Abstract

The chromosome-like stability of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasmid 2 micron circle likely stems from its ability to tether to chromosomes and segregate by a hitchhiking mechanism. The plasmid partitioning system, responsible for chromosome-coupled segregation, is comprised of 2 plasmid coded proteins Rep1 and Rep2 and a partitioning locus STB. The evidence for the hitchhiking model for mitotic plasmid segregation, although compelling, is almost entirely circumstantial. Direct tests for plasmid-chromosome association are hampered by the limited resolving power of current cell biological tools for analyzing yeast chromosomes. Recent investigations, exploiting the improved resolution of yeast meiotic chromosomes, have revealed the plasmid's propensity to be present at or near chromosome tips. This localization is consistent with the rapid plasmid movements during meiosis I prophase, closely resembling telomere dynamics driven by a meiosis-specific nuclear envelope motor. Current evidence is consistent with the plasmid utilizing the motor as a platform for gaining access to telomeres. Episomes of viruses of the papilloma family and the gammaherpes subfamily persist in latently infected cells by tethering to chromosomes. Selfish genetic elements from fungi to mammals appear to have, by convergent evolution, arrived at the common strategy of chromosome association as a means for stable propagation.

Keywords: chromosome tethering, epstein-barr virus, germ-line plasmid transmission, KSHV, papilloma viruses, 2 micron plasmid

Introduction

The 2 micron plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is small in size (∼6.3 kbp) and simple in organization (coding capacity for 4 proteins), yet almost as stable as the chromosomes of its host.1,2 The 40-60 plasmid copies appear to be organized in the nuclei as a finite number of foci, thus reducing its effective copy number.3-5 The plasmid is an innocuous entity at its normal copy number, providing no apparent advantage, or costing little fitness penalty, to the host. The plasmid genome can be divided into 2 functional units, a replication-partitioning system and a copy number control system (Fig. 1). The plasmid replication origin promotes the duplication of each molecule, once per cell cycle, by the chromosome replication machinery. The partitioning system, comprised of the Rep1-Rep2 proteins and the cis-acting STB locus, ensures the equal (or nearly equal) segregation of the replicated plasmids to mother and daughter nuclei. The plasmid amplification system, constituted by the Flp recombinase and its target sites (FRTs), protects against a drop in copy number due to rare missegregation events. The amplification reaction is triggered by a temporally controlled recombination event during bi-directional plasmid replication, which inverts one replication fork with respect to the other.6,7 The double uni-directional forks can spin out multiple, tandem plasmid copies until a second recombination event restores bi-directional fork movement and replication termination. The amplified DNA may be resolved into monomeric plasmid units by homologous recombination or by Flp-mediated recombination. The Rep proteins are presumed to form a transcriptional repressor that negatively regulates the amplification system. The Raf1 protein appears to promote amplification by antagonizing the Rep1-Rep2 repressor. The combined effects of the positive and negative transcriptional controls is the prompt commissioning of plasmid amplification when needed without the danger of runaway amplification.8-10 Furthermore, control of Flp activity by its post-translational modification by the host sumoylation system is also important in preventing aberrant plasmid amplification.11,12 The 2 micron plasmid represents a highly optimized selfish DNA element, whose genome design is devoted solely to the self-serving ends of replication, partitioning and steady state copy number maintenance.

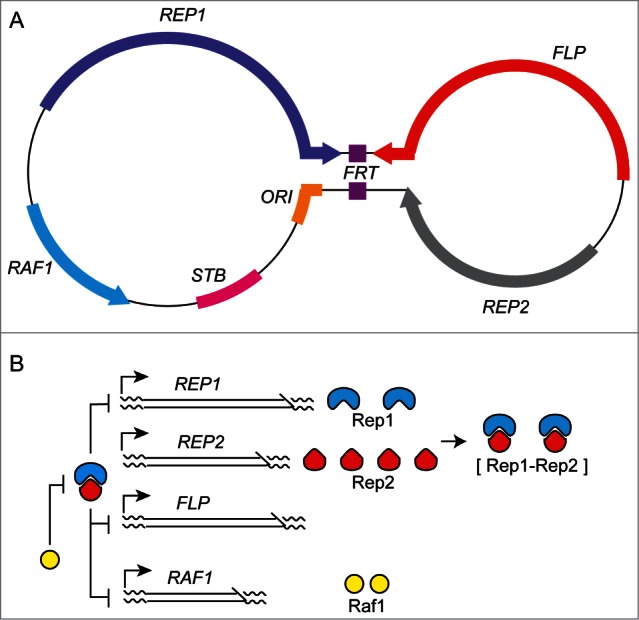

Figure 1.

The 2 micron plasmid genome: organization and regulation. (A) The dumb-bell representation of the 2 micron plasmid illustrates its organization as 2 unique regions separated by an inverted repeat region, shown as the handle of the dumb-bell. The replication origin (ORI) promotes the duplication of each plasmid molecule once per cell cycle by the cellular replication apparatus. The protein coding regions are demarcated by the arrows, with the direction of transcription indicated by the arrowheads. The STB locus and the Rep1 and Rep2 proteins constitute the plasmid partitioning system.60,61 The Flp protein (a site-specific recombinase), together with its target sites (FRTs) located within the inverted repeat, is responsible for plasmid copy number maintenance by a DNA amplification mechanism.6,7 Raf1 promotes plasmid amplification by relieving the repression on Flp gene expression. (B) Genetic evidence suggests that the plasmid partitioning proteins (Rep1, Rep2) form a bipartite repressor that negatively regulates FLP, RAF1 and REP1.8-10 REP2 is apparently not controlled by the Rep1-Rep2 repressor. Raf1 is an antagonist of the repressor. At steady-state plasmid copy number, the repressor level exceeds a critical threshold sufficient to turn off the amplification system. Below steady state copy number, the drop in repressor level turns on FLP and RAF1 to trigger the amplification response. REP1 is also under repressor control, so that the level of the Rep1 protein provides an indirect readout of the plasmid copy number. Furthermore, the Rep1 amount determines the effective repressor concentration, as REP2 expression appears to be constitutive.

The 2 micron plasmid has supplied components for the construction of widely used hybrid vectors that can be readily shuttled between yeast and bacteria. Two micron-based plasmids can be maintained at high copy numbers in yeast with much better stability than comparable replicating plasmids lacking an active partitioning system (ARS-plasmids). The Flp recombination system has been seminal to our current understanding of the structural, dynamic and mechanistic features of DNA cleavage/exchange mediated by tyrosine family site-specific recombinases.13-15 The recombination reaction has also provided an effective tool for addressing fundamental problems in DNA topology and developmental biology, and for directed engineering of genomes with potential broad implications in biotechnology and medicine.16-18 The plasmid offers an excellent model system to explore the interplay of self-imposed as well as host-instituted mechanisms that promote their long-term coexistence with minimal mutual conflicts. A more incisive understanding of the plasmid partitioning mechanisms may help design strategies for not only the maintenance of beneficial extra-chromosomal elements in eukaryotic cells but also for the elimination of harmful ones. In this report, we consider the most recent advances in our understanding of plasmid partitioning, and discuss the broader issues arising from them.

Chromosome-coupled segregation of the 2 micron plasmid during mitosis: multi-copy reporter plasmids

Early analyses of plasmid segregation were performed using multi-copy STB-reporter plasmids, fluorescence-tagged by operator-fluorescent repressor interaction.3,19 Even though the variable number of plasmid foci (3–5 per nucleus), the occasional coalescence of foci and the uncertainty regarding the number of molecules in a focus made quantitations somewhat imprecise, the strong coupling between plasmid and chromosome segregation promoted by the Rep-STB system was obvious. In similar assays, an ARS-plasmid or an STB-plasmid deprived of the Rep proteins showed significantly lower equal segregation frequencies, and no coupling to chromosomes. Furthermore, consistent with other observations,20,21 plasmid missegregation was strongly biased toward the mother. The mother bias can be accounted for largely by the geometry of the yeast nucleus with its neck constriction and the relatively short duration of the cell cycle,21 and perhaps plasmid association with sub-nuclear structures.22 Together they manifest a diffusion barrier that prevents equilibration of plasmid molecules between the mother and daughter compartments. Overcoming mother bias, assisted by the Rep-STB system, is thus an integral feature of the 2 micron plasmid partitioning system.

Segregation of single-copy STB-reporter plasmids

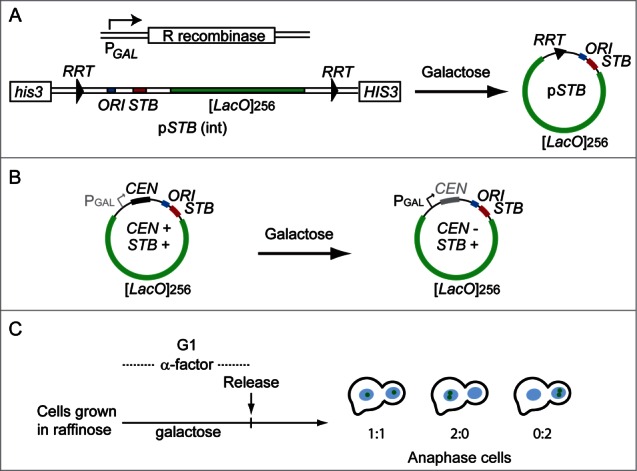

Single-copy fluorescence-tagged reporter plasmids permit precise estimates of equal segregation (1:1) and missegregation (2:0, mother-biased and 0:2, daughter-biased) during a single cell cycle (Fig. 2). Two types of single-copy reporters, with distinct designs, have yielded mutually concordant results. In one, the plasmid copy number was maintained as one or close to one by a centromere (CEN) harbored by it, and the CEN was conditionally inactivated by driving transcription through it.23 In the other, the plasmid copy number was set precisely as one by excising it from a chromosomally integrated state via site-specific recombination.24 CEN inactivation or plasmid excision was performed in G1-arrested cells, and after releasing them from arrest, the segregation of the sister plasmid copies was assayed in late anaphase cells containing 2 well separated nuclei.

Figure 2.

Single copy reporter plasmids for analysis of 2 micron plasmid segregation. The two strategies underlying the design of single copy reporter plasmids23,24 are schematically illustrated (A and B). (A) In the example shown, the plasmid containing [LacO]256, and bordered by the target sites for the R site-specific recombinase, is integrated at the his3 locus on chromosomes XV. The host strain is engineered to express GFP-LacI and the R recombinase under control of the HIS3 promoter and the GAL promoter, respectively. (B) The [LacO]256-containing reporter plasmid harbors a CEN sequence placed adjacent to the GAL promoter, and is introduced into a strain expressing GFP-LacI. In the presence of galactose, the high-level transcription through CEN inactivates its function. (C) The recombination reaction to excise the reporter plasmid from the chromosome (A) or the inactivation of the plasmid-borne CEN (B) is performed in G1-arrested cells. After their release, the segregation of the replicated sister copies of the plasmid is assayed in late anaphase cells.

The outcomes from single-copy reporter assays not only upheld the notion of chromosome-coupled plasmid segregation but also revealed an important additional attribute of sister plasmids. Two STB-plasmid sisters formed from single-copy sisters, one pair tagged by green fluorescence and the other by red fluorescence, segregated most often in a one-to-one fashion, the mother and daughter each receiving one green and one red plasmid.23 Thus, the segregation of the STB-plasmid sisters is analogous to that of sister chromatids. This unsuspected connection between sister plasmids and sister chromatids was verified by programming a mitotic cell cycle in the presence of the monopolin complex, which normally directs the co-segregation of sister chromatids during the reductional division of meiosis I.25 An STB-plasmid and a fluorescence-tagged reporter chromosome were almost perfectly correlated in their 2:0 segregation under the influence of monopolin, and this missegregation was bias-free with respect to mother and daughter.24 The segregation of an ARS-plasmid, by contrast, was unaffected by monopolin, and remained strongly mother-biased.

Plasmid-chromosome tethering? Plasmid segregation by hitchhiking

The most parsimonious explanation for the behavior of multi-copy STB-reporter plasmids is that they tether to chromosomes and segregate by a hitchhiking mechanism. Consistent with this model, a multi-copy reporter plasmid was shown to be associated with chromosome spreads prepared from mitotic yeast cells in a Rep1-Rep2-STB-dependent manner.19,26 In companion assays, Rep1 and Rep2 could localize to the spreads in the absence of an STB-plasmid; however, each was dependent on the other for this localization. Chromosome spreads are not free of other nuclear components including nuclear membrane fragments. Furthermore, individual chromosomes are not resolved by these spreads. As a result, the spread data, while strongly suggestive of plasmid tethering to chromosomes, cannot be taken as proof for the hitchhiking model.

Assuming the hitchhiking model to be valid (with the aforementioned caveats), the segregation of the STB-plasmid sisters (resulting from single-copy reporters) suggests that they must be tethered to sister chromatids. Perhaps, the act of replication may help keep plasmid sisters paired, increasing their chances of associating with sister chromatids that are held together by the cohesin complex (see also the section below).27–29 Forced missegregation of individual chromosomes during a cell cycle one at a time, by conditional CEN inactivation, rules out the coupling of the 2 micron plasmid to a specific chromosome (our unpublished data). Furthermore, individual foci of a multi-copy reporter plasmid appear to function largely as independent units of segregation. During a deviant cell cycle under monopolin expression, the small fraction of cells containing all plasmid foci in one of the 2 anaphase nuclei was typified by a strong mother bias (N:0 >> 0:N).24 Based on the results with the single-copy reporter plasmid, monopolin-induced total missegregation should be bias-free (N:0 ≈0:N), if the foci were to segregate as one cluster. The overall frequency of plasmid missegregation was increased in the presence of monopolin, as expected.

If the single-copy paradigm can be applied to a plasmid focus with several molecules, their replication and the organization of the sister plasmid copies must follow a precisely orchestrated regimen. The molecular details of how this might be accomplished are unknown, although the host factors associated with STB19,30-34 suggest possible clues (see below under ‘Summary and Perspective’). The current notion is that a plasmid focus templates the formation of its sister focus in a replication-coupled process, and the 2 sister foci segregate from each other tethered to sister chromatids.

Host-factor assembly at STB: potential relevance of the cohesin complex to plasmid segregation

The STB-association of several host factors, which also associate with centromeres and partake in chromosome segregation, has raised the specter of the atypical point centromere of budding yeasts and STB having descended from a common ancestral locus that promoted both plasmid and chromosome segregation.35,36 Perhaps, the present day plasmid and chromosome partitioning mechanisms represent 2 nearly conflict-free solutions arrived at by the divergence of a pathway once shared between them. Among the chromosome segregation factors detected at STB, the most intriguing ones are the cohesin complex and the histone H3 variant Cse4.19,31,32,37 Their sub-stoichiometric amounts at STB might suggest that their presence at STB is simply a vestige of its shared evolutionary history with CEN, and may be functionally irrelevant to plasmid partitioning. Centromere-like regions (CLRs) in S. cerevisiae, where the presence of Cse4 has been observed, are thought to be once active centromeres or centromere-associated sequences that later became defunct.38 We are reluctant, at least for now, to dismiss STB as just a plasmid-borne CLR for reasons summarized below.

In addition to its most celebrated role in bridging sister chromatids to facilitate equal segregation, the cohesin complex also contributes to several other chromosome functions, including repair of DNA damage and silencing of gene expression.39,40 The likely underlying functional attribute in these diverse types of chromosome transactions is cohesin's ability to trap a pair of DNA duplexes in proximity by forming a topologically closed protein ring around them.28,29 Cohesin collaborates with condensin (both SMC complexes) at the pericentric intramolecular chromatin loops found in S. cerevisiae to establish a molecular spring that balances the spindle force during metaphase.41–44 It is possible that the 2 micron plasmid partitioning system takes advantage of the extensive metaphase chromosome-cohesin network to dispatch replicated plasmid copies equally toward opposite cell poles.

Two micron plasmid localization, dynamics and segregation during meiosis

The 2 micron plasmid is propagated efficiently during meiosis as well,45,46 although the mechanisms are not known. As paired homologous chromosomes at the pachytene stage of meiosis I are much better resolved (relative to mitotic chromosomes) in chromosome spreads, it seemed logical that plasmid-chromosome association might be more reliably tested in cells going through meiosis. We therefore followed the segregation of fluorescence-tagged multi-copy reporter plasmids during meiosis I and at completion of meiosis II.47

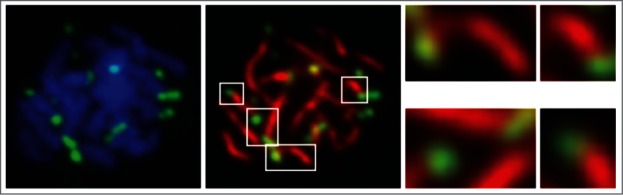

Equal or nearly equal plasmid segregation during meiosis I and efficient plasmid distribution to all 4 spores within a tetrad were found to be dependent on the Rep-STB system. As cells transitioned to the meiotic program, plasmid foci relocated from the interior of the nucleus toward the nuclear periphery at or adjacent to telomeres. Plasmid co-localization with telomeres increased significantly with the progression of meiosis I to the pachytene stage (Fig. 3). Consistent with this localization, plasmid foci exhibited rapid movements during prophase that matched telomere movements (Fig. 4) in maximum and average speeds as well as in bias (values of 0, <0 and >0 denoting random motion, the tendency to stay in place and the tendency to journey far, respectively).

Figure 3.

Localization of the 2 micron plasmid during meiosis. Chromosome spreads were prepared from cells at the pachytene stage of meiosis I. The paired homologues were visualized by DAPI staining (left panel) or by using an antibody to Zip1 (middle panel), which is localized along their central axes.62 The fluorescence tagged multi-copy STB- plasmid foci [(LacO)256-(GFP-LacI)] were detected using an antibody to GFP. Plasmid localization at or close to chromosome tips is highlighted in the right panel for a selected set of foci.

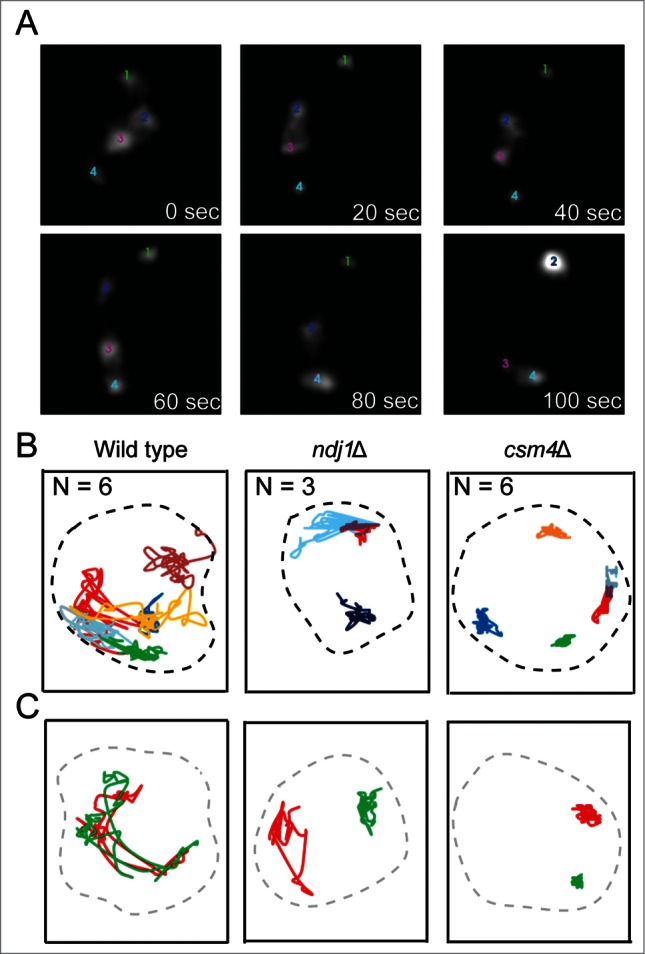

Figure 4.

Prophase dynamics of the 2 micron plasmid. (A) The real-time movements of 4 plasmid foci in a wild type cell at the prophase stage of meiosis I, recorded by through-focus imaging,50 over a period of 100 sec are shown. (B) The traces represent the movements of individual plasmid foci in wild type, ndj1Δ and csm4Δ strains. N refers to the number of plasmid foci tracked. (C) Analogous traces display the dynamics of chromosome VII telomeres (left arm). In this particular case, the 2 telomeres were not paired over the observation period. The correlations between chromosome and plasmid dynamics are described in greater detail in ref. 47.

The highly characteristic chromosome dynamics during prophase are controlled by a specialized meiosis-specific motor located at the nuclear envelope, and is likely powered by cytoplasmic actin.48-52 The bouquet proteins Mps3, Ndj1 and Csm4, which form the MNC complex, promote the transduction of mechanical energy into the nucleus and its conversion to the kinetic energy of chromosome movements. All three contribute toward the timely pairing of homologues, the normal pattern of meiotic recombination and the curtailment of ectopic or non-allelic recombination and aneuploidy.51,53–57 Lack of Csm4 or Ndj1, which slows down telomeres (csm4Δ much more severely than ndj1Δ), was found to slow down STB plasmid foci in a remarkably similar manner (Fig. 4). In the absence of Ndj1 or Csm4, the STB-reporter plasmid also showed a higher incidence of missegregation during meiosis I as well as a reduction in the fraction of asci with all 4 plasmid-containing spores.

The localization and dynamics results are most consistent with the potential association of the 2 micron plasmid with telomeres by way of the meiosis-specific nuclear envelope motor that drives telomere-led chromosome movements during prophase. However, direct plasmid interaction with telomeres via a telomere-binding protein (perhaps Rap1) as an alternative (or a secondary) route to plasmid-chromosome tethering cannot be ruled out. Since Csm4 and Ndj1 are meiosis-specific proteins, and Mps3 is expressed at very low levels during mitosis, distinct tethering mechanisms appear to operate during mitosis and meiosis. Additional modes of plasmid-chromosome association common to both mitosis and meiosis are possible as well. The segregation of the 2 micron plasmid as a telomere appendage during meiosis I would signify hitchhiking on chromosomes as the underlying logic that unifies faithful plasmid propagation during both vegetative and germ-line divisions of the host cells.

Summary and perspective

The equal segregation of the 2 micron plasmid during mitosis signifies its ability to overcome the mother bias with the help of its partitioning system. In principle, association with a nuclear entity that partitions efficiently between mother and daughter or spindle-assisted segregation can alleviate or eliminate mother bias. Plasmid segregation in association with the spindle pole body has been ruled out. Mutations, such as ipl1–2, that do not block spindle pole duplication or segregation, but cause chromosome missegregation, result in plasmid missegregation.3,19 As the kinetochore complex is not assembled at STB, direct attachment of the plasmid to the mitotic spindle is highly unlikely. Furthermore, the presence of 2 or more copies of STB on a reporter plasmid does not induce instabilities analogous to those seen in dicentric plasmids, suggesting that the 2 micron plasmid is not subject to opposing spindle forces. Thus, by a process elimination, in the context of several lines of experimental evidence from mitotic and meiotic cells, chromosomes are the most plausible nuclear entity that directly assists plasmid segregation. We therefore embrace the hitchhiking model until contrary evidence is uncovered.

It must be noted that 2 micron plasmid segregation by attachment to the nuclear matrix or to the nuclear membrane has not been experimentally ruled out. Nuclear matrix is poorly defined in budding yeast, which lacks a typical nuclear lamina that serves as a scaffold for a variety of associated membrane proteins. The stability of ARS-plasmids can be improved significantly by artificially tethering them to certain nuclear pore proteins such as Mlp1 or Nup2.58 By preventing the disassembly of the cohesin complex during anaphase, it is possible to confine the paired sister chromatids en masse to the mother or the other daughter compartment, with only modest effects on nuclear migration into the daughter. With chromosomes thus uncoupled from the nuclear membrane, it becomes feasible to address plasmid association with one or the other. If normal segregation of the 2 micron plasmid occurs by the chromosome-hitchhiking model, tethering the plasmid to the nuclear pore is likely to decrease, rather than improve, its equal segregation frequency. This expectation can also be easily tested. It is quite unlikely that the efficiency and precision of chromosomes in segregation will be matched by other nuclear entities.

Since metaphase chromosomes of mammalian cells can be visualized individually with clear resolution of sister chromatids, it may be possible to experimentally test aspects of the hitchhiking model in the context of a non-native host system. It is perhaps worthwhile to attempt to reconstitute, at least partially, the 2 micron plasmid partitioning system in mammalian cells.

The 2 micron partitioning clock is reset during each mitotic cell cycle, with the de novo assembly of the partitioning complex initiated at the G1-S window.34 One cue for this event appears to be DNA replication. It is not known whether plasmid replication and/or cellular DNA replication is required for the Rep-STB system to overcome mother bias. The effect of blocking plasmid replication during a cell cycle on mother bias can be examined by excising an ori-minus STB-circle integrated into a chromosome. Similarly, the effect of blocking both plasmid and chromosome replication can be monitored by conditionally depleting the Cdc6 protein.59 According to the hitchhiking model, overcoming mother bias can be accomplished by random plasmid association with chromosomes. However, in the case of a single-copy STB-plasmid, random tethering of the duplicated sister copies of the plasmid can actualize only 50% equal segregation events (as chromosomes segregate by independent assortment), the rest being bias-free missegregation (2:0, 25%; 0:2, 25%). The significantly higher equal segregation frequency of a single-copy STB- plasmid (∼70%), together with the non-random 1:1 segregation of 2 single-copy STB-plasmids,23 can be accounted for only by positing the tethering of sister plasmids to sister chromatids. As noted before, sister chromatids held together by the cohesin complex until the onset of anaphase27–29 offer excellent targets for the symmetric tethering of a pair of plasmid sisters, provided these are also kept proximal to each other. Recall that STB is a site for the Rep protein-dependent recruitment of cohesin,19,31 which entraps sister STBs by a topological mechanism.37 One difficulty with this model for the association of paired plasmid sisters with paired sister chromatids is that the amount of cohesin at STB is highly sub-stoichiometric. Cohesin may act at STB in a catalytic fashion to establish cohesion, which is thereafter maintained by the Rep proteins, perhaps with the assistance of other partitioning factors bound to STB.

The mean copy number of the 2 micron plasmid in a diploid cell is approximately double that in a haploid cell. There could be some mechanism by which the plasmid content is coordinated with chromosome content in mitotically dividing cells. Alternatively, a reductional mode of plasmid segregation (after one round of replication) during meiotic divisions might lower the plasmid content in haploid spores to half that in parent diploid cells. Equal plasmid segregation during meiosis I (as homologues) and meiosis II (as sisters) would demand a unique high-order organization of replicated molecules within a chromosome-associated plasmid focus. Furthermore, this organization has to be refractory to chromosomal exchanges by recombination. It would be nearly impossible to decipher the rules of plasmid segregation during meiosis using multi-copy reporter plasmids. This task could be greatly simplified if conditions can be established for following single-copy reporter plasmids through each of the 2 meiotic divisions.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

Our studies on 2 micron plasmid segregation was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM-064363), the National Science Foundation (MCB-1049925) and the Robert F Welch Foundation (F-1274).

References

- 1. Jayaram M, Yang X-M, Mehta S, Voziyanov Y, Velmurugan S. The 2 micron plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. : Plasmid Biology. Funnel BE. and Phillips GJ, eds. Washington DC: Taylor & Francis; 2004; 303-24 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghosh SK, Hajra S, Paek A, Jayaram M. Mechanisms for chromosome and plasmid segregation. Annu Rev Biochem 2006; 75:211-41; PMID:16756491; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Velmurugan S, Yang X-M, Chan CS-M, Dobson M, Jayaram M. Partitioning of the 2-μm circle plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: functional coordination with chromosome segregation and plasmid-encoded Rep protein distribution. J Cell Biol 2000; 149:553-66; PMID:10791970; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.149.3.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heun P, Laroche T, Raghuraman MK, Gasser SM. The positioning and dynamics of origins of replication in the budding yeast nucleus. J Cell Biol 2001; 152:385-400; PMID:11266454; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.152.2.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scott-Drew S, Wong CMVL, Murray JAH. DNA plasmid transmission in yeast is associated with specific sub-nuclear localisation during cell division. Cell Biol Intl 2002; 26:393-405; PMID:12095225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/cbir.2002.0867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Futcher AB. Copy number amplification of the 2 μm circle plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Theor Biol 1986; 119:197-204; PMID:3525993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-5193(86)80074-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volkert FC, Broach JR. Site-specific recombination promotes plasmid amplification in yeast. Cell 1986; 46:541-50; PMID:3524855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90879-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murray JA, Scarpa M, Rossi N, Cesareni G. Antagonistic controls regulate copy number of the yeast 2 micron plasmid. EMBO J 1987; 6:4205-12; PMID:2832156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reynolds AE, Murray AW, Szostak JW. Roles of the 2 micron gene products in stable maintenance of the 2 micron plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1987; 7:3566-73; PMID:3316982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Som T, Armstrong KAF, Volkert C, Broach JR. Autoregulation of 2 micron circle gene expression provides a model for maintenance of stable plasmid copy levels. Cell 1988; 52:27-37; PMID:2449970; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90528-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen XL, Reindle A, Johnson ES. Misregulation of 2 micron circle copy number in a SUMO pathway mutant. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25:4311-20; PMID:15870299; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4311-4320.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xiong L, Chen XL, Silver HR, Ahmed NT, Johnson ES. Deficient SUMO attachment to Flp recombinase leads to homologous recombination-dependent hyperamplification of the yeast 2 micron circle plasmid. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20:1241-51; PMID:19109426; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jayaram M, Grainge I, Tribble G. Site-specific DNA recombination mediated by the Flp protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. : Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, eds. Mobile DNA II. Washington DC: Taylor & Francis; 2002; 192-218 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rice PA. Theme and variation in tyrosine recombinases: structure of a Flp-DNA complex. : Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, eds. Mobile DNA II Washington DC: Taylor & Francis; 2002; 219-29 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Duyne GD. A structural view of tyrosine recombinase site-specific recombination. : Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz AM, eds. Mobile DNA II Washington DC: Taylor & Francis; 2002; 93-117 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turan S, Galla M, Ernst E, Qiao J, Voelkel C, Schiedlmeier B, Zehe C, Bode J. Recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE): traditional concepts and current challenges. J Mol Biol 2011; 407:193-221; PMID:21241707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chang KM, Liu YT, Ma CH, Jayaram M, Sau S. The 2 micron plasmid of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a miniaturized selfish genome with optimized functional competence. Plasmid 2013; 70:2-17; PMID:23541845; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.plasmid.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee T. Generating mosaics for lineage analysis in flies. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol 2014; 3:69-81; PMID:24902835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/wdev.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehta S, Yang XM, Chan CS, Dobson MJ, Jayaram M, Velmurugan S. The 2 micron plasmid purloins the yeast cohesin complex: a mechanism for coupling plasmid partitioning and chromosome segregation? J Cell Biol 2002; 158:625-37; PMID:12177044; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200204136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murray AW, Szostak JW. Pedigree analysis of plasmid segregation in yeast. Cell 1983; 34:961-70; PMID:6354471; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90553-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gehlen LR, Nagai S, Shimada K, Meister P, Taddei A, Gasser SM. Nuclear geometry and rapid mitosis ensure asymmetric episome segregation in yeast. Curr Biol 2011; 21:25-33; PMID:21194950; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shcheprova Z, Baldi S, Frei SB, Gonnet G, Barral Y. A mechanism for asymmetric segregation of age during yeast budding. Nature 2008; 454:728-34; PMID:18660802; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghosh SK, Hajra S, Jayaram M. Faithful segregation of the multicopy yeast plasmid through cohesin-mediated recognition of sisters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:13034-9; PMID:17670945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0702996104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu Y-T, Ma C-H, Jayaram M. Co-segregation of yeast plasmid sisters under monopolin-directed mitosis suggests association of plasmid sisters with sister chromatids. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:4144-58; PMID:23423352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Monje-Casas F, Prabhu VR, Lee BH, Boselli M, Amon A. Kinetochore orientation during meiosis is controlled by aurora B and the monopolin complex. Cell 2007; 128:477-90; PMID:17289568; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehta S, Yang X-M, Jayaram M, Velmurugan S. A novel role for the mitotic spindle during DNA segregation in yeast: promoting 2μm plasmid-cohesin association. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25:4283-98; PMID:15870297; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4283-4298.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Onn I, Heidinger-Pauli JM, Guacci V, Ünal E, Koshland DE. Sister chromatid cohesion: a simple concept with a complex reality. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2008; 24:105-29; PMID:18616427; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nasmyth K. Cohesin: a catenase with separate entry and exit gates? Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:1170-7; PMID:21968990; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murayama Y, Uhlmann F. Biochemical reconstitution of topological DNA binding by the cohesin ring. Nature 2014; 505:367-71; PMID:24291789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature12867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong MC, Scott-Drew SR, Hayes MJ, Howard PJ, Murray JA. RSC2, encoding a component of the RSC nucleosome remodeling complex, is essential for 2 micron plasmid maintenance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22:4218-29; PMID:12024034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4218-4229.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang J, Hsu JM, Laurent BC. The RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex is required for cohesin's association with chromosome arms. Mol Cell 2004; 13:739-50; PMID:15023343; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00103-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hajra S, Ghosh SK, Jayaram M. The centromere-specific histone variant Cse4p (CENP-A) is essential for functional chromatin architecture at the yeast 2-micron circle partitioning locus and promotes equal plasmid segregation. J Cell Biol 2006; 174:779-90; PMID:16966420; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200603042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cui H, Ghosh SK, Jayaram M. The selfish yeast plasmid uses the nuclear motor Kip1p but not Cin8p for its localization and equal segregation. J Cell Biol 2009; 185:251-64; PMID:19364922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200810130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ma C-H, Cui H, Hajra S, Rowley PA, Fekete C, Sarkeshik A, Ghosh SK, Yates JR, 3rd, Jayaram M. Temporal sequence and cell cycle cues in the assembly of host factors at the yeast 2 micron plasmid partitioning locus. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 41:2340-53; PMID:23275556; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gks1338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malik HS, Henikoff S. Major evolutionary transitions in centromere complexity. Cell 2009; 138:1067-82; PMID:19766562; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang C-C, Chang K-M, Cui H, Jayaram M. Histone H3-variant Cse4-induced positive DNA supercoiling in the yeast plasmid has implications for a plasmid origin of a chromosome centromere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:13671-6; PMID:21807992; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1101944108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ghosh SK, Huang C-C, Hajra S, Jayaram M. Yeast cohesin complex embraces 2 micron plasmid sisters in a tri-linked catenane complex. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:570-84; PMID:19920123; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lefrançois P, Auerbach RK, Yellman CM, Roeder GS, Snyder M. Centromere-like regions in the budding yeast genome. PLoS Genet 2013; 9:e1003209; PMID:23349633; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mehta GD, Kumar R, Sreevastava S, Ghosh SK. Cohesin: functions beyond sister chromatid cohesion. FEBS Lett 2013; 587:2299-312; PMID:23831059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jeppsson K, Kanno T, Shirahige K, Sjogren C. The maintenance of chromosome structure: positioning and functioning of SMC complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:601-14; PMID:25145851; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm3857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stephens AD, Haase J, Vicci L, Taylor RM, Bloom K. Cohesin, condensin, and the intramolecular centromere loop together generate the mitotic chromatin spring. J Cell Biol 2011; 193:1167-80; PMID:21708976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201103138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stephens AD, Haggerty RA, Vasquez PA, Vicci L, Snider CE, Shi F, Quammen C, Mullins C, Haase J, Taylor RM 2nd. et al. Pericentric chromatin loops function as a nonlinear spring in mitotic force balance. J Cell Biol 2013; 200:757-72; PMID:23509068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201208163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stephens AD, Quammen CW, Chang B, Haase J, Taylor RM, Bloom K. The spatial segregation of pericentric cohesin and condensin in the mitotic spindle. Mol Biol Cell 2013; 24:3909-19; PMID:24152737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E13-06-0325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stephens AD, Snider CE, Haase J, Haggerty RA, Vasquez PA, Forest MG, et al. Individual pericentromeres display coordinated motion and stretching in the yeast spindle. J Cell Biol 2013; 203:407-16; PMID:24189271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201307104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Preferential inclusion of extrachromosomal genetic elements in yeast meiotic spores. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1980; 77:5380-4; PMID:7001477; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hsiao CL, Carbon J. Direct selection procedure for the isolation of functional centromeric DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981; 78:3760-4; PMID:7022454; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sau S, Conrad MN, Lee C-Y, Kaback DB, Dresser ME, Jayaram M. A selfish DNA element engages a meiosis-specific motor and telomeres for germ-line propagation. J Cell Biol 2014; 205:643-61; PMID:24914236; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201312002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Scherthan H, Wang H, Adelfalk C, White EJ, Cowan C, Cande WZ, Kaback DB. Chromosome mobility during meiotic prophase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:16934-9; PMID:17939997; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0704860104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koszul R, Kim KP, Prentiss M, Kleckner N, Kameoka S. Meiotic chromosomes move by linkage to dynamic actin cables with transduction of force through the nuclear envelope. Cell 2008; 133:1188-201; PMID:18585353; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Conrad MN, Lee C-Y, Chao G, Shinohara M, Kosaka H, Shinohara A, et al. Rapid telomere movement in meiotic prophase is promoted by NDJ1, MPS3, and CSM4 and is modulated by recombination. Cell 2008; 133:1175-87; PMID:18585352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wanat JJ, Kim KP, Koszul R, Zanders S, Weiner B, Kleckner N, et al. Csm4, in collaboration with Ndj1, mediates telomere-led chromosome dynamics and recombination during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet 2008; 4:e1000188; PMID:18818741; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lee CY, Conrad MN, Dresser ME. Meiotic chromosome pairing is promoted by telomere-led chromosome movements independent of bouquet formation. PLoS Genet 2012; 8:e1002730; PMID:22654677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chua PR, Roeder GS. Tam1, a telomere-associated meiotic protein, functions in chromosome synapsis and crossover interference. Genes Dev 1997; 11:1786-800; PMID:9242487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.14.1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Conrad MN, Dominguez AM, Dresser ME. Ndj1p, a meiotic telomere protein required for normal chromosome synapsis and segregation in yeast. Science 1997; 276:1252-5; PMID:9157883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.276.5316.1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Trelles-Sticken E, Dresser ME, Scherthan H. Meiotic telomere protein Ndj1p is required for meiosis-specific telomere distribution, bouquet formation and efficient homologue pairing. J Cell Biol 2000; 151:95-106; PMID:11018056; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.151.1.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Conrad MN, Lee C-Y, Wilkerson JL, Dresser ME. MPS3 mediates meiotic bouquet formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:8863-8; PMID:17495028; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0606165104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kosaka H, Shinohara M, Shinohara A. Csm4-dependent telomere movement on nuclear envelope promotes meiotic recombination. PLoS Genet 2008; 4:e1000196; PMID:18818742; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khmelinskii A, Meurer M, Knop M, Schiebel E. Artificial tethering to nuclear pores promotes partitioning of extrachromosomal DNA during yeast asymmetric cell division. Curr Biol 2011; 21:R17-R8; PMID:21215928; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Piatti S, Bohm T, Cocker JH, Diffley JF, Nasmyth K. Activation of S-phase-promoting CDKs in late G1 defines a "point of no return" after which Cdc6 synthesis cannot promote DNA replication in yeast. Genes Dev 1996; 10:1516-31; PMID:8666235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.10.12.1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jayaram M, Li YY, Broach JR. The yeast plasmid 2 micron circle encodes components required for its high copy propagation. Cell 1983; 34:95-104; PMID:6883512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90139-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kikuchi Y. Yeast plasmid requires a cis-acting locus and two plasmid proteins for its stable maintenance. Cell 1983; 35:487-93; PMID:6317192; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90182-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sym M, Engebrecht J, Roeder GS. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 1993; 72:365-78; PMID:7916652; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90114-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]