Abstract

Experimental evidence has clarified distant organ dysfunctions induced by AKI. Crosstalk between the kidney and heart, which has been recognized recently as cardiorenal syndrome, appears to have an important role in clinical settings, but the mechanisms by which AKI causes cardiac injury remain poorly understood. Both the kidney and heart are highly energy-demanding organs that are rich in mitochondria. Therefore, we investigated the role of mitochondrial dynamics in kidney–heart organ crosstalk. Renal ischemia reperfusion (IR) injury was induced by bilateral renal artery clamping for 30 min in 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice. Electron microscopy showed a significant increase of mitochondrial fragmentation in the heart at 24 h. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction, evaluated by echocardiography, were observed at 72 h. Among the mitochondrial dynamics regulating molecules, dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which regulates fission, and mitofusin 1, mitofusin 2, and optic atrophy 1, which regulate fusion, only Drp1 was increased in the mitochondrial fraction of the heart. A Drp1 inhibitor, mdivi-1, administered before IR decreased mitochondrial fragmentation and cardiomyocyte apoptosis significantly and improved cardiac dysfunction induced by renal IR. This study showed that renal IR injury induced fragmentation of mitochondria in a fission-dominant manner with Drp1 activation and subsequent cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the heart. Furthermore, cardiac dysfunction induced by renal IR was improved by Drp1 inhibition. These data suggest that mitochondrial fragmentation by fission machinery may be a new therapeutic target in cardiac dysfunction induced by AKI.

Keywords: acute renal failure, apoptosis, cardiovascular, mitochondria

AKI has recently been recognized as an extremely severe complication in critically ill patients. Despite the progress of patient management in critical care, the mortality of AKI has not changed: it remains as 50%–70%.1,2 Of particular note is a recent large observational study using the Veterans Affairs database that demonstrated that United States veterans with AKI alone have worse outcomes than those diagnosed with an myocardial infarction in the absence of AKI.3 Therefore, development of new AKI diagnosis and treatment is urgently necessary to improve critically ill patient outcomes.

Although AKI is associated with poor outcome of critically ill patients, it is assumed that renal dysfunction alone will not be sufficient to increase mortality. Remote organ effects caused by AKI might contribute to the poor outcome of AKI patients. Recently, organ crosstalk between the kidney and heart has been recognized as cardiorenal syndrome.4 Several different mechanisms by which AKI causes cardiac injury might include systemic immunologic reactions, sympathetic nervous and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system activation, and increased oxidative stress.5,6 Clinically, other factors, such as excess fluid accumulation, hypertension, acidemia, and electrolyte disturbance, appear to worsen AKI-induced cardiac injury.7 However, distant organ effects of AKI on the heart (acute renocardiac syndrome4) have not been clarified sufficiently through basic research to date. Only a few animal studies have described pathologic changes, such as cellular apoptosis and capillary vascular congestion, in the heart after renal ischemia reperfusion (IR) or glycerol injection–induced rhabdomyolysis.8–10

Mitochondria are highly dynamic in response to the environment. Their morphologic changes, including fission and fusion, can be observed in several different types of cancer and in neurologic and cardiovascular diseases.11 Both fusion and fission are mediated by several guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases). Fusion of the outer membrane of mitochondria is regulated by mitofusin 1 (Mfn1) and mitofusin 2 (Mfn2),12,13 whereas the inner membrane fusion involves optic atrophy 1 (OPA1).14 Mitochondria fission is mainly regulated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which is a cytosolic protein that will move to the outer mitochondrial membrane by activation. Reportedly, that inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart and kidney from IR injury.15–17 Nevertheless, it remains uncertain whether mitochondrial fission is further involved in the distant organ effects of AKI on the heart. This study was undertaken to clarify the role of mitochondrial dynamics in AKI-induced cardiac injury, namely acute renocardiac syndrome, using a mouse renal IR model.

Results

Acute Renocardiac Injury Demonstrated by Mitochondrial Fragmentation, Cellular Apoptosis, and Cardiac Dysfunction

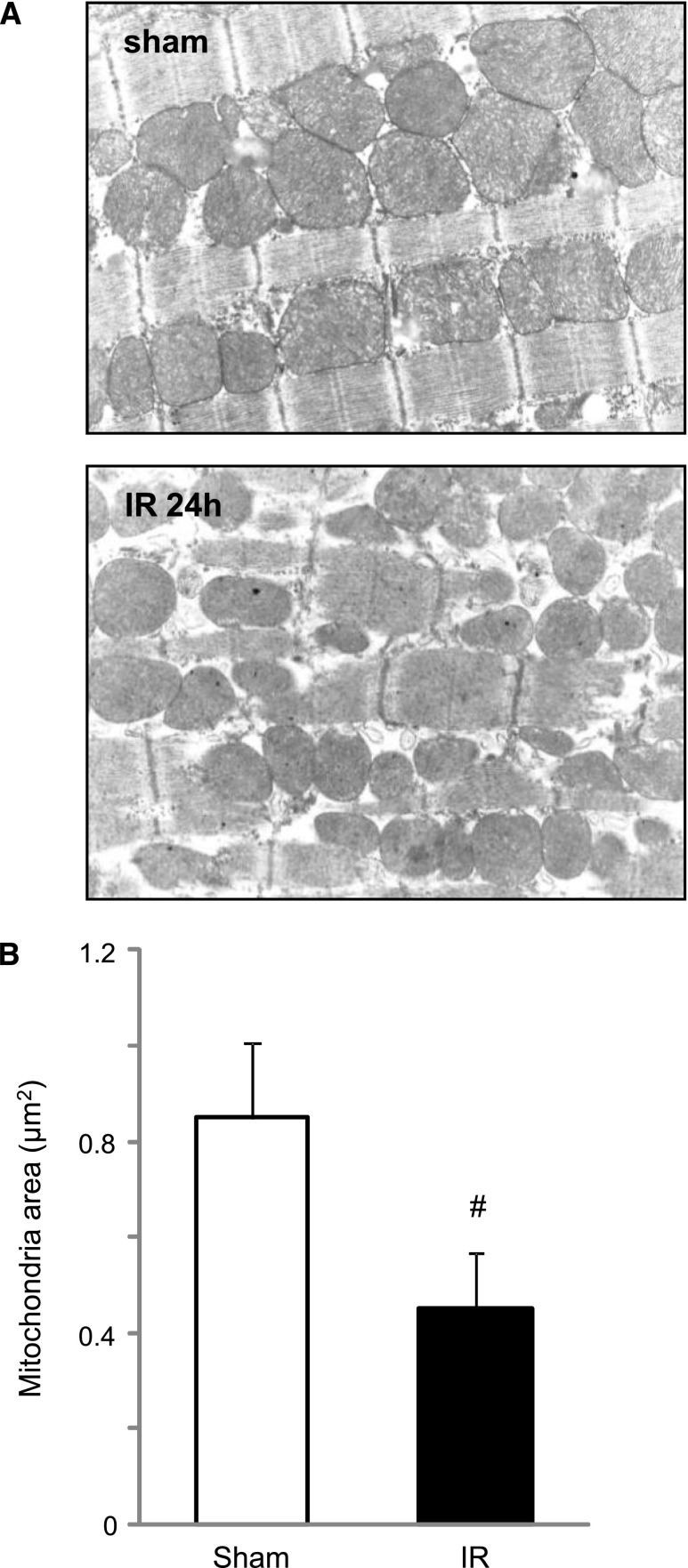

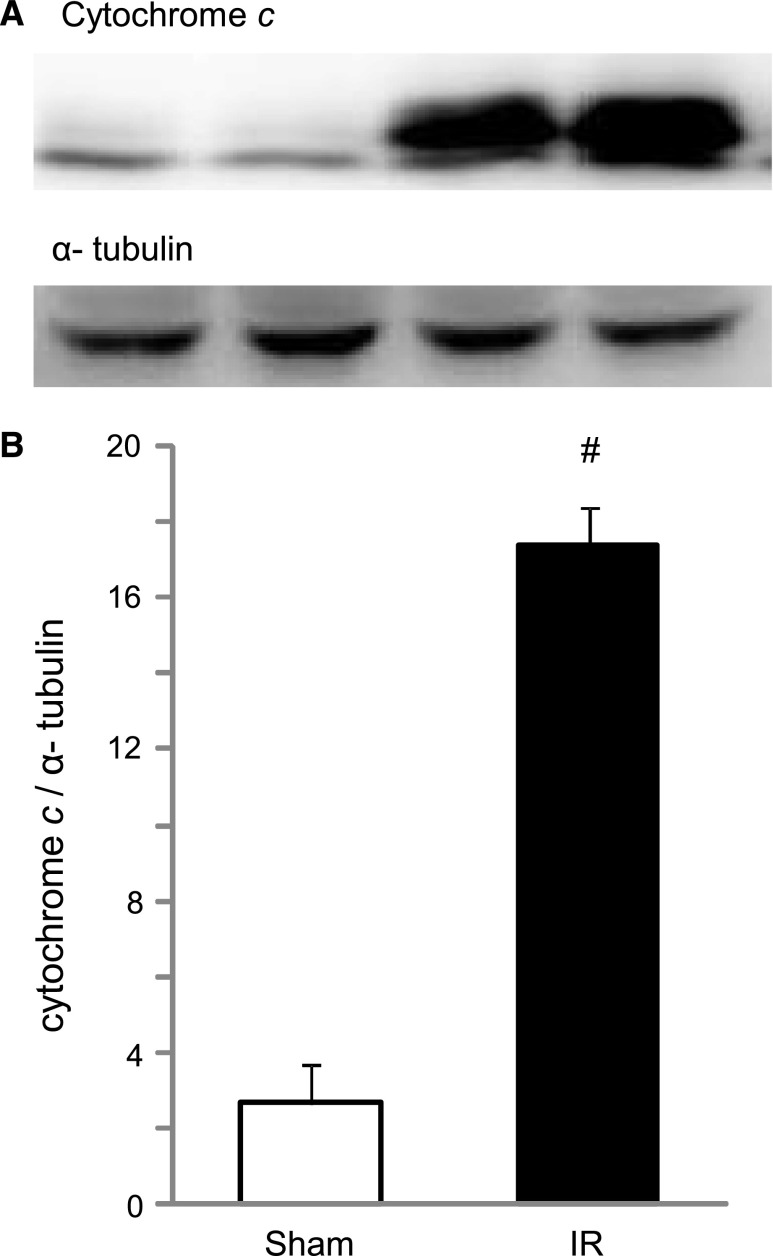

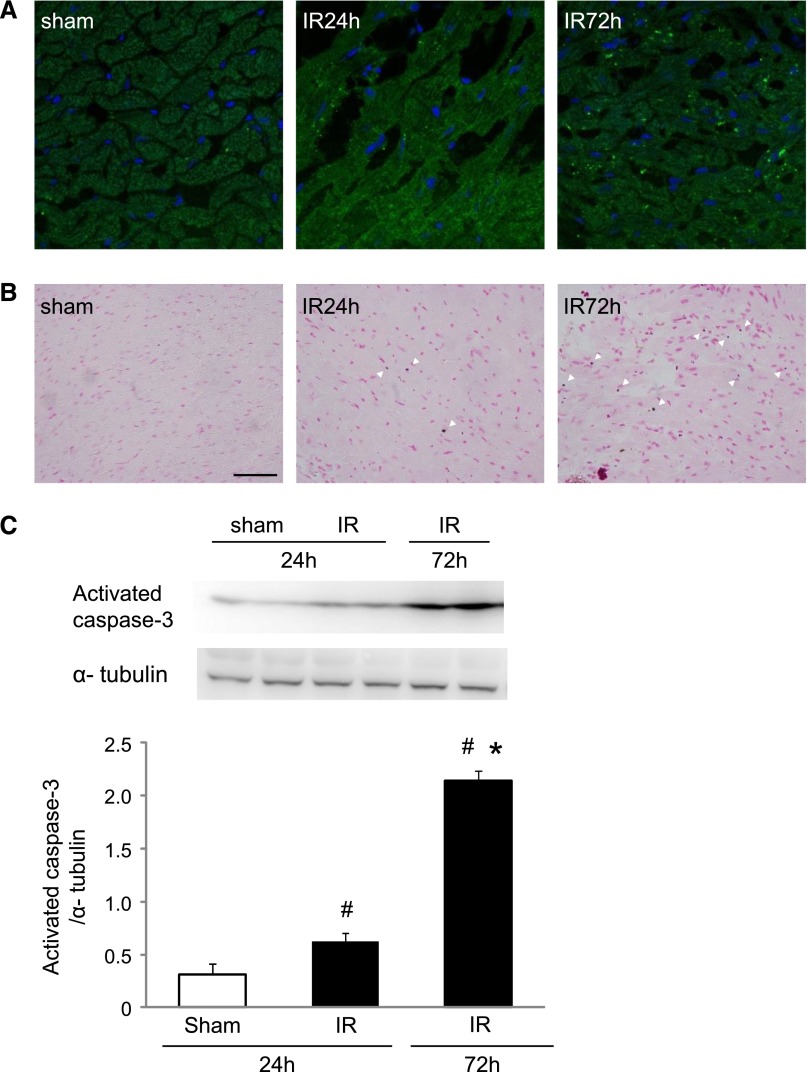

Mouse renal IR was induced by 30 min of bilateral renal artery clamping in male C57BL/6 mice. Remarkable increase of BUN and severe pathologic injuries, including tubular epithelial cell necrosis, were observed 24 h later (Supplemental Figure 1). Pathologic analysis using electron microscopy revealed significantly increased mitochondrial fragmentation in cardiomyocytes in the renal IR group compared with the sham group (Figure 1). Increased cytochrome c release into the cytosol was observed in the renal IR group (Figure 2). At 24 and 72 h after renal IR, cardiomyocyte apoptosis evaluated by immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis of activated caspase-3 was increased significantly in the renal IR group (Figure 3). Finally, renal IR injury caused marked depression of cardiac function at 72 h after the surgery, as indicated by reduced fractional shortening on echocardiography (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial fragmentation in the heart induced by renal IR injury. (A) Electron microscopy showed renal IR increased fragmented mitochondria in the cardiomyocytes after 24 h. Original magnification ×10,000. (B) The area of mitochondria was significantly less in the IR group mice than in the sham-operated mice (n=5 in each group). #P<0.05 versus sham.

Figure 2.

Cytochrome c release into the cytosol of cardiomyocytes was increased by renal IR injury. (A) Representative image of Western blot analysis for cytochrome c in the cytosolic fractions. (B) Histogram showing the relative density of bands compared with α-tubulin (n=6 in each group). #P<0.05 versus sham.

Figure 3.

Apoptosis of cardiomyocytes induced by renal IR injury. (A) Representative image of fluorescence immunohistochemistry for activated caspase-3 in the heart. Original magnification ×630. (B) Representative image of Western blot analysis for activated caspase-3 in whole tissue lysates. Original magnification ×400. (C) Histogram showing the relative density of bands compared with α-tubulin (n=4–6 in each group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus 24 h.

Table 1.

Echocardiography after renal IR injury

| Parameter | Sham | IR 24 h | IR 72 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 608±18 | 544±44 | 580±27 |

| LVDd (mm) | 2.42±0.17 | 2.41±0.15 | 2.33±0.14 |

| LVDs (mm) | 0.91±0.06 | 0.81±0.09 | 1.15±0.12 |

| IVSW (mm) | 0.86±0.06 | 0.75±0.03 | 0.95±0.02 |

| PW (mm) | 1.08±0.12 | 0.98±0.04 | 1.17±0.13 |

| FS (%) | 62.3±1.1 | 66.4±3.5 | 50.8±3.4a |

Values are means±SEM (n=7 in each group). LVDd, diastolic left ventricular dimension; LVDs, systolic left ventricular dimension; IVSW, intraventricular septum wall width; PW, posterior wall width; FS, fractional shortening.

P<0.05 versus sham.

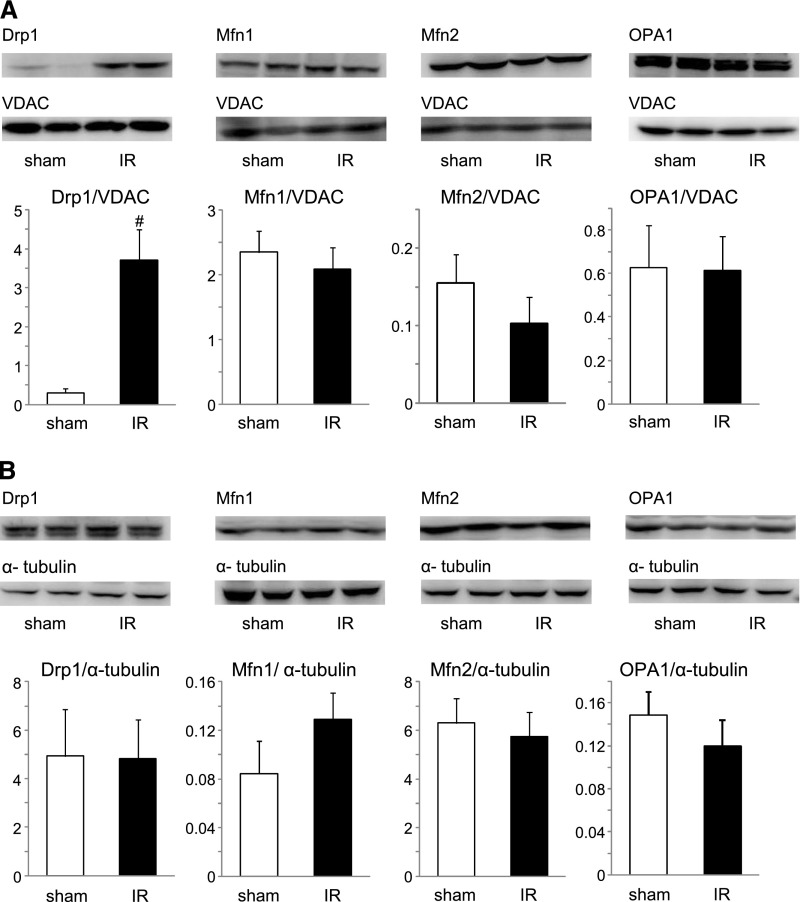

Mitochondrial Dynamics Regulating Proteins and TNF-α in the Heart after Renal IR

We evaluated the mitochondrial dynamics regulating proteins of Mfn1, Mfn2, Opa1 (fusion), and Drp1 (fission) with whole heart tissue lysates and extracted mitochondrial fractions. Heart specimens were collected 24 h after renal IR injury. Among the examined proteins in the mitochondrial fraction, we found that only Drp1 increased significantly in the renal IR group compared with the sham group (Figure 4A). No difference was observed in fusion regulating protein amounts (Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1) in the mitochondrial fraction of the heart (Figure 4A). No mitochondrial dynamics regulating proteins in the whole tissue lysates differed between the sham and renal IR groups (Figure 4B). TNF-α expression in the heart was examined using real-time PCR. In accordance with a previous report, we observed increased expression of TNF-α in the heart after renal IR (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Mitochondrial dynamics regulating proteins in the heart 24 h after renal IR injury. (A) Amounts of each protein in mitochondrial fraction were evaluated using Western blot analysis. Histogram shows the relative density of bands compared with VDAC (n=4–6 in each group). #P<0.05 versus sham. (B) Amounts of each protein in whole tissue lysate were evaluated using Western blot analysis. Histogram shows the relative density of bands compared with α-tubulin (n=4–6 in each group).

Drp1 Inhibitor Mitochondrial Division Inhibitor-1 Attenuated Acute Renocardiac Injury

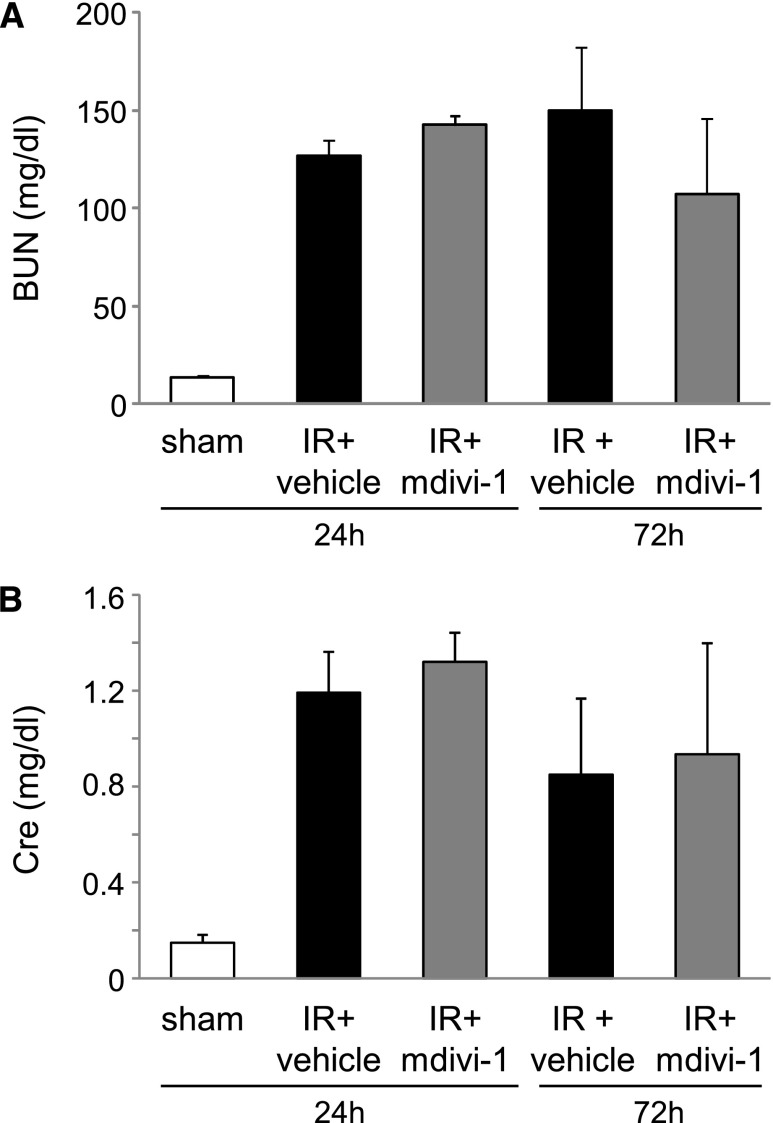

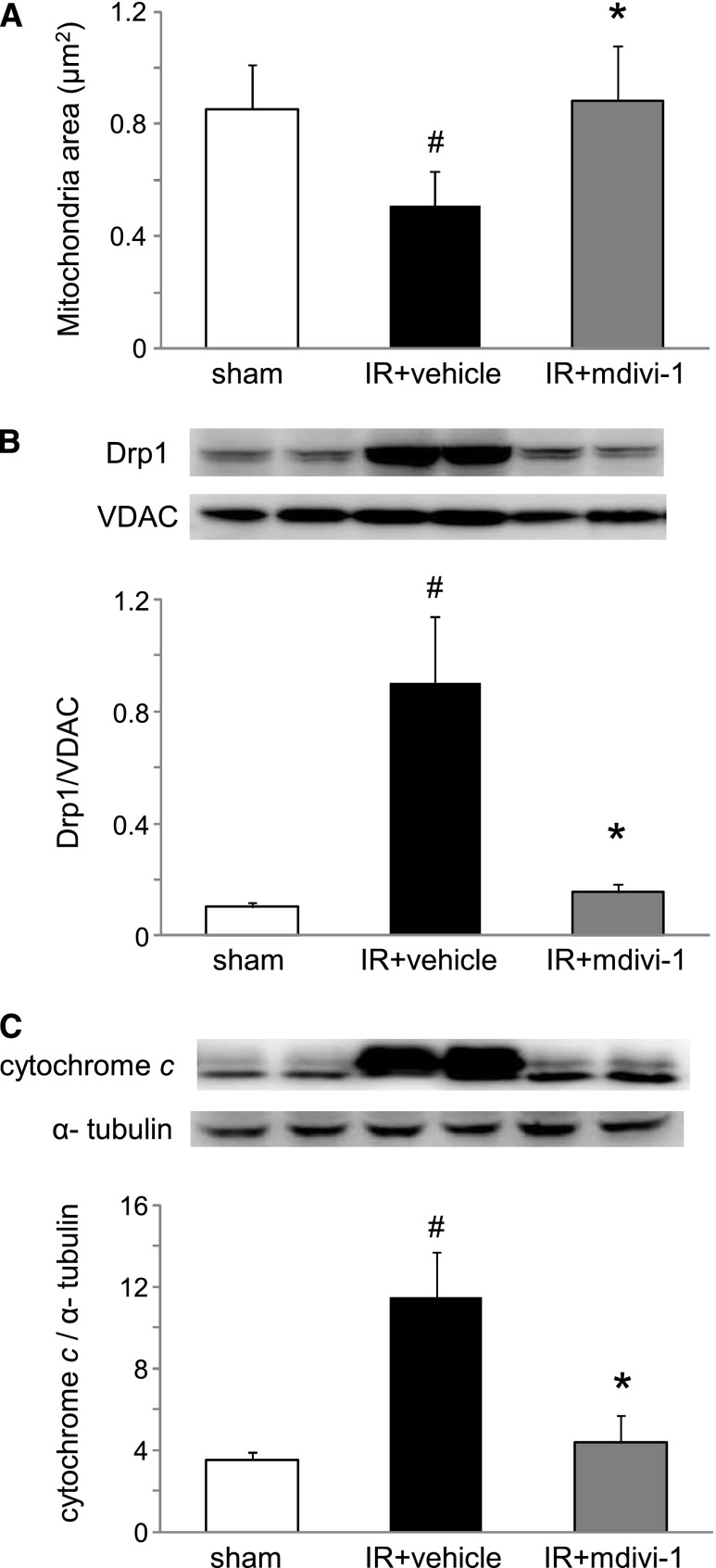

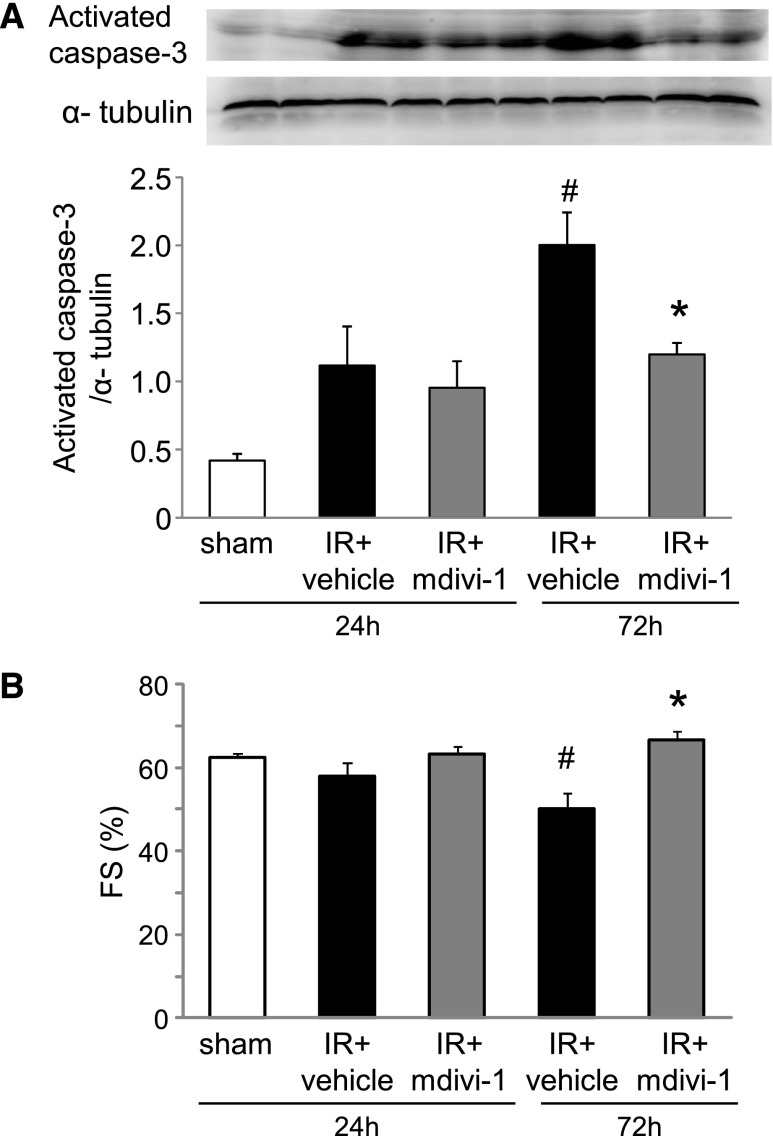

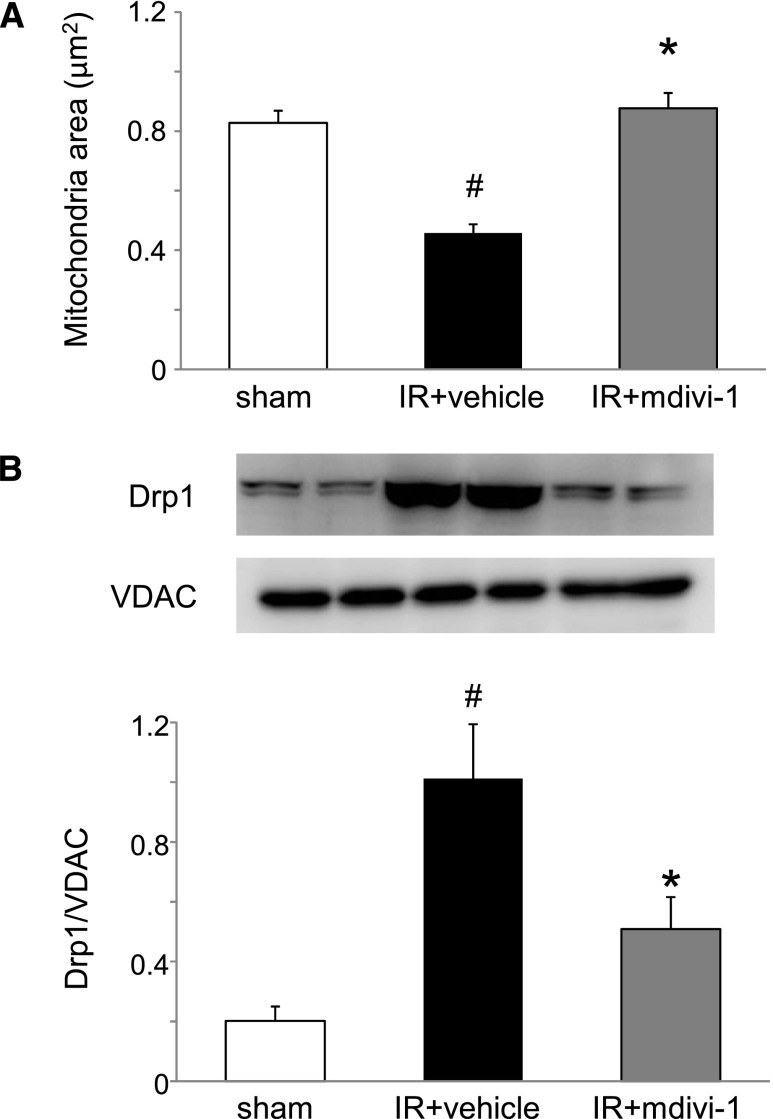

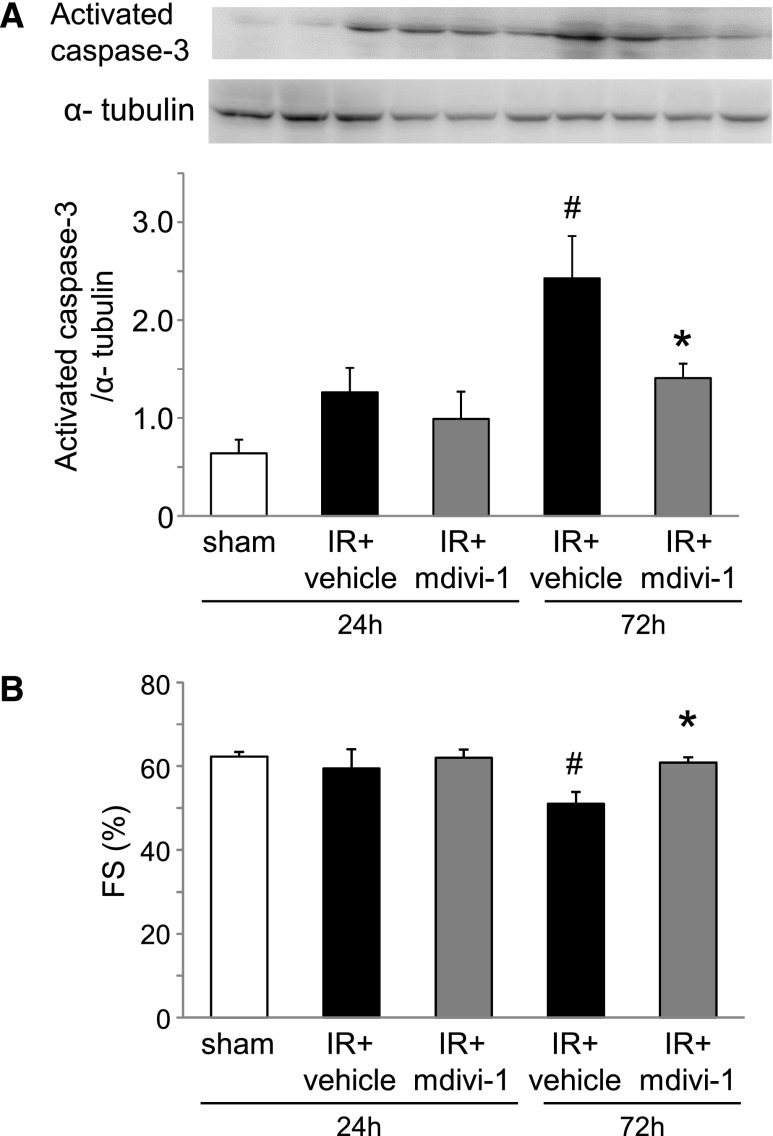

To ascertain the role of Drp1 and mitochondrial fragmentation in the heart, a pharmacologic inhibitor of Drp1 called mitochondrial division inhibitor-1 (mdivi-1) was administered (50 mg/kg) to mice with renal IR. Although mdivi-1 treatment had not suppressed BUN or shown plasma creatinine elevation at 24 or 72 h after renal IR (Figure 5), mitochondrial fragmentation in the heart at 24 h was significantly more improved in the mdivi-1 group than in the vehicle group (Figure 6A). The mdivi-1 treatment suppressed Drp1 translocation to the mitochondria (Figure 6B) and also suppressed cytochrome c release into the cytosol (Figure 6C). Apoptosis of cardiomyocytes and depression of cardiac function examined by echocardiography at 72 h after renal IR were improved by mdivi-1 treatment (Figure 7). However, mdivi-1 treatment did not suppress expression of TNF-α in the heart (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Effects of Drp1 inhibitor mdivi-1 on renal function in mouse renal IR injury. (A) BUN and (B) plasma creatinine (Cre) concentration of each group (n=7 per group).

Figure 6.

Effects of Drp1 inhibitor mdivi-1 on mitochondria of the heart in mouse renal IR injury. (A) Mitochondrial fragmentation was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=5 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR. (B) Drp1 expression in the mitochondria fraction was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=8–10 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR. (C) Cytochrome c release into the cytosolic fraction was suppressed by mdivi-1 treatment (n=6 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR.

Figure 7.

Effects of Drp1 inhibitor mdivi-1 on the heart in mouse renal IR injury. (A) Apoptosis evaluated by Western blot analysis for activated caspase-3 was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=6 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR 72 h. (B) Quantitative analysis of the fractional shortenings (FS) showed the protection of mdivi-1 (n=4–6 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR 72 h.

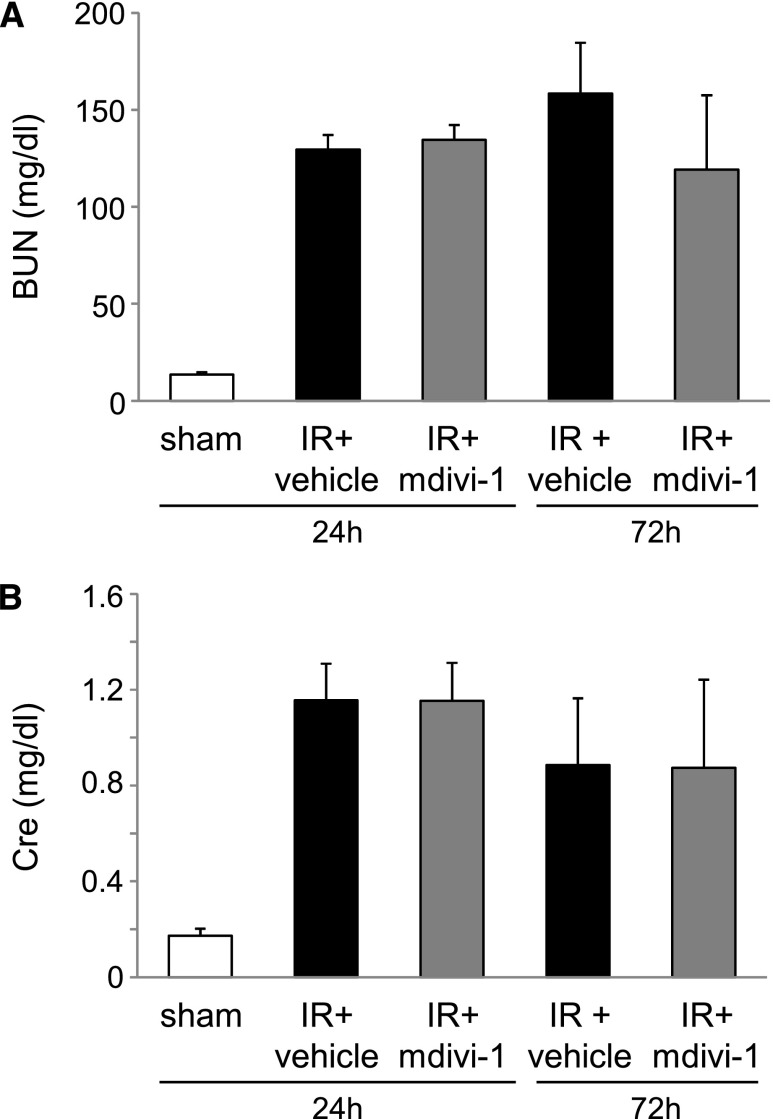

Delayed mdivi-1 treatment that was started at 6 h after renal IR did not suppress elevation of BUN or plasma creatinine (Figure 8), but it showed a protective effect on mitochondrial fragmentation with reduction of Drp1 translocation to the mitochondria in the heart (Figure 9). Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac function were also improved by delayed treatment using mdivi-1 (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Effects of delayed mdivi-1 treatment on renal function in mouse renal IR injury. (A) BUN and (B) plasma creatinine (Cre) concentration of each group (n=7 per group).

Figure 9.

Effects of delayed mdivi-1 treatment on mitochondria of the heart in mouse renal IR injury. (A) Mitochondrial fragmentation was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=5 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR. (B) Drp1 expression in the mitochondria fraction was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=8–10 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR.

Figure 10.

Effects of delayed mdivi-1 treatment on the heart in mouse renal IR injury. (A) Apoptosis evaluated by Western blot analysis for activated caspase-3 was reduced by mdivi-1 treatment (n=6 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR 72 h. (B) Quantitative analysis of the fractional shortenings (FS) showed the protection of mdivi-1 (n=4–6 per group). #P<0.05 versus sham. *P<0.05 versus IR 72 h.

This study also evaluated whether mdivi-1 attenuated renal injury related to mitochondrial fragmentation and renal cell apoptosis. In contrast with the protection by mdivi-1 treatment in the heart, no difference of mitochondrial fragmentation or activated caspase-3 level was apparent between mdivi-1–treated and untreated mice (Supplementary Figure 3).

Discussion

Complication of heart and kidney dysfunction in critically ill patients has a substantial effect on patient outcomes. These two disorders worsen each other synergistically. Therefore, identifying the pathway of organ interaction between the heart and kidney is expected to be crucial for developing targeted therapies to improve the outcomes. This study demonstrated, for the first time ever reported to our knowledge, that the depression of cardiac function caused by AKI was associated with morphologic effect on the heart, as evidenced by mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis, and that Drp1 activation plays a crucial role in AKI-induced cardiac injury (acute renocardiac syndrome). It should be addressed that a Drp1 inhibitor mdivi-1 suppressed cardiac injury after renal IR, even when administered 6 h after renal ischemia insult.

The kidney and heart require large amounts of energy production. Therefore, they are rich in mitochondria. Consequently, it can be assumed that mitochondrial damage contributes to the pathogeneses of acute kidney and heart dysfunction. Recently, Brooks and colleagues reported a remarkable morphologic change of mitochondria in acute kidney injury models, including IR and cisplatin injection.15 Mitochondrial fragmentation was observed earlier than cytochrome c release and cellular apoptosis. Dominant-negative and small interfering RNA knockdown experiments demonstrated the role of Drp1 in mitochondrial fragmentation.15 Sharp and colleagues showed that Drp1 activation during cardiac IR caused left ventricle dysfunction, which was reversed by Drp1 inhibition.17 This study demonstrated that renal IR caused cardiac mitochondrial damage via Drp1 activation. This result might support the view that mitochondrial fission by Drp1 activation is a common pathway by which IR injury in one organ causes injury to another remote organ.

Mitochondria fragmentation describes abnormally small mitochondria and is reportedly observed in apoptotic cells.18,19 A crucial role for mitochondrial fragmentation in apoptosis has been reported.20 A molecular pathway in which increased mitochondrial fission induces cellular apoptosis by Drp1 activation has been suggested. Frank and colleagues reported that inhibition of Drp1 by overexpressing dominant-negative mutant in cultured cells prevented the release of cytochrome c and suppressed apoptosis.21 Germain and colleagues reported that Drp1-dependent cristae remodeling caused cytochrome c release from mitochondria.22 Recently, Ban-Ishihara reported that Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission regulates cytochrome c release via mitochondrial DNA distribution and cristae reformation.23

Presumably, mitochondrial fragmentation is determined as a balance between fission and fusion of mitochondria. Although accumulation of fission GTPase Drp1 on mitochondria during apoptosis has been reported by several studies,21,24–26 insufficient mitochondrial fusion might also contribute to cellular apoptosis. Three large GTPases in the dynamin family mediate mitochondrial fusion: Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1. These fusion GTPases are reportedly related to apoptosis.27,28 However, no change of their expressions was found in mitochondrial fractions or whole tissue lysates of the heart after renal IR in this study. Therefore, mitochondrial fragmentation appeared to be caused mainly by fission machinery in AKI-induced cardiac injury. These results were obtained using Western blot analysis with the mitochondria fraction extracted from heart tissue. Because electron microscopy of the heart tissue showed more fragmented mitochondria in the renal IR group than in the sham group, evaluation of mitochondrial dynamics regulation molecules of Drp1, Mfn1, Mfn2, and OPA1 was influenced by the different number of fragmented mitochondria between these two groups. However, we observed a difference of protein amounts between the renal IR and sham groups not in Mfn1, Mfn2, OPA1, but in Drp1 only. Moreover, we observed reduced mitochondrial fragmentation by Drp1 inhibition in the experiment of mdivi-1 treatment. Therefore, mitochondrial fragmentation observed in the heart of the renal IR group might be caused at least partly by a Drp1-dependent pathway.

Drp1 is an intensively investigated mitochondrial fission–regulating molecule. Approximately 97% of Drp1 is located in the cytoplasm under normative conditions. However, Drp1 will translocate to the outer membrane of mitochondria by activation and initiate the mitochondrial fission process. Several post-translational modifications, such as serine phosphorylation and ubiquitin E3 ligase, regulated Drp1 activity.29,30 An inhibitor of mitochondrial division has been identified using yeast screening of chemical libraries.31 This compound (mdivi-1) inhibits Drp1 assembly and GTPase activity. It also inhibits subsequent mitochondrial fission. Therefore, mdivi-1 is used widely for exploration of the role of mitochondrial fission in apoptosis. Protection by mdivi-1 administration against organ dysfunction, including that of the heart and kidney, has already been reported in mouse IR injury models.15–17 In accordance with these reports, we showed protection by mdivi-1 of cardiac injury caused by AKI, addressing the role of Drp1 in the pathophysiology of remote organ injury by AKI. Although pharmacokinetic properties, including the half-life of mdivi-1 in vivo, are not known, several in vivo studies have demonstrated protection by mdivi-1 in different organ IR injury models at 12–48 h after mdivi-1 injection.15,16,32,33 This study showed reduced Drp1 assembly to the mitochondrial fraction at 24 h and suppression of apoptosis in the heart at 72 h; however, it remains unclear whether mdivi-1 worked only at the initiation phase of renal ischemia-induced cardiac injury or prolonged effects of mdivi-1 suppress cardiac cell apoptosis.

Results of this study do not clarify why Drp1 in the cardiomyocytes was activated by renal IR injury. Several possible pathways can be considered. First, unknown humoral mediator accumulated in blood circulation attributable to decreased renal clearance might induce Drp1 activation. We recently demonstrated increased blood high-mobility group protein B1–induced lung injury via toll-like receptor 4 in another mouse AKI model of bilateral nephrectomy.34 Second, IR injury to one organ might cause systemic reaction, possibly mediated by inflammatory cytokines or cells. Andrés-Hernando and colleagues reported that proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1, IL-1β, and TNF-α were increased not only in the kidney, but in the spleen and liver in renal IR injury.35 Awad and colleagues observed a marked increase of neutrophil margination in the lungs in a mouse renal IR model.36 Patschan and colleagues demonstrated that endothelial progenitor cell homing to the spleen was induced by renal IR.37 We observed increased TNF-α expression in the heart after renal IR injury in accordance with a previous report.9 However, a Drp1 inhibitor, mdivi-1, did not reduce TNF-α expression in the heart; however, it reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. These results suggest that TNF-α does not play a crucial role in mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis in this model of cardiac injury after renal IR. Drp1 activation by TNF-α can be inhibited by mdivi-1 because this additional experiment cannot exclude the role of TNF-α–induced Drp1 activation. Further investigation must be conducted to ascertain the responsible pathways in cardiac injury caused by renal IR. Additionally, we did not clarify the mechanism by which cardiomyocyte apoptosis caused decreased cardiac function evaluated by functional shortening of the left ventricle. More detailed evaluation of cardiac function using ultrasound and other methods should be done in future studies.

Although mdivi-1 treatment attenuated cardiac injury after renal IR in this study, no significant renal protection by mdivi-1 was observed. A previous report described significant protection of mdivi-1 treatment in vivo on the same AKI model of mouse renal IR injury.15 However, a marked difference exists between these studies; the animal model in the previous study appears to be more severe because BUN and blood creatinine in the vehicle-treated mice were much higher in the previous study than those in this study (BUN 250 versus 150 mg/dl, creatinine 2.5 versus 1.2 mg/dl). Therefore, it is possible that severity of renal ischemic insult has some effect on the benefit from mdivi-1 treatment. In addition, the optimal dose and timing of mdivi-1 treatment for renal protection might be different from those for cardiac protection. These issues should be investigated further.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation and subsequent organ disorder was caused in the heart during renal IR injury. Although clinical situations in which AKI results in acute cardiac dysfunction are observed frequently and are defined recently as acute renocardiac syndrome,4 the pathophysiology of this syndrome has not been well demonstrated. Therefore, results obtained from this study strongly suggest that mitochondria fission and apoptosis in the heart as a distant organ effect by AKI should be regarded seriously. They can be good therapeutic targets to improve critically ill patients.

Concise Methods

Animals and Surgical Protocol

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan). The mice were kept on a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to diet and water. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health’s (NIH’s) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals38; all were approved by The University of Tokyo Institutional Review Board.

An IR model induced by 30 min of bilateral renal artery clamp was produced as described in a previous report.39 At 1 h before surgery, mdivi-1 (50 mg/kg dissolved in DMSO [Enzo Life Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan]) was injected intraperitoneally. An equal amount of DMSO was injected as vehicle. In another experiment, the same amount of mdivi-1 or only vehicle (DMSO) was given 6 h after surgery (delayed-treatment group). The mice were euthanized 24 and 72 h after surgery. Blood, kidney, and heart specimens were taken for analyses.

Blood Chemistry

BUN was measured using the urease indophenol method (Urea N B test; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Plasma creatinine measurements using HPLC were conducted as described previously.40

Electron Microscopy

Hearts and kidneys of the animals were perfused with PBS with subsequent fixation in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, 4% paraformaldehyde, and 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The tissue block was examined at high magnification (×10,000). To assess the mitochondrial fragmentation, digital images with scale bars were collected in electron microscopy. The areas of individual mitochondria were measured by tracing using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). For each heart, the respective areas of >100–150 interfibrillar mitochondria were measured in 10 randomly selected electron micrographs of longitudinally arranged cardiomyocytes. For each kidney, mitochondrial fragmentation was evaluated using methods described in a previous report with minor modification.15 Briefly, the respective lengths of approximately 100 individual mitochondria in a single cell were measured to ascertain the percentage of cells that showed filamentous mitochondria <10% long (>2 μm). In all, 100 cells in four individual animals from each group (sham-operated, mdivi-1–treated, and untreated ischemic kidneys) were evaluated.

Immunohistochemistry for Activated Caspase-3

Frozen sections of 5 μm thickness were dried and fixed with ice-cold acetone. After washing the slides with PBS, we incubated them with anti-activated caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and fluorescence conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for the primary antibody for 40 min. The sections were then examined visually using confocal microscopy (LSM 510 Meta NLO imaging system; Carl Zeiss).

Terminal Deoxyuridiine Triphosphate Nick End-Labeling Assay

Apoptotic cells in the heart were identified using terminal deoxyuridiine triphosphate nick end-labeling assay with a CardioTACS In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Mitochondria Fraction Isolation

The mitochondria fraction was isolated from heart and kidney tissue using differential centrifugation with a mitochondria isolation kit for tissue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final supernatants were stocked as cytosol fraction. The presence of the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) only in the mitochondrial fraction demonstrated by Western blot confirmed that the mitochondria fraction was obtained correctly.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein samples were extracted from the heart and kidney with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail, as described previously.41 After centrifugation of the samples, the supernatants were used as heart whole tissue lysates. The lysates were boiled in sample buffer containing 5% SDS with 20% 2-mercaptoethanol and were separated on a 10%–15% SDS-PAGE. After transferring proteins from the gel to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences Corp., Uppsala, Sweden), Western blot analysis was performed using 1:1000 diluted anti-Drp1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), Mfn1 (Abnova Corp., Taipei, Taiwan), Mfn2 (Abnova Corp., Taipei, Taiwan), OPA1 (BD Transduction Laboratories), cytochrome c (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, NJ), VDAC (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), and 1:4000 diluted α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) antibodies, with incubation overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the chemiluminescent signal labeled using ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences Corp.) was detected using a CCD camera system (LAS-4000 mini; Fuji Photo Film Co., Tokyo, Japan). The membrane was then incubated at 50°C for 30 min in a stripping buffer (2% SDS, 100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 12% 0.5 M Tris–HCl, pH 6.8) to remove all probes. The reprobing procedure was performed further with the antibody to α-tubulin. In mitochondrial fractions and whole heart tissue lysates, targeting proteins were normalized, respectively, to VDAC and α-tubulin.

Real-Time PCR Assay for TNF-α Expression in the Heart

The mRNA of TNF-α was examined using real-time quantitative PCR, as explained in earlier reports of the literature.34,41 Quantification of gene expressions was calculated relative to β-actin. Amplification data were analyzed using software (Prism Sequence Detection System version 2.1; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Echocardiography

In vivo cardiac morphology was assessed in nonanesthetized mice using transthoracic echocardiography with an ultrasound machine (SONOS 4500; Philips Medical System, Santa Clara, CA). The M-mode left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic dimensions, intraventricular septum wall width, and posterior wall width were averaged from 3 to 5 beats. The left ventricular percentage of fractional shortenings was calculated as described in earlier reports.42,43

Statistical Analyses

The results of the statistical analyses are expressed as means±SEMs. Differences between groups were analyzed for statistical significance using t tests. Results for which P<0.05 were inferred as statistically significant. These calculations were conducted using software (JMP 9.0; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Disclosures

None

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kahoru Amitani and Satoru Fukuda (The University of Tokyo) for technical support.

Partly supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research (24390212 to E.N., 25461211 to K.D., and 25860288 to Y.H.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation (to E.N.), and the Takeda Science Foundation, Japan (to K.D.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2014080750/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C: Acute kidney injury. Lancet 380: 756–766, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Ronco C: Kidney attack. JAMA 307: 2265–2266, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Shaw AD, Faselis C, Palant CE, Kimmel PL: Association between AKI and long-term renal and cardiovascular outcomes in United States veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 448–456, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, Anavekar N, Bellomo R: Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1527–1539, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosner MH, Ronco C, Okusa MD: The role of inflammation in the cardio-renal syndrome: A focus on cytokines and inflammatory mediators. Semin Nephrol 32: 70–78, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagshaw SM, Hoste EA, Braam B, Briguori C, Kellum JA, McCullough PA, Ronco C: Cardiorenal syndrome type 3: Pathophysiologic and epidemiologic considerations. Contrib Nephrol 182: 137–157, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Young JB, Tang WH: Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 589–596, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson SC, Bowmer CJ, Yates MS: Cardiac function in rats with acute renal failure. J Pharm Pharmacol 44: 1007–1014, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly KJ: Distant effects of experimental renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1549–1558, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nath KA, Grande JP, Croatt AJ, Frank E, Caplice NM, Hebbel RP, Katusic ZS: Transgenic sickle mice are markedly sensitive to renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol 166: 963–972, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archer SL: Mitochondrial dynamics--mitochondrial fission and fusion in human diseases. N Engl J Med 369: 2236–2251, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santel A, Fuller MT: Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J Cell Sci 114: 867–874, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legros F, Lombès A, Frachon P, Rojo M: Mitochondrial fusion in human cells is efficient, requires the inner membrane potential, and is mediated by mitofusins. Mol Biol Cell 13: 4343–4354, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, Rodriguez M, Kellner U, Leo-Kottler B, Auburger G, Bhattacharya SS, Wissinger B: OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet 26: 211–215, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks C, Wei Q, Cho SG, Dong Z: Regulation of mitochondrial dynamics in acute kidney injury in cell culture and rodent models. J Clin Invest 119: 1275–1285, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ: Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 121: 2012–2022, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp WW, Fang YH, Han M, Zhang HJ, Hong Z, Banathy A, Morrow E, Ryan JJ, Archer SL: Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-mediated diastolic dysfunction in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic benefits of Drp1 inhibition to reduce mitochondrial fission. FASEB J 28: 316–326, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braschi E, McBride HM: Mitochondria and the culture of the Borg: Understanding the integration of mitochondrial function within the reticulum, the cell, and the organism. BioEssays 32: 958–966, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinou JC, Youle RJ: Mitochondria in apoptosis: Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev Cell 21: 92–101, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suen DF, Norris KL, Youle RJ: Mitochondrial dynamics and apoptosis. Genes Dev 22: 1577–1590, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ: The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell 1: 515–525, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Germain M, Mathai JP, McBride HM, Shore GC: Endoplasmic reticulum BIK initiates DRP1-regulated remodelling of mitochondrial cristae during apoptosis. EMBO J 24: 1546–1556, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ban-Ishihara R, Ishihara T, Sasaki N, Mihara K, Ishihara N: Dynamics of nucleoid structure regulated by mitochondrial fission contributes to cristae reformation and release of cytochrome c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 11863–11868, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breckenridge DG, Stojanovic M, Marcellus RC, Shore GC: Caspase cleavage product of BAP31 induces mitochondrial fission through endoplasmic reticulum calcium signals, enhancing cytochrome c release to the cytosol. J Cell Biol 160: 1115–1127, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnoult D, Rismanchi N, Grodet A, Roberts RG, Seeburg DP, Estaquier J, Sheng M, Blackstone C: Bax/Bak-dependent release of DDP/TIMM8a promotes Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and mitoptosis during programmed cell death. Curr Biol 15: 2112–2118, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wasiak S, Zunino R, McBride HM: Bax/Bak promote sumoylation of DRP1 and its stable association with mitochondria during apoptotic cell death. J Cell Biol 177: 439–450, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olichon A, Baricault L, Gas N, Guillou E, Valette A, Belenguer P, Lenaers G: Loss of OPA1 perturbates the mitochondrial inner membrane structure and integrity, leading to cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 278: 7743–7746, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugioka R, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y: Fzo1, a protein involved in mitochondrial fusion, inhibits apoptosis. J Biol Chem 279: 52726–52734, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taguchi N, Ishihara N, Jofuku A, Oka T, Mihara K: Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem 282: 11521–11529, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YY, Lee S, Karbowski M, Neutzner A, Youle RJ, Cho H: Loss of MARCH5 mitochondrial E3 ubiquitin ligase induces cellular senescence through dynamin-related protein 1 and mitofusin 1. J Cell Sci 123: 619–626, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cassidy-Stone A, Chipuk JE, Ingerman E, Song C, Yoo C, Kuwana T, Kurth MJ, Shaw JT, Hinshaw JE, Green DR, Nunnari J: Chemical inhibition of the mitochondrial division dynamin reveals its role in Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Dev Cell 14: 193–204, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park SW, Kim KY, Lindsey JD, Dai Y, Heo H, Nguyen DH, Ellisman MH, Weinreb RN, Ju WK: A selective inhibitor of drp1, mdivi-1, increases retinal ganglion cell survival in acute ischemic mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 2837–2843, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang N, Wang S, Li Y, Che L, Zhao Q: A selective inhibitor of Drp1, mdivi-1, acts against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via an anti-apoptotic pathway in rats. Neurosci Lett 535: 104–109, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doi K, Ishizu T, Tsukamoto-Sumida M, Hiruma T, Yamashita T, Ogasawara E, Hamasaki Y, Yahagi N, Nangaku M, Noiri E: The high-mobility group protein B1-Toll-like receptor 4 pathway contributes to the acute lung injury induced by bilateral nephrectomy. Kidney Int 86: 316–326, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrés-Hernando A, Altmann C, Ahuja N, Lanaspa MA, Nemenoff R, He Z, Ishimoto T, Simpson PA, Weiser-Evans MC, Bacalja J, Faubel S: Splenectomy exacerbates lung injury after ischemic acute kidney injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F907–F916, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Awad AS, Rouse M, Huang L, Vergis AL, Reutershan J, Cathro HP, Linden J, Okusa MD: Compartmentalization of neutrophils in the kidney and lung following acute ischemic kidney injury. Kidney Int 75: 689–698, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patschan D, Krupincza K, Patschan S, Zhang Z, Hamby C, Goligorsky MS: Dynamics of mobilization and homing of endothelial progenitor cells after acute renal ischemia: Modulation by ischemic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F176–F185, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Services: NIH Publication No. 86–23. NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto T, Noiri E, Ono Y, Doi K, Negishi K, Kamijo A, Kimura K, Fujita T, Kinukawa T, Taniguchi H, Nakamura K, Goto M, Shinozaki N, Ohshima S, Sugaya T: Renal L-type fatty acid--binding protein in acute ischemic injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2894–2902, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuen PS, Dunn SR, Miyaji T, Yasuda H, Sharma K, Star RA: A simplified method for HPLC determination of creatinine in mouse serum. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F1116–F1119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doi K, Okamoto K, Negishi K, Suzuki Y, Nakao A, Fujita T, Toda A, Yokomizo T, Kita Y, Kihara Y, Ishii S, Shimizu T, Noiri E: Attenuation of folic acid-induced renal inflammatory injury in platelet-activating factor receptor-deficient mice. Am J Pathol 168: 1413–1424, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Belardi D, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, Kass DA: Chronic inhibition of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 5A prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med 11: 214–222, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takimoto E, Koitabashi N, Hsu S, Ketner EA, Zhang M, Nagayama T, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Blanton R, Siderovski DP, Mendelsohn ME, Kass DA: Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 408–420, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.