Abstract

Background

The authors evaluated adherence of state Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) guidelines to recommended best oral health practices for infants and toddlers.

Methods

The authors obtained state EPSDT guidelines via the Internet or from the Medicaid-CHIP State Dental Association in Washington. The authors identified best oral health practices through the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), Chicago. They evaluated each EPSDT dental periodicity schedule with regard to the timing and content of seven key oral health domains for infants and toddlers.

Results

Thirty-two states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) had EPSDT dental periodicity schedules. With the exception of the dentist referral domain, 29 states (88 percent) adhered to the content and timing of best oral health practices, as established by the AAPD guideline. For the dentist referral domain, 31 of the 32 states and D.C. (94 percent) required referral of children to a dentist, but only 11 states (33 percent adhered to best oral health practices by requiring referral by age 1 year.

Conclusions

With the exception of the timing of the first dentist referral, there was high adherence to best oral health practices for infants and toddlers among states with separate EPSDT dental periodicity schedules.

Practical Implications

States with low adherence to best oral health practices, especially regarding the dental visit by age 1 year can strengthen the oral health content of their EPSDT schedules by complying with the AAPD recommendations.

Keywords: Dental care for children, state health plans, public policy, practice guidelines, best oral health practices

Medicaid is the largest public health insurance program for low-income Americans.1 It finances health care coverage for almost 60 million people, one-third of whom are children.1 In 1967, Congress enacted the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) service within Medicaid.2,3 EPSDT helps to ensure that children in low-income families who are covered by Medicaid have access to comprehensive and periodic evaluations to target health conditions and problems for which growing children are at risk.2-4 These conditions include dental disease.2 EPSDT is based on a model that recognizes that “developmental processes are vulnerable to untreated diseases, including oral diseases, making disease prevention, early identification of high-risk children, and timely interventions critical.”5 EPSDT serves approximately 30 million children in low-income families, a number expected to rise with increased Medicaid eligibility owing to the Affordable Care Act of 2010.1,6

EARLY AND PERIODIC SCREENING, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT DENTAL SERVICES

As a joint federal and state program, Medicaid is operated by states within broad federal requirements. States “can elect to cover a range of optional populations and services, thereby creating programs that differ substantially from state to state.”7 Although adult dental benefits are optional, all states are federally mandated under EPSDT to cover comprehensive dental services for children younger than 21 years.7 According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Baltimore, minimum EPSDT dental services include relief of pain and infections, restoration of teeth and maintenance of dental health. Although an oral screening may be part of a physical examination, it does not substitute for examination by means of direct referral to a dentist.8 States must provide any necessary health care service to a child covered by EPSDT even if the service is not available under the state's Medicaid plan to the rest of the Medicaid population.6,8

Dental periodicity schedule

Although state Medicaid programs are federally mandated to cover dental EPSDT benefits, states have some flexibility in determining the timing and regularity of these dental visits. State EPSDT programs must create a separate periodicity schedule for dental services by either consulting with recognized dental organizations, which, at a minimum, include a professional state dental association and pediatric dentists within the state, to recommend intervals that “meet reasonable standards of dental practice,” or adopting a “nationally recognized dental periodicity standard without substantial formal consultation.”8 In compliance with these two processes, each state's EPSDT program should require a direct dental referral for every child in accordance with the periodicity schedule developed by the state and at other intervals as deemed medically necessary.8

The rationale for providing early and comprehensive dental services to children enrolled in Medicaid is that dental caries is the single most common chronic disease among U.S. children, with the highest rates observed in economically disadvantaged and minority populations.7,9 Despite the fact that caries is highly preventable through early and sustained home care and regular professional preventive services, the results of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate visible decay in 30 percent of 2- to 5-year-old children living in poverty compared with 6 percent of children in families with the highest income levels.10 Dental care continues to be the most common unmet treatment need in children11 and for millions of American children without dental care, the consequences of severe and untreated dental disease are pain, infection, and destruction of surrounding tissues, delayed overall development, systemic health conditions, poor school attendance and performance, and social stigmatization.8 In addition, the potential consequences for the health care system are frequent visits to emergency departments, hospital admissions and costly treatment in hospital operating rooms.”8

Best oral health practices for infants and toddlers

Since 1991, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), Chicago, has published detailed recommendations for professional pediatric oral health services, including guidelines for the frequency and content of dental visits. These recommendations have been revised six times (in 1992, 2996, 2000, 2003, 2007 and 2009).12 According to the 2004 CMS report,8 the AAPD recommendations have been embraced by the Bright Futures consortium of 28 children's health organizations and are recognized by dental and public health groups, including the American Dental Association, Chicago, American Dental Hygienists’ Association, Chicago, and the American Public Health Association, Washington. They are the basis of the “Guide to Children's Dental Care in Medicaid” published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, and CMS.8 These recommendations are intended for health care professionals who treat children beginning at birth and include the content and timing of developmental assessments, clinical examinations and diagnostic tests. Because of the wide acceptance and endorsement of these recommendations, the AAPD guideline is the benchmark for professional guidelines pertaining to children's dental periodicity schedules.

According to Peters, EPSDT is a “cornerstone of early childhood preventive and treatment services in the nation's health care ‘safety net.’ ”4 This safety net, however, cannot be considered effective unless policies and guidelines are consistent with professional recommendations. There is evidence that state EPSDT dental periodicity schedules are not consistent with the AAPD's periodicity schedule.13 For example, for 25 years, the AAPD has endorsed the first dental visit by age 1 year. However, the EPSDT guidelines in three states (5.9 percent) call for the first dental visit by age 2 years, and another three states (5.9 percent) recommend the first dental visit by age 3 years, according to the State Synopsis Questionnaire issued by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors.14 To our knowledge, there has been no comprehensive review of the oral health content and accessibility of state ESPDT guidelines.

Thus, we initiated this investigation to evaluate the adherence of state EPSDT dental periodicity schedules to the AAPD professional guideline.12

METHODS

We identified state-level (and District of Columbia [D.C.]) EPSDT dental periodicity guidelines by using two approaches. In the first approach, we accessed guidelines online, which is testament to the wide availability of the guidelines to EPSDT staff members, health care practitioners and parents. One of us (J.M.H.) performed the Internet searches in January 2012 by using the following search terms: state dental periodicity, state oral health periodicity, state dental EPSDT, state EPSDT periodicity, state Medicaid manual, dental EPSDT, state division of medical assistance, and state recommendations for preventive pediatric oral health care. If EPSDT dental guidelines were not accessible to the public, our second approach was to obtain periodicity schedules through the Medicaid-CHIP State Dental Association (MSDA), Washington, via the AAPD's Pediatric Oral Health Research and Policy Center. One of us (J.S.) communicated with the executive director of the MSDA (Mary E. Foley, RDH, MPH, in person and written communication, March, September and November 2011) about states for which information was missing. The executive director, in turn, coordinated communication with these states.

In accordance with The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989, CMS requires each state to maintain a separate dental periodicity schedule within its Medicaid policy.8,15 Therefore, the study inclusion criterion was a stand-alone dental periodicity table in a state Medicaid document. We excluded dental EPSDT information from the study if the state's Medicaid policy did not include a separate dental periodicity table, the state did not specify adoption of a professional EPSDT policy with a separate dental periodicity table, or the dental periodicity table was not associated with a Medicaid document. We evaluated the periodicity schedules that met the inclusion criterion on the basis of the dental periodicity table, accompanying explanatory prose and associated Medicaid documents.

We identified the 2009 AAPD recommendations as the benchmark for professional guidelines pertaining to children's dental periodicity schedules.12 We selected, a priori, the following seven domains because of their documented importance in children's oral health and prominence in the 2009 AAPD guideline12:

clinical oral examination;

caries risk assessment;

prophylaxis and topical fluoride;

fluoride supplementation;

anticipatory guidance and counseling;

oral hygiene counseling;

referral to a dentist.

All seven domains pertain to children aged 6 months to 12 years according to the 2009 AAPD guideline.12 Therefore, all seven domains are recommended components of EPSDT dental services from infancy to early childhood (6 months to 4 years old). We evaluated each EPSDT dental periodicity schedule with regard to the timing and content for each of the seven domains. Although the AAPD schedule makes recommendations for children as young as 6 months, we evaluated recommendations regarding timing for children aged 12 months and older.

Guideline content

We considered content for the “caries risk assessment” domain to be sufficient if the term “risk assessment” was used or if the policy referred to a specific caries risk assessment tool. We considered content for the domain “prophylaxis and fluoride” to be sufficient if the policy specified both professional fluoride application and prophylaxis or fluoride application alone. We did not consider content to be sufficient for the domain “prophylaxis and fluoride” if a prophylaxis was specified without fluoride application. We considered content to be sufficient for the domain “anticipatory guidance and counseling” if the term “anticipatory guidance” was used or if the policy addressed all of the following four topics:

causes and progression of dental caries;

dietary counseling;

nonnutritive habits;

injury-prevention counseling.

If the policy recommended or encouraged referral of the child to a dentist at no later than age 1 year, we considered the content sufficient for the domain “referral to a dentist.” In addition, we considered the content to be sufficient if the policy included exceptions to the dental visit by age 1 year because of dentist workforce shortages.

RESULTS

Although all 50 states and D.C. had a dental component to their EPSDT guidelines, 33 of 51 (65 percent) maintained separate dental EPSDT periodicity schedules (Table 1) and 18 (35 percent) did not (Table 2). For states that did not adopt a separate dental EPSDT periodicity schedule, five incorporated dental information into their Medicaid policy from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), Elk Grove Village, Ill., periodicity schedule for medical screening, and one incorporated dental information from the Bright Futures periodicity schedule for medical screening. With the exception of Iowa, Nevada and Wyoming, the 32 states and D.C. with separate EPSDT dental periodicity schedules adopted the AAPD guideline in part or entirely. Conversely, none of the states without a separate EPSDT dental periodicity schedule adopted the AAPD guideline.

TABLE 1.

Oral health content of state Medicaid EPSDT* dental periodicity schedules (n = 33).

| STATE | DATE OF LATEST PLAN |

CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION DOMAIN |

CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT DOMAIN |

PROPHYLAXIS AND TOPICAL FLUORIDE DOMAIN |

FLUORIDE SUPPLEMENTATION DOMAIN |

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE/ COUNSELING DOMAIN |

ORAL HYGIENE COUNSELING DOMAIN |

REFERRAL TO A DENTIST DOMAIN |

TOTAL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | |||

| Alabama | 1/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Arizona | 10/1/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| California | 2/1/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Delaware | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 12 | |||

| District of Columbia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 | |

| Georgia | 4/1/2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Idaho‡ | 6/1/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Illinois | 7/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | 13 |

| Indiana | 3/1/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | 12 | |

| Iowa | 9/1/2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Kansas | 9/11/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | |

| Kentucky | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | 10 | |||

| Louisiana | 10/16/2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 12 | ||

| Maine¶ | 5/1/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Massachusetts | 7/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Minnesota | 10/1/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Mississippi | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 | |

| Nebraska | 8/15/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Nevada | 5/8/2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | 13 |

| New Jersey | 1/27/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 10 | |||

| North Carolina | 11/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| North Dakota# | 1/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | |

| Oklahoma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | § | ✓ | § | ✓ | 12 | |

| Oregon | 2/28/2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 13 | |

| Pennsylvania | 6/14/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Rhode Island | 5/1/2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 13 |

| Texas | 12/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Utah | 10/1/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Vermont | 7/29/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 14 |

| Virginia | 1/28/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| West Virginia** | 3/22/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||||

| Wisconsin | 11/1/2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Wyoming | 3/1/2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 7 | ||||||

| TOTAL | – †† | 33 | 33 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 32 | 11 | 31 | – |

EPSDT: State Dental Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment.

Age 3 years.

Idaho adopted the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) dental periodicity recommendations,12 according to the Medicaid-CHIP Dental Association (MSDA). However, the 2008 Medicaid State Plan states that EPSDT dental services will be performed as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) periodicity schedule.

Age 2 years.

Maine adopted the AAPD dental periodicity recommendations, according to MSDA. However, the Bright Futures/AAP Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health was adopted, according to the MaineCare Benefits Manual.

North Dakota adopted the AAPD dental periodicity recommendations, according to MSDA. However, the Bright Futures Well Child Periodicity Schedule was adopted, according to the North Dakota Medicaid Manual.

West Virginia's HealthCheck Provider Manual states that the HealthCheck periodicity schedule corresponds to the latest edition of Bright Futures. There is no statement of adoption of the AAPD dental periodicity schedule. However, the oral health section of the HealthCheck Provider Manual provides the link to the Web site of the AAPD periodicity article, which also is reproduced in the appendix.

Dash indicates not applicable.

TABLE 2.

Oral health content of Medicaid EPSDT* guidelines for states without dental periodicity schedules (n = 18).

| STATE | DATE OF LATEST PLAN |

CLINICAL ORAL EXAMINATION DOMAIN |

CARIES RISK ASSESSMENT DOMAIN |

PROPHYLAXIS AND TOPICAL FLUORIDE DOMAIN |

FLUORIDE SUPPLEMENTATION DOMAIN |

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE/ COUNSELING DOMAIN |

ORAL HYGIENE COUNSELING DOMAIN |

REFERRAL TO A DENTIST DOMAIN |

TOTAL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | Timing | Content | |||

| Alaska | 8/1/2003 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 4 | |||||||||

| Arkansas | 7/1/2007 | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 3 | ||||||||||

| Colorado | 7/1/2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||||

| Connecticut | 1/1/2007 | ‡ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ‡ | ✓ | 6 | ||||||

| Florida | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 7 | |||||||

| Hawaii | 10/1/2002 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 7 | ||||||

| Maryland | 3/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ‡ | ✓ | 13 |

| Michigan | 1/1/2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||||

| Missouri | 11/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||||||||

| Montana | 7/1/2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ||||||

| New Hampshire | 6/1/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||||||||

| New Mexico | 5/31/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 5 | ||||||||

| New York | 1/1/2005 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ||||

| Ohio | 7/1/2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 7 | ||||||

| South Carolina | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 8 | ||||||

| South Dakota | 10/25/2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | ||||||||||

| Tennessee | 11/1/2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 13 |

| Washington | 7/1/2006 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | † | ✓ | 6 | |||||||

| TOTAL | – § | 16 | 18 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 16 | – |

EPSDT: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment.

Age 3 years.

Age 2 years.

Dash indicates not applicable.

Overall, states with separate dental periodicity schedules (Table 1) adhered more closely to oral health best practices than did states with no separate dental periodicity schedules (Table 2). Two states—Maryland and Tennessee—enacted EPSDT policies that contained almost all of the key oral health domains, but they did not have a separate dental periodicity schedule (Table 2).

Among the 32 states and D.C. with separate dental EPSDT periodicity schedules, those that adhered to the timing and content criteria of all seven oral health domains were California, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah and Vermont (Table 1). Twenty-eight states and D.C. (88 percent) with separate dental periodicity schedules adhered to best oral health practices with respect to the content and timing of six oral health domains: clinical oral examination, caries risk assessment, prophylaxis and topical fluoride, fluoride supplementation, anticipatory guidance/counseling and oral hygiene counseling.

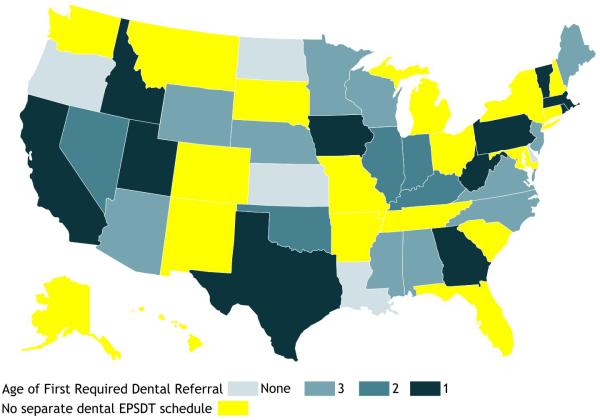

Although 31 (94 percent) of the 32 states and D.C. with dental periodicity schedules included a requirement for referral to a dentist in their schedules, only 11 (33 percent) adhered to the best oral health practices by recommending a referral by the child's first birthday (Table 1) (Figure). The following 14 states and D.C. adhered to the timing and content of all oral health domains except for the timing of a referral to a dentist: Alabama, Arizona, D.C., Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Virginia and Wisconsin (Table 1).

Figure.

Child's age at first required referral to a dentist, according to State Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) guidelines.

In accordance with best oral health practices, 11 states (Table 1) (Figure) required referral to a dentist by the time a child is age 1 year. Five states required a dentist referral by age 2 years, and 12 states required a referral by age 3 years. Five states did not address the timing of the dentist referral in their EPSDT dental periodicity schedules.

DISCUSSION

Medicaid programs provide many oral health services for children in low-income families who otherwise would not have access to dental care. We identified state EPSDT dental periodicity schedules because of their potential to influence the oral health of children enrolled in Medicaid. We found that only 32 states and D.C. had EPSDT oral health guidelines, but the majority of those that did included more than 85 percent of recommended best oral health practices in their guidelines. EPSDT dental periodicity guidelines vary greatly among the states, as does the accessibility of the guidelines.

Several states should be commended for their well-labeled and easily accessible EPSDT dental periodicity schedules. However, the overall process of obtaining these schedules was time-consuming and required extensive online searches. The difficulty we had in finding dental periodicity schedules in this study also would be experienced by EPSDT staff members, health care professionals and families of children enrolled in Medicaid. This may result in practitioners’ frustration, children's not receiving appropriate dental treatment covered by EPSDT, and refusal for reimbursement of EPSDT-covered dental services. Not only is it in the best interest of the public to have EPSDT dental periodicity schedules readily available through the Internet, it also improves compliance by health care professionals and EPSDT staff members with federal EPSDT requirements. According to CMS, “federal law also requires that states inform all families about EPSDT coverage.”8,16

EPSDT dental periodicity schedules for California, Delaware, D.C., Idaho, Maine, Mississippi and North Dakota were accessible only from the MSDA. For these states, we found that online EPSDT dental periodicity information was not updated, with the most recent policy or periodicity schedules not published online. For example, MSDA informed the AAPD that Idaho adopted the AAPD dental periodicity recommendations (Mary E. Foley, RDH, MPH, executive director, MSDA, personal communication, 2011). However, the most recent Idaho Medicaid Standard State Plan17 that is available to the public online stated that EPSDT dental services would be performed as recommended by the AAP periodicity schedule. Although the eight states above adopted recommended best practices in their EPSDT dental periodicity schedules, the inconsistency between actual and publicly available guidelines can send mixed messages to EPSDT staff members that can lead to improper implementation, thus affecting dental care.

Adopting multiple guidelines for EPSDT dental services may be the result of an assumption that professional periodicity guidelines from the AAP, Bright Futures and the AAPD are consistent, as well as the challenge of evaluating discrepancies in professional dental recommendations. However, not only are guidelines from each of these professional organizations different, they also are updated with current evidence at different rates and change across time.

One major difference between AAPD's best practices and other professional dental periodicity guidelines is the child's age at first referral to a dentist. Although current Bright Futures and the AAP recommendations encourage establishment of a dental home by age 1 year, outdated versions adopted by states for EPSDT dental periodicity schedules recommend the first dental visit by age 3 years. As mentioned earlier, the dental visit by age 1 year has been endorsed by the AAPD for 25 years. The rationale for the dental visit by age 1 year is that dental caries in American preschoolers is increasing.18 According to Tomar and Reeves,19 “the prevalence of dental caries in primary teeth of children aged 2 to 4 years increased from 18 percent in 1988-1994 to 24 percent in 1999-2004.” Prevention and treatment must occur sufficiently early enough before disease onset to effectively reverse this disease trend. An ongoing relationship with a dentist is optimal to introduce proper oral hygiene practices, a professional oral health risk assessment and treatment.

Age at dentist referral

The difficulty in differentiating between professional guidelines could explain why the age at dentist referral was the most divergent issue among states’ EPSDT dental periodicity schedules. More states required a referral by age 3 years than by age 1 year. Therefore, some recommendations in states’ periodicity schedules are not in agreement with the recommended best practices, as established by the AAPD.12 We found that this occurred most often in states that adopted EPSDT dental periodicity schedules on the basis of consultations with a professional organization.

AAPD guideline

By adopting the AAPD guideline exclusively as the EPSDT dental periodicity schedule, state Medicaid programs will avoid the confusion that occurs when adopting multiple guidelines, and they will be in compliance with The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 19898,15 by maintaining a separate dental periodicity schedule. Clear and consistent guidelines are essential to ensure timely and appropriate dental services for children, avoid practitioners’ frustration and properly reimburse practitioners for oral health services.

Limitations and future steps

We may have underestimated the oral health recommendations contained in state EPSDT dental periodicity guidelines owing to their lack of availability or accessibility to the public. Guideline accessibility is an important aspect of EPSDT services, and health care practitioners and families of children receiving Medicaid may not have sufficient time and resources to locate the EPSDT information. In addition, this study was limited to being a policy analysis. Policy is the basis for providing and financing dental services.20 It sets expectations for health care practitioners and families with children receiving Medicaid and is the basis of reimbursement for dental care. Therefore, reporting key policy items in the EPSDT dental periodicity schedules is the first step toward improving children's oral health. This study fills an important gap in the literature regarding the availability and content of state EPSDT guidelines on oral health. Investigators in future studies should evaluate the implementation and enforcement of EPSDT dental periodicity policy, its consistency with Medicaid reimbursement, and the effects of EPSDT dental periodicity policy on practice and oral health outcomes in children enrolled in Medicaid.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study show that only 32 states and D.C. (65 percent) had a separate EPSDT oral health guideline. Most of the states with EPSDT oral health guidelines included more than 85 percent of the recommended best oral health practices, which are based on the AAPD guideline.12 Conversely, none of the states without a separate EPSDT dental periodicity schedule adopted the AAPD guideline. The age at which children are first referred to a dentist was the most divergent issue among state periodicity schedules. More states required a dentist referral by age 3 years than did those requiring a referral by age 1 year, which is the age recommended in the AAPD guideline.12 The difficulty in differentiating between professional guidelines, such as outdated versions of the AAP and the current AAPD recommendations, might explain the variation in age at first referral to a dentist in EPSDT dental periodicity schedules.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant T32DE017245 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., and by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry Samuel D. Harris Research and Policy Fellowship.

Dr. Hom received a grant from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

ABBREVIATION KEY

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- AAPD

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry

- CHIP

Children's Health Insurance Program

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- D.C.

District of Columbia

- EPSDT

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment

- MSDA

Medicaid-CHIP State Dental Association

- NA

Not applicable

- NS

Not satisfied

Footnotes

Disclosure. None of the authors reported any disclosures.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jacqueline M. Hom, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill..

Dr. Jessica Y. Lee, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry, and Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill..

Ms. Janice Silverman, Pediatric Oral Health Research and Policy Center, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Chicago..

Dr. Paul S. Casamassimo, Department of Dentistry, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; Division of Pediatric Dentistry and Community Oral Health, College of Dentistry, The Ohio State University, Columbus; Pediatric Oral Health Research and Policy Center, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Chicago..

References

- 1.Kaiser Commission on Key Facts Medicaid and the Uninsured. [Dec. 10, 2012];Medicaid matters: Understanding Medicaid's role in our health care system. 2011 Mar; www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8165.pdf.

- 2.U.S. General Accounting Office . Medicaid: Stronger Efforts Needed to Ensure Children's Access to Health Screening Services. U.S. General Accounting Office; Washington: 2001. [Dec. 10, 2012]. GAO publication 01-749. www.gao.gov/new.items/d01749.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum S, Wise PH. Crossing the Medicaid-private insurance divide: the case of EPSDT. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(2):382–393. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters CP. EPSDT: Medicaid's critical but controversial benefits program for children. Issue Brief George Wash Univ Natl Health Policy Forum. 2006;(819):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouradian WE, Huebner CE, Ramos-Gomez F, Slavkin HC. Beyond access: the role of family and community in children's oral health. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(5):619–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Institute of Medicine, Committee on an Oral Health Initiative . Advancing Oral Health in America. National Academies Press; Washington: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oral Health: Dental Disease Is a Chronic Problem Among Low-income Populations. U.S. General Accounting Office; Washington: 2000. GAO/HEHS publication 00-72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guide to Children's Dental Care in Medicaid. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Washington: 2004. [Jan. 16, 2012]. www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Downloads/Child-Dental-Guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General, National Institutes of Dental and Craniofacial Research . Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; Rockville, Md.: 2000. p. 63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargas CM, Crall JJ, Schneider DA. Sociodemographic distribution of pediatric dental caries: NHANES III, 1988-1994. JADA. 1998;129(9):1229–1238. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newacheck PW, Hughes DC, Hung YY, Wong S, Stoddard JJ. The unmet health needs of America's children. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 part 2):989–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guideline on Periodicity of Examination, Preventive Dental Services . Anticipatory Guidance/Counseling and Oral Treatment for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; Chicago: 2009. [Jan. 16, 2013]. www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_Periodicity.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crall J, Litch SC. The AAPD's Medicaid EPSDT Dental Periodicity Schedule Initiative: Update for Medicaid and SCHIP Dental Association; Presented at: National Oral Health Conference; Denver. April 29, 2007; [Dec. 5, 2012]. www.medicaiddental.org/Docs/2007Presentations/Crall_Litch.ppt. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors [Dec. 5, 2012];Summary Report: Synopses of State Dental Public Health Programs—Data for FY 2010-2011. 2012 www.astdd.org/docs/State_Synopsis_Report_SUMMARY_2012.pdf.

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [Jan. 29, 2013];2008 National Dental Summary. 2009 Jan; www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Downloads/2008-National-Dental-Sum-Report.pdf Accessed Jan. 29, 2013.

- 16.Rosenbach ML, Gavin NI. Early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment and managed care. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:507–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Jan. 29, 2013];Idaho Medicaid Standard State Plan. www.healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/Portals/0/Medical/MoreInformation/Idaho%20Medicaid%20Standard%20Benefit%20Plan%206-2008%20_2_.pdf.

- 18.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Vital Health Stat. 2007;11(248):1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomar SL, Reeves AF. Changes in the oral health of US children and adolescents and dental public health infrastructure since the release of the Healthy People 2010 Objectives. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(6):388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider D, Crall JJ. EPSDT periodicity schedules and their relation to pediatric oral health standards in Head Start and Early Head Start. National Oral Health Policy Center; Los Angeles: 2005. [Jan. 17, 2013]. www.aapd.org/assets/1/7/Periodicity-PeriodicityBrief.pdf. [Google Scholar]