Abstract

Klotho, a cofactor in suppressing 1,25(OH)2D3 formation, is a powerful regulator of mineral metabolism. Klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl) exhibit excessive plasma 1,25(OH)2D3, Ca2+, and phosphate concentrations, severe tissue calcification, volume depletion with hyperaldosteronism, and early death. Calcification is paralleled by overexpression of osteoinductive transcription factor Runx2/Cbfa1, Alpl, and senescence-associated molecules Tgfb1, Pai-1, p21, and Glb1. Here, we show that NH4Cl treatment in drinking water (0.28 M) prevented soft tissue and vascular calcification and increased the life span of kl/kl mice >12-fold in males and >4-fold in females without significantly affecting extracellular pH or plasma concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3, Ca2+, and phosphate. NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased plasma aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone concentrations and reversed the increase of Runx2/Cbfa1, Alpl, Tgfb1, Pai-1, p21, and Glb1 expression in aorta of kl/kl mice. Similarly, in primary human aortic smooth muscle cells (HAoSMCs), NH4Cl treatment reduced phosphate-induced mRNA expression of RUNX2/CBFA1, ALPL, and senescence-associated molecules. In both kl/kl mice and phosphate-treated HAoSMCs, levels of osmosensitive transcription factor NFAT5 and NFAT5-downstream mediator SOX9 were higher than in controls and decreased after NH4Cl treatment. Overexpression of NFAT5 in HAoSMCs mimicked the effect of phosphate and abrogated the effect of NH4Cl on SOX9, RUNX2/CBFA1, and ALPL mRNA expression. TGFB1 treatment of HAoSMCs upregulated NFAT5 expression and prevented the decrease of phosphate-induced NFAT5 expression after NH4Cl treatment. In conclusion, NH4Cl treatment prevents tissue calcification, reduces vascular senescence, and extends survival of klotho-hypomorphic mice. The effects of NH4Cl on vascular osteoinduction involve decrease of TGFB1 and inhibition of NFAT5-dependent osteochondrogenic signaling.

Keywords: CKD, mineral metabolism, vascular calcification, aldosterone

Klotho is expressed mainly in the kidney, parathyroid glands, and choroid plexus.1 The extracellular domain of the transmembrane protein may be cleaved off and released into blood or cerebrospinal fluid.1 Klotho participates in the inhibition of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-α-hydroxylase and thus limits the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3).1 Moreover, klotho influences the mineral metabolism more directly by upregulating the renal epithelial Ca2+ channel2 and downregulating renal tubular phosphate transport.3 Klotho further stimulates Na+/K+-ATPase activity1 and lack of klotho leads to extracellular volume depletion with secondary increase of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and aldosterone release.4 Klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl) carrying a disruption in the promoter sequence of the klotho gene suffer from severe tissue calcification, as well as a wide variety of age-related disorders. Accordingly, the life span is severely reduced in klotho-hypomorphic mice1,5 and is substantially increased in mice overexpressing klotho.6 Klotho has similarly been suggested as a factor influencing the life span of humans.7

Vascular calcification is a major pathophysiologic mechanism limiting the life span of patients with CKD.8 Mineral bone disorder is closely associated with survival of patients with CKD, which is determined by vascular calcification.9 In patients with CKD, the impaired phosphate excretion is compounded by decreased klotho levels.10 Along those lines, a klotho gene variant is associated with survival in dialysis patients.11

Vascular calcification is a complex active process12 involving transition of vascular smooth muscle cells into an osteogenic and chondrogenic phenotype.13 Reprogramming of vascular cells into osteogenic phenotypes is triggered by increased extracellular phosphate concentrations.14 The excessive tissue calcification of kl/kl mice and patients with CKD is associated with osteogenic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells as well as increased expression of the osteogenic transcription factor Core binding factor α-1 (Cbfa1), which triggers transformation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblast- and chondroblast-like cells.1,15 Cbfa1 stimulates the expression of alkaline phosphatase,1,16,17 which fosters calcification by degradation of the inhibitor pyrophosphate.18,19 Osteoinductive reprogramming of vascular smooth muscle cells is stimulated by aldosterone and fostered by hyperaldosteronism of kl/kl mice.16 Phosphate-induced osteoinductive reprogramming is closely intertwined with cellular senescence.20,21 Along those lines, klotho deficiency fosters cellular senescence and Tnfα-induced senescence can be countered by klotho supplementation.22,23 CKD is similarly associated with cellular senescence, which contributes to vascular calcification in CKD.21,24

Acidosis is a common complication in klotho-hypomorphic mice and patients with CKD.25,26 The pH is a major determinant of the solubility of hydroxyapatite and low pH prevents the precipitation of calcium and phosphate by increasing their solubility.27 Moreover, acidosis decreases calcification by downregulation of the type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporter Pit1.27–29 Renal tubular phosphate transport is decreased by acidosis and, at least in theory, acidosis could foster renal phosphate elimination,30 thus counteracting hyperphosphatemia and calcification. However, acidosis has previously been shown to increase plasma phosphate concentration.31 Conflicting observations have been reported on the effect of acidosis on chronic renal disease. On the one hand, metabolic acidosis has been reported to slow the progression of renal disease in rats.28,32,33 On the other hand, acidosis has been shown to worsen experimental CKD,34–37 especially cystic kidney disease.38 Moreover, administration of alkali retards the progression of CKD in rodents.34–37 In humans with CKD, acidosis is associated with worse kidney function, whereas the administration of bicarbonate, as shown in several studies, is associated with the slowing of progressive kidney disease.37,39

Acidosis can be induced by dietary NH4Cl.40,41 NH4+ may further dissociate to H+ and NH3, which easily crosses membranes, thus entering cells and cellular compartments.42 In acidic compartments, NH3 binds H+ and is thus trapped as NH4+.43 As a result, NH4Cl alkalinizes acidic cellular compartments44 and swells cells.45–47 Cell swelling downregulates the cell volume–sensitive transcription factor Tonicity-Responsive Enhancer Binding Protein or nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT5),48,49 which has been implicated in the regulation of Cbfa1 expression, a function involving the transcription factor Sox9.50 Beyond that, lysosomal alkalinization prevents maturation of several proteins including TGFB1,51 which in turn is known to upregulate NFAT552 and participate in osteogenic signaling.53–56

This study explored the effect of NH4Cl treatment on the phenotype of klotho-hypomorphic mice.

Results

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Phenotype, Body Weight, and Survival of kl/kl Mice

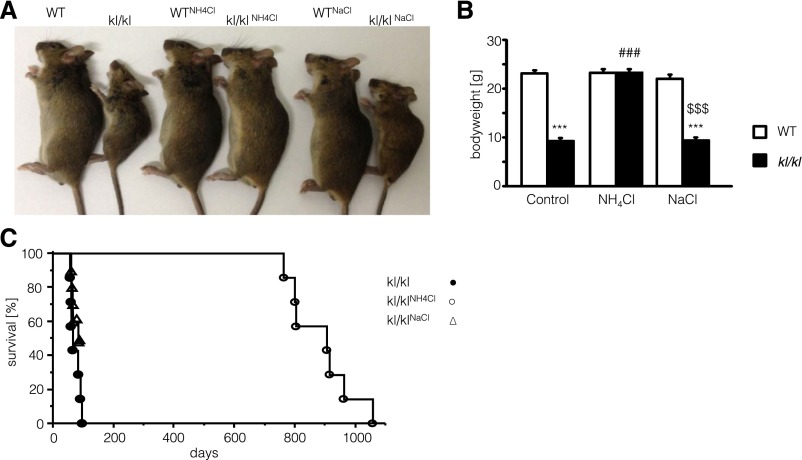

As illustrated in Figure 1A, klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl) suffer from a severe growth deficit compared with corresponding wild-type mice. The body weight of kl/kl mice was significantly lower than the body weight of wild-type mice (Figure 1B). After NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water), the body weight of kl/kl mice was significantly increased, approaching the body weight of wild-type mice. Applying an equimolar dose of NaCl (0.28 M in tap water) did not significantly modify the body weight of kl/kl mice. NH4Cl treatment further influenced the survival of kl/kl mice (Figure 1C). Whereas none of the untreated male kl/kl mice survived >95 days, all treated male kl/kl mice survived >729 days. Similarly, NH4Cl treatment increased the average life span of female kl/kl mice significantly from 84±4 days (n=9) to 355±46 days (n=7). Male kl/kl mice even regained fertility after NH4Cl treatment (Table 1). Treatment with NaCl (0.28 M in tap water) instead of NH4Cl had only a modest effect on the lifespan of kl/kl mice. After 87 days of NaCl treatment, four of nine animals survived.

Figure 1.

Effect of NH4Cl and NaCl treatment on body weight and survival of kl/kl mice. (A) Photograph of wild-type mice (WT) as well as klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl) without treatment (left), with NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water) (middle), and with NaCl treatment (0.28 M in tap water) (right). (B) Arithmetic means±SEM of body weight (n=8–9) of wild-type mice (white bars) and klotho-hypomorphic mice (black bars) without treatment (control, left bars), with NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water) (NH4Cl, middle bars), and with NaCl treatment (0.28 M in tap water) (NaCl, right bars). ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from respective wild-type mice; ###P<0.001, statistically significant differences from respective untreated mice; $$$P<0.001, statistically significant differences from respective NH4Cl-treated mice. (C) Percentage of surviving male klotho-hypomorphic mice maintained on control diet without treatment (closed circles), with NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water, open circles), and with NaCl treatment (0.28 M in tap water, open triangles) as a function of age. Survival of kl/kl mice is significantly extended by NH4Cl treatment (log-rank, Wilcoxon; P<0.001; n=7–9).

Table 1.

NH4Cl treatment restores fertility of male kl/kl mice

| Parameter | H2O | NH4Cl | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♂ +/hm | ♂ hm/hm | ♂ +/hm | ♂ hm/hm | |

| Offspring number | 20.4±1.9 | 0 | 20.6±1.5 | 21.2±1.2 |

Data are presented as the average number of puppies (±SD) born from six to eight breedings with three heterozygous female mice (+/hm) and either heterozygous male mice (+/hm) or hypomorphic male mice (hm/hm) drinking plain tap water (H2O) or an aqueous 0.28 M NH4Cl solution (NH4Cl).

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Plasma NH3, CaHPO4, and Hormone Concentrations

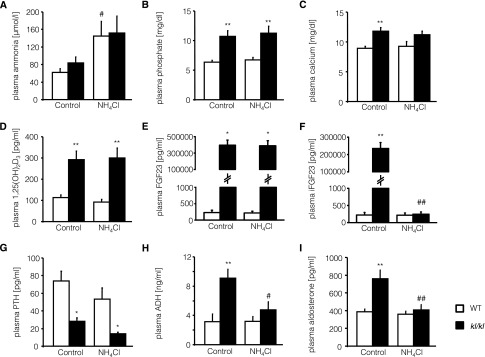

Plasma ammonia concentration tended to be slightly higher in untreated kl/kl mice than in untreated wild-type mice; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2A). Treatment with NH4Cl increased plasma ammonia concentration in both wild-type and kl/kl mice. Plasma phosphate (Figure 2B) and Ca2+ (Figure 2C) concentrations were significantly higher in kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice, whereby the differences were not significantly affected by treatment with NH4Cl. Similarly, plasma 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figure 2D) concentration was significantly higher in kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice, a difference that again was not significantly affected by NH4Cl treatment. C-terminal fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) (Figure 2E) and intact FGF23 (Figure 2F) were significantly higher in in kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased only plasma levels of intact FGF23 (Figure 2F). Plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) concentrations were significantly lower in kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice (Figure 2G). NH4Cl treatment tended to decrease the PTH levels in both genotypes; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Plasma ADH (Figure 2H) and aldosterone (Figure 2I) concentrations were both significantly higher in kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased the plasma ADH (Figure 2H) and aldosterone (Figure 2I) concentrations in kl/kl mice but not in wild-type mice. Accordingly, after NH4Cl treatment, plasma ADH (Figure 2H) and aldosterone (Figure 2I) concentrations were similar in kl/kl mice and wild-type mice (Figure 2, H and I).

Figure 2.

Plasma NH4+, phosphate, Ca2+, 1,25(OH)2D3, FGF23, intact FGF23 (iFGF23), PTH, ADH, and aldosterone concentrations of wild-type mice and kl/kl mice with or without NH4Cl treatment. Arithmetic means±SEM (n=5–8) of plasma ammonia (A), phosphate (B), Ca2+ (C), 1,25(OH)2D3 (D), FGF23 (C-Term) (E), intact FGF23 (F), PTH (G), ADH (H), and aldosterone (I) concentrations of wild-type mice (WT, white bars) and klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl, black bars) without (control, left bars) and with (NH4Cl, right bars) NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, statistically significant differences from respective wild-type mice; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01, statistically significant differences from respective untreated mice.

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Acid/Base Parameters and Plasma Electrolyte Concentrations

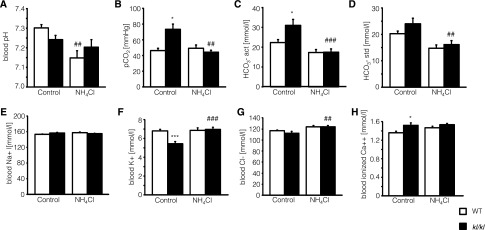

As shown in Figure 3, blood pH is lower in untreated kl/kl mice than in untreated wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased blood pH levels in wild-type mice (Figure 3A) but only tended to decrease blood pH levels in kl/kl mice (Figure 3A). Blood pCO2 values were significantly increased in kl/kl mice but decreased to normal values under treatment with NH4Cl (Figure 3B). Plasma HCO3− levels were significantly higher in untreated kl/kl mice than in untreated wild-type mice, a difference that again was reversed by NH4Cl treatment (Figure 3, C and D). There were no differences in blood Na+ levels among the different groups (Figure 3E), but plasma K+ levels were significantly lower in untreated kl/kl mice than in untreated wild-type mice. When treated with NH4Cl, K+ levels significantly increased in kl/kl mice but not in wild-type mice (Figure 3F). Blood Cl− levels also increased in both genotypes after NH4Cl treatment; however, the effect reached statistical significance only in kl/kl mice (Figure 3G). Blood ionized Ca2+ was significantly higher in untreated kl/kl mice than in untreated wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment did not significantly modify blood ionized Ca2+ in kl/kl mice or wild-type mice (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Blood pH, pCO2, actual HCO3−, standardized HCO3−, Na+, K+, Cl−, and ionized Ca2+concentrations of wild-type mice and kl/kl mice with or without NH4Cl treatment. Arithmetic means±SEM (n=10) of blood pH (A), pCO2 (B), actual HCO3− (C), and HCO3− standardized to normal CO2 (D), Na+ (E), K+ (F), Cl− (G), and Ca2+ (H) concentrations of wild-type mice (WT, white bars) and klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl, black bars) without (control, left bars) and with (NH4Cl, right bars) NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from respective wild-type mice; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0,001, statistically significant differences from respective untreated mice.

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Tissue Calcification of kl/kl Mice

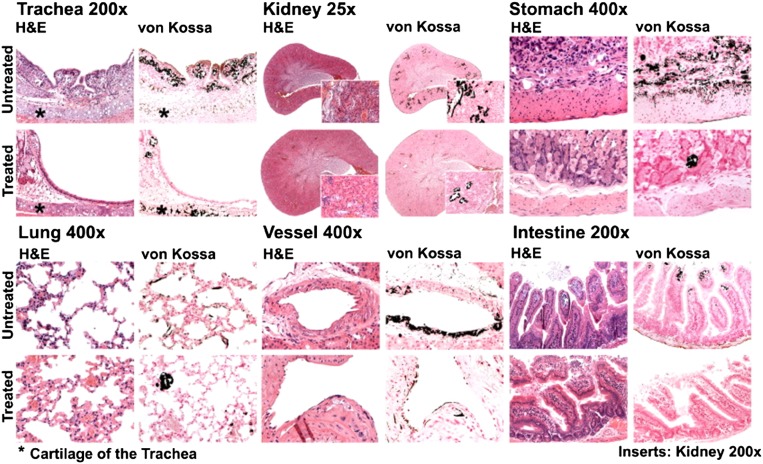

To further define the mechanisms contributing to or accounting for the effects of NH4Cl on survival of kl/kl mice, tissues from untreated and NH4Cl-treated kl/kl mice were subjected to histologic analysis. As illustrated in Figure 4, extensive calcifications were observed in trachea, lung, kidney, stomach, intestine, and vascular tissue of kl/kl mice. NH4Cl treatment strongly reduced the tissue calcification of kl/kl mice.

Figure 4.

NH4Cl treatment counteracts soft tissue calcification in kl/kl mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and von Kossa staining of trachea, lung, kidney, gastric tissue, and vascular tissue from klotho-hypomorphic mice without (untreated, upper panel) and with (treated, lower panel) NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water). The results are representative for three kl/kl mice per group.

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Procalcification Reprogramming in Aortic Tissues of kl/kl Mice

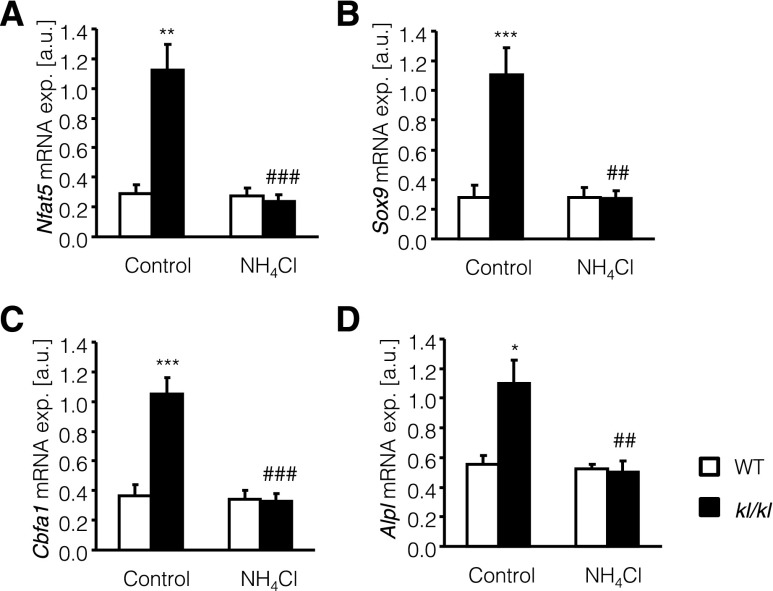

NH4Cl treatment could have reduced vascular calcification in kl/kl mice by inhibition of the active procalcification reprogramming in vascular tissue. As illustrated in Figure 5, the transcript levels of osteogenic transcription factor Cbfa1 and of alkaline phosphatase (Alpl) were significantly higher in aortic tissue of kl/kl mice than in aortic tissue of wild-type mice, differences that were significantly blunted by NH4Cl treatment (Figure 5, C and D). The alterations of Cbfa1 and Alpl transcript levels were paralleled by similar alterations of Nfat5 and of Sox9 transcript levels, which were significantly higher in aortic tissue from kl/kl mice than in aortic tissue from wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment again decreased Nfat5 and Sox9 transcript levels in aortic tissue of kl/kl mice (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

NH4Cl interferes with aortic osteoinductive signaling in kl/kl mice. Arithmetic means±SEM (n=10; arbitrary units [a.u.]) of Nfat5 (A), Sox9 (B), Cbfa1 (C), and Alpl (D) relative mRNA expression (exp.) in aortic tissue of wild-type mice (WT, white bars) and klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl, black bars), without (control, left bars) and with (NH4Cl, right bars) NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from respective wild-type mice; ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 indicate statistically significant differences from respective untreated mice.

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Phosphate-Induced Osteoinductive Signaling in Primary Human Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells

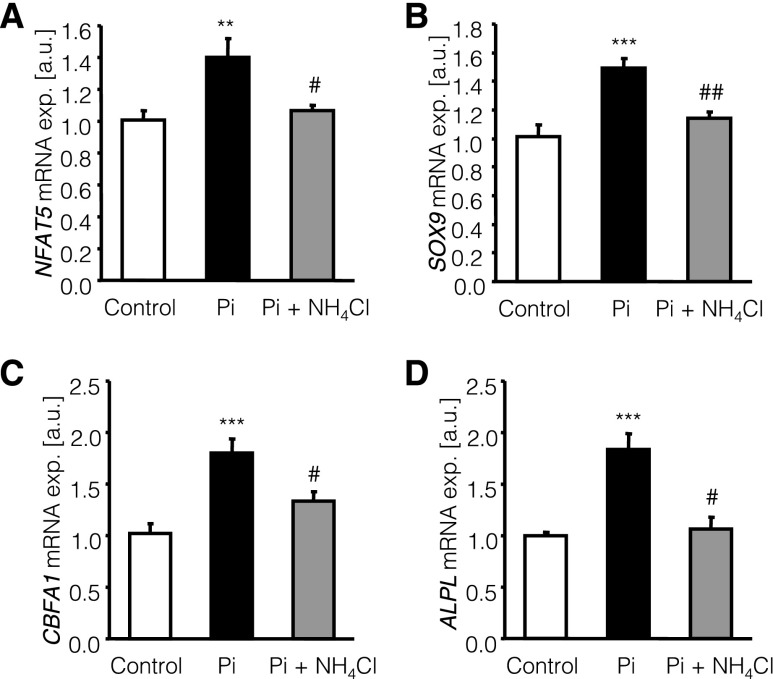

To further define the effects of NH4Cl on phosphate-induced osteoinductive signaling, primary human aortic smooth muscle cells (HAoSMCs) were treated for 24 hours with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate with or without additional cotreatment with 500 µM NH4Cl. Treatment of HAoSMCs with β-glycerophosphate significantly increased NFAT5, SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL mRNA expression (Figure 6), effects that were significantly suppressed by cotreatment with NH4Cl.

Figure 6.

NH4Cl interferes with phosphate-induced osteoinductive signaling in HAoSMCs. Arithmetic means±SEM (n=6–8; arbitrary units [a.u.]) of NFAT5 (A), SOX9 (B), CBFA1 (C), and ALPL (D) relative mRNA expression (exp.) in untreated HAoSMCs (control, white bars) and in HAoSMCs after 24 hours of treatment with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone (Pi, black bars) or with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and 500 µM NH4Cl (Pi+NH4Cl gray bars). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from untreated HAoSMCs; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01, statistically significant difference from HAoSMCs treated with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone.

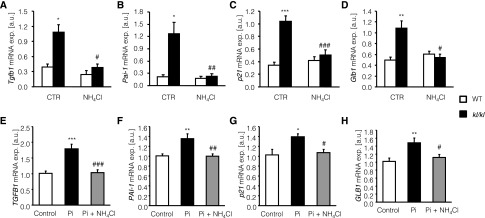

Effect of NH4Cl Treatment on Vascular Senescence in kl/kl Mice and in HAoSMCs

Because vascular calcification is fostered by cellular senescence of vascular smooth muscle cells, the senescence-associated molecules Tgfb1, Pai-1, p21, and SA-β-galactosidase (Glb1) were measured in aortic tissue of kl/kl mice and in HAoSMCs. As illustrated in Figure 7, A–D, the transcript levels of Tgfb1, Pai-1, p21, and Glb1 were significantly higher in aortic tissue of kl/kl mice than in aortic tissue of wild-type mice. NH4Cl treatment significantly suppressed the expression of Tgfb1, Pai-1, p21, and Glb1 in the aortic tissue of kl/kl mice and virtually abrogated the differences in aortic senescence-associated molecules transcript levels between kl/kl mice and wild-type mice. In HAoSMCs, phosphate treatment induced the mRNA expression of TGFB1, PAI-1, P21, and GLB1 (Figure 7, E–H), effects again reversed by cotreatment with NH4Cl.

Figure 7.

NH4Cl interferes with vascular senescence in kl/kl mice and in phosphate-treated HAoSMCs. (A–D) Arithmetic means±SEM (n=10; arbitrary units [a.u.]) of Tgfb1 (A), Pai-1 (B), p21 (C), and Glb1 (D) relative mRNA expression (exp.) in aortic tissue of wild-type mice (WT, white bars) and klotho-hypomorphic mice (kl/kl, black bars) without (control [CTR], left bars) or with (NH4Cl, right bars) NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001, statistically significant difference from respective wild-type mice; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, and ###P<0.001, statistically significant difference respective untreated mice. (E–H) Arithmetic means±SEM (n=6; arbitrary units) of TGFB1 (E), PAI-1 (F), p21 (G), and GLB1 (H) relative mRNA expression in untreated HAoSMCs (control, white bars) and in HAoSMCs after 24 hours of treatment with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone (Pi, black bars) or with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and 500 µM NH4Cl (Pi+NH4Cl, gray bars). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from untreated HAoSMCs; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, and ###P<0.001, statistically significant differences from HAoSMCs treated with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone.

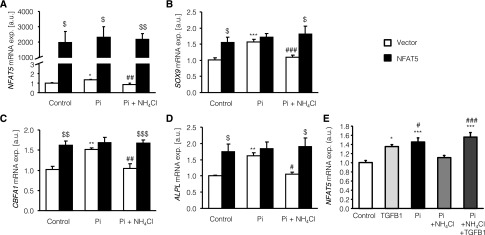

Effect of NFAT5 Overexpression on Osteoinductive Signaling and Effect of TGFB1 on NFAT5 Expression in HAoSMCs

Additional experiments were performed to test whether the regulation of SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL transcript levels is sensitive to NFAT5 in HAoSMCs. To this end, HAoSMCs were transfected for 48 hours with a construct encoding NFAT5 with or without subsequent treatment with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and/or 500 µM NH4Cl for 24 hours. Transfection efficiency was verified by quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 8A). As illustrated in Figure 8, B–D, overexpression of NFAT5 in HAoSMCs was followed by marked and significant increase of SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL mRNA levels. In empty vector–transfected HAoSMCs, the mRNA levels of SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL were increased after treatment with β-glycerophosphate to similarly high levels as in NFAT5-overexpressing HAoSMCs (Figure 8, B–D), an effect completely reversed by additional treatment with NH4Cl. By contrast, neither β-glycerophosphate nor NH4Cl significantly modified the transcript levels of SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL in NFAT5-overexpressing HAoSMCs. Accordingly, in the absence of β-glycerophosphate and in the presence of both β-glycerophosphate and NH4Cl, the SOX9, CBFA1, and ALPL transcript levels were significantly higher in NFAT5-transfected HAoSMCs than in empty vector–transfected HAoSMCs.

Figure 8.

The effect of phosphate-induced osteoinductive signaling is mimicked and the effect of NH4Cl is blunted by NFAT5 overexpression in HAoSMCs. (A–D) Arithmetic means±SEM (n=6; arbitrary units [a.u.]) of NFAT5 (A), SOX9 (B), CBFA1 (C), and ALPL (D) relative mRNA expression in HAoSMCs transfected for 48 hours with empty vector (white bar) or with a construct encoding human NFAT5 (black bar) without (control) or with treatment for 24 hours with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone (Pi) or with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and 500 µM NH4Cl (Pi+NH4Cl). *P<0.01, **P<0.01, and ***P<0.001, indicates statistically significant differences from empty vector–transfected untreated HAoSMCs (ANOVA); #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001, statistically significant difference from empty vector–transfected HAoSMCs treated with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone (ANOVA); $P<0.05, $$P<0.01, and $$$P<0.001, statistically significant difference from respective empty vector–transfected HAoSMCs (t test). (E) Arithmetic means±SEM (n=6; arbitrary units) of NFAT5 relative mRNA expression in untreated HAoSMCs (control) and in HAoSMCs after 24 hours of treatment with 10 ng/ml of human TGFB1 alone, with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate alone (Pi), with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and 500 µM NH4Cl (Pi+NH4Cl) and with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 500 µM NH4Cl, and 10 ng/ml of human TGFB1 (Pi+NH4Cl+TGFB1). *P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, statistically significant differences from untreated HAoSMCs (ANOVA); #P<0.05 and ###P<0.001, statistically significant differences from HAoSMCs treated with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate and 500 μM NH4Cl (ANOVA).

In a further series of experiments, the influence of TGFB1 on NFAT5 mRNA expression in HAoSMCs was tested. Treatment of HAoSMCs for 24 hours with 10 ng/ml of human TGFB1 significantly increased NFAT5 relative mRNA expression to similarly high values as treatment with β-glycerophosphate (Figure 8E). NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased NFAT5 mRNA expression in HAoSMCs treated with β-glycerophosphate, an effect completely abrogated by additional treatment with TGFB1 (Figure 8E).

Renal Function

Average kidney weight was 5.8±0.2 mg/g body wt in untreated wild-type mice and 5.7±0.2 mg/g body wt in untreated kl/kl mice. NH4Cl treatment increased the kidney mass significantly (P<0.001) to 7.1±0.2 mg/g body w in wild-type mice and to 7.0±0.1 mg/g body wt in kl/kl mice. Before and after NH4Cl treatment the ratio of kidney mass-to-body weight was similar in wild-type mice and kl/kl mice. Measurements in metabolic cages were performed in wild-type mice, NH4Cl-treated wild-type mice, and NH4Cl-treated kl/kl mice. Because untreated kl/kl mice do not tolerate this procedure, the treatment was stopped at the age of 7 weeks in a fourth group of NH4Cl-treated kl/kl mice. After a 3-week washout phase, the animals were housed in the metabolic cages. According to the measurements (Supplemental Figures 1–3), body weight, food and fluid intake, urinary volume and pH, fecal mass, plasma creatinine concentration, creatinine excretion, creatinine clearance, plasma protein, plasma albumin, urinary albumin excretion, plasma cystatin C, urinary cystatin C excretion, urinary urea excretion, and urinary ammonia excretion were similar in kl/kl mice and wild-type mice. Plasma urea concentration was, however, significantly higher and plasma ammonia concentration tended to be higher in the previously NH4Cl-treated kl/kl mice than in wild-type mice. In both kl/kl mice and wild-type mice, NH4Cl treatment significantly decreased urinary pH, and significantly increased plasma ammonia concentration, urinary urea excretion, urinary ammonia excretion, and, in wild-type mice, plasma urea concentration. All other measured parameters were not significantly modified by the NH4Cl treatment.

Discussion

Our observations reveal a profound protective effect of NH4Cl treatment on the phenotype of the kl/kl mouse. The NH4Cl treatment abolished the growth deficit and extended the life span >12-fold in male mice and >4-fold in female mice. Thus, NH4Cl dramatically slowed the aging of kl/kl mice. Male kl/kl mice even became fertile (Table 1). The effect was paralleled by and at least in part due to a dramatic decrease in tissue calcification. Vascular calcification is a hallmark of aging.8,57–59 It is triggered by increased extracellular phosphate concentration,14 a predictor of mortality.60

NH4Cl treatment inhibits tissue calcification in kl/kl mice without appreciably affecting plasma 1,25(OH)2D3, Ca2+, and phosphate concentrations. In theory, the inhibition of calcification could have resulted from extracellular fluid acidification, which is known to inhibit calcification in uremic rats.28,32,33 However, according to Figure 3A, NH4Cl treatment did not significantly aggravate the existing acidosis of the kl/kl mice. As revealed by this study, the untreated kl/kl mice suffer from respiratory acidosis most likely resulting from the severe lung emphysema in untreated kl/kl mice. NH4Cl imposes a metabolic acidosis but by the same token prevents the development of lung emphysema (Figure 4). As a result, the respiratory acidosis is replaced by metabolic acidosis with little change of extracellular pH. Thus, tissue acidosis may contribute to but hardly accounts for the effect of NH4Cl on tissue calcification and survival of kl/kl mice. The preexisting acidosis would have been expected to counteract calcification. However, the respiratory acidosis is expected to develop only after birth in parallel to the development of lung emphysema. In later stages, the excessive osteogenic signaling obviously overrides the inhibiting effect of acidosis, which cannot prevent premature aging and dramatic extraskeletal calcification. According to pH measurements in the media (Supplemental Methods), the in vitro effect of NH4Cl on osteogenic signaling was similarly not explained by acidosis. In view of the pK of NH3/NH4+ of 8.9,61 the addition of 500 µM NH4Cl is not expected to modify the pH in a well buffered solution.

NH4Cl treatment further reverses the increased ADH release and hyperaldosteronism, which have previously been observed in kl/kl mice.4 The decrease of plasma aldosterone concentration after NH4Cl treatment could have contributed to the decrease of vascular calcification, because aldosterone stimulates vascular osteoinduction, an effect at least in part due to upregulation of Pit1 expression.16 However, the survival benefit of aldosterone receptor blockade by spironolactone is only modest in kl/kl mice.16 Thus, reversal of hyperaldosteronism presumably contributes to, but does not fully account for, the spectacular survival benefit and phenotypic recovery of kl/kl mice by NH4Cl treatment. In wild-type mice, the plasma aldosterone and ADH concentrations were low and not significantly modified by NH4Cl treatment. Thus, NH4Cl intake reverses the severe dehydration of kl/kl mice, but does not significantly modify volume regulation of euvolemic wild-type mice. To test whether NH4Cl exerts its effect on the lifespan of kl/kl mice only by extracellular fluid expansion, we added controls receiving an equimolar aqueous solution of NaCl instead of NH4Cl. The effect of the NaCl treatment on the life span of the mice was only modest.

NH4Cl treatment did not significantly modify the plasma concentration of the C-terminal FGF23 fragment but significantly decreased the plasma concentrations of intact FGF23. In theory, the effect of NH4Cl treatment on the intact FGF23 levels could have contributed to the extended life span of kl/kl mice. However, according to earlier observations,62 the growth deficit and shortened life span of klotho-deficient mice is not significantly modified by additional knockout of FGF23.

NH4Cl counteracts osteoinductive signaling under high-phosphate conditions. Both in vivo and in vitro, NH4Cl reduces expression of Cbfa1, a transcription factor decisive for the stimulation of osteoblastic differentiation.18 Cbfa1 stimulates the expression of alkaline phosphatase Alp,63 which in turn degrades pyrophosphate and thus fosters precipitation of calcium phosphate. The vascular osteoinduction is closely associated with vascular smooth muscle cell senescence,21 a key factor in vascular aging and injury.64 NH4Cl treatment blunted the expression of senescence indicators Pai-1, p21, and Glb1.65 Excessive extracellular phosphate concentration promotes Tgfb1 production.66 Tgfb1 stimulates cellular senescence, thus contributing to aging and vascular osteoinduction.66 Disruption of Tgfb1–Pai-1 signaling ameliorates vascular calcification.67 We observed enhanced Tgfb1 mRNA expression in untreated kl/kl mice and in HAoSMCs after phosphate treatment. The increased Tgfb1 transcript levels were significantly decreased by NH4Cl treatment. NH4Cl has previously been shown to hinder the maturation of Tgfb1.51

According to our observations, expression of Nfat5 and Sox9 is upregulated in kl/kl mice and decreased by NH4Cl treatment. NFAT5 in turn upregulates the transcript levels of CBFA1 and ALPL. NFAT5 further upregulates the transcript levels of SOX9, a downstream mediator of NFAT5-induced CBFA1 expression.50 Sox9 is involved in the chondrogenic gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells.68 Sox9 is upregulated in vascular tissue of uremic rats.69 The effects of β-glycerophosphate are mimicked and those of NH4Cl are abolished by NFAT5 overexpression. NFAT5 thus contributes to the detrimental vascular effects of excessive phosphate and their inhibition by NH4Cl. Further experiments in HAoSMCs showed that NH4Cl was not able to reduce the phosphate-induced increase of NFAT5 expression in the presence of active TGFB1. Accordingly, NH4Cl is at least partially effective by downregulating TGFB1. By alkalinizing lysosomes, NH4Cl presumably disrupts the processing of TGFB1 and thus its detrimental effects on NFAT5, CBFA1, and ALPL expression.

Excessive ammonia concentrations are toxic particularly to the brain and impaired ammonia detoxification by the liver is a major cause of hepatic encephalopathy.45–47 Apparently, toxic ammonia concentrations have not been reached by the treatment, because the treated mice lived an almost normal life span in contrast with the severe reduction of life span in untreated mice. Moreover, long-term treatment of wild-type mice did not lead to obvious alterations of behavior. Apparently, an increase of ammonia to toxic levels was prevented by urea formation in the liver, leading to the respective increase of renal urea excretion (Supplemental Figure 3).

Similar to vascular calcification in kl/kl mice,17 vascular calcification in patients with CKD is an active process as part of the mineral bone disorder.17,70 Vascular calcification increases the risk for cardiovascular events,71 which are the leading cause of death in patients with CKD.72 The impaired renal phosphate elimination in CKD is followed by hyperphosphatemia, which is paralleled by strong reduction of klotho expression17 and increased expression of osteochondrogenic reprogramming markers73 including CBFA1. Prevention of osteogenic reprogramming in vascular tissue could thus provide a benefit to patients with CKD.73 However, our observations cannot be translated without reservations into treatment of CKD. Unlike in patients with CKD, the kidney is not a priori defective in kl/kl mice and the treated mice have no difficulties excreting the excessive Cl−, NH4+, or urea produced from NH4Cl.

To the extent that NH4Cl disrupts osteogenic signaling by alkalinizing lysosomal pH, it may be effective in CKD without acidosis. Although some observations pointed to a beneficial effect of acidosis in experimental renal disease in rodents,28,32,33 the bulk of observations indicate that alkali treatment has beneficial and acidosis exacerbatory effects in experimental CKD.34–37 Moreover, clinical studies in humans demonstrate that acidosis accelerates and alkali treatment retards the progression of CKD.34,39,74–76 Along those lines, decreased bicarbonate concentrations are associated with decline of eGFR in community-living older persons.77

Our observations may shed light on vascular calcification in further clinical conditions. For instance, NFAT5 is upregulated by hyperglycemia78 and NFAT5-dependent osteoinduction may thus contribute to triggering vascular calcification in diabetes.79 Moreover, NFAT5 is upregulated by dehydration,80 inflammation,80 hypoxia,81 and ischemia.81

In conclusion, our observations uncover a powerful effect of NH4Cl treatment on plasma aldosterone and ADH levels, vascular and soft tissue calcification, osteoinductive signaling, and survival in klotho-hypomorphic mice. NH4Cl treatment is effective despite continued increases of plasma 1,25(OH)2D3, Ca2+, and phosphate concentrations. The observations further disclose a decisive role of Tgfb1 as well as TGFB1-sensitive and osmosensitive transcription factor NFAT5 in the triggering of osteogenic signaling.

Concise Methods

Detailed methods are available in the Supplemental Methods. Animal experiments were conducted according to German law. Where not otherwise indicated, male mice were analyzed. NH4Cl treatment (0.28 M in tap water) started with mating of the parental generation. In plasma obtained from blood drawn from retro-orbital plexus ammonia, phosphate and calcium concentrations were determined photometrically; plasma aldosterone, 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3, C-terminal FGF23, intact FGF23, and PTH were determined by ELISA; and plasma ADH concentration was determined by enzyme immuno assay. Blood pH, pCO2, and electrolytes were measured by a blood analyzer (EDAN care lab i15; EDAN Instruments, China). For histology, tissues were embedded in paraffin, cut in 2- to 3-µm sections, and stained with von Kossa and hematoxylin and eosin stain.

Primary HAoSMCs (Invitrogen) were grown to confluence in Waymouth’s MB 752/1 medium and Ham’s F-12 nutrient mixture (1:1) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were transfected with 2 µg DNA encoding human NFAT5 in pcDNA6V5-HisC vector or with 2 µg DNA of empty pcDNA6V5-HisC vector using X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent and/or treated for 24 hours with 2 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), with 500 µM NH4Cl (Sigma-Aldrich) or with 10 ng/ml human TGFB1 (R&D Systems).

For quantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from aortic tissues and HAoSMCs using TriFast Reagent (Peqlab). RT and quantitative RT-PCR were performed as described in the Supplemental Methods.

Statistical Analyses

Data are provided as means±SEM. Significance was tested with ANOVA or unpaired t tests. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Ursula Kohlhofer, Dennis Thiele, and Elfriede Faber and the meticulous preparation of this article by Tanja Loch and Sari Rübe.

This study was supported by grants from the German Research Foundation (DFG 315/15-1) and the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013), Systems Biology to Identify Molecular Targets for Vascular Disease Treatment (SysVasc, HEALTH-2013 603288).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014030230/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kuro-o M: Klotho, phosphate and FGF-23 in ageing and disturbed mineral metabolism. Nat Rev Nephrol 9: 650–660, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Topala CN, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: Regulation of the epithelial calcium channel TRPV5 by extracellular factors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 16: 319–324, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Pastor J, Nakatani T, Lanske B, Razzaque MS, Rosenblatt KP, Baum MG, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho: A novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB J 24: 3438–3450, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer SS, Kempe DS, Leibrock CB, Rexhepaj R, Siraskar B, Boini KM, Ackermann TF, Föller M, Hocher B, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-O M, Lang F: Hyperaldosteronism in Klotho-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 299: F1171–F1177, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kume E, Iwasaki H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa S, Nagai R, Nabeshima YI: Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390: 45–51, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, McGuinness OP, Chikuda H, Yamaguchi M, Kawaguchi H, Shimomura I, Takayama Y, Herz J, Kahn CR, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-o M: Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309: 1829–1833, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Invidia L, Salvioli S, Altilia S, Pierini M, Panourgia MP, Monti D, De Rango F, Passarino G, Franceschi C: The frequency of Klotho KL-VS polymorphism in a large Italian population, from young subjects to centenarians, suggests the presence of specific time windows for its effect. Biogerontology 11: 67–73, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shroff R, Long DA, Shanahan C: Mechanistic insights into vascular calcification in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 179–189, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staude H, Jeske S, Schmitz K, Warncke G, Fischer DC: Cardiovascular risk and mineral bone disorder in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res 37: 68–83, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: The emerging role of Klotho in clinical nephrology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2650–2657, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedman DJ, Afkarian M, Tamez H, Bhan I, Isakova T, Wolf M, Ankers E, Ye J, Tonelli M, Zoccali C, Kuro-o M, Moe O, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani R: Klotho variants and chronic hemodialysis mortality. J Bone Miner Res 24: 1847–1855, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mizobuchi M, Towler D, Slatopolsky E: Vascular calcification: The killer of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1453–1464, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steitz SA, Speer MY, Curinga G, Yang HY, Haynes P, Aebersold R, Schinke T, Karsenty G, Giachelli CM: Smooth muscle cell phenotypic transition associated with calcification: Upregulation of Cbfa1 and downregulation of smooth muscle lineage markers. Circ Res 89: 1147–1154, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giachelli CM: Vascular calcification: In vitro evidence for the role of inorganic phosphate. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[Suppl 4]: S300–S304, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moe SM, Chen NX: Pathophysiology of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res 95: 560–567, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voelkl J, Alesutan I, Leibrock CB, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kuhn V, Feger M, Mia S, Ahmed MS, Rosenblatt KP, Kuro-O M, Lang F: Spironolactone ameliorates PIT1-dependent vascular osteoinduction in klotho-hypomorphic mice. J Clin Invest 123: 812–822, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quiñones H, Griffith C, Kuro-o M, Moe OW: Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 124–136, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalle Carbonare L, Innamorati G, Valenti MT: Transcription factor Runx2 and its application to bone tissue engineering. Stem Cell Rev 8: 891–897, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murshed M, McKee MD: Molecular determinants of extracellular matrix mineralization in bone and blood vessels. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 359–365, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takemura A, Iijima K, Ota H, Son BK, Ito Y, Ogawa S, Eto M, Akishita M, Ouchi Y: Sirtuin 1 retards hyperphosphatemia-induced calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 2054–2062, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackenzie NC, MacRae VE: The role of cellular senescence during vascular calcification: A key paradigm in aging research. Curr Aging Sci 4: 128–136, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carracedo J, Buendía P, Merino A, Madueño JA, Peralbo E, Ortiz A, Martín-Malo A, Aljama P, Rodríguez M, Ramírez R: Klotho modulates the stress response in human senescent endothelial cells. Mech Ageing Dev 133: 647–654, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuro-o M: Klotho as a regulator of oxidative stress and senescence. Biol Chem 389: 233–241, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quimby JM, Maranon DG, Battaglia CL, McLeland SM, Brock WT, Bailey SM: Feline chronic kidney disease is associated with shortened telomeres and increased cellular senescence. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 305: F295–F303, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander RT, Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Buurman J, Dijkman H, van der Eerden BC, van Leeuwen JP, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG: Klotho prevents renal calcium loss. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2371–2379, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kovesdy CP: Metabolic acidosis and kidney disease: Does bicarbonate therapy slow the progression of CKD? Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3056–3062, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yonova D: Vascular calcification and metabolic acidosis in end stage renal disease. Hippokratia 13: 139–140, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendoza FJ, Lopez I, Montes de Oca A, Perez J, Rodriguez M, Aguilera-Tejero E: Metabolic acidosis inhibits soft tissue calcification in uremic rats. Kidney Int 73: 407–414, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villa-Bellosta R, Sorribas V: Compensatory regulation of the sodium/phosphate cotransporters NaPi-IIc (SCL34A3) and Pit-2 (SLC20A2) during Pi deprivation and acidosis. Pflugers Arch 459: 499–508, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biber J, Hernando N, Forster I, Murer H: Regulation of phosphate transport in proximal tubules. Pflugers Arch 458: 39–52, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barsotti G, Lazzeri M, Cristofano C, Cerri M, Lupetti S, Giovannetti S: The role of metabolic acidosis in causing uremic hyperphosphatemia. Miner Electrolyte Metab 12: 103–106, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jara A, Felsenfeld AJ, Bover J, Kleeman CR: Chronic metabolic acidosis in azotemic rats on a high-phosphate diet halts the progression of renal disease. Kidney Int 58: 1023–1032, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jara A, Chacón C, Ibaceta M, Valdivieso A, Felsenfeld AJ: Effect of ammonium chloride and dietary phosphorus in the azotaemic rat. I. Renal function and biochemical changes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1986–1992, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Łoniewski I, Wesson DE: Bicarbonate therapy for prevention of chronic kidney disease progression. Kidney Int 85: 529–535, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nath KA, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Pathophysiology of chronic tubulo-interstitial disease in rats. Interactions of dietary acid load, ammonia, and complement component C3. J Clin Invest 76: 667–675, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phisitkul S, Hacker C, Simoni J, Tran RM, Wesson DE: Dietary protein causes a decline in the glomerular filtration rate of the remnant kidney mediated by metabolic acidosis and endothelin receptors. Kidney Int 73: 192–199, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wesson DE, Jo CH, Simoni J: Angiotensin II receptors mediate increased distal nephron acidification caused by acid retention. Kidney Int 82: 1184–1194, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres VE, Mujwid DK, Wilson DM, Holley KH: Renal cystic disease and ammoniagenesis in Han:SPRD rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1193–1200, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobre M, Rahman M, Hostetter TH: Current status of bicarbonate in CKD [published online ahead of print August 22, 2014]. J Am Soc Nephrol 10.1681/ASN.2014020205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nowik M, Kampik NB, Mihailova M, Eladari D, Wagner CA: Induction of metabolic acidosis with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) in mice and rats—species differences and technical considerations. Cell Physiol Biochem 26: 1059–1072, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohebbi N, Perna A, van der Wijst J, Becker HM, Capasso G, Wagner CA: Regulation of two renal chloride transporters, AE1 and pendrin, by electrolytes and aldosterone. PLoS ONE 8: e55286, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roos A, Boron WF: Intracellular pH. Physiol Rev 61: 296–434, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ling H, Ardjomand P, Samvakas S, Simm A, Busch GL, Lang F, Sebekova K, Heidland A: Mesangial cell hypertrophy induced by NH4Cl: Role of depressed activities of cathepsins due to elevated lysosomal pH. Kidney Int 53: 1706–1712, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Völkl H, Friedrich F, Häussinger D, Lang F: Effect of cell volume on Acridine Orange fluorescence in hepatocytes. Biochem J 295: 11–14, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Häussinger D, Görg B: Interaction of oxidative stress, astrocyte swelling and cerebral ammonia toxicity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 13: 87–92, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jayakumar AR, Norenberg MD: The Na-K-Cl Co-transporter in astrocyte swelling. Metab Brain Dis 25: 31–38, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pasantes-Morales H, Vázquez-Juárez E: Transporters and channels in cytotoxic astrocyte swelling. Neurochem Res 37: 2379–2387, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Handler JS, Kwon HM: Cell and molecular biology of organic osmolyte accumulation in hypertonic renal cells. Nephron 87: 106–110, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burg MB, Ferraris JD, Dmitrieva NI: Cellular response to hyperosmotic stresses. Physiol Rev 87: 1441–1474, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caron MM, van der Windt AE, Emans PJ, van Rhijn LW, Jahr H, Welting TJ: Osmolarity determines the in vitro chondrogenic differentiation capacity of progenitor cells via nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5. Bone 53: 94–102, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basque J, Martel M, Leduc R, Cantin AM: Lysosomotropic drugs inhibit maturation of transforming growth factor-beta. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 86: 606–612, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hiyama A, Gogate SS, Gajghate S, Mochida J, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV: BMP-2 and TGF-beta stimulate expression of beta1,3-glucuronosyl transferase 1 (GlcAT-1) in nucleus pulposus cells through AP1, TonEBP, and Sp1: Role of MAPKs. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1179–1190, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu X, Bai C, Gong D, Yuan Y, Han L, Lu F, Han Q, Tang H, Huang S, Xu Z: Pleiotropic effects of transforming growth factor-β1 on pericardial interstitial cells. Implications for fibrosis and calcification in idiopathic constrictive pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 1634–1635, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pai AS, Giachelli CM: Matrix remodeling in vascular calcification associated with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1637–1640, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tachi K, Takami M, Sato H, Mochizuki A, Zhao B, Miyamoto Y, Tsukasaki H, Inoue T, Shintani S, Koike T, Honda Y, Suzuki O, Baba K, Kamijo R: Enhancement of bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced ectopic bone formation by transforming growth factor-β1. Tissue Eng Part A 17: 597–606, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu D, Cui W, Liu B, Hu H, Liu J, Xie R, Yang X, Gu G, Zhang J, Zheng H: Atorvastatin protects vascular smooth muscle cells from TGF-β1-stimulated calcification by inducing autophagy via suppression of the β-catenin pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 33: 129–141, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kapustin A, Shanahan CM: Targeting vascular calcification: Softening-up a hard target. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9: 84–89, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peacock M: Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5[Suppl 1]: S23–S30, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weissen-Plenz G, Nitschke Y, Rutsch F: Mechanisms of arterial calcification: Spotlight on the inhibitors. Adv Clin Chem 46: 263–293, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tonelli M, Sacks F, Pfeffer M, Gao Z, Curhan G, Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial Investigators : Relation between serum phosphate level and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation 112: 2627–2633, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyarsky G, Ganz MB, Sterzel RB, Boron WF: pH regulation in single glomerular mesangial cells. I. Acid extrusion in absence and presence of HCO3-. Am J Physiol 255: C844–C856, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakatani T, Sarraj B, Ohnishi M, Densmore MJ, Taguchi T, Goetz R, Mohammadi M, Lanske B, Razzaque MS: In vivo genetic evidence for klotho-dependent, fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23)-mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis. FASEB J 23: 433–441, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weng JJ, Su Y: Nuclear matrix-targeting of the osteogenic factor Runx2 is essential for its recognition and activation of the alkaline phosphatase gene. Biochim Biophys Acta 1830: 2839–2852, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang JC, Bennett M: Aging and atherosclerosis: Mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res 111: 245–259, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, Morrone A, Johung K, Goodwin EC, Kleijer WJ, DiMaio D, Hwang ES: Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging Cell 5: 187–195, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang N, Wang X, Xing C, Sun B, Yu X, Hu J, Liu J, Zeng M, Xiong M, Zhou S, Yang J: Role of TGF-beta1 in bone matrix production in vascular smooth muscle cells induced by a high-phosphate environment. Nephron, Exp Nephrol 115: e60–e68, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kanno Y, Into T, Lowenstein CJ, Matsushita K: Nitric oxide regulates vascular calcification by interfering with TGF- signalling. Cardiovasc Res 77: 221–230, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xu Z, Ji G, Shen J, Wang X, Zhou J, Li L: SOX9 and myocardin counteract each other in regulating vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 422: 285–290, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Neven E, Persy V, Dauwe S, De Schutter T, De Broe ME, D’Haese PC: Chondrocyte rather than osteoblast conversion of vascular cells underlies medial calcification in uremic rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30: 1741–1750, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moe SM, Drüeke T, Lameire N, Eknoyan G: Chronic kidney disease-mineral-bone disorder: A new paradigm. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 14: 3–12, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.London GM, Guérin AP, Marchais SJ, Métivier F, Pannier B, Adda H: Arterial media calcification in end-stage renal disease: Impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 1731–1740, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ: Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 9[Suppl]: S16–S23, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koleganova N, Piecha G, Ritz E, Schirmacher P, Müller A, Meyer HP, Gross ML: Arterial calcification in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2488–2496, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen W, Abramowitz MK: Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 311–317, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goraya N, Wesson DE: Does correction of metabolic acidosis slow chronic kidney disease progression? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 193–197, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Namba T, Takabatake Y, Kimura T, Takahashi A, Yamamoto T, Matsuda J, Kitamura H, Niimura F, Matsusaka T, Iwatani H, Matsui I, Kaimori J, Kioka H, Isaka Y, Rakugi H: Autophagic clearance of mitochondria in the kidney copes with metabolic acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2254–2266, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goldenstein L, Driver TH, Fried LF, Rifkin DE, Patel KV, Yenchek RH, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG, Ix JH, Health ABC Study Investigators : Serum bicarbonate concentrations and kidney disease progression in community-living elders: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 542–549, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hernández-Ochoa EO, Robison P, Contreras M, Shen T, Zhao Z, Schneider MF: Elevated extracellular glucose and uncontrolled type 1 diabetes enhance NFAT5 signaling and disrupt the transverse tubular network in mouse skeletal muscle. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 237: 1068–1083, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Snell-Bergeon JK, Budoff MJ, Hokanson JE: Vascular calcification in diabetes: Mechanisms and implications. Curr Diab Rep 13: 391–402, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Neuhofer W: Role of NFAT5 in inflammatory disorders associated with osmotic stress. Curr Genomics 11: 584–590, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Villanueva S, Suazo C, Santapau D, Pérez F, Quiroz M, Carreño JE, Illanes S, Lavandero S, Michea L, Irarrazabal CE: NFAT5 is activated by hypoxia: Role in ischemia and reperfusion in the rat kidney. PLoS ONE 7: e39665, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.