Abstract

Objective

This paper reviews available studies that applied the PEN-3 cultural model to address the impact of culture on health behaviors.

Methods

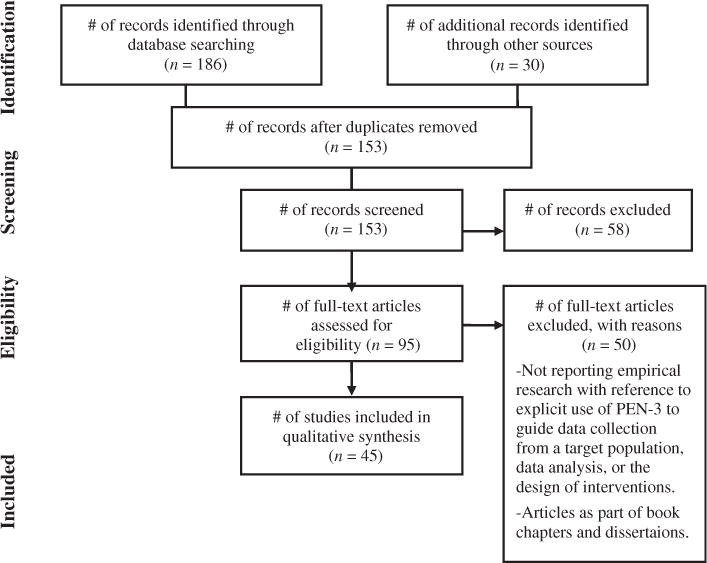

We search electronic databases and conducted a thematic analysis of empirical studies that applied the PEN-3 cultural model to address the impact of culture on health behaviors. Studies were mapped to describe their methods, target population and the health behaviors or health outcomes studied. Forty-five studies met the inclusion criteria.

Results

The studies reviewed used the PEN-3 model as a theoretical framework to centralize culture in the study of health behaviors and to integrate culturally relevant factors in the development of interventions. The model was also used as an analysis tool, to sift through text and data in order to separate, define and delineate emerging themes. PEN-3 model was also significant with exploring not only how cultural context shapes health beliefs and practices, but also how family systems play a critical role in enabling or nurturing positive health behaviors and health outcomes. Finally, the studies reviewed highlighted the utility of the model with examining cultural practices that are critical to positive health behaviors, unique practices that have a neutral impact on health and the negative factors that are likely to have an adverse influence on health.

Discussion

The limitations of model and the role for future studies are discussed relative to the importance of using PEN-3 cultural model to explore the influence of culture in promoting positive health behaviors, eliminating health disparities and designing and implementing sustainable public health interventions.

Keywords: culture, PEN-3 cultural model, health behaviors, health interventions

Introduction: the PEN-3 cultural model

Over the past decade, available evidence focusing on the impact of culture on health has increased dramatically (Airhihenbuwa 2007a; Dutta 2007; Airhihenbuwa and Liburd 2006; Shaw et al. 2009). This indicates not only a widespread and growing interest in the influence of culture but also the realization of its importance in eliminating health disparities, addressing health literacy, and designing and implementing effective public health interventions (Airhihenbuwa and Liburd 2006; Shaw et al. 2009; Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004). This increasing focus, however, requires a clear understanding of the impact of culture on health. Culture in this context refers to shared values, norms, and codes that collectively shape a group’s beliefs, attitudes, and behavior through their interaction in and with their environments (Airhihenbuwa 1999). To explore the influence of culture on individual health is ‘to recognize that the forest is more important than the individual tree’ (Airhihenbuwa 1999). Also, exploring the cultural context of the forest allows one to understand and appreciate the ways in which the individual trees are shaped as well as explore the roles, connections, and relationships (whether positive or negative) that exist between the trees (Singhal 2003). These cultural dynamics are essential for public health interventions to be effective and sustainable.

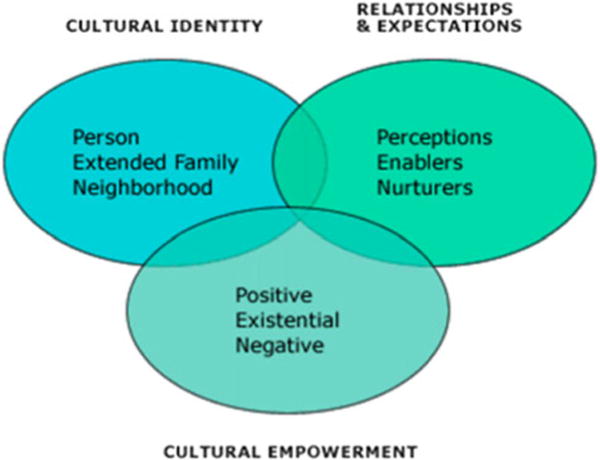

One model that has been at the forefront of understanding the influence of culture on health is the PEN-3 cultural model (See Figure 1). Developed by Airhihenbuwa (1989) in response to the apparent omission of culture in explaining health outcomes in existing health behavior theories and models (Airhihenbuwa 1990), the PEN-3 cultural model centralizes culture in the study of health beliefs, behaviors, and health outcomes (Airhihenbuwa 1995). The model also places culture at the core of the development, implementation, and evaluation of successful public health interventions (Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004; Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a). It focuses on the role of culture as a connecting web by which individual perceptions and actions regarding health are shaped and defined (Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a, 2007b), while acknowledging that these perceptions and actions are building blocks in constructing health beliefs that are reproduced to express their cultural beliefs (Airhihenbuwa 2007a). Also, the PEN-3 cultural model offers an organizing frame to centralize culture when defining health problems and framing their solutions (Airhihenbuwa 1995, 2007a, 2007b). Moreover, these solutions are framed to encourage and reward positive values, which are better sustained, rather than focusing only on negative values.

Figure 1.

The PEN-3 cultural model.

The PEN-3 cultural model consists of three primary domains: (1) Cultural Identity, (2) Relationships and Expectations, and (3) Cultural Empowerment. Each domain includes three factors that form the acronym PEN; Person, Extended Family, Neighborhood (Cultural Identity domain); Perceptions, Enablers, and Nurturers (relationship and expectation domain); Positive, Existential and Negative (Cultural Empowerment domain). The Cultural Identity domain highlights the intervention points of entry. These may occur at the level of persons (e.g., mothers or health care workers), extended family members (grandmothers), or neighborhoods (communities or villages). With the Relationships and Expectations domain, perceptions or attitudes about the health problems, the societal or structural resources such as health care services that promote or discourage effective health-seeking practices, as well as the influence of family and kin in nurturing decisions surrounding effective management of health problems are examined. With the Cultural Empowerment domain, health problems are explored first by identifying beliefs and practices that are positive, exploring and highlighting values and beliefs that are existential and have no harmful health consequences, before identifying negative health practices that serve as barriers. In this way, cultural beliefs and practices that influence health are examined whereby solutions to health problems that are beneficial are encouraged, those that are harmless are acknowledged, before finally tackling practices that are harmful and have negative health consequences.

To date, the PEN-3 cultural model has been used to address problems associated with HIV, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, malaria, nutrition, smoking, and other issues requiring an understanding not only of behavior but also of related cultural contexts. There is a need, however, to understand how this model has been applied in these studies, what approach (if any) is used to guide data collection and analysis, common thematic representations generated from the application of the model, limitations associated with using this model, and future directions with respect to application of the model. In this paper, we review available literature to specifically explore how the PEN-3 cultural model has been applied to examine the impact of culture on health behaviors and health outcomes. We present an overview of the available literature and highlight common themes that emerge from the application of the PEN-3 cultural model. We also discuss the limitations of the model and conclude by discussing future directions with the model, particularly in reference to what sets it apart from other conventional public health models and why it is critical in the design of culturally appropriate public health interventions needed to eliminate inequities in health.

Review search methods and inclusion criteria

A systematic search of the literature published between 1989 and 2013 which utilized PEN-3 cultural model as a theoretical framework was conducted using Google Scholar, Medline, Proquest, Psyinfo, Social Science citation index, Sociological abstracts, and Web of Science. Following were the keywords: PEN-3 cultural model, PEN-3 cultural model + Disease (such as HIV and AIDS, cancer, etc.). The search term PEN-3 cultural model and Airhihenbuwa was also used to widen the search. Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (1) utilized the PEN-3 cultural model as a theoretical framework, (2) reported health behavior or health outcome data that illustrates how the PEN-3 cultural model was used to guide data collection and/or analysis, and presentation of results, and (3) included men, women, children, or communities in data collection. Studies of culturally adapted interventions based on the PEN-3 cultural model were also of particular interest. Following were the exclusion reasons: (1) no information on the use of PEN-3 cultural model as a framework for data collection and/or analysis, (2) no information on the health behavior or health outcome, or target population of interest, and (3) no information related to the study results or the use of the PEN-3 model in the design of culturally adapted interventions. Articles that were mainly review articles and articles found in books and dissertations were excluded. The abstracts of all of the documents were initially screened by one reviewer; however, the full-text documents were retrieved and re-screened by two reviewers independently.

Document appraisal and synthesis of papers

PRISMA guidelines were used to guide reporting of the documents reviewed and a flow diagram is shown in Figure 2. The quality of the documents retrieved was appraised for appropriateness of the methodology used in the study including the description of the purpose, target population, and context for the study, ethics, rigor of data collection and analysis, relevance and richness of the findings, as well as the clarity of the discussions or conclusions of the overall study. The documents were initially arranged based on the public health issue explored. Next, each document was reviewed to determine how the PEN-3 cultural model was used to guide data collection and/or analysis, as well as interpretation of the findings. Furthermore, thematic analysis was applied across the available literature to identify common themes that emerge when the PEN-3 cultural model is applied to address cultural aspects of health behaviors.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of studies applying the PEN-3 cultural model.

Results

A total of 153 unique references meeting the search criteria were initially retrieved following the removal of duplicates. However, after careful screening, 45 articles meeting the inclusion criteria were retained for this review. The characteristics and findings of the articles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of studies applying the PEN-3 cultural model.

| No. | Reference | Method | Target population | Behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs | Health outcome | PEN-3 cultural model application and/or findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sheppard et al. (2010) | In-depth interviews | N = 34 (14 breast cancer patients in active treatment, 10 survivor advocates, and 10 cancer providers) | Treatment decisions | Breast cancer | Reported key perceptions (such as sharing/hearing stories of survival, strong faith), enablers (patient-provider relationship, need/desire for better communication) and nurturers (other survivors family, faith in God, interaction with providers) were important to women when making adjuvant therapy decisions. These findings were used to develop an intervention strategy to promote better patientprovider communication. |

| 2 | Ka’opua (2008) | Focus groups and individual interviews | N = 60 Native Hawaiian women | Mammogrammy use | Breast cancer | Participants viewed mammograms as beneficial, not harmful, and important to health. Family and older women were viewed the primary focus of family-oriented health interventions, with men and younger women as the secondary foci. Messages of hope (such as how screening benefited women and families) and of help (examples of family support) were suggested, while encouragement from spiritual leaders or loved ones of survivors may be especially valuable and facilitate screening intent. Finally inclusion of spiritual practices and time for talk story (culturally familiar style of discussion) enhanced cultural responsiveness to intervention. |

| 3 | Sheppard et al. (2008) | Focus groups | N = 22 (5 Latina breast cancer survivors and 17 Latinas in treatment) | Treatment decision-making | Breast cancer | Results included (1) key perceptions of Latinas that influences treatment decisions were low knowledge and self-efficacy in making decisions and communicating with providers, cancer fatalism, and misconceptions and negative expectations regarding chemotherapy; (2) key enablers were family relationships, patient–physician interactions, and access factors; (3) key nurturers were family members, other Latina survivors, spirituality/faith in God, self-reliance and support groups. |

| 4 | Kline (2007) | Generative rhetorical criticism | N=7 educational pamphlets on breast cancer | Cultural sensitivity | Breast cancer | In thematizing the messages in the pamphlets using the PEN-3 framework, the findings revealed that although messages were not inaccurate, they were constituted by rhetorical choices that emphasized racial-ethnic differences to support an argument in favor of mammography but conversely obscured many racial and cultural differences when addressing mammography barriers. |

| 5 | White et al. (2012) | Needs/assets assessment | N = 782 Latina immigrants | Screening behavior | Breast and cervical cancer | Results indicate that using the theoretical model in outreach design and implementation, it is possible to reach a substantial number of Latina immigrants and connect them to cancer screening services. |

| 6 | Erwin et al. (2010) | Focus groups | N = 112 Latinas in New York City (nine focus groups) and rural and urban sites in Arkansas (four focus groups) | Screening behavior | Breast and cervical cancer | Results show that the family takes precedence with interventions. Thematic analyses revealed that traditional beliefs and practices, such as machismo is objectively distributed with positive, existential, and negative attributes. Indeed, the recognition of the positive attributes for machismo allowed the research team to examine this as a cultural asset, rather than only as a negative as reported in most studies. |

| 7 | Erwin et al. (2005) | Focus groups and questionnaires. | N = 120 Latinos in Arkansas and New York City | Screening behavior | Breast and cervical cancer | Showed a mechanism for creating a culturally competent program, Esperanza y Vida, through progressively analyzing the findings to define the key perceptions, enablers, and nurturers, then applying this information to construct program components to address appropriate health behavior and cultural components that address the specific needs of a diverse Latino population. |

| 8 | Scarinci et al. (2012) | Focus groups | N = 13 Latina immigrants | Sexual risk reduction and Pap smear screening | Cervical cancer | The model provided theoretical guidance for the development of a culturally relevant intervention focusing on primary (sexual risk reduction) and secondary (Pap smear) prevention of cervical cancer among Latina immigrants. |

| 9 | Williams and Amoateng (2012) | Focus groups | N = 29 Ghanaian men | Screening behavior | Cervical cancer | Targets for education interventions were identified including inaccurate knowledge about cervical cancer and stigmatizing beliefs about cervical cancer risk factors. Cultural taboos regarding women’s health care behaviors were also identified. Several participants indicated that they would be willing to provide spousal support for cervical cancer screening if they knew more about the disease and the screening methods. |

| 10 | Osann et al. (2011) | Focus group | N = 12 patients (6 English speaking, 6 Spanish speaking) | Recruitment and retention in cancer clinical trials | Cervical cancer | The model was adopted for the improvement of existing study materials as a means to update the content of educating participants regarding a clinical trial. Categorizing subthemes, grouped under the model’s categories/components, helped the researchers conceptualize and standardize the group concerns while informing the design of revisions and improvements. |

| 11 | Saulsberry et al. (2013) | Application of the PEN-3 model in the development of intervention | Adolescents ages 13–17 will be recruited from wait-lists for mental health services at community health care provider organizations | Development process, intervention, and evaluation plan for (CURB, Chicago Urban Resiliency Building). | Depression | Application of the PEN-3 model occurred in three phases. In each phase, a dimension of the model was explored and subsequent changes were made to the intervention so as to be more culturally suitable. |

| 12 | Barbara and Krass (2013) | In-depth interviews | N = 24 Maltese immigrants in Australia | Self-management | Diabetes | Cultural influences on perceptions included attitudes to practitioners, treatment and peer experiences. Enablers included attitudes toward financial independence and social integration while nurturers included family and community support. |

| 13 | Melancon, Oomen-Early, and Rincon (2009) | Quantitative surveys and focus groups | N = 100 Mexican American and Mexican Native adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus | Knowledge, attitude, disease management, and self-efficacy | Diabetes | The family unit as a strong system for support. Positive behaviors such as a strong desire to live and the value of the church, existential behaviors related to the use of alternative medicines and negative behaviors such as lack of control and mistrust in T2DM diagnosis. Negative stigmas and barriers to receiving care such as language barriers comprised the relationships and expectation domains. |

| 14 | Grace et al. (2008) | Focus groups and semi-structured interviews | N = 129 (80 lay people, 29 Islamic scholars and religious leaders and 20 health professionals) | Lay beliefs and attitudes | Diabetes | Participants accepted the concept of diabetes prevention; however. practical and structural barriers to a healthy lifestyle were commonly reported as well as a strong desire to comply with cultural norms. Religious leaders provided considerable support for messages about diabetes prevention, while clinicians expressed concerns about their own limited cultural understanding about the Bangladeshis. |

| 15 | Yick and Oomen-Early (2009) | Application of the PEN-3 model in the development of intervention | Chinese American and Chinese immigrant community | Development of a domestic violence intervention | Domestic violence | The PEN-3 model, as an organizing framework, was applied to understand the phenomenon of domestic violence among Chinese Americans and Chinese immigrants in the USA. Each of the three dimensions of the PEN-3 model can be used by health educators, social workers, and counselors to guide domestic violence education, prevention, and interventions with Chinese American and immigrant communities. |

| 16 | James (2004) | Focus groups | N = 40 (19 women and 21 men) | Food choices, dietary intake, and nutrition-related attitudes | Nutrition | The identification of cultural factors that affected dietary intake (such as the importance of soul food), knowledge and attitude toward nutrition (i.e., healthful eating means giving up culture), groups to target (women and their concern with family’s health), and appropriate nutritional information channels to utilize (churches) when exploring how culture and community impact on the nutrition attitudes, food choices, and dietary intake of a select group of African Americans. |

| 17 | Airhihenbuwa et al. (1996) | Focus groups | N = 21 African-American males and 32 African-American females | Cultural aspects of eating patterns | Nutrition | The model helped to elicit perceptions about cultural food practices of African-Americans including the negative (i.e., harmful to health), the existential (unique, but health-neutral), and the positive (i.e., beneficial to health). |

| 18 | Ochs-Balcom, Rodriguez, and Erwin (2011) | Focus groups | N = 14 African-American women (9 breast cancer survivors, 5 unaffected family members of breast cancer survivors) | Perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes toward family-based genetic study | Breast cancer | A thematic output was used to design a tailored recruitment protocol for family-based genetic study, where ‘positive themes’ such as the ‘need for research and education and potential benefits to future generations’ are reinforced and ‘negative themes’ such as ‘communication barriers in sharing disease status within a family, fatalistic attitudes, and shamefulness of cancer’ are addressed to mitigate potential recruitment challenges. |

| 19 | Garcés et al. (2006) | Focus groups | N = 54 Latina immigrants | Health maintenance and health care seeking | Health maintenance and health care seeking | Results suggest that positive perceptions (i.e., importance of religion), enablers, and nurturers (i.e., support from family) associated with health maintenance and health seeking, if properly reinforced, can counter-balance negative perceptions (i.e., fear), enablers (i.e., lack of money), and nurturers (i.e., use of complementary medicine and prescribed medications without sharing information with provider) with this population of Latina immigrants. |

| 20 | Mieh et al. (2013) | Focus groups | N = 41 home-based caregivers | Care-giving | HIV and AIDS | Three primary themes emerged from our analyses: (1) perceptions associated with HIV/AIDS caregiving (positive perceptions: knowledge about HIV/AIDS and personal reflection of HIV/AIDS stigma and discrimination); (2) home-based caregivers (HBCs) assuming the roles of family (unique perceptions); and (3) voicelessness of HBCs due to the lack of support (negative perceptions: lack of support, training, and resources; family challenges; emotional and psychological impact of caregiving; and burn-out). |

| 21 | Sofolahan and Airhihenbuwa (2013) | Focus group discussions | N = 35 women living with HIV and AIDS | Reproductive desires | HIV and AIDS | The results showed that the sexual reproductive health care needs of women were not being addressed by many HCWs. Additionally, the results found that health care decisions were influenced by partners and cultural expectations of motherhood. |

| 22 | Iwelunmor and Airhihenbuwa (2012) | Focus groups | N = 110 women from three communities in South Africa | Beliefs and attitudes | HIV and AIDS | Findings reveal positive perceptions (such as use of HIV and AIDS treatment, hope and optimism about one’s future), existential views (i.e., HIV and AIDS is not the end of one’s life), and negative perceptions (HIV is a death sentence) surrounding death and loss from HIV and AIDS. Positive statements underscored perceptions that should be encouraged as well as existential beliefs that pose no threat rather than focusing solely on negative perceptions. |

| 23 | Okoror et al. (2012) | Focus groups | N = 51 women | Stigma perceptions | HIV and AIDS | The results highlight the emergent themes: expectation of care (perceptions), care delivery protocols (enablers), and physical environment (nurturers). |

| 24 | Sofolahan and Airhihenbuwa (2012) | In-depth interviews | N = 60 women living with HIV and AIDS | Childbearing decision-making | HIV and AIDS | The results revealed three themes and two subthemes: (1) the role of faith in perceptions about childbearing decisions; (2) patient–health care provider communication as an enabler in childbearing decisions; (3) partner support as a nurturing influence on childbearing decision-making, including (a) support informed by knowledge and awareness of HIV, (b) support informed by denial of infected partner’s HIV status. |

| 25 | Westmass et al. (2012) | Focus group | Surinamese and Dutch-Antilleans in the Netherlands | HIV testing | HIV and AIDS | The PEN-3 model, as a theoretical framework, was applied to centralize culture in the study of determinants that should be addressed when promoting STI/HIV testing among these communities. |

| 26 | Sofolahan et al. (2010) | Focus groups | N = 17 female nurses at two hospitals in Limpopo South Africa | Attitudes and experiences of nurses | HIV and AIDS | The themes that emerged were grouped into positive attitudes of nurses relative to PLWHA’s (people living with HIV and AIDS) gender, existential (unique) challenges nurses face in setting boundaries between professional and non-professional relationships and the negative consequence of PLWHA care experienced as ‘stigma by association.’ |

| 27 | Brown, BeLue, and Airhihenbuwa (2010) | Focus groups, key informant interviews, and questionnaires | N = 397 Black and colored participants from two South African communities. | Stigma perceptions | HIV and AIDS | Positive perceptions of familial support were important with disclosure of HIV status, while counselors were viewed as positive enablers as they serve as excellent resources in assisting families affected by HIV and AIDS. Accompanying PLWHA to clinic and support groups formed positive nurturers. Also, although families were often viewed as existential entities particularly in relation with disclosure of status. |

| 28 | Iwelunmor, Zungu, and Airhihenbuwa (2010) | Focus groups and key informant interviews | N = 48 women living with HIV and AIDS in two South African communities | Disclosure of seropositive status | HIV and AIDS | The findings revealed that there could be both positive (i.e., acceptance and support) and negative consequences (i.e., disruptions in mother–daughter relationships) associated with disclosure to mothers, while the existential role of motherhood (i.e., breastfeeding) could influence a participant’s decision to disclose. |

| 29 | Airhihenbuwa et al. (2009) | Focus groups and key informant interviews | N = 453 (345 women and 108 men) | Stigma in family and health care | HIV and AIDS | Results show that both ‘positive non-stigmatizing values’ enabled through supportive roles, ‘existential values unique to contexts’ such as the importance of food in contextualizing relationships, and ‘negative stigmatizing characteristics’ such as the blaming of HIV and AIDS on women. |

| 30 | Green et al. (2009) | Focus groups and key informant interviews | N = 73 traditional leaders or members of royal families | Mobilizing indigenous resources for anthropologically designed HIV prevention and behavior change | HIV and AIDS | The PEN-3 model, as a theoretical framework, was applied to understand aspects of indigenous leadership and cultural resources that might be accessed and developed to influence individual behavior as well as the prevailing community norms, values, sanctions, and social controls that are related to sexual behavior. |

| 31 | Okoror et al. (2007) | Focus groups and key informant interviews | N = 249 (195 women and 54 men) | Stigma and racism | HIV and AIDS | Food was viewed as an expression of support and acceptance for some HIV-positive women and as an expression of rejection for others. It also allowed an assessment of not just the negative aspects of food sharing, but also an exploration of the positive ways food is used to express love, support, and acceptance. |

| 32 | Iwelunmor et al. (2006) | Focus groups | N = 204 (150 females and 54 males) | Caregiving | HIV and AIDS | The findings highlight the positive and supportive aspects of family systems, acknowledge that family systems are unique (existential) indigenous entities, and note that family systems can be sources of stress when caring and supporting PLWHA. |

| 33 | Petros et al. (2006) | Focus group discussions and key informant interviews | N = 39 focus group discussions comprising 8 to 10 participants and 28 key informant interviews | Othering and stigma | HIV and AIDS | Findings reveal how cultural and racial positioning influence perceptions of the group considered to be responsible and thus vulnerable to HIV infections with AIDS. The findings indicate that an othering of blame is central to these positionings with blame being channeled through the multiple prisms of race, culture, homophobia, and xenophobia. |

| 34 | Bynum et al. (2012) | Questionnaire | N = 363 African-American college students | Health beliefs, vaccine acceptability, and safer sex practices | Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines | Meaningful set of factors to address beliefs and attitudes to HPV vaccination were produced with the PEN-3 model whereby ‘racial pride’ was viewed as a ‘positive enabler’ of health behavior, while health care distrust was viewed as a ‘negative perception.’ |

| 35 | Walker (2000) | Educational intervention | N = 83 African-Americans | Hypertension management and medication adherence | Hypertension | The development and tailoring of messages that were culturally sensitive and age specifics while at the same time raising awareness of the importance of hypertension management. For the intervention, the focus was on individuals and neighborhood leaders, perceptions and enablers of hypertension managements as well as the negative beliefs that influence appropriate management of hypertension. |

| 36 | Underwood et al. (1997) | Focus groups | N = 35 African-American women | Infant feeding practices | Nutritional-related illnesses | A better understanding of the infant feeding practices of low-income African-American women particularly in relation to the role cultural beliefs and life experiences play in light of practices currently recommended by health care providers within the pediatric community. |

| 37 | Iwelunmor et al. (2010) | In-depth interviews | N = 123 mothers with children less than five attending an outpatient clinic in southwest Nigeria | Treatment decisions | Malaria | Mothers’ knowledge of symptoms was important positive treatment seeking response to child febrile illness. Also beliefs related to child teething highlighted existential decisions, while the belief that febrile illness is not at all severe despite noticeable signs and symptoms were among the negative perceptions. |

| 38 | Gaston, Porter, and Thomas (2007) | Evaluations of a curriculum-based health intervention | N = 134 African-American women | To decrease the major health risk factors | Major risk factors | The PEN-3 model, as a theoretical framework, was applied to develop a curriculum-based, culture- and gender-specific health intervention, aimed at assisting mid-life African-American women to decrease the major risk factors of physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and stress. |

| 39 | Kannan et al. (2010) | Evaluation of a pre-test-post-test nutrition curriculum | N = 102 African-American women of childbearing age | Healthy eating | Maternal nutrition and protective factors in relation to birth outcome | The importance of a nutritionally balanced culturally based meals for the family using the Soul Food pyramid, teaching about essential micronutrients, encouraging eating a variety of foods, and incorporating intergenerational family-centered nutrition activities were among the findings integrated in the design of the peer-led nutrition curriculum Healthy eating and Harambee. |

| 40 | Kannan et al. (2009) | Focus groups | N = 36 (16 younger (19–25 years) and 20 older African-American women (45–60 years) | Supportive factors and barriers to healthy eating | Maternal nutrition and protective factors in relation to birth outcome | Findings revealed that culture and family relationships impacted food choices. Younger women expressed creativity with recipes, while older women expressed a desire to teach family-centered culinary skill-building classes. Both groups of women acknowledged time and budget barriers, identified the prevalence of lactose intolerance, and recognized that large grocery stores that offered food variety were not located in their community. |

| 41 | Hilton et al. (2007) | Focus groups | N = 177 participants | Cultural beliefs and practices | Oral care | The PEN-3 model facilitated and insured examination of the focus group data in a culturally sensitive and appropriate manner. |

| 42 | Abernethy et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional design | N = 655 African-American men | Screening | Prostate cancer | The influence of cultural values on recruitment of African American men for prostate cancer screening study as it allowed recruitment efforts to address cultural values that were particularly relevant for this population and health behavior. The values of the community where viewed as essential for recruitment. Also distrust of research, hidden costs associated with participation may serve as negative enablers, while partnerships with churches and specifically, church leadership were viewed as key nurturers. |

| 43 | Scarinci et al. (2007) | Focus groups | N = 108 women in private and public worksites. | Smoking cessation | Weight control decisions | Positive factors such as strong influence from parents and family members served as protective mechanism against initiation, while exposure to smoking-prompting behaviors through family members were negative factors that contributed to smoking initiation. Smoking restrictions at home and workplace and concerns about appearance were positive factors associated with smoking cessation, while stress/anxiety-relieving benefits, weight control, access/low cost of cigarettes, being around smokers and risk-exempting beliefs were negative factors. |

| 44 | Matthews, Sánchez-Johnsen, and King (2009) | Group format sessions | N = 8 African-American smokers | Smoking cessation | Respiratory illness | Identification of cultural variables that may facilitate or hinder smoking cessation among African-American smokers. For example, efforts were made to increase knowledge and readiness to quit smoking while removing salient barriers to participation in formalized smoking cessation treatment programs. |

| 45 | Beech and Scarinci (2003) | Focus groups | N = 118 African-Americans (65 men and 53 women) | Attitudes and practices | Smoking | Themes were classified according to the PEN-3 model, and they included lighting cigarettes for parents as a first experience with cigarettes, perceived stress relief benefits of smoking, use of cigarettes to extend the sensation of marijuana, and protective factors against smoking such as respect for parental rules. |

Application of PEN-3 cultural model in studies reviewed

The reviewed studies vary greatly in their application of the PEN-3 cultural model to address health behaviors through a cultural lens. While there were no differences in the application of the model by language or country studied, it was common for studies to use the PEN-3 model as a theoretical framework to centralize culture in the study of health behaviors and to integrate culturally relevant factors in the development of interventions. For example, Erwin et al. (2010) used the PEN-3 model to shape and clarify messages, program content and structure of their cancer control intervention for Latinas. Sheppard et al. (2010) utilized qualitative findings related to the PEN-3 domains to inform the implementation of a decision to support intervention for black women with breast cancer. Similarly, Kannan et al. (2010) used the domains and construct of the model to develop a curriculum to help increase nutrition support and improve the preconception nutrition of African-American women in Southeast Michigan.

Additionally, several studies also used the PEN-3 cultural model to guide data collection, analysis, and interpretation of qualitative data generated. Data analytical approaches that emerged with the use of PEN-3 include: (1) Categorization, (2) Cross-Tabulation, and (3) Recontextualization. With categorization, it was common for studies to utilize the PEN-3 model as an organizing framework to categorize themes generated from qualitative data into one of the three domains of the model. Also, while some studies utilized all three domains of the model to categorize the themes generated for data analysis, it was not uncommon for studies to use only one of the domains to be applied depending on the nature of the study. For example, in interpreting Latina immigrants’ perceptions, experiences, and knowledge regarding breast and cervical cancer screening, Erwin et al. (2010) used all three domains of the PEN-3 model to categorize emergent themes from participant’s focus group responses. However, in understanding mothers’ treatment decisions about child febrile illness, Iwelunmor et al. (2010) used only the Cultural Empowerment domain to examine positive health beliefs and practices held by mothers, existential (unique) practices that have no harmful health consequences, and negative beliefs and practices that limit recommended responses to febrile illness in children.

Another data analysis approach commonly used with the PEN-3 cultural model in reviewed studies was cross-tabulation. With this approach, it was common for existing studies to cross-tabulate the Relationships and Expectations (i.e., perceptions, enablers, nurturers) domain with the Cultural Empowerment (i.e., positive, existential, and negative) domain of the PEN-3 model to generate a 3 × 3 table containing nine categories. This approach which is often referred to as the assessment phase of the PEN-3 model provided the opportunity to arrange the emerging themes at the intersection of two domains to assess for any domain interactions (Airhihenbuwa et al. 2009; Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004). For example, in examining the challenges nurses caring for PLWHA in South Africa encounter with balancing personal and professional lives, Sofalahan et al. (2010) completed a 3 × 3 table of emerging themes by crossing the Relationships and Expectations domain with the Cultural Empowerment domain to capture the full range of nurses’ experiences from positive to negative.

With Recontextualization, Morse and Field (1995) suggest that the goal is to locate the themes generated from qualitative data within the context of established knowledge. For example, in their paper, ‘Rethinking HIV and AIDS disclosure within the context of motherhood in South Africa,’ Iwelunmor, Zungu, and Airhihenbuwa (2010) utilized the established Cultural Empowerment domain of the PEN-3 cultural model to advance knowledge on women’s disclosure of HIV seropositive status within the context of motherhood in South Africa. Similarly, Kline (2007) utilized the PEN-3 model to identify representations of Cultural Identity, Relationships and Expectations, and Cultural Empowerment in breast cancer education program that targets African-American women.

Common themes that emerge with the PEN-3 cultural model in reviewed studies

The remainder of this paper focuses on common themes that emerged in the reviewed studies (see Table 2). Indeed, three key themes consistently emerged and appear to help provide an in-depth understanding of how PEN-3 centralizes culture in the study of health behaviors and health outcomes. These themes include the importance of context, the role of family as an intervention point of entry, and the need to explore the positive aspects of culture on health behaviors.

Table 2.

Themes identified in select studies applying PEN-3 cultural model.

Themes on culture and context

The importance of centralizing cultural contexts in the study of health behaviors or health outcomes was significant in research studies utilizing the PEN-3 cultural model. For example, in understanding the specific ways in which cultural context shapes health behaviors, Abernethy et al. (2005) highlighted the importance of understanding how traditional views of masculinity influence men’s perceptions of their health particularly in African-American communities. The powerful effect of context was also central in a study on Type 2 Diabetes among British Bangladeshis in United Kingdom (Grace et al. 2008) and among Maltese immigrants in Australia (Barbara and Krass 2013). Grace et al. (2008) found that several traditional social norms and expectations potentially conflicted with efforts to achieve health-related lifestyle change. In Australia, Barbara and Krass (2013) noted that several cultural influences and traditions among Maltese immigrants influenced their motivation regarding self-management of diabetes. For example, participants reported that the traditional social behaviors including the acceptance of hospitality impacted their adherence to dietary interventions (Barbara and Krass 2013).

In the context of HIV and AIDS, the PEN-3 cultural model was used to examine the influence of cultural context in explaining stigma and HIV disclosure in South Africa. Petros et al. (2006) used the PEN-3 model to explore how people living with HIV experience ‘othering.’ The authors found that much of the current blame and othering of HIV and AIDS can be traced to the country’s complex history of racism, patriarchy, and homophobia. For example, in delineating othering by race, Petros et al. (2006) noted that ‘South Africans from different racial backgrounds blame each other as either being the source of HIV or being responsible for spreading the disease.’ Similarly, using the PEN-3 model as a guide, Iwelunmor et al. (2010) concluded that the discourse on motherhood in South Africa cannot be separated from the history of institutional discrimination that occurred during the apartheid era. The authors noted that the legacy of apartheid may affect traditional and societal expectations of mothering particularly in relation to disclosing seropositive status.

Cultural context also provides a clearer lens through which researchers might view and understand health behavior, while highlighting variables that may be most salient in future intervention design. Indeed, studies using the PEN-3 model demonstrated how cultural context matters when developing interventions and/or clinical trials focused on addressing health behaviors such as nutrition attitudes (James 2004; Airhihenbuwa et al. 1996), depression prevention (Saulsberry et al. 2013), domestic violence (Yick and Oomen-Early 2009), HIV and AIDS (Airhihenbuwa et al. 2009; Iwelunmor, Zungu, and Airhihenbuwa 2010; Okoror et al. 2012; Westmaas et al. 2012; Green et al. 2009; Mieh, Iwelunmor, and Airhihenbuwa 2013), reproductive desires (Sofolahan and Airhihenbuwa 2012, 2013), physical inactivity, stress (Gaston, Porter, and Thomas 2007), smoking (Beech and Scarinci 2003; Matthews, Sánchez-Johnsen, and King 2009; Scarinci et al. 2007), and cancer screening and awareness (Erwin et al. 2010; Osann et al. 2011; White et al. 2012).

Family as a common intervention entry point for culture

As mentioned earlier, to explore the influence of culture on health is ‘to recognize that the forest is more important than the individual tree’ (Airhihenbuwa 1999). Nowhere is this more paramount than in recognizing that illness is the responsibility of the collective. The PEN-3 cultural model emphasizes the role of the collective (family/community) in defining the health experiences of individuals, and underscores its importance in influencing health-related decisions. For example, among Native Hawaiian women, Ka’opua (2008) found that responsibility to the family influenced screening for breast cancer. Similarly, among Latinas, Sheppard et al. (2008) found that family members were key nurturers in influencing treatment decision making for breast cancer. Scarinci et al. (2012) also identified specific cultural values considered central to the Latino culture that may play a role in cervical cancer prevention. For example, the authors noted that family (familiarismo) is one of the key Latino values heavily relied upon when dealing with problems and difficulties including health problems. This was also the case in a cancer intervention for diverse Latinas where Erwin et al. (2010) found that family – both nuclear and extended – takes precedence when addressing ways to produce positive screening behavior change in subgroups of Latinas.

The need and motivation to keep families healthy was also reported by Garcés, Scarinci, and Harrison (2006) who also utilized the PEN-3 model to highlight the importance of support from the family and extended family with health maintenance and health care-seeking practices among Latina immigrants. PEN-3 qualitative findings also provided indicators for designing a tailored recruitment protocol for a family-based genetic study on breast cancer (Ochs-Balcom, Rodriguez, and Erwin 2011). In a paper on family systems and HIV and AIDS, Iwelunmor et al. (2006) reported that family systems can be sources of support, unique indigenous entities, and sources of stress when addressing the care and support needs of family members living with HIV and AIDS. However, the need to take into account families’ experiences with HIV and AIDS was critical in the development of interventions aimed at reducing the burden of HIV and AIDS-related stigma in the family and improve care and support for PLWHA (Iwelunmor et al. 2006). In describing the impact of AIDS-related stigma, using the PEN-3 model, Airhihenbuwa et al. (2009) noted that understanding how families cope with health and illness is central to developing sustainable public health interventions aimed at reducing HIV and AIDS stigma, particularly with identifying key members of the family who have made a difference in the lives of PLWHA.

In determining targets for public health interventions as part of the Cultural Identity domain of the PEN-3 model, James (2004) reported that African-American women are key agents of cultural transformation as they are usually concerned with the family’s health, responsible for food preparation, set standards for healthful and unhealthy eating, and provide access to other family members. Underwood et al. (1997) reported that infant feeding practices among low-income African-American women were ‘learned’ from family members and others within the community and ‘shared’ with other new mothers within the community as well.

Positive aspects of culture as a critical domain in PEN-3

A central feature of the PEN-3 cultural model is that it provides researchers and interventionists a strategy for identifying and encouraging positive health behaviors (Airhihenbuwa and Webster 2004). This approach of examining positive behaviors within a cultural context has been the subject of other major fields of study; like psychology, which traditionally focus on negative behaviors and problems. The growth of Positive Psychology, however, which emerged in 2000 is an example of a compelling evidence of the benefit of focusing on positive aspects of behavior, actions, and indeed culture. This field of psychology encouraged a paradigm shift from a focus on negative aspects of individuals and related pathology to identifying and bolstering positive personal attributes for understanding how people thrive and survive even in situations and environments of adversity (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Prevention researchers began to realize that focusing research and practice on personal weakness and symptomatology left clinicians ill-prepared for preventing illness. The key here is to focus rather on strengthening and harnessing personal strengths which could act as buffers against illnesses.

Like individual behaviors, positive aspects of culture can help promote healthy behaviors (i.e., knowledge of screening and testing, dietary habits, etc.) that lead to improved health outcomes. For example, among Native Hawaiian women, Ka’opua (2008) utilized talk story, a culturally familiar style of discussion to engage women in dialog on the importance of breast cancer screening. Similarly, in describing breast cancer treatment experiences, Sheppard et al. (2008) noted that cultural values such as personalismo (warm and personal relationships with individuals, i.e., clinicians) were central in enabling Latinas to expand their knowledge of treatment options and create a better understanding and willingness to take chemotherapy.

Within the context of nutrition, in describing how culture impacts dietary habits, James (2004) noted that food, particularly ‘soul food’ is a positive and existential dietary behavior practiced among African Africans and used to celebrate and affirm culture. The authors noted that while food myths, inaccurate information, and negative behaviors surrounding food choices and dietary intake are common among African-Americans, the positive aspects of traditional African-American diets should be stressed, even when highlighting the need for modifying or reducing the negative practices, such as frying foods, which is known to be harmful to health (James 2004).

With the understanding that public health research and interventions should be as much about promoting positive values as changing negative ones, Ochs-Balcom, Rodriguez, and Erwin (2011) utilized the PEN-3 model to identify positive and negative themes relevant to establishing community partnership to optimize recruitment of African-American women in a breast cancer epidemiology study. While the need for more information about breast cancer and potential benefits to younger generations were among the positive themes identified, negative themes included lack of knowledge regarding research participation, issues related to confidentiality of data, and breast cancer research in general (Ochs-Balcom, Rodriguez, and Erwin 2011). In tailoring their overall recruitment and study protocol, the authors reinforced positive themes and revised negative themes in a variety of ways.

As evidenced through its use in these studies, the PEN-3 model has opened space for researchers to discuss behavior and culture from a positive perspective. Discussing the positive aspects of culture and behavior, while reframing those cultural occurrences traditionally viewed as negative allows researchers to develop culturally congruent explanations and culturally relevant interventions for health. Culture is examined and utilized here with a strength-based approach as it is presented to edify public health research, not merely as yet another study limitation.

Limitations and future directions of the PEN-3 model based on reviewed studies

There are some limitations associated with the use of the PEN-3 cultural model as identified in the studies reviewed. First, because recognizing and responding to cultural aspects of health behavior is a challenging process, almost all of the studies reviewed utilized PEN-3 model to generate and analyze formative/qualitative data. None of the studies reviewed appear to actually test any construct or domain of the model in a quantitative manner. While testing the different domains of the model quantitatively will provide further evidence of the reliability and effectiveness of the PEN-3 model in addressing cultural aspects of health behavior, findings from formative/qualitative data do underscore the model’s foundation and premise in offering a strategy to excavate and unpack rich descriptions of the complex array of factors whether positive or negative, or at the individual, family, or community levels for influencing health behaviors. It also represents an important approach over other efforts that primarily focus solely on Western constructs of individual factors that influence health behaviors. As one study aptly stated, ‘the model takes the thematic interpretation of qualitative data into an analysis process that sorts beliefs and concepts into discrete domains that can then be contextualized with specific behaviors, delivery and messages’ (Erwin et al. 2010). Given that none of the included studies tested the constructs or domains of the model quantitatively, for boarder utilization, future studies should develop PEN-3 cultural model instruments that are reliable and valid with assessing the impact of culture on health.

Another limitation in using the PEN-3 model is transferability, that is, the extent to which the findings from these qualitative studies can be transferred from one context to another, even though some of the findings in this review show similar outcomes in different study populations. Indeed, caution should be exercised in transferring the findings generated using the PEN-3 model to other contexts as cultural aspects of health behaviors in one setting may not be applicable to other settings. Hence, the recommendation that PEN-3 should always begin with qualitative study to capture the uniqueness of each context, culture, and population. Lastly, as part of the intervention phase of PEN-3, it is recommended that researchers return to the community where data are collected to share lessons learned in the assessment phase (i.e., Cross-Tabulation of domains). It is not clear which of these studies included this aspect of the model as it was not reported. It may be the case that this phase was completed but authors plan to present this information in a separate manuscript. We recommend that returning and presenting findings to the community should be considered a critical part of using PEN-3.

Discussion

This review paper expands the current literature on the impact of culture on health and explores how a cultural model has been used to address health behaviors and health outcomes. The PEN-3 cultural model focuses on the impact of culture on health beliefs and actions, and proposes that public health and health promotion should not focus only on the individual, but instead on cultural context that nurtures a person’s health behavior in his or her family and community (Airhihenbuwa 2007b).

Whether it is HIV/AIDS, cancer, or smoking, the findings of this review indicate that for different conditions/behaviors/experiences, culture remains the key to effectively examining their impact on health and thus framing solutions. This has implications particularly in the context of designing sustainable public health interventions focused on reducing health disparities.

Furthermore, culturally appropriate and compelling strategies for behavior change will require an understanding not only of individual-level factors but also of factors related to cultural norms including conditions in which people live, grow, eat, and die. The findings reported here demonstrate that the PEN-3 model is critical in developing and implementing health interventions anchored in culture. For example, the studies reviewed showed that the model provided the opportunity to challenge the assumption that positive health behavior is solely the function of individual responsibility. With the PEN-3 model, authors unpacked biases regarding the health behaviors of interest, and engaged research participants themselves with efforts aimed at promoting positive health outcomes (White et al. 2012).

The reviewed studies also highlight how the model is applied to explore the health behavior of interest. Various studies used the PEN-3 model as an ‘analysis tool’ to sift through text and data in order to separate, define, and delineate the comments of participants into themes that illustrate how culture influences health behaviors. Studies also use the model to explore not only how cultural context shapes beliefs and practices, but also how family systems play a critical role in enabling or nurturing positive health behaviors and health outcomes. The studies reviewed show that regardless of the health outcome or health behavior of interest, the PEN-3 cultural model provides the opportunity to examine cultural practices that are critical to positive health behaviors, acknowledges unique practices that have a neutral impact on health, and identifies negative factors that are likely to have an adverse influence on health. Also, with the understanding that the way that people perceive their health is rooted in relationships and interactions characteristic of their culture, the PEN-3 cultural model helped to focus research not only on the context that nurtures the health behavior of interest but also on the role of the collective (e.g., family) in influencing health behaviors.

While there are some limitations with the model as discussed earlier, future studies should extend its use beyond formative and/or qualitative data collection and analysis to begin to develop a rigorous evidence base of PEN-3 variables that effectively and reliably assess the impact of culture on various health outcomes. We do not recommend that all studies incorporate quantitative constructs in their study design. Qualitative findings using the PEN-3 cultural model continue to be very important and they do provide some key outcomes on which quantitative design could be used to advance current use of the model to better understand culture and health. The onus is therefore on researchers to advance and build on current methodological approaches (whether quantitative or qualitative) using PEN-3 cultural model to address health behaviors. Furthermore, what is most critical is that future efforts be made to ensure that researchers using the PEN-3 model return to the community where data were generated to share their findings and further learn from the community before deciding where to begin their interventions. This process which is referred to as ‘point of intervention entry’ is the most crucial component of the model as it ensures community engagement in the framing of solutions to health problems, while identifying those cultural influences that are beneficial and should be encouraged, acknowledging those that are harmless, and then tackling those practices that are harmful and have negative health consequences.

Taken together, the 45 articles presented in this review highlight the importance of exploring the impact of culture on health, particularly in designing effective public health interventions. At a time when researchers are questioning the limitations of focusing exclusively on individual health behaviors, a focus on culture is especially pertinent. PEN-3 offers the opportunity to view culture as the raison d’etre of health behavior as culture gives meanings to the coexistence of what is good, indifferent, and bad. What is central to PEN-3, then is to ensure that interventions are developed not only with the bad in mind (as is often the case), but to begin with identifying and promoting the good while recognizing the unique aspects of culture with respect to health. PEN-3 also enables an examination of the perceptions people may have about a health behavior, the resources or institutional forces that enable or disenable actions toward the health behavior and the influence of family, friends, and communities in nurturing the behavior. In this way, the construction and interpretation of health behaviors are examined as functions of broader cultural contexts particularly in relation to how culture defines the roles of persons, and their expectations in family and community relationships.

Conclusion

Whereas many of the conventional health behavior theories often focus on the individual to promote change, PEN-3 offers a culture-centered approach to health that extends analysis to the totality of the contexts that either inhibit or nurture the individual. In doing so, this approach unpacks assumptions surrounding individual responsibilities or capabilities so as to expand and examine the role other factors play in inhibiting and/or nurturing healthy behavior change.

If we are to achieve equity in health through designing and implementing effective public health research and interventions, culture should be a critical factor in framing the way forward. While addressing individual behaviors is necessary, a focus on individual behavior alone at the exclusion of the cultural context limits the success of public health interventions. Moreover, given the overwhelming need for effective public health research and interventions that address health behaviors from a collective rather than an individual perspective, a cultural approach to health offers the opportunity to identify the broader contextual relationships and expectations whether positive, unique, or negative. In framing the impact of culture on health, the PEN-3 cultural model offers a tool for those who are committed to addressing health issues and problems to do so by acknowledging those aspects of culture that may negatively influence health, but always identifying a strength-based approach to public health intervention and education utilizing positive aspects of culture. Every culture has something positive, something unique, and something negative. Together, these factors are essential to eliminating inequities in health and advancing the mission of public health research and interventions globally.

Key messages.

PEN-3 cultural model is a theoretical framework that centralizes culture in the study of health. The model also place culture at the core of development, implementation, and evaluation of health interventions.

The findings from the literature reviewed demonstrate that PEN-3 model helped to focus research not only on the context that nurtures the health behavior of interest but also on the role of the collective (e.g., family) in influencing health behaviors.

PEN-3 cultural model also provides the opportunity to examine cultural practices that are critical to positive health behaviors, acknowledges unique practices that have a neutral impact on health and identifies negative factors that are likely to have an adverse influence on health.

References

- Abernethy AD, Magat MM, Houston TR, Arnold HL, Jr, Bjorck JP, Gorsuch RL. Recruiting African American Men for Cancer Screening Studies: Applying a Culturally Based Model. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32:441–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Perspectives on AIDS in Africa: Strategies for Prevention and Control. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1989;1:57–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. A Conceptual Model for Culturally Appropriate Health Education Programs in Developing Countries. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 1990;11(1):53–62. doi: 10.2190/LPKH-PMPJ-DBW9-FP6X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Health and Culture: Beyond the Western Paradigm. California: Sage Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Of Culture and Multiverse: Renouncing ‘the Universal Truth’. Journal of Health Education. 1999;30:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa C. Healing Our Differences: The Crisis of Global Health and the Politics of Identity. New York: Rowman and Littlefield; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO. 2007 SOPHE Presidential Address: On Being Comfortable with Being Uncomfortable: Centering an Africanist Vision in Our Gateway to Global Health. Health Education & Behavior. 2007b;34(1):31–42. doi: 10.1177/1090198106291377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Liburd L. Eliminating Health Disparities in the African American Population: The Interface of Culture, Gender, and Power. Health Education & Behavior. 2006;33:488–501. doi: 10.1177/1090198106287731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Webster JD. Culture and Africa Contexts of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Care and Support. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance. 2004;1:1–13. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa CO, Kumanyika S, Agurs TD, Lowe A, Saunders D, Morssink CB. Cultural Aspects of African American Eating Patterns. Ethnicity & Health. 1996;1:245–260. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa C, Okoror T, Shefer T, Brown D, Iwelunmor J, Smith E, Adam M, Simbayi L, Zungu N, Dlakulu R. Stigma, Culture, and HIVand AIDS in the Western Cape, South Africa: An Application of the PEN-3 Cultural Model for Community-Based Research. Journal of Black Psychology. 2009;35:407–432. doi: 10.1177/0095798408329941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbara S, Krass I. Self Management of Type 2 Diabetes by Maltese Immigrants in Australia: Can Community Pharmacies Play a Supporting Role? International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 2013;21(5) doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech BM, Scarinci IC. Smoking Attitudes and Practices among Low-Income African-Americans: Qualitative Assessment of Contributing Factors. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2003;17:240–248. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DC, BeLue R, Airhihenbuwa CO. HIV and AIDS-related Stigma in the Context of Family Support and Race in South Africa. Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15(5):441–458. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.486029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum SA, Brandt HM, Annang L, Friedman DB, Tanner A, Sharpe PA. Do Health Beliefs, Health Care System Distrust, and Racial Pride Influence HPV Vaccine Acceptability among African American College Females? Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17(2):217–226. doi: 10.1177/1359105311412833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum SA, Brandt HM, Sharpe PA, Williams MS, Kerr JC. Working to Close the Gap: Identifying Predictors of HPV Vaccine Uptake among Young African American Women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(2):549–561. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta MJ. Communicating about Culture and Health: Theorizing Culture-Centered and Cultural Sensitivity Approaches. Communication Theory. 2007;17:304–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00297.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Feliciano-Libid L, Zamora D, Jandorf L. Incorporating Cultural Constructs and Demographic Diversity in the Research and Development of a Latina Breast and Cervical Cancer Education Program. Journal of Cancer Education. 2005;20(1):39–44. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Treviño M, Saad-Harfouche FG, Rodriguez EM, Gage E, Jandorf L. Contextualizing Diversity and Culture within Cancer Control Interventions for Latinas: Changing Interventions, not Cultures. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés IC, Scarinci IC, Harrison L. An Examination of Sociocultural Factors Associated with Health and Health Care Seeking among Latina Immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2006;8:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Prime Time Sister Circles: Evaluating a Gender-Specific, Culturally Relevant Health Intervention to Decrease Major Risk Factors in Mid-Life African-American Women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99:428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace C, Begum R, Subhani S, Kopelman P, Greenhalgh T. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes in British Bangladeshis: Qualitative Study of Community, Religious, and Professional Perspectives. British Medical Journal. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EC, Dlamini C, D’Errico NC, Ruark A, Duby Z. Mobilising Indigenous Resources for Anthropologically Designed HIV-Prevention and Behaviour-Change Interventions in Southern Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;8:389–400. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.4.3.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton IV, Stephen S, Barker JC, Weintraub JA. Cultural Factors and Children’s Oral Health Care: A Qualitative Study of Carers of Young Children. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2007;35(6):429–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO. Cultural Implications of Death and Loss from AIDS Among Women in South Africa. Death Studies. 2012;36(2):134–151. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2011.553332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO, Okoror TA, Brown DC, BeLue R. Family Systems and HIV/AIDS in South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2006;27:321–335. doi: 10.2190/IQ.27.4.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Idris O, Adelakun A, Airhihenbuwa CO. Child Malaria Treatment Decisions by Mothers of Children Less than Five Years of Age Attending an Outpatient Clinic in South-West Nigeria: An Application of the PEN-3 Cultural Model. Malar Journal. 2010;9:354. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwelunmor J, Zungu N, Airhihenbuwa CO. Rethinking HIV/AIDS Disclosure among Women within the Context of Motherhood in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1393. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D. Factors Influencing Food Choices, Dietary Intake, and Nutrition-Related Attitudes among African Americans: Application of a Culturally Sensitive Model. Ethnicity and Health. 2004;9:349–367. doi: 10.1080/1355785042000285375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ka’opua LS. Developing a Culturally Responsive Breast Cancer Screening Promotion with Native Hawaiian Women in Churches. Health & Social Work. 2008;33(3):169–177. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.3.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Sparks AV, Webster JDW, Krishnakumar A, Lumeng J. Healthy Eating and Harambee: Curriculum Development for a Culturally-Centered Bio-Medically Oriented Nutrition Education Program to Reach African American Women of Childbearing Age. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010;14:535–547. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0507-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Webster D, Sparks A, Acker CM, Greene-Moton E, Tropiano E, Turner T. Using a Cultural Framework to Assess the Nutrition Influences in Relation to Birth Outcomes among African American Women of Childbearing Age: Application of the PEN-3 Theoretical Model. Health Promotion Practice. 2009;10(3):349–358. doi: 10.1177/1524839907301406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline KN. Cultural Sensitivity and Health Promotion: Assessing Breast Cancer Education Pamphlets Designed for African American Women. Health Communication. 2007;21(1):85–96. doi: 10.1080/10410230701283454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Sánchez-Johnsen L, King A. Development of a Culturally Targeted Smoking Cessation Intervention for African American Smokers. Journal of Community Health. 2009;34:480–492. doi: 10.1007/s10900-009-9181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melancon J, Oomen-Early J, Rincon LD. Using the PEN-3 Model to Assess Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs about Diabetes Type 2 among Mexican American and Mexican Native Men and Women in North Texas. International Electronic Journal of Health Education. 2009;12:203–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mieh TM, Iwelunmor J, Airhihenbuwa CO. Home-Based Caregiving for People Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2013;24:697–705. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. California: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Rodriguez EM, Erwin DO. Establishing a Community Partnership to Optimize Recruitment of African American Pedigrees for a Genetic Epidemiology Study. Journal of Community Genetics. 2011;2(4):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0059-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoror TA, Airhihenbuwa CO, Zungu M, Makofani D, Brown DC, Iwelunmor J. “My Mother Told Me I Must Not Cook Anymore”—Food, Culture, and the Context of HIV-and AIDS-Related Stigma in Three Communities in South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2007;28(3):201–213. doi: 10.2190/IQ.28.3.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoror TA, Belue R, Zungu N, Adam AM, Airhihenbuwa CO. HIV Positive Women’s Perceptions of Stigma in Health Care Settings in Western Cape, South Africa. Health Care for Women International. 2012 doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.736566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osann K, Wenzel L, Dogan A, Hsieh S, Chase DM, Sappington S, Monk BJ, Nelson EL. Recruitment and Retention Results for a Population-Based Cervical Cancer Biobehavioral Clinical Trial. Gynecologic Oncology. 2011;121:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petros G, Airhihenbuwa CO, Simbayi L, Ramlagan S, Brown B. HIV/AIDS and ‘Othering’ in South Africa: The Blame Goes On. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2006;8(1):67–77. doi: 10.1080/13691050500391489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulsberry A, Corden ME, Taylor-Crawford K, Crawford TJ, Johnson M, Froemel J, Walls A, Fogel J, Marko-Holguin M, Van Voorhees BW. Chicago Urban Resiliency Building (CURB): An Internet-Based Depression-Prevention Intervention for Urban African-American and Latino Adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(1):150–160. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9627-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Bandura L, Hidalgo B, Cherrington A. Development of a Theory-Based (PEN-3 and Health Belief Model), Culturally Relevant Intervention on Cervical Cancer Prevention among Latina Immigrants Using Intervention Mapping. Health Promotion Practice. 2012;13(1):29–40. doi: 10.1177/1524839910366416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Silveira AF, dos Santos DF, Beech BM. Sociocultural Factors Associated with Cigarette Smoking Among Women in Brazilian Worksites: A Qualitative Study. Health Promotion International. 2007;22(2):146–154. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive Psychology: An Introduction. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):5. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SJ, Huebner C, Armin J, Orzech K, Vivian J. The Role of Culture in Health Literacy and Chronic Disease Screening and Management. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2009;11:460–467. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Williams KP, Harrison TM, Jennings Y, Lucas W, Stephen J, Robinson D, Mandelblatt JS, Taylor KL. Development of Decision-Support Intervention for Black Women with Breast Cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(1):62–70. doi: 10.1002/pon.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard VB, Figueiredo M, Cañar J, Goodman M, Caicedo L, Kaufman A, Norling G, Mandelblatt J. Latina a LatinaSM: Developing a Breast Cancer Decision Support Intervention. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:383–391. doi: 10.1002/pon.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A. Focusing on the Forest, Not Just the Tree: Cultural Strategies for Combating AIDS. MICA Communications Review. 2003;1(1):21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sofolahan YA, Airhihenbuwa CO. Childbearing Decision Making: A Qualitative Study of Women Living with HIV/AIDS in Southwest Nigeria. AIDS Research and Treatment 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/47806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofolahan Y, Airhihenbuwa CO. Cultural Expectations and Reproductive Desires: Experiences of South African Women Living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) Health Care for Women International. 2013;34(3–4):263–280. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.721415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofolahan Y, Airhihenbuwa CO, Makofane D, Mashaba E. “I Have Lost Sexual Interest…”—Challenges of Balancing Personal and Professional Lives among Nurses Caring for People Living with HIV and AIDS in Limpopo, South Africa. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2010;31(2):155–169. doi: 10.2190/IQ.31.2.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood S, Pridham K, Brown L, Clark T, Frazier W, Limbo R, Schroeder M, Thoyre S. Infant Feeding Practices of Low-Income African American Women in a Central City Community. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 1997;14(3):189–205. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn1403_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. An Educational Intervention of Hypertension Management in Older African Americans. Ethnicity and Disease. 2000;10:165–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westmaas AH, Kok G, Vriens P, Götz H, Richardus JH, Voeten H. Determinants of Intention to Get Tested for STI/HIV among the Surinamese and Antilleans in the Netherlands: Results of an Online Survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:961. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Garces IC, Bandura L, McGuire AA, Scarinci IC. Design and Evaluation of a Theory-Based, Culturally Relevant Outreach Model for Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening for Latina Immigrants. Ethnicity and Disease. 2012;22:274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MS, Amoateng P. Knowledge and Beliefs about Cervical Cancer Screening among Men in Kumasi, Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2012;46(3):147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yick AG, Oomen-Early J. Using the PEN-3 Model to Plan Culturally Competent Domestic Violence Intervention and Prevention Services in Chinese American and Immigrant Communities. Health Education. 2009;109(2):125–139. doi: 10.1108/09654280910936585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]