Abstract

Chronic pain and associated disability is a serious problem for a significant number of adolescents.

Individuals who parent an adolescent with chronic pain report high levels of impaired psychological and social functioning.

Parents of adolescents with chronic pain face unique parenting challenges.

Typically, treatment of adolescent chronic pain does not specifically focus on managing parental functioning and behaviour.

The relationship between parental functioning/behaviour and adolescent outcomes is complex and not yet fully understood.

Aim of the Review

The aim of this review is to examine the adolescent chronic pain literature to outline the problem of adolescent chronic pain and its impact in a wider social context. Discussion of the limited yet expanding literature will focus specifically on parental impact and the experience of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain. The review will examine the potential association between parental functioning, behaviour and adolescent pain-related outcomes.

Epidemiology of Adolescent Chronic Pain

Although ‘normal’ acute painful incidents for children, such as bumps and falls, are commonplace in everyday life1, less is known about the experience of ongoing ‘chronic’ pain in children. A minority of epidemiological studies have investigated the prevalence of chronic pain in children and adolescents. One community based study obtained a self, or proxy, report of pain experience in the previous three months from a sample of 5424 Dutch children and adolescents aged 0–18 years2. Results of this study indicated that whilst children and adolescents of all ages experienced pain (of any type) within the previous three months, prevalence rose rapidly during adolescence, with 68.9% of 12–15 year olds in this sample reporting having experienced pain in this time period. Overall, results demonstrated that 25% of children and adolescents reported recurrent or continuous ‘chronic’ pain for more than three months, whilst 8% reported intense, disabling chronic pain2.

Similar rates of adolescent chronic pain have been reported by smaller studies including those comprising 561 Spanish school children aged 8–16 years and 749 German school children aged 4–18 years respectively3,4. Nevertheless, it is important to note that epidemiological findings in this population typically originate from European studies with school focused recruitment strategies. It is thus possible that children with significant school absence or those who are home schooled may not be represented in the data, suggesting a degree of caution when extrapolating epidemiological findings to other, particularly non-European, populations.

Impact of Chronic Pain on Adolescents

Adolescents who experience chronically disabling pain also typically report poor functioning in numerous domains of daily living. For example, one UK study found that a sample of adolescents with disabling chronic pain reported elevated levels of depression and anxiety5. Similarly, results of a US study of adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia, found that adolescents with chronic pain also reported deficits in social functioning, which typically manifest themselves in difficulties participating in peer group activities and poor quality peer relationships6. Furthermore, results of another US study comprising a large clinical sample of adolescents with ongoing pain found that school absence and impaired school functioning was reported by adolescents, parents and teachers7. Nevertheless, the relationship between the presence of chronic pain and social functioning remains complex. For example, one US comparison study of children and adolescents with abdominal pain found that reported overt and relational peer victimisation moderated the association between chronic pain and school-related functioning8.

Adolescents with chronic pain also experience difficulties in other aspects of their lives. For example, a study involving a Dutch community sample found that adolescents with chronic pain reported difficulties in undertaking tasks of daily living such as obtaining good quality sleep and eating routine meals9. Thus, we know that chronic pain presents a unique set of challenges for a substantial number of adolescents, often preventing them from undertaking developmentally appropriate activities, such as attending school full-time or spending time with friends.

Impact of Adolescent Chronic Pain on Parents

Whilst the majority of research has focused on examining the impact of chronic pain on adolescent daily life, it is important to remain mindful of the fact that chronic pain occurs in a social context, and thus its impact extends to other individuals within the adolescent's family, such as parents. Conventionally, parents are primary caregivers and are therefore often responsible for organising appointments, making decisions about medical treatments and encouraging adherence to treatment for their child. Whilst this reason alone provides a good rationale for studying the impact of adolescent chronic pain on parents, there are additional reasons which support the importance of focussing attention on those individuals who parent an adolescent with chronic pain. For example, the findings of a small number of research studies have suggested that parents of adolescents with chronic pain have their own clinical needs. One UK self-report study of parental well-being found that many parents report elevated and often clinically significant levels of anxiety, depression and parenting stress10. Additionally, a separate Dutch study found that parents of adolescents with chronic pain reported impairment in social functioning and personal strain9. Parenting an adolescent with chronic pain has been associated with poor parental health and well-being, elevated levels of fatigue and parental experience of ongoing pain in US studies of parents of children and adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia11,12. Whilst a number of studies assume a causal relationship between parenting an adolescent with chronic pain and subsequent elevated levels of parental distress or ill-health, there is little evidence to support this supposition. Notably, one US study comprising a clinical sample of mothers of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease found that whilst 51% of mothers reported a lifetime history of depression, the majority of mothers experienced their first depressive episode prior to the onset of their child's condition13. Such findings suggest caution when interpreting the direction of the association between parenting an adolescent with chronic pain and parental well-being.

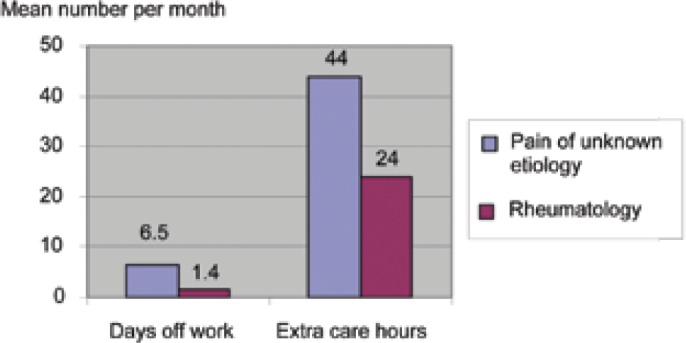

The impact of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain extends further, affecting many practical aspects of parental life. The practical and financial costs associated with parenting an adolescent with chronic pain of unknown etiology were compared with those of parenting an adolescent with a rheumatological condition in a UK study comprising 57 parents14. As demonstrated in Figure 1, practical ‘costs’ to parents in terms of having to take days off work to care for their adolescent and provide additional hours of care were significantly higher for parents in the (chronic) pain of unknown etiology group. Furthermore, a number of parents of adolescents in this specific group reported restrictions in terms of missed career opportunities as a result of needing to fulfil additional caretaking responsibilities for their adolescent.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the practical impact of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain of unknown etiology or a rheumatological condition8

Assuming that parents of adolescents with both organic and non-organic pain conditions face similar familial responsibilities (e.g. care of siblings), why is parenting an adolescent with a non-organic pain condition associated with such significant parental restriction? One could argue that parents of adolescents with chronic pain of unknown etiology may themselves report greater levels of emotional distress than parents of adolescents with organic pain conditions. Contrary to this explanation, no significant differences in parental emotional or social functioning were identified in a UK self-report study of parents of adolescents with non-organic pain and rheumatological conditions15. Perhaps a more plausible explanation involves consideration of adolescent self-report of pain-related disability. Interestingly, one self-report UK study found that adolescents with chronic pain of unknown etiology reported significantly higher levels of impaired physical, emotional and social impaired functioning than adolescents with rheumatological conditions16. Thus, it is possible that spending substantial amount of time with an adolescent who reports high levels of pain-related disability may be responsible for a greater number of parental caretaking activities and greater restrictions on parental daily life.

Discussion so far has focused on the multi-faceted aspect of parenting an adolescent with ongoing pain and its negative impact on parental life. Two UK based qualitative studies of parents of children and adolescents with a variety of chronic pain conditions have provided important further insight into the experience of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain. Results of these studies demonstrate that parents report distress regarding the uncertainty of their adolescent's future, a sense of challenge to their ability to effectively parent their adolescent, with a number of parents acknowledging a parenting style more typical for use with a much younger child17,18. The latter finding identifies another important reason for focussing our attention on parents of adolescents: the fact that parenting adolescents with chronic pain raises unique parenting challenges17. As the developmental literature demonstrates, parents typically report parenting an adolescent to be the most challenging period of their parenting career19. More specifically, individuals report difficulties managing issues of increasing adolescent autonomy and changing adolescent/parent relationships20.

Parents of adolescents with chronic pain experience these developmental parenting challenges in addition to a number of complex and often contradictory issues. For example, one qualitative study demonstrated that many parents spend substantial periods of time alone with their adolescent with chronic pain and devote time to encouraging their adolescent to develop appropriate sleep hygiene17. Such parenting behaviours are often very similar to those employed when parenting a much younger child and as such, are at odds with the need for parents to promote their adolescent's autonomy21. Dealing with competing pressures both places an additional burden on parents of adolescents with chronic pain and leaves them without knowledge of how to successfully parent an adolescent with ongoing pain. Developmental issues in the context of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain have received scant attention in the literature and it is possible that parents of adolescents with other chronic conditions of unknown etiology (e.g. chronic fatigue syndrome) may have similar experiences.

Parental Behaviour/Functioning

The majority of research conducted with parents of adolescents with chronic pain has, to date, focused on examining the impact on parental life and parental experience. However, what is important, is not only what is it like for individuals who parent an adolescent with chronic pain, but what parents actually do in response to their adolescent's experience of ongoing pain. A growing body of research, extrapolated from the adult chronic pain spousal literature, has begun to examine the potential association between parental behaviour and adolescent chronic pain outcomes. Parental response to adolescent pain has typically focused on examining the role of parental reinforcing behaviour, such as solicitous responses (e.g. parents encouraging their adolescent to stay home from school). One Canadian study examined maternal pain behaviour and acute pain responses of males (n=60) and females (n=60) aged 8–12 years in an experimental context22. Results interestingly demonstrated an association between parental solicitous behaviour and self-reported pain intensity for female children and adolescents only. Of course, the situation with regard to a clinical adolescent population is naturally more complex. One US observational study found no association between parental behaviour and adolescent functioning outcomes in healthy or chronic pain populations23, yet other studies have presented conflicting findings. Parental response to pain has been found to be predictive of adolescent catastrophizing in a US sample of adolescents with musculoskeletal pain24. It has also been shown to be predictive of functional disability, with functional disability being mediated by child anxiety and depression in a US self-report study of children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, sickle cell disease and headache25. The findings of the latter study provide some important insight by suggesting that perhaps it is rather simplistic to assume that the relationship between parental behaviour and adolescent outcomes is direct, but instead may be mediated by other variables.

As to be expected, studies have begun to examine the potential association between parental functioning and outcomes for adolescents with chronic pain. One variable which has featured in a number of studies is that of parental emotional functioning. A recent US self-report study found that maternal psychological functioning, in conjunction with child self-reported pain intensity, were significant predictors of child healthcare consultation for abdominal pain in a sample of children and adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome26. Whilst the results of this study highlight the important role that parents play in determining healthcare usage, it is important to note that inclusion criteria included only a two week history of abdominal pain, and thus it is not possible to claim that such findings would lend themselves directly to the chronic pain literature. Additional study of parental psychological functioning has identified a complex relationship with adolescent chronic pain outcomes. One UK study, comprising a clinical sample of parents of adolescents with chronic pain, found that whilst parental stress did not predict adolescent physical functioning, aspects of parental stress were predictive of adolescent social role functioning27. Another US study of 78 parents found that parental distress and family characteristics predicted 31% of the variance in functional disability in a group of children and adolescents with recurrent abdominal pain and migraine, after controlling for the effects of pain intensity28. Such findings support the idea that parental variables must be considered alongside adolescent self-report variables such as pain intensity, when trying to predict levels of adolescent functioning.

Methodological Issues

Whilst it is true that the existing literature has made important contributions to understanding how adolescent chronic pain impacts on individuals who parent an adolescent with chronic pain, it is important to note that there are a number of problems with existing studies. First, there is a dominant focus in the literature regarding the examination of maternal experience, with many studies only employing maternal samples9 or combined samples, of which only a small percentage of the sample comprise fathers10. Considering the increasing focus on parental involvement in the treatment of adolescent chronic pain, research should profitably focus on examining the experience of both parents and the specific context of the family. Second, it is imperative to mention the issue of directionality. This review has concerned itself with looking at the impact of adolescent chronic pain on parents, and also studies which have examined the relationship between parental and adolescent functioning. It is critical that caution is exercised when reviewing these findings as the evidence base is currently not yet sufficiently developed to infer causality. At best we can show associations between variables and speculate on potential reasons for such findings and their possible mechanisms. It is entirely possible that the relationship between adolescent and parental functioning is indeed bi-directional and mediated by additional variables.

Summary

This article has demonstrated the importance of studying individuals who parent an adolescent with chronic pain. The limited nature of this extant literature perhaps raises more questions than it answers, highlighting the importance of further good quality research in this area. This review has identified that parents are gate keepers for their children: they have their own clinical needs and face both practical and developmental parenting challenges which are unique to this patient population. Whilst a minority of treatment programmes have usefully begun to address parental needs10, this is rarely the main focus of such treatment. More research is needed to elucidate the exact nature of these parental clinical needs, and how treatment can begin to address issues of parenting in this specific population. Such research should focus on including fathers. Finally, this review has demonstrated the complex nature of the relationship between adolescent chronic pain outcomes and parental functioning and behaviour. Further research is needed to examine this potentially bidirectional relationship in detail and consider potentially mediating variables.

References

- 1.Fearon I, McGrath PJ, Achat H. ‘Booboos’: the study of everyday pain among young children. Pain 1996; 68(1): 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur A, Hunfeld JAM, Bohnen AM, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, Passchier J, van der Wouden JC. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain 2000; 87(1): 51–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huguet A, Miro J. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological study. J Pain 2008; 9(3): 226–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stoven H, Schwarzenberger J, Schmucker P. Pain among children and adolescents: Restrictions in daily living and triggering factors. Pediatrics 2005; 115(2): E152–E162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eccleston C, Malleson PN, Clinch J, Connell H, Sourbut C. Chronic pain in adolescents: evaluation of a programme of interdisciplinary cognitive behaviour therapy. Arch Dis Child 2003; 88(10): 881–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashikar-Zuck S, Lynch AM, Graham TB, Swain NF, Mullen S, Noll RB. Social functioning and peer relationships of adolescents with juvenile fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 57(3): 474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Logan DE, Simons LE, Stein MJ, Chastain L. School impairment in adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain 2008; 9(5): 407–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greco LA, Freeman KE, Dufton L. Overt and relational victimization among children with frequent abdominal pain: Links to social skills, academic functioning, and health service use. J Pediatric Psychol 2007; 32(3): 319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunfeld JAM, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, Passchier J, van Suijlekom-Smit LWA, van der Wouden JC. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatric Psychol 2001; 26(3): 145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eccleston C, Crombez G, Scotford A, Clinch J, Connell H. Adolescent chronic pain: patterns and predictors of emotional distress in adolescents with chronic pain and their parents. Pain 2004; 108(3): 221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid GJ, Lang BA, McGrath PJ. Primary juvenile fibromyalgia - psychological adjustment, family functioning, coping, and functional disability. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40(4): 752–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schanberg LE, Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Kredich DW, Gil KM. Social context of pain in children with Juvenile Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome: parental pain history and family environment. Clin J Pain. 1998; 14(2): 107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burke PM, Kocoshis S, Neigut D, Sauer J, Chandra R, Orenstein D. Maternal psychiatric-disorders in pediatric inflammatory bowel-disease and cystic-fibrosis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2004; 25(1): 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sleed M, Eccleston C, Beecham J, Knapp M, Jordan A. The economic impact of chronic pain in adolescence: methodological considerations and a preliminary costs-of-illness study. Pain 2005; 119(1–3): 183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan A, Eccleston C, McCracken LM, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain – Parental Impact Questionnaire (BAP-PIQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain. Pain 2008; 137(3): 478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken L M, Sleed M, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain 2005; 118(1–2): 263–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan AL, Eccleston C, Osborn C. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain. Eur J Pain 2007; 11 (1): 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smart S, Cottrell D. Going to the doctors: the views of mothers of children with recurrent abdominal pain. Child Care Health Dev 2005; 31(3): 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchanan CM, Eccles JS, Flanagan C, Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Harold RD. Parents' and teachers' beliefs about adolescents: effects of sex and experience. J Youth Adolesc 1990; 19(4): 363–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annu Rev Psychol 2006; 57: 255–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soenens B, Vansteenkiste M, Lens W, Luyckx K, Goossens L, Beyers W, Ryan RM. Conceptualizing parental autonomy support: Adolescent perceptions of promotion of independence versus promotion of volitional functioning. Dev Psychol 2007; 43(3): 633–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chambers CT, Craig KD, Bennett SM. The impact of maternal behavior on children's pain experiences: an experimental analysis. J Pediatr Psychol 2002; 27(3): 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid GJ, McGrath PJ, Lang BA. Parent-child interactions among children with juvenile fibromyalgia, arthritis, and healthy controls. Pain 2005; 113(1–2): 201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guite J, Rose J, McCue R, Sherry D, Sherker J. Adolescents with chronic musculoskeletal pain: the role of pain catastrophizing, psychological distress and parental pain reinforcement. J Pain 2007; 8(4): S62–S62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson CC, Palermo TM. Parental reinforcement of recurrent pain: the moderating impact of child depression and anxiety on functional disability. J Pediatr Psychol 2004; 29(5): 331–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, Feld LD, Whitehead WE. Relationship between the decision to take a child to the clinic for abdominal pain and maternal psychological distress. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006; 160(9): 961–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Eccleston C. Disability in adolescents with chronic pain: patterns and predictors across different domains of functioning. Pain 2007; 131(1–2): 132–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logan DE, Scharff L. Relationships between family and parent characteristics and functional abilities in children with recurrent pain syndromes: an investigation of moderating effects on the pathway from pain to disability. J Pediatr Psychol 2005; 30(8): 698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further Reading

- Palermo TM, Chambers CT. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: an integrative approach. Pain 2005; 119(1–3): 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]