Abstract

Chronic pain is a long-term condition, which has a major impact on patients, carers and the health service. Despite the Chief Medical Officer setting chronic pain and its management as a national priority in 2008, the utilisation of health services by patients with long-term conditions is increasing, people with pain-related problems are not seen early enough and pain-related attendances to accident and emergency departments is increasing. Early assessment with appropriate evidence-based intervention and early recognition of when to refer to specialist and specialised services is key to addressing the growing numbers suffering with chronic pain. Pain education is recommended in many guidelines, as part of the process to address pain in these issues. Cardiff University validated an e-learning, master’s level pain management module for healthcare professionals working in primary and community care. The learning outcomes revolve around robust early assessment and management of chronic pain in primary and community care and the knowledge when to refer on. The module focuses on the biopsychosocial aspects of pain and its management, using a blog as an online case study assessment for learners to demonstrate their knowledge, understanding and application to practice. The module has resulted in learners developing evidence-based recommendations, for pain management in clinical practice.

Keywords: Chronic pain, primary, community, pain, biopsychosocial, patient, interprofessional learning, e-learning, adult learning, blog, weblogs, case study, education, evidence-based, MSc level, pedagogy, university, online collaboration, distance, online learning

Summary points

Chronic pain will continue to be a problem for patients and an economic problem for healthcare;

Improving pain management in primary and community care involves educating healthcare professionals;

Postgraduate short e-learning pain modules are one approach to delivering this;

E-learning pain education can facilitate interprofessional learning;

Pain education can inform evidence-based practice;

More formal education is required.

Introduction

Chronic pain has been defined as continuous, long-term pain of more than 12 weeks or after the time that healing would have been thought to have occurred after trauma or surgery.1 In 2009, the Chief Medical Officer revisited chronic pain and its management as a national priority.2 Chronic pain is now recognised by the Department of Health (DoH) as a long-term condition (LTC) in its own right but does not appear to receive the same recognition and resources as other chronic conditions have. In England, 15.4 million people have one or more LTCs. This accounts for more than 50% of appointments within general practice.3 The utilisation of healthcare services among those with chronic conditions is the highest, and they represent 30% of the population and 70% of National Health Service (NHS) and social care in England spending.4 The number of patients with LTCs is expected to rise, with many of these patients experiencing pain; therefore, the impact on NHS budgets will inevitably increase. The Health Survey for England (2012) reported that 14 million people suffer with chronic pain.5 ‘Each year over five million people in the United Kingdom develop chronic pain, but only two-thirds will recover’, and it is estimated that 11% of adults and 8% of children suffer severe pain (7.8 million people in the United Kingdom).2,6 This may result in an increased use of services already burdened with unscheduled care provision.

There have been a number of initiatives to obtain reliable evidence of the problem and the provision of strategies for improved pain management.5–8 However, the management of pain continues to pose many challenges for patients, carers and healthcare professionals, striving to deliver effective, evidence-based management to patients. Changes in NHS commissioning structures in England and the financial problems across the United Kingdom have resulted in healthcare professionals having to review and justify the treatment options and services that they provide. Self-management approaches are key to successful outcomes, and ensuring that carers have an important role in the management of pain needs to be addressed.3,9–12

Only 2% of patients with chronic pain are managed by specialist pain services.10,13 Patients will primarily seek medical advice from a primary care healthcare professional. Most acute pain will be effectively managed at this point. Patients who have complex and or chronic pain-related issues may require referral to a specialised/specialist pain management service for assessment and management, but others can be managed in primary care. Therefore, a need for seamless working and referral is required to ensure that multidisciplinary working facilitates appropriate pain management across all areas of care. However, the Pain Audit reported that 20% of patients in England and 50% in Wales are not being seen in pain clinic, within the 18-week set standard.6 Patients should therefore be continuously assessed and managed in the community until they are seen by a specialist service. Early intervention with appropriate evidence-based management of pain is essential; reducing the risk of long-term pain may have an impact on reducing the current pain-related burden, including the economic burden.13,14

The need for pain education in primary care is endorsed by the British Pain Society and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), and the Anaesthetic Profession is being led by the Faculty of Pain Medicine. Currently, in the United Kingdom, postgraduate pain education is delivered through courses, either requiring attendance or participation through distance and/or e-learning. A range of opportunities exist from continued professional development credits to higher degrees. Higher degrees aim to develop specialist knowledge and evidence-based practice, through critical thinking and clinical application. Pain management education is not compulsory for undergraduate, or postgraduate healthcare education despite recommendations.15 However, with the increasing recognition of pain as a LTC and initiatives to improve the assessment, and initial management of patients in primary and community care, more professionals outside the specialist and specialised pain arena are enrolling in postgraduate educational courses.

This article presents the introduction of an innovative e-learning foundation module in primary and community care pain management delivered by Cardiff University and the outcomes of the learner cohorts to date.

Defining the educational approach

MSc level education

Cardiff University delivers postgraduate healthcare education at master’s degree level (level 7). All courses and modules run by the Department of Anaesthetics, Intensive Care and Pain Medicine are developed according to the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) Code.16 Based on the QAA code, it is essential for learners to demonstrate:

Originality in the application of knowledge;

An understanding of how the boundaries of knowledge are advanced through research;

An ability to deal with complex issues both systematically and creatively;

Originality in tackling and solving problems.

The aims, learning outcomes and assessment of pain education in primary and community care were developed to facilitate learners to evidence the qualities and competencies that are required to manage complex pain management issues in primary and community care.

This QAA code for master’s level education is centred around the development of evidence-based healthcare, its application to practice and identifying areas for research in clinical practice. Within healthcare, the overall aim would be to provide appropriate and improved patient care.

Adult learning

At master’s level, students are encouraged to critically analyse the literature and its findings, and synthesise and reflect on their clinical practice. Therefore, aiming to teach adult learners to ‘learn how to learn’, thus enabling lifelong learning. This is based on the cognitivist model, and the aim is for the locus of learning to be with the learner and their thought processes rather than the external environment.17

It could be argued that if individuals have chosen a course that is directly relevant to their clinical work, they are more likely to engage and understand the learning process and will naturally employ a deep approach to learning and synthesise the gleaned knowledge to practice.

E-learning

E-learning is defined as ‘learning facilitated and supported through the use of information and communications technology’.18 The drive to develop the e-learning module within Cardiff University was necessitated by several key factors, including institution frameworks, directions and vision. It was also the response to an emerging learner population for which face-to-face classroom attendance is increasingly more difficult (such as reduction in study leave and lack of funding) and in whom advances in the delivery and quality of teaching are expected.19

The opportunities afforded by e-learning programme delivery have been widely reported, including offering learners increased control over learning sequence, pace of learning, providing effective support mechanisms and removing time obstructions.20,21 Geographical barriers are broken down allowing educators to promote programmes to a wide cohort of learners, from a variety of backgrounds, and disciplines, who can tailor content to their experiences to meet their personal learning objectives.

Learners are encouraged and supported to participate and engage with module content in the form of online interactive modules, podcasts, videos and voice-over presentations. Learning opportunities exist with support via asynchronous tools such as the discussion boards and development of module assessment.

Interprofessional education and learning

Interprofessional education ‘… occurs when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care’.22 The rationale for including interprofessional learning principles was underpinned by service demands around team-working, shared knowledge, professional development and collaboration (Table 1).

Table 1.

The values and processes recommended within interprofessional education and learning.22

| Values | Processes |

|---|---|

|

|

As the module is interprofessional, the aim, particularly in the use of blogs, is to allow students to interact with other professionals involved in pain management so that they learn from the course faculty, the content and also from each other. This can help to encourage the students to reflect on how they and others can best manage patients and foster interprofessional working. The other advantage is that students enter the course with a variety of knowledge and experiences (Table 2).

Table 2.

The outcomes recommended within interprofessional education and learning.22

| Outcomes |

|---|

|

Research perspective on the role of blogs in education

Historically, master’s level outcomes were assessed using assignments. These assignments had word allowances that were very restricting, in terms of students illustrating their ability to work at master’s level. They also did not promote interprofessional practice, important for the application of learning to clinical teams. In fact, there was some criticism by students that the courses were MSc courses in assignment writing. Blogs are often referred to as interactive online diaries. Typically, blog users create posts, or entries, which form the body of the assessments. Opportunities exist for users (both blog authors and visitors) to post comments on entries, which, in turn, form reactions and conversation dialogues. Educationalists suggest that learning is socially constructed through language and is in some way collaborative, and learning theory underpins the rationale for utilising blogs within a learning environment.23,24

Blogs are used within the module as part of the summative assessment process, designed to demonstrate the extent of a learner’s success in meeting the assessment criteria. These criteria are aligned with the intended learning outcomes of the module and contribute to the final mark awarded for the module. Learners are required to record all of their assessment writing for the module within a personalised blog area, and are tasked with commenting and contributing to other learners’ blogs. A framework and timetable for developing the blogs were found to be essential in keeping learners focused on the task at hand, as unstructured blog entries can be difficult to read and manage.25–27

The blog platform houses the module content and is used in combination with the virtual learning environment (VLE). This helps with the familiarisation and adoption process for learners and provides a ‘gated wall’ environment, which is not publicly available, which may address some concerns over privacy and security.

Scholars have highlighted the potential benefits of using a blog platform for students to record academic reflections, uncover elements of the hidden curriculum and promote professional development.28 The process of analysing, reconsidering and questioning experiences within a broad context of issues is seen as useful in the learning process.29 Critical reflection is seen as an important skill in the healthcare setting, allowing practitioners to learn, grow and develop in and through their practice.30,31 One key aim of using a blog platform in our work is to build upon the benefits of interprofessional learning and promote transferable skills, such as judgement making through self- and peer assessment.32

Module and faculty demographics

The Foundation in Primary and Community Pain Management is a part time, 14-week, e-learning module that does not require any physical attendance. It is also interprofessional and provides 20 credits at level 7 (MSc level). Central to the module philosophy is evidence-based multidisciplinary working. It was designed to support the development of enhanced competencies within primary and community care health professionals, which would complement specialist and specialised pain services. For example, the Courses’ Director, Dr Ann Taylor, was a member of the working group who developed the DoH ‘Practitioners with a Special Interest in Pain’ (PwSI) competencies. During this process, it became clear that, to our knowledge, no training of education was available to support these competencies. Therefore, the faculty expanded to work with a range of clinical experts, from primary and community care, to develop the foundation module.

The first foundation module started in April 2011, and now runs twice a year. It recruits healthcare professionals working in primary and community care and is endorsed by the RCGP.

Three academics support the learners as well as four clinical experts from primary care. This includes a primary care physician, consultant nurse, counselling clinical psychologist and the RCGP’s clinical pain champion. An e-learning technologist is also available to support learners and the faculty with any technological support.

Module objectives and content

The module is aimed at non-pain specialists who want to enhance their knowledge and skills in pain assessment, screening and management. It aims to provide the learner with the opportunity to gain an understanding of the biopsychosocial model in relation to pain and its management and to evaluate clinical pain management options. The emphasis is on

Robust, valid and reliable assessment and screening tools enabling the learner to reflect on best approaches to care and trigger early referral for complex pain problems;

Evidence-based approaches to pain management within primary and community care recognising the generalist nature of those working in and the constraints which are unique to these environments. This enables an analytical approach to pain management options involving patients in shared decision-making processes;

Interprofessional education supporting team-working and collaboration across a range of healthcare professionals.

On completion of the module, a learner will be able to

Identify and reflect on the most appropriate, evidence-based approach to pain assessment, including appropriate tools for use in primary and community care grounded in a biopsychosocial approach;

Apply pain physiology in understanding the different types of pain and in recognising the difference between pain that has a definable cause and pain as an LTC;

Reflect on the principles of managing a patient with pain from a biopsychosocial perspective within the primary and community care setting, including managing patients with concomitant mental health problems;

Evaluate the theoretical basis of the various models of delivering pain management and be able to apply these models in practice, reflecting on the local population needs, the NHS systems, complementary care and clinical settings.

Module delivery

A relatively flexible e-learning approach means that healthcare professionals from all over the world can undertake the module. Evidence-based module content has been developed by keynote speakers and clinical experts from primary and community care and includes a range of different types of media to address differences in learning styles, for example, voice-over power-point presentations, podcasts, written text and so on. Much of this media can be viewed via mobile handheld devices, enhancing the flexibility and adult learning principles.

Because many of the learners are new to e-learning, narrated video guides are provided to explain how to use the module area and access module content. The e-learning technologist is able to develop new guides for individual learner needs, as and when needed. In order to reduce the ‘feeling of isolation’ that some may experience, students can liaise with the module team and the rest of the cohort, via discussion forums, email and telephone.

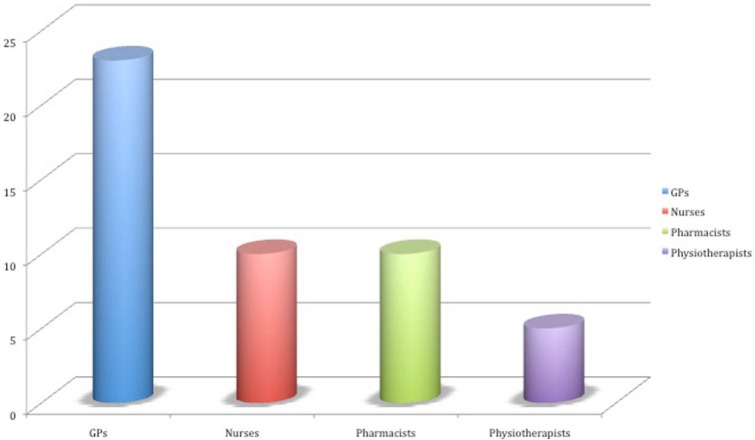

Student cohorts

The cohorts have consisted of healthcare professionals from the United Kingdom and two from overseas. Please see Figure 1 for the types of healthcare professionals who started the module. The majority are general practitioners (GPs), but the presence of other disciplines in the cohort and the multiprofessional nature of the faculty ensure interprofessional learning.

Figure 1.

A breakdown of the different healthcare professionals who started the module since April 2011 (48 learners).

GP: general practitioner.

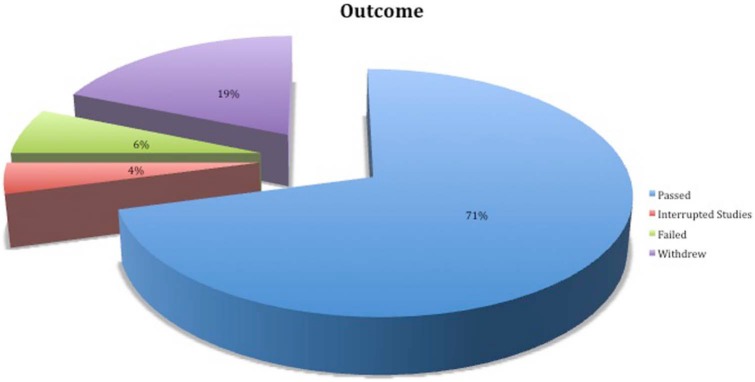

Please refer to Figure 2 for the academic outcomes of the cohort since module started in April 2011.

Figure 2.

Learner outcomes presented in the format of pass, fail, interruption of studies and withdrawn.

The majority of learners completed the module. The withdrawal rate for e-learning courses is 20–40%.33–35 This module is below the average withdrawal rate, and the reasons for withdrawal were generally due to personal, or work commitments.

Method of assessment

The ongoing assessment, a critical reflection of a patient case study, is developed over a 12-week period. It is a written academic piece of work, developed online through individual blog postings. To enable learners to demonstrate and apply their learning to practice, their summative assessment is a patient case study of their choice. The faculty provides support and advice, in how to chose and present the case study. Learners are encouraged to select a patient with complex or problematic pain with which they develop a reflective review of assessment and management approaches using a biopsychosocial model. This is followed by the development of evidence-based recommendations for future care. Continual academic support is provided by the faculty throughout this process to ensure accurate understanding of the module content and the identification of appropriate, evidence-based clinical recommendations.

The use of case studies can be viewed as a constructivist approach to learning, and helps bridge the theory practice gap.36 Through case studies, the learner can reflect on their own practice and consider whether the pain management/intervention used was based on evidence or not. From previous feedback, the students prefer blogs as they were able to build upon their work throughout and had timely feedback at set time points, which were set within the timetable.

To facilitate interprofessional learning, students are put into groups where they can support and reflect on each other’s blogs.

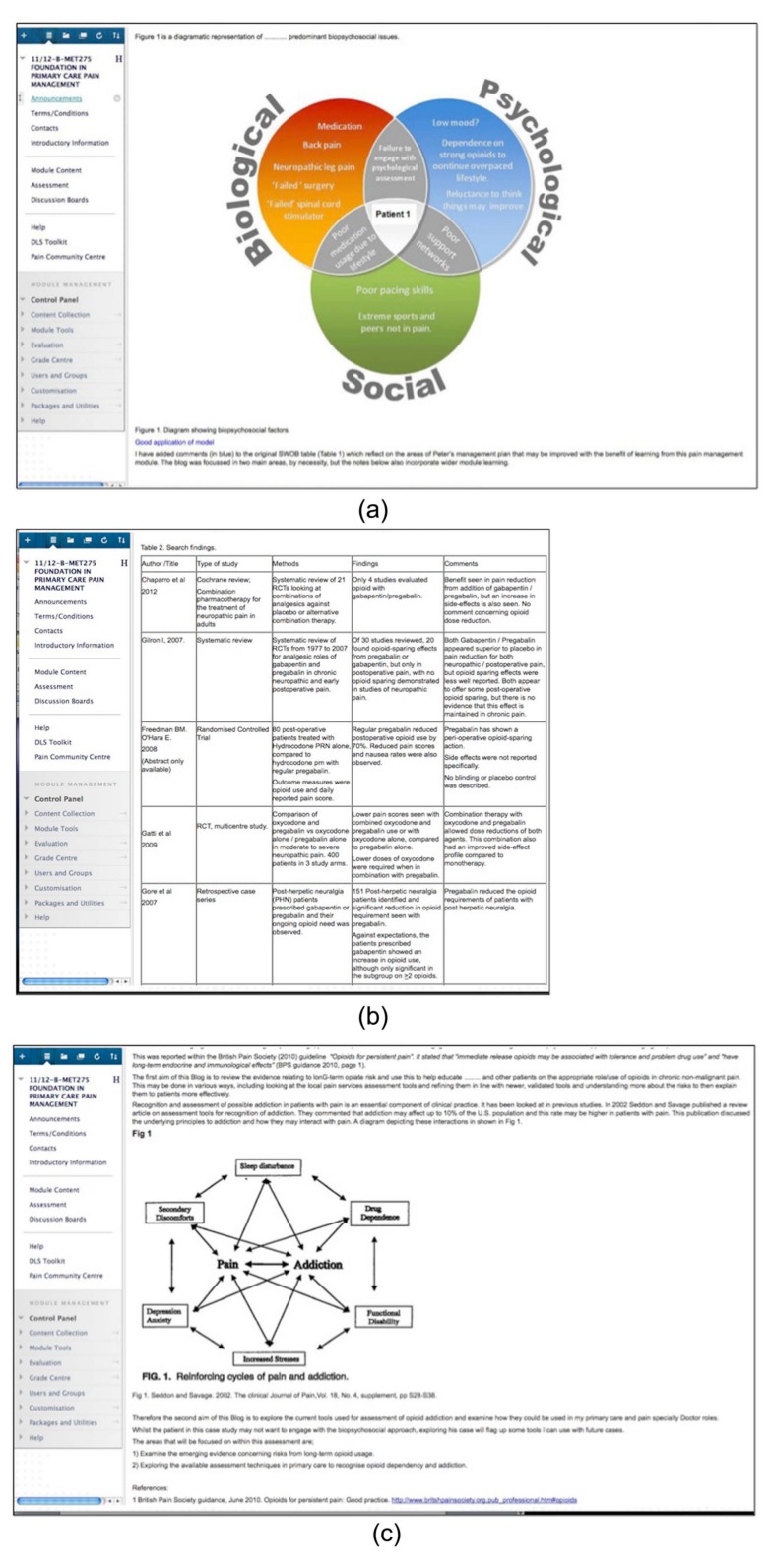

Learner blogs

Figure 3(a)–(c) provides examples of the type of content that learners can include within their blog assessment. The learner in Figure 3(a) used a diagram to demonstrate his or her understanding of how the biopsychosocial model relates the assessment of their patient case study. The learner in Figure 3(b) used a table to present a critical review of evidence to inform clinical recommendations. The learner in Figure 3(c) also used a diagram to inform and support the reflective written content of their blog.

Figure 3.

(a) An example of how a diagram can be used within a blog, to present the biopsychosocial assessment of a patient, (b) an example of how a learner used a table to present a critical review of evidence to inform the written text within the blog and (c) an example of how a diagram can be used to demonstrate the reinforcing cycles of pain and addiction, within the blog.

Tables, diagrams and figures are not counted within the word limit, which provides the learner with more words for reflection, synthesis and clinical application (MSc level writing and evidence-based practice).

The blogs are marked using a validated marking criteria. The credibility of marking the criteria was confirmed by the postgraduate board of studies and addresses the moderation of master’s level requirements (QAA). Overall, students need to demonstrate and present

Their knowledge, understanding and application of the biopsychosocial model;

Evidence-based recommendations/changes to the management of the patient case study;

A written analytical and reflective account;

A good standard of presentation.

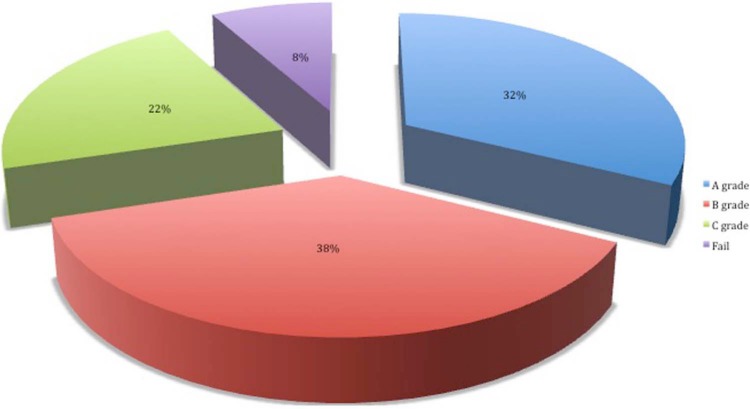

Figure 4 presents the results of learners who have completed the module. Reflecting on the results, the number of A and B grades demonstrates that 70% of students are developing case studies that include a high standard of master’s level reflective and analytical thinking, evidence-based practice and clinical application.

Figure 4.

The results of all learners who completed the module. They are presented as A, B and C grade pass, or as a fail.

Table 3 presents the types of patient case studies learners chose to focus their assessment on. The majority of learners selected patients with low back pain, fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome. Two chose to focus on pain following torture, very complex cases.

Table 3.

The type of patient case studies, learners selected for their blog assessment.

| Case study type | Number of Students |

|---|---|

| Low back pain | 14 |

| Fibromyalgia | 6 |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | 5 |

| Painful diabetic neuropathy | 4 |

| Knee pain | 3 |

| Neuropathic pain | 2 |

| Victim of torture | 2 |

| Stroke pain | 1 |

| Perineal | 1 |

| Facial pain | 1 |

| Chronic abdominal pain | 1 |

| Neck pain | 1 |

| Osteoarthritis | 1 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 |

Table 4 presents the specific areas of pain and/or its management that learners chose to focus their evidence-based reviews on. They had to select two areas to focus on. While many learners focused on pharmacological approaches, many examined the biopsychosocial factors and their management.

Table 4.

The pain-related areas that learners examined within their blog assessments.

| Assessment and diagnosis | Social Aspects |

| Assessment tools | Social life |

| Diagnostic tools | Working |

| Addiction assessment | Social communication model |

| Self-efficacy | Psychosocial influence |

| Pharmacological | Pain management approaches |

| Pharmacological (drugs) | Self-management |

| Opioids | Pain management programmes |

| Opioid dependency | Goal setting |

| Adherence to medication | Cognitive behavioural therapy |

| NSAIDs | Acceptance and commitment therapy |

| Distraction therapy | |

| Biological | Mirror therapy |

| Sleep | Patient education |

| Biblio-therapy | |

| Psychological | Graded expose to techniques |

| Depression | Rehabilitation |

| Catastrophising | TENS |

| Anxiety | |

| Fear-anxiety | |

| Coping | |

| Compliance | |

| Role of bereavement | |

| Nocebo |

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TENS: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Tables 3 and 4 demonstrate that a wide range of case studies and pain management issues were considered. Learners identified an area of interest, and through collaboration with the faculty, they developed a patient case study, to address their individual learning needs and to fulfil master’s level requirements. As part of the summative assessments, learners had to read and comment on their peers’ blogs, which therefore exposed them to other pain conditions and management approaches. The resulting discussions and debates enhanced the interprofessional nature of the module. Having a faculty of clinical experts from primary care ensured that appropriate educational and clinical support was available.

Some examples of specific evidence-based recommendations made by learners within their individual blogs include the following:

That a patient be referred for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in primary care;

Amendments to analgesic modes to enhance efficacy, for example, move from oral opioid therapy, to the use of patches;

Introduction of guidance for self-management approaches, for example, relaxation and appropriate exercise;

Titration of anti-depressant therapy according to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2010 guidelines for neuropathic pain;

Cessation of outdated practices where no evidence existed for effect;

Introduced new diagnostic tools to improve screening in primary care, for example, STarT Back Screening Tool;

Early assessment of biopsychosocial issues, using valid and reliable tools.

These recommendations and the learners’ end of module evaluations suggest that learners are starting to change practice based on their learning.

Our findings are in keeping with those reported by Sim and Hew,37 which reviewed a range of studies that suggest blogs can help support learning and develop learners thinking and analytical skills, or levels of reflection. Sim and Hew37 report that the majority of learners in the studies reviewed agreed that the blog technology was easy to use and was an exciting experience, and expressed that they would like to see it being used more often as a learning tool. Negative perceptions towards the use of blogs as a learning tool included a dislike for writing, unfamiliarity or confusion with the blog technology and discomfort about providing and receiving peer feedback, issues and concerns surrounding computer availability, difficulty in accessing the blog or making entries, inconvenience of going online and lack of confidence in the reliability of the technology.

Learner evaluation

To ensure that the module is clinically relevant and that it facilitates learners to achieve their learning needs, they are asked to complete an anonymous online survey about module content, delivery, assessment and impact on their clinical practice. Here are some examples of that feedback:

Wider appreciation of biopsychosocial issues and a more holistic assessment of patients.

I have made changes to practice as a reflection of the module.

Changed my approach to reviewing patients with chronic pain – not just concentrating on analgesia but looking at other options and making sure I know what is available in my locality.

I found the module to be a good introduction to the principles of managing chronic pain, and specifically the biopsychosocial approach. Undertaking the module certainly affected my practice; I took on the primary care pain management lead role in my surgery and following on from this, have set up a primary care pain management clinic with our practice psychologist. My increasing involvement in managing pain has further spurred me on to undertake the Postgraduate Certificate in Pain Management.

Conclusion

There is a need for pain education in primary and community care. Delivery of pain education in a 14-week, e-learning module appears to be appropriate for many healthcare professionals and provides an opportunity for interdisciplinary working and learning. The online blog assessment enables students to demonstrate their understanding of the biopsychosocial model and how it applies to aspects of pain and its management. Delivering a master’s level module is facilitating students to develop skills in and evidence of developing evidence-based healthcare, relating to patients in practice. Learner feedback supports that undertaking this module can increase their knowledge and have an impact on patient care. The use of blogs for the assessment was fundamental in enabling learners to demonstrate masters’ level thinking and writing. They also allowed learners to examine more than one specific area of the biopsychosocial factors within pain and its management. This approach to learning and assessment demonstrates that pain education delivered in this way facilitates opportunities for healthcare professionals to change practice.

The future

Based on the success of this module, three other courses have now been validated and set up to meet the learning and clinical needs of healthcare professionals working in Primary and Community Care. They are the postgraduate (PGT) certificate, diploma and MSc in pain management (primary and community care).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The pain management courses and modules are supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Napp Pharmaceuticals Limited.

References

- 1. British Pain Society. Available at: http://www.britishpainsociety.org/media_faq.htm (accessed 20 June 2013).

- 2. Chief Medical Officer. Chief medical officer annual report. Department of Health, UK. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/www.dh.gov.uk/en/publicationsandstatistics/publications/annualreports/dh_096206 (2009, accessed 19 June 2013).

- 3. Royal College of General Practitioners. Care planning: improving the lives of people with long-term conditions. Available at: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/clinical-resources/care-planning.aspx (2011, accessed 18 June 2013).

- 4. Department of Health. Improving the health and well-being of people with long-term conditions. World class services for people with long-term conditions – information tool for commissioners. Available at: http://www.health.org.uk (2010, accessed 18 June 2013).

- 5. Pain Summit. Putting pain on the agenda: the report of the first pain summit. In: Policy Connect, London: Available at: http://www.policyconnect.org.uk/sites/default/files/PuttingPainontheAgenda.pdf (2011, accessed 25 June 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Pain Audit: final report, UK, 2012. Available at: http://www.nationalpainaudit.org/ (2012, accessed 21 August 2013).

- 7. The Health and Social Care Information Centre. Health, social care and lifestyles: summary of key findings. Leeds: The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. The British Pain Society. Pain pathways. Available at: http://www.britishpainsociety.org/members_articles_ppp.htm (2013, accessed 20 June 2013).

- 9. Welsh Assembly Government. Designed to improve health and the management of chronic conditions in Wales: an integrated model and framework. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Department of Health. The mandate: a mandate from the government to the NHS commissioning board: April 2013 to March 2015. London: Williams Lea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomkins S, Collins A. Promoting optimal self care: consultation techniques that improve quality of life for patients and clinicians. Dorset and Somerset: Dorset and Somerset Strategic Health Authority, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Department of Health. Supporting people with long-term conditions to self care: a guide to developing local strategies and good practice. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4130725 (2006, accessed 24 June 2013).

- 13. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006; 10: 287–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Low back pain (CG88): early management of persistent pain. Manchester: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care, May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ellis B, Johnson M, Taylor A. Education as part of wider health policy and improvement strategies. Brit J Pain 2012; 6(2): 54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. UK quality code for higher education – Chapter A1: the national level. Available at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/Publications/InformationAndGuidance/Pages/quality-code-A1.aspx (2011, accessed 18 June 2013).

- 17. Torre DM, Daley BJ, Sebastian JL, et al. Overview of current learning theories for medical educators. Am J Med 2006; 119(10): 903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joint Information Systems Committee. Effective practice with e-learning: a good practice guide in designing for learning. Available at: www.jisc.ac.uk/elp_practice.htm (2004, accessed 18 June 2013).

- 19. Laurillard D. Rethinking university teaching: a conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies, 2nd edn. London: Routledge Falmer, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med 2006; 81: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanuka H. Understanding e-learning technologies-in-practice through philosophies-in-practice. In: Anderson T. (ed.) The theory and practice of online learning, 2nd edn. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Athabasca University Press, 2008, pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education. Defining interprofessional education. Available at: http://www.caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe/ (2002, accessed 23 June 2013).

- 23. Wells G. Dialogic inquiry in education: building on the legacy of Vygotsky. In: Lee CD, Smargorinsky P. (eds) Vygotskian perspectives on literacy research: constructing meaning through collaborative inquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 51–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hrastinski S. A theory of online participation. Comput Educ 2009; 52: 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wheeler S. Open content, open learning 2.0: using wikis and blogs in higher education. In: Ehlers UD, Schneckenberg D. (eds) Changing cultures in higher education. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2010, pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharpe R, Oliver M. Designing courses for e-learning. In: Beetham H, Sharpe R. (eds) Rethinking pedagogy in the digital age. London: Routledge, 2007, pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rosenberg MJ. Beyond e-learning: approaches and technologies to enhance organizational knowledge, learning and performance. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chretien K, Goldman E, Faselis C. The reflective writing class blog: using technology to promote reflection and professional development. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 2066–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Murray M, Kujundzic N. Critical reflection: a textbook for critical thinking. Montreal, QC, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jarvis P. Reflective practice and nursing. Nurse Educ Today 1992; 12(3): 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Conway J. Reflection, the art and science of nursing and the theory practice gap. Br J Nurs 1994; 3(1): 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McConnell D. The experience of collaborative assessment in e-learning. Stud Cont Educ 2002; 24(1): 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parker A. Identifying predictors of academic persistence in distance education. USDLA J 2003; 17(1): 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frankola K. Why online learners drop out. Workforce 2001; 80(10): 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Doherty W. An analysis of multiple factors affecting retention in Web-based community college courses. Internet High Educ 2006; 9(4): 245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bruner JS. The culture of education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sim J, Hew K. The use of weblogs in higher education settings: a review of empirical research. Educ Res Rev 2010; 5(2): 151–163. [Google Scholar]