Abstract

Until recently, the pathophysiological impact of natural killer (NK) lymphocytes has been largely elusive. Capitalizing on our previous discovery that NK cells mediate immunosurveillance against gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), we have now investigated the potential influence of immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive isoforms of the NK receptor NKp30 on the fate of infants with neuroblastoma. In three independent cohorts of high-risk neuroblastoma, we observed a similar prognostic impact of the ratio of immunostimulatory vs. immunosuppressive NKp30 isoforms. Patients with high-risk neuroblastoma that are in remission after induction chemotherapy have a higher risk of relapse if their circulating and bone marrow NK cells express the preponderantly immunosuppressive NKp30 C isoform, as determined by a robust RT-PCR-based assay. We also found that neuroblastoma cells express the NKp30 ligand B7-H6, which can be shed from the tumor cells. Elevated soluble B7-H6 levels contained in patient sera inhibited NK functions in vitro and correlated with downregulation of NK-p30 on NK cells, as well as with bone marrow metastasis and chemoresistance. Altogether, these results support the contention that NK cells play a decisive role in the immunosurveillance of neuroblastoma. In light of these results, efforts should be undertaken to investigate NK cell functions in all major cancer types, with the obvious expectation of identifying additional NK cell-related prognostic or predictive biomarkers and improving NK cell based immunotherapeutic strategies against cancer.

Keywords: immunosurveillance, neuroblastoma, NK cells, NKp30, pediatric cancer

Anticancer immunosurveillance has been best characterized at the level of specific MHC class I and class II-restricted T lymphocyte mediated responses against tumor-specific antigens. Nonetheless, there has been growing awareness over the last decade that innate immune responses, including those mediated by NK cells, play a major role in immunosurveillance against some tumor types, especially at the level of metastatic dissemination.1 This chronological sequence (T before NK cells) most likely does not indicate a hierarchy of importance between T and NK lymphocytes, but rather reflects three interrelated facts, namely, (i) a relatively poor knowledge on the physiology of NK cells (as compared to T lymphocytes), (ii) the existence of major species differences between mouse and human NK cells, and (iii) the absence of standardized tools for the functional exploration of human NK cells.2

On theoretical grounds, anticancer immunosurveillance may occur in two specific situations. First, natural immunosurveillance likely avoids most cancers to develop and may retard the progression of established neoplastic lesions. Second, immunosurveillance may be induced by therapeutic interventions against advanced cancers, for instance in the context of immunotherapies. Successful chemotherapies and immunotherapies may also re-establish a state of immunosurveillance through a variety of effects, ranging from the induction of immunogenic cancer stress or death to the direct stimulation of immune effectors or the reversal of immunosuppression.3 The therapeutic importance of NK cell-mediated immunosurveillance was first documented in one particular disease, namely GISTs that are treated with imatinib. This tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been used for the treatment of GIST based on the rational that it inhibits the oncogene product c-KIT, which is hyperactivated in GIST due to gain-of-function mutations. However beyond this direct effect on tumor cells, imatinib also inhibits the kinase activity of endogenous, non-mutated c-KIT in dendritic cells (DC), thereby activating a stimulatory crosstalk with NK cells. Indeed, in GIST patients treated with imatinib, circulating NK cells produce interferon-γ, and this effect correlates with the duration of the clinical response.4 Moreover, the phenotype of circulating NK cells related to NKp30 isoform expression predicted the long-term effects of imatinib therapy in GIST independently of the mutational status of c-KIT exon 11.5,6

The NCR3 gene (alternative protein name: CD337) encodes three isoforms of the NKp30 protein that are generated by alternative splicing and that have rather different biological functions. Ligation of the NKp30A and NKp30B isoforms of NKp30 induces cytotoxicity and Th1 cytokine secretion, respectively, while the NKp30C isoform triggers IL-10 release. Hence, NKp30A and NKp30B may be considered as immunostimulatory, while NKp30C is immunosuppressive.5 Importantly, it appears that there are major differences in the NKp30 isoform expression pattern among different individuals that are at least in part explained by polymorphisms in the NKp30 locus (and hence have a genetic basis) and which might also be influenced by gene methylation patterns (which implies an epigenetic mechanism). Although the NKp30 isoform expression profile can be modulated by culture of NK cells in the presence of DNA demethylating agents, the relative proportion of the three distinct isoforms are relatively constant. Thus, the ratio among distinct NKp30 isoforms measured in circulating leukocytes remained constant in chronological studies over several years, were not influenced by imatinib treatment and poly-chemotherapy, and did not differ from tumor-infiltrating and bone marrow derived NK cells.5,7 The method of choice for determining the relative expression of NKp30 A, B and C is a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), implying a high degree of accuracy and reproducibility.8

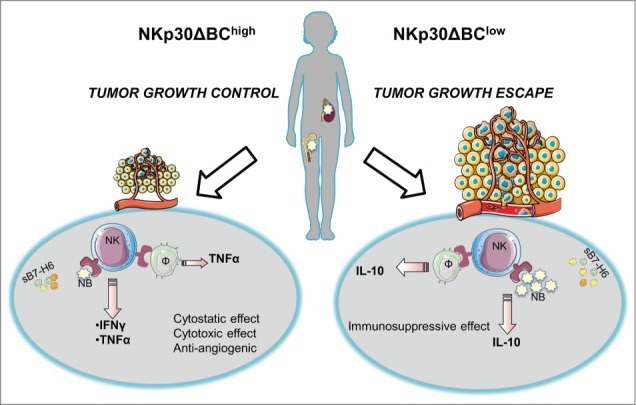

Based on these technological and immunological premises, we recently studied the impact of the NKp30 isoform expression profile on neuroblastoma, the most frequent extra-cranial cancer diagnosed in children (Fig. 1). We found that NKp30 isoforms correlate with the progression-free survival of high-risk neuroblastoma patients responding to induction chemotherapy in three independent cohorts (a first test cohort of 70 and two subsequent validation cohorts of 55 and 71 children), supporting the notion that NK cells control the residual neuroblastoma cells in the bone marrow.9 As compared to NK cells from healthy volunteers or patients with localized neuroblastoma, patients with metastatic disease exhibit deficient transcription of the immunostimulatory A and B isoforms of NKp30. A favorable ratio of NKp30B over the immunosuppressive NKp30C isoform predicts a relatively long time to progression after remission induced by induction chemotherapy and consolidated by myeloablative chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation.

Figure 1.

Two possible scenarios describe the NKp30 involvement in controlling high-risk neuroblastoma (HR-NB): in the first one, a favorable ratio of the NKp30B over the immunosuppressive NKp30C isoform (NKp30ΔBChigh) is associated with tumor growth control. In particular, the NKp30/B7-H6 recognition between NK lymphocytes and neuroblasts and/or monocytes elicits a Th1 response with consequent cytotoxic, cytostatic and anti-angiogenic effects. In the second possible scenario, the presence of a predominant immunosuppressive NKp30 isoform (NKp30ΔBClow) induces IL-10 production with a consequent immunosuppressive environment resulting in tumor growth. In addition, the soluble B7-H6 form (sB7-H6) is highly represented in both cases interfering with the NKp30/B7-H6 recognition. NB: neuroblastoma; Φ: monocyte; NK: natural killer lymphocyte; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; IFNγ: interferon γ; IL-10: interleukin-10.

In addition, a reduced frequency in circulating CD16+NK cells is associated with chemoresistance. On a per-cell basis, NKp30 expression is markedly downregulated in CD56dim NK cells from the metastatic bone marrow, where bone marrow infiltrating neuroblasts and monocytes express the NKp30 ligand B7-H6. In addition the concentrations of soluble B7-H6 in sera from neuroblastoma patients negatively correlated with the surface NKp30 expression protein. Moreover, elevated soluble B7-H6 levels correlate with NB progression and resistance to chemotherapy. In vitro assays revealed that sera containing high soluble B7-H6 might suppress IFNγ release by NK cells.9

Altogether it appears that three NK cell-related biomarkers may prove useful for risk stratification in neuroblastoma: (i) the circulating levels of immunosuppressive soluble B7-H6 protein, the NKp30 ligand, (ii) the expression level of total NKp30 protein per cell, and (iii) the relative expression of distinct NKp30 isoforms.9 Among these parameters, the last appears to be the most robust one, based on the relative ease of its measurement (by RT-PCR).

Thus far, systematic analyses addressing the importance of NK-mediated immunosurveillance across distinct cancer cell types are elusive. At this stage, we may suspect that NK cell-dependent immune responses against malignant cells are far more important for the therapeutic success of targeted therapy than anticipated.10 However, formal proof in favor of this conjecture is still missing.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Woo SR, Corrales L, Gajewski TF. Innate immune recognition of cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 2015; 33:445-74; PMID:25622193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caliguri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, Yokoyama WM, Ugolini S. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science 2011; 331:44-9; PMID:21212348; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1198687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Mechanism of action of conventional and targeted anticancer therapies: reinstating immunosurveillance. Immunity 2013; 39:74-88; PMID:23890065; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaput N, Flament C, Locher C, Desbois M, Rey A, Rusakiewicz S, Poirier-Colame V, Pautier P, Le Cesne A, Soria JC et al.. Phase I clinical trial combining imatinib mesylate and IL-2: HLA-DR NK cell levels correlate with disease outcome. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2:e23080; PMID:23525357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.23080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delahaye NF, Rusakiewicz S, Martins I, Menard C, Roux S, Lyonnet L, Paul P, Sarabi M, Chaput N, Semeraro M et al.. Alternatively spliced NKp30 isoforms affect the prognosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Nat Med 2011; 17:700-7; PMID:21552268; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rusakiewicz S, Semeraro M, Sarabi M, Desbois M, Locher C, Mendez R, Vimond N, Concha A, Garrido F, Isambert N et al.. Immune infiltrates are prognostic factors in localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res 2013; 73:3499-510; PMID:23592754; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rusakiewicz S, Nocturne G, Lazure T, Semeraro M, Flament C, Caillat-Zucman S, Sene D, Delahaye N, Vivier E, Chaba K et al.. NCR3/NKp30 contributes to pathogenesis in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Sci Transl Med 2013; 5:195ra96; PMID:23884468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prada N, Antoni G, Como F, Rusakiewicz S, Semeraro M, Boufassa F, Lambotte O, Meyer L, Gougeon ML, Zitvogel L. Analysis of NKp30/NCR3 isoforms in untreated HIV-1-infected patients from the ANRS SEROCO cohort. Oncoimmunology 2013; 2:e23472; PMID:23802087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/onci.23472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semeraro M, Rusakiewicz S, Minard-Colin V, Delahaye NF, Enot D, Vély F, Marabelle A, Papoular B, Piperoglou C, Ponzoni M et al.. Clinical impact of the NKp30/B7-H6 axis in high-risk neuroblastoma patients. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:283ra55; PMID:25877893; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrari de Andrade L, Ngiow SF, Stannard K, Rusakiewicz S, Kalimutho M, Khanna KK, Tey SK, Takeda K, Zitvogel L, Martinet L et al.. Natural killer cells are essential for the ability of BRAF inhibitors to control BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res 2014; 74:7298-308; PMID:25351955; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]