Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To analyze whether gender influence survival results of kidney transplant grafts and patients.

METHODS

Systematic review with meta-analysis of cohort studies available on Medline (PubMed), LILACS, CENTRAL, and Embase databases, including manual searching and in the grey literature. The selection of studies and the collection of data were conducted twice by independent reviewers, and disagreements were settled by a third reviewer. Graft and patient survival rates were evaluated as effectiveness measurements. Meta-analysis was conducted with the Review Manager® 5.2 software, through the application of a random effects model. Recipient, donor, and donor-recipient gender comparisons were evaluated.

RESULTS

: Twenty-nine studies involving 765,753 patients were included. Regarding graft survival, those from male donors were observed to have longer survival rates as compared to the ones from female donors, only regarding a 10-year follow-up period. Comparison between recipient genders was not found to have significant differences on any evaluated follow-up periods. In the evaluation between donor-recipient genders, male donor-male recipient transplants were favored in a statistically significant way. No statistically significant differences were observed in regards to patient survival for gender comparisons in all follow-up periods evaluated.

CONCLUSIONS

The quantitative analysis of the studies suggests that donor or recipient genders, when evaluated isolatedly, do not influence patient or graft survival rates. However, the combination between donor-recipient genders may be a determining factor for graft survival.

Keywords: Kidney Transplantation, Sex Distribution, Gender and Health, Prognosis, Meta-Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Kidney transplants are considered to be the best therapeutic alternatives for persons suffering from advanced chronic kidney disease. 13 , 18 , 32 Gender differences regarding kidney transplants have been reported in the literature and observed in the clinical practice over the last decades. They affect transplant results, such as in acute and chronic rejections and graft and patient survival rates. Women have less access to transplants. They have increased risk of acute rejection and decreased risk of chronic rejection – those risks increase with age. 9 , 22 In turn, women are observed to account for around 65.0% of living kidney donors. 7 , 37 The etiology of those differences is still unknown, but it probably reflects hormone, immunological, and aging differences, as well as prejudice. 7 , 22 , 28

Survival rates are higher among women following kidney transplants, 9 , 11 but the data are not confirmed by the literature. In a South African study, worse survival rates have been observed among women, but no significant differences were found between genders in graft survival. 23 In another study, no differences were observed between genders in patient and graft survival rates. 27

Knowing differences across genders is necessary to identify possible barriers in the achievement of ideal results and in the development of interventions that overcome those barriers. This review, by focusing on those gender-related differences in the clinical effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapies for kidney transplant maintenance, may promote better understanding, provide more efficient health care, contribute to the creation of clinical protocols, and promote better long-term results for patients.

The objective of this review was to analyze whether genders influence patient and graft survival rates in kidney transplants.

METHODS

This review was conducted according to the recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook. a The article was prepared according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). 21

Observational cohort studies were selected. The selection included studies with patients who received kidney transplants from living or deceased donors for the first time or more than once, mentioning gender differences concerning pre-transplant characteristics, and finding survival results for grafts, patients, or for both. Studies that did not involve immunosuppressants for maintenance of kidney transplants, pharmacokinetic studies, economic evaluation studies, review studies, and studies conducted on animals were excluded, as per the exclusion criteria.

An electronic search was performed for articles published until December 2013, on Medline (PubMed), Latin-American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (LILACS), Cochrane Controlled Trials Databases (CENTRAL), Embase databases. Manual searches were also conducted in the reference lists of all studies selected from the published systematic review. 44 Studies from the grey literature were also sought after: in the thesis and essay database from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES – Coordination for the Improvement of Undergraduate Personnel), in Biblioteca Digital Brasileira de Teses e Dissertações (Brazilian Digital Library of Thesis and Dissertations), and in Universidade de São Paulo’s Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations. There were no restrictions regarding dates and languages of publications. Table 1 describes the search strategy used in each surveyed database.

Table 1. Bibliographical search strategies for observational studies conducted in each database, on 12/12/2013.

| Database | Studies | Search strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Medline (via PubMed) | 3,263 | ((((((((((((((Transplantation, Kidney) OR Kidney Transplantations) OR Transplantations, Kidney) OR Transplantation, Renal) OR Renal Transplantation) OR Renal Transplantations) OR Transplantations, Renal) OR Grafting, Kidney) OR Kidney Grafting)) OR (Kidney Transplantation) OR (“Kidney Transplantation”[Mesh) AND (((((male[Title/Abstract) OR female[Title/Abstract) OR gender[Title/Abstract)) OR (((((((((Factor, Sex) OR Factors, Sex) OR Sex Factor)) OR (Sex Factors)) OR (“Sex Factors”[Mesh)) OR (((((((Characteristic, Sex) OR Characteristics, Sex) OR Sex Characteristic) OR Sex Differences) OR Difference, Sex) OR Differences, Sex) OR Sex Difference)) OR (Sex Characteristics)) OR (“Sex Characteristics”[Mesh))) AND Humans[Mesh)) AND ((((“Cohort Studies”[Mesh) OR (cohort study) OR (studies, cohort) OR (study, cohort) OR (concurrent studies) OR (studies, concurrent) OR (concurrent study) OR (study, concurrent) OR (historical cohort studies) OR (studies, historical cohort) OR (cohort studies, historical) OR (cohort study, historical) OR (historical cohort study) OR (study, historical cohort) OR (analysis, cohort) OR (analysis, cohort) OR (cohort analyses) OR (cohort analysis) OR (closed cohort studies) OR (cohort studies, closed) OR (closed cohort study) OR (cohort study, closed) OR (study, closed cohort) OR (studies, closed cohort) OR (incidence studies) OR (incidence study) OR (studies, incidence) OR (study, incidence) OR (cohort studies) OR (cohort) OR (cohort analysis) OR (cohort study) OR (prospective cohort) OR (retrospective cohort) OR (retrospective cohort study) OR (prospective cohort study) OR (“Follow-Up Studies”[Mesh) OR (follow up studies) OR (follow-up study) OR (studies, follow-up) OR (study, follow-up) OR followup studies OR (followup study) OR (studies, followup) OR (study, followup) OR (“Epidemiologic Studies”[Mesh OR “Cross-Sectional Studies”[Mesh OR “Retrospective Studies”[Mesh OR “Longitudinal Studies”[Mesh OR “Prospective Studies”[Mesh))) OR ((case* AND and control*[Text Word)))) |

| Embase | 2,363 | ‘kidney transplantation’/exp ANDembase/lim AND ‘gender and sex’/exp ANDembase/lim OR ‘sex difference’/exp ANDembase/lim OR ‘gender’/exp ANDembase/lim OR ‘sex ratio’/exp ANDembase/lim AND (‘cohort analysis’/de OR ‘comparative study’/de OR ‘control group’/de OR ‘controlled study’/de OR ‘human’/de OR ‘observational study’/de OR ‘outcomes research’/de OR ‘prospective study’/de OR ‘retrospective study’/de) |

| CENTRAL | 280 | (“Transplantation, Kidney” OR “Kidney Transplantations” OR “Transplantations, Kidney” OR “Transplantation, Renal” OR “Renal Transplantation” OR “Renal Transplantations” OR “Transplantations, Renal” OR “Grafting, Kidney” OR “Kidney Grafting” OR “Kidney Transplantation” OR “MeSH descriptor:Kidney Transplantation 1 tree(s) exploded”) AND (“male” OR “female” OR “gender” OR “Factor, Sex” OR “Factors, Sex” OR “Sex Factor” OR “Sex Factors” OR “MeSH descriptor:Sex Factors explode all trees”) AND “Characteristic, Sex” OR “Characteristics, Sex” OR “Sex Characteristic” OR “Sex Differences” OR “Difference, Sex” OR “Differences, Sex” OR “Sex Difference” OR “Sex Characteristics” OR “MeSH descriptor:Sex Characteristics explode all trees”) AND (“graft rejection OR MeSH descriptor:Graft Rejection explode all trees”) AND (“survival rate” “MeSH descriptor:Survival Rate explode all trees”) AND “graft survival” |

| LILACS | 87 | (tw:(transplantation kidney)) OR (tw:(transplantation renal)) AND (tw:(gender differences)) OR (tw:(gender Characteristics)) OR (tw:(Sex Characteristics)) OR (tw:(sex differences)) AND (tw:(survival rate)) AND (tw:(survival graft)) |

After duplicate studies were excluded, two independent reviewers selected the references in three phases: analysis of titles, abstracts, and full texts. The disagreements were settled by a third reviewer. The data – including methodological quality, subject information, treatment length, and patient and graft survival rates – were extracted and collected in duplicate in a Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet.

Methodological quality evaluations were independently conducted by the reviewers, and related disagreements were settled through the consensus among reviewers. Newcastle-Ottawa scale b for observational studies was used. In this scale, each study is evaluated in three dimensions: selection of study groups; the comparability among groups; and the ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest. Total score was up to nine stars – above six, studies are considered to be high quality.

In order to be analyzed, the studies were grouped according to the comparison of results among:

a)Donor genders – male donors (MD) and female donors (FD);

b)Recipient genders – male recipients (MR) and female recipients (FR);

c)Donor-recipient genders – male donor-male recipient transplants (MD-MR), male donor-female recipient transplants (MD-FR), female donor-female recipient transplants (FD-FR), female donor-male recipient transplants (FD-MR).

The study data were combined using randomized effects model in Metaview module of Review Manager software, version 5.3. The results were presented as relative risk for dichotomous variables, with a confidence interval of 95%. Analyses with I 2 > 40.0% and p-value of Chi-squared test < 0.10 were considered to be significant heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate heterogeneity causes, with the exclusion of one study at a time, with changes being verified in the values of I 2 and p.

The outcomes that were evaluated in the meta-analysis were graft survival and patient survival per follow-up period (one, two, three, five, eight, 10 years or more).

RESULTS

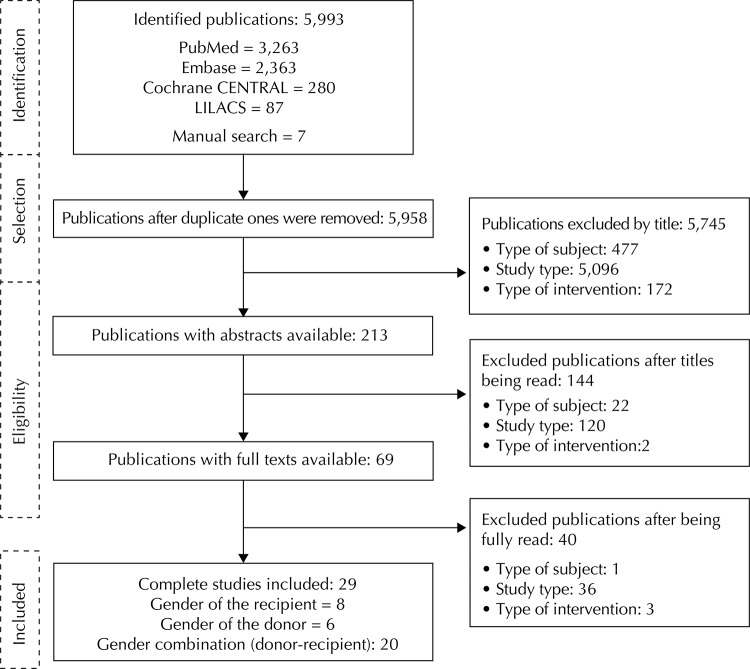

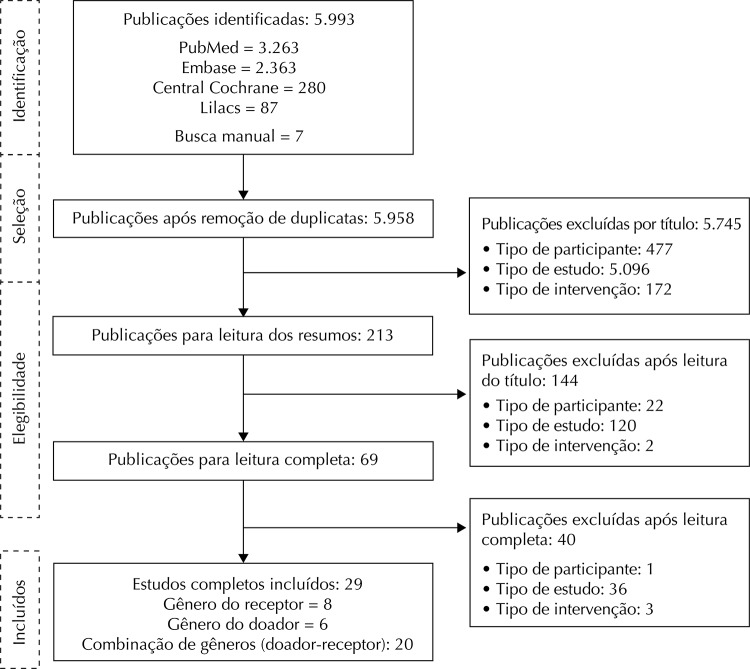

A total of 5,993 publications were initially identified in the electronic databases, and seven through manual searches, all adding up to 6,000 publications. Of these, 500 publications were excluded because of the participant type, 5,251 due to study type and 177 due to the intervention. The main causes for excluded studies were: studies that did not analyze the outcome of interest (patient and graft survival rates), ones that did not include kidney transplants, review, pharmacokinetic, pharmacoeconomic studies, among others. After duplicate publications were eliminated and the reviewers conducted their analyses, 29 cohort studies were included, which involved 765.753 patients. Among those, six studies compared the measurements from results involving donor genders (MD and FD); eight studies, involving recipient genders (MR and FR), and for 20 others, results involving donor-recipient genders (MD-MR, MD-FR, FD-FR, FD-MR) (Figure). One study was included in donor, recipient, and donor-recipient gender comparisons; 5 another one 14 was included in the comparison between recipient and donor-recipient genders; and two studies, in the comparison between donor and donor-recipient genders. 3 , 25

Figure. Flowchart of study selection for systematic review.

Out of the 29 observational studies included, 28 were retrospective and one was prospective. 38 Most studies have not reported average follow-up periods, and the data from the cohorts were collected from 1978 to 2009. In the comparison between donor genders, 9,673 subjects were evaluated in the six studies. In the comparison between recipient genders, 84,070 subjects were evaluated in the eight studies included. In the comparison between donor-recipient genders, 672,010 subjects were evaluated in the 20 studies included. In regards to types of donors, 12 studies evaluated deceased donors, eight evaluated living donors, and nine evaluated both kinds (living and deceased) (Table 2).

Table 2. General characteristics of studies included in comparisons between genders.

| Study | Comparison between genders | Number of patients | Country where the study was conducted | Type of donor | Donor age (years) | Recipient age (years) | Immunosuppressive therapy | Collection period | Average supervision type (months) | Newcastle Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neugarten et al25 (1996) | Donor and donor-recipient | 651 | USA | Both | NR | NR | Ciclosporin | 1979 to 1994 | NR | 7 |

| Buchler et al4 (1997) | Donor | 354 | France | Deceased | NRa | 49 | Multiple | 1985 to 1995 | NR | 6 |

| Busson e Benoit5 (1997) | Recipient. donor. and donor-recipient | 6,889 | France | Deceased | NRa | NRa | NR | 1989 to 1992 | NR | 7 |

| Valdes et al41 (1997) | Donor | 858 | Spain | Deceased | NRa | NRa | NR | 1981 to 1995 | NR | 7 |

| Ben Hamida et al3 (1999) | Donor and donor-recipient | 182 | Tunisia | Living | 39.3 | 28.1 | Multiple | 1986 to 1998 | NR | 7 |

| Oien et al29 (2007) | Donor | 739 | Norway | Living | NRa | NRa | Multiple | 1994 to 2004 | 55.1 | 8 |

| Sánches Garcia et al35 (1989) | Recipient | 760 | Spain | Deceased | NR | NR | Ciclosporin | 1978 to 1988 | NR | 7 |

| Nyberg et al27 (1997) | Recipient | 1,000 | Sweden | Both | NRa | NRa | Ciclosporin + prednisolone | 1985 to 1993 | 73 | 8 |

| Avula et al2 (1998) | Recipient | 431 | India | Living | 43.18 | 33.87 | Multiple | NR | 9 | 6 |

| Meier-KriescheH et al22 (2001) | Recipient | 73,477 | USA | Both | NRa | NRa | Multiple | 1988 to 1997 | NR | 8 |

| Inoue et al14 (2002) | Recipient and donor-recipient | 205 | Japan | Both | NRa | NRa | Cisclosporin or FK506 | 1987 to 2000 | NR | 7 |

| Moosa23 (2003) | Recipient | 542 | South Africa | Deceased | NRa | 37 | Multiple | 1976 to 1999 | 75.6 | 7 |

| Chen et al6 (2013) | Recipient | 766 | China | Both | NRa | NRa | Multiple | 1988 to 2009 | NR | 7 |

| Ellison etal8 (1994) | Donor-recipient | 3,314 | USA | Both | NR | NR | NR | 1987 to 1992 | NR | 8 |

| Shaheen et al38 (1998)b | Donor-recipient | 406 | Saudi Arabia | Living | 31.3 | 34.3 | Ciclosporin | NR | 55.2 | 7 |

| Vereerstraeten et al42 (1999) | Donor-recipient | 741 | Belgium | Deceased | 34.8 | 36.9 | Multiple | 1983 to 1997 | NR | 7 |

| Zeier et al43 (2002) | Donor-recipient | 119,195 | 49 countries | Both | 38.3 | 44.3 | NR | 1985 to 2000 | NR | 8 |

| Kayler et al16 (2003) | Donor-recipient | 30,258 | USA | Living | NRa | NRa | NR | 1990 to 1999 | NR | 8 |

| Kwon e Kwak19 (2004) | Donor-recipient | 614 | South Korea | Living | NRa | NRa | NR | 1979 to 2002 | NR | 7 |

| Pugliese et al34 (2005) | Donor-recipient | 3,233 | Italy | Deceased | 42.1 | 44.5 | NR | 1995 to 2000 | NR | 8 |

| Jacobs et al15 (2007) | Donor-recipient | 730 | USA | Living | 39.7 | 46.4 | NR | 1979 to 1994 | NR | 8 |

| Gratwohl et al12 (2008) | Donor-recipient | 195,516 | 45 countries | Deceased | 38 | 44.7 | NR | 1985 to 2004 | 67.2 | 8 |

| Kim e Gill17 (2009) | Donor-recipient | 117,877 | USA | Deceased | NRa | NRa | NR | 1990 to 2004 | NRa | 7 |

| Lankarani et al20 (2009) | Donor-recipient | 2,649 | Iran | Living | NRa | NRa | NR | 1992 to 2005 | NR | 8 |

| Shaheen et al39 (2010) | Donor-recipient | 524 | Saudi Arabia | Deceased | 33.6 | 33.9 | Múltipla | 2003 to 2007 | 20.9 | 8 |

| Głyda et al11 (2011) | Donor-recipient | 154 | Poland | Deceased | NRa | NRa | Múltipla | NR | NR | 7 |

| Zukowski et al45 (2011) | Donor-recipient | 230 | Poland | Deceased | 33.1 | 37.6 | NR | NR | NR | 8 |

| Abou-Jaoude et al1 (2012) | Donor-recipient | 135 | Lebanon | Both | NRa | NRa | Múltipla | 1998 to 2007 | NR | 7 |

| Tan et al40 (2012) | Donor-recipient | 188,507 | USA | Both | NRa | NRa | NR | 1988 to 2006 | NR | 8 |

NR: not reported; NRa: not reported in the expected way

b Prospective cohort.

The majority of subjects (donor, recipient, and donor-recipient) were males, for all gender comparisons. All studies included evaluated graft survival rates, but only eight of them evaluated patient survival rates. 1 , 14 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 27 , 39 , 43

Out of the 29 studies included, two of them were observed to have scores of six as per New-Castle Ottawa scale; 2 , 4 14 (48,3%) of them had score seven; and 13, eight (Table 2).

Out of the six studies included in the systematic review for donor gender comparison, five of them were included in the meta-analysis for graft survival outcome. 3 - 5 , 29 , 41 The study by Neugarten et al 25 was not found to have enough numerical data for the quantitative analysis. The studies included in the donor gender comparison did not evaluate patient survival.

Regarding graft survival, the relative risks (RR), as grouped chronologically according to follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and ten years were, respectively, 1.02 (95%CI 0.97;1.07; p = 0.43; I2 = 70.0%), 1.03 (95%CI 1.00;1.07; p = 0.07; I2 = 27.0%), 1.02 (95%CI 0.94;1.12; p = 58; I2 = 67.0%), 0.89 (95%CI 0.79;1.00; p = 0.06; I2 = 0%), 0.86 (95%CI 0.73;1.02; p = 0.09; I2 = 11.0%;), and 0.82 (95%CI 0.68;0.98; p = 0.03; I2 = 0%). Only at the 10-year follow-up period was the difference significant for graft survival, favoring male donors. Heterogeneity was high and significant for follow-up periods of one and three years (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary of meta-analyses for survival of grafts according to donor genders (FD or MD) and recipient genders (FR or MR); and survival of patients according to kidney transplant recipient genders.

| Outcome/Time | Studies | Subjects | RR | 95%CI | pa | I2 (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft survival | FD versus MD | |||||

| 1 year | 3,5,30 | 7,478 | 1.02 | 0.97;1.07 | 0.43 | 70.0c |

| 2 years | 5,30,41 | 8,154 | 1.03 | 1.00;1.07 | 0.07 | 27.0 |

| 3 years | 5,30,41 | 8,154 | 1.02 | 0.94;1.12 | 0.58 | 67.0c |

| 5 years | 3,30 | 589 | 0.89 | 0.79;1.00 | 0.06 | 0 |

| 8 years | 4,30 | 761 | 0.86 | 0.73;1.02 | 0.09 | 11.0 |

| 10 years | 3,30 | 589 | 0.82 | 0.68;0.98 | 0.03 | 0 |

| Graft survival | FR versus MR | |||||

| 1 year | 2,5,10 | 8,348 | 1.01 | 0.99;1.03 | 0.30 | 0 |

| 5 years | 2,6,15 | 1,402 | 0.99 | 0.88;1.12 | 0.88 | 75.0c |

| 10 years and older | 15,24 | 747 | 1.23 | 0.68;2.24 | 0.50 | 95.0c |

| Patient survival | FR versus MR | |||||

| 10 years and older | 15,24 | 747 | 0.96 | 0.67;1.37 | 0.81 | 95.0c |

RR: relative risk

a Value of p < 0.10 of Z-test for all effects.

b Value of I2 > 40.0% indicates statistical heterogeneity among studies.

c Significant heterogeneity (p < 0.10).

Out of the eight studies included in the systematic review for recipient gender comparison, six were included in the meta-analysis for graft survival outcome. 2 , 5 , 6 , 14 , 23 , 35 The studies by Nyberg et al 27 and Meier-Kriesche et al 22 were not found to have numerical data in order to be included in the quantitative analysis. Thus, meta-analyses were conducted for monitored periods of one, five, and 10 years or more.

In the meta-analysis regarding graft survival for one year, four comparisons of three studies were included. In the study by Sánchez Garcia et al, 35 (1989) the influence from immunosuppressive therapy was compared to genders in two groups: Sánchez Garcia et al 35 (1989a), ciclosporin-treated; and Sánchez Garcia et al 35 (1989b), ciclosporin-untreated.

Regarding graft survival, the relative risks (RR), as grouped chronologically according to follow-up periods of one, five, and 10 years or more were, respectively, 1.01 (95%CI 0.99;1.03; p = 0.30; I2 = 0%), 0.99 (95%CI 0.88;1.12; p = 0.88; I2 = 75.0%), 1.23 (95%CI 0.68;2.24; p = 0.50; I2 = 95.0%). No significant differences were found for any of the follow-up periods, and no recipient genders were highlighted among the groups. Heterogeneity was high and significant for follow-up periods of five and 10 years or more (Table 3).

Regarding patient survival, two studies were included in the related meta-analysis. 14 , 24 The meta-analysis was conducted for the follow-up period of 10 years or more, heterogeneity was high and the difference was not significant (RR = 0.96; 95%CI 0.67;1.37; p = 0.81; I2 = 95.0%) (Table 3).

In order to evaluate donor-recipient genders, six comparisons were analyzed: MD-MR versus FD-MR, MD-MR versus FD-FR, MD-MR versus MD-FR, MD-FR versus FD-FR, MD-FR versus FD-MR, FD-FR versus FD-MR. Regarding graft survival outcome, 13 studies were included 1 , 5 , 8 , 11 , 15 - 17 , 19 , 20 , 38 - 40 , 43 in the meta-analyses (Table 4).

Table 4. Summary of meta-analyses for survival of grafts according to kidney transplant donor-recipient genders.

| General characteristics | MD-MR versus MD-FR | MD-FR versus FD-FR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Studies | Number of patients | RR | 95%CI | pa | I2 (%)b | Number of patients | RR | 95%CI | pa | I2 (%)b |

| 1 year | 1,5,8,15,16,17,20,39,40 | 211,025 | 1.03 | 1.01;1.05 | < 0.01 | 92.0c | 181,223 | 1.02 | 1.01. 1.04 | < 0.01 | 83.0c |

| 2 years | 5,8,15,20 | 8,411 | 1.05 | 1.03;1.08 | < 0.01 | 25.0 | 7,575 | 1.02 | 1.00;1.04 | 0.10 | 9.0 |

| 3 years | 5,8,15,17,20,39 | 79,979 | 1.06 | 1.02;1.09 | < 0.01 | 72.0c | 69,993 | 1.05 | 1.01;1.09 | 0.02 | 73.0c |

| 5 years | 11,16,17,19,20,38,40 | 204,668 | 1.15 | 1.00;1.33 | 0.05 | 100c | 175,602 | 1.02 | 1.01;1.03 | < 0.01 | 50.0c |

| 10 year | 17,40,43 | 258,63 | 1.08 | 1.05;1.11 | < 0.01 | 91.0c | 223,404 | 1.02 | 0.97;1.07 | 0.43 | 97.0c |

|

| |||||||||||

| General characteristics | MD-MR versus MD-FR | MD-FR versus FD-FR | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Time | Studies | Number of patients | RR | 95%CIa | pb | I2 (%)c | Number of patients | RR | 95%CIa | pb | I2 (%)c |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 year | 1,5,8,15,16,17,20,39,40 | 196,191 | 1.01 | 1.01;1.02 | < 0.01 | 67.0c | 139,859 | 1.01 | 0.99;1.02 | 0.30 | 77.0c |

| 2 years | 5,8,15,20 | 9,086 | 1.01 | 0.99;1.03 | 0.32 | 0 | 5,171 | 1.01 | 0.98;1.03 | 0.61 | 0 |

| 3 years | 5,8,15,17,20,39 | 80,495 | 1.03 | 1.00;1.06 | 0.07 | 76.0c | 51,994 | 1.01 | 1.00;1.02 | < 0.01 | 0 |

| 5 years | 11,16,17,19,20,38,40 | 189,508 | 1.00 | 0.97;1.03 | 0.98 | 91.0c | 135,798 | 1.01 | 1.00;1.03 | 0.11 | 66.0c |

| 10 year | 17,40,43 | 246,909 | 0.96 | 0.86;1.06 | 0.38 | 99.0c | 166,817 | 1.04 | 1.02;1.06 | < 0.01 | 80.0c |

|

| |||||||||||

| General characteristics | MD-FR versus FD-MR | FD-FR versus FD-MR | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Time | Studies | Number of patients | RR | 95%CIa | pb | I2 (%)c | Number of patients | RR | 95%CIa | pb | I2 (%)c |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1 year | 1,5,8,15,16,17,20,39,40 | 169,666 | 1.01 | 1.00;1.03 | 0.15 | 90.0c | 154,693 | 1.01 | 0.99;1.02 | 0.45 | 80.0c |

| 2 years | 5,8,15,20 | 5,679 | 1.05 | 1.01;1.10 | 0.01 | 36.0 | 4,496 | 1.03 | 0.99;1.07 | 0.18 | 51.0c |

| 3 years | 5,8,15,17,20,39 | 61,980 | 1.03 | 1.00;1.05 | 0.04 | 44.0c | 51,478 | 1.01 | 0.98;1.04 | 0.53 | 44.0 |

| 5 years | 11,16,17,19,20,38,40 | 164,864 | 1.18 | 1.03;1.35 | 0.02 | 100c | 150,958 | 1.14 | 0.99;1.31 | 0.07 | 100c |

| 10 year | 17,40,43 | 202,176 | 1.10 | 1.01;1.21 | 0.03 | 99.0c | 176,671 | 1.06 | 0.98;1.14 | 0.14 | 98.0c |

RR: relative risk

a Value of p < 0.10 of Z-test for all effects.

b Value of I2 > 40.0% indicates statistical heterogeneity among studies.

c Significant heterogeneity (p < 0.10).

The remaining studies were not found to have enough data for the quantitative analysis. 3 , 10 , 12 , 14 , 25 , 42 , 45 For the patient survival outcome, two studies were included in the meta-analysis. 1 , 20

The studies by Ellison et al 8 and Tan et al 40 separately evaluated transplants from living and deceased donors, and the total numbers of events and subjects in each study were included in the meta-analysis, considering living and deceased donors. In the study by Abou-Jaoude et al, 1 rates regarding general graft survival and graft survival as interrupted by death with functioning graft were calculated. The uninterrupted graft survival rate was the one used in the meta-analysis.

In the MD-MR versus FD-MR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1,03 (95%CI 1.01;1.05; p = 0.0002; I2 = 92.0%), 1.05 (95%CI 1.03;1.08; p < 0.0001; I2 = 25.0%), 1.06 (95%CI 1.02;1.09; p = 0.0008; I2 = 72.0%), 1.15 (95%CI 1.00;1.33; p = 0.05; I2 = 100%), and 1.08 (95%CI 1.05;1.11; p < 0.00001; I2 = 91.0%). The graft survival rate was significantly higher in all follow-up periods evaluated, and it favored MD-MR pair. Heterogeneity was high and significant for all periods, except for the two-year follow-up period. The patient survival analysis was only conducted for the one-year follow-up period, and no pairs were observed to be favored (RR = 0.99; 95%CI 0.96;1.02; p = 0.52; I2 = 0.0%).

In the MD-MR versus FD-FR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1.02 (95%CI 1.01;1.04; p = 0.0008; I2 = 83.0%), 1.02 (95%CI 1.00;1.04; p < 0.10; I2 = 9.0%), 1.05 (95%CI 1.01;1.09; p = 0.02; I2 = 73.0%), 1.02 (95%CI 1.01;1.03; p = 0.0004; I2 = 50.0%), and 1.02 (95%CI 0.97;1.07; p = 0.43; I2 = 97.0%). The graft survival rate was significantly higher in follow-up periods of one, three, and five years, and it favored MD-MR pair. Heterogeneity only was not significant for the two-year follow-up period. The patient survival meta-analysis was observed to favor none of the pairs (RR = 0.98; 95%CI 0.95;1.01; p = 0.21; I2 = 0%).

In the MD-MR versus MD-FR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1.01 (95%CI 1.01;1.02; p = 0.0009; I2 = 67.0%), 1.01 (95%CI 0.99;1.03; p = 0.32; I2 = 0%), 1.03 (95%CI 1.00;1.06; p = 0.07; I2 = 76.0%), 1.00 (95%CI 0.97;1.03; p = 0.98; I2 = 91.0%), and 0.96 (95%CI 0.86;1.06; p = 0.38; I2 = 99.0%). The graft survival rate was only significantly higher for the one-year follow-up period, favoring the MD-MR pair. Heterogeneity only was not significant for the two-year follow-up period. The patient survival meta-analysis was observed to favor none of the pairs (RR = 1.00; 95%CI 0.98;1.03; p = 0.86; I2 = 0%).

In the MD-FR versus FD-FR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1.01 (95%CI 0.99;1.02; p = 0.30; I2 = 77.0%), 1.01 (95%CI 0.98;1.03; p = 0.61; I2 = 0%), 1.01 (95%CI 1.00;1.02; p = 0.0007; I2 = 0%), 1.01 (95%CI 1.00;1.03; p = 0.11; I2 = 66.0%), and 1.04 (95%CI 1.02;1.06; p = 0.0003; I2 = 80.0%). The graft survival rate was significantly higher in follow-up periods of three and ten years, and it favored MD-FR pair. Heterogeneity only was not significant for the two and three-year follow-up periods. The patient survival meta-analysis was observed to favor none of the pairs (RR = 0.98; 95%CI 0.94;1.01; p = 0.19; I2 = 0%).

In the MD-FR versus FD-FR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1.01 (95%CI 1.00;1.03; p = 0.15; I2 = 90.0%), 1.05 (95%CI 1.01;1.10; p = 0.01; I2 = 36.0%), 1.03 (95%CI 1.00;1.05; p = 0.04; I2 = 44.0%), 1.18 (95%CI 1.03;1.35; p = 0.02; I2 = 100%), and 1.10 (95%CI 1.01;1.21; p = 0.03; I2 = 99.0%). The graft survival rate was significantly higher for all follow-up periods, except for the one-year one, favoring MD-FR pair. Heterogeneity was high and significant for all periods, except for the two-year follow-up period. The patient survival meta-analysis was observed to favor none of the pairs (RR = 0.99; 95%CI 0.95;1.02; p = 0.44; I2 = 0%).

In the FD-FR versus FD-MR comparison, the RRs as grouped for graft survival in a chronological order of follow-up periods of one, two, three, five, and 10 years were, respectively, 1.01 (95%CI 0.99;1.02; p = 0.45; I2 = 80.0%), 1.03 (95%CI 0.99;1.07; p = 0.18; I2 = 51.0%), 1.01 (95%CI 0.98;1.04; p = 0.53; I2 = 44.0%), 1.14 (95%CI 0.99;1.31; p = 0.07; I2 = 100%), and 1.06 (95%CI 0.98;1.14; p = 0.14; I2 = 98.0%). There were no significant differences regarding graft survival considering all follow-up periods. Heterogeneity was high and significant for all periods, except for the three-year follow-up period. The patient survival meta-analysis was observed to favor none of the pairs (RR = 1.01; 95%CI 0.97;1.06; p = 0.54; I2 = 0%).

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis evaluated the influences of donor genders, recipient genders, and the donor-recipient combination in regards to kidney transplant patient and graft survival rates.

In the comparison between donor genders, 9,022 subjects were evaluated in the meta-analysis. Donor genders were not found to favor gender rates in the evaluation of one, two, three, five, and eight-year follow-up periods (p < 0.05). Ten-year follow-up period was the only observed to differ significantly, favoring male donors (p = 0.03). The study by Muller 24 concluded that kidney grafts from male patients work better than the ones from female donors in the long run. Several studies suggest that, in those cases, the grafts from female donors are more antigenic, which may explain the lower survival rates. 22 , 30 , 31 , 36

In the comparison between recipient genders in all follow-up periods, 9,593 subjects were evaluated in the meta-analysis, and no significant differences were observed regarding graft survival. Patient survival analysis considered 747 patients. No significant differences were found among the studies. The study by Busson and Benoit 5 evaluated the influence from recipient and donor genders and the donor-recipient combination. Recipient genders were the only ones for which significant differences were not found.

The comparison between donor-recipient genders included 471,252 patients. MD-MR pair should be highlighted for having been observed to have the best results in all comparisons (MD-MR versus FD-MR, MD-MR versus FD-FR, MD-MR versus MD-FR); that is, kidney transplants from male donors to male recipients were found to have the best graft survival rates. Nonetheless, FD-MR pair was found to have the worst results (FD-MR versus MD-MR, FD-MR versus MD-FR), except for the FD-MR versus FD-FR comparison. Those results are comparable with other reviews. 7 , 44

The assessment of differences between genders is important to improve transplant results. Men and women have different biological factors, different body conditions, hormone circumstances, and immune responses, as well as different metabolic and functional demands, which can influence kidney transplant results. 44 Gender incompatibilities in FD-MR pair are argued to negatively influence graft survival due to kidney sizes and their numbers of nephrons. The ratio between graft and recipient weights is an important one. 26 , 33

Giral et al 10 analyzed the consequences from kidney mass reduction following kidney transplants, and they concluded kidney graft mass to impact glomerular filtration and proteinuria rates. The authors suggest that great kidney-to-recipient weight ratios be avoided, once that might significantly influence long-term kidney function.

That meta-analysis only included cohort studies. One of the limitations from systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational studies regards to the selection bias that is intrinsic to this study design and to uncontrolled confounding factors. Observational cohort studies are the ones conducted in the real world, under conditions uncontrolled for. In regards to that, differences were observed in the subject numbers among the groups, types of donors (living, deceased, or both), numbers of transplants, monitored periods, among others. Despite that, observational studies are observed to have the advantages of gathering a large number of patients and best representing the real world.

Another limitation in the interpretation of results was the statistical heterogeneity among studies, which was found in the meta-analyses. The small number of studies included in the comparisons, and the lack of complete, accurate information in the studies made it difficult to account for heterogeneity sources. Most studies were not observed to include immunosuppressive therapies, ages (donors and recipients), or monitored periods. The sensitivity analysis, in which studies were included and excluded for each comparison, in general, has not altered the directions of outcomes, having changes of small relevance in heterogeneity values. It has not provided information on the possible causes for heterogeneity either.

However, the results from this review can be considered for decision-making by medical teams responsible for transplants in the clinical practice, once it represents the best level of evidence regarding the topic.

Gender incompatibilities must be avoided whenever possible. Genders must be considered as criteria in the choices regarding allocation of organs from donors and to recipients. Gender combinations may make a difference in survival rates. Nonetheless, that reality is utopic in the clinical practice, due to the scarcity of donors and the increase in the number of patients on waiting lists for transplants. A change in that scenario is required in order to improve the allocation of organs.

In conclusion, recipient and donor genders, when evaluated isolatedly, do not influence patient or graft survival rates. However, combinations between donor-recipient genders may be a determining factor for graft survival, favoring MD-MR pair.

Funding Statement

Research was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG – Process APQ-00770-12) and by the Research Dean’s Office of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

Footnotes

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: version 5.1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011 [cited 2014 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connelll D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2014 [cited 2014 Feb 6]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Based on master dissertation by Erika Vieira de Almeida e Santiago, titled: “Gênero e Efetividade da terapia de manutenção entre pacientes transplantados renais, no Brasil, no período de 2001 a 2006: uma coorte histórica”, presented to the Postgraduate Program in Medications and Pharmaceutical Assistance of Faculdade de Farmácia of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, in 2014.

Research was supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG – Process APQ-00770-12) and by the Research Dean’s Office of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abou-Jaoude MM, Abou-Jaoude WJ, Almawi WY. Sex matching plays a role in outcome of kidney transplant. 10.6002/ect.2011.0205Exp Clin Transplant. 2012;10(5):466–470. doi: 10.6002/ect.2011.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avula S, Sharma RK, Singh AK, Gupta A, Kumar A, Agrawal S, et al. Age and gender discrepancies in living related renal transplant donors and recipients. 367410.1016/S0041-1345(98)01189-0Transplant Proc. 1998;30(7) doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Hamida F, Ben Abdallah T, Abdelmoula M, Mejri H, Goucha R, Abderrahim E, et al. Impact of donor/recipient gender, age, and HLA matching on graft survival following living-related renal transplantation. 10.1016/S0041-1345(99)00817-9Transplant Proc. 1999;31(8):3338–3339. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchler M, Al Najjar A, Duvallon C, Lanson Y, Bagros P, Nivet H, et al. Role of donor characteristics on long-term renal allograft survival. 234510.1016/S0041-1345(97)00394-1Transplant Proc. 1997;29(5) doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busson M, Benoit G. Is matching for sex and age beneficial to kidney graft survival? Societé Française de Transplantation and Association France Transplant. Clin Transplant. 1997;11(1):15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PD, Tsai MK, Lee CY, Yang CY, Hu RH, Lee PH, et al. Gender differences in renal transplant graft survival. 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.10.011J Formos Med Assoc. 2013;112(12):783–788. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csete M. Gender issues in transplantation. 10.1213/ane.0b013e318163feafAnesth Analg. 2008;107(1):232–238. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318163feaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellison MD, Norman DJ, Breen TJ, Edwards EB, Davies DB, Daily OP. No effect of H-Y minor histocompatibility antigen in zero-mismatched living-donor renal transplants. 10.1097/00007890-199408270-00020Transplantation. 1994;58(4):518–520. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199408270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallieni M, Mezzina N, Pinerolo C, Granata A. Sex and gender differences in nephrology. In: Oertelt-Prigione S, Regitz-Zagrosek V, editors. Sex and gender aspects in clinical medicine. New York: ꞉ Springer Science & Business Media; 2011. pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giral M, Nguyen JM, Karam G, Kessler M, Ligny BH, Buchler M, et al. Impact of graft mass on the clinical outcome of kidney transplants. 10.1681/ASN.2004030209J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):261–268. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004030209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Głyda M, Czapiewski W, Karczewski M, Pięta R, Oko A. Influence of donor and recipient gender as well as selected factors on the five-year survival of kidney graft. 10.2478/v10035-011-0029-1Pol Przegl Chir. 2011;83(4):188–195. doi: 10.2478/v10035-011-0029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GratwohL A, Döhler B, Stern M, Opelz G. H-Y as a minor histocompatibility antigen in kidney transplantation: a retrospective cohort study. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60992-7Lancet. 2008;372(9632):49–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard K, Salked G, White S, MacDonald S, Chadban S, Craig JC, et al. The cost efectiveness of increasing kidney transplantation and home-based dialysis. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01073.xNephrology(Carlton) 2009;14(1):123–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue S, Yamada Y, Kuzuhara K, Ubara Y, Hara S, Ootubo O. Are women privileged organ recipients? 10.1016/S0041-1345(02)03408-5Transplant Proc. 2002;34(7):2775–2776. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs SC, Nogueira JM, Phelan MW, Bartlett ST, Cooper M. Transplant recipient renal function is donor renal mass- and recipient gender-dependent. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00617.xTranspl Int. 2008;21(4):340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2007.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayler LK, Rasmussen CS, Dykstra DM, Ojo AO, Port FK, Wolfe RA, et al. Gender imbalance and outcomes in living donor renal transplantation in the United States. 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00086.xAm J Transplant. 2003;3(4):452–458. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SJ, Gill JS. H-Y incompatibility predicts short-term outcomes for kidney transplant recipients. 10.1681/ASN.2008101110J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(9):2025–2033. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. An estimate of lifelong costs and QALYs in renal replacement therapy based on patients’ life expectancy. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.10.002Health Policy. 2008;86(1):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon OJ, Kwak JY. The impact of sex and age matching for long-term graft survival in living donor renal transplantation. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.07.046Transplant Proc. 2004;36(7):2040–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lankarani MM, Assari S, Nourbala MH. Improvement of renal transplantation outcome through matching donors and recipients. Ann Transplant. 2009;14(4):20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W-65–W-94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier-Kriesche HU, Ojo AO, Leavy SF, Hanson JA, Leichtman AB, Magee JC, et al. Gender differences in the risk for chronic renal allograft failure. 10.1097/00007890-200102150-00016Transplantation. 2001;71(3):429–432. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200102150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moosa MR. Impact of age, gender and race on patient and graft survival following renal transplantation: developing country experience. S Afr Med J. 2003;93(9):689–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller V, Szabó A, Viklicky O, Gaul I, Portl S, Philipp T, et al. Sex hormones and gender related-differences: their influence on chronic renal allograft rejection. Kid Intern. 1999;55(5):2011–2020. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neugarten J, Srinivas T, Tellis V, Silbiger S, Greenstein S. The effect of donor gender on renal allograft survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(2):318–324. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholson ML, Windmill DC, Horsburgh T, Harris KP. Influence of allograft size to recipient body-weight ratio on the long-term outcome of renal transplantation. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01390.xBr J Surg. 2000;87(3):314–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyberg G, Blohmé I, Nordén G. Gender differences in a kidney transplant population. 10.1093/ndt/12.3.559Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(3):559–563. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oertelt-Prigione S. Sex and gender in medical literature. In: Oertelt-Prigione S, Regitz-Zagrosek V, editors. Sex and gender aspects in clinical medicine. London: Springer; 2012. pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oien CM, Reisaeter AV, Leivestad T, Dekker FW, Line PD, OS I. Living donor kidney transplantation: the effects of donor age and gender on short-and long-term outcomes. 10.1097/01.tp.0000255583.34329.ddTransplantation. 2007;83(5):600–606. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000255583.34329.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paavonen T. Hormonal regulation of immune responses. 10.3109/07853899409147900Ann Med. 1994;26(4):255–258. doi: 10.3109/07853899409147900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panajotopoulos N, Ianhez LE, Neumann J, Sabbaga E, Kalil J. Immunological tolerance in human transplantation. The possible existence of a maternal effect. 10.1097/00007890-199009000-00016Transplantation. 1990;50(3):443–445. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perovic S, Jankovic S. Renal transplantation vs hemodialysis: cost-effectiveness analysis. 10.2298/VSP0908639PVojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66(8):639–644. doi: 10.2298/vsp0908639p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poggio ED, Hila S, Stephany B, Fatica R, Krishnamurthi V, Del Bosque C, et al. Donor kidney volume and outcomes following live donor kidney transplantation. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01225.xAm J Transplant. 2006;6(3):616–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pugliese O, Quintieri F, Mattucci DA, Venettoni S, Taioli E, Costa AN. Kidney graft survival in Italy and factors influencing it. 10.7182/prtr.15.4.lt8514u040417g86Prog Transplant. 2005;15(4):385–391. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez Garcia F, Torres A, Magariño M, Wichmann I, Nuñez Roldán A. Influence of cyclosporine on sex-related differences observed in the outcome of cadaveric human-kidney allografts. Inmunologia. 1989;8(3):107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanfey H. Gender-specific issues in liver and kidney failure and transplantation: a review. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.617J Womens Health. 2005;14(7):617–626. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Oberai PC, Parekh RS, Boulware LE, Powe NR, et al. Age and comorbidities are effect modifiers of gender disparities in renal transplantation. 10.1681/ASN.2008060591J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3):621–628. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaheen FAM, Al Sulaiman M, Mousa D, El Din ABS, Hawas F, Fallatah A, et al. Impact of donor/recipient gender, age, HLA matching, and weight on short-term graft survival following living related renal transplantation. 10.1016/S0041-1345(98)01179-8Transplant Proc. 1998;30(7):3655–3658. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaheen MF, Shaheen FAM, Attar B, Elamin K, Al Hayyan H, Al Sayyari A. Impact of recipient and donor nonimmunologic factors on the outcome of deceased donor kidney transplantation. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.12.052Transplant Proc. 2010;42(1):273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan JC, Kim JP, Chertow GM, Grumet FC, Desai M. Donor-recipient sex mismatch in kidney transplantation. 10.1016/j.genm.2012.07.004Gend Med. 2012;9(5):335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valdes F, Pita S, Alonso A, Rivera CF, Cao M, Fontan MP, et al. The effect of donor gender on renal allograft survival and influence of donor age on posttransplant graft outcome and patient survival. 10.1016/S0041-1345(97)01026-9Transplant Proc. 1997;29(8):3371–3372. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)01026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vereerstraeten P, Wissing M, Pauw L, Abramowicz D, Kinnaert P. Male recipients of kidneys from female donors are at increased risk of graft loss from both rejection and technical failure. 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130205.xClin Transplant. 1999;13(2):181–186. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeier M, Dohler B, Opelz G, Ritz E. The effect of donor gender on graft survival. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000030078.74889.69J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(10):2570–2576. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000030078.74889.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou JY, Cheng J, Huang HF, Shen Y, Jiang Y, Chen JH. The effect of donor recipient gender mismatch on short- and- long term graft survival in kidney transplantation: a systematic review and meta analysis. 10.1111/ctr.12191Clin Transplant. 2013;27(5):764–771. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zukowski M, Kotfis K, Biernawska J, Zegan-Barańska M, Kaczmarczyk M, Ciechanowicz A, et al. Donor- recipient gender mismatch affects early graft loss after kidney transplantation. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.068Transplant Proc. 2011;43(8):2914–2916. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]