Abstract

To elucidate mechanisms underlying epidemiological findings of decreased risk of glioma development in patients with allergies and asthma, gliomas were induced in mice deficient for histidine decarboxylase (HDC), the enzyme responsible for histamine production. These mice exhibited shortened survival and enhanced tumor growth compared to wild-type (WT) mice. Previous studies have shown a pivotal role of HDC in maturation of bone marrow (BM)-derived myeloid cells. In our glioma models, brain-infiltrating leukocytes (BIL) demonstrated an increased frequency of CD11b+Gr1+ immature myeloid cells (IMC; both CD11b+Ly6G+ and CD11b+Ly6C+ subpopulations) as well as diminished CD8+ T cell infiltration and their effector functions in HDC−/− mice compared with WT mice. Furthermore, HDC−/− IMC demonstrated a more profound immune suppression of CD8+ T cell proliferation and functions associated with increased prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) expression levels. Celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, which is vital for PGE2 production, abrogated suppressive capabilities of HDC−/− IMC. In addition, glioma-bearing HDC-eGFP mice, in which HDC promoter drives green fluorescence protein (GFP) expression, exhibited decreased HDC promoter activities in CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the BM, spleen, and intracranial tumor site compared with non-tumor bearing HDC-eGFP mice. Additionally, in vitro culture with glioma supernatants decreased GFP expression in CD11b+Gr1+, CD11b+Ly6G+, and CD11b+Ly6C+ IMC. HDC expression levels inversely correlated with suppressive functions of CD11b+Gr1+ IMC, as GFP−CD11b+Gr1+ more profoundly inhibited CD8+ T cell proliferation compared with CD11b+Gr1+GFP+ cells. Taken together, these data show a significant role of HDC in the glioma microenvironment via maturation of myeloid cells and resulting activation of CD8+ T cells.

Keywords: glioma, histamine, histidine decarboxylase, myeloid cells, prostaglandin E2

Introduction

Multiple epidemiological studies have consistently established a history of allergy, as well as a significant dose-response with increasing number of allergens, as a protective factor for glioma development.1-3 In addition, patients with glioma and allergies are up to 3.5 times more likely to report chronic anti-histamine use (>10 years) compared to controls, and long-term anti-histamine use is associated with increased risk of glioma.4,5 These epidemiological studies suggest unexplained roles of the histamine pathway in immunosurveillance and survival in glioma patients.

Histamine is a biogenic amine that has been studied extensively in atopic conditions such as allergy and asthma and has been shown to modulate the immune system.6 Histamine is primarily produced endogenously by L-HDC, which converts L-histidine to histamine, but can be incorporated exogenously from oral intake of histamine.7 Previously, HDC has been examined in the induction of skin and colon cancer.8 HDC is primarily expressed in BM CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs, and its expression is vital for myeloid maturation. HDC−/− mice possess increased CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs in the BM, spleen, as well as peripheral blood, and exogenous histamine promotes differentiation of IMCs. In chemical carcinogen-induced models of skin and colon cancer, HDC−/− mice exhibited accelerated growth of cancer in compared with WT mice as well as enhanced tumor-infiltration by IMCs.8 In these models, increased IMCs directly promote tumor angiogenesis.8

Multiple tumor-derived factors including growth factors and cytokines have been demonstrated to promote the development of tumor-promoting IMCs by halting their normal differentiation into mature antigen-presenting cells and inducing immunosuppressive effectors in IMCs, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), 9 inducible nitric oxide synthase,10, and arginase 1.10,11 These cells have been shown to promote tumor development by inhibiting T cell-mediated antitumor immunity as well as directly promoting tumor proliferation, survival, angiogenesis, and invasion.12,13

We have demonstrated that depletion of these cells inhibits glioma growth and prolongs survival in murine models.14,15 We have also reported a protective effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) blockade against the development of IMCs and glioma.14 In the current report, we extended our study to elucidate the bioimmunological mechanism underlying the epidemiological finding of use of histamine inhibitors as a risk factor for development of malignant glioma. We demonstrate that histamine is involved in myeloid cell maturation using histamine-deficient HDC−/− mice, and that HDC−/− IMCs suppress CD8+ T cell responses more profoundly than control IMCs. In addition, we demonstrate that glioma-derived factors can suppress HDC expression in CD11b+Gr1+ IMC, thereby potentiating immunosuppressive activities and the resulting glioma growth.

Results

Histamine deficiency promotes glioma development in vivo

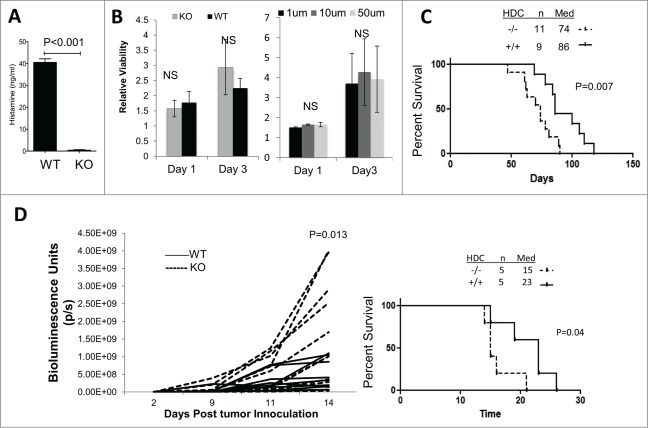

To address the role of histamine on glioma development, we induced de novo gliomas by intraventricular transfection of NRas, EGFRvIII, and small hairpin RNA against p53, utilizing the Sleeping Beauty (SB) transposon system in both histamine deficient HDC−/− and WT mice (both are BALB/c-background). A previous report has demonstrated the relationship between HDC activity and histamine levels in various tissues, specifically that HDC−/− mice possess reduced and/or near-zero levels of histamine compared to WT mice.16 Histamine levels were confirmed to be substantially lowered in peripheral circulation in HDC−/− compared to WT mice (Fig. 1A). To assess the direct effect of HDC expression and histamine on the proliferation of glioma cells in vitro, we established cell lines derived from SB-induced gliomas in WT and HDC−/− mice and observed no significant differences in their in vitro proliferation rates (Fig. 1B; left). Additionally, when we added exogenous histamine to the culture of HDC−/− glioma cell lines at varying concentrations (1, 10, and 50 µM), we did not see any effects on their proliferation rates (Fig. 1B, right). However, in vivo, HDC−/− mice bearing SB-induced de novo gliomas exhibited shorter survival compared with WT mice (Fig. 1C). To determine the role of host-derived HDC without any confounding effect of tumor cell-derived histamine, we stereotactically inoculated SB-derived HDC−/− glioma cells in WT or HDC−/− mice, and found that HDC−/− hosts exhibited significantly larger tumors based on bioluminescence imaging (BLI) at day 14 compared with WT mice (Fig. 1D, left). Accordingly, HDC−/− mice also exhibited significantly shorter survival compared with WT mice after these mice received inoculation of HDC−/− glioma cells (Fig. 1D, right). These data suggest a potential role of host-derived HDC as a modulator of glioma growth. Our data also suggest that the differential tumor growth between HDC−/− and WT mice is probably not due to direct effects of HDC or histamine on tumor proliferation, but more likely attributable to effects on host-derived non-tumor cells.

Figure 1.

Effects of HDC disruption on glioma development. (A) Histamine concentrations (ng/mL) from peripheral blood of mice (WT n = 5, HDC−/− n = 3) measured via Immunoassay. (B) Glioma cell lines derived from SB gliomas in WT and HDC−/− mice (Left; three independent cell lines/group) and HDC−/− glioma cells in the presence of exogenous histamine at indicated concentrations (Right) were incubated for 3 d and WST-1 assay was performed for proliferation of viable cells. Y-axis indicates relative viability of the cells at the specified day compared to cells initially plated at day 0. (C) Gliomas were induced in neonatal WT and HDC−/− mice as the de novo SB model. Survival following tumor induction was monitored. (D) HDC−/− SB glioma cells were inoculated into the brain of HDC−/− or WT mice (n = 10 mice/group). Tumor growth via bioluminescent imaging was monitored (Left). P values were based on two-side student t test. Survival following tumor inoculation was monitored (Right; n = 5 mice/group).

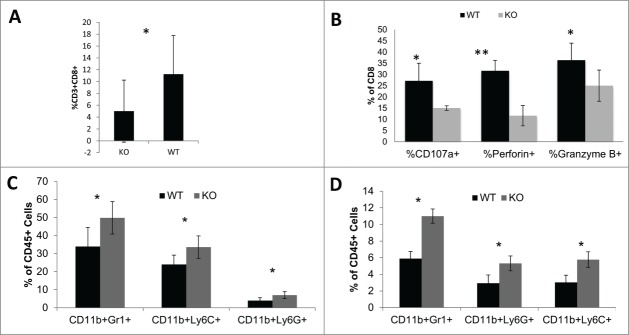

Accelerated glioma growth in HDC−/− mice is concomitant with decreased CD8+ T cells and increased CD11b+Gr1+ immature myeloid cells (IMC) in the tumor

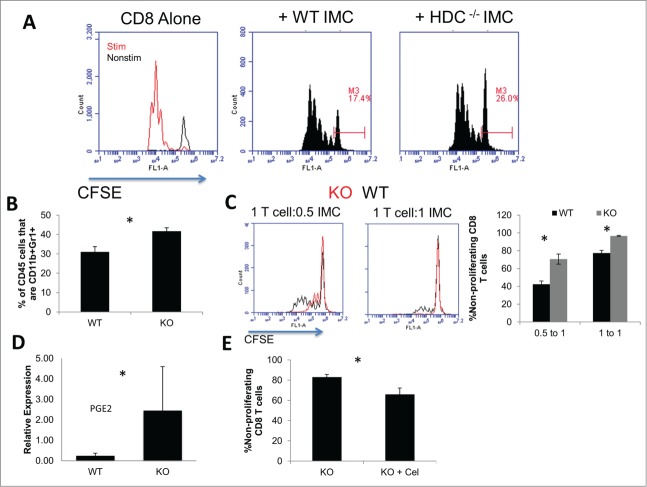

Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells have been shown to have a positive prognostic impact.17 To determine the impact of histamine production on the immunological environment of gliomas, we examined brain-infiltrating leukocytes (BIL) in glioma. While gliomas in both WT and HDC−/− mice were infiltrated by CD3+CD8+ T cells, HDC−/− mice demonstrated decreased percentages of CD8+ T cells in BILs compared with WT mice ( P = 0.033) (Fig. 2A). In addition, CD8+ T cells in HDC−/− mice exhibited decreased levels of effector markers, CD107a (P = 0.043), granzyme B (P = 0.049), and perforin (P = 0.0001) compared with CD8+ T cells from WT mice (Fig. 2B). However, no differences were observed in splenic CD8+ T cells, or CD4+ T cells in BILs or spleen (data not shown). These data indicate the HDC deficiency can affect the immunological microenvironment of gliomas, specifically by suppressing numbers and functions of CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2.

Effects of HDC on immunological microenvironment. SB-derived HDC−/− glioma cells were inoculated into the brain of HDC−/− (KO) and WT mice. Mice were sacrificed when tumor were of similar size via BLI; i.e., day 10–12 following the inoculation. BILs were isolated and analyzed for: (A) %CD8+ T cells of total CD45+ cells (n = 10 mice/group); (B) CD8+ T cell function including CD107a, perforin, and granzyme B. (C and D) Percentages of CD11b+Gr1+, CD11b+Ly6C+ and CD11b+Ly6G+ IMCs in CD45+ (n = 5 mice/group) (C) BILs and (D) splenocytes. *: P<0.05, **: P<0.01

Previous reports have shown that HDC−/− mice possess an altered immune milieu, specifically increased levels of CD11b+Gr1+ IMC.18,19 Our analysis of BIL revealed increased CD11b+Gr1+ cells in HDC−/− mice compared with WT (Fig. 2C). Additionally, there was an increase of both CD11b+Ly6G+ granulocytic(G)-IMC and CD11b+Ly6C+ monocytic(M)-IMC subpopulations 13 in BIL (Fig. 2C) and spleen (Fig. 2D).

More profound suppressive function of CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs from HDC−/− mice

CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs phenotypically resemble myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), which represent a significant population of BIL found in human20 and mice glioma.15 MDSC can be phenotypically heterogeneous, and the coalescing factor is their ability to suppress T cell functions.21–23 To determine whether the HDC status impacts on immunosuppressive functions of MDSC-like cells in our glioma model, CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs isolated from gliomas in HDC−/− and WT mice were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled naive WT CD8+ T cells. A larger population of non-proliferating CD8+ T cell population was observed when co-cultured with HDC−/− mouse-derived IMCs compared with WT mouse-derived counterparts (Fig. 3A). As tumor-infiltrating MDSC have been shown to be BM-derived,15,24 we sought to utilize BM cells derived from WT and HDC−/− mice to gain further understanding in the role of HDC in myeloid maturation and suppressive functions. When WT and HDC−/− BM cells were cultured under MDSC-inducing conditions (BM-MDSC),15 HDC−/− BM cells demonstrated an increased yield of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in compared with WT cells, suggesting that defects of HDC signal promotes accumulation of IMCs (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, HDC−/− BM-IMC inhibited proliferation of CD8+ T cells compared with WT counterparts (Fig. 3C). Additionally, we observed increased levels of PGE2 expression in HDC−/− BM-IMC compared to WT (Fig. 3D). To determine whether the increased PGE2 has a direct impact on the suppressive functions of HDC−/− IMCs, we cultured HDC−/− BM-IMC with COX2 inhibitor, celecoxib, which reversed the suppression and improved T cell proliferation (Fig. 3E). We have previously shown that celecoxib is capable of maturing IMCs and reducing immunosuppressive effectors in myeloid cells. 14 Both pathways are involved in mediating atopy and regulating immune responses,25 and our data suggest that PGE2 may be one of mediators of the augmented suppressive function of HDC−/− IMC.

Figure 3.

Role of HDC in IMC-mediated immunosuppression. (A) CD11b+Gr1+ cells were isolated from HDC−/− and WT tumor BIL via FACS, then co-cultured with CFSE-labeled WT CD8+ T cells in the presence of CD3/CD28-stimulation for 3 d. Gates depict non-proliferating populations. Representative histograms of pooled BIL from five mice/group are shown. (B) BM cells from HDC−/− and WT mice were cultured with GM-CSF, G-CSF, and IL-13 for 10 d for induction of BM-IMC. Percentages of CD11b+Gr1+ cells in all CD45+ cells after culture are depicted for WT and HDC−/− groups (n = 5/group). (C) Induced BM-IMCs were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells using the same method as (A) for 3 d at ratios of 0.5 IMC to 1 T cell and 1 IMC to 1 T cell. Representative histograms of CFSE in CD8+ T cells (Left) and quantitative data of non-proliferating CD8+ T cells (Right) are depicted. (D) RT-PCR of PTGS2 (the transcript for PGE2) expression in HDC−/− (KO) and WT BILs. (E) HDC−/− BM-IMC were cultured under similar conditions as experiments depicted in (C) with or without the addition of celecoxib added on day 7. Data represent one of two separate experiments with similar results. *, P <0.05.

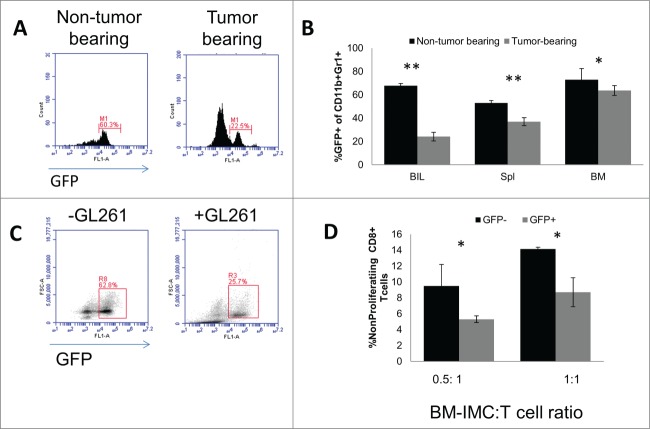

Glioma-bearing conditions decrease expression of HDC in CD11b+Gr1+ IMC

Gliomas are notoriously immunosuppressive. Many glioma-derived factors have been demonstrated to inhibit maturation of myeloid cells, promote development of IMCs, and induce immunosuppressive effectors including M-CSF, PGE2, TGFβ, and recruitment of regulatory T cells.26,27 We examined if glioma could affect expression of HDC and immune cell function. As previously shown, HDC is primarily expressed in CD11b+Gr1+ cells in the BM,8 which was corroborated in our own analysis (data not shown). To elucidate in vivo effects of glioma-bearing conditions on HDC expression, we inoculated GL261 glioma cells into the brain of HDC-eGFP mice, which express GFP under the HDC promoter. In tumor-bearing mice, CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs isolated from the brain (Fig. 4A), spleen, and BM (Fig. 4B) revealed decreased levels of GFP expression compared with IMCs from non-tumor bearing mice. Similar results were observed with in vitro culture of BM cells, where addition of GL261 glioma-derived culture-supernatants led to a decrease in GFP expression in CD11b+Gr1+ cells (Fig. 4C). This change was observed in both CD11b+Ly6C+ M-IMC and CD11b+Ly6G+ G-IMC populations (data not shown). To determine whether the GFP expression status is associated with any changes in the suppressive function of CD11b+Gr1+ cells, we utilized FACS-sorted GFP+ and GFP− CD11b+Gr1+ cells, and co-cultured them with naïve CFSE-labeled CD8 T+ cells. We observed an inverse association between GFP expression and suppressive capabilities. GFP−CD11b+Gr1+ cells exhibited a more profound suppression of T cell proliferation compared with their GFP+ counterparts (Fig. 4D). The presence of glioma is associated with reduced HDC-GFP expression in IMC, thereby inducing a more profound immunosuppression.

Figure 4.

Effects of glioma-bearing conditions on GFP expression in CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs of HDC-GFP mice. (A) Representative histograms of GFP expression in CD11b+Gr1+ BILs in non-tumor-bearings mice and mice bearing intracranial GL261 glioma. (B) Percentages of GFP+ cells in CD11b+Gr1+ populations in BILs, spleen, and BM in non-tumor-bearing and tumor-bearing mice (n = 4 mice/group). (C) BM cells were cultured for induction of BM-IMCs with or without GL261 culture-supernatants. Representative histograms of GFP expression in CD11b+Gr1+ cells are shown (n = 3 mice/group). (D) FACS-isolated GFP+ and GFP− CD11b+Gr1+ were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells for 3 d at ratios of 0.5 IMC to 1 T cells and 1 IMC to 1 T cells. Percentages non-proliferating cells in total CD8+ T cells are shown (three mice/group). *, P<0.05. **, P<0.01.

Discussion

In this study, intrigued by decreased risks of glioma in asthma patients and the rather increased risks in patients who chronically use anti-histamines, we aimed to determine the role of histamine via HDC expression in glioma development. Although which anti-histamines were used was not specifically addressed in these epidemiology studies, histamine receptor 1 (H1R) antagonists are most commonly used.4,5 In our current study, we utilized a global blockade of histamine production via HDC−/− mice in our established de novo and transplant glioma models. We observed a significantly shortened survival in HDC−/− mice (Fig. 1C). Similar results were seen in our intracranial glioma cell injection model as HDC−/− hosts exhibited more rapid tumor growth than control WT mice (Fig. 1D). A previous study has demonstrated that histamine promotes differentiation of IMC and leads to reduced tumor progression in vivo.8 Based on our data showing histamine does not directly affect tumor growth, it is likely that histamine may influence the immune microenvironment. A previous report has shown that glioma cells can secrete histamine. 28 We utilized HDC−/− glioma cells for our cell inoculation model in WT and HDC−/− mice to eliminate any possible effect of histamine production by glioma cells. Interestingly, when we inoculated glioma cells derived from WT (HDC+/+) mice, the differential survival observed in Fig. 1D was no longer apparent (data not shown). Since there was no difference in intrinsic growth rate difference between HDC−/− and WT tumors in vitro, we presumed that these data suggest a possibly critical role of glioma cell-derived histamine activity on altering immune milieu, as multiple glioma cell lines have demonstrated ability to secrete histamine in vitro.28 The specific impact of systemic versus local histamine production on the immune environment requires further exploration.

In this study, we utilized HDC as a surrogate for histamine status. Further experiments will examine the role of exogenous histamine as a modulator of immune surveillance. Previous clinical trials have examined histamine as an adjuvant to interleukin-2 treatment for certain cancer types with modest benefits.29,30 In these referenced studies, administration of histamine resulted in decreased circulating macrophages and more robust T cell response, consistent with the decrease of IMCs in our study (Fig. 2). The possible impact of addition of exogenous histamine to other immunotherapies such as peptide vaccines or adoptive therapies is unknown and may warrant further investigation.

Our examinations focused on the impact of HDC on induction of immunosuppression. A previous study has indicated aberrant maturation of BM-derived myeloid cells, specifically increased CD11b+Gr1+ IMC derived from HDC−/− mice.8 Our analysis corroborated this previous study by demonstrating increased systemic and glioma-infiltrating populations of CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs in HDC−/− hosts (Figs. 2C and D). These cells have been shown to promote tumor growth via expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6), which can promote tumor growth and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer models.8 These cells phenotypically resemble MDSC, which can negate an adaptive T cell response.21 The definition of MDSC is a functional one, so we sought to show that these cells could suppress T cell response. HDC−/− CD11b+Gr1+ IMC derived from gliomas (Fig. 3A) as well as BM-IMC from HDC−/− mice (Fig. 3C) exhibited more profound suppression of CD8+ T cells in vitro compared with WT counterparts.

HDC−/− myeloid cells demonstrated increased activation of PGE2, which has known immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting effects.14,31,32 Addition of celecoxib, an inhibitor of PGE2, at least partially reversed immunosuppression by HDC−/− BM-IMC (Fig. 3E). However, the moderate degree of reversal by celecoxib strongly suggests that there are other mechanisms underlying the effects of HDC. Nonetheless, based on these data, we can surmise that HDC expression is involved in myeloid cell maturation, and that deficiency promotes the accumulation of CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs as well as induction of immunosuppressive function at least partially via increased production of PGE2.

Similarly, ex vivo examination of CD8+ BIL populations corroborated the in vitro results of T cell inhibition, as HDC−/− BIL demonstrated reduced CD8+ T cell populations and functions (Figs. 2A and B). Whereas our co-culture results revealed a role for IMCs as a regulator of T cell function, histamine may also influence T cells in other manners. T cells were not shown to express HDC,8 but they do express histamine receptors. Histamine has been shown to affect differentiation toward type 1 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, primarily via histamine 1 receptor signaling (H1R).33-35 HDC−/− CD8+ BILs showed no differences in IFNγ production levels compared with WT counterparts in our study (data not shown), which may be due to the impact of global histamine deficiency rather than knockdown of a single receptor (Fig. 2B). Additionally, histamine deficiency has been shown to reduce antigen presentation by dendritic cells, resulting in reduced CD8+ T cell priming and function.34 This was also mediated primarily by H1R signaling on dendritic cells.34 In our studies, HDC−/− mice showed increased IMC in both BILs and the spleen (Figs. 2D and E). Although we did not specifically examine antigen-presentation capabilities, it is possible that HDC deficiency may also affect T cell priming and modulate T cell function via altered antigen-presentation efficiencies in addition to influencing regulatory populations. A more comprehensive analysis of the effects of lack of histamine on T cell function is required.

Gliomas are notorious for potentiating immunosuppression to promote their own development. In glioma-bearing conditions, we observed a decrease in HDC expression, specifically in CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs not only in the tumor tissue but also in the spleen and BM (Fig. 4B). In vitro, addition of glioma culture-supernatants led to a decrease in the HDC transcription in both G-IMC and M-IMC subtypes of CD11b+Gr1+ BM cells (Fig. 4C). Functionally, the GFP− cells demonstrated more profound immune suppression (Fig. 4C), suggesting that loss of HDC is linked to induction of immunosuppressive effectors. These findings of tumor-induced downregulation of HDC are consistent with previous observations with colorectal cancer cells.8 The specific glioma-derived factors that can possibly suppress expression of HDC is currently unknown. Many tumor-derived cytokines and growth factors have been shown to induce the MDSC phenotype, but none have been previously shown to act via the HDC pathway. Based on our data with glioma cell culture supernatants, it can be hypothesized that at least one of those can be a secreted factor. As demonstrated in Fig. 3D and E, PGE2 was upregulated in HDC−/− IMC and blockade of the COX-2 pathway partially abrogated the T cell suppression. Therefore, PGE2 may be regulated by HDC. Future studies will examine the specific secreted factors that can regulate HDC, leading to immaturity of myeloid cells as well as other mechanisms, such as preferential recruitment and/or survival of HDC−/− IMC in the glioma microenvironment.

Methods

Animals

WT (BALB/c) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. Histamine-deficient HDC−/− BALB/c mice have been previously described (Columbia University).8 Animals were handled in Animal Facility in the University of Pittsburgh per an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol.

Histamine Concentration Assay

Mice were bled from their submandibular veins. Sera were collected and separated by Microtainer tube with serum separator (BD Biosciences). Histamine in serum samples was measured by using histamine enzyme immunoassay per manufacturer's directions (Bechman Coulter).

Sleeping Beauty de novo glioma model

The procedure was performed as described previously.36,37 In vivo compatible DNA transfection reagent (In vivo-JetPEI) was obtained from Polyplus Transfection. The following plasmids were used for glioma induction: T2/C-Luc//PGK-SB13 (0.125 μg), pT/CAGGS-NRASV12 (0.125 μg), pT2/shP53 (0.125 μg), and PT3.5/CMV-EGFRvIII (0.125 μg). Tumor size was monitored via BLI using IVIS200 (Caliper Life Sciences). Glioma cell lines from both WT and HDC−/− mice were established from de novo gliomas as described above and subsequent in vitro culture and cloning in our laboratory.

Intracranial Glioma Cell Inoculation

The procedure to establish glioma cell lines from SB transposon-mediated de novo murine gliomas has been described previously.14,36 Mice were intracranially inoculated with glioma cells in 2 μL of PBS at the bregma 3 mm to the right side of sagittal suture and 3.5 mm below the surface of skull using stereotactic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA), stereotaxic injector (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) and 10 μL Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Nero, NV) under anesthesia, as we described previously.38 GL261 cells were kindly provided by Dr Robert M. Prins (University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA).

Isolation of brain-infiltrating leukocytes (BIL)

The procedure for isolation of BIL via Percoll density gradient has been described by us previously.14,36

Bone marrow (BM)-IMC bone marrow culture

A similar procedure has been previously described. 15,24 Briefly, red blood cell (RBC)-depleted BM cells were isolated from WT and HDC−/− mice. At day 0, GM-CSF (100 ng/mL) and G-CSF(100 ng/mL) were added to cultures. At day 3 and day 9, GM-CSF (100 ng/mL), G-CSF (100 ng/mL), and IL-13 (80 ng/mL) were added. All cytokines were purchased from Peproptech. At day 10, BM cells were cultured isolated for co-culture with CD8+ T cells. Celecoxib was purchased from Sigma and used at 50 um/mL.

IMC-mediated T cell inhibition

Naïve CD8+ T cells were isolated WT BALB/c splenocytes using magnetic bead-negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec), labeled with 1nM CFDA-SE (Invitrogen), and incubated with varying numbers of cultured or FACS-sorted CD11b+Gr1+ IMCs from gliomas in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Invitrogen) and 30 U/mL of hIL-2 (Peprotech). Cells were analyzed via flow cytometry on an AccuriC6 (BD Biosciences).

Real-time PCR

The procedure was described previously.15,36 The following primers were obtained from Applied Biosystems: GAPDH(Mm99999915_g1) PROSTAGLANDINE2 (Mm00478374_m1).

Flow Cytometry

Samples were analyzed on Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) via CFlow Plus (BD Biosciences). Antibodies utilized: anti-CD4+ (VH129.19), anti-CD8+ (53-6.7), and anti-Ly6C (AL-21) from BD Biosciences; anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD107a (1D4B), anti-FoxP3 (NRRF-30), and anti–Gr-1 (RB6- 8C5) from eBioScience; anti-Ly6G (1A8) from BioLegend. FACS-sorting was performed on BD MoFlo Astrios.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test was carried out to analyze differences between two groups. Log-rank tests were done to analyze survival of mice with glioma. Value of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed by Graphpad Prism.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Grants from The NIH [5T32CA082084, 2R01 NS055140, 2P01 NS40923, 1P01 CA132714, 5U24AI082673] and Musella Foundation for Brain Tumor Research and Information. This project used UPCI shared resources (Animal Facility, Small Animal Imaging facility, Cell and Tissue Imaging Facility, and Cytometry Facility) that are supported in part by NIH P30CA047904.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Linos E, Raine T, Alonso A, Michaud D. Atopy and Risk of Brain Tumors: A Meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99:1544-50; PMID:17925535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/djm170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiemels JL, Wiencke JK, Sison JD, Miike R, McMillan A, Wrensch M. History of allergies among adults with glioma and controls. Int J Cancer 2002; 98:609-15; PMID:11920623; http://dx.doi.org/16076292 10.1002/ijc.10239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Diepgen TL. Is atopy a protective or a risk factor for cancer? A review of epidemiological studies. Allergy 2005; 60:1098-111; PMID:16076292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00813.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheurer ME, Amirian ES, Davlin SL, Rice T, Wrensch M, Bondy ML. Effects of antihistamine and anti-inflammatory medication use on risk of specific glioma histologies. Int J Cancer 2011; 129:2290-6; PMID:21190193; http://dx.doi.org/9819373 10.1002/ijc.25883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheurer ME, El-Zein R, Thompson PA, Aldape KD, Levin VA, Gilbert MR, Weinberg JS, Bondy ML. Long-term anti-inflammatory and antihistamine medication use and adult glioma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17:1277-81; PMID:18483351; http://dx.doi.org/9819373 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Pouw Kraan TC, Snijders A, Boeije LC, de Groot ER, Alewijnse AE, Leurs R, Aarden LA. Histamine inhibits the production of interleukin-12 through interaction with H2 receptors. J Clin Investig 1998; 102:1866-73; PMID:9819373; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI3692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colucci R, Fleming JV, Xavier R, Wang TC. L-histidine decarboxylase decreases its own transcription through downregulation of ERK activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2001; 281:G1081-91; PMID:11557529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang XD, Ai W, Asfaha S, Bhagat G, Friedman RA, Jin G, Park H, Shykind B, Diacovo TG, Falus A et al.. Histamine deficiency promotes inflammation-associated carcinogenesis through reduced myeloid maturation and accumulation of CD11b+Ly6G+ immature myeloid cells. Nat Med 2011; 17:87-95; PMID:21170045; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmielau J, Finn OJ. Activated granulocytes and granulocyte-derived hydrogen peroxide are the underlying mechanism of suppression of t-cell function in advanced cancer patients. Cancer Res 2001; 61:4756-60; PMID:11406548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu CY, Wang YM, Wang CL, Feng PH, Ko HW, Liu YH, Wu YC, Chu Y, Chung FT, Kuo CH et al.. Population alterations of l-arginase- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressed CD11b+/CD14-/CD15+/CD33 + myeloid-derived suppressor cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2010; 136:35-45; PMID:19572148; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00432-009-0634-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, Hernandez C, Signoretti S, Zabaleta J, McDermott D, Quiceno D, Youmans A, O'Neill A, Mier J et al.. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res 2005; 65:3044-8; PMID:15833831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condamine T, Gabrilovich DI. Molecular mechanisms regulating myeloid-derived suppressor cell differentiation and function. Trends Immunol 2011; 32:19-25; PMID:21067974; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.it.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:253-68; PMID:22437938; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita M, Kohanbash G, Fellows-Mayle W, Hamilton RL, Komohara Y, Decker SA, Ohlfest JR, Okada H. COX-2 blockade suppresses gliomagenesis by inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res 2011; 71:2664-74; PMID:21324923; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohanbash G, McKaveney K, Sakaki M, Ueda R, Mintz AH, Amankulor N, Fujita M, Ohlfest JR, Okada H. GM-CSF Promotes the Immunosuppressive Activity of Glioma-Infiltrating Myeloid Cells through Interleukin-4 Receptor-alpha. Cancer Res 2013; 73:6413-23; PMID:24030977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtsu H, Tanaka S, Terui T, Hori Y, Makabe-Kobayashi Y, Pejler G, Tchougounova E, Hellman L, Gertsenstein M, Hirasawa N et al.. Mice lacking histidine decarboxylase exhibit abnormal mast cells. FEBS Lett 2001; 502:53-6; PMID:11478947; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02663-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang I, Tihan T, Han SJ, Wrensch MR, Wiencke J, Sughrue ME, Parsa AT. CD8+ T-cell infiltrate in newly diagnosed glioblastoma is associated with long-term survival. J Clin Neurosci 2010; 17:1381-5; PMID:20727764; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bencsath M, Gidali J, Szeberenyi J, Veszely G, Hegyi K, Falus A. Regulation of murine hematopoietic colony formation by histamine. Inflamm Res 2000; 49 Suppl 1:S66-7; PMID:10864426; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/PL00000187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang XD, Ai W, Asfaha S, Bhagat G, Friedman RA, Jin G, Park H, Shykind B, Diacovo TG, Falus A et al.. Histamine deficiency promotes inflammation-associated carcinogenesis through reduced myeloid maturation and accumulation of CD11b+Ly6G+ immature myeloid cells. Nat Med 2011; 17:87-95; PMID:21170045; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raychaudhuri B, Rayman P, Ireland J, Ko J, Rini B, Borden EC, Garcia J, Vogelbaum MA, Finke J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and function in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol 2011; 13:591-9; PMID:21636707; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/neuonc/nor042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peranzoni E, Zilio S, Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Zanovello P, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity and subset definition. Curr Opin Immunol 2010; 22:238-44; PMID:20171075; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava MK, Sinha P, Clements VK, Rodriguez P, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells inhibit T-cell activation by depleting cystine and cysteine. Cancer Res 2010; 70:68-77; PMID:20028852; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youn J-I, Gabrilovich DI. The biology of myeloid-derived suppressor cells: The blessing and the curse of morphological and functional heterogeneity. Eur J Immunol 2010; 40:2969-75; PMID:21061430; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.201040895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Highfill SL, Rodriguez PC, Zhou Q, Goetz CA, Koehn BH, Veenstra R, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Serody JS, Munn DH et al.. Bone marrow myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) via an arginase-1–dependent mechanism that is up-regulated by interleukin-13. Blood 2010; 116:5738-47; PMID:20807889; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2010-06-287839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dy M, Schneider E. Histamine-cytokine connection in immunity and hematopoiesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2004; 15:393-410; PMID:15450254; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolle CE, Sengupta S, Lesniak MS. Mechanisms of immune evasion by gliomas. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 746:53-76; PMID:22639159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4614-3146-6_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sughrue ME, Yang I, Kane AJ, Rutkowski MJ, Fang S, James CD, Parsa AT. Immunological considerations of modern animal models of malignant primary brain tumors. J Transl Med 2009; 7:84; PMID:19814820; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1479-5876-7-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirohata M, Sasaguri Y, Shigemori M, Maruiwa H, Morimatsu M. A role for histamine in human-malignant glioma-cells. Int J Oncol 1995; 7:1109-15; PMID:21552939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asemissen AM, Scheibenbogen C, Letsch A, Hellstrand K, Thoren F, Gehlsen K, Schmittel A, Thiel E, Keilholz U. Addition of histamine to interleukin 2 treatment augments type 1 T-cell responses in patients with melanoma in vivo: immunologic results from a randomized clinical trial of interleukin 2 with or without histamine (MP 104). Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11:290-7; PMID:15671558 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brune M, Castaigne S, Catalano J, Gehlsen K, Ho AD, Hofmann WK, Hogge DE, Nilsson B, Or R, Romero AI et al.. Improved leukemia-free survival after postconsolidation immunotherapy with histamine dihydrochloride and interleukin-2 in acute myeloid leukemia: results of a randomized phase 3 trial. Blood 2006; 108:88-96; PMID:16556892; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochoa AC, Zea AH, Hernandez C, Rodriguez PC. Arginase, prostaglandins, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma. ClinCancer Res 2007; 13:721s-6s; PMID:1725530019000324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park W, Oh Y, Han J, Pyo H. Antitumor enhancement of celecoxib, a selective Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in a Lewis lung carcinoma expressing Cyclooxygenase-2. J Exp Cli Cancer Res 2008; 27:66; PMID:19000324; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-9966-27-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jutel M, Watanabe T, Klunker S, Akdis M, Thomet OA, Malolepszy J, Zak-Nejmark T, Koga R, Kobayashi T, Blaser K et al.. Histamine regulates T-cell and antibody responses by differential expression of H1 and H2 receptors. Nature 2001; 413:420-5; PMID:11574888; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35096564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noubade R, Milligan G, Zachary JF, Blankenhorn EP, del Rio R, Rincon M, Teuscher C. Histamine receptor H1 is required for TCR-mediated p38 MAPK activation and optimal IFN-gamma production in mice. J Clin Invest 2007; 117:3507-18; PMID:17965772; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI32792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vanbervliet B, Akdis M, Vocanson M, Rozieres A, Benetiere J, Rouzaire P, Akdis CA, Nicolas JF, Hennino A. Histamine receptor H1 signaling on dendritic cells plays a key role in the IFN-gamma/IL-17 balance in T cell-mediated skin inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:943–53 e1-10; PMID:21269673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujita M, Scheurer ME, Decker SA, McDonald HA, Kohanbash G, Kastenhuber ER, Kato H, Bondy ML, Ohlfest JR, Okada H. Role of type 1 IFNs in antiglioma immunosurveillance–using mouse studies to guide examination of novel prognostic markers in humans. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:3409-19; PMID:20472682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiesner SM, Decker SA, Larson JD, Ericson K, Forster C, Gallardo JL, Long C, Demorest ZL, Zamora EA, Low WC et al.. De novo induction of genetically engineered brain tumors in mice using plasmid DNA. Cancer Res 2009; 69:431-9; PMID:19147555; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujita M, Zhu X, Ueda R, Sasaki K, Kohanbash G, Kastenhuber ER, McDonald HA, Gibson GA, Watkins SC, Muthuswamy R et al.. Effective Immunotherapy against Murine Gliomas Using Type 1 Polarizing Dendritic Cells–Significant Roles of CXCL10. Cancer Res 2009; 69:1587-95; PMID:19190335; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]