Abstract

The original hypothesis that exposure to light at night increases risk of breast cancer via suppression of nocturnal melatonin production was proposed over 2 decades ago. In 2007, shift work that involves circadian disruption has been recognized by the World Health Organization as a probable human carcinogen. Our discovery of melatonin-dependent regulation of LINE-1 retrotransposon expression and mobilization is the latest addition to the list of cellular genes and processes that are affected by light exposure at night. This finding establishes an unexpected health relevant connection between this endogenous DNA damaging agent and environmental light exposure. It also offers an appealing hypothesis pertaining to the origin of genomic instability in the genomes of individuals with light at night- or age-associated disruption of melatonin signaling.

Keywords: aging, shift-work, cancer, DNA damage, genomic instability, light exposure at night, LINE-1, melatonin, melatonin receptor, retroelements

We recently discovered that melatonin signaling suppresses endogenous L1 expression in a tissue-isolated xenograft model of human prostate cancer, and melatonin receptor 1 (MT1) overexpression considerably suppresses L1 and L1-driven Alu mobilization in cancer cells.1 Our recent findings illustrate several novel features of L1 biology directly relevant to human health. Specifically, we highlight a new dimension to the complex regulation of both L1 expression and damage through the unforeseen connection between L1, the host's circadian system, and environmental light exposure at night in vivo.

Long Interspersed Element-1 (LINE-1 or L1) is a currently active mobile genetic element that belongs to the group of non-long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons. L1 is expressed in both the germ line and somatic cells, where it contributes to genomic instability via a “copy-and-paste” mechanism of amplification.2 This mode of propagation has resulted in approximately 500,000 L1 loci in the human genome, comprising 17% of the host genomic content.3 The majority of these loci are fossils of previously active L1 elements. Based on our knowledge, the bulk of retrotransposition in the human genome originates from a handful of active L1 loci fixed in the population,4,5 hundreds of highly active polymorphic L1s with variable allele frequencies,6,7 and an undetermined number of private L1 elements.7 Consequently, any given genome harbors a unique assortment of active L1s, which impose distinctly different loads of genomic instability.

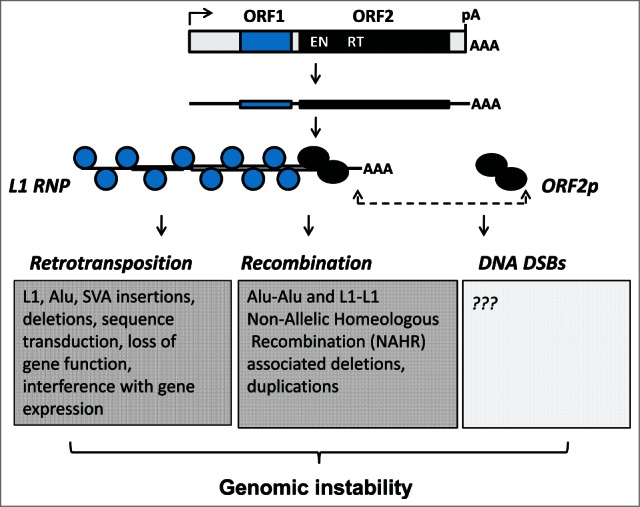

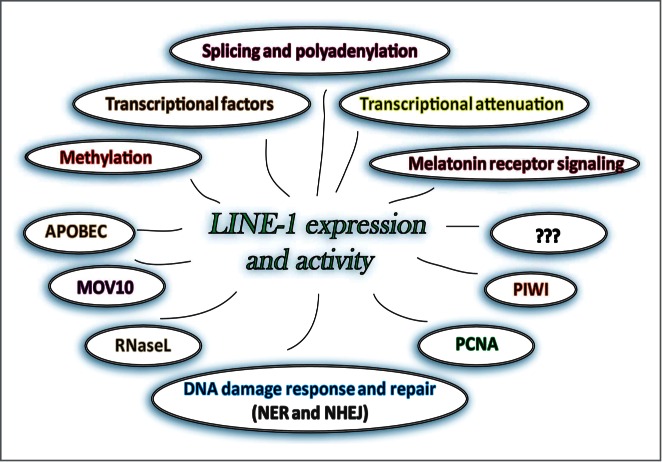

Expression of L1 mRNA and 2 proteins (ORF1p and ORF2p) encoded by this RNA followed by their assembly into a functional ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particle are prerequisites of successful L1 retrotransposition8,9 (Fig. 1). Among many requirements, L1 integration relies on the activity of the ORF2p-encoded endonuclease, which recognizes and cleaves at A/T-rich sequences.10 There are millions of suitable EN sites randomly distributed throughout the human genome.11 Their presence, combined with the length variability of newly inserted L1 sequences, which contain functional polyadenylation and splice sites,12-14 shape the unique content-specific consequences of each integration event.15,16 In addition to cumulative L1 activity in any given genome, the differences in the function of available cellular pathways suppressing L1 activity may contribute to the reported variation in L1 retrotransposition among individual genomes.17-19 The increasing list of host proteins and pathways reported to suppress L1 mobilization in cultured cells is an implicit indication of the importance of minimizing L1-associated damage (Fig. 2).13,14,16,20-34

Figure 1.

Genomic instability associated with L1 activity. A functional full-length L1 element contains a polymerase II promoter in its 5′ untrunslated region and 2 open reading frames ORF1 (blue) and ORF2 (black), which encode proteins necessary for L1 retrotransposition. Both proteins associate with the L1 mRNA to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles that are considered to be retrotranspositional intermediates. The ORF1p functions as a trimer, which has a nucleic acid chaperon activity. The ORF2p contains an endonuclease (EN) and reverse transcriptase activities (RT) critical for nicking genomic DNA and generating L1 cDNA. Either as a part of the L1 RNP or as a “loose” protein, the ORF2p is responsible for the generation of DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). L1 has a potential to contribute to genomic instability through retrotransposition, non-allelic homeologous recombination between integrated L1 or SINE Alu sequences, and DSBs.

Figure 2.

Many diverse known and yet unidentified cellular proteins and pathways suppress LINE-1 Alification by preventing L1 expression or integration. Some of the proteins and processes reported to affect L1 expression or integration are shown.

It remains largely unknown how these various cellular functions affecting L1 activity are balanced in vivo.28,35 The lack of understanding how the coordination of cellular networks relevant to the L1 life cycle are established in vivo is further complicated by the fact that expression or function of about 3,000 mammalian genes exhibit circadian rhythmicity in vivo.36 Temporal organization of cellular functions in all tissues is an important component of living systems. This task is carried out by the host circadian system, which is governed by an autonomously oscillating central circadian clock located in the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the brain. It is known as a “master regulator,” as the disruption of its function (known as circadian disruption) results in a systemic break down of normal functions in many peripheral tissues. The communication between the central circadian clock and the clocks functioning in peripheral tissues is established in part by the neurohormone melatonin. Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland during the dark phase of the circadian cycle, and its synthesis is suppressed during the day by exposure to light. Suppression of melatonin production at night by exposure to artificial light is a contributing factor to the negative health consequences of circadian disruption associated with shift work.37-40 Melatonin signaling in targeted tissues is established through its G protein-coupled receptors, MT1 and MT2, which are expressed in a tissue-specific, circadian manner.41 Circadian-regulated melatonin synthesis coupled with circadian oscillation of melatonin receptor expression is an important, evolutionarily conserved mechanism that has developed to synchronize biological functions with the periodicity of environmental light/dark cycles.42,43 Industrialization created an environment of continuous exposure to artificial light at night (LAN or LEN, light exposure at night). The negative health consequences of this, including an increased risk of cancer, have only recently begun to be officially recognized by the medical community.39,44,45 It seems plausible that the LAN-associated increase in cancer risk originates from the increase in genomic instability, as the loss of genome integrity is an underlying cause of cancer.

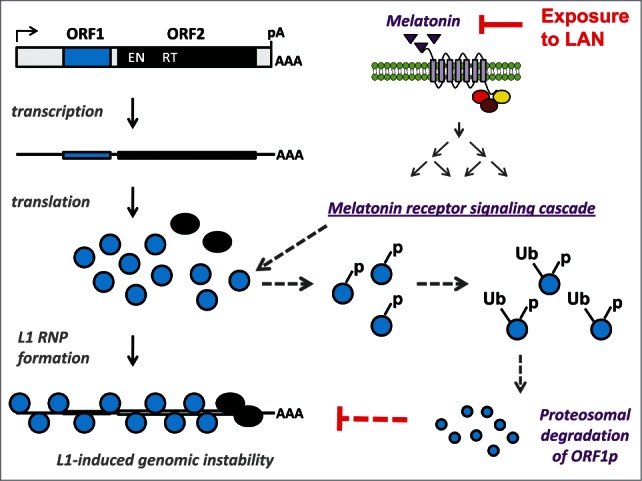

We recently reported an unexpected connection between melatonin signaling through its receptor(s) and endogenous L1 expression in a tissue-isolated xenograft model of human prostate cancer.1 Analysis of endogenous human L1 expression in PC3-derived xenografts perfused with human blood collected at noon or midnight as well as at night after exposure to bright light demonstrated that night-time blood suppresses L1 expression. The addition of exogenous melatonin to melatonin-poor blood during perfusion suppressed L1 expression; while the addition of non-selective antagonist of melatonin receptors during perfusion with melatonin-rich blood restored detection of L1 mRNA in tumor samples. These findings established the involvement of melatonin signaling in the regulation of L1 mRNA expression. Consistent with this finding, overexpression of MT1 receptor in cultured cancer cells dramatically decreased retrotransposition of L1 and Alu elements. This effect was significantly abrogated through treatments with melatonin receptor antagonists. MT1 overexpression significantly downregulated L1 ORF1 protein levels regardless of whether the protein was expressed from the full-length L1 element or an ORF1p expression plasmid with CMV promoter. Site-directed mutagenesis of putative phosphorylation and ubiquitination sites identified within the ORF1 protein sequence eliminated MT1-dependent suppression of ORF1 protein levels, suggesting that MT1 signaling may result in a phosphorylation-dependent degradation of ORF1 protein (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of melatonin-induced suppression of L1 mobilization. mRNA expression of functional L1 loci results in translation of L1 encoded ORF1 and ORF2 proteins (blue and black circles, respectively). The L1 mRNA and proteins associate to form L1 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles that undergo retrotrotransposition resulting in L1-associated genomic instability. Nocturnal melatonin production (purple triangles) activates G-coupled melatonin receptors leading to activation of melatonin receptor signaling network, which includes multiple kinases. Our data suggest that activation of this melatonin receptor signaling cascade results in ORF1p phosphorylation (−p) at one or more putative phosphorylation sites. Our results support that the phosphorylated ORF1p is targeted for ubiquitination (−Ub) and proteosomal degradation accounting for the reduced ORF1p levels and retrotransposition detected in the presence of melatonin receptor 1. This mechanism would be consistent with the mechanism of melatonin receptor-dependent suppression of other cellular proteins, which involves phosphorylation-induced ubiquitination targeting these proteins for proteosomal degradation. Solid arrows identify established events, dashed arrows represent events proposed based on our findings. Exposure to artificial light at night (LAN), which occurs during shift work, suppresses nocturnal melatonin synthesis blocking its downregulation of L1-induced genomic instability. Therefore, our data suggest that exposure to LAN may increase L1-induced genomic instability, which could contribute to the increased risk of cancer associated with shift work.

While it remains to be determined whether LAN increases mobilization of endogenous L1 in human samples, our findings establish an important hypothesis that LAN-associated loss of L1 regulation may be an underlying cause of higher incidence rates of cancer in a growing subpopulation of individuals regularly experiencing LAN, most notably shift workers. Based on this hypothesis, the considerable differences in L1 retrotransposition observed among human tumors of the same type19,46 may in part be due to the variation in patients' individual history of LAN. A variation in the efficacy of circadian systems dictated by genetic makeup of core circadian clock genes, melatonin receptors, and/or nighttime melatonin synthesis among patients may also influence L1-associated genomic instability. Furthermore, it is plausible that in addition to its direct effect on L1 ORF1 protein, LAN and associated circadian disruption may increase L1 activity indirectly by disrupting the function of host proteins or pathways suppressing L1 retrotransposition. For example, LAN can disrupt DNA damage response and repair, metabolism, and other signaling networks.47-52 L1 proteins have been reported to associate with numerous host proteins,20,34 and multiple cellular factors are known to suppress L1 mobilization in cultured cells. These findings suggest that the balanced existence of these complex suppressive interactions could be upset by LAN (Fig. 1).

If the same regulation takes place in normal cells, then L1-induced mutagenesis may also contribute to the early stages of tumorigenesis. Somatic cells also support L1 expression and retrotransposition (albeit with reduced efficiency and frequency compared to cancer cells).53-57 The levels of melatonin receptor expression vary significantly between normal and cancer cells, with most cancers expressing higher (and only a few lower) levels of the MT1 receptor than their corresponding normal tissues.58-62 This suggests that cancer cells may be hypersensitive to melatonin suppression relative to their normal counterparts. The tissue-specific differences in the levels of melatonin receptor expression61 suggest a possibility that various tissues may be experiencing different levels of upregulation in L1-induced damage upon LAN. We previously reported differential expression of endogenous L1 mRNA in various human tissues.53 Based on our recent discovery, it is possible that the observed tissue-specific differences were due, in part, to this phenomenon or time-of-day variations in tissue collection between different samples. Understanding the health-relevant impact of LAN on L1 activity in normal cells is an important next step in our research, as it is directly relevant to aging and age-associated diseases. It is established that melatonin production and its receptor expression decline with age,63 suggesting the possibility of an increase in L1-induced damage with age. As previously mentioned, genomic instability is an underlying cause of most cancers. As the only autonomous element still active in the human genome, L1 is the driving force of TE (transposable element)-associated genomic instability in humans that can contribute to cancer- relevant mutations.19,64,65 As normal cells are equipped with all functional pathways controlling the L1 replication cycle, LAN could be a signal that may increase L1 activity in normal cells by eliminating some redundancies set in place to suppress L1-induced damage.66 If so, L1-associated damage could be a molecular link between LAN and increased cancer risk observed in shift workers and potentially other groups in the general population frequently experiencing exposure to light at night.

Overall, upregulation of L1 expression is one of many cellular events and processes that are affected by exposure to artificial LAN and have the potential to negatively impact human health. Continuing scientific progress and growing public awareness about the negative health consequences of exposure to LAN should eventually culminate in routine consideration of personal history of exposure to light or light-emitting electronic devices at night as a part of diagnosis or individual treatment plan.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Deharo D, Kines KJ, Sokolowski M, Dauchy RT, Streva VA, Hill SM, Hanifin JP, Brainard GC, Blask DE, Belancio VP. Regulation of L1 expression and retrotransposition by melatonin and its receptor: implications for cancer risk associated with light exposure at night. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42(12):7694-707; PMID:24914052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bibillo A, Eickbush TH. The reverse transcriptase of the R2 non-LTR retrotransposon: continuous synthesis of cDNA on non-continuous RNA templates. J Mol Biol 2002; 316 459-73; PMID:11866511; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W., et al.. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 2001; 409, 860-921; PMID:11237011; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35057062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouha B, Schustak J, Badge RM, Lutz-Prigge S, Farley AH, Moran JV, Kazazian HH. Jr. Hot L1s account for the bulk of retrotransposition in the human population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100 5280-5; PMID:12682288; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0831042100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sassaman DM, Dombroski BA, Moran JV, Kimberland ML, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Gabriel A, Swergold GD, Kazazian HH Jr. Many human L1 elements are capable of retrotransposition ; [see comments]. Nat Genet 1997; 16 37-43; PMID:9140393; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng0597-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck CR, Collier P, Macfarlane C, Malig M, Kidd JM, Eichler EE, Badge RM. Moran JV. LINE-1 retrotransposition activity in human genomes. Cell 2010; 141 1159-70; PMID:20602998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streva VA, Jordan VE, Linker S, Hedges GJ, Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Sequencing, Identification and mapping of primed L1 elements (SIMPLE) reveals significant variation in full length L1 elements between individuals. BMC Genomics 2015; 21(16):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulpa DA, Moran JV. Ribonucleoprotein particle formation is necessary but not sufficient for LINE-1 retrotransposition. Hum Mol Genet 2005; 14 3237-48; PMID:16183655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddi354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moran JV, Holmes SE, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Boeke JD, Kazazian HH Jr. High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell 1996; 87 917-27; PMID:8945518; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81998-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH Jr., Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell 1996; 87, 905-16; PMID:8945517; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81997-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang K, Fan W, Deininger P, Edwards A, Xu Z. Zhu D. Breaking the computational barrier: a divide-conquer and aggregate based approach for Alu insertion site characterisation. Int J Comput Biol Drug Des 2009; 2 302-22; PMID:20090173; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1504/IJCBDD.2009.030763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin SL, Li WL, Furano AV. Boissinot S. The structures of mouse and human L1 elements reflect their insertion mechanism. Cytogenet Genome Res 2005; 110 223-8; PMID:16093676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000084956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belancio VP, Hedges DJ. Deininger P. LINE-1 RNA splicing and influences on mammalian gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34 1512-21; PMID:16554555; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkl027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perepelitsa-Belancio V, Deininger P. RNA truncation by premature polyadenylation attenuates human mobile element activity. Nat.Genet 2003; 35 363-6; PMID:14625551; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kines KJ, Belancio VP. Expressing genes do not forget their LINEs: transposable elements and gene expression. Front Biosci 2012; 17 1329-44; PMID:22201807; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/3990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheelan SJ, Aizawa Y, Han JS, Boeke JD. Gene-breaking: a new paradigm for human retrotransposon-mediated gene evolution. Genome Res 2005; 15, 1073-8; PMID:16024818; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.3688905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baillie JK, Barnett MW, Upton KR, Gerhardt DJ, Richmond TA, De Sapio F, Brennan PM, Rizzu P, Smith S, Fell M. et al.. Somatic retrotransposition alters the genetic landscape of the human brain. Nature 2011; 479 534-7; PMID:22037309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature10531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solyom S, Ewing AD, Rahrmann EP, Doucet TT, Nelson HH, Burns MB, Harris RS, Sigmon DF, Casella A, Erlanger B. et al.. Extensive somatic L1 retrotransposition in colorectal tumors. Genome Res 2012; 22(12):2328-38; PMID:22968929; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.145235.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee E, Iskow R, Yang L, Gokcumen O, Haseley P, Luquette LJ III, Lohr JG, Harris CC, Ding L, Wilson RK. et al.. Landscape of somatic retrotransposition in human cancers. Science 2012; 337(6097):967-71; PMID:22745252; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1222077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodier JL, Cheung LE, Kazazian HH Jr. Mapping the LINE1 ORF1 protein interactome reveals associated inhibitors of human retrotransposition. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41 7401-19; PMID:23749060; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JS, Szak ST, Boeke JD. Transcriptional disruption by the L1 retrotransposon and implications for mammalian transcriptomes. Nature 2004; 429 268-74; PMID:15152245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hata K, Sakaki Y. Identification of critical CpG sites for repression of L1 transcription by DNA methylation. Gene 1997; 189 227-34; PMID:9168132; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00856-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker KG, Swergold GD, Ozato K. Thayer RE. Binding of the ubiquitous nuclear transcription factor YY1 to a cis regulatory sequence in the human LINE-1 transposable element. Hum Mol Genet 1993; 2 1697-702; PMID:8268924; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurose K, Hata K, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. Rna-polymerase-lii dependence of the human L1 promoter and possible participation of the Rna-polymerase-Ii factor Yy1 in the Rna-polymerase-Iii transcription system. Nucleic Acids Res 23 1995; 3704-9; PMID:7479000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/23.18.3704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasior SL, Roy-Engel AM, Deininger PL. ERCC1/XPF limits L1 retrotransposition. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008; 7 983-9; PMID:18396111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Meter M, Kashyap M, Rezazadeh S, Geneva AJ, Morello TD, Seluanov A. Gorbunova V. SIRT6 represses LINE1 retrotransposons by ribosylating KAP1 but this repression fails with stress and age. Nat Commun 2014; 5 5011; PMID:25247314; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms6011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coufal NG, Garcia-Perez JL, Peng GE., Marchetto MC, Muotri AR, Mu Y, Carson CT, Macia A, Moran JV, Gage FH. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) modulates long interspersed element-1 (L1) retrotransposition in human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108 20382-7; PMID:22159035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1100273108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aravin AA, Sachidanandam R, Girard A, Fejes-Toth K. Hannon GJ. Developmentally regulated piRNA clusters implicate MILI in transposon control. Science 2007; 316 744-7; PMID:17446352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1142612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogerd HP, Wiegand HL, Hulme AE, Garcia-Perez JL, O'Shea KS, Moran JV, Cullen BR. Cellular inhibitors of long interspersed element 1 and Alu retrotransposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103 8780-5; PMID:16728505; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0603313103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Lilley CE, Yu Q, Lee DV, Chou J, Narvaiza I, Landau NR, Weitzman MD. APOBEC3A is a potent inhibitor of adeno-associated virus and retrotransposons. Curr Biol 2006; 16 480-5; PMID:16527742; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muckenfuss H, Hamdorf M, Held U, Perkovic M, Lower J, Cichutek K, Flory E, Schumann GG. Munk C. APOBEC3 Proteins Inhibit Human LINE-1 retrotransposition. J Biol Chem 2006; 281 22161-72; PMID:16735504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M601716200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenglein MD. Harris RS. APOBEC3B and APOBEC3F inhibit L1 retrotransposition by a DNA deamination-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem 2006; 281 16837-41; PMID:16648136; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M602367200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang A, Dong B, Doucet AJ, Moldovan JB, Moran JV. Silverman RH. RNase L restricts the mobility of engineered retrotransposons in cultured human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2014; 42 3803-20; PMID:24371271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor MS, Lacava J, Mita P, Molloy KR, Huang CR, Li D, Adney EM, Jiang H, Burns KH, Chait BT. et al.. Affinity proteomics reveals human host factors implicated in discrete stages of LINE-1 retrotransposition. Cell 2013; 155 1034-48; PMID:24267889; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourc'his D, Bestor TH. Meiotic catastrophe and retrotransposon reactivation in male germ cells lacking Dnmt3L. Nature 2004; 431 96-9; PMID:15318244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes ME, DiTacchio L, Hayes KR, Vollmers C, Pulivarthy S, Baggs JE, Panda S, Hogenesch JB. Harmonics of circadian gene transcription in mammals. PLoS Genet 2009; 5 e1000442; PMID:19343201; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blask DE, Dauchy RT, Brainard GC, Hanifin JP. Circadian stage-dependent inhibition of human breast cancer metabolism and growth by the nocturnal melatonin signal: consequences of its disruption by light at night in rats and women. Integr Cancer Ther 2009; 8 347-53; PMID:20042410; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1534735409352320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schernhammer ES, Hankinson SE. Urinary melatonin levels and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97 1084-7; PMID:16030307; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/dji190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens RG, Brainard GC, Blask DE, Lockley SW, Motta ME. Breast cancer and circadian disruption from electric lighting in the modern world. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64 207-18; PMID:24604162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3322/caac.21218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens RG. Working against our endogenous circadian clock: breast cancer and electric lighting in the modern world. Mutat Res 2009; 680 106-8; PMID:20336819; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubocovich ML, Markowska M. Functional MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors in mammals. Endocrine 2005; 27 101-10; PMID:16217123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hardeland R, Madrid JA, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin, the circadian multioscillator system and health: the need for detailed analyses of peripheral melatonin signaling. J Pineal Res 2012; 52 139-66; PMID:22034907; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan DX, Hardeland R, Manchester LC, Paredes SD, Korkmaz A, Sainz RM, Mayo JC, Fuentes-Broto L, Reiter RJ. The changing biological roles of melatonin during evolution: from an antioxidant to signals of darkness, sexual selection and fitness. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2010; 85, 607-23; PMID:20039865; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevens RG, Hansen J, Costa G, Haus E, Kauppinen T, Aronson KJ, Castano-Vinyals G, Davis S, Frings-Dresen MH, Fritschi L. et al.. Considerations of circadian impact for defining 'shift work' in cancer studies: IARC working group report. Occup Environ Med 2011; 68 154-62; PMID:20962033; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/oem.2009.053512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens RG, Brainard GC, Blask DE, Lockley SW, Motta ME. Adverse health effects of nighttime lighting: comments on american medical association policy statement. Am J Prev Med 2013; 45, 343-6; PMID:23953362; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tubio JM, Li Y, Ju YS, Martincorena I, Cooke SL, Tojo M, Gundem G, Pipinikas CP, Zamora J, Raine K. et al.. Mobile DNA in cancer. extensive transduction of nonrepetitive DNA mediated by L1 retrotransposition in cancer genomes. Science 2014; 345 1251343; PMID:25082706; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1251343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang TH, Reardon JT, Kemp M. Sancar A. Circadian oscillation of nucleotide excision repair in mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106 2864-7; PMID:19164551; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0812638106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wood PA, Yang X, Hrushesky WJ. Clock genes and cancer. Integr Cancer Ther 2009; 8 303-8; PMID:20042409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/1534735409355292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J, Dauchy RT, Tirrell PC, Wu SS, Lynch DT, Jitawatanarat P, Burrington CM, Dauchy EM, Blask DE, Greene MW. Light at night activates IGF-1R/PDK1 signaling and accelerates tumor growth in human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res 2011; 71, 2622-31; PMID:21310824; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gotoh T, Vila-Caballer M, Santos CS, Liu J, Yang J, Finkielstein CV. The circadian factor period 2 modulates p53 stability and transcriptional activity in unstressed cells. Mol Biol Cell 2014; 25(19):3081-93; PMID:25103245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E14-05-0993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamada T, Niki T, Ishida N. Role of p53 in the entrainment of mammalian circadian behavior rhythms. Genes Cells 2014; 19 441-8; PMID:24698115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/gtc.12144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miki T, Matsumoto T, Zhao Z, Lee CC. p53 regulates Period2 expression and the circadian clock. Nat Commun 2013; 4, 2444; PMID:24051492; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belancio VP, Roy-Engel AM, Pochampally RR, Deininger P. Somatic expression of LINE-1 elements in human tissues. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38 3909-22; PMID:20215437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ergun S, Buschmann C, Heukeshoven J, Dammann K, Schnieders F, Lauke H, Chalajour F, Kilic N, Stratling WH, Schumann GG. Cell type-specific expression of LINE-1 open reading frames 1 and 2 in fetal and adult human tissues. J Biol Chem 2004; 279 27753-63; PMID:15056671; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M312985200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Branciforte D, Martin SL. Developmental and cell type specificity of LINE-1 expression in mouse testis: implications for transposition. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14 2584-92; PMID:8139560; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.14.4.2584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kubo S, Seleme MC, Soifer HS, Perez JL, Moran JV, Kazazian HH Jr, Kasahara N. L1 retrotransposition in nondividing and primary human somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103 8036-41; PMID:16698926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0601954103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evrony GD, Cai X, Lee E, Hills LB, Elhosary PC, Lehmann HS, Parker JJ, Atabay KD, Gilmore EC, Poduri A. et al.. Single-neuron sequencing analysis of l1 retrotransposition and somatic mutation in the human brain. Cell 2012; 151 483-96; PMID:23101622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aust S, Jager W, Kirschner H, Klimpfinger M, Thalhammer T. Pancreatic stellate/myofibroblast cells express G-protein-coupled melatonin receptor 1. Wien Med Wochenschr 2008; 158, 575-8; PMID:18998076; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10354-008-0599-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jablonska K, Pula B, Zemla A, Owczarek T, Wojnar A, Rys J, Ambicka A, Podhorska-Okolow M, Ugorski M, Dziegiel P. Expression of melatonin receptor MT1 in cells of human invasive ductal breast carcinoma. J Pineal Res 2013; 54 334-45; PMID:23330677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/jpi.12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nemeth C, Humpeler S, Kallay E, Mesteri I, Svoboda M, Rogelsperger O, Klammer N, Thalhammer T, Ekmekcioglu C. Decreased expression of the melatonin receptor 1 in human colorectal adenocarcinomas. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2011; 25 531-42; PMID:22217986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poirel VJ, Cailotto C, Streicher D, Pevet P, Masson-Pevet M, Gauer F. MT1 melatonin receptor mRNA tissular localization by PCR amplification. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2003; 24 33-8; PMID:12743529 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Toma CD, Svoboda M, Arrich F, Ekmekcioglu C, Assadian O, Thalhammer T. Expression of the melatonin receptor (MT) 1 in benign and malignant human bone tumors. J Pineal Res 2007; 43, 206-13; PMID:17645699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00464.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill SM, Cheng C, Yuan L, Mao L, Jockers R, Dauchy B, Frasch T, Blask DE. Declining melatonin levels and MT1 receptor expression in aging rats is associated with enhanced mammary tumor growth and decreased sensitivity to melatonin. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 127(1):91-8; PMID:20549340; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-010-0958-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Halling KC, Lazzaro CR, Honchel R, Bufill JA, Powell SM, Arndt CA, Lindor NM. Hereditary desmoid disease in a family with a germline Alu I repeat mutation of the APC gene. Hum Hered 1999; 49 97-102; PMID:10077730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000022852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin C, Yang L, Tanasa B, Hutt K, Ju BG, Ohgi K, Zhang J, Rose DW, Fu XD, Glass CK. et al.. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell 2009; 139 1069-83; PMID:19962179; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Belancio VP, Blask DE, Deininger P, Hill SM, Jazwinski SM. The aging clock and circadian control of metabolism and genome stability. Front Genet 2014; 5 455; PMID:25642238; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fgene.2014.00455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]