Abstract

The shear stresses derived from blood flow regulate many aspects of vascular and immunobiology. In vitro studies on the shear stress-mediated mechanobiology of endothelial cells have been carried out using systems analogous to the cone-and-plate viscometer in which a rotating, low-angle cone applies fluid shear stress to cells grown on an underlying, flat culture surface. We recently developed a device that could perform high-throughput studies on shear-mediated mechanobiology through the rotation of cone-tipped shafts in a standard 96-well culture plate. Here, we present a model of the three-dimensional flow within the culture wells with a rotating, cone-tipped shaft. Using this model we examined the effects of modifying the design parameters of the system to allow the device to create a variety of flow profiles. We first examined the case of steady-state flow with the shaft rotating at constant angular velocity. By varying the angular velocity and distance of the cone from the underlying plate we were able to create flow profiles with controlled shear stress gradients in the radial direction within the plate. These findings indicate that both linear and non-linear spatial distributions in shear stress can be created across the bottom of the culture plate. In the transition and “parallel shaft” regions of the system, the angular velocities needed to provide high levels of physiological shear stress (5 Pa) created intermediate Reynolds number Taylor-Couette flow. In some cases, this led to the development of a flow regime in which stable helical vortices were created within the well. We also examined the system under oscillatory and pulsatile motion of the shaft and demonstrated minimal time lag between the rotation of the cone and the shear stress on the cell culture surface. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013;110: 1782-1793.

Keywords: endothelial cells, cone-and-plate viscometer, Navier–Stokes equations, steady and unsteady flow

Introduction

Shear stress is a potent regulator of homeostasis in the cardiovascular system and a key determinant in atherogenesis. The location of the endothelium at the interface between flowing blood and the tissues of the body makes it ideally positioned to both sense and regulate shear stress-mediated processes. Shear stress, along with other factors, is known to play a role in regulating coagulation, vasomotor tone, and endothelial–immune cell interactions (Hahn and Schwartz, 2009). In part, shear stress modulates endothelial function through the transcriptional regulation of shear sensitive genes, including those for growth factors and cytokines, factors regulating vasomotor tone, and coagulation factors. Shear stresses also regulate the interaction of circulating cells with the endothelium and have been shown to regulate platelet aggregation and the adhesion of circulating leukocytes and tumor cells (Nesbitt et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2012). Consequently, shear stresses regulate the localization and severity of vascular disease (Chatzizisis et al., 2011; Koskinas et al., 2009).

Devices analogous to the cone-and-plate viscometer have been used for many years to recapitulate the flows of the arterial system on endothelial cells (Blackman et al., 2002; Chung et al., 2005; Dewey et al., 1981; Dreyer et al., 2011; Schnittler et al., 1993). Mooney and Ewart first introduced the cone-and-plate configuration for making rheological measurements on non-Newtonian liquids (Mooney and Ewart, 1934). For applications in cell culture, a rotating cone with a small angle is used to create shear on cells adhered to a culture surface. In the idealized case, this configuration creates a uniform shear field on the cultured cells underneath the cone (often termed primary flow). However, when the centrifugal force in the flow becomes significant, circulatory secondary flow is created in the gap region (Cox, 1962; Pelech and Shapiro, 1964). In addition, if the cone does not completely fill the underlying area of the culture well there will interaction between the fluid under the cone and the surrounding fluid outside the cone area.

Several groups have used experimental and mathematical methods to investigate the flow in cone-and-plate devices. Secondary flow has been found to be present at all flow speeds but is negligible at low shear rate under constant angular rotation (Fewell and Hellums, 1977). However, when secondary flow is present it can significantly alter the torque needed to rotate the cone (Sdougos et al., 1984). Cone-and-plate devices have been used to examine the adhesion of immune cells and platelets under physiological shear stress (Nesbitt et al., 2009; Shankaran and Neelamegham, 2001a; Yan et al., 2012). Computational studies have suggested that secondary flow effects can alter the velocity gradients and the direction and magnitude of the wall shear stress at the plate surface (Buschmann et al., 2005; Einav et al., 1994; Sdougos et al., 1984). In addition, these effects can alter the cell–cell collision rate and adhesion of suspended immune cells in cone-and-plate devices (Shankaran and Neelamegham, 2001a, b).

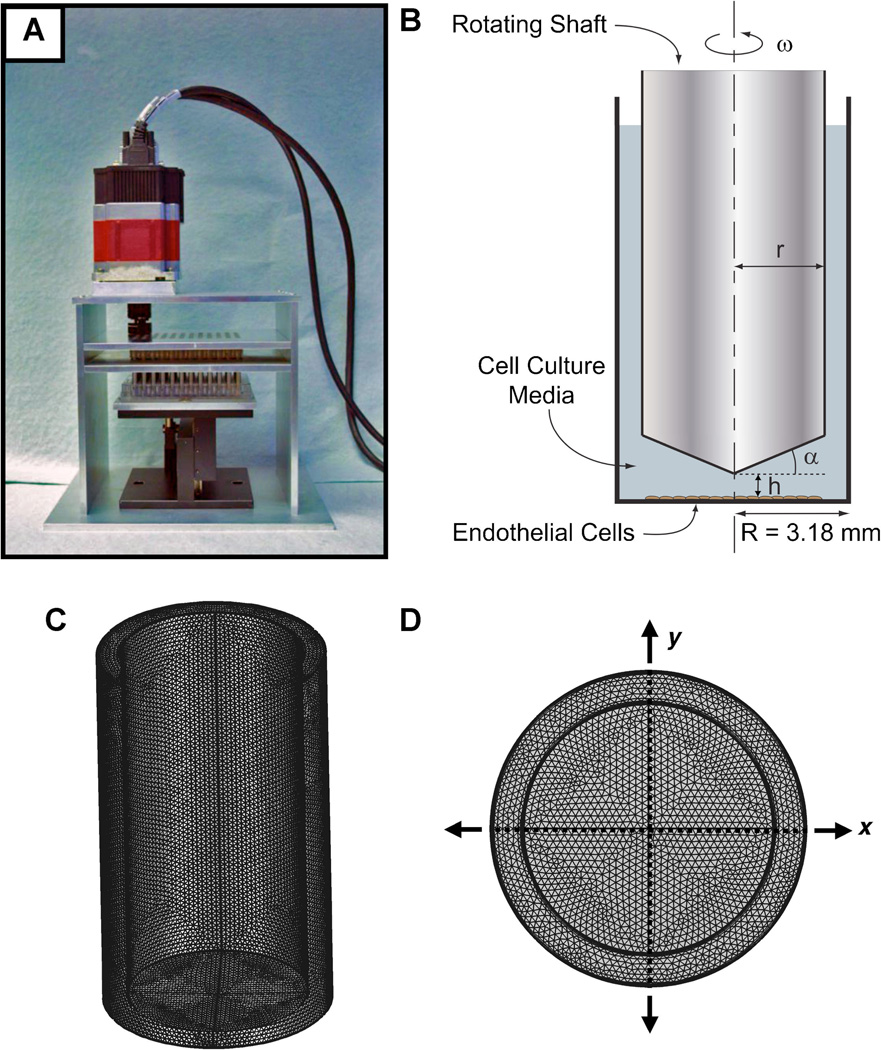

Our group has recently designed and tested a novel device for applying shear stress to cells in culture in the 96-well format. The system works as a 96-cone version of a cone-and-plate device that is designed to fit a standard 96-well culture plate (Fig. 1A). The system enables shear stress/flow to be applied to 96 individual wells of a 96-well culture plate. While many flow systems and bioreactors have been designed to apply flow to cells in culture, the advantage of this system is that it can perform high-throughput studies including those requiring the use of plate readers and automated imaging system. In each well, a shaft with a low-angle cone rotates to create fluid shear stress on the underlying culture plate. The culture plate is held by a custom mounting plate attached to a micropositioning stage that controls the distance between the plate and the cone array.

Figure 1.

High-throughput device for the application of shear stress to cells in the standard 96-well format. The device works by rotating 96 parallel shafts in the wells to create fluid flow. Each shaft has a low-angle cone on the tip. The motion of the shafts is driven by an electric motor and transferred the other shafts through a custom-designed gearbox. A micropositioning stage with a mounting plate for the 96-well culture plate is used to accurately control the position of the culture plate relative to the rotating shafts. B: Diagram of a single well with rotating shaft where h is the height of the cone above the bottom of the plate, α is the angle of the cone, ω is the angular velocity of the spinning shaft/cone, r is the radius of the shaft/cone, and R is the radius of the well. C: Example of meshing used for the simulations. D: End view of meshed system.

In this study, we sought to create a computational model of the system to aid in the design and utilization of the device. Our primary objectives were to understand the effects of the various design parameters to enable us to do the following: (1) determine the optimal design of the cone for use in a standard 96-well culture plate; (2) examine the effects of varying the cone to culture surface distance on the shear stress profile; (3) understand and predict the behavior of the system in unsteady flow conditions; and (4) characterize the shear stresses in the non-cone region to facilitate the use of the system with suspension-cultured cells.

Methods

Numerical Simulation

Comsol Multiphysics (version 4.2a; Comsol, Inc., Burlington, MA) was used for FEM analysis. The Navier–Stokes equations were used to define flow behavior in viscous fluids with the momentum balance included for each component of the momentum vector in all spatial dimensions (White, 2003). Incompressible flow of a Newtonian fluid was assumed with constant density and viscosity. The physical parameters were defined as shown in Figure 1B. The range of the physical parameters examined is included in Table I. No-slip boundary conditions were assumed for all rigid surfaces in the model and a free surface boundary condition was used for the upper fluid surface within the well. The details of the meshing settings for all the simulations are listed in the Supplementary Methods (e.g., meshes are shown in Fig. 1C and D). For steady flow, we solved the equations using generalized minimum residual (GMRES) method. The criteria for convergence was defined by following relation:

ρ|M−1(b − Ax)| < tol · |M−1b|

where tol is the tolerance of 0.001, M is the preconditioner matrix, and ρ is the factor in error estimate (set to 400) for a linear systems of the form Ax = b where the matrix A is positive definite and (Hermitian) symmetric. The details of the time-dependent solver algorithm and convergence criteria have been explained in detail previously (Comsol Multiphysics Reference Manual, p 365–372). We performed a mesh convergence study for the cases in which we observed the formation of vortices within the gap region between the shafts.

Table I.

List of parameters used in the computational model.

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Density, ρ | 1,000 | kg/m3 |

| Dynamic viscosity, µ | 10 × 10−4 | Pa s |

| Well height, H | 10.67 | mm |

| Well diameter, D | 6.35 | mm |

| Shaft diameter, d | 3, 4, 5 | mm |

| Cone angle, α | 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 | Degrees |

| Gap height, h | 1, 10, 100 | µm |

| Angular velocity | ||

| Cone angle of 0.5° | 43.6 (5Pa), 8.7 (1Pa), 4.4 (0.5 Pa) | rad/s |

| Cone angle of 1.0° | 87.3 (5 Pa), 17.5 (1Pa), 8.7 (0.5 Pa) | rad/s |

| Cone angle of 2.0° | 174.5 (5 Pa), 34.9 (1Pa), 17.5 (0.5 Pa) | rad/s |

For the simulation of the Taylor vortices in the gap region at high angular velocity we used a time-dependent solver. Solutions to this type of flow show non-uniqueness that is the end state can be heavily influenced by the acceleration to the final steady-state velocity. We therefore created an acceleration profile similar to that of the motor in our system (accelerating to the final constant angular velocity after ~10 ms). We used time-dependent solver using the Backward Differentiation Formula (BDF) method. The solver absolute tolerance for the simulation was 0.001 leading to variable time stepping between 1.6 × 10−5 and 1.1 × 10−3s. We examined the effects of mesh density on the final solution (Supplementary Fig. 1). We also examined the effect of the tolerance on the solver as a means of altering the fineness of the variable time stepping (Supplementary Fig. 2). Based on these simulations, we chose the final tolerance of 0.001. The final meshing settings listed in the Supplementary Methods were chosen on the basis of these simulations.

Results

Steady Flow Case

Numerical simulations were performed for the constant angular case. We examined shaft angular velocities that with a zero gap height (cone touching the plate) would produce shear stresses of 0.5, 1, and 5 Pa. These values were chosen as they are within the physiological range for endothelial cells and common for use in studies of vascular mechanotransduction (Tzima et al., 2005; Voyvodic et al., 2012). For a cone-and-plate viscometer with no gap, the Reynolds number is defined by Re = R2Ω/v where R is the radius, Ω is the angular velocity, and v is the kinematic viscosity (Fewell and Hellums, 1977). For all these cases, the Reynolds number in the cone region would be <1.2 × 10−4 using the zero gap Reynolds number. With the addition of the maximum gap of the 100 µm, the Reynolds number would be <1.5. Note that the cells in the system are selectively attached and cultured only in the region directly underlying the cone. Within the device, we distinguished several regions of qualitatively different flow. Of primary interest for our application were the shear stresses within the cell culture region on the bottom of the well. Just outside cell culture region, is a transition zone where the cone-and-plate flow shifts to flow surrounding the rotating shaft in the well (parallel shaft region).

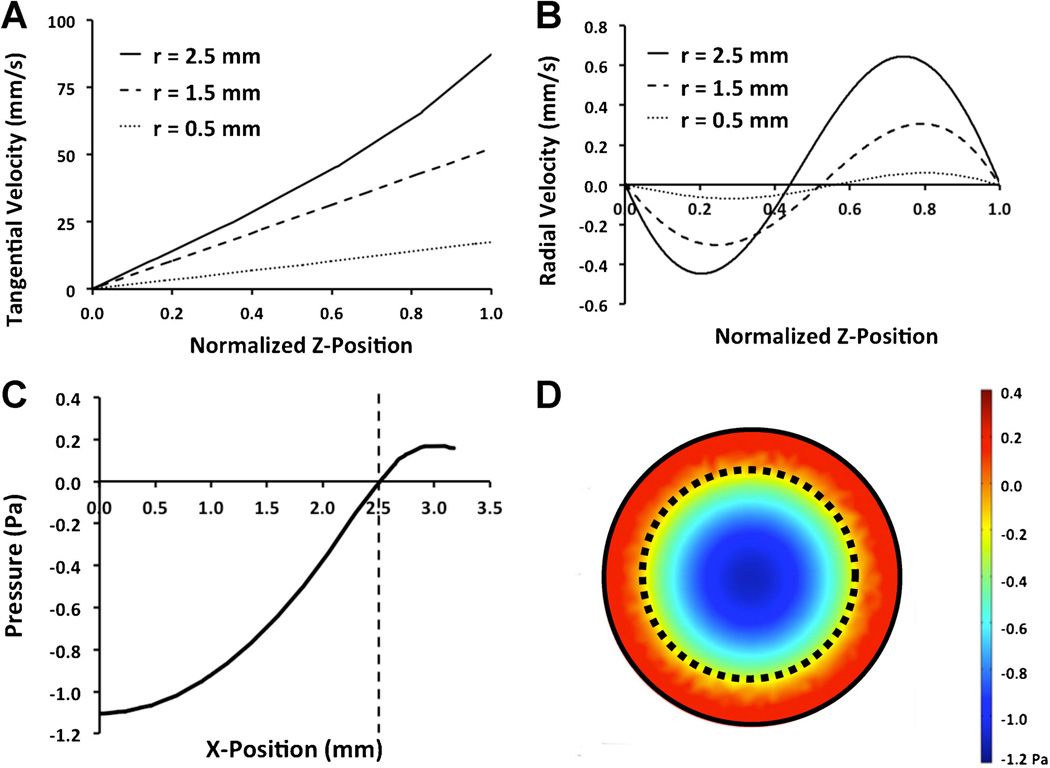

Within the gap region between the plate and rotating cone there was an increase in circumferential tangential velocity when plotted from the cell culture surface to the rotating cone. This was linear within the cone radius with slight nonlinearities at the cone edge (r = 2.5 mm; Fig. 2A). The centrifugal inertia of the fluid causes circulation within the gap region and we observed this in our simulation as an increase in positive radial velocity near the cone and increased negative radial velocity near the culture surface with increasing radial position (Fig. 2B). The gauge pressure was maximally negative at the center of the well and decreased to be nearly zero at the outer edge of the rotating cone (Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2.

Tangential and circumferential velocities within the gap region beneath the cone. A: Tangential velocity at three radial locations in the gap region. The radial velocity was linear with respect to the height from the surface (Z position) for most of the gap region. At the edge of the cone (r = 2.5 mm), there was a slightly non-linear relation with height from the surface. B: The radial velocity profile demonstrated an outward velocity near the rotating cone and an inward velocity closer to the culture surface. C: Gauge pressure at the bottom of the well with a gap height of 100 µm and 5 mm shaft, 2° cone angle at 1 µm gap distance with angular velocity of 174.5 rad/s. D: Visualization of gauge pressure beneath rotating cone.

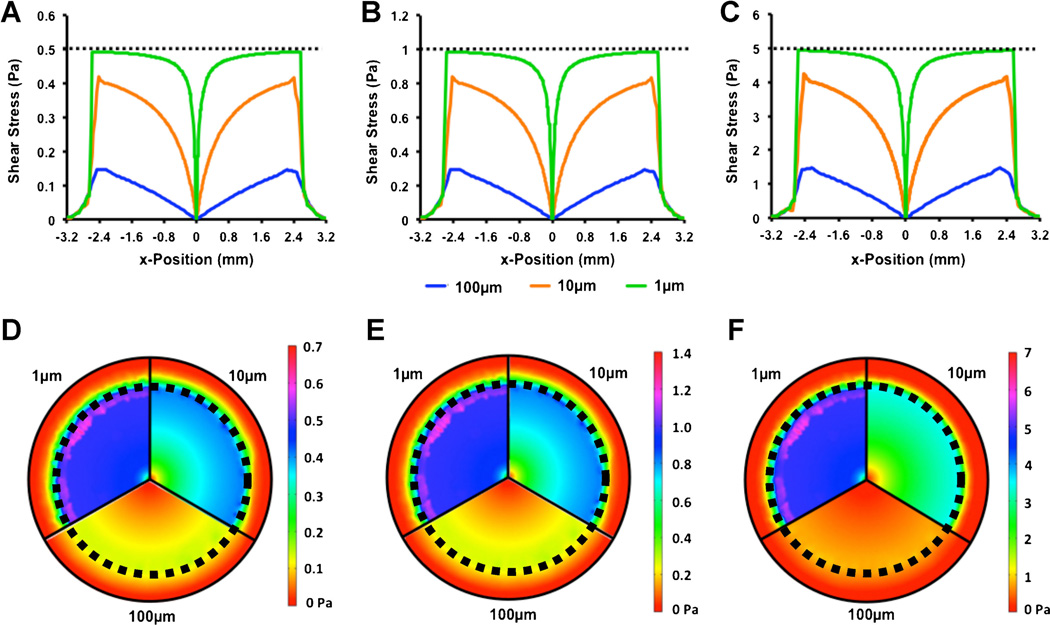

Controlled Shear Stress Gradients Can Be Created by Modifying Cone Angle and Gap Distance

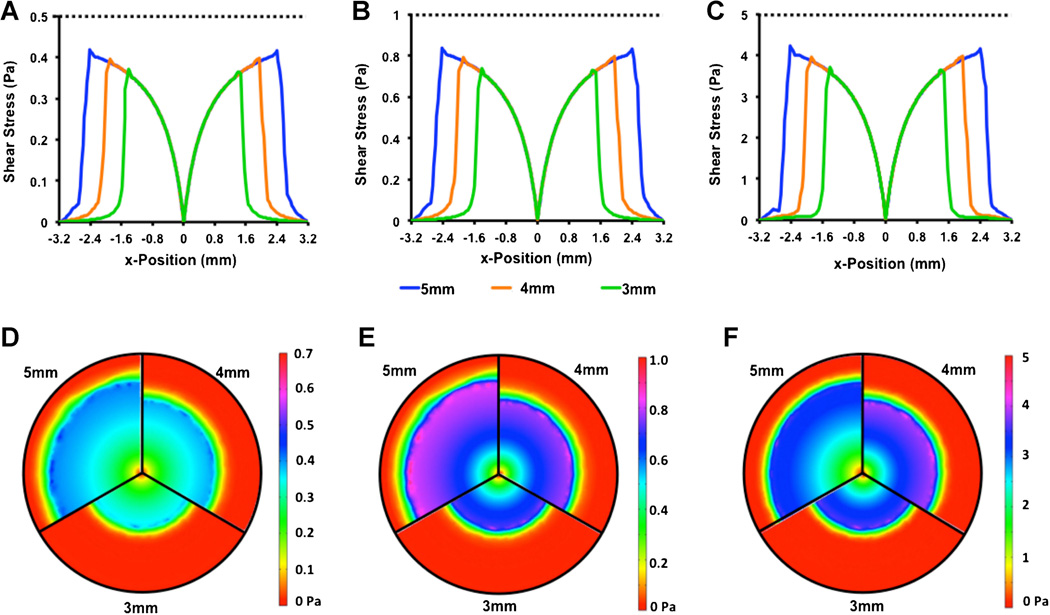

We first examined the effect of altering the distance between the cone and the culture surface. Within the real system, this parameter is easily controllable through a precision micropositioning stage. We performed simulations at an angular velocity that would produce 0.5, 1.0, or 5.0 Pa of shear stress in a zero gap, idealized cone-and-plate system. For each of these cases, we varied the gap distance, termed h, at the distances 1, 10, and 100 mm. We found that at very low gap distance (1 µm) the shear stress was very nearly equal to the ideal cone-plate case for most of the culture region; however, near the tip of the cone there is a region with lower shear stress as the flow approached the axial symmetry point in the center of the well (Fig. 3). At the intermediate distance (10 µm), the cone produces a non-linear shear stress distribution with an average shear stress ranging from zero at the center to about 80% of the ideal shear stress at the cone edge. At larger gap distances the system produced a nearly constant spatial gradient in shear stress in the culture region (R2 = 0.97 for linear fit). If the culture area is reduced to be slightly smaller than the cone (radius of 2.2 mm) to avoid the drop off in velocity at the edge of the cone, the shear stress is linear to a fit of R2 = 0.98 with a maximum of 23.2% of the zero gap shear stress. This finding was consistent across all of the angular velocities tested.

Figure 3.

Effect of gap height on shear stress profiles on cell culture surface. Profiles along a line transecting the bottom of the culture well for a zero gap shear of 0.5 (A, D), 1.0 (B, E), and 5.0 Pa (C, F). Dotted line in (A)–(C) represents the zero gap shear stress. Heat maps (D)–(F) are visual representations of their respective above graph and include slices for each height. Dotted line in (D)–(F) represents the area in which cells are cultured.

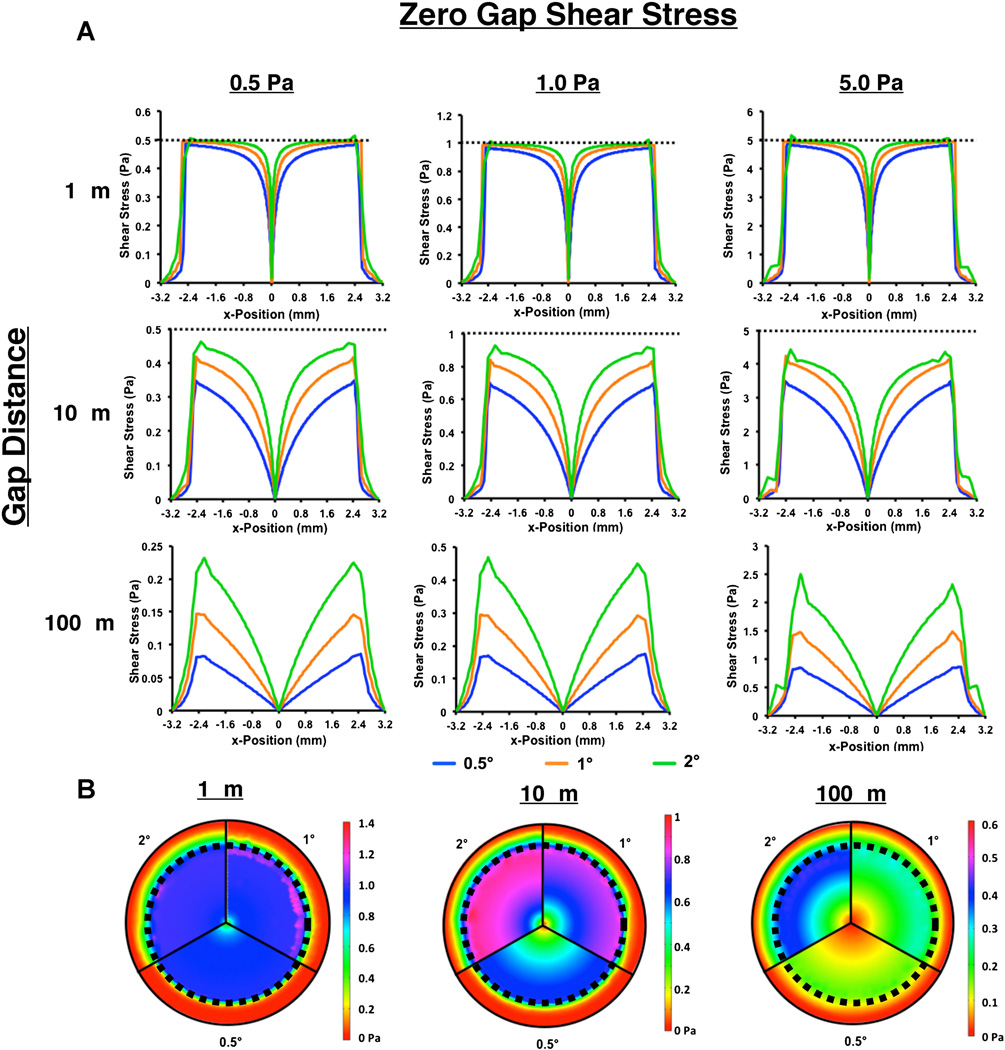

Cone Angle and Gap Distance Alter Shear Stress Gradients Created by Cone Rotation

We next examined the case in which we varied the cone angle and gap distance (Fig. 4A). Within this sensitivity analysis we fixed the zero gap shear stress applied. Thus, for the cone angles 0.5°, 1.0°, and 2.0° the angular velocity varied to be 43.6, 87.3, and 174.5 rad/s, respectively, to maintain constant zero gap shear stress. At low gap distances in the system, there was a relatively flat profile in shear with a drop to zero at the center of the well. As the cone angle is increased the angular velocity was increased to compensate and generate the same zero gap shear stress. Consequently, the lowest angle (and, thus, the lowest angular velocity) deviated most from the ideal flat profile in all cases. At 10 mm distance, the shear stress distribution was non-linear, increasing with angular velocity. A 100 mm, the system generated nearly linear spatial shear stress distribution across the bottom of the plate. The slope of the shear stress gradient increased with increasing cone angle/angular velocity. For a given gap distance, all cases had a similar qualitative shear stress profile that scaled with zero gap shear stress (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effect of cone angle on shear stress profiles on cell culture surface. A: Shear stress values for a line at the bottom of the culture well. The x-axis is located at the center of the bottom of the culture well. Dotted line represents the zero gap shear stress. B: Visualization of shear field on the bottom of culture well for a zero gap shear stress of 1.0 Pa. Dotted line represents the area in which cells are cultured.

Role of Shaft Diameter in Shear Profile Generated on the Culture Surface

In the device, the size of the shaft within the well is dictated in part by the volume of media needed to culture the cells in the plate. A 5-mm diameter shaft allows approximately 128 µL of media to be used for culturing the cells. This is a practically reasonable volume for maintaining cells; however, in some cases, a larger volume may be desired to maintain cells for longer or in the case of applying a suspended culture of cells to an adherent layer of cells. We examined the effect of altering shaft diameter on the shear stress profiles generated in the system (Fig. 5). This analysis demonstrated that the shear profiles essentially followed the curve of the larger shaft for each of the cases with an earlier drop in shear stress at the outer edge of the cone.

Figure 5.

Effect of shaft diameter on shear stress profiles generated from cone rotation. Simulations were run for a zero gap shear stress of 0.5 Pa (A, D), 1 Pa (B, E), and 5 Pa (C, F) and at a gap distance of 10 µm and a cone angle of 1°. The shaft diameter was varied between 3 and 5 mm.

Flow Within the Parallel Shaft Region Spans Multiple Flow Regimes of Taylor-Couette Flow

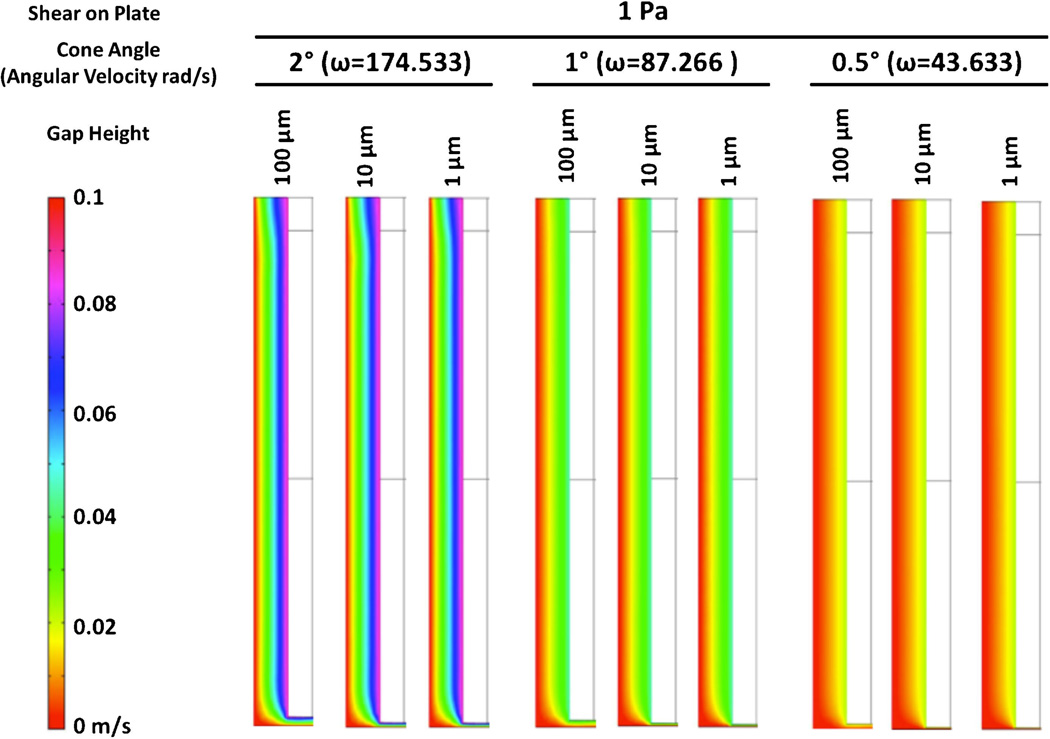

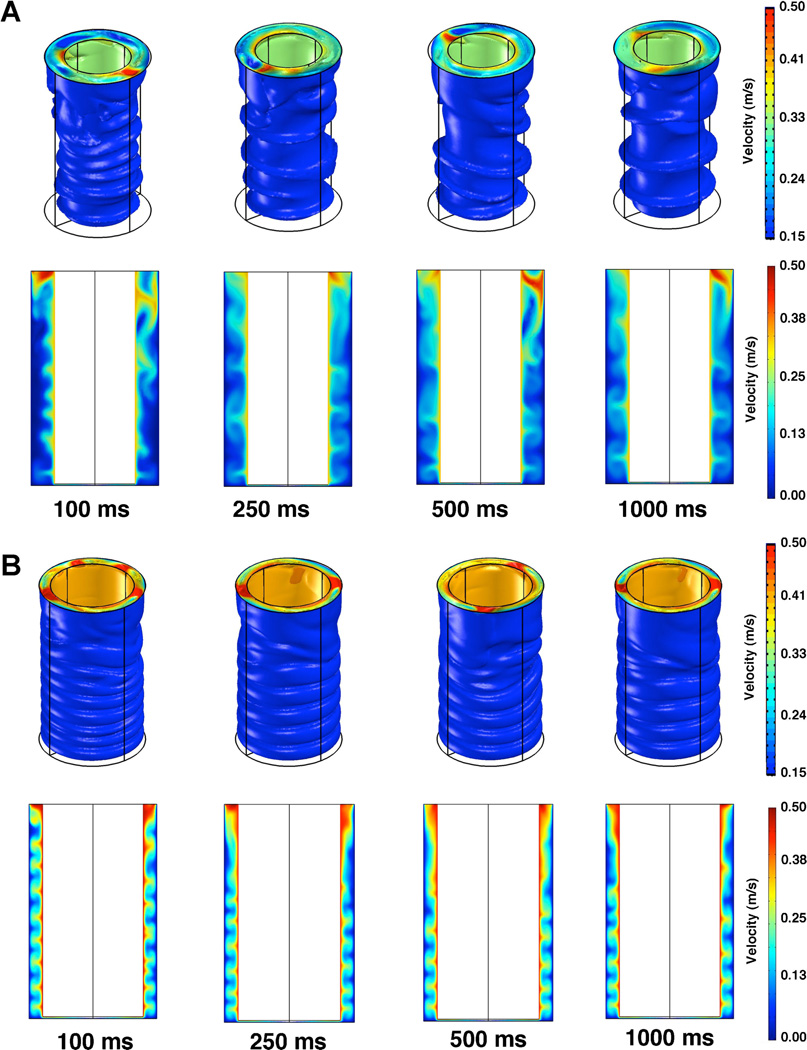

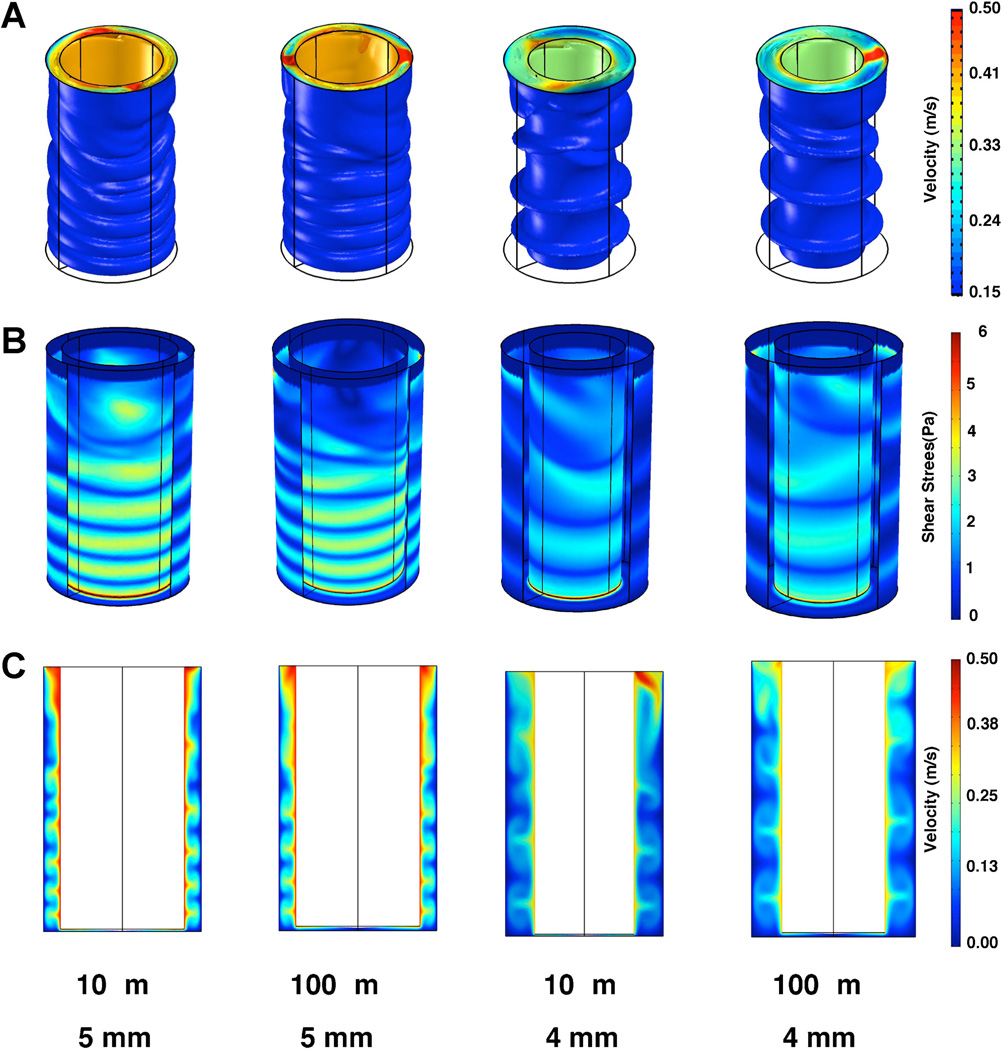

In many experiments, it is desirable to examine not only the effect of shear on an adherent cell type but also the adhesion of a suspended cell type to an underlying layer of adherent cells. This type of assay has been used to examine the interactions between endothelial cells and immune cells, cancer cells, platelets and other cell types (Gutierrez et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Voyvodic et al., 2012). We wanted to understand the fluidic forces that were acting on the suspended cells during flow driven by shaft rotation, in addition to the forces applied to cells directly underlying the adherent cells. We first examined the flow profiles in the parallel shaft and transitional regions of the well under lower shear stress in the case of 0.5 and 1.0 Pa zero gap shear stress. These analyses revealed laminar, Couette flow for a 5-mm shaft under all cone angles and gap distances (Fig. 6). However, at 5 Pa zero gap shear stress the flow regime revealed flow instabilities dependent on the angular velocity. In order to better model these we used a time-dependent model that included the acceleration of the shaft from rest to constant velocity (Figs. 7 and 8). Taylor vortices were observed in these cases and the complex flow was altered somewhat by the gap distance (Fig. 8). In addition, reducing the shaft diameter also markedly altered the qualitative aspect of the flow instabilities within the parallel shaft region and lowered the overall shear stress levels within the parallel shaft region (Fig. 8).

Figure 6.

Flow velocities within the gap region between the rotating shaft and the surrounding culture lack instabilities in the 1 Pa zero gap shear stress case. Flow velocities are shown for constant zero gap shear stress of 1 Pa. The cone surface is on the right side of each cross-sectional view. “Shear on plate” is the ideal case, zero gap shear stress on the culture surface.

Figure 7.

Time sequence of flow after initial acceleration of the shaft from rest. A: Time-dependent simulation of flow for the 4mm shaft case with a 10-µm gap between the cone tip and culture surface. Shown are the velocity isosurfaces for flow and the velocity field on a cut plane passing through the vertex of the cone/center of the plate. All values shown are velocity in m/s. B: Time-dependent simulation of flow for the 5 mm shaft case with a 10-µm gap distance. Shown are isosurfaces and velocity fields on a cut plane through the vertex of the cone.

Figure 8.

Comparison of flow in the shaft gap region under various conditions/designs. A: Velocity isosurfaces (m/s) for flow after 1,000 ms of shaft rotation for the 5 mm diameter shaft case or 4,000 ms of shaft rotation for the 4 mm diameter shaft. B: Wall shear stress (Pa) in the system (part of the outer wall has been hidden to aid visualization). C: Velocity field (m/s) on a cut plane passing through the center of the system.

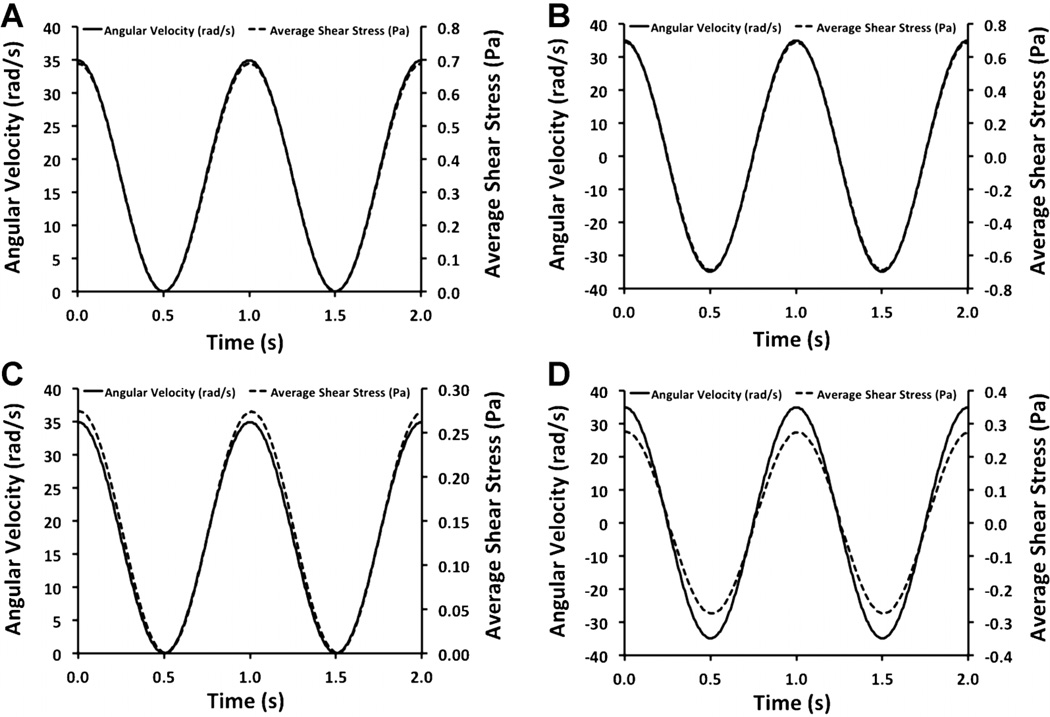

Gap Distance Alters the Delay Between Shaft Motion and Shear Stress in Oscillatory and Pulsatile Flow

Unsteady flow profiles are found in the circulatory system and the profile characteristics have been linked to the formation or protection against atherosclerotic disease (Chatzizisis et al., 2011; Koskinas et al., 2010). We examined the dynamic properties of our system by applying unsteady motion to the shaft and simulating the flow created within on the cell culture surface. We looked at two cases, oscillatory flow in which there is flow reversal during the dynamic cycle and a pulsatile flow profile in which the magnitude of the flow remains positive but varies around a mean value. We found that at low gap distances the motion of the cone and the shear stress in at the culture surface correlated closely (Fig. 9). An analysis of the time delay between peaks found a delay between the shaft motion and the shear stress at the tissue culture surface to be around 2.7 ms for a gap distance of 1 µm for both oscillatory and pulsatile flow (5 mm shaft, 1 Pa shear stress). For a larger gap distance of 100 µm the delay increased to 8.8 ms (5 mm shaft, 1 Pa shear stress; Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Unsteady flow simulations for the cone-and-plate device. A: Average shear stress in cell culture region under pulsatile flow with a gap height of 1 µm. B: Shear stress in cell culture region under oscillatory flow with a gap height of 1 µm. C: Shear stress in cell culture region under pulsatile flow with a 2° cone angle and a 100-µm gap height. D: Shear stress in cell culture region under oscillatory flow a 2° cone angle and 100-µm gap height.

Discussion

We have investigated the three-dimensional flow field generated by a high-throughput system for applying shear stress to cells through a rotating, cone-tipped shaft. Previous studies have examined the idealized cone-and-plate system (Shankaran and Neelamegham, 2001a, b) and a viscometer system with fixed gap (Buschmann et al., 2005). Buschmann et al. used both analytical and numerical approaches to their cone-plate system and found that the series expansion, analytical solutions only held for idealized versions of their system (Buschmann et al., 2005). Our findings extend previous models to the case of a high-throughput system in which the cone is replaced by a cone-tipped shaft with either steady or oscillatory/pulsatile rotation.

Our steady angular velocity simulations support that the cone must be in very close proximity to the plate in order to achieve a uniform shear field over the majority of the cell culture surface. A gap between the cone and surface of 1 µm leads to a region at the center of the well with lower, non-uniform shear stress that is roughly 1 mm in radius with a 28 cone angle. In our studies, the cell culture region was defined as the region immediately beneath the shaft on the cell culture plate. We excluded culturing cells outside this region by patterning the surface to allow cell attachment in this region. Consequently, the non-uniform region at the center of the well would correspond to approximately 4% of cells on the plate that were not under the uniform shear field. Additionally, higher gap distances can be used to generate parabolic and linear spatial shear stress distributions across the cell culture surface. While the vast majority of studies on endothelial mechanotransduction have examined steady, uniform flow, several key studies support that gradients in shear stress may be as important as the overall shear stress in altering endothelial biology. Shear gradients elicit a profoundly different biological response from endothelial cells in comparison to uniform laminar flow. Shear stress gradients do not induce alignment and actin stress fiber formation, as does steady-state flow (Sakamoto et al., 2010). In addition, high shear stress gradients induce migration and proliferation in endothelial cells (Tardy et al., 1997). High shear stress gradients have also been associated with the focal sites of aneurysm formation in human patients. Complex shear gradients also alter the adhesion of tumor cells to the endothelium (Yan et al., 2012) and can induce platelet activation (Nesbitt et al., 2009). Thus, this is a key finding in our study and potentially expands the functionality of the system by demonstrating that it can be used to apply both linear and non-linear spatial shear stress distributions on the bottom of the culture plate. Consequently, our system may provide a high-throughput means to examine controlled gradients in shear stress as well as uniform shear fields. In addition, our dynamic simulations of pulsatile and oscillatory shear stress suggest that the system is capable of generating accurate time varying profiles even with relatively large gap distances. The time delay even at 100 mm of gap distance was less than 10 ms with a profile that closely matched changes in shaft angular velocity. Together with our finding that we can generate linear and non-linear shear stress spatial distributions, these results support that the system would be able to apply unsteady flow with spatial variations in shear stress to cells in culture. Oscillatory and pulsatile flow is known to modulate induce a more pathologic state in endothelial cells (Bao et al., 1999; De Keulenaer et al., 1998; Silacci et al., 2001) and our simulations suggest that these waveforms can be reliable be produced by the system.

The interactions of cells suspended in blood flow are key in the processes of infection, inflammation, thrombosis, and cancer metastasis. In vitro experiments examining the binding of these various cell types with adherent endothelial cells and other cells allow the controlled investigation of these important biological processes. To facilitate the use of our high-throughput system in this regard, we examined the flow in the transition and parallel shaft region of the well over the physically practical ranges of the design parameters for the system. This region is analogous to the Taylor-Couette flow in which a thin layer of fluid is sheared between two counter-rotating cylinders (Dou et al., 2008; Taylor, 1923). This region of flow is less important for studies on adherent cells alone in the cone-and-plate region of the device. However, there is an increased need to examine the interaction of a cell line in suspension an underlying adherent cell layer. Outside of the area directly underneath the cones, these suspended cells types would be exposed to the flow within the parallel shaft and transition regions. These flow regions must therefore be carefully considered when interpreting studies of this type using the system.

A fascinating aspect of our simulations of the flow in the parallel shaft region is that, at moderate Reynolds numbers, the flow becomes structured with patterns of patches of vortex flow (Carlson et al., 1982; Gad-El-Hak et al., 1981). At high shear stress levels, the geometry of the device leads to the formation of structured flow disturbances somewhat similar to the “spiral” or “barber pole turbulence” regime of the Taylor-Couette flow. A detailed examination of the flow regimes present in circular Couette systems has been presented previously (Fewell and Hellums, 1977). Our findings add to this work by demonstrating that the gap distance and cone angle can modify the nature of the flow instabilities. Our results suggest that depending on flow conditions, and particularly at high angular velocities, there are flow instabilities in the circulating media. The effect of these flow instabilities on suspended cell culture is unknown but would likely be undesirable in terms of activation of immune cells or platelets by shear stress within the flow. One practical way to overcome the formation of these instabilities is to decrease shaft diameter. Our findings suggest that this would lead to a reduction in the average flow velocities within the instabilities and the shear gradients that suspended cells would be exposed to during shaft rotation.

Our study has several limitations important to its determination. Due to the small gap and physical configuration of the system it was not possible to experimentally confirm the flow field that are predicted by our models. In addition, the simulation assumes a perfectly flat culture surface as the culture bottom. Cultured endothelial cells are approximately 10–20 microns in diameter with a very flattened profile having a thickness ranging from approximately 3 µm thick in the central perinuclear region to less than 200 nm in the peripheral part of the cell (Milici et al., 1985). In addition, the endothelial cells can form a varying amount of glycocalyx, a glycan-rich layer that interacts with the shear stress and can be ~0.8 µm in vivo but is often far thinner in cultured cells (Van Teeffelen et al., 2007). It is possible, for small gaps the endothelial height/shape and glycocalyx could alter the flow field.

In summary, our work provides a simulation of a physical device with the purpose of creating flow within a standard 96-well culture dish. This is a system could provide a means to perform novel high-throughput studies of shear stress on endothelial function and perform assays simulating circulating cell interactions with the endothelium. Our study has identified several interesting issues/complications with this type of system creating flow in a 96-well format:

The shear stress profile on the cell culture surface is extremely sensitive to gaps between surface and the cone tip. This has the consequence that at large gaps, linear spatial distributions in shear stress can be created and would allow the study of the effects of the spatial gradients using a system of this type.

The system is also capable of performing assays in which a suspended cell type is moved in flow over a surface with adherent endothelial cells. This is a means to simulate the interaction of cells in the blood with the endothelium under flow conditions. Under many shear stress conditions the flow within the shaft region would be well approximated by cylindrical Couette flow.

There is a minimal time delay between the shear applied by the cone motion and the shear on the cells. Combined with our findings that spatially non-uniform shear stress fields can be created at the cell culture surface, this would suggest that our system could apply both temporally unsteady and spatially non-uniform flow.

At the rotational speeds needed to create 5 Pa of shear stress, vortices would present in the flow and this would need to be considered as a factor in assays containing suspended cells.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- Bao X, Lu C, Frangos JA. Temporal gradient in shear but not steady shear stress induces PDGF-A and MCP-1 expression in endothelial cells: Role of NO, NF kappa B, and egr-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19(4):996–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.4.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman BR, Garcia-Cardena G, Gimbrone MA., Jr A new in vitro model to evaluate differential responses of endothelial cells to simulated arterial shear stress waveforms. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124(4):397–407. doi: 10.1115/1.1486468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann MH, Dieterich P, Adams NA, Schnittler HJ. Analysis of flow in a cone-and-plate apparatus with respect to spatial and temporal effects on endothelial cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;89(5):493–502. doi: 10.1002/bit.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DR, Widnall SE, Peeters MF. A flow-visualization study of transition in plane Poiseuille flow. J Fluid Mech. 1982;121:487–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzizisis YS, Baker AB, Sukhova GK, Koskinas KC, Papafaklis MI, Beigel R, Jonas M, Coskun AU, Stone BV, Maynard C, Shi GP, Libby P, Feldman CL, Edelman ER, Stone PH. Augmented expression and activity of extracellular matrix-degrading enzymes in regions of low endothelial shear stress colocalize with coronary atheromata with thin fibrous caps in pigs. Circulation. 2011;123(6):621–630. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CA, Tzou MR, Ho RW. Oscillatory flow in a cone-and-plate bioreactor. J Biomech Eng. 2005;127(4):601–610. doi: 10.1115/1.1933964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DB. Radial flow in the cone-plate viscometer. Nature. 1962;193(4816):670. [Google Scholar]

- De Keulenaer GW, Chappell DC, Ishizaka N, Nerem RM, Alexander RW, Griendling KK. Oscillatory and steady laminar shear stress differentially affect human endothelial redox state: Role of a superox-ide-producing NADH oxidase. Circ Res. 1998;82(10):1094–1101. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey CF, Jr, Bussolari SR, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Davies PF. The dynamic response of vascular endothelial cells to fluid shear stress. J Biomech Eng. 1981;103(3):177–185. doi: 10.1115/1.3138276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou HS, Khoo BS, Yeo KS. Instability of Taylor-Couette flow between rotating cylinders. Int J Therm Sci. 2008;41(11):1422–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer L, Krolitzki B, Autschbach R, Vogt P, Welte T, Ngezahayo A, Glasmacher B. An advanced cone-and-plate reactor for the in vitro-application of shear stress on adherent cells. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;49(1–4):391–397. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einav S, Dewey CF, Hartenbaum H. Cone-and-plate apparatus: A compact system for studying well-characterized turbulent flow fields. Exp Fluid. 1994;16(3/4):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fewell ME, Hellums JD. The secondary flow of Newtonian fluids in cone-and-plate viscometers. Trans Soc Rheol. 1977;21:535–565. [Google Scholar]

- Gad-El-Hak M, Blackwelder RF, Riley JJ. On the growth of turbulent regions in laminar boundary layers. J Fluid Mech. 1981;110:73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E, Petrich BG, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH, Groisman A, Kasirer-Friede A. Microfluidic devices for studies of shear-dependent platelet adhesion. Lab Chip. 2008;8(9):1486–1495. doi: 10.1039/b804795b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn C, Schwartz MA. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):53–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinas KC, Chatzizisis YS, Baker AB, Edelman ER, Stone PH, Feldman CL. The role of low endothelial shear stress in the conversion of atherosclerotic lesions from stable to unstable plaque. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24(6):580–590. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328331630b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinas KC, Feldman CL, Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Maynard C, Baker AB, Papafaklis MI, Edelman ER, Stone PH. Natural history of experimental coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling in relation to endothelial shear stress: A serial, in vivo intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2010;121(19):2092–2101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Slattery MJ, Wagner D, Simon SI, Dong C. Hydrodynamic shear rate regulates melanoma-leukocyte aggregation, melanoma adhesion to the endothelium, and subsequent extravasation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36(4):661–671. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9445-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Loutherback K, Liao D, Yeater D, Lambert G, Estevez-Torres A, Sturm JC, Getzenberg RH, Austin RH. A microfluidic device for continuous cancer cell culture and passage with hydrodynamic forces. Lab Chip. 2010;10(14):1807–1813. doi: 10.1039/c003509b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milici AJ, Furie MB, Carley WW. The formation of fenestrations and channels by capillary endothelium in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(18):6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney M, Ewart RH. The conicylindrical viscometer. Physics. 1934;5(11):350–354. [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt WS, Westein E, Tovar-Lopez FJ, Tolouei E, Mitchell A, Fu J, Carberry J, Fouras A, Jackson SP. A shear gradient-dependent platelet aggregation mechanism drives thrombus formation. Nat Med. 2009;15(6):665–673. doi: 10.1038/nm.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelech I, Shapiro AH. Flexible disk rotating on a gas film next to a wall. J Appl Mech. 1964;31(4):577–584. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto N, Saito N, Han X, Ohashi T, Sato M. Effect of spatial gradient in fluid shear stress on morphological changes in endothelial cells in response to flow. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;395(2):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittler HJ, Franke RP, Akbay U, Mrowietz C, Drenckhahn D. Improved in vitro rheological system for studying the effect of fluid shear stress on cultured cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(1 Pt 1):C289–C298. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.1.C289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sdougos HP, Bussolari SR, Dewey CF. Secondary flow and turbulence in a cone-and-plate device. J Fluid Mech. 1984;138:379–404. [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran H, Neelamegham S. Effect of secondary flow on biological experiments in the cone-plate viscometer: Methods for estimating collision frequency, wall shear stress and inter-particle interactions in non-linear flow. Biorheology. 2001a;38(4):275–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran H, Neelamegham S. Nonlinear flow affects hydrodynamics and neutrophil adhesion rates in cone-plate viscometers. Biophys J. 2001b;80(6):2631–2648. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76233-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silacci P, Desgeorges A, Mazzolai L, Chambaz C, Hayoz D. Flow pulsatility is a critical determinant of oxidative stress in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2001;38(5):1162–1166. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy Y, Resnick N, Nagel T, Gimbrone MA, Jr, Dewey CF., Jr Shear stress gradients remodel endothelial monolayers in vitro via a cell proliferation-migration-loss cycle. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(11):3102–3106. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GI. Stability of a viscous liquid contained between two rotating cylinders. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser A. 1923;223:289–343. [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, Cao G, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437(7057):426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Teeffelen JW, Brands J, Stroes ES, Vink H. Endothelial glycocalyx: Sweet shield of blood vessels. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17(3):101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyvodic PL, Min D, Baker AB. A multichannel dampened flow system for studies on shear stress-mediated mechanotransduction. Lab Chip. 2012;12(18):3322–3330. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40526a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FM. Fluid mechanics. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yan WW, Cai B, Liu Y, Fu BM. Effects of wall shear stress and its gradient on tumor cell adhesion in curved microvessels. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2012;11(5):641–653. doi: 10.1007/s10237-011-0339-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.