Abstract

Poor appetite is a common problem in older people living at home and in care homes, as well as hospital inpatients. It can contribute to weight loss and nutritional deficiencies, and associated poor healthcare outcomes, including increased mortality. Understanding the causes of reduced appetite and knowing how to measure it will enable nurses and other clinical staff working in a range of community and hospital settings to identify patients with impaired appetite. A range of strategies can be used to promote better appetite and increase food intake.

Before reading this article do time out 1.

1. Time out. Consequences.

Consider what the consequences of poor appetite might be for an older person.

Introduction

Appetite is the desire to fulfil a bodily need and can be divided into three components: hunger, satiation and satiety. Hunger is the sensation that promotes food consumption, satiation is the sensation of fullness during eating that leads to meal termination and satiety is the fullness that exists between eating occasions (Mattes et al., 2005).

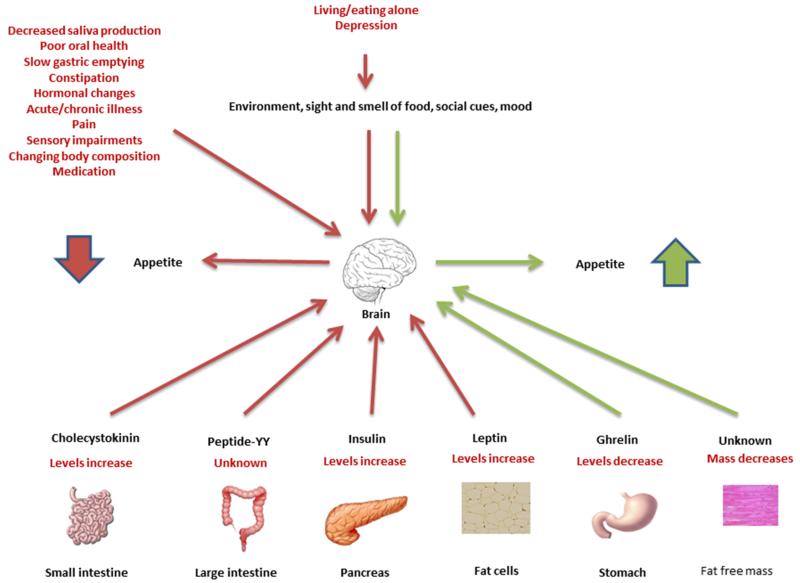

Control of appetite

Appetite regulation is complex and not completely understood. It has control systems linking the brain, digestive system, endocrine system and sensory nerves. These systems act to govern appetite both in the short term and the long term. In the short term appetite is thought to be mostly controlled by sensors in the gut that respond to the physical presence or absence of food, and to the different components of the food, such as fat or protein. In response to signals from these sensors the gut secretes a variety of hormones, e.g. ghrelin is secreted by the stomach in response to fasting and increases appetite, peptide-YY is secreted by the ileum and colon in response to food intake and suppresses appetite, and cholecystokinin is secreted by the small intestine in response to the presence of fat and protein and suppresses appetite. Insulin is secreted by the pancreas in response to high blood glucose and also suppresses appetite (Parker and Chapman, 2004). Different hormones are released before, during and after eating, controlling feeding behaviour and how much is eaten. In the long term appetite may be controlled by the composition of the body. Signals from the fat mass inhibit appetite through the hormone leptin secreted by fat cells. There is some early evidence that fat free mass may increase the desire to eat but the mechanism is unknown (Blundell et al., 2012). These short and long term systems can be thought of as homeostatic, maintaining the nutritional status of the body by helping it to meet its needs for energy and nutrients. These homeostatic systems can all be overridden by ‘pleasure’ signals, which are called hedonic systems.

For example, the smell of a favourite food or being offered a tasty treat can stimulate appetite and cause a person to eat when they don’t actually ‘need’ to. Mood is an important part of the hedonic system, but mood will affect appetite in different ways: some people eat more when sad or anxious, whereas for others these moods will suppress appetite. Social and environmental cues such as walking past a shop selling food or it being ‘mealtime’ can also stimulate appetite. Conversely, people may ignore their appetite and inhibit their own eating for various reasons, such as wanting to lose weight (Berthoud, 2011).

Appetite decline in older people

Many older people experience a decrease in appetite. This decline was first described as the ‘anorexia of ageing’ in 1988 by John Morley (Morley and Silver, 1988). Between 15% and 30% of older people are estimated to have anorexia of ageing, with higher rates in women, nursing home residents, hospitalised people and with increasing age (Malafarina et al., 2013). Reduced appetite can lead to reduced food and nutrient intake (Payette et al., 1995), increasing risk of weight loss and nutritional deficiencies (Wilson et al., 2005, Brownie, 2006). Nutritional deficiencies and weight loss have serious consequences for older people and these are summarised in table 1. Also older people may find it hard to regain lost weight (Roberts et al., 1994). Appetite may also decline acutely in response to acute illness. Detecting loss of appetite before weight loss and nutritional deficiencies occur will allow intervention at an early stage, preventing a decline in health.

Table 1.

Consequences of nutritional deficiencies and weight loss in older people

| Increased risk of | Impaired |

|---|---|

| Frailty | Wound healing |

| Falls | Immune function |

| Pressure sores | Quality of life |

| Longer length of hospital stay | |

| Osteomalacia | |

| Osteoporosis | |

| Hip fracture | |

| Muscle weakness | |

| Mortality |

Now do time out 2.

2. Time out. Awareness.

Think about the patients you are caring for now. How many of them do you think have impaired appetite? How do you know this?

Causes of reduced appetite in older people

There are many changes that occur with ageing that can be responsible for a decrease in appetite and these include changes to the physiology of the older body, changes in psychological functioning, changes in social circumstances, acute illness, chronic diseases and use of medication (Malafarina et al., 2013).

Physiological

The physiological changes that occur with ageing that can impair appetite include changes to the digestive system, hormonal changes, disease, pain, changes to the sense of smell, taste and vision and a decreased need for energy.

Changes to the digestive system can contribute to declining appetite. An estimated one third of people over 65 years old have reduced saliva production, causing difficulties in eating that may impair appetite (Ship et al., 2002). Decreased saliva production is not a part of normal ageing, and is most often caused by medication side effects (Ship et al., 2002). Older people are more likely to have poor dentition, and wearing dentures and chewing difficulties are both associated with loss of appetite (Lee et al., 2006). Poor oral health is more common in frail older people, reducing sense of taste and may contribute to poor appetite (Solemdal et al., 2012). Gastric emptying is slower in older people, so food remains in the stomach longer prolonging satiation and reducing appetite (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010). Constipation can cause reduced appetite (Landi et al., 2013) and is commonly reported by older people, with reported rates of between 30% and 40% of community dwelling older people and over 50% of nursing home residents complaining of chronic constipation (Gallagher and O’Mahony, 2009).

Changes in the levels and responsiveness to some of the hormones involved in appetite control have been found in older people. There is some evidence that fasting levels of ghrelin are lower (Di et al., 2008), fasting and postprandial levels of cholecystokinin are higher (de Boer et al., 2012), and baseline levels of leptin are higher in older people (de Boer et al., 2012). Additionally cholecystokinin suppresses appetite more strongly in older people (Parker and Chapman, 2004). All these hormonal changes will contribute to appetite impairment with ageing.

Any acute illness can impair appetite, especially acute infection (Langhans, 2007). Many chronic diseases can also worsen appetite and these include cardiac failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, chronic liver disease, Parkinson’s disease and cancer. All of these conditions are more prevalent in older people. The anorexia in both acute and chronic disease is mainly caused by pro-inflammatory cytokines (Langhans, 2007), and also by nausea, sensory changes (Lee et al., 2006) and medication side effects. Chronic disease can also impair appetite through impaired dexterity and pain. Impaired dexterity interferes with the eating process, food takes longer to eat and may go cold, reducing the appetite usually stimulated during eating. Chronic pain is associated with poor appetite, and since as many as half of all community dwelling older people suffer from chronic pain (Bosley et al., 2004) this may contribute significantly to loss of appetite in older people. Pain is mostly commonly from the back and knee (Patel et al., 2013).

Taste, smell and vision are all involved with the enjoyment of food, and impairments of these senses that occur with ageing can cause reduced appetite. The smell of food stimulates appetite, and taste promotes the enjoyment of food and further stimulates appetite during eating. Many older people have impaired sense of smell and taste which will cause them to have worse appetite (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010). Good eyesight helps to stimulate appetite and older adults with poor vision are more likely to report poor appetite (Lee et al., 2006). Visual impairment is increasingly common with increasing age, with one in five aged over 75 years and one in two aged over 90 years are reported as having sight loss (RNIB, 2014).

The energy needs of an individual are determined by their body composition, especially the fat free mass (all the body components that are not fat, including muscle, bones and organs), and their levels of physical activity (Campbell et al., 1994). Most older people lose fat free mass as they age, with skeletal muscle being lost at a rate of approximately 1% per year in the over 70s (Goodpaster et al., 2006), and many are less physically active (Taylor et al., 2004). Therefore older people have lower requirements for energy which may contribute to a reduction in appetite. This will vary between individuals reflecting differences in their body composition and levels of physical activity.

Now do time out 3.

3. Time out. Physiological causes.

Pause to review what you have learned about the physiological causes of impaired appetite. Make a list of the main causes and check your answers. Have you or your relatives noticed changes to your appetite due to changes in health?

Psychosocial

Appetite is strongly influenced by the environment and mood. Therefore many of the psychological and social changes that can occur with ageing will influence appetite.

Depression is known to impair appetite (Engel et al., 2011) and is common in older people, with reported rates of 9% in community dwelling older people, 27% in those who live in care homes in the UK (McDougall et al., 2007), and 24% in older inpatients (Goldberg et al., 2012). Therefore depression may cause reduced appetite in the older population. Patients with dementia can have reduced appetite (Ikeda et al., 2002). Delirium is associated with poor nutritional intake (Mudge et al., 2011) but it is not clear if this mediated via reduced appetite. Living and eating alone can cause reduced appetite, possibly because those who have difficulties with shopping and cooking lack support to overcome these problems and become less motivated to cook and eat. Additionally eating alone is less pleasurable and people living alone have fewer social cues to eat. As more than a third of over 65s and half of over 75s live alone (AGE UK, 2014) this may affect the appetite of many older people. Determination to eat to maintain weight and health is an important factor in the eating behaviour of older people, helping to overcome any reduction in appetite (Wikby and Fagerskiold, 2004). Finally, large portion sizes may be off-putting, particularly where standard portion sizes are used, such as in hospitals. A recent study that interviewed hospitalised older women found this was a common issue (Robison et al., 2014). Retirement can also alter meal patterns and food choices due to change in routine, location, social contact and finances (Alvarenga et al, 2009).

Now do time out 4.

4. Time out. Psychosocial risks.

Reflect on the patients you care for. Can you identify any with risk factors for developing poor appetite?

Pharmacological

Older adults are likely to be taking at least one medication (Qato et al., 2008). 250 commonly used drugs are known to alter sense of taste and smell or cause nausea, and may therefore reduce appetite (Schiffman, 1997). Some of drugs that can impair appetite are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Drugs that can impair appetite

| Class | Agents |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Ampicillin, macrolides, quinolones, Trimethoprim, Tetracycline, Metronidazole |

| Antifungals | Fluconazole, Posaconazole, Amphotericin, Caspofungin, Micafungin, Griseofulvin, Terbinafine, Itraconazole |

| Antivirals | Ganciclovir, Foscarnet sodium, Valganciclovir, Telbivudine, Boceprevir, Ribavarin |

| Antiparkinsons | Quinagolide |

| Muscle relaxants | Baclofen, Dantrolene sodium |

| Migraine medications | Eletriptan, Frovatriptan, Rizatriptan |

| Antihypertensives | Hydralazine hydrochloride, Iloprost |

| Diuretics | Amiloride hydrochloride |

| Statins | Atorvastatin |

| Heart failure medication | Angiotensin Converting Enzyme inhibitors |

| Antiarrhythmics | Adenosine, Dronedarone, Amiodarone, Propafenonen hydrochloride |

| Thyroid medication | Carbamiazole, Propylthiouracil |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Amitryptyline, Clomipramine, Dosulepin, Doxepin, Imipramine, Lofepramine, Nortriptyline, Trimipramine |

| Antipsychotics | Trifluoperazine, Aripiprazole, Risperidone |

| Mood stabilisers | Lithium carbonate, Lithium citrate |

| Hypnotics | Zaleplon, Zopiclone |

| Bronchodilators | Formoterol fumarate, Tiotropium |

| Anti-inflammatories | Celecoxib, Etoricoxib |

Figure 1 is a simplified diagram of appetite control and how it can change in older people.

Figure 1.

Control of appetite, with changes that can occur with ageing in red

Now do time out 5.

5. Time out. Appetite measurement.

Have you ever asked an older person about their appetite? Discuss with a colleague the challenges of measuring appetite in an older person.

Measurement of appetite

Measuring appetite is challenging because it is subjective and experienced differently by each individual. Previously appetite was inferred from the results of other measurements such as food intake, nutritional assessment, weight or body mass index (Mattes et al., 2005). Clinical laboratory studies have used visual analogue scales or a single question such as ‘how hungry are you right now?’ but these are not validated for use in other settings to measure usual appetite. The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ) was developed to predict >5% weight loss over six months in community dwelling older people and has four simple questions, see box 1. Patients identified as having poor appetite using this screening tool will need further investigation to identify the cause.

Box 1. The Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire.

- My appetite is

- very poor

- poor

- average

- good

- very good

- When I eat

- I feel full after only a few mouthfuls

- I feel full after eating a third of a meal

- I feel full after eating half a meal

- I feel full after eating most of a meal

- I hardly ever feel full

- Food tastes

- very bad

- bad

- average

- good

- very good

- Normally I eat

- less than one meal a day

- one meal a day

- two meals a day

- three meals a day

- four or more meals a day

Administration Instructions

Ask the subject to complete the questionnaire by circling the correct answers and then tally the results based upon the following numerical scale: a = 1, b = 2, c = 3, d = 4, e = 5. The sum of the scores for the individual items constitutes the SNAQ score.

SNAQ score < 14 indicates significant risk of at least 5% weight loss within six months in community dwelling people aged > 60 years.

Now do time out 6.

6. Time out. Management.

Before reading the next section think about the patients you care for who have poor appetite. Consider the reasons that their appetite might be poor and the ways in which you might help them to improve their appetite. What appetite promotion measures do you already use and what could supplement these in the future?

Management options for older people with poor appetite

The first line of treatment should always be to identify and treat any underlying cause.

Patients with a dry mouth can be helped by offering them regular sips of water, avoiding hard dry foods and using saliva replacement products (Gupta et al., 2006). Check the patient has dentures if needed and that they fit comfortably. The nurse can help the patient to maintain oral hygiene and refer to a dental hygienist if necessary. Treat constipation if present (Gallagher and O’Mahony, 2009). Acute infections should be treated as appropriate and chronic illnesses managed, with particular attention being paid to symptoms such as nausea and pain. If a patient has impaired smell or taste then appetite may be improved by enhancing the flavour of food. This can be done on an individual basis as likings for certain flavours will vary. The addition of extra salt and sugar is not recommended, but pepper, herbs and spices may all be safely used according to personal preference (Schiffman, 1997). Patients can also be encouraged to eat a wide variety of foods at each meal to help sustain appetite during the meal (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010). If a visual impairment is present then make sure the patient has the correct spectacles and is referred for further investigation if necessary. Using crockery of a colour that contrasts with the colour of the food and good lighting will also help the visually impaired patient, and plate sides and non-slip mats will promote independence, which should all improve appetite. Plate sides and non-slip mats will also benefit those patients with impaired dexterity (Connolly and Wilson, 1990).

Depression and dementia should be identified and managed appropriately. The diagnosis and management of delirium will be especially important in hospital patients. There is some preliminary evidence that coloured crockery can increase the dietary intake of older patients with dementia in hospital (Rossiter et al., 2014), encouragement, serving finger foods and physical assistance may also help. Older people who live alone can be encouraged to use lunch clubs and to eat meals with friends or family if possible. There are many recognised health benefits to increasing physical activity levels at all ages, including improved wellbeing, which may help to improve appetite (Netz et al., 2005). Behaviour change techniques to improve motivation to eat, such as setting goals, providing feedback and monitoring, and planning social support, could also be used (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2014). Serving smaller portions may tempt appetite but risks causing reduced food intake, this can be prevented by making sure the smaller portion is enriched, for example by adding cream, butter or cheese (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010). As many medications can reduce appetite (Table 2) reviewing a patient’s medication is useful if they have a poor appetite, as it may be possible to substitute one medication for another or stop it altogether

Having addressed possible causes of poor appetite we can now consider ways in which appetite can be improved whatever the cause. The environment in which food is served plays an important role in appetite and therefore improving this environment should help to improve appetite. There haven’t been any studies that have measured the effect of improving the mealtime environment on appetite, but a systematic review of mealtime interventions in care homes found that improving the dining environment tended to improve weight/weight status and food/calorie intake of residents. Improvements included using tablecloths, nice crockery, protected mealtimes, improved choice of and access to food and mealtime assistance (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010), and some or all of these could be used in UK care homes and hospitals. Community dwelling older people should be encouraged to take time to create a pleasant eating environment for themselves. There is evidence that food form has an effect on appetite: ‘beverage’ meals leave older people less satiated than ‘solid’ meals (Leidy et al 2010) and therefore using enriched soups or drinks may be useful in increasing the energy intake of someone with reduced appetite. It is important to ask patients, and their families, what foods they like to eat and what their usual meal patterns are. Trying to serve the most liked foods in a similar pattern to the patient’s usual one may help to stimulate appetite (Wikby and Fagerskiold, 2004). There is interest in using drugs or alcohol to stimulate appetite. Currently no drugs are licensed in the UK to improve appetite in older people and there is no evidence to support their use, nor that of alcohol (Gee, 2006, Berenstein and Ortiz, 2005).

In some instances it will be not be possible to improve appetite and food intake, for example when a person is acutely ill, and oral nutritional supplements will be needed (Nieuwenhuizen et al., 2010). In this case supplements need to be used while the patient is being treated and until appetite returns.

Now do time out 7.

7. Time out. Care plan.

Write a care plan that can be used to identify and treat patients in your clinical setting with poor appetite. Consider which other members of staff could help with the plan and also the role of family members in caring for the individual.

Conclusion

We have seen that there several reasons why an older person may have an impaired appetite and these can be related to the physical and psychological changes that accompany ageing. Poor appetite is important because it increases risk of nutritional deficiencies and weight loss, with weight loss being particularly difficult to reverse. These are both associated with worse health outcomes for patients and also an increased risk of dying. The nurse is well placed to identify those patients with poor appetite, identify and treat any underlying cause and use various strategies to help older people to improve their appetite and the adequacy of their diet. These include enhancing the flavour of food with herbs, spices and sauces, by improving mealtime ambience, serving smaller portions of enriched foods, finding ways to help the person have company at mealtimes, serving ‘beverage’ meals and serving foods the patient is known to like at the times they usually eat. Encouraging an increase in levels of physical activity when appropriate might also help. Finally oral nutritional supplements may need to be used to support patients who are acutely ill and have very poor appetite.

Now do time out 8.

8. Time out. Practice area.

Consider the environment in which you care for your patients. Are there any improvements that could be made to benefit the appetite of all patients? How could you work with your colleagues to implement those changes? What barriers to change do you envisage?

9. Time out. Further reading.

If you have enjoyed this article you might like to read more about appetite research in the journal ‘Appetite’. http://www.journals.elsevier.com/appetite/

10. Time out. Practice profile.

Now that you have completed the article you might like to write a practice profile. Guidelines to help you are…

Aims and intended learning outcomes.

The aim of this article is to review current knowledge and understanding of appetite in older people. After reading this article you should be able to:

-

■

Discuss the normal control of appetite

-

■

Summarise the potential implications of poor appetite in older people

-

■

Identify what physiological, social and psychological factors can cause appetite impairment

-

■

Describe how to measure appetite

-

■

Discuss what options are available to manage appetite impairment in older people

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

ALP, SMR, AAS & HCR have no conflict of interest to declare

Peer review

This article has been subject to double-blind review and has been checked using antiplagiarism software

References

- AGARWAL E, MILLER M, YAXLEY A, et al. Malnutrition in the elderly: A narrative review. Maturitas. 2013;76:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGE UK. Later Life in the United Kingdom. August edition 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ALVARENGA L, KIYAN L, BITENCOURT B, et al. The impact of retitrement on the quality of life of the elderly. Journal of the Nursing School of the University of Sao Paulo. 2009;43(4):794–800. [Google Scholar]

- BERENSTEIN E, ORTIZ Z. Megestrol acetate for the treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2005:CD004310. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004310.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTHOUD H-R. Metabolic and hedonic drives in the neural control of appetite: who is the boss? Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2011;21:888–896. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLUNDELL J, CAUDWELL P, GIBBONS C, et al. Role of resting metabolic rate and energy expenditure in hunger and appetite control: a new formulation. Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2012;5:608–613. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOSLEY B, WEINER D, RUDY T, et al. Is chronic nonmalignant pain associated with decreased appetite in older adults? Preliminary evidence. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:247–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNIE S. Why are elderly individuals at risk of nutritional deficiency? International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2006;12:110–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAMPBELL W, CRIM M, YOUNG V, et al. Increased energy requirements and changes in body composition with resistance training in older adults. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;60:167–175. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOLLY M, WILSON A. Feeding aids. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:378–379. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6748.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE BOER A, TER HORST G, LORIST M. Physiological and psychosocial age-related changes associated with reduced food intake in older persons. Ageing Research Reviews. 2012;12:316–328. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI F, FANTIN F, RESIDORI L, et al. Effect of age on the dynamics of acylated ghrelin in fasting conditions and in response to a meal. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1369–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOUGLASS R, HECKMAN G. Drug-related taste disturbance: A contributing factor in geriatric syndromes. Canadian Family Physician. 2010;56:1142–1147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGEL J, SIEWERDT F, JACKSON R, et al. Hardiness, depression, and emotional well-being and their association with appetite in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59:482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLAGHER P, O’MAHONY D. Constipation in old age. Best Practice and Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2009;23:875–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEE C. Does alcohol stimulate appetite and energy intake? British Journal of Community Nursing. 2006;11:298–302. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2006.11.7.21445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDBERG S, WHITTAMORE K, HARWOOD R, et al. The prevalence of mental health problems among older adults admitted as an emergency to a general hospital. Age and Ageing. 2012;41:80–86. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODPASTER B, PARK S, HARRIS T, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2006;61:1059–64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA A, EPSTEIN J, SROUSSI H. Hyposalivation in elderly patients. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2006;72:841–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLICK M. Vitamin D deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IKEDA M, BROWN J, HOLLAND A, et al. Changes in appetite, food preference, and eating habits in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2002;73:371–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.4.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANDI F, LATTANZIO F, DELL’AQUILA G, et al. Prevalence and potentially reversible factors associated with anorexia among older nursing home residents: Results from the ULISSE Project. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANGHANS W. Signals generating anorexia during acute illness. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2007;66:321–330. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE J, KRITCHEVSKY S, TYLAVSKY F, et al. Factors associated with impaired appetite in well-functioning community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 2006;26:27–43. doi: 10.1300/J052v26n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEIDY H, APOLZAN J, MATTES R, et al. Food Form and Portion Size Affect Postprandial Appetite Sensations and Hormonal Responses in Healthy, Nonobese, Older Adults. Obesity. 2010;18:293–299. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MALAFARINA V, URIZ-OTANO F, GIL-GUERRERO L, et al. The anorexia of ageing: physiopathology, prevalence, associated comorbidity and mortality. A systematic review. Maturitas. 2013;74:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATTES R, HOLLIS J, HAYES D, et al. Appetite: measurement and manipulation misgivings. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:S87–S97. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCDOUGALL F, MATTHEWS F, KVAAL K, et al. Prevalence and symptomatology of depression in older people living in institutions in England and Wales. Age and Ageing. 2007;36:562–568. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORLEY J, SILVER A. Anorexia in the elderly. Neurobiology of Aging. 1988;9:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUDGE A, ROSS L, YOUNG A, et al. Helping understand nutritional gaps in the elderly (HUNGER): a prospective study of patient factors associated with inadequate nutritional intake in older medical inpatients. Clinical Nutrition. 2011;30:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR HEALTH AND CARE EXCELLENCE [last accessed: December 12 2014];Behaviour change: Individual approaches. 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph49/resources/guidance-behaviour-change-individual-approaches-pdf.

- NETZ Y, WU M-J, BECKER B, et al. Physical activity and psychological well-being in advanced age: a meta-analysis of intervention studies. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:272–284. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIEUWENHUIZEN W, WEENEN H, RIGBY P, et al. Older adults and patients in need of nutritional support: review of current treatment options and factors influencing nutritional intake. Clinical Nutrition. 2010;29:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKER B, CHAPMAN I. Food intake and ageing-the role of the gut. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2004;125:859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATEL K, GURALNIK J, et al. Prevalence and impact of pain among older adults in the United States: Findings from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study. PAIN®. 2013;154:2649–2657. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAYETTE H, GRAY-DONALD K, CYR R, et al. Predictors of dietary intake in a functionally dependent elderly population in the community. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85:677–83. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.5.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QATO D, ALEXANDER G, CONTI R, et al. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300:2867–2878. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RNIB [last acessed: December 5 2014];Key Information and Statistics. 2014 [Online]. Available: http://www.rnib.org.uk/knowledge-and-research-hub/key-information-and-statistics.

- ROBERTS S, FUSS P, HEYMAN M, et al. Control of food intake in older men. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;272:1601–1606. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520200057036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBISON J, PILGRIM A, ROOD G, et al. Can trained volunteers make a difference at mealtimes for older people in hospital? A qualitative study of the views and experience of nurses, patients, relatives and volunteers in the Southampton Mealtime Assistance Study. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2014 doi: 10.1111/opn.12064. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSSITER F, SHINTON C, DUFF-WALKER K, et al. Does Coloured Crockery Influence Food Consumption in Elderly Patients in an Acute Setting? Age and Ageing. 2014;43:ii1–ii2. [Google Scholar]

- SCHIFFMAN S. Taste and smell losses in normal aging and disease. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:1357–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIP J, PILLEMER S, BAUM B. Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLEMDAL K, SANDVIK L, WILLUMSEN T, et al. The impact of oral health on taste ability in acutely hospitalized elderly. Public Library of Science ONE. 2012;7:e36557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR A, CABLE N, FAULKNER G, et al. Physical activity and older adults: a review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2004;22:703–725. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001712421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIKBY K, FAGERSKIOLD A. The willingness to eat. An investigation of appetite among elderly people. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2004;18:120–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON M, THOMAS D, RUBENSTEIN L, et al. Appetite assessment: simple appetite questionnaire predicts weight loss in community-dwelling adults and nursing home residents. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;82:1074–1081. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]