Abstract

The ACA establishes “essential health benefits” (EHBs) as the coverage standard for health plans sold in the individual and small group markets, including the health insurance Marketplace. “Pediatric services” are a required EHB coverage class. However, other than oral health and vision care, neither the statute nor the implementing regulations define the term. This study aimed to determine how state benchmark plans address pediatric coverage in EHB-governed plans. Our review of state benchmark plan summaries for all 50 states and D.C. found that no state specified a distinct “pediatric services” benefit class. Furthermore, although benchmark plans explicitly included multiple pediatric conditions, many state benchmark plans also specifically excluded services for children with special health care needs. These findings suggest important policy directions in preparing for the 2016 plan year.

Keywords: Children's Health, Consumer Issues, Health Reform, Children Insurance Coverage

INTRODUCTION

The Affordable Care Act remakes the private insurance market through reforms that guarantee access to coverage, create health insurance marketplaces offering affordable coverage, and establish minimum coverage standards in the individual and small group markets. These standards, known as “Essential Health Benefits” (EHBs), consist of ten benefit classes (Exhibit 1) that must be covered to some degree in all non-grandfathered health insurance plans sold in the individual and small group markets. One of the enumerated EHB benefit classes is “pediatric services.” Congress expressly authorized the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement the EHB coverage standard, including the pediatric services benefit class. However, rather than establishing a detailed national EHB standard, HHS elected to use a “benchmark plan” approach comparable to that used under the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). This approach permits each state to select a “base” plan among various commercial plans sold in the state; HHS selects a state benchmark in states that elect not to choose their own.

Exhibit 1.

ACA's Essential Health Benefit Classes

| 1) Ambulatory patient services |

| 2) Emergency services |

| 3) Hospitalization |

| 4) Maternity and newborn care |

| 5) Mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment |

| 6) Prescription drugs |

| 7) Rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices |

| 8) Laboratory services |

| 9) Preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management |

| 10) Pediatric services, including oral and vision care |

Source: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Section 1302(b)(1).

The purpose of this study was to determine how state benchmark plan designs, adjusted in accordance with HHS directives, address pediatric coverage. We sought to determine whether state benchmark plans included a category for “pediatric services,” and whether certain pediatric treatments or conditions were included or excluded. The coverage of pediatric services is important because the EHB benchmark standard governs all non-grandfathered health plans sold in the individual and small group markets(1) (defined as 100 full-time employees or fewer), including health plans sold in the health insurance Marketplace, where premium subsidies and cost-sharing assistance also are available. Whether or not the EHB benchmark standards respond to children's needs has major implications for all U.S. children covered through non-grandfathered individual and small group health plans, as well as for children insured through CHIP, if Congress does not fund CHIP beyond the end of fiscal year (FY) 2015.

We begin this article with an overview of pediatric coverage under private health insurance. Following a brief review of the EHB standard and its implementation by HHS, we then present our study design and findings. We conclude with a discussion of our results and offer a series of policy options regarding pediatric coverage under EHB-governed health plans.

Defining Pediatric Coverage: A Historical Context

What “coverage” means under private health insurance historically has been left to the states, as part of their power to regulate insurance(2). Federal health care programs such as Medicaid and CHIP do establish minimum federal pediatric coverage standards. Medicaid's Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit for children up to age 21 is broad and detailed, focuses on pediatric principles, and includes a entitlement to treatment that is “medically necessary” as determined on a case-by-case basis(3). Simply put, it has no peer. CHIP, by contrast, gives states more flexibility to define “child health assistance” while establishing certain minimum expectations (such as well baby and well child care, immunizations, and oral health)(4). States may elect to create a “benchmark” plan that governs the sale of CHIP-sponsored plans. CHIP's pediatric-oriented benefit and network design, as well as low cost-sharing, have been viewed as contributing to its success as a child health policy(5, 6).

Where the private insurance market is concerned, however, states have acted virtually alone in setting pediatric coverage standards, using their authority to regulate the content of insurance. The federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), which governs nearly all private employer-sponsored health plans, historically contained virtually no substantive coverage requirements. However, beginning in the mid-1990s, Congress added certain content protections such as coverage of maternity and newborn hospital stays; most notably, lawmakers added mental health parity requirements in 1996, which were expanded in 2008(7). The ACA further amended ERISA coverage rules, extending the preventive benefit guarantee to all ERISA-governed health plans and the EHB coverage standard to all group health plans falling within its parameters(8) (100 full-time employees or fewer).

However, states continue to play the major role in the content of insurance design. As with adults, state benefit mandates improving coverage for children tend to emerge from advocacy efforts to improve coverage for distinct groups, an example of which might be strengthened coverage for children with autism under state benefit mandates. As a result, different states require coverage of different benefits, with no overarching national pediatric benefit standard. The National Association of Insurance Commissioners, a standard-setting body comprised of the nation's state insurance commissioners, has not recommended a national pediatric coverage standard. Nor has the federal government, as part of CHIP administration oversight, recommended a model approach to pediatric coverage for states that use CHIP funds to purchase private health plans for eligible children (a figure about which there is uncertainty). To provide a national standard for pediatric coverage, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has proposed a comprehensive approach to coverage that encompasses a broad range of preventive, medical, and remedial care for infants, children, adolescents, and young adults(9). The ACA's EHB statute, with its express “pediatric services” coverage class, represents an important federal policy development in standard-setting for children, adolescents, and young adults in the private health insurance market.

The EHB Coverage Standard Under the ACA

The EHB coverage standard, which includes pediatric services, contains several principal elements(10). First, the standard provides a list of broad benefit classes whose inclusion (at least to some extent) is mandatory (Exhibit 1). Second, the standard requires that the Secretary ensure that the scope of plans subject to the EHB standard is equal to the scope of a “typical” employer plan(11). Third, the standard establishes rules regarding actuarial value and cost-sharing. The actuarial value requirement is expressed as metal tiers, ranging from platinum (90 percent actuarial value), to gold (80 percent actuarial value), silver (70 percent actuarial value), and bronze (60 percent actuarial value), with a separate cost-sharing calculation for some silver plan participants(12).

One of the ten enumerated EHB benefit classes is “pediatric services, including oral and vision care”(13). For children, therefore, the EHB standard consists of the nine benefit classes available to the entire enrolled population, as well as a distinct, tenth class of “pediatric services.” This separate benefit class consists, at a minimum, of oral and vision care; however, the statute permits the HHS Secretary to interpret the class more expansively as signified by the insertion of “including” prior to “oral and vision care.”

In implementing the EHB statute, however, HHS elected not to adopt a single, comprehensive, preemptive federal standard, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM)(14). Instead, HHS utilized a variation of the CHIP benchmark strategy(15), allowing each state to select what the regulations call a “base” benchmark plan as the starting point for determining coverage under health plans governed by the EHB standard(10). The base benchmark plan provides a template for other health plans to follow, and is supposed to reflect a state's “typical” employer plan. Once the state base benchmark is selected (HHS selects a benchmark in states that opt out of selecting their own), states are expected to make adjustments as needed to ensure that all ten EHB benefit classes are reflected.

In the case of pediatric services, however, the HHS regulations require only that the base benchmark be adjusted to cover vision and oral health care, both explicitly listed in the statute; the regulations do not further define the meaning of “pediatric services.” The resulting adjusted benchmark governs all non-grandfathered health plans subject to the EHB standard and sold in a state, whether inside or outside the Marketplace. To supplement plan coverage to include pediatric oral and vision care, states have the option of choosing between the federal employee health benefit plan or their CHIP plans. Under the law, the premium and cost-sharing subsidies are tied to state benchmarks as they existed at the end of 2011. States could amplify on their adjusted benchmarks by adding in more required benefits, but to the extent they chose to do so, they would be 100 percent responsible for the cost of subsidizing these additional services for low- and moderate-income families purchasing coverage in the Marketplace.

METHODS

We utilized each state's EHB benchmark plan as identified by the Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight (CCIIO), the federal agency within HHS responsible for insurance regulation. As part of its oversight activities, CCIIO collects and creates summaries of each state EHB benchmark plan, as finalized(16). Although the actual filings with state Departments of Insurance are voluminous, the vast majority pertains to legal documents demonstrating compliance with insurance standards. On the actual details of coverage, insurance filings are sparse, sufficient to show compliance with applicable benefit mandates but general in nature. The CCIIO summaries are, in fact, the documents used to ensure compliance with federal EHB requirements, and represent the official public description of each state's coverage standards in the EHB market. The CCIIO benchmark plan summaries for all 50 states and the District of Columbia were reviewed for their applicability to pediatric services. We used the following inclusion criteria: 1) The existence of a distinct “pediatric services” category within the benchmark or any specific benefit inclusion for children or adolescents; and 2) Specific reference to or exclusion of benefits in relation to children or adolescents.

Authors at two different institutions abstracted data from CCIIO summaries independently. Results were then compared, with final decisions determined by consensus. Larger service categories were collapsed for ease of data presentation. For example, ABA therapy was recorded under the general “Autism spectrum disorder services” category. If coverage of an autism diagnosis or service was only covered in a state through a specific age (for example, 12 years of age), the state was recorded as both an inclusion (i.e., for 12 years and under) as well as an exclusion (i.e., for those over 12 years of age).

Of note, we did not review states’ pediatric prevention mandates, since coverage of preventive services that have received an A or B rating from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force or are included in evidence-informed preventive care and screening provided for in the comprehensive guidelines supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (Bright Futures) is already mandated under the ACA(17). Although patient cost-sharing (including out-of-pocket costs), as an element of actuarial value, is part of EHB design under the ACA statute, the state EHB summaries did not specify cost-sharing standards, an area in which insurers have been given broad design discretion under federal rules as long as they satisfy the applicable actuarial value test. As such, the particulars of cost-sharing arrangements under specific plans were not included in our study.

LIMITATIONS

Certain limitations in our study should be noted. The benchmark plan summaries on which these data were gleaned are indeed just summaries and not a comprehensive review of the content of benchmark plans(18). As such, they depend on the skill and consistency of their creators in abstracting the appropriate information from the actual benchmark plan documents for their summaries, which may not be comprehensive. However, we believe that they are the best publicly available source of data on benchmark and exchange plans for all 50 states, and they were also used as the data source for a recent report comparing CHIP and QHP benefits(19). Additionally, benchmark plans established in 2012, while serving as the basis for the current exchange plans, do not reflect the actual plans in the current marketplace starting in late 2013. Actual plans on the marketplace may thus be more comprehensive or exceed benefit limits at the insurer's option; however, they are not readily publicly available.

RESULTS

No state benchmark plan summary included a specific benefit category classified as “pediatric services,” despite the fact that “pediatric services” represents a specific EHB category. However, the benchmark plan summaries did reflect other EHB coverage categories. As in the final HHS regulations, the only pediatric categories expressly mentioned were oral and vision care.

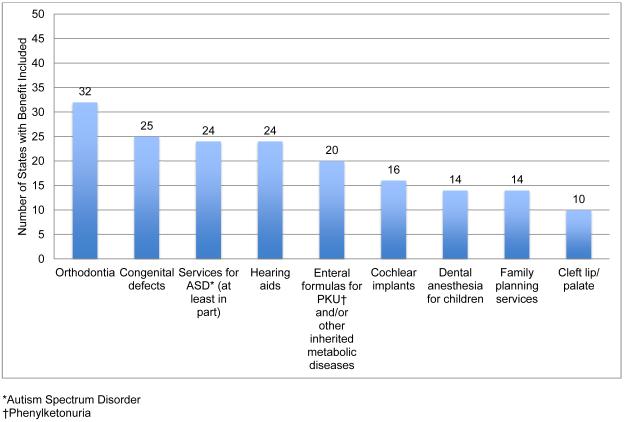

Exhibit 2 shows our results and displays the types of pediatric benefits that were most often explicitly included in benchmark plan summaries. (See Appendix 1 for a table with the most frequently included pediatric benefits by state(20)). With respect to the other nine population-wide benefit categories shown in Exhibit 1, our review did uncover numerous instances in which a particular treatment or service for children was explicitly mentioned. The most frequently included treatments and services outside of pediatric oral and vision care are shown by state in Exhibit 2. The most frequently cited treatment mandate was for orthodontia (32 states). Twenty-five states specifically require coverage of treatments for congenital defects. Twenty-four states specifically included both autism spectrum disorder (at least in part) and hearing aids. Other categories shown include enteral formulas for phenylketonuria and/or other inherited metabolic diseases, cochlear implants, dental anesthesia for children, family planning services/contraceptives, and cleft lip/palate services.

Exhibit 2.

Most frequently included pediatric benefits by number of states (excluding pediatric oral and vision care)

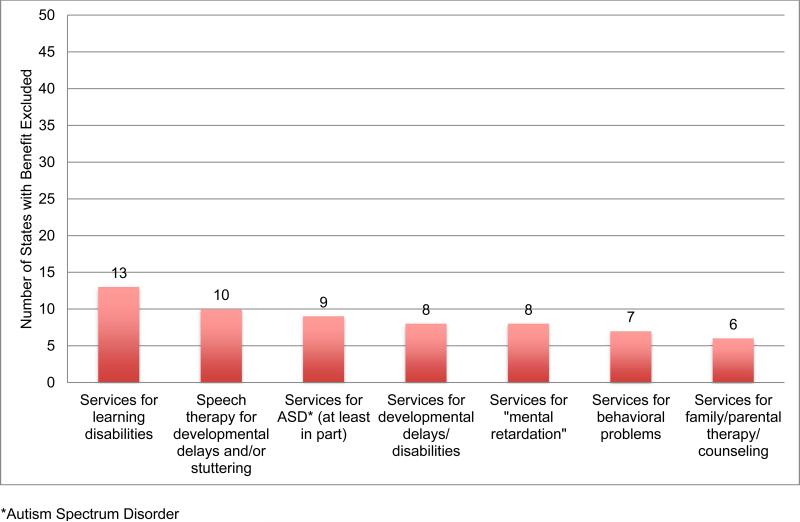

We also examined the population-wide EHB categories for possible pediatric exclusions (Exhibit 3, by number of states; Appendix 2, by state(20)). Children as a group were generally not excluded from these population-wide benefit categories. The two exceptions were for preventive screening services indicated for older adults, and certain specified treatments associated with adults under plan terms (e.g., biofeedback for urinary incontinence for adults 18 years and older only [Kansas]; chiropractic care limited to ages 16 and older only [Massachusetts]; infertility treatment for members ages 21 to 44 only [New York]; and tobacco use cessation services for members age 15 or older only [Oregon]).

Exhibit 3.

Most frequently excluded pediatric benefits by number of states

However, as Exhibit 3 demonstrates, we did find a number of specific pediatric exclusions within certain treatment categories. These exclusions typically appear to be associated with pediatric developmental and mental health conditions, and tend to cluster within certain benefit groups such as habilitative and therapy services (habilitative services are “health care services that help a person keep, learn, or improve skills and functioning for daily living”(21)). Thirteen states specifically exclude services for children with learning disabilities. Ten states exclude speech therapy for developmental delays and/or stuttering. Nine states at least partially exclude services for children with autism spectrum disorders, and eight states specifically exclude services for children with developmental delays/disabilities. Eight and seven states, respectively, specifically exclude one or more services for children with “mental retardation” or behavioral problems. Six state benchmarks expressly exclude family/parental therapy services.

DISCUSSION

Our findings, including the absence of a specific pediatric coverage category in benchmark plans and the presence of limitations and exclusions involving children, should not be surprising given the fact that prior to enactment of the ACA, “typical” employer plans (the starting point for the EHB package) did not contain a distinct pediatric coverage standard. Since the purpose of the federal benchmark rule was to identify what was “typical” in the small employer market for each state in 2011, one would not expect to find coverage categories that were not “typical” at that time. (The same is true for habilitative services, which were not typical in employer plans). Because HHS’ EHB rule used 2011 as the base benchmark year, and the agency's policy did not make its first appearance until a special bulletin was issued in December 2011(15), states effectively had no time to develop a newer variation of their benchmark plans that would more specifically address the needs of children. The evidence suggests that the typical employer plans of the time frequently excluded otherwise-covered treatments and services (e.g., physical and speech therapy) when the underlying diagnosis was a child's developmental disability(22).

As Congress debates on whether to extend funding for CHIP beyond the end of FY 2015, how well the pediatric services element of the EHB requirement addresses the needs of children will be an important factor under consideration. For the 8 million children insured through CHIP, continuing its protections is of great importance. If CHIP funding is not extended, however, many of these children would enter the Marketplace. Additionally, given that the EHB standard affects the entire non-grandfathered individual and small group insurance market (where many families above the CHIP threshold buy coverage), the appropriateness of the EHB standard for children is one of the most important issues in child health policy today.

Our findings suggest that EHB-governed coverage, as implemented under the HHS regulations, continues to be a patchwork containing notable exclusions for children, particularly those with special needs and disabilities. Although Exhibit 2 highlighted certain pediatric benefits that are expressly included in state benchmarks, these specific treatment requirements in all likelihood reflect important but isolated advocacy efforts. These efforts, while successful, do not negate other exclusions, nor do they reflect a systematic effort to ensure in all states that the range and scope of treatments within specified benefit classes are appropriate for children. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that states that expanded private insurance coverage for children after December 31, 2011 explicitly excluded qualified health plans sold in the Exchange from the reach of the expansion in order to avoid financial exposure under the federal EHB rules for additional subsidy costs related to expanded benefits post-2011(23).

In light of HHS’ stated commitment, in the EHB regulations, to review its approach for the 2016 plan year(15), our findings have implications for future HHS regulations regarding the EHB standard for pediatric services. Based on our analysis, the recommendations we identify below could – without overstepping commercial norms – result in a more robust pediatric benefit under the ACA, as originally intended.

1) Bar pediatric treatment limits and exclusions, particularly exclusions based on mental retardation, mental disability, or other developmental conditions

Whether the Secretary uses her authority to broaden the scope of coverage and improve the actuarial value of pediatric services, it is clear that benchmark plans include treatment limits and exclusions aimed specifically at children that must be addressed. These limits and exclusions do not appear in all plans, but the fact that certain exclusions were expressly found in some of the state benchmarks, but not in others, should not be taken to mean that they are rare. Unless state law expressly bars certain types of limits and exclusions, benchmark plans that are silent on the matter could be interpreted by insurers as permitting exclusionary practices, since silence in a regulated industry signals a decision to vest the industry with discretion over certain practices. Cases brought against insurers and health plans reveal the practice of limiting coverage for children with certain types of disabilities(24, 25). Many of these limits are aimed at children with disabilities related to mental health and development, raising separate questions under federal mental health parity law, which applies to health plans sold in state exchanges and bars both quantitative and non-quantitative treatment limits based on mental illness(22). Often, these types of exclusions aimed at children with developmental disabilities are hidden, buried in internal and proprietary treatment guidelines that plans apply when evaluating treatment requests involving children(24, 25).

Although some of these exclusions may be rationalized based on the fact that these services are offered in schools for children who qualify under the Individual with Disabilities Education Act, not all children who require these services need special education. Additionally, families and pediatricians may desire further psychoeducational testing or referral to providers not in the school context. The ACA indicates that, in defining the EHBs, the Secretary shall “not make coverage decisions, determine reimbursement rates, establish incentive programs, or design benefits in ways that discriminate against individuals because of their age, disability, or expected length of life”(26). Barring pediatric treatment limits and exclusions would certainly fit with the ACA's intent of non-discrimination in this regard.

2) Incorporate medical necessity concepts into a defined pediatric benefit

Issuers governed by the EHB benchmark could be directed to incorporate medical necessity concepts into their plans. These medical necessity concepts, in the case of children, consider not only the clinical utility and appropriateness of a covered service, but also whether the service is appropriate in a pediatric developmental health context - a more appropriate standard when judging the utility of treatments for children(27). As above, standards such as Medicaid's Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) program or the AAP's recommendations for a comprehensive pediatric benefit package(9) warrant consideration. The AAP policy statement states that covered services should include, among others, “standardized assessment and monitoring tools for identification, diagnosis, and monitoring of educational, developmental, behavioral, and mental health conditions” and “speech therapy services for children with speech delay”(9). The explicit exclusion of coverage for conditions that would be included under the AAP's policy statement is concerning. Without a federal child health benefit standard, the current system of pediatric coverage in the ACA's Marketplace is neither comprehensive nor consistent.

3) Revise the EHB standard to address both covered services and actuarial value

Under the ACA, the EHB standard is expressed in terms of both actuarial value and classes of services. As such, regulations implementing the pediatric benefit class should be able to address both considerations. With respect to cost-sharing, the Secretary could use her authority to expand pediatric benefits to not only augment the scope of coverage, but to set a higher actuarial value than that provided for adults. In keeping with current CHIP practice, we suggest an actuarial value of 90 percent, to reduce the burden of high deductibles and coinsurance and other forms of cost-sharing. The cost-sharing reduction assistance provided under the ACA ends at 250 percent of the federal poverty level, and for families with incomes over 200 percent of the poverty level, very little cost-sharing assistance is offered. One way to help these families would be to boost the value of coverage for their children.

With respect to covered benefits, the Secretary could use the pediatric coverage class to ensure that plans provide better coverage for children with special needs. For example, plans could be required to offer more robust care management programs for children with special needs, amplifying the fact that care management is already a covered EHB class. The Secretary could even consider requiring some level of home and community care, such as personal attendant and respite care. It is true that such services are not in existing “typical” employer plans, but both the pediatric benefit class and the habilitative benefit will have to result in new norms for commercial plans.

4) Permit CHIP plans to be used as a benchmark for pediatric services

Given the significant and historically positive impact of CHIP on pediatric coverage, HHS could give states the option to use their CHIP plans to develop a pediatric services benchmark (assuming that a state's CHIP plan, in addition to offering greater actuarial value, also addresses all EHB classes). In many cases, CHIP is simply coterminous with Medicaid, since states have used some or all of their CHIP allotments to expand pediatric Medicaid coverage. However, in other states, CHIP is expressed as a child health benchmark for private plans.

CONCLUSION

The ACA has important benefits for children, and significant opportunities that have not yet been fully realized. The statute afforded HHS the ability to robustly define a pediatric benefit standard at the national level. Instead, HHS chose a state-by-state benchmark plan approach affording greater discretion to both states and payers. The result, according to our study, is a state-by-state patchwork of coverage for children and adolescents, with significant exclusions, particularly for children with developmental disabilities and other special health care needs. These findings demonstrate a missed opportunity by HHS to strengthen pediatric benefits under the ACA's EHB requirement. As HHS revisits the EHB standards over the next year, it is critical to improve the EHB regulations for pediatric services more broadly. HHS could revise the EHB standard to address both covered services and actuarial value; bar pediatric treatment limits and exclusions, particularly exclusions based on mental retardation, mental disability, or other developmental conditions; incorporate medical necessity concepts into a defined pediatric benefit; and permit CHIP plans to be used as a benchmark for pediatric services.

Appendix

APPENDIX 1.

MOST FREQUENTLY INCLUDED PEDIATRIC BENEFITS BY STATE (excluding Pediatric Oral and Vision Care)

| STATE | BENEFIT INCLUDED? | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodontia | Congenital defects | Autism spectrum disorder services (at least in part) | Hearing aids | Enteral formulas for PKU and/or other inherited metabolic diseases | Cochlear implants | Dental anesthesia for children | Family planning services | Cleft lip/palate | |

| Alabama | √ | ||||||||

| Alaska | √ | ||||||||

| Arizona | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Arkansas | √ | √ | |||||||

| California | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Colorado | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Connecticut | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Delaware | √ | √ | |||||||

| District of Columbia | |||||||||

| Florida | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Georgia | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Hawaii | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Idaho | √ | ||||||||

| Illinois | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Indiana | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Iowa | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Kansas | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Kentucky | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Louisiana | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Maine | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Maryland | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Massachusetts | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Michigan | |||||||||

| Minnesota | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Mississippi | √ | ||||||||

| Missouri | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Montana | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Nebraska | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Nevada | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| New Hampshire | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| New Jersey | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| New Mexico | √ | ||||||||

| New York | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| North Carolina | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| North Dakota | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Ohio | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Oklahoma | √ | √ | |||||||

| Oregon | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Pennsylvania | √ | √ | |||||||

| Rhode Island | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| South Carolina | √ | √ | |||||||

| South Dakota | |||||||||

| Tennessee | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Texas | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Utah | √ | ||||||||

| Vermont | √ | √ | |||||||

| Virginia | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Washington | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| West Virginia | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Wisconsin | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Wyoming | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| TOTAL | 32 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 10 |

APPENDIX 2.

MOST FREQUENTLY EXCLUDED PEDIATRIC BENEFITS BY STATE

| STATE | BENEFIT EXCLUDED? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Services for learning disabilities | Speech therapy for developmental delays and/or stuttering | Services for autism spectrum disorders (at least in part) | Services for developmental delays/disabilities | Services for “mental retardation” | Services for behavioral problems | Services for family/ parental therapy/counseling | |

| Alabama | |||||||

| Alaska | √ | ||||||

| Arizona | |||||||

| Arkansas | |||||||

| California | |||||||

| Colorado | |||||||

| Connecticut | √ | ||||||

| Delaware | |||||||

| District of Columbia | |||||||

| Florida | √ | √ | |||||

| Georgia | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Hawaii | |||||||

| Idaho | |||||||

| Illinois | √ | √ | |||||

| Indiana | √ | ||||||

| Iowa | √ | √ | |||||

| Kansas | |||||||

| Kentucky | √ | ||||||

| Louisiana | √ | √ | |||||

| Maine | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Maryland | √ | √ | |||||

| Massachusetts | |||||||

| Michigan | |||||||

| Minnesota | |||||||

| Mississippi | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Missouri | √ | ||||||

| Montana | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Nebraska | |||||||

| Nevada | |||||||

| New Hampshire | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| New Jersey | |||||||

| New Mexico | |||||||

| New York | |||||||

| North Carolina | √ | ||||||

| North Dakota | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Ohio | √ | ||||||

| Oklahoma | |||||||

| Oregon | √ | √ | |||||

| Pennsylvania | |||||||

| Rhode Island | √ | √ | |||||

| South Carolina | |||||||

| South Dakota | |||||||

| Tennessee | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Texas | √ | ||||||

| Utah | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Vermont | √ | ||||||

| Virginia | √ | ||||||

| Washington | |||||||

| West Virginia | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Wisconsin | √ | ||||||

| Wyoming | √ | ||||||

| TOTAL | 13 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

REFERENCES

- 1.42 U.S. Code, Section 300gg–6.

- 2.McCarran-Ferguson Act (15 U.S.C.A. Section 1011 et seq.), 1945.

- 3.Rosenbaum S, Wise PH. Crossing the Medicaid-Private Insurance Divide: The Case of EPSDT. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):382–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.42 U.S. Code, Section 1397cc(c).

- 5.Cardwell A, Jee J, Hess C, Touschner J, Heberlein M, Alker J. Benefits and Cost Sharing in Separate CHIP Programs. National Academy for State Health Policy and Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families; Washington, D.C.: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus P. A Comparative Review of Essential Health Benefits Pertinent to Children in Large Federal, State, and Small Group Health Insurance Plans: Implications for Selecting State Benchmark Plans. American Academy of Pediatrics; Elk Grove, IL: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wellstone Paul, Domenici Pete. Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. 2008 Sections 511 and 512 of the Tax Extenders and Alternative Minimum Tax Relief Act (Division C, Pub. L. 110-343)

- 8.Public Health Service Act, Section 2707, added by PPACA Section 1201.

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics' Committee on Child Health Financing Scope of Health Care Benefits for Children From Birth Through Age 26. Pediatrics. 2012 Jan;129(1):185–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010 Section 1302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.42 U.S. Code, Section 18022(b)(2).

- 12.42 U.S. Code, Section 18022(d).

- 13.42 U.S. Code, Section 18022(b)(1)(J).

- 14.Institute of Medicine . Essential Health Benefits: Balancing Coverage and Cost. Institute of Medicine; Washington, D.C.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight Essential Health Benefits Bulletin. 2011 Dec 16; [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight . Additional Information on Proposed State Essential Health Benefits Benchmark Plans. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [2014 August 25]. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Data-Resources/ehb.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.42 U.S. Code, Section 300gg–13(a).

- 18.Staff of Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight) Personal e-mail communication. 2014 Jan 15; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakeley Consulting Group . Comparison of Benefits and Cost Sharing in Children's Health insurance Programs to Qualified Health Plans. Wakely Consulting Group; Englewood, CO: Jul, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.See Appendix.

- 21.Rosenbaum S. Habilitative Services Coverage for Children Under the Essential Health Benefit Provisions of the Affordable Care Act. Lucile Packard Foundation for Children's Health: Issue Brief. 2013 May; [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum S FD, Law SA, Rosenblatt RE. Law and the American Health Care System. 2nd Ed. Foundation Press; St. Paul, MN: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews M. Health Law Tempers New State Coverage Mandates. [September 20, 2014];Kaiser Health News [Internet] September 16. 2014 [about 1 p.]. Available from: http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2014/September/16/Health-Law-Tempers-New-State-Coverage-Mandates.aspx.

- 24.Bedrick v. Travelers 93 F.3d 149, (1996).

- 25.Mondry v. Am. Family Mut. Ins. Co., 557 F.3d 781 (7th Cir. 2008), cert. denied, 130 S. Ct. 200, (2009).

- 26.42 U.S. Code, Section 1302(b)(4)(B).

- 27.Halfon N, DuPlessis H, Inkelas M. Transforming the U.S. Child Health System. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):315–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]