Abstract

Rationale: The epidemiology of post–acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis remains largely unknown.

Objectives: To examine the rate of post–acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis and to examine risk factors and outcomes for hospital readmissions after sepsis.

Methods: In an observational cohort study conducted in an academic health care system (2010–2012), we compared post–acute care use at discharge and hospital readmission after 3,620 sepsis hospitalizations with 108,958 nonsepsis hospitalizations. We used three validated, claims-based approaches to identify sepsis and severe sepsis.

Measurements and Main Results: Post–acute care use at discharge was more likely after sepsis, driven by skilled care facility placement (35.4% after sepsis vs. 15.8%; P < 0.001), with the highest rate observed after severe sepsis. Readmission rates at 7, 30, and 90 days were higher postsepsis (P < 0.001). Compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations (15.6% readmitted within 30 d), the increased readmission risk was present regardless of sepsis severity (27.3% after sepsis and 26.0–26.2% after severe sepsis). After controlling for presepsis characteristics, the readmission risk was found to be 1.51 times greater (95% CI, 1.38–1.66) than nonsepsis hospitalizations. Readmissions after sepsis were more likely to result in death or transition to hospice care (6.1% vs. 13.3% after sepsis; P < 0.001). Independent risk factors associated with 30-day readmissions after sepsis hospitalizations included age, malignancy diagnosis, hospitalizations in the year prior to the index hospitalization, nonelective index admission type, one or more procedures during the index hospitalization, and low hemoglobin and high red cell distribution width at discharge.

Conclusions: Post–acute care use and hospital readmissions were common after sepsis. The increased readmission risk after sepsis was observed regardless of sepsis severity and was associated with adverse readmission outcomes.

Keywords: critical care, emergency department use, hospital readmission, infection, sepsis

Sepsis is a growing public health problem (1). Advances in care and increased recognition have led to improvements in in-hospital mortality rates in the 2–3 million annual U.S. cases (2–6). Coupled with an increasing incidence (2, 3), the population of sepsis survivors is expanding rapidly (7). Survivors often incur morbidity that could undermine their future health, including sepsis-induced inflammation, immunosuppression, functional disability, and cognitive impairment (8–10).

Improving care transitions and reducing 30-day hospital readmissions have become a national priority in the United States (11–13). Post–acute care use, including services and placement at discharge, is costly and increasing (12). When combined with 30-day readmissions, the costs of post–acute care may rival the cost of the index hospitalization, highlighting the incentive to integrate acute and post–acute care for high-risk conditions (12, 13).

Recent data suggest that health care utilization increases after sepsis (14–17). As these studies were largely restricted to the elderly (15, 16) or the most severely ill (14, 16, 17), and because all but one lacked a comparison group (14, 15, 17), essential questions remain unanswered. In our present multicenter study, we set out to examine four questions. First, compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations, what is the rate of post–acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis? Second, is the increased readmission risk after sepsis confined to certain patients (e.g., the most severely ill)? Third, compared with readmissions after nonsepsis hospitalizations, are outcomes during readmissions worse after sepsis hospitalizations? Fourth, what risk factors are associated with 30-day readmission after sepsis?

Methods

Study Design

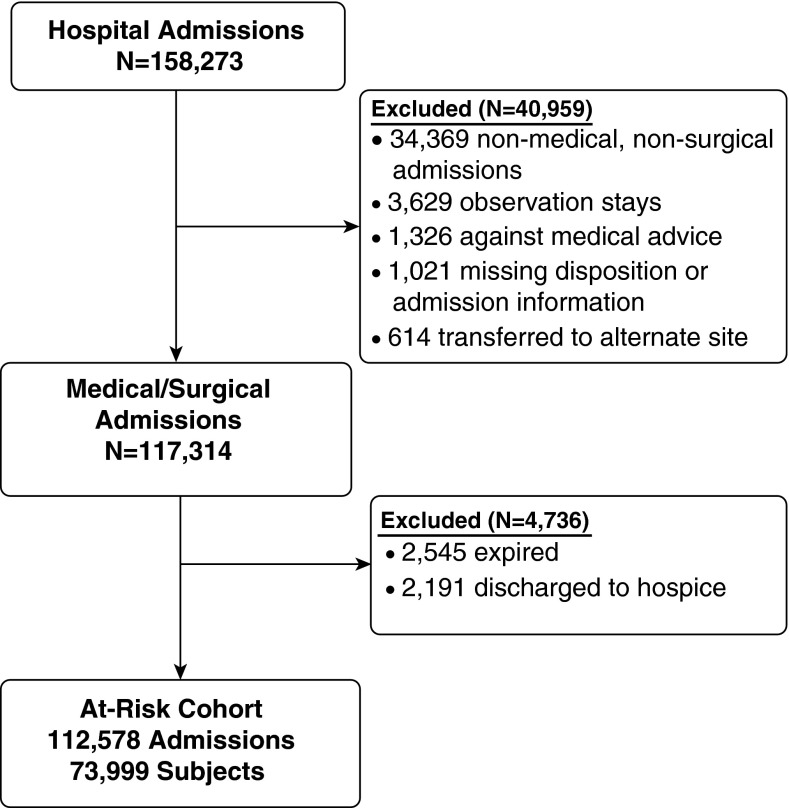

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study within the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS), an integrated academic health care system. UPHS consists of three acute care hospitals in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. We included adult medical and surgical admissions to UPHS hospitals between July 2010 and July 2012. We focused on patients discharged alive and not transitioned to hospice care to identify a population at risk for hospital readmission (Figure 1). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study (no. 818852) with an informed consent exemption.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the enrollment process.

Data Collection

To examine post–acute care use and readmission rates after an acute care hospitalization, we merged administrative and electronic health record data. We collected sociodemographics, comorbid conditions, hospitalizations in the prior year, and hospitalization details. We previously reviewed medical records to ensure the quality of the administrative data using this approach (18) and reviewed a sample of cases and each variable for quality assurance for the present study.

We discriminated sepsis from nonsepsis hospitalizations using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), codes based on administrative data (18–20). Sepsis was defined using three validated approaches to capture the spectrum of disease severity (18–20). We identified cases of sepsis using the explicit ICD-9-CM–specific code method (995.91) for sepsis. We used two complementary approaches to identify severe sepsis cases. In the first one, we used the explicit ICD-9–specific codes for severe sepsis and septic shock (995.92 and 785.52, respectively). In the second, we used an implicit approach requiring ICD-9-CM codes for infection, including the 038 family of codes for septicemia, and end-organ dysfunction via the Angus method (18–20). Because septicemia could identify cases of sepsis or severe sepsis, we did not integrate septicemia codes into our explicit approach.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was 30-day all-cause hospital readmission to any of the three hospitals within the UPHS. Readmissions were considered outcomes and also served as index hospitalizations (13, 21, 22). Secondary outcomes included post–acute care use at discharge, 7- and 90-day readmissions, emergency department treat-and-release visits within 30 days, hospital-based acute care use within 30 days (23), and outcomes after readmission.

Statistical Analyses

First, we compared post–acute care use at discharge and readmission rates after sepsis hospitalizations with nonsepsis hospitalizations. We hypothesized that variables captured in recently validated readmission prediction scores (21, 24) would be concentrated in sepsis survivors. We also contrasted readmission rates after sepsis hospitalizations with hospitalizations associated with the high-risk conditions of acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia, all as identified by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)–recommended ICD-9-CM codes (22).

Second, we began with a logistic regression model that considered the odds of 30-day hospital readmission for the sepsis population with the odds for the nonsepsis population and used robust standard errors to account for clustering. This model—the population-averaged effect—provides an estimate of the odds of readmission after sepsis from the hospital’s perspective. Next, we used mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression models to adjust for subject-specific random effects. In the final models, we additionally controlled for center and presepsis characteristics, factors present prior to the index hospitalization that are known to be, or potentially to be, associated with readmission risk (13, 17, 21–25). We examined the following presepsis characteristics: age, sex, race, marital status, insurance status, comorbid conditions (using the Charlson Comorbidity Index score (25) and a history of malignancy specifically), and number of admissions over the prior year. Last, we forced each of these variables into the model. Missing data were negligible for the variables (<1%), save for race (2.8%). Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors. We adjusted for potential covariates and maintained those that altered the OR estimate by more than 10% (26). To complement these analyses, we examined the 30-day readmission risk after stratifying by age and burden of comorbid conditions.

To examine the influence of illness severity, we contrasted readmission rates after a nonsepsis hospitalization to the explicit code(s) for sepsis, severe sepsis, and the Angus method. To permit a direct comparison, we recategorized 503 sepsis hospitalizations as severe sepsis hospitalizations when severe sepsis was identified using the Angus method. In addition, we examined the 30-day readmission risk after stratifying by admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) during the index admission and, separately, by performing mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression models stratified by length of stay (LOS), categorized into quartiles based on the observed distributions.

Third, we compared outcomes during readmissions after index sepsis hospitalizations with nonsepsis hospitalizations. Last, we used mixed-effects multivariable logistic regression models (with random intercepts for patients) to examine risk factors associated with 30-day readmission after sepsis hospitalizations. In addition to variables included in readmission prediction scores (13, 17, 21–24), we examined four hospitalization factors: acute dialysis, acute neurologic dysfunction, the use of mechanical ventilation, and presence of shock. We identified these conditions using validated claims-based approaches and included them in models based on the hypothesis that these factors, which reflect illness severity and have been related to long-term cognitive and/or physical impairment after critical illness (10, 27–29), would be associated with readmission. In addition to discharge hemoglobin and sodium values (21), we examined discharge creatinine and red cell distribution width (RDW) based on biologic plausibility and the relationship between RDW and postdischarge mortality after critical illness (30, 31). We included variables associated with readmission at a significance level of P < 0.20 in multivariable models (26). We adjusted for year of admission, center, and prior hospitalizations (19, 24). We used Stata/IC 13 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX) for statistical analyses and defined significance as an α less than 0.05.

Results

Enrollment

There were 117,314 medical and surgical admissions to the UPHS that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Sepsis was present during the hospitalization in 5,162 (4.4%) of the 117,314 admissions and in 1,138 (44.7%) of 2,545 admissions that resulted in in-hospital death. Compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations, in-hospital death or a transition to hospice care was more likely in sepsis hospitalizations and highest among those with severe sepsis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomes after index admission and readmission rates among at-risk survivors, stratified by sepsis category

| Mortality and Hospice at Discharge in 117,314 Medical and Surgical Admissions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsepsis (n = 112,152) | Sepsis* (n = 5,162) |

|||

| ICD-9-CM–Specific Sepsis Code Assignment (995.91) (n = 2,032) | ICD-9-CM–Specific Severe Sepsis Code Assignments (995.92, 785.52) (n = 3,115) | Severe Sepsis Combining End-Organ Dysfunction and Infection Code Assignments (n = 3,726) | ||

| In-hospital mortality | 1,407 (1.2) | 133 (6.6) | 1,005 (32.3) | 1,095 (29.4) |

| Discharged to hospice | 1,787 (1.6) | 128 (6.3) | 277 (8.9) | 340 (9.1) |

| Post–Acute Care Use at Discharge† and Hospital Readmission† in 112,578 Medical and Surgical Admissions At Risk for Readmission | ||||

| Nonsepsis (n = 108,958) | Sepsis (n = 3,620) |

|||

| ICD-9-CM–Specific Sepsis Code Assignment (995.91) (n = 1,771) | ICD-9-CM–Specific Severe Sepsis Code Assignments (995.92, 785.52) (n = 1,833) | Severe Sepsis Combining End-Organ Dysfunction and Infection Code Assignments (n = 2,291) | ||

| Post–acute care use | ||||

| Home health services | 34,208 (31.4) | 498 (28.1) | 551 (30.1) | 672 (29.3) |

| Acute rehabilitation | 4,680 (4.3) | 64 (3.6) | 159 (8.7) | 196 (8.6) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 11,602 (10.6) | 321 (18.1) | 488 (26.6) | 586 (25.6) |

| Long-term acute care | 408 (0.4) | 42 (2.4) | 158 (8.6) | 186 (8.1) |

| Hospital readmission | ||||

| 7-d readmission | 5,657 (5.2) | 152 (8.6) | 184 (10.0) | 228 (10.0) |

| 30-d readmission | 16,950 (15.6) | 483 (27.3) | 477 (26.0) | 600 (26.2) |

Definition of abbreviation: ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Sepsis accounted for 4.4% of admissions, yet it accounted for 44.7% of the 2,545 in-hospital deaths (1,138 of 2,545). Sepsis categories presented were not mutually exclusive. For example, 503 admissions at risk for readmission received the ICD-9-CM–specific code for sepsis and were identified using the combined end-organ dysfunction and infection approach, and 1,772 admissions at risk for readmission received the ICD-9-CM–specific code for severe sepsis and were identified using the combined end-organ dysfunction and infection approach.

Post–acute care use includes home health services and skilled care facility placement (e.g., acute rehabilitation, long-term acute care hospital, skilled nursing facility).

After excluding 2,545 (2.2%) admissions resulting in in-hospital death and 2,191 (1.9%) transitioned to hospice care, there were 112,578 discharges among 73,999 unique patients at risk of hospital readmission. Of these 112,578 discharged patients, 3,620 (3.2%) were sepsis survivors.

Baseline Characteristics

In general, patients who had sepsis during the index admission were older, more likely to be male, single, and Medicare beneficiaries and more likely to have a greater number of comorbid conditions and a malignancy diagnosis (Table 2). As hypothesized, factors previously identified as associated with readmissions were more common in sepsis survivors, including nonelective admission, LOS, number of procedures, low discharge hemoglobin and sodium, and hospitalizations in the year prior to the index admission.

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics between sepsis and nonsepsis hospitalizations at risk of readmission

| Nonsepsis Hospitalization (n = 108,958) | Sepsis Hospitalization (n = 3,620) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factors at presentation | |||

| Age, yr | 58 ± 17 | 59 ± 17 | 0.005 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 55,073 (50.6) | 2,000 (55.2) | <0.001 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 61,530 (58.0) | 1,961 (56.2) | 0.02 |

| Black | 39,521 (37.3) | 1,327 (38.1) | |

| Asian | 2,009 (1.9) | 85 (2.4) | |

| Other | 2,931 (2.8) | 113 (3.2) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 49,695 (45.6) | 1,645 (45.4) | |

| Single/never married | 37,863 (34.8) | 1,324 (36.6) | 0.02 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 21,400 (19.6) | 651 (18.0) | |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |||

| Medicare | 46,868 (43.1) | 1,705 (47.2) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 11,533 (10.6) | 326 (9.0) | |

| Private | 49,175 (45.2) | 1,568 (43.4) | |

| None | 1,165 (1.1) | 16 (0.44) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2 (0–4) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 |

| Any malignancy diagnosis* | 17,061 (15.7) | 1,198 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Number of hospitalizations in prior year | |||

| 0 | 67,506 (62.0) | 1,572 (43.4) | |

| 1–5 | 38,136 (35.0) | 1,852 (51.2) | <0.001 |

| >5 | 3,316 (3.0) | 196 (5.4) | |

| Index admission type: nonelective | 71,128 (65.3) | 3,064 (84.6) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay, d | 3.6 (2.1–6.2) | 12.8 (6.1–24.4) | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 19,887 (18.2) | 1,908 (52.7) | <0.001 |

| Number of procedures | 1 (0–3) | 3 (1–7) | <0.001 |

| Number of medications at discharge | 8 (0–13) | 14 (9–20) | <0.001 |

| Discharge hemoglobin, g/dl | 10.9 (9.5–12.4) | 9.5 (8.7–10.5) | <0.001 |

| Discharge red cell distribution width, % | 14.7 (13.6–16.5) | 16.5 (14.9–18.5) | <0.001 |

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations or median and interquartile ranges, as determined by their distribution.

According to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, malignancy codes per Deyo-Charlson (25).

Post–Acute Care Use at Discharge and Hospital Readmission after Sepsis

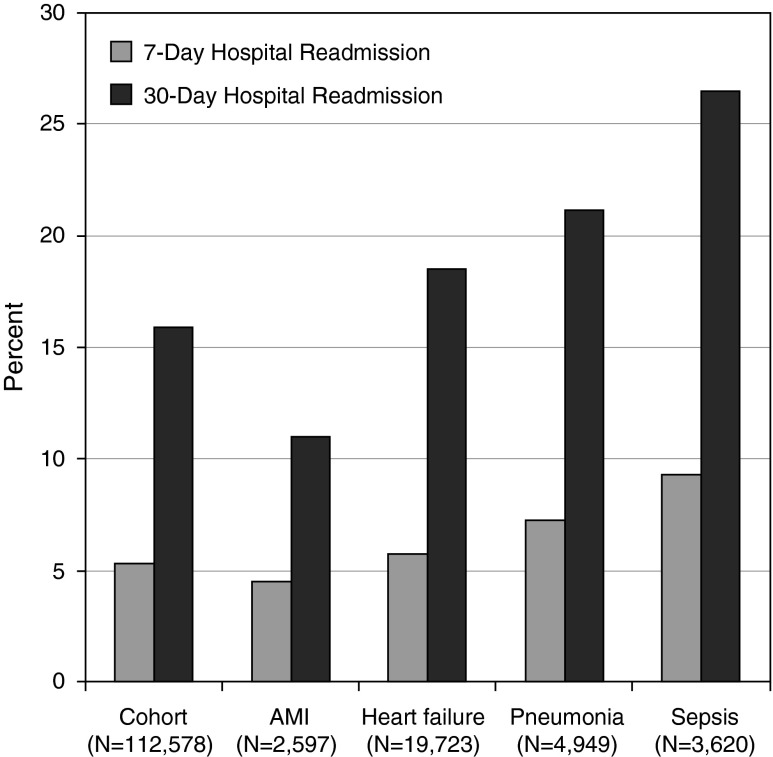

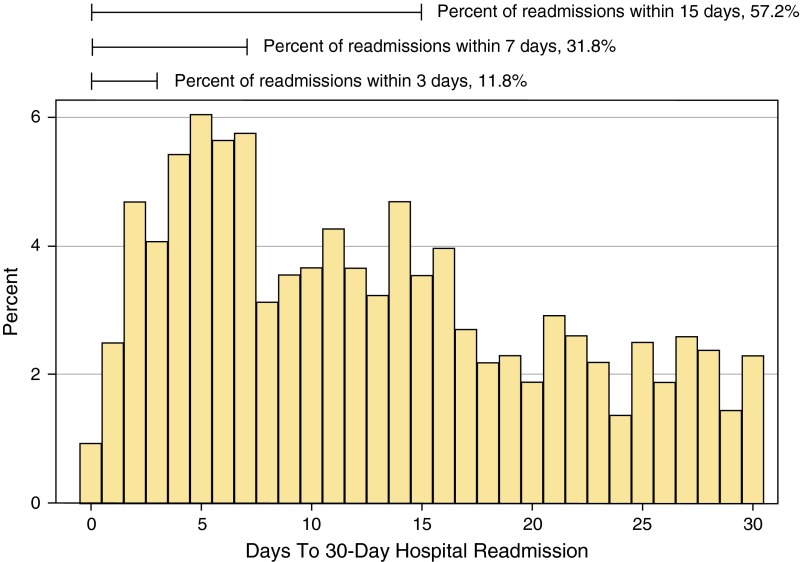

Compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations, post–acute care use at discharge was more likely after sepsis, driven by placement in a skilled care facility (Table 3). Post–acute care use was highest after severe sepsis (Table 1). Compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations, the readmission rate at 7, 30, and 90 days was significantly higher after sepsis (P < 0.001, Table 3). Readmission rates after sepsis rivaled the rates seen at UPHS following known CMS high-risk conditions (Figure 2). The majority of 30-day readmissions postsepsis occurred within 15 days of discharge, although the risk was sustained throughout the postdischarge period (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of post–acute care use at discharge and hospital-based acute care use within 30 days of hospitalization, according to sepsis status during index admission

| Outcomes, n (%) | Nonsepsis Hospitalization (n = 108,958) | Sepsis Hospitalization (n = 3,620) |

|---|---|---|

| Post–acute care use at discharge* | ||

| Home with home services | 34,208 (31.4) | 1,048 (28.9) |

| Acute rehabilitation | 4,680 (4.3) | 228 (6.3) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 11,602 (10.6) | 812 (22.4) |

| Long-term acute care hospital | 408 (0.4) | 199 (5.5) |

| Hospital readmissions | ||

| 7-d readmission† | 5,657 (5.2) | 336 (9.3) |

| 30-d readmission† | 16,950 (15.6) | 959 (26.5) |

| 90-d readmission† | 27,968 (25.7) | 1,533 (42.4) |

| ED visits (treat and release) | ||

| 30-d ED visitठ| 4,967 (4.6) | 139 (3.8) |

| Hospital-based acute care postdischarge | ||

| 30-d ED visit or readmission* | 21,917 (20.1) | 1,098 (30.3) |

| Post–acute care use within 30 d†║ | 62,406 (57.3) | 2,689 (74.3) |

Definition of abbreviation: ED = emergency department.

Categorical variables are reported as count and percentage.

Post–acute care use at discharge includes home health services and skilled care facility placement.

P < 0.001 for each comparison.

P = 0.04.

Of 15,414 ED encounters within 30 days of a nonsepsis index admission, 10,447 (67.8%) resulted in readmission; of 720 ED encounters within 30 days of a sepsis index admission, 581 (80.7%) resulted in readmission.

Post–acute care use within 30 days includes post–acute care use at discharge and hospital-based acute care postdischarge.

Figure 2.

Hospital readmission rates for overall cohort, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, pneumonia, and sepsis.

Figure 3.

Timing of 30-day hospital readmission after a sepsis hospitalization.

Readmission Risk after Sepsis

In the population-averaged effect model, the odds of readmission for sepsis hospitalizations were 1.96 times greater (95% CI 1.81–2.12) than nonsepsis hospitalizations (Table 4). After adjusting for subject-specific random effects, the odds of readmission remained 1.70 times greater. After additionally controlling for presepsis characteristics and center-level effects, the odds of readmission were further attenuated but remained 1.51 times greater. Finally, after forcing each presepsis characteristic and center into the model, the odds of readmission remained 1.36 times greater.

Table 4.

Sepsis as an independent risk factor for 30-day hospital readmission

| Model | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Sepsis, population-averaged effect | 1.96 (1.81–2.12) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis, subject-specific effect | 1.70 (1.55–1.87) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis, subject-specific effect, adjusted for presepsis characteristics and center* | 1.51 (1.38–1.66) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis, subject-specific effect, after forcing each presepsis characteristic and center into the model | 1.36 (1.24–1.48) | <0.001 |

Mixed-effects multivariable models adjusted for comorbidity of malignancy. The OR (odds ratio) was not significantly altered (<10%) by adjustment for number of hospitalizations in the prior year after accounting for subject-specific random effects, nor did age, sex, race, marital status, insurance status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, or center alter the OR significantly. CI = confidence interval.

We found that the increased readmission rate at 7 and 30 days compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations was largely similar, regardless of whether the hospitalization was coded as sepsis or severe sepsis (Table 1). After recategorizing 503 sepsis cases as severe sepsis when identified as such by the Angus method, the 7- and 30-day readmission rates after sepsis were similar at 8.0% (101 of 1,268) and 27.0% (342 of 1,268), respectively. Readmissions after severe sepsis occurred earlier (median 11 days after discharge, IQR: 5–18; compared with 13 days after sepsis, IQR: 6–21; P = 0.004). In addition, compared with nonsepsis hospitalizations, the increased 30-day readmission risk after sepsis appeared to be present regardless of age, comorbid conditions, or ICU admission status (see Figures E1–E3 in the online supplement). Last, in mixed-effects multivariable models stratified by LOS, the odds of readmission, in general, remained significantly greater (LOS <6 d (n = 80,130): OR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.54–2.31; P < 0.001; LOS 6 to <12 d (n = 21,630): OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.26–1.84; P < 0.001; LOS 12 to <18 d (n = 5,682): OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.96–1.59; P = 0.09; LOS ≥18 d (n = 5,136): OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.16–1.60; P < 0.001).

Outcomes Associated with Readmissions

In comparison with readmissions after nonsepsis hospitalizations, readmissions after sepsis hospitalizations were more likely to require an ICU admission (16.6% (2,812 of 16,950) vs. 28.9% (277 of 959); P < 0.001), less likely to result in being discharged to home, and more likely to result in death or transition to hospice care (Table 5).

Table 5.

Discharge disposition following hospital readmission, by sepsis status at index admission

| Discharge disposition, n (%)*† | Nonsepsis, (n = 16,761) | Sepsis, (n = 948) |

|---|---|---|

| Home | 7,023 (41.9) | 303 (32.0) |

| Home health services | 5,769 (34.4) | 269 (28.4) |

| Skilled care facility‡ | 2,698 (16.1) | 241 (25.4) |

| Other‡ | 251 (1.5) | 9 (1.0) |

| Hospice | 584 (3.5) | 63 (6.6) |

| Died | 436 (2.6) | 63 (6.6) |

P < 0.001 for comparison across groups.

Disposition was missing in 200 readmissions (1.1%).

Skilled care facility includes home with home health services, acute rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility, and long-term acute care hospital. Other includes patients who left against medical advice and those discharged to an acute care hospital or other facility (e.g., psychiatric facility).

Risk Factors Associated with 30-Day Readmission after Sepsis

Clinical risk factors associated with 30-day hospital readmissions are presented in Table 6. Independent risk factors associated with 30-day readmissions after sepsis hospitalizations included age, malignancy diagnosis, hospitalizations in the year prior to the index hospitalization, nonelective index admission type, one or more procedures during the index hospitalization, and low hemoglobin and high RDW at discharge (Table 7).

Table 6.

Clinical risk factors associated with 30-day hospital readmission after sepsis hospitalization

| No Readmission (n = 2,661) | Readmissions (n = 959) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factors at presentation | |

|||

| Age, yr | 60 ± 16 | 58 ± 16 | 0.004 |

|

| Male sex, n (%) | 1,471 (55.3) | 529 (55.2) | 0.95 |

|

| Race, n (%) | |

|||

| White | 1,415 (55.4) | 546 (58.7) | 0.23 |

|

| Black | 988 (38.6) | 339 (36.4) | ||

| Asian | 68 (2.7) | 17 (1.8) | ||

| Other | 85 (3.3) | 28 (3.0) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | |

|||

| Married | 1,205 (45.3) | 440 (45.9) | |

|

| Single/never married | 971 (36.5) | 353 (36.8) | 0.82 |

|

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 485 (18.2) | 166 (17.3) | |

|

| Insurance status, n (%) | |

|||

| Medicare | 1,295 (48.7) | 410 (42.9) | 0.005 |

|

| Medicaid | 240 (9.0) | 86 (9.0) | ||

| Private | 1,110 (41.8) | 458 (47.9) | ||

| None | 14 (0.8) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 2 (1–5) | 3 (2–5) | 0.004 |

|

| Any malignancy diagnosis* | 797 (30.0) | 401 (41.8) | <0.001 |

|

| Number of hospitalizations in prior year† | |

|||

| 0 | 1,256 (47.2) | 316 (32.9) | |

|

| 1–5 | 1,302 (48.9) | 550 (57.4) | <0.001 |

|

| >5 | 103 (3.9) | 93 (9.7) | |

|

| Index admission type: nonelective | 2,231 (83.8) | 833 (86.9) | 0.02 |

|

| Clinical factors during hospitalization | ||||

| Length of stay, d | 12.2 (6.0–23.2) | 13.9 (6.6–27.6) | <0.001 |

|

| Use of mechanical ventilation | 636 (23.9) | 206 (21.5) | 0.13 |

|

| Acute dialysis | 253 (9.5) | 94 (9.8) | 0.79 |

|

| Acute neurologic dysfunction | 287 (10.8) | 96 (10.0) | 0.50 |

|

| Shock | 751 (28.2) | 252 (26.3) | 0.25 |

|

| Intensive care unit admission | 1,405 (52.8) | 503 (52.4) | 0.86 |

|

| Procedures (≥1)† | 2,194 (82.4) | 856 (89.3) | <0.001 |

|

| Clinical factors at discharge |

||||

| Number of medications at discharge | 14 (8–20) | 15 (10–22) | <0.001 |

|

| Discharge hemoglobin, g/dl | 9.6 (8.8–10.6) | 9.2 (8.5–10.1) | <0.001 |

|

| Low discharge hemoglobin, ≤9.5 g/dl†‡ | 1,270 (48.0) | 574 (59.9) | <0.001 |

|

| Discharge sodium, mEq/L | 138 (136–140) | 138 (136–140) | 0.81 |

|

| Low discharge sodium, <135 mEq/L † | 371 (14.0) | 120 (12.5) | 0.25 |

|

| Discharge creatinine, mEq/L | 0.88 (0.66–1.30) | 0.86 (0.64–1.31) | 0.33 |

|

| Discharge RDW, mEq/L‡ | 16.4 (14.8–18.4) | 16.7 (15.3–19.0) | 0.002 |

|

| RDW <15.0% | 713 (27.0) | 191 (19.9) | |

|

| RDW 15.0–18.4% (25th–75th percentile) | 1,277 (48.3) | 493 (51.5) | <0.001 |

|

| RDW ≥18.5% | 654 (24.7) | 274 (28.6) | ||

Definition of abbreviation: RDW = red cell distribution width.

Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations or median and interquartile ranges, as determined by their distribution.

According to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, malignancy codes per Deyo-Charlson (25).

Categorized as described by and Donzé and colleagues (24).

Categorized based on observed distribution.

Table 7.

Risk factors independently associated with 30-day hospital readmission after sepsis hospitalizations

| Model, n = 3,620 | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, per 10-yr decrease | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 0.02 |

| Malignancy diagnosis† | 1.79 (1.47–2.19) | <0.001 |

| Shock | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) | 0.24 |

| Use of mechanical ventilation | 0.89 (0.70– .12) | 0.34 |

| Acute dialysis | 0.94 (0.71–1.26) | 0.70 |

| Acute neurologic dysfunction | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) | 0.68 |

| Number of hospitalizations in prior year | ||

| 0 | Referent | Referent |

| 1–5 | 1.56 (1.30–1.86) | <0.001 |

| >5 | 2.97 (2.09–4.22) | <0.001 |

| Index admission type: nonelective | 1.92 (1.47–2.51) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay ≥13 d | 1.16 (0.95–1.41) | 0.15 |

| Procedures (≥1) | 1.64 (1.24–2.16) | <0.001 |

| Low discharge hemoglobin, ≤9.5 g/dl | 1.48 (1.24–1.75) | <0.001 |

| Red cell distribution width at discharge | ||

| <15.0% | Referent | Referent |

| 15.0–18.4% | 1.34 (1.07–1.66) | 0.009 |

| ≥18.5% | 1.30 (1.01–1.67) | 0.04 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Models adjusted for year of admission and center.

Charlson Comorbidity Index score was not included in the models, as a malignancy diagnosis is a component of the score. When forced into the model, malignancy remained significant, whereas the Charlson Comorbidity Index score was found to be nonsignificant.

Discussion

In this multicenter observational study of medical and surgical admissions, we detailed the central role that sepsis plays across the continuum of care within an academic health care system. Consistent with a recent report by Liu and colleagues reflecting the U.S. national landscape (32), we found that sepsis contributed to 45% of in-hospital deaths. We found that, at discharge, post–acute care use was more common after sepsis and highest after severe sepsis. After discharge, sepsis survivors were significantly more likely than nonsurvivors to be rehospitalized; the 30-day readmission rates observed after sepsis rivaled rates associated with known CMS high-risk conditions (22); and the risk appeared to endure for an extended period of time. Finally, readmissions within 1 month of a sepsis hospitalization were more than twice as likely to result in death or a transition to hospice care.

We confirmed that postdischarge readmission risk is high after sepsis, in line with rates reported in recent studies focused on severe sepsis and septic shock (16, 17). In the single study in which researchers compared health care utilization after severe sepsis with subjects’ own health care use presepsis and with matched nonsepsis controls, Prescott and coworkers found a substantial increase in resource utilization, including a 30-day hospital readmission rate of 26.5% (16). However, it remained uncertain whether the increased risk was limited to the elderly or to the most severe cases. Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that readmission risk was largely independent of illness severity. Specifically, we found 30-day readmission rates were 27.0–27.3% after sepsis and 26.0–26.2% after severe sepsis, and they appeared to be independent of ICU admission status. Furthermore, several traditional measures of illness severity (e.g., use of mechanical ventilation, ICU admission) were not associated with 30-day readmission after sepsis. In light of evidence revealing that readmissions are frequently due to an infection (17), whereas functional outcomes may differ by illness severity, we found that short-term readmission risk appeared to be largely independent of illness severity and more related to whether a recent infection occurred.

We additionally found that the increased readmission risk after sepsis was not confined to the elderly or to those with the greatest burden of comorbid conditions. Rather, the relative risk appeared to be greatest in the youngest patients and those who were previously healthy, findings that are explained in part by higher readmission rates among those with a greater burden of comorbid disease after a nonsepsis hospitalization. Nevertheless, we found that controlling for a history of malignancy and presepsis health care use attenuated the relationship between sepsis and readmission, as we also found when we stratified our analyses by LOS. These findings complement recent cohort studies that revealed these to be risk factors associated with increased health care utilization after sepsis (15–17).

In our risk factor assessment, we confirmed that a malignancy diagnosis and prior hospitalizations were associated with 30-day hospital readmission (15, 17). In addition, we found that younger age, nonelective admission status, receipt of one or more procedures during the index sepsis hospitalization, and low hemoglobin and high RDW at discharge were additional factors independently associated with readmission. RDW, a measure of erythrocyte size variability, is traditionally associated with anemia, hemolysis, and nutritional deficiencies. However, RDW has also recently been posited to be associated with residual inflammation, physiologic reserve, and functional dependence after critical illness and in the elderly (30, 31, 33). As serum lactate is used as a simple and reliable biomarker to risk-stratify patients in the proximal phase of sepsis, it is plausible that RDW, for reasons that require further exploration, could serve that role at the time of hospital discharge.

Readmission reduction has emerged as a strategy for controlling health care costs and improving quality for high-risk conditions. Our findings support the recommendation that sepsis is an additional condition that warrants attention at the national level in the United States (34), based on the high frequency with which readmissions occur after sepsis and the associated morbidity and mortality. This consideration would be timely, given temporal trends in diagnostic coding (i.e., increased documentation of sepsis as the principal diagnosis for a hospitalization paired with decreased documentation of pneumonia) (35), due in part to incentives related to public reporting of 30-day risk-standardized mortality for pneumonia (36).

For now, several important questions remain unanswered across the continuum of care that warrant further investigation. First, the evidence in support of sepsis-induced immunosuppression is growing (37), and readmissions after sepsis are frequently due to an infection (38, 39). In a study of septic shock survivors that focused on the cause of readmission, Ortego and colleagues found that 46% of 30-day readmissions were infection-related, including new, unresolved, and recurrent infections (17). Investigation is required to determine whether sepsis itself and/or the care provisions required to treat the acute illness (e.g., catheter-associated infections, transfusions [40]) confer increased readmission risk that may be preventable (41).

Second, just as resources are being directed to improve care transitions for CMS high-risk conditions, multidisciplinary programs to reduce 30-day readmissions after sepsis, with a focus on coordination of care between hospital-based providers and postdischarge providers, will be required (42). Given the likelihood of a new, unresolved, or recurrent infectious process (17), a central aspect of care coordination and discharge planning is antibiotic stewardship (43, 44). The effectiveness of this strategy could potentially be augmented with scheduled clinical assessments in person or via home telemonitoring (45). In parallel, comparative effectiveness studies will be necessary to determine whether specialized sepsis care follow-up clinics are more cost-effective than a strategy that leverages a patient’s preexisting network of providers.

Third, related to the aim to improve care transitions, effective strategies will need to recognize that post–acute care facility placement is increasingly being used (46), that it appears to be extremely common after sepsis, and that rehabilitation after sepsis has the potential to improve long-term mortality (47). Whereas post–acute care facility placement was common, only 6% of patients hospitalized for sepsis were discharged to acute rehabilitation, a modestly higher rate than the 4% of nonsepsis hospitalizations. For sepsis survivors discharged with home services, the issue of whether early and intensive home health nursing services and physician follow-up improve outcomes after sepsis, strategies that appear to improve outcomes in other patient populations (48, 49), should be studied. For survivors discharged to home without services, the question of whether referral practices, which frequently fail to identify those at risk for poor outcomes postdischarge (50), could be optimized with decision support strategies to improve access and outcomes remains unanswered (51). Related to this question is whether timely access to palliative care services could be optimized for targeted subgroups, given the frequency of hospice use among survivors, is an additional direction worth pursuing.

There are several potential limitations of this study. First, although we used validated, complementary screening strategies to identify sepsis cases, the potential for misclassification bias exists. Second, without data linked to the U.S. National Death Index, we designed the study to focus on 30-day readmissions. To examine the trajectory and outcomes of sepsis survivors admitted to certain facilities (e.g., skilled care facilities), prospective, longitudinal studies are warranted. Third, we were unable to capture readmissions that remained outside the health care system; as a result, the reported readmission rates are likely an underestimate. Relatedly, because it is unclear whether the uncaptured readmissions differed by sepsis status, this question warrants direct examination. Further, without prehospitalization trajectory data and other unmeasured confounders (e.g., functional status, preexisting depression (52)), the potential for residual confounding exists. However, given evidence that incorporated prehospitalization trajectory (16), our findings support the notion that increased post–acute care resource use is due, in part, to a sepsis-related change. Also, although we examined the relationship between sepsis and hospital readmission after controlling for presepsis characteristics and, separately, in analyses stratified by LOS, we acknowledge that further formal examination including robust matching methods is warranted (53). Finally, centers that care for patients with fewer predisposing conditions (e.g., malignancy) will likely observe lower readmission rates.

In conclusion, post–acute care use, including hospital readmissions, appeared to be common after sepsis within an academic health care system. The increased readmission risk remained high after controlling for presepsis factors and was associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Strategies incorporating hospital-based and postdischarge interventions appear to be necessary to combat the increased readmission risk after sepsis.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

This study was presented in part at the American Thoracic Society International Conference, May 2014, San Diego, CA. A different 30-day readmission rate calculation, limited to index admissions at one of the three UPHS hospitals in the latter half of 2010, was used for the reference rate in a prior study in which a separate cohort of septic shock survivors was examined (17).

Footnotes

Supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Loan Repayment Program, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (M.E.M.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design: T.K.J., B.D.F., and M.E.M.; data collection: T.K.J., B.D.F., A.H., C.A.B., C.A.U., and M.E.M.; analysis and interpretation of data: T.K.J., B.D.F., D.S.S., S.D.H., A.H., C.A.B., C.A.U., M.P.K., D.F.G., and M.E.M.; drafting of the manuscript: T.K.J. and M.E.M.; critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: T.K.J., B.D.F., D.S.S., S.D.H., A.H., C.A.B., C.A.U., M.P.K., D.F.G., and M.E.M.; and responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole: M.E.M.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ, Carr BG. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Arnold RC, Claremont HA, Kline JA Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739–746. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yealy DM, Kellum JA, Huang DT, Barnato AE, Weissfeld LA, Pike F, Terndrup T, Wang HE, Hou PC, LoVecchio F, et al. ProCESS Investigators. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yende S, Angus DC. Long-term outcomes from sepsis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2007;9:382–386. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yende S, D’Angelo G, Kellum JA, Weissfeld L, Fine J, Welch RD, Kong L, Carter M, Angus DC GenIMS Investigators. Inflammatory markers at hospital discharge predict subsequent mortality after pneumonia and sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1242–1247. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1777OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unroe M, Kahn JM, Carson SS, Govert JA, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray A, Tulsky JA, et al. One-year trajectories of care and resource utilization for recipients of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:167–175. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mechanic R. Post-acute care—the next frontier for controlling Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:692–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1315607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [Published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2011;364:1582.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elixhauser A, Steiner C.Readmissions to US hospital by diagnosis, 2010. Statistical Brief #161. Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; April 2013[accessed 2015 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu V, Lei X, Prescott HC, Kipnis P, Iwashyna TJ, Escobar GJ. Hospital readmission and healthcare utilization following sepsis in community settings. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:502–507. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, Escobar GJ, Iwashyna TJ. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortego A, Gaieski DF, Fuchs BD, Jones T, Halpern SD, Small DS, Sante SC, Drumheller B, Christie JD, Mikkelsen ME. Hospital-based acute care use in survivors of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:729–737. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittaker SA, Mikkelsen ME, Gaieski DF, Koshy S, Kean C, Fuchs BD. Severe sepsis cohorts derived from claims-based strategies appear to be biased toward a more severely ill patient population. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:945–953. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827466f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwashyna TJ, Odden A, Rohde J, Bonham C, Kuhn L, Malani P, Chen L, Flanders S. Identifying patients with severe sepsis using administrative claims: patient-level validation of the Angus implementation of the international consensus conference definition of severe sepsis. Med Care. 2014;52:e39–e43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268ac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baillie CA, VanZandbergen C, Tait G, Hanish A, Leas B, French B, Hanson CW, Behta M, Umscheid CA. The readmission risk flag: using the electronic health record to automatically identify patients at risk for 30-day readmission. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:689–695. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, Bueno H, Ross JS, Horwitz LI, Barreto-Filho JA, Kim N, Bernheim SM, Suter LG, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309:355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, D’Onofrio G, Pines JM, Ross JS, Gross CP. Use of hospital-based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. JAMA. 2013;309:364–371. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donzé J, Aujesky D, Williams D, Schnipper JL. Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:632–638. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnato AE, Albert SM, Angus DC, Lave JR, Degenholtz HB. Disability among elderly survivors of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1037–1042. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0301OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guerra C, Linde-Zwirble WT, Wunsch H. Risk factors for dementia after critical illness in elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Crit Care. 2012;16:R233. doi: 10.1186/cc11901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, Brummel NE, Hughes CG, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani AK, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunziker S, Celi LA, Lee J, Howell MD. Red cell distribution width improves the simplified acute physiology score for risk prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2012;16:R89. doi: 10.1186/cc11351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purtle SW, Moromizato T, McKane CK, Gibbons FK, Christopher KB. The association of red cell distribution width at hospital discharge and out-of-hospital mortality following critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:918–929. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu V, Escobar GJ, Greene JD, Soule J, Whippy A, Angus DC, Iwashyna TJ. Hospital deaths in patients with sepsis from 2 independent cohorts. JAMA. 2014;312:90–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Gonzalo-Calvo D, de Luxán-Delgado B, Rodríguez-González S, García-Macia M, Suárez FM, Solano JJ, Rodríguez-Colunga MJ, Coto-Montes A. Interleukin 6, soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor I and red blood cell distribution width as biological markers of functional dependence in an elderly population: a translational approach. Cytokine. 2012;58:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooke CR, Iwashyna TJ. Sepsis mandates: improving inpatient care while advancing quality improvement. JAMA. 2014;312:1397–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenauer PK, Lagu T, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Rothberg MB. Association of diagnostic coding with trends in hospitalizations and mortality of patients with pneumonia, 2003–2009. JAMA. 2012;307:1405–1413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Priya A, Lindenauer PK. Variation in diagnostic coding of patients with pneumonia and its association with hospital risk-standardized mortality rates: a cross-sectional analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:380–388. doi: 10.7326/M13-1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walton AH, Muenzer JT, Rasche D, Boomer JS, Sato B, Brownstein BH, Pachot A, Brooks TL, Deych E, Shannon WD, et al. Reactivation of multiple viruses in patients with sepsis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang T, Derhovanessian A, De Cruz S, Belperio JA, Deng JC, Hoo GS. Subsequent infections in survivors of sepsis: epidemiology and outcomes. J Intensive Care Med. 2014;29:87–95. doi: 10.1177/0885066612467162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton JP, Friedman B.Trends in septicemia hospitalizations and readmissions in selected HCUP states, 2005 and 2010. Statistical Brief #161. Rockville, MD: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2013[accessed 2015 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb161.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohde JM, Dimcheff DE, Blumberg N, Saint S, Langa KM, Kuhn L, Hickner A, Rogers MA. Health care-associated infection after red blood cell transfusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311:1317–1326. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavenberg JG, Leas B, Umscheid CA, Williams K, Goldmann DR, Kripalani S. Assessing preventability in the quest to reduce hospital readmissions. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:598–603. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chastre J, Wolff M, Fagon JY, Chevret S, Thomas F, Wermert D, Clementi E, Gonzalez J, Jusserand D, Asfar P, et al. PneumA Trial Group. Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2588–2598. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keller SC, Ciuffetelli D, Bilker W, Norris A, Timko D, Rosen A, Myers JS, Hines J, Metlay J. The impact of an infectious diseases transition service on the care of outpatients on parenteral antimicrobial therapy. J Pharm Technol. 2013;29:205–214. doi: 10.1177/8755122513500922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kvedar J, Coye MJ, Everett W. Connected health: a review of technologies and strategies to improve patient care with telemedicine and telehealth. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:194–199. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke RE, Juarez-Colunga E, Levy C, Prochazka AV, Coleman EA, Ginde AA. Rise of post–acute care facilities as a discharge destination of US hospitalizations. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:295–296. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao PW, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, Tseng CM, Kuo SC, Shih YN, Chou KT, Tarng DC, Li SY, Ou SM, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1003–1011. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1170OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sochalski J, Jaarsma T, Krumholz HM, Laramee A, McMurray JJV, Naylor MD, Rich MW, Riegel B, Stewart S. What works in chronic care management: the case of heart failure. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:179–189. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303:1716–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowles KH, Ratcliffe SJ, Holmes JH, Liberatore M, Nydick R, Naylor MD. Post-acute referral decisions made by multidisciplinary experts compared to hospital clinicians and the patients’ 12-week outcomes. Med Care. 2008;46:158–166. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815b9dc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowles KH, Hanlon A, Holland D, Potashnik SL, Topaz M. Impact of discharge planning decision support on time to readmission among older adult medical patients. Prof Case Manag. 2014;19:29–38. doi: 10.1097/01.PCAMA.0000438971.79801.7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G, Langa KM, Cigolle C. Spurious inferences about long-term outcomes: the case of severe sepsis and geriatric conditions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:835–841. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1660OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25:1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]