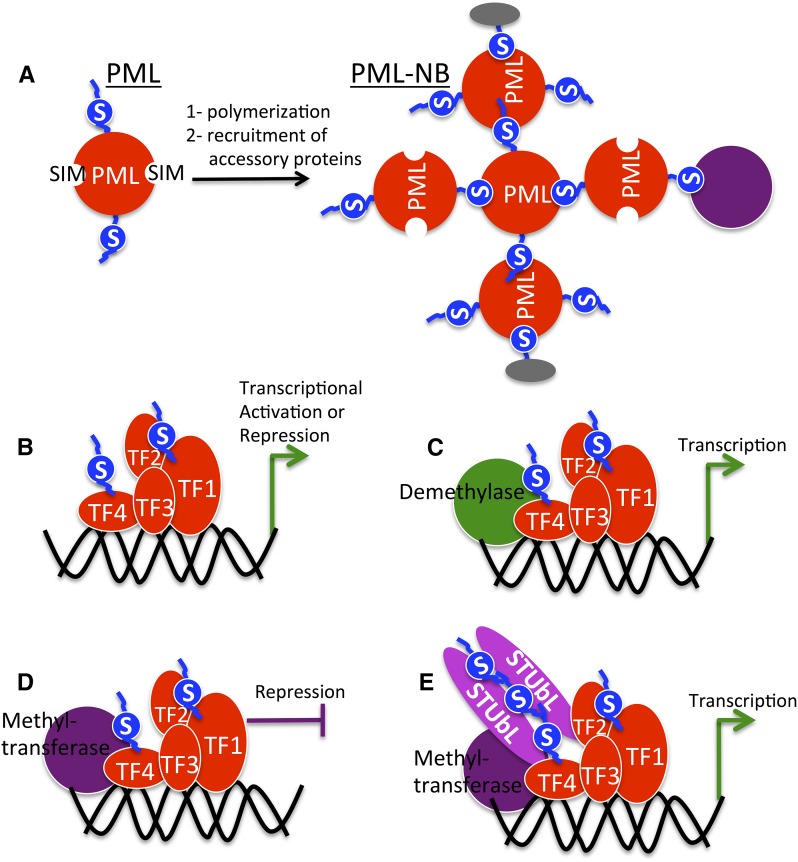

A role for SUMO in assembly of protein complexes is exemplified by its involvement in the formation of nuclear bodies containing the PML protein at their core (PML-NB). Although PML-NBs have not been identified in plants, discussing the role of SUMO in their assembly helps explain how it may mediate the formation of protein complexes, a role likely to be conserved throughout eukaryotes. Through covalent and noncovalent interactions, SUMO acts as a scaffold to mediate assembly of PML-NB and associated proteins (Fig. 2). The PML protein itself is covalently modified by SUMO and also contains at least three SIMs (Fu et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2006). This allows both its polymerization and the recruitment of other proteins through interaction with SUMO (Fig. 2). Not much is known about the role of SUMO in multiprotein complex assembly in plants; however, SUMOylation of several members of the Arabidopsis TOPLESS corepressor complex has been reported (Miller et al., 2010), implying that SUMO may play a role in complex assembly. Additionally, a recent study that identified Arabidopsis SUMO-interacting proteins (SIPs; proteins that interact with SUMO noncovalently) implicates SUMO in protein complex assembly on chromatin (Elrouby et al., 2013). Recruitment of one of these SIPs, AT-STUbL4, to the CDF repressor complex is implied and suggested to play a role in lifting the repressor effects from, and consequently promoting the expression of, CONSTANS, the central player in photoperiod flowering (Fig. 2; Elrouby et al., 2013). The identification of several Arabidopsis chromatin-modifying proteins (histone and DNA methyltransferases and demethylases) by their interaction with SUMO also suggests that these proteins are likely recruited to SUMOylated transcription factors or histones by their interaction with SUMO, allowing the assembly of these chromatin modification complexes (Elrouby et al., 2013; Elrouby, 2014). It is likely, thus, that SUMO plays important roles in mediating interactions and recruiting components of protein complexes.

Figure 2.

SUMO is involved in protein complex assembly. A, PML protein (red) forms nuclear bodies called PML-NBs that assemble in normal mammalian nuclei and are important for DNA repair, apoptosis, and viral resistance. They include, in addition to the PML protein, additional accessory proteins (gray and purple). Complex assembly relies heavily on covalent and noncovalent interactions with SUMO (blue). B to E, SUMO is also important in the assembly of transcriptional regulator complexes. B, SUMOylation of transcriptional factors (TFs; red) may be important for their activity and/or assembly on chromatin by recruiting other transcriptional factors containing SIMs. C and D, SUMOylated transcription factors may also recruit chromatin-modifying proteins (e.g. demethylases or methyltransferases) by covalent or noncovalent interactions, leading to transcriptional activation or repression. E, STUbLs may also be recruited to polySUMOylated proteins such as transcriptional factors, and this leads to their degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system, introducing another layer of transcriptional regulation. Depiction of protein complex assembly on chromatin is based on data from yeast, metazoans, and Arabidopsis. Specific examples are indicated in the text.

SUMO plays a prominent role in transcriptional control. The great majority of SUMO targets throughout eukaryotes are nuclear proteins (Geiss-Friedlander and Melchior, 2007; Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Hendriks et al., 2014). Studies in mammalian cells suggest that inducing ectopic SUMOylation by targeting SUMO and its conjugating enzyme (E2) to gene promoters leads to repression of gene expression (Shiio and Eisenman, 2003; Chupreta et al., 2005; Savare et al., 2005). On the other hand, depleting cells of SUMO or E2, or overexpression of SUMO isopeptidases, which all lead to reduced protein SUMOylation, enhances gene expression (Ross et al., 2002; Ouyang et al., 2009; Spektor et al., 2011). Although these studies suggest that protein SUMOylation might be associated with repression of gene expression, the role of SUMO in transcriptional control is not so simple. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies in yeast revealed the association of SUMO and the SUMO E2 with constitutively active and inducible promoters (Rosonina et al., 2010). Additionally, a recent elegant and comprehensive study was performed in proliferating and senescent human fibroblasts using chromatin immunoprecipitation to identify genome-wide association sites of several SUMO isoforms, SUMO machinery enzymes, different histone and chromatin marks, and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) and combined this with genome-wide expression profiling (Neyret-Kahn et al., 2013). This study revealed the association of either SUMO1 or SUMO2 with the transcriptional start sites (TSSs) of approximately 7,700 genes, and of these genes, 67% were significantly expressed. SUMO is associated with a region immediately upstream of the TSS in a nucleosome-depleted region where the transcriptional preinitiation complex forms, whereas Pol II is found 30 to 50 nucleotides downstream from the TSS. Quantitatively, a positive correlation was found between expression levels and SUMO and Pol II occupancy, suggesting that SUMOylation is generally correlated with transcriptional activation at Pol II promoters (Neyret-Kahn et al., 2013). The same study also revealed that although active promoters are major sites for SUMO1/SUMO2 binding, SUMO is also associated with repressive histone 3 lysine 27 trimethyl and histone 3 lysine 9 trimethyl chromatin modifications. Analyses suggested that SUMO is associated with these repressive marks in highly tissue-specific genes (Neyret-Kahn et al., 2013), suggesting that, in these cases, SUMO likely functions by keeping a repressed state that is then lifted in certain tissues and/or in response to certain stimuli. This is also true for SUMOylation at histone, protein biogenesis, Pol I ribosomal RNA, and Pol III transfer RNA genes, where it seems to restrain their expression, consistent with the idea that SUMOylation suppresses excessive gene transcription and protein synthesis. In agreement with this notion, SUMOylation-deficient cells exhibit increased cell size and enhanced global protein synthesis (Neyret-Kahn et al., 2013). Protein SUMOylation is thus considered a major factor in fine-tuning transcription, and as represented in Figure 2 and explained below, this involves orchestration with chromatin modification, proposing SUMO as a regulator that mediates the dialog between transcriptional regulators and chromatin-modifying proteins (Fig. 2). Although this level of mechanistic details of how SUMO may regulate transcription is not available in plants, the conservation of SUMO functions at the molecular and cellular levels throughout eukaryotes suggests that these mechanisms may also regulate plant gene expression.

SUMO is also implicated in chromatin biology. Identification of SUMO targets and SIPs in several model systems including Arabidopsis reveals their enrichment in chromatin modification proteins (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Elrouby et al., 2013; Hendriks et al., 2014). SUMOylation of histones, histone deactylases (HDACs), components of histone acetyltransferases, and DNA methyltransferases has been reported (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; for review, see Cubeñas-Potts and Matunis, 2013). SUMOylation of the mammalian maintenance DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1, for example, increases its activity in vitro, and SUMOylation of the de novo DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b has been shown to occur in vivo (Li et al., 2007; Lee and Muller, 2009). SUMOylation may also be required for DNA demethylation, because mice knockout mutants of the mammalian STUbL RNF4 are embryo lethal; however, embryonic fibroblasts exhibit hypermethylation, possibly due to perturbation of RNF4’s interaction with TDG (Hu et al., 2010). On the other hand, all different forms of histones are SUMOylated, including H2A.Z, and together with methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination, SUMOylation has been proposed to contribute to the histone code and to act as a signal to recruit chromatin-associated proteins (Shiio and Eisenman, 2003; Nathan et al., 2006; Neyret-Kahn et al., 2013). Consistent with this, Arabidopsis SET [for Su(var)3–9, E(z), and Trithorax] domain histone methyltransferases, Jumonji-type histone demethylases, and DNA methyltransferases and demethylases were found to interact with SUMO noncovalently and are probably recruited to SUMOylated histones, by virtue of this interaction, to affect their functions in chromatin modification (Elrouby et al., 2013). There is also good evidence that SUMOylation of HDACs promotes HDAC effects in transcriptional repression (for review, see Cubeñas-Potts and Matunis, 2013). Some components of histone acetyltransferase (e.g. Transcriptional Adaptor 2b [ADA2B]) are also SUMOylated, as has been shown in Arabidopsis and yeast (Wohlschlegel et al., 2004; Elrouby and Coupland, 2010). Additionally, SUMO plays important roles in the nucleolus, telomeres, and centromeres (Cubeñas-Potts and Matunis, 2013).

SUMO TARGETS HOLD THE KEY TO DISSECTING THE ROLES OF SUMO IN EUKARYOTIC GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Despite strong evidence for the crucial roles of SUMO during eukaryotic development, approximately two decades after its discovery and about 3,000 research articles later, we still know very little about how SUMO regulates cellular and organismal activities. This is particularly true for plants, although we know that SUMO and SUMOylation are essential for plant growth and development. As described above, in Arabidopsis, inactivation of the basic SUMO conjugation machinery, the SAE (E1) or the SCE (E2), or double knockouts of SUMO1 and SUMO2 cause embryo stage arrest of development (Saracco et al., 2007). Additionally, impairing the functions of the SUMO ligases (E3) SIZ1 or MMS21 or the SUMO protease ESD4 causes major pleiotropic developmental defects (Reeves et al., 2002; Catala et al., 2007; Saracco et al., 2007; Ishida et al., 2012). These studies revealed the essential nature of protein SUMOylation but taught us very little about how SUMO regulates plant growth and development. As described in the following sections, the functional categories of known Arabidopsis SUMO targets were evaluated, and together with the pleiotropic phenotypes caused by perturbation of cellular SUMO homeostasis, the findings emphasize that identifying targets is key to studying the mechanisms by which SUMO regulates plant growth and development. The successful use of a number of methodologies and approaches to efficiently identify target proteins and their SUMOylation sites in other model systems (mostly human cell lines) is also examined in the following sections, and the relevance of these in identifying plant SUMO targets and deciphering the roles of SUMO in plant development are discussed.

The survival and pleiotropic defects exhibited by mutants of the SUMO conjugation and deconjugation systems are likely caused by loss, and/or disturbing the equilibrium, of target SUMOylation. This implicates SUMO targets and their SUMOylation as important regulators of development. Consequently, enormous efforts have been made to identify targets in different model organisms, including plants. Additionally, it is important to determine the exact site where SUMO is attached to these proteins (SUMO attachment site [SAS]). This will help future mutagenesis studies assessing the role of SUMOylation, at these sites, in the function of target proteins. Unlike ubiquitin, where a consensus sequence around its attachment Lys has not been determined, the SAS usually conforms to the motif ΨKxE/D (Ψ is a large hydrophobic residue, K is the Lys residue where SUMO is covalently attached, x is any amino acid, and E/D are the acidic amino acids Glu and Asp; Bernier-Villamor et al., 2002). Variations of this motif and other flanking-sequence requirements have been described, however, necessitating the exact identification of SUMO attachment lysines (Hendriks et al., 2014). Despite several efforts to identify plant SUMO targets and their SASs, we are still far from a scenario that would allow us to fully utilize the resources plants have to understand the role of SUMO in eukaryotic development. For example, whereas most biochemical and molecular studies were performed in vitro or in single cells (yeast and mammalian cell lines), plants have the advantage and potential of leading studies aiming to characterize the role of SUMO at the cell, tissue, organ, and whole-plant levels. The embryonic arrest and enormous pleiotropic defects observed in mutants of the SUMO conjugation and deconjugation enzymes reflect this potential, and preliminary studies implicating SUMO in the floral transition, root development, and response to physiological and environmental conditions suggest that current knowledge is at a nascent stage. Analysis of the functional categories of SUMO targets across different eukaryotic groups revealed considerable conservation of SUMO functions at the molecular and cellular levels, suggesting that we are likely to benefit from what we learn in one system to infer on SUMO functions in other eukaryotic groups. Given the vast array of molecular processes in which SUMO is implicated, the role of SUMO in normal growth and development is best dissected by studying target SUMOylation.

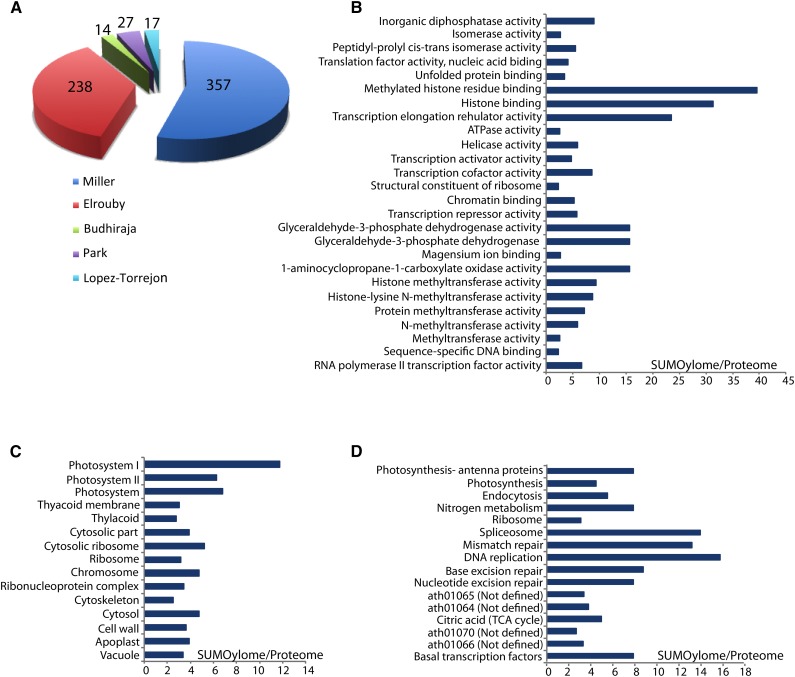

Several laboratories have systematically identified SUMO targets in the model plant Arabidopsis (Budhiraja et al., 2009; Elrouby and Coupland, 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011; López-Torrejón et al., 2013). These efforts led to the identification of 653 proteins (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Data Set S1). Using affinity purification under denaturing conditions (His6-SUMO1) coupled with a second round of purification with anti-SUMO antibody (Miller et al., 2010) or antibodies against a second tag (Budhiraja et al., 2009; Park et al., 2011) or using two-dimensional liquid chromatography coupled with immunodetection (López-Torrejón et al., 2013), 415 proteins were identified and analyzed by mass spectrometry. On the other hand, a yeast two-hybrid library screening approach identified 238 proteins that interacted with the SCE (E2) and/or the main SUMO protease ESD4 (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010). The latter approach took advantage of the fact that the SUMO E2 and the SUMO protease ESD4 must interact noncovalently with their targets to allow target conjugation and deconjugation. A disadvantage of this approach is that the identified proteins had to be tested in vitro to assess whether they are SUMO targets, and 92% of these proteins were shown to be modified by either SUMO1, SUMO3, or both (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010). An advantage of this approach is that proteins that are SUMOylated at low levels and/or whose SUMO moiety is easily cleaved upon preparation from plant tissues might have been isolated. Additionally, proteins that may interact with the SUMO E2 or ESD4 to regulate their activities or that are part of the SUMO conjugation/deconjugation machinery would be identified. Several such proteins were identified, including the recently characterized SUMO E4 ligases PIAL1 and PIAL2 (Tomanov et al., 2014) as well as a unique variant of SUMO that has not been characterized (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010).

Figure 3.

Characterization of SUMO targets in Arabidopsis. A, Identification of 653 SUMO targets by proteomic (Budhiraja et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011; López-Torrejón et al., 2013) and yeast two-hybrid (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010) approaches. Numbers indicate the number of targets identified by each approach. B to D, Gene Ontology analyses of Arabidopsis SUMO targets. Proteins shown in A were used to identify molecular (B), cellular component (C), and KEGG term (D) categories in which SUMO targets (SUMOylome) are enriched compared with the whole proteome. Only terms with statistically significant differences are presented and shown as the ratio of representation in the SUMOylome to that of the whole proteome. SUMO targets collected from the five main studies were compared for overlap, pooled, and then used in term enrichments. For this purpose, FatiGo (Al-Shahrour et al., 2007) was used as part of the Babelomics suit of programs (http://v4.babelomics.org). TCA, Tricarboxylic acid.

Assessing the Gene Ontology of the relatively small number of Arabidopsis SUMO targets identified so far (compared with that identified in human cells) implicates SUMO in an array of biological and molecular activities. Many of the functional categories revealed at the molecular level were also identified when human SUMO targets were similarly assessed (Hendriks et al., 2014), reflecting the conservation of these functions throughout eukaryotes. For example, the so-called SUMOylome of both plants and human cells is enriched in DNA-, RNA-, and chromatin-binding proteins, including transcription activator and repressor complexes and histone and DNA modification proteins (particularly methylation) as well as proteins with helicase activity (Fig. 3B). Assessment of the Arabidopsis SUMOylome in terms of the biological processes it participates in reveals a larger range of activities that include plant hormone (auxin, brassinosteroids, and abscisic acid) transport and signaling, organ development (flower, root, meristem, seed, fruit, and embryo), and seed dormancy as well as response to an array of environmental conditions such as growth conditions (carbohydrate stimulus), radiation, light, temperature and heat, cold and freezing, osmotic stress, water deprivation, and response to biotic stress (pathogen attack; Supplemental Fig. S1). Most of these activities are mediated by nuclear proteins; however, they affect a number of other cellular compartments such as the cell wall, chloroplast, cytosol, and the cytoskeleton (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, when the Arabidopsis SUMOylome was assessed for enrichment in specific pathways (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG] terms; Fig. 3D), a few enrichment terms were identified that are consistent with the molecular functions identified here and with activities revealed from studying the role of SUMO in the function of specific proteins. These include base excision and mismatch repair, DNA replication, basal transcription, and RNA splicing (spliceosome). Additional pathways are revealed by this analysis and include photosynthesis, endocytosis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle, nitrogen metabolism, and four unidentified terms (Fig. 3D). KEGG mapping (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg1b.html) uses several primary (genes, proteins, small molecules, etc.) and secondary (functional hierarchies, interaction information, etc.) data sets to build pathway models. The results shown in Figure 3D suggest that several SUMO targets are implicated in specific pathways, e.g. excision repair, tricarboxylic acid cycle, etc. This identifies what has been previously described in yeast as group SUMOylation (Psakhye and Jentsch, 2012), where several proteins implicated in one pathway are regulated by SUMOylation. Group SUMOylation presents a challenge to studying the role of SUMO in the function of individual proteins because the effects of SUMOylation on the overall phenotype catalyzed by the pathway are often distributed across the different protein components of the pathway. For example, this is the case in DNA double-strand break repair, where DNA damage causes simultaneous SUMOylation of several proteins of the repair pathway, and only upon elimination of SUMOylation of multiple proteins could slowing down of DNA repair be observed (Psakhye and Jentsch, 2012). Several repair pathways were identified by our analysis (Fig. 3D), consistent with these findings. The identification of pathways in which SUMO plays major roles suggests that group SUMOylation may likely also regulate plant growth and development and is a prerequisite to study the mechanism of how this regulation is conducted.

Although the Arabidopsis proteins identified by these studies are a good resource to start assessing how SUMO modification may regulate plant development, these screens were by no means saturated, and a lot more SUMO targets ought to be identified. The proteins identified by these screens do not overlap, consistent with the proposal that thousands of proteins might be SUMOylated and with the fact that the conditions and methodologies used by the different groups varied considerably. Importantly, with the exception of only 17 SASs identified by Miller et al. (2010; several of these are on SUMO itself), these studies failed to identify SUMO attachment lysines. Recent technological advances using mammalian cells (discussed below) allowed a deeper identification and characterization of thousands of SUMO targets and their attachment lysines and hence present potential to follow suit in plants.

RECENT ADVANCES IN TARGET AND SAS IDENTIFICATION: LESSONS FROM HUMANS

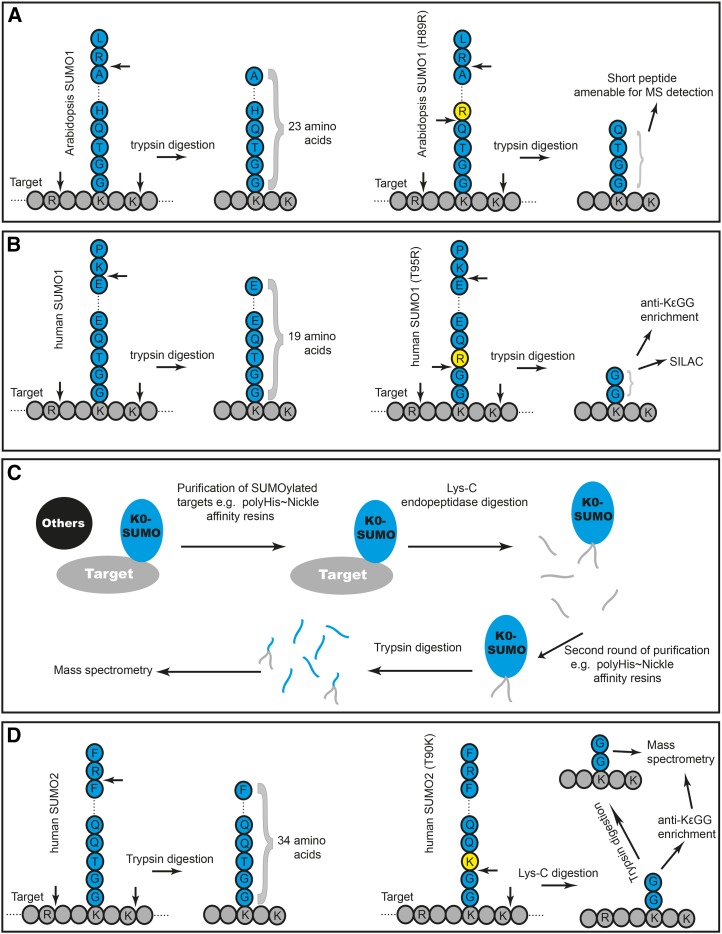

Several hundred SUMO target proteins were identified in yeast (Panse et al., 2004; Wohlschlegel et al., 2004; Hannich et al., 2005; Wykoff and O’Shea, 2005), whereas in human cells, this number approaches 2,700 proteins (Golebiowski et al., 2009; Matic et al., 2010; Bruderer et al., 2011; Becker et al., 2013; Hendriks et al., 2014; Schimmel et al., 2014; Tammsalu et al., 2014). Recent efforts also identified more than 4,000 SASs in targets purified from HeLa cells (Hendriks et al., 2014). These studies utilized clever experimental design that may prove to be useful in identifying plant SUMO targets and their SASs more efficiently and precisely. For example, Becker et al. (2013) used epitope-specific monoclonal antibodies to identify SUMO paralog-specific targets, and hence they could identify proteins modified by human SUMO1 and those modified by human SUMO2/SUMO3. To inactivate SUMO proteases that would ordinarily cleave SUMO off target proteins during purifications performed under native conditions, several groups used a SUMO version tagged with a His tract (His6), which is compatible with purification under denaturing conditions (Budhiraja et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2010; Park et al., 2011; Hendriks et al., 2014; Impens et al., 2014). This may be followed by another enrichment step using anti-SUMO antibodies or antibodies against another tag. To avoid the use of another tag, Hendriks et al. (2014) used a deca-His tag (His10), which enabled single-round purification with high yield and purity. When combined with tricks aimed at shortening the SUMO peptide footprint resulting after Trypsin digestion, these approaches may also have the potential to identify the SAS using mass spectrometry. For example, converting His-89 of Arabidopsis SUMO1 or Gln-87 of human SUMO2 into Arg allowed the shortening of the SUMO footprint considerably, permitting its easy detection by mass spectrometry while being distinct from footprints generated by ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-like proteins Neural Precursor Cell Expressed, Developmentally Down-Regulated8 (Nedd8) and Interferon-Stimulated Gene of 15 kD (ISG15; Fig. 4A; Miller et al., 2010; Schimmel et al., 2014). To enhance identification of SASs, Impens et al. (2014) converted Thr-95 of human SUMO1 into Arg. After Trypsin digestion, this would generate a target protein fragment linked by an isopeptide bond with the C-terminal di-Gly tail of SUMO (Fig. 4B). These lariat structures can then be enriched using anti-di-Gly antibodies (anti-KεGG antibody; Fig. 4B), which had previously been used successfully to identify ubiquitin attachment lysines (Xu et al., 2010). These structures are indistinguishable from footprints generated by ubiquitin, Nedd8, and ISG15; however, Impens et al. (2014) used stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture to compare peptides derived from different protein modifiers (Fig. 4B). This approach allowed the identification of 295 human SUMO1 sites (in 227 targets) and 167 SUMO2 sites (in 135 targets).

Figure 4.

Recent technological advances to identify SUMO targets and SUMO attachment lysines, mostly from human cells, provide a blueprint that could be used to identify SUMO targets in plants. A, Strategy to reduce the size of SUMO footprint produced by Trypsin digestion as a prerequisite to identifying SUMO targets and attachment lysines by mass spectrometry (MS). Introducing an Arg residue (yellow) a couple of residues upstream of the C-terminal di-Gly of SUMO (in blue) allows shortening of the SUMO footprint while being distinct from footprints produced by ubiquitin and other ubiquitin-like modifiers. B, The Arg could be introduced immediately upstream of SUMO’s di-Gly, and purified proteins labeled with different stable isotopes to distinguish between the different protein modifiers (using the stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture [SILAC] method) are then enriched using anti-di-Gly monoclonal antibody (anti-KεGG). C, Using a mutant form of SUMO (K0-SUMO) in which all lysines are converted to a different amino acid allows the use of Lys-C endopeptidase, which cleaves purified SUMO targets at Lys residues. Intact SUMO attached to a short target peptide is subsequently trypsinized, allowing precise detection of target protein identity and SASs by mass spectrometry. D, A Lys residue can also be introduced immediately upstream of SUMO’s di-Gly, and purified SUMO targets are first treated with Lys-C, prior to their enrichment with anti-KεGG antibody and mass spectrometric characterization.

Another strategy that proved to be very efficient in identifying a large number of SASs in SUMOylated proteins purified from HeLa cells was to employ the so-called K0-SUMO variant (Fig. 4C; Hendriks et al., 2014). When all Lys residues in SUMO are mutated to create a Lys-less SUMO variant (K0-SUMO), this form of SUMO can be conjugated to target proteins but may not form polySUMO chains. Subsequently, SUMOylated target proteins (purified using any of the approaches described above) are treated with the Lys-C endopeptidase that cleaves proteins at Lys residues. This will degrade most proteins, leaving intact SUMO still attached to the target Lys (protected from Lys-C by the isopeptide bond formed with SUMO). A following purification step of this peptide mixture will enrich only for peptides modified by SUMO, which can be determined by mass spectrometry following Trypsin treatment as usual. Sandwiched by two purification rounds under denaturing conditions (Fig. 4C), Hendriks et al. (2014) treated K0-SUMO conjugates with Lys-C, an approach that allowed the identification of 1,606 unique SUMO targets and 4,361 SUMO attachment lysines. A hybrid approach that combined the use of Lys-C endopeptidase and the generation of a short lariat SUMO footprint in one trick was used by Tammsalu et al. (2014), where Thr-90, located immediately upstream of the C-terminal di-Gly of human His-6-SUMO2, was converted into Lys (Fig. 4D). Following denaturing purification on nickel affinity resin, digestion with Lys-C resulted in short di-Gly lariat peptides, which were further enriched with anti-KεGG antibody. This approach revealed more than 1,000 SUMOylated lysines in 539 protein targets.

PLANTS AS MODELS FOR EUKARYOTES TO STUDY THE ROLES OF SUMO DURING DEVELOPMENT

Plants provide an excellent system to study the functions of protein SUMOylation. In addition to being multicellular higher eukaryotes where the functions of SUMO may be dissected at multiple developmental levels, mutants of the SUMO pathway could be used to identify specific subsets of target proteins that are modified by a specific enzyme. For example, introducing the technologies described above into the siz1, mms21, or esd4 mutant backgrounds will allow the identification of targets specifically modified by these proteins and will hence help correlate some of the phenotypes associated with mutants of these genes with specific proteins. The identification of proteins that interact with ESD4 in the yeast two-hybrid assay was a first attempt to identify these SUMO protein subsets (Elrouby and Coupland, 2010); however, a more thorough proteomic approach will be much more informative. Conditional alleles of the SAE or SCE may also be employed to dissect the functions of these genes. For example, the embryo-lethal phenotype associated with mutations of these genes may be rescued using transgenes harboring point mutations that permit viability or transgenes that allow their expression from inducible promoters, allowing SUMOylation only under controlled experimental settings. Additionally, whole-organism phenotypes associated with alterations of the SUMOylation state of specific target proteins may be achieved in plants, an advantage that unicellular organisms and cell lines cannot support. Plants provide a very tractable system to study the role of SUMO in cellular and organismal development that is likely to shed broader insight into the importance of this dynamic and targeted modification in various processes in eukaryotes and perhaps identify relevance to agriculture and ecosystems.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Gene Ontology analysis (biological process) of plant SUMO targets.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Analysis of Arabidopsis SUMO targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank Renee Petipas for critical reading of this article and Sorina Popescu for resources.

Glossary

- TDG

thymine DNA glycosylase

- SIM

small ubiquitin-like modifier interaction motif

- SIP

small ubiquitin-like modifier-interacting protein

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- HDAC

histone deactylase

- SAS

small ubiquitin-like modifier attachment site

References

- Al-Shahrour F, Minguez P, Tárraga J, Medina I, Alloza E, Montaner D, Dopazo J (2007) FatiGO +: a functional profiling tool for genomic data. Integration of functional annotation, regulatory motifs and interaction data with microarray experiments. Nucleic Acids Res 35: W91–W96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba D, Maita N, Jee JG, Uchimura Y, Saitoh H, Sugasawa K, Hanaoka F, Tochio H, Hiroaki H, Shirakawa M (2005) Crystal structure of thymine DNA glycosylase conjugated to SUMO-1. Nature 435: 979–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J, Barysch SV, Karaca S, Dittner C, Hsiao HH, Berriel Diaz M, Herzig S, Urlaub H, Melchior F (2013) Detecting endogenous SUMO targets in mammalian cells and tissues. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 525–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier-Villamor V, Sampson DA, Matunis MJ, Lima CD (2002) Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell 108: 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruderer R, Tatham MH, Plechanovova A, Matic I, Garg AK, Hay RT (2011) Purification and identification of endogenous polySUMO conjugates. EMBO Rep 12: 142–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budhiraja R, Hermkes R, Müller S, Schmidt J, Colby T, Panigrahi K, Coupland G, Bachmair A (2009) Substrates related to chromatin and to RNA-dependent processes are modified by Arabidopsis SUMO isoforms that differ in a conserved residue with influence on desumoylation. Plant Physiol 149: 1529–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Miquel L, Seguí J, Manrique S, Teixeira I, Carretero-Paulet L, Atencio F, Lois LM (2013) Diversification of SUMO-activating enzyme in Arabidopsis: implications in SUMO conjugation. Mol Plant 6: 1646–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catala R, Ouyang J, Abreu IA, Hu Y, Seo H, Zhang X, Chua NH (2007) The Arabidopsis E3 SUMO ligase SIZ1 regulates plant growth and drought responses. Plant Cell 19: 2952–2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chupreta S, Holmstrom S, Subramanian L, Iñiguez-Lluhí JA (2005) A small conserved surface in SUMO is the critical structural determinant of its transcriptional inhibitory properties. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4272–4282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti L, Price G, O’Donnell E, Schwessinger B, Dominy P, Sadanandom A (2008) Small ubiquitin-like modifier proteases OVERLY TOLERANT TO SALT1 and -2 regulate salt stress responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 2894–2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubeñas-Potts C, Matunis MJ (2013) SUMO: a multifaceted modifier of chromatin structure and function. Dev Cell 24: 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen RJ. (2004) SUMO protein modification. Biochim Biophys Acta 1695: 113–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrouby N. (2014) Extent and significance of non-covalent SUMO interactions in plant development. Plant Signal Behav 9: e27948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrouby N, Bonequi MV, Porri A, Coupland G (2013) Identification of Arabidopsis SUMO-interacting proteins that regulate chromatin activity and developmental transitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 19956–19961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrouby N, Coupland G (2010) Proteome-wide screens for small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) substrates identify Arabidopsis proteins implicated in diverse biological processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 17415–17420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz A, Ackermann L, Hoppe T (2014) Create and preserve: Proteostasis in development and aging is governed by Cdc48/p97/VCP. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843: 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Ahmed K, Ding H, Ding X, Lan J, Yang Z, Miao Y, Zhu Y, Shi Y, Zhu J, et al. (2005) Stabilization of PML nuclear localization by conjugation and oligomerization of SUMO-3. Oncogene 24: 5401–5413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss-Friedlander R, Melchior F (2007) Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiowski F, Matic I, Tatham MH, Cole C, Yin Y, Nakamura A, Cox J, Barton GJ, Mann M, Hay RT (2009) System-wide changes to SUMO modifications in response to heat shock. Sci Signal 2: ra24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Bové X, Sebé-Pedrós A, Ruiz-Trillo I (2015) The eukaryotic ancestor had a complex ubiquitin signaling system of archaeal origin. Mol Biol Evol 32: 726–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Giasson BI, Glavis-Bloom A, Brewer MD, Shorter J, Gitler AD, Yang X (2014) A cellular system that degrades misfolded proteins and protects against neurodegeneration. Mol Cell 55: 15–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannich JT, Lewis A, Kroetz MB, Li SJ, Heide H, Emili A, Hochstrasser M (2005) Defining the SUMO-modified proteome by multiple approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 280: 4102–4110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeland U, Steinacher R, Jiricny J, Schär P (2002) Modification of the human thymine-DNA glycosylase by ubiquitin-like proteins facilitates enzymatic turnover. EMBO J 21: 1456–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks IA, D’Souza RCJ, Yang B, Verlaan-de Vries M, Mann M, Vertegaal ACO (2014) Uncovering global SUMOylation signaling networks in a site-specific manner. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 927–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermkes R, Fu YF, Nürrenberg K, Budhiraja R, Schmelzer E, Elrouby N, Dohmen RJ, Bachmair A, Coupland G (2011) Distinct roles for Arabidopsis SUMO protease ESD4 and its closest homolog ELS1. Planta 233: 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M. (2009) Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature 458: 422–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoen DR, Park KC, Elrouby N, Yu Z, Mohabir N, Cowan RK, Bureau TE (2006) Transposon-mediated expansion and diversification of a family of ULP-like genes. Mol Biol Evol 23: 1254–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XV, Rodrigues TM, Tao H, Baker RK, Miraglia L, Orth AP, Lyons GE, Schultz PG, Wu X (2010) Identification of RING finger protein 4 (RNF4) as a modulator of DNA demethylation through a functional genomics screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 15087–15092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yang S, Zhang S, Liu M, Lai J, Qi Y, Shi S, Wang J, Wang Y, Xie Q, et al. (2009) The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase AtMMS21, a homologue of NSE2/MMS21, regulates cell proliferation in the root. Plant J 60: 666–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impens F, Radoshevich L, Cossart P, Ribet D (2014) Mapping of SUMO sites and analysis of SUMOylation changes induced by external stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 12432–12437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Yoshimura M, Miura K, Sugimoto K (2012) MMS21/HPY2 and SIZ1, two Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligases, have distinct functions in development. PLoS One 7: e46897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Durocher D (2013) Regulation of DNA damage responses by ubiquitin and SUMO. Mol Cell 49: 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES. (2004) Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 355–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Muller MT (2009) SUMOylation enhances DNA methyltransferase 1 activity. Biochem J 421: 449–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Zhou J, Liu P, Hu J, Jin H, Shimono Y, Takahashi M, Xu G (2007) Polycomb protein Cbx4 promotes SUMO modification of de novo DNA methyltransferase Dnmt3a. Biochem J 405: 369–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois LM, Lima CD, Chua NH (2003) Small ubiquitin-like modifier modulates abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15: 1347–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Torrejón G, Guerra D, Catalá R, Salinas J, del Pozo JC (2013) Identification of SUMO targets by a novel proteomic approach in plants(F). J Integr Plant Biol 55: 96–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic I, Schimmel J, Hendriks IA, van Santen MA, van de Rijke F, van Dam H, Gnad F, Mann M, Vertegaal ACO (2010) Site-specific identification of SUMO-2 targets in cells reveals an inverted SUMOylation motif and a hydrophobic cluster SUMOylation motif. Mol Cell 39: 641–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Barrett-Wilt GA, Hua Z, Vierstra RD (2010) Proteomic analyses identify a diverse array of nuclear processes affected by small ubiquitin-like modifier conjugation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 16512–16517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MJ, Scalf M, Rytz TC, Hubler SL, Smith LM, Vierstra RD (2013) Quantitative proteomics reveals factors regulating RNA biology as dynamic targets of stress-induced SUMOylation in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell Proteomics 12: 449–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Lee J, Jin JB, Yoo CY, Miura T, Hasegawa PM (2009) Sumoylation of ABI5 by the Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 negatively regulates abscisic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5418–5423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Rus A, Sharkhuu A, Yokoi S, Karthikeyan AS, Raghothama KG, Baek D, Koo YD, Jin JB, Bressan RA, et al. (2005) The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 controls phosphate deficiency responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7760–7765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtas G, Reeves PH, Fu YF, Bancroft I, Dean C, Coupland G (2003) A nuclear protease required for flowering-time regulation in Arabidopsis reduces the abundance of SMALL UBIQUITIN-RELATED MODIFIER conjugates. Plant Cell 15: 2308–2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan D, Ingvarsdottir K, Sterner DE, Bylebyl GR, Dokmanovic M, Dorsey JA, Whelan KA, Krsmanovic M, Lane WS, Meluh PB, et al. (2006) Histone sumoylation is a negative regulator in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and shows dynamic interplay with positive-acting histone modifications. Genes Dev 20: 966–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyret-Kahn H, Benhamed M, Ye T, Le Gras S, Cossec JC, Lapaquette P, Bischof O, Ouspenskaia M, Dasso M, Seeler J, et al. (2013) Sumoylation at chromatin governs coordinated repression of a transcriptional program essential for cell growth and proliferation. Genome Res 23: 1563–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novatchkova M, Budhiraja R, Coupland G, Eisenhaber F, Bachmair A (2004) SUMO conjugation in plants. Planta 220: 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novatchkova M, Tomanov K, Hofmann K, Stuible HP, Bachmair A (2012) Update on sumoylation: defining core components of the plant SUMO conjugation system by phylogenetic comparison. New Phytol 195: 23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang J, Shi Y, Valin A, Xuan Y, Gill G (2009) Direct binding of CoREST1 to SUMO-2/3 contributes to gene-specific repression by the LSD1/CoREST1/HDAC complex. Mol Cell 34: 145–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panse VG, Hardeland U, Werner T, Kuster B, Hurt E (2004) A proteome-wide approach identifies sumoylated substrate proteins in yeast. J Biol Chem 279: 41346–41351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HC, Choi W, Park HJ, Cheong MS, Koo YD, Shin G, Chung WS, Kim WY, Kim MG, Bressan RA, et al. (2011) Identification and molecular properties of SUMO-binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Mol Cells 32: 143–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelisch F, Sonneville R, Pourkarimi E, Agostinho A, Blow JJ, Gartner A, Hay RT (2014) Dynamic SUMO modification regulates mitotic chromosome assembly and cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun 5: 5485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plechanovová A, Jaffray EG, Tatham MH, Naismith JH, Hay RT (2012) Structure of a RING E3 ligase and ubiquitin-loaded E2 primed for catalysis. Nature 489: 115–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psakhye I, Jentsch S (2012) Protein group modification and synergy in the SUMO pathway as exemplified in DNA repair. Cell 151: 807–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PH, Murtas G, Dash S, Coupland G (2002) early in short days 4, a mutation in Arabidopsis that causes early flowering and reduces the mRNA abundance of the floral repressor FLC. Development 129: 5349–5361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosonina E, Duncan SM, Manley JL (2010) SUMO functions in constitutive transcription and during activation of inducible genes in yeast. Genes Dev 24: 1242–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Best JL, Zon LI, Gill G (2002) SUMO-1 modification represses Sp3 transcriptional activation and modulates its subnuclear localization. Mol Cell 10: 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saracco SA, Miller MJ, Kurepa J, Vierstra RD (2007) Genetic analysis of SUMOylation in Arabidopsis: conjugation of SUMO1 and SUMO2 to nuclear proteins is essential. Plant Physiol 145: 119–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savare J, Bonneaud N, Girard F (2005) SUMO represses transcriptional activity of the Drosophila SoxNeuro and human Sox3 central nervous system-specific transcription factors. Mol Biol Cell 16: 2660–2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel J, Eifler K, Sigurðsson JO, Cuijpers SAG, Hendriks IA, Verlaan-de Vries M, Kelstrup CD, Francavilla C, Medema RH, Olsen JV, et al. (2014) Uncovering SUMOylation dynamics during cell-cycle progression reveals FoxM1 as a key mitotic SUMO target protein. Mol Cell 53: 1053–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer N, Ferrás C, Kern DM, Logarinho E, Cheeseman IM, Maiato H (2013) Spindle assembly checkpoint robustness requires Tpr-mediated regulation of Mad1/Mad2 proteostasis. J Cell Biol 203: 883–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen TH, Lin HK, Scaglioni PP, Yung TM, Pandolfi PP (2006) The mechanisms of PML-nuclear body formation. Mol Cell 24: 331–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiio Y, Eisenman RN (2003) Histone sumoylation is associated with transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13225–13230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EJ, Shin HM, Nam E, Kim WS, Kim JH, Oh BH, Yun Y (2012) DeSUMOylating isopeptidase: a second class of SUMO protease. EMBO Rep 13: 339–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spektor TM, Congdon LM, Veerappan CS, Rice JC (2011) The UBC9 E2 SUMO conjugating enzyme binds the PR-Set7 histone methyltransferase to facilitate target gene repression. PLoS One 6: e22785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Hatakeyama S, Saitoh H, Nakayama KI (2005) Noncovalent SUMO-1 binding activity of thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) is required for its SUMO-1 modification and colocalization with the promyelocytic leukemia protein. J Biol Chem 280: 5611–5621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammsalu T, Matic I, Jaffray EG, Ibrahim AFM, Tatham MH, Hay RT (2014) Proteome-wide identification of SUMO2 modification sites. Sci Signal 7: rs2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT (2008) RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat Cell Biol 10: 538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomanov K, Zeschmann A, Hermkes R, Eifler K, Ziba I, Grieco M, Novatchkova M, Hofmann K, Hesse H, Bachmair A (2014) Arabidopsis PIAL1 and 2 promote SUMO chain formation as E4-type SUMO ligases and are involved in stress responses and sulfur metabolism. Plant Cell 26: 4547–4560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzunova K, Göttsche K, Miteva M, Weisshaar SR, Glanemann C, Schnellhardt M, Niessen M, Scheel H, Hofmann K, Johnson ES, et al. (2007) Ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic control of SUMO conjugates. J Biol Chem 282: 34167–34175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Burg HA, Kini RK, Schuurink RC, Takken FLW (2010) Arabidopsis small ubiquitin-like modifier paralogs have distinct functions in development and defense. Plant Cell 22: 1998–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierstra RD. (2012) The expanding universe of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers. Plant Physiol 160: 2–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villajuana-Bonequi M, Elrouby N, Nordström K, Griebel T, Bachmair A, Coupland G (2014) Elevated salicylic acid levels conferred by increased expression of ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE 1 contribute to hyperaccumulation of SUMO1 conjugates in the Arabidopsis mutant early in short days 4. Plant J 79: 206–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR III (2004) Global analysis of protein sumoylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 279: 45662–45668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykoff DD, O’Shea EK (2005) Identification of sumoylated proteins by systematic immunoprecipitation of the budding yeast proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics 4: 73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Kerscher O, Kroetz MB, McConchie HF, Sung P, Hochstrasser M (2007) The yeast Hex3.Slx8 heterodimer is a ubiquitin ligase stimulated by substrate sumoylation. J Biol Chem 282: 34176–34184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Paige JS, Jaffrey SR (2010) Global analysis of lysine ubiquitination by ubiquitin remnant immunoaffinity profiling. Nat Biotechnol 28: 868–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Yuan D, Liu M, Li C, Liu Y, Zhang S, Yao N, Yang C (2013) AtMMS21, an SMC5/6 complex subunit, is involved in stem cell niche maintenance and DNA damage responses in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol 161: 1755–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Plechanovová A, Simpson P, Marchant J, Leidecker O, Kraatz S, Hay RT, Matthews SJ (2014) Structural insight into SUMO chain recognition and manipulation by the ubiquitin ligase RNF4. Nat Commun 5: 4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunus AA, Lima CD (2009) Structure of the Siz/PIAS SUMO E3 ligase Siz1 and determinants required for SUMO modification of PCNA. Mol Cell 35: 669–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.