Abstract

Although L-asparaginase (ASP) is associated with several toxicities, its myelosuppressive effect has not been well characterized. On DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 05-01 for children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the Consolidation phase and the initial portion of the Continuation phase were identical for standard risk patients, except ASP was given only during Consolidation. Comparing the two treatment phases revealed that low blood counts during Consolidation with ASP resulted in more dosage reductions of 6-mercaptopurine and methotrexate. The myelosuppressive effect of ASP should be considered when designing treatment regimens to avoid excessive toxicity and dose reductions of other critical chemotherapy agents.

Keywords: asparaginase, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL, myelosuppression

BACKGROUND

L-asparaginase (ASP) is a universal component of treatment for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Since 1977, trials conducted by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) ALL Consortium have included 20-30 consecutive weeks of ASP treatment during post-induction consolidation and have demonstrated that this treatment significantly improves long-term event-free survival [1].

ASP is associated with multiple toxicities including hypersensitivity, pancreatitis, and thrombosis [2]. Several early reports suggested that ASP might also have a myelosuppressive effect, but this effect was not well characterized [3-6]. Subsequently, few publications have addressed this potential toxicity.

METHODS

Patient Population

From 2005-2009, 61 patients were diagnosed with standard risk (SR) ALL at Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI)/Children's Hospital Boston and treated on DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 05-01 (NCT #00400946). SR patients met all of the following criteria: 1 to <10 years of age; highest pretreatment WBC < 50,000/mm3; absence of central nervous system leukemia (defined as CNS-3); B-precursor phenotype; absence of t(9;22), MLL gene rearrangements, or hypodiploidy; and low minimal residual disease (MRD) levels as assessed by PCR at the end of the first 4 weeks of treatment [7].

The Institutional Review Board approved the protocol prior to patient enrollment. Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians before therapy started.

Therapy

Details of therapy for SR patients are shown in Table 1. During Consolidation, patients received 30 consecutive weeks of ASP, either weekly intramuscular (IM) E. coli ASP 25,000 IU/m2 weekly or intravenous (IV) PEG ASP 2,500 IU/m2 every 2 weeks in the context of a randomized trial. ASP was not given during the Continuation phase. The remainder of systemic and intrathecal chemotherapy was identical during Consolidation and the first part of Continuation (weeks 37-70). After week 70, intrathecal chemotherapy was given less frequently. Patients completed all therapy at week 108.

TABLE I.

Treatment regimen for consolidation and continuation phases

| Consolidation: Weeks 7-36 (every 3-week cycles) | Continuation: Weeks 37-70 (every 3-week cycles) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vincristine | 1.5 mg/m2/week IV on Day 1 | Same |

| Methotrexate | 30 mg/m2/week IV or IM Days 1, 8, 15 | Same |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 50 mg/m2/day by mouth Days 1-14 | Same |

| Dexamethasone | 6 mg/m2/day by mouth Days 1-5 | Same |

| Triple Intrathecal Therapy | Methotrexate, cytarabine, hydrocortisone.* Every 9 weeks. | Same |

| Asparaginase | PEG ASP 2500 IU/m2 IV every 2 weeks × 15 or E. coli ASP 25000 IU/m2 IM weekly × 30 | None |

Intrathecal therapy dosing was based on age. For methotrexate, cytarabine, and hydrocortisone, respective dosing was 8mg, 20 mg, and 9mg for patients 1-1.99 years old; 10 mg, 30 mg, and 12 mg for patients 2-2.99 years old; and 12 mg, 40 mg, and 15 mg for patients 3 years and older.

The starting doses of 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) and methotrexate (MTX) were 50 mg/m2/day and 30 mg/m2/week, respectively. Chemotherapy cycles were given every 21 days during Consolidation and Continuation. 6-MP and MTX doses were adjusted (by increments of 10-20%) at the start of each cycle to maintain absolute phagocyte count (APC) nadirs above 500/mm3 and platelet nadirs above 75,000. Chemotherapy cycles were delayed until APC was greater than 1000/mm3 and platelets were greater than 100,000.

Medical Record Review

Medical records of all 61 SR patients were reviewed to ascertain the dose modifications of MTX and 6MP made due to low or high blood counts (APC and/or platelets). Delays in starting cycles (defined as ≥25 day interval between cycles) were recorded. Bacterial and fungal infections were also documented. Data from all Consolidation and Continuation cycles through week 70 were included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were constructed to model binary outcomes with repeated measures and account for within-subject correlation. An exchangeable correlation matrix was used in each model. Outcomes of these models included the number of low or high count dose modifications and the number of treatment delays during weeks 7-70. The interaction of phase or randomization arm and time was also considered for each model. Wald P values are reported along with the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from the regression models and were considered significant if < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 61 SR patients, age at diagnosis ranged from 1 to 9 years (median, 3.9) and 57% were female. Twenty-seven patients were randomized to receive IM E. coli ASP, 29 to IV PEG ASP, and five declined randomization (and were directly assigned to IM E. coli ASP). A total of 1,270 chemotherapy cycles were evaluated longitudinally, 501 during Consolidation and 769 during weeks 37-70 of Continuation.

No difference in delays or dose modification for abnormal blood counts was detected between ASP randomization arms in either Consolidation or Continuation, so data regarding myelosuppression during Consolidation from all groups of patients (randomized IV PEG ASP, randomized IM E.coli ASP, directly assigned IM E.coli ASP) were pooled together for all subsequent analyses.

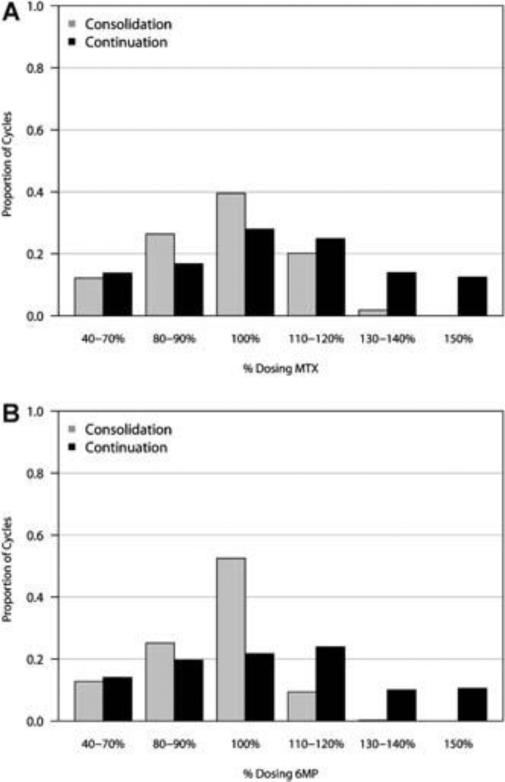

There was a higher proportion of cycles modified for low blood counts (ie, dose reduction of MTX and/or 6MP) during Consolidation compared to Continuation (24% vs 9%, OR = 2.09 [95% CI 1.11, 3.96]; p = 0.02). There was a lower proportion of cycles modified due to high blood counts (ie, dose escalation of MTX and/or 6MP) during Consolidation compared to Continuation (20% vs 43%, OR =0.47 [95% CI 0.29, 0.76]; p =0.002). Figure 1 summarizes the dosing of MTX and 6-MP during Consolidation and Continuation. During Consolidation, the proportion of cycles in which patients received escalated doses of MTX was 22% compared to 51% during Continuation. Similarly, the proportion of cycles in which patients received escalated doses of 6-MP was 10% in Consolidation compared to 45% in Continuation. Treatment delays were more common during Consolidation than Continuation (17% vs 9%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (OR =1.52 [95% CI 0.76, 3.06); p=0.24). A higher proportion of patients had documented episodes of bacteremia during Consolidation compared with Continuation (15% vs 2%), while very few patients experienced an invasive fungal infection in either phase (0% vs 2%). Because infections can sometimes lead to myelosuppression, we repeated GEE modeling for dose modifications and treatment delays between Consolidation II and Continuation excluding the 14 patients who experienced an infection and found no significant differences compared to the entire cohort.

A: Dosing of methotrexate during post-induction chemotherapy cycles. Starting dose of methotrexate for all patients was 30 mg/m2/week (100% dose). Methotrexate doses were subsequently kept the same, reduced (40–90% of starting dose), or escalated (110–150% of starting dose) depending on blood counts during the previous 21-day chemotherapy cycle. B: Dosing of 6-mercaptopurine during post-induction chemotherapy cycles. Starting dose of 6-mercaptopurine for all patients was 50 mg/m2/day (100% dose) for days 1–14 days of every 3-week cycle. 6-MP doses were subsequently kept the same, reduced (40–90% of starting dose), or escalated (110–150% of starting dose) depending on blood counts during the previous 21-day chemotherapy cycle.

DISCUSSION

During Consolidation, when patients received ASP, blood counts were lower than during the initial portion of Continuation (no ASP), despite an otherwise identical schedule of other systemic and intrathecal drugs. Because of low blood counts, patients received lower doses of MTX and 6MP during Consolidation. These results suggest a myelosuppressive role for ASP which was independent of type (native E.coli ASP or PEG ASP). The rate of bacteremia was also higher during treatment with ASP.

These results are in accord with early reports of ASP in the treatment of ALL [3-5]. Early trials demonstrated that the addition of ASP to induction therapy with prednisolone and vincristine resulted in lower neutrophil counts at days 7 and 14 of induction and a higher incidence of induction death [6]. More recently, a comparison of two clinical trials conducted by the Pediatric Oncology Group suggested that intensified treatment with ASP led to myelosuppression and an increased risk of infection. Comparisons between the trials are limited, however, as toxicities were defined differently [9].

The underlying mechanism for ASP-associated myelosuppression is unknown. ASP could cause myelosuppression directly or secondarily by potentiating the myelosuppressive effects of other chemotherapy agents. For instance, ASP may change the pharmacokinetics of MTX and 6-MP through an effect on hepatic metabolism. Also, ASP-induced hypoproteinemia may lead to higher free drug levels of other chemotherapeutic agents, as has been hypothesized by others [10]. Further investigation is needed to understand the effect of ASP on the pharmacokinetics of other chemotherapy agents and to elucidate a precise mechanism for ASP-associated myelosuppression.

In conclusion, the myelosuppressive effect of ASP should be considered when designing regimens for patients with ALL which combine ASP with other chemotherapeutic drugs in order to minimize toxicity, infections, and excessive dose reductions and treatment delays.

References

- 1.Silverman LB, Stevenson KE, O'Brien JE, et al. Long-term results of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium protocols for children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1985-2000). Leukemia. 2010;24:320–334. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Earl M. Incidence and management of asparaginase-associated adverse events in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. Sep. 2009;7(9):600–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oehlers MJ, Fetawadjieff W, Woodliff HJ. Profound leukopenia following asparaginase treatment in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Med J Aust. 1969;2:907–909. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1969.tb107492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolarz G, Pietschmann H. Leukocyte alterations during asparaginase therapy. Wien Med Wschr. 1971;121:196–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorie YI, Kruglova GV, Poddubnaia IV, et al. Investigations with L-asparaginase therapy in malignant hematologic diseases. Klin Med (Moskva) 1973;51:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston PGB, Hardisty RM, Kay HEM, et al. Myelosuppressive effect of colaspase (L-asparaginase) in initial treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br Med J. 1974;3:81–83. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5923.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou J, Goldwasser MA, Li A, et al. Quantitative analysis of minimal residual disease predicts relapse in children with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia in DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 95-01. Blood. 2007;110:1607–1611. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman LB, Stevenson K, Vrooman LM, et al. Randomized Comparison of IV PEG and IM E. Coli Asparaginase in Children and Adolescents with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Results of the DFCI ALL Consortium Protocol 05-01. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2011;118 Abstract 874. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salzer WL, Devidas M, Shuster JJ, et al. Intensified PEG-L-asparaginase and antimetabolite-based therapy for treatment of higher risk precursor-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. Jun. 2007;29(6):369–75. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180640d54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amylon MD, Shuster J, Pullen J, et al. Intensive high-dose asparaginase consolidation improves survival for pediatric patients with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and advanced stage lymphoblastic lymphoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 1999;13:335–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]