Abstract

Rationale: Tobacco use disproportionately affects the poor, who are, in turn, least likely to receive cessation treatment from providers. Providers caring for low-income populations perform simple components of tobacco use treatment (e.g., assessing tobacco use) with reasonable frequency. However, performance of complex treatment behaviors, such as pharmacologic prescription and follow-up arrangement, remains suboptimal.

Objectives: Evaluate the influence of academic detailing (AD), a university-based, noncommercial, educational outreach intervention, on primary care physicians’ complex treatment practice behaviors within an urban care setting.

Methods: Trained academic detailers made in-person visits to targeted primary care practices, delivering verbal and written instruction emphasizing three key messages related to tobacco treatment. Physicians’ self-reported frequency of simple and complex treatment behaviors were assessed using a seven-item questionnaire, before and 2 months after AD.

Results: Between May 2011 and March 2012, baseline AD visits were made to 217 physicians, 109 (50%) of whom also received follow-up AD. Mean frequency scores for complex behaviors increased significantly, from 2.63 to 2.92, corresponding to a clinically significant 30% increase in the number of respondents who endorsed “almost always” or “always” (P < 0.001). Improvement in mean simple behavior frequency scores was also noted (3.98 vs. 4.13; P = 0.035). Sex and practice type appear to influence reported complex behavior frequency at baseline, whereas only practice type influenced improvement in complex behavior scores at follow up.

Conclusions: This study demonstrates the feasibility and potential effectiveness of a low-cost and highly disseminable intervention to improve clinician behavior in the context of treating nicotine dependence in underserved communities.

Keywords: academic training, nicotine, physician’s practice patterns, smoking cessation, tobacco use disorder

Reductions in the prevalence of smoking and its consequences have progressed heterogeneously across population subgroups (1, 2). A disproportionate number of the poor and disadvantaged continue to smoke, compared with more economically secure populations (3). In fact, Medicaid recipients smoke at nearly double the rate of the general U.S. population (36 vs. 21%, respectively), and are less likely to receive cessation treatment from their healthcare providers (4). Philadelphia has the highest rate of adult smoking among the 10 largest U.S. cities and a high proportion of Medicaid recipients who smoke, making tobacco use interventions an urgent public health priority for the region (5).

System-level strategies to improve provider engagement in tobacco dependence treatment have most certainly contributed to the decrease in smoking prevalence. The U.S. Public Health Service clinical practice guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update (6), recommends that clinicians consistently identify and document patients’ tobacco use status, and treat tobacco users employing a “5As” framework for longitudinal care (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange). Although providers’ performance of the straightforward, simple components of the framework (i.e., ask, advise, and assess) has improved over the past 10 years, performance of the more complex, second-order components of the framework (i.e., assist and arrange follow-up) remains suboptimal (7). For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, although 62.7% of outpatient visits included tobacco screening, only 20.9% of current tobacco users received counseling and 7.6% received a prescription for cessation pharmacotherapy during their visit (8). Self-reported estimates of 5A performance rates tend to be higher across all categories; however, the pattern of discrepancy between simple and complex behaviors remains comparable, with self-assessment of simple behavior rates more than double that of self-assessed complex behaviors (9).

Various methods for influencing physician behaviors have been evaluated. Academic detailing (AD) is a university-based, noncommercial educational outreach strategy, generally accepted as useful in shaping physician behavior patterns (10, 11). Unlike more traditional educational approaches, AD interactions are designed to be very brief (3–5 min) and highly personalized, and focus on correcting misunderstandings about a specific medication or condition. When performed by public health agencies, AD has been useful in addressing a variety of issues, including intimate partner violence screening, lifestyle change counseling, and medication adherence (12). Creative AD outreach campaigns have been employed within large, diverse physician populations to increase tobacco Quitline referrals (13), and to increase smoking cessation counseling and prescribing (14). However, little is known about how such AD interventions impact performance of complex tobacco treatment behaviors among primary care physicians engaged in the care of urban, economically disadvantaged communities.

Methods

The Philadelphia COPD Initiative is a public health project designed to disseminate simple resources to physicians and patients to improve the identification and treatment of tobacco dependence by primary care practitioners within Philadelphia’s low-income communities. From May 2011 through March 2012, two allied health professionals with experience in public health education disseminated high-priority messages about smoking cessation using established AD principles (10). Detailers made in-person visits to targeted practice locations, delivering both verbal and written instruction to physicians that emphasized three key practice messages: (1) reluctance to quit can be overcome by employing a structured approach; (2) effective tobacco use treatment can be accomplished within a 7-minute visit; and (3) tobacco use treatment is a reimbursable service. Visits were conducted either individually or in small groups, and lasted 3–10 minutes, based on physician availability. At the conclusion of the visit, physicians were guided toward web-based, continuing medical education (CME) training activities for initiative participants that included video-modeled behaviors, guideline summaries, key references, and a guide to solving commonly encountered clinical problems (15). In addition, detailers educated office staff on resources available through Pennsylvania’s free Quitline. Office staff received promotional materials, including waiting area pamphlets, public area signage, and preprinted reminder cards with patient-level instruction on accessing Quitline resources.

After the AD visit, each clinic location received a series of at least three reminder letters over a 2-month postvisit period. Each letter encouraged clinicians to take advantage of the initiative’s CME opportunities, and was accompanied by prepared “un-ads” designed to directly address the potential influence of focusing effect, impact, omission, and availability biases on physician behavior (Table 1) (10, 16, 17). Un-ads consist of visually arresting images, framed by common misconceptions concerning tobacco use treatment, concluding with a summary of available data controverting the bias. An example is presented in Figure 1. Detailers performed a second in-person visit 2–4 months after the first, reinforcing the key tobacco practice messages.

Table 1.

Experience-based techniques for problem solving (heuristics), potentially leading to suboptimal judgments or outcomes related to the treatment of tobacco dependence

| Heuristic | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Availability bias | Recent or memorable events hold exceptional sway in decision making. | A prior frustration with a patient, reluctant to quit despite significant tobacco-related morbidity, influences the clinician’s subsequent assessment of patients’ likelihood of quitting. |

| Focusing effect bias | Decisions are influenced more by short-term concerns than by long-term goals. | A patient with a history of active smoking and poorly controlled hypertension requires an adjustment to his medication regimen. Initiation of tobacco dependence treatment is forgone in favor of ensuring proper understanding and adherence to antihypertensive medications. |

| Impact bias | Decisions are unduly influenced by inaccurate projections of future states. | A discussion of available tobacco dependence treatments is avoided out of concern over the potential time commitment required, or because of the perceived risk of alienating the patient. |

| Omission bias | Tendency to prefer inaction in an effort to avoid harm, even when inaction may cause greater harm than action. | Treatment with tobacco dependence pharmacotherapy is avoided because of concerns for possible depressed mood side effects. |

Figure 1.

Un-ad addressing omission bias in tobacco use treatment. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CME = continuing medical education. Main image reprinted by permission from Dr. Jerry Avorn, National Resource Center for Academic Detailing, Boston, MA.

Outcome measures were assessed at the onset of both the baseline and follow-up visits, before initiating the AD intervention. Primary outcomes were physician self-reported simple and complex tobacco treatment clinical behaviors, assessed using a paper seven-item questionnaire, with responses on a five-point Likert categorical scale of frequency, ranging from “never” (1) to “always” (5). For the primary analysis, questionnaire items were categorized as representing either “simple” (included estimates of ask, assess, and advise frequency) or “complex” (included estimates of pharmacologic prescription, referral to Quitline, follow-up arrangement, and billing frequency). Secondary outcomes included physician program evaluation. Additional information on related CME outcomes was estimated from the subset of clinicians who participated in the web-based educational activity.

Analysis used Chi-square test of proportions and Wilcoxon test of paired differences. Exploratory analysis used multiple logistic regression to evaluate the impact of individual- and practice-level covariates on outcomes, including physician sex, practice location, practice type, estimated smoking prevalence in practice, intent to make change, and antecedent staff awareness of Quitline. Analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY), with P values of 0.05 or less considered statistically significant. No corrections for multiple comparisons were made. The analysis was deemed exempt from review requirements by both the University and the Department of Public Health Institutional Review Boards.

Results

Detailers visited 217 physicians across 84 practices throughout 36 different zip codes in Philadelphia. A total of 272 un-ad reminders were mailed, and 109 physicians (50.2%) completed follow-up visits; 49 participants received a total of 107 credit hours of additional instruction. The program website received 53,834 hits from 3,596 unique visitors during the project period. Nearly all physicians (98%) found the detailing visits useful, and over three-quarters (76%) planned to make practice changes based on the AD visits. Characteristics of the physician population, and the Philadelphia communities they serve, are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the physician/community populations

| Characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Physician characteristics | |

| Male sex | 53 |

| Practice type | |

| Solo practice | 13 |

| Small group (2–5 physicians) | 24 |

| Medium to large (>5 physicians) | 5 |

| Academic practice | 21 |

| Federally qualified health center | 31 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Program acceptance | |

| Found useful | 98 |

| Recommend to others | 86 |

| Would like another academic detailing visit | 76 |

| Plan at least one change | 76 |

| Community characteristics* | |

| Income below poverty line | 26.2 |

| African American | 44.3 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 13.0 |

| Language other than English | 21.2 |

| Did not complete high school | 19.6 |

Source: U.S. Census 2012 Estimates (available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov).

Physician baseline responses followed the expected pattern, with high self-reported rates of the simple components of the 5A framework, and significantly lower rates of complex behaviors. The categorical median for simple behaviors corresponded to “almost always” on the Likert scale, whereas complex behaviors were rated as “almost never” (mean score of 3.98 vs. 2.63, respectively; P < 0.001). After the AD intervention, mean frequency scores for complex behaviors increased significantly, from 2.63 to 2.92 (P < 0.001), corresponding to a clinically significant change in the categorical median from “almost never” to “sometimes.” Of particular interest was the rate of referral to the State’s free Quitline services. The AD intervention significantly improved self-assessment scores, from 2.45 to 2.97 (P < 0.001), corresponding to a small, but clinically significant, change. A statistical improvement in simple behavior mean scores was also noted (3.98 vs. 4.13; P = 0.035).

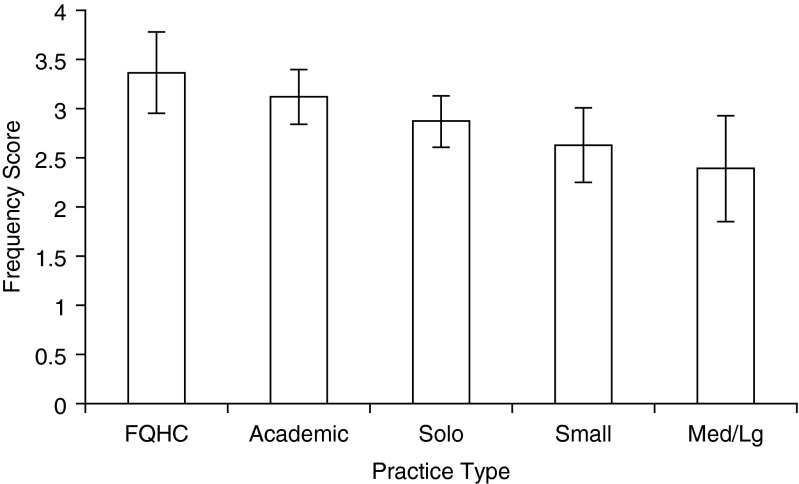

At baseline, complex behavior self-assessment scores were related to both sex and practice type. Female sex was a strong positive predictor of complex behaviors at baseline (R2 = 0.91; P = 0.03), whereas practice type was a more modest correlate (R2 = 0.51; P = 0.004). The relationship between sex and complex behavior scores was lost at follow-up, whereas the influence of practice type persisted (R2 = 0.69; P = 0.009). Physicians who practiced in federally qualified health center settings were significantly most likely to endorse complex behaviors, followed by physicians practicing in academic settings, followed by private practice physicians in a manner inversely proportional to practice size (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reported frequency scores of complex tobacco dependence treatment behaviors after academic detailing intervention. 1 = never; 2 = almost never; 3 = sometimes; 4 = almost always; 5 = always; FQHC = federally qualified health center; Med/Lg = medium/large. R2 = 0.69; P = 0.009. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Discussion

AD is an effective strategy for influencing the self-reported rates of complex tobacco treatment behaviors among physicians serving underserved and disadvantaged urban communities with high rates of smoking. The AD educational outreach approach was feasible and well received by physicians who saw it as an appropriate mechanism for changing clinical behaviors. Although physicians reported high baseline frequencies of simple 5A behaviors, rates of complex behaviors were significantly lower. Over 70% of the physicians surveyed endorsed performance of simple behaviors as either “always” or “almost always,” whereas only 29% similarly endorsed complex behaviors. After AD, over 38% of physicians reported performing complex behaviors “always” or “almost always”—representing a relative 30% increase in endorsement rates. A smaller, but statistically significant, improvement in “always/almost always” endorsement was observed for simple behaviors, increasing from 70% of the cohort to 78% at follow up. The more modest relative 11% increase in simple behavior endorsement was likely a function of the relatively high baseline rates, limiting the potential for improvement.

AD trainings were well received, with physicians both open to additional visits and willing to recommend the activity to colleagues. The strength of the AD approach resides in its ability to reach targeted, high-impact groups of clinicians, with personalized and highly relevant content. AD is a practitioner-centered approach, appropriate for all practice environments, including those without access to grand rounds or other group educational venues. AD is an inexpensive way to potentially increase physician engagement in complex treatment behaviors, and improve the care of a large number of smokers (18). Because the cost effectiveness of AD programs depends on both the relative proportion of patients who lack appropriate care for the target illness and the costs of convincing health professionals to promote therapeutic measures in this target group, the use of AD to promote tobacco use treatment in low socioeconomic status communities is likely to be highly cost effective (19).

Our study has several important limitations. Foremost is the inability to capture patient-level behaviors using this design. Because of concerns over patient confidentiality, we limited our metrics to physician self-report. Because of the effect of social desirability bias, we expect that the absolute rates of individual physician behaviors cannot be reliably estimated from our methods. However, in settings like this, in which there are no financial incentives linked to outcomes, there appears to be reasonable concurrence between relative patterns of self-reported behavior and the skills or behaviors demonstrated within the group (20, 21).

Our study was conducted in an urban area with high rates of smoking. Findings may not be generalizable to nonurban providers. However, the sample did include physicians from a mix of practice types and sizes. Further investigation into the influence of practice characteristics on uptake of AD messaging, and the potential for message attenuation over time, is warranted. Another possible limitation is the pre–post design. We sought to limit the potential effect of recall bias by waiting at least 2 months before reassessing behaviors to minimize the extent to which physicians could anchor their responses to the pretest value. Finally, we believe that our design, like that of similar studies to date, has limited potential to shed light on longitudinal process by which complex behaviors change (22). For example, some complex behaviors may indeed be mutable, yet “rate limited.” That is to say that improvement in some complex behaviors (e.g., arranging follow-up appointments) may be contingent upon first achieving significant change in others (e.g., billing). Future work should incorporate repeated AD interventions over longer periods of time to evaluate the rate and order in which AD interventions impact complex behaviors. Nevertheless, the present study demonstrates the feasibility and potential effectiveness of a low-cost and highly disseminable intervention to improve clinician behavior in the context of treating nicotine dependence in underserved communities.

Footnotes

Supported in part by grants derived from the Communities Putting Prevention to Work program (Cooperative Agreement no. 1 U58DP003557) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Pennsylvania Master Settlement Agreement through the Pennsylvania Department of Health, and National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA136888 and P30 CA016520.

Author Contributions: F.T.L. was responsible for conception and execution of the study and manuscript preparation; S.E.-C. was responsible for conception and execution of the study and manuscript preparation; S.G. was responsible for execution of the study and data collection; R.S. was responsible for conception of the study and manuscript preparation; G.M. was responsible for conception of the study and manuscript preparation.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Vital signs: current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years with mental illness—United States, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:81–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/ The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2014 [accessed 2014 Apr 13]. Available from.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) State Medicaid coverage for tobacco-dependence treatments—United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1340–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philadelphia Department of Public Health. http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/commissioner/2012AnnualReport_Tobacco.pdf Get Healthy Philly, Tobacco Policy and Control Program, annual report, 2011–2012. 2013 [created 2009 May; accessed 2014 Jul 21]. Available from.

- 6.Fiore M, Jaén C, Baker T, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, Dorfman SF, Froehlicher ES, Goldstein MG, Healton CG, et al. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/Public Health Service; 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solberg LIAS, Asche SE, Boyle RG, Boucher JL, Pronk NP. Frequency of physician-directed assistance for smoking cessation in patients receiving cessation medications. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:656–660. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamal A, Dube SR, Malarcher AM, Shaw L, Engstrom MC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tobacco use screening and counseling during physician office visits among adults—National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2005–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/download/55438/data/smokingcessationsummary.pdf Physician behavior and practice patterns related to smoking cessation. 2007 [accessed 2014 Jan 15]. Available from.

- 10.Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, Forsetlund L, Bainbridge D, Freemantle N, Davis DA, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD000409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dresser MG, Short L, Wedemeyer L, Bredow VL, Sacks R, Larson K, Levy J, Silver LD. Public health detailing of primary care providers: New York City’s experience, 2003–2010. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6suppl 2):S122–S134. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schauer GL, Thompson JR, Zbikowski SM. Results from an outreach program for health systems change in tobacco cessation. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13:657–665. doi: 10.1177/1524839911432931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young JM, D’Este C, Ward JE. Improving family physicians’ use of evidence-based smoking cessation strategies: a cluster randomization trial. Prev Med. 2002;35:572–583. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Philadelphia COPD Initiative. http://www.phillycopd.com [created 2009 May; accessed 2014 July 12]. Available from.

- 16.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211:453–458. doi: 10.1126/science.7455683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockburn J, Ruth D, Silagy C, Dobbin M, Reid Y, Scollo M, Naccarella L. Randomised trial of three approaches for marketing smoking cessation programmes to Australian general practitioners. BMJ. 1992;304:691–694. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6828.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandjour A, Lauterbach KW. How much does it cost to change the behavior of health professionals? A mathematical model and an application to academic detailing. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:341–347. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenthal A, Wang F, Schillinger D, Pérez Stable EJ, Fernandez A. Accuracy of physician self-report of Spanish language proficiency. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:239–243. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oxman TE, Korsen N, Hartley D, Sengupta A, Bartels S, Forester B. Improving the precision of primary care physician self-report of antidepressant prescribing. Med Care. 2000;38:771–776. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, MacLennan G, Bonetti D, Glidewell L, Pitts NB, Steen N, Thomas R, Walker A, Johnston M. Explaining clinical behaviors using multiple theoretical models. Implement Sci. 2012;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]