Abstract

Computer-assisted self-interviews were completed with a random sample of 163 unmarried Caucasian and African American men in a large metropolitan area. Almost a quarter (24.5%) of these men acknowledged committing an act since the age of 14 that met standard legal definitions of attempted or completed rape; an additional 39% had committed another type of sexual assault involving forced sexual contact or verbal coercion. An expanded version of the Malamuth et al. [1991] confluence model was examined using path analysis. The number of sexual assaults perpetrated by participants was associated with the direct or indirect effects of childhood sexual abuse, adolescent delinquency, alcohol problems, sexual dominance, positive attitudes about casual sexual relationships, and pressure from peers to engage in sexual relationships. Additionally, empathy buffered the relationship between sexual dominance and perpetration. The pattern of results was highly similar for African American and Caucasian men. The implications of these findings for sexual assault measurement are discussed and suggestions are made for alternative treatment programs.

Keywords: sexual assault perpetration, etiology, community samples, computer-assisted self-interviews, alcohol problems, sexual dominance

INTRODUCTION

Most research conducted with sexual assault perpetrators has examined either incarcerated sex offenders or college students. Only a handful of studies have been conducted with noncollege community samples. The study described here had two primary goals: (1) to examine the prevalence of self-reported sexual assault perpetration in an ethnically diverse community sample using computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) methodology, and (2) to determine the extent to which an expanded version of the confluence model [Malamuth et al., 1991], which has been used with college samples, would also be a useful framework for cross-sectional prediction of sexual assault perpetration in an ethnically diverse community sample. The relevant literature is reviewed below and then the study’s hypotheses are described.

Self-Reported Rates of Sexual Assault Perpetration in College Student Samples

In college studies of sexual assault perpetration, men answer behaviorally specific questions that include the legal elements of rape and other forms of sexual assault without labeling what occurred as a crime. The first study was conducted by Kanin in the 1960s, who found that 25.5% of the male college students he surveyed had forcefully tried to make a woman have sex with them since being in college [Kanin, 1967a, 1969]. The first large-scale study was conducted by Koss et al. [1987], who surveyed a nationally representative sample of 2,972 college men. Their Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) included 10 behaviorally specific questions that assessed forced sexual contact (e.g. verbally or physically forced kissing or sexual touching without penetration), verbally coerced sexual intercourse, and attempted and completed rape (attempted or completed penetration using physical force or alcohol) since the age of 14. Twenty-five percent of these men reported that they had committed some form of sexual assault; 7.7% had committed attempted or completed rape. Almost all of these sexual assaults occurred with women the men knew; about half occurred on dates. Numerous researchers have replicated these basic findings. Depending on the university and exactly how questions were phrased, self-reported rates of sexual assault perpetration have been as high as 61% and rates of attempted or completed rape have been as high as 15% [Abbey et al., 1998, 2001; Craig et al., 1989; Mills and Granoff, 1992; Muehlenhard and Linton, 1987; Rapaport and Burkhart, 1984; Wheeler et al., 2002].

Self-Reported Rates of Sexual Assault Perpetration in Community Samples

Only a few studies in specific localities have examined sexual assault perpetration in nonincarcerated, noncollege community samples. Calhoun et al. [1997] surveyed 65 young men in a rural community in Georgia who had recently participated in a study of school-aged youth. The average age of participants was 19 and most were Caucasian. Twenty-two percent of these men (n = 14) had perpetrated some type of sexual assault based on their answers to a modified version of the SES; 6.4% had committed an act that met standard legal definitions of completed rape. Senn et al. [2000] surveyed a representative sample of 195 men in a small Canadian city. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 82 and most were Caucasian. Using a modified version of the SES, 27% of participants reported committing some type of sexual assault; 7.7% reported committing attempted or completed rape. Most sexual assaults occurred in young adulthood with a woman the man knew, including dates, wives, and friends.

One large noncollege study was conducted with a special population. Merrill et al. [2001] surveyed 7,850 male US navy recruits from three different locations. These men were on average 20 years of age and approximately two-thirds were Caucasian. Using a shortened form of the SES, approximately 11% of these men reported that they had committed an act that met standard legal definitions of rape.

Theoretical and Empirical Research Identifying Predictors of Sexual Assault Perpetration

Sexual assault perpetrators cannot be easily classified; instead they are a heterogeneous group with a wide range of past experiences, personality characteristics, and offense styles [Polaschek and Ward, 2002; Prentky and Knight, 1991; Seto and Barbaree, 1997]. Malamuth et al. [1995, 1991] have developed the confluence model, which emphasizes the importance of simultaneously considering multiple motives for committing sexual assault. This model describes two proximate, primary paths that can lead to sexual assault perpetration: hostile attitudes toward women and impersonal sex. Each of these paths independently predicts sexual assault perpetration, and they work together synergistically, such that men high on both dimensions also tend to commit the highest levels of sexual assault.

According to Malamuth et al. [1995], men who are high in hostile masculinity feel insecure and defensive in their relationships with women. Sexual aggression helps these men maintain feelings of control and superiority over women. Sex for these men is an act of power and dominance, rather than love. Numerous studies with sexual assault perpetrators have found that as compared to nonperpetrators, sexual assault perpetrators have greater hostility toward women, more traditional attitudes toward gender roles and sexual relationships, stronger sexual dominance motives, and are more accepting of using manipulative strategies in their relationships with women [Abbey et al., 1998; Johnson and Knight, 2000; Koss and Dinero, 1988; Malamuth et al., 1991, 1995; Murnen et al., 2002; Wheeler et al., 2002].

Men who are high on Malamuth’s second path of impersonal sex tend to prefer having many, casual sexual relationships rather than being in a committed relationship [Malamuth et al., 1991]. These men want to avoid intimacy, view obtaining sex from a woman as winning a game, and engage in sex for physical gratification rather than emotional closeness. Greater dating and sexual activity also provide more opportunities to commit sexual assault [Kanin, 1985]. Many researchers have reported that sexual assault perpetrators have consensual sex at an earlier age, have more dating and consensual sex partners, and have more positive attitudes about casual sexual relationships than nonperpetrators [Abbey et al., 1998; Koss and Dinero, 1988; Malamuth et al., 1995, 1991; Merrill et al., 2001; Senn et al., 2000].

According to Malamuth’s model, more distal, childhood and adolescent experiences also contribute to men’s likelihood of committing sexual assault through their impact on hostility toward women and impersonal sex [Malamuth et al., 1991, 1995]. Experiencing violence as a child encourages adolescent aggressiveness and delinquency, which in turn contributes to hostility toward women and early and frequent sexual activity according to the confluence model. Many researchers have found that childhood sexual and physical abuse predict sexual assault perpetration in incarcerated, college, and community samples [Barbaree and Marshall, 1991; Calhoun et al., 1997; Kosson et al., 1997; Merrill et al., 2001; Senn et al., 2000]. There are many explanations for the link between experiencing childhood sexual abuse and later perpetration, which include modeling the perpetrator’s violent tactics, identifying with the aggressor, developing hostile schemas about sexual relationships, attempting to regain a sense of power over one’s life, and restoring one’s sense of masculinity [Lisak, 1997; Romano and De Luca, 2000]. Delinquency has also been linked to sexual assault perpetration by many researchers [Ageton, 1983; Calhoun et al., 1997; Johnson and Knight, 2000]. In some cases, this may be a manifestation of general antisocial tendencies [Seto and Barbaree, 1997], whereas in other cases this may be at least partially due to norms among delinquent peer groups which encourage viewing sex as a conquest and condone violence against women [Ageton, 1983; Johnson and Knight, 2000].

Although Malamuth’s model includes a number of important predictors of sexual assault perpetration, there are other situational and proximal predictors that are useful to consider, including alcohol and peer norms. Approximately half of all sexual assaults are associated with alcohol consumption [Ageton, 1983; Muehlenhard and Linton, 1987; Seto and Barbaree, 1997; Tyler et al., 1998; Zawacki et al., 2003]. Men who are heavy drinkers or who report having alcohol problems are more likely than other men to have committed sexual assault [Abracen et al., 2000; Johnson and Knight, 2000; Merrill et al., 2001; Ullman et al., 1999]. When the perpetrator is intoxicated, the cognitive impairments induced by alcohol make it easier for him to focus on the short-term benefits of forced sex rather than on long-term negative consequences for himself and the victim [Abbey et al., 2004].

Explicit or implicit peer pressure to be sexually active may also encourage some men to force sex on unwilling dates [Boeringer et al., 1991; DeKeseredy and Kelly, 1995; Koss and Dinero, 1988]. For example, in a longitudinal study of adolescents, Ageton (1983) found that involvement with delinquent peers was the only predictor variable that discriminated between sexual assault perpetrators and nonperpetrators. In a college study, men who reported that members of their peer group perceived women as sexual objects were more likely than others to commit sexual assault [Koss and Dinero, 1988]. Most people share their friends’ values and want to please them [Fehr, 1996]. Sexual assault perpetrators are hypothesized to be particularly sensitive to their friends’ perceptions of their masculinity and sexual virility. In one prospective study, adolescent men who were part of peer groups that described women in derogatory terms were more likely than other men to later engage in dating violence as young adults [Capaldi et al., 2001]. Similarly, men who feel implicit pressure to have numerous stories of sexual conquest are likely to feel justified forcing sex [DeKeseredy and Kelly, 1995; Kanin, 1985].

Overview of the Study’s Goals and Hypotheses

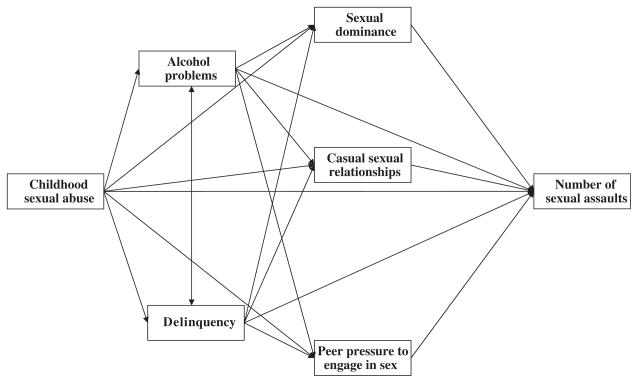

One important research question that emerges from this literature review concerns the extent to which the predictors of sexual assault perpetration in community samples are similar to those that have been found in college samples. Based on the literature reviewed above, we examined an expanded version of Malamuth’s confluence model [Malamuth et al., 1995, 1991]. As can be seen in Figure 1, childhood sexual abuse was hypothesized to be related to increased adolescent delinquency and alcohol problems, and all three of these variables were expected to contribute to sexual assault perpetration directly and indirectly, through their effects on other variables in the model. These different problem behaviors tend to co-occur [Lansford et al., 2003; Patterson, 1996; Seto and Barbaree, 1997]; thus we have hypothesized many links between these predictor variables.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

We selected one variable to assess each of Malamuth’s primary paths. Sexual dominance was used to represent the hostility toward women path because its focus on sex as a means of exerting power over women is at the core of this concept [Malamuth et al., 1995; Wheeler et al., 2002; Zurbriggen, 2000]. Positive attitudes toward casual sexual relationships were used to represent the impersonal sex path because its focus on sex as casual pleasure, rather than part of a committed relationship, is at the center of this concept [Kanin, 1985; Malamuth et al., 1991; Wheeler et al., 2002]. Additionally, peer pressure to engage in sexual relations was also hypothesized to be positively related to sexual assault perpetration [Capaldi et al., 2001; DeKeseredy and Kelly, 1995; Kanin, 1985; Koss and Dinero, 1988].

In addition to examining factors that put men at risk for committing sexual assault, we also considered empathy as a protective factor. Past research suggests that the ability to take the perspective of others and sympathize with their personal distress can reduce the impact of risk factors that encourage sexual assault perpetration [Covell and Scalora, 2002; Dean and Malamuth, 1997; Lisak, 1997; Wheeler et al., 2002]. Empathy is not shown in Figure 1 because it was treated as a moderator of the relationship between the risk measures and sexual assault perpetration. We hypothesized that empathy would moderate the effects of the variables most proximal to sexual assault. Men high in empathy were expected to be more likely than men low in empathy to commit low levels of sexual assault even if they experienced high levels of sexual dominance, positive attitudes about casual sex, and/or peer pressure to engage in sex.

Another goal was to add to the limited database on rates of sexual assault perpetration in ethnically diverse community samples and the effects of question phrasing and mode of interview on responses. One reason that few community studies of sexual assault perpetration have been conducted is concern about men’s willingness to admit committing potentially prosecutable crimes to a researcher. We used CASI methodology to minimize this concern. The questionnaire was programmed into a computer so that participants could read the questions to themselves and answer them without being concerned about an interviewer seeing or hearing their responses. We are not aware of this methodology being used with sexual assault perpetrators, although it has been used in several studies of sexual behavior and drug use and has been found to increase reports of potentially embarrassing and illegal activities [Lessler et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2002; Turner et al., 1998]. Thus, we anticipated that higher rates of sexual assault perpetration would be reported by men in this study as compared with men in past survey research.

METHOD

Participants

Interviews were conducted with 166 men. Three men were dropped from the data set because they did not answer most of the questions. Thus, the final sample consisted of 163 men. Fifty-four percent of participants (n = 88) were African American and 46% were Caucasian (n = 75). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 49, with a median age of 29. Ninety-five percent of participants had completed high school; 16% had completed college. The median household income was between $35,000 and $39,999, with 11% of participants earning less than $20,000 a year and 12% earning more than $80,000 a year. Participants worked in a wide range of occupations, with skilled labor (26%), service work (20%), and professional (17%) being the most common. Comparisons of this sample’s characteristics to the single male population in the metropolitan Detroit area suggest that it is fairly representative in terms of median income, but somewhat better educated (US Census, 2000). Individuals who agree to participate in lengthy surveys are typically more educated than the population as a whole [Fowler, 1988].

Procedure

Participants were contacted through random digit dialing in the Detroit metropolitan area. The largest ethnic groups in the Detroit metropolitan area are African American (26%) and Caucasian (70% [US Census, 2000]). Exchanges in communities with large numbers of African Americans were over-sampled and only African American and Caucasian participants were recruited so that similarities and differences in predictors of perpetration could be examined for men from these two ethnic groups. The Center for Urban Studies at Wayne State University was responsible for screening and interviewing under the supervision of the first and fourth authors. Potential participants were told that the study focused on the dating experiences of adults, including both good and bad experiences. The topic of sexual assault was not mentioned on the telephone. Potential participants were also told that the interview would take approximately 90 min and that they would be paid $50. In order to maximize the likelihood that participants would be able to describe recent dating experiences, they were required to be between the ages of 18 and 49, to currently be single, and to have dated someone of the opposite sex within the past year. Among individuals who met all the eligibility criteria, 81.7% agreed to participate in the study.

Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes, local libraries, coffee shops, and at the university, based on participants’ preference. The consent form described the scope of the study’s questions in more detail than the telephone interviewer had. It specifically noted that questions about unwanted sexual activity during childhood and adulthood were included. Participants’ right to skip questions for any reason and to stop the interview at any time were also noted. To protect participants’ confidentiality, no identifying information was included in the computer file and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the Department of Health and Human Services protecting the data from subpoena (questions about child abuse perpetration or communicable diseases which must be reported were not included). This was also explained in the consent form to enhance participants’ willingness to disclose sexual assault perpetration experiences. The consent form included telephone numbers for several counseling centers in case participants wanted to talk to someone after completing the interview. At the end of the interview, several questions assessed how participants felt at that point. On 5-point scales with response options that ranged from not at all (1) to very (5), participants’ mean levels of anger (M = 1.46, SD = .84), sadness (M = 1.53, SD = .84), and embarrassment (M = 1.42, SD = .83) were very low.

Interviewers were extensively trained in standard interview procedures, obtaining informed consent, collecting sensitive information, vocabulary that may be unfamiliar to participants, and the use of laptop computers. The interviewers’ primary responsibilities were to explain the consent form to participants, familiarize participants with the use of a laptop computer by guiding them through a series of sample questions, and to answer any questions that arose during the interview. Male interviewers were used, and participants and interviewers were matched on ethnicity. The interviewer encouraged participants to ask questions if they were confused at any point during the survey. Interviewers positioned themselves far enough away that they could not see the computer screen, but could ensure that the participant was working on the questionnaire.

Measures

Sexual assault perpetration

Sexual assault perpetration was measured by a modified 17-item version of the SES. The SES includes behaviorally specific descriptions of incidents that have occurred since the age of 14 [Koss et al., 1987]. The additional seven items were included to give more specific examples of some types of incidents than were included in the original measure, following suggestions made by other researchers for updating this instrument [Koss, personal communication, 2000; Kosson et al., 1997]. Additional verbal coercion items included a question about pressure induced through swearing, getting angry, or threatening to end the relationship as well as questions about verbally coerced oral and anal sex. Additional rape items assessed sexual intercourse when the woman was incapacitated and unable to give consent and a final question that specifically used the word “rape” [Abbey et al., 1998; Koss and Oros, 1982]. Each question was answered on a 6-point scale with options that ranged from never (0) to five or more times (6). The SES has been used extensively and exhibits good internal consistency and test–retest reliability. The Cronbach coefficient α for the current study was .88.

Childhood sexual abuse

A modified version of Wyatt’s [1985] measure of childhood sexual abuse was used to assess victimization before the age of 14. Eleven behaviorally specific yes/no questions were asked about experiences ranging from exhibitionism to sexual intercourse. Responses were then categorized to place participants in the group representing the worst childhood sexual abuse event they had reported (0 = no abuse, 1 = abuse without physical contact, 2 = physical contact without penetration, or 3 = attempted/completed penetration). Cronbach’s coefficient α was .93.

Alcohol problems

Lifetime alcohol problems were assessed with 13 yes/no questions that have been used in national studies of alcohol consumption and abuse [Hilton, 1987]. The items addressed alcohol abuse and dependence issues such as not being able to stop drinking and symptoms of withdrawal. Sample items include “I sometimes kept on drinking after I promised myself not to” and “I have needed a drink so badly that I couldn’t think of anything else.” Scores could range from zero to 13 and Cronbach’s coefficient α was .88.

Delinquency

Childhood and adolescent delinquency was assessed using a scale based on measures developed by Jessor et al. [1968] and Tremblay et al. [1995]. Participants were asked to indicate the number of times they had engaged in 14 delinquent behaviors before the age of 18. Sample items include getting into fights, stealing from a store, and trespassing. Participants responded using a 6-point scale with options ranging from zero times (0) to more than five times (6). Cronbach’s coefficient α was .85.

Sexual dominance

Nelson’s [1979] Sexual Dominance scale has been used by other researchers to represent hostility toward women and has shown strong internal consistency reliability as well as convergent validity (Malamuth et al., 1995; Wheeler et al., 2002). Sample items include “I have sexual relations because I like the feeling that I have someone in my grasp” and “I have sexual relations because I like the feeling of having another person submit to me.” Responses were made on 4-point Likert-type scales with options that ranged from not important at all (1) to very important (4). Cronbach’s α for this eight-item measure was .90.

Positive attitudes about casual sexual relationships

Participants’ attitudes toward casual sexual relationships were evaluated with four items from a longer measure developed by Hendrick and Hendrick [1987]. Sample items include “Sex without love is ok” and “I enjoy ‘casual’ sex with different female partners.” Responses were made on 7-point Likert scales with options that ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Cronbach’s coefficient α was .76.

Peer pressure to engage in sexual relations

The amount of perceived peer pressure to have sexual experiences was assessed with two items developed by the research team based on past research [Kanin, 1967b, 1985]. Participants were asked about pressure from friends to have sex with many different women and to tell stories about sexual experiences. These two items were rated on 7-point Likert-type scales with responses ranging from not at all (1) to very much (7). Cronbach’s coefficient α was .82.

Empathy

Empathy was measured with the Perspective taking and Empathic concern subscales from the Davis Empathy scale [Davis, 1980]. These two subscales were highly correlated and combined into a single 14-item measure. Sample items include “When I see someone being taken advantage of, I feel kind of protective towards them” and “Other people’s misfortunes do not usually disturb me a great deal.” (reversed). Responses were made on 5-point Likert-type scales with response options ranging from does not describe me well (1) to describes me well (5). Cronbach’s coefficient α was .84.

RESULTS

Self-Reported Rates of Sexual Assault Perpetration

Sixty-four percent of participants reported that they had perpetrated some form of sexual assault since the age of 14. Fifteen percent (n = 24) of the sample indicated that forced contact was the most serious type of sexual assault they had committed, for 24.5% (n = 40) verbally coerced sexual intercourse was the most serious type of sexual assault they had committed, and for 24.5% (n = 40) attempted or completed rape was the most serious type of sexual assault they had committed. Sixty percent (n = 62) of the men who reported that they committed sexual assault also acknowledged that they had committed more than one (mdn = 3). There were no significant differences in the percent of men who committed forced sexual contact, verbal coercion, or rape based on ethnicity, χ2 (3, N = 163) = 3.91, P = .27.

For the primary data analyses described below, we calculated the total number of sexual assaults that participants reported committing. Responses ranged from 0 to 80. The distribution was skewed and kurtoic; thus it was transformed using a base 10 log transformation [Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001]. Although the severity of the worst sexual assault committed measure described above has intuitive appeal, the limited range of response categories makes it less optimal for path analyses than the total number of assaults measure [Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001]. Additionally, severity of worst sexual assault committed and total number of sexual assaults committed were strongly, positively correlated, r = .76, P<.001.

Bivariate Analyses

Table I provides the correlations between the variables included in the path analyses, as well as their means and standard deviations. As can be seen from the table, all of the potential predictor variables were significantly correlated with the number of sexual assaults that participants had perpetrated. Many of the predictor variables were moderately correlated with each other. The strongest relationships were between sexual dominance and delinquency and sexual dominance and alcohol problems. The pattern of correlations was highly similar for African American and Caucasian men. The only significant difference between correlations was for the relationship between empathy and delinquency. The correlation between these variables was −.41 for Caucasian men and .05 for African American men (t = 3.03, P<.01). Given the many similarities, ethnic differences were not pursued in the path analyses.

TABLE I.

Means, Standard Deviations and Intercorrelations for Variables Included in Path Analysis (N= 163)

| Predictor variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Number of sexual assaults | — | .17* | .23* | .21** | .24** | .29** | .26** | 3.31** | .56 | .51 |

| 2. Childhood sexual abuse | — | — | .26** | .15 | .29** | .07 | .12 | .14 | 2.06 | 1.24 |

| 3. Alcohol problems | — | — | — | .24** | .31** | .14 | .16* | 3.13 | 3.28 | 2.27 |

| 4. Delinquency | — | — | — | — | .37** | .09 | .26** | 3.14 | 1.65 | .43 |

| 5. Sexual dominance | — | — | — | — | — | .26** | .22** | 3.04 | 1.96 | .74 |

| 6. Casual sexual relationships | — | — | — | — | — | — | .14 | 3.08 | 4.33 | 1.49 |

| 7. Peer pressure to engage in sex | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | .02 | 2.36 | 1.56 |

| 8. Empathy | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3.51 | .65 |

Note: Number of sexual assaults was transformed using a base 10 log transformation.

P<.05, two-tailed;

P<.01, two-tailed.

Examination of Conceptual Model through Path Analyses

The model presented in Figure 1 was examined through path analysis. Although path analysis can be conducted through a series of regression analyses, we used Lisrel 8.30 [Joreskog and Sorbom, 1999] because it provides fit indices that can be used to evaluate the model. Maximum likelihood estimation was used because it performs well with smaller samples [Hoyle, 1995] and moderately nonnormal data [Bollen, 1989]. The fit of the model was examined using a variety of standard measures including χ2, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), nonnormed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and normed fit index (NFI) [Bentler, 1990; Bentler and Bonett, 1980; Bollen, 1989; Browne and Cudeck, 1993]. Typically NFI, NNFI and CFI values greater than .90 and RMSEA values in the range of .00–.08 are interpreted as good fit.

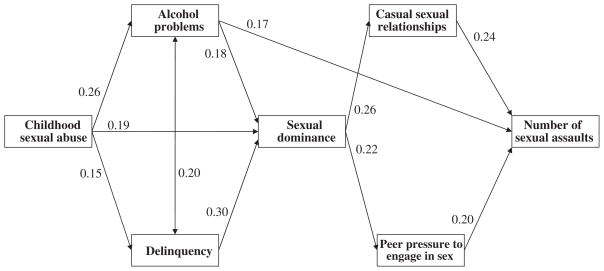

The conceptual model did not fit the data particularly well, χ2(4, N = 163) = 12.62, P<.01, RMSEA = .115, NFI = .902, NNFI = .586, CFI = .921. Several of the proposed paths were nonsignificant and modification indices suggested several paths that were not originally considered. Modification indices suggested that paths between sexual dominance and casual sexual relationships and between sexual dominance and peer pressure to engage in sex would improve the model’s fit. Figure 2 presents the revised model. Like Figure 1, the revised model includes a set of more distal predictors and a set of more proximal predictors, allowing for the effects of childhood sexual abuse, alcohol problems, and delinquency to be mediated by other variables. The major difference between the two models is in the placement and role of sexual dominance. We had predicted that sexual dominance was one of three proximal variables that were directly related to sexual assault perpetration. Instead, sexual dominance only had indirect effects on sexual assault perpetration that were mediated through its links to attitudes about casual sexual relationships and peer pressure to engage in sex.

Fig. 2.

Final model. Note that loadings are standardized. All significant paths are shown at the P<.05 level.

Furthermore, each of the more distal variables was predicted to have direct effects on several other variables in the model, including sexual assault perpetration. Instead, with just one exception, they were all significantly related only to sexual dominance. Thus, as can be seen in Figure 2, sexual dominance serves as a linchpin, with most of the effects of childhood sexual abuse, alcohol problems, and delinquency being funneled through it. The one exception is that alcohol problems also had a significant direct effect on the number of sexual assaults perpetrated. The model presented in Figure 2 fit the data reasonably well, χ2(10, N = 163) = 13.02, P>.22, RMSEA = .043, NFI = .890, NNFI = .930, CFI = .970. Although only alcohol problems, attitudes about casual sexual relationships, and peer pressure to engage in sex were directly linked to the number of sexual assaults perpetrated, the other variables in the model had low to moderate indirect effects. The total amount of variance explained in the number of sexual assaults committed was 14.1%.

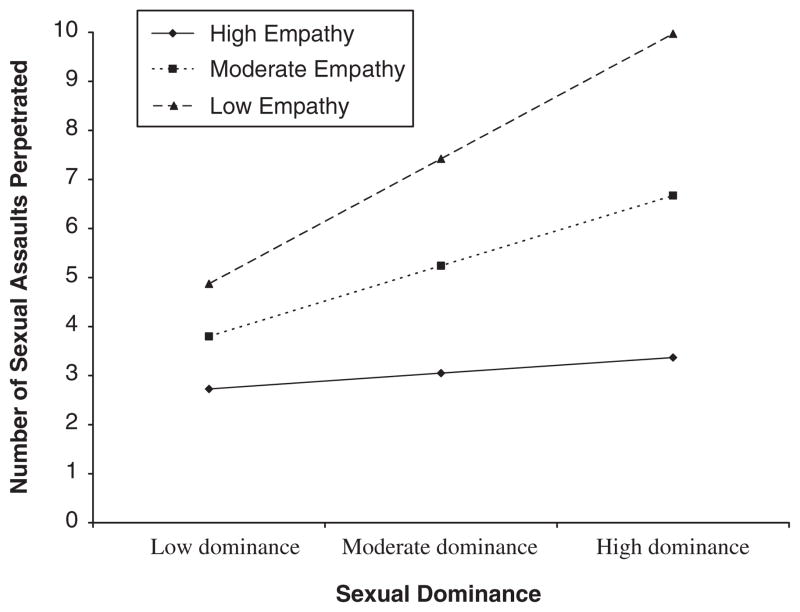

Examination of Buffering Effects of Empathy Through Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses

Path analysis is not well suited to examining interaction effects, particularly with small samples and limited degrees of freedom; thus hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the hypothesis that empathy buffered the effects of other variables on sexual assault perpetration [Aiken and West, 1991]. In preliminary hierarchical regression analyses, ethnicity did not have significant main or interaction effects; thus it was eliminated from the analyses. Three parallel sets of analyses were conducted. The first step included the main effects of empathy and either sexual dominance, casual attitudes toward sex, or peer pressure on sexual assault perpetration. The second step added the centered interaction term. The interaction term was significant only in the regression that included sexual dominance, F(3,159) = 11.60, P<.001, explaining 2.9% additional variance. Figure 3 graphically depicts this finding. Men with high levels of empathy committed relatively low levels of sexual assault, regardless of their level of sexual dominance (slope not significantly different from zero, t = .47, P>.64). In contrast, men with low levels of empathy committed increasing numbers of sexual assaults as their level of sexual dominance increased (t = 4.06, P<.001). Men with moderate levels of empathy fell between the other two groups, with a more gradual rate of increase than men low in empathy (t = 3.16, P<.01).

Fig. 3.

Buffering effects of empathy on the relationship between sexual dominance and number of sexual assaults perpetrated.

DISCUSSION

Self-Reported Rates of Sexual Assault Perpetration

African American and Caucasian men in this community sample acknowledged committing acts of verbally and physically forced sex at extremely high rates. Almost a quarter of the sample had committed an act since the age of 14 that seemed to meet standard legal definitions of attempted or completed rape. An additional 39% had verbally coerced intercourse or forced nonpenetrative sexual activities on women. Self-reported perpetration rates were comparable for African American and Caucasian men recruited through random digit dialing in a large metropolitan area. As noted in the introduction, depending on the questions asked and sample used, past college and community studies have found rates of rape ranging from about 7% to 15% and rates of other types of sexual assault ranging from about 16% to 61%. This broad range of past sexual assault perpetration prevalence estimates demonstrates that the questions asked and samples selected have a large impact on the prevalence rates obtained. Although there have been debates in the literature regarding how to label some of these acts [Koss, 1993], men who said yes to one of these questions acknowledged that they used some type of verbal or physical pressure to obtain some type of sex from an unwilling woman. Regardless of whether all these acts would constitute criminal behavior in most jurisdictions, they all reflect a callous disregard of women and willingness to treat them as sexual objects.

There are several possible explanations for the high rates of sexual assault perpetration reported in this study. Following the advice of the original author of the SES and others [Koss, personal communication, 2000; Kosson et al., 1997], we updated the measure, adding several items that specifically referred to having sex with a woman when she was unable to give consent, using implicit threats to obtain sex, and verbally coercing anal and oral sex. Reformulating perpetration groups using only the original SES items produced a prevalence rate of 20% rapists (as compared with 24.5% with the revised measure), 12% verbal coercers (as compared with 24.5% with the revised measure), and 26% forced contacters (as compared with 15% with the revised measure). Thus, the additional items identified some rapists not identified with the original measure and moved some men from the contact to verbal coercion group. The questions we added that asked about the woman being unable to consent, about verbally coerced sex acts, and about verbally coerced intercourse through implicit pressure identified perpetrators who had not said yes to any of the items in the original SES. These additional questions may have reminded some men of acts that they did not recall when reading the other questions. The alcohol item in the original SES focuses on the man intentionally getting the woman drunk, whereas our added item includes situations in which a man takes advantage of a woman who is incapacitated and unable to consent. Although laws vary across jurisdictions and a few require that the intoxicant was administered without the consent of the victim, rape definitions typically include having sex with someone unable to give consent regardless of whether impairment due to intoxication was voluntary [Kramer, 1994]. Only a few men labeled what they did as rape (n = 5) and all of these men had said yes to one of the questions that asked about using physical force to obtain intercourse or sex acts. Thus, asking men specifically about rape does not identify additional perpetrators. This corresponds to past research with victims and perpetrators, which indicates that few label these events as rape, perhaps because they do not fit the prototypic rape involving a sudden physical attack by a stranger [Falk, 1998; Layman et al., 1996].

Even the 20% rape rate found using the original SES items is higher than that found in other community and college studies, which also often modify the SES by adding items. Thus, it is likely that the CASI methodology made men more comfortable acknowledging past perpetrations. Turner et al. [1998] randomly assigned adolescent men to answer questions about sexual behavior and drug use with a CASI interview or a self-administered paper and pencil questionnaire. For most behaviors, the interviewing mode did not matter. However, for the most socially disapproved of behaviors, which included having sex with men and injection drug use, reported prevalence rates were much higher among the CASI group. This finding suggests that men were more comfortable acknowledging past sexual assault perpetration in this study than in past sexual assault research with college and community samples that used self-administered questionnaires. Research is needed that randomly assigns men to different forms of questionnaire administration and to different versions of the sexual assault measure in order to systematically address questions about what survey methodology enhancements will maximize men’s reports of past sexual assault perpetration.

Cross-Sectional Predictors of Sexual Assault Perpetration

Overall, this study’s findings replicate and extend past research using the confluence model and demonstrate that there are similarities in the predictors of sexual assault perpetration in community and college samples. Surprisingly, in multivariate analyses only alcohol problems, attitudes about casual sex, and peer pressure were directly related to the number of sexual assaults committed. The more alcohol problems these men experienced, the more positively they felt about engaging in casual sexual relationships with women, and the more they felt pressured by their friends to have sex with many different women, the more sexual assaults they reported having perpetrated. Childhood sexual abuse, alcohol problems, and delinquency were all positively related to sexual dominance, which in turn was positively related to attitudes about casual sex and peer pressure. Although these findings were cross-sectional, they suggest a chain of events in which men who experience childhood sexual abuse learn to view sex as a venue for gaining and displaying power over others. Heavy drinking problems and engaging in adolescent delinquency also encourage viewing sex as a source of power rather than emotional intimacy. This focus on sexual dominance encourages having multiple casual relationships and being comfortable using verbal and physical strategies to force sex on unwilling dating partners.

The primary difference between these findings and those of Malamuth and colleagues is in the relative role played by the two paths. In Malamuth and colleagues’ empirical tests of the confluence model [Malamuth et al., 1995, 1991], the hostile masculinity and impersonal sex paths both had direct effects on sexual assault perpetration, although in one study the effects of hostile masculinity were partially mediated by impersonal sex [Malamuth et al., 1995]. There are several possible explanations for these differences. In the study reported in this paper, hostile masculinity and impersonal sex were each assessed with one measure. Although these were multi-item scales with good internal consistency and reliability, other studies have included multiple indicators [Johnson and Knight, 2000; Malamuth et al., 1991; Wheeler et al., 2002] and it is possible that including a broader range of measures with a larger sample would have produced a somewhat different pattern of relationships. Additionally, most past research was conducted with college samples [Malamuth et al., 1991; Wheeler et al., 2002], and it is possible that sexual dominance plays a unique role in the sexual assaults of men in community samples. For heterosexual men who remain single into mid-adulthood, their desire to maintain dominance in sexual relationships may be a pivotal factor in their decision to use forced sex.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths and limitations. Although random digit dialing was used to generate the sample, the goal was not to obtain a completely representative sample of this large metropolitan area. Participants were African American and Caucasian adult men between the ages of 18 and 49 who were currently unmarried and had dated a woman in the previous year. This sampling strategy created a sample that is in many ways comparable to that used in college studies of sexual assault perpetration, although participants were somewhat older and employed. Most sexual assaults occur among individuals who know each other, often in a dating relationship; thus the sampling strategy allowed the most common types of sexual assault to be examined [Koss et al., 1987; Tjaden and Thoennes, 1998]. The parameters of marital sexual assault are likely to be very different from other types of sexual assault due to the long-term nature of the relationship [Tjaden and Thoennes, 2000]; thus it is important to also conduct sexual assault research among married and cohabitating couples. The pattern of relationships between the predictors and sexual assault did not significantly differ for African American and Caucasian men, suggesting that the etiology of sexual assault is similar across ethnic groups. Few studies have included adequate numbers of ethnic minority group members to conduct subgroup analyses, and more research is needed to confirm this study’s findings.

Time constraints precluded the possibility of including every variable that has been considered as a predictor of sexual assault perpetration. Measures from the domains of individual difference characteristics, attitudes, and past experiences were included; however, some important concepts such as psychopathy, the experience of physical abuse in childhood, arousal to deviant stimuli, and the capacity for intimacy were not assessed in this study. The moderate amount of variance explained in perpetration supports the need to include additional predictors in future studies.

The study’s cross-sectional design does not allow causality to be established. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the temporal ordering of these concepts. For example, Covell and Scalora [2002] suggest that the relationship between low empathy and sexual assault perpetration begins with poor parental attachment and abuse in childhood, which contribute to the development of poor interpersonal skills and impulse control. Although the pattern of results found in this study supports this hypothesis, it needs to be examined in prospective research that follows children into adulthood. Longitudinal studies would also allow examination of the trajectories of adolescents who commit forced contact or verbal coercion to determine if they escalate into more severe forms of sexual violence, and if so, what variables predict this escalation. Because nonassaulters were included in all analyses, the role of alcohol within the assault could not be addressed in this paper. The measure of drinking problems used here may be a proxy for heavy drinking at the time of the sexual assault. In a recent study that focused on 113 college men who acknowledged committing sexual assault, the quantity of alcohol they consumed during the assault was linearly related to their aggressiveness and curvilinearly related to the severity of the assault (Abbey et al., 2003). Although at moderate doses alcohol tends to increase aggressive behavior, at extremely high doses, cognitive and motor impairments are likely to reduce aggressive behavior [Giancola, 2002].

Implications

These findings suggest that treatment programs need to focus on perpetrators’ inability to establish close, caring relationships with women, their perceptions of sex as a domain in which they can exert power over women, their heavy alcohol consumption, and their friendships with other men that encourage these behaviors. The central, mediating role of sexual dominance highlights the importance of men’s beliefs about women and sexual relationships. Polaschek and Ward [2002] delineated five implicit theories about women that contribute to sexual assault perpetration: women are inherently different from men and unknowable, women exist to meet men’s sexual needs, men’s sex drive is uncontrollable, men are entitled to have their sexual needs met, and others cannot be trusted. They argued that more attention needs to be directed toward understanding perpetrators’ specific cognitive distortions if interventions are to be successful.

It is important to note that empathy reduced the likelihood of sexual assault among men who were extremely sexually dominant. This is similar to Dean and Malamuth’s [1997] finding that men who were high in nurturance were as likely as other men to fantasize about committing sexual assault, but were less likely to actually do so. Although interventions aimed at increasing perpetrators’ empathic skills have shown mixed success [Covell and Scalora, 2002; Geer et al., 2000; Schewe and O’Donohue, 1996], empathy is multidimensional, and here too it may be important that programs are tailored to perpetrators’ specific deficits.

The very high rates of self-reported perpetration in this community sample demonstrate the need for novel approaches to punishment. Koss et al. [2003] describe a restorative justice program that was developed in collaboration with the Pima County prosecutor’s office. In cases that involve a first offense against a date or acquaintance, the focus is on rehabilitation rather than prosecution. In a community conference that includes the victim, the offender, and a mediator, the perpetrator is asked to apologize and make appropriate reparations. In exchange, there is no criminal record of the offense. Programs such as this, which provide the perpetrator with the opportunity to reflect on how his actions hurt the woman, have the potential to deter future sexual assaults. Abbey and McAuslan [2004] found that college sexual assault perpetrators who expressed remorse during the initial assessment were less likely to commit additional sexual assaults during the 1-year follow-up interval.

Most perpetrators are never identified; thus general education and primary prevention programs are needed for young men. There are few prevention programs outside of college campuses. These findings suggest that sexual assault prevention programs need to be offered in community locations such as YMCAs, health clubs, community centers, and other places where young, single men congregate. Given the direct and indirect effects of alcohol problems on sexual assault perpetration, it is particularly important to intervene with heavy drinkers. Educational programs are also needed for boys beginning in elementary or middle school that model appropriate behavior and attitudes regarding relationships with women and sexual intimacy. It is important that schools create social climates in which derogation of girls and women is not accepted. In their recent meta-analysis of research linking hostile gender role beliefs and sexual dominance with sexual assault perpetration, Murnen et al. [2002] observed that Burt’s [1980] comments which stimulated much of this research are still true, “Only by promoting the idea of sex as a mutually undertaken, freely chosen, fully conscious interaction, is contradistinction to the too often held view that it is a battlefield in which each side tries to exploit the other” (p 229). Approximately 40 years after passage of the Civil Rights Act that prohibited discrimination against women, American social norms still encourage a sexual double standard and condone men’s aggression against women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants to the first author from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA11346 and AA11996).

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of college men’s perpetration of sexual assault. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Ross LT. Sexual assault perpetration by college men: The role of alcohol, misperception of sexual intent, and sexual beliefs and experiences. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1998;17:167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Clinton AM, Buck PO. Attitudinal, experiential, and situational predictors of sexual assault perpetration. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16:784–807. doi: 10.1177/088626001016008004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Clinton-Sherrod AM, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Buck PO. The relationship between the quantity of alcohol consumed and the severity of sexual assaults committed by college men. J Interpers Violence. 2003;18:813–833. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggr Violent Behav. 2004;9:271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abracen J, Looman J, Anderson D. Alcohol and drug abuse in sexual and nonsexual violent offenders. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat. 2000;12:263–274. doi: 10.1177/107906320001200403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ageton SS. Sexual Assault Among Adolescents. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaree HE, Marshall WL. The role of male sexual arousal in rape: Six models. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:621–630. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeringer SB, Shehan CL, Akers RL. Social contexts and social learning in sexual coercion and aggression: Assessing the contribution of fraternity membership. Fam Relat. 1991;40:58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Burt MR. Cultural myths and supports for rape. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;48:217–230. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.38.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun KC, Bernat JA, Clum GA, Frame CL. Sexual coercion and attraction to sexual aggression in a community sample of young men. J Interpers Violence. 1997;12:392–406. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Dishion TJ, Stoolmiller M, Yoerger K. Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Dev Psychol. 2001;37:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell CN, Scalora MJ. Empathic deficits in sexual offenders: An integration of affective, social, and cognitive constructs. Aggr Violent Behav. 2002;7:251–270. [Google Scholar]

- Craig ME, Kalichman SC, Folingstad DR. Verbal coercive sexual behavior among college students. Arch Sex Behav. 1989;18:421–434. doi: 10.1007/BF01541973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Docum Psychol. 1980;10:85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Dean KD, Malamuth NM. Characteristics of men who aggress sexually and of men who imagine aggressing: Risk and moderating variables. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:449–455. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.2.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy WS, Kelly K. Sexual abuse in Canadian university and college dating relationships: The contribution of male peer support. J Fam Violence. 1995;10:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Falk PJ. Rape by fraud and rape by coercion. Brooklyn Law Rev. 1998;64:39–178. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Uniform Crime Reports for the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr B. Friendship Processes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler FJ., Jr . Survey Research Methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. revised edition. [Google Scholar]

- Geer JH, Estupinan LA, Manguno-Mire GM. Empathy, social skills, and other relevant cognitive processes in rapists and child molesters. Aggr Violent Behav. 2000;5:99–126. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Alcohol-related aggression during the college years: Theories, risk factors, and policy implications. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl 14):129–139. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick S, Hendrick C. Multidimensionality of sexual attitudes. J Sex Res. 1987;23:502–526. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton ME. Demographic characteristics and the frequency of heavy drinking as predictors of self-reported drinking problems. Br J Addict. 1987;82:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Graves TD, Hanson RC. Society, Personality, and Deviant Behavior: A Study of a Tri-Ethnic Community. Oxford, England: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GM, Knight RA. Developmental antecedents of sexual coercion in juvenile sexual offenders. Sex Abuse: J Res Treat. 2000;12:165–178. doi: 10.1177/107906320001200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8.30. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kanin EJ. An examination of sexual aggression as a response to sexual frustration. J Marriage Fam. 1967a;29:428–433. [Google Scholar]

- Kanin EJ. Reference groups and sex conduct norm violations. Sociol Quart. 1967b;8:495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Kanin EJ. Selected dyadic aspects of male sex aggression. J Sex Res. 1969;5:12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kanin EJ. Date rapists: Differential sexual socialization and relative deprivation. Arch Sex Behav. 1985;14:219–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01542105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. Detecting the scope of rape. J Interpers Violence. 1993;8:198–222. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Dinero TE. Predictors of sexual aggression among a national sample of male college students. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1988;528:133–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb50856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. The sexual experiences survey. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Bachar K, Hopkins Restorative justice for sexual violence: Repairing victims, building community, and holding offenders accountable. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;989:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosson DS, Kelly JC, White JW. Psychopathy-related traits predict self-reported sexual aggression among college men. J Interpers Violence. 1997;12:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer KM. Rule by myth: The social and legal dynamics governing alcohol-related acquaintance rapes. Stanford Law Rev. 1994;47:115–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Rabiner DL, Miller-Johnson S, Golonka MM, Hendren J. Developmental model of aggression. In: Coccaro EF, editor. Aggression: Psychiatric Assessment and Treatment. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003. pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Layman MJ, Gidycz CA, Lynn SJ. Unacknowledged versus acknowledged rape victims: Situational factors and posttraumatic stress. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:124–131. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessler JT, Caspar RA, Penne MA, Barker PR. Developing computer assisted interviewing (CAI) for the national household survey on drug abuse. J Drug Issues. 2000;30:9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D. Male gender socialization and the perpetration of sexual abuse. In: Levant RF, Brooks GR, editors. Men and Sex: New Psychological Perspectives. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 156–177. [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, Tanaka JS. Characteristics of aggressors against women: Testing a model using a national sample of college students. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Linz D, Heavey CL, Barnes G, Acker M. Using the confluence model of sexual aggression to predict men’s conflict with women: A ten-year follow-up study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:353–369. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill LL, Thomsen CJ, Gold SR, Milner JS. Childhood abuse and premilitary sexual assault in male navy recruits. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:252–261. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CS, Granoff BJ. Date and acquaintance rape among a sample of college students. Soc Work. 1992;37:504–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Linton MA. Date rape and sexual aggression in dating situations: Incidence and risk factors. J Consult Psychol. 1987;34:186–196. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Wright C, Kaluzny G. If “boys will be boys,” then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles. 2002;46:359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PA. Personality, sexual function, and sexual behavior: An experiment in methodology (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Florida, 1979) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1979;39:6134. [Google Scholar]

- Newman JC, Des Jarlais DC, Turner CF, Gribble J, Cooley P, Paone C. The differential effects of face-to-face and computer interview modes. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:294–297. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Some characteristics of a developmental theory for early-onset delinquency. In: Lenzenwegar MF, Haugaard JJ, editors. Frontiers of Developmental Psychopathology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 81–124. [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek DLL, Ward T. The implicit theories of potential rapists: What our questionnaires tell us. Aggr Violent Behav. 2002;7:385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Prentky RA, Knight RA. Identifying critical dimensions for discriminating among rapists. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:643–661. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport K, Burkhart BR. Personality and attitudinal characteristics of sexually coercive college males. J Abnorm Psychol. 1984;93:216–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, De Luca RV. Male sexual abuse: A review of effects, abuse characteristics, and links with later psychological functioning. Aggr Violent Behav. 2000;6:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schewe PA, O’Donohue W. Rape prevention with high-risk males: Short-term outcomes of two interventions. Arch Sex Behav. 1996;25:455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02437542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn CY, Desmarais S, Verberg N, Wood E. Predicting coercive sexual behavior across the lifespan in a random sample of Canadian men. J Soc Pers Relat. 2000;17:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Seto MC, Barbaree HE. Sexual aggression as antisocial behavior: A developmental model. In: Stoff DM, Breiling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of Antisocial Behavior. New York: Wiley; 1997. pp. 524–533. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4. New York: Harper Collins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, Incidence, and Consequences of Violence Against Women: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 1998. NCJ 172837. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2000. NCJ 181867. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay R, Pagani-Kurtz L, Masse L, Vitaro F, Pihl RO. A bimodal prevention intervention for disruptive kindergarten boys: Its impact through mid-adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;634:560–568. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. Coercive sexual strategies. Violence Victims. 1998;13:47–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual aggression in a national sample of college men. Psychol Women Quart. 1999;23:673–689. [Google Scholar]

- US Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2000. Washington, DC: US Bureau of the Census; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler JG, George WH, Dahl BJ. Sexually aggressive college males: Empathy as a moderator in the “Confluence Model” of sexual aggression. Pers Individ Differ. 2002;33:759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GW. The sexual abuse of Afro-American and White American women in childhood. Child Abuse Neglect. 1985;9:507–519. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki T, Abbey A, Buck PO, McAuslan P, Clinton-Sherrod AM. Perpetrators of alcohol-involved sexual assaults: How do they differ from other sexual assault perpetrators and nonperpetrators? Aggr Behav. 2003;29:366–380. doi: 10.1002/ab.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen EL. Social motives and cognitive power-sex associations: Predictors of aggressive sexual behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:559–581. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]