Abstract

Widowhood is a common life event for married older women. Prior research has found disruptions in eating behaviors to be common among widows. Little is known about the process underlying these disruptions. The aim of this study was to generate a theoretical understanding of the changing food behaviors of older women during the transition of widowhood. Qualitative methods based on constructivist grounded theory guided by a critical realist worldview were used. Individual active interviews were conducted with 15 community-living women, aged 71 to 86 years, living alone, and widowed six months to 15 years at the time of the interview. Participants described a variety of educational backgrounds and levels of health, were mainly white and of Canadian or European descent, and reported sufficient income to meet their needs. The loss of regular shared meals initiated a two-stage process whereby women first fall into new patterns and then re-establish the personal food system, thus enabling women to redirect their food system from one that satisfied the couple to one that satisfied their personal food needs. Influences on the trajectory of the change process included the couple’s food system, experience with nutritional care, food-related values, and food-related resources. Implications for research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: food intake, widowhood, eating behavior, older adults, qualitative

Late-life nutritional inadequacies can contribute to the progression of loss of function and disease (Bates et al., 2002) and consequently, a reduction in quality of life (WHOQOL Group, 1995). Widowhood is a common event for married older women (Carr & Bodnar-Deren, 2009) and has been related to poorer diet quality (Heuberger & Wong, 2014; Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993), making it an important life-stage transition to more fully understand with respect to how food behaviors develop and change. A small body of literature presents convincing evidence that widowhood is related to altered diets and eating behaviors. Widowhood, has been associated with poorer energy intakes, nutritional status, and diet variety (Conklin et al., 2014; Han, Li, & Zheng, 2009; Heuberger & Wong, 2014). Furthermore, longitudinal research has shown that loss of a spouse is related to a decline in diet variety, decrease in vegetable and red meat intake, and weight loss (Kwon, Suzuki, Kumagai, Shinkai, & Yukawa, 2006; Lee et al., 2005; Shahar, Schultz, Shahar, & Wing, 2001). Recently widowed older adults (widowed ≤4 yrs) compared to married peers were found more likely report poorer appetite, meal skipping, poorer diet quality and variety, and lower fruit and vegetable intake (Johnson, 2002; Rosenbloom & Whittington, 1993; 1997; Wells & Kendig, 1997; Wilcox et al., 2003).

Qualitative data has helped to describe why eating behavior changes in widowhood. Johnson (2002) conducted focus groups with recently widowed (< 2yrs) older adults (N=22, 77% female) and reported that the widowed participants described loss of appetite due to emotional changes with bereavement and difficulty with mealtimes due to associated memories of the shared activity with their spouses. Participants also described reduced motivation to cook for themselves and consequently were either skipping meals or making less healthful choices. Rosenbloom and Whittington (1993) learned in one-on-one interviews that the majority of widowed women had previously enjoyed eating and mealtimes but that eating became a chore after the loss of their spouse and made worse by loneliness experienced at mealtimes. Quandt, McDonald, Arcury, Bell, and Vitolins (2000) followed 12 recently widowed older women (widowed <3 yrs) over a period of three years. They reported that widowhood generally resulted in a ‘lifting’ of food-related obligations as a wife. Widowed women reacted to this change in two ways. Some appreciated an opportunity to eat according to their personal preferences. However, others experienced a complete disorientation by the loss of these obligations, which was characterized by loneliness, apathy towards food and lack of appetite.

Widowhood is the life stage that begins with the death of a spouse (Carr & Bodnar-Deren, 2009; Lopata, 1996) and bereavement is the psychological process of coping with this loss (Atchley, 1988). Although many studies consider widowhood as a static state, widows “do not stand still in their mourning” (Silverman, 2004, p.91) but move between restoration- and loss- oriented behavior (Stroebe & Schut, 1999). Quandt and colleagues (2000) compared their recently widowed sample (n=12) to a larger sample of longer term widows and found that the eating situations of those widowed longer had stabilized; most had overcome the grief that had affected their appetite or increased meal skipping. Wilcox and colleagues (2003) also found fewer increases in nutritional and other health vulnerabilities among longer term widows (widowed > 1 yr) compared to those widowed within 1 year. These results mirror the understanding of physical and psychological health during transition to widowhood whereby the negative effects of bereavement are normal and most recover with time (Stroebe et al., 2007). Yet, the process of how this transition occurs has yet to be elucidated.

Understanding food behaviors is complex as such behaviors are the product of multiple individual, social, and environmental processes that are not necessarily consistent or connected (Sobal, Kettel Khan, & Bisogni, 1998). Food behaviors consist of all behaviors related to the acquisition, preparation, serving, consuming, and disposing of food (Sobal & Bisogni, 2009). Furst, Connors, Bisogni, Sobal and Winter Falk (1996) proposed that the re-occurrence of making food behavior decisions over the life course leads to the development of personal systems for food choice. The system includes value negotiation that involves the weighing of different considerations in making food choices (e.g. managing relationships, ideals of health, nutrition, taste, monetary considerations, convenience) and the strategies or scripts that evolve through habitual choice patterns. One’s food ideals, personal food-related needs, preferences, identity, and resources influence the personal system. Personal systems are embedded within the social and food context to which they relate, the most proximal being their household’s food system (Sobal, Bove, & Rauschenbach, 2002; Furst et al., 1996; Schubert, 2008). When there is more than one member in the household, there are established processes and roles regarding acquisition, preparation and consumption of food (De Vault, 1991). The sometimes competing priorities of other members affect the household food system and consequently also affect the personal system (Furst et al., 1996). Consequently, meals shared between the couple are the result of a complex negotiation about food choice (what and how much), choice of preparation, and timing of mealtimes. These negotiations usually do not occur for each meal, but couples make them over the duration of their relationship. When caregiving is involved, caregivers may feel significant distress related to meal preparation (Locher et al., 2010). Widowhood represents a shift in the social and food context in which the personal system is embedded. Shifting in these contexts can be a source of change in personal food behaviors (Quandt, Arcury, & Bell, 1998). Elaboration of how this change occurs is needed to better support older women in this nutritionally vulnerable period. The aim of this study was to generate a theoretical understanding on the process of how food behavior changes among older community-living widowed women who were living alone.

Methods

Critical Realism (Bhaskar, 1975; Sayer, 2000) and Grounded Theory Methodology (Charmaz, 2006) guided the data collection and analysis approach. The research was theory oriented with the aim of developing an explanatory model of food behavior among older widowed women. Critical realism views behaviors as the outcome of the interplay of individual and structural factors. In-depth interviews were used to explore the experiences and understandings of the participants. However, under critical realism, individuals are not necessarily aware of the structural influences on their behavior (Bhaskar, 1975), and thus we also sought to engage in a process of theorizing to propose explanations for changing food behaviors in widowhood (Sayer, 2000).

Sample

Participants were recruited through advertisement, word of mouth and in-person at senior recreation centres and one senior apartment complex in a large Canadian city. Women aged 65 years of age or older, widowed within five years, community-living, living alone, cognitively well, and English-speaking were invited to participate. Three participants widowed longer were included in the study because of their eagerness to share their experiences and their assessment that they could recall and reflect on their early widowed experience (Kvale, 1996). The final sample included fifteen participants widowed six months to fifteen years. Nine participants self-selected, six were snowballed into the study through in-person recruitment sessions. All but two participants were white and of Canadian or European descent; half of the participants came to Canada as adults. Participants were aged 71 to 86 years (M = 77, SD = 5.3) (Table 1) and all but two participants had children, most living in the same city. All but two also reported that they had sufficient income to meet their needs. The women had a range of educational backgrounds (Table 1) and all had participated in the workforce at some point in their lives. Some left the workforce for family obligations (n=3) and one remained active in non-paid work outside the home at the time of the interview.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Participants (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 70–74 | 7 |

| 75–79 | 4 | |

| 80–84 | 2 | |

| 85–89 | 2 | |

| Years widowed | ≤1 yr | 5 |

| >1 yr - ≤ 3yrs | 3 | |

| > 3 yrs - ≤ 5yrs | 4 | |

| > 5 yrs | 3 | |

| Years married | 20–30 yrs | 5 |

| 31–40 yrs | 2 | |

| >40 yrs | 8 | |

| Responsibility in couple food behaviors | Primary | 11 |

| Shared | 1 | |

| Not responsible | 2 | |

| Reported health | Excellent | 4 |

| Very good | 4 | |

| Good | 2 | |

| Fair | 4 | |

| Poor | 1 | |

| Education | Post-secondary* | 5 |

| High school * | 6 | |

| Grade school* | 4 |

some or completed

Data collection and analysis

Interested participants contacted the first author (EV) by phone. Screening questions were asked to ensure eligibility and to facilitate sample diversity. Variation was initially sought in years of widowhood. Other demographic variables such as self-reported health, years of marriage, ethnicity, and financial adequacy were included to describe the sample. In-person interviews were conducted at a time and place of the participants’ choice. Prior to the interview, participants were provided with a consent letter detailing the study. EV verbally reviewed the document and provided an opportunity for questions. Informed signed consent was then obtained; participants were reminded that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Interviews were active (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995), conversational in style, and followed a loose and flexible structure. Participants were ‘partners’ in the research process (Charmaz, 2006); viewed as experts of their own experience, participants were encouraged to participate in the creation of knowledge by being made aware of the research agenda. Interview questions focused on how and why the women’s experiences with eating, shopping and meal preparation had changed in widowhood.

Data collection and analysis were concurrent, such that interviews were transcribed and analysis initiated before the next interview was conducted. Constant comparative analysis was used whereby each interview, code, concept and category was examined relative to the others and assessed for similarities and differences (Charmaz, 2006). As the study progressed and EV’s understanding evolved, the interviews became more structured to facilitate theoretical sampling; interview questions were developed to explore emergent concepts and categories (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Interviews were conducted by EV, ranged from 1–2 hours in length, and were digitally recorded. Notes regarding non-verbal data were included in the transcript based on the interviewer’s recall.

Data were organized using qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti, version 7). Analysis was abductive (Charmaz, 2006; Daly, 2007). Line-by-line coding enabled interpretive naming of each segment of data. Focused coding was used in which only the most meaningful and explanatory labels from initial coding are selected. Axial coding was then used which is the process of organizing the focused codes into categories to reflect how the codes were related to one another. Finally, theoretical coding was conducted whereby the most significant categories are selected for synthesis into a unifying understanding of the concept under study (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2008). Throughout analysis, EV used her knowledge of the empirical and theoretical literature on widowhood, food behaviors in widowhood, social influences of foodways among older adults, and commensality to sensitize her to these concepts during interviews and analysis. EV met regularly with all authors to review the audit trail of data collection and analysis to enhance credibility, transferability, and confirmability (Patton, 2002). This study was approved by the Ethics committee of the University of Guelph (certificate # 11MY004).

Results

Overview of the Theoretical Model

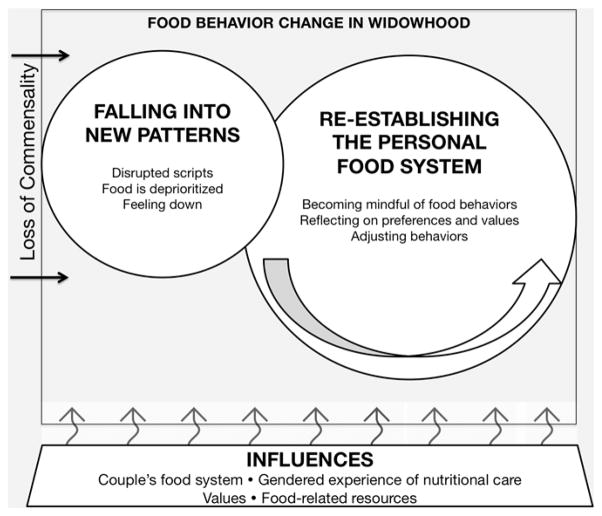

The figure proposes a theoretical model of shifting food behavior described by older widowed women in this study. All the women interviewed in this study described shifts in food behavior related to their experience of widowhood. We interpreted the shifts in food behaviors in widowhood as a two-stage change process through which widows redirect their household food system from one that satisfied the couple to one that satisfied their personal food needs. Changes began with the loss of commensality, when couples were no longer sharing meals. In the first stage Falling Into New Patterns, disrupted scripts, deprioritized food, and feeling down, led to new food behaviors. This stage was viewed as temporary and behaviors often did not align with participants’ espoused food values. In the second stage Re-establishing The Personal Food System, this misalignment was recognized as participants became mindful of their behaviors, reflected on their food-related preferences and values, and adjusted their food behaviors as necessary, leading to a more satisfactory personal food system. Although these stages are described as chronologically distinct and sequential, some women experienced them as overlapping and/or iterative. A number of influences enabled or constrained different aspects of the change process and determined their unique trajectory including the couple’s food system, gendered experience of nutritional care, values, and food-related resources. The following section details the main categories of the model with examples from the data.

Figure.

Theoretical model of food behavior change in widowhood

Loss of Commensality

Participants described the earliest changes related to widowhood as beginning with the loss of commensality, that is when the couple no longer shared meals. For most, this occurred prior to widowhood during their spouse’s illness when participation in shared meals and other food behaviors declined. One widow explained how her food behaviors started to shift with her husband’s appetite changes:

I was eating a lot lighter foods because he didn’t have the appetite for the heavier foods, like the potatoes and stuff. He just wanted soup and a salad or maybe a sandwich. I wasn’t going to cook a meal for myself when he couldn’t eat you know.” (78 yrs, widowed 4 yrs)

For some, loss of commensality occurred suddenly if the spouse moved from the home into a facility, or upon his death. As participants stopped sharing meals with their spouses, they began to fall into new patterns of food behavior. How participants experienced loss of commensality and specific changes to food behavior that ensued is discussed in another publication (Vesnaver, Keller, Sutherland, Maitland, & Locher, 2015). Here we limit our discussion of loss of commensality as a catalyst for the change process.

Falling into new patterns

Disrupted scripts

Food behavior scripts are the procedural knowledge that informs the sequence of behaviors for particular situations (Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Jastran, & Devine, 2008). For example, the script that leads to breakfast consumption at home may include actions such as rising at a particular hour, turning on the radio or television, putting on the coffee, and getting cereal from the pantry. These actions would be executed in the same manner each time the situation is encountered. Scripts dependent on the spouse such as those related to shared meals and planning and preparing food in consideration of the spouse were disrupted once meals were no longer shared. For example, this woman was having difficulties with planning and shopping after her husband passed:

My habit was: shop with sales flyers on the weekend, buy the best buys, plan my meals around that. So, shopping was different. Buying more, having more stuff in the house on hand. Working with that. [Interviewer (I): how come that doesn’t work for you anymore?] Well, having to make a meal for one is much different - look most recipes make for four. So I find when I do that, I’m making up a batch of something and I’m eating it you know like most of the week. It gets boring. (71 yrs, widowed < 1 yr)

The script of the timing of eating occasions was sometimes disrupted, such as preparing breakfast at a specific time based on the spouse’s normal rising time (77 yrs, widowed 1 yr). She explained that in widowhood she had no reason to get up in the morning, resulting in erratic rising and eating times: “well I eat when I’m hungry that’s it. I mean that could be any time, that could be around 11 o’clock when I really get hungry or it could be three o’clock” (77 yrs, widowed 1 yr). She felt no need to maintain the schedule and structure from her couple’s food system. Others had scripts disrupted that in part determined food choice for the day such as important elements of the shared meal: “He always preferred to have a piece of meat at supper” (73 yrs, widowed 15 yrs). For those largely not responsible for food behaviors in their couple, their scripts such as “coming to the table” (81 yrs, widowed 2 yrs) no longer resulted in consumption of a meal. When scripts were disrupted, it seemed that women were spontaneously negotiating their dominant values and resources to guide their food behaviors, often resulting in new behaviors for that particular situation.

Food is deprioritized

For some, the challenges of disrupted scripts were compounded by deprioritizing personal nutrition for the period of time when they were caring for ill spouses and/or shortly after the death of their spouses. Among caregivers, the focus was on feeding their ill husbands and shuttling to and from various health care providers; they ate in-between, whatever there was, and often purchased convenience or fast foods. One participant shared: “when my husband was dying, I was at the hospital three times a day, sometimes four, for over a month at one period of time. Everything I ate I purchased cooked ” (70 yrs, widowed 5 yrs). Another woman who lost a lot of weight during her husband’s illness explained: “he was in and out of the hospital a lot and you know, I’d skip lunch and when I came home I’d be too tired to cook so I’d have a sandwich or something” (78 yrs, widowed 4 yrs). Discussions about participants’ food behaviors at home during their husband’s illness centered on their husband’s appetites and intake:

His appetite was reduced, he wasn’t eating as well and then it got to a point when he would say ‘I can’t eat that’ and I said ‘well what’s the matter with it? You don’t like it? Would you like me to prepare something else.’ ‘No, it’s not, I like it but I can’t eat it.’ So that was discouraging. Think, preparing what I thought would be a meal that he’d enjoy and having him look at me and say ‘I can’t eat that.’ (71 yrs, widowed < 1 yr)

Upon their spouse’s passing, there were an overwhelming number of tasks to be attended to including in some cases, new responsibilities with steep learning curves. Food was not a priority evidenced by participants re-directing the conversation away from food when discussing the challenges surrounding the illness and death of their spouses:

When he first died it was dramatic, he died of cancer, and it was dramatic. And I, well I didn’t stop eating, but I had an awful lot of [difficulties]. We had our own business, a tool and die making business. And you know he got sick and I still had to try to run it, but I mean, I’m not a tool and die maker so, you know what I mean? I was having to bring stuff home like quotes and stuff... I was just running ragged here you know? (78 yrs, widowed 7 yrs)

In this period of transition, convenience and ease of food preparation were prioritized. When scripts were disrupted and food was deprioritized, food behaviors were more impulsive and less conscious. Participants simply did not have the time or energy to allocate any more attention to food.

Feeling down

Finally, some participants described new patterns of food behaviors due to depression or a depressed mood. In widowhood, participants described that they spent more time alone and in the house, they felt lonely and sometimes overwhelmed, and they grieved their spouse and the couple world many felt expelled from. Depression was said to affect appetite and interest in preparing meals. As this participant explained:

Well you know if you’re feeling depressed and lonely and fed up you can’t be bothered to cook. [I: were you hungry at all when you were not cooking?] Not specially. I really can’t remember, I mean but [the cooking] was very minimal. I would just have soup or something you know? You know when you’re truly depressed you have no appetite. (78 yrs, widowed 7 yrs)

Another participant similarly described her appetite in the first year after her husband’s death: “Oh I was not hungry and I was very depressed” (85 yrs, widowed 3 yrs). Some participants started to constantly snack between meals and attributed this behavior to their mood. For example:

When I’m depressed I pick. If there’s candy in the house, I’m into the candies, if there’s cookies I’ll eat cookies or if there’s ice cream I’ll have ice cream. I pick a lot when I’m depressed. So when I pick a lot, I don’t eat meals because I’m not hungry, I’ve already eaten. (78 yrs, widowed 4 yrs)

Thus, for some eating was used as a coping mechanism to deal with negative emotions. It was also used as an activity to fill long afternoons and evenings spent alone. Snacking as coping was interpreted as distinct from the snacking that was part of general grazing patterns that some participants had developed. The former was related to mood, and participants often struggled with this behavior. The latter generally replaced a three meals per day structure rather than interfere with it.

As the new food-related behaviors from disrupted scripts, de-prioritized food, and feeling down were repeated, new patterns began to fall into place. These new patterns were considered temporary during this period of transition. Women suspended evaluation of these behaviors and felt free to step outside of the dominant food-values they held. Consequently, new patterns were often not congruent with the women’s expressed food values and ideals.

Re-establishing the Personal Food System

Becoming mindful of food behaviors

Widows discussed becoming aware of their food behaviors and evaluating the new patterns they had fallen into after the loss of commensality. Usually triggered by a realization that their new patterns deviated from their couple’s previous patterns, their espoused values, or perceived social norms, widows evaluated how their food behaviors aligned with their food-related preferences and dominant values in their new social context. Some participants were alerted by solicited or unsolicited feedback from their social contacts. A widow who had fallen into the pattern of replacing her noon and evening meals with continuous grazing shared how she became aware that others did not share her pattern: “Well people would say ‘what did you have for supper?’ ‘Um well, mmm’. And very embarrassed and I thought they’re going to think that I – well I don’t know what I thought” (73 yrs, widowed 8 yrs). Becoming aware that her new patterns deviated from social norms triggered self-evaluation. Physical feedback such as body weight, change in sleep patterns or general feelings of wellness also triggered evaluation of their food behaviors. This participant noticed a decrease in sleep quality when she stopped eating a substantial evening meal in widowhood: “I was waking up at night and being restless and [could not] get back to sleep and I thought, is it because I’m hungry?” (78 yrs, widowed < 1 yr).

Some participants described a conscious decision to re-establish their personal food system. One woman remembered her decision to take responsibility for her physical, emotional, and financial health, “you have to get yourself together” (78 yrs, widowed 7 yrs), she explained. Being overwhelmed by widowhood could only go on for a finite period in her view. When food behaviors were judged to be misaligned with their food-related values, widows expressed dissatisfaction with their food behaviors and related in interviews what they ‘should’ be doing, often prompting them to work to re-establish a personal food system and thus realign their food behaviors.

Reflecting on preferences and values

In the process of re-establishing a personal food system without needing to consider others, participants had the opportunity to reflect upon their food-related preferences and values. Did they like to eat three square meals a day? When did they like them? In the first stage of change, when they were falling into new patterns, some had tried new food behaviors and discovered that they liked these new ways, while others ultimately found confirmation that these behaviors were not appropriate for their more permanent personal food system. They reflected on all aspects of food behavior, including purchasing, choice, preparation, and how, where, when and with whom food was consumed. For example, one woman learned that she loved to eat a “comfort meal” late at night in bed. This is what she called a “support meal” (to her main midday meal), replacing her previous pattern of an earlier evening meal. She never discovered this way of eating in marriage “well because you had family meals” (71 yrs, widowed 5 yrs).

Women also reflected on their values asking the question, what is important to me about food in this new context? For example, one woman never “loved” cooking, but valued providing her husband with a cooked evening meal: “I used to leave the business early and go home and cook meals so that by the time he came home there was a proper meal” (78 yrs, widowed 7 yrs). In widowhood, she valued the convenience of commercially prepared foods instead: “when you’re all by yourself you can just pick whatever you want. So I always go [to the store] and pick a nice salad, ‘oh yes that will do’. You know, I look forward to that” (78 yrs, widowed 7 yrs). Women shifted their value prioritization when previously dominant values no longer made sense in their new context.

Adjusting behaviors

In order to re-establish the personal food system, participants adjusted their food behaviors to align with their present preferences and values. Participants tried different strategies of meal preparation, shopping, or meal patterning. As an example, a participant explained that after having fallen into new patterns of eating “these huge cheese sandwiches” that she did not perceive as being healthy, she was “trying to become a bit more disciplined about [cooking]… like I’d be cooking up tonight, a bean and vegetable mix sort of a curry, and then brown rice and that will last me for about four days” (73 yrs, widowed 4 yrs). When successful, these strategies become part of the re-established personal food system.

Participants’ social networks sometimes encouraged experimentation with new behaviors. For example, one widow had been struggling with eating foods that had been kept too long in her refrigerator. She recognized this behavior as unhealthy but was unable to keep track of how long foods had been kept. Her daughter encouraged her to try catered single-serve frozen meals as a potential solution. She loved them:

They’re good. Honey, they give you a menu, you pick whatever you want. So my daughter and I, we take a menu and mark soup and everything, dessert and they’re just good! I don’t think I want to cook again. It’s good and it’s for six dollars a day! (85 yrs, widowed 3 yrs)

In her view these meals were ‘home cooked’ thus enabling her to align with this value as well as health by eliminating her challenges with food management. Another widow relied on her social network to be able to align her eating with her value of commensality, she arranged “[to] meet friends for one proper meal a day” (78 yrs, widowed < 1 yr). She also had developed a strategy to align this value even when her network was unavailable. She describing going to a local grocery store to find company: “in their little dining area, there’s always someone I can look at and they will smile, and a conversation starts, and I end up moving to their table, they say ‘well don’t eat alone, come here!’”(78 yrs, widowed < 1 yr).

As women became satisfied with how their food behaviors aligned with their preferences and values, they became satisfied with their personal food system and spoke about their choices with confidence “oh I don’t worry about [my eating habits] because I eat a balance. I look for the kind of food that I’m eating and it has nutritious value, right? So it keeps me healthy” (71 yrs, widowed 5 yrs). This satisfaction also meant more stability in their eating behaviors.

Women described not always being able to achieve perfect alignment of their preferences and values due to constraints in resources, health, and social context. A participant had described herself as an excellent cook who enjoyed receiving her friends: “my friends were always delighted to be invited to my house for dinner, and always praised the meals that I served them and that felt good” (71 yrs, widowed < 1 yr). However, in widowhood, not only did she lose her spouse, but her other social relationships changed. She explained, “I don’t know what’s happened to the friendships we had, a lot of the friends were friends of my husband’s, and we’re not socializing anymore together.” Despite wanting to continue the behavior of entertaining, she lacked the social network to do so. Some accepted an imperfect alignment as part of aging. A participant explained how her new strategy of daily frozen meals was appropriate for her because she was older: “you are young, you gotta keep doing…I give up and I like it!” (85 yrs, widowed 3 yrs).

Influences

The unique trajectory of the change process for participants was determined by a set of influences that enabled or constrained different aspects of the process. The main categories of influences on the aligning process were the couple’s food system, gendered experience of nutritional care, values, and food-related resources.

The couple’s food system

The couple’s food system involved a set of established food behaviors that had been negotiated over the lifetime of the couple. There were defined agreements and roles regarding acquisition, preparation and consumption of food. Mealtimes were the result of complex negotiation about food choice, choice of preparation, timing of mealtimes and other ritual activities connected to the meals (such as prayer, talking about the day’s activities, watching television). The food behaviors that made up the couple’s food system were described as habits that were carried into the change process as the widow’s starting point. How each member of the couple was involved in the couple’s food system impacted how the surviving member needed to readjust to the absence. For example, readjustment from a system where the husband was responsible for the shopping (and was the sole licensed driver) would be quite different than if the wife had done all the shopping. There would also be significant readjustment within planning if meals were arranged primarily around the husband’s unique preferences than if they had shared preferences, or if planning was centered on the wife’s preferences.

Gendered experience of nutritional care

For women, feeding is a highly complex construct that is interwoven with caring for one’s family and the gendered expectations of feeding responsibilities (DeVault, 1991). Whether or not women cooked in their marriage or their feelings about the activity, all drew from this gendered discourse when relating their responsibilities to feed their families, ultimately complicating their relationship with food beyond simply self-nourishment. How women engaged with this gendered activity throughout their life course impacted how they re-established a personal food system. For example, some women who were very focused on the nutritional care of their families to the exclusion of their own needs, had difficulty acknowledging and accepting their needs and preferences as valid goals for their new personal food system. Others were relieved to be free of the burden of responsibility to others that they eagerly focused on their own needs. Furthermore, women judged their level of engagement in food-related activities in widowhood in light of this discourse; for example labeling themselves as poor participants if they were ‘never much of a cook’ or saying they should be cooking more in widowhood (even if they never liked it or never did it in marriage). For this age cohort, women’s relationship with the gendered expectations of feeding responsibilities followed them into widowhood despite no longer having anyone to feed.

Values

Participants described diverse values that influenced their decisions including taste, pleasure, convenience, health, food quality, survival, economy, management of relationships, commensality, and food preparation. The set of values held by an individual laid out a certain range of behaviors from which she chose, particularly when her scripts were disrupted. For example, if health had been a primary driver of food decisions in the past, a woman was less likely to regularly turn to options she viewed as less healthful. It also informed how she re-established her personal food system. Women adjusted their personal food system to reflect their own individual values, resulting in very different sets of food behaviors.

The importance of food for the individual in general influenced how long she remained in the first and temporary stage (falling into new patterns). Women who ascribed high importance to the smooth functioning of their personal food system did not tolerate temporary patterns for long and quickly worked to re-establish their personal food system. Those for whom food was less important in their larger set of values required temporary patterns for longer as they prioritized other aspects of their life.

Resources

A woman’s financial, physical, and social resources affected the options for food behaviors she had available to her. For example, many women relied on commercially prepared foods, eating in restaurants daily, and a variety of paid support services, options only available to those with sufficient financial resources. Similarly, cooking required sufficient physical health to shop and engage in preparation activities. Finally, when these resources were lacking, a social network they could rely on to help them in their food behaviors also affected their alignment process (such has help with shopping and transportation). Social resources were not only used to make up for physical and financial challenges, but also to facilitate certain preferences such as sharing meals. For example, participants that relied on friends for commensal meals had sufficient social resources to do this. How participants utilized these resources also impacted their trajectory. For example, one woman relied on her daughter to do her grocery shopping, but she did not feel comfortable asking anything more saying that “my people can’t be with me all the time because they’re working. They got more to do than to picnic you know?” (86 yrs, widowed 1 yr). Finally, an individual’s social network provided reminders of ‘normal’ eating patterns or of their prior eating patterns. Some participants described feeling freer to deviate when their contacts were not present. In some cases intentional oversight by family was viewed as helpful, keeping them from “going off the deep end” (74 yrs, widowed 4 yrs) with respect to food. Despite being helpful, this form of contact was often also viewed as intrusive. When participants were connected with other widowed women, they learned of social norms regarding this group, sometimes facilitating behaviors that would have seemed unacceptable before based on their prior social experiences.

Discussion

Widowhood is Transformative for Older Women’s Eating Behaviors

A key question in the widowhood and diet literature has been whether the changes and types of eating behaviors identified in descriptive studies are temporary disruptions from which widowed women recover, similar to their recovery from other psychological and physical disruptions (Wilcox et al., 2003). This study addresses this question by exploring the process of change and identifying two stages of food behavior change experienced in widowhood. The first stage is a temporary shift, attributed to a combination of stressors surrounding widowhood and the change in the social context of the food system. The second is an adaptive shift whereby women make mindful decisions and behavior changes to create a personal food system that they are satisfied with. The temporary shift may be conceptualized as linked to the loss of commensality and the stress of the events surrounding the loss of a spouse, including but not limited to, the grieving process. The adaptive shift however is related to the fact that in widowhood, the widowed woman creates a food system to feed one person – herself. The re-establishment of the personal food system characterized by conscious re-definition of one’s food-related preferences and values suggests a transformation rather than a recovery from stress (Martin Matthews, 1999). The transformation included the trial of new behaviors and for some the solicitation of others for feedback regarding their food behaviors. Further research should examine whether the re-establishment process may also include receptivity to outside intervention.

Our findings of stabilized food behaviors of the re-established personal food system echo the findings of Quandt et al (2000) that found more stable eating behaviors among longer-term widows. However, stability does not indicate the healthfulness of the diet. Widowhood, irrespective of time since the death of their spouse, has been associated with poorer vegetable and energy intake (Heuberger & Wong, 2014; Wilcox et al., 2003) and poorer nutritional status (Han, Li, & Zheng, 2009). Research examining the quality of diet in widowhood once a widow describes that she is satisfied and stable in her eating habits would help to elucidate the longer-term effect of widowhood on diet quality.

Social Regulation in Widowhood

One mechanism of marriage hypothesized to improve health outcomes is increased social regulation (Berkman, Glass, Brisette, & Seeman, 2000). Regular social contact with a spouse may provide encouragement to adhere to social dietary norms and the couple’s dietary norms (Vesnaver & Keller, 2011). Frequent social contact from the larger social network may also regulate general eating patterns. Our findings that social contact during the first stage of change may have limited deviations from prior patterns or what was perceived to be ‘normal’ patterns of food behaviors, lend support to the social regulatory influence on food behavior. Similarly, Conklin and colleagues (2014) found a greater negative association of widowhood and vegetable variety among older women with infrequent friend contact compared to those with frequent friend contact. It should be noted that the regulation effect depends on the norms espoused by the social group (Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010). Women in this study who were connected with other widowed women learned of behaviors considered ‘normal’ for this group. Due to the common nature of this experience among older women, the perceived norms of this group may represent an important influence on food behavior.

Re-defining Food-Related Preferences and Values in Widowhood

Participants reflected on and adjusted their food-related preferences and values. Prior research has found that widowed women shift their food choices to follow their own preferences (Johnson, 2002; Quandt et al., 2000), suggesting that in cases where couple’s differed on food preferences, women deferred to their husband during marriage. Our results extend this understanding; women’s preferences are dynamic and food choice in widowhood shifts towards both long-held preferences and new ones developed in widowhood. Preferences included not only food choice, but also other food-related activities such as acquisition and preparation.

Widows have described a conscious reflection on their identity as a central part of widowhood (Chambers, 2005; Cheek, 2010; Lopata, 1973; Martin Matthews, 1991; Silverman 2004) and re-defining the self has been described as a key step in successfully moving through bereavement (Silverman, 2004). Our results show widowed women engaging in a similar process with respect to their food behavior; they engaged in a conscious reflection of their food-related preferences and values, independent from when they shared a household food system and food behaviors with a spouse. This reflection enables the establishment of a new personal food system that is aligned with the widow’s present food-related needs.

Mechanisms Beyond Grief in Initial Shift

Grief is thought to play a role in the changes in food behaviors seen in widowhood (Rosenbloom & Wittington, 1993). Although grief likely contributed to the initial changes in food behavior due to feeling down, it was not the only reason food behaviors shifted for women in this study. The presented model expands our understanding to include other sources of stress to the personal food system including those related to food-provision during caregiving, limited time during caregiving for food-related activities, and non-food related tasks to attend to shortly after the death of the spouse. Stressors indirectly related to bereavement have also been found to have important consequences on effective coping in widowhood (Stroebe & Schut, 2010). Although recruitment methods did not specifically target women exhibiting different types of grief or levels of coping, there was variation in coping including two participants who exhibited symptoms characteristic of chronic grief (Ott, Lueger, Kelber, & Prigerson, 2007).

Our analysis also highlighted the loss of commensality as a key catalyst of change, which usually occurred prior to the spouse’s death. Loss of commensality and changes related to caregiving all resulted in changes to food behavior which in many cases started well before the event of widowhood. Quandt et al. (2000) also found the transition of widowhood began prior to the spouse’s death with their terminal illness. The initial changes were usually viewed as temporary for the period of transition and thus occurred with little attention or concern. If diet quality suffers, even short-term nutritional inadequacies can have negative health-related consequences in older adulthood (Raynaud-Simon, 2009).

Study Strengths and Limitations

This qualitative study enabled the development of new theoretical explanations for food behaviors shift in widowhood. The findings suggest a framework of propositions for further research as well as practice. Like all interpretive research, another researcher may come to different conclusions with the same data. The number and selection of participants, while appropriate for this study, do not support generalization, although variation did exist within this sample, including low income, women who did not lead the food related activities in their spousal relationship, and a range of educational backgrounds. The in-depth retrospective interviews enabled the collection of the reflective data needed to efficiently understand a process (Morse, 2001). Yet, prospective observation may have yielded a different understanding and future work should consider a longitudinal data collection process. We sought variation in time since widowhood, future work should prospectively study participants from the loss of commensality identified in our study as the start of the change process. We speculate that there may be different patterns of movement between the stages through extended caregiving. Participants were recruited from senior apartment complexes and recreation centers and thus were a group with knowledge of, interest in, and ability to access community resources and services. Participants also reported regular contact with friends and family; however the size and nature of their social networks were not measured. Future research should also explore how the shifts in food behaviors may be experienced differently among those more socially isolated. Participants for the most part described seemingly fulsome diets and struggled with eating too much rather than not enough. Participants ‘knew’ of other widowed women that ate little after their spouses passed away, but we were unsuccessful recruiting them. The voices of women that drastically reduce their intake in widowhood need to be included in future work on food behaviors and widowhood. There are likely concepts or processes outside of the current model such as chronic grief (Hansson & Stroebe, 2007) or appetite for life (Wong, 2005) that would be involved. The women represented here were predominantly white and lived alone; other cultural or ethnic groups may experience food and widowhood differently, especially those that may live in multigenerational households. This research focused on the experience of women. As widowers may have unique challenges in widowhood due to the cultural expectations regarding men and women’s roles in this current age cohort, future work should also explore how men adapt to their changed food behaviors.

Implications for Research and Practice

The loss of commensality typically experienced in widowhood transforms older women’s dietary behaviors. Lack of appetite is well documented as a symptom of grief (Shear et al., 2011). Other types of dietary changes should be anticipated with the loss of commensality, often occurring prior to the death of the spouse. The period during a spouse’s illness is usually characterized by high levels of contact with health professionals. There is an opportunity to intervene in advance with information and resources. Resources to guide food choices that are healthful but that prioritize convenience may help shape the new patterns women fall into and support women during the initial transition. Women who hold dominant values of health may be receptive to nutrition education efforts when they are re-establishing their personal food system. Expression of incongruence between behaviors and dominant values may indicate evaluation of behaviors, and thus opportunity for intervention. Diet in widowhood is not static and therefore widowhood examined as a static factor in quantitative analyses to describe eating behaviors may mask the underlying process. Further research is needed to identify measureable markers of the change process to assist with the creation of meaningful widowhood variables to be used in food and nutrition research. The presented model suggests a path of food behavior change, however what the path looks like is largely dictated by the set of intersecting influences (couple’s food system, gendered experience of nutrition care, dominant values, and physical, financial, and social resources). The present work was focused on elucidating process and not outcomes. Development of each influence and examining how it affects outcomes related the individual’s food system, health, and bereavement process would expand the utility of the model. Finally, the category disrupted scripts relates to the effects on the household food system due to a change in social context and may be useful to consider when studying other changes in social context. The concept may be most relevant for changes that involve the reduction of members in the household such as separation, divorce, and children leaving home.

Conclusion

A theoretical model was identified that describes the process of the food behavior changes seen in widowhood. Two stages were identified, one transitory, and the other adaptive, leading to new ways of feeding the self. Several influences on how this process occurs for an individual were also elucidated. Thus, the changes in eating behavior with widowhood are very individual. This model can serve as a conceptual framework in future research focusing on food behaviors among older widowed women. Future work to confirm and expand this model is also needed. This model can also be used by practitioners to provide a better understanding of the food behavior transitions seen in widowhood and how to better support eating behavior during this lifestage. (Word count: 7659)

References

- Atchley RC. Social forces of aging: an introduction to social gerontology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bates CJ, Benton D, Biesalski HK, Staehelin HB, van Staveren W, Stehle P, et al. Nutrition and aging: A consensus statement. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2002;6(2):103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brisette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar R. A realist theory of science. Leeds, UK: Leeds Books Ltd; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Jastran M, Devine CM. How adults construct evening meals: Scripts for food choice. Appetite. 2008;51(3):654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, Bodnar-Deren S. Gender, Aging and Widowhood. In: Ulhenberg P, editor. International handbook of population aging. 2009. pp. 705–727. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers P. Older widows and the life course: Multiple narratives of hidden lives. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cheek C. Passing over: Identity transition in widows. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2010;70(4):345–364. doi: 10.2190/AG.70.4.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin AI, Forouhi NG, Surtees P, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Social relationships and healthful dietary behavior: Evidence from over-50s in the EPIC cohort, UK. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;100(Jan):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors M, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Devine CM. Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite. 2001;36(3):189–200. doi: 10.1006/appe.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daly KJ. Qualitative methods for family studies and human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- DeVault M. Feeding the family: The social organization of caring as gendered work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Furst T, Connors M, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Winter Falk L. Food choice: A conceptual model of the process. Appetite. 1996;26(3):247–266. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Li S, Zheng Y. Predictors of nutritional status among community-dwelling older adults in Wuhan, China. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(08):1189–1196. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson RO, Stroebe MS. Bereavement in late life: Coping, adaptation, and developmental influences. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heuberger R, Wong H. The association between depression and widowhood and nutritional status in older adults. Geriatric Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2014.06.011. Available online 29 July 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstein JA, Gubrium JF. The active interview. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CS. Nutritional considerations for bereavement and coping with grief. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2002;6(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J, Suzuki T, Kumagai S, Shinkai S, Yukawa H. Risk factors for dietary variety decline among Japanese elderly in a rural community: a 8-year follow-up study from TMIG-LISA. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;60(3):305–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Cho E, Grodstein F, Kawachi I, Hu FB, Colditz GA. Effects of marital transitions on changes in dietary and other health behaviors in US women. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34(1):69–78. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locher JL, Robinson CO, Bailey FA, Carroll WR, Heimburger DC, Saif MW, Ritchie CS. Disruptions in the organization of meal preparation and consumption among older cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(9):967–974. doi: 10.1002/pon.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopata HZ. Self-identity in marriage and widowhood. The Sociological Quarterly. 1973;14(3):407–418. [Google Scholar]

- Lopata HZ. Current widowhood: Myths & realities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Matthews A. Widowhood in Later Life. Toronto: Butterworths; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Matthews A. Widowhood: Dominant renditions, changing demography and variable meaning. In: Neysmith SM, editor. Critical Issues for Future Social Work Practice with Aging Persons. New York: Columbia University Press; 1999. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Situating grounded theory within qualitative inquiry. In: Schreiber RS, Stern PN, editors. Using Grounded theory in Nursing. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2001. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH, Lueger RJ, Kelber ST, Prigerson HG. Spousal bereavement in older adults: Common, resilient, and chronic grief with defining characteristics. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(4):332–341. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243890.93992.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Bell RA. Self-management of nutritional risk among older adults: A conceptual model and case studies from rural communities. Journal of Aging Studies. 1998;13(4):351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt SA, McDonald J, Arcury TA, Bell RA, Vitolins MZ. Nutritional self-management of elderly widows in rural communities. The Gerontologist. 2000;40(1):86–96. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud-Simon A. Virtual clinical nutrition university: Malnutrition in the elderly, epidemiology and consequences. e-SPEN, the European e-Journal of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism. 2009;4(2):e86–e89. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom CA, Whittington FJ. The effects of bereavement on eating behaviors and nutrient intakes in elderly widowed persons. Journal of Gerontology. 1993;48(4):S223–S229. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer A. Realism and social science. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert L. Household food strategies and the reframing of ways of understanding dietary practices. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2008;47(3):254–279. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar DR, Schultz R, Shahar A, Wing RR. The effect of widowhood on weight change, dietary intake, and eating behavior in the elderly population. Journal of Aging and Health. 2001;13(2):189–199. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, Zisook S, Neimeyer R, Duan N, Keshaviah A. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM_5. Depression and Anxiety. 2011;28(2):103–117. doi: 10.1002/da.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman PR. Widow to widow. New York: Brunner-Rouledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Constructing food choice decisions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38(1):37–46. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Bove CF, Rauschenbach BS. Commensal careers at entry into marriage: establishing commensal units and managing commensal circles. The Sociological Review. 2002;50(3):378–397. [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Kettel Khan L, Bisogni C. A conceptual model of the food and nutrition system. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;47(7):853–863. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death studies. 1999;23(3):197–224. doi: 10.1080/074811899201046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesnaver E, Keller HH. Social Influences and Eating Behavior in Later Life: A Review. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2011;30(1):2–23. doi: 10.1080/01639366.2011.545038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesnaver E, Keller HH, Sutherland O, Maitland SB, Locher JL. Alone at the table: food behavior and the loss of commensality in widowhood. 2015 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv103. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells YD, Kendig HL. Health and well-being of spouse caregivers and the widowed. The Gerontologist. 1997;37(5):666–674. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.5.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Aragaki A, Mouton CP, Evenson KR, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Loevinger BL. The effects of widowhood on physical and mental health, health Behaviors, and health outcomes: The women’s health initiative. Health Psychology. 2003;22 (5):513–522. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine. 1995;41(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SS-L. Doctoral dissertation. University of Guelph; Guelph, Ontario: 2005. A grounded theory study of appetite in frail, community-living seniors. [Google Scholar]