Abstract

Objectives

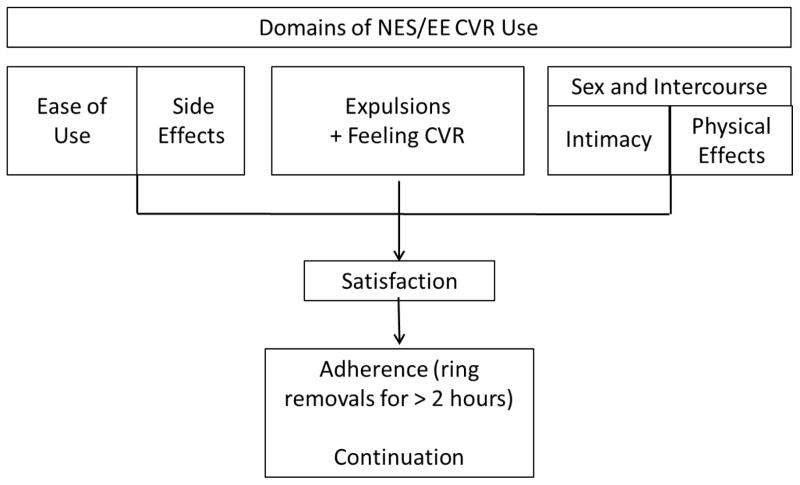

Develop and test a theoretical acceptability model for the Nestorone®/ethinyl estradiol (NES/EE) contraceptive vaginal ring (CVR); explore whether domains of use within the model predict satisfaction, method adherence and CVR continuation.

Study Design

Four domains of use were considered relative to outcome markers of acceptability, i.e. method satisfaction, adherence, and continuation. A questionnaire to evaluate subjects’ experiences relative to the domains, their satisfaction (Likert scale), and adherence to instructions for use was developed and administered to 1036 women enrolled in a 13-cycle Phase 3 trial. Method continuation was documented from the trial database. Stepwise logistic regression (LR) analysis was conducted and odds ratios calculated to assess associations of satisfaction with questions from the 4 domains. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the association of satisfaction with outcome measures.

Results

A final acceptability model was developed based on the following determinants of CVR satisfaction: ease of use, side effects, expulsions/feeling the CVR, and sexual activity including physical effects during intercourse. Satisfaction was high (89%) and related to higher method adherence [OR 2.6(1.3,5.2)] and continuation [OR5.5(3.5, 8.4)]. According to the LR analysis, attributes of CVR use representing items from the 4 domains — finding it easy to remove, not complaining of side effects, not feeling the CVR while wearing it, and experiencing no change or an increase in sexual pleasure and/or frequency — were associated with higher odds of satisfaction.

Conclusion

Hypothesized domains of CVR use were related to satisfaction, which was associated with adherence and continuation. Results provide a scientific basis for introduction and future research.

Keywords: hormonal contraception, long-acting delivery system, user controlled, vaginal ring, acceptability model, continuation, future research, method introduction

Introduction

The Population Council has developed a long-acting reversible contraceptive vaginal ring (CVR) containing ethinyl estradiol (EE), and Nestorone® (NES), a new investigational synthetic progestin. It is designed to release 150 μg NES and 15 μg EE daily and prevent pregnancy when used continuously on a 21-day-in/7-day-out cyclic regimen [1, 2]. This long-acting CVR is controlled by the woman, can be used for 13 cycles, and does not require trained healthcare provider services for insertion or removal. Refrigeration is unnecessary prior to dispensing or during periods of non-use. These design features suggest the NES/EE CVR can address common family planning access and service delivery issues that are especially pronounced in low resource settings. It has the potential to be an important new method in regions with a high unmet need for contraception [3–6]. Acceptability research, however, must be conducted to understand aspects of use affecting utilization, and is an integral component of planning for introduction [7–10].

As a broad concept in the field of contraception, acceptability is influenced by product attributes affecting users’ experiences. Frequently it is assessed by asking about method satisfaction [11–15]. Actual experiences with the product must be identified and explored to identify specific factors influencing satisfaction (11). Accordingly we developed a theoretical model of acceptability for the NES/EE CVR and tested whether domains of use predicted satisfaction, and consequently whether satisfaction was associated with adherence to instructions for use and study continuation. We anticipated that information gained from testing the model could clarify important aspects for introduction and counseling users of this method.

Methods

2.1. Developing a Model of NES/EE CVR Acceptability

An examination of information published during early development of the NES/EE CVR, discussions with investigators, and a literature review on usage of other vaginal rings and contraceptives [7,8,11,12,15–18] facilitated identification of 4 domains associated with use. These domains were hypothesized to be determinants of satisfaction, which could affect adherence to the prescribed 21/7 day regimen, and continuation of use.

The first proposed domain was ease of use, which included a woman’s comfort level with ring insertion/removal and ability to remember the 21/7 day regimen [2, 3, 17, 18]. Earlier reports describing vaginal ring use revealed that partial or complete expulsions can occur during various activities [16–18], and that some women feel or are aware of the CVR during everyday routines. Experiences related to expulsions or feeling the ring, therefore, represented a second domain.

The CVR’s effect on sexual activity for both women and their partner(s) was identified as a third domain. Results from other vaginal ring studies indicate that some women and their male partners feel the ring during intercourse [18–22]. We questioned if such awareness altered aspects of intimacy (sexual pleasure and frequency). The fourth domain was perceived side effects. Since the CVR contains two steroidal hormones, it was expected that side effects could affect satisfaction and consequently continuation/discontinuation, as has been reported for other combined hormonal contraceptives [11, 15, 23,24].

2.2. Development of an instrument to operationalize the model

We constructed a questionnaire to capture the four proposed domains of CVR use. Ease of use was captured via questions on ease of inserting, removing, washing and remembering to remove/re-insert the CVR on schedule. Expulsions were analyzed by questions about feeling or expelling the CVR, and frequency of expulsions. The sexual activity domain focused on changes in sexual frequency and pleasure. We asked whether women and/or their partners felt the CVR during intercourse, and whether any awareness of the CVR during sexual activity altered the woman’s sexual experience. Information about side effects was obtained from a question regarding what women disliked the most about the CVR.

The questionnaire also captured information about the model’s outcomes: satisfaction and method adherence. Subjects’ reports of satisfaction were measured by a five-level Likert item question “How satisfied are you with the ring as a form of contraception?” Method adherence was captured with a self-reported question about CVR removals >2 hours during the most recent 21 days of CVR use. The continuation outcome was obtained from the final database of a pivotal Phase 3 NES/EE CVR clinical trial that included the acceptability study.

Additionally, we used the questionnaire to capture several background items potentially related to domains in the conceptual model, i.e. prior use of tampons and hormonal contraceptives including a vaginal ring. We also asked what participants liked and disliked the most about the NES/EE CVR.

2.3. Administering the Questionnaire

Administration of the acceptability questionnaire was integrated into protocol activities of the NES/EE CVR clinical trial, which was conducted at 12 sites (in Latin America, the US, Europe and Australia) from 2006–2009. The protocol was approved by the Population Council’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and each site’s IRB or Ethical Committee. All participants provided informed consent and were advised about what to expect when using the CVR, including possible side effects. They were instructed on CVR insertion/removal, including guidance to insert the ring towards the back of the vagina so they were unaware of its presence. Participants were instructed to keep the CVR in place for the full 21 days, and cautioned that any removals during that time should be <2 hours. They were given a small case for storage during the 7- day ring-out period and advised they could wash the CVR with warm water and mild soap upon removal.

Questionnaires were translated into each site’s local language, administered by trained staff at the beginning of the 3rd 28 day cycle, and again after 13 cycles or at study discontinuation. Initially all questionnaires were administered by face-to-face interviews (FTF). Following a protocol amendment, women at 7 study sites were randomized to receive either FTF or audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) for an embedded methodological experiment related to disclosure of sensitive information [25].

2.4. Assessing the questionnaire and evaluating the model

Fifteen questionnaire items pertained to the four domains and were used for the analysis. Responses obtained during the 3rd cycle assessment were analyzed according to the theoretical model. A factor analysis was conducted to identify underlying factors driving covariation among questionnaire responses [26]. The number of factors selected from this process was based on a review of Eigenvalues and a plateau of the percent variation explained. For each question, its highest loading (correlation) on any factor in the factor pattern matrix (with orthogonal rotation) was noted. Each emergent factor was characterized by the questions with their greatest loading on that factor.

A bivariate analysis to identify associations of question responses with satisfaction was conducted using Fisher’s exact test. Subjects who indicated they were “highly satisfied” or “satisfied” with the CVR were considered satisfied; all others were considered dissatisfied. Responses to other questionnaire items were collapsed as favorable or unfavorable in relation to satisfaction, with missing responses conservatively grouped as unfavorable. For example, a “don’t know” response to the question on change in sexual frequency was grouped with a response of decrease, and considered unfavorable. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of satisfaction for favorable vs. unfavorable outcomes were computed. We then performed stepwise logistic regression (LR) to determine which questions were predictors of satisfaction. The a priori p-value for entry was 0.20 and the p-value to remain in the model was 0.05. We used the Hosmer-Lemeshow test to assess the goodness of fit for the LR model; the model fits the data if the p value is > 0.05[27].

In accordance with the theoretical model, Fisher’s exact test was used to compare satisfaction with outcome measures, i.e. adherence, and continuation through the end of the study. ORs and the 95% CIs were computed. To better understand drivers of satisfaction, we also examined responses to questions about what women liked and disliked the most about the CVR by satisfaction. No adjustment for simultaneous multiple comparisons were made. All analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2 statistical software.

Results

Questionnaires were administered and completed at cycle 3 by 1,036 of the 1,135 enrolled subjects (91%). Our analyses incorporated data from 905 of these subjects; 706 who completed the study and 199 who discontinued early due to a reason identified with CVR use. Excluded from the analysis were 84 subjects who discontinued early due to non-ring use reasons, e.g. relocated, and 47 who were lost to follow-up.

3.1. Demographics and background information of study participants

Demographic and background characteristics are summarized in Table 1 overall and by satisfaction. A total of 806 (89%) of the women reported that they were satisfied with the CVR as a form of contraception. Marital status and prior use of tampons were the only items with significant differences between women who were satisfied with the CVR and those who were not. Satisfaction rates by country were uniformly high and ranged from 84–95%. (Table 2) and was statistically different among the 8 countries.

Table 1.

Demographic and background characteristics

| Patient Satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied (N=806) | Dissatisfied (N=99) | Total (N=905) | p-value * | |

| Age, years | 0.6 | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 26 (5.2) | 26 (4.2) | 26 (5.1) | |

| Range | 18–40 | 18–39 | 18–40 | |

|

| ||||

| Race, n (%) | 0.6 | |||

| Caucasian | 649 (80.5) | 76 (76.8) | 725 (80.1) | |

| Black | 38 (4.7) | 8 (8.1) | 46 (5.1) | |

| Asian | 20 (2.5) | 3 (3.0) | 23 (2.5) | |

| Multiracial | 66 (8.2) | 7 (7.1) | 73 (8.1) | |

| Other | 33 (4.1) | 5 (5.1) | 38 (4.2) | |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic, n (%) | 351 (43.5) | 41 (41.4) | 392 (43.3) | 0.7 |

|

| ||||

| Married, n (%) | 232 (28.8) | 16 (16.2) | 248 (27.4) | 0.008 |

|

| ||||

| Education, highest level, n(%) | 0.4 | |||

| College graduate or more | 303 (37.6) | 41 (41.4) | 344 (38.0) | |

| Some college | 198 (24.6) | 29 (29.3) | 227 (25.1) | |

| High school | 225 (27.9) | 23 (23.2) | 248 (27.4) | |

| Grade school | 80 (9.9) | 6 (6.1) | 86 (9.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Parity | 0.5 | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 0.6 (0.95) | 0.6 (0.85) | 0.6 (0.94) | |

| Range | 0–5 | 0–3 | 0–5 | |

|

| ||||

| Gravidity | 0.6 | |||

| Mean (s.d.) | 1.0 (1.32) | 1.1 (1.27) | 1.0 (1.32) | |

| Range | 0–7 | 0–4 | 0–7 | |

|

| ||||

| Previous tampon use, n (%) | 594 (73.7) | 82 (82.3) | 676 (74.7) | 0.047 |

|

| ||||

| Previous hormonal contraceptive use n (%) | 476 (59.1) | 56 (56.6) | 532 (58.8) | 0.9 |

|

| ||||

| Prior use of a vaginal ring n (%) | 144 (17.9) | 18 (18.2) | 162 (17.9) | 0.9 |

P-values are from t-tests (age, parity, gravidity) and Fisher’s exact tests (all others).

Table 2.

Satisfaction by Country

| Patient Satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied (N=806) | Dissatisfied (N=99) | Chi-Square p-value | |

| Country | 0.03 | ||

| USA | 240 (83.9) | 46 (16.1) | |

| Chile | 120 (90.9) | 12 (9.1) | |

| Finland | 102 (94.4) | 6 (5.6) | |

| Brazil | 94 (91.3) | 9 (8.7) | |

| Sweden | 76 (86.4) | 12 (13.6) | |

| Hungary | 70 (94.6) | 4 (5.4) | |

| Australia | 53 (89.8) | 6 (10.2) | |

| Dominican Republic | 51 (92.7) | 4 (7.3) | |

3.2. Factor Analysis Results

Factor analysis was conducted with data from 863 subjects (95%) with non-missing responses to the 15 items analyzed. Four factors emerged from the analysis (Table 3), which explained 73% of the variation. The factors are similar to the theoretical model’s circumscribed domains: ease of use, side effects, sexual activity, and expulsions. The highest loading for side effects was on factor 1, which included ease of use questions. Questions about feeling and removing the CVR during sex fell into factor 2, while changes in sexual frequency and pleasure (intimacy) fell into factor 4. Both of these factors captured the sexual activity domain. Factor 3 was characterized by questions about feeling and expelling the CVR.

Table 3.

Rotated Factor Pattern

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Characterization: | Ease of Use & Side Effects | Sex and Intercourse (Physical Effects) | Expulsion | Sex and Intercourse (intimacy) |

| Cumulative Percent of Variation Explained | 47.9% | 58.3% | 66.4% | 72.8% |

|

| ||||

| Ease of inserting CVR | 0.95 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.04 |

| Ease of removing CVR | 0.95 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Ease of washing CVR | 0.95 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| Ease of remembering CVR removal | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Ease of remembering CVR insertion on schedule | 0.95 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| No Side Effects Reported (on questionnaire) | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Feel CVR during sex | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.43 | −0.12 |

| Partner feels CVR during sex | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.21 | −0.07 |

| Remove CVR before sex | 0.24 | 0.90 | 0.11 | −0.01 |

| Any removals for sex: last cycle | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.07 | −0.03 |

| CVR expelled during sex | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.80 | −0.03 |

| Feel CVR while wearing | 0.45 | 0.17 | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| Frequency of expulsions or feel CVR coming out | 0.51 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.05 |

| Change in frequency of sex | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.86 |

| Change in sexual pleasure | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.86 |

3.3. Association between domains of CVR use and satisfaction

Table 4 summarizes associations between the 15 questions that encompassed the four hypothesized domains of CVR use and satisfaction. In the bivariate analysis, 12 questions representing all domains were significantly associated with satisfaction. Six questions were significant in the LR model used to predict satisfaction (P<0.05), which included at least one question from each domain: ease of removing the CVR (ease of use); side effects; feeling the CVR while wearing it (expulsions); and three questions about sex and intercourse (feeling the CVR during sex, change in frequency of sex, and change in sexual pleasure). As expected, favorable attributes of CVR use (finding the CVR easy to remove, not identifying side effects as an aspect of disliking the CVR, not feeling the CVR while wearing it, and not having a change or experiencing an increase in sexual pleasure and frequency) were associated with higher odds of satisfaction. Results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test suggested the model fit the data adequately (P=0.08).

Table 4.

Questionnaire Responses by Satisfaction Related to NES/EE CVR Use

| Domain | Item | Response | Total (N=905) | Satisfied (N=806) | Not Satisfied (N=99) | Bivariate OR (95% CI) | p-value Fisher’s Exact Test | Stepwise Logistic Regression OR (95% CI) | P-value Stepwise Logistic Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of Use | Ease of inserting CVR | Easy/Very easy | 90.8% | 91.3% | 86.9% | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 0.14 | NS | |

| Ease of removing CVR | Easy/Very easy | 88.2% | 89.2% | 79.8% | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) | 0.012 | 1.8 (1.0–3.4) | 0.05 | |

| Ease of washing CVR | Easy/Very easy | 98.2% | 98.4% | 97.0% | 1.9 (0.5–6.8) | 0.16 | NS | ||

| Ease of remembering CVR insertion | Easy/Very easy | 87.6% | 88.8% | 77.8% | 2.3 (1.3–3.8) | 0.003 | NS | ||

| Ease of remembering CVR removal | Easy/Very easy | 85.2% | 78.8% | 86.0% | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 0.020 | NS | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Side Effects | Side effects reported on questionnaire | No | 81.8% | 84.5% | 59.6% | 3.7 (2.4–5.8) | <0.001 | 3.4 (2.1–5.6) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||||||

| Expulsion | CVR expelled during sex | Never | 95.1% | 95.5% | 91.9% | 1.9 (0.8–4.2) | 0.13 | NS | |

| Feel CVR while wearing | No | 70.7% | 73.3% | 49.5% | 2.8 (1.8–4.3) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.4–3.5) | 0.001 | |

| Frequency of expulsions or feel CVR coming out | ≤ 1/week or Never | 92.0% | 93.4% | 80.8% | 3.4 (1.9–6.0) | <0.001 | NS | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Sex and Intercourse | Feel CVR during sex | Never | 70.7% | 73.3% | 49.5% | 2.8 (1.8–4.3) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.2–3.2) | 0.005 |

| Partner feel CVR during sex | Never | 43.9% | 45.7% | 29.3% | 2.0 (1.3–3.2) | 0.002 | NS | ||

| Remove CVR before sex | No | 80.7% | 82.1% | 68.7% | 2.1 (1.3–3.3) | 0.003 | NS | ||

| Any removals for sex: last cycle | No | 83.5% | 85.4% | 68.7% | 2.7 (1.7–4.2) | <0.001 | NS | ||

| Change in frequency of sex | No Change or Increase | 90.7% | 92.4% | 76.8% | 3.7 (2.2–6.3) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.0–3.9) | 0.04 | |

| Change in sexual pleasure | No Change or Increase | 89.7% | 92.2% | 69.7% | 5.1 (3.1–8.5) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.3–4.6) | 0.004 | |

The domain with the highest OR in relation to satisfaction was side effects [3.4 (2.1–5.6)], although more than half of dissatisfied women (59/99;60%) did not identify side effects as the feature of CVR use they disliked the most (Table 4). Further investigation revealed that the major driver for dissatisfaction among these 59 women was feeling the ring during sex (37/59;63%) compared to 51% for all dissatisfied women. This finding is consistent with results from the LR model that demonstrated that feeling the CVR during sex was highly associated with dissatisfaction [2.0 (1.2–3.2)] Subject reports about partners feeling the ring during sex was significantly associated with dissatisfaction in the bivariate analysis (p=0.002), but were not significant in the LR model.

3.4. Associations between satisfaction and outcome measures

Satisfied women had more than twice the odds of being adherent (following the 21-day-in/7-day-out cyclic regimen and not removing the CVR > 2 hours in the cycle preceding completion of the questionnaire) compared to dissatisfied women [OR 2.6 (1.3–5.2); Table 5]. Similarly, study continuation was significantly associated with satisfaction [OR 5.5 (3.5–8.4)].

Table 5.

Model Outcome Measures by Satisfaction

| Outcome Measure | Response | Total (N=905) | Satisfied (N=806) | Not Satisfied (N=99) | OR (95% CI) | P-Value Fisher’s Exact Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuation of method through end of study | Yes | 78.0% | 82.0% | 45.4% | 5.5 (3.5, 8.4) | <0.001 |

| CVR removal >2 hours in most recent 21 days of CVR use | No | 94.3% | 95.0% | 87.9% | 2.6 (1.3, 5.2) | 0.009 |

3.5 What women liked or disliked about the NES/EE CVR

Forty percent of all women in the study identified ease of use as the attribute of the CVR they liked most (Table 6). A much higher percentage of satisfied women reported there was nothing they disliked about the CVR compared with dissatisfied women (28% vs. 2%;). In terms of what they liked most, items from three of the model’s domains were ranked higher by satisfied women compared with dissatisfied women, i.e. easy to use, few side effects, good for their sex life. In contrast, dissatisfied women selected problematic items from three domains in a higher proportion than satisfied women; side effects, expulsions (feeling it in/feeling it coming out), and sex and intercourse (partner complaints).

Table 6.

Responses to questions “Please describe what you like the most about using the CVR” and “Please describe what you disliked the most about using the CVR”

| Satisfied (n=806) | Dissatisfied (n=99) | Total (N=905) | Chi-square p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liked the most about the CVR | <0.001 | |||

| Easy to use | 41.1% | 30.3% | 39.9% | |

| Lasts for a year | 21.2% | 27.3% | 21.9% | |

| Few side effects | 13.7% | 9.1% | 13.2% | |

| Effective | 10.9% | 18.2% | 11.7% | |

| Less bleeding | 7.2% | 8.1% | 7.3% | |

| Good for sex life | 3.5% | 0.0% | 3.1% | |

| Nothing | 0.1% | 5.1% | 0.7% | |

| Other | 2.4% | 2.0% | 2.3% | |

|

| ||||

| Disliked the most about CVR: | <0.001 | |||

| Nothing | 27.5% | 2.0% | 24.8% | |

| Having to remove | 10.3% | 5.1% | 9.7% | |

| Inserting the ring | 9.6% | 6.1% | 9.2% | |

| Side effects/Bleeding problems | 14.5% | 37.4% | 17.0% | |

| Feeling it in/Feeling it coming out | 17.4% | 26.3% | 18.3% | |

| Partner complains | 4.7% | 9.1% | 5.2% | |

| Other | 16.0% | 14.1% | 15.8% | |

Discussion

Based upon experiences of women using the NES/EE CVR, an acceptability model was developed in accordance with 4 conceptualized domains of use associated with markers of acceptability, i.e. method satisfaction, adherence to the regimen and method continuation. Factor analysis findings were consistent with the theoretical model’s proposed domains: ease of use, side effects, expulsion and effects on sex and intercourse. Items from each domain were significantly associated with satisfaction, which, in turn, was associated with method adherence and continuation (Figure 1). The fact that there were differences among satisfied and dissatisfied women according to the model’s domains suggests that the domains represent fundamental components of CVR acceptability and identify factors that forecast satisfaction and successful use of this method. Although most women provided favorable responses to questions representing the four domains, the LR model demonstrated that relative to satisfaction, each domain contributes. Satisfaction was unrelated to education level or age, but there were some differences in satisfaction by country.

Figure 1.

Final Model of NES/EE CVR Acceptability

The elements included in the domains have important implications for introduction of the NES/EE CVR. Discussion and/or sensitive questioning and targeted guidance for women who are considering or have begun using this new method are recommended. Soon after women have started using the CVR, practitioners should ask direct questions covering the model’s domains in order to help counsel users about concerns they may have about using the method.

First, the finding that side effects was a major cause of dissatisfaction suggests that potential and current users need to be informed about the possibility of experiencing hormonal or other side effects and given advice about managing specific concerns. Comfort with vaginal touching in order to insert/remove the CVR is another fundamental topic. While most women reported the NES/EE CVR was easy to use, results from the LR model demonstrated that ring removal was associated with dissatisfaction, indicating that directions on removal are as important as insertion, and should be discussed and practiced regardless of prior experiences with vaginal products. Interestingly, in our study satisfaction was unrelated to prior use of a vaginal ring, and previous tampon use had a curious association with dissatisfaction. These findings appear consistent with results from other studies that showed no association between prior use of vaginal rings or tampons and method satisfaction (12), or use of other vaginal products and adherence to a vaginal ring regimen (28).

Anticipatory guidance about the possibility of feeling or expelling the CVR is also necessary. Women who felt the ring while wearing it had twice the odds of being dissatisfied. Accordingly, all ring users should be educated about their vaginal anatomy related to insertion. When positioned in the upper two-thirds of the vagina, above the pubovaginalis muscle sling, the ring sensation should not be perceived due to the visceral innervation of this tissue [29]. With support from informed providers or experienced users, women can practice insertion and acknowledge if they are aware/unaware of its presence. Ongoing guidance should also include discussions about the possibility that expulsions may occur during toileting, other activities that require straining (Valsalva), or during daily activities that include squatting, likely to vary according to local/regional cultural norms.

Finally, potential effects due to the CVR’s presence during sex are an essential topic for initial and follow-up discussions. A large majority (71%) of all subjects reported they never felt the CVR during intercourse, but half of dissatisfied women reported they sometimes or always felt it. Although the issue of partners feeling the ring was not significant in the LR when adjusting for other items including those in the sexual activity domain, it is logical to include this potential issue in comprehensive counseling. Importantly most women, particularly those who were satisfied, reported that the CVR, which is soft and flexible, had no adverse effects on intimacy, i.e. sexual frequency or pleasure. Nevertheless, counseling regarding CVR use that includes male partners may be beneficial, especially in societies where male support is critical for successful introduction of new contraceptives [30].

Additional research with this model and the questionnaire is recommended, including direct participation of male partners, and covering effects of the vaginal ring during sexual activity. Analysis of data from the questionnaire administered during the final study visit for women in the NES/EE Phase 3 trial, and a comparison of results between FTF vs. ACASI techniques are forthcoming. Investigation of NES/EE CVR use in other settings is also recommended, including regions of sub-Saharan Africa where a long acting reversible method under the control of the woman has the potential to be an important new contraceptive option, and where introductory plans are under development following regulatory approvals.

Implications Statement.

Acceptability research is important when introducing a new method of contraception and determining whether it can be a successful option in meeting the reproductive health needs of women and men. This study was designed to test a conceptual model of acceptability and identify factors associated with successful use of a new contraceptive delivery modality. Original research was conducted for this publication.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: National Institute of Health/NICHD 3RO1HD047764-02S2; USAID GPO-A-00-04-00019

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration Number: NCT00263341

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sivin I, Mishell DR, Alvarez F, et al. Contraceptive vaginal rings releasing Nestorone and ethinyl estradiol: a 1-year dose-finding trial. Contraception. 2005;71:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brache V, Payán LJ, Faundes A. Current status of contraceptive vaginal rings. Contraception. 2013;87(3):264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faundes A, Hardy EE, Reyes Q, et al. Acceptability of the contraceptive vaginal ring by rural and urban populations in two Latin American countries. Contraception. 1981;24:393–414. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(81)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darroch J, Sedgh G, Ball H. Contraceptives technologies: Responding to women’s needs. NewYork: Guttmacher Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barot S. In search of breakthroughs: Renewing support for contraceptive research and development. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2013 Winter;16(1) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson HB, Darmstadt GL, Bongaarts J. Meeting the unmet need for family planning; now is the time. The Lancet. 2013 May 18;381(9879):1696–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60999-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy EE, Reyes Q, Gómez F, et al. User’s perception of the contraceptive vaginal ring: a field study in Brazil and the Dominican Republic. Stud Fam Plan. 1983;14:284–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novak A, de la Loge C, Abetz L, van der Meulen EA. The combined contraceptive vaginal ring, NuvaRing: An international study of user acceptability. Contraception. 2003;67(3):187–94. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss J, Nass SJ. New Frontiers in Contraceptive Research: A Blueprint for Action. Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences; 2004. p. 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.RamaRao S, Clark H, Merkatz R, Sussman H, Sitruk-Ware R. Progesterone vaginal ring: introducing a contraceptive to meet the needs of breastfeeding women. Contraception. 2013;88:591–508. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez S, Araya C, Tijero M, Diaz S. Women’s perceptions and experience with the progesterone vaginal ring for contraception during breastfeeding. Reproductive Health Matters. 1997:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafer JE, Osborne LM, Davis AR, Westhoff C. Acceptability and satisfaction using Quick Start with the contraceptive vaginal ring versus an oral contraceptive. Contraception. 2006;73(5):488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creinin MD, Meyn LA, Borgatta L, et al. Multicenter comparison of the contraceptive ring and patch: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:267–77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000298338.58511.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerns J, Darney P. Vaginal ring contraception. Contraception. 2011;83(2):107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisberg E, Fraser IS, Mishell DR, Lacarra M, Bardin CW. The acceptability of a combined oestrogen/progestogen contraceptive vaginal ring. Contraception. 1995;51:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)00005-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roumen FJ, Apter D, Mulders TM, Dieben TO. Efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of a novel contraceptive vaginal ring releasing etonogestrel and ethinyl oestradiol. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(3):463–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahrendt HJ, Nisand I, Bastianelli C, Gomez MA, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Urdl W, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of the combined contraceptive ring, NuvaRing, compared with an oral contraceptive containing 30 micrograms of ethinyl estradiol and 3 mg of drospirenone. Contraception. 2006;74:451–57. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veres S, Miller L, Burington B. A comparison between the vaginal ring and oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:555–63. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000136082.59644.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madden T, Blumenthal P. Contraceptive vaginal ring. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50(4):878–85. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318159c07e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimoni N, Westhoff C. Review of the vaginal contraceptive ring (NuvaRing) J Fam Plan Reprod Health Care. 2008;34(4):247–50. doi: 10.1783/147118908786000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabatini R, Cagiano R. Comparison profiles of cycle control, side effects and sexual satisfaction of three hormonal contraceptives. Contraception. 2006;74:220–23. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brucker C, Karck U, Merkle E. Cycle control, tolerability, efficacy and acceptability of the vaginal contraceptive ring, NuvaRing: results of clinical experience in Germany. Eur J Contracept Reproduct Health. 2008;13(1):31–38. doi: 10.1080/13625180701577122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dieben TO, Roumen FJ, Apter D. Efficacy, cycle control, and user acceptability of a novel combined contraceptive vaginal ring. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(3):585593. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniels K, Mosher WD, Jones J. Contraceptive Methods Women Have Ever Used: United States, 1982–2010. National Health Statistics Report. 2013 Feb 14;:62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewett PC, Mensch BS, Erulkar A. Consistency in the reporting of sexual behavior by adolescent girls in Kenya: A comparison of interviewing methods. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2004;80(Supp 2):ii43–ii48. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. McGraw Hill, Inc; USA: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hosmer David W, Lemeshow Stanley. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montgomery ET, van der Straten A, Cheng H, Wegner L, Masenga G, von Mollendorf C, Bekker L, Ganesh S, Young K, Romano J, Nel A, Woodsong C. Vaginal ring adherence in sub-Saharan Africa: expulsion, removal, and perfect use. AIDS Behav. 2012 Oct;16(7):1787–98. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ballagh SA. Vaginal rings for menopausal symptom relief. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:757–66. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421120-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiser PF, Johnson TJ, Clark JT. State of the art intravaginal ring technology for topical prophylaxis of HIV infection. AIDS Rev. 2012;14:62–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]