Abstract

In this report, we investigated the consequences of neonatal progesterone exposure on adult rat uterine function. Female pups were subcutaneously injected with vehicle or progesterone from postnatal days 3 to 9. Early progesterone exposure affected endometrial gland biogenesis, puberty, decidualization, and fertility. Because decidualization and pregnancy success are directly linked to progesterone action on the uterus, we investigated the responsiveness of the adult uterus to progesterone. We first identified progesterone-dependent uterine gene expression using RNA sequencing and quantitative RT-PCR in Holtzman Sprague-Dawley rats and progesterone-resistant Brown Norway rats. The impact of neonatal progesterone treatment on adult uterine progesterone responsiveness was next investigated using quantitative RT-PCR. Progesterone resistance affected the spectrum and total number of progesterone-responsive genes and the magnitude of uterine responses for a subset of progesterone targets. Several progesterone-responsive genes in adult uterus exhibited significantly dampened responses in neonatally progesterone-treated females compared with those of vehicle-treated controls, whereas other progesterone-responsive transcripts did not differ between female rats exposed to vehicle or progesterone as neonates. The organizational actions of progesterone on the uterus were dependent on signaling through the progesterone receptor but not estrogen receptor 1. To summarize, neonatal progesterone exposure leads to disturbances in endometrial gland biogenesis, progesterone resistance, and uterine dysfunction. Neonatal progesterone effectively programs adult uterine responsiveness to progesterone.

Progesterone possesses a crucial role in female reproduction with regulatory actions throughout the female reproductive axis (1–3). The hypothalamus, pituitary, ovary, and uterus are all targets for progesterone. Progesterone modulates gonadotropin secretion, activates sexual behavior, triggers ovarian events leading to ovulation, acts to stimulate the growth and differentiation of the uterus, and inhibits uterine contractility (3–6). Perturbations in progesterone signaling, especially those leading to uterine progesterone resistance, are at the core of a range of uterine diseases (7–12). Endometriosis, early pregnancy loss, leiomyoma, and endometrial cancer have all been linked to disruptions in progesterone action. The rat has surfaced as an effective animal model for investigating uterine progesterone resistance (13).

Progesterone also possesses critical organizational actions on the development of the uterus (14, 15). Neonatal progesterone exposure can affect the structure and function of the uterus in the mouse and sheep (16–20). The programming effects of progesterone are influenced by the timing of hormone exposure, duration of treatment, and genetic background (18, 21, 22). Endometrial gland formation can be interrupted and fertility negatively affected after neonatal progesterone treatment. These organizational actions of progesterone affect the development of the target cells that progesterone will act on in the adult uterus and thus could potentially affect adult uterine responsiveness to progesterone (15). Consistent with such a hypothesis, early exposure to other compounds, including endocrine disruptors, has been linked to uterine progesterone resistance and uterine disease (14, 23, 24).

In this report, we investigated the relationship between the organizational actions of progesterone and the development of uterine progesterone resistance. We show that neonatal progesterone exposure in the rat disrupts the structural development of the uterus and its adult function, including its responsiveness to progesterone and susceptibility to dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Holtzman Sprague-Dawley (HSD) and Brown Norway (BN) rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories and Charles River, respectively. Animals were housed in an environmentally controlled facility with lights on from 6:00 am to 8:00 pm hours and allowed free access to food and water. The food consisted of a standard rodent diet (8604; Nestle Purina). The University of Kansas Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee approved the procedures for rodent handling and experimentation described in this report.

Experimental design

Adult HSD female rats (aged >8 weeks old of age) were housed with adult HSD males (>3 months of age). The presence of sperm in the vaginal lavage was considered gestation day 0.5. Beginning on gestation day 20.5, animals were inspected each morning and evening for parturition. The day of birth was considered as postnatal day (PND) 0 and the number of female pups per dam was adjusted to 6. Developmental profiles of serum progesterone and progesterone receptor (PGR) transcript levels were constructed from trunk blood, and uteri were harvested at PND 0, 3, 5, 9, 15, 20, and 30, respectively. In other experiments, pups received daily subcutaneous injections of sesame oil (vehicle control) or progesterone (P0130, 40 μg/g body weight; Sigma-Aldrich) from PND 3 to 9. The effective progesterone concentration was determined empirically and is similar to the dose yielding a uterine phenotype in neonatally treated mice (18, 20). The impact of neonatal progesterone treatment on the female reproductive phenotype was monitored at various postnatal stages (see below). Some experiments were also performed in the BN rat. The involvement of estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and PGR signaling on the uterine phenotype activated by neonatal progesterone was investigated using rats possessing homozygous Esr1 (25) or Pgr (Pgr Δ136) (26) null mutations. Esr1 and Pgr mutant rats are available at the Rat Resource & Research Center (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO; www.rrrc.us.)

Serum progesterone measurements

Serum concentrations of progesterone were measured by RIA as described previously (27).

Histology and immunocytochemistry

Uterine tissues were fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (6 μm) were prepared, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in a graded alcohol series. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or alternatively used for the immunolocalization of specific proteins. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling tissue sections in 10× Reveal Decloaker solution (RV1000N; Biocare Medical). Primary antibodies to FOXA2 (WRAB-1200, 1:2000 dilution; Seven Hills Bioreagents), CALCA (ab47027, 1:400 dilution; Abcam), BHLHA15 (sc-98771, 1:300 dilution; Santa Cruz), IGF1 (ab40657, 1:1000 dilution; Abcam), and pan-cytokeratin (F3418, 1:400 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich) were used in the analyses (Table 1). Nonspecific immunoglobulin binding sites were blocked with 10% normal goat serum. Sections (6 μm) were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Subsequently, sections were incubated for 30 minutes each with biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin (Vectastain ABC kit, PK-4001; Vector Laboratories) or with biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (B9904, 1:200 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich). Antigen-antibody complexes were identified (AEC substrate kit, SK-4200; Vector Laboratories), sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, and slides were mounted with Mount-Quick aqueous mounting medium (Daido Sangyo). CALCA, BHLHA15, and IGF1 antigen-antibody complexes were detected using Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (A11011, 1:500 dilution; Life Technologies), and sections were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (D1306, 1:50 000 dilution; Invitrogen). Staining was examined by light and immunofluorescence microscopy (Leica).

Table 1.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer and catalog no. | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOXA2 | Recombinant rat FOXA 2 (amino acids 7–86) | Anti-FOXA2 | Seven Hills Bioreagent; WRAB-1200 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:2000 |

| CALCA | Synthetic peptide-rat CGRP (aa1–100) | Anti-CGRP | Abcam; ab47027 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:400 |

| BHLHA15 | Human MIST1 (aa63–102) | Anti-MIST-1 | Santa Cruz; sc-98771 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:300 |

| IGF1 | Synthetic human IGF1 (aa60–70) | Anti-IGF1 | Abcam; ab40657 | Rabbit; polyclonal | 1:1000 |

| pan-Cytokeratin | Human keratin enriched preparation | Anti-cytokeratin | Sigma Aldrich; F3418 | Mouse; Monoclonal | 1:400 |

Puberty, cyclicity, and fertility

Vaginal opening was used as a measure of puberty and monitored in neonatal oil- or progesterone-treated females beginning from PND 30. At PND 30, some females were tested for responsiveness to exogenous gonadotropins. Females were treated intraperitoneally with 30 IU of equine chorionic gonadotropin at 3:00 pm, and 48 hours later, 30 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) was injected. Twenty-two hours after the hCG injection, animals were killed, oocytes were recovered from the oviduct, cumulus cells were removed using hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich), and oocytes were counted. Estrous cycles were assessed by daily examination of vaginal cytology in the morning (8:00–10:00 am) from puberty (vaginal opening) until 10 weeks of age. Females were subsequently housed with fertile males for 1 month, and pregnancies were monitored throughout the cohabitation and for an additional month after separation from males.

Uterine responses to steroid hormones

Adult uterine responsiveness to steroid hormones was assessed by examining artificial decidual reactions in females treated with estradiol and progesterone and by monitoring acute uterine gene expression responses to administered progesterone. In both the experiments, neonatal oil and progesterone-treated females were ovariectomized at 8 weeks of age and rested for 2 weeks before experimentation.

Artificial decidualization

Ovariectomized females were treated with an empirically determined hormone regimen known to appropriately prepare the uterus for embryo implantation (13). Decidualization was induced via scratching the antimesometrial endometrial surface of 1 uterine horn. Uteri were collected on the fourth day after the decidualization stimulus, weighed, and snap frozen in dry ice–cooled heptane. Frozen sections were prepared, and the extent of decidualization was visualized by alkaline phosphatase histochemical staining using nitroblue tetrazolium–bromochloroindoyl phosphate (13).

Acute responses to progesterone

Ovariectomized females were subcutaneously injected with sesame oil (vehicle control) or progesterone (40 μg/g body weight). Uteri were collected 9 hours after the injection and processed for RNA isolation or histology.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

Transcriptomic profiles were determined by deep sequencing of uterine specimens from ovariectomized HSD and BN rats acutely treated with progesterone (see above). Complementary DNA libraries from total RNA samples were prepared with Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation kits (Illumina); 500 ng of total RNA was used as input. Poly(A)-containing RNAs were purified with oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads. RNA fragmentation, first- and second-strand cDNA synthesis, end repair, adaptor ligation, and PCR amplification were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The cDNA libraries were checked for fragment size distribution using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc) before sequencing.

Barcoaded cDNA libraries were multiplexed and sequenced by HiSeq2000 (100-bp paired-end reads) using a TruSeq 200-cycle SBS kit (Illumina) at the University of Kansas Medical Center Genome Sequencing Facility. After generation of sequencing images, the pixel-level raw data collection, image analysis, and base calling were performed by real-time analysis software (Illumina). The base call files (*.bcl) were converted to *.qseq files by Illumina's BCL Converter, and the *.qseq files were subsequently converted to *.fastq files for downstream analysis. Reads from *.fastq files were mapped to the rat reference genome (Ensembl Rnor_5.0.78) using Genomics Workbench 8.0 (CLC Bio). The mRNA abundance was expressed in reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped. Statistical significance was calculated by empirical analysis of digital gene expression in the Bio Genomics Workbench. A corrected false discovery rate of 0.05 was used as a cutoff for significant differential expression (control vs progesterone-treated). Functional patterns of transcript expression were further analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

cDNAs were synthesized with total RNA (1 μg) from each sample using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), diluted 10 times with water, and subjected to qRT-PCR to quantify mRNA levels. Primers were designed using Primer3 (28). Primer sequences are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Real-time PCR amplification of cDNAs was carried out in a reaction mixture (20 μl) containing SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and primers (250 nM each). Amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using the ABI Prism 7500 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions included an initial hold step (95°C for 10 minutes) and 40 cycles of a 2-step PCR (92°C for 15 seconds and then 60°C for 1 minute), followed by a dissociation step (95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 15 seconds and then a sequential increase to 95°C). The comparative cycle threshold method was used for relative quantification of the amount of mRNA for each sample normalized to 18S RNA.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons between 2 means were performed with the Student t test. Comparisons between more than 2 groups were made using ANOVA, and multiple comparisons were performed using the Tukey post hoc test.

Results

Experiments were performed to examine the organizational actions of progesterone on uterine development and adult uterine function in the rat.

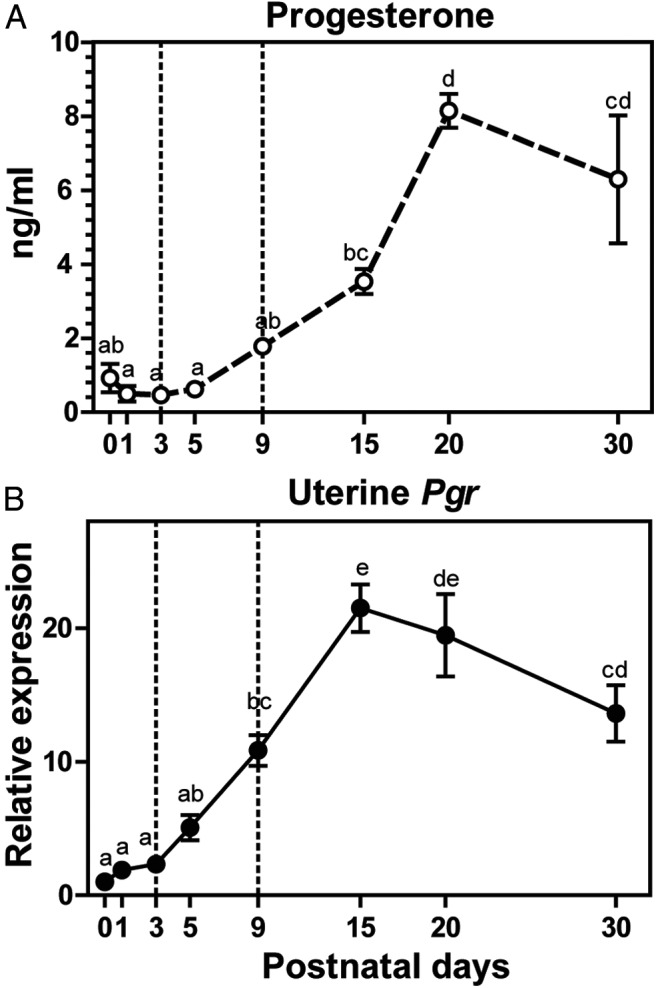

Postnatal circulating progesterone and uterine Pgr mRNA expression increases with age

To establish a foundation for experiments on the organizational actions of progesterone, we first examined circulating progesterone and uterine Pgr transcript concentrations during the neonatal period in untreated rats. Serum progesterone concentrations and uterine Pgr transcript levels at PND 0 (day of birth), 1, 3, 5, 9, 15, 20, and 30 are shown in Figure 1. Serum progesterone concentrations were low until PND 5 and then increased thereafter, reaching maximal levels at PND 20 (Figure 1A). The expression of Pgr mRNA was detectable from the day of birth and progressively increased until PND 15 (Figure 1B). These 2 components of the progesterone signaling system exhibit parallel profiles from birth to puberty.

Figure 1.

Postnatal circulating progesterone and uterine progesterone receptor (Pgr) mRNA expression increases with age. Serum progesterone concentrations (A) and uterine Pgr transcript levels (B) in female pups at specific stages of postnatal life were assessed. Results are expressed as means ± SEM (A, n = 6; B, n = 3). Letters above each mean value that are different reflect significant differences among postnatal days (P < .05).

Neonatal progesterone exposure and reproductive tract development

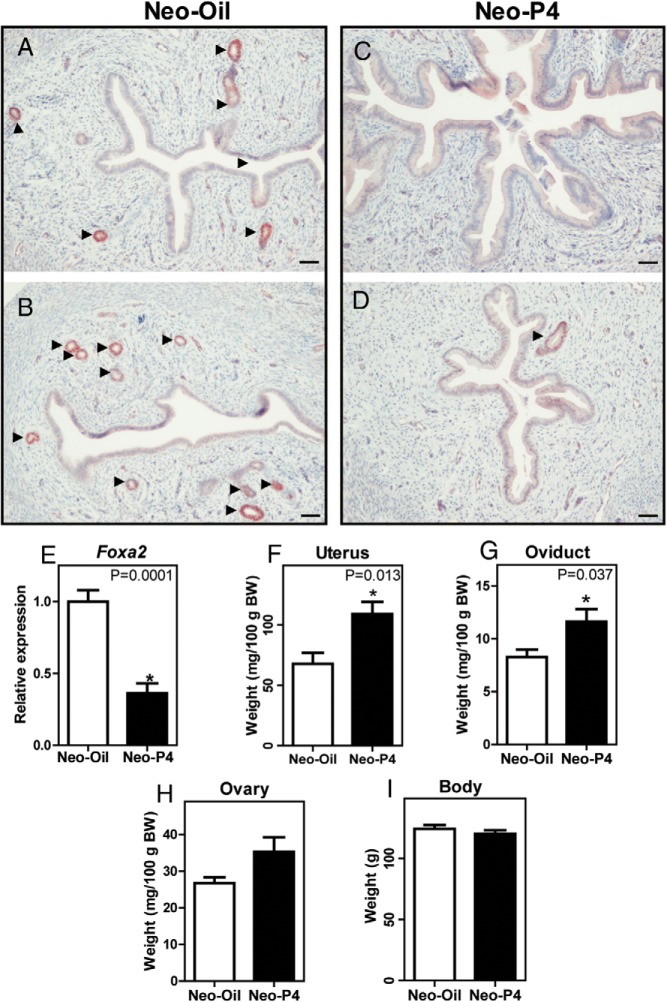

Progesterone was administered from PND 3 to 9, a time when endogenous circulating progesterone concentrations are low (Figure 1A, denoted by the interval between the dotted lines). FOXA2 was used to identify nuclei of uterine glandular epithelium, as demonstrated previously in the mouse and rat (29, 30). When observed at PND 30, neonatal progesterone treatment severely limited or completely ablated uterine gland development (Figure 2, A–D). Foxa2 transcript levels were significantly decreased in uteri from neonatal progesterone-treated females (Figure 2E), supporting the immunohistochemical observations. Overall, uteri of the neonatally progesterone-treated rats were larger (Figure 2F) and in some cases fluid filled with pronounced luminal epithelium (Figure 2C). Oviductal weights were also significantly larger in neonatal progesterone-treated rats (Figure 2G). However, ovarian and whole-body weights did not exhibit significant differences between the control and neonatal progesterone-treated groups at PND 30 (Figure 2, H and I).

Figure 2.

Neonatal progesterone exposure and reproductive tract development. FOXA2 immunohistochemical analyses of PND 30 uteri from neonatal oil-treated (Neo-Oil; 2 examples shown are shown [A and B]) and progesterone-treated (Neo-P4; 2 examples and shown [C and D]) pups are shown. Arrowheads indicate the locations of uterine glands. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. Neo-P4 treatment completely (C) or partially (D) ablated uterine glands. Uterine Foxa2 transcript levels of Neo-Oil– and Neo-P4–treated rats are shown in panel E. Uterus (F), oviduct (G), ovary (H), and whole-body (I) weights of Neo-Oil– and Neo-P4–treated rats at PND 30 are presented. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6). Asterisks and corresponding P values indicate significant differences between means. BW, body weight.

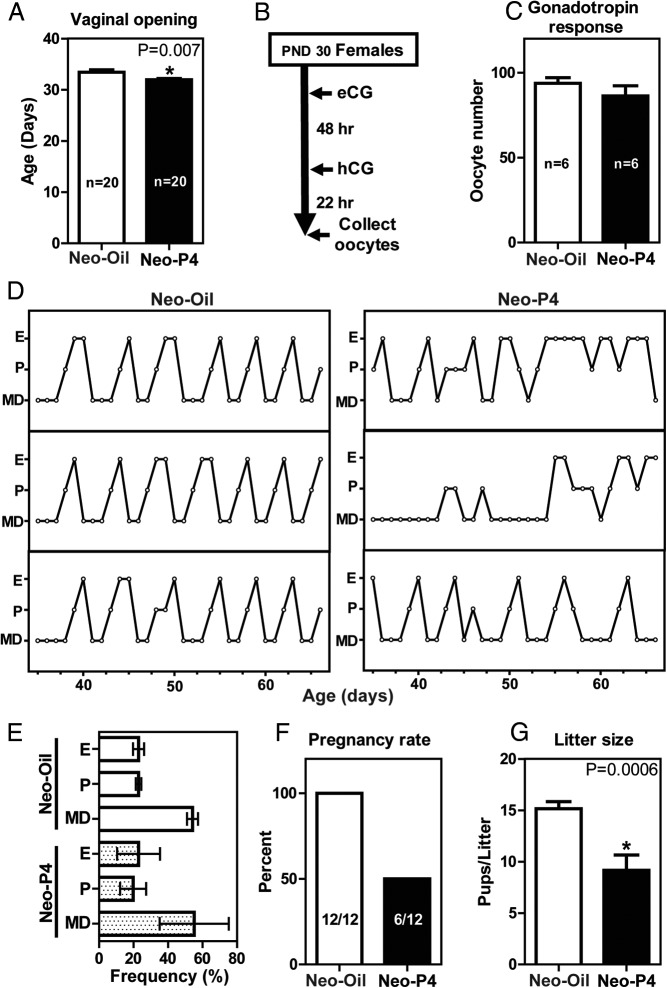

Neonatal progesterone exposure affects puberty, cyclicity, and fertility

Vaginal opening was used operationally as a measure of puberty. Neonatal progesterone treatment shortened the time to vaginal opening (Figure 3A). Gonadotropin-stimulated oocyte yields were similar in neonatal progesterone- and vehicle-treated control prepubertal rats (Figure 3, B and C). Neonatal progesterone treatment affected cyclicity. These females showed irregular estrous cycles (Figure 3D). Representative vaginal cytology patterns over a 4-week interval are shown (Figure 3D). The extent of irregularities in the cyclicity are represented by the SE bars in Figure 3E. Adult fertility was also negatively affected in the neonatal progesterone-treated female rats. Cohabiting neonatal vehicle control females with fertile males yielded 100% pregnancies (12 of 12), whereas only 50% of the neonatal progesterone-treated females housed with fertile males became pregnant (6 of 12) (Figure 3F). The litter sizes of successful pregnancies were also negatively affected by neonatal exposure to progesterone (Figure 3G). Placentation sites did not exhibit significant differences in their organization or distribution of invasive trophoblast cells within the uterine mesometrial compartment (Supplemental Figure 1). Thus, neonatal exposure to progesterone significantly affects the timing of puberty and perturbs cyclicity, fertility, and fecundity but does not affect organization of the placenta.

Figure 3.

Neonatal progesterone exposure affects puberty, cyclicity, and fertility. Female rats were treated neonatally with oil (Neo-Oil) or progesterone (Neo-P4). Neo-P4 exposure hastened the age at vaginal opening (A). Gonadotropin-induced ovulatory responsiveness was assessed in 30-day-old Neo-Oil and Neo-P4 female rats treated with equine gonadotropin (eCG) and hCG (B and C). D, Representative estrous cycle profiles of Neo-Oil– and Neo-P4–treated females monitored from 35 to 66 days of age. Metestrous-diestrous (MD), proestrous (P) and estrous (E) stages were assessed by inspection of vaginal cytology and are summarized in panel E. F and G, Pregnancy rates and litter sizes were assessed in adult Neo-Oil and Neo-P4 females housed with fertile males. Values are means ± SEM.

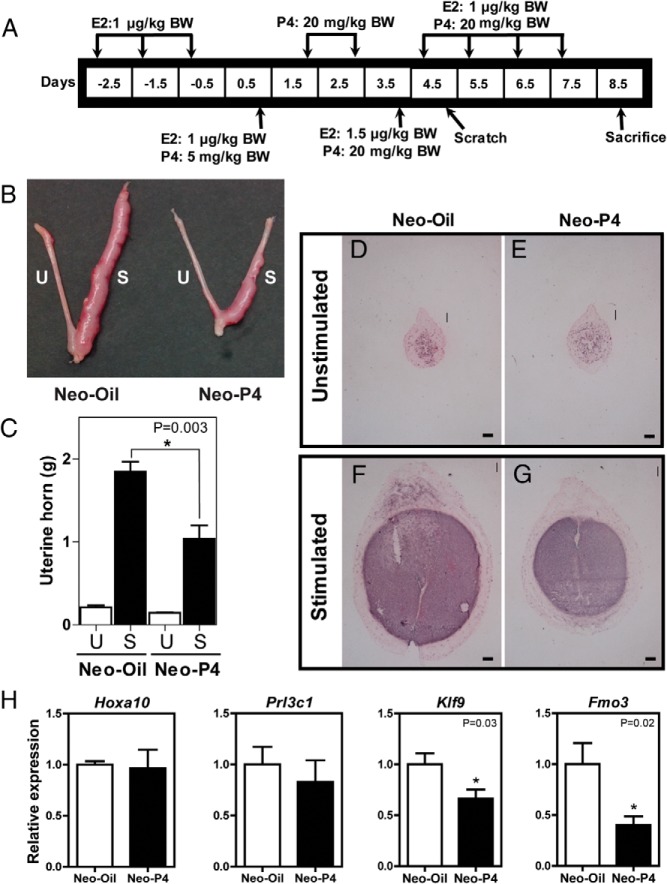

Neonatal progesterone exposure affects decidualization

To further explore the mechanisms underlying subfertility in the neonatal progesterone-treated rat, we investigated decidualization, a progesterone-dependent event, which is indispensable for the establishment of pregnancy. The capacity of uteri from adult rats treated neonatally with vehicle or progesterone to decidualize was analyzed. Uteri from neonatal vehicle-treated animals displayed robust decidual responses, whereas uteri from neonatal progesterone-treated rats were less responsive to the deciduogenic stimulus (Figure 4, B and C). These differences were apparent on uterine cross sections for which the total area of decidual tissue, identified with alkaline phosphatase staining, was less in neonatal progesterone-treated vs vehicle control females (Figure 4, D-G). Although the expression of several transcripts associated with decidualization (Hoxa10, Prl3c1, Prl8a2, Pgr, Prl, Igfbp1, Bmp2, Dkk1, and Wnt4) were not significantly different in control vs neonatal progesterone-treated rats, Fmo3, a transcript repressed in deciduoma of the progesterone-resistant BN rat (13) and Klf9, a transcriptional regulator implicated in progesterone-directed decidualization (31) were both repressed in deciduoma from the neonatal progesterone-treated HSD rat (Figure 4H and Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4.

Neonatal progesterone exposure affects decidualization. A, Experimental paradigm for inducing decidualization. Neonatal vehicle (Neo-Oil)-treated and progesterone (Neo-P4)-treated females were ovariectomized as adults and treated with an empirically determined hormone regimen of P4 and estradiol (E2). B, mesometrial surface of the endometrium of one of the uterine horns was scratched to induce the decidualization response. The gross morphology of the unstimulated (U) and stimulated (S) uterine horns of Neo-Oil– and Neo-P4–treated animals is presented. C, Weights of unstimulated and stimulated uterine horns are shown. D–G, representative cross sections of day 8.5 unstimulated and stimulated uterine horns. The extent of decidualization was visualized by alkaline phosphatase histochemical staining using nitro blue tetrazolium–bromochloroindoyl phosphate. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. H, Indices of decidualization were monitored by qRT-PCR for Hoxa10, Prl3c1, Klf9, and Fmo3. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6/group). Asterisks and corresponding P values indicate significant differences between means. BW, body weight.

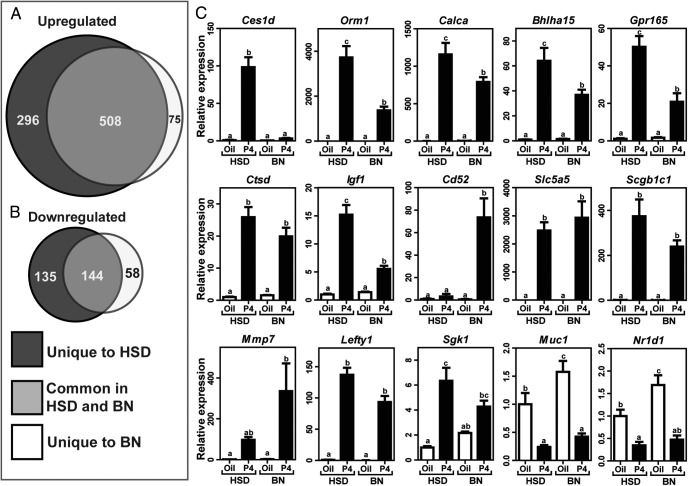

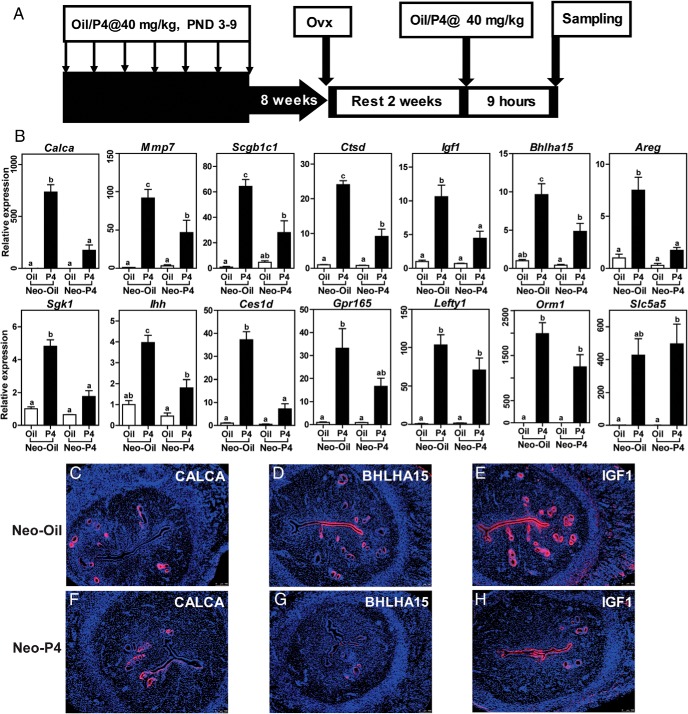

Progesterone-dependent uterine transcriptome: impact of progesterone resistance

The attenuated decidual response associated with neonatal progesterone exposure closely resembled the uterine progesterone resistance phenotype of the BN rat (13). The purpose of the next experiment was 2-fold: (1) to identify uterine progesterone-responsive transcripts and (2) to determine how progesterone resistance affects the uterine progesterone-responsive transcriptome. RNA-seq analysis was performed on uteri of ovariectomized HSD and BN rats acutely treated with progesterone. A robust set of selected genes that were altered due to progesterone in HSD and BN uteri is shown in Table 2. RNA-seq data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession No. GSE68542). A total of 804 and 583 known transcripts were up-regulated by progesterone in HSD and BN uteri, respectively. Of the up-regulated transcripts, 508 were common progesterone targets between the strains (Figure 5A). A total of 279 and 202 known transcripts were down-regulated by progesterone in HSD and BN uteri, respectively. Of the down-regulated transcripts, 144 were common progesterone targets between the strains (Figure 5B). Canonical pathways modulated by progesterone exhibited some differences in HSD vs BN uteri. Unique pathways included nerve growth factor, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/AKT, phospholipase C, and p53 signaling (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). qRT-PCR was used to validate expression of 35 selected transcripts (Table 1, Figure 5C, and Supplemental Figure 3). Among the shared progesterone-responsive transcripts some exhibited similar responses between HSD and BN strains (eg, Slc5a5, Scgb1c1, Mmp7, Lefty1, Sgk1, Muc1, and Nr1d1), whereas for others, BN uteri showed diminished responses to progesterone (eg, Ces1d, Orm1, Calca, Bhlha15, Gpr165, Ctsd, Igf1, and Cd52) (Figure 5C). Complete lists of common and unique progesterone-responsive transcripts in HSD and BN rats are provided in Supplemental Table 4. Progesterone-responsive transcripts identified in the HSD rat but not in the BN rat could represent candidates for a uterine progesterone resistance transcript signature. Four unique features of uterine progesterone responsiveness were identified in progesterone-resistant (BN) rats: (1) restricted spectrum and total number of progesterone-responsive transcripts; (2) attenuated progesterone responses associated with a subset of progesterone-responsive transcripts; (3) a unique set of progesterone-responsive transcripts; and (4) a unique profile of progesterone-responsive canonical pathways.

Table 2.

Selected Uterine Transcripts Identified by RNA-Seq in Progesterone-Treated HSD and BN Rats

| Gene Symbol | Gene Description | Chromosome | Fold Change (P4/Oil) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSD | BN | |||

| Orm1 | Orosomucoid 1 | 5 | 1259.9 | 539.4 |

| Slc5a5 | Solute carrier family 5, member 5 | 16 | 855.9 | 571.3 |

| Calca | Calcitonin related polypeptide, α | 1 | 556.7 | 246.7 |

| Scgb1c1 | Secretoglobin, family 1C, member 1 | 1 | 70.5 | 46.1 |

| Lefty1 | Left right determination factor 1 | 13 | 61.3 | 207.9 |

| Gpr165 | G protein-coupled receptor 165 | X | 32.6 | 25.1 |

| Serpina11 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A, member 11 | 6 | 28.2 | 30.9 |

| Bhlha15 | Basic helix-loop-helix family, member A15 | 12 | 27.7 | 13.3 |

| Mmp7 | Matrix metallopeptidase 7 | 8 | 26.3 | 20.3 |

| Ces1d | Carboxylesterase 1D | 19 | 20.5 | 4.5 |

| Ctsd | Cathepsin D | 1 | 10.5 | 6.6 |

| Cd52 | CD52 molecule | 5 | 9.8 | 81.7 |

| Igf1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 | 7 | 6.6 | 5.8 |

| Osgin1 | Oxidative stress-induced growth inhibitor 1 | 19 | 4.7 | 3.9 |

| Areg | Amphiregulin | 14 | 4.1 | −1.1 |

| Ascl3 | Achaete-scute family bHLH transcription factor 3 | 1 | 3.9 | 2.1 |

| Fam111a | Family with sequence similarity 111, member A | 1 | 3.9 | 1.1 |

| Rnf185 | Ring finger protein 185 | 14 | 3.7 | 1.9 |

| Plekhs1 | Pleckstrin homology domain containing, family S member 1 | 1 | 3.6 | 1.9 |

| Sgk1 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 | 1 | 3.4 | 1.9 |

| Taf13 | TAF 13 RNA polymerase II, TATA box binding protein (TBP)-associated factor | 2 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| Npy4r | Neuropeptide Y receptor Y4 | 16 | 2.9 | 0.9 |

| Nupr1 | Nuclear protein, transcriptional regulator, 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 1.2 |

| RT1-A2 | RT1 class Ia, locus A2 | 20 | 2.2 | −1.6 |

| Col12a1 | Collagen, type XII, alpha1 | 8 | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Cd248 | CD248 molecule | 1 | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| Ihh | Indian hedgehog | 9 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| Wdr86 | WD repeat domain 86 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.1 |

| Arid5a | AT rich interactive domain 5A | 9 | −1.3 | −2.4 |

| Il17re | Interleukin 17 receptor E | 4 | −1.4 | 2.3 |

| Mx2 | Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 2 | 11 | −1.6 | −3.1 |

| Pnoc | Prepronociception | 15 | −2.3 | −2.3 |

| Nr1d1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 1 | 10 | −6.4 | −4.9 |

| Muc1 | Mucin 1 | 2 | −12.1 | −3.5 |

| Col17a1 | Collagen, type XVII, α 1 | 1 | −15.1 | −8.2 |

Figure 5.

Progesterone-dependent uterine transcriptome: impact of progesterone resistance. Adult HSD (control) and BN (progesterone [P4] resistance model) rats were ovariectomized, rested 2 weeks, and treated with progesterone; uteri were harvested 9 hours posttreatment and subjected to RNA-seq analysis. Venn diagrams of progesterone up-regulated (A) and down-regulated (B) genes derived from RNA-seq analysis show overlapping and unique genes. C, Validation of representative genes by qRT-PCR. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6/group). Letters above each mean value that are different reflect significant differences among the relevant groups (P < .05).

We also evaluated the responsiveness of the BN rat to neonatal progesterone exposure. BN rats were treated neonatally (PND 3–9) with oil or progesterone. Neonatal progesterone exposure effectively disrupted adenogenesis in the BN rat (Supplemental Figure 4). Thus, uterine progesterone resistance exhibited by the BN rat develops after PND 9 or alternatively targets substrates independent of pathways affecting uterine adenogenesis.

Neonatal progesterone and adult uterine progesterone responsiveness

Given insight into components of the uterine transcriptome affected by progesterone resistance, we next investigated uterine progesterone responsiveness in control and neonatal progesterone-treated female rats. Acute uterine responses to exogenous progesterone were examined in adult ovariectomized rats previously treated neonatally with vehicle or progesterone. Known uterine progesterone-responsive transcripts were measured by qRT-PCR. Some uterine progesterone-responsive transcripts (Calca, Mmp7, Scgb1c1, Ctsd, Igf1, Bhlha15, Areg, Sgk1, Ihh, Ces1d, and Gpr165) showed a blunted activation in neonatal progesterone-treated vs vehicle -treated control rats, whereas other progesterone-responsive transcripts (Lefty1, Orm1, and Slc5a5) were unaffected by neonatal progesterone exposure (Figure 6B). Several of the transcripts exhibiting an attenuated response in neonatal progesterone-treated rats showed similar attenuated responses in the BN rat, suggesting that they could be part of a uterine progesterone resistance transcript signature. Distribution patterns of CALCA, BHLHA15, and IGF1 proteins within the rat uterus were dramatically affected by neonatal progesterone exposure (Figure 6, C–H).

Figure 6.

Neonatal progesterone and adult uterine progesterone responsiveness. A, Paradigm for assessing adult uterine responsiveness to progesterone (P4) in neonatal vehicle-treated (Neo-Oil) and progesterone-treated (Neo-P4) rats. B, qRT-PCR assessment of differentially expressed P4-responsive genes in adult uteri from Neo-Oil and Neo-P4 female rats. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6/group). Letters above each mean value possessing a different identity reflect significant differences among the relevant groups (P < .05). C–H, Immunolocalization for CALCA, BHLHA15, and IGF1 proteins in uteri from adult ovariectomized Neo-Oil (C–E) and Neo-P4 (F–H) female rats acutely treated with P4. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm.

Adult uteri from HSD females neonatally treated with progesterone displayed fewer uterine glands and expressed less Foxa2 than did vehicle-treated controls (Supplemental Figure 5). Although neonatal progesterone attenuated adenogenesis, uterine glands at 10 weeks were more abundant than those present at PND 30 (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that early progesterone exposure delayed and decreased but did not entirely prevent adenogenesis.

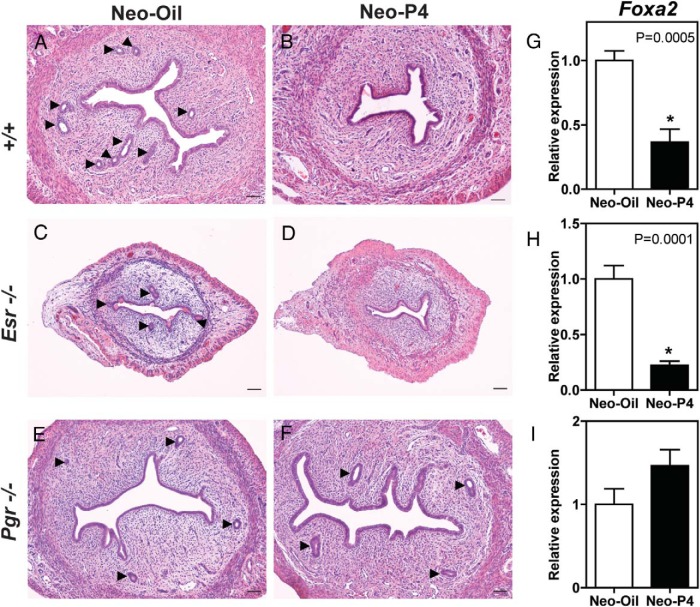

Signaling pathways mediating neonatal progesterone action

Progesterone acts on many of its cellular targets through interactions with a ligand-activated transcription factor referred to as the PGR (1, 3, 32). In this experiment, we used mutant rat models with null mutations at the Esr1 (25) or Pgr (26) locus to investigate signaling pathways activated by neonatal progesterone treatment. Wild-type and mutant rats were neonatally treated with vehicle or progesterone, and their uteri were examined for endometrial gland development on PND 30. Neonatal progesterone dramatically decreased uterine glands in wild-type and Esr1-null uteri (Figure 7, A–D). In contrast, neonatal progesterone was ineffective in the Pgr-null rats (Figure 7, E and F). Quantification of uterine Foxa2 mRNA paralleled uterine gland numbers (Figure 7, G–I). Collectively, the data indicate that the effects of neonatal progesterone on uterine glands are mediated by the PGR and independent of the ESR1 signaling pathway.

Figure 7.

Signaling pathways mediating neonatal progesterone action. The actions of neonatal vehicle (Neo-Oil) vs neonatal progesterone (Neo-P4) were investigated in wild type (+/+), ESR1-null (Esr1 −/−), and PGR-null (Pgr −/−) female rats. A–I, Uterine morphology (A–F; hematoxylin and eosin staining) and Foxa2 transcript levels (G–I) were assessed at PND30. Scale bar corresponds to 100 μm. Values are means ± SEM (n = 6/group). Asterisks and corresponding P values indicate significant differences between means.

Discussion

Progesterone exhibits a range of actions on the female reproductive tract. These include activational effects on the adult uterus, which support the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy, and organizational effects on development of the uterus.

Neonatal exposure to exogenous progesterone disrupts the normal progression of female reproductive tract development in the mouse, sheep, and rat (16–20; present study). Details of the responses vary among these species and at least within the mouse among different strains. Direct comparisons across species are difficult because of differences in experimental design. In the rat, we observed that neonatal progesterone treatment (40 μg/g body weight daily on PND 3–9) leads to a delay in uterine gland development, a deficit of uterine glands in adult female rats, and a subfertility phenotype. The effects of neonatal progesterone treatment were more pronounced in previous experimentation with sheep and the C57BL/6 mouse, resulting in infertility (16–20). Adjustments in the concentration, timing, and/or duration of neonatal progesterone treatment in the rat may yield more disruptive effects on uterine development and function akin to those reported in the mouse and sheep. Consistent with this suggestion, Sananès et al. (33) showed that a much higher progesterone dose delivered to the Sprague-Dawley rat during a narrow developmental window (3 mg/daily on PND 7–9) yielded severe adult uterine dysfunction.

Mice and sheep receiving neonatal progesterone treatment have been described as uterine gland knockout models and thus a tool for investigating the role of uterine glands in female reproductive tract function (19, 34–36). In the rat, we observed more diverse effects of neonatal progesterone on female reproductive physiology. Puberty was accelerated and estrous cycle aberrations were noted in neonatal progesterone-treated rats. These biological responses indicate effects on neuroendocrine targets. Consistent with these observations, earlier reports have demonstrated that neonatal progesterone treatment affects neuroendocrine development (37–39). Although uterine glands represent an overt and easily recognizable target of neonatal progesterone treatment, we observed a broader range of phenotypic responses within the uterus. Whether these diverse uterine effects are dependent on or independent of the actions of neonatal progesterone on uterine gland biogenesis remains to be determined.

The adult female HSD rat exposed to exogenous progesterone treatment as a neonate exhibits some phenotypic similarities with the adult BN rat. Both rat models exhibit increased embryo implantation failure, attenuated decidualization, uterine progesterone resistance, and subfertility (13, 40, 41; present study). Furthermore the 2 models share some of the same progesterone-dependent transcriptomic features. However, while the BN rat has a profound disruption in placentation, including impaired trophoblast invasion (40, 41), the neonatal progesterone-treated HSD rat did not exhibit discernible effects on placentation (present study).

Adult uterine progesterone resistance was evident in the neonatal progesterone-treated rat. Progesterone-dependent responses, such as decidualization, were dramatically reduced; however, other biological events dependent on progesterone signaling, such as ovulation, were not affected by the organizing actions of progesterone, suggesting tissue-specific progesterone resistance. Furthermore, within the uterus, progesterone-dependent gene expression responses were not homogeneous. Neonatal progesterone treatment affected adult uterine progesterone responsiveness for some progesterone target genes but not others. Several potential explanations for the heterogeneous responses can be proposed. Progesterone actions are mediated by the PGR, which can exist in multiple isoforms resulting from alternative promoter usage, yielding A and B isoforms, and a range of post-translational modifications (1, 3, 32). Mouse mutagenesis experiments have linked the A isoform of PGR to progesterone actions in both the uterus and ovary (42) and thus the occurrence of differential activities of PGR-A vs PGR-B isoforms does not offer a simple explanation for the uterine-specific progesterone resistance observed in the neonatal progesterone-treated rat. The biological meaning of the wide assortment of PGR posttranslational modifications in the context of uterine biology is less understood but probably contributes to intracellular trafficking, protein-protein interactions, and ultimately transcriptional activity (8, 33, 43). Steroid receptor coactivator-2, a known PGR coactivator, is required for progesterone-dependent decidualization (44) yet only contributes to the regulation of a small subset of PGR target genes (45), offering an example of how subsets of uterine progesterone target genes can be differentially regulated in specific physiological or pathological states. Thus, a reasonable hypothesis for the selective uterine progesterone resistance phenotype observed in the neonatal progesterone-treated rat would include an impact on the assembly of a subset of PGR-driven transcriptional complexes.

The progesterone signaling system undergoes maturation steps during postnatal development characterized by increases in ligand production and uterine receptor expression. Temporally these changes in progesterone production and PGR expression coincide with the critical period for programming adult uterine responses to exogenous progesterone treatment. Such a temporal coincidence suggests that endogenous progesterone signaling may possess a programming role in uterine development. However, differentiation of core uterine structural components does not require progesterone signaling. Neonatal removal of the sources of progesterone (ovaries and adrenal glands) does not impair uterine differentiation, including adenogenesis (46). Thus, the potential roles for the postnatal endogenous progesterone signaling system must involve more subtle developmental processes, which could include establishing the set point for adult uterine responsiveness to progesterone. A prevalent theory is that the endogenous postnatal progesterone signaling system exists as protection from the potential harmful effects of androgens or estrogens on the organization of the female reproductive axis (47). Progesterone is known to antagonize the masculinizing actions of androgens and estrogens on female reproductive axis development (37, 48, 49).

Both estrogen and progesterone signaling have been implicated in postnatal development of the female reproductive tract (15). Uterine actions of these 2 steroid hormones are mediated principally by signaling through ESR1 and PGR, respectively (50, 51). Experimental evidence indicates that ESR1 and PGR are not required for organization of the basic uterine architecture, including the process of adenogenesis (25, 52–56). Furthermore, the neonatal actions of progesterone are independent of ESR1 but are absolutely dependent upon signaling through the PGR (56, 57; present study). DeMayo and colleagues (55) have further shown that the neonatal actions of progesterone on uterine adenogenesis are dependent on uterine epithelial expression of PGR and Indian hedgehog signaling in the mouse (55). Additional candidate downstream effectors of PGR signaling have been identified using transcriptome profiling (20). The actual epigenetic mechanisms underlying the uterine programming actions of neonatal progesterone exposure are yet to be elucidated.

In conclusion, the organizational actions of progesterone effectively program adult uterine responses to progesterone and represent a potential link to the etiology of uterine progesterone resistance and uterine dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Wei Cui for assistance with the initial assessment of ovarian responses to gonadotropins. We acknowledge Regan Scott for performing immunohistochemical analysis of placental tissues. We also thank Stacy McClure, Lesley Shriver, and Martin Graham for administrative assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants HD066406, OD01478, and HD020676). P.D. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Lalor Foundation. K.K. was supported by American Heart Association and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science postdoctoral fellowships.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BN

- Brown Norway

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor 1

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- HSD

- Holtzman Sprague-Dawley

- PGR

- progesterone receptor

- PND

- postnatal day

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- RNA-seq

- RNA sequencing.

References

- 1. Conneely OM, Mulac-Jericevic B, DeMayo F, et al. Reproductive functions of progesterone receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 2002;57:339–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spencer TE, Bazer FW. Biology of progesterone action during pregnancy recognition and maintenance of pregnancy. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1879–d1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wetendorf M, DeMayo FJ. Progesterone receptor signaling in the initiation of pregnancy and preservation of a healthy uterus. Int J Dev Biol. 2014;58:95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Levine JE, Chappell PE, Schneider JS, et al. Progesterone receptors as neuroendocrine integrators. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2001;22:69–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robker RL, Akison LK, Russell DL. Control of oocyte release by progesterone receptor-regulated gene expression. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mani SK, Blaustein JD. Neural progestin receptors and female sexual behavior. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;96:152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chrousos GP, MacLusky NJ, Brandon DD, et al. Progesterone resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;196:317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aghajanova L, Velarde MC, Giudice LC. Altered gene expression profiling in endometrium: evidence for progesterone resistance. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cakmak H, Taylor HS. Molecular mechanisms of treatment resistance in endometriosis: the role of progesterone-Hox gene interactions. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang S, Thiel KW, Leslie KK. Progesterone: the ultimate endometrial tumor suppressor. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Al-Sabbagh M, Lam EW, Brosens JJ. Mechanisms of endometrial progesterone resistance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim JJ, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Progesterone action in endometrial cancer, endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and breast cancer. Endocr Rev. 2013;34:130–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konno T, Graham AR, Rempel LA, et al. Subfertility linked to combined luteal insufficiency and uterine progesterone resistance. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4537–4550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spencer TE, Dunlap KA, Filant J. Comparative developmental biology of the uterus: insights into mechanisms and developmental disruption. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;354:34–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cooke PS, Spencer TE, Bartol FF, et al. Uterine glands: development, function and experimental model systems. Mol Hum Reprod. 2013;19:547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartol FF, Wiley AA, Coleman DA, et al. Ovine uterine morphogenesis: effects of age and progestin administration and withdrawal on neonatal endometrial development and DNA synthesis. J Anim Sci. 1988;66:3000–3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bartol FF, Wiley AA, Floyd JG, et al. Uterine differentiation as a foundation for subsequent fertility. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1999;54:287–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cooke PS, Ekman GC, Kaur J, et al. Brief exposure to progesterone during a critical neonatal window prevents uterine gland formation in mice. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Filant J, Zhou H, Spencer TE. Progesterone inhibits uterine gland development in the neonatal mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filant J, Spencer TE. Endometrial glands are essential for blastocyst implantation and decidualization in the mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 2013;88:93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spencer TE, Gray CA. Sheep uterine gland knockout (UGKO) model. Methods Mol Med. 2006;121:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stewart CA, Fisher SJ, Wang Y, et al. Uterine gland formation in mice is a continuous process, requiring the ovary after puberty, but not after parturition. Biol Reprod. 2011;85:954–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crain DA, Janssen SJ, Edwards TM, et al. Female reproductive disorders: the roles of endocrine-disrupting compounds and developmental timing. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:911–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rumi MA, Dhakal P, Kubota K, et al. Generation of Esr1-knockout rats using zinc finger nuclease-mediated genome editing. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1991–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kubota K, Rumi MAK, Dhakal P, et al. Generation of progesterone receptor mutant rats using zinc finger nuclease-mediated genome editing. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for the Study of Reproduction; July 19–23 2014; Grand Rapids, Michigan Abstract 488. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Terranova PF, Garza F. Relationship between the preovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge and androstenedione synthesis of preantral follicles in the cyclic hamster: detection by in vitro responses to LH. Biol Reprod. 1983;29:630–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jeong JW, Kwak I, Lee KY, et al. Foxa2 is essential for mouse endometrial gland development and fertility. Biol Reprod. 2010;83:396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yamagami K, Yamauchi N, Kubota K, et al. Expression and regulation of Foxa2 in the rat uterus during early pregnancy. J Reprod Dev. 2014;60:468–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pabona JM, Simmen FA, Nikiforov MA, et al. Krüppel-like factor 9 and progesterone receptor coregulation of decidualizing endometrial stromal cells: implications for the pathogenesis of endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E376–E392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jacobsen BM, Horwitz KB. Progesterone receptors, their isoforms and progesterone regulated transcription. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;357:18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sananès N, Baulieu EE, Le Goascogne C. Treatment of neonatal rats with progesterone alters the capacity of the uterus to form deciduomata. J Reprod Fertil. 1980;58:271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spencer TE, Stagg AG, Joyce MM, et al. Discovery and characterization of endometrial epithelial messenger ribonucleic acids using the ovine uterine gland knockout model. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4070–4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allison Gray C, Bartol FF, Taylor KM, et al. Ovine uterine gland knock-out model: effects of gland ablation on the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gray CA, Burghardt RC, Johnson GA, et al. Evidence that absence of endometrial gland secretions in uterine gland knockout ewes compromises conceptus survival and elongation. Reproduction. 2002;124:289–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arai Y, Gorski RA. Protection against the neural organizing effect of exogenous androgen in the neonatal female rat. Endocrinology. 1968;82:1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weinstein MA, Pleim ET, Barfield RJ. Effects of neonatal exposure to the antiprogestin mifepristone, RU 486, on the sexual development of the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;41:69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wagner CK, Quadros PS. Progesterone and sexual differentiation of the developing brain. In: Handa R, Hayashi S, Terasawa E, Kawata M, eds. Neuroplasticity, Development, and Steroid Hormone Action. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2001:343–360. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Konno T, Rempel LA, Arroyo JA, Soares MJ. Pregnancy in the Brown Norway rat: a model for investigating the genetics of placentation. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Konno T, Rempel LA, Rumi MA, et al. Chromosome-substituted rat strains provide insights into the genetics of placentation. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:930–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulac-Jericevic B, Mullinax RA, DeMayo FJ, et al. Subgroup of reproductive functions of progesterone mediated by progesterone receptor-B isoform. Science. 2000;289:1751–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hagan CR, Lange CA. Molecular determinants of context-dependent progesterone receptor action in breast cancer. BMC Med. 2014;12:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mukherjee A, Soyal SM, Fernandez-Valdivia R, et al. Steroid receptor coactivator 2 is critical for progesterone-dependent uterine function and mammary morphogenesis in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6571–6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kommagani R, Szwarc MM, Kovanci E, et al. A murine uterine transcriptome, responsive to steroid receptor coactivator-2, reveals transcription factor 23 as essential for decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2014;90:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Branham WS, Sheehan DM. Ovarian and adrenal contributions to postnatal growth and differentiation of the rat uterus. Biol Reprod. 1995;53:863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shapiro BH, Goldman AS, Bongiovanni AM, et al. Neonatal progesterone and feminine sexual development. Nature. 1976;264:795–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kincl FA, Maqueo M. Prevention by progesterone of steroid-induced sterility in neonatal male and female rats. Endocrinology. 1965;77:859–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dorfman RI. The antiestrogenic and antiandrogenic activities of progesterone in the defense of a normal fetus. Anat Rec. 1967;157:547–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hewitt SC, Korach KS. Oestrogen receptor knockout mice: roles for oestrogen receptors α and β in reproductive tissues. Reproduction. 2003;125:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Large MJ, DeMayo FJ. The regulation of embryo implantation and endometrial decidualization by progesterone receptor signaling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;358:155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, et al. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11162–11166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ, Funk CR, et al. Mice lacking progesterone receptor exhibit pleiotropic reproductive abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2266–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hewitt SC, Kissling GE, Fieselman KE, et al. Biological and biochemical consequences of global deletion of exon 3 from the ER α gene. FASEB J. 2010;24:4660–4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Franco HL, Rubel CA, Large MJ, et al. Epithelial progesterone receptor exhibits pleiotropic roles in uterine development and function. FASEB J. 2012;26:1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nanjappa MK, Medrano TI, March AG, et al. Neonatal uterine and vaginal cell proliferation and adenogenesis are independent of estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nanjappa MK, Medrano TI, Lydon JP, et al. Maximal dexamethasone inhibition of luminal epithelium proliferation involves progesterone receptor (PR)- and non-PR-mediated mechanisms in neonatal mouse uterus. Biol Reprod. 2015;92:122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]