Abstract

Background:

Chronic back pain is a serious public health issue, associated with poor quality of life and disability. There is a specific group of chronic back pain sufferers whose pain persists despite their having undergone anatomically successful lumbosacral spine surgery. These patients are known as having failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) and are frequently seen in pain clinics. It is currently unclear what constitutes routine practice in terms of diagnosis and treatment of FBSS in the UK.

Aim:

To map the diagnosis of and provision of care for patients with FBSS.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey of specialist pain clinics in the UK.

Results:

This first attempt to survey 241 pain clinics in the UK achieved a response rate of 52%. The results of this survey suggest that patients at UK pain clinics were often diagnosed with FBSS between 6 and 12 months after surgery. Treatment is often initiated when patients report a level of pain between 3 and 5 cm (on a 10-cm visual analogue scale) and a range of therapeutic options are pursued in the hope of addressing the range of presenting symptoms.

Conclusions:

It is evident from the findings of this survey that, though there is some variation, pain specialists in the UK identify and handle patients with FBSS as a separate clinical entity. Direct, randomised comparisons of interventions should be the focus of research into appropriate treatment regimens going forward. Also, evidence of clinical effectiveness will need to incorporate elements of patient acceptance of interventions.

Keywords: Low back pain, back surgery, chronic pain, primary care, pain clinic

Introduction

Chronic back pain is a serious public health issue, associated with poor quality of life, social disruptions, disability and inability to work.1 There is a specific group of chronic back pain sufferers whose pain persists despite their having undergone anatomically successful lumbosacral spine surgery. It is estimated that approximately 10–40% of individuals undergoing back surgery have a poor outcome.2 These patients are known as having failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS). Whilst it is difficult to provide an accurate estimate of the UK prevalence of FBSS, the condition is encountered frequently in many specialised pain treatment settings.

The largest study to date is a survey of 24,000 patients who underwent spinal surgery in Washington State, of whom 19% required reoperation.3

The nearest estimate of prevalence we have for FBSS is that for neuropathic back and leg pain, the UK prevalence of which is 5,800 per 100,000 population. Therefore, approximately 405,115 people in England and Wales suffer from neuropathic back and leg pain, costing approximately £2 billion a year.4 We would expect to see similar figures for FBSS.

Also, a review of the main procedures and interventions using summary data from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database 2009/10 (National Health Service, accessed August 2011) suggests that 117,803 surgical procedures have been conducted in the National Health Service (NHS) as surgery on bones and joints of spine. Although some of these will be undoubtedly related to trauma and deformity surgery, if we take a conservative estimate of only two-thirds of the surgeries falling under the scope of surgery for pain, that would mean 78,533 procedures are carried out annually. This translates to a conservative estimate of 7,853 (10%) and an upper estimate of 31,414 (40%) patients per year with FBSS in the UK.

Patients with FBSS have a low quality of life and high psychological morbidity and are frequent users of health services.5, 6–7 Patients with FBSS are a diverse group, with complex and varied aetiologies. Symptoms can include back pain, leg pain or both in varying proportions. Also, patients could experience weakness and spasm in the limbs, numbness and, possibly, bladder and bowel difficulties. The term ‘FBSS’ does not identify a cause or give clues to appropriate management.8 Further, such a term may leave the impression of a lack of precision in diagnosis and treatment.9 As a consequence, it is unclear what constitutes routine practice in terms of diagnosis and treatment of FBSS in the UK.

Therefore, a useful first step was to conduct a national survey across pain clinics in the UK to gather information on the nature of care provided for patients with FBSS. Information gathered in this survey and subsequent data could be used to map the nature of the diagnosis and care provided to patients with FBSS in the UK and plan future research in this area.

Methods

Sample selection

The survey was conducted in pain clinics around the country as, though these patients originate from different settings, they tend to gravitate towards pain clinics. NHS sites were identified as having pain services via a list of pain clinic or pain management services compiled for the National Pain Audit, which was conducted by Dr Foster Ltd (Dr Foster Ltd, accessed October 2010). This list was verified by the fourth of the present authors, and centres were excluded if it appeared that pain services were no longer provided or had changed at a particular locality, or in cases of duplication.

Questionnaire development

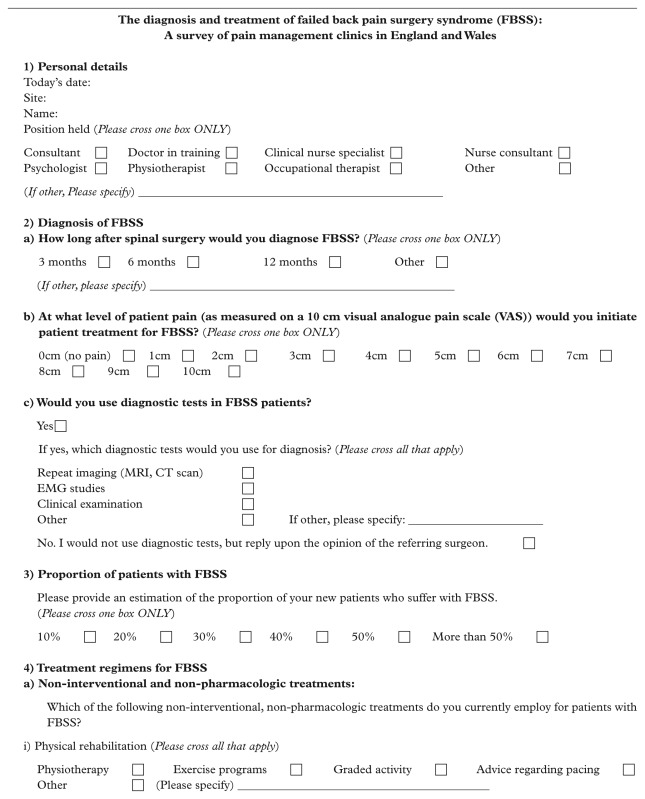

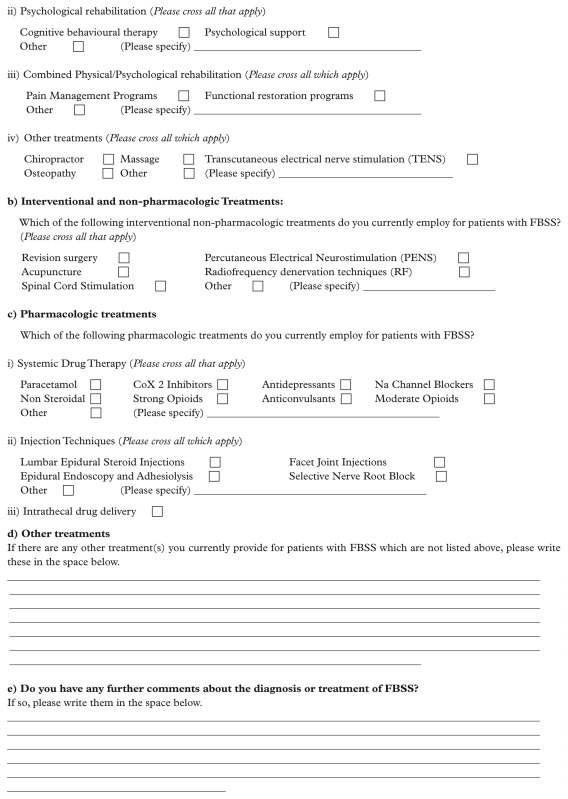

The questionnaire was developed with the intention of capturing as broad as possible an overview of current practice with regard to diagnosis and management of FBSS at a particular NHS site. It was designed to be relevant to varying modes of care delivery, including single centre- and community-based services. The questionnaire contained elements pertaining to how FBSS is diagnosed at the sites, the proportion of patients with FBSS and the treatment regimens used in such cases.

The questionnaire was divided into four sections (Appendix 1), all designed for structured responses, with question 4 also including a free text space for comments. The questionnaire was also designed with the following practical considerations: the majority of the questions were multiple choice, in order to ease completion, along with text fields for responders to share ideas and make further comments.

Study protocol and data collection

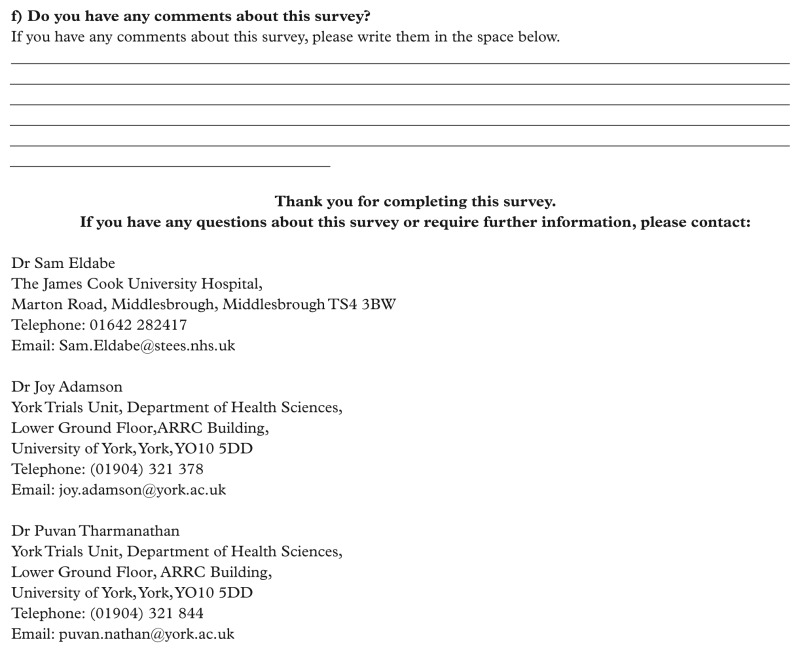

Questionnaires were sent out by post in October 2010 to 240 NHS sites in the UK, including England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The questionnaire was sent to the identified centres and addressed to the ‘Clinical Audit Lead’ (CLA). The covering letter provided information on the purpose of the survey and mapping study, and explained that we had planned the layout of the questionnaire to allow for an assessment of the services provided at the respective centres. The term ‘CLA’ was chosen as the best reference to ensure that the questionnaire would be completed by the appropriate clinician at the respective sites. A self-addressed envelope was sent along with the questionnaire and a postal reminder was sent to non-responders two weeks after the initial mailout in order to increase the rate of response. Questionnaires were returned by post. The questionnaire was re-administered at four weeks (in November 2010) and eight weeks (in January 2011) to all non-responders.

As the survey was considered a ‘service evaluation’, it therefore did not require ethical review by research ethics committees. Nonetheless, the survey was vetted by the Ethics Governance Board within the University of York, and all major aspects of the process, including questionnaire development, data collection and the analysis, adhered to ethical standards common to research practice.

Analysis

The responses were inputted into a Microsoft Access 2007 database. A summary of descriptive statistics was conducted using stata 11 (StataCorp). All free text comments were collated and categorised where possible.

Results

Response rate

There were 241 eligible sites in the initial mailing. Of these, 14 replied or returned the questionnaire stating that they do not provide services to FBSS patients. This left an effective sample of 227. Questionnaires were returned from 119 of these, which represents a 52% response rate. Four sites returned questionnaires largely unfilled, and were therefore excluded from the quantitative analysis. All percentages reported below are detailed in Tables 1-7 and calculated based on responses from 115 sites, unless stated otherwise.

Table 1 lists the position held by those completing the questionnaire. The majority of respondents were consultants (84%, 100/119). Of those who replied to the survey, 44 (37%) added free text comment, either in the allocated space or annotated in other sections of the questionnaire. The majority of the comments related to FBSS as a diagnostic category; more detail is given in the appropriate section below.

Table 1.

Position held by responder

| Position | Counts | % (n=119) |

|---|---|---|

| Consultant | 100 | 82 |

| Doctor in training | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 3 | 4 |

| Nurse consultant | 2 | 2 |

| Psychologist | 3 | 3 |

| Physiotherapist | 2 | 2 |

| Occupational therapist | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 9 | 8 |

Diagnosis of FBSS

Table 2 shows the length of time, with persistent pain, after spinal surgery that a particular respondent would diagnose FBSS. Most clinicians would make a diagnosis of FBSS if pain persisted 6 months (41%) or 12 months (34%) after anatomically successful surgery.

Table 2.

Length of time after spinal surgery before diagnosis of FBSS

| Diagnosis time | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 months | 10 | 9 |

| 6 months | 49 | 43 |

| 12 months | 40 | 35 |

| Other | 16 | 14 |

| Missing | 4 |

There were 16 respondents who also provided free text comments relating to the issue of FBSS as a diagnostic category. Most of these respondents questioned FBSS as a diagnosis; two stated that they had never come across this in clinical practice and others questioned the usefulness of FBSS, in particular in terms of the clarity regarding the underlying pathology and who would fall within this diagnosis:

Patients with different diagnosis do differently. Disc surgery (failed) is not the same as surgery for spondylosis (failed) and the whole thing depends on scan interpretation. What has actually changed post op needs to be carefully documented.

Linked to this were comments which suggested that FBSS as a diagnostic category was not particularly useful in terms of developing the most appropriate treatment plan:

I dislike the diagnosis and do not agree that this is a syndrome. This is simply mechanical or neuropathic back/leg pain in patients who have previously undergone back surgery. I do not treat them differently from other patients with mechanical/neuropathic spinal pain.

Others noted their dissatisfaction with the term itself, given the negative connotations of having this label:

Do we have to use this term? It is judgemental, implies all sorts of things to the patient and is unhelpful.

It is a poorly defined, unnecessarily pejorative label.

Level of pain for treatment initiation

The specific level of pain at which treatment for FBSS would be initiated, as measured on a 10-cm visual analogue pain scale10 was not provided by 27 respondents (23%). The reason for a lack of response was often (41%, 11/27) because a visual analogue scale (VAS) was not used as a means to measure pain in patients with FBSS at the particular centre.

Among the remainder who did respond, the majority (78%, 72/92) report starting treatment for FBSS when patients report a level of pain between 3 and 5 cm on the VAS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Level of pain on the visual analogue scale (VAS) after which treatment for FBSS was initiated

| VAS scale | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|

| Response not provided | 27 | 23 |

| 0cm (no pain) | 0 | 0 |

| 1cm | 0 | 0 |

| 2cm | 1 | 0 |

| 3cm | 19 | 17 |

| 4cm | 32 | 29 |

| 5cm | 21 | 18 |

| 6cm | 4 | 5 |

| 7cm | 9 | 9 |

| 8cm | 2 | 2 |

| 9cm | 0 | 0 |

| 10cm | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 4 |

Diagnostic test for FBSS patients

The majority of responding sites (82%) report using a diagnostic test in order to determine patients with FBSS (Table 4). Table 5 shows that this most commonly involved the use of further clinical examination (71%), followed closely by the use of repeat imaging (65%). These methods were used together in 68% of the responding centres. Electromyography studies were used in 20% of the responding sites, always in conjunction with other diagnostic methods. About 10% of respondents report use of other diagnostics such as psychological assessments, and information from patient history more generally.

Table 4.

Use of diagnostic test in patients with FBSS

| Diagnostic test used | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 94 | 82 |

| No | 21 | 18 |

| Missing | 4 |

Table 5.

Type of diagnostic test used

| Type | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|

| Repeat imaging | 75 | 65 |

| Electromyography studies | 21 | 18 |

| Clinical examination | 82 | 71 |

| Other | 12 | 10 |

| Missing | 4 |

Proportion of patients with FBSS

Slightly over half (53%) of the responding sites reported that about 10% of patients presenting to their clinic are diagnosed with FBSS (Table 6). The remaining sites reported about 20–30% as the proportion of patients presenting with pain who are eventually diagnosed with FBSS.

Table 6.

Proportion of patients with FBSS

| Proportion | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 61 | 53 |

| 20% | 27 | 23 |

| 30% | 20 | 14 |

| 40% | 2 | 2 |

| 50% | 3 | 3 |

| >50% | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 4 |

Treatment regimens for FBSS

Almost all responding centres (90%) used all modes of treatment together (i.e. non-interventional and non-pharmacological, interventional and non-pharmacological, and pharmacological options) when handling patients with FBSS.

As detailed in Table 7, when considering non-interventional and non-pharmacological options alone, responders reported that multiple methods of physical and psychological rehabilitation were applied in combination. However, pain management programmes dominated in the category of combination rehabilitation programmes, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) dominated in the category of other non-interventional treatment options.

Table 7.

Treatment regimens for FBSS

| Treatment category | Treatment sub-category | Treatment name | Counts | % (n=115) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-interventional and non-pharmacological treatments | Physical rehabilitation | Physiotherapy | 102 | 89 |

| Exercise programmes | 91 | 79 | ||

| Graded activity | 81 | 70 | ||

| Advice regarding pacing | 91 | 79 | ||

| Physical rehabilitation – other | 16 | 14 | ||

| Psychological rehabilitation | Cognitive–behavioural therapy | 88 | 77 | |

| Psychological support | 78 | 68 | ||

| Psychological rehabilitation – other | 21 | 18 | ||

| Combined physical/psychological rehabilitation | Pain management programmes | 99 | 86 | |

| Functional restoration programmes | 28 | 24 | ||

| Other combined rehabilitation | 8 | 7 | ||

| Other non-interventional and non-pharmacological treatments | Chiropractor | 1 | 1 | |

| Massage | 9 | 8 | ||

| Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation | 85 | 74 | ||

| Osteopathy | 4 | 4 | ||

| Non-interventional and non-pharmacological – other | 14 | 12 | ||

| Interventional and non-pharmacological treatments | Revision surgery | 17 | 15 | |

| Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation | 8 | 7 | ||

| Acupuncture | 63 | 55 | ||

| Radiofrequency denervation | 66 | 57 | ||

| Spinal cord stimulation | 45 | 39 | ||

| Interventional and non-pharmacological – other | 24 | 20 | ||

| Pharmacologic treatments | Systematic drug therapy | Paracetamol | 100 | 87 |

| COX2 inhibitor | 56 | 49 | ||

| Antidepressants | 106 | 92 | ||

| Sodium channel blockers | 49 | 43 | ||

| Non-steroidal | 68 | 59 | ||

| Strong opioids | 94 | 82 | ||

| Anticonvulsants | 104 | 90 | ||

| Moderate opioids | 101 | 88 | ||

| Systematic drug therapy – other | 19 | 17 | ||

| Injection techniques | Lumbar epidural steroid injections | 76 | 66 | |

| Facet joint injections | 76 | 66 | ||

| Epidural endoscopy and adhesiolysis | 14 | 12 | ||

| Selective nerve root block | 82 | 71 | ||

| Injection technique – other | 11 | 10 | ||

| Intrathecal drug delivery | 15 | 13 |

With regard to interventional and non-pharmacological treatment options used, radiofrequency denervation techniques were the most frequently chosen therapy, followed closely by acupuncture.

Among the systemic drug therapies, paracetamol, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and strong opioids were all used by more than 80% of respondents.

Among the injection techniques, selective nerve root block was the most commonly used (70% of repondents), with lumbar epidural steroid injections and facet joint injections also approaching the same level of usage (Table 7).

Discussion and conclusions

The rate of lumbar spine surgery in the UK remains low in comparison with the USA. The rates in the USA are currently five times greater than the UK and double that of other developed countries such as Australia, Canada, and Finland.11 In relation to this, uncertainty remains with regard to the diagnosis and management of patients who continue to experience pain subsequent to back surgery.

The results of this survey suggest that patients at UK pain clinics were often diagnosed with FBSS between 6 and 12 months after surgery, and treatment is often initiated when patients report a level of pain between 3 and 5 cm, as measured on a 10-cm VAS.10

These findings provide a snapshot of current practice in the UK and allow this to be placed within the context of the wider discussion as regards this condition. For instance, in a recent review, Chan and Peng suggest that the causes of FBSS are many and include preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative factors.12 It is reassuring that most centres in our survey make a definitive attempt to, if not diagnose, then explain to or reassure the patient presenting with pain subsequent to back surgery with a combination of imaging, examinations and electrical tests. Therapeutic interventions in this patient group were often used in combination. However, certain interventions were used more commonly; these include pain management programmes, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, radiofrequency denervation techniques and acupuncture.

The findings from our survey suggest that while it is evident that there is variation in the nature of patients who present with pain after back surgery, particularly with regard to the duration after surgery, practitioners associate FBSS with occurrence of pain symptoms a few months after surgery. Therefore, many pain centres see the need to distinguish these patients, although there were a minority of responders to our survey who found the label unhelpful. The usefulness of the term ‘FBSS’ has been called into question in the literature many times – especially because the only characteristic these patients have in common is that, following an operation for leg or back pain, back and/or leg symptoms persist or worsen.9

However, recent comparisons2,13 suggest that patients diagnosed with FBSS have a much worse quality of life (QoL) score than patients with other causes of neuropathic or nociceptive pains such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and osteoarthritis. This highlights the need to treat patients with FBSS separately from those presenting with other forms of pain and for a more evidence-based guidance to the management of patients diagnosed with FBSS, based on evidence generated from studies in this patient group.

With regard to treatment options, clinical responses to FBSS are varied, scientifically unproven and often costly.7 Pain clinics in the UK seem to be in step with practice in Europe and North America3, 12, 14 whereby a range of therapeutic options are pursued in the hope of addressing the range of presenting symptoms. While all these therapies are provided by pain clinics on the broad assumption that patients with FBSS suffer from mixed neuropathic and nociceptive pain, there is no clear evidence that these therapies are clinically effective or cost effective. In relation to this, there is limited use of joint therapeutic options, namely methods which combine psychological and physical rehabilitation, which may be a more suitable mode of treatment in this patient group given that the syndrome consists of multiple pain components with a marked impact on mood and function.13

This interdisciplinary approach to conventional medical management, including physical therapy and pharmacotherapy, alongside possible psychological/behavioural interventions, is necessary given that sufferers of FBSS are difficult to place within a clinical speciality. Originally they come from surgery, but they may no longer be surgical candidates. They tend to be referred to the pain clinic, where treatment recommendations for FBSS are currently similar to those recommended for any chronic pain condition.13

In the light of this, these findings from our survey on UK practice stand against a backdrop of a lack of consensus with regard to an algorithm of care. Van Buyten and Lindroth published the most recent attempt at an algorithm of care for FBSS (Van Buyten and Linderoth, 2010). However, the authors acknowledge that many of the treatment recommendations derive from evidence based on pure neuropathic pain conditions such as diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia with a limited follow-up of 6 months. Specifically, the algorithm has a heavy bias towards neuromodulation and patients with predominant leg pain, a group for which neuromodulation has been shown to provide superior outcomes to either conventional management or reoperation.

However, to date, the impact of traditional neuromodulation techniques on back pain in FBSS remains modest.9, 15

Although the work by Van Buyten and Lindroth14 provides a good starting point, there is a need for a more evidence-based algorithm of care/treatment pathways for patients with FBSS. The need for tailored guidance that informs practice with regard to the care of patients with FBSS is also important given the high cost of care. A recent analysis estimated a net result of 9% of patients achieving 50% pain relief; this poor success is at a cost of approximately £7,000 per annum per patient.7 The need for this guidance is made urgent given the climate of belt-tightening in health services16 and the as yet unaddressed problem of meeting patient needs based on the current approach to care for patients with FBSS.5

There has been continuing interest in improving care for the diverse group of patients classified as suffering from FBSS. Although there has been considerable debate over whether these patients should be handled as a single patient group, as discussed above, more recent evidence points to a more common profile with regard to quality of life and efforts needed to restore the functioning of patients with FBSS. In this first attempt to map the current management of FBSS, our survey provides useful insight to practice in pain clinics, where most patients with FBSS receive care in the longer term. It is evident from the findings that, though there is some variation, pain specialists in the UK identify and handle these patients as a separate clinical entity. The use of a wide range of therapeutic options in the management of FBSS among the clinics surveyed fits with the general lack of consensus on and evidence of effectiveness for the various interventions currently used. Direct, head-to-head randomised comparisons of these interventions should be the focus of research going forward. Given the long-term nature of this condition and multidisciplinary management of these patients, evidence of clinical effectiveness will need to incorporate elements of patient input in the diagnosis process and acceptance of interventions.

Study limitations

Although the survey had a response rate of over 50%, the practice at pain clinics that did not respond may differ from those that did. Our results have a heavy skew towards the opinions of pain consultants, and therefore do not capture the views of those involved in the joint care of patients with FBSS. Also, the survey was not extended to specialists in rheumatology or neurology, who may care for these patients in the longer term. The responses to therapies offered to patients with FBSS did not allow for the clinician to prioritise and describe their algorithm of care. Importantly, there is a need for follow-on work to capture the views of patients with FBSS in the primary care setting.

Acknowledgments

Ethics approval for this research was granted by the Ethics Governance Board within the University of York. The authors acted independently in the design, conduct, analysis and decision to submit this research for publication. The authors have access to all data.

None of the authors has support from any commercial organisation for the submitted work. SE has received research grants and honoraria from Medtronic and Boston Scientific Neuromodulation in the previous 3 years. None of the authors’ spouses, partners or children has financial relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work. All authors have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Appendix

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by the York Trials Unit, University of York. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Author contributions: SE and JA conceived the study, and oversaw the overall execution of the project. RA developed the questionnaire. PT conducted the survey and analysed the findings. All authors contributed to the drafting of the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the version to be published.

References

- 1. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S. (2006). Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ 332, 1430–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomson S, Jacques L. (2009). Demographic Characteristics of Patients with Severe Neuropathic Pain Secondary to Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Pain Practice 9, 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ragab A, deShazo RD. (2008). Management of Back Pain in Patients with Previous Back Surgery. The American Journal of Medicine 121, 272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taylor RS. (2006). Epidemiology of Refractory Neuropathic Pain. Pain Practice 6, 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Talbot L. (2003). Failed back surgery syndrome. BMJ 327, 985–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDermott AM, Toelle TR, Rowbotham DJ. (2006). The burden of neuropathic pain: results from a cross-sectional survey. European Journal of Pain 10, 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manca A, Eldabe S, Buchser E. (2010). Relationship between Health-Related Quality of Life, Pain, and Functional Disability in Neuropathic Pain Patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. Value in Health 13, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques L, et al. (2007). Spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management for neuropathic pain: A multicentre randomised controlled trial in patients with failed back surgery syndrome. Pain 132, 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar K, Taylor RS, Jacques L, et al. (2008). The Effects of Spinal Cord Stimulation in Neuropathic Pain Are Sustained: A 24-Month Follow-Up of the Prospective Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial of the Effectiveness of Spinal Cord Stimulation. Neurosurgery 63, 762–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A. (1983). The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 17, 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. (1994). An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine 19, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan C, Peng P. Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (2011) Pain Medicine 12, 577–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eldabe S, Kumar K, Buchser E. (2010) An Analysis of the Components of Pain, Function, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome Treated with Spinal Cord Stimulation or Conventional Medical Management. Neuromodulation 13, 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Buyten J-P, Linderoth B. (2010). “The failed back surgery syndrome”: Definition and therapeutic algorithms - An update. 4, 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- 15. North RB, Kidd DH, Petrucci L. (2005). Spinal Cord Stimulation Electrode Design: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled Trial Comparing Percutaneous with Laminectomy Electrodes: Part II-Clinical Outcomes. Neurosurgery 57, 990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gulland A. (2011) NHS managers are more worried about financial squeeze than reform, survey finds. BMJ 342. [Google Scholar]

Web references

- Dr Foster Research Ltd. The National Pain Audit: http://www.nationalpainaudit.org/ (London: ). [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service. Hospital Episode Statistics Online: http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/ (London: ). [Google Scholar]