Abstract

Background and Purpose

The Stroke Health and Risk Education (SHARE) Project was a cluster-randomized, faith-based, culturally-sensitive, theory-based multicomponent behavioral intervention trial to reduce key stroke risk factor behaviors in Hispanics/Latinos and European Americans.

Methods

Ten Catholic churches were randomized to intervention or control group. The intervention group received a 1-year multicomponent intervention (with poor adherence) that included self-help materials, tailored newsletters, and motivational interviewing counseling calls. Multilevel modeling, accounting for clustering within subject pairs and parishes, was used to test treatment differences in the average change since baseline (ascertained at 6 and 12 months) in dietary sodium, fruit and vegetable intake, and physical activity, measured using standardized questionnaires. A priori, the trial was considered successful if any one of the three outcomes was significant at the 0.05/3 level.

Results

Of 801 subjects who consented, 760 completed baseline data assessments, and of these, 86% completed at least one outcome assessment. The median age was 53; 84% were Hispanic/Latino; 64% were women. The intervention group had a greater increase in fruit and vegetable intake than the control group (0.25 cups per day (95% CI: 0.08, 0.42), p = 0.002), a greater decrease in sodium intake (−123.17 mg/day (−194.76, −51.59), p=0.04), but no difference in change in moderate or greater intensity physical activity (−27 MET-minutes per week (−526, 471), p=0.56).

Conclusions

This multicomponent behavioral intervention targeting stroke risk factors in predominantly Hispanics/Latinos was effective in increasing fruit and vegetable intake, reaching its primary endpoint. The intervention also seemed to lower sodium intake. Church-based health promotions can be successful in primary stroke prevention efforts.

Keywords: stroke, prevention, behavioral intervention, clinical trial, risk factors, hypertension

Introduction

Hispanics/Latinos, now the largest minority group in the US, have a higher proportion of poorly controlled blood pressure (BP)1 and a greater burden of stroke than non-Hispanic whites.2 BP, a potent cardiovascular risk factor, is modified by behaviors such as diet, physical activity, and medication adherence. Because of the higher prevalence of risk factors, less available preventive services, and less favorable diet and exercise profile of Hispanics/Latinos, the need for culturally-sensitive preventive programs has been stressed.3, 4 Although many studies have been conducted in African American churches,5-7 few faith-based interventions have been conducted for Hispanics/Latinos, the majority of whom are Catholic, or a mixed group of Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic whites.8 The results of studies conducted in Protestant African American churches may not translate to the Hispanic/Latino community where culture and attitudes about health and lifestyle differ.4 Furthermore, implementation of church-based interventions may differ in Catholic churches which have a different structure and policies. We therefore designed the Stroke Health and Risk Education (SHARE) project, a church-based, cluster-randomized, behavioral intervention to reduce stroke risk through reduction in sodium intake, increase in fruit and vegetable intake, and increase in physical activity in Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic whites in a biethnic community. Cluster randomization on the parish level allowed us to encourage social and environmental change in the parishes, and decreased the risk of contamination of controls by intervention subjects. We report here the main results of this NIH-funded trial.

Methods

Overview

SHARE was an NIH-funded, peer-reviewed, cluster-randomized, church-based primary prevention trial that targeted key behavioral stroke risk factors. Details about the design of SHARE have been previously published,9 and additional details are found in the Supplemental materials. Briefly, friend or family member pairs were enrolled (2011-2012) from 10 Catholic parishes within the Diocese of Corpus Christi, Texas that were randomized to either the intervention or control group. This community consists mainly of non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics/Latinos. The Hispanics/Latinos, almost all of whom (96%) are US citizens, are predominantly Mexican-American and are for the most part non-immigrant.10

The intervention group received a one-year multi-component intervention at the individual level including culturally-sensitive self-help materials (healthy eating guide, physical activity guide with pedometer, motivational short film, and photonovella about BP control), up to five motivational interviewing calls, two tailored newsletters, and an approximately 2 hour workshop designed to teach pairs to provide each other with autonomy supportive counseling.9 Materials included relevant biblical quotations and prayers to provide religious relevance and motivation. Motivational interviewing calls were conducted by personnel trained in motivational interviewing and the SHARE intervention.9 On the cluster level, environmental and social change at parishes were also promoted through encouragement of availability of low sodium foods and fruits and vegetables at parish functions and programs to encourage healthy cooking and physical activity. The control subjects received skin cancer awareness materials or sunblock at 3 and 9 months to maintain contact every three months, including assessments. They also received holiday cards. The project was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from each individual subject. The trial was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01378780).

Eligibility

Subjects were eligible if they were Hispanic/Latinos or non-Hispanic white parishioners of a participating parish, 18 years or greater, spoke English or Spanish, were permanent residents of the Corpus Christi area, and were able to identify a partner with whom to enroll (this was relaxed toward the end of the study where the study team helped facilitate pairs on a few occasions). Known pregnancy was exclusionary.

Assessments

Home visits, conducted in English or Spanish, with computer-assisted interviews, were used to obtain baseline and 12 month follow-up data. Six month outcomes were assessed typically by phone. At all three time points, assessments included (1) the Block 2005 Food Frequency Questionnaire, a widely used questionnaire that has been validated in Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic whites,11-13 modified for a 6-month reference period and to include foods often eaten by Hispanic/Latino populations, and (2) the modified Stanford 7-day Physical Activity Recall Instrument, which assesses vigorous and moderate activity levels from work and leisure-time activities14 and has been validated against biological measures and used in Hispanics/Latinos and non-Hispanic whites.15, 16 At baseline and 12 months, the following assessments were also made in both groups: (1) BP (the average of the last two of three measures) using an automated device (OMRON-HEM-780) and usual techniques,17 (2) fasting blood draw for a lipid panel, glucose, and glycosylated hemoglobin, (3) height and weight, (4) waist circumference, (5) BP medication adherence question (“How often in a typical week have you missed a prescribed dose of your BP medicine or medicines?” assessed with a 5-point response scale ranging from “never” to “very often”)18, (6) Self-Determination Theory measures were assessed as exploratory outcomes and for tailoring purposes and included: modified versions of the Health-Care Climate Questionnaire19 (modified to refer to support from an “important other”), Perceived Competence Scale,19 and Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (modified to refer to the three specific primary outcome measures)19 and a relatedness questionnaire.20 At baseline, the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale, a 10-item tool to assess for social desirability response bias, was also administered.21 As a persistence test of the primary outcomes, the Block and Stanford questionnaires were also administered by phone to only the intervention group at 18 months.

Outcomes

Three pre-specified co-primary outcomes were: dietary sodium, dietary fruit and vegetable intake, and moderate or greater physical activity. The intervention was determined a priori to be deemed successful (‘primary endpoint’) if at least one of these outcomes was significant at a level of 0.05/3 to correct for multiple testing. The secondary outcome was systolic BP. Biological exploratory outcomes were diastolic BP, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin, BMI; behavioral exploratory outcomes were total dietary fat, saturated fat, BP medication adherence, and measures of the theory-related intermediate outcomes: the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire, Perceived Competence Scale, and Health-Care Climate Questionnaire.19

Statistical analysis

Details are found in the supplement. We calculated that 5 churches in each group with an average of 40 pairs each (i.e. 800 subjects total) would need to be randomized to detect the projected differences in change in at least one of the primary outcomes.

Repeated measures models for longitudinal data22 were used to assess treatment differences in change from baseline for all outcomes by testing a time by treatment interaction term in a model that included up to three observed measures per participant (baseline, 6 month and 12 month). This approach enabled us to conduct an intention to treat analysis where all observed data were incorporated in the model fitting under the assumption that missing data from subjects who dropped out were missing at random. Specifically, the approach compared the average of the difference between baseline and 6 and 12 month follow-up data when both were available, and the difference between baseline and 6 or 12 month follow-up when only one follow-up measure was available. Those few with only baseline data were also included in the models using maximum likelihood estimates.22, 23 Adjusted analyses were also performed accounting for age, sex, ethnicity, education, and, for the behavioral outcomes, social desirability to response bias (Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale) given that subjects were not blind to treatment condition and because these factors may explain variance in the outcomes and thus increase power. Standard procedures were used to eliminate dietary records that appeared invalid24 and to eliminate outliers for individual measures. Finally, to examine persistence of behavior changes, we incorporated data from the 18 month visit among the treatment group, and used data from all visits in both treatment groups within multilevel models to estimate the average of each outcome by treatment group for each visit. SAS version 9.3 was used for all data analyses.

Results

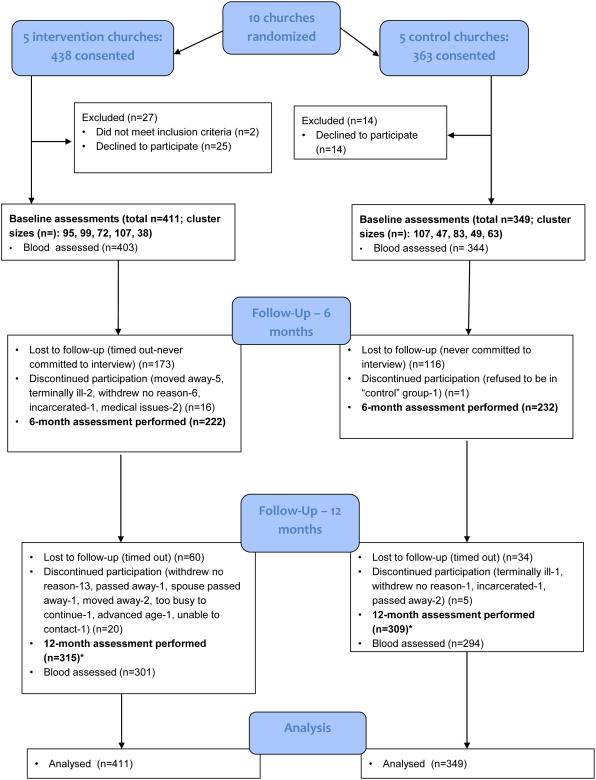

Of the 801 people consented, 760 (95%) were randomized and underwent a baseline assessment. Of these, 653 (86%) completed at least one outcome assessment; 28 (3.7%) completed only the 6 month assessment; 196 (25.8%) completed only the 12 month visit, and 428 (56.3%) completed both the 6 month and 12 months assessments. Overall, those who did not complete either the 6 or 12 month assessments were similar to the completers but tended to be a little younger (see Supplemental Table I). The CONSORT flow diagram is found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

*Many subjects who did not participate in the 6 month assessment did participate in the 12 month assessment.

Baseline characteristics of the intervention and control group are presented in Table 1; no differences by treatment group were found (p > 0.05 for all). Median age was 53 years (interquartile range: 44, 64). The majority of subjects were female (64%) and, by self-report, Hispanic/Latino (84%). Partners were most commonly spouses (56%), followed by a friend (19%), blood relative (18%), or a study-provided partner (6%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study sample (N=760) by treatment group.

| Treatment (N=411) | Control (N=349) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics, N (%) unless noted | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 53 (44, 65) | 51 (43, 63) |

| Female | 256 (62.3) | 229 (65.6) |

| Married or living together | 310 (75.4) | 233 (66.8) |

| Education | ||

| <HS | 51 (12.4) | 50 (14.3) |

| HS | 119 (29.0) | 101 (28.9) |

| Some College | 154 (37.5) | 116 (33.2) |

| College or more | 87 (21.2) | 82 (23.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 69 (16.8) | 50 (14.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 339 (82.5) | 297 (85.1) |

| Refused | 3 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) |

| Income ≥$30K | 195 (47.4) | 162 (46.4) |

| Has Health Insurance | 335 (81.5) | 288 (82.5) |

| Current Employment Status | ||

| Full time | 207 (50.5) | 185 (53.0) |

| Part time | 44 (10.7) | 34 (9.7) |

| Not employed | 159 (38.8) | 130 (37.2) |

| PHQ-2 screen, median (IQR) | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 2) |

| Eat fast food | ||

| Never | 63 (15.3) | 56 (16.0) |

| <1/week | 54 (13.1) | 51 (14.6) |

| 1-2/week | 173 (42.1) | 157 (45.0) |

| 3-4/week | 88 (21.4) | 57 (16.3) |

| 5 or more/week | 33 (8.0) | 28 (8.0) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors , n yes (%) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 24 (5.8) | 19 (5.4) |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 12 (2.9) | 6 (1.7) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 23 (5.6) | 14 (4.0) |

| Diabetes | 103 (25.1) | 69 (19.8) |

| Heart Attack | 18 (4.4) | 10 (2.9) |

| Hypertension | 198 (48.2) | 157 (45.0) |

| Sleep Apnea | 52 (12.7) | 30 (8.6) |

| Stroke or TIA | 22 (5.4) | 15 (4.3) |

| Current smoking | 31 (7.5) | 32 (9.2) |

| Biological or measured exploratory outcomes, median (IQR) unless noted | ||

| Weight (kg) | 85.1 (72.1, 100.7) | 81.0 (68.6, 97.5) |

| Height (meters) | 1.63 (1.56, 1.70) | 1.61 (1.56, 1.69) |

| Body mass index | 31.8 (27.8, 36.4) | 30.5 (26.9, 36.3) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 105.0 (95.5, 115.0) | 103.0 (94.0, 115.0) |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 187 (162, 212) | 180 (160, 212) |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 50 (42, 61) | 52 (44, 60) |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 107 (87, 128) | 102 (83, 127) |

| Non-HDLChol (mg/dL) | 135 (108, 161) | 128 (104, 156) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 121 (88, 172) | 119 (87, 158) |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 96 (88, 110) | 94 (87, 106) |

| HbA1C (%) | 5.9 (5.6, 6.3) | 5.8 (5.6, 6.2) |

| Blood pressure category, N (%) | ||

| Normal | 142 (34.6) | 119 (34.1) |

| Prehypertension | 158 (38.5) | 142 (40.7) |

| Stage I | 82 (20.0) | 72 (20.6) |

| Stage II | 28 (6.8) | 16 (4.6) |

PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire

IQR: interquartile range

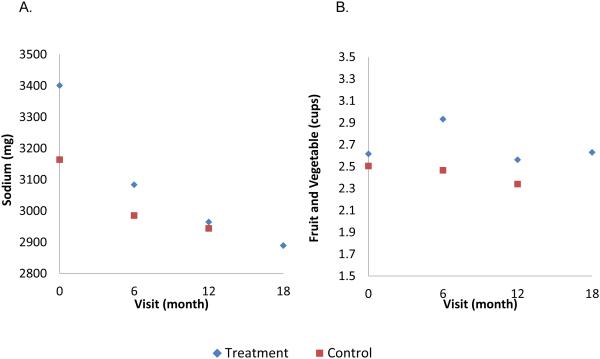

For the primary outcomes, change from baseline to follow-up was greater for fruit and vegetable intake (0.25 cups per day (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.08, 0.42), p = 0.002) and sodium (−123 mg/day (95% CI: −195, −52), p=0.04) in the intervention than control group. No treatment effect was identified for moderate or greater intensity physical activity (27 MET-minutes per week (95% CI: −526, 471) (Table 2). In the intervention group, the intake of fruits and vegetables and sodium at 18 months was similar to the 12 month data (Figure 2), in support of persistence of a treatment effect.

Table 2.

Baseline measures, change from baseline, and treatment effect for the primary and secondary outcomes.

| Treatment (n=411) | Control (n=349) | Treatment Difference in change from baseline (95%CI) |

pvalue | Adjusted pvalue** |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Baseline, mean (StdErr of mean) |

Change from baseline (95%CI) |

Baseline, mean (StdErr of mean) |

Change from baseline (95%CI) |

|||

| Fruit + vegetable, cups per day |

2.62 (0.09) | 0.11 (−0.00, 0.23) | 2.51 (0.10) | −0.14 (−0.26, −0.01) | 0.25 (0.08, 0.42) | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Sodium, mg per day |

3137 (76) | −278 (−355, −201) | 2988 (83) | −155 (−232, −78) | −123 (−195, −52) | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| MET-minutes per week* |

2717 (300) | −163 (−517, 192) | 3001 (310) | −135 (−497, 227) | −27 (−526, 471) | 0.56 | 0.72 |

| SBP, mmHg | 125.9 (1.3) | −0.38 (−3.23, 2.47) | 125.2 (1.3) | −0.08 (−2.90, 2.74) | −0.30 (−3.81, 3.21) | 0.86 | 0.60 |

| DBP, mmHg | 79.1 (0.9) | −0.98 (−2.00, 0.03) | 79.3 (0.9) | 0.04 (−0.98, 1.07) | −1.03 (−2.46, 0.40) | 0.16 | 0.17 |

Of moderate or higher intensity

Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity. Self-reported outcomes also adjusted for social desirability.

Figure 2.

Average sodium (A) and fruit and vegetable (B) intake by treatment group and visit.

Note y-axis does not start at 0

No treatment effect was identified for the secondary outcome, systolic BP (Table 2). Of the biological exploratory outcomes, total dietary fat and saturated fat decreased in the treatment group more than the control group (Supplemental Table II). These results were borderline significant in unadjusted analysis, and significant (p<0.05) after adjustment for age, sex, education, and social desirability. No treatment effect was found related to weight, waist circumference, glucose, HbA1C, or lipid panel results (Supplemental Tables II and III). Similarly, no treatment effect was found with respect to medication adherence in those taking BP medications at baseline (Supplemental Table III). ICCs for the primary outcomes are reported in Supplemental Table IV. Within church and pair, ICCs were < 0.05.

While the vast majority of the Self-Determination Theory-related exploratory outcomes had more favorable changes supportive of behavior change among the treatment group, only the changes in perceived competence to eat more fruits and vegetables (change from baseline 0.21 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.37) on a 7-point scale, p=0.01) and lack of motivation for dietary change (−0.29 (−0.52, −0.05) on a 7-point scale, p=0.02 (“amotivation” subscale of the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire) were statistically significant.

Table 3 presents information about the use of the intervention components by the intervention subjects. Most subjects completed at least one motivational interviewing call (74%), and, based on self-report, read one or both newsletters (63%), used the healthy eating guide (80%), and the exercise guide (55%). Among the intervention participants, adjusted for age, sex, social desirability, ethnicity, and education, there was no association between the participants recalling that their parish had an activity supportive of a healthy diet or exercise and the three primary outcomes.

Table 3.

Percent of participants who recall and/or used intervention components, among those who responded to process evaluation questionnaire (n=314).

| Variable | % |

|---|---|

| Individual-level process | |

| Used healthy eating guide | 80.0 |

| Used exercise guide | 54.5 |

| Watched short film | 23.3 |

| Read photonovella | 32.5 |

| Recalls receiving MI Calls | |

| 0 | 23.2 |

| 1-3 | 54.1 |

| 4-5 | 22.6 |

| Number of MI calls completed | |

| 0 | 26.1 |

| 1-3 | 63.7 |

| 4-5 | 10.2 |

| Tailored newsletters | |

| Did not recall receiving any | 25.2 |

| Did not read any of received | 11.8 |

| Read 1 | 20.4 |

| Read 2 | 42.7 |

| Pair-level process | |

| Talked with Partner about SHARE goals | |

| 2 or more per week | 35.5 |

| 1/week to 1/month | 42.2 |

| < 1 per month | 22.4 |

| Exercised with partner | |

| 2 or more per week | 26.8 |

| 1/week to 1/month | 24.3 |

| < 1 per month | 48.9 |

| Cooked with partner | |

| 2 or more per week | 49.8 |

| 1/week to 1/month | 21.4 |

| < 1 per month | 28.8 |

| Church-level process | |

| Workshop* | |

| Recalls attending | 34.4 |

| Did not attend but used mailed workbook | 15.0 |

| Attendance recorded | 38.5 |

| Recalls parish activities* | |

| None | 31.8 |

| Activities supportive of exercise | 64.3 |

| Activities supportive of healthy diet | 33.4 |

| Both types of activities | 29.6 |

not exclusive categories, do not add to 100

Discussion

This large cluster-randomized trial showed that this multicomponent behavioral intervention was effective in increasing fruit and vegetable intake among Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic white Catholic parishioners. The trial successfully reached its primary endpoint. The intervention also seemed to lower sodium intake (p=0.04), despite missing its statistical threshold. Despite the positive effect on fruit and vegetable intake, inspection of the differences by group through time suggests little increase in the intervention group and a decline in the control group. Thus some of the effect may have been staving off a decline in fruit and vegetable intake. In support of a true intervention effect is the increase in perceived competence to eat fruits and vegetables and increased motivation for eating a healthy diet, intermediate outcome measures. While the estimated magnitude of the difference in fruit and vegetable intake was modest, observing a treatment difference is promising and is in keeping with modest effects seen in other church-based interventions based on self-determination theory.6, 7 Similarly, the magnitude of sodium reduction while small was also encouraging. Although the importance of a lower sodium diet has come into question, the most recent evidence continues to support the benefits of a lower sodium diet on stroke risk factors.25, 26 Furthermore, while the primary benefits were identified at the conclusion of the intervention, persistence testing suggested that the improvements in both dietary measures likely lasted at least another 6 months. This, in conjunction with evidence of change in the Self Determination Theory constructs (perceived competence and motivation) known to impact healthy behavioral choices, is encouraging for long-term benefits of this intervention.

The intervention showed no effect on the third co-primary outcome, physical activity. However, physical activity among the subjects of this trial at baseline was much higher than would have been expected based on national data,27 raising the possibility of a ceiling effect.

The most clinically significant biological marker of stroke risk, BP, was not affected by the intervention; although we lacked power to detect this association, hence systolic and diastolic BP were secondary and exploratory outcomes. Furthermore, baseline BPs were relatively low, and our intervention was only moderate in intensity, particularly for BP. Although, four MI sessions in a year that targeted medication adherence has been shown to reduce systolic BP among hypertensive African Americans28 and five calls targeting lifestyle change has also been shown to reduce blood pressure in treated hypertensive patients.29

To our knowledge, this trial represents the first church-based behavioral intervention efficacy trial to target multiple stroke risk behaviors in Hispanics/Latinos, a growing and aging minority group. While the intervention was sensitive to Hispanic/Latino culture, it was also designed to be sensitive to non-Hispanic whites to improve the generalizability of the intervention and ability to disseminate the program within churches more broadly.

Limitations to this study exist. The primary outcomes were self-reported measures, and thus subject to measurement error and response bias, given the inability to mask the intervention. We did however account for social desirability response bias with the use of the Marlowe-Crowne scale.21, 30 Outcomes assessors were also not masked. We also used a food frequency questionnaire rather than a 24 hour dietary recall or urinary sodium measures, due to greater feasibility of the food frequency questionnaires especially given our large sample. We did not validate the dietary or physical activity measures against biological measures in this population, although they have been previously validated.15, 31, 32 While seasonal variability in dietary and physical activity habits can influence behaviors, our one year time frame should have mitigated against this. Overall, engagement in the intervention by subjects was less than anticipated. While motivational interviewing has been shown to be effective,33, 34 we found reaching subjects by phone to be quite challenging. Many subjects did not participate in the 6 month assessment; although most (82%) completed the 12 month assessment.

Summary/Conclusions

This rigorously developed and tested behavioral intervention intended to reduce stroke risk factors showed that a Catholic Church-based intervention can successfully recruit Hispanics/Latinos and can improve health behaviors in a predominantly Hispanic/Latino population. Stroke-related health promotion interventions that target Hispanics/Latinos are needed. Given the complexity of the intervention and modest effect sizes, suggesting that this particular intervention may not be reasonable to disseminate, additional research is needed to identify behavioral interventions that are potent yet practical to implement widely.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the SHARE Community Advisory Board and the Diocese of Corpus Christi for their partnership.

Funding: This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS062675 and R01NS062675-S; multiple PIs: Morgenstern/Brown). The research reported in this publication was also supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000433. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration-URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT01378780.

Disclosures: None.

Reference List

- (1).Crespo CJ, Keteyian SJ, Heath GW, Sempos CT. Leisure-time physical activity among US adults. Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:93–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sánchez BN, Brown DL, Zahuranec DB, Garcia N, et al. Persistent ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in Mexican Americans. Ann Neurol. 2013;74:778–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liao Y, Tucker P, Okoro CA, Giles WH, Mokdad AH, Harris VB, et al. REACH 2010 Surveillance for Health Status in Minority Communities --- United States, 2001--2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2004;53:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:593–625. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, De AK, McCarty F, Dudley WN, et al. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: results of the Eat for Life trial. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1686–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, DiIorio C, Blisset D, Rahotep S, et al. Healthy Body/Healthy Spirit: a church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:562–73. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Perl P, Greely JZ, Gray MM. What Proportion of Adult Hispanics Are Catholic? A Review of Survey Data and Methodology. J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45:419–36. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Brown DL, Conley KM, Resnicow K, Murphy J, Sánchez BN, Cowdery JE, et al. Stroke Health and Risk Education (SHARE): Design, methods, and theoretical basis. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:721–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Pew Research Center Appendix Tables. Hispanic Trends web site. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/08/29/appendix-tables-4/. Accessed October 27, 2014.

- (11).Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:453–69. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Block G, Wakimoto P, Jensen C, Mandel S, Green RR. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for Hispanics. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Huang MH, Schocken M, Block G, Sowers M, Gold E, Sternfeld B, et al. Variation in nutrient intakes by ethnicity: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2002;9:309–19. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the Five-City Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:91–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Blair SN, Haskell WL, Ho P, Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Vranizan KM, Farquhar JW, et al. Assessment of habitual physical activity by a seven-day recall in a community survey and controlled experiments. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:794–804. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Mitchell BD, Kammerer CM, Schneider JL, Perez R, Bauer RL. Genetic and environmental determinants of bone mineral density in Mexican Americans: results from the San Antonio Family Osteoporosis Study. Bone. 2003;33:839–46. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, Falkner BE, Graves J, Hill MN, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: Part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2005;45:142–61. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000150859.47929.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. Mechanisms for Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Glycemic Control in Middle-aged and Older Americans in the Health and Retirement Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1853–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Williams GC, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Health-Care, Self-Determination Theory Questionnaire Packet. Self-Determination Theory questionnaires web site. http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/measures/health.html. Accessed September 7, 2007.

- (20).La Guardia JG, Ryan RM, Couchman CE, Deci EL. Within-person variation in security of attachment: a self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:367–84. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Strahan RF. Regarding some short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Psychol Rep. 2007;100:483–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.2.483-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal data. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. J. Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, et al. Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires : the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Lower Levels of Sodium Intake and Reduced Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation. 2014;129:981–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cobb LK, Anderson CAM, Elliott P, Hu FB, Liu K, Neaton JD, et al. Methodological Issues in Cohort Studies That Relate Sodium Intake to Cardiovascular Disease Outcomes: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:1173–86. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tucker JM, Welk GJ, Beyler NK. Physical activity in US adults: compliance with the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:454–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ogedegbe G, Chaplin W, Schoenthaler A, Statman D, Berger D, Richardson T, et al. A Practice-Based Trial of Motivational Interviewing and Adherence in Hypertensive African Americans. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:1137–43. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Woollard J. A controlled trial of nurse counselling on lifestyle change for hypertensives treated in general practice: preliminary results. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:466–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hebert JR, Clemow L, Pbert L, Ockene IS, Ockene JK. Social desirability bias in dietary self-report may compromise the validity of dietary intake measures. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:389–398. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Coates RJ, Eley JW, Block G, Gunter EW, Sowell AL, Grossman C, Greenberg RS. An evaluation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary intake of specific carotenoids and vitamin E among low-income Black women. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:658–671. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Huang MH, Harrison GG, Mohamed MM, Gornbein JA, Henning SM, Go VL, Greendale GA. Assessing the accuracy of a food frequency questionnaire for estimating usual intake of phytoestrogens. Nutr Cancer. 2000;37:145–154. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC372_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:843–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Rubak S, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:305–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.