Abstract

Physiologically, neurovascular coupling (NVC) matches focal increases in neuronal activity with local arteriolar dilation. Astrocytes participate in NVC by sensing increased neurotransmission and releasing vasoactive agents (e.g., K+) from perivascular endfeet surrounding parenchymal arterioles. Previously, we demonstrated an increase in the amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet and inversion of NVC from vasodilation to vasoconstriction in brain slices obtained from subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) model rats. However, the role of spontaneous astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in determining the polarity of the NVC response remains unclear. Here, we used two-photon imaging of Fluo-4-loaded rat brain slices to determine whether altered endfoot Ca2+ signaling underlies SAH-induced inversion of NVC. We report a time-dependent emergence of endfoot high-amplitude Ca2+ signals (eHACSs) after SAH that were not observed in endfeet from unoperated animals. Furthermore, the percentage of endfeet with eHACSs varied with time and paralleled the development of inversion of NVC. Endfeet with eHACSs were present only around arterioles exhibiting inversion of NVC. Importantly, depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores using cyclopiazonic acid abolished SAH-induced eHACSs and restored arteriolar dilation in SAH brain slices to two mediators of NVC (a rise in endfoot Ca2+ and elevation of extracellular K+). These data indicate a causal link between SAH-induced eHACSs and inversion of NVC. Ultrastructural examination using transmission electron microscopy indicated that a similar proportion of endfeet exhibiting eHACSs also exhibited asymmetrical enlargement. Our results demonstrate that subarachnoid blood causes a delayed increase in the amplitude of spontaneous intracellular Ca2+ release events leading to inversion of NVC.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH)—strokes involving cerebral aneurysm rupture and release of blood onto the brain surface—are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. A common complication observed after SAH is the development of delayed cerebral ischemia at sites often remote from the site of rupture. Here, we provide evidence that SAH-induced changes in astrocyte Ca2+ signaling lead to a switch in the polarity of the neurovascular coupling response from vasodilation to vasoconstriction. Thus, after SAH, signaling events that normally lead to vasodilation and enhanced delivery of blood to active brain regions cause vasoconstriction that would limit cerebral blood flow. These findings identify astrocytes as a key player in SAH-induced decreased cortical blood flow.

Keywords: astrocyte endfeet, calcium signaling, neurovascular coupling, reactive astrocytes, subarachnoid hemorrhage, two-photon imaging

Introduction

Blood flow within the brain parenchyma is dynamically coupled to the ongoing pattern of neuronal activity. Under physiological conditions, stimulus-evoked increases in the frequency of neuronal action potentials elicit vasodilation of nearby parenchymal arterioles. This phenomenon, called functional hyperemia, or neurovascular coupling (NVC), supports brain health by spatially and temporally matching cerebral blood flow to local tissue metabolic demand (Iadecola, 1993; Anderson and Nedergaard, 2003). Astrocytes are key intermediaries in NVC—having projections to neuronal synapses as well as processes (endfeet) that encase parenchymal arterioles (Araque et al., 1999). In response to enhanced neurotransmission, astrocytes release vasoactive substances, including potassium ions (K+), from their endfeet onto adjacent parenchymal arterioles (Zonta et al., 2003; Filosa et al., 2006). The majority of evidence supports a role for increased astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ in mediating neurally evoked vasodilator release (Straub et al., 2006; Attwell et al., 2010; Srinivasan et al., 2015).

In addition to nerve-stimulated increases in Ca2+, spontaneous Ca2+ elevations (200–300 nm in amplitude) lasting several seconds occur in astrocyte endfeet (Koide et al., 2012; Shigetomi et al., 2013). In brain slices from healthy animals, these spontaneous events resulted from IP3-dependent endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ release (Dunn et al., 2013). Presently, the ability of spontaneous Ca2+ signaling to influence NVC and/or the release of vasoactive substances into the restricted perivascular space between endfeet and parenchymal arterioles is unclear. However, we demonstrated previously both an increase in the amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet and inversion of the NVC response from vasodilation to vasoconstriction in brain slices obtained from subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) model rats (Koide et al., 2012; Koide and Wellman, 2015). Interestingly, although the NVC response switched from vasodilation to vasoconstriction, neurally evoked changes in endfoot Ca2+ were not altered by SAH.

Strokes caused by cerebral aneurysm rupture and SAH are associated with a high incidence of morbidity and mortality that often manifest several days after the initial bleed (Al-Khindi et al., 2010; Østergaard et al., 2013). The inversion of NVC may be an important contributor to delayed cerebral ischemia, development of neurological deficits, and poor outcome frequently observed in SAH patients (Koide et al., 2013). The goal of the present study was to determine whether altered spontaneous Ca2+ signaling in astrocyte endfeet plays a causal role in the inversion of NVC after SAH. Here, we report that the time-dependent emergence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ signals in astrocyte endfeet paralleled the occurrence of inversion of NVC in brain slices from SAH model rats. These endfoot high-amplitude Ca2+ signals (eHACSs) were only observed adjacent to arterioles exhibiting inversion of NVC. Importantly, normal arteriolar dilation was restored in brain slices from SAH animals when eHACSs were abolished by depletion of ER Ca2+ stores. These results indicate that subarachnoid blood causes an increase in the amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ signaling events in astrocyte endfeet that leads to inversion of NVC. Furthermore, this work signifies that pathological changes in astrocyte function can profoundly impact cerebral blood flow regulation.

Materials and Methods

Rat SAH model

To mimic aneurysmal SAH, isoflurane-anesthetized Sprague Dawley rats (male, 10–12 weeks old; Charles River Laboratories) received two injections of autologous, unheparinized arterial blood (500 μl drawn from tail artery) into the cisterna magna as described previously (Nystoriak et al., 2011; Koide et al., 2012). Blood injections were given 24 h apart with the exception of animals studied at the 4 and 24 h time points that received only one intracisternal injection. Sham-operated animals underwent identical procedures except that saline, rather than blood, was injected into the cisterna magna. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (eighth edition, 2011) and followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Vermont.

Simultaneous measurements of parenchymal arteriolar diameter and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ in freshly prepared cortical brain slices

Brain slice preparation.

Animals were killed by decapitation while under deep anesthesia with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) at the following time points: 4 h, 24 h, and 2, 4, 7, and 14 d after SAH. Brains were removed from animals and placed in ice-cold aerated (5% CO2/95% O2) artificial CSF (ACSF), and coronal brain slices, 160 μm in thickness, were cut from the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory using a Leica VT1000S vibratome. Brain slices were then incubated with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-4 AM (10 μm) for 1.5 h at 29°C in ACSF containing 0.04% pluronic acid. Using these parameters, Fluo-4 was preferentially loaded into astrocytes (Parri et al., 2001; Kawamura and Kawamura, 2011). In a subset of brain slices, the caged-Ca2+ compound 1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl)-1,2-diaminoethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, tetra(acetoxymethyl ester) (DMNP-EDTA AM, 10 μm) was included with the Fluo-4. Brain slices were then rinsed and maintained in aerated ACSF at room temperature until imaged.

Simultaneous measurements of arteriolar diameter and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+.

Infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) and fluorescent images were simultaneously recorded from brain slices using multiphoton imaging systems coupled to a Coherent Chameleon Ti-Sapphire laser. A Bio-Rad Radiance multiphoton imaging system (excitation wavelength, 820 nm; fluorescent bandpass filter, 575/150 nm; sampling frequency, ∼1 Hz) with an Olympus XLUM PlanF1 20× objective (0.95 NA) was used for the majority of studies. For these experiments, the image size was 512 × 512 pixels, and pixel resolution was 0.12 μm/pixel. For studies requiring the photolysis of caged Ca2+, a Zeiss LSM-7 multiphoton imaging system (excitation, 730 nm; fluorescent bandpass filter, 525/50 nm; sampling frequency, ∼2 Hz) was used with a Zeiss W Plan-APOCHROMAT 20× objective (1.0 NA). The image size for these experiments was 512 × 300 pixels, and pixel resolution was 0.17 μm/pixel. To study NVC, electrical field stimulation (EFS; 50 Hz, 0.3 ms alternating square pulse, 3 s duration) was applied using a pair of platinum wire electrodes (2 mm apart) to trigger neuronal action potentials (Koide et al., 2012). To elevate astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ independent of neuronal activation, we used photolysis of caged Ca2+ or “Ca2+ uncaging” in DMNP-EDTA-loaded slices. Photolysis was achieved using an ∼0.5 s laser pulse of approximately three times the average imaging power to uncage Ca2+ within a selected endfoot (excitation volume, ∼1 μm3). Throughout all recordings, brain slices were continually superfused (∼2 ml/min) with ACSF (aerated with 5% CO2/95% O2, pH ∼7.35, 35−37°C) containing the thromboxane A2 analog 9,11-dideoxy-11α,9α-epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2α (U46619; 100 nm) to induce a physiological level of arteriolar tone (Koide et al., 2012). Parenchymal arteriolar segments (diameter, 3–14 μm before EFS) within the MCA territory, located at a depth of 50–250 μm from the pial surface and surrounded by Fluo-4-loaded endfeet, were chosen for this study. Intraluminal red blood cells were observed in the majority of recordings (89%), and their presence or absence did not correlate with a particular vascular response to EFS or uncaging. At the end of each experiment, brain slices were treated with ionomycin (10 μm) and 20 mm CaCl2 to obtain maximum fluorescence intensity.

Analysis of parenchymal arteriolar diameter.

Using IR-DIC images, the intraluminal parenchymal arteriolar diameter was measured at three evenly spaced points along a 10 μm segment showing the greatest response to stimulation (EFS, Ca2+ uncaging, or 10 mm K+ superfusion). Diameter change, expressed as a percentage increase or decrease from baseline diameter, was determined from 10 s of recording before stimulation and then averaged for the three points of measurement. Diameter measurements were made manually using custom software, SparkAn, written by Dr. A. D. Bonev at the University of Vermont (Burlington, VT).

Analysis of astrocyte endfoot Ca2+.

A region of interest (ROI; 1.2 × 1.2 μm) was placed within an astrocyte endfoot that was either (1) adjacent to an arteriolar segment used to measure diameter change after EFS or Ca2+ uncaging or (2) exhibiting spontaneous Ca2+ events in unstimulated brain slices. Baseline Ca2+ within a ROI was determined by averaging 10 consecutive images before stimulation and/or exhibiting no spontaneous activity. The following criteria were used to define spontaneous Ca2+ events: (1) ≥30% increase in fluorescence intensity for at least two consecutive images (∼2 s) and (2) multiple events observed within a ROI during a 4 min recording. The maximal fluorescence method was used to estimate Ca2+ concentrations within an ROI (Maravall et al., 2000; Koide et al., 2012).

Ultrastructural analysis using electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to examine brain parenchymal arterioles and surrounding astrocyte endfeet in cortical layer 2/3 of the MCA territory (i.e., the same region examined in brain slice studies). Specimens were prepared for TEM using standard procedures (Hayat, 1981). Briefly, unoperated control, 2 d sham-operated, and 2 d SAH model rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and fixed by transcardial perfusion at an intravascular pressure of 75 mmHg using a solution containing 135 mm sucrose, 0.085 mm NaH2PO4, 0.5 mm CaCl2, and 1% glutaraldehyde, pH 7.3. Brains were then dissected from animals and fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde for an additional 24 h. Cortical blocks were cut, rinsed in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, and immersed in 1% OsO4 for 4 h at 4°C, and then dehydrated using a series of graded ethanol and propylene oxide solutions and embedded in Spurr's resin overnight at 60°C. Ultrathin (90 nm) sections obtained using an Ultracut microtome were contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. A Jeol 1400 transmission electron microscope was used to obtain a series of nonoverlapping images (magnification, 5000×) capturing the entire arteriolar circumference. Consistent with previous reports (Mathiisen et al., 2010; McCaslin et al., 2011), the cellular structures providing sheath-like coverage of the abluminal surface of the arteriolar wall were identified as astrocyte endfeet. The distance between endfeet and arteriolar smooth muscle was considered the perivascular space. Endfoot thickness and the perivascular space were measured at 10 random, equally spaced points along the arteriolar circumference using ImageJ (NIH).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n, the number of observations; N, the number of animals). Unpaired Student's two-tailed t test was used for comparisons between two groups. One-way ANOVA followed by either a Tukey or Bonferroni test was used for the post hoc comparison of multiple groups. Chi-squared analysis was used to determine the dependence between variables.

Reagents

U46619, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), and ionomycin were obtained from EMD Millipore. DMNP-EDTA AM was purchased from Interchim. Fluo-4 AM and pluronic acid were obtained from Invitrogen. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The composition of ACSF (in mm) was 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 18 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 glucose, and 0.4 ascorbic acid. ACSF containing 10 mm K+ was made by iso-osmotic replacement of NaCl with KCl.

Results

The emergence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet after SAH

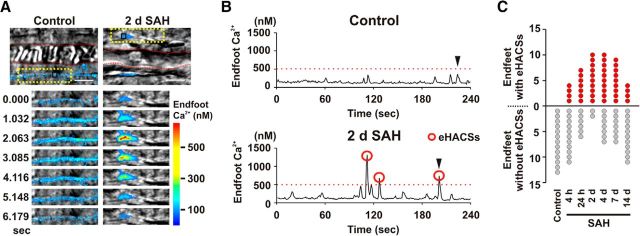

To explore the relationship between the inversion of NVC and the occurrence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ signals in astrocyte endfeet, cortical brain slices from the MCA territory were studied from SAH model rats at six time points following injection of blood into the subarachnoid space (4 h, 24 h, and 2, 4, 7, and 14 d). A subarachnoid blood clot was observed adjacent to the circle of Willis on the ventral surface of the brain between the 4 h and 4 d SAH time points. However, at 7 and 14 d after SAH, the clot was no longer visible. Although remote from the site of blood injection (i.e., cisterna magna), extravascular red blood cells have been observed around parenchymal arterioles from the MCA territory using this model of SAH (Koide et al., 2012). Spontaneous Ca2+ events were imaged using two-photon excitation microscopy and the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4 in astrocyte endfeet surrounding parenchymal arterioles (Fig. 1A,B). Consistent with our previous observation (Koide et al., 2012), SAH led to a significant increase in the overall mean amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ events following SAH (F(6,523) = 5.75; ANOVA, p < 0.0001). Post hoc comparison of the means (Bonferroni) revealed significance at the 24 h and 2, 4, and 7 d SAH time points (p = 0.01, p = 0.0002, p = 0.004, p = 0.03, respectively). With further analysis, we determined that the increased mean amplitudes were due to the emergence of a subpopulation of high-amplitude Ca2+ events not observed in control animals. In brain slices from unoperated control animals, basal endfoot Ca2+ was 128 ± 4 nm, and spontaneous elevations in endfoot Ca2+ did not exceed 500 nm (range, 179 to 496 nm; mean, 303 ± 10 nm; n = 73 events from 13 endfeet). However, in brain slices from SAH animals, we often observed high-amplitude spontaneous events (peak Ca2+, ≥500 nm; eHACSs) in addition to spontaneous Ca2+ increases that were similar in amplitude to those observed in unoperated animals (peak Ca2+, <500 nm; “control-like events”). Thus, after SAH, endfeet fell into one of two categories: (1) endfeet with spontaneous Ca2+ events that were all control-like in amplitude, i.e., with a peak Ca2+ of <500 nm, or (2) endfeet with a combination of eHACSs and control-like spontaneous Ca2+ events. χ2 analysis indicates an association between the incidence of endfeet exhibiting eHACSs and time (4 h, 2 d, 4 d) after SAH (χ2 = 8.839, df = 2, p = 0.012). For example, at the earliest time point (4 h SAH), only ∼27% of endfeet had eHACSs, whereas ∼83% of endfeet were eHACS-positive in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals (Fig. 1C). The mean amplitude (∼700 nm) and frequency of eHACSs were similar at all SAH time points (F(5,83) = 0.81, ANOVA, p = 0.54 and F(5,39) = 1.80, ANOVA, p = 0.14, respectively). When compared with events from control animals, post hoc comparison of the means (Bonferroni) demonstrated that there was no change in the amplitude of control-like spontaneous Ca2+ events at any time points after SAH, regardless of the presence or absence of eHACSs (p > 0.05 in each group; Table 1). These data demonstrate that SAH leads to the time-dependent emergence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ events (i.e., eHACSs) not observed in control animals.

Figure 1.

Emergence of eHACSs following SAH. A, Top, Images of parenchymal arterioles and surrounding astrocyte endfeet in brain slices obtained from control (left) and 2 d SAH model rats (right). The red dashed lines on grayscale IR-DIC images depict the intraluminal diameter. Overlapping pseudocolor-mapped fluorescent Ca2+ images of endfeet were simultaneously acquired using two-photon microscopy. Scale bars, 10 μm. Bottom, Time-lapse images from the area within the yellow dotted box in top panels. B, Spontaneous Ca2+ activity recorded from 1.2 × 1.2 μm regions of interest shown in the black squares in A. Black arrowheads indicate the spontaneous Ca2+ events depicted in the time-lapse series of A. Red circles indicate eHACSs (peak Ca2+ levels of ≥500 nm). C, Number of endfeet with and without eHACSs (red and gray dots, respectively) observed in control (N = 8 animals) and SAH model animals (N = 6–8 animals per time point). Chi-squared analysis indicates an association between the incidence of endfeet exhibiting eHACSs and time (4 h, 2 d, 4 d) after SAH (χ2 = 8.839, df = 2, p = 0.012).

Table 1.

Impact of SAH on spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet

| Control | 4 h SAH | 24 h SAH | 2 d SAH | 4 d SAH | 7 d SAH | 14 d SAH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endfeet without eHACSs | |||||||

| Basal endfoot Ca2+ (nm) | 128 ± 4 | 121 ± 3* | 125 ± 7* | 134 ± 19* | 128 ± 7* | 121 ± 6* | 125 ± 4* |

| Range of Ca2+ event amplitudes (nm) | 179–496 | 166–484 | 161–477 | 214–496 | 208–458 | 192–491 | 187–470 |

| Mean amplitude (nm) | 302 ± 10 | 270 ± 11* | 300 ± 17* | 348 ± 31* | 310 ± 14* | 313 ± 18* | 293 ± 11* |

| Frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ events (Hz) | 0.024 ± 0.003 | 0.021 ± 0.004* | 0.022 ± 0.005* | 0.020 ± 0.011* | 0.017 ± 0.002* | 0.024 ± 0.003* | 0.019 ± 0.004* |

| n, N (endfeet, animals) | 13, 8 | 11, 4 | 6, 5 | 2, 7 | 7, 6 | 7, 5 | 11, 5 |

| Endfeet with eHACSs | |||||||

| Basal endfoot Ca2+ (nm) | 124 ± 7 | 128 ± 3** | 127 ± 4** | 129 ± 4** | 131 ± 6** | 131 ± 4** | |

| Range of Ca2+ event amplitudes (nm) | 181–866 | 229–1618 | 182–1323 | 197–1141 | 195–1244 | 218–871 | |

| Mean amplitude of control-like events (nm) | 294 ± 18 | 321 ± 16** | 312 ± 11** | 292 ± 14** | 289 ± 15** | 356 ± 24** | |

| Mean amplitude of eHACSs (nm) | 605 ± 43 | 738 ± 72** | 691 ± 40** | 769 ± 55** | 770 ± 73** | 758 ± 32** | |

| Frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ events (Hz) | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 0.024 ± 0.005** | 0.034 ± 0.004** | 0.019 ± 0.004** | 0.017 ± 0.002** | 0.019 ± 0.004** | |

| eHACSs (percentage of total events) | 39.5 ± 12.6 | 41.0 ± 3.4** | 37.6 ± 8.5** | 46.6 ± 9.7** | 39.6 ± 8.6** | 32.7 ± 12.1** | |

| n, N (endfeet, animals) | 0, 8 | 4, 4 | 7, 5 | 10, 7 | 10, 6 | 9, 5 | 4, 5 |

| All endfeet | |||||||

| Total spontaneous Ca2+ events | 73 | 81 | 72 | 94 | 78 | 63 | 70 |

One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's test was used for the post hoc comparison of multiple groups.

*p > 0.05 compared to the control group in endfeet without eHACSs;

**p > 0.05 compared to the 4 h SAH group in endfeet with eHACSs.

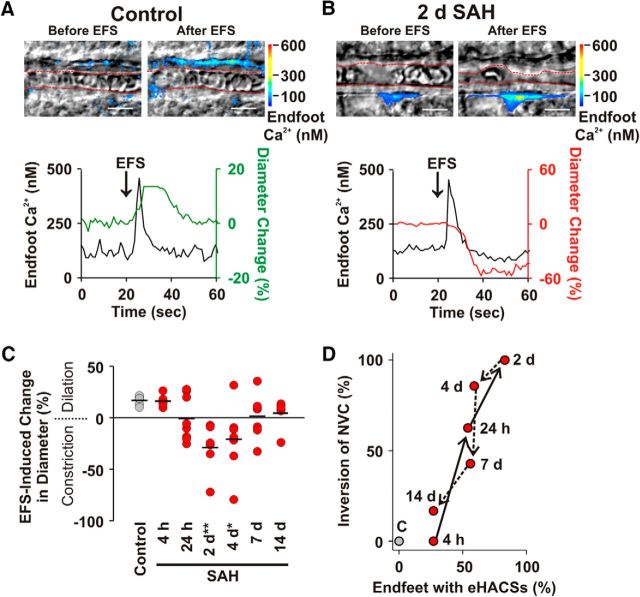

The inversion of NVC parallels the emergence of eHACSs after SAH

We next examined whether the inversion of NVC followed a similar time-dependent pattern of development as that of eHACSs after SAH. In brain slices from control animals, EFS-evoked neuronal activation caused the anticipated NVC response: a rise in astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ followed by vasodilation of the adjacent arteriole (Fig. 2A; n = 6 arterioles, N = 6 animals). Similar vasodilatory NVC responses were observed in all brain slices obtained from 4 h SAH animals (n = 6 arterioles, N = 5 animals). However, EFS-induced vasoconstriction (i.e., inversion of NVC) was observed in brain slices from animals at later SAH time points. Inversion of NVC peaked at 2 d SAH, with 100% of brain slices (n = 7 arterioles, N = 6 animals) exhibiting EFS-induced vasoconstriction, and then steadily declined at later time points (Fig. 2B,C). One-way ANOVA demonstrated a main effect of time after SAH on EFS-evoked changes in arteriolar diameter (F(6,40) = 4.961, p = 0.0007). Post hoc multiple comparisons of the means (Bonferroni) revealed significance at the 2 and 4 d SAH time points (p = 0.001 and p = 0.01, respectively). Although SAH influenced the polarity of EFS-induced vascular responses, evoked increases in endfoot Ca2+ in brain slices from SAH animals were similar to those in the control group (Table 2; F(6,39) = 0.52; ANOVA, p = 0.79). There also was no difference in the mean arteriolar diameter before EFS between groups (F(6,40) = 1.74; ANOVA, p = 0.14). In two instances, one at the 24 h and one at the 7 d SAH time points, we observed opposing vascular responses in brain slices from the same animal, suggesting that inversion of NVC develops and resolves nonuniformly throughout brain cortex. Consistent with our hypothesis that the emergence of eHACSs dictates the polarity of the neurovascular response after SAH, the time course of inversion of NVC was remarkably similar to the time course of the emergence of astrocyte endfeet exhibiting eHACSs (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

The inversion of NVC parallels the emergence of eHACSs in brain slices from SAH model animals. A, B, EFS-induced changes in arteriolar diameter and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ in brain slices from control (A) and 2 d SAH animals (B). Top, IR-DIC images with simultaneously acquired pseudocolored Ca2+ fluorescence maps showing arteriolar diameter (depicted in red dashed line) and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ before and after EFS. Scale bars, 10 μm. Bottom, EFS-evoked changes in endfoot Ca2+ and arteriolar diameter corresponding to the above images. Although EFS caused a similar increase in astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ (black traces), it was associated with vasodilation (green trace) in brain slices from control animals and vasoconstriction (red trace) in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals. C, Summary of EFS-induced arteriolar responses in brain slices from control and SAH model animals. Black lines represent the mean change in diameter per study group (n = 6–8 arterioles from 4–6 animals per group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni's post hoc test). D, Relationship between the percentage of endfeet with eHACSs and the percentage of arterioles exhibiting inversion of NVC at various time points after induction of SAH. Arrows demonstrate the progression of time.

Table 2.

Impact of SAH on NVC

| Control | 4 h SAH | 24 h SAH | 2 d SAH | 4 d SAH | 7 d SAH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain slices with intact NVC (i.e. arteriolar dilation) | ||||||

| Arteriolar diameter before EFS (μm) | 8.7 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 6.8 | 8.3 ± 0.8 | |

| Endfoot Ca2+ before EFS (nm) | 139 ± 19 | 127 ± 8 | 137 ± 8 | 137 | 128 ± 6 | |

| Endfoot Ca2+ after EFS (nm) | 421 ± 39 | 427 ± 30 | 404 ± 32 | 388 | 378 ± 38 | |

| n, N (slices, animals) | 6, 6 | 6, 5 | 3, 4 | 0, 5 | 1, 5 | 4, 6 |

| Brain slices with inversion of NVC (i.e. arteriolar constriction) | ||||||

| Arteriolar diameter before EFS (μm) | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 1.5 | 9.2 ± 1.6 | 5.1 ± 1.0 | ||

| Endfoot Ca2+ before EFS (nm) | 128 ± 6 | 128 ± 4 | 135 ± 3 | 122 ± 5 | ||

| Endfoot Ca2+ after EFS (nm) | 361 ± 16 | 377 ± 24 | 394 ± 37 | 440 ± 15 | ||

| n, N (slices, animals) | 0, 6 | 0, 5 | 5, 4 | 7, 5 | 6, 5 | 3, 6 |

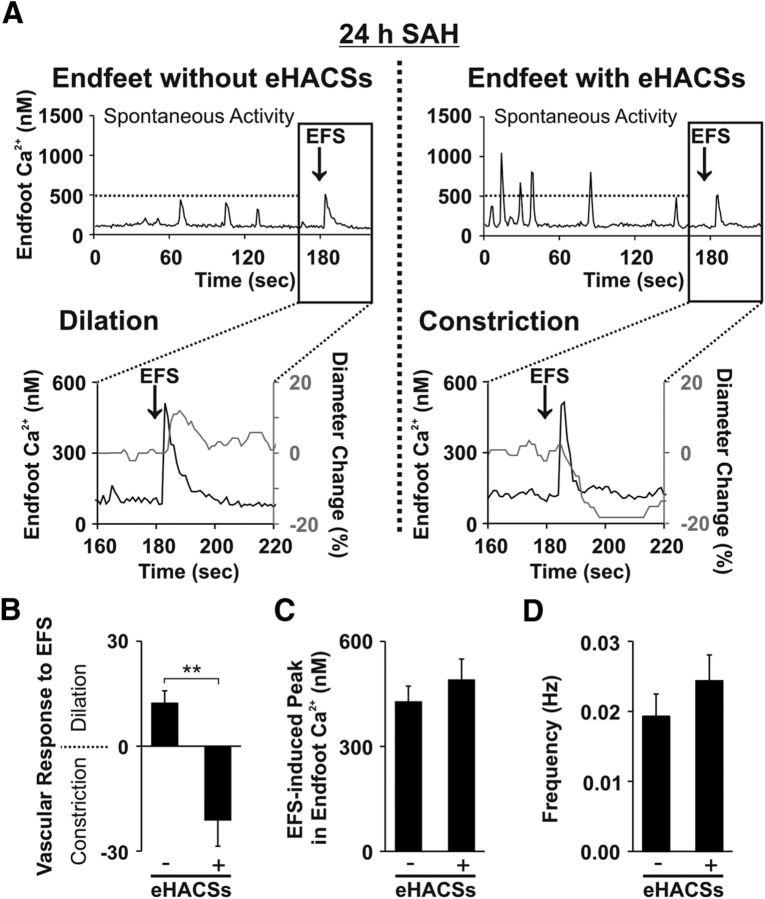

To further explore causality between the emergence of eHACSs and inversion of NVC, we captured both phenomena in single continuous recordings (3 min recording of spontaneous activity followed by EFS) of brain slices obtained from 24 h SAH animals. Here, we chose to study the 24 h SAH time point because approximately half of the brain slices from these animals exhibited normal NVC (EFS-induced vasodilation), whereas the remaining slices exhibited inversion of NVC (EFS-induced vasoconstriction). As anticipated, endfeet in brain slices from 24 h SAH animals displayed either only control-like spontaneous Ca2+ events (i.e., no eHACSs) or exhibited a combination of control-like events and eHACSs during the initial 3 min of recordings capturing spontaneous Ca2+ events (Fig. 3A). EFS-induced vasodilation (12 ± 4% increase in diameter, n = 4 arterioles, N = 4 animals) occurred in all brain slices exhibiting only control-like spontaneous Ca2+ events (mean amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ events, 284 ± 16 nm; range, 189–485 nm; 32 events in four brain slices from four animals; Fig. 3B). Conversely, inversion of NVC (EFS-induced vasoconstriction, 17 ± 7% decrease in diameter, n = 5 arterioles, N = 5 animals) was observed in all brain slices containing eHACS-positive endfeet (71 events in five brain slices from five animals; Fig. 3B). The presence or absence of eHACSs did not impact EFS-evoked increases in astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ or the overall frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ events (Fig. 3C,D; p = 0.46 and p = 0.33, respectively; two-tailed t test). In two cases, brain slices with endfeet exhibiting eHACSs also had endfeet where eHACSs were not observed along the same arteriolar segment. These results are consistent with the emergence of eHACSs causing inversion of NVC after SAH.

Figure 3.

The presence of eHACSs is associated with inversion of NVC. A, Continuous, in tandem recordings of spontaneous Ca2+ events and EFS-evoked changes in arteriolar diameter and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ from brain slices of 24 h SAH animals. In brain slices with endfeet lacking eHACSs (left), EFS triggered a rise in endfoot Ca2+ and vasodilation of the adjacent arteriole. However, when eHACSs were present in the surrounding endfeet (right), a similar EFS-evoked rise in endfoot Ca2+ elicited vasoconstriction (i.e., inversion of NVC). B, Summary of EFS-induced changes in arteriolar diameter in brains slices with and without endfeet exhibiting eHACSs (n = 4 or 5 arterioles, N = 4 or 5 animals). **p < 0.01 (two-tailed t test). C, Summary of the EFS-induced rise in endfoot Ca2+ in brain slices with or without eHACSs (n = 7–11 endfeet, N = 4 or 5 animals). D, Summary of the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ events in brain slices with or without eHACSs (n = 7–11 endfeet, N = 4 or 5 animals).

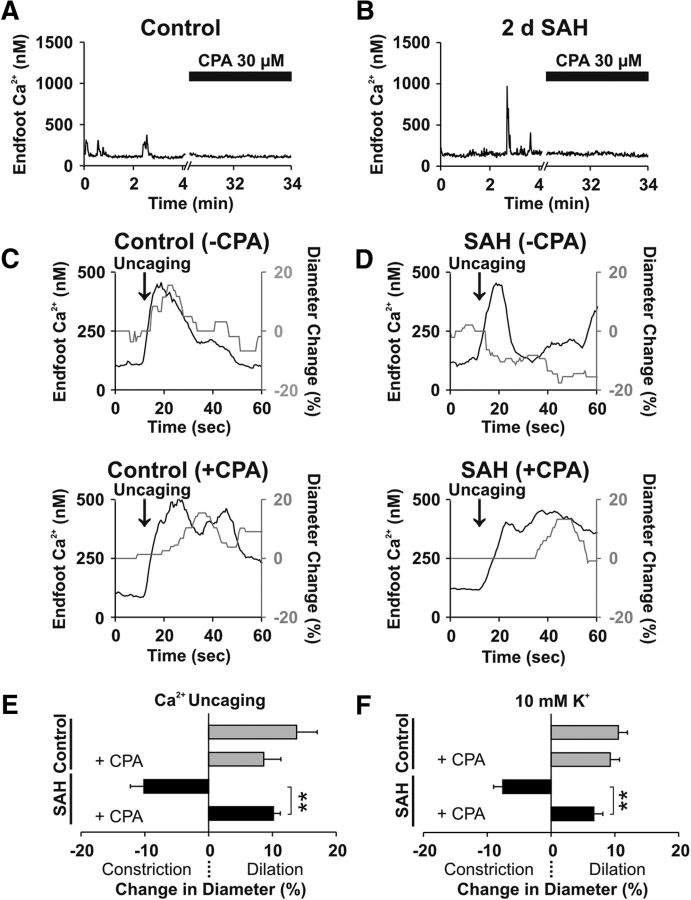

Abolition of eHACSs restores vasodilatory responses in brain slices from SAH animals

Release of Ca2+ from the ER underlies the generation of spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet of healthy animals (Dunn et al., 2013). To examine the role of ER Ca2+ release in the generation of eHACSs, CPA, a selective sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor, was used to deplete astrocyte ER Ca2+ stores. In brain slices from control animals, CPA treatment (30 μm, 25 min) abolished spontaneous endfoot Ca2+ events (Fig. 4A), as expected. Importantly, CPA also abolished all spontaneous Ca2+ signals, including eHACSs, in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals, indicating that SAH-induced eHACSs are mediated via ER Ca2+ release (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Abolishing eHACSs restores arteriolar dilation in brain slices from SAH animals. A, B, Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with CPA (30 μm) treatment abolished spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet from control and 2 d SAH animals (n = 5–6 endfeet per group, N = 4 animals per group). C, D, Changes in endfoot Ca2+ and arteriolar diameter evoked by photolysis (uncaging) of caged Ca2+ in brain slices from control (C) and 2 d SAH animals (D), with (top) or without (bottom) spontaneous Ca2+ signals, i.e., with or without CPA treatment. E, Summary data depicting the percentage change in arteriolar diameter induced by Ca2+ uncaging in the presence or absence of CPA (n = 4 arterioles per group, N = 3–4 animals per group). F, Summary data depicting the percentage change in diameter evoked by increasing extracellular K+ in ACSF superfusate from 3 to 10 mm in the presence or absence of CPA (n = 6–10 arterioles per group, N = 4 or 5 animals per group). **p < 0.01 (two-tailed t test).

Using CPA to deplete ER Ca2+, we next examined whether the elimination of SAH-induced eHACSs could restore vasodilatory responses typical of NVC. However, because EFS-evoked vasodilation is also dependent on astrocyte endfoot ER Ca2+ release (Straub et al., 2006), we targeted two elements downstream of neuronal activation in the NVC signaling cascade (increased endfoot Ca2+ and elevated perivascular K+). First, two-photon photolysis of caged Ca2+ was used to induce a focal (excitation volume, ∼1 μm3) rise in endfoot Ca2+. Consistent with EFS-induced vascular responses (Fig. 2), uncaging Ca2+ in astrocyte endfeet in the absence of CPA caused a similar amplitude endfoot Ca2+ transient in all brain slices (control, 436 ± 35 nm; SAH, 417 ± 32 nm; p = 0.47, two-tailed t test), but caused vasodilation in brain slices from control animals and vasoconstriction in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals. Treatment of brain slices from control animals with CPA did not affect vasodilation induced by photolysis of caged Ca2+ in astrocyte endfeet (Fig. 4C; p = 0.243, two-tailed t test). However, in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals, CPA treatment (i.e., abolishing eHACSs) reversed Ca2+ uncaging responses from constriction to dilation (Fig. 4D; p < 0.0001, two-tailed t test). In the presence of CPA, the amplitude of endfoot Ca2+ transients induced by uncaging Ca2+ were again similar between groups (control, 365 ± 53 nm; SAH, 310 ± 50 nm; p = 0.83, two-tailed t test). These results indicate that abolishing eHACSs restored normal astrocyte–vascular signaling in brain slices from SAH animals (Fig. 4E).

Modest increases in the extracellular/perivascular K+ concentration play an important role in astrocyte-to-smooth muscle communication during NVC (Filosa et al., 2006; Girouard et al., 2010). Typically, neurally evoked increases in endfoot Ca2+ activate large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels on astrocyte endfeet, causing an estimated 5–10 mm increase in perivascular K+ and vasodilation via activation of smooth muscle strong inwardly rectifying K+ (KIR) channels (Filosa et al., 2006; Girouard et al., 2010). Previous studies mimicked neurally evoked endfoot K+ efflux by increasing the K+ concentration in the brain slice superfusate from 3 to 10 mm (Filosa et al., 2006; Girouard et al., 2010; Koide et al., 2012). Here, we examined the effect of K+-induced changes in arteriolar diameter in brain slices obtained from control and 2 d SAH animals in the presence and absence of endfoot spontaneous Ca2+ events. Similar to the inversion of NVC, increasing extracellular K+ from 3 to 10 mm in brain slices with intact astrocyte ER Ca2+ (i.e., endfeet exhibiting spontaneous Ca2+ events) caused arteriolar dilation in brain slices from unoperated animals and vasoconstriction in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals. As with Ca2+ uncaging, abolishing spontaneous Ca2+ events with CPA (30 μm, 25 min) restored arteriolar dilation in response to 10 mm extracellular K+ in brain slices from 2 d SAH animals and had no effect on K+-induced vasodilation in brain slices from control animals (Fig. 4F; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.56, respectively; two-tailed t test). Thus, abolishing eHACSs restored vasodilatory responses in brain slices after SAH.

Asymmetrical enlargement of perivascular astrocyte endfeet after SAH

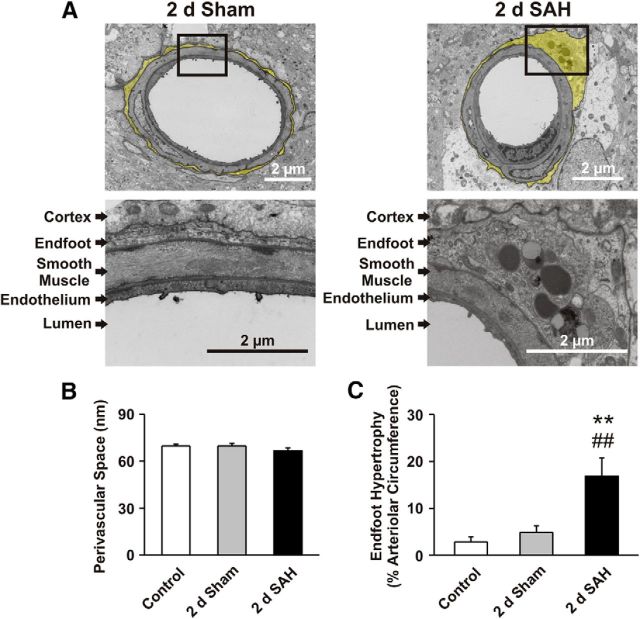

CNS pathologies such as traumatic brain injury, ischemic stroke, and SAH are associated with astrocyte hypertrophy and reactive gliosis (Murakami et al., 2011; Burda and Sofroniew, 2014). To explore the impact of SAH on the ultrastructure of the gliovascular interface (i.e., astrocyte endfeet and parenchymal arterioles), we used TEM to image brain cortex from control, 2 d sham-operated, and 2 d SAH model animals. Astrocyte endfeet surrounding parenchymal arterioles from control and sham-operated animals exhibited a thin, uniform, sheath-like morphology (Fig. 5A). In contrast, perivascular endfeet of SAH animals exhibited regions of asymmetrical thickening that contained numerous subcellular organelles, including lysosomes (Fig. 5A). Lysosomes were observed in 12 of 16 endfeet after SAH, but were not observed in endfeet from control or sham-operated animals. Remarkably, in 2 d SAH animals, the percentage of endfeet exhibiting asymmetrical hypertrophy (∼81%, 13 of 16 endfeet) was similar to the percentage of endfeet exhibiting eHACSs (∼83%; Fig. 1D). Using a threshold of three times the mean thickness of control endfeet (∼690 nm), we determined that ∼17% of the arteriolar circumference is surrounded by an enlarged endfoot after SAH (Fig. 5C; Tukey's test, p < 0.0001 vs control, p = 0.0008 vs sham). Interestingly, despite enlargement of endfoot processes, the distances measured between the endfeet and arteriolar smooth muscle (i.e., the perivascular space) in these samples were similar between groups (∼70 nm; F(2,627) = 1.17; ANOVA, p = 0.31; Fig. 5B). These results suggest a possible link between structural changes in perivascular endfeet after SAH and altered endfoot Ca2+ signaling (i.e., eHACSs).

Figure 5.

Astrocyte endfeet with asymmetrical hypertrophy encase parenchymal arterioles following SAH. A, Top, Low-magnification TEM images of parenchymal arterioles in cerebral cortices obtained from 2 d sham-operated and 2 d SAH model animals. Astrocyte endfeet are highlighted in yellow. Bottom, High-magnification images of the arteriolar wall (endothelial and smooth muscle cell layers) as well as the surrounding astrocyte endfoot from within the black boxes. Lysosomes (round electron-dense structures) were observed only in areas of enlarged endfeet from SAH animals. B, Distance between astrocyte endfeet and arteriolar smooth muscle (i.e., width of the perivascular space) measured at 10 random equally spaced locations along the arteriolar circumference (n = 16–27 arterioles per group, N = 4 or 5 animals per group). C, Summary of endfoot hypertrophy. Data are presented as the percentage of the arteriolar circumference surrounded by an enlarged endfoot (i.e., >3 times the mean thickness of control endfeet; n = 16–27 arterioles per group, N = 4 or 5 animals per group). **p < 0.01 versus control, ##p < 0.01 versus sham (one-way AONVA followed by Tukey's test).

Discussion

This study provides evidence that the emergence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ events within astrocyte endfeet underlies SAH-induced inversion of NVC. High-amplitude Ca2+ signals, or eHACSs, were absent in brain slices from unoperated control animals and were present only in endfeet surrounding arterioles exhibiting inversion of NVC. Furthermore, abolishing eHACSs through pharmacologic depletion of ER Ca2+ restored typical vasodilatory responses to two elements involved in the NVC signaling cascade—increased endfoot Ca2+ and modest elevation of extracellular K+. BK channels, localized to the endfoot membrane (Price et al., 2002), are the most likely Ca2+ sensor responsible for transducing eHACSs into a pathological vascular response. Astrocyte BK channels are an important component of neurovascular communication (Filosa et al., 2006; Girouard et al., 2010; Koide et al., 2012) and contain auxiliary β4 subunits (Seidel et al., 2011) conferring a high level of Ca2+ sensitivity to these channels (Horrigan and Aldrich, 2002; Bai et al., 2011). Thus, considering the Ca2+ sensitivity and large single channel conductance of BK channels, it is likely that SAH-induced eHACSs cause a substantial increase in BK-mediated K+ efflux. Because the restricted perivascular space between endfeet and arteriolar myocytes is estimated to be <100 nm (Nagelhus et al., 1999; Fig. 5B), relatively small changes in the number of K+ ions would significantly impact the K+ concentration within the microdomain surrounding parenchymal arterioles (Girouard et al., 2010). Cerebral arteries are highly sensitive to changes in extracellular K+ (Knot et al., 1996; Zaritsky et al., 2000). Modest increases in extracellular K+ (≤20 mm) cause arteriolar dilation via activation of smooth muscle KIR channels (Knot et al., 1996; Filosa et al., 2006; Girouard et al., 2010). However, larger increases (>20 mm) cause a depolarizing shift in the K+ equilibrium potential of smooth muscle that leads to enhanced Ca2+ entry through L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and arteriolar constriction (Knot and Nelson, 1998). Our previous work indicates that SAH-induced inversion of NVC is a result of abnormally elevated basal perivascular K+ that, when combined with neurally evoked K+ efflux, leads to smooth muscle membrane potential depolarization and a switch in the polarity of the vascular response from dilation to constriction (Koide et al., 2012). We now demonstrate that altered spontaneous Ca2+ signaling in the form of eHACSs dictates the polarity of NVC after SAH. These results are consistent with the concept that SAH-induced eHACSs enhance BK channel activity in the endfeet, causing an increase in basal perivascular K+ and inversion of NVC.

This work expands upon a growing body of research indicating that SAH-induced cortical infarcts and poor clinical outcome are due to disruption of blood flow within the brain microcirculation (Dreier et al., 2002; Ishiguro et al., 2002; Rabinstein et al., 2005; Pluta et al., 2009; Nystoriak et al., 2011; Østergaard et al., 2013). Microvasculature dysfunction after SAH would be predicted to cause cerebral infarction in relatively small, spatially defined regions due to the paucity of collaterals within the brain parenchyma (Nishimura et al., 2007). Roughly 60% of patients exhibit diffuse ischemic brain lesions following SAH (Hijdra et al., 1986). Furthermore, it has been suggested that the mechanism underlying diffuse brain injury differs from that which causes cell death near the site of aneurysm rupture (Rabinstein et al., 2005). Although neuronal viability was not directly examined in the current study, the inversion of NVC likely precedes substantial cell death or neuronal injury after SAH, as EFS-evoked changes in endfoot Ca2+ were comparable in brain slices from control and SAH animals. Previous studies have also shown altered ion channel function and/or expression in vascular smooth muscle cells following exposure to the blood component oxyhemoglobin (Ishiguro et al., 2005; Wellman, 2006; Link et al., 2008). Thus, it is possible that ischemic events following SAH result from the combined effects of inversion of NVC and other actions of SAH, including a direct increase in arteriolar smooth muscle contractility (Nystoriak et al., 2011). Future studies will be required to establish the contribution of pathological astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and inversion of NVC to the development of delayed cerebral ischemia following SAH.

Astrocytes typically respond to CNS perturbations (including SAH) by undergoing a characteristic hypertrophy known as reactive gliosis (Murakami et al., 2011; Burda and Sofroniew, 2014). Although the morphological and molecular changes associated with reactive gliosis are well described (Sofroniew, 2009), the functional consequences remain unclear. Previous in vivo measurements of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling using a mouse model of familial Alzheimer's disease demonstrated a “hyperactive” Ca2+ signaling phenotype in reactive astrocytes (Delekate et al., 2014). Importantly, the aberrant Ca2+ signals present in endfeet were associated with spontaneous vasoconstrictions of the neighboring arterioles. These data provide an interesting parallel between the phenomena we observe after SAH (i.e., emergence of endfeet exhibiting eHACSs, inversion of NVC, and asymmetrical endfoot hypertrophy) and the functional alterations observed in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

The results from our TEM studies demonstrated asymmetrical enlargement of astrocyte endfeet following SAH. Although endfoot swelling has been suggested to compress cerebral microvessels after SAH (Østergaard et al., 2013), it is unlikely that the endfoot enlargement we report directly caused arteriolar narrowing, as we detected no change in arteriolar diameter before EFS at any time points after SAH (Table 2). Furthermore, we found no change in the width of the perivascular space using TEM (Fig. 5). However, these static TEM measurements of the perivascular space were made using perfusion-fixed tissue susceptible to spacing artifacts. It is also important to consider that the perivascular space surrounding parenchymal arterioles provides a critical and dynamic conduit for the exchange of CSF with brain interstitial fluid (ISF; Iliff et al., 2012, 2013). Considering previous work showing that increased arousal decreases ISF–CSF fluid exchange (Xie et al., 2013), it is possible that increases in arteriolar diameter during vasodilatory NVC coincide with decreases in perivascular volume. Conversely, vasoconstrictive NVC would be predicted to increase perivascular volume and enhance ISF–CSF exchange. Thus, it is conceivable that the inversion of NVC after SAH represents an adaptive response promoting the clearance of bloody CSF.

Our data indicate that SAH-induced high-amplitude Ca2+ signaling events, in the form of eHACSs, result from increased Ca2+ release from subcellular ER stores (Fig. 4). However, the cellular basis underlying the enhanced release of Ca2+ after SAH remains to be determined. An increase in ER Ca2+ load or increased expression/sensitivity of IP3 receptors could potentially contribute to the emergence of eHACSs after SAH. However, increased production of IP3 could also underlie SAH-induced eHACSs. It is generally appreciated that endfoot Ca2+ signals result from activation of Gq-coupled receptors and the production of IP3 (Fiacco and McCarthy, 2006; Straub et al., 2006). Astrocytes express a multitude of Gq-coupled receptors that could play a role in the generation of eHACSs. Previously, purinergic signaling was implicated in the hyperactive Ca2+ signaling phenotype observed in reactive astrocytes in an Alzheimer's disease model (Delekate et al., 2014). Furthermore, the Gq-coupled purinergic receptors P2Y2 and P2Y4 are expressed in astrocyte endfeet (Simard et al., 2003), and upregulation of purinergic signaling has been implicated after SAH (Kasseckert et al., 2013). Interestingly, astrocyte lysosomes are capable of ATP release (Zhang et al., 2007), and we observed organelles appearing to be lysosomes in endfeet of SAH animals, but not control animals (Fig. 5A). There is strong evidence from Alzheimer's disease models that astrocyte lysosomes are involved in the clearance of β-amyloid plaques (Funato et al., 1998; Wyss-Coray et al., 2003). Considering the distribution of red blood cells and blood products along the parenchymal arteriolar walls after SAH (Koide et al., 2012), the presence of enlarged endfeet containing lysosomes in our TEM samples may indicate a role for astrocytes in the clearance of extravascular blood components. However, future studies are necessary to determine the role of reactive astrogliosis and purinergic signaling in the development of SAH-induced eHACSs and inversion of NVC.

In summary, our results indicate a causal link between the emergence of high-amplitude spontaneous Ca2+ events in astrocyte endfeet (i.e., eHACSs) and SAH-induced inversion of NVC. These findings identify astrocytes as a key player in SAH-induced disruption of cortical blood flow. Further work targeting the impact of SAH on astrocyte function may lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies to treat brain pathologies such as hemorrhagic stroke.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HL095488, P01 HL095488 03S1, P30 GM10398, and S10 OD 010583; American Heart Association Grant 14SGD20150027; the Totman Medical Research Trust, and the Peter Martin Brain Aneurysm Endowment. We thank Ms. S.R. Russell and Drs. M.T. Nelson, A.D. Bonev, and D.J. Taatjes for their assistance with this study and acknowledge the University of Vermont Neuroscience Center of Biomedical Research Excellence imaging core facility.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Al-Khindi T, Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Cognitive and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41:e519–e536. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral microcirculation. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:340–344. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:208–215. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, Lauritzen M, Macvicar BA, Newman EA. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature. 2010;468:232–243. doi: 10.1038/nature09613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai JP, Surguchev A, Navaratnam D. β4-subunit increases Slo responsiveness to physiological Ca2+ concentrations and together with β1 reduces surface expression of Slo in hair cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C435–C446. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00449.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JE, Sofroniew MV. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron. 2014;81:229–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delekate A, Füchtemeier M, Schumacher T, Ulbrich C, Foddis M, Petzold GC. Metabotropic P2Y1 receptor signalling mediates astrocytic hyperactivity in vivo in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5422. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier JP, Sakowitz OW, Harder A, Zimmer C, Dirnagl U, Valdueza JM, Unterberg AW. Focal laminar cortical MR signal abnormalities after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:825–829. doi: 10.1002/ana.10383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KM, Hill-Eubanks DC, Liedtke WB, Nelson MT. TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6157–6162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216514110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA, McCarthy KD. Astrocyte calcium elevations: properties, propagation, and effects on brain signaling. Glia. 2006;54:676–690. doi: 10.1002/glia.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Straub SV, Meredith AL, Wilkerson MK, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1397–1403. doi: 10.1038/nn1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funato H, Yoshimura M, Yamazaki T, Saido TC, Ito Y, Yokofujita J, Okeda R, Ihara Y. Astrocytes containing amyloid β-protein (Aβ)-positive granules are associated with Aβ40-positive diffuse plaques in the aged human brain. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:983–992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girouard H, Bonev AD, Hannah RM, Meredith A, Aldrich RW, Nelson MT. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3811–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914722107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat MA. Fixation for electron microscopy. New York: Academic; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hijdra A, Van Gijn J, Stefanko S, Van Dongen KJ, Vermeulen M, Van Crevel H. Delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: clinicoanatomic correlations. Neurology. 1986;36:329–333. doi: 10.1212/WNL.36.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrigan FT, Aldrich RW. Coupling between voltage sensor activation, Ca2+ binding and channel opening in large conductance (BK) potassium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:267–305. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C. Regulation of the cerebral microcirculation during neural activity: is nitric oxide the missing link? Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:206–214. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90156-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, Benveniste H, Vates GE, Deane R, Goldman SA, Nagelhus EA, Nedergaard M. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:147ra111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff JJ, Wang M, Zeppenfeld DM, Venkataraman A, Plog BA, Liao Y, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Cerebral arterial pulsation drives paravascular CSF-interstitial fluid exchange in the murine brain. J Neurosci. 2013;33:18190–18199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1592-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro M, Puryear CB, Bisson E, Saundry CM, Nathan DJ, Russell SR, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Enhanced myogenic tone in cerebral arteries from a rabbit model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2217–H2225. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00629.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro M, Wellman TL, Honda A, Russell SR, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Emergence of a R-type Ca2+ channel (CaV 2.3) contributes to cerebral artery constriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circ Res. 2005;96:419–426. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000157670.49936.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasseckert SA, Shahzad T, Miqdad M, Stein M, Abdallah Y, Scharbrodt W, Oertel M. The mechanisms of energy crisis in human astrocytes after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2013;72:468–474. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827d0de7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura M, Jr, Kawamura M. Long-term facilitation of spontaneous calcium oscillations in astrocytes with endogenous adenosine in hippocampal slice cultures. Cell Calcium. 2011;49:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol. 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Zimmermann PA, Nelson MT. Extracellular K+-induced hyperpolarizations and dilatations of rat coronary and cerebral arteries involve inward rectifier K+ channels. J Physiol. 1996;492:419–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide M, Wellman GC. Activation of TRPV4 channels does not mediate inversion of neurovascular coupling after SAH. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2015;120:111–116. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04981-6_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Wellman GC. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1387–E1395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide M, Sukhotinsky I, Ayata C, Wellman GC. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, spreading depolarizations and impaired neurovascular coupling. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:819340. doi: 10.1155/2013/819340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link TE, Murakami K, Beem-Miller M, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Oxyhemoglobin-induced expression of R-type Ca2+ channels in cerebral arteries. Stroke. 2008;39:2122–2128. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.508754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys J. 2000;78:2655–2667. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76809-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiisen TM, Lehre KP, Danbolt NC, Ottersen OP. The perivascular astroglial sheath provides a complete covering of the brain microvessels: an electron microscopic 3D reconstruction. Glia. 2010;58:1094–1103. doi: 10.1002/glia.20990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaslin AF, Chen BR, Radosevich AJ, Cauli B, Hillman EM. In vivo 3D morphology of astrocyte-vasculature interactions in the somatosensory cortex: implications for neurovascular coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:795–806. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Koide M, Dumont TM, Russell SR, Tranmer BI, Wellman GC. Subarachnoid hemorrhage induces gliosis and increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine high mobility group box 1 protein. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:72–79. doi: 10.1007/s12975-010-0052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelhus EA, Horio Y, Inanobe A, Fujita A, Haug FM, Nielsen S, Kurachi Y, Ottersen OP. Immunogold evidence suggests that coupling of K+ siphoning and water transport in rat retinal Muller cells is mediated by a coenrichment of Kir4.1 and AQP4 in specific membrane domains. Glia. 1999;26:47–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199903)26:1<47::AID-GLIA5>3.0.CO%3B2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, Lyden PD, Kleinfeld D. Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:365–370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609551104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystoriak MA, O'Connor KP, Sonkusare SK, Brayden JE, Nelson MT, Wellman GC. Fundamental increase in pressure-dependent constriction of brain parenchymal arterioles from subarachnoid hemorrhage model rats due to membrane depolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H803–H812. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00760.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard L, Aamand R, Karabegovic S, Tietze A, Blicher JU, Mikkelsen IK, Iversen NK, Secher N, Engedal TS, Anzabi M, Jimenez EG, Cai C, Koch KU, Naess-Schmidt ET, Obel A, Juul N, Rasmussen M, Sørensen JC. The role of the microcirculation in delayed cerebral ischemia and chronic degenerative changes after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1825–1837. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V. Spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations in situ drive NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:803–812. doi: 10.1038/90507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluta RM, Hansen-Schwartz J, Dreier J, Vajkoczy P, Macdonald RL, Nishizawa S, Kasuya H, Wellman G, Keller E, Zauner A, Dorsch N, Clark J, Ono S, Kiris T, Leroux P, Zhang JH. Cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage: time for a new world of thought. Neurol Res. 2009;31:151–158. doi: 10.1179/174313209X393564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Ludwig JW, Mi H, Schwarz TL, Ellisman MH. Distribution of rSlo Ca2+-activated K+ channels in rat astrocyte perivascular endfeet. Brain Res. 2002;956:183–193. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinstein AA, Weigand S, Atkinson JL, Wijdicks EF. Patterns of cerebral infarction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:992–997. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000163090.59350.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel KN, Derst C, Salzmann M, Höltje M, Priller J, Markgraf R, Heinemann SH, Heilmann H, Skatchkov SN, Eaton MJ, Veh RW, Prüss H. Expression of the voltage- and Ca2+-dependent BK potassium channel subunits BKβ1 and BKβ4 in rodent astrocytes. Glia. 2011;59:893–902. doi: 10.1002/glia.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigetomi E, Bushong EA, Haustein MD, Tong X, Jackson-Weaver O, Kracun S, Xu J, Sofroniew MV, Ellisman MH, Khakh BS. Imaging calcium microdomains within entire astrocyte territories and endfeet with GCaMPs expressed using adeno-associated viruses. J Gen Physiol. 2013;141:633–647. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, Liu QS, Nedergaard M. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9254–9262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09254.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofroniew MV. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Huang BS, Venugopal S, Johnston AD, Chai H, Zeng H, Golshani P, Khakh BS. Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes from IP3R2(−/−) mice in brain slices and during startle responses in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:708–717. doi: 10.1038/nn.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub SV, Bonev AD, Wilkerson MK, Nelson MT. Dynamic inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium signals within astrocytic endfeet underlie vasodilation of cerebral arterioles. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:659–669. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman GC. Ion channels and calcium signaling in cerebral arteries following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2006;28:690–702. doi: 10.1179/016164106X151972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyss-Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, Lu E, Anankov R, Yan F, Silverstein SC, Husemann J. Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid-β in vitro and in situ. Nat Med. 2003;9:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nm838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O'Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T, Deane R, Nedergaard M. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science. 2013;342:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1241224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaritsky JJ, Eckman DM, Wellman GC, Nelson MT, Schwarz TL. Targeted disruption of Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 genes reveals the essential role of the inwardly rectifying K+ current in K+-mediated vasodilation. Circ Res. 2000;87:160–166. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen G, Zhou W, Song A, Xu T, Luo Q, Wang W, Gu XS, Duan S. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:945–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zonta M, Angulo MC, Gobbo S, Rosengarten B, Hossmann KA, Pozzan T, Carmignoto G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nn980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]