The lack of lipid phosphatidylglycerol inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis and induces accumulation of an aberrant protein complex containing monomeric PSI and CP43 antenna of PSII.

Abstract

The negatively charged lipid phosphatidylglycerol (PG) constitutes up to 10% of total lipids in photosynthetic membranes, and its deprivation in cyanobacteria is accompanied by chlorophyll (Chl) depletion. Indeed, radioactive labeling of the PG-depleted ΔpgsA mutant of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, which is not able to synthesize PG, proved the inhibition of Chl biosynthesis caused by restriction on the formation of 5-aminolevulinic acid and protochlorophyllide. Although the mutant accumulated chlorophyllide, the last Chl precursor, we showed that it originated from dephytylation of existing Chl and not from the block in the Chl biosynthesis. The lack of de novo-produced Chl under PG depletion was accompanied by a significantly weakened biosynthesis of both monomeric and trimeric photosystem I (PSI) complexes, although the decrease in cellular content was manifested only for the trimeric form. However, our analysis of ΔpgsA mutant, which lacked trimeric PSI because of the absence of the PsaL subunit, suggested that the virtual stability of monomeric PSI is a result of disintegration of PSI trimers. Interestingly, the loss of trimeric PSI was accompanied by accumulation of monomeric PSI associated with the newly synthesized CP43 subunit of photosystem II. We conclude that the absence of PG results in the inhibition of Chl biosynthetic pathway, which impairs synthesis of PSI, despite the accumulation of chlorophyllide released from the degraded Chl proteins. Based on the knowledge about the role of PG in prokaryotes, we hypothesize that the synthesis of Chl and PSI complexes are colocated in a membrane microdomain requiring PG for integrity.

Photosynthetic membrane of oxygenic phototrophs has a unique lipid composition that has been conserved during billions of years of evolution from cyanobacteria and algae to modern higher plants. With no known exception, this membrane system always contains the uncharged glycolipids monogalactosyldiacylglycerol and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) as well as the negatively charged lipids sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (SQDG) and phosphatidylglycerol (PG; Murata and Siegenthaler, 1998). Interestingly, it seems that PG is the only lipid completely essential for the oxygenic photosynthesis. The loss of DGDG has only a mild impact on the cyanobacterial cell (Awai et al., 2007), and as shown recently in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, both galactolipids can be in fact replaced by glucolipids (Awai et al., 2014). SQDG and PG are only minor lipid components, each accounting for 5% to 12% of total lipids (Murata and Siegenthaler, 1998). SQDG is dispensable, although its lack results in various defects (Yu et al., 2002; Aoki et al., 2004), but PG plays an essential role in both cyanobacterial cells and plant chloroplasts (Hagio et al., 2000; Babiychuk et al., 2003).

The critical role of PG has been mostly connected to the function of PSII. In both cyanobacteria and plants, lack of PG impairs the stability of PSII complexes and the electron transport between primary and secondary quinone acceptors inside the PSII reaction center. As shown in Synechocystis sp., PG molecules stabilize PSII dimers and facilitate the binding of inner antenna protein CP43 within the PSII core (Laczkó-Dobos et al., 2008). Indeed, according to the PSII crystal structure, two PG molecules are located at the interface between CP43 and the D1-D2 heterodimer (Guskov et al., 2009). As a consequence, the PG depletion inhibits and destabilizes PSII complexes and also, impairs assembly of new PSII complexes, although all PSII subunits are still synthesized in the cell (Laczkó-Dobos et al., 2008).

Despite the fact that the vital link between PG and PSII is now well established, the phenotypic traits of PG-depleted cells signal that there are other sites in the photosynthetic membrane requiring strictly PG molecules. In Synechocystis sp., lack of PG triggers rapid loss of trimeric PSI complexes (Domonkos et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2004), and because PSI complexes bind more than 80% of chlorophyll (Chl) in the Synechocystis sp. cell, the PG depletion is accompanied by a characteristic Chl bleaching (Domonkos et al., 2004). However, the reasons for this symptom are still unclear. Chl metabolism is tightly coordinated with synthesis, assembly, and degradation of photosystem complexes (for review, see Komenda et al., 2012b; Sobotka, 2014), and we have shown recently that the PSI complexes are the main sink for de novo Chl produced in cyanobacteria (Kopečná et al., 2012). Given the drastic decrease in PSI content in the PG-depleted cells, Chl biosynthesis must be directly or indirectly affected after the PG concentration in membranes drops below a critical value. Although it was recently suggested that galactolipid and Chl biosyntheses are coregulated during chloroplast biogenesis (Kobayashi et al., 2014), a response of the Chl biosynthetic pathway to the altered lipid content has not been examined.

To investigate Chl metabolism during PG starvation, we used the Synechocystis sp. ΔpgsA mutant, which is unable to synthesize PG (Hagio et al., 2000). The advantage of using the ΔpgsA strain is in its ability to utilize exogenous PG from growth medium, which allows monitoring of phenotypic changes from a wild type-like situation to completely PG-depleted cells. Chl biosynthesis shares the same metabolic pathway with heme and other tetrapyrroles. At the beginning of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, the initial precursor, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), is made from Glu through glutamyl-tRNA and subsequently converted in several steps to protoporphyrin IX. The pathway branches at the point where protoporphyrin IX is chelated by magnesium to produce Mg-protoporphyrin IX, the first intermediate on the Chl branch. This step is catalyzed by Mg-chelatase, a multisubunit enzyme that associates relatively weakly with the membrane; however, all following enzymes downward in the pathway are almost exclusively bound to membranes (Masuda and Fujita, 2008; Kopečná et al., 2012). The last enzyme of the Chl pathway, Chl synthase, is an integral membrane protein that attaches a phytyl chain to the last intermediate chlorophyllide (Chlide) to finalize Chl formation (Oster et al., 1997; Addlesee et al., 2000). According to current views, Chl synthase should also be involved in reutilization of Chl molecules from degraded Chl-binding proteins, which includes dephytylation and phytylation of Chl molecules with Chlide as an intermediate (Vavilin and Vermaas, 2007).

In this study, we show a complex impact of PG deficiency on Chl metabolism. The lack of PG inhibited Chl biosynthesis at the two different steps: first, it drastically reduced formation of the initial precursor ALA, and second, it impaired the Mg-protoporphyrin methyl ester IX (MgPME) cyclase enzyme catalyzing synthesis of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide). The diminished rate of Chl formation was accompanied by impaired synthesis of both trimeric and monomeric PSI complexes and accumulation of a PSI monomer associated with the CP43 subunit of PSII. We also showed that the PG-depleted cells accumulated Chlide, originating from dephytylation of existing Chl, which suggests an inability to reutilize Chl for the PSI synthesis. We discuss a scenario that the Chl biosynthesis and synthesis of core PSI subunits are colocated in PG-enriched membrane microdomains.

RESULTS

PG Depletion Results in Inhibition of De Novo Chl Biosynthesis in Synechocystis sp. Cells

The ΔpgsA cells supplemented with PG accumulated about 25% of PG in total lipids, which is significantly more than a typical PG content for the Synechocystis sp. wild type (approximately 10%; Table I). However, after replacing PG-supplemented growth medium by fresh growth medium lacking PG, the PG level in the mutant quickly dropped down to 2% to 3% of total lipids in 2 d and about 1% in 5 d (Table I). Interestingly, even after this drastic decrease in PG content, cells were able to grow, although very slowly, for an additional 10 d (Fig. 1A). It indicates that the essential pool of PG is very small. In agreement with previous reports (Gombos et al., 2002; Bogos et al., 2010; Itoh et al., 2012), PG starvation triggered a decrease in Chl content; the loss of Chl per cell was already apparent after 48 h followed by a gradual decrease to approximately 50% of the original Chl level after 5 d (Fig. 1; Table I). After 14 d of depletion, the cellular Chl content finally dropped to approximately 15%. Between days 5 and 14 of PG starvation, cells in the culture divided roughly three times, and the Chl content per cell decreased by a factor of 3 (Fig. 1A; Table I). In theory, in a case of zero de novo synthesis of Chl proteins, three cycles of cell dividing would dilute Chl content per cell 8 times. Because the cell volume did not significantly change during the experiment (Fig. 1A), we can conclude that, even after 2 weeks of PG starvation, Synechocystis sp. cells were still able to synthesize a limited amount of Chl proteins to partially compensate for the proliferation. An intensive degradation of Chl proteins or Chl molecules during PG starvation is thus very unlikely. In contrast to the dramatic decrease of the total Chl amounts, the whole-cell absorption spectra showed that levels of phycobiliproteins remained basically unchanged (Supplemental Fig. S1). An almost identical course of Chl bleaching was observed if the ΔpgsA cells were supplemented by 0.5 mm Glu or 5 mm Glc (data not shown). It suggests that the loss of Chl complexes is not related to nitrogen/carbon deficiency or energy deprivation caused by an impaired PSII activity.

Table I. Chl content in the wild type and the ΔpgsA mutant grown in the presence or absence of PG in the growth medium.

For the recovery, the grown medium was supplemented with 20 μg mL−1 PG. Each value represents the mean ± sd from three independent experiments.

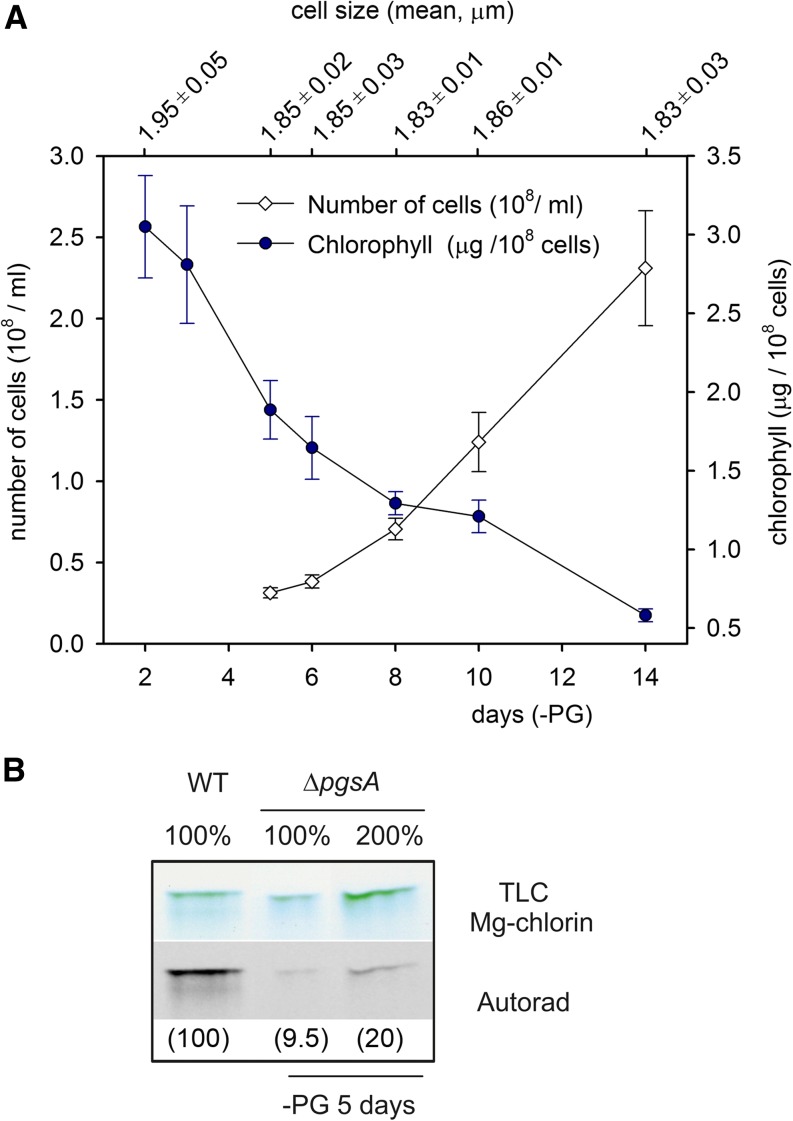

Figure 1.

Changes in Chl content and rate of Chl formation during PG depletion in the ΔpgsA mutant. A, Concentration of Chl per 108 cells (blue circles), cells proliferation (white diamonds), and mean of cell volume (top x axis) during PG starvation. Data represent means from three independent measurements; error bars indicate sd. B, Radiolabeling of Chl molecules in the wild type (WT) and the ΔpgsA mutant cells starved of PG for 5 d. Chl was radiolabeled by [14C]Glu using a 30-min pulse, extracted with methanol/0.2% NH4OH, and immediately converted into Mg-chlorin to remove phytol chain and 13- methyl group. Mg-chlorin was separated on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (“Materials and Methods”), and radioactivity was detected using an x-ray film (Autorad). The signal of labeled Mg-chlorin quantified using ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare) is shown in parentheses.

Because the result indicated that the observed Chl bleaching during PG starvation could be linked to reduced Chl production in cells, we used 14C incorporation into Chl as a measure of the rate of Chl biosynthesis. Cells of the wild type and ΔpgsA mutant were labeled by [14C]Glu. Extracted Chl was converted to Mg-chlorin and separated by a thin-layer chromatography, and the chromatographic plate was exposed to an x-ray film (Kopečná et al., 2012). Indeed, the ΔpgsA strain cultivated in a PG-free medium for 5 d showed a very small rate of de novo synthesis of Chl, because the signal of labeled Mg-chlorin did not exceed 10% of that found in the wild-type strain (Fig. 1B).

PG-Depleted Cells Lack Chl Precursors But Accumulate Chlide, Which Originates from Chl Dephytylation

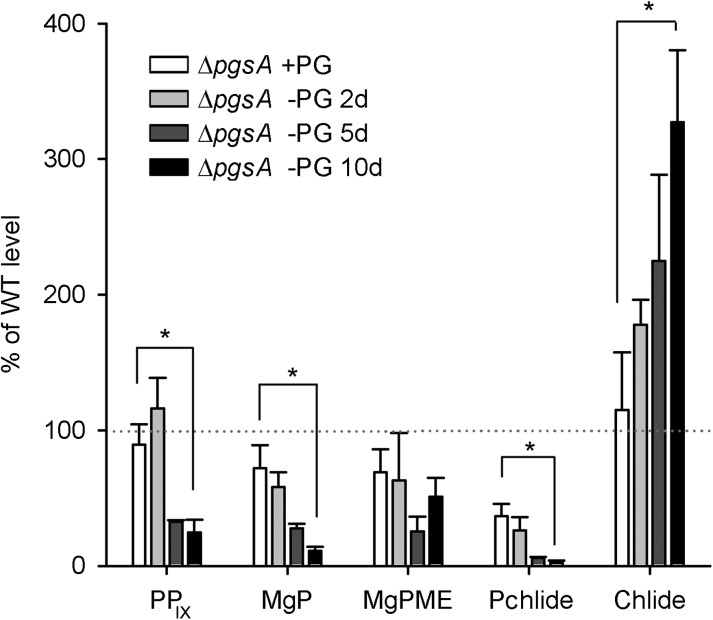

To evaluate Chl biosynthesis in more detail and localize its limiting step(s) during PG depletion, we analyzed intermediates of this metabolic pathway. The ΔpgsA strain grown in the presence of PG accumulated similar levels of Chl precursors as the wild type with exception of Pchlide, which reached only about 50% of that in the wild type (Fig. 2). A short 2-d PG starvation had no detectable effect on the precursor levels, but after 5 d, a dramatic reduction of the Pchlide pool was observed (<10% of that in the wild type); also, there was significantly less protoporphyrin IX, Mg-protoporphyrin IX, and MgPME. After 10 d of PG starvation, only traces of Pchlide could be detected, whereas the MgPME level exhibited an increase, indicating a block in the conversion of MgPME to Pchlide.

Figure 2.

Analysis of intermediates of Chl biosynthesis in the PG-depleted ΔpgsA mutant. Quantification of Chl precursors in the mutant grown in a PG-supplemented medium (+PG) or under PG-depleted conditions (−PG) for the indicated number of days. Cells (2 mL) were harvested at optical density at 750 nm (OD750) = 0.4, and Chl precursors were extracted with methanol and quantified by HPLC (“Materials and Methods”). Values represent mean ± sd from three independent measurements; the dotted line indicates wild-type (WT) level calculated as a mean of three independent measurements. MgP, Mg-protoporphyrin IX; PPIX, protoporphyrin IX; *, significant difference tested using a paired t test (P = 0.05).

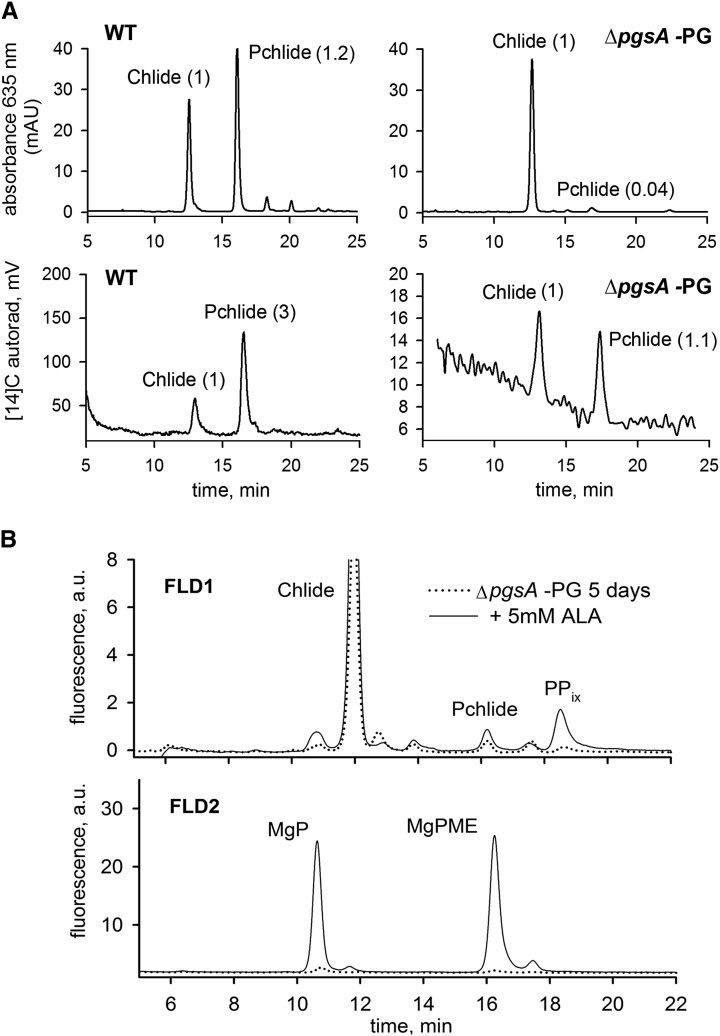

Notably, the last Chl intermediate Chlide gradually increased during the PG depletion, although the preceding intermediate Pchlide in the pathway became barely detectable (Fig. 2). However, Chlide is also an intermediate of Chl reutilization (Vavilin and Vermaas, 2007) and can be produced by dephytylation of existing old Chl molecules. To distinguish between Chlide produced de novo from Pchlide and Chlide produced as an intermediate of Chl recycling, we supplemented cell cultures of the wild type and the ΔpgsA strain grown without PG for 5 d with [14C]Glu and monitored its incorporation into Pchlide and Chlide (Fig. 3). In the wild type, we found that, after 30 min, approximately 3 times more [14C]Glu was incorporated into Pchlide than into Chlide, which corresponded to a higher total pool of Pchlide compared with Chlide. This result indicated that either de novo synthesis of Chlide was lagging behind the synthesis of Pchlide and resulted in accumulation of newly synthesized Pchlide or de novo-formed Chlide was quickly converted into Chl molecules. In contrast, the PG-starved ΔpgsA strain accumulated 25 times more Chlide than Pchlide; however, their [14C]Glu labeling result was similar, meaning that only 4% of detected Chlide was newly synthesized. This means that the vast majority of Chlide detected in the PG-depleted ΔpgsA strain was formed by detachment of phytol from previously synthesized Chl and did not originate from de novo biosynthesis.

Figure 3.

Pulse radiolabeling of Chlide and Pchlide in the ΔpgsA strain and assessment of Chl precursor levels after ALA feeding. A, Wild-type (WT) and ΔpgsA cells grown without PG for 5 d were radiolabeled with [14C]Glu using a 30-min pulse. Chl precursors were extracted by methanol, concentrated by evaporation, and immediately injected into an HPLC system equipped with a diode-array detector and a flow scintilator. The HPLC chromatograms (upper) show peaks of Chlide and Pchlide detected by A635, and the values indicate molar stoichiometries of these pigments calculated from authentic standards. The chromatograms (lower) show radioactive signals (autorad) of the identical measurement depicted above (in this case, values indicate areas of integrated peaks). Note the different scale of the y axis for the wild type and the mutant. B, Content of Chl precursors in ΔpgsA cells PG depleted for 5 d and then fed by 5 mm ALA for 1 h. Extracted pigments were separated by HPLC equipped by two fluorescence detectors (FLD1 and FLD2). Each detector was set to wavelengths allowing them to detect indicated Chl precursors (“Materials and Methods”).

The Chl Biosynthesis Is Blocked at Two Sites during PG Depletion, and Levels of Most Enzymes Are Decreased while the Chl Synthase Overaccumulates

The attenuated total metabolite flow through the Chl pathway after PG starvation together with a transient accumulation of MgPME and the drastic reduction in Pchlide and de novo Chlide pools (Figs. 2 and 3A) indicated a block at the beginning of the tetrapyrrole pathway and another block at the Pchlide formation. To assess potential bottlenecks in the Chl pathway, we supplemented the ΔpgsA culture (PG depleted for 5 d) with 5 mm ALA for 1 h and detected accumulated Chl precursors (Fig. 3B). Compared with control ΔpgsA cells grown without ALA, it was obvious that the external ALA dramatically elevates levels of Chl precursors preceding the cyclase step (approximately 7 times for protoporphyrin IX, approximately 25 times for Mg-protoporphyrin, and approximately 60 times for MgPME; Fig. 3B). In contrast, the Pchlide pool was almost unchanged (Fig. 3B). These data showed that all enzymes preceding MgPME cyclase are functional in cells lacking PG but that the metabolite flow through the pathway is kept low because of a restriction on the ALA formation step.

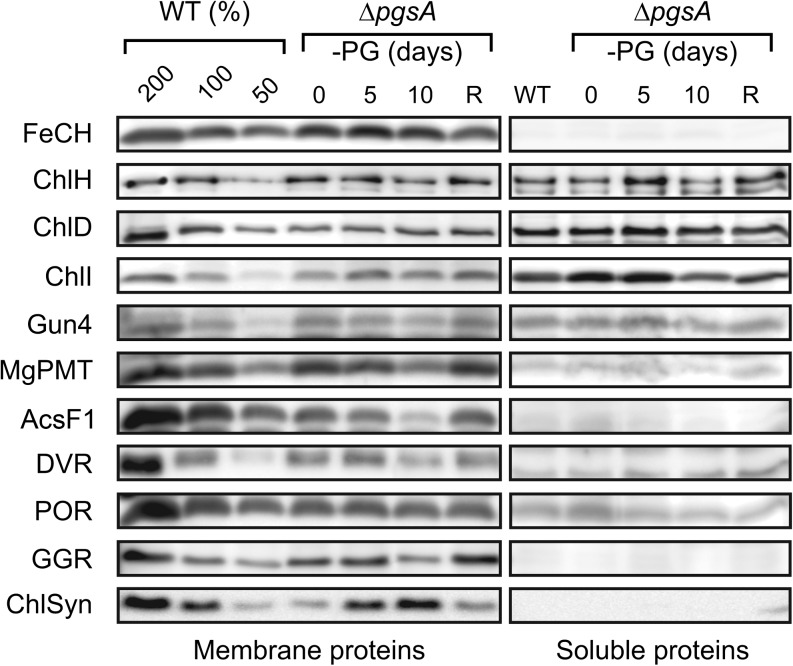

The monitoring of the abundance of enzymes involved in Chl biosynthesis by specific antibodies showed very different responses of individual enzymes to the PG starvation. Only the ChlD subunit of Mg-chelatase, the MgPME cyclase, and Chl synthase showed significantly lowered levels in ΔpgsA cells in the presence of PG, whereas levels of other enzymes were relatively similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 4). Notably, after 5 d of PG starvation, the Chl synthase level doubled, whereas levels of other enzymes remained stable. Additional growth with no external PG, however, affected accumulation of most enzymes; only the ferrochelatase enzyme producing heme and light-dependent Pchlide oxidoreductase remained stable during 10 d of PG starvation (Fig. 4). On the contrary, the MgPME cyclase was almost lost completely, which was in agreement with the increased level of MgPME observed in these cells (Fig. 2). An interesting exception was the Chl synthase, which exhibited the opposite trend, reaching its highest level after 10 d of PG depletion. No enzymes catalyzing later steps in Chl biosynthesis accumulated in soluble protein fraction during PG starvation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Quantification of enzymes of the Chl biosynthetic pathway in the ΔpgsA mutant. The ΔpgsA mutant was grown in PG-depleted medium for the indicated number of days and then supplemented with PG for 3 d for the recovery (R). Membrane and soluble protein fractions were separated by SDS electrophoresis and blotted to a PVDF membrane. Enzymes were detected by specific antibodies. The amount of proteins loaded for 100% of each sample corresponds to 100 μL of cells at OD750nm = 1. ChlH, ChlD, and ChlI are subunits of the magnesium chelatase, and Genome Uncoupled4 protein (Gun4) is a protein required for the magnesium chelatase activity. AcsF1 (Sll1214) is a component of the MgPME oxidative cyclase. ChlSyn, Chl synthase; DVR, 3,8-divinyl chlorophyllide 8-vinyl reductase; FeCH, ferrochelatase; GGR, geranylgeranyl reductase; MgPMT, Mg-protoporphyrin methyl transferase; POR, light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase; WT, wild type.

Loss of Chl in PG-Depleted Cells Parallels Inhibition of PSI Synthesis and Formation of the PSI-CP43 Complex

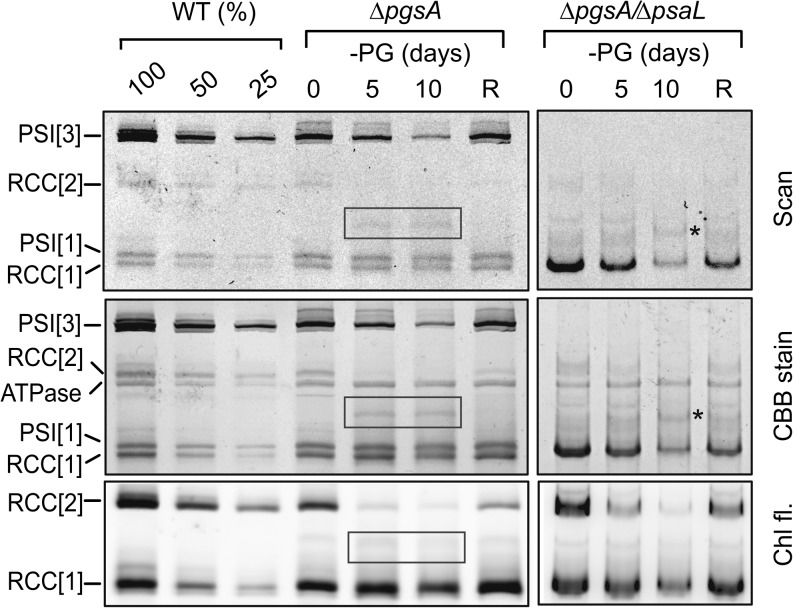

Because the majority of Chl molecules in Synechocystis sp. cells are present in the trimeric PSI, Chl depletion induced by lack of PG was expected to reflect the disappearance of this Chl-binding complex. This was confirmed by analysis of membrane protein complexes using Clear Native gel electrophoresis. This type of separation allowed us to visualize PSI complexes directly in the gel scans and PSII complexes using fluorescence of Chl molecules bound to PSII proteins (Fig. 5). In contrast to the trimer, the content of PSI monomers did not seem to be affected by a lack of PG (Supplemental Table S1). The gel also confirmed a previous observation by Sakurai et al. (2003) that the level of the PSII core dimers was largely reduced in the PG-deprived mutant cells, whereas accumulation of the monomeric form of PSII was affected to a lesser extent (Supplemental Table S1). The observed stable level of monomeric PSI could indicate that the biogenesis of this PSI complex is much less sensitive to PG deficiency than the trimeric form. Alternatively, these PSI monomers could also originate from disassembly of trimeric complexes as proposed by Domonkos et al. (2004). To clarify this point, we inactivated the psaL gene in the ΔpgsA mutant to block trimerization of PSI (Chitnis and Chitnis, 1993). The course of chlorosis during PG starvation was very similar in the ΔpgsA and the ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL mutants (Supplemental Fig. S1), whereas the Clear Native gel showed a gradually decreasing level of monomeric PSI in the double mutant (Fig. 5). We can conclude that the apparently stable pool of monomeric PSI in the PG-depleted ΔpgsA primarily results from the ongoing disintegration of PSI trimers.

Figure 5.

Contents of membrane protein complexes in the wild type (WT) and ΔpgsA and ΔpgsA/psaL strains during PG depletion. Membrane complexes isolated from the PG-depleted cells were separated by 4% to 12% Clear Native electrophoresis; R indicates 3 d of recovery. The amount of proteins loaded for 100% of each sample corresponds to 200 μL of cells at OD750nm = 1. The gel was scanned in transmittance mode (scan) using an LAS 4000 Imager (Fuji), and to visualize PSII monomer and dimer, Chl fluorescence emitted by PSII was excited by blue light and detected also by LAS 4000 (Chl fl.). Finally, the gel was then stained by Coomassie Blue (CBB stain). Designations of complexes are PSI[3] and PSI[1] for trimeric and monomeric PSI, respectively, RCC[2] and RCC[1] for dimeric and monomeric PSII core complexes, respectively, and ATPase for ATP synthase. The boxed areas and asterisks highlight a pigmented complex accumulated during PG depletion. For the quantification of individual bands using ImageQuant software, see Supplemental Table S1.

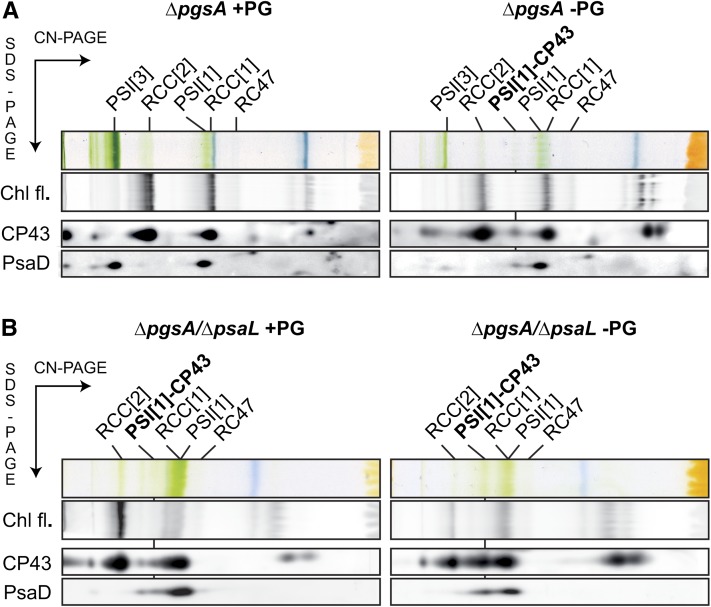

Intriguingly, a unique pigmented complex (molecular mass of approximately 450 kD) migrating on native electrophoresis between PSII dimer and PSI monomer was detected in the PG-depleted cells of both ΔpgsA mutants (Fig. 5). To clarify composition of this complex, we performed two-dimensional (2D) Clear Native/SDS electrophoresis of membrane proteins isolated from ΔpgsA and ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL strains. Staining of the gel by Sypro Orange revealed that the 450-kD complex is a monomeric PSI associated with CP43 (Supplemental Fig. S2), and this was further confirmed by blotting of 2D gel followed by immunodetection of CP43 and PSI subunit PsaD (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

2D analysis of the membrane protein complexes isolated from ΔpgsA (A) and ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL (B) strains grown with PG and without PG for 10 d. Membrane proteins were separated by 4% to 14% Clear-Native (CN)-PAGE and then, in the second dimension, by 12% to 20% SDS-PAGE. The 2D gel was stained by Sypro Orange (for stained gels, see Supplemental Fig. S2) and then blotted to a PVDF membrane. CP43 and PsaD proteins were detected by specific antibodies. Protein complexes were designated as in Figure 5. PSI[1]-CP43 denominates the complex between CP43 and monomeric PSI. Chl fluorescence emitted by PSII is also shown (Chl fl.). Designations of complexes are PSI[3] and PSI[1] for trimeric and monomeric PSI, respectively, and RCC[2] and RCC[1] for dimeric and monomeric PSII core complexes, respectively.

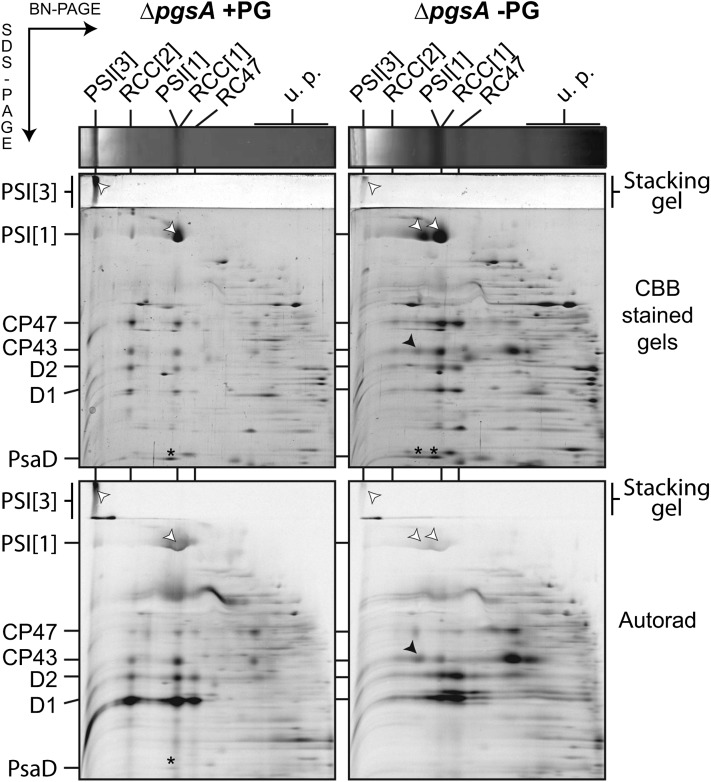

To explore de novo synthesis of PSI and PSII subunits and their assembly into high-molecular mass complexes in the ΔpgsA mutant, we monitored the incorporation of radioactive amino acids into membrane proteins. The solubilized membranes from radiolabeled cells were separated by 2D Blue Native/SDS electrophoresis, and the stained 2D gel was finally exposed to a phosphorimager to visualize labeled protein spots (Fig. 7). The ΔpgsA strain grown without PG for 5 d accumulated very low amounts of de novo assembled PSII dimer, whereas the labeled PSII monomer remained still fairly abundant. Interestingly, the newly synthesized PSII core complex lacking CP43 (RC47) assembly intermediate of PSII (Boehm et al., 2012) with highly labeled D2 and D1 subunits accumulated significantly more, indicating disruption of the de novo assembly of PSII at the step of CP43 attachment. The assembly of PSII is obviously impaired, despite the presence of an abundant and intensively labeled CP43 assembly module, which consists of the CP43 associated with small PSII subunits PsbK, PsbZ, and Psb30 (Fig. 7; Komenda et al., 2004, 2012a, 2012b). In agreement with the analysis of the ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL strain (Fig. 5), the PG depletion strongly suppressed synthesis of both monomeric and trimeric PSI complexes. Interestingly, the PSI-CP43 complex contained a portion of radioactively labelled CP43 comparable with the portion incorporated into the monomeric PSII (Fig. 7). In conclusion, the synthesis of both PSI monomer and trimer was inhibited to a similar extent by lack of PG, whereas the synthesis of PSII Chl proteins remained intensive and the newly synthesized CP43 associated with PSI.

Figure 7.

Synthesis of the CP43-PSI complex in the ΔpgsA mutant cells grown in a PG-depleted medium for 5 d. Cells were radiolabeled with [35S]Met/Cys mixture using a 20-min pulse. Membrane proteins corresponding to 5 µg of Chl were separated by Blue Native (BN) electrophoresis on a 4% to 14% linear gradient gel, and another 12% to 20% SDS electrophoresis was used for the second dimension. The 2D gels were stained with Coomassie Blue (CBB-stained gels) and then dried, and the labeled proteins were detected by a phosphoimager (Autorad). Protein complexes were designated as in Figure 1. The white arrows indicate PsaA/B core subunits, and the black arrows indicate the CP43 associated with PSI[I] (the PSI[1]-CP43 complex) on both the stained gel and the autoradiogram. Designations of complexes are PSI[3] and PSI[1] for trimeric and monomeric PSI, respectively, and RCC[2] and RCC[1] for dimeric and monomeric PSII core complexes, respectively. *, PsaD subunit of PSI; u.p., unassembled proteins.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that decrease in cellular level of Chl in PG-depleted Synechocystis sp. cells correlates with inhibition of the Chl biosynthesis pathway, which was documented by the low rate of incorporation of 14C isotope into Chl and overall decreased levels of Chl precursors. Although we lack information about early intermediates of the tetrapyrrole biosynthesis pathway, the PG depletion was accompanied by a significant decrease in the level of protoporphyrin IX—the last common substrate for the synthesis of both Chl and heme. It indicates that the lack of PG restricted total metabolite flow through the tetrapyrrole pathway. Indeed, levels of all monitored precursors up to Pchlide can be strongly elevated by supplementing PG-starved cells with the initial precursor ALA. Notably, the content of phycobilisomes is much less affected by lack of PG (Supplemental Fig. S1), implying that the remaining traces of protoporphyrin IX are preferentially channeled to ferrochelatase for heme and bilin synthesis. It might be related to an intriguing surplus of ferrochelatase enzyme in Synechocystis sp. cells observed earlier (Sobotka et al., 2008b); a Synechocystis sp. ferrochelatase mutant possessing only about 10% of the ferrochelatase activity produced enough heme to maintain the cellular level of heme and phycobilisomes.

The MgPME oxidative cyclase seems to be the only enzyme involved in Chl biosynthesis, activity that is markedly inhibited by low PG content. It is, however, difficult to speculate about the role of PG in the formation of Pchlide, because this enzymatic step is poorly characterized. The Aerobic cyclization system Fe-containing protein (AcsF protein; Sll1214) is the only known component of MgPME cyclase; however, there are probably other essential subunits (see Hollingshead et al., 2012 and discussion therein). For the assembly of functional MgPME cyclase complex, PG could play a critical role. It is attractive to speculate that a block in Pchlide synthesis turns down the whole tetrapyrrole pathway consistently with some observations in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) AcsF-antisense plants (Peter et al., 2010). However, Synechocystis sp. mutants with low AcsF content accumulate huge amounts of MgPME and protoporphyrin IX as well (Peter et al., 2009; Hollingshead et al., 2012), which indicates that, at least in cyanobacteria, there is no tight feedback between cyclase activity and the rate of ALA synthesis.

An enigmatic point is the low level of Chl synthase in PG-supplemented ΔpgsA cells (Fig. 5). We can only speculate that the content of this membrane enzyme is somehow negatively influenced by the aberrantly high content of PG (Table I). However, unlike other enzymes in the Chl pathway, the level of Chl synthase was strongly elevated in PG-deprived cells. We believe that this enzyme is essential under conditions where de novo Chl synthesis is blocked and reutilization of Chl released from Chl proteins must be very efficient. There is solid experimental evidence provided by Vavilin et al. (2005) that Chl has a much longer lifetime than individual Chl-binding apoproteins, and it implies that Chl must be recycled. Moreover, Vavilin et al. (2005) showed that at least some reused Chl undergo a cycle of dephytylation catalyzed by an unknown enzyme and repeated phytylation catalyzed by Chl synthase. Therefore, accumulation of increased amounts of Chl synthase is not surprising, because dividing cells can only rely on recycled Chl, which should be used at the highest efficiency, and therefore, Chl synthase is required. For this reason, detection of an increasing level of Chlide during PG depletion was surprising. This Chlide could apparently not be used for Chl formation and repeated incorporation into Chl protein. A possible reason for this phenomenon could be localization of this pool of Chlide in a membrane region that is not available for Chl synthase and/or protein synthesis machinery to be incorporated into newly synthesized Chl proteins. Alternatively, the Chl reutilization could be limited by lack of isoprenoids/phytol, but in such a case, the PG depletion should also result in lowering levels of all carotenoids. As shown in Supplemental Figure S3, a long-term PG deficiency (14 d) reduced content of β-carotene or zeaxanthin, but the content of myxoxanthophyl was more than 4 times higher than in control (+PG) cells. We, therefore, do not expect that the PG is required for the isoprenoid biosynthesis.

The inhibition of Chl biosynthesis during PG deprivation was most obviously accompanied by the steep decrease in the level of PSI trimer, which has been shown to represent the main sink of newly synthesized Chl in Synechocystis sp. cells (Kopečná et al., 2012). For strains lacking PsaL, the main sink for de novo Chl is almost certainly the monomeric PSI, and again, PG deficiency in the pgsA/psaL mutant triggered the loss of this complex. Based on our measurement of Chl content per cell correlated with cell proliferation (Fig. 1A), we can almost rule out that the low PG content causes an extensive PSI degradation. In fact, on the contrary, it is clear that PG-depleted cells are still able to partly compensate for dilution of complexes during cell growth; however, the synthesis of PSI complexes is simply too weak to prevent gradual bleaching.

The origin and function of PSI monomer associated with CP43 as well as the abundance of this complex in PG-depleted cells are rather enigmatic. Such a complex has been recently identified in the strain lacking CP47, which contains significant amounts of unassembled CP43 (Komenda et al., 2012a). Indeed, PG depletion has been shown to impair PSII assembly process and namely, destabilize binding of CP43 antenna within PSII core, resulting in an increased fraction of unassembled CP43 (Laczkó-Dobos et al., 2008). This effect was confirmed in this study; however, significant radioactive labeling of CP43 bound to PSI suggests that this interaction occurs during or early after de novo synthesis of CP43. We are tempted to speculate that a transient association of de novo CP43 with PSI before its integration into RC47 is a standard step of PSII biogenesis. Absence of Chl fluorescence emitted by the PSI-CP43 complex (Fig. 5) shows an efficient energy transfer from CP43 to PSI, making, in theory, PSI monomer an effective protector of the newly synthesized CP43 against photodamage. Alternatively, PSI could also provide Chl for the newly synthesized CP43; it has been recently proposed that PSI could act as a donor of Chl for a newly formed PSII RC complex consisting of D1 and D2 (Knoppová et al., 2014). It is worth noting that the synthesis of CP43 is much less sensitive to the lack of de novo Chl than the synthesis of the structurally similar CP47 protein (Sobotka et al., 2008a). Indeed, the CP43 as well as D1 and D2 proteins are intensively synthesized in cells that produce only about 10% of de novo Chl molecules (Fig. 7). These results are in line with our model that cyanobacteria utilizes the majority of fresh Chl molecules to maintain a constant level of Chl-rich and long-lived PSI complexes (Kopečná et al., 2012). Short-lived PSIIs are produced by a different protein machinery, which included components for Chl recycling and potentially, stripping Chl molecules from PSI. The fact that the syntheses of PSII and PSI subunits take place on separated translocon systems has been shown recently (Linhartová et al., 2014).

There is a tight interconnection between Chl biosynthesis and synthesis of Chl-binding proteins. A complete inhibition of Chl biosynthesis ultimately blocks synthesis of all Chl proteins (Kopečná et al., 2013), most likely because the insertion of Chl molecules into growing polypeptides is a prerequisite for the correct folding of Chl-binding proteins (for review, see Sobotka, 2014). Interestingly, there is also an opposite control, because we found that the inhibition of protein translation by chloramphenicol immediately stops Chl biosynthesis (R. Sobotka and J. Komenda, unpublished data). Given this cross talk between translation of apoproteins and Chl synthesis, it is difficult to distinguish which process is actually more sensitive to low PG content. The PSI contains three PG molecules, of which two are rather peripheral, but one is buried within the PsaA subunit (Jordan et al., 2001). This suggests that a certain level of PG could be critical for proper folding of PsaA or assembling of PSI and that the observed down-regulation of the tetrapyrrole pathway might simply represent a response to impaired PSI synthesis. However, the ALA-producing enzyme in plants has been shown to be integrated into a membrane complex (Czarnecki et al., 2011), and PG could be essential for ALA formation. Without de novo Chl, the PSI synthesis is certainly arrested. We, however, propose another more complex scenario, which reflects current knowledge about PG function in prokaryotes.

According to the available data, Chl proteins are synthesized on membrane-bound ribosomes and inserted into membrane through SecY translocase (Zhang et al., 2001; for review, see Sobotka, 2014), and as shown recently, the Chl synthase is physically attached to the translocon system through YidC insertase (Chidgey et al., 2014). Although clear evidence is still missing, there are good reasons to expect that all enzymes of the Chl pathway, including MgPME cyclase, are assembled into a larger metabolomic unit around translocons (Kauss et al., 2012; Chidgey et al., 2014). Such large assemblies of enzymes providing de novo Chl would be particularly critical for the PSI synthesis. Interestingly, it has become apparent that PG or cardiolipin (two linked PG molecules) domains colocalize with SecY translocons within bacterial cells (Gold et al., 2010; Tsui et al., 2011). In addition, the functioning of the SecY translocase in Escherichia coli was shown to be dependent on cardiolipin—the major anionic lipid in this bacterium (Gold et al., 2010). In another example, in Bacillus subtilis, the SecY exhibits characteristic spiral patterns of localization that are lost during PG depletion (Campo et al., 2004). The increasing experimental evidence suggests that phospholipids in bacteria form microdomains, which are important for the translocon localization and function. Taking into account that the functional link between phospholipids and translocon apparatus is conserved in both gram-negative and -positive bacteria, it is quite likely that PG molecules colocalize with cyanobacterial translocons as well. Such PG- and SecY-rich microdomains could be in fact identical to proposed biosynthetic centers—large protein factories responsible for synthesis of photosynthetic complexes. The presence of such centers (or zones) has already been shown in green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Schottkowski et al., 2012), and they are also expected to occur in cyanobacteria (for review, see Komenda et al., 2012b; Rast et al., 2015). We speculate that lack of PG disintegrates membrane microdomains essential for PSI synthesis. It seems completely sensible that the first (ALA-producing) steps of the tetrapyrrole pathway would be colocated in the same membrane foci and activated only during translation of core PSI subunits. This model needs to be tested in the future; however, it agrees with the simultaneous inhibition of both PSI and Chl synthesis by low PG content observed in this work.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Synechocystis sp. Mutants and Growth Conditions

The Synechocystis sp. ΔpgsA mutant strain is described in Hagio et al., 2000. To prepare the ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL strain, the psaL gene in the ΔpgsA mutant was replaced with an ω-cassette conferring spectinomycin resistance (Kłodawska et al., 2015). If not stated otherwise, both Synechocystis sp. mutants were grown photoautotrophically at 29°C under continuous illumination of 30 µmol of photons m−2 s−1 in a liquid BG11 medium supplemented with 20 µm dioleoyl-PG (Sigma). PG depletion was achieved by washing the cells two times with PG-free medium followed by cultivation in a fresh PG-free medium. Wild-type cells were grown in the PG-free medium. Cultures were aerated on a rotary shaker.

Absorption Spectra and Determination of Chl Content

Absorption spectra of whole cells were measured at room temperature with a Shimadzu UV-3000 Spectrophotometer. Chl was extracted from cell pellets (2 mL; OD750nm = approximately 0.4) with 100% methanol, and its concentration was measured spectrophotometrically according to the work by Porra et al. (1989). Numbers of cells and their sizes were determined in 0.9% (v/v) NaCl electrolyte solution with a calibrated Coulter Counter (Beckman Multisizer IV) equipped with a 20-µm aperture.

Lipid Analysis

Lipids were extracted from 1 mL of pelleted cells (OD750nm = approximately 0.5) by 0.5 mL of chloroform and methanol solution using a beadbeater as described in Košťál and Šimek, 1998. A small amount (5 µL) of the obtained extract was injected into the Surveyor HPLC System connected to the Ion Trap LTQ Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan). Samples were separated on the Gemini column (250 × 2 mm, 3 µm; Phenomenex) using 5 mm ammonium acetate in methanol as the mobile phase (A), water as B, and 2-propanol as the phase (C). The analysis was performed using the following gradient: 0 to 5 min of 92% A and 8% B, 5 to 12 min of 100% A, 12 to 50 min of 100% to 40% A and 0% to 60% C, 50 to 65 min of 40% A and 60% C, and 65 to 80 min back to 92% A and 8% B. The separation was run with a flow rate of 250 µL min−1 at 30°C. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive and negative ion detection modes at +4 and −4 kV, respectively, with capillary temperature at 220°C and nitrogen as the shielding and auxiliary gas. To obtain the full-scan electrospray ionization mass spectra of lipids, mass range of 140 to 1,400 D was scanned every 0.5 s. Identification of particular lipids was achieved by collision-induced dissociations. Peak areas of detected lipid classes (monogalactosyldiacylglycerol, DGDG, SQDG, and PG) were used for the estimation of their relative content in the analyzed samples.

Isolation and Analysis of Membrane Protein Complexes

Membrane proteins were isolated from 50 mL of cells at OD750nm = approximately 0.4 according to Dobáková et al. (2009) using buffer A (25 mm MES-NaOH, pH 6.5, 5 mm CaCl2, 10 mm MgCl2, and 20% [w/v] glycerol). Isolated membrane complexes were solubilized in buffer A containing 1% (w/v) N-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside and analyzed by native or denaturing electrophoresis as described in Kopečná et al., 2013. Proteins separated in the gel were stained by either Coomassie Blue or Sypro Orange followed by transfer onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies and then, a secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). The CP43 and PsaD primary antibodies were raised in rabbits against whole proteins isolated from Synechocystis sp. Antibodies raised against subunits of Mg-chelatase, Mg-protoporphyrin methyltransferase, light-dependent Pchlide oxidoreductase, 3,8-divinyl Pchlide 8-vinyl reductase, and geranylgeranyl reductase were provided by C. Neil Hunter (University of Sheffield). Ferrochelatase and Genome Uncoupled4 protein antibodies were provided by Annegret Wilde (University of Freiburg). The antibodies raised against barley AcsF were provided by Poul Erik Jensen (University of Copenhagen). The Synechocystis sp. Chl synthase antibodies were raised in rabbit against the synthetic peptide containing amino acid residues 89 to 104 of Slr0056.

Quantification of Chl Precursors

For quantitative determination of Chl precursors in the cells, 2 mL of culture at OD750nm = approximately 0.4 was harvested, and the pellet was resuspended in 25 µL of ultrapure water. To extract Chl precursors, cells were mixed with 75 µL of methanol, and this solution was incubated in complete darkness and at room temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, the sample was centrifuged, the supernatant containing extracted pigments was collected, and the extraction was repeated using the same volume of methanol. Obtained supernatants were combined, and 150 μL were immediately separated by HPLC (Agilent-1200; Agilent) on an RP Column (Nova-Pak C18, 4-μm particle size, 3.9 × 150 mm; Waters) using 30% (v/v) methanol in 0.5 m ammonium acetate and 100% (v/v) methanol as solvents A and B, respectively. Porphyrins were eluted with a linear gradient of solvent B (65%–75% in 30 min) at a flow rate of 0.9 mL min−1 at 40°C. HPLC fractions containing Mg-protoporphyrin IX (retention time of approximately 11 min), Chlide (approximately 12 min), Pchlide (approximately 16 min), MgPME (approximately 17 min), and protoporphyrin IX (approximately 19 min) were detected by two fluorescence detectors, with the first fluorescence detector set to 440/650 nm (excitation/emission wavelengths) for 0 to 17 min and 400/630 nm for 17 to 25 min and the second set at 416/595 nm throughout the experiment.

Radioactive Labeling of Proteins and Pigments

Radioactive pulse labeling of the proteins in cells was performed using a mixture of [35S]Met and [35S]Cys (Translabel; MP Biochemicals). After a short (20 min) incubation of cells with labeled amino acids, the solubilized membranes isolated from radiolabeled cells were separated by 2D Blue Native/SDS electrophoresis. The stained 2D gel was finally exposed to a phosphorimager plate, which was scanned by Storm (GE Healthcare) to visualize labeled protein spots (Dobáková et al., 2009).

Chl was labeled by [14C]Glu (specific activity of 267 mCi mmol−1; Moravek Biochemicals), and the incorporation of radioactivity was quantified essentially as described in Kopečná et al., 2012. For quantitative analysis of radioactively labeled Chl precursors, 200 mL of Synechocystis sp. cells with OD750nm = 0.4 were labeled with [14C]Glu as described above. Washed and harvested cells were resuspended by 30 s of vortexing using 450 µL of water and 50 µL of zirconia/silica beads. Chl precursors were extracted by adding 1.1 mL of methanol to achieve a final concentration of 70% (v/v). Cell debris was then pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at maximal speed, and extraction was repeated one more time. Supernatants from both extractions were pooled and completely evaporated under vacuum at 35°C using a rotary evaporator. Dry extracts were then dissolved in 200 µL of methanol, and Chl precursors were separated as described above. The eluted pigments were detected by a diode-array detector (Agilent 1260) set at 635 nm connected to a flow scintillation analyzer (Radiomatic 150TR; Perkin Elmer) set for detection and quantification of 14C isotope.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Whole-cell spectra of the ΔpgsA and ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL mutants.

Supplemental Figure S2. 2D analysis of the membrane protein complexes isolated from ΔpgsA and ΔpgsA/ΔpsaL strains.

Supplemental Figure S3. Pigment content in the ΔpgsA mutant grown in medium supplemented with PG and under PG-depleted conditions for 14 d.

Supplemental Table S1. Quantification of PSI and PSII complexes in the ΔpgsA mutant during PG depletion.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Neil Hunter (Sheffield University, United Kingdom) and Annegret Wilde (University of Freiburg, Germany) for the antibodies, the Laboratory of Analytical Biochemistry and Metabolomics (Biology Centre, Czech Academy of Sciences) for free access to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry instruments, and Bára Zdvihalová (Institute of Microbiology, Trebon, Czech Republic) for technical assistance.

Glossary

- ALA

5-aminolevulinic acid

- Chl

chlorophyll

- Chlide

chlorophyllide

- DGDG

digalactosyldiacylglycerol

- 2D

two dimensional

- MgPME

Mg-protoporphyrin methyl ester IX

- Pchlide

protochlorophyllide

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- SQDG

sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Program of Sustainability I (identification no. LO1416), the Czech Science Foundation (project nos. Algain [EE2.3.30.0059] and P501/12/G055), the Czech and Hungarian Academy of Sciences (project no. HU/2013/06), and the Hungarian Research Fund (project no. OTKA 108411 to M.K. and Z.G.).

References

- Addlesee HA, Fiedor L, Hunter CN (2000) Physical mapping of bchG, orf427, and orf177 in the photosynthesis gene cluster of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: functional assignment of the bacteriochlorophyll synthetase gene. J Bacteriol 182: 3175–3182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki M, Sato N, Meguro A, Tsuzuki M (2004) Differing involvement of sulfoquinovosyl diacylglycerol in photosystem II in two species of unicellular cyanobacteria. Eur J Biochem 271: 685–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awai K, Ohta H, Sato N (2014) Oxygenic photosynthesis without galactolipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 13571–13575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awai K, Watanabe H, Benning C, Nishida I (2007) Digalactosyldiacylglycerol is required for better photosynthetic growth of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 under phosphate limitation. Plant Cell Physiol 48: 1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiychuk E, Müller F, Eubel H, Braun HP, Frentzen M, Kushnir S (2003) Arabidopsis phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase 1 is essential for chloroplast differentiation, but is dispensable for mitochondrial function. Plant J 33: 899–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm M, Yu J, Reisinger V, Beckova M, Eichacker LA, Schlodder E, Komenda J, Nixon PJ (2012) Subunit composition of CP43-less photosystem II complexes of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: implications for the assembly and repair of photosystem II. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367: 3444–3454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogos B, Ughy B, Domonkos I, Laczkó-Dobos H, Komenda J, Abasova L, Cser K, Vass I, Sallai A, Wada H, et al. (2010) Phosphatidylglycerol depletion affects photosystem II activity in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 cells. Photosynth Res 103: 19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo N, Tjalsma H, Buist G, Stepniak D, Meijer M, Veenhuis M, Westermann M, Müller JP, Bron S, Kok J, et al. (2004) Subcellular sites for bacterial protein export. Mol Microbiol 53: 1583–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidgey JW, Linhartová M, Komenda J, Jackson PJ, Dickman MJ, Canniffe DP, Koník P, Pilný J, Hunter CN, Sobotka R (2014) A cyanobacterial chlorophyll synthase-HliD complex associates with the Ycf39 protein and the YidC/Alb3 insertase. Plant Cell 26: 1267–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis VP, Chitnis PR (1993) PsaL subunit is required for the formation of photosystem I trimers in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. FEBS Lett 336: 330–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki O, Hedtke B, Melzer M, Rothbart M, Richter A, Schröter Y, Pfannschmidt T, Grimm B (2011) An Arabidopsis GluTR binding protein mediates spatial separation of 5-aminolevulinic acid synthesis in chloroplasts. Plant Cell 23: 4476–4491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobáková M, Sobotka R, Tichý M, Komenda J (2009) Psb28 protein is involved in the biogenesis of the photosystem II inner antenna CP47 (PsbB) in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 149: 1076–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domonkos I, Malec P, Sallai A, Kovács L, Itoh K, Shen G, Ughy B, Bogos B, Sakurai I, Kis M, et al. (2004) Phosphatidylglycerol is essential for oligomerization of photosystem I reaction center. Plant Physiol 134: 1471–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold VA, Robson A, Bao H, Romantsov T, Duong F, Collinson I (2010) The action of cardiolipin on the bacterial translocon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10044–10049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gombos Z, Várkonyi Z, Hagio M, Iwaki M, Kovács L, Masamoto K, Itoh S, Wada H (2002) Phosphatidylglycerol requirement for the function of electron acceptor plastoquinone Q(B) in the photosystem II reaction center. Biochemistry 41: 3796–3802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guskov A, Kern J, Gabdulkhakov A, Broser M, Zouni A, Saenger W (2009) Cyanobacterial photosystem II at 2.9-A resolution and the role of quinones, lipids, channels and chloride. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagio M, Gombos Z, Várkonyi Z, Masamoto K, Sato N, Tsuzuki M, Wada H (2000) Direct evidence for requirement of phosphatidylglycerol in photosystem II of photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 124: 795–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead S, Kopečná J, Jackson PJ, Canniffe DP, Davison PA, Dickman MJ, Sobotka R, Hunter CN (2012) Conserved chloroplast open-reading frame ycf54 is required for activity of the magnesium protoporphyrin monomethylester oxidative cyclase in Synechocystis PCC 6803. J Biol Chem 287: 27823–27833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh S, Kozuki T, Nishida K, Fukushima Y, Yamakawa H, Domonkos I, Laczkó-Dobos H, Kis M, Ughy B, Gombos Z (2012) Two functional sites of phosphatidylglycerol for regulation of reaction of plastoquinone Q(B) in photosystem II. Biochim Biophys Acta 1817: 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt HT, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauss N (2001) Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 A resolution. Nature 411: 909–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauss D, Bischof S, Steiner S, Apel K, Meskauskiene R (2012) FLU, a negative feedback regulator of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis, is physically linked to the final steps of the Mg(++)-branch of this pathway. FEBS Lett 586: 211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kłodawska K, Kovács L, Várkonyi Z, Kis M, Sozer Ö, Laczkó-Dobos H, Kóbori O, Domonkos I, Strzałka K, Gombos Z, et al. (2015) Elevated growth temperature can enhance photosystem I trimer formation and affects xanthophyll biosynthesis in Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 cells. Plant Cell Physiol 56: 558–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppová J, Sobotka R, Tichý M, Yu J, Konik P, Halada P, Nixon PJ, Komenda J (2014) Discovery of a chlorophyll binding protein complex involved in the early steps of photosystem II assembly in Synechocystis. Plant Cell 26: 1200–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Fujii S, Sasaki D, Baba S, Ohta H, Masuda T, Wada H (2014) Transcriptional regulation of thylakoid galactolipid biosynthesis coordinated with chlorophyll biosynthesis during the development of chloroplasts in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 5: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komenda J, Knoppová J, Kopečná J, Sobotka R, Halada P, Yu J, Nickelsen J, Boehm M, Nixon PJ (2012a) The Psb27 assembly factor binds to the CP43 complex of photosystem II in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol 158: 476–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komenda J, Reisinger V, Müller BC, Dobáková M, Granvogl B, Eichacker LA (2004) Accumulation of the D2 protein is a key regulatory step for assembly of the photosystem II reaction center complex in Synechocystis PCC 6803. J Biol Chem 279: 48620–48629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komenda J, Sobotka R, Nixon PJ (2012b) Assembling and maintaining the Photosystem II complex in chloroplasts and cyanobacteria. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15: 245–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopečná J, Komenda J, Bučinská L, Sobotka R (2012) Long-term acclimation of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 to high light is accompanied by an enhanced production of chlorophyll that is preferentially channeled to trimeric photosystem I. Plant Physiol 160: 2239–2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopečná J, Sobotka R, Komenda J (2013) Inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis at the protochlorophyllide reduction step results in the parallel depletion of Photosystem I and Photosystem II in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Planta 237: 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Košťál V, Šimek P (1998) Changes in fatty acid composition of phospholipids and triacylglycerols after cold-acclimation of an aestivating insect prepupa. J Comp Physiol B 168: 453–460 [Google Scholar]

- Laczkó-Dobos H, Ughy B, Tóth SZ, Komenda J, Zsiros O, Domonkos I, Párducz A, Bogos B, Komura M, Itoh S, et al. (2008) Role of phosphatidylglycerol in the function and assembly of Photosystem II reaction center, studied in a cdsA-inactivated PAL mutant strain of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 that lacks phycobilisomes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777: 1184–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linhartová M, Bučinská L, Halada P, Ječmen T, Setlík J, Komenda J, Sobotka R (2014) Accumulation of the Type IV prepilin triggers degradation of SecY and YidC and inhibits synthesis of Photosystem II proteins in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Mol Microbiol 93: 1207–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Fujita Y (2008) Regulation and evolution of chlorophyll metabolism. Photochem Photobiol Sci 7: 1131–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata N, Siegenthaler PA (1998) Lipids in photosynthesis: an overview. In Murata N, Siegenthaler PA, eds, Lipids in Photosynthesis: Structure, Function and Genetics, Vol 6 Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- Oster U, Bauer CE, Rüdiger W (1997) Characterization of chlorophyll a and bacteriochlorophyll a synthases by heterologous expression in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 272: 9671–9676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter E, Rothbart M, Oelze ML, Shalygo N, Dietz KJ, Grimm B (2010) Mg protoporphyrin monomethylester cyclase deficiency and effects on tetrapyrrole metabolism in different light conditions. Plant Cell Physiol 51: 1229–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter E, Salinas A, Wallner T, Jeske D, Dienst D, Wilde A, Grimm B (2009) Differential requirement of two homologous proteins encoded by sll1214 and sll1874 for the reaction of Mg protoporphyrin monomethylester oxidative cyclase under aerobic and micro-oxic growth conditions. Biochim Biophys Acta 1787: 1458–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ, Thompson WA, Kriedemann PE (1989) Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 975: 384–394 [Google Scholar]

- Rast A, Heinz S, Nickelsen J (2015) Biogenesis of thylakoid membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1847: 821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai I, Hagio M, Gombos Z, Tyystjarvi T, Paakkarinen V, Aro EM, Wada H (2003) Requirement of phosphatidylglycerol for maintenance of photosynthetic machinery. Plant Physiol 133: 1376–1384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Suda K, Tsuzuki M (2004) Responsibility of phosphatidylglycerol for biogenesis of the PSI complex. Biochim Biophys Acta 1658: 235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottkowski M, Peters M, Zhan Y, Rifai O, Zhang Y, Zerges W (2012) Biogenic membranes of the chloroplast in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 19286–19291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka R. (2014) Making proteins green; biosynthesis of chlorophyll-binding proteins in cyanobacteria. Photosynth Res 119: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka R, Dühring U, Komenda J, Peter E, Gardian Z, Tichý M, Grimm B, Wilde A (2008a) Importance of the cyanobacterial Gun4 protein for chlorophyll metabolism and assembly of photosynthetic complexes. J Biol Chem 283: 25794–25802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka R, McLean S, Žuberová M, Hunter CN, Tichý M (2008b) The C-terminal extension of ferrochelatase is critical for enzyme activity and for functioning of the tetrapyrrole pathway in Synechocystis strain PCC 6803. J Bacteriol 190: 2086–2095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsui HC, Keen SK, Sham LT, Wayne KJ, Winkler ME (2011) Dynamic distribution of the SecA and SecY translocase subunits and septal localization of the HtrA surface chaperone/protease during Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 cell division. MBio 2: e00202-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavilin D, Brune DC, Vermaas W (2005) 15N-labeling to determine chlorophyll synthesis and degradation in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 strains lacking one or both photosystems. Biochim Biophys Acta 1708: 91–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavilin D, Vermaas W (2007) Continuous chlorophyll degradation accompanied by chlorophyllide and phytol reutilization for chlorophyll synthesis in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochim Biophys Acta 1767: 920–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Xu C, Benning C (2002) Arabidopsis disrupted in SQD2 encoding sulfolipid synthase is impaired in phosphate-limited growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 5732–5737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Paakkarinen V, Suorsa M, Aro EM (2001) A SecY homologue is involved in chloroplast-encoded D1 protein biogenesis. J Biol Chem 276: 37809–37814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]