Abstract

PURPOSE: Non-surgical treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 (CIN2/3) are needed as surgical treatments have been shown to double preterm delivery rate. The goal of this study was to demonstrate safety of a human papillomavirus (HPV) therapeutic vaccine called PepCan, which consists of four current good-manufacturing production-grade peptides covering the HPV type 16 E6 protein and Candida skin test reagent as a novel adjuvant.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: The study was a single-arm, single-institution, dose-escalation phase I clinical trial, and the patients (n = 24) were women with biopsy-proven CIN2/3. Four injections were administered intradermally every 3 weeks in limbs. Loop electrical excision procedure (LEEP) was performed 12 weeks after the last injection for treatment and histological analysis. Six subjects each were enrolled (50, 100, 250, and 500 μg per peptide).

RESULTS: The most common adverse events (AEs) were injection site reactions, and none of the patients experienced dose-limiting toxicities. The best histological response was seen at the 50 μg dose level with a regression rate of 83% (n = 6), and the overall rate was 52% (n = 23). Vaccine-induced immune responses to E6 were detected in 65% of recipients (significantly in 43%). Systemic T-helper type 1 (Th1) cells were significantly increased after four vaccinations (P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: This study demonstrated that PepCan is safe. A significantly increased systemic level of Th1 cells suggests that Candida, which induces interleukin-12 (IL-12) in vitro, may have a Th1 promoting effect. A phase II clinical trial to assess the full effect of this vaccine is warranted.

Keywords: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, clinical trial, human papillomavirus, therapeutic vaccine, T cells

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse event

- CIN 2/3

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3

- ELISPOT

enzyme-linked immunospot

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- IL-12

interleukin 12

- LEEP

loop electrical excision procedure

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- Th1

T-helper type 1

- Th2

T-helper type 2

- Treg

regulatory T cell

Introduction

CIN2/3 is a precursor of cervical cancer which is the fourth most common cancer among women globally despite availabilities of effective screening tests and prophylactic vaccines. The annual global incidence of cervical cancer is 528,000 cases and the mortality is 266,000 cases.1 It is almost always caused by HPV). HPV causes not only cervical cancer, but also anal, oropharyngeal, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers; it is estimated to be responsible for 5.2% of cancer cases in the world.2,3

Standard surgical treatments of CIN2/3 such as LEEP are effective but result in doubling of preterm delivery rate from 4.4% to 8.9%.4,5 Therefore, the new treatment guidelines published in 2013 recommend 1–2 years of close observation in women, with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2, who are less than 25 years in age or who plan to have children at any age. For cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3, treatment is recommended but observation is an accepted option.5 Non-surgical alternatives which would leave the cervix anatomically intact are needed but not currently available. When approved, an HPV therapeutic vaccine is likely to become the first-line therapy for treating CIN2/3 in young women. Furthermore, an HPV therapeutic vaccine, which requires only injections, could benefit women in developing regions where surgical expertise to perform excisional procedures may not be available.

HPV transformation of squamous epithelium to a malignant phenotype is mediated by two early gene products, E6 and E7,6 and their expression is necessary for HPV type 16 transformation of human cells.7,8 T-cell responses to HPV type 16 E6 protein have been associated with favorable clinical outcomes such as viral clearance9 and regression of cervical lesions.10,11 The E6 protein is an especially attractive target for immunotherapy since it is a viral protein, and attacking self-protein (i.e., autoimmunity) is not of concern.

Traditionally, recall antigens, which typically include a panel of Candida, mumps, and Trichophyton, were used as controls to indicate intact cellular immunity when patients were being tested for Tuberculosis by placement of purified protein derivative (PPD) intradermally T-cell-mediated inflammation would become evident in 24–48 h.12 A number of studies have demonstrated that recall antigen injections can also be used to treat common warts (a condition also caused by HPV), and several studies have shown that treating warts with recall antigens is effective not only for injected warts but also distant untreated warts.13-16 This suggests that T cells may have a role in wart regression. In a recently completed phase I investigational new drug study (NCT00569231) in which the largest wart was treated with Candida, complete resolution of the treated warts was reported in 82% (9 of 11) of patients.16 These immune-enhancing effects of Candida prompted the use of Candida as a vaccine adjuvant for the current trial. Although promising results of clinical trials evaluating DNA-based,17 peptide-based,18 and recombinant protein-based19 HPV therapeutic vaccines have been reported in recent years, none has attained regulatory approval thus far. Here, for the first time in any vaccine, we incorporated Candida as a novel vaccine adjuvant. Safety, efficacy, and immune responses of PepCan evaluated in a phase I clinical trial (NCT01653249) are described.

Results

Safety

Patient characteristics and AEs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 respectively. None of the vaccine recipients experienced any dose-limiting toxicity, and the most frequent AEs were immediate (seen with all injections) and delayed (Fig. 1A) injection site reactions. More grade 2 immediate and delayed injection site reactions were recorded at the higher doses [odds ratio of 33.0 (2.9, 374.3), P < 0.0001 for the immediate reaction and odds ratio of 4.5 (0.9, 23.8), P = 0.07 for the delayed reaction]. No patients discontinued due to AEs.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics, HPV types, T-cell response, and histological diagnoses at exit

| Dose | No | Age | Race | HPV types at entry* | CD3 T-cell responses in E6 detected after vaccinationˆ | Histology |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Exit | ||||||

| 50 μg | 1 | 36 | Caucasian | 16, 52, 84 | None | CIN2 | CIN2,3 |

| 2 | 49 | Caucasian | 45, 84 | 46–70 | CIN2 | CIN3# | |

| 3 | 28 | Caucasian | 66, 84 | 16–40; 46–70 | CIN2,3 | CIN0 | |

| 4 | 42 | African American | 45 | 1–25; 31–55; 46–70; 61–85; 76–100; 91–115; 106–130; 121–145 | CIN2 | CIN1 | |

| 5 | 31 | African American | 52, 53, 61 | 16–40, 76–100; 91–115 | CIN3 | CIN0 | |

| 6 | 41 | Caucasian | 16, 31, 58 | 1–25; 91–115; 136–158 | CIN3 | CIN0 | |

| 100 μg | 7 | 28 | African American | 26, 33, 51,55, 58, 81 | 31–55; 106–130; 121–145; 136–158 | CIN2 | CIN0 |

| 8 | 22 | African American | 45, 56 | None | CIN2 | CIN0 | |

| 9 | 34 | African American | 16 | 121–145; 136–158 | CIN3 | CIN2,3 | |

| 10 | 31 | African American | 35, 72, 83 | 16–40; 121–145; 136–158 | CIN3 | CIN2,3 | |

| 11 | 28 | African American | 16 | 1–25; 16–40; 31–55; 46–70; 61–85; 76–100; 91–115; 121–145; 136–158 | CIN2 | CIN2 | |

| 12 | 32 | Mixed | 16 | None | CIN3 | CIN0 | |

| 250 μg | 13 | 29 | African American | 39, 73, IS39 | 106–130 | CIN2 | CIN2,3 |

| 14 | 31 | African American | 58 | None | CIN3 | CIN2# | |

| 15 | 32 | African American | 35 | 1–25 | CIN3 | CIN3 | |

| 16 | 25 | Caucasian | 16 | 16–40; 31–55; 46–70; 76–100; 91–115; 136–158 | CIN3 | CIN3 | |

| 17 | 22 | African American | 35, 59, 66, 81, CP6108 | 1–25; 16–40; 46–70; 61–85; 76–100; 106–130; 121–145; 136–158 | CIN2 | CIN1 | |

| 18 | 23 | Caucasian | 45, 52, 62,82 | 1–25; 31–55; 46–70; 61–85; 76–100; 91–115 | CIN2,3 | CIN3 | |

| 500 μg | 19 | 29 | Caucasian | 16, 53 | 61–85; 91–115; 121–145 | CIN3 | CIN2,3 |

| 20 | 26 | Caucasian | 16, 35, 58, 66 | None | CIN3 | CIN3# | |

| 21 | 23 | African American | 58 | None | CIN2 | CIN3 | |

| 22 | 27 | Caucasian | 6,52, 66, CP6108 | None | CIN2 | CIN2 | |

| 23 | 26 | African American | 31,35 | NA | CIN2 | NA | |

| 24 | 32 | Caucasian | 16,62 | None | CIN3 | CIN0 | |

HPV types which became undetectable after vaccinations are shown in italics, and persistent HPV types are shown in bold.

CD3 T-cell response (positivity index ≥ 2.0 as long as at least 80 per 106 IFNγ-secreting CD3 cells detected) in new E6 region(s) after vaccinations.

considered to be a partial responder as the area of CIN3 measured ≤0.2mm2

NA = not applicable

CIN0 = No CIN

Table 2.

A. Summary of adverse events

| CTCAE Grade, Number of Events, (Number of Patients) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade1 | Grade2 | Grade3 | Grade4 | |||||||||||||

| Dose(μg/peptide) AdverseEvent | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 |

| Injectionsitereaction,immediate a | 23(6) | 24(6) | 18(6) | 11(6) | 1(1) | – | 6(3) | 11(6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Injectionsitereaction,delayed b | 5(4) | 4(3) | 3(3) | 4(3) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 3(1) | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Myalgia | 8(3) | 4(1) | 4(1) | 4(3) | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fatigue | 5(3) | 1(1) | 2(1) | 2(2) | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Diarrhea | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nausea | 2(2) | 5(3) | – | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vomiting | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Headache | 3(2) | 3(3) | 5(2) | 6(2) | – | – | – | 2(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pain–body | 2(2) | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | 2(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Alopecia | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Feverishc | 1(1) | 2(1) | 1(1) | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hot Flashes | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Muscle spasm | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Flu-like symptoms | 5(2)u(1) | 3(1) | 1(1)u | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Photo phobia | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fracture | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1) | u- | – | – | – |

| Bruising | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Head injury | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Facial laceration | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Allergic reaction | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Cholecystitis | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal infection | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | 2(1)u | 1(1)u | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vulval infection | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal irritation | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Epistaxis | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Agitation | – | – | 1(1) | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Vertigo | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Dizziness | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Neutropenia | 3(3)u | 2(2) | – | –2(2)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hypokalemia | 4(4) | 3(3)u(2) | 2(2) | 2(2)u(1) | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – |

| Lymphocytosis | – | – | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Thrombocytopenia | – | – | 1(1)u | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anemia | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AST increased | 1(1)u | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ALT increased | 1(1)u | 1(1)u | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| GGT increased | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Appearing < 24 h from time of vaccination; includes site pain, redness, swelling, welt, tenderness, itching, burning, and/or warmness.

Appearing ≥ 24 h from time of vaccination; includes site pain, redness, swelling, welt, tenderness, itching, burning, and/or warmness.

Feeling warm without evidence of temperature ≥38.0°C.

Unrelated adverse event; number of events, and patients presented.

Figure 1.

(A) A representative example of a delayed injection site reaction, from patient 3, which developed 5 d after the first injection at the lowest dose level. Such reactions were self-limiting and were treated with ice packs and topical steroid creams. (B) A representative photomicrograph of microparticles formed in a well containing peptide at the 250 μg dose-equivalent with Candida.

Other vaccine-related or possibly vaccine-related AEs, in order of decreasing number of occurrences, were myalgia, headache, nausea, fatigue, hypokalemia, flu-like symptoms, feeling feverish, body pain, agitation, vomiting, hot flushes, muscle spasm, photophobia, vertigo, dizziness, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (Table 2). None of these AEs were more than grade 2.

Efficacy

CIN2/3 lesions are usually asymptomatic so vaccine response was assessed by histological regression. CIN2/3 was no longer present at exit in 9 of 23 (39%) patients who completed the study (complete responders), and the CIN2/3 lesions measured ≤ 0.2 mm2 in 3 (13%) patients (partial responders, Table 1). The histological response rates by dose were 83%, 50%, 33%, and 40% (67%, 50%, 17%, and 20% complete response). None progressed to cervical squamous cell carcinoma. The regression rates were similar for CIN2 (50%) and CIN3 (54%), and in CIN2/3 associated and not associated with HPV 16 (44% vs. 57%). The mean number of cervical quadrants with visible lesions decreased significantly from 2.1 ± 1.1 (range 0 to 4) quadrants prior to vaccination to 0.8 ± 1.0 (0 to 3) quadrants after vaccination (P < 0.0001). However, 5 of the 12 subjects with no visible lesions after vaccination were histological non-responders with persistent CIN2/3. At least one HPV type present at entry became undetectable in 13 of 23 (57%) patients. By dose, the rates were 83%, 50%, 50%, and 40% with the highest undetectability at the lowest dose.

Table 2.

B. Detailed descriptions of injection site reactions

| CTCAE Grade, Number of Events, (Number of Patients) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (μg/peptide) Adverse Event |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

||||||||||||

| 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | 50 | 100 | 250 | 500 | |

| Injection site reaction, immediate | 23 (6) | 24 (6) | 18 (6) | 11 (6) | 1 (1) | – | 6 (3) | 11 (6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pain | – | – | – | – | 1 (1) | – | 6 (3) | 11 (6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Redness | 24 (6) | 23 (6) | 24 (6) | 22 (6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Swelling | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | 1 (1) | 8 (4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Welt | 7 (4) | 16 (5) | 22 (6) | 21 (6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Tenderness | – | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Itching | 13(5) | 13(5) | 11(5) | 9(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Burning | – | 1(1) | 1(1) | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Warmness | – | 1(1) | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Injections interaction, delayed | 5(4) | 4(3) | 3(3) | 4(3) | 1(1) | 1(1) | 3(1) | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pain | – | – | – | 1(1) | 1(1) | 3(1) | 5(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Redness | 5(4) | 2(2) | 5(3) | 3(3) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Swelling | 5(4) | 2(2) | 2(2) | 5(5) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Welt | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Tenderness | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Itching | 1(1) | 2(2) | 3(3) | 4(4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Burning | – | 2(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Warmness | – | – | 1(1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

Immune responses

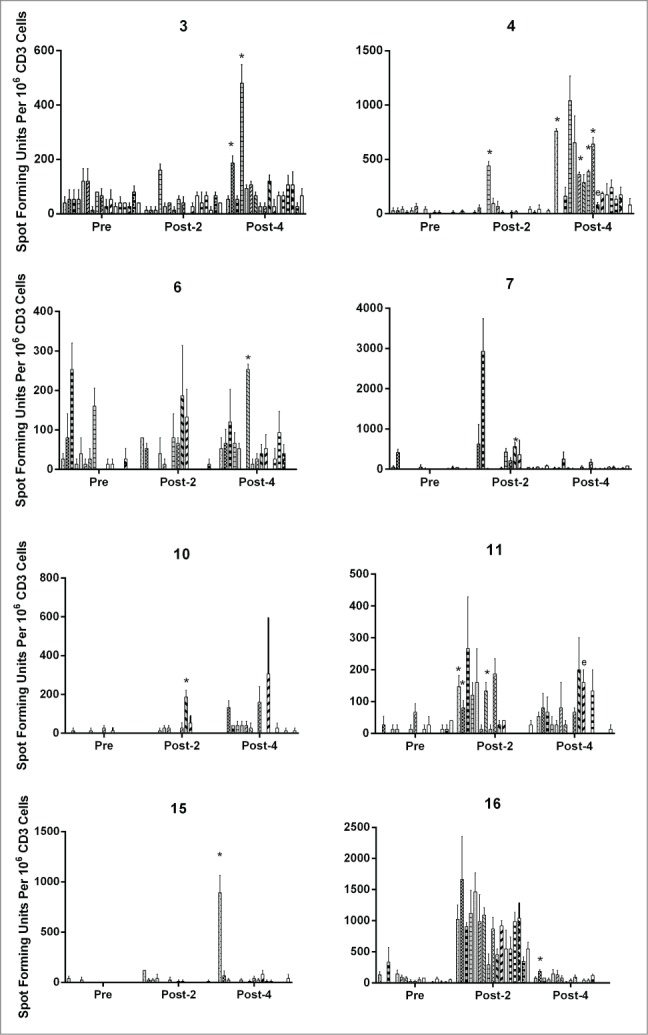

New CD3 T-cell responses to at least one region of the E6 protein were detected in 15 of 23 patients (65%, Table 1) with the increased responses after vaccination being statistically significant in 10 patients (43%, Fig. 2). The CD3 T-cell response rates to E6 by dose were 83%, 67%, 83%, and 20% with the best responses at the 50 and 250 μg doses. The percentages of statistically significant increase in E6 responses were 50%, 50%, 50%, and 20% by dose. Patients 4 and 11 demonstrated statistically significant increases in one of the regions of E7 likely representing epitope spreading. T-cell responses to HPV proteins are often detectable in sexually active women who have been exposed to HPV.9-11,20 These naturally occurring immune responses to E6, prior to vaccination, were detected in 10 patients (43%; four patients had responses to one region, one patient had responses to two regions, four patients had responses to three regions, and one patient had responses to seven regions). Three patients (13%) also had pre-vaccination responses to E7 (two patients had responses to one region, and the other patient had responses to two regions).

Figure 2.

HPV 16 E6- and E7-specific CD3 T-cell responses before vaccinations, after two vaccinations, and after four vaccinations. Results are shown for patients with statistically significant increases, and the E6 regions with significant increases (P <0.05, paired t-test) are marked by “*.”Two vaccine recipients (4 and 11) also had significant increases in one of the E7 regions likely representing epitope spreading which are marked by “e.” The bars represent standard error of means.

Figure 2.

(Continued)

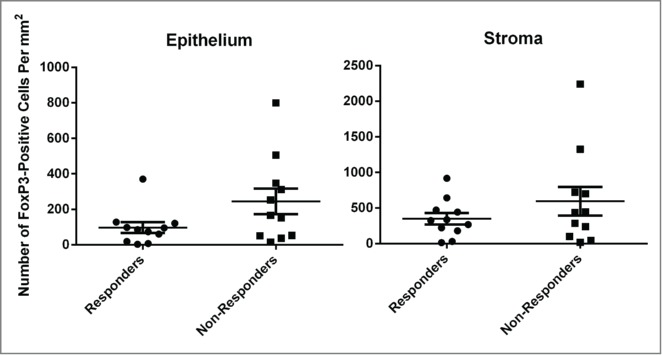

The percentages of regulatory T cells (Tregs) were not changed after vaccinations while those of Th1 cells were significantly increased (P = 0.02). The percentages of T-helper type 2 (Th2) cells increased significantly initially after two vaccinations (P = 0.03), but decreased below the baseline after four vaccinations (Fig. 3A). The differences between the responders and non-responders approached significance for Tregs at baseline (P = 0.07) and at post-two vaccinations (P = 0.08, Fig. 3B). The number of Tregs infiltrating lesional cervical epithelium and the underlying stroma was lower in histological responders compared to non-responders, and approached statistical significance for the epithelium (P = 0.08, Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

(A) Circulating immune cells before, after two, and after four vaccinations in all vaccine recipients. (B) Circulating immune cells in responders (•) and non-responders (▪). Percentages of CD4 cells positive for CD4 and Tbet are shown for Th1 cells, positive for CD4+ and GATA3 are shown for Th2 cells, and positive for CD4+, CD25, and FoxP3 for Tregs. The bars represent standard error of means.

Figure 4.

Regulatory T cells in lesional cervical epithelium and the underlying stroma. FoxP3 nuclear staining cells, in lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 1, 2, and/or3) remaining after vaccination or representative region if no lesions remaining, were counted. The FoxP3 nuclear staining cells were also counted in the underlying stroma. The bars represent stand error of means.

Medicinal product

Precipitates became visible immediately at the 250 μg peptide dose-equivalent, and at other peptide dose-equivalents at 20 min. For peptides combined with Candida (Candin®, Nielsen Biosciences, Inc., #59584-138-01) the precipitates formed at 20 min for the 500 μg peptide dose-equivalent, at 40 min for the 100 and 250 μg peptide dose-equivalents, and at 80 min for the 500 μg peptide dose-equivalent. A representative photomicrograph from peptides at 250 μg dose-equivalent with Candida is shown in Fig. 1B.

HLA

Compared to the general population in the United States, HLA frequencies for A30, A33, A66, B14, B15, B40, C03, C18, DQ03, DQ05, and DR03 were significantly increased in patients who received vaccination (n = 24, Fig. 5). In order to eliminate the effect of disparate racial distributions between these two populations, expected HLA frequencies were calculated based on the racial distribution of the patients. Significant increases were observed in the patients for A32, B14, B15, B35, B40, C03, DQ03, and DR03 (Fig. 5). When the HLA frequencies were compared between histological responders and non-responders, B44 was significantly higher in responders (4 of 24 genes) compared to non-responders (0 of 22 genes, P = 0.04).

Figure 5.

HLA gene frequencies of vaccine recipients (n = 24), the general population in the United States, and the general population based on the racial distribution of the vaccine recipients. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001 between vaccine recipients and the general population; ˆ, P < 0.05; ˆ ˆ, P < 0.01, ˆ ˆ ˆ, P < 0.001 between vaccine recipients and the general population based on vaccine recipients' racial distribution.

Discussion

The safety of this HPV therapeutic vaccine has been demonstrated as no dose-limiting toxicities were reported. The most common AEs were immediate injection site reactions which were reported with all vaccinations. In contrast, only very rare observations of immediate reactions were recorded when Candida alone was injected for treating common warts.16 Therefore, the peptides are likely to be the culprit. These AEs may be related to the peptides' property of forming microparticles when placed in a neutral pH (Fig. 1B) although they are stably soluble in its formulation which has pH of 4. These microparticles would likely enhance the immunogenicity of the vaccine as they may stimulate Langerhans cells to phagocytose them.21 The unexpected AEs were delayed injection site reactions (Fig. 1A) which were defined as occurring equal to or more than 24 h after injections. However, they appeared from 1 to 6 d afterwards and therefore not all of them could be dismissed as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.12 The timing of occurring several days afterwards raises a possibility of de novo immune responses occurring at the site.22

The best histological regression rate was recorded with the 50 μg group (83%, 67% complete response) while the overall regression rate was 52% (39% complete response). Both rates were higher than the 22% regression rate reported for a historical placebo group in another clinical trial of HPV therapeutic vaccine with a similar study design.23 These patients were given three weekly subcutaneous injections, and histological response (no CIN and CIN1) was assessed 6 months later.23 Kenter et al. reported the complete histological regression rate of 25% at 3 months and 47% at 12 months in patients with HPV 16-positive high-grade vulvar intraepithelial lesions who received another peptide-based HPV therapeutic vaccine.18 Therefore, the vaccine response is expected to increase with the extended observation period of 12 months which is being planned for the phase II clinical trial.

New HPV 16 E6-specific CD3 T-cell responses were observed in 65% of patients and more than half had statistically significant increases, attesting to the immunogenicity of PepCan. Others have reported significant correlations between HPV therapeutic vaccine-induced immune responses and clinical outcomes.18,19 Kenter et al. reported significantly higher numbers of interferon-γ-producing CD4+ T cells and stronger proliferative responses in patients with complete responses compared to those with no responses at 3 months.18 In a clinical trial of imiquimod and HPV therapeutic vaccination treating vulvar intraepithelial lesions, Daayana et al. found significantly increased lymphocyte proliferation to the HPV vaccine antigens in responders.19 We found no significant association between CD3 T-cell responses and histological regression as five responders had no new responses against E6. This may be due to a limitation of peripheral detection as HPV-specific T cells would eventually need to reach the cervix to carry out their anti-HPV activity. Naturally occurring CD3 T-cell immune responses to E6, and also to E7 in some, were detected in 43% of patients prior to vaccination in the current study. Similar percentages of CD4+ (32%) and CD8+ (41%) T-cell responses have been previously reported in unvaccinated patients from the same clinic population.10,11

Epitope spreading is a process in which antigenic epitopes distinct from and non-cross-reactive with an inducing epitope become additional targets of an ongoing immune response, and it has been associated with favorable clinical outcomes for cancer immunotherapy.24 Two vaccine recipients demonstrated significant increases in T-cell response to HPV type 16 E7 protein in addition to the E6 protein contained in the vaccine. One had persistent HPV type 16 infection, and the other one had persistent HPV type 45 infection. As there is little amino acid homology between the E7 proteins of HPV types 16 and 45, this patient may have had a latent HPV type 16 infection undetectable by the PCR method or may have had a reactivation of memory T-cell response from her past HPV type 16 infection. HPV 16 is the most common HPV type detected,25-29 and a lifetime risk of acquiring HPV 16 is estimated to be 50%.30

As an investigational adjuvant, granulocyte monocyte colony-stimulating factor has been reported to inadvertently increase Tregs resulting in less effective vaccine response.31 Therefore, we monitored levels of Tregs, which were minimally changed. Th1 cells were significantly increased, supporting the immunostimulatory effect of PepCan. Our earlier work showed that Candida has T-cell proliferative effects, and that the cytokine most frequently produced by Langerhans cells exposed to Candida was IL-12.21,32 Therefore, Candida is likely responsible for the increased levels of Th1 cells after vaccination, and may be an effective vaccine adjuvant for other therapies designed to promote T-cell activity, not only for other pathogenic antigens but also for tumor antigens in new cancer immunotherapies. However, as Candida alone was not administered in the current study, the Th1 promoting effects would need to be confirmed. Candida-only arm is being planned in the design of the phase II clinical trial. Th1 polarization of T helper cells by IL-12 has been demonstrated previously in vitro33 and in a murine model.34 However, this is the first example, to our knowledge, of Th1 promotion due to an agent that likely induces IL-12 secretion in vivo. IL-12 is also known to be a potent inducer of antitumor activity.35 Given the demonstrated safety profile of PepCan, this may be an effective alternative to systemic administration of IL-12 with which toxicities have been problematic.35 Although Treg levels were not increased after vaccination, they may have an effect on whether subjects would respond to the vaccine, as pre-vaccination Treg levels were higher in non-responders compared to responders, though not significantly. This difference persisted over time. Therefore, it is possible that some pre-treatment to decrease Treg levels prior to vaccine initiation such as administration of cyclophosphamide36,37 may improve vaccine response. Treg levels were also higher in non-responders compared to responders in the cervical lesions and the underlying stroma (though the differences were not statistically significant) possibly supporting the negative role of Treg in vaccine response.

HLA gene frequencies of B14, B15, B40, C03, DQ03, and DR03 molecules were significantly higher in our patients compared to the general population in the United States and the general population adjusted for the racial distribution of the patients. Increased risk of cervical neoplasia associated with DQ03 has been reported by others.38-40 When histological responders and non-responders were compared only B44 was significantly elevated in responders compared to non-responders. This implies that the B44 molecule may present effective epitopes of HPV 16 E6 protein. However, no such epitopes have been described to date to our knowledge.

Unexpectedly, histological regression, undetectability of at least one HPV type present at entry, and immune responses were all superior at the lowest dose compared to the highest dose, and we plan to use the lowest dose for the phase II clinical trial. As the number of subjects in each dose group was small (n = 6), this study was not powered to show significant differences. As no patient with percent Treg equal to greater than 0.8% prior to vaccination responded, it is possible that the higher pre-vaccination Treg levels at higher doses may have influenced the outcome. The median percentages of Tregs were 0.5, 0.4, 0.7 and 0.9 by dose respectively. Nevertheless, we have shown that PepCan is safe and well tolerated, and a phase II clinical trial in which the observation period is extended to 12 months for maximal response is warranted.

Patients and Methods

Patients

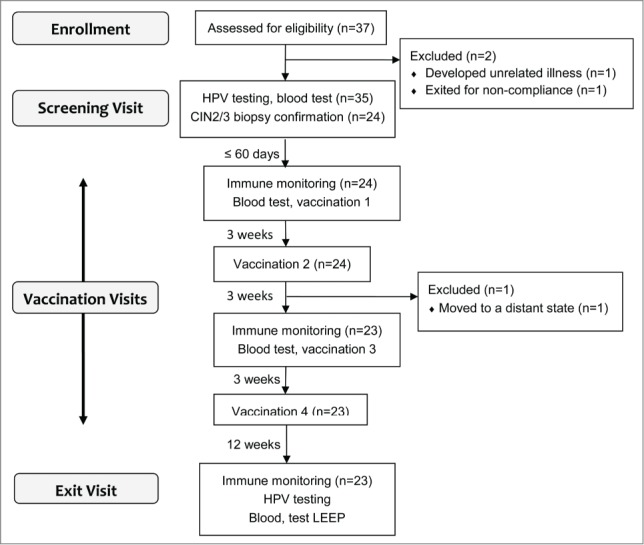

This clinical trial was a phase I single-arm, single-site, dose escalation study (Fig. 6). Patients (n = 37) were enrolled between September 2012 and March 2014, and those with biopsy-proven CIN2/3 (n = 24) were eligible for vaccination (Table 1, Fig. 6). At the screening visit, the cervix was visualized under a colposcope after applying acetic acid, biopsies were obtained, Thin-Prep (Hologic, #70097-0001) was collected for HPV-DNA testing (Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test, Roche Molecular Diagnostics, #04472209190 and #03378012190), and routine laboratory testing was performed (complete blood count, sodium, potassium, chloride, carbon dioxide, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin). Patients who already were diagnosed with biopsy-proven CIN2/3 were also eligible as long as the first vaccine injection could be given within 60 d, and other inclusion criteria were met (ages 18 to 50 years old, blood pressure ≤200/120 mm Hg, heart rate 50 to 120 beats per minute, respiration ≤25 breaths per minute, temperature ≤ 100.4°F, white count ≥ 3 × 109/L, hemoglobin ≥8 g/dL, and platelet count ≥50 × 109/L). Being positive for HPV 16 was not required due to possible cross-protection10,11,41,42 and de novo immune stimulation.14,16 Exclusion criteria included a history of disease or treatment causing immunosuppression, pregnancy, breast feeding, allergy to Candida, a history of severe asthma, current use of β-blocker, and a history of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Urine pregnancy test was performed prior to each injection, and blood was drawn for routine laboratory testing and immunological assessments immediately prior to the first and third injections. The vaccine was administered intradermally in any limb. Twelve weeks after the last injection, blood was drawn, ThinPrep sample was collected, and LEEP was performed. The study gynecologists described the presence of visible lesions and their locations. Digital photographs were taken as additional documentation. Pre-vaccination biopsies from the screening visits and post-vaccination LEEP biopsies were read by the staff pathologists at the study institution. In addition, the study pathologist (C.M.Q.) reviewed all slides of all LEEP samples. The highest grade of pathology found in any lesion was used to determine eligibility to be vaccinated and to assess histological response. Safety and tolerability were assessed from the time informed consent was obtained until the day LEEP was performed using version 4.1 of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Dose-limiting toxicities were defined as vaccine-related allergic and autoimmune AEs greater than grade 1 and any other AEs greater than grade 2. Efficacy was based on histological grading of the LEEP samples. A patient with no dysplasia or CIN 1 was considered to be a complete responder, and a patient with CIN2/3 measuring ≤ 0.2 mm2 (ScanScope® CS and ImageScope™ Software, Aperio) was considered to be a partial responder. When responders and non-responders were compared, complete and partial responders were combined. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and a written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Figure 6.

A summary of study design and number of patients evaluated. Vaccination was started within 60 d of biopsy date, and four injections were given 3 weeks apart. Each patient received the same dose of the peptides, and six subjects were recruited in each dose group.

Vaccine composition

The vaccine consisted of four current good-manufacturing production-grade synthetic peptides covering the HPV 16 E6 protein with the following sequences:

E6 1–45 (Ac- MHQKRTAMFQDPQERPRKLPQLCTELQTTIHDIILECVYCKQQLL-NH2),

E6 46–80 (Ac-RREVYDFAFRDLCIVYRDGNPYAVCDKCLKFYSKI-NH2),

E6 81–115 (Ac-SEYRHYCYSLYGTTLEQQYNKPLCDLLIRCINCQK-NH2), and

E6 116–158 (Ac-PLCPEEKQRHLDKKQRFHNIRGRWTGRCMSCCRSSRTRRETQL-NH2).21 The two regions (amino acids 46–70 and 91–115) previously shown to be most immunogenic in terms of CD8 T-cell responses were preserved.11

As formation of precipitates were previously noticed when the vaccine peptides were placed in tissue culture media,21 an experiment was designed to evaluate and document this phenomenon. Reconstituted peptides alone or reconstituted peptides with Candida, at the same proportions as in the four doses being tested (but one-sixth in total volume), were combined with RPMI1640 media (Mediatech, Inc., #10-040-CV) with 10% fetal calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals, #S11150H) in a 24-well plate. A total volume for each condition was 1 mL. The mixtures were incubated at 37˚C with 5% carbon dioxide. Visual inspection to detect precipitate formation was performed every 20 min for the first 80 min, and every 40 min for the following 160 min. Photomicrographs were taken at 24 h using AxioCam Mrc5 attached to AxioImager Z1 with Axio Vision software (Carl Zeiss AG) in the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Digital Microscopy Laboratory (Fig. 1B).

Prior to injecting patients, lyophilized peptides were reconstituted with sterile water and were mixed with 300 μl of Candida albicans skin test reagent (Candin) in a syringe. The amount of peptide per injection was 50, 100, 250, or 500 μg per peptide, and the total injection volume was 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, or 1.2 ml respectively.

Immunological assessments

PERIPHERAL HPV 16-SPECIFIC T-CELL RESPONSES (also see the Supplementary Appendix)

T-cell lines were established from three blood draws from each patient as described previously with minor modifications.10,11,43 In short, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized whole blood using a Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation method, separated into CD14+ monocytes and CD14-depleted PBMCs, and cryopreserved. Autologous dendritic cells were established by growing monocytes in the presence of granulocyte monocyte-colony stimulating factor (50 ng/mL, Sanofi-Aventis, #420039) and recombinant interleukin-4 (100 U/mL, R&D Systems, # 204-IL-050) for 7 d, and were matured by 48-h culture in wells containing irradiated mouse L-cells expressing CD40 ligands. CD3 T cells were magnetically selected (Pan T Cell Isolation Kit II, Miltenyi Biotec, #130-096-535) from CD14-depleted PBMCs. HPV 16 E6- and E7-specific CD3 T-cell lines were established by in vitro stimulation of CD3 cells for 7 d with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with E6-glutathione S-transferase and E6 expressing recombinant vaccinia virus or E7-glutathione S-transferase and E7 expressing recombinant vaccinia virus.10,11,43-45 In vitro stimulation was repeated for an additional 7 d.

ELISPOT assays were performed in triplicate using overlapping peptides covering the E6 and E7 proteins of HPV 16, as described.43 MultiScreen-MAHA plates (Millipore, #MAHAS4510) were coated with mouse anti-human interferon-γ monoclonal primary antibody (5 μg/mL, 1-D1K, Mabtech, #3420-3-1000). The coated plates were washed and blocked. After incubating at 37˚C for 1 h, 2.5 × 104 CD3+ cells per well were added, along with pools of peptides (10 μM each) in triplicate. Negative control wells contained medium only, and positive control wells contained phytohaemagglutinin at 10 μg/mL(Remel, #R30852801). Following a 24 h incubation, the plates were washed and a secondary antibody was added (1 μg/mL of biotin-conjugated anti-interferonγ monoclonal antibody; 7-B6-1, Mabtech, #3420-6-250). After a 2 h incubation and washing, avidin-bound biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, #PK-6100) was added. After 1 h of incubation, the plates were washed, and stable diaminobenzene (50 μL, Life Technologies, #750118) was added. After developing the reaction for 5 min, the plates were washed with deionized water. Spot-forming units were counted by an automated ELISPOT analyzer (AID ELISPOT Classic Reader; Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH). An HPV-specific T-lymphocyte response was considered to be positive if spot-forming units in peptide containing wells were at least two times higher than in the corresponding negative-control wells (i.e., positivity index of ≥2.0),46 and if at least 80 spot-forming units per 106 CD3 T cells were present in peptide containing wells. If any region was found to be positive after two or four vaccinations, and the positivity index was higher than that at the baseline, the number of peptide-specific spot forming units for each well was calculated by subtracting the number of background spot-forming units from the negative control wells containing media only. Paired t-test was used to assess the significance of differences after two or four vaccinations compared to the baseline.

Peripheral immune cells

Thawed PBMCs were stained with relevant isotype controls and combinations of monoclonal antibodies to analyze Th1, Th2, and Tregs: fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-human CD4 (clone RPA-T4, eBioscience, #45-0048-41), phycoerythrin-labeled anti-human/mouse T-bet (clone 4B10, eBioscience, #12-5825-82), PerCP-Cy5.5-labeled anti-human CD25 (clone BC96, eBioscience, #45-0259-42), allophycocyanin-labeled anti-human Foxp3 (clone PCH101, eBioscience, #17-4776-42), and phycoerythrin -Cy7 labeled anti-human/mouse GATA3 (clone L50-823, Becton Dickinson Biosciences, #560405). Cells were first stained with antibodies for surface markers CD3, CD4, and CD25. Staining for intracellular T-bet, GATA3, and Foxp3 was performed using the Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience, #00-5523-00) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with FACS Fortessa using FACS Diva software (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) in the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Microbiology and Immunology Flow Cytometry Core Laboratory. Ten thousand events were acquired in the lymphocyte gate. CD4 cells were expressed as a percentage of lymphocytes, Th1 cells were expressed as a percentage of CD4 cells positive for Tbet, Th2 cells were expressed as a percentage of CD4 cells positive for GATA3, and Tregs were expressed as a percentage of CD4 cells positive for CD25 and Foxp3.10

Cervical regulatory T cells

Nuclear localization of FoxP3 was utilized to quantitate Tregs using a digital pathology system.47,48 Slides of LEEP samples were pre-treated with a target retrieval solution (Dako Corporation, #S2369), peroxidase block (Dako Corporation, #S2003), and serum-free protein block (Dako Corporation, #X0909) prior to performing immunohistochemistry with primary goat anti-human polyclonal antibody against FoxP3 (R&D Systems, #AF3240) at 1:400 dilution. Following treatment with biotinylated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody at 1:400 dilution (Vector Laboratories, #BA-5000), the slides were developed using Vectastain Elite ABC (Vector Laboratories, #PK-6100) and diaminobenzidine (Dako Corporation, #K3468). Hemaoxylin (Richard-Allan Scientific, #2-7231) was used as a counterstain. Using a digital pathology system (ScanScope® CS and ImageScope™ software, Aperio), lesions in the epithelium (minimum ≥0.2mm2) and areas in the underling stroma (minimum ≥ 0.2 mm2) were marked by a study pathologist. Representative normal regions were selected if no lesions remained. Cells with positive nuclear staining were counted using the software.

Hla typing

Low-resolution typing for HLA class I A, B, and C and class II DRB1, DQB1, and DPB1 was performed with MicroSSP Generic DNA Typing Trays (One Lambda, #SSP1L and #SSPDRQP1), using DNA extracted from PBMCs. Data were analyzed with HLA Fusion (One Lambda).

Statistical Analysis

A generalized estimate equation analyses were performed to compare the frequencies of grade 2 immediate and delayed injection site reactions between the higher doses (250 and 500 μg) and the lower doses (50 and 100 μg), while accounting for the correlation among injections given to the same individual. A sign test was performed to compare the numbers of cervical quadrants with visible lesions prior to and after four vaccinations. A paired t-test was used to determine significance of increased CD3 T-cell responses as determined by rising positivity index for each region after two or four vaccinations, and to compare percentages of Th1, Th2, and Tregs after two or four vaccinations from the baseline. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare percentages of Th1, Th2, or Tregs between responders and non-responders prior to vaccination, after two vaccinations or after four vaccinations. Chi-square test was used to compare frequencies of each HLA molecule between the patients and the general population in the United States or between the patients and the corrected population frequencies based on racial distributions of the patients.49 Fisher's exact text was used to compare HLA frequencies between responders and non-responders. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01CA143130, UL1TR000039, and P20GM103625).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Mayumi Nakagawa is one of the inventors named in patents and patent applications describing PepCan. Other authors have no potential conflict of interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all clinic staff, especially Rochelle Pace, for assisting and coordinating with study visits at the gynecology clinics, Jennifer James for staining slides with Foxp3 antibody, Jennifer Roberts and her staff for pharmacological preparation of the vaccine, Patricia Gminski for administrative execution of the study, and Carole Hamon, Larry Parker, Melisa Clark, and Jennifer Hixon for assistance with investigational new drug submission and maintenance. In addition, the authors would like to thank the patients for participating in this clinical trial.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Cancer IAfRo GLOBOCAN 2012 CANCER FACT SHEET. Cedex, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK. Beyond cervical cancer: burden of other HPV-related cancers among men and women. J Adolesc Health 2010; 46:S20-6; PMID:20307840; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tota JE, Chevarie-Davis M, Richardson LA, Devries M, Franco EL. Epidemiology and burden of HPV infection and related diseases: implications for prevention strategies. Prev Med 2011; 53 Suppl 1:S12-21; PMID:21962466; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruinsma FJ, Quinn MA. The risk of preterm birth following treatment for precancerous changes in the cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2011; 118:1031-41; PMID:21449928; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wentzensen N, Lawson HW. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121:829-46; PMID:23635684; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A. Cervix. Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 2004:1072-9 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pirisi L, Yasumoto S, Feller M, Doniger J, DiPaolo J. Transformation of human fibroblasts and keratinocytes with human papillomavirus type 16 DNA. J Virol l987; 61:1061-6; PMID: 2434663.2460337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlegel R, Phelps WC, Zhang YL, Barbosa M. Quantitative keratinocyte assay detects two biological activities of human papillomavirus DNA and identifies viral types associated with cervical carcinoma. Embo J 1988; 7:3181-7; PMID:2460337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakagawa M, Stites DP, Patel S, Farhat S, Scott M, Hills NK, Palefsky JM, Moscicki AB. Persistence of human papillomavirus type 16 infection is associated with lack of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to the E6 antigens. J Infect Dis 2000; 182:595-8; PMID:10915094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/315706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KH, Greenfield WW, Cannon MJ, Coleman HN, Spencer HJ, Nakagawa M. CD4+ T-cell response against human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein is associated with a favorable clinical trend. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012; 61:63-70; PMID:21842207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00262-011-1092-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa M, Gupta SK, Coleman HN, Sellers MA, Banken JA, Greenfield WW. A favorable clinical trend is associated with CD8 T-cell immune responses to the human papillomavirus type 16 e6 antigens in women being studied for abnormal pap smear results. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2010; 14:124-9; PMID:20354421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181c6f01e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esch RE, Buckley CE 3rd. A novel Candida albicans skin test antigen: efficacy and safety in man. J Biol Stand 1988; 16:33-43; PMID:3280571; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-1157(88)90027-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifton MM, Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Kincannon J, Horn TD. Immunotherapy for recalcitrant warts in children using intralesional mumps or Candida antigens. Pediatr Dermatol 2003; 20:268-71; PMID:12787281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20318.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn TD, Johnson SM, Helm RM, Roberson PK. Intralesional immunotherapy of warts with mumps, Candida, and Trichophyton skin test antigens: a single-blinded, randomized, and controlled trial. Arch Dermatol 2005; 141:589-94; PMID:15897380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archderm.141.5.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Horn TD. Intralesional injection of mumps or Candida skin test antigens: a novel immunotherapy for warts. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137:451-5; PMID:11295925 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim KH, Horn TD, Pharis J, Kincannon J, Jones R, O'Bryan K, Myers J, Nakagawa M. Phase 1 clinical trial of intralesional injection of Candida antigen for the treatment of warts. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146:1431-3; PMID:21173332; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bagarazzi ML, Yan J, Morrow MP, Shen X, Parker RL, Lee JC, Giffear M, Pankhong P, Khan AS, Broderick KE et al.. Immunotherapy against HPV16/18 generates potent TH1 and cytotoxic cellular immune responses. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:155ra38; PMID: 23052295; http://dx.doi.org/19890126 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, Essahsah F, Fathers LM, Offringa R, Drijfhout JW et al.. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1838-47; PMID:19890126; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daayana S, Elkord E, Winters U, Pawlita M, Roden R, Stern PL, Kitchener HC. Phase II trial of imiquimod and HPV therapeutic vaccination in patients with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Cancer 2010; 102:1129-36; PMID:20234368; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakagawa M, Stites DP, Farhat S, Sisler JR, Moss B, Kong F, Moscicki AB, Palefsky JM. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to E6 and E7 proteins of human papillomavirus type 16: relationship to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Infect Dis 1997; 175:927-31; PMID:9086151; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/513992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Coleman HN, Nagarajan U, Spencer HJ, Nakagawa M. Candida skin test reagent as a novel adjuvant for a human papillomavirus peptide-based therapeutic vaccine. Vaccine 2013; 31:5806-13; PMID:24135577; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbas AK, Lichtman AH, Pillai S. Cellular and Molecular Immunology. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieminen P, Harper DM, Einstein MH, Garcia F, Donders G, Huh W, Wright TC, Stoler M, Ferenczy A, Rutman O et al.. Efficacy and safety of RO5217990 treatment in patients with high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3). 28th International Papillomavirus Conference. Puerto Rico, 2012; Clinical Science Abstract Book; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ribas A, Timmerman JM, Butterfield LH, Economou JS. Determinant spreading and tumor responses after peptide-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol 2003; 24:58-61; PMID:12547500; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)00029-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010; 202:1789-99; PMID:21067372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/657321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clifford GM, Gallus S, Herrero R, Munoz N, Snijders PJ, Vaccarella S, Anh PT, Ferreccio C, Hieu NT, Matos E et al.. Worldwide distribution of human papillomavirus types in cytologically normal women in the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV prevalence surveys: a pooled analysis. Lancet 2005; 366:991-8; PMID:16168781; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, Munoz N, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2003; 88:63-73; PMID:12556961; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:518-27; PMID:12571259; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa021641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J, Franceschi S, Winer R, Clifford GM. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer 2007; 121:621-32; PMID:17405118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.22527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Hende M, Redeker A, Kwappenberg KM, Franken KL, Drijfhout JW, Oostendorp J, Valentijn AR, Fathers LM, Welters MJ, Melief CJ et al.. Evaluation of immunological cross-reactivity between clade A9 high-risk human papillomavirus types on the basis of E6-Specific CD4+ memory T cell responses. J Infect Dis 2010; 202:1200-11; PMID:20822453; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/656367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Olson WC, Smolkin ME, Ross MI, Haas NB, Grosh WW, Boisvert ME, Kirkwood JM, Chianese-Bullock KA. Effect of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on circulating CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses to a multipeptide melanoma vaccine: outcome of a multicenter randomized trial. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:7036-44; PMID:19903780; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagawa M, Coleman HN, Wang X, Daniels J, Sikes J, Nagarajan UM. IL-12 secretion by Langerhans cells stimulated with Candida skin test reagent is mediated by dectin-1 in some healthy individuals. Cytokine 2014; 65:202-9; PMID:24301038; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manetti R, Parronchi P, Giudizi MG, Piccinni MP, Maggi E, Trinchieri G, Romagnani S. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (interleukin 12 ; IL-12) induces T helper type 1 (Th1)-specific immune responses and inhibits the development of IL-4-producing Th cells. J Exp Med 1993; 177:1199--204; PMID:8096238; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.177.4.1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh CS, Macatonia SE, Tripp CS, Wolf SF, O'Garra A, Murphy KM. Development of TH1 CD4+ T cells through IL-12 produced by Listeria-induced macrophages. Science 1993; 260:547-9; PMID:8097338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.8097338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tugues S, Burkhard SH, Ohs I, Vrohlings M, Nussbaum K, Vom Berg J, Kulig P, Becher B. New insights into IL-12-mediated tumor suppression. Cell Death Differ 2014; PMID:25190142; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038.cdd.2014-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berd D, Maguire HC Jr, Mastrangelo MJ. Potentiation of human cell-mediated and humoral immunity by low-dose cyclophosphamide. Cancer Res 1984; 44:5439-43; PMID:6488195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emadi A, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA. Cyclophosphamide and cancer: golden anniversary. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2009; 6:638-47; PMID:19786984; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hildesheim A, Schiffman M, Scott DR, Marti D, Kissner T, Sherman ME, Glass AG, Manos MM, Lorincz AT, Kurman RJ et al.. Human leukocyte antigen class I/II alleles and development of human papillomavirus-related cervical neoplasia: results from a case-control study conducted in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1998; 7:1035-41; PMID:9829713 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Smith AG, Hansen JA, Nisperos BB, Li S, Zhao LP, Daling JR, Schwartz SM, Galloway DA. Comprehensive analysis of HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, and HLA-DQB1 loci and squamous cell cervical cancer risk. Cancer Res 2008; 68:3532-9; PMID:18451182; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang SS, Wheeler CM, Hildesheim A, Schiffman M, Herrero R, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Alfaro M, Hutchinson ML, Morales J et al.. Human leukocyte antigen class I and II alleles and risk of cervical neoplasia: results from a population-based study in Costa Rica. J Infect Dis 2001; 184:1310-4; PMID:11679920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/324209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KH, Dishongh R, Santin AD, Cannon MJ, Bellone S, Nakagawa M. Recognition of a cervical cancer derived tumor cell line by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 52-61-specific CD8 T cell clone. Cancer Immun 2006; 6:9; PMID:16808432 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Greenfield WW, Coleman HN, James LE, Nakagawa M. Use of interferon-gamma enzyme-linked immunospot assay to characterize novel T-cell epitopes of human papillomavirus. J Vis Exp 2012; PMID: 22434036; http://dx.doi.org/16085919 10.3791/3657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Moscicki AB. Patterns of CD8 T-cell epitopes within the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV 16) E6 protein among young women whose HPV 16 infection has become undetectable. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2005; 12:1003-5; PMID:16085919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Gillam TM, Moscicki AB. HLA class I binding promiscuity of the CD8 T-cell epitopes of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein. J Virol 2007; 81:1412-23; PMID:17108051; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.01768-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Moscicki AB, Tsang L, Brockman A, Nakagawa M. Memory T cells specific for novel human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E6 epitopes in women whose HPV16 infection has become undetectable. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2008; 15:937-45; PMID:18448624; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/CVI.00404-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaul R, Dong T, Plummer FA, Kimani J, Rostron T, Kiama P, Njagi E, Irungu E, Farah B, Oyugi J et al.. CD8(+) lymphocytes respond to different HIV epitopes in seronegative and infected subjects. J Clin Invest 2001; 107:1303-10; PMID:11375420; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi A, Weinberg V, Darragh T, Smith-McCune K. Evolving immunosuppressive microenvironment during human cervical carcinogenesis. Mucosal Immunol 2008; 1:412-20; PMID:19079205; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/mi.2008.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Magg T, Mannert J, Ellwart JW, Schmid I, Albert MH. Subcellular localization of FOXP3 in human regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 2012; 42:1627-38; PMID:22678915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.201141838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.OrganProcurementandTransplantationNetwork US-Department of Health & Human Services. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.