Abstract

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that is the leading cause of iatrogenic infections in critically ill patients, especially those undergoing mechanical ventilation. In this study, we investigated the effects of the universal signaling molecule autoinducer-2 (AI-2) in biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Results

The addition of 0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM exogenous AI-2 to P. aeruginosa PAO1 increased biofilm formation, bacterial viability, and the production of virulence factors. However, compared to the 10 nM AI-2 group, higher concentrations of AI-2 (100 nM and 1 μM) reduced biofilm formation, bacterial viability, and the production of virulence factors. Consistent with the changes in morphology, gene expression analysis revealed that AI-2 up-regulated the expression of quorum sensing-associated genes and genes encoding virulence factors at lower concentrations and down-regulated these genes at higher concentrations.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that exogenous AI-2 acted in a dose-dependent manner to regulate P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence factors secretion via modulating the expression of quorum sensing-associated genes and may be targeted to treat P. aeruginosa biofilm infections.

Keywords: Autoinducer-2, Quorum sensing, Biofilm, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a well-known opportunistic pathogen associated with various acute and chronic infections in humans, especially in those who are immunocompromised. P. aeruginosa infections can be difficult to eradicate because P. aeruginosa is capable of forming biofilms, which are more resistant to physical or chemical attacks than planktonic bacteria, leading to high morbidity and mortality among infected patients [1, 2]. P. aeruginosa could produce a number of virulence factors, such as pyocyanin, rhamnolipids, elastase, exotoxin A, phospholipase C, and exoenzyme S, which are thought to be involved in acute or chronic infections [3].

Quorum sensing (QS) is a cell-to-cell signaling system that refers to the ability of bacteria to respond to small signaling molecules secreted by various microbial species. When the amount of QS signaling molecules accumulates to a threshold, the QS system is activated upon the identification of extracellular receptors. As typical QS signaling molecules, oligopeptides are often produced by Gram-positive bacteria, while N-acyl homoserine lactones are often produced by Gram-negative bacteria [4]. P. aeruginosa employs three interconnected QS systems, namely, las, rhl, and pqs, to control the expression of important virulence factors, and these factors play a crucial role in the development of biofilms [5]. Therefore, the QS system can be a suitable target for antimicrobial therapy. Numerous anti-infectious approaches against P. aeruginosa biofilms have been investigated during the past decade, such as antibiotic combinations [6] and some metal chelators exerting bactericidal and antibiofilm activities [7, 8]. However, the use of large numbers of antibiotics leads to a high prevalence of bacterial resistance, and the stability of metal chelators remains to be elucidated. Currently, chemical compounds that inhibit QS systems are being gradually investigated [9, 10].

Autoinducer-2 (AI-2) is a universal QS molecule that mediates intra- and interspecies communication. This molecule is formed from spontaneous rearrangement of 4, 5-dihydroxy-2, 3-pentanedione (DPD), which is produced by the enzyme LuxS, and is the primary QS molecule produced by many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. AI-2 has been shown to play a pivotal role in the life cycle of biofilms, including the initial bacterial aggregation and the production of virulence factors [11]. Previously, Duan et al. [12] and Roy et al. [13] found that AI-2 and AI-2 analogs had an impact on P. aeruginosa virulence, but the mechanism is not clear. Because P. aeruginosa is unable to produce AI-2 [12], the molecule might act as a parainducer, which can be sensed by the bacteria and thus affect its function. An example is reported in the study conducted by Geier et al., where AI-2 increased biofilm formation by Mycobacterium avium, which also cannot produce AI-2 [14].

In addition, we found high constituent ratios of Klebsiella spp. and Streptococcus spp. in the tracheal aspirates of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) neonates [15], and P. aeruginosa is a common cause of VAP. Thus, we speculated that these AI-2 producers may facilitate biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa. In this study, we added different concentrations of synthetic AI-2 to P. aeruginosa PAO1 and evaluated biofilm formation and the production of virulence factors, with an emphasis on the underlying mechanisms of AI-2 using transcriptional analysis.

Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

P. aeruginosa wild-type PAO1 was kindly provided by Professor Li Shen (Institute of Molecular Cell and Biology, New Orleans, LA, USA). It was routinely grown and maintained on Luria–Bertani (LB) plates or in LB broth at 37 °C with agitation (200 rpm). Chemically synthesized AI-2 precursor DPD [(S)-4, 5-dihydroxy-2, 3-pentanedione] was purchased from Omm Scientific (Dallas, TX, USA).

Growth assays

Growth of PAO1 in the presence of 0.1 nM, 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM, and 1 μM AI-2 was measured at 600 nm at intervals of 2 h up to 24 h with a spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) [16]. All experiments were performed three times independently.

Biofilm formation assay

A static biofilm formation assay was performed in 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates as previously described with slight modifications [17]. In brief, cells from overnight cultures were standardized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.05. Two hundred microliters of the diluted cultures and various concentrations of AI-2 were added to 96-well microtiter plates (Costar, USA). After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C without agitation, the medium was discarded, and the plates were gently washed three times with 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Then, the plates were air dried and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet for 5 min at room temperature. Unattached stain was removed, and the plates were washed three times with PBS. The bacteria-bound crystal violet was dissolved in 200 μL 95 % ethanol, and the absorbance was determined at 570 nm in the microplate reader.

Biofilm viability

P. aeruginosa PAO1 cells were inoculated in LB broth at an initial OD600 of 0.05 and added to a sterile 24-well plate containing glass coverslips (Costar, USA) on which various concentrations of AI-2 were applied. Cultures were grown for 24 h without agitation at 37 °C. Coverslips were then rinsed three times with PBS and subsequently sonicated for 1 min (Tomy UD-201, Tokyo, Japan) and vortexed for 1 min at room temperature. Bacteria were harvested, enumerated by serial dilutions, and plated on LB agar. Plates were incubated at 37 °C, and bacterial counts were determined after 24 h.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms were established in 24-well plates as mentioned earlier. Cultures were grown for 48 h without agitation at 37 °C. Coverslips were then washed and stained with SYTO9/propidium iodide according to the manufacturer’s instructions of the L13152 LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen Molecular Probes, USA). After staining for 15 min in the dark, biofilms were washed with sterile PBS to remove the planktonic dyes and bacteria, and then biofilms were visualized by excitation with an argon laser at 488 nm (emission: 515 nm) and 543 nm (emission: 600 nm) under a Nikon A1R laser confocal microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Live bacteria were stained green while dead bacteria were stained red.

Virulence factor assays

For the pyocyanin assay, overnight cultures were standardized to an OD600 of 0.5 and diluted 1:10 in pyocyanin production broth (PPB; 2 % proteose peptone [Oxoid, UK], 1 % K2SO4, 0.3 % MgCl2 · 6H2O) after growth in LB medium. A 5-mL sample of diluted culture with various concentrations of AI-2 was grown in PPB for 24 h and then extracted with 3 mL chloroform. The blue layer was re-extracted into 1 mL 0.2 M HCl, yielding a red solution. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm, and the pyocyanin concentration was determined by multiplying this measurement by 17.07 [18]. Elastase activity was measured using the elastin-Congo red (ECR) assay as previously described with moderate modifications [16]. Briefly, overnight cultures were standardized to an OD600 of 0.5 and diluted 1:10 in peptone tryptic soy broth (PTSB; 5 % peptone, 0.1 % tryptic soy broth) after growth in LB medium. A 5-mL sample of diluted cultures with and without various concentrations of AI-2 was grown in PTSB for 6 h, and 100 μL filtered supernatant was added to 5-mL tubes containing 10 mg of ECR (Sigma, USA), 900 μL 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5), and 1 mM CaCl2. The tubes were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with shaking (250 rpm), followed by centrifugation to remove unreacted substrate. The absorbance at 495 nm was measured.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Overnight cultures of PAO1 at an initial OD600 of 0.05 were washed and then inoculated into fresh LB medium supplemented with various concentrations of AI-2 (0.1 nM to 1 μM) at an initial OD600 of 0.05. Cultures were grown at 37 °C with agitation for 24 h. Total RNA was extracted and purified using the TaKaRa Minibest Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of extracted total RNA was determined by ultraviolet absorption (260/280 nm) using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The first-strand cDNA was generated from a purified mRNA sample using a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa). Real-time PCR was carried out using the SsoFast Evagreen Supermix Kit (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with a Bio-Rad Real-Time PCR instrument. The reaction procedure was performed as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 5 s, and a final melting curve analysis from 65 °C to 95 °C, with increments of 0.5 °C every 5 s. Real-time PCR amplifications were conducted in triplicate.

Primer sequences for P. aeruginosa QS genes and virulence genes were used as described previously (Table 1). The ribosomal gene rpsL was chosen as a housekeeping gene to normalize the qRT-PCR data and to calculate the relative fold changes in gene expression. Amplification profiles were analyzed using Bio-Rad Manager Software, and cycle threshold (Ct) values for each target gene were normalized to the geometric mean of the Ct of rpsL amplified from the corresponding sample. The fold change of target genes for each group with respect to the control group was calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Table 1.

PCR primers for real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Primer direction | Sequence(5’-3’) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lasI | Forward | GGCTGGGACGTTAGTGTCAT | 104 |

| Reverse | AAAACCTGGGCTTCAGGAGT | ||

| lasR | Forward | ACGCTCAAGTGGAAAATTGG | 111 |

| Reverse | TCGTAGTCCTGGCTGTCCTT | ||

| rhlI | Forward | AAGGACGTCTTCGCCTACCT | 130 |

| Reverse | GCAGGCTGGACCAGAATATC | ||

| rhlR | Forward | CATCCGATGCTGATGTCCAACC | 101 |

| Reverse | ATGATGGCGATTTCCCCGGAAC | ||

| lasA | Forward | GCGCGACAAGAGCGAATAC | 94 |

| Reverse | CGGCCCGGATTGCAT | ||

| lasB | Forward | AGACCGAGAATGACAAAGTGGAA | 81 |

| Reverse | GGTAGGAGACGTTGTAGACCAGTTG | ||

| phzH | Forward | TGCGCGAGT TCAGCCACCTG | 214 |

| Reverse | TCCGGGACATAGTCGGCGCA | ||

| rhlA | Forward | TGGCCGAACATTTCAACGT | 107 |

| Reverse | GATTTCCACCTCGTCGTCCTT | ||

| rpsL | Forward | GCAACTATCAACCAGCTGGTG | 231 |

| Reverse | GCTGTGCTCTTGCAGGTTGTG |

Statistical analysis

Continuous data from this study were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Independent unpaired data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. One-way analysis of variance was used for multi-group comparisons. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

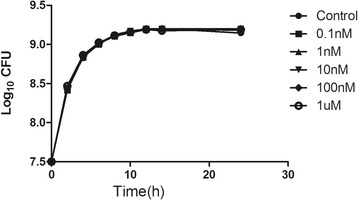

Effects of AI-2 on P. aeruginosa growth

To test the impact of AI-2 on P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and virulence, we first investigated its effect on planktonic bacterial growth. The 1-μM concentration of AI-2 did not influence the growth of the planktonic cultures (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of AI-2 on planktonic growth of P. aeruginosa PAO1. Cells were grown in LB medium, in the presence of different concentrations of AI-2 (0.1nM, 1nM, 10nM, 100nM and 1 μM). The data represent mean values of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means

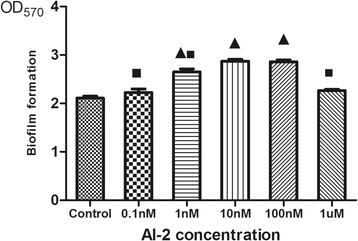

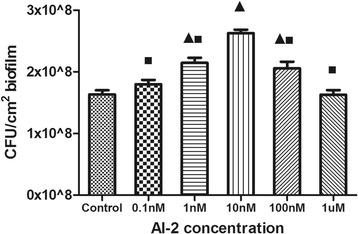

Effects of AI-2 on biofilm formation

A dose-dependent effect of AI-2 on the biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa PAO1 was observed as demonstrated in Fig. 2. Biofilm formation increased in the presence of 0.1 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM AI-2 with a 1.1-, 1.3-, and 1.4-fold increase in biofilm biomass compared to the negative control. It should be noted that 10 nM AI-2 had the greatest impact on P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation (P < 0.05). However, higher concentrations (100 nM and 1 μM AI-2) resulted in a lower biofilm biomass increase than 10 nM AI-2.

Fig. 2.

Effects of AI-2 on P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation. Biofilm formation was assessed by crystal violet after static incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. Error bars represent SEM and all experiments were performed in triplicate with three independent assays; Triangles denote a statistically significant difference from the control (P < 0.05). Squares denote a statistically significant difference from the 10nM AI-2 group (P < 0.05)

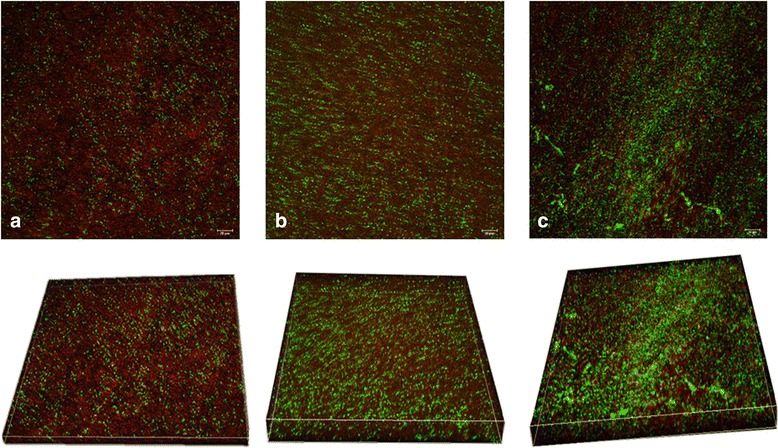

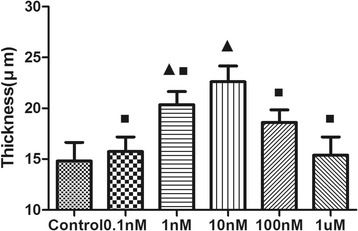

Consistent findings were also demonstrated by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Increased AI-2 concentrations led to increased biofilm formation and the promotion of the three-dimensional structure of the biofilm (Fig. 3). A dense and compact biofilm was observed in the 10 nM AI-2 group, and the number of viable bacteria in the control was less than that in the 1 nM and 10 nM AI-2 groups. Furthermore, the biofilm thickness in the 1 nM and 10 nM AI-2 groups was significantly increased compared with that in the control group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Confocal laser scanning micrographs of 2-day P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms treated under different concentrations of AI-2 (×400). Bacterial viability was determined using L13152 LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit. a No exposure to AI-2; b Exposure to 1nM AI-2; c Exposure to 10nM AI-2. Cells staining red are considered dead while cells staining green are viable cells. The scale bar represents 20 μm

Fig. 4.

Comparison of biofilm thickness under different concentrations of AI-2. Data represent the average of three image stacks collected from randomly selected areas. Triangles denote a statistically significant difference from the control (P < 0.05). Squares denote a statistically significant difference from the 10nM AI-2 group (P < 0.05)

Biofilm viability

The mean number of bacteria recovered from the biofilms (Fig. 5) in the 1 nM AI-2 group (2.16 × 108 cfu/cm2), 10 nM AI-2 group (2.64 × 108 cfu/cm2), and 100 nM AI-2 group (2.05 × 108 cfu/cm2) was significantly greater than that in the control group (1.62 × 108 cfu/cm2) (P < 0.05). However, the mean number of bacteria in the 0.1 nM AI-2 group (1.8 × 108 cfu/cm2) and the 1 μM AI-2 group (1.66 × 108 cfu/cm2) was slightly greater than that in the control group, but the increase was not significant (P > 0.05). These results were consistent with biofilm morphology changes and suggest that AI-2 increases the viability of P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms.

Fig. 5.

Enumeration of viable bacteria under different concentrations of AI-2. Data represent the means and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Triangles denote a statistically significant difference from the control (P < 0.05). Squares denote a statistically significant difference from the 10nM AI-2 group (P < 0.05)

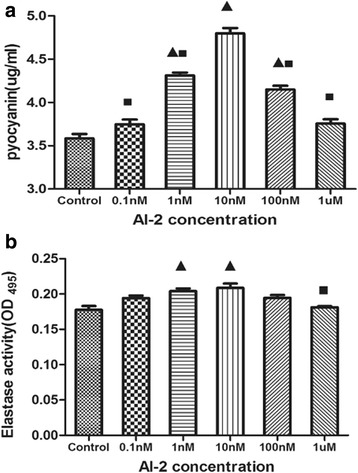

Induction of virulence factor production

To study the impact of AI-2 on P. aeruginosa virulence, two important factors, namely pyocyanin and elastase, which are controlled by QS were measured [19]. The activity of both pyocyanin and elastase in PAO1 were increased by AI-2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6a and b). A significant increase (P < 0.05) in pyocyanin and elastase production was observed in the presence of 1 nM and 10 nM AI-2.

Fig. 6.

Effects of AI-2 on the production of virulence factors of Pnn aeruginosa PAO1. a Relative productions of virulence factors of pyocyanin. b Elastase activity. Triangles denote a statistically significant difference from the control (P < 0.05). Squares denote a statistically significant difference from the 10nM AI-2 group (P < 0.05)

Gene expression analysis with qRT-PCR

QS is the most important regulator of biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa. To investigate whether the effect of AI-2 on the virulence of P. aeruginosa was the result of interference with QS, qRT-PCR was used to monitor the expression of QS-associated genes. The mRNA level of QS genes and virulence genes of P. aeruginosa biofilms, including rhlI, rhlR, lasI, lasR (QS-associated genes), lasA (encoding protease), lasB (encoding elastase), phzH (encoding pyocyanin), and rhlA (encoding rhamnosyltransferase), increased with increasing AI-2 concentrations (from 0 to 10 nM) and decreased with 100 nM and 1 μM AI-2 (Table 2), which was consistent with the morphology changes. Especially, with 10 nM AI-2, the expression of lasI, lasR, rhlI, rhlR, lasA, lasB, phzH, and rhlA was increased by 2.3-, 1.1-, 1.3-, 2.5-, 10-, 11-, 9.5-, and 3.7-fold, respectively; these increases were statistically significant when normalized to a control gene (P < 0.05). These results indicated that exogenous AI-2 could up-regulate the expression of QS-associated genes of P. aeruginosa PAO1.

Table 2.

QS and virulence genes regulated by AI-2 of P. aeruginosa biofilm

| Gene | Fold change in expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 nM | 1 nM | 10 nM | 100 nM | 1 μM | |

| lasI | 1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2* | 3.3 ± 0.2* | 2.2 ± 0.18* | 2 ± 0.2* |

| lasR | 1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.16 | 2.1 ± 0.23* | 1.3 ± 0.16 | 1.3 ± 0.2 |

| rhlI | 1 | 1.5 ± 0.17 | 2.1 ± 0.1* | 2.3 ± 0.13* | 1.7 ± 0.16 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| rhlR | 1 | 2.1 ± 0.2* | 3.4 ± 0.3* | 3.5 ± 0.24* | 2.2 ± 0.13* | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| lasA | 1 | 4.3 ± 0.16* | 5.1 ± 0.27* | 11 ± 0.21* | 4 ± 0.21* | 3 ± 0.18* |

| lasB | 1 | 4 ± 0.14* | 5.8 ± 0.45* | 12.7 ± 1.7* | 5 ± 0.15* | 2.8 ± 0.13* |

| phzH | 1 | 3.6 ± 0.34* | 5.8 ± 0.67* | 10.6 ± 0.7* | 3.8 ± 0.16* | 3.3 ± 0.22* |

| rhlA | 1 | 2.2 ± 0.16* | 3.7 ± 0.33* | 4.8 ± 0.56* | 2.3 ± 0.14* | 2.1 + 0.14* |

Values marked with an asterisk (*) indicate that the fold change of relative gene expression level of P. aeruginosa PAO1 in the presence of different concentrations of AI-2 was significantly different from negative control at P < 0.05

Discussion

P. aeruginosa is a prevalent environmental bacterium that is responsible for various recalcitrant infections in humans. It is also one of the most prevalent isolates in sputum samples of neonates with VAP [20]. In this study, we demonstrated that AI-2 induced virulence factor production, biofilm biomass, and bacterial viability of P. aeruginosa PAO1 in a dose-dependent manner, and AI-2 did not impact its planktonic growth. Furthermore, AI-2 influenced the expression of QS-associated genes (e.g., lasI, lasR, rhlI, and rhlR). This indicated that AI-2 affected the virulence of P. aeruginosa by inducing the activity of the QS systems.

Although the role of AI-2 as a general bacterial signaling molecule is yet to be completely unraveled, AI-2 is known to be involved in biofilm formation. AI-2 inhibits biofilm formation in Bacillus cereus [21], Candida albicans [22], and Eikenella corrodens [23], and it promotes biofilm formation in Escherichia coli [24], Streptococcus mutans [25], and multispecies biofilms between the two oral bacteria Streptococcus gordonii and Porphyromonas gingivalis [26]. The addition of exogenous AI-2 to P. aeruginosa biofilms increased biofilm formation, indicating that P. aeruginosa responds to the molecule. This study revealed that AI-2 can be a parainducer as a QS molecule regulating P. aeruginosa biofilms.

A similar concentration-dependent effect of AI-2 on biofilm formation has been reported for Streptococcus suis [27], Bacillus cereus [21], Streptococcus oralis [28], and Mycobacterium avium [14]. A previous study by Duan et al. [12] demonstrated that AI-2 was detected in sputum samples from patients with cystic fibrosis, and AI-2 regulated gene expression patterns and pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa. However, the mechanism is not known. In addition, Duan et al. found that the important virulence genes lasA and exotoxin genes exoS and exoY were not regulated by AI-2. This phenomenon may be attributed to the too high or too low concentration of AI-2 because our results showed that the lasA gene was affected by AI-2. Furthermore, we found that in vitro co-culture of the AI-2 producer Streptococcus mitis and P. aeruginosa PAO1 promoted P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation at certain concentrations (data not shown). It also has been suggested that the LuxS enzyme regulates metabolic processes in a large range of bacteria [29, 30]. In the present study, we found that AI-2 regulated the metabolic rate of cells in P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilms. First, more viable cells were observed in the AI-2 group by confocal laser scanning microscopy, and plating experiments revealed that the bacterial reproduction of the AI-2 group is faster than that of the control group. Second, the rhl QS system is a metabolic regulator for P. aeruginosa [31]. In this study, the increased expression levels of the rhlI and rhlR genes, which are related to bacterial metabolism, may lead to increased biofilm formation and metabolic rate as the concentration of AI-2 increased.

AI-2 is a cell-signaling regulator of P. aeruginosa. It contributes substantially to the biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa and plays an important role in the pathogenesis of P. aeruginosa infections. This phenomenon may be due to the up-regulation of QS genes and virulence factor genes such as lasB, lasA, and phzH, which mediate the production of virulence factors. In fact, up-regulated transcription of autoinducer synthase (lasI and rhlI) and their cognate receptor (lasR and rhlR) genes may be responsible for the induction of PAO1 biofilm formation and secretion of elastase and pyocyanin because QS genes also mediate virulence factor genes.

Conclusions

Taken together, this study demonstrated that AI-2 increased P. aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm formation, bacterial viability, and virulence production in a dose-dependent manner. Possible mechanisms responsible for the effect of AI-2 may involve the up-regulation of QS systems. Our results support the significance of intercellular signaling in bacterial survival strategies and emerging views on interference with bacterial signaling as a novel means of combating P. aeruginosa infections.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Yu He for his valuable advice to the linguistic revision of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81370744), the fund from Ministry of Education (No.X3387),the Scientific Research Foundation of Chongqing Municipal Health Bureau (Grant No:2013-2-051), the Scientific Research Foundation of The science and Technology Commission of Chongqing (Grant No: cstc2015jcyjA10089) and National Science and Technology Support Project (2012BAI04B05).

Abbreviations

- AI-2

Autoinducer-2

- AHL

Acyl homoserine lactones

- DPD

4, 5-dihydroxy-2, 3-pentanedione

- ECR

Elastin-Congo red

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PI

Propidium iodide

- PPB

Pyocyanin production broth

- QS

Quorum sensing

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LHD and YJL conceived and designed the study, LHD performed the study, WZL, FYK and AQ analyzed and interpreted the data, LHD and LXY wrote the manuscript. LHD, LXY and DY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Hongdong Li, Email: 413745308@qq.com.

Xingyuan Li, Email: 434437163@qq.com.

Zhengli Wang, Email: 937461502@qq.com.

Yakun Fu, Email: 15123231768@qq.com.

Qing Ai, Email: 274756349@qq.com.

Ying Dong, Email: doy1122@126.com.

Jialin Yu, Email: yujialin468@163.com.

References

- 1.Brennan AL, Geddes DM. Cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15(2):175–182. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200204000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciofu O, Fussing V, Bagge N, Koch C, Hoiby N. Characterization of paired mucoid/non-mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Danish cystic fibrosis patients: antibiotic resistance, beta-lactamase activity and RiboPrinting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48(3):391–396. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Haj Khalifa A, Moissenet D, Vu Thien H, Khedher M. Virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and modes of regulation. Ann Biol Clin (Paris) 2011;69(4):393–403. doi: 10.1684/abc.2011.0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MB, Bassler BL. Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janjua HA, Segata N, Bernabo P, Tamburini S, Ellen A, Jousson O. Clinical populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from acute infections show a wide virulence range partially correlated with population structure and virulence gene expression. Microbiology. 2012;158(Pt 8):2089–2098. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.056689-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrmann G, Yang L, Wu H, Song Z, Wang H, Hoiby N, et al. Colistin-tobramycin combinations are superior to monotherapy concerning the killing of biofilm Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(10):1585–1592. doi: 10.1086/656788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjarnsholt T, Kirketerp-Moller K, Kristiansen S, Phipps R, Nielsen AK, Jensen PO, et al. Silver against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. APMIS. 2007;115(8):921–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemire JA, Harrison JJ, Turner RJ. Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(6):371–384. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentzer M, Wu H, Andersen JB, Riedel K, Rasmussen TB, Bagge N, et al. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence by quorum sensing inhibitors. EMBO J. 2003;22(15):3803–3815. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scutera S, Zucca M, Savoia D. Novel approaches for the design and discovery of quorum-sensing inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2014;9(4):353–366. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2014.894974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vendeville A, Winzer K, Heurlier K, Tang CM, Hardie KR. Making ‘sense’ of metabolism: autoinducer-2, LuxS and pathogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(5):383–396. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan K, Dammel C, Stein J, Rabin H, Surette MG. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression by host microflora through interspecies communication. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(5):1477–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy V, Meyer MT, Smith JA, Gamby S, Sintim HO, Ghodssi R, et al. AI-2 analogs and antibiotics: a synergistic approach to reduce bacterial biofilms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97(6):2627–2638. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geier H, Mostowy S, Cangelosi GA, Behr MA, Ford TE. Autoinducer-2 triggers the oxidative stress response in Mycobacterium avium, leading to biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(6):1798–1804. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02066-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu W, Yu J, Ai Q, Liu D, Song C, Li L. Increased constituent ratios of Klebsiella sp., Acinetobacter sp., and Streptococcus sp. and a decrease in microflora diversity may be indicators of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective study in the respiratory tracts of neonates. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang YX, Xu ZH, Zhang YQ, Tian J, Weng LX, Wang LH. A new quorum-sensing inhibitor attenuates virulence and decreases antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Microbiol. 2012;50(6):987–993. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-2149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarkar R, Chaudhary SK, Sharma A, Yadav KK, Nema NK, Sekhoacha M, et al. Anti-biofilm activity of Marula - a study with the standardized bark extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;154(1):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kong KF, Jayawardena SR, Indulkar SD, Del Puerto A, Koh CL, Hoiby N, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional factor that regulates expression of AmpC and PoxB beta-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(11):4567–4575. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4567-4575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith KM, Bu Y, Suga H. Induction and inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing by synthetic autoinducer analogs. Chem Biol. 2003;10(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng C, Li X, Zou Y, Wang J, Wang J, Namba F, et al. Risk factors and pathogen profile of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a neonatal intensive care unit in China. Pediatr Int. 2011;53(3):332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2011.03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Auger S, Krin E, Aymerich S, Gohar M. Autoinducer 2 affects biofilm formation by Bacillus cereus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(1):937–941. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.937-941.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachtiar EW, Bachtiar BM, Jarosz LM, Amir LR, Sunarto H, Ganin H, et al. AI-2 of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans inhibits Candida albicans biofilm formation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:94. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azakami H, Teramura I, Matsunaga T, Akimichi H, Noiri Y, Ebisu S, et al. Characterization of autoinducer 2 signal in Eikenella corrodens and its role in biofilm formation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006;102(2):110–117. doi: 10.1263/jbb.102.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez Barrios AF, Zuo R, Hashimoto Y, Yang L, Bentley WE, Wood TK. Autoinducer 2 controls biofilm formation in Escherichia coli through a novel motility quorum-sensing regulator (MqsR, B3022) J Bacteriol. 2006;188(1):305–316. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.1.305-316.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida A, Ansai T, Takehara T, Kuramitsu HK. LuxS-based signaling affects Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(5):2372–2380. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2372-2380.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNab R, Ford SK, El-Sabaeny A, Barbieri B, Cook GS, Lamont RJ. LuxS-based signaling in Streptococcus gordonii: autoinducer 2 controls carbohydrate metabolism and biofilm formation with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(1):274–284. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.274-284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Yi L, Zhang Z, Fan H, Cheng X, Lu C. Biofilm formation, host-cell adherence, and virulence genes regulation of Streptococcus suis in response to autoinducer-2 signaling. Curr Microbiol. 2014;68(5):575–580. doi: 10.1007/s00284-013-0509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rickard AH, Palmer RJ, Jr, Blehert DS, Campagna SR, Semmelhack MF, Egland PG, et al. Autoinducer 2: a concentration-dependent signal for mutualistic bacterial biofilm growth. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60(6):1446–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winzer K, Hardie KR, Burgess N, Doherty N, Kirke D, Holden MT, et al. LuxS: its role in central metabolism and the in vitro synthesis of 4-hydroxy-5-methyl-3(2H)-furanone. Microbiology. 2002;148(Pt 4):909–922. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doherty N, Holden MT, Qazi SN, Williams P, Winzer K. Functional analysis of luxS in Staphylococcus aureus reveals a role in metabolism but not quorum sensing. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(8):2885–2897. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.2885-2897.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassett DJ, Cuppoletti J, Trapnell B, Lymar SV, Rowe JJ, Yoon SS, et al. Anaerobic metabolism and quorum sensing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in chronically infected cystic fibrosis airways: rethinking antibiotic treatment strategies and drug targets. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(11):1425–1443. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]