Abstract

The present study examined the development of parent use of food to soothe infant distress by examining this feeding practice longitudinally when infants were 6, 12 and 18 months of age. Two measures of feeding to soothe were obtained: parent self-report and observations of food to soothe during each laboratory visit. Demographic and maternal predictors of food to soothe were examined as well as the outcome, infant weight gain. The findings showed that the two measures of food to soothe were unrelated but did reveal similar and unique relations with predictor variables such as parent feeding style and maternal self-efficacy. Only observations of the use of food to soothe were related to infant weight gain. The findings indicate that the two measures of food to soothe may be complementary and that observations of this feeding practice may capture certain relations that are not obtained through the use of self-report.

Keywords: food to soothe, parent feeding practices, infant feeding styles, infant weight gain

Introduction

Although the rates of childhood obesity appear to be plateauing (Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2012) a recent study examining the incidence of obesity from 5 to 14 years of age demonstrated that overweight and obesity at kindergarten rather than later ages substantially increased the risk for later obesity in adolescence. Overweight 5-year-olds were four times more likely to become obese than normal weight 5-year-olds (Cunningham, Kramer, & Narayan, 2014). These data suggest that understanding the early pathways to overweight and obesity by the preschool ages is essential to the prevention of this health outcome, particularly since adolescent obesity is likely to result in adult obesity and its associated medical conditions (Freedman et al., 2005; Guo, Wu, Chumlea, & Roche, 2002).

One pathway toward early childhood obesity is through the method with which parents feed their young children. Parents control child eating; they determine what foods their children eat and when. And while infants and young children can self-regulate their intake of food (e.g., Birch, Johnson, Andresen, Peters, & Schulte, 1991), parent feeding practices can override this innate response such as when parents restrict certain foods, use food to soothe the young child’s negative emotions or distress, or use food to reward or change behavior (Ventura & Birch, 2008). While restrictive parent feeding practices have been firmly established as contributing to child overweight, dietary intake, and eating in the absence of hunger (Birch, Davison, & Fisher, 2003; Fisher & Birch, 1999), less research has been conducted on using food to regulate children’s emotions, particularly across infancy, a period of development that is dependent upon others to soothe distress (Jahromi, Stifter, & Putnam, 2004; Kopp, 1992). Variously labelled emotional feeding (Wardle, Sanderson, Gutherie, Rapoport, & Plomin, 2002), feeding to soothe, (Stifter, Anzman - Frasca, Birch, & Voegtline, 2011), feeding to calm (Baughcum et al., 2001; Evans et al., 2011), or feeding to regulate emotions (Musher-Eizenman & Holub, 2007), this practice has been shown recently to have negative consequences with relation to children’s eating behavior and style. Studies have shown that parents who report using food to soothe (FTS)1 have children who are more likely to develop emotional eating styles (Braden et al., 2014) and have poorer diets, e.g., lower fruit intake/energy dense snacking (Rodenburg, Kremers, Oenema, & van de Mheen, 2013; Sleddens et al., 2014). While the evidence is mounting that FTS contributes to child eating and diet, the few studies that have examined FTS and child weight have produced mixed findings. Some studies found no association between FTS and child weight status (Baughcum et al., 2001; Carnell & Wardle, 2007; Rodenburg et al., 2013) while one showed a positive association (Stifter et al., 2011). Importantly, FTS has been found to be related to eating behaviors that have proven risks for obesity such as eating in the absence of hunger (Blisset, Haycraft, & Farrow, 2010).

Taken together, the evidence, though sparse, indicates that when parents use food to regulate their children’s emotions, the risk for poor or unhealthy diet and eating styles is increased. There are several means by which this parental feeding practice may impact child eating outcomes. Since feeding in childhood is predominantly under the control of the parent, using food in circumstances unrelated to hunger and sustenance may lead to children’s understanding that food has other ‘reward-like’ qualities. Likewise, using food to soothe infant or child distress may promote the association of food with emotional comfort, a characteristic of emotional eaters that is associated with obesity in older children and adults (Braet & Van Strien, 1997; Torres & Nowson, 2007). Consequently, children may learn to rely on external cues, such as the presence of food, or their own emotional distress, rather than relying on internal cues of hunger or satiety. This compromised ability to self-regulate their food intake may put them at risk for overweight. To date, the relationship between FTS and weight status remains unclear. The present study aims to increase our understanding of FTS by examining a number of factors related to this parent feeding practice as well as its effects on change in infant weight.

It is important to note that the majority of the studies examining FTS were cross-sectional and conducted on preschool and school-aged children. Since parent feeding practices are instituted much earlier in life and may change over the course of early childhood, longitudinal studies which examine parent use of FTS are needed. Similarly, most of the evidence has relied on parent report for both the parents’ own feeding practices and their child’s diet or eating style. It is well known that such reports may be biased, influenced by a number of factors including parent and child characteristics. In light of these limitations, a recent report from a working group on parental influences on childhood obesity strongly recommended longitudinal studies and the use of observational methods among other remedies to move the field forward (Baranowski et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2013). Consistent with these recommendations, the current study examined FTS longitudinally across infancy and toddlerhood and utilized both a parent-report and an observational measure of FTS. This developmental period is a particularly important time to examine this feeding practice as parent-child interactions around feeding begin in the first days of life and are known to affect the child’s future eating patterns and obesity risk (Farrow & Blisset, 2006; Savage, Fisher, & Birch, 2007). To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the use of food to soothe longitudinally as well as observationally.

A broader understanding of parent use of food to soothe is furthered by investigating the degree to which demographic and maternal factors contribute to this parent feeding practice. Past research has shown family income or SES to be related to FTS but with mixed results. Several studies have found low income mothers to use FTS (Baughcum et al., 2001; Saxon, Carnell, Van Jaarsveld, & Wardle, 2009) while one study found no relationship (Evans et al., 2011). This null finding is supported by studies using focus groups of both middle and low-income mothers which found both groups to endorse the use of food to soothe (Baughcum, Burklow, Deeks, Powers, & Whitaker, 1998; Sherry et al., 2004). Maternal weight has shown a positive relation with FTS as has maternal eating style with heavier mothers (Wardle et al., 2002) and those who report emotional eating (Snoek, Engels, Janssens, & Van Strien, 2007) to be more likely to use this feeding practice. Likewise, lower parenting self-efficacy has been linked to greater use of FTS in a cross-sectional sample in early childhood (Stifter et al., 2011). Finally, although not specific to FTS, early feeding decisions appear to be related to parenting feeding styles. Several studies have found breastfeeding to be negatively related to a controlling feeding style (e.g., pressuring, restrictive; Blissett & Farrow, 2007; Fisher, Birch, Smiciklas-Wright, & Piccano, 2000; Traveras et al., 2004) and positively related to a responsive feeding style (DiSantis, Hodges, & Fisher, 2013). Likewise, mothers who introduce solid food later reported a more responsive feeding style (DiSantis et al., 2013; Kronborg, Foverskov, & Væth, 2014) whereas mothers who reported more controlling feeding styles introduced solids to their infants earlier (Brown & Lee, 2013). We examined each of these factors in relation to self-report and observations of parent use of food to soothe in the present study.

In summary, the current study measured FTS two ways: through parent self-report and the observation of FTS in the laboratory. We examined these two measures longitudinally from 6 to 18 months of age to test its continuity and stability across early childhood. To increase our understanding of this parent feeding practice, we also examined demographic and maternal factors that may predict FTS. Finally, we investigated the relationship between FTS and weight change.

Methods

Participants

Infant-mother dyads (N = 160; 75 female infants) were recruited as part of a longitudinal study with data collection when the infants were within two weeks of 4, 6, 12, and 18 months of age. The dyads were recruited through birth announcements and a local community hospital in Central Pennsylvania. Criteria for inclusion in the study were mothers’ full-term pregnancy, ability to read and speak English, and maternal age greater than 18 years. The families were primarily Caucasian (n = 152). Mothers averaged 29.66 years of age at the birth of their infant and had at least 2 years of education beyond high school. The majority of mothers were married (n = 131).

The present study includes data from laboratory visits when the infants were 6 (n = 148), 12 (n = 136), and 18 months (n = 136). Primary reasons for study attrition include family relocation and inability to contact families to schedule laboratory visits. There were no systematic differences between the participants who completed all three visits (n = 135) and those who dropped out of the study on the following variables: birth order, birth weight, infant weight at 6 months, maternal weight (BMI), and family income. Mothers who dropped out were slightly less educated (p < .05; M = 13.85 years) than those who remained in the study.

Procedures

This longitudinal study was designed to assess parent use of food to soothe infant distress. Families were initially seen at their homes when infants were 4 months of age. At 6 months, 12 months, and 18 months (infant age) mothers and infants participated in a number of tasks designed to elicit temperament which included arm restraint/toy removal to elicit anger reactivity, presentation of unusual masks to elicit wariness/fear, and a peek-a-boo game to elicit positive reactivity (Gagne, Van Hulle, Aksan, Essex, & Goldsmith, 2011; Stifter, Spinrad, & Braungart-Rieker, 1999). Parents completed a number of questionnaires at all ages including a measure of food to soothe, parent feeding behavior, and parent eating behavior.

The entire lab visit, which was between 60 and 90 minutes in duration, was videotaped from the time the parent and infant entered the lab to their exit and coded for parent soothing strategies including the use of food to soothe infant distress, the focus of this paper.

One aim of the present study was to observe parent use of food to soothe infant distress during the lab visits. Because many of the parents had not instituted solid foods by 6 months, and by 12 months were likely still in the process of being introduced to new foods, no food was provided for the parents. However, at 18 months, a “snack tray” was provided to the parents with the instruction that “because this visit is a bit longer than the previous ones we have prepared a snack tray that you can use, if needed.” The tray included apple slices or banana, cereal bar, string cheese, applesauce, puffs, and a pre-packaged chocolate cake roll. The tray was shown to the mother and any item the mother said her child might be allergic to was removed from the tray. Otherwise, all 6 items were placed on the tray and left on a counter within sight of the child and parent.

Measures

Demographics

Infant (sex, birthweight), feeding (duration of breastfeeding, age solids were introduced), and family (income) factors were gathered through an interview with the parent at entry into the study and updated at the 6, 12 & 18 month visits. Family income was delineated into 7 categories: 1) Less than $10,000; 2) $10,000 – $20,000; 3) $20,000 – $40,000; 4) $40,000 – $60,000; 5) $60,000 – $80,000; 6) $80,000 – $100,000; 7) $100,000+. Maternal height and weight were measured at the 6 and 12 month lab visits and averaged (pregnant women were not included in this variable).

Food to Soothe

Parent use of food to soothe was measured in two ways, through parent report and laboratory observations.

The Food to Soothe Questionnaire (FTSQ), an adaptation of the Baby’s Basic Needs Questionnaire (BBNQ; Stifter et al., 2011) was completed by mothers when their infants were 12 and 18 months of age. The 15-item FTSQ asks parents about their use of food to soothe generally, how likely they were to use it during several different situations, e.g., when driving in a car, when stressed; and whether they used food to soothe when nothing else worked. Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (often). Items from each FTSQ at 12 and 18 months were subjected to an exploratory factor analysis utilizing principal axis factoring extraction with oblimin rotation. Five items were dropped based on the initial analysis due to low item-total correlations, response rate, and communalities. A subsequent factor analysis on the remaining 10 items revealed two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 at 12 months (Eigenvalues − 3.44, 1.73) and 18 months (Eigenvalues − 4.15, 1.54) explaining 43.4% and 49.7% of the variance, respectively. One factor, which we labelled situation-based FTS, comprised the 7 items reflecting situations in which a parent might use food to soothe as well as the general question on food to soothe usage. The second factor, labelled state-based FTS, was comprised of two of the emotional/state reasons (stressed, tired) as well as the item on using food to soothe when nothing else worked. Items were summed and averaged to create the two subscales at each age. Alphas were .74, .73, .79, & .77 for the 12 month situation-based FTS, 12 month state-based FTS, 18 month situation-based FTS and 18 month state-based variables, respectively.

At 6 months, the use of food to soothe was assessed through an interview with the mother. Mothers also rated the frequency of using food to soothe and its effectiveness. Mothers’ answer to the yes/no interview question about whether they used food to soothe their infants’ distress was combined with their rating of its frequency to create a FTS variable at 6 months.

Observations of parent use of food to soothe infant distress were coded across the entire laboratory visit when infants were 6, 12 and 18 months. Coders played a participant’s video recording until they noted the mother feeding the child. The video was stopped and the situation leading up to the feeding was noted including whether the infant was fussy or crying, and the time of the feeding. If mothers used food when their children were fussing or crying, then the parent was noted as having used FTS during the lab visit.

The coding of FTS during the lab visits was defined as any use of sustenance in response to infant fussing or crying. This included breast milk, formula or solid food but did not include the use of water. As noted FTS was conceptualized as the use of food to soothe distress due to reasons other than hunger. In the laboratory situation it was not possible to determine the parents’ motivations for feeding their children. Thus, it was possible that mothers may have interpreted their infants’ crying as signaling hunger. The time the child was last fed before the lab visit, however, was recorded and examined in relation to the use of FTS during the lab visit as a possible covariate.

In summary, coding of the video recordings of the 6, 12 and 18 month lab visits resulted in three yes/no variables – LabFTS6, LabFTS12, LabFTS18, which were used to address the aims of the present study.

Infant Feeding Style

The Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire (IFSQ; Thompson et al., 2009) was completed by mothers to assess maternal feeding style, including their beliefs and behaviors related to feeding infants when their infants were 6 and 12 months of age. All items were rated on a 5-point scale. This questionnaire captures 13 sub-constructs of five traditionally assessed feeding styles: Laissez-Faire, Pressuring, Restrictive, Responsive, and Indulgent. The IFSQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Thompson, Adair, & Bentley, 2013; Thompson et al., 2009).

The feeding style sub-constructs examined in the present study were: Pressuring: Finish (encouraging infants to consume milk or food, regardless of infants’ hunger and satiety cues; α = .75); Pressuring: Cereal (beliefs about whether infants need to eat more and whether putting cereal in an infant’s bottle helps infants feel full or sleep through the night; α = .84); Pressuring: Soothing (the use of food to soothe infant crying; α = .75); Restrictive: Amount (parental control over the amount of milk/food the infant ate; α= .68), Responsive: Satiety (parental awareness and responses to infants’ hunger and satiety cues; α = .67) and Responsive: Attention (quality of the mother-infant interaction during feeding; α = .60). Both Laissez-Faire sub-constructs (Attention and Diet Quality) and the Restrictive: Diet Quality sub-construct were excluded due to Cronbach’s alphas less than .60 or fewer than two items. The four Indulgent sub-constructs were not of interest to the present study and are not considered further.

As the correlations between the 6 month and 12 month assessments were strong (r’s ranged from .43 to .68, all p’s < .001), composite measures of infant feeding style were created by averaging the 6 and 12 month subscales used in the study.

Parent Eating Style

The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (Van Strien, Fritjers, Bergers, & Defares, 1986) assesses adult eating style and was completed by mothers prior to the 12 month lab visit. Three eating styles are captured by this instrument - restrained (e.g., “Do you watch exactly what you eat?” α = .89), external (e.g., “Can you resist eating delicious food?” α = .87), and emotional (e.g., “Do you have the desire to eat when you are irritated?” α = .96). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from “never” (1) to “very often” (5).

Parenting Self-Efficacy

The Parenting Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (Fish, Stifter, & Belsky, 1991) was used to assess parental feelings of competence as a parent, their ability to meet the child’s needs, and parent feelings of the difficulty and need for support in the parenting role. Mothers rated 18 statements on a 6 point scale reflecting the degree to which they agreed with the statement. High scores reflect greater self-efficacy (α = .69). Mothers completed this instrument when their infants were 12 months of age.

Infant Weight

Infant weight and recumbent length were measured at 6, 12, and 18 months of age. Infant weight was measured twice with a Seca 354 Digital Baby Scale (Hanover, MD) and infant length was measured twice with a Seca 416 Infantometer (Hanover, MD). If there was a disagreement of more than 100g for infant weight or 1 cm for infant length, a third measure was taken. The measurements were averaged for the final weight variable. Infant weight and length measurements, as well as the infant’s sex, were used to calculate weight-for-length z-scores using the World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards. These standards have been recommended for use in children younger than 24 months of age (Grummer-Strawn, Reinold, & Krebs, 2010). As rapid weight gain is a robust predictor of childhood and adult obesity (Baird, 2005; Dennison, Edmunds, Stratton, & Pruzek, 2006; Stettler, Kumanyika, Katz, Zemel, & Stallings, 2003), we examined change in infant weight from 6 months to 12 months and from 6 months to 18 months resulting in two weight change variables. A change score was computed by subtracting the 6 month weight-for-length z-score from 12 and 18 month weight-for-length z score such that larger scores reflect greater change across the time period.

Data Analytic Strategy

To examine the interrelationships, stability, and convergence among the parent-report and laboratory observations of FTS, correlations, independent samples t-tests, and Chi-square analyses were conducted. Next, demographic variables (infant sex, infant birth weight, income, maternal BMI, breastfeeding duration, and age introduced to solid foods) and maternal characteristics (infant feeding style, maternal eating style, and self-efficacy) were examined as predictors of parent-report FTS using hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Since the LabFTS variables were dichotomous (yes/no), hierarchical logistic regressions were used to predict LabFTS from the demographic variables and maternal characteristics. The blocks of predictors for both sets of hierarchical regressions were the same: demographic variables were entered in the first block, infant feeding style variables in the second block, maternal eating style variables in the third block, and the maternal self-efficacy variable in the fourth block.

FTS was also examined as a predictor of infant weight gain between 6 and 12 and 6 and 18 months using multiple regression analyses. In order to test for potential covariates that might affect this relationship, correlations and independent samples t-tests were conducted between the demographic and infant weight gain variables. Income was positively related to weight gain from 6 to 12 months, r (134) = .18, p < .05. For weight gain from 6 to 18 months, both birthweight, r (135) = −.20, p < .05, and breastfeeding duration, r (116) = −.18, p < .06, were negatively related to weight gain. Therefore, these variables were entered as covariates in the subsequent analyses where appropriate.

Since it is possible that the amount of time since the infant was last fed prior to arriving for the laboratory visit would be related to observations of FTS, independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine this relationship. Time since the infant was last fed was unrelated to all laboratory observations of FTS (all p’s >.10), so this variable was not considered further.

Lastly, to streamline the analyses, we created a composite parent-reported FTS score at each age by averaging the items from the situation-based and state-based subscales of the FTSQ at 12 and 18 months. The subscales were significantly correlated at both 12 (r = .34, p < .01) and 18 months (r = .46, p < .01). Alphas for the composite parent-reported FTS score were .77 and .83 at 12 and 18 months, respectively. When we conducted separate analyses using the subscales the results were unchanged.

Results

Table 1 contains the descriptives for all the FTS variables. We first examined whether there was continuity across the 12 and 18 month composite score of parent-reported FTS.2 Parent reports of FTS usage at 12 and 18 months were very similar, t (1, 129) = .99, p < .10. Parent-reported FTS was also relatively stable across the age periods. Mothers who reported using FTS at 6 months were more likely to report using FTS at 12 months, r = .24, p < .05, but not at 18 months, r = .15, p > .05. Parent-reported FTS was stable from 12 to 18 months, r = .45, p < .01.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables, maternal characteristics, and infant characteristics

| % or M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Income | ||||

| <) Less than $10,000 | 3.1% | |||

| $10,000 – $20,000 | 6.3% | |||

| $20,000 – $40,000 | 22.5% | |||

| $40,000 – $60,000 | 25% | |||

| $60,000 – $80,000 | 16.3% | |||

| $80,000 – $100,000 | 10.6% | |||

| $100,000+. | 16.3% | |||

| Infant sex | ||||

| Males | 53.1% | — | — | — |

| Females | 46.9% | — | — | — |

| Duration of Breastfeeding (weeks) | 22.6 | 19.9 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Age first began solids (weeks) | 18.1 | 4.8 | 4.00 | 40.0 |

| Maternal weight (BMI) | 28.4 | 6.8 | 16.2 | 53.1 |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||||

| Feeding style | ||||

| Pressure/finish | 2.05 | .57 | 1.00 | 3.57 |

| Pressure/cereal | 1.80 | .75 | 1.00 | 4.10 |

| Pressure/soothe | 2.15 | .68 | 1.00 | 3.67 |

| Restrict/amount | 2.41 | .84 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Response/satiety | 4.52 | .41 | 2.00 | 5.00 |

| Response/attention | 3.16 | .73 | 1.00 | 4.88 |

| Eating style | ||||

| Restrained | 2.57 | .71 | 1.00 | 4.60 |

| External | 3.13 | .69 | 1.44 | 5.00 |

| Emotional | 2.51 | .97 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Self-efficacy | 4.49 | .52 | 3.22 | 5.61 |

| Infant Weight | ||||

| Birthweight (grams) | 120.4 | 18.3 | 69.0 | 178.0 |

| 6–12 month weight change | .06 | .54 | −1.57 | 1.51 |

| 6–18 month weight change | .17 | .54 | −1.20 | 2.33 |

The number of mothers using food to soothe (FTS) during the laboratory visits was consistent from 6 to 12 months of age but increased when the children were 18 months of age with 32% and 31% of mothers feeding their infants when they fussed or cried during the 6 and 12 month lab visits, respectively. The number of mothers using FTS in the lab increased to 46.7% at 18 months. Lab observations of FTS were stable between 6 and 12 months, X2 = 10.12, p =.002, with the standard residual for the yes/yes cell > 1.96. Mothers who fed their 6 month old infants when they cried were more likely to do the same at 12 months. A near significant relationship between 12 and 18 month LabFTS (X2 = 2.50, p =.13) also emerged but the standard residual for the yes/yes cell was not significant.

Convergence between measures of the use of food to soothe

There was very little agreement among the FTS measures. Parent-reported FTS at 6 months was unrelated to laboratory FTS both concurrently and longitudinally. Parents who reported using FTS at 12 months were slightly more likely to use FTS during the laboratory visit at 12 months, t (1,129) = −1.78, p < .10. Parent-reported FTS at 18 months was unrelated to 18 month LabFTS.

Predictors of the use of food to soothe

As noted, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict FTS using all the predictor variables. The demographics were entered in the first block, maternal feeding style in the second block, maternal eating style in the third block, and maternal self-efficacy in the last block. Separate models were run for the three parent-reported FTS measures and the three laboratory measures of FTS. To streamline the results we only report the regression statistics for the final model with all variables included. The model for 6 month parent-rated FTS was significant, F (16, 86) = 2.4, p < .01, explaining 31% of the variance, as was the model for 18 month parent-rated FTS, F (16, 90) = 2.26, p < .01, which explained 29% of the variance. The model for 12 month parent-rated FTS was not significant, F (16, 89) = 1.23, p > .10. For observed FTS in the lab, the 6 month model was near significant, X2 (1, 16) = 24.5, p < .06, whereas the models for 12 month, X2 (1, 16) = 19.2, p > .10, and 18 month LabFTS, X2 (1, 16) = 15.9, p < .10, were nonsignificant.

The results for the multiple regressions on parent-rated FTS can be found in Table 2. Table 3 contains the results for the logistic regression on laboratory observations of FTS. We discuss the findings for the variables forming each block below.

Table 2.

Predicting 6, 12 and 18 month parent-reported Food to Soothe (FTS)

| 6 month FTS |

12 month FTS |

18 month FTS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | R2 | B | SE | R2 | B | SE | R2 | |

| Demographics | .06 | .04 | .05 | ||||||

| Income | .21* | .08 | .06 | .05 | .19+ | .05 | |||

| Infant sex | −.06 | .25 | −.08 | .15 | −.01 | .15 | |||

| Birthweight | .05 | .01 | −.16 | .00 | −.11 | .00 | |||

| Duration of breastfeeding | .21* | .01 | .11 | .00 | −.05 | .00 | |||

| Age first began solids | −.04 | .03 | .06 | .02 | .03 | .02 | |||

| Maternal weight | .09 | .02 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | |||

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||||||

| Feeding style | .26 | .14 | .18 | ||||||

| Pressure/finish | .19 | .25 | .13 | .15 | .07 | .15 | |||

| Pressure/cereal | .19+ | .20 | .15 | .13 | −.03 | .12 | |||

| Pressure/soothe | .21+ | .19 | .09 | .12 | .27* | .12 | |||

| Restrict/amount | −.14 | .17 | .04 | .10 | .11 | .10 | |||

| Response/satiety | .16 | .37 | .13 | .23 | −.07 | .22 | |||

| Response/attention | .01 | .20 | .11 | .13 | .16 | .12 | |||

| Eating style | .28 | .18 | .29 | ||||||

| Restrained | .04 | .17 | .07 | .11 | −.08 | .10 | |||

| Emotional | .20+ | .15 | .14 | .09 | .21+ | .09 | |||

| External | −.13 | .19 | .06 | .12 | .16 | .09 | |||

| Self-efficacy | .21* | .23 | .31 | −.08 | .14 | .18 | −.02 | .13 | .29 |

Note:

- p < .10,

- p < .05,

- p < .01;

R2 reported for each block

Table 3.

Predicting 6, 12 and 18 month laboratory Food to Soothe (FTS)

| 6 month FTS |

12 month FTS |

18 month FTS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | B | SE | OR | B | SE | OR | |

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Income | −.16 | .19 | .85 | .03 | .18 | 1.03 | −.06 | .15 | .95 |

| Infant sex | .31 | .58 | 1.37 | 1.11* | .55 | 3.03 | .20 | .48 | 1.22 |

| Birthweight | −.01 | .01 | 1.00 | −.01 | .01 | .99 | −.20 | .01 | .98 |

| Duration of breastfeeding | −.00 | .04 | 1.00 | −.00 | .01 | 1.00 | −.01 | .01 | .99 |

| Age first began solids | .00 | .06 | 1.00 | .13* | .06 | 1.13 | −.01 | .06 | .99 |

| Maternal weight | .01 | .04 | 1.01 | .06 | .04 | 1.06 | −.04 | .04 | .96 |

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||||||

| Feeding style | |||||||||

| Pressure/finish | −1.71 | .69 | .18 | −.52 | .58 | .59 | .70 | .52 | 2.02 |

| Pressure/cereal | −.25 | .49 | .78 | .20 | .46 | 1.23 | .18 | .41 | 1.19 |

| Pressure/soothe | .57* | .47 | 1.77 | −.20 | .42 | .82 | .52 | .40 | 1.69 |

| Restrict/amount | .01 | .40 | 1.01 | .62 | .38 | 1.85 | −.07 | .34 | .94 |

| Response/satiety | −1.05 | .91 | .35 | 1.12 | .87 | 3.06 | .00 | .72 | 1.00 |

| Response/attention | 1.21* | .55 | 3.34 | .25 | .48 | 1.28 | −.70 | .44 | .50 |

| Eating style | |||||||||

| Restrained | −.49 | .39 | .61 | −.70+ | .40 | .50 | .37 | .35 | 1.44 |

| Emotional | −.37 | .34 | .69 | .40 | .33 | 1.50 | −.10 | .29 | .91 |

| External | .39 | .45 | 1.48 | .13 | .49 | 1.13 | .41 | .39 | 1.51 |

| Self-efficacy | 1.61** | 5.83 | 5.00 | .15 | .49 | 1.15 | .55 | .45 | 1.73 |

Note:

- p < .10,

- p < .05,

- p < .01;

OR – Odds ratio

Demographics

The analyses examining the relationship between family income, maternal weight, infant sex, birthweight, duration of breastfeeding, and the age when solids were first introduced and parent-rated and observed FTS at 6, 12, and 18 months were largely non-significant. The only significant demographic variables to emerge were for 6 month parent-rated FTS and 12 month observed FTS. For parent-rated FTS, mothers with higher family income reported greater likelihood of using FTS as did mothers who breastfed their infants longer (see Table 2). LabFTS at 12 months was related to infant sex and age at which solids were introduced (see Table 3). Mothers who used FTS in the lab were more likely to do so with their sons. They were also more likely to start solids later.

Maternal infant feeding style

Mother reports of their style of feeding their infants was examined as a potential predictor of FTS (see Table 2 & Table 3). A pressuring feeding style (finish, and/or soothe) was positively related to parent-reported FTS at 6 and 18 months. Mothers who reported that they were more likely to pressure their child to finish eating or use food to soothe also endorsed FTS.

Observed FTS in the lab was also related to feeding style. As can be seen in Table 3, contrary to our finding with 6 month parent-rated FTS mothers who endorsed pressuring to finish were less likely to use food to soothe their 6-month-olds in the lab. Similarly, mothers who rated themselves high in response/attention were more likely to endorse FTS at 6 months. There were no significant relationships between maternal feeding style and parent reported or observed FTS at 12 and 18 months.

Maternal eating style

As can be seen in Tables 2 and 3, maternal eating style (restrained, external, emotional) was revealed to be related to parent report of FTS but only at the trend level. Emotional eating style was positively related to both 12 and 18 month parent-reported FTS. Observed FTS was related to 12 month restrained eating style. Mothers who rated themselves as more restrained were less likely to use FTS in the laboratory.

Maternal parenting self-efficacy

Parenting self-efficacy was related to both parent-reported FTS and LabFTS but only at 6 months (see Tables 2 & 3). Contrary to expectation, 6 month parent report and observed FTS were most often used by mothers rated high in self-efficacy.

Food to soothe and infant weight gain

Multiple regression analyses were used to examine the effect of parent-rated and observed FTS on weight gain from 6 to 12 months and from 6 to 18 months controlling for income in the 6–12 month weight gain analyses, and birthweight and breastfeeding duration in the 6–18 month weight gain analyses.

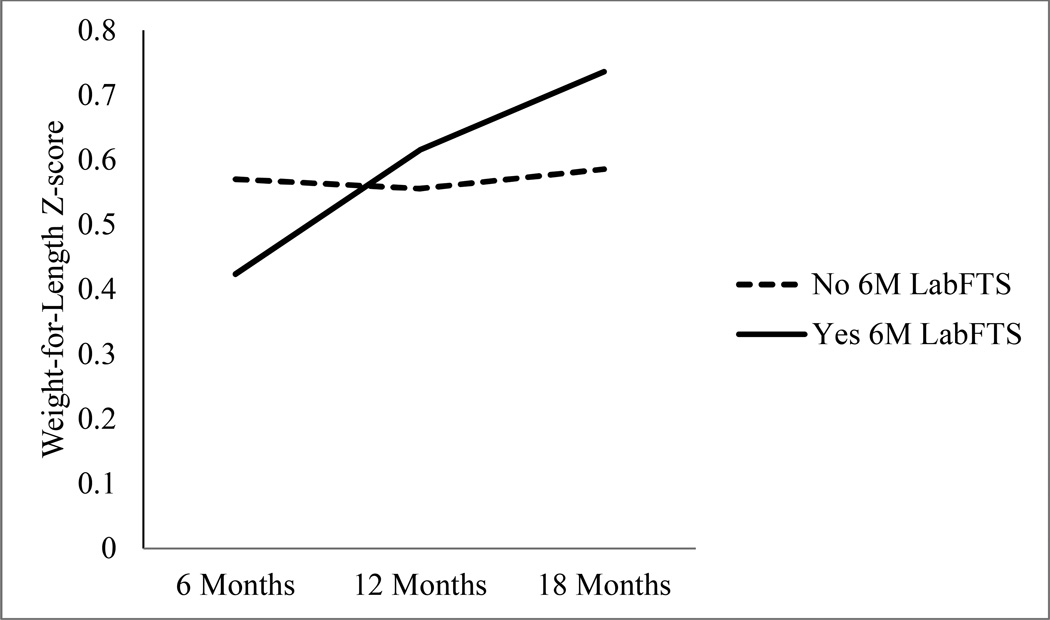

Analyses examining the relationship between parent-rated FTS and weight gain revealed no significant relationships (see Table 4). A different story emerged from the analyses examining LabFTS and weight gain. There were no significant findings for weight gain from 6 to 12 months but the models testing the relationship between LabFTS and 6 to 18 month weight gain were significant. After controlling for birthweight and breastfeeding duration, infants of mothers who used FTS in the lab at 6 months were found to gain more weight from 6 to 18 months than infants of mothers who did not use FTS in the lab, F (3, 114) = 6.42, p < .001, R2 = .15, β = .30, p < .001. A similar trend was revealed for 12 month LabFTS, F (3,114) = 3.66, p < .05, R2 = .09, β = .17, p <.07, and 18 month LabFTS, F (3, 114) = 3.39, p < .05, R2 = .08, β = .17, p < .06. Mothers who also used FTS in the lab when their infants were 12 and 18 months had infants who tended to gain more weight from 6 to 18 months. To illustrate these findings we graphed the 6 month LabFTS data. As can be seen in Figure 1, infants of mothers who used FTS in the lab at 6 months started out lighter but gained weight more rapidly and were heavier by 18 months of age than infants of mothers who were not observed using FTS in the lab.

Table 4.

Predicting infant weight gain from parent-rated and laboratory Food to Soothe (FTS).

| 6–12m weight gain | 6–18m weight gain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| 6m Parent-reported FTS | ||||

| Income | .19* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.17+ | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.17+ | .00 | ||

| FTS | −.09 | .04 | −.01 | .05 |

| 12m Parent-reported FTS | ||||

| Income | .20* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.18* | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.15 | .00 | ||

| FTS | −.07 | .07 | −.11 | .08 |

| 18m Parent reported FTS | ||||

| Income | .23* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.18+ | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.16+ | .00 | ||

| FTS | −.09 | .06 | −.05 | .07 |

| 6m Laboratory FTS | ||||

| Income | .18* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.18* | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.15+ | .00 | ||

| FTS | .08 | 1.0 | .29** | .11 |

| 12m Laboratory FTS | ||||

| Income | .19* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.16+ | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.16+ | .00 | ||

| FTS | −.09 | .10 | .17+ | .11 |

| 18m Laboratory FTS | ||||

| Income | .18* | .03 | ||

| Birthweight | −.15 | .00 | ||

| Breastfeeding duration | −.14 | .00 | ||

| FTS | −.11 | .09 | .17+ | .10 |

Note:

- p < .10,

- p < .05,

- p < .01;

as income was significantly correlated with 6–12m weight gain and birthweight and breastfeeding duration with 6–18m weight gain these variables were controlled for in the respective analysis.

Figure 1.

Weight for length z-scores at 6, 12, and 18 months for infants whose mothers used food to soothe (Yes 6M LabFTS) and those who did not (No 6M LabFTS) during the 6 month laboratory visit.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine in more depth the parent feeding practice of feeding to soothe (FTS) a child’s distress, which has also been termed emotional feeding, feeding to calm, and feeding to regulate emotions. To accomplish this goal we measured FTS longitudinally from 6 to 18 months of age. This allowed for the examination of the development of this feeding practice during a time in which the relationship between parent feeding and child eating is being established. In addition, a longitudinal design can identify the degree of stability of parent use of food to soothe across time. We measured FTS in two ways: 1) using a parent self-report instrument at (infant age) 6, 12 and 18 months that asked several questions about whether and when a parent would use food to soothe their child’s distress. And, 2) by observing the use of FTS in a laboratory setting during which the infant/toddler was likely to become distressed.

Our findings indicate that FTS is relatively stable, with parent report showing more consistency than observations of FTS. Developmentally, mothers reported using similar levels of FTS from 12 to 18 months, however, observed levels of parent use of FTS increased from 12 to 18 months. So even while children decrease the intensity of expressed distress as they develop other means of communicating, mothers increased their use of food to soothe. This finding may be due to the duration, number of tasks, and expectations for behavior at the 18 month visit. Mothers may have turned to using food to reduce their children’s fussiness while keeping them on task. Few studies have examined the development of parent feeding practices and those that do have been conducted with older children (e.g., Webber, Cooke, Hill, & Wardle, 2010). More research is needed in this area particularly across the first two years of life when child eating and diet patterns are being shaped through interactions around feeding.

Concordance between parent report of FTS and observations of parent use of FTS during the laboratory visits was weak with parent report of FTS at 12 and 18 months related to parent use of food to soothe during the 12 month laboratory visit only. Although not surprising, there are several possible explanations for this lack of agreement among the two FTS measures. One, parents may be less willing to report the use of FTS due to their belief that they should soothe their infants using non-nutritive methods. Indeed, the scores for parent-rated FTS were quite low indicating little or no use at each age. However, when challenged with a situation in which their child is distressed, as in the current study, parents may find using food to be necessary either because they interpret their child’s distress to mean that he or she is hungry or because they understand that food is an effective means for quickly calming their child. Two, the lack of agreement may be due to measurement error. Self-reports are known to be influenced by a number of factors reflecting the respondent’s characteristics such as personality, mood, or expectations (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003; Stifter, Willoughby, & Towe-Goodman, 2008). In the present study, for example, mothers’ eating style was related to her report of FTS. Laboratory observations also have their measurement issues. Observations of parent behavior in a laboratory setting or even within the home are limited in scope and can be influenced by the parents’ knowledge that they are being observed. In the present case, the mothers may have used food to soothe because of this special circumstance while others may have not taken the opportunity to soothe their infants with food because of social desirability.

Lack of agreement between parent report and either parent behavior or child behavior has been found in a number of studies including parent feeding behavior (Lewis & Worobey, 2011; Moens, Braet, & Soetens, 2007; Sacco, Bentley, Carby-Sheilds, Borja, & Goldman, 2007). In such cases, researchers suggest that these measures (e.g., observation, parent report) represent “components of variance” (Rothbart & Bates, 2006) with each method contributing to a shared (parents and observers/coders agree) and individual (that which is unique to the method) assessment of the child (Rowe & Kandel, 1997). In the present study, parent self-report and observations provide complementary information about the use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and should be considered together when trying to more fully understand parent feeding practices with very young children. As the working group on food parenting measurement recommended, the addition of observational measures “provide a perspective on food parenting practices that may be important yet not captured through parent report” (Hughes et al., 2013).

Although the parent reports and laboratory observations of FTS were for the most part unrelated, some relationships between the predictors and both measures were indicated. For example, parent report of FTS was positively related to infant feeding style, after controlling for all other variables. Pressuring style, particularly pressure to soothe one’s child with food, was related to FTS at 6 and 18 months. Observations of FTS in the lab were also related to parent report of a pressuring style but only at 6 months. These data provide some modest convergent validity for parent report of FTS, which was also found for the first version of this questionnaire with a cross-sectional sample (Stifter et al., 2011).

Interesting findings emerged regarding 6 month FTS either measured by parent report or observed during the laboratory visit that suggest a qualitatively different period of feeding practice from that found at later ages. Contrary to expectation, mothers who reported using more FTS also reported higher levels of a response/attention feeding style and lower levels of pressuring their child to finish a meal. Finally, mothers who self-reported FTS or were observed to use FTS during the lab visit at 6 months rated themselves as higher on self-efficacy. Responsiveness to the child during feeding interactions suggest a mother who is sensitive to her child’s needs as might be the mother who does not control her child’s eating. On a more general level, parenting self-efficacy reflects the degree to which a parent feels good about her ability to take care of her children, including feeding and calming them. Taken together, these responsive, low controlling, efficacious mothers of young infants who feed them when they cry may interpret this practice as reflecting good parenting because they have likely observed how effectively food calms infants whether or not the child is hungry.

It is important to note that the mothers who reported using FTS at 6 months were also breastfeeding longer than mothers who reported little of no use of FTS. Evidence suggests that mothers of younger children are poorer at reading infant cues of hunger than mothers of older children and report using infant fussing and crying to signal hunger (Hodges, Hughes, Hopkinson, & Fisher, 2008; Hodges et al., 2013; Howard, Lanphear, Lanphear, Eberly, & Lawrence, 2006), particularly if breastfeeding. Thus, a mother who responds to her young child with food when he or she cries may evaluate her parenting as efficacious both because she feels she responds appropriately to what she interprets as her infant’s hunger and is confirmed in this evaluation when her child is soothed. However, our data on infant weight gain suggests that this early responsiveness may have negative consequences.

While the occasional use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress may not have any long-term consequences, our findings suggest that this feeding practice when started early and consistently may contribute to the development of obesity in young children. Infants of mothers who were observed to use food to soothe during the 6, 12 and 18 month laboratory visits were more likely to gain weight faster across the infancy period than infants of mothers who did not use FTS in the lab. Research has shown that rapid weight gain in infancy is a risk factor for childhood obesity (Baird, 2005; Stettler, Zemel, Kumanyika, & Stallings, 2002). As LabFTS was relatively stable from 6 to 12 months and 12 to 18 months, these findings may reflect a pattern of feeding behavior. Over time, parent use of food to soothe infant distress may lead to the infant associating food with states other than hunger. This association may compromise the child’s ability to appropriately interpret hunger and satiety cues leading to increased energy intake and risk for childhood obesity. Or, it may result in the development of an emotional eating style which has been identified as an obesogenic trait linked to parent emotional feeding (e.g., food to soothe), poor diet, and weight gain (Braden et al., 2014; Braet & Van Strien, 1997; Sleddens, Kremers, De Vries, & Thijs, 2010). More research is needed to test the link between parent use of FTS, children’s emotional eating, and childhood obesity.

Parent report of FTS was unrelated to weight gain. This result confirms that when parents are asked about their beliefs and behaviors their responses may not necessarily reflect their actual behavior when their child is distressed. Further, using food to soothe in a setting which puts demands on the parent, as in the case of a crying infant in a laboratory setting, may evoke behaviors that they are less willing or likely to report. The present findings indicate that what a mother does, not what she says, in response to her child’s distress may have important implications for a child’s health.

As noted there are several limitations to both the self-report measures of FTS and the laboratory observation of FTS. We would also add that the LabFTS measure was a dichotomous variable of whether or not the mother responded with food to her child’s distress. A more qualitative analysis of the activities of both the child and mother prior to this decision might shed more light on her intentions. Finally, the availability of the snack tray at the 18 month visit could also have influenced whether the mother used FTS as some toddlers may have persisted in their distress in order to get a snack.

In conclusion, the present study utilized two measures of parent use of food to soothe infant distress, parent self-report and observations of its use in a laboratory setting, examining its development over time. To our knowledge this is the first longitudinal study of this feeding practice. One advantage of conducting a longitudinal study is that we were able to determine that both parent report and observations of food to soothe were relatively stable across the child’s first 18 months of life, a period of rapid development. There was little agreement between the two measures but both were simultaneously related to other factors such as a pressuring feeding style and parenting self-efficacy. Parent use of food to soothe was related to weight gain but only when observed in the lab. This finding suggests the importance of observing parent feeding practices rather than relying exclusively on self- reports. Likewise, the results of the present study indicate that interventions aimed at reducing the risk of childhood obesity should start early within and beyond the parent-child feeding interaction.

Highlights.

Parent report of the use of food to soothe was stable from 6 to 18 months

The number of mothers observed to use food to soothe increased from 6 to 18 months

A pressuring feeding style was related to self-reported and observed food to soothe

Infants of mothers observed to use food to soothe demonstrated faster weight gain

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants to the first author from the National Institutes of Digestive Diseases and Kidney (DK081512) and the John T. Templeton Foundation. Support for the second author was provided in part by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Grant no. 2011-67001-30117 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Childhood Obesity27 Prevention Challenge Area – A2121. The authors want to thank the families who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

From here on in the use of food to soothe, regulate, or calm a young child’s distress will be referred to as food to soothe.

Recall that parent-reported FTS at 6 months was based on two items and not on the same scale as the 12 and 18 month measures. Thus, we were unable to test for continuity from 6 months.

References

- Baird J, Fisher D, Lucas P, Kleijnen J, Roberts H, Law C. Being big or growing fast: Systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. British Medical Journal. 2005;331:929–931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38586.411273.E0. doi: dol: 19.1136/bmj.38586.411273.EO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, O’Connor T, Hughes S, Sleddens E, Beltran A, Frankel L, Baranowski J. Houston…We have a problem! Measurement of parenting. Childhood Obesity. 2013;9:S1–S4. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum A, Burklow K, Deeks C, Powers S, Whitaker R. Maternal feeding practices and childhood obesity. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152:1010–1014. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughcum A, Powers S, Johnson S, Chamberlin D, Deeks C, Jain A, Whitaker R. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in arly childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2001;22:391–408. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L, Davison K, Fisher J. Learning to overeat: maternal use of restrictive practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;78:215–220. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch L, Johnson S, Andresen G, Peters J, Schulte M. The variability of young children’s energy intake. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;324:232–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101243240405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blisset J, Haycraft E, Farrow C. Inducing preschool children’s emotional eating: Relations with parental feeding practices. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;92:359–365. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blissett J, Farrow C. Predictors of maternal control of feeding at 1 and 2 years of age. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:1520–1526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden A, Rhee K, Peterson C, Rydell S, Zucker N, Boutelle K. Associations between child emotional eating and general parenting style, feeding practices and parent psychopathology. Appetite. 2014;80:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, Van Strien T. Assessment of emotional, externally induced and retrained eting behavior in nine to twlve-year-old obese and non-obese children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:863–873. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Lee M. Breastfeeding is associated with a maternal feeding style low in control from birth. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnell S, Wardle J. Associations between multiple measures of parental feeding and children’s adiposity in United Kingdom preschoolers. Obesity. 2007;15:137–144. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S, Kramer M, Narayan K. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison B, Edmunds L, Stratton H, Pruzek R. Rapid infant weight gain predicts childhood overweight. Obesity. 2006;14(3):491–499. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiSantis K, Hodges E, Fisher J. The association of breastfeeding duration with later maternal feeding styles in infancy and toddlerhood: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10 doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans A, Greenberg-Seth J, Smith S, Harris K, Loyo J, Spaulding C, Gottlieb N. Parental feeding practices and concerns related to child underweight, picky eating, and using food to calm differ according to ethnicity/race, acculturation and income. Maternal and Child Health. 2011;15:899–909. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow C, Blisset J. Does maternal control during feeding moderate early infant weight gain? Pediatrics. 2006;118:e293–e298. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish M, Stifter C, Belsky J. Conditions of continuity and discontinuity in infant negative emotionality: Newborn to five months. Child Development. 1991;62:1525–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Birch L. Restricting access to foods and children’s eating. Appetite. 1999;32:405–419. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Birch L, Smiciklas-Wright H, Piccano M. Breast-feeding through the first year predicts maternal control in feeding and subsequent toddler energy intakes. Journal of American Dietetic Association. 2000;100:641–646. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman D, Khan L, Serdula M, Dietz W, Srinivasan S, Berenson G. The relation of childhood BMI to adult adiposity: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2005;115:22–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne J, Van Hulle C, Aksan N, Essex M, Goldsmith H. Deriving childhood temperament measures from emotion-eliciting behavioral episodes: Scale construction and initial validation. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(2):337–353. doi: 10.1037/a0021746. doi: 10.1037/a0021746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Wu W, Chumlea W, Roche A. Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:653–658. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges E, Hughes S, Hopkinson J, Fisher J. Maternal decisions about the initiation and termination of infant feeding. Appetite. 2008;50:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges E, Johnson S, Hughes S, Hopkinson J, Butte N, Fisher J. Development of the Responsiveness to Child Feeding Cues Scale. Appetite. 2013;65:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard C, Lanphear N, Lanphear B, Eberly S, Lawrence R. Parental responses to infant crying and colid: The effect on breastfeeding duration. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2006;3:146–155. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2006.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S, Frankel L, Beltran A, Hodges E, Hoerr S, Lumeng J, Kremers S. Food parenting measurement issues: Working group consensus report. Childhood Obesity. 2013;9:S 95–S 102. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi L, Stifter C, Putnam S. Maternal regulation of infant reactivity from 2 to 6 months. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40(4):477–487. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Emotional distress and control in young children. New Dir Child Dev. 1992;(55):41–56. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219925505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg H, Foverskov E, Væth M. Predictors for early introduction of solid food among Danish mothers and infants: an observational study. BMC Pediatrics. 2014;14:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Worobey J. Mothers and toddlers lunch together: The relation between observed and reported behavior. Appetite. 2011;56:732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens E, Braet C, Soetens E. Observation of family functioning at mealtime: A comparison between families of children with and without overweight. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:52–63. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher-Eizenman D, Holub S. Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionniare: Validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:960–972. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C, Carroll M, Kit B, Flegal K. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index amoung US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P, MacKenzie S, Lee J, Podsakoff N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenburg G, Kremers S, Oenema A, van de Mheen D. Associations of parental feeding styles with child snacking behavior and weight in the context of general parenting. Public Health Nutrition. 2013;17:960–969. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Bates J. Temperament. In: Damon RLW, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Sixth edition. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 99–166. Social, emotional, and personality development. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe D, Kandel D. In the eye of the beholder? Parental ratings of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(4):265–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1025756201689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco L, Bentley M, Carby-Sheilds K, Borja J, Goldman B. Assessment of infant feeding styles among low-income African-American mothers: Comparing reported and observed behaviors. Appetite. 2007;49:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, Fisher J, Birch L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to Adolescence. The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2007;35 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxon J, Carnell S, Van Jaarsveld C, Wardle J. Maternal education is associated with feeding style. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2009;109:894–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry B, McDivitt J, Birch L, Cook F, Sanders S, Prish J. Attitudes, practices, and concerns about child feeding and child weight status among socioeconomically diverse White, Hispanic, and African-American mothers. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleddens E, Kremers S, De Vries N, Thijs C. Relationship between parental feeding styles and eating behaviours of Dutch children aged 6–7. Appetite. 2010;54:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleddens E, Kremers S, Stafleau A, Dagnelie P, De Vries N, Thijs C. Food parenting practices and child dietary behavior. Prospective relations and the moderating role of general parenting. Appetite. 2014;79:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoek H, Engels R, Janssens J, Van Strien T. Parental behavior and adolescents’ emotional eating. Appetite. 2007;49:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler N, Kumanyika S, Katz S, Zemel B, Stallings V. Rapid weight gain during infancy and obesity in young adulthood in a cohort of African Americans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;77:1374–1378. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler N, Zemel B, Kumanyika S, Stallings V. Infant weight gain and childhood overweight status in a multicenter, cohort study. Pediatrics. 2002;109(2):194–199. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter C, Anzman-Frasca S, Birch L, Voegtline K. Parent use of food to soothe infant/toddler distress and child weight status: An exploratory study. Appetite. 2011;57:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter C, Spinrad T, Braungart-Rieker J. Toward a developmental model of child compliance: The role of emotion regulation in infancy. Child Development. 1999;70:21–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stifter C, Willoughby M, Towe-Goodman N. Agree or Agree to Disagree? Assessing the Convergence Between Parents and Observers on Infant Temperament. Infant and Child Development. 2008;17:407–426. doi: 10.1002/icd.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Adair L, Bentley M. Pressuring and restrictive feeding styles influence infant feeding and size among a low-income African-American sample. Obeseity. 2013;21:562–571. doi: 10.1002/oby.20091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Mendez M, Borja J, Adair L, Zimmer C, Bentley M. Development and validation of the Infant Feeding Style Questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S, Nowson C. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23:887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traveras E, Scanlon K, Birch L, Rifas-Shiman S, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman M. Association with breastfeeding with maternal control of infant feeding oat age 1 year. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e577–e583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Fritjers J, Bergers G, Defares P. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986;5:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Birch L. Does parenting affect children’s eating and weight status? International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2008;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Sanderson S, Gutherie c, Rapoport L, Plomin R. Parental feeding style and the inter-generational transmission of obesity risk. Obesity Research. 2002;10:453–462. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L, Cooke L, Hill C, Wardle J. Child adiposity and maternal feeding practices: a longitudinal analysis. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2010;92(6):1423–1428. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.30112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]